Abstract

Adolescence is marked by increases in stressful life events. Although research has demonstrated that depressed individuals generate stress, few studies investigate the generation of emotional victimization. The current study examined the effects of rumination and internalizing symptoms on experiences of peer victimization and familial emotional abuse.

Participants were 216 adolescents (M = 14-years-old; 58% female; 47% African-American) who completed two assessments. Results showed that rumination predicted peer victimization and emotional abuse. The effect of rumination on emotional victimization is heightened for those who have higher levels of depression symptoms. That is, individuals who ruminate and who have depression symptoms experience increases in both peer emotional victimization and parental emotional abuse.

This study builds upon prior research and indicates that rumination may be a stronger predictor of emotional victimization than symptoms of depression or anxiety. Identifying underlying mechanisms may yield targets for interventions aimed at addressing the chronic nature of depression.

Keywords: Internalizing symptoms, rumination, emotional abuse, peer victimization

Adolescence is a pivotal developmental period during which events that threaten or damage self-esteem or self-worth, such as emotional victimization by parents or peers, may be particularly detrimental (e.g. Gibb et al., 2004; Hanley & Gibb, 2011). Relational peer victimization, characterized by direct or indirect aggression intended to harm a peer’s relationships or reputation, is a form of emotional maltreatment by peers, that has received considerable attention as a risk factor for depression and anxiety among adolescents (Hamilton et al., 2013; La Greca & Harrison, 2005; Prinstein et al., 2001; Siegel et al., 2009). Familial emotional abuse, defined as verbal assaults on self-worth by a parent or caretaker, also has consistently been found to contribute to psychological maladjustment among youth (Gibb & Abela, 2008; Gibb & Alloy, 2006; Hamilton et al., 2013). Given the debilitating consequences associated with relational peer victimization and familial emotional abuse, identifying factors that contribute to the occurrence of these damaging interpersonal stressors can enhance our understanding of who is at risk for victimization and future maladaptive outcomes. This is the goal of the current study.

Internalizing Symptoms and Experiences of Stress

According to interpersonal theories of depression, internalizing symptoms affect how individuals interact in their interpersonal environments (Blatt & Zuroff, 1992; Coyne, 1976; Hammen, 2005). Specifically, individuals with symptoms of depression, and more recently anxiety, are hypothesized to exhibit maladaptive behavioral tendencies in the interpersonal domain that elicit heightened levels of stress in the social context, including conflict and rejection, which in turn contribute to the development and maintenance of depression and anxiety (for a review, see Liu & Alloy, 2010). Consistent with these theories, numerous studies have found that depression and anxiety contribute to experiences of interpersonal stress among children, adolescents, and adults (Cole et al., 2006; Connolly et al., 2010; Hammen, 1991; Harkness & Stewart, 2009; Rudolph et al., 2000; Uliaszek et al., 2010; 2012; for a review see, Liu & Alloy, 2010).

Rumination and Experiences of Stress

Beyond depressive and anxiety symptoms, other factors may influence the way in which individuals interact with their social environment, such as how individuals respond to their internal state. Rumination, the tendency to repetitively focus attention on the meaning and causes of one’s mood symptoms (Nolen-Hoeksema, 1991), has consistently been found to predict increases in symptoms of depression and anxiety among adolescents (Abela, Brozina, & Haigh, 2002; Hankin, 2008), particularly following stressful events (Abela, Hankin, Sheshko, Fishman, & Stolow, 2012; Cox, Funasaki, Smith, & Mezulis, 2011; Genet & Siemer, 2012). Specifically, during the experience of internalizing symptoms, ruminative thinking becomes activated and interferes with effective coping mechanisms and active problem-solving (Donaldson & Lam, 2004; Jose & Weir, 2012; Lyubomirsky & Nolen-Hoeksema, 1993). Consequently, rumination may not only lead to a more intense and longer period of negative mood (Nolen-Hoeksema, 1991), but may also serve to maintain the stress that initiated the negative mood and even generate new experiences of stress. Indeed, a number of recent studies have found that individuals who ruminate experience higher levels of interpersonal stress (Kercher & Rapee, 2009) and report more interpersonal conflict, even when they are not currently depressed (Nolen-Hoeksema & Davis, 1999). However, no study to date has examined whether rumination interacts with depressive or anxiety symptoms to influence the experience of interpersonal stress. Given that ruminative thinking has been found to increase as internalizing symptoms increase (Gardner & Epkins, 2012; Jose & Weir, 2012; Jose, Wilkins, & Spendelow, 2012; Starr & Davila, 2012), it seems likely that individuals with higher levels of both internalizing symptoms and rumination might be particularly vulnerable to experiences of interpersonal stress. The present study is the first to directly assess the possibility that interpersonal difficulties, within the context of parental and peer emotional victimization, may result from rumination.

Internalizing Symptoms, Rumination, and the Experience of Peer and Familial Emotional Victimization

Although there is mounting evidence that internalizing symptoms and rumination increase the risk of interpersonal stress, fewer studies have examined how these vulnerabilities may contribute to the experience of specific forms of interpersonal stress during adolescence, such as emotional victimization by parents or peers. There are a number of ways in which these factors may increase susceptibility to relational peer victimization and familial emotional abuse. For one, maladaptive interpersonal tendencies found to contribute to interpersonal stress more generally, such as social behaviors (e.g. avoidance of interactions, excessive reassurance-seeking, withdrawal) and personal characteristics (e.g. poor social skills, low self-regard) may also contribute to negative interactions or rejection by peers and family members (Joiner, Alfano, & Metalsky, 1992; Prinstein et al., 2005; Egan & Perry, 1998; Scheeber & Sorensen, 1998). Further, adolescents with these vulnerabilities may have more negative interpersonal expectancies, particularly in relation to parents and peers, and process interactions in these domains more negatively (Rudolph & Clark, 2001; Shirk et al., 1997). Indeed, considerable research has found that adolescents with symptoms of depression and anxiety experience more relational victimization than those without these symptoms (Gibb & Hanley, 2010; Mclaughlin etal., 2009a; Storch et al., 2005; Siegel et al., 2009; Tran et al., 2012). Further, a recent study by McLaughlin and colleagues (2012) found that rumination predicted prospective increases in relational victimization among adolescents. Thus, adolescents with symptoms of depression and anxiety, as well as ruminative tendencies, may be particularly likely to experience relational victimization. However, no study to date has examined how internalizing symptoms or rumination may increase vulnerability to familial emotional abuse. A study by Pearson and colleagues (2010) found that rumination was associated with an underlying concern for being rejected and being interpersonally submissive. Additionally, Sheeber and colleagues (2012) found that dysphoric adolescents displayed more negative behaviors during interactions with their parents. Indeed, adolescents who ruminate or who have depressive symptoms may have an attachment pattern characterized by a fear of rejection and an interpersonal style that may elicit a strained parent-child relationship.

The Present Study

To address gaps in prior research, the goal of the current study was to examine the effects of depressive and anxiety symptoms and rumination on the prospective experiences of relational peer victimization and familial emotional abuse among a community sample of ethnically diverse adolescents. Taken together, because adolescence is a vulnerable period for both the development of depressive and anxiety symptoms as well as increased interpersonal stress, we suggest that internalizing symptoms and ruminative tendencies may heighten the risk of experiencing specific forms of interpersonal stress during adolescence, particularly relational peer victimization and familial emotional abuse. Further, given that rumination is the tendency to focus on internalizing symptoms, the combination of higher levels of internalizing symptoms and rumination in response to these symptoms may be particularly maladaptive during adolescence. Consistent with prior research, we hypothesized that depressive symptoms, anxiety symptoms, and rumination would predict prospective levels of peer victimization and familial emotional abuse. We also hypothesized that internalizing symptoms will moderate the effect of rumination such that adolescents with higher levels of internalizing symptoms would be particularly vulnerable to the effect of rumination on increased experiences of emotional victimization by parents and peers.

Method

Participants

Participants were individuals who, to date, have completed at least two regular prospective assessments of the Adolescent Cognition and Emotion (ACE) Project. Caucasian and African American, male and female adolescents, ages 12 – 13, and their primary female caretakers (92% were the biological mothers; hereafter referred to as “mothers”) were recruited from Philadelphia area public and private middle schools. The current study sample included 216 adolescents (M = 14 years old; SD = 0.87) who completed two regular prospective assessments. Only adolescents with complete data on all study measures were included in the present study; thus, listwise deletion was used for the final sample of 179 (83%). The study sample is 58% female and 47% African American. The families exhibited a wide range of socioeconomic status (SES) levels, with 44% of participants qualifying for free or reduced lunch at school. Adolescents did not differ on age, sex, race, or proportion eligible for free lunch at school from the entire population of students whose mothers initially received recruitment mailings.

Procedures

Adolescents and their mothers made in-person visits at two assessments that were separated by an average of 8.74 months (SD = 4.41 months). Mothers signed a written consent for their own and their child’s participation, and the adolescent signed a written assent. The adolescent completed questionnaires each assessment. The present study only used data from the adolescent. Adolescents completed measures of depressive and anxiety symptoms, rumination, and experiences of emotional victimization from parents and peers at the first assessment (Time 1) and measures of experiences of emotional victimization by parents and peers at the second assessment (Time 2).

Measures

Depression Symptoms

The Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI; Kovacs, 1985) is the most widely used self-report measure of depression symptoms in children and adolescents. The CDI is designed for use with 7 – 17 year olds and consists of 27 items, reflecting affective, behavioral, and cognitive symptoms of depression. Each item is rated on a 0–2 scale. Total scores from all items were used and ranged from 0–54. Higher scores indicate more depression symptoms. The CDI has good reliability and validity in youth (Klein, Dougherty, & Olino, 2005). Internal consistency in this sample was α = .80 at Time 1.

Anxiety Symptoms

The Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children (MASC; March, Parker, Sullivan, Stallings, & Conners, 1997) is a 39-item self-report questionnaire assessing anxiety symptoms in youth at Time 1. It includes the following factors: physical symptoms, social anxiety, harm avoidance, and separation anxiety. Adolescents responded to each item on a 4-point Likert scale with response options of never, rarely, sometimes, or often. A MASC total score was used, with higher scores indicating more anxiety. The MASC has shown excellent test-retest reliability and good convergent and discriminant validity (March et al, 1997; March, Sullivan, & Parker, 1999). Internal consistency in this sample was α = .86 at Time 1.

Rumination

The Children’s Response Styles Questionnaire (CRSQ; Abela, Vanderbilt, & Rochon, 2004) is a 25-item self-report questionnaire that assesses youths’ styles to respond to sad/depressive moods with rumination, distraction, or problem-solving. For each item, adolescents are asked to rate the frequency of their thoughts or feelings when they are sad on 4-point scales from never, sometimes, often, or almost always. Higher scores indicate a greater tendency for youths to engage in rumination, distraction, or active problem-solving as a response tendency when feeling sad or depressed. The current study only used the rumination subscale of this measure. Sample items include, “When I am sad, I think about how alone I feel” and “When I am sad I think about all my failures, faults, and mistakes.” Past research with the CRSQ indicated good validity and moderate internal consistency (Abela et al., 2004). Internal consistency of the rumination subscale for this sample was α = .89 at Time 1.

Emotional Abuse

A modified version of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire – Emotional Maltreatment subscale (CTQ-EM; Bernstein et al., 1994) was used to assess adolescents’ levels of familial emotional abuse. The CTQ-EM is a self-report scale that assesses emotional abuse (5 items) with each item rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from never true to very true. Higher scores indicate higher levels of emotional abuse. This measure was given at Time 1 and Time 2 with adolescents reporting on experiences since the last assessment. Previous studies support the reliability and validity of the CTQ-EM in both clinical and community samples (Bernstein et al., 1997; Bernstein et al., 2003; Scher et al., 2001) as well as predictive validity for depression symptoms (Gibb et al., 2006). Internal consistencies in this sample were α = .73 at Time 1 and α = .76 at Time 2.

Peer Relational Victimization

A modified version of the Children’s Social Experiences Questionnaire (SEQ; Crick & Grotpeter, 1996) was used to assess peer victimization. The original SEQ consisted of the subscales of relational victimization, overt victimization, and prosocial behavior. The current study consisted of a 6-item scale assessing youths’ report of relational victimization by peers that assessed whether they experienced attempts to harm their peer relations. At Time 1 and Time 2, adolescents reported on the types of behaviors they experienced from their peers since the last assessment using a true or false scale; items were summed to yield a composite score. The SEQ has demonstrated adequate reliability and validity (Crick & Bigbee, 1998; Crick & Grotpeter, 1996; Storch, Crisp, Roberti, Bagner, & Masia-Warner, 2005). The internal consistencies in the current sample were α = .69 at Time 1 and α = .72 at Time 2.

Results

Table 1 presents the bivariate correlations between all variables used in the present analyses. As expected, depression and anxiety symptoms were positively correlated with all study variables. In addition, familial emotional abuse and peer victimization were positively correlated. Finally, rumination was positively correlated with symptoms and levels of familial emotional abuse and peer victimization. Preliminary analyses were then conducted to determine whether any of the dependent variables were significantly related to adolescents’ demographic characteristics (age, sex, race, and SES). The adolescents’ age, racial, and income characteristics did not significantly predict differences in familial emotional abuse or peer victimization at follow-up.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations between main study variables

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Depressive Symptoms Time 1 | - | .34*** | .49*** | .64*** | .39*** | .49*** | .36*** |

| 2 Anxiety Symptoms Time 1 | - | .32*** | .24*** | .24*** | .26*** | .17* | |

| 3 Rumination Time 1 | - | .38*** | .44*** | .21** | .39*** | ||

| 4 Emotional Abuse Time 1 | - | .56*** | .41*** | .33*** | |||

| 5 Emotional Abuse Time 2 | - | .16* | .31*** | ||||

| 6 Peer Victimization Time 1 | - | .44*** | |||||

| 7 Peer Victimization Time 2 | - | ||||||

| Mean | 5.53 | 36.80 | 23.31 | 7.65 | 7.48 | 2.24 | 1.67 |

| SD | 5.64 | 13.89 | 7.45 | 3.36 | 2.93 | 3.53 | 3.02 |

Note:

p < .001,

p < .01,

p < .05

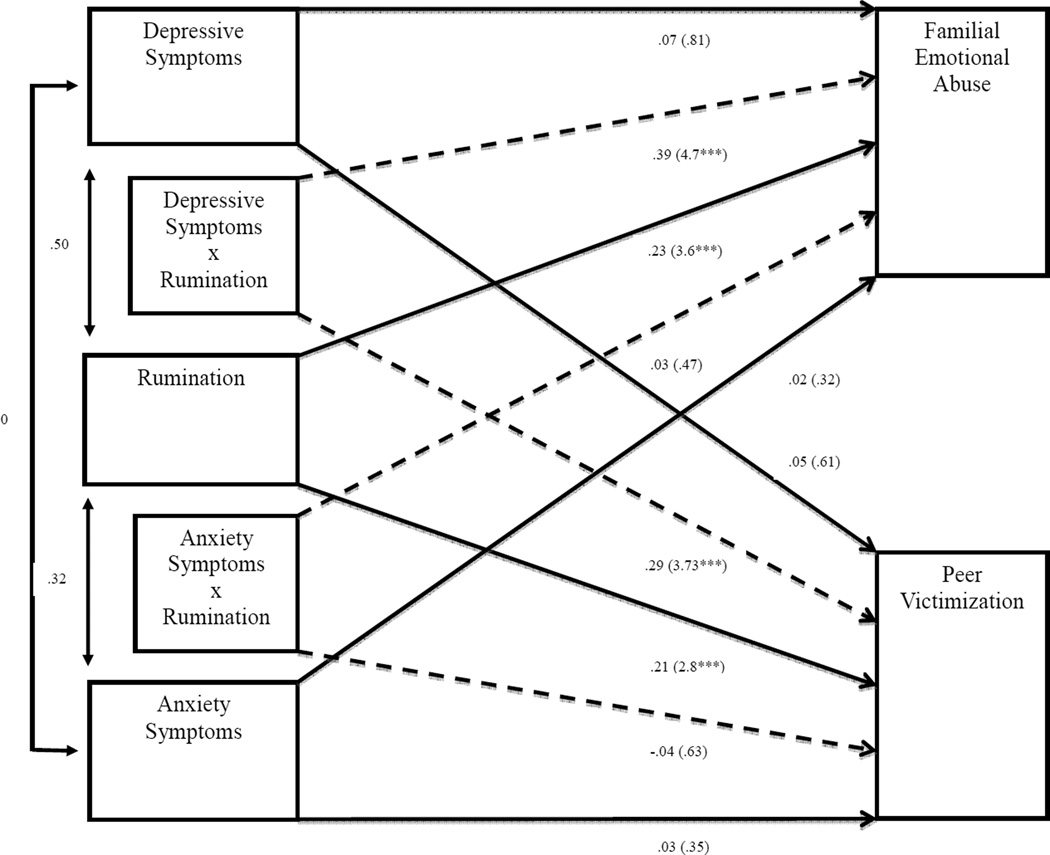

Using the Mplus structural equation modeling (SEM) software (Muthen & Muthen, 2010), we examined whether depression symptoms, anxiety symptoms, or rumination predicted prospective levels of familial emotional abuse or peer victimization (Figure 1). The use of this method allows for the simultaneous examination of variables in a single model, allowing one to account for the covariance of variables in the model (Hoyle & Smith, 1994). In this model, we examined the paths between Time 1 depression symptoms, anxiety symptoms, and rumination and Time 2 stressors (familial emotional abuse and peer victimization), while controlling for initial (Time 1) levels of familial emotional abuse and peer victimization to account for prior levels of each outcome. We also included sex and the number of days elapsed between assessments as covariates. This model had a good fit (χ2 = .78, p = .78; comparative fit index (CFI) = 1.00; root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) < .001; standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) <.01; Hu & Bentler, 1999).

Figure 1.

Relationship among depression, anxiety, and rumination on emotional victimization.

Note: Two SEM models were tested. Model 1 included only the main effects of Depressive Symptoms, Rumination and Anxiety Symptoms on Familial Emotional Abuse (R2 = .48) and Peer Victimization (R2 = .25). Model 2 included the interactive effects on Familial Emotional Abuse (R2 = .63) and Peer Victimization (R2 = .29). Model 1 is indicated with solid lines and Model 2 is indicated with dashed lines. Standardized coefficients, t statistics, and significance values are presented (*** p <.001).

As shown in the first columns of Table 2, rumination at Time 1 predicted prospective levels of peer victimization (t = 4.75, p < .001) and familial emotional abuse (t = 5.91, p < .001), such that greater levels of rumination predicted higher prospective levels at Time 2 controlling for initial levels of the dependent variables as well as depression and anxiety symptoms. In the model, neither depression symptoms nor anxiety symptoms predicted prospective levels of familial emotional abuse or peer victimization.1

Table 2.

Time 1 predictors of familial emotional abuse and peer victimization

| Emotional Abuse at Time 2 | Peer Victimization at Time 2 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictors | β | t | β | t | β | t | β | t |

| Depressive Symptoms Time 1 | 0.07 | 0.81 | −0.01 | 0.11 | 0.05 | 0.61 | −0.11 | 1.23 |

| Anxiety Symptoms Time 1 | 0.02 | 0.32 | 0.04 | 0.69 | 0.03 | 0.35 | 0.10 | 1.47 |

| Rumination Time 1 | 0.23 | 3.57*** | 0.18 | 3.12** | 0.21 | 2.77** | 0.19 | 2.44* |

| Emotional Abuse Time 1 | 0.48 | 6.73*** | 0.40 | 5.91*** | - | - | - | - |

| Peer Victimization Time 1 | - | - | - | - | 0.33 | 4.75*** | 0.30 | 4.35*** |

| Sex | 0.07 | 1.15 | 0.06 | 1.26 | −0.03 | 0.47 | −0.04 | 0.56 |

| Time to Follow Up | −0.01 | 0.13 | 0.01 | 0.17 | −0.18 | 2.72** | −0.16 | 2.61** |

| Depressive Symptoms x Rumination | - | - | 0.39 | 4.71*** | - | - | 0.29 | 3.73*** |

| Anxiety Symtpoms x Rumination | - | - | 0.03 | 0.47 | - | - | −0.04 | 0.63 |

| R2 | 0.48 | 0.64 | 0.25 | 0.29 | ||||

Note:

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001;

The first two columns for each dependent variable indicates the main effects of each predictor while the second two columns include the interaction terms. R2 for the interaction term is presented for the depression x rumination interaction only.

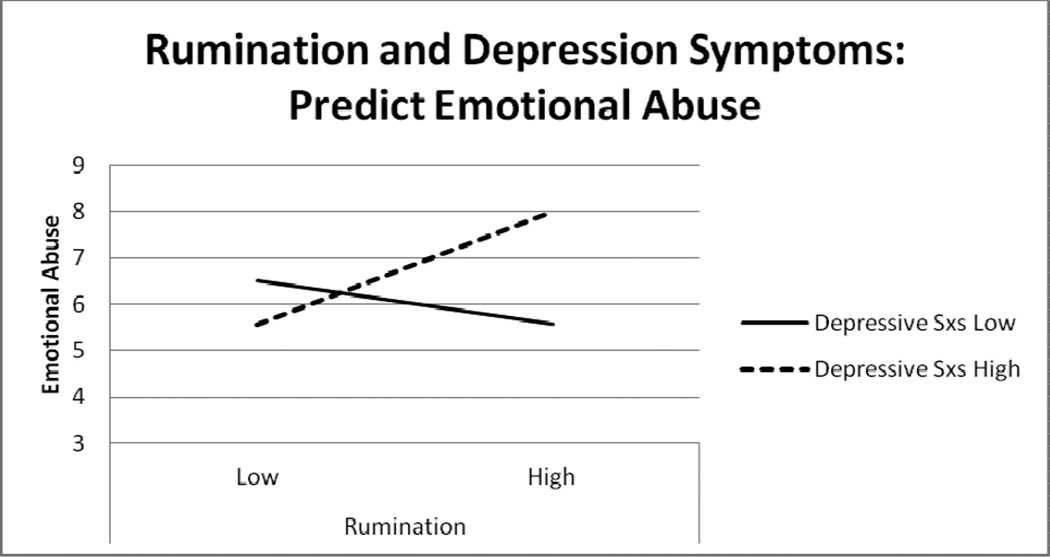

A SEM framework was also used to investigate whether rumination interacted with depression or anxiety symptoms to predict increases in either familial emotional abuse or peer victimization (Table 2). We conducted our analyses following the procedure outlined by Aiken and West (1991) and mean centered depression symptoms, anxiety symptoms, and rumination. The same control variables were used as in the prior analysis. The data provided an excellent fit to the model (χ2 = .75, p = .69, CFI = 1.00; RMSEA < .001; SRMSR < .01). The second step in Table 2 shows the interaction between rumination and depressive symptoms as well as between rumination and anxiety symptoms predicting either familial emotional abuse or peer victimization at Time 2. As seen in the models, the interaction between depression symptoms and rumination was significant for both familial emotional abuse and peer victimization at Time 2. Consistent with the approach described by Aiken and West (1991), we tested the simple slopes of the effect of rumination at high or low levels of depressive symptoms. For adolescents with initially high levels of depression symptoms, rumination was positively associated with familial emotional abuse (β = .41, p < .001) and peer victimization (β = .35 p < .001), whereas among those with low initial levels of depression symptoms, no association was observed between rumination and familial emotional abuse (β = .02, p = ns) and peer victimization (β = .06, p = ns). To illustrate, as seen in Figure 2, individuals with higher levels of rumination and high levels of depression symptoms had more experiences of familial emotional abuse at follow-up, whereas individuals with lower levels of depression symptoms and higher levels of rumination had less experiences of familial emotional abuse. After testing the simple slopes, the effect of high rumination increased only when depression symptoms were also high to significantly predict higher levels of peer victimization and familial emotional abuse. Anxiety symptoms did not moderate the effect of rumination predicting to either familial emotional abuse or peer victimization.

Figure 2.

Interaction between rumination and depression symptoms predicts prospective emotional abuse.

Note: Low and High refer to one standard deviation above and below the mean of each independent variable. This is the same direction of effect for Peer Victimization.

Discussion

The current study provided the first examination of the effects of depression and anxiety symptoms and rumination on prospective experiences of both peer and familial emotional victimization during adolescence. This study builds upon prior research highlighting the importance of how one responds to their emotions and its effects on the interpersonal context. Specifically, our findings indicate that rumination is a stronger predictor of emotional victimization by both family and peers than symptoms of depression or anxiety. Taken further, results from the current study suggest that the effect of rumination on experiences of emotional victimization is heightened for those who have higher levels of depression symptoms. That is, individuals who tend to ruminate about their internal feelings and who have depression symptoms experience increases in both peer emotional victimization and parental emotional abuse.

Although prior research suggests that heightened levels of rumination predict higher levels of interpersonal stress among adolescents (Kercher & Rapee, 2009), this is the first study to find that adolescents with a tendency to ruminate experience increases in both peer emotional victimization and familial emotional abuse. Although levels of rumination may not directly contribute to the occurrence of these stressors, research suggests that individuals who ruminate tend to be more sensitive to interpersonal rejection (Pearson et al., 2010), which may lead to the perception of greater future rejection. To speculate, if an individual is hyper-focused on their internal feelings, they may be more sensitive to experiences of rejection in the peer domain, as well as more susceptible to interpreting parental feedback as negative. Additionally, the tendency to ruminate and repetitively focus attention on the meaning and causes of one’s mood may preclude effective interpersonal problem solving and interfere in positive social interaction. Thus, individuals who ruminate may not only be more sensitive to the occurrence of these stressors, but they may also engage in certain maladaptive behaviors that elicit more negative interactions with peers or family members.

When examined individually, both depressive symptoms and rumination individually increase the likelihood of experiencing interpersonal stress, and combined may contribute to maladaptive interpersonal tendencies that heighten risk further. Indeed, in the absence of depressive symptoms, the effects of rumination on experiences of emotional victimization may not be elicited. In addition, when symptoms were entered in the model with rumination, the main effect of depressive symptoms was no longer significant compared to when depressive symptoms were entered individually. This suggests that rumination may be driving the process of experiences of emotional victimization. In recent years, the response style theory has been reexamined and subtypes of rumination have been suggested (Treynor, Gonzalez, & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2003; Whitmer & Gotlib, 2011). Namely, brooding, defined as focusing attention on negative, self-blaming, and gloomy thoughts, is predictive of depressive symptoms whereas reflection, defined as focusing attention non-judgmentally upon neutral or positive cntent, has shown inconsistent associations with depressive symptoms (Cox et al., 2011; Verstraeten et al., 2010). Although the current study methods precluded a more fine-grained approach to rumination, further research may benefit from this distinction as the relationship between brooding and emotional victimization may be particularly important.

Even though depressive symptoms no longer predicted peer victimization when levels of rumination were accounted for, consistent with prior research (Gibb & Hanley, 2010), depression symptoms, but not anxiety, when entered individually prospectively predicted greater levels of peer victimization. Although both parent and peer relationships are important, the peer domain increases in importance and focus during adolescence making experiences of victimization potentially more salient. Indeed, adolescents with higher levels of depressive symptoms may be more sensitive to experiences of rejection in the peer domain (McCarty et al., 2007). Whereas research suggests that anxiety is also a vulnerability factor for experiences of emotional victimization (e.g., Crawford & Manassis, 2011), results from the current study show that anxiety symptoms did not predict increases in either type of emotional victimization experiences nor did anxiety symptoms heighten the effects of rumination. This suggests that depressive symptoms might be a more specific vulnerability factor for being the target of peer victimization compared to anxious symptoms. Research consistently suggests that adolescents who experience peer victimization are at risk for developing increased depressive symptoms (e.g., McLaughlin et al., 2009b). Although not directly examined in the current study, these findings highlight the implication of a bidirectional relationship between emotional victimization and depression during adolescence (Sweeting et al., 2006; Tran et al., 2012). The relationship between depressive symptoms and subsequent experiences of emotional peer victimization may help explain how depression is often a chronic and recurring disorder highlighting the importance of targeted intervention that may counteract this downward cycle.

Although past research has demonstrated that early abuse experiences and peer victimization are risk factors for depression and lead to the development of rumination, the current study assesses the relationship in the reverse direction. Given the debilitating consequences associated with both relational peer victimization and familial emotional abuse, identifying factors that differentially contribute to these occurrences is important. Although the current examination relied upon self-report severity measures of peer and parental emotional victimization, these results suggest a connection with the stress generation literature. Interpersonal stressors have emerged in past studies as being of particular relevance to stress generation (Hammen, 2006). Adding to this trend, our findings are consistent with the possibility of a stress generation effect of depression symptoms and rumination on specific types of interpersonal experiences of particular relevance to early adolescence. These findings should not be taken to suggest that anxiety symptoms are irrelevant to stress generation, especially given the increasing evidence indicating otherwise (e.g., Connolly et al., 2010; Uliaszek et al., 2012). Rather, they are consistent with the view that depression may differ from other forms of psychopathology in its associated stressors (Hammen, 2006).

This study is notable for its large and ethnically diverse sample. Another strength is its prospective assessment of emotional victimization, in contrast to much prior research utilizing retrospective reports of childhood maltreatment experiences. Despite these strengths, several limitations should also be mentioned. First, the measures of emotional victimization were self-report questionnaires, which may be susceptible to subjective interpretive biases. Additionally, individuals with depressive or anxiety symptoms may interpret ambiguous interpersonal cues as negative, thereby leading to the perception of greater negative interpersonal stress and rejection (De los Reyes et al., 2004; Downey & Feldman, 1996; Rudolph et al., 1994). Consequently, adolescents with depressive and anxiety symptoms may not only experience higher levels of interpersonal stress, but may also have biased social-information processes that lead to the perception of and greater sensitivity to more interpersonal stress (e.g., McCarty et al., 2007). Future studies should include other measures of these constructs (e.g., parent and teacher reports of victimization experiences at school) that may be more objective indicators of emotional victimization. Controlling for levels of anxiety and depression at measurement could also help to allay concerns about reporter bias when ascertaining information on victimization.

In addition, as this study did not directly examine the stress generation hypothesis in predicting to specific types of interpersonal stress, future research could employ a more rigorous stress interview to obtain more objective measures of familial emotional abuse or peer victimization, thus teasing apart an individual’s interpretation from the experiences reported. It is important to note the directionality of this study. The current findings suggest that initial levels of depression and rumination lead to increased emotional victimization controlling for initial levels of emotional victimization. Based on prior research, it is plausible that emotional victimization led to increases in depression and rumination in the first place (e.g., Barchia & Bussey, 2010; Rudolph, Troop-Gordon, & Granger, 2011). Thus, examining a bi-directional relationship between depression and emotional victimization may be advantageous for future research. Additionally, the current study did not examine a mediational pathway of internalizing symptoms influencing emotional victimization through rumination and, thus, we did not rule out an alternative possibility of mediation, which may be an in important area of further inquiry. Finally, the assessment of depression and anxiety symptoms in a non-clinical sample of adolescents restricts the generalization of the present findings to clinical depression and anxiety. Thus, to strengthen the clinical relevance of the present findings, future research should replicate them in clinical samples.

When considered together with previous studies, the current findings highlight the importance of rumination and its effects on experiences in the interpersonal domain. They suggest the existence of a possible reciprocal relation between rumination and emotional victimization; not only does emotional victimization increase the possibility of ruminating about one’s depressive responses, but the presence of rumination, in turn, places the individual at risk for future maltreatment experiences. This effect is strengthened for those who experience depressive symptoms. Although this study did not allow for an assessment of potential mechanisms accounting for how rumination may confer risk for verbal forms of victimization, several possibilities may be explored in future research, and have potential importance for informing clinical intervention strategies. Identifying the mechanisms underlying this relation may yield promising targets for interventions aimed at addressing the often chronic nature of depression. One potential mediator of this relation is excessive reassurance-seeking, a pattern of behavior involving repeatedly appealing to others for assurance of one’s self-worth to the eventual point of annoyance and rejection (Coyne, 1976). This behavioral pattern has been associated with depression (Starr & Davila, 2008) and implicated in stress generation (see Liu & Alloy, 2010 for a review). To the extent that frustration with this behavior is found to result in verbal abuse from parents and victimization from peers, teaching children with this behavioral tendency to adopt a more adaptive alternative may prove fruitful in clinical intervention. Additionally, insofar as certain emotional victimization experiences stem from frustration in not understanding a child’s depression presentation and how best to respond to it, the present findings underscore the importance of parental psychoeducation regarding the nature of depression and rumination and teaching parents skills to effectively manage their child’s behavioral tendencies.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIMH grants MH79369 to Lauren B. Alloy and MH099764-01 to Benjamin G. Shapero.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Of note, to explore these relationships further, when entered individually using linear regression, and thus not controlling for the covariance between the levels of the other predictors, depression symptoms at Time 1 predicted prospective levels of peer victimization (² = 13, t = 1.99, p < .05), but not familial emotional abuse (β = .10, t = 1.44, ns), such that greater depression symptoms predicted higher levels of peer victimization only, whereas, anxiety symptoms did not predict prospective levels of familial emotional abuse (β = .07, t = 1.22, p = ns) or peer victimization (β = .10, t = 1.63, p = ns). Although this suggests that rumination is a stronger predictor of experiences of emotional victimization during adolescence, it appears that, consistent with prior research, depression is a significant predictor of relational peer victimization only.

References

- Abela JRZ, Brozina K, Haigh EP. An examination of the response styles theory of depression in third- and seventh-grade children: A short-term longitudinal study. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2002;30:515–527. doi: 10.1023/a:1019873015594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abela JRZ, Hankin BL, Sheshko DM, Fishman MB, Stolow D. Multi-wave prospective examination of the stress-reactivity extension of response styles theory of depression in high-risk children and early adolescents. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2012;40:277–287. doi: 10.1007/s10802-011-9563-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abela JRZ, Vanderbilt E, Rochon A. A test of the integration of the response styles and social support theories of depression in third and seventh grade children. Journal of Social & Clinical Psychology. 2004;23:653–674. [Google Scholar]

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Barchia K, Bussey K. The psychological impact of peer victimization: Exploring social-cognitive mediators of depression. Journal of Adolescence. 2010;33:615–623. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2009.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein DP, Ahluvalia T, Pgge D, Handelsman L. Validity of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire in an adolescent psychiatric population. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1997;36:340–348. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199703000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein DP, Fink L, Handelsman L, Foote J, Lovejoy M, Wenzel K, Sapareto E, Ruggiero J. Initial reliability and validity of a new retrospective measure of child abuse and neglect. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1994;151:1132–1136. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.8.1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein DP, Stein JA, Newcomb MD, Walker E, Pogge D, Ahluvalia T, Stokes J, Handelsman L, Medrano M, Desmond D, Zule W. Development and validation of a brief screening version of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire. Child Abuse and Neglect. 2003;27:169–190. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(02)00541-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blatt SJ, Zuroff DC. Interpersonal relatedness and self-definition: Two prototypes for depression. Clinical Psychology Review. 1992;12(5):527–562. [Google Scholar]

- Cole DA, Nolen-Hoeksema S, Girgus J, Gilda P. Stress exposure and stress generation in child and adolescent depression: A latent trait-state-error approach to longitudinal analysis. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2006;115:40–51. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.115.1.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connolly NP, Eberhart NK, Hammen CL, Brennan PA. Specificity of stress generation: A comparison of adolescents with depressive, anxiety, and comorbid diagnoses. International Journal of Cognitive Therapy. 2010;3:368–379. doi: 10.1521/ijct.2010.3.4.368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox S, Funasaki K, Smith L, Mezulis AH. A prospective study of brooding and reflection as moderators of the relationship between stress and depressive symptoms in adolescence. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2012;36:290–299. [Google Scholar]

- Coyne JC. Depression and the response of others. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1976;85:186–193. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.85.2.186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coyne JC. Toward an interactional description of depression. Psychiatry. 1976;39:28–40. doi: 10.1080/00332747.1976.11023874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford AM, Manassis K. Anxiety, social skills, friendship quality, and peer victimization: An integrated model. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2011;25:924–931. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2011.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crick NR, Bigbee MA. Relational and overt forms of peer victimization: A multi-informant approach. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1998;66:313–322. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.2.337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crick NR, Grotpeter JK. Children’s treatment by peers: Victims of relational and overt aggression. Development and Psychopathology. 1996;8:367–380. [Google Scholar]

- De los Reyes A, Prinstein MJ. Applying depression-distortion hypotheses to the assessment of peer victimization in adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2004;33:325–335. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3302_14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donaldson C, Lam D. Rumination, mood and social problem-solving in major depression. Psychological Medicine. 2004;34(7):1309–1318. doi: 10.1017/s0033291704001904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downey G, Feldman SI. Implications of rejection sensitivity for intimate relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1996;70:1327–1343. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.70.6.1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egan SK, Perry DG. Does low self-regard invite victimization? Developmental Psychology. 1998;34:299–309. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.34.2.299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner C, Epkins CC. Girls’ rumination and anxiety sensitivity: Are they related after controlling for girl, maternal, and parenting factors? Child & Youth Care Forum. 2012;41:561–578. [Google Scholar]

- Genet JJ, Siemer M. Rumination moderates the effects of daily events on negative mood: Results from a diary study. Emotion. 2012;12:1329–1339. doi: 10.1037/a0028070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibb BE, Abela JRZ. Emotional abuse, verbal victimization, and the development of children’s negative inferential styles and depressive symptoms. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2008;32:161–176. [Google Scholar]

- Gibb BE, Abramson LY, Alloy LB. Emotional maltreatment from parents, verbal peer victimization, and cognitive vulnerability to depression. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2004;28:1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Gibb BE, Alloy LB. A prospective test of the Hopelessness Theory of depression in children. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2006;35:164–174. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3502_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibb BE, Alloy LB, Walshaw PD, Comer JS, Shen GHC, Villari AG. Predictors of attributional style change in children. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2006;34:425–439. doi: 10.1007/s10802-006-9022-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibb BE, Hanley AJ. Depression and interpersonal stress generation in children: Prospective impact on relational versus overt victimization. International Journal of Cognitive Therapy. 2010;3:358–367. doi: 10.1521/ijct.2010.3.4.358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton JL, Shapero BG, Stange JP, Hamlat EJ, Abramson LY, Alloy LB. Emotional maltreatment, peer victimization, and depressive versus anxiety symptoms during adolescence: Hopelessness as a mediator. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2013 doi: 10.1080/15374416.2013.777916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammen C. Generation of stress in the course of unipolar depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1991;100:555–561. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.100.4.555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammen C. Stress and depression. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2005;1:293–319. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.143938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammen C. Stress generation in depression: Reflections on origins, research, and future directions. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2006;62:1065–1082. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hankin BL. Rumination and depression in adolescence: Investigating symptom specificity in a multi-wave prospective study. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2008;37(4):701–713. doi: 10.1080/15374410802359627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanley AJ, Gibb BE. Verbal victimization and changes in hopelessness among elementary school children. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2011;40:772–776. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2011.597086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harkness KL, Stewart JG. Symptom specificity and the prospective generation of life events in adolescence. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2009;118(2):278–287. doi: 10.1037/a0015749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoyle RH, Smith GT. Formulating clinical research hypotheses as structural equation models: A conceptual overview. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1994;62:429–440. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.62.3.429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu LT, Bentler PM. Cutoff Criteria for Fit Indexes in Covariance Structure Analysis: Conventional Criteria Versus New Alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling. 1999;6:1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Joiner TE, Alfano MS, Metalsky GI. When depression breeds contempt: Reassurance seeking, self-esteem, and rejection of depressed college students by their roommates. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1992;101:165–173. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.101.1.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jose PE, Weir KF. How is anxiety involved in the longitudinal relationship between brooding rumination and depressive symptoms in adolescents? Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2012 doi: 10.1007/s10964-012-9891-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jose PE, Wilkins H, Spendelow JS. Does social anxiety predict rumination and co-rumination among adolescents? Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2012;41:86–91. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2012.632346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kercher A, Rapee RM. A test of a cognitive diathesis-stress generation pathway in early adolescent depression. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2009;37:845–855. doi: 10.1007/s10802-009-9315-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein DN, Dougherty LR, Olino TM. Toward guidelines for evidence-based assessment of depression in children and adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2005;34:412–432. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3403_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs M. The Children's Depression Inventory (CDI) Psychopharmacology Bulletin. 1985;21:995–998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La Greca AM, Harrison HM. Adolescent peer relations, friendships, and romantic relationships: do they predict social anxiety and depression? Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2005;34:49–61. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3401_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu RT, Alloy LB. Stress generation in depression: A systematic review of the empirical literature and recommendations for future study. Clinical Psychology Review. 2010;30:582–593. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyubomirsky S, Nolen-Hoeksema S. Self-perpetuating properties of dysphoric rumination. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1993;65:339–339. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.65.2.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- March JS, Parker JD, Sullivan K, Stallings P, Conners CK. The multidimentional anxiety scale for children (MASC): factor structure, reliability, and validity. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1997;26:554–565. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199704000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- March JS, Sullivan K, Parker J. Test-retest reliability of the multidimentional anxiety scale for children. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 1999;13:349–358. doi: 10.1016/s0887-6185(99)00009-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarty CA, Stoep AV, McCauley E. Cognitive features associated with depressive symptoms in adolescence: Directionality and specificity. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2007;36:147–158. doi: 10.1080/15374410701274926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin KA, Hatzenbuehler ML. Stressful life events, anxiety sensitivity, and internalizing symptoms in adolescents. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2009a;118:659–669. doi: 10.1037/a0016499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin KA, Hatzenbuehler ML. Mechanisms linking stressful life events and mental health problems in a prospective, community-based sample of adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2009b;44:153–160. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.06.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin KA, Green JG, Gruber M, Sampson NA, Zaslavsky AM, Kessler RC. Childhood adversities and first onset of psychiatric disorders in a national sample of US adolescents. JAMA Psychiatry. 2012;69:1151–1160. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.2277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthen LK, Muthen BO. Mplus User’s Guide. Sixth Edition. Los Angeles, CA: Muthen & Muthen; 1998–2010. [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S. Responses to depression and their effects on the duration of depressive episodes. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1991;100:569–582. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.100.4.569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson KA, Watkins ER, Mullan EG, Moberly NJ. Psychosocial correlates of depressive rumination. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2010;48:784–791. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2010.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prinstein MJ, Boergers J, Vernberg EM. Overt and relational aggression in adolescents: Social-psychological adjustment of aggressors and victims. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2001;30:479–491. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3004_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prinstein MJ, Borelli JL, Cheah CSL, Simon VA, Aikins JW. Adolescent girls’ interpersonal vulnerability to depressive symptoms: A longitudinal examination of reassurance-seeking and peer relationships. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2005;114:676–688. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.114.4.676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph KD, Hammen C, Burge D. Interpersonal functioning and depressive symptoms in childhood: Addressing the issues of specificity and comorbidity. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1994;22:355–371. doi: 10.1007/BF02168079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph KD, Hammen C, Burge D, Lindberg N, Herzberg D, Daley SE. Toward an interpersonal life-stress model of depression: The developmental context of stress generation. Development and Psychopathology. 2000;12:215–234. doi: 10.1017/s0954579400002066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph KD, Troop-Gordon W, Granger DA. Individual differences in biological stress responses moderate the contribution of early peer victimization to subsequent depressive symptoms. Psychopharmacology. 2011;214:209–219. doi: 10.1007/s00213-010-1879-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scher CD, Stein MB, Asmundson GJG, McCreary DR, Forde DR. The Childhood Trauma Questionnaire in a community sample: Psychometric properties and normative data. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2001;14:843–857. doi: 10.1023/A:1013058625719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheeber LB, Kuppens P, Wu Shorn J, Fainsilber Katz L, Davis B, Allen NB. Depression is associated with the escalation of adolescents' dysphoric behavior during interactions with parents. Emotion. 2012;12:913–918. doi: 10.1037/a0025784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel RS, La Greca AM, Harrison HM. Peer victimization and social anxiety in adolescents: Prospective and reciprocal relationships. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2009;38:1096–1109. doi: 10.1007/s10964-009-9392-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starr LR, Davila J. Excessive reassurance seeking, depression, and interpersonal rejection: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2008;117:762–775. doi: 10.1037/a0013866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starr LR, Davila J. Responding to anxiety with rumination and hopelessness: Mechanism of anxiety-depression symptom co-occurrence? Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2012;36:321–337. doi: 10.1007/s10608-011-9363-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storch EA, Masia-Warner C, Crisp H, Klein RG. Peer victimization and social anxiety in adolescence: A prospective study. Aggressive Behavior. 2005;31:437–452. [Google Scholar]

- Sweeting H, Young R, West P, Der G. Peer victimization and depression in early-mid adolescence: A longitudinal study. British Journal of Educational Psychology. 2006;76:577–594. doi: 10.1348/000709905X49890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran CV, Cole DA, Weiss B. Testing reciprocal longitudinal relations between peer victimization and depressive symptoms in adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2012;41:353–360. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2012.662674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treynor W, Gonzalez R, Nolen-Hoeksema S. Rumination reconsidered: A psychometric analysis. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2003;27:247–259. [Google Scholar]

- Uliaszek AA, Zinbarg RE, Mineka S, Craske MG, Griffith JW, Sutton JM, Epstein A, Hammen C. A longitudinal examination of stress generation in depressive and anxiety disorders. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2012;121:4–15. doi: 10.1037/a0025835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uliaszek AA, Zinbarg RE, Mineka S, Craske MG, Sutton JM, Griffith JW, Hammen C. The role of neuroticism and extraversion in the stress–anxiety and stress–depression relationships. Anxiety, Stress, & Coping. 2010;23(4):363–381. doi: 10.1080/10615800903377264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verstraeten K, Vasey MW, Raes F, Bijttebier P. Brooding and reflection as components of rumination in late childhood. Personality and Individual Differences. 2010;48:367–372. [Google Scholar]

- Whitmer A, Gotlib IH. Brooding and reflection reconsidered: A factor analytic examination of rumination in currently depressed, formerly depressed, and never depressed individuals. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2011;35:99–107. [Google Scholar]