Abstract

While the onset of mechanical hyperalgesia induced by endothelin-1 was delayed in female rats, compared to males, the duration was much longer. Given that the repeated test stimulus used to assess nociceptive threshold enhances hyperalgesia, a phenomenon we have referred to as stimulus induced enhancement of hyperalgesia, we also evaluated for sexual dimorphism in the impact of repeated application of the mechanical test stimulus on endothelin-1 hyperalgesia. In male and female rats, endothelin-1 induced hyperalgesia is already maximal at 30 min. At this time stimulus-induced enhancement of hyperalgesia, which is observed only in male rats, persisted for 3–4 hours. In contrast, in females, it develops only after a very long (15 day) delay, and is still present, without attenuation, at 45 days. Ovariectomy eliminated these differences between male and female rats. These findings suggest marked, ovarian-dependent sexual dimorphism in endothelin-1induced mechanical hyperalgesia and its enhancement by repeated mechanical stimulation.

Keywords: Endothelin, Gender, Hyperalgesia, Rat, Sexual dimorphism, Stimulus, Enhancement

Introduction

Endothelins signal through two G-protein coupled receptors (Rubanyi and Polokoff, 1994) ETA (Arai, et al., 1990) and ETB (Sakurai, et al., 1990), both of which are thought to be present on sensory neurons (Laziz, et al., 2010, Werner, et al., 2010) as well as on the endothelial cells lining blood vessels (Sanchez, et al., 2010). Endothelin-1 (ET-1) is the most abundant and widely expressed (Inoue, et al., 1989, Yanagisawa and Masaki, 1989) member of the endothelin family (i.e., ET-1, ET-2, and ET-3) of potent vasoconstrictor peptides (Yanagisawa et al., 1988). ET-1, which sensitizes nociceptors at low concentrations and activates them at high concentrations (Khodorova, et al., 2009), has been implicated in vascular (Kaski and Perez Fernandez, 2002, Noori and Kabbani, 2003) and cancer (Quang and Schmidt, 2010, Werner, et al., 2010) pain syndromes. An important source of endothelin and location for its receptors is the vascular endothelial cell (Enseleit, et al., 2001, Kallakuri, et al., 2010, Loesch, 2005), and vasculature is densely innervated by unmyelinated sensory neurons (Lauria, et al., 2009, Risling, et al., 1994). Importantly, vascular function is highly sexually dimorphic (LaPrairie and Murphy, 2010, McKelvy, et al., 2007), as are some vascular pain syndromes (Chichorro, et al., 2010, Millecamps, et al., 2010), effects that are dependent on ovarian hormones (Flinsenberg, et al., 2010, Taube and Schirner, 1992). And recent studies have demonstrated sexual dimorphism in second-messenger signaling for primary afferent nociceptor sensitization (Berkley, et al., 2007, Fan, et al., 2009, Joseph and Levine, 2003, Khasar, et al., 2005, Lu, et al., 2009). While endothelin-induced pain has been shown to be sexually dimorphic in neonates (McKelvy, et al., 2007, McKelvy and Sweitzer, 2009), this has not been evaluated for in the adult animal, nor has gonad dependence been studied. Therefore, in the present experiments, we examined for sexual dimorphism in endothelin hyperalgesia and its gonad dependence, in the adult rat.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

Experiments were performed on adult male and female Sprague–Dawley rats (200–250 g; Charles River, Hollister, CA). Animals were housed three per cage, under a 12-h light/dark cycle, in a temperature and humidity controlled environment. Food and water were available ad libitum. All nociceptive testing was done between 10:00 am and 4:00 pm. All experimental protocols were approved by the UCSF Committee on Animal Research and conformed to National Institutes of Health Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. All efforts were made to minimize the number of animals used and their suffering.

Nociceptive testing

The nociceptive flexion reflex was quantified with an Ugo Basile Analgesymeter® (Stoelting, Chicago, IL, USA), which applies a linearly increasing mechanical force to the dorsum of the rat’s hind paw. Rats were acclimatized to the testing conditions as described previously (Aley and Levine, 1999, Aley, et al., 2001). They were allowed to crawl into a cylindrical transparent acrylic® restrainer that has triangular side ports allowing the rat’s hind legs to be extended for exposure of the paws to the test stimulus. The mechanical nociceptive threshold, which was defined as the force in grams at which the rat withdrew its paw was determined before and at different times after each treatment. The effect of test agents is expressed as mean of the percentage reduction in paw-withdrawal threshold [(test reading – saline treated control reading)/saline treated control reading ×100] as well as absolute value (grams). Both paws were treated and measurement from each paw was considered as an independent measure, thus the ‘n’ values represent number of paws. Each experiment was performed on a separate group of rats and each paw injected only once, with either saline (control) or endothelin-1 (experimental). Paw withdrawal thresholds of saline treated rats, measured in parallel with endothelin treated rats, served as a control group. Animals were randomly assigned to an experimental group. On day 1 paw-withdrawal threshold (mean ± SEM in gm) of the naïve rats used in these experiments was 109± 1.7 g (male, n = 24) and 108±1.6 g (female, n = 18). In general, paw-withdrawal threshold after treatment is denoted as the average of 4 readings, taken at 5 min inter-stimulus intervals; these four readings are not significantly different from one another for a particular time point and for a particular (pronociceptive) treatment. However, in a previous study (Joseph, et al., 2011), we found that after ET-1administration, repeated mechanical stimulation to test nociceptive threshold causes a further marked decrease in paw-withdrawal threshold (i.e., a progressive increase in mechanical hyperalgesia from reading 1 to reading 4 (Joseph, et al., 2011)). Therefore, in the current experiments comparisons are made between the paw withdrawal thresholds of male, female and ovariectomized (OVX) female rats, with single readings (first reading establishes the level of hyperalgesia) of nociceptive threshold as well as the other three readings (taken at 5’ intervals, to establish stimulus induced enhancement of hyperalgesia (SIEH)) as well as the average of the four readings performed at different time points. The three groups of rats (male, female and OVX female) were used to evaluate for sexual dimorphism in endothelin hyperalgesia and SIEH.

Ovariectomy

Three-week-old female rats were ovariectomized through bilateral upper flank incisions (Joseph and Levine, 2003, Joseph and Levine, 2003). The ovarian bundles were tied off with 4-0 silk sutures and the ovaries removed. The fascia was closed with 5-0 silk sutures and the skin closed with surgical wound clips. These procedures were carried out under inhalation anesthesia (2% isoflurane in 98% oxygen; Matrix, Orchard Park, NY, USA). Ovariectomized and sham operated rats were used in experiments, 6 weeks after surgery to allow re-equilibration of tissue estrogen stores.

Drugs

The drug employed in this study was endothelin-1 (ET-1, Sigma-Aldrich, and St. Louis, MO). It was dissolved in saline and administered by intradermal (i.d.) injection on the dorsum of the hind paw. The dose of ET-1 employed in these experiments (100 ng) was based on a dose response experiment performed during our previous study of endothelin hyperalgesia (Joseph, et al., 2011). ET-1 was administered in a volume of 5 µl using a 30-gauge hypodermic needle attached to a micro-syringe (Hamilton, Reno, NV) by PE-10 tubing.

Statistical analysis

In all experiments, the dependent variable was change in paw withdrawal threshold, represented in grams and as percentage change from the mean value of the saline treated rats paw withdrawal threshold. Group data are represented as mean ± SEM. Statistical significance was determined by two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s post hoc test; a p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. In analyzing the pronociceptive effect of ET-1, the two factors in question were gender and time-related differences, and in analyzing SIEH, the two factors in question were gender and repeated stimulus (number of readings).

RESULTS

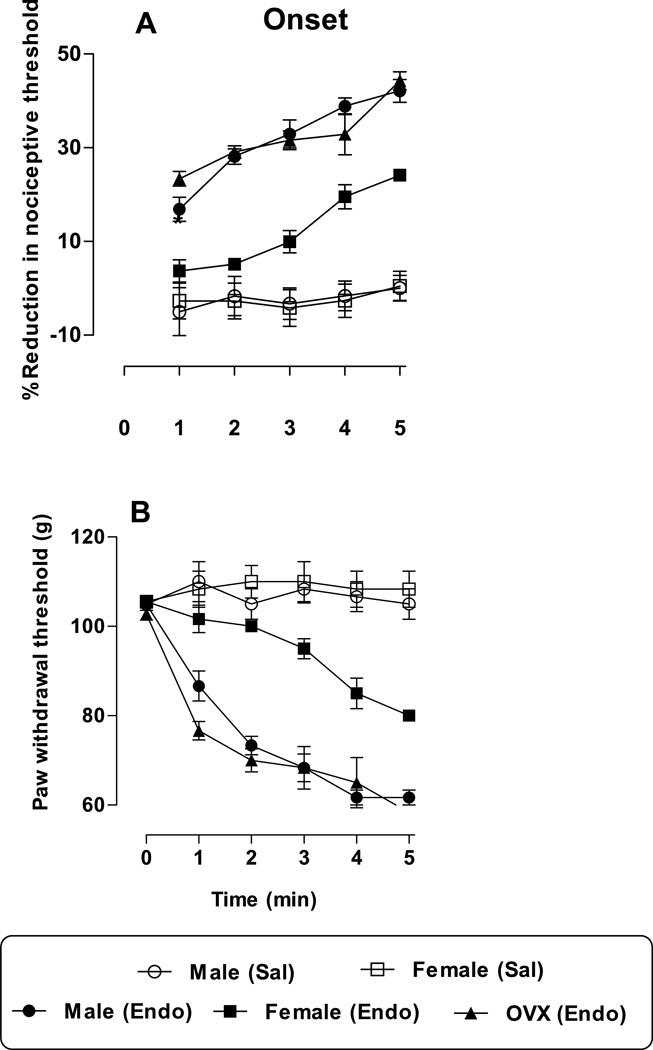

Onset of ET-1 hyperalgesia

Intradermal injection of ET-1 (100 ng) induced significant mechanical hyperalgesia in male, female and ovariectomized female (OVX female) rats. In male and OVX female rats, the onset of hyperalgesia was rapid (<1 min), while in gonad intact female rats, significant reduction in paw withdrawal threshold did not occur until 4 min after ET-1 administration (Fig. 1A (%) and B (g), n=6 per group), (male vs. female, P<0.001; female vs. OVX female p<0.001). At every point (1–5 min) there was a significant time (F4,125 = 169.27; p<0.0001) and sex (F4,125 =18.60; p<0.0001) dependent difference in endothelin-induced hyperalgesia. Saline treatment did not significantly change baseline nociceptive threshold in male and female rats (p > 0.05).

Figure 1. Latency to onset of endothelin-induced mechanical hyperalgesia.

Paw withdrawal thresholds are measured at one-minute inter-trial intervals after the intradermal (i.d.) administration of endothelin-1 (100 ng) or saline, to determine latency to onset of hyperalgesia. Each point represents the average reduction in paw withdrawal threshold in % (A) or in grams (B). Endothelin produced significant hyperalgesia in male, female and OVX females, (all p<0.0001, n = 6/group). In intact females, the onset of hyperalgesia was delayed, a significant reduction first occurred at four minutes. Saline treatment showed no significant change in the paw withdrawal threshold (p > 0.05).

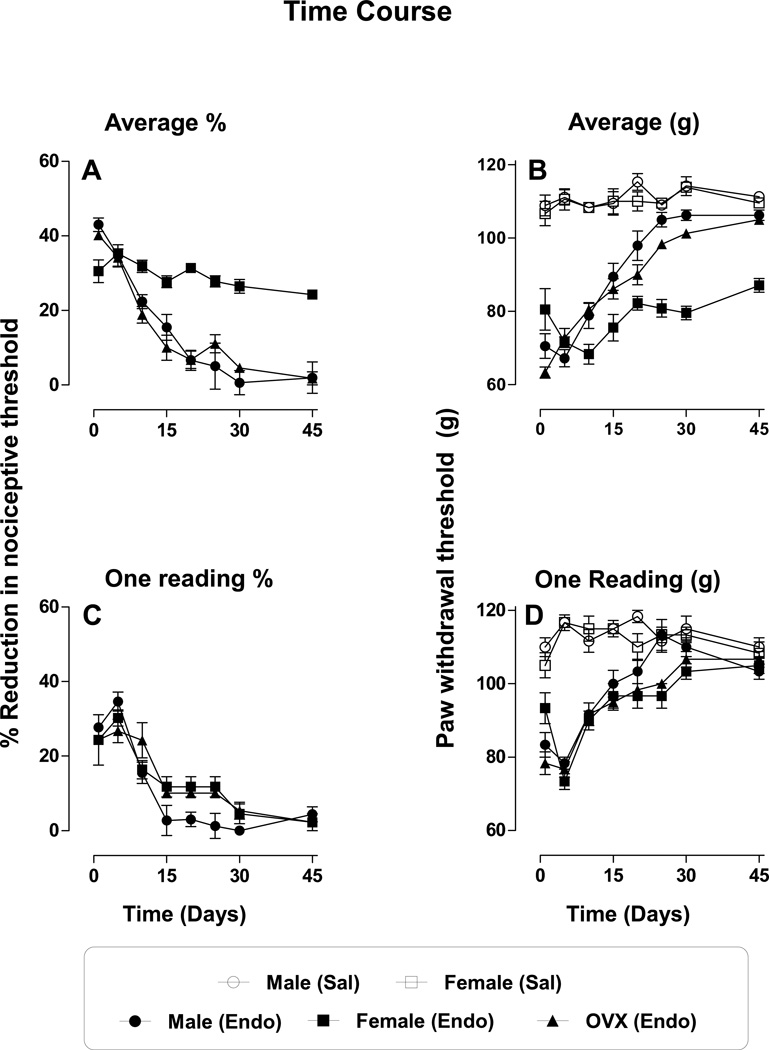

Duration of ET-1hyperalgesia

To characterize the time course of ET-1-induced mechanical hyperalgesia, a single dose of ET-1 (100 ng) was administered to separate groups of male, female and OVX female rats. All rats were injected with the same dose of ET-1 (100 ng, i.d.) and paw-withdrawal thresholds measured four times with a 5’ inter-trial interval, for different time points (1 – 45 days). In male and OVX female rats, ET-1-induced mechanical nociceptive threshold (average of the 4 readings) remained significantly below baseline for over 10 days (male 22±1.9%, P<0.001, OVX female 20±2%, p<0.001 on day 10), with threshold having returned to pre-injection baseline by day 25. However, from day 15 to 45 there was a time ((F4,75 = 4.31; p = 0.0034) and sex (F2,75 = 90.66; p < 0.0001) dependent variation (Fig. 2A (%) and B (g)). In gonad intact female rats, following ET-1 treatment, paw withdrawal threshold remained low (average of the 4 readings, 20±1.6%, p<0.001) even on day 45 (Fig. 2A (%) and B (g), n=6 per group), the last time point examined. Since we have previously shown that repeated mechanical stimulation (4 readings) affects magnitude of endothelin-induced hyperalgesia in male rats, a phenomenon we refer to as stimulus-induced enhancement of hyperalgesia (SIEH) (Joseph et al., 2011), we evaluated separately the magnitude of the hyperalgesia for the first test stimulus at each time point in male, female and OVX female rats. A single stimulus at each time point demonstrated results that did not differ significantly (i.e., no sex dependent difference, F2,86 =2.89; p >0.05, Fig. 2 C (%) and D (g), n=6 per group).

Figure 2. Time course of endothelin-induced mechanical hyperalgesia.

A & B. Each point represents the average of 4 separate measurements from each paw (n = 6/group), with a 5 minute inter-stimulus interval, measured at different time points (1–45 days); the last reading corresponds to the time point indicated. On days 5 and 10, when all four readings are averaged there is a time dependent hyperalgesia (p<0.001) but no sex dependent difference (p > 0.05). However, from day 15 to 45 there was a significant effect of time and sex (A (%) and B (g), for both p < 0.001).

C & D. Each point represents the average of the first of the four readings following administration of endothelin (100 ng, i.d., n = 6/group), at the different time points (1–45 days). In all three groups (male, female and OVX female rats), endothelin (100 ng, i.d.) induced mechanical hyperalgesia, significant for 10 days (all p < 0.0001, C (%) and D (g)) and returned to baseline by day 25. There was no sex dependent difference when first readings were compared (p > 0.05). In saline treated male and female rats, from day 1–45, no significant change in paw withdrawal threshold was observed (p > 0.05).

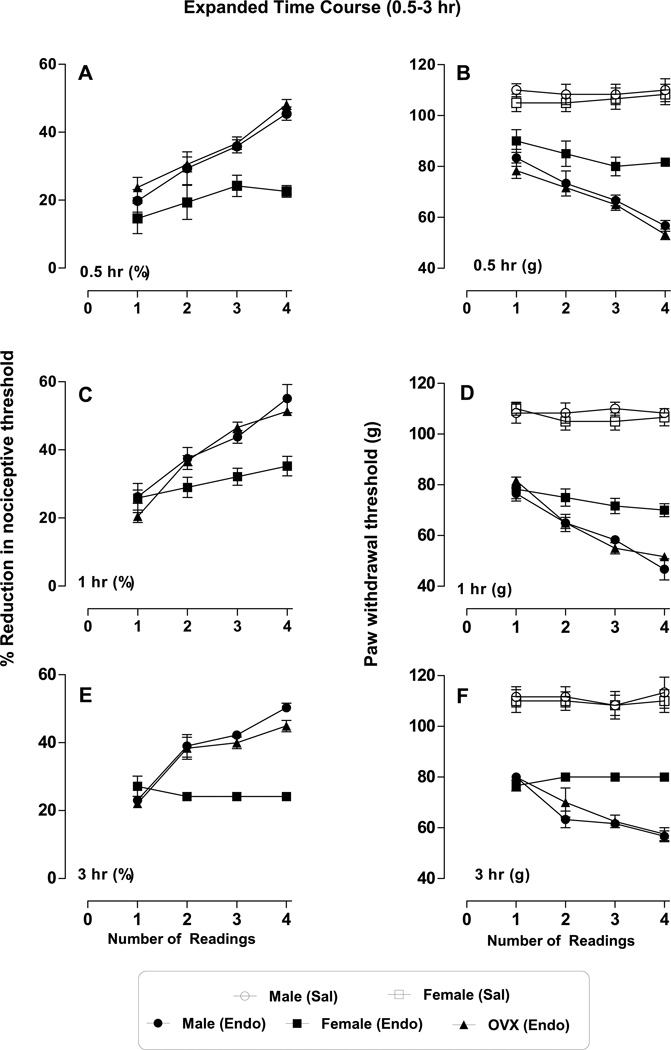

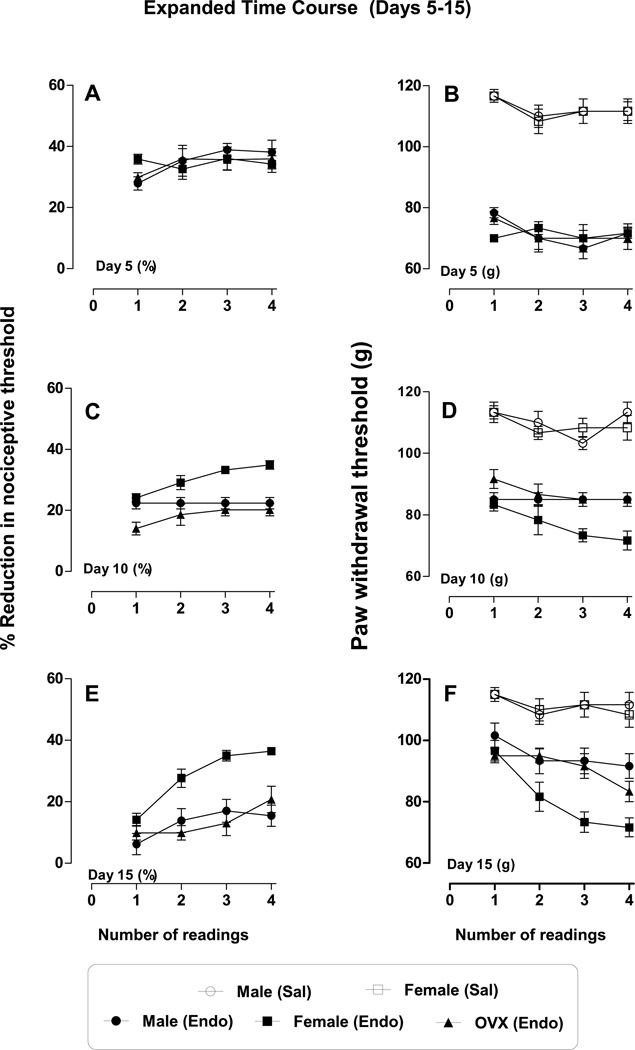

Stimulus-induced enhancement of ET-1 hyperalgesia

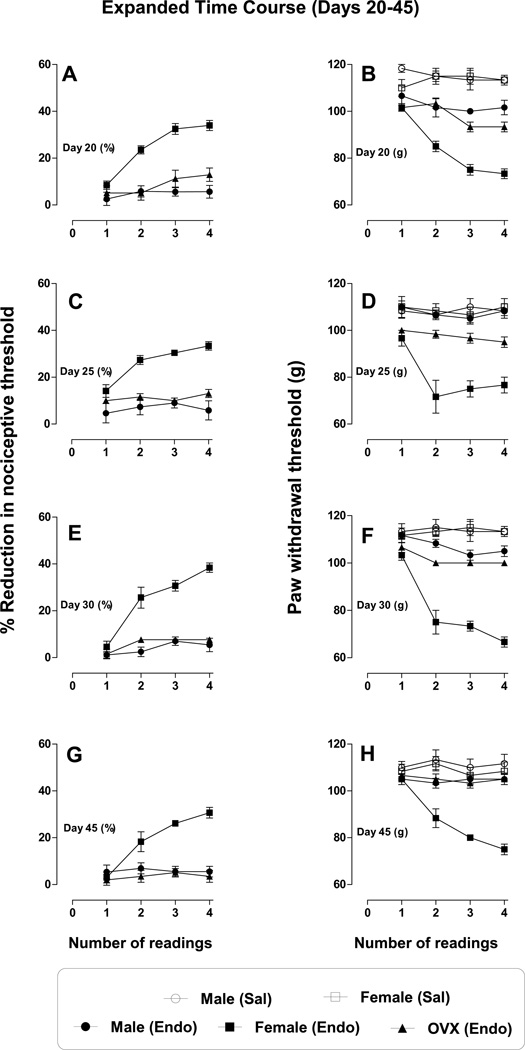

We next compared the effect of repeated mechanical stimulation (4 readings) in male, female and OVX female rats at each time point (1–45 days). All rats were treated with ET-1 (100 ng, i.d.) and 4 paw-withdrawal thresholds measured, with an inter-stimulus interval of 5 minutes, at each time point (i.e., 0.5, 1 and 3 hr. and 5, 10, 15, 20, 25, 30 and 45 days) after ET-1 administration. In male and OVX female rats, repeated mechanical stimulation (i.e., 2nd, 3rd & 4th readings) produced progressively increased hyperalgesia, at 0.5 hr. (Fig. 3A (%), B (g), (F3,60 = 20.55; p < 0.0001)), 1 hr. (Fig. 3C (%), D (g), (F 3,60 = 41.13; p <0.0001)) and at 3 hr. (Fig. 3E (%), F (g), (F 3, 60 = 36.66; p <0.0001)) and there was significant sex dependence at all points 0.5 hr. (Fig. 3A (%), B (g), (F 2, 60 = 25.03; p < 0.0001)), 1 hr. (Fig. 3C (%), D (g), (F 2, 60 = 16.45; p <0.0001)) and at 3 hr. (Fig. 3E (%), F (g), (F2, 60 = 60.47; p <0.0001)). This stimulus-induced enhancement of hyperalgesia (SIEH) was absent in female rats at the same time points (Fig. 3 A, C, E (%), and B, D, F (g), respectively, n = 6 per group). On day 5, though significant hyperalgesia was present in all three groups, there was no significant stimulus-induced enhancement of hyperalgesia (Fig. 4 A (%) and B (g), p >0.05; n = 6 per group). However, starting from day 10 gonad-intact female rats demonstrated stimulus-induced enhancement of hyperalgesia (F3,60 = 4.78; p < 0.0047) and sex dependence (F2,60 =36.84; p < 0.0001; Fig. 4 C (%) & D (g), n = 6)), which became highly significant, when assessed on days 15 (F3,60 = 42.10; p < 0.0001; Fig. 4 E (%) & F (g)), 20, 25, 30 and 45 (Fig. 5A, C, E, G (%) & B, D, F, H (g), respectively, p < 0.0001 for all; n = 6/group)), while SIEH was undetectable in males and gonadectomized females over the same time period. On all these days, paw withdrawal threshold of ET-1 treated female rats differed from that of male and OVX female rats, which was significantly sex dependent (day15, F2,60 =31.08; p < 0.0001; day 20, F2.60 =66.25; p < 0.0001; day 25, F2,60 = 71.58; p < 0.0001; day 30, F2,60 =107.79; p < 0.0001; and, day 45, F2,60 = 48.09; p < 0.0001).

Figure 3. Effect of repeated mechanical stimulation on endothelin-induced hyperalgesia, (0.5–3 hour - expanded results).

Four paw withdrawal thresholds were measured with an inter-stimulus interval of 5 min, at different time points (0.5–3 hr.), in male, female and OVX female rats, the last reading corresponding to the time point indicated on the graph. Paw withdrawal threshold (average of 4 readings) at each point is plotted separately to depict the effect of a repeated stimulus. Repeated stimulation progressively increased the hyperalgesia at 0.5 hr. (A (%), B (g), (p < 0.0001)), 1 hr. (C (%), D (g), (p < 0.0001)) and at 3 hr. (E (%), F (g), (p <0.0001)) and this increase in hyperalgesia is sex dependent at all these points: 0.5 hr. (A (%), B (g), (p < 0.0001)), 1 hr. (C (%), D (g), (p < 0.0001)) and at 3 hr. (E (%), F (g), (p <0.0001)).

Figure 4. Effect of repeated mechanical stimulation on endothelin-induced hyperalgesia, (Day 5–15 - expanded results).

Four paw withdrawal thresholds were measured with an inter-stimulus interval of 5 min, on day 5, 10 and 15, in male, female and OVX female rats. Each stimulus effect is separately plotted to depict the repeated stimulus effect. There was no repeated stimulus induced or sex dependent (p > 0.05) difference in hyperalgesia on day 5 (A (%), B (g)) in all three groups (male, female and OVX female)) of rats. On day 10 (C (%), D (g)), there was a significant effect of repeated stimulus (p < 0.0047) and sex (p < 0.0001). A similar effect was observed on day 15 (E (%), F (g), both p < 0.0001)).

Figure 5. Effect of repeated mechanical stimulation on endothelin-induced hyperalgesia, (Day 20–45 - expanded results).

Four paw withdrawal thresholds were measured with an inter-stimulus interval of 5 min, on day 20, 25, 30 and 45, in male, female and OVX female rats. Each stimulus effect is separately plotted to depict the repeated stimulus effect as well as to compare the effect in different groups. From day 20–45 there was both stimulus induced (day 20 A (%), B (g), p < 0.0001); day 25 C (%), D (g), (p < 0.0009); day 30 E (%), F (g), p < 0.0001) and day 45 G (%), H (g), p < 0.0001), and sex dependent (day 20 A (%), B (g), p < 0.0001), day 25 C (%), D (g), (p < 0.0001); day 30 E (%), F (g), (p < 0.0001) and day 45 G (%), H (g), p < 0.0001)) difference. From day 25, in male and OVX female rats, no hyperalgesia was observed, but naïve female rats continued to be hyperalgesic and the repeated stimulus progressively increased the hyperalgesia.

Discussion

Since some pain syndromes are sexually dimorphic (Kaski and Perez Fernandez, 2002, Noori and Kabbani, 2003), in the present experiments we have compared the nociceptive effects of ET-1 in male and female rats, as well as established ovarian dependence for observed sex differences. In comparing the effects of ET-1 on mechanical nociceptive threshold in the female and male rat, we found that while ET-1 produces mechanical hyperalgesia of similar peak magnitude in both sexes, the latency to onset and duration are markedly different. In males, while onset was much more rapid, duration was shorter.

While different signaling mechanisms in the primary afferent nociceptor might explain the markedly slower onset and longer duration of hyperalgesia in the female, it is also possible that ET-1-induced hyperalgesia in the female involves indirect as well as direct mechanisms, as has been demonstrated for other hyperalgesic agents (e.g., bradykinin and leukotriene B4; (Levine, et al., 1986, Taiwo and Levine, 1988)). Potential indirect targets for stimulus-induced enhancement of ET-1 hyperalgesia are the endothelial cell and postganglionic sympathetic neuron, both of which are highly sexually dimorphic (Damon, 1998, Vera and Nadelhaft, 1992), contain endothelin receptors (Muller, et al., 2002, Radin, et al., 2002) and have been implicated in peripheral pain mechanisms (Janig and Kollmann, 1984, Kinnman and Levine, 1995). And the endothelial cell has also been shown to respond to mechanical stimulation (Diamond, et al., 1994, Yegutkin, et al., 2000) releasing mediators, some of which are pronociceptive (e.g. prostaglandin I2 (prostacyclin), endothelial-derived relaxing factor (nitric oxide) and endothelin) (Bauer and Sotnikova, 2010, Sharma, et al., 2010).

As previously reported, the mechanical stimulus used for the measurement of nociceptive threshold had an effect on ET-1 induced mechanical hyperalgesia (Joseph, et al., 2011) here found to be markedly sexually dimorphic. We have previously shown that in the male rat, for the first 3–4 hours after intradermal injection of ET-1, repeated application of the used to measure nociceptive threshold stimulus produced a further enhancement of mechanical hyperalgesia (Joseph, et al., 2011). Thus, because the paw withdrawal threshold decreases with repeated stimulation, the intensity of the stimulus causing the paw withdrawal at the fourth and final stimulus is markedly lower than that at the first application of the mechanical stimulus.

Over a period of weeks, while a single stimulus (i.e., the first measurement of nociceptive threshold) produced a similar nociceptive effect in all three endothelin treated groups (male, female, OVX female), repeated stimulation induced and/or enhanced mechanical hyperalgesia, which differed among these groups (Fig. 2 A–D and expanded results in Figs. 3, 4 and 5). Such induction and enhancement of hyperalgesia was not seen in saline treated rats. The marked dissociation of time course of hyperalgesia and stimulus-induced enhancement of hyperalgesia in male and female rats raises the possibility that this stimulus-induced enhancement may be by action of ET-1 on a cell in the skin other than the peripheral terminal of the primary afferent nociceptor. One intriguing possibility, related to the marked sexual dimorphism in vascular function in females and males (Denton and Baylis, 2007, Goel, et al., 2008, Wang, et al., 2010), which is substantially sex hormone dependent (Goel, et al., 2008), is the blood vessel itself. Given that the endothelial cell is both a source and target of endothelin, it is certainly well-placed to mediate such an indirect effect. This would be similar to what has recently been proposed for the role of the keratinocyte in peripheral nociceptive mechanism (Lee and Caterina, 2005, Radtke, et al., 2010, Zhao, et al., 2008). Experiments are currently ongoing to evaluate for indirect mechanisms that mediate stimulus-induced enhancement of mechanical hyperalgesia.

Since many sexually dimorphic effects in pain and analgesia are ovarian dependent (Berkley, et al., 2007, Fan, et al., 2009, Joseph and Levine, 2003, Khasar, et al., 2005, Lu, et al., 2009), we evaluated the effect of ovariectomy on our observed sexual dimorphism for ET-1 induced mechanical hyperalgesia and stimulus-induced enhancement of ET-1 hyperalgesia. Consistent with this literature, ovariectomy completely eliminated the observed difference in ET-1 effects in male and female rats. However, the role of individual sex hormones or other ovarian mediators in the sexual dimorphism of the pronociceptive effects of ET-1 remains to be evaluated.

While the pronociceptive effect of ET-1 has been shown to be sexually dimorphic in the neonatal rat (McKelvy, et al., 2007, McKelvy and Sweitzer, 2009), to the best of our knowledge this is the first study to compare its nociceptive effects in adult males and females of any species, or to evaluate for ovarian dependence. In the adult rat the nociceptive effect of ET-1 was found to be markedly sexually dimorphic, though not so much in terms of the magnitude of hyperalgesia as in the time course and response to repeated mechanical stimulation. ET-1 induced mechanical hyperalgesia was more rapid in onset in the male rat and more prolonged in the female. And, male and female rats had completely non-overlapping time courses for stimulus induced enhancement of hyperalgesia. All sexual dimorphic effects were found to be ovarian dependent, as ovariectomized females had a phenotype indistinguishable from that in the gonad intact male. Stimulus-induced enhancement of hyperalgesia did not occur in female rats until day 10 and was still present, without attenuation, on day 45. This phenomenon is compatible with an indirect mechanism, a suggestion supported by the presence of ET receptors on other cells in the skin that have been implicated in peripheral pain mechanisms, for example endothelial (Hans, et al., 2009) and postganglionic sympathetic neurons (Belenky and Devor, 1997). The function of both cell types are known to be sexually dimorphic (Khasar, et al., 2005, McKelvy, et al., 2007, McKelvy and Sweitzer, 2009) and at least for endothelial cells, also demonstrate mechanical sensitivity (Denton and Baylis, 2007, Goel, et al., 2008, Wang, et al., 2010) capable of leading to the release of pronociceptive molecules (e.g., prostaglandin, nitric oxide, and cytokines (Bauer and Sotnikova, 2010, Matsui, et al., 2010, Wang, et al., 2010).

Highlights.

Endothelin-1 hyperalgesia is subject to stimulus-induced enhancement.

This stimulus-induced enhancement is sexually dimorphic.

Endothelin-1 contributes to sexual dimorphism in pain syndromes.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a grant from the U.S. National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

There is no actual or potential conflict of interest including financial and personal

REFERENCES

- Aley KO, Levine JD. Role of protein kinase A in the maintenance of inflammatory pain. J Neurosci. 1999;19:2181–2186. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-06-02181.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aley KO, Martin A, McMahon T, Mok J, Levine JD, Messing RO. Nociceptor sensitization by extracellular signal-regulated kinases. J Neurosci. 2001;21:6933–6939. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-17-06933.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arai H, Hori S, Aramori I, Ohkubo H, Nakanishi S. Cloning and expression of a cDNA encoding an endothelin receptor. Nature. 1990;348:730–732. doi: 10.1038/348730a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer V, Sotnikova R. Nitric oxide - the endothelium-derived relaxing factor and its role in endothelial functions. Gen Physiol Biophys. 2010;29:319–340. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belenky M, Devor M. Association of postganglionic sympathetic neurons with primary afferents in sympathetic-sensory co-cultures. J Neurocytol. 1997;26:715–731. doi: 10.1023/a:1018510214165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkley KJ, McAllister SL, Accius BE, Winnard KP. Endometriosis-induced vaginal hyperalgesia in the rat: effect of estropause, ovariectomy, and estradiol replacement. Pain. 2007;132(Suppl 1):S150–S159. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2007.09.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chichorro JG, Fiuza CR, Bressan E, Claudino RF, Leite DF, Rae GA. Endothelins as pronociceptive mediators of the rat trigeminal system: role of ETA and ETB receptors. Brain Res. 2010;1345:73–83. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.04.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damon DH. Postganglionic sympathetic neurons express endothelin. Am J Physiol. 1998;274:R873–R878. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1998.274.3.R873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denton K, Baylis C. Physiological and molecular mechanisms governing sexual dimorphism of kidney, cardiac, and vascular function. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2007;292:R697–R699. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00766.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond SL, Sachs F, Sigurdson WJ. Mechanically induced calcium mobilization in cultured endothelial cells is dependent on actin and phospholipase. Arterioscler Thromb. 1994;14:2000–2006. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.14.12.2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enseleit F, Hurlimann D, Luscher TF. Vascular protective effects of angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors and their relation to clinical events. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2001;37(Suppl 1):S21–S30. doi: 10.1097/00005344-200109011-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan J, Yu LH, Zhang Y, Ni X, Ma B, Burnstock G. Estrogen altered visceromotor reflex and P2X(3) mRNA expression in a rat model of colitis. Steroids. 2009;74:956–962. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2009.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flinsenberg TW, van der Sterren S, van Cleef AN, Schuurman MJ, Agren P, Villamor E. Effects of sex and estrogen on chicken ductus arteriosus reactivity. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2010;298:R1217–R1224. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00839.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goel A, Thor D, Anderson L, Rahimian R. Sexual dimorphism in rabbit aortic endothelial function under acute hyperglycemic conditions and gender-specific responses to acute 17beta-estradiol. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2008;294:H2411–H2420. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01217.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hans G, Schmidt BL, Strichartz G. Nociceptive sensitization by endothelin-1. Brain Res Rev. 2009;60:36–42. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2008.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue A, Yanagisawa M, Kimura S, Kasuya Y, Miyauchi T, Goto K, Masaki T. The human endothelin family: three structurally and pharmacologically distinct isopeptides predicted by three separate genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989;86:2863–2867. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.8.2863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janig W, Kollmann W. The involvement of the sympathetic nervous system in pain. Possible neuronal mechanisms. Arzneimittelforschung. 1984;34:1066–1073. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joseph EK, Gear RW, Levine JD. Mechanical stimulation enhances endothelin-1 hyperalgesia. Neuroscience. 2011;178:189–195. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2011.01.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joseph EK, Levine JD. Sexual dimorphism for protein kinase c epsilon signaling in a rat model of vincristine-induced painful peripheral neuropathy. Neuroscience. 2003;119:831–838. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(03)00203-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joseph EK, Levine JD. Sexual dimorphism in the contribution of protein kinase C isoforms to nociception in the streptozotocin diabetic rat. Neuroscience. 2003;120:907–913. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(03)00400-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kallakuri S, Kreipke CW, Schafer PC, Schafer SM, Rafols JA. Brain cellular localization of endothelin receptors A and B in a rodent model of diffuse traumatic brain injury. Neuroscience. 2010;168:820–830. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2010.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaski JC, Perez Fernandez R. [Microvascular angina and syndrome X] Rev Esp Cardiol. 2002;55(Suppl 1):10–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khasar SG, Dina OA, Green PG, Levine JD. Estrogen regulates adrenal medullary function producing sexual dimorphism in nociceptive threshold and beta-adrenergic receptor-mediated hyperalgesia in the rat. Eur J Neurosci. 2005;21:3379–3386. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.04158.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khodorova A, Zou S, Ren K, Dubner R, Davar G, Strichartz G. Dual Roles for Endothelin-B Receptors in Modulating Adjuvant-Induced Inflammatory Hyperalgesia in Rats. Open Pain J. 2009;2:30–40. doi: 10.2174/1876386300902010030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinnman E, Levine JD. Sensory and sympathetic contributions to nerve injury-induced sensory abnormalities in the rat. Neuroscience. 1995;64:751–767. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(94)00435-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaPrairie JL, Murphy AZ. Long-term impact of neonatal injury in male and female rats: Sex differences, mechanisms and clinical implications. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2010;31:193–202. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2010.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauria G, Lombardi R, Camozzi F, Devigili G. Skin biopsy for the diagnosis of peripheral neuropathy. Histopathology. 2009;54:273–285. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2008.03096.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laziz I, Larbi A, Grebert D, Sautel M, Congar P, Lacroix MC, Salesse R, Meunier N. Endothelin as a Neuroprotective Factor in the Olfactory Epithelium. Neuroscience. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2010.10.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H, Caterina MJ. TRPV channels as thermosensory receptors in epithelial cells. Pflugers Arch. 2005;451:160–167. doi: 10.1007/s00424-005-1438-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine JD, Lam D, Taiwo YO, Donatoni P, Goetzl EJ. Hyperalgesic properties of 15-lipoxygenase products of arachidonic acid. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1986;83:5331–5334. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.14.5331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loesch A. Localisation of endothelin-1 and its receptors in vascular tissue as seen at the electron microscopic level. Curr Vasc Pharmacol. 2005;3:381–392. doi: 10.2174/157016105774329381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu YC, Chen CW, Wang SY, Wu FS. 17Beta-estradiol mediates the sex difference in capsaicin-induced nociception in rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2009;331:1104–1110. doi: 10.1124/jpet.109.158402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsui T, Svensson CI, Hirata Y, Mizobata K, Hua XY, Yaksh TL. Release of prostaglandin E(2) and nitric oxide from spinal microglia is dependent on activation of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase. Anesth Analg. 2010;111:554–560. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e3181e3a2a2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKelvy AD, Mark TR, Sweitzer SM. Age- and sex-specific nociceptive response to endothelin-1. J Pain. 2007;8:657–666. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2007.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKelvy AD, Sweitzer SM. Endothelin-1 exposure on postnatal day 7 alters expression of the endothelin B receptor and behavioral sensitivity to endothelin-1 on postnatal day 11. Neurosci Lett. 2009;451:89–93. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2008.12.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millecamps M, Laferriere A, Ragavendran JV, Stone LS, Coderre TJ. Role of peripheral endothelin receptors in an animal model of complex regional pain syndrome type 1 (CRPS-I) Pain. 2010;151:174–183. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller V, Losonczy G, Heemann U, Vannay A, Fekete A, Reusz G, Tulassay T, Szabo AJ. Sexual dimorphism in renal ischemia-reperfusion injury in rats: possible role of endothelin. Kidney Int. 2002;62:1364–1371. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2002.kid590.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noori A, Kabbani S. Endothelins and coronary vascular biology. Coron Artery Dis. 2003;14:491–494. doi: 10.1097/00019501-200311000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quang PN, Schmidt BL. Endothelin-A receptor antagonism attenuates carcinoma-induced pain through opioids in mice. J Pain. 2010;11:663–671. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2009.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radin MJ, Holycross BJ, Sharkey LC, Shiry L, McCune SA. Gender modulates activation of renin-angiotensin and endothelin systems in hypertension and heart failure. J Appl Physiol. 2002;92:935–940. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00558.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radtke C, Vogt PM, Devor M, Kocsis JD. Keratinocytes acting on injured afferents induce extreme neuronal hyperexcitability and chronic pain. Pain. 2010;148:94–102. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2009.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Risling M, Dalsgaard CJ, Frisen J, Sjogren AM, Fried K. Substance P-, calcitonin gene-related peptide, growth-associated protein-43, and neurotrophin receptor-like immunoreactivity associated with unmyelinated axons in feline ventral roots and pia mater. J Comp Neurol. 1994;339:365–386. doi: 10.1002/cne.903390306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubanyi GM, Polokoff MA. Endothelins: molecular biology, biochemistry, pharmacology, physiology, and pathophysiology. Pharmacol Rev. 1994;46:325–415. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakurai T, Yanagisawa M, Takuwa Y, Miyazaki H, Kimura S, Goto K, Masaki T. Cloning of a cDNA encoding a non-isopeptide-selective subtype of the endothelin receptor. Nature. 1990;348:732–735. doi: 10.1038/348732a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez A, Recio P, Orensanz LM, Bustamante S, Navarro-Dorado J, Climent B, Benedito S, Garcia-Sacristan A, Prieto D, Hernandez M. Mechanisms involved in the effects of endothelin-1 in pig prostatic small arteries. Eur J Pharmacol. 2010;640:190–196. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2010.04.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma J, Turk J, McHowat J. Endothelial cell prostaglandin I(2) and platelet-activating factor production are markedly attenuated in the calcium-independent phospholipase A(2)beta knockout mouse. Biochemistry. 2010;49:5473–5481. doi: 10.1021/bi100752u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taiwo YO, Levine JD. Characterization of the arachidonic acid metabolites mediating bradykinin and noradrenaline hyperalgesia. Brain Res. 1988;458:402–406. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(88)90487-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taube C, Schirner M. Sexual dimorphism in blood pressure response to thromboxane agonist U 46619 and to endothelin. Agents Actions Suppl. 1992;37:369–375. doi: 10.1007/978-3-0348-7262-1_50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vera PL, Nadelhaft I. Afferent and sympathetic innervation of the dome and the base of the urinary bladder of the female rat. Brain Res Bull. 1992;29:651–658. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(92)90134-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang HH, Hsieh HL, Yang CM. Nitric oxide production by endothelin-1 enhances astrocytic migration via the tyrosine nitration of matrix metalloproteinase-9. J Cell Physiol. 2010 doi: 10.1002/jcp.22560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Bingaman S, Huxley VH. Intrinsic sex-specific differences in microvascular endothelial cell phosphodiesterases. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2010;298:H1146–H1154. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00252.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werner MF, Trevisani M, Campi B, Andre E, Geppetti P, Rae GA. Contribution of peripheral endothelin ETA and ETB receptors in neuropathic pain induced by spinal nerve ligation in rats. Eur J Pain. 2010;14:911–917. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2010.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanagisawa M, Masaki T. Molecular biology and biochemistry of the endothelins. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1989;10:374–378. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(89)90011-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yegutkin G, Bodin P, Burnstock G. Effect of shear stress on the release of soluble ecto-enzymes ATPase and 5'-nucleotidase along with endogenous ATP from vascular endothelial cells. Br J Pharmacol. 2000;129:921–926. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao P, Barr TP, Hou Q, Dib-Hajj SD, Black JA, Albrecht PJ, Petersen K, Eisenberg E, Wymer JP, Rice FL, Waxman SG. Voltage-gated sodium channel expression in rat and human epidermal keratinocytes: evidence for a role in pain. Pain. 2008;139:90–105. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2008.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]