Abstract

The spirochetes in the Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato genospecies group cycle in nature between tick vectors and vertebrate hosts. The current assemblage of B. burgdorferi sensu lato, of which three species cause Lyme disease in humans, originated from a rapid species radiation that occurred near the origin of the clade. All of these species share a unique genome structure that is highly segmented and predominantly composed of linear replicons. One of the circular plasmids is a prophage that exists as several isoforms in each cell and can be transduced to other cells, likely contributing to an otherwise relatively anemic level of horizontal gene transfer, which nevertheless appears to be adequate to permit strong natural selection and adaptation in populations of B. burgdorferi. Although the molecular genetic toolbox is meager, several antibiotic-resistant mutants have been isolated, and the resistance alleles, as well as some exogenous genes, have been fashioned into markers to dissect gene function. Genetic studies have probed the role of the outer membrane lipoprotein OspC, which is maintained in nature by multiple niche polymorphisms and negative frequency-dependent selection. One of the most intriguing genetic systems in B. burgdorferi is vls recombination, which generates antigenic variation during infection of mammalian hosts.

Keywords: transformation, transduction, recombination, horizontal gene transfer, spirochete, Lyme disease

INTRODUCTION

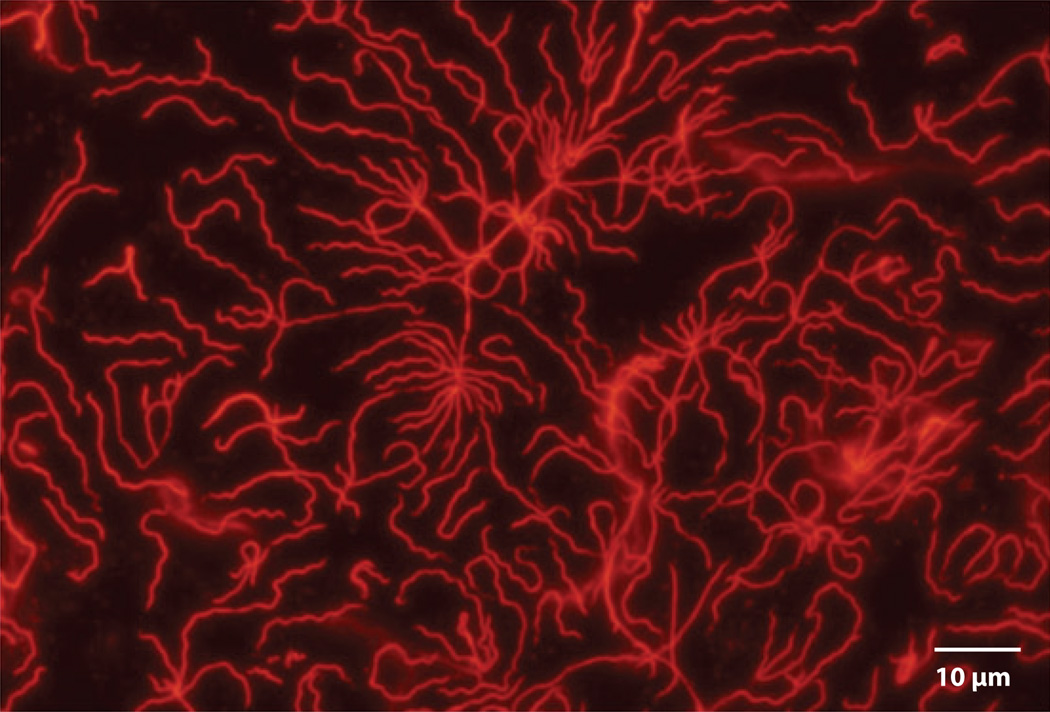

Borrelia burgdorferi, the causative agent of Lyme disease (Lyme borreliosis), belongs to an ancient phylum of bacteria called spirochetes. The long, thin serpentine morphology is the signature feature shared among spirochetes (Figure 1), whereas its many other characteristics, such as genome organization, lifestyle, and disease pathogenesis (if present), are quite diverse. Borrelia species are the only members of this phylum that must be transmitted among vertebrate hosts, including humans, by an arthropod vector.

Figure 1.

Live Borrelia burgdorferi sensu stricto stained with wheat germ agglutinin Alexa Fluor® 594.

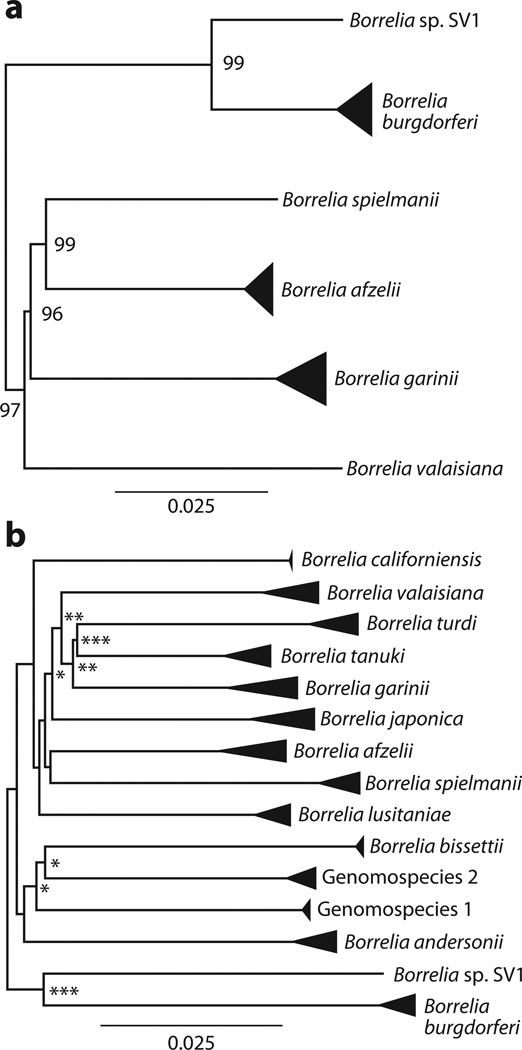

Several B. burgdorferi sensu lato genospecies have been described (Figure 2) (8, 29, 58, 79, 80, 96, 100, 104, 123, 134, 168), all of which are transmitted among vertebrate wildlife species by ixodid ticks. However, only three of these species, B. burgdorferi sensu stricto, Borrelia garinii, and Borrelia afzelii, are regularly associated with human infections (27, 165, 172). The remaining genospecies also infect multiple vertebrate species but are rarely found in human patients (43). Several Borrelia isolates may be novel genospecies, including genomospecies 1 and genomospecies 2 from California (122) and a European group (102, 127).

Figure 2.

Bayesian phylogenies of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato; triangles represent the diversity within genospecies. The rapid burst of speciation that occurred early in the evolutionary history of the group can be inferred from both the (a) chromosome sequences and (b) the multilocus phylogenies. Nodes marked with asterisks are supported by posterior probabilities of more than 0.8 (∗), 0.9 (∗∗), and 0.95 (∗∗∗). Figure adapted from Morlon et al. (112).

Although the tempo of diversification has been a principal topic of studies in macroorganisms (137, 151, 153), much less is known about the rates of diversification in the exceedingly diverse and species-rich microbiota. Explosive species radiations appear to be a common pattern of diversification in plant and animal lineages, although the few existing analyses of microbial lineages suggest that the tempo of diversification in prokaryotes may be fundamentally different (103). A recent study found that the Lyme disease group of bacteria, like plants and animals, underwent an explosive species radiation near the origin of the clade, which led to the current assemblage of species (Figure 2) (112).

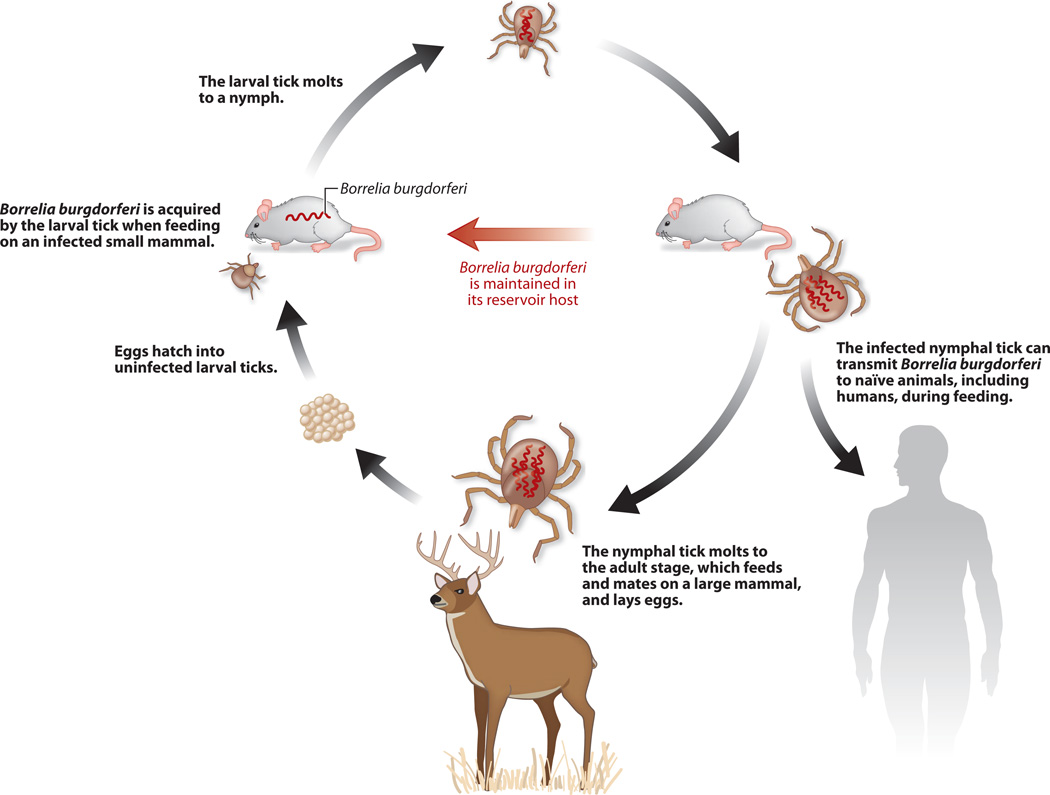

In nature, B. burgdorferi is maintained in an enzootic cycle (Figure 3) between an Ixodes tick vector and a vertebrate host (89, 92, 121, 130). Ixodes larvae acquire B. burgdorferi from an infected animal during the first blood meal because transovarial transmission does not occur. The spirochetes persist in the tick midgut, weathering restricted nutritional conditions following digestion of the blood meal and austere environmental conditions as ticks overwinter. Transmission occurs during nymphal feeding in which the blood meal triggers B. burgdorferi replication, escape from the midgut to the hemocoel, and exit through the salivary glands into the mammalian host, thus completing the enzootic cycle. Nymphs are generally considered to be the relevant vector for human infection, although humans are a dead end host for B. burgdorferi. Transition through the vastly different environments of the enzootic cycle requires not only differential gene regulation (130, 144, 154) but has likely led to molecular adaptations reflected in its curious genome architecture (10, 30, 32, 33, 57).

Figure 3.

Enzootic cycle of Borrelia burgdorferi. Spirochetes are acquired when Ixodes spp. larvae feed on their first vertebrate host, usually a small mammal or bird. Larvae then molt to nymphs, which transmit the spirochetes when they feed on a second vertebrate host. Nymphs molt to adults, which feed on a third vertebrate host. All three stages of ticks feed on humans, which are thought to be incidental hosts, but B. burgdorferi transmission by nymphs is considered to cause most cases of Lyme disease.

The genome of B. burgdorferi is one of the most, if not the most, complex of any bacterium (30, 32, 33, 57). It consists of a ~950-kb linear chromosome and a variable complement of circular plasmids (cps) and linear plasmids (lps) that range in size from 9 to 62 kb. The linear replicons have covalently closed telomeres (10), whose replication requires the telomere resolvase ResT (33, 84). The genome has a low G+C content of ~28%. Most, but not all, housekeeping genes are on the chromosome, whereas the majority of genes encoding lipoproteins expressed on the bacterial outer membrane, presumably mediating transition through the enzootic cycle, are found on the plasmids. The importance of lipoproteins to B. burgdorferi is underscored by their abundance: They represent 7.8% of all open reading frames. In addition, the lipoproteins are differentially expressed during the enzootic cycle (130, 144, 154). Although much work has been done to elucidate the function of an increasing number of genes, many of the predicted open reading frames of the chromosome (~30%), and especially of the plasmids, share no significant homology with any previously annotated genes (30, 57). Each linear plasmid is distinct, but all contain multiple copies of paralogous genes. Pseudogenes and noncoding DNA constitute a significant amount of their sequence, suggesting a genome in flux (30, 32, 57, 85). Although different strains contain a discrete complement of plasmids, and the plasmid content may be shuffled between the linear components, the repertoire of genes remains relatively consistent (32). The plasticity of the linear replicons may be generated, at least in part, by telomere fusion in the reverse of the telomere resolution reaction catalyzed by ResT (85). Some circular and linear plasmids are essential for the enzootic cycle but not for propagation in vitro, such as lp28-1, lp25 and some members of the cp32 family (90, 125, 177); at least some cp32s are prophages that can be transduced, as discussed below. Loss of plasmids during in vitro manipulations represents one of several challenges for developing methodologies to genetically manipulate B. burgdorferi. Notably, cp26 is the only single-copy plasmid known to be essential for in vitro growth: It carries resT, which encodes the telomere resolvase required for replicating linear molecules (33, 84), and it also carries ospC (101, 141), which is required for transmission from tick to vertebrate and infectivity in vertebrates (65, 120, 162, 163).

B. burgdorferi lacks the capacity to synthesize amino acids, nucleotides, fatty acids, and enzyme cofactors, as the genes encoding the enzymes for these pathways were presumably lost during the coevolution with its tick vector and mammalian host (57, 62). Instead, B. burgdorferi is an accomplished importer and scavenger that has at least 52 genes encoding transporters and/or binding proteins of carbohydrates, peptides, and amino acids (142). Additionally, energy is derived by glycolysis and the fermentation of sugars to lactic acid, as the genes encoding the components necessary for the citric acid cycle and oxidative phosphorylation are missing (57, 62). The prevalence of chemotaxis and motility genes, which represent approximately 6%of the genes on the chromosome, highlights the importance of identifying and moving to the correct niche in order to successfully navigate the enzootic cycle (37).

MOLECULAR GENETICS

Molecular genetics of B. burgdorferi commenced approximately ten years after the discovery of the spirochete (26) when the first genetically defined mutants were isolated (139, 140, 147) and the bacterium was first genetically transformed (146). Borreliologists utilized the awesome power of genetics in the fastidious microbe over the ensuing years, applying increasingly more sophisticated reverse genetics tools originally developed in model organisms (136). Forward genetic screens have still been mostly limited to antibiotic resistance as a phenotype. However, the development of transposon mutagenesis (15, 97, 113, 116, 161) and inducible gene expression (13, 63, 171) will allow more complex phenotypes, such as infectivity, to be genetically dissected.

The natural exchange of DNA is mediated via transduction of cp32 prophage, at least in vitro (51). Transformation, which is relatively inefficient, has been demonstrated only using artificial conditions in the laboratory (135, 145, 146); however, the spirochete produces membrane blebs that contain DNA (61), which could theoretically be a mechanism of horizontal gene transfer (HGT). There has also been a report of heterologous conjugation in which erythromycin resistance was transferred from B. burgdorferi into two species of gram-positive bacteria, although the mechanism of resistance has not been defined, and the genetic element was not identified (77). In addition to HGT, genetic variation is effectively generated during mammalian infection by an intriguing recombination system at the vlsE locus (45, 97, 177), as discussed in detail below. The recombination machinery can, surprisingly, hop and skip over short sequences (41), and this was previously observed during the site-directed mutagenesis of the gac gene embedded in gyrA (82).

Mutations and Transformation

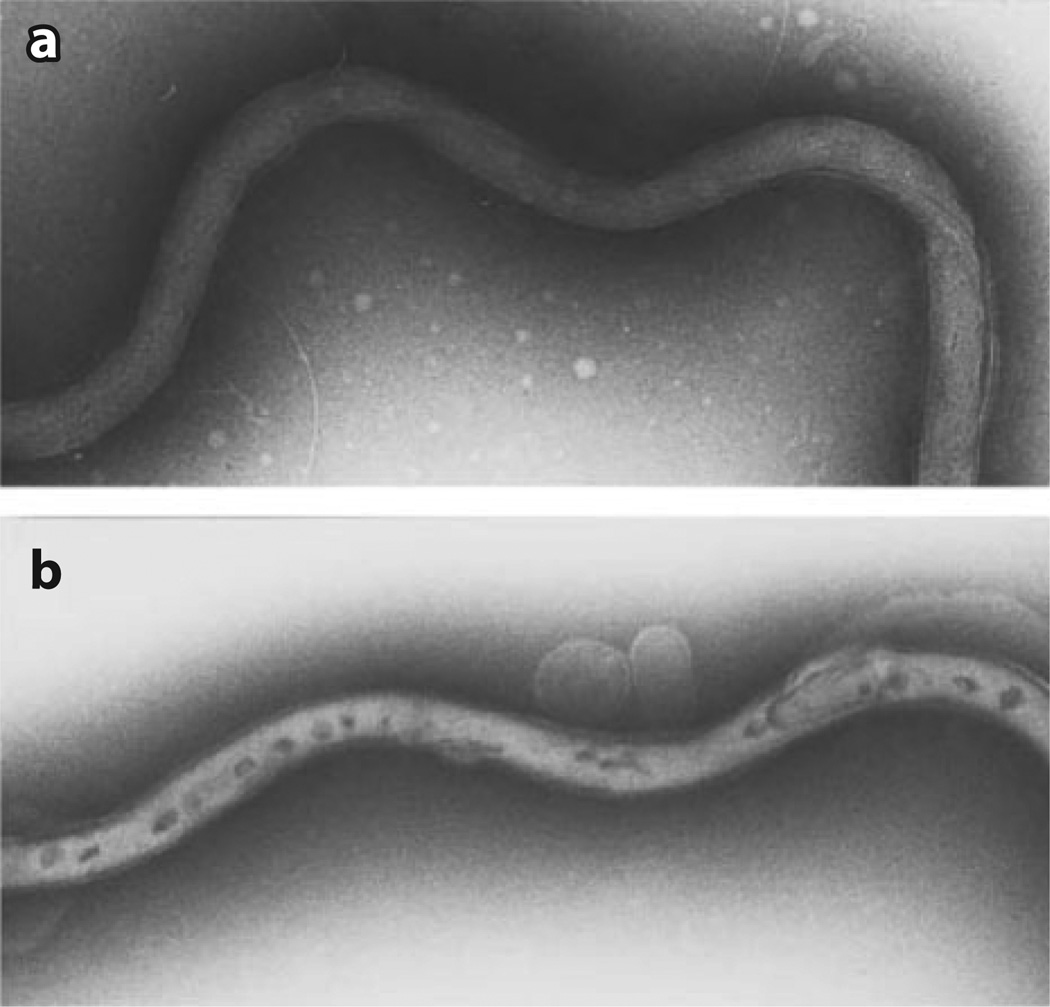

Reverse genetics has, not unexpectedly, proved to be a powerful approach to deciphering the enigmatic physiology of B. burgdorferi, including its fascinating mechanisms of motility (37), gene regulation (144), and linear DNA replication (33), as well as the pathogenesis of Lyme disease (130). Genetic manipulation required a system to transform the spirochete and to select for site-directed mutations, gene disruption by allelic exchange, shuttle vectors, and recombinant endogenous plasmids. B. burgdorferi is typically transformed by electroporation (Figure 4) using standard methodologies (143, 146).

Figure 4.

Electron micrograph of negatively stained Borrelia burgdorferi (a) before and (b) after electroporation. Following electroporation, B. burgdorferi have darkly stained regions, as visualized by transmission electron microscopy, that are thought to be transient pores through which the DNA enters (or leaves) the cell. Reprinted with permission from Samuels & Garon (145).

Almost all B. burgdorferi mutants selected in a phenotypic screen have been those that are resistant to various antibiotics, and the mutations have been mapped to either a topoisomerase or the ribosome (42, 60, 147). However, the first isolated B. burgdorferi mutant lacked flagella and was nonmotile, although a specific mutation was not mapped to a defined locus (140). The first phenotypic selection of B. burgdorferi was resistance to a bacteriostatic antibody, which resulted in isolation of mutants in outer membrane lipoproteins (138, 139). Coumermycin A1 (147), a coumarin that targets the B subunit of DNA gyrase (34, 40, 46, 71), was the first antibiotic used to isolate mutants in B. burgdorferi (147). Coumermycin A1-resistant gyrB mutations map to a conserved residue (arginine 133), which is homologous to GyrB residues mutated in several other coumarin-resistant prokaryotes (147).

In addition to DNA gyrase, most bacteria encode topoisomerase IV, another type II topoisomerase (34, 73). Fluoroquinolone antibiotics, which are not clinically used to treat Lyme disease, target type II topoisomerases (46, 71, 114). Fluoroquinolone resistance maps, in most cases, to a small region in the A subunits of DNA gyrase (GyrA) in gram-negative bacteria or topoisomerase IV (ParC) in gram-positive bacteria (46, 71). Several fluoroquinolone-resistant mutants of B. burgdorferi were isolated with all mutations mapping to parC, strongly suggesting that topoisomerase IV is the primary target of fluoroquinolone antibiotics (60). The mutations are at conserved residues (threonine 69, which is a serine in most bacteria; serine 70; and glutamate 73) that are often mutated in other fluoroquinolone-resistant bacteria.

Spectinomycin targets the small subunit of the ribosome, and resistant mutations map to either the S5 protein or the 16S rRNA. In B. burgdorferi, mutations in the 16S rRNA gene rrs (atA1185 or C1186) confer high-level spectinomycin resistance and occur at a high frequency (42).The closely related aminoglycoside antibiotics kanamycin, gentamicin, and streptomycin also target the ribosome. Kanamycin-resistant and gentamicin-resistant B. burgdorferi have a mutation at A1402 of rrs that confers approximately 100-fold resistance to both antibiotics (42). Streptomycin-resistant mutants have mutations in rpsL (at lysine 88 of the S12 protein) that increase resistance tenfold (42). The frequency of the spectinomycin-resistant mutants is approximately 100-fold higher than the frequency of the aminoglycoside-resistant mutants. The high frequency is likely a result of a lower fitness cost for the spectinomycin-resistant rrs mutations. The spectinomycin-resistant mutants grow at the same rate as wild type without selection and are maintained in mixed cultures for up to 100 generations, whereas the aminoglycoside-resistant mutants are outcompeted at 50 generations and lost within 100 generations (42).

The coumermycin A1-resistant gyrB allele was fashioned into the first selectable marker for genetic transformation (146), and the wild-type rpsL gene in a streptomycin-resistant background was harnessed as the first counterselectable marker (44). Several genes were mutated using gyrB, including ospC (164), gac (82), and others. Coumermycin A1 resistance was also used to show that bacteria could be transformed with short oligonucleotides (145). However, gyrB is no longer utilized by molecular borreliologists as a selectable marker because of experimental limitations, including tedious screening of transformants due to homologous recombination into the chromosomal gyrB locus and pleiotropic effects presumably due to altered DNA topology. For example, gyrB mutants have abnormal expression of groEL (4) and ospC (3); the gyrB mutation is postulated to have suppressed the phenotype of the gac mutant (82). These experimental obstacles were overcome by fusing B. burgdorferi promoters to exogenous antibiotic resistance genes.

The chimeric markers allow for efficient selection of transformants and employ the aphI gene from Tn903, which confers resistance to kanamycin (14); the aadA gene from the Shigella flexneri plasmid R100, which confers resistance to spectinomycin and streptomycin (56); and the aacC1 gene from Tn1696, which confers resistance to gentamicin (54).Note that selection with spectinomycin for transformants carrying the flgBp-aadA hybrid cassette fails because mutations in rrs confer high-level resistance and occur at a high frequency (42), necessitating the use of streptomycin for selection in B. burgdorferi (56). In addition, the ermC gene from the Staphylococcus aureus plasmid pE194, which confers erythromycin resistance (149), has been applied as a selectable marker.

Restriction-modification systems are considered to be transformation barriers (81, 95, 131). Two linear plasmids, lp25 and lp56, are correlated with low transformation efficiency, and many transformants have lost lp25 (95). These two plasmids carry genes bbe02 and bbq67, respectively, encoding restriction-modification enzymes that methylate DNA (131). CpG methylation of plasmid DNA in vitro increases the efficiency of transformation into B. burgdorferi carrying lp56, suggesting that BBQ67 methylates CpG (38). A major reason that low-passage infectious strains are difficult to transform is that plasmid lp25 carries not only bbe02, which is selected against during transformation, but also pncA, a gene essential for infectivity (125), so strains that are both readily transformable and highly infectious are not common.

Bacteriophage and Transduction

Casjens and colleagues have suggested that the genetic diversity found on plasmids may have arisen at least in part because of HGT (30, 32). One potential mechanism for HGT between B. burgdorferi cells is via a transducing bacteriophage (50, 51, 176). At least four different tailed bacteriophage-like particles have been observed in supernatants of B. burgdorferi cultures (11, 50, 52, 70, 115, 150). Of these, the best characterized is ϕBB-1 (Figure 5), which packages members of the ubiquitous cp32 family (52). Every B. burgdorferi strain examined to date includes multiple paralogous versions of cp32 (30–32, 157). The cp32s from all examined strains are largely homologous, with three regions of variability that appear independently assorted among the plasmids: (a) a region containing the replication and partitioning genes, including the unique PFam32 genes that determine compatibility with other plasmids; (b) a region in which the mlp, rev, and bdr genes can be found; and (c) a region in which the ospE/ospF/elp (also known as erp) and other alternative genes are located (30, 32, 49). In addition to putative phage assembly genes and plasmid maintenance genes, genes that modify the borrelial host (lysogenic conversion) are also encoded on the cp32s. Such genes include those that encode surface lipoproteins capable of binding mammalian host proteins, including fibronectin, plasminogen, laminin, and factor H complement regulatory factor binding protein (2, 16–18, 87, 111). Presumably, collecting cp32s and the variable genes they encode assists B. burgdorferi in surviving within a variety of host species (72, 159).

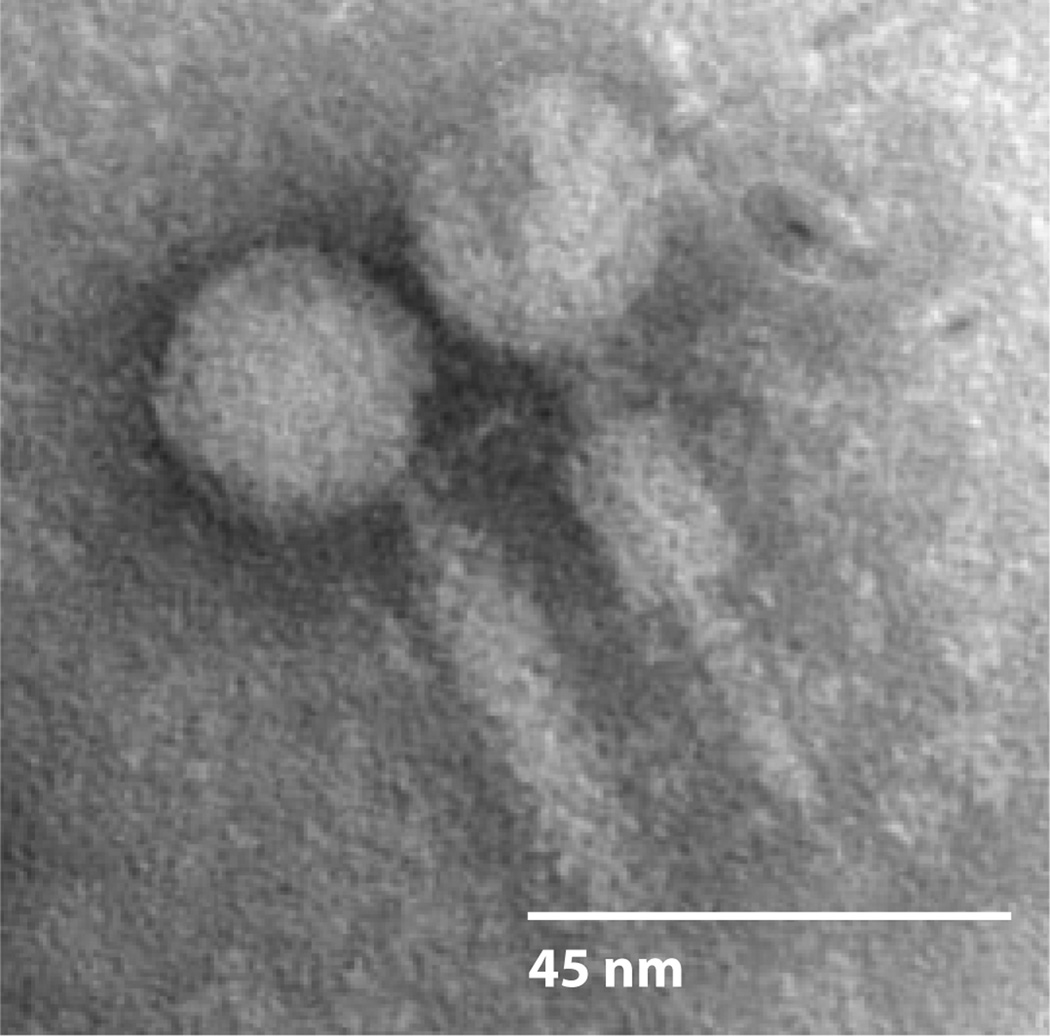

Figure 5.

Bacteriophage ϕBB-1 of Borrelia burgdorferi. Virions were recovered from the supernatant of a culture that had been treated with 1-methyl-3-nitrosonitroguanidine. The phage particles were negatively stained with phosphotungstic acid and observed by transmission electron microscopy. Reproduced with permission from Eggers et al. (51).

Eggers et al. (51) demonstrated that ϕBB-1 is capable of transducing a cp32 between B. burgdorferi cells both of the same strain and of different strains in vitro. Interestingly, phage from one strain more efficiently transduced DNA into cells of the same strain compared with cells of a different strain, which may be related to the restriction-modification systems described above. The overall effect that a restriction-modification system may have on ϕBB-1 as an agent of HGT of DNA has yet to be investigated. Indeed, the role of ϕBB-1 in moving DNA within or between strains is as yet undefined, although presumably transduction occurs in the tick vector, where the spirochete is at a relatively high density compared with the infection in a vertebrate. Stevenson & Miller have reported that B. burgdorferi strain Sh2-82, which seems to have diverged only recently from strain 297, has an extra cp32 that is apparently identical to the strain B31 cp32-8, suggesting the HGT of an entire cp32 between strains (160).

Although transduction of cp32s via ϕBB-1 may be the best-characterized mechanism for HGT thus far elucidated, it may not be the sole means. Several other plasmids contain cp32-derived sequences found within various B. burgdorferi strains, including lp56, lp54, and lp28-2, which were first characterized in strain B31, and two different cp18 plasmids from strains N40 and 297 (28, 30, 158). The cp32-like sequences on cp18, lp54, and lp56 are altered in ways that likely preclude their ability to encode productive prophages; however, lp28-2, which is only distantly related to the cp32s, encodes a number of proteins with weak homology to known phage genes and could be a prophage. Although lp28-2 has not yet been observed packaged in phage heads recovered from culture supernatants, a number of different phage particles other than ϕBB-1 have been observed in association with B. burgdorferi (11, 50, 52, 70, 115, 150), and the genetic content of most of these has yet to be defined. One other potential phage-like mechanism for the transfer of smaller fragments of DNA is gene transfer agents (GTAs), such as those described for Bacillus subtilis (PBSX), Rhodobacter capsulatus, and the spirochete Brachyspira hyodysenteriae (VSH-1) (75, 93, 119, 174). These agents are phage particles that package genomic DNA of their bacterial hosts rather than a viral genome; this genetic material can then be introduced into new hosts (93, 155, 156). In at least one instance, a phage-like particle that packaged heterogenous regions of the borrelial genome rather than a distinct viral genome was observed in a lysed culture of strain CA-11.2A (50). Although transduction has never been demonstrated in B. burgdorferi using this rarely seen phage-like particle, the existence of a GTA in the Lyme disease spirochete could explain the observation that HGT throughout the B. burgdorferi genome involves primarily small regions of DNA, such as would be transduced by such an agent (69).

Antigenic Variation and Recombination

B. burgdorferi must evade the adaptive immune response to persist in the vertebrate host (130). Scrambling the exposed antigenic epitopes of a major surface protein during host infection is a strategy utilized by many other persistent pathogenic bacteria, including Campylobacter jejuni, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Treponema pallidum, and Borrelia hermsii. However, the molecular mechanisms employed by B. burgdorferi to generate antigenic diversity are unusual.

Norris and colleagues (177), in a remarkable study published before the B. burgdorferi genome sequence was released (57), discovered the vls (variable major protein-like sequence) system. This antigenic variation system creates highly diverse epitopes of the outer membrane VlsE lipoprotein during mammalian infection. The vls system first described in strain B31 is located on lp28-1 and consists of the expression locus vlsE and a contiguous string of ~15 silent cassettes directly upstream of the expression locus that are highly homologous to the central 570 bp of vlsE. The central region of vlsE and each silent cassette are flanked by identical 17-bp direct repeats that likely facilitate gene conversion at the vlsE locus by the silent cassettes. Gene conversion, i.e., nonreciprocal homologous recombination, shuffles the DNA sequence at the vlsE expression locus while the sequence of the silent cassettes remains constant (178). Once activated during vertebrate infection, by as yet unknown signals, gene conversion at the vlsE locus alters the amino acid sequence of the surface exposed regions, thus conferring an adaptive advantage to these recombinant B. burgdorferi compared with the parental clone that retains the original vlsE sequence and antigenic profile.

vlsE recombination has been observed only in the mouse and rabbit models of infection; the recombination system does not seem to operate in culture or in the tick vector (55, 76, 117, 177). Antigenic variation begins four days after mouse infection, which results in the parental vlsE sequence disappearing from the population by 28 days postinfection (41, 179). In this manner, incredible VlsE antigenic diversity can be achieved (41). The variation rate is faster in immunocompetent mice compared with immunodeficient mice, which suggests that the VlsE sequence is a target for selection by the adaptive immune response. Furthermore, the mouse adaptive immune response recognizes VlsE as an antigen, and antibodies generated against the parental VlsE show reduced binding to the altered VlsE from B. burgdorferi isolated following mouse infection (110, 177). In strains that have lost lp28-1 or have had the vls locus deleted, infection of immunocompetent mice is not abolished but attenuated, lasting only three weeks and restricted mainly to the joints (7, 90, 126, 177). Taken together, these data illustrate that vlsE recombination is essential for persistent mammalian infection and maintenance of the enzootic cycle.

The mechanism of vlsE recombination has not yet been fully elucidated. B. burgdorferi lacks many DNA repair genes implicated in antigenic variation in other bacteria, and the DNA repair and recombination genes bbg32, mag, mfd, mutL, mutS, nth, priQ, nucA, recA, recG, recJ, rep, sbcC, and sbcD are not required (45, 98). RuvA and RuvB, which catalyze Holliday junction migration, are the only gene products that have been shown to be required for efficient vlsE conversion (45, 97).Mutations in either of these genes dramatically reduce vlsE recombination and, correspondingly, infectivity in immunocompetent mice. The RuvABC Holliday junction branch migrase in Escherichia coli and other bacteria facilitates formation of heteroduplex DNA during homologous recombination and DNA repair (170). One can imagine that this enzyme complex could play a key role in bringing together the homologous regions of the silent cassettes and vlsE during gene conversion in B. burgdorferi, but the signals for activation and the details of the mechanism remain elusive.

While exhaustively sequencing vlsE gene conversion products in B. burgdorferi clones isolated from mice, Coutte et al. (41) observed what they term intermittent recombination events in which the vlsE sequences were mosaics of the parental and silent cassettes; this suggested that the crossover unexpectedly skipped back and forth. Knight et al. (82) also noticed this hop and skip recombination when introducing site-directed mutations into the gyrA gene to disrupt gac, which encodes a novel DNA-binding protein (83). Three sets of gac mutations (the Shine-Dalgarno sequence, the start methionine codon, and the second methionine codon) were synthesized on a transformation substrate linked to an upstream coumarin-resistant gyrB allele. One transformant had the upstream gyrB mutations and the downstream methionine mutations but lacked the Shine-Dalgarno mutations in between. A similar finding was made during fusion of an inducible promoter to ospC (63) when a heterologous ospC allele was inadvertently used, resulting in a variegated sequence (M.A. Gilbert & D.S. Samuels, unpublished data). Therefore, B. burgdorferi appears to have an unusual mechanism for recombination that may generate additional sequence diversity.

POPULATION GENETICS

Current and historical interactions with the external environment and with different species have left decipherable population genetics signatures on the genomes of living organisms. These signatures can be interpreted through analyses of the patterns of genetic and genomic variation within and among species. Recent evolutionary genetics studies of B. burgdorferi combine diverse scientific fields to infer the mutational processes, random drift, and population size as well as the selective pressures that have resulted in the genomic structure and the patterns of genetic variation within populations.

Recombination and Linkage Disequilibrium

The evolution of sexual reproduction, which is the exchange of genetic material, has been extensively explored in plants and animals because of both the potential selective benefits and the costs of the process (67, 86, 105). Interest in HGT among asexual prokaryotes has recently surged because of the rapid evolution of bacterial pathogens, which can be fueled by HGT (59, 94, 118). For example, the transfer of antibiotic resistance alleles among bacteria in human institutions, such as hospitals, has resulted in numerous multidrug-resistant human pathogens (5). Curiously, several pathogenic bacteria, including B. burgdorferi, appear to experience limited HGT (25, 47, 107). The relationship between HGT and the rate of adaptation by natural selection is described below, along with the empirical evidence of the rate of HGT in B. burgdorferi and its effect on the observed and expected evolutionary rates of the species complex.

Genetic exchange between lineages can dramatically affect the rate of evolution (39, 133, 167). Classical theory indicates that HGT allows for the selective removal of deleterious mutations from populations, thus preventing their accumulation (also calledMuller’s ratchet) (36). In addition, the Fisher-Muller model posits that HGT brings beneficial mutations together into a single genome, which eliminates clonal interference and accelerates adaptation (167). HGT can also increase the realized strength of natural selection on new mutations so that the frequency of advantageous mutations increases and that of deleterious mutations decreases (133). Theory predicts that HGT increases the realized strength of selection because it prevents mutations from being trapped in their original genetic background and thereby reduces the dilution of direct selection by background selection (35, 132). HGT reduces the extent to which natural selection on new mutations is diluted by stochastic noise generated by collateral selection on genetic backgrounds. Mutations move between genetic backgrounds via HGT in each generation such that a favored mutation can be fixed and a harmful mutation can be purged in any genetic background. Therefore, HGT works equally well in the context of either the accumulation of beneficial mutations or the removal of deleterious mutations because both are a consequence of the same phenomenon: reduced interference between direct versus background selection (35, 132). Consequently, HGT can have a profound effect on the rate of adaptation in natural populations.

HGT is often investigated by assessing the degree to which genes are genetically linked across a genome (linkage disequilibrium). The rate and extent of HGT are negatively correlated with the degree of linkage disequilibrium observed between genes (109). In a purely clonal species, alleles at one locus are always observed in the same genomes with specific alleles at other loci as a result of common descent, whereas HGT disrupts these associations (106). Early analyses of genetic linkage disequilibrium suggested that B. burgdorferi sensu lato was one of the most clonal groups of bacteria (108). This conclusion has been consistently supported by multilocus studies (47). For example, no recombination was found between four genes [p66, intergenic spacer (IGS), ospA, and ospC] in 61 B. burgdorferi sensu stricto isolates from southern Connecticut and between IGS and ospC in 73 B. afzelii isolates from southern Sweden (25).However, the same ospC allele group can be found in different backgrounds in different geographical regions, implying HGT (12, 24). Interestingly, despite a genome that is extensively fragmented into many plasmids (30, 32, 57), some of which are expected to be easily transferred across lineages (30, 50, 52), alleles are almost always found in linkage disequilibrium with other loci, even when the loci are on different plasmids (6, 24, 25, 47, 109). Until recently, evidence of HGT events was limited to short DNA fragments in genes that were expected to be under strong selection for diversity, such as the ospC locus, implying that HGT would be apparent only when transferred fragments were favored by natural selection (78, 99, 169). The limited HGT in B. burgdorferi suggests that lineages are likely to carry extensive deleterious mutations, although this prediction is not apparent in recent genomic analyses (69, 129).

Strong linkage disequilibrium among genetic loci can result from several evolutionary and ecological forces, such as a lack of recombination machinery or limited opportunity for gene exchange (47), in addition to small population size (genetic drift). Genetically diverse strains of B. burgdorferi are found within the same tick vector or same vertebrate host, suggesting an opportunity for HGT (21, 74, 128), and recombination occurs within genomic lineages of B. burgdorferi (30, 32, 51, 160, 178), which suggests that B. burgdorferi has the recombination system needed for genetic exchange. Thus, the reasons for high levels of genetic linkage among alleles remained mysterious until recently (69). Furthermore, these data had indicated a severe weakening of the strength of selection to purge deleterious mutations and favor beneficial mutations, both of which are inconsistent with observations from natural populations and genome sequence data, suggesting that strong selection occurs in natural populations (21, 23, 129).

Recent studies of whole genome sequences have found that HGT is much more common than originally thought (12, 69, 129). Gene trees are often inconsistent with the ribosomal spacer region sequence on the chromosome, which is generally used to construct strain phylogenies, strongly suggesting HGT. Unexpectedly, the phylogeny built from sequences of ospC, a gene known to undergo extensive HGT, was consistent with the phylogeny from the ribosomal spacer region sequence (6, 129). Collectively, 28 examples of homoplasy could be detected in the other gene trees analyzed (6). Interestingly, the rate of HGT of plasmidborne loci is approximately 100-fold higher than in chromosomal loci (6, 129). Although B. burgdorferi is not strictly clonal, HGT events appear rare in general and are nearly nonexistent on the chromosome. The low rate of HGT in Borrelia implies that most or all of the genes showing allelic diversity are under balancing selection in which recombinants have a selective advantage or are genetically linked to such a system under balancing selection.

The DNA fragments transferred in the infrequent HGT events are generally small. Recent analyses of 23 genomes suggest that transferred fragments are generally less than 2,000 base pairs (12, 69). Currently, no data support the transfer of whole plasmids, except the cp32 prophage (51, 160), despite a genome extensively fragmented into many smaller, more easily transferable units. Importantly, each genome analyzed showed evidence of very few HGT events. Rare HGT events that incorporate small fragments would weaken linkage disequilibrium among local sites, as small fragment exchange would affect linkage combinations only on this scale. However, linkage combinations among distant sites would not be affected, resulting in strong linkage disequilibrium at distantly located sites. Analysis of more than 13,500 single-nucleotide polymorphisms from the 23 B. burgdorferi genomes showed this counterintuitive pattern of limited linkage disequilibrium among local sites but high genome-wide linkage disequilibrium (69). The small size of fragments transferred and the relative rarity of HGT events may explain why the early studies found near-perfect clonality.

Although HGT is relatively rare, the majority of the sequence diversity in B. burgdorferi results from reassortment of preexisting sequence polymorphisms through localized HGT, and only one quarter results from de novo point mutations (69, 129). Importantly, HGT events occur both within and among B. burgdorferi sensu lato genospecies (47, 69, 129). HGT of selectively advantageous DNA segments, such as all or part of the ospC locus, can quickly increase in frequency within populations. In fact, the data strongly suggest HGT of all or part of ospC among lineages within B. burgdorferi sensu stricto and among B. burgdorferi sensu lato genospecies (12, 69). Thus, despite limited HGT in B. burgdorferi, there is compelling evidence that HGT is pervasive enough to allow strong natural selection and adaptation in B. burgdorferi populations.

A glaring exception to the modest HGT and transfer of small-sized DNA fragments experienced by most B. burgdorferi loci are the cp32s (51, 160). cp32s are transferred among B. burgdorferi lineages at a high rate, presumably via transduction (51). Despite the strong linkage disequilibrium observed among most loci, alleles at the ospE/ospF/elp (erp) locus are in near-perfect linkage equilibrium in B. burgdorferi sensu stricto isolates cultured from human patients (48a). The overwhelming impression is that the cp32s transfer between strains much faster than do other loci, and consequently, cp32 genetic variation is not expected to be in linkage disequilibrium with the remainder of the genome.

Genetic Variation and Natural Selection

The patterns of genetic variation in natural populations of B. burgdorferi suggest that the majority of loci are under stabilizing selection or have experienced a recent population bottleneck (102, 127, 166). Both stabilizing selection and low effective population sizes result in very low genetic diversity, as seen in most B. burgdorferi loci, especially those located on the chromosome (24, 102, 166). Interestingly, loci with appreciable variation show patterns of diversity reminiscent of balancing selection (68, 69, 129). In other words, the allelic frequency distribution is even more than that expected by chance alone. Genome-wide linkage to a single locus under balancing selection, ospC, is likely responsible for maintaining genetic variation at linked loci (69).

ospC is probably the most genetically diverse locus in all B. burgdorferi genospecies. In the northeastern United States, 16 OspC major groups are defined as alleles that are less than 2%different in protein sequence and more than 8% different from alleles in other major groups (24, 169).OspC major groups differ by an average of 14%, with the lower end of this variation (8% to 11%) representing variation between three groups that share a segment homogenized by recombination (99, 169). Allele frequencies higher than expected under a neutral drift hypothesis imply that balancing selection preserves genetic variation (21, 128). Functionally, OspC major groups have different serotypes (64). A strong adaptive immune response to OspC occurs early in infection (173). Once infected, a vertebrate cannot be infected by another strain expressing an ospC allele from the same major group but can be infected by strains with alleles from other major groups (64). The surface-exposed regions of OspC display the highest amino acid variability, further supporting the serotypic difference hypothesis (53, 88).

The mechanism by which ospC diversity is selectively maintained is still debated. Two primary models of balancing selection apply to B. burgdorferi populations: negative frequency-dependent selection (NFDS) and multiple niche polymorphisms (MNPs), each of which can account for some, but not all, of the theoretical and empirical data. NFDS occurs when rare genotypes have a selective advantage over common genotypes (66). The strong immune response generated against OspC could give rare serotypes a selective advantage and maintain the ospC polymorphism (64, 69) because immune memory to specific OspC serotypes protects vertebrates from future infections with the same serotype but does not prevent infection with alternate OspC serotypes (64, 124). In nature, the number of susceptible hosts would be greater for rare OspC serotypes, and they should increase in frequency, suggesting that NFDS is a plausible hypothesis to explain the ospC diversity in natural populations. The NFDS hypothesis is also favored by a recent theoretical analysis showing that the observed diversity at OspC and at other genomic loci could be readily simulated using a simple NFDS model with very few parameters (69).

Alternatively, MNP may be the driving force maintaining genetic diversity at the ospC locus. MNP preserves diversity within populations when the environment is heterogeneous and no one serotype has the highest fitness in all environments. The environments, which are the different species of vertebrate hosts that B. burgdorferi encounter, are heterogeneous with respect to OspC serotype fitness. Serotype fitness differs dramatically among the examined vertebrate species from natural northeastern forests (21–23, 68). In fact, the majority of serotypes had a fitness of nearly zero in most vertebrate species. That is, only a subset of serotypes can infect and be acquired by ticks from each vertebrate species, and the subsets differ among species (21, 68).Thus, host species selectivity could create the conditions necessary to maintain ospC diversity by MNP.

MNP through host selectivity is further supported by analyses of ospC serotypes from human infections. Similar to natural host species, only five OspC serotypes (A, B, K, I, and N) commonly infect humans in the Northeast (48, 152, 175). Similar patterns are found in other Lyme disease hotspots and in other B. burgdorferi genospecies (9, 24, 91). The OspC serotypes that commonly infect humans are regularly isolated from skin lesions, blood, and the central nervous system of patients, whereas all other serotypes are less common in skin lesions, rarely disseminate to blood, and are absent from the central nervous system (1, 48, 91, 152). OspC serotypes that are commonly found in human infections also appear to be more infectious when scaled by the probability of exposure to that OspC serotype from a tick bite (48). Human selectivity, like many biological phenomena, is a bimodally distributed continuum.

Although much of the data support both the NFDS and the MNP hypotheses, several empirical and theoretical observations do not conform to each model. For example, NFDS cannot account for the apparent host species associations seen in natural systems. All hosts, regardless of species, should be infected by each of the OspC serotypes if NFDS maintains ospC diversity as implied by theory (66).The preponderance of data revealing that serotypes have differential evolutionary fitness in each host species demonstrates that NFDS cannot be the only selective force maintaining diversity at the ospC locus. Furthermore, NFDS should result in serotypes at approximately the same frequency, and the most frequent serotypes should change through time. However, serotypes in natural populations vary in frequency by 20-fold (169), and the dominant types are consistent through time in each location, again suggesting that NFDS by immune exclusion is not the major cause of balancing selection.

Theoretical and empirical observations are more concordant with the MNP hypothesis, although several observations remain unresolved. First, models of MNP are likely to require more parameters than NFDS (69), indicating they are a less parsimonious explanation, although this does not rule out MNP as the force maintaining ospC diversity. Second, the same OspC types are found in many geographic areas despite different host species compositions (12, 24, 74, 102, 123). However, even in single geographic areas, the majority of OspC serotypes infect multiple evolutionarily divergent vertebrate species, so they can likely infect species in multiple geographic regions (1, 21, 22, 68). Finally, and most importantly, there appear to be many more OspC serotypes than there are host species. A predominance of data demonstrates that most B. burgdorferi sensu stricto use only five vertebrate species as a host in the northeastern United States, whereas at least 16 OspC types are maintained (20, 23, 128, 169). No model of MNP can selectively maintain more alleles than there are ecologically distinct niches. However, there are many vertebrate species that have yet to be investigated that host at least 20% of the B. burgdorferi sensu stricto population and collectively could account for the remaining niche space (23). Furthermore, there is growing evidence of tissue specificity within hosts for different OspC serotypes (19), suggesting that host tissues within each species may further divide the niche space and thus account for the remaining niches. Although MNP may not be the only force maintaining ospC diversity, the current empirical evidence is more consistent with the MNP rather than the NFDS model.

SUMMARY POINTS.

B. burgdorferi, a spirochete, is an extracellular pathogen whose lifestyle is restricted to cycling between Ixodes ticks and vertebrate hosts. Its unique genome is highly segmented and includes linear DNA molecules.

The taxonomic diversity of the Lyme disease Borrelia, of which only three genospecies cause human disease, resulted from an explosive species radiation near the origin of the species group.

Almost all mutants that have been selected for are resistant to antibiotics that target a topoisomerase or the ribosome. Systems to genetically manipulate B. burgdorferi have been developed based on electrotransformation and antibiotic-resistant selectable markers.

B. burgdorferi evades the adaptive immune response in the mammalian host by antigenic variation of a surface lipoprotein, VlsE, using an unusual system of gene conversion.

One likely mechanism of HGT in B. burgdorferi is via transduction. All B. burgdorferi isolates carry a family of prophages as 32-kb circular plasmids. The bacteriophage that packages these cp32s, designated ϕBB-1, can shuttle them between cells in vitro and potentially in vivo.

The modest HGT among lineages is sufficient to allow strong natural selection and adaptation in B. burgdorferi populations.

The polymorphism at the ospC locus is maintained by a combination of MNP and NFDS.

FUTURE ISSUES.

Why is the B. burgdorferi genome so highly segmented?

What are the mammalian signals that induce vlsE recombination, and what are the molecular details of the mechanism?

What is the role of transduction by cp32 prophage in HGT throughout the enzootic cycle?

What cp32 genes encode phage structural elements? Are other plasmids, such as lp28-2, capable of being packaged into virions and transduced between cells?

What is the evolutionary history of B. burgdorferi? Multilocus studies have resulted in a much more robust understanding of the evolutionary, demographic, and migratory history of B. burgdorferi than the previous single-locus analyses. However, there is still very limited information at each locus, suggesting that genomic-level studies will dramatically increase analytical resolution.

To what degree do MNP and NFDS maintain polymorphisms? This would begin primarily as a modeling exercise but should identify areas that can be empirically investigated.

Are other polymorphic loci in linkage disequilibrium with OspC owing to selection (association of these alleles is selectively advantageous) or because of lack of HGT?

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Sherwood Casjens, Dan Dykhuizen, Meghan Lybecker, Rich Marconi, Dara Newman, Justin Radolf, Patti Rosa, and Kit Tilly for valuable discussions, Mike Minnick for the use of his fluorescent microscope, and Claude Garon for the electron microscopy of electroporated spirochetes. Our research on the genetics of Borrelia burgdorferi is supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (AI076342 to D.B., AI088131 to D.D. and D.S.S., and AI051486 to D.S.S.) and by a Faculty Research Award from the School of Health Sciences at Quinnipiac University (C.H.E.).

Glossary

- Enzootic

maintenance of a microbe, without external inputs, in a geographically localized animal population or community

- Transovarial transmission

transmission from the female tick through the eggs to the larvae of the next generation

- Hemocoel

tick body cavity containing the hemolymph that delivers oxygen to the organs

- Circular plasmid (cp) and linear plasmid (lp)

components of the segmented genome that are smaller than the chromosome; the adjacent number is the approximate size in kilobase pairs in strain B31, e.g., cp32 is a 32-kb circular plasmid

- Transduction

movement of genetic material from one bacterium to another by a bacteriophage

- Horizontal (or lateral) gene transfer (HGT)

the movement of genetic information between cells of the same generation

- Electroporation

an electrical pulse used to transiently create holes in the cell membrane to introduce DNA

- Restriction-modification system

used by bacteria to protect themselves from foreign DNA, such as that introduced by a bacteriophage

- Gene transfer agent (GTA)

a bacteriophage-like particle that packages random pieces of host genomic DNA and can transfer this genetic material to other bacterial cells

- Linkage disequilibrium

the occurrence of some alleles together more often than would be expected by chance

- Intergenic spacer (IGS)

located between the 16S and 23S ribosomal DNA and used as a neutral marker in bacterial population genetics

- Genetic drift

the change in the frequency of alleles in a population due to random processes

- Homoplasy

similarity in DNA sequence or morphological characteristics due to convergent evolution to identical character states rather than due to common ancestry

- Balancing selection

a type of natural selection in which genetic diversity is actively maintained in the gene pool of a population

- Stabilizing selection

a type of natural selection in which genetic diversity is removed from the gene pool of a population

- Negative frequency-dependent selection (NFDS)

a type of balancing selection that occurs when the fitness of a phenotype is inversely correlated with its frequency in the population

- Multiple niche polymorphism (MNP)

a type of balancing selection that occurs in heterogeneous environments where no one phenotype has the greatest fitness in all environments

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

The authors are not aware of any affiliations, memberships, funding, or financial holdings that might be perceived as affecting the objectivity of this review.

Contributor Information

Dustin Brisson, Email: dbrisson@sas.upenn.edu.

Dan Drecktrah, Email: dan.drecktrah@mso.umt.edu.

Christian H. Eggers, Email: christian.eggers@quinnipiac.edu.

D. Scott Samuels, Email: scott.samuels@umontana.edu.

LITERATURE CITED

- 1.Alghaferi MY, Anderson JM, Park J, Auwaerter PG, Aucott JN, et al. Borrelia burgdorferi ospC heterogeneity among human and murine isolates from a defined region of northern Maryland and southern Pennsylvania: lack of correlation with invasive and noninvasive genotypes. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2005;43:1879–1884. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.4.1879-1884.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alitalo A, Meri T, Lankinen H, Seppälä I, Lahdenne P, et al. Complement inhibitor factor H binding to Lyme disease spirochetes is mediated by inducible expression of multiple plasmid-encoded outer surface protein E paralogs. J. Immunol. 2002;169:3847–3853. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.7.3847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alverson J, Bundle SF, Sohaskey CD, Lybecker MC, Samuels DS. Transcriptional regulation of the ospAB and ospC promoters from Borrelia burgdorferi. Mol. Microbiol. 2003;48:1665–1677. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03537.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alverson J, Samuels DS. groEL expression in gyrB mutants of Borrelia burgdorferi. J. Bacteriol. 2002;184:6069–6072. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.21.6069-6072.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Andam CP, Fournier GP, Gogarten JP. Multilevel populations and the evolution of antibiotic resistance through horizontal gene transfer. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2011;35:756–767. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2011.00274.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Attie O, Bruno JF, Xu Y, Qiu D, Luft BJ, Qiu W-G. Co-evolution of the outer surface protein C gene (ospC) and intraspecific lineages of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu stricto in the northeastern United States. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2007;7:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2006.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bankhead T, Chaconas G. The role of VlsE antigenic variation in the Lyme disease spirochete: persistence through a mechanism that differs from other pathogens. Mol. Microbiol. 2007;65:1547–1558. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05895.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baranton G, Postic D, Saint Girons I, Boerlin P, Piffaretti J-C, et al. Delineation of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu stricto, Borrelia garinii sp. nov., and group VS461 associated with Lyme borreliosis. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 1992;42:378–383. doi: 10.1099/00207713-42-3-378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baranton G, Seinost G, Theodore G, Postic D, Dykhuizen D. Distinct levels of genetic diversity of Borrelia burgdorferi are associated with different aspects of pathogenicity. Res. Microbiol. 2001;152:149–156. doi: 10.1016/s0923-2508(01)01186-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barbour AG, Garon CF. Linear plasmids of the bacterium Borrelia burgdorferi have covalently closed ends. Science. 1987;237:409–411. doi: 10.1126/science.3603026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barbour AG, Hayes SF. Biology of Borrelia species. Microbiol. Rev. 1986;50:381–400. doi: 10.1128/mr.50.4.381-400.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barbour AG, Travinsky B. Evolution and distribution of the ospC gene, a transferable serotype determinant of Borrelia burgdorferi. MBio. 2010;1:e00153–e001510. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00153-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Blevins JS, Revel AT, Smith AH, Bachlani GN, Norgard MV. Adaptation of a luciferase gene reporter and lac expression system to Borrelia burgdorferi. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2007;73:1501–1513. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02454-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bono JL, Elias AF, Kupko JJ, 3rd, Stevenson B, Tilly K, Rosa P. Efficient targeted mutagenesis in Borrelia burgdorferi. J. Bacteriol. 2000;182:2445–2452. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.9.2445-2452.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Botkin DJ, Abbott AN, Stewart PE, Rosa PA, Kawabata H, et al. Identification of potential virulence determinants by Himar1 transposition of infectious Borrelia burgdorferi B31. Infect. Immun. 2006;74:6690–6699. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00993-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brissette CA, Bykowski T, Cooley AE, Bowman A, Stevenson B. Borrelia burgdorferi RevA antigen binds host fibronectin. Infect. Immun. 2009;77:2802–2812. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00227-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brissette CA, Haupt K, Barthel D, Cooley AE, Bowman A, et al. Borrelia burgdorferi infection-associated surface proteins ErpP, ErpA, and ErpC bind human plasminogen. Infect. Immun. 2009;77:300–306. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01133-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brissette CA, Verma A, Bowman A, Cooley AE, Stevenson B. The Borrelia burgdorferi outer-surface protein ErpX binds mammalian laminin. Microbiology. 2009;155:863–872. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.024604-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brisson D, Baxamusa N, Schwartz I, Wormser GP. Biodiversity of Borrelia burgdorferi strains in tissues of Lyme disease patients. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e22926. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0022926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brisson D, Brinkley C, Humphrey PT, Kemps BD, Ostfeld RS. It takes a community to raise the prevalence of a zoonotic pathogen. Interdiscip. Perspect. Infect. Dis. 2011;2011:741406. doi: 10.1155/2011/741406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brisson D, Dykhuizen DE. ospC diversity in Borrelia burgdorferi: Different hosts are different niches. Genetics. 2004;168:713–722. doi: 10.1534/genetics.104.028738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brisson D, Dykhuizen DE. A modest model explains the distribution and abundance of Borrelia burgdorferi strains. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2006;74:615–622. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brisson D, Dykhuizen DE, Ostfeld RS. Conspicuous impacts of inconspicuous hosts on the Lyme disease epidemic. Proc. R. Soc. B. 2008;275:227–235. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2007.1208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brisson D, Vandermause MF, Meece JK, Reed KD, Dykhuizen DE. Evolution of northeastern and midwestern Borrelia burgdorferi United States. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2010;16:911–917. doi: 10.3201/eid1606.090329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bunikis J, Garpmo U, Tsao J, Berglund J, Fish D, Barbour AG. Sequence typing reveals extensive strain diversity of the Lyme borreliosis agents Borrelia burgdorferi in North America and Borrelia afzelii in Europe. Microbiology. 2004;150:1741–1755. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.26944-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Burgdorfer W, Barbour AG, Hayes SF, Benach JL, Grunwaldt E, Davis JP. Lyme disease: a tick-borne spirochetosis? Science. 1982;216:1317–1319. doi: 10.1126/science.7043737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Busch U, Hizo-Teufel C, Boehmer R, Fingerle V, Nitschko H, et al. Three species of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato (B. burgdorferi sensu stricto, B afzelii and B. garinii) identified from cerebrospinal fluid isolates by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis and PCR. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1996;34:1072–1078. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.5.1072-1078.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Caimano MJ, Yang X, Popova TG, Clawson ML, Akins DR, et al. Molecular and evolutionary characterization of the cp32/cp18 family of supercoiled plasmids in B. burgdorferi 297. Infect. Immun. 2000;68:1574–1586. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.3.1574-1586.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Canica MM, Nato F, du Merle L, Mazie JC, Baranton G, Postic D. Monoclonal antibodies for identification of Borrelia afzelii sp. nov. associated with late cutaneous manifestations of Lyme borreliosis. Scand. J. Infect. Dis. 1993;25:441–448. doi: 10.3109/00365549309008525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Casjens S, Palmer N, van Vugt R, Huang WM, Stevenson B, et al. A bacterial genome in flux: the twelve linear and nine circular extrachromosomal DNAs in an infectious isolate of the Lyme disease spirochete Borrelia burgdorferi. Mol. Microbiol. 2000;35:490–516. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01698.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Casjens S, van Vugt R, Tilly K, Rosa PA, Stevenson B. Homology throughout the multiple 32- kilobase circular plasmids present in Lyme disease spirochetes. J. Bacteriol. 1997;179:217–227. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.1.217-227.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Casjens SR, Mongodin EF, Qiu W-G, Luft BJ, Schutzer SE, et al. Genome stability of Lyme disease spirochetes: comparative genomics of Borrelia burgdorferi plasmids. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e33280. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0033280. Compares four B. burgdorferi strains demonstrating variability in plasmid composition while retaining relative overall genome stability.

- 33.Chaconas G, Kobryn K. Structure, function, and evolution of linear replicons in Borrelia. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2010;64:185–202. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.112408.134037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Champoux JJ. DNA topoisomerases: structure, function, and mechanism. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2001;70:369–413. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.70.1.369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Charlesworth B. The effect of background selection against deleterious mutations on weakly selected, linked variants. Genet. Res. 1994;63:213–227. doi: 10.1017/s0016672300032365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Charlesworth B, Charlesworth D. The degeneration of Y chromosomes. Philos. Trans. R Soc. Lond. B. 2000;355:1563–1572. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2000.0717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Charon NW, Cockburn A, Li C, Liu J, Miller K, et al. The unique paradigm of spirochete motility and chemotaxis. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2012 doi: 10.1146/annurev-micro-092611-150145. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chen Q, Fischer JR, Benoit VM, Dufour NP, Youderian P, Leong JM. In vitro CpG methylation increases the transformation efficiency of Borrelia burgdorferi strains harboring the endogenous linear plasmid lp56. J. Bacteriol. 2008;190:7885–7891. doi: 10.1128/JB.00324-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Colegrave N. Sex releases the speed limit on evolution. Nature. 2002;420:664–666. doi: 10.1038/nature01191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Corbett KD, Berger JM. Structure, molecular mechanisms, and evolutionary relationships in DNA topoisomerases. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 2004;33:95–118. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.33.110502.140357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Coutte L, Botkin DJ, Gao L, Norris SJ. Detailed analysis of sequence changes occurring during vlsE antigenic variation in the mouse model of Borrelia burgdorferi infection. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000293. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Criswell D, Tobiason VL, Lodmell JS, Samuels DS. Mutations conferring aminoglycoside and spectinomycin resistance in Borrelia burgdorferi. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2006;50:445–452. doi: 10.1128/AAC.50.2.445-452.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Derdáková M, Lenčáková D. Association of genetic variability within the Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato with the ecology, epidemiology of Lyme borreliosis in Europe. Ann. Agric. Environ. Med. 2005;12:165–172. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Drecktrah D, Douglas JM, Samuels DS. Use of rpsL as a counterselectable marker in Borrelia burgdorferi. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2010;76:985–987. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02172-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dresser AR, Hardy PO, Chaconas G. Investigation of the genes involved in antigenic switching at the vlsE locus in Borrelia burgdorferi : an essential role for the RuvAB branch migrase. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000680. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Drlica K, Zhao X. DNA gyrase, topoisomerase IV, and the 4-quinolones. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 1997;61:377–392. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.61.3.377-392.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dykhuizen DE, Baranton G. The implications of a low rate of horizontal transfer in Borrelia. Trends Microbiol. 2001;9:344–350. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(01)02066-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Dykhuizen DE, Brisson D, Sandigursky S, Wormser GP, Nowakowski J, et al. The propensity of different Borrelia burgdorferi sensu stricto genotypes to cause disseminated infections in humans. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2008;78:806–810. Shows that although many ospC types can infect humans, only five do so regularly.

- 48a. Dykhuizen D, Brisson D. Evolutionary genetics of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato. 2010:221–249. See Ref. 148.

- 49.Eggers CH, Caimano MJ, Clawson ML, Miller WG, Samuels DS, Radolf JD. Identification of loci critical for replication and compatibility of a Borrelia burgdorferi cp32 plasmid and use of a cp32-based shuttle vector for expression of fluorescent reporters in the Lyme disease spirochaete. Mol. Microbiol. 2002;43:281–296. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.02758.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Eggers CH, Casjens S, Hayes SF, Garon CF, Damman CJ, et al. Bacteriophages of spirochetes. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2000;2:365–373. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Eggers CH, Kimmel BJ, Bono JL, Elias A, Rosa P, Samuels DS. Transduction by ϕBB-1, a bacteriophage of Borrelia burgdorferi. J. Bacteriol. 2001;183:4771–4778. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.16.4771-4778.2001. Demonstrates transduction, which is a molecular mechanism of HGT.

- 52.Eggers CH, Samuels DS. Molecular evidence for a new bacteriophage of Borrelia burgdorferi. J. Bacteriol. 1999;181:7308–7313. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.23.7308-7313.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Eicken C, Sharma V, Klabunde T, Owens RT, Pikas DS, et al. Crystal structure of Lyme disease antigen outer surface protein C from Borrelia burgdorferi. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:10010–10015. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M010062200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Elias AF, Bono JL, Kupko JJ, 3rd, Stewart PE, Krum JG, Rosa PA. New antibiotic resistance cassettes suitable for genetic studies in Borrelia burgdorferi. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2003;6:29–40. doi: 10.1159/000073406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Embers ME, Liang FT, Howell JK, Jacobs MB, Purcell JE, et al. Antigenicity and recombination of VlsE, the antigenic variation protein of Borrelia burgdorferi in rabbits, a host putatively resistant to long-term infection with this spirochete. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 2007;50:421–429. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2007.00276.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Frank KL, Bundle SF, Kresge ME, Eggers CH, Samuels DS. aadA confers streptomycin resistance in Borrelia burgdorferi. J. Bacteriol. 2003;185:6723–6727. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.22.6723-6727.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Fraser CM, Casjens S, Huang WM, Sutton GG, Clayton R, et al. Genomic sequence of a Lyme disease spirochete, Borrelia burgdorferi. Nature. 1997;390:580–586. doi: 10.1038/37551. Describes the first complete genome sequence of a B. burgdorferi strain.

- 58.Fukunaga M, Koreki Y. A phylogenetic analysis of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato isolates associated with Lyme disease in Japan by flagellin gene sequence determination. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 1996;46:416–421. doi: 10.1099/00207713-46-2-416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gal-Mor O, Finlay BB. Pathogenicity islands: a molecular toolbox for bacterial virulence. Cell. Microbiol. 2006;8:1707–1719. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2006.00794.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Galbraith KM, Ng AC, Eggers BJ, Kuchel CR, Eggers CH, Samuels DS. parC mutations in fluoroquinolone-resistant Borrelia burgdorferi. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2005;49:4354–4357. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.10.4354-4357.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Garon CF, Dorward DW, Corwin MD. Structural features of Borrelia burgdorferi —the Lyme disease spirochete: silver staining for nucleic acids. Scanning Microsc. Suppl. 1989;3:109–115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Gherardini F, Boylan J, Lawrence K, Skare J. Metabolism and physiology of Borrelia. 2010:103–138. See Ref. 148.

- 63.Gilbert MA, Morton EA, Bundle SF, Samuels DS. Artificial regulation of ospC expression in Borrelia burgdorferi. Mol. Microbiol. 2007;63:1259–1273. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05593.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gilmore RD, Kappel KJ, Dolan MC, Burkot TR, Johnson BJ. Outer surface protein C (OspC), but not P39, is a protective immunogen against a tick-transmitted Borrelia burgdorferi challenge: evidence for a conformational protective epitope in OspC. Infect. Immun. 1996;64:2234–2239. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.6.2234-2239.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Grimm D, Tilly K, Byram R, Stewart PE, Krum JG, et al. Outer-surface protein C of the Lyme disease spirochete: a protein induced in ticks for infection of mammals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:3142–3147. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0306845101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gromko MH. What is frequency-dependent selection? Evolution. 1977;31:438–442. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1977.tb01024.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hamilton WD, Axelrod R, Tanese R. Sexual reproduction as an adaptation to resist parasites (a review) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1990;87:3566–3573. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.9.3566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hanincová K, Kurtenbach K, Diuk-Wasser M, Brei B, Fish D. Epidemic spread of Lyme borreliosis, northeastern United States. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2006;12:604–611. doi: 10.3201/eid1204.051016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Haven J, Vargas LC, Mongodin EF, Xue V, Hernandez Y, et al. Pervasive recombination and sympatric genome diversification driven by frequency-dependent selection in Borrelia burgdorferi the Lyme disease bacterium. Genetics. 2011;189:951–966. doi: 10.1534/genetics.111.130773. Definitively demonstrates evidence of infrequent HGT of small DNA fragments.

- 70.Hayes SF, Burgdorfer W, Barbour AG. Bacteriophage in the Ixodes dammini spirochete, etiological agent of Lyme disease. J. Bacteriol. 1983;154:1436–1439. doi: 10.1128/jb.154.3.1436-1439.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hooper DC. Bacterial topoisomerases, anti-topoisomerases, and anti-topoisomerase resistance. Clin. Infect. Dis. 1998;27(Suppl. 1):S54–S63. doi: 10.1086/514923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hovis KM, Tran E, Sundy CM, Buckles E, McDowell JV, Marconi RT. Selective binding of Borrelia burgdorferi OspE paralogs to factor H and serum proteins from diverse animals: possible expansion of the role of OspE in Lyme disease pathogenesis. Infect. Immun. 2006;74:1967–1972. doi: 10.1128/IAI.74.3.1967-1972.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Huang WM. Bacterial diversity based on type II DNA topoisomerase genes. Annu. Rev. Genet. 1996;30:79–107. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.30.1.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Humphrey PT, Caporale DA, Brisson D. Uncoordinated phylogeography of Borrelia burgdorferi and its tick vector, Ixodes scapularis. Evolution. 2010;64:2653–2663. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2010.01001.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Humphrey SB, Stanton TB, Jenson NS, Zuerner RL. Purification and characterization of VSH-1, a generalized transducing bacteriophage of Serpulina hyodysenteriae. J. Bacteriol. 1997;179:323–329. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.2.323-329.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Indest KJ, Howell JK, Jacobs MB, Scholl-Meeker D, Norris SJ, Philipp MT. Analysis of Borrelia burgdorferi vlsE gene expression and recombination in the tick vector. Infect. Immun. 2001;69:7083–7090. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.11.7083-7090.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Jackson CR, Boylan JA, Frye JG, Gherardini FC. Evidence of a conjugal erythromycin resistance element in the Lyme disease spirochete Borrelia burgdorferi. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents. 2007;30:496–504. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2007.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Jauris-Heipke S, Liegl G, Preac-Mursic V, Rößsler D, Schwab E, et al. Molecular analysis of genes encoding outer surface protein C (OspC) of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato: relationship to ospA genotype and evidence of lateral gene exchange of ospC. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1995;33:1860–1866. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.7.1860-1866.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Johnson RC, Hyde FW, Rumpel CM. Taxonomy of the Lyme disease spirochetes. Yale. J. Biol. Med. 1984;57:529–537. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kawabata H, Masuzawa T, Yanagihara Y. Genomic analysis of Borrelia japonica sp. nov. isolated from Ixodes ovatus in Japan. Microbiol. Immunol. 1993;37:843–848. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1993.tb01714.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kawabata H, Norris SJ, Watanabe H. BBE02 disruption mutants of Borrelia burgdorferi B31 have a highly transformable, infectious phenotype. Infect. Immun. 2004;72:7147–7154. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.12.7147-7154.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Knight SW, Kimmel BJ, Eggers CH, Samuels DS. Disruption of the Borrelia burgdorferi gac gene, encoding the naturally synthesized GyrA C-terminal domain. J. Bacteriol. 2000;182:2048–2051. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.7.2048-2051.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Knight SW, Samuels DS. Natural synthesis of a DNA-binding protein from the C-terminal domain of DNA gyrase A in Borrelia burgdorferi. EMBO J. 1999;18:4875–4881. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.17.4875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kobryn K, Chaconas G. ResT, a telomere resolvase encoded by the Lyme disease spirochete. Mol. Cell. 2002;9:195–201. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00433-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Kobryn K, Chaconas G. Fusion of hairpin telomeres by the B. burgdorferi telomere resolvase ResT: implications for shaping a genome in flux. Mol. Cell. 2005;17:783–791. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.02.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kondrashov AS. Deleterious mutations and the evolution of sexual reproduction. Nature. 1988;336:435–440. doi: 10.1038/336435a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Kraiczy P, Hartmann K, Hellwage J, Skerka C, Kirschfink M, et al. Immunological characterization of the complement regulator factor H-binding CRASP and Erp proteins of Borrelia burgdorferi. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 2004;293(Suppl. 37):152–157. doi: 10.1016/s1433-1128(04)80029-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Kumaran D, Eswaramoorthy S, Luft BJ, Koide S, Dunn JJ, et al. Crystal structure of outer surface protein C (OspC) from the Lyme disease spirochete, Borrelia burgdorferi. EMBO J. 2001;20:971–978. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.5.971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Kurtenbach K, Hanincová K, Tsao JI, Margos G, Fish D, Ogden NH. Fundamental processes in the evolutionary ecology of Lyme borreliosis. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2006;4:660–669. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Labandeira-Rey M, Skare JT. Decreased infectivity in Borrelia burgdorferi strain B31 is associated with loss of linear plasmid 25 or 28-1. Infect. Immun. 2001;69:446–455. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.1.446-455.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Lagal V, Postic D, Ruzic-Sabljic E, Baranton G. Genetic diversity among Borrelia strains determined by single-strand conformation polymorphism analysis of the ospC gene and its association with invasiveness. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2003;41:5059–5065. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.11.5059-5065.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Lane RS, Piesman J, Burgdorfer W. Lyme borreliosis: relation of its causative agent to its vectors and hosts in North America and Europe. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 1991;36:587–609. doi: 10.1146/annurev.en.36.010191.003103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Lang AS, Beatty JT. Genetic analysis of a bacterial genetic exchange element: the gene transfer agent of Rhodobacter capsulatus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:859–864. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.2.859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Lawrence JG. Horizontal and vertical gene transfer: the life history of pathogens. Contrib. Microbiol. 2005;12:255–271. doi: 10.1159/000081699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Lawrenz MB, Kawabata H, Purser JE, Norris SJ. Decreased electroporation efficiency in Borrelia burgdorferi containing linear plasmids lp25 and lp56: impact on transformation of infectious B. burgdorferi. Infect. Immun. 2002;70:4798–4804. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.9.4798-4804.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Le Fleche A, Postic D, Girardet K, Peter O, Baranton G. Characterization of Borrelia lusitaniae sp. nov. by 16S ribosomal DNA sequence analysis. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 1997;47:921–925. doi: 10.1099/00207713-47-4-921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Lin T, Gao L, Edmondson DG, Jacobs MB, Philipp MT, Norris SJ. Central role of the Holliday junction helicase RuvAB in vlsE recombination and infectivity of Borrelia burgdorferi. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000679. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Liveris D, Mulay V, Sandigursky S, Schwartz I. Borrelia burgdorferi vlsE antigenic variation is not mediated by RecA. Infect. Immun. 2008;76:4009–4018. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00027-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Livey I, Gibbs CP, Schuster R, Dorner F. Evidence for lateral transfer and recombination in OspC variation in Lyme disease Borrelia. Mol. Microbiol. 1995;18:257–269. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.mmi_18020257.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Marconi RT, Liveris D, Schwartz I. Identification of novel insertion elements, restriction fragment length polymorphism patterns, and discontinuous 23S rRNA in Lyme disease spirochetes: phylogenetic analyses of rRNA genes and their intergenic spacers in Borrelia japonica sp. nov. and genomic group 21038 (Borrelia andersonii sp. nov.) isolates. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1995;33:2427–2434. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.9.2427-2434.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Marconi RT, Samuels DS, Garon CF. Transcriptional analyses and mapping of the ospC gene in Lyme disease spirochetes. J. Bacteriol. 1993;175:926–932. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.4.926-932.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Margos G, Gatewood AG, Aanensen DM, Hanincova K, Terekhova D, et al. MLST of housekeeping genes captures geographic population structure and suggests a European origin of Borrelia burgdorferi. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:8730–8735. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800323105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Martin AP, Costello EK, Meyer AF, Nemergut DR, Schmidt SK. The rate and pattern of cladogenesis in microbes. Evolution. 2004;58:946–955. doi: 10.1111/j.0014-3820.2004.tb00429.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Masuzawa T, Takada N, Kudeken M, Fukui T, Yano Y, et al. Borrelia sinica sp. nov., a Lyme disease–related Borrelia species isolated in China. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2001;51:1817–1824. doi: 10.1099/00207713-51-5-1817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Maynard Smith J. The Evolution of Sex. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Univ. Press; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 106.Maynard Smith J, Dowson CG, Spratt BG. Localized sex in bacteria. Nature. 1991;349:29–31. doi: 10.1038/349029a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]