Summary

Mouse models, with their well-developed genetics and similarity to human physiology and anatomy, serve as powerful tools with which to investigate the etiology of human retinal degeneration. Mutant mice also provide reproducible, experimental systems for elucidating pathways of normal development and function. Here, I describe the tools used in the discoveries of many retinal degeneration models, including indirect ophthalmoscopy (to look at the fundus appearance), fundus photography and fluorescein angiography (to document the fundus appearance), electroretinography (to check retinal function) as well as the heritability test (for genetic characterization).

Keywords: Mouse models, Retinal degeneration, Indirect ophthalmoscopy, Fundus, Electroretinography

1. Introduction

The number of known serious or disabling eye diseases in humans is large and affects millions of individuals world-wide. Yet research on these diseases frequently is limited by the obvious restrictions on studying pathophysiologic processes in the human eye. Mouse models of inherited ocular disease provide powerful tools for genetic analysis and characterization and intervention assessment. Studies of mouse models of human retinal degeneration are important to understanding the pathophysiology, as well as the etiology, of these diseases. Using these mouse models much progress has been made in elucidating gene defects underlying retinal disease, understanding mechanisms leading to disease, and designing molecules for translational research and gene-based therapy to interfere with the progression of disease.

Discovery of human retinal degenerations is not particularly difficult when patients visit their ophthalmologist for eye examinations, but research on human retinal degenerations is impeded by the lack of availability of human eye tissues and the impossibility of doing genetic manipulation for research. Human eye tissue (including biopsies) for most human ocular diseases is seldom available because it is difficult to obtain tissue samples from the eye without risk of damage to the patient's vision. Compared with diagnosis in humans, animal models of human retinal degeneration are not easy to find, but animal models make research advances feasible not only through developmental and invasive studies, but also through rapid genetic analysis. By screening mice using indirect ophthalmoscopy and electroretinography at The Jackson Laboratory, many mouse models of retinal degeneration and diseases have been discovered (1, 2). A major advantage in using the mouse as a model system is the depth of well-developed techniques available for manipulating the genome. The ability to target and alter a specific gene(s) is an important and necessary tool to produce mouse models with mutations in genes of choice. Inducing mutations in genes of choice (known as knockout or transgenic) is termed “reverse genetics,” as it is the opposite of “forward genetics” approaches whereby spontaneous/induced mutations are discovered as a result of the overt phenotypes and the underlying mutation is subsequently identified. Through the “forward” and “reverse” genetic approaches, mouse models in 100 genes that underlie human retinal diseases have been studied (3). In some cases there are multiple models available for the same mutated gene. For example, of the mouse models for human Leber Congenital Amaurosis 2 (LCA2) caused by mutation in the Rpe65 (retinal pigment epithelium 65) gene, there is a knockout model Rpe65tm1Tmr (4), a transgenic (knockin) model Rpe65tm1Lrcb (5), an induced model Rpe65tvrm148 (2), as well as a spontaneous model Rpe65rd12 (6, 7). The mouse eye is remarkably similar in structure to the human eye, and both species have many similar ocular disorders. Not only are developmental and invasive studies possible in mice, but the mouse's accelerated life span and generation time (one mouse year = about 30 human years) make it possible to follow the natural progression of eye diseases in a relatively brief length of time. Because mouse mutations can be maintained on controlled genetic backgrounds, mutant and control mice can differ only by the mutated gene being studied. Thus, it is possible to analyze the effects of a mutant gene in same-sex, same-age littermates that differ only by whether they carry a specific mutation.

Models of retinal degeneration in mice have been known for many years. The first retinal degeneration, discovered by Dr. Clyde E. Keeler more than 80 years ago, is Pde6brd1 (formerly rd1, rd, identical with Keeler rodless retina, r) (8-10). Fifty years later, the second retinal degeneration was discovered and it was named retinal degeneration-slow (Rds) (11). The third retinal degeneration was discovered in 1993 and it was named rd3 in sequence allowing rd to be equivalent to rd1 and Rds to be equivalent to Rd2 (12). During the last 20 years, many mouse models of retinal degeneration have been found because common methods used in human clinical eye examinations have been adapted for use with mouse eyes to screen for mouse retinal degeneration (1, 2, 12-14). These methods, including indirect ophthalmoscopy, fundus photography, fluorescein angiography, electroretinography as well as histology, are broadly used in identifying and characterizing mouse models of retinal degeneration and diseases.

2. Materials

The Jackson Laboratory (TJL), having the world's largest collection of mouse mutant stocks and genetically diverse inbred strains (http://jaxmice.jax.org/index.html), is an ideal place to discover and characterize genetically determined retinal disorders.

2.1. Mice

The mice were bred and maintained in standardized conditions in the Research Animal Facility at TJL. They were maintained on NIH31 6% fat chow and acidified water, with a 14-hour light/10-hour dark cycle in conventional facilities that were monitored regularly to maintain a pathogen-free environment. All experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and conducted in accordance with the ARVO Statement for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research.

2.2. Drugs and chemicals

1% Atropine Sulfate Ophthalmic Solution (sterile), Alcon Laboratories, INC. Fort Worth, Texas 76134 USA.

1% Cyclopentolate Hydrochloride Ophthalmic Solution USP (sterile), Bausch & Lomb Incorporated Tampa, FL 33637 USA.

Cyclomydril® (0.2% cyclopentolate hydrochloride, 1% phenylephrine hydrochloride ophthalmic solution, sterile), Alcon Laboratories, INC. Fort Worth, Texas 76134 USA.

2.5% Gonioscopic Prism Solution (Hypromellose Ophthalmic Demuicent Solution, sterile), Wilson Ophthalmic, Mustang, OK 73064 USA.

25% Fluorescein Sodium Injection (250 mg per ml, for intravenous injection only), Altaire Pharmaceuticals, INC., Aquebogue, NY11931 USA.

Ketathesia (ketamine HCL injection USP, 100 mg per ml), Dublin, OH 43017 USA.

AnaSed® Injection (Xylazine sterile solution, 20 mg per ml), Shenandoah, Iowa 51601 USA.

0.9% Sodium Chloride, INJ., USP (for use as sterile diluents), Hospira, INC., Lake Forest, IL 60045 USA.

2.3. Ophthalmic Instruments and Equipments

Heine Omega 500® Binocular Indirect Ophthalmoscope (Fig. 1), Heine USA Ltd., 10 Innovation Way, Dover, NH 03820.

Classic 78D, Classic 90D, SuperField NC Volk Optical Lenses, Volk Optical, Inc., 7893 Enterprise Drive, Mentor, OH 44060 USA.

Kowa Genesis small animal fundus camera (Fig. 1)(Tokyo, Japan)(15).

Canon digital camera (Canon EOS Rebel Xsi) (Fig. 1) (Canon U.S.A., Inc., headquartered in Lake Success, New York, USA).

Figure 1.

Ophthalmic instruments used for mouse fundus examination.

Figure 2.

The major components of the electroretinogram system used in our laboratory.

3. Methods

Retinal vessel attenuation and retinal pigment epithelial disturbance are easily detected signs that are often associated with retinal degenerations and diseases. However if the retina looks normal (normal fundus), it is still possible that retinal functional abnormalities exist. A quick screening ERG test is needed to detect any retinal functional defects, such as retinal cone photoreceptor function loss (achromatopsia)(17, 18) and no b-wave (nob) mutations (19, 20). Heritability is subsequently established by genetic characterization (1, 2).

3.1. Mouse fundus examination

For indirect ophthalmoscopy the examiner wears a light attached to a headband and uses a small handheld lens to see inside the fundus of the mouse eye. The fundus of a mouse eye is the interior surface of the eye and includes the retina and optic disc. The color of the mouse fundus varies between pigmented (black) and albino (red). Dilated fundus examination is a diagnostic procedure that employs the use of mydriatic eye drops (such as 1% atropine) to dilate or enlarge the pupil in order to obtain a better view of the fundus of the eye. Once the pupil is dilated, examiners often use specialized equipment such as an indirect ophthalmoscope or fundus camera to view the inner surfaces of the eye. Abnormal signs that can be detected from observation of mouse fundus include hemorrhages, exudates, cotton wool spots, blood vessel abnormalities (tortuosity, pulsation and new vessels) and pigmentation. Mouse fundus examination is a more effective method for the evaluation of internal ocular health and is routinely used to screen whether a mouse presents with abnormalities of the fundus such as retinal degeneration, optic disc coloboma, or vascular problems (see Note 1).

3.1.1. Routine fundus examination

Pupil dilation: Remove the screw top from the vial containing the mydriatic (1% atropine). Restrain and hold the mouse firmly in one hand, pick up the vial containing the mydriatic and squeeze directly above an eye of the mouse allowing a drop to cover the surface of the eye. Repeat the procedure for the second eye. Return the mouse to its cage and allow at least 5 minutes for the effect of the mydriatic to take place.

Fundus examination 1: Place the Heine Omega 500® Binocular Indirect Ophthalmoscope onto your head and adjust the binoculars accordingly. Adjust the light being emitted from the ophthalmoscope. Hold and restrain the mouse firmly in one hand and shine the light into the mouse eye to see if the pupil has fully dilated (Fig. 3).

Fundus examination 2: Pick up the Volk 90D or 78D lens and place it between the mouse eye and the beam of light. Pass (or focus) the beam of light through the Volk lens and you should see the mouse eye through the lens. Adjust the lens in and out until the back of the retina can be visualized. Orientate the field of view by visualizing the optic disc and then moving the lens around the eye (or twist the mouse head) to alter the view so the whole fundus can be examined.

Repeat the above for the second eye examination.

Record the fundus appearance, such as retinal spots, retinal pigment patch or retinal vessels changes. If any fundus abnormalities are observed, fundus photography is taken. If no fundus abnormalities are observed, this mouse will go through the simple screening ERG test.

Figure 3.

An eye prior to dilation in pigmented mice (A) and albino mice (B) and the pupil of the same eye in its dilated state (C, D).

3.1.2. Fundus photography and fluorescein angiography

Mouse fundus photography and fluorescein angiography are used to document the new phenotypes discovered by fundus examination. In the past, we used the Kowa Genesis small animal fundus camera fitted to a dissection microscope base (15) to take fundus pictures with special films, but have improved the efficiency and reduced the cost of this system by adapting a digital camera (Canon EOS Rebel Xsi) to focus through the eyepiece view (Fig. 1). This Canon digital camera can be directly connected to a personal computer (through the USB port) and the fundus view is displayed on the computer monitor. Fundus pictures are then captured and saved on the computer by using the Canon EOS utility software.

Pupil dilation, same as step 1 in section 3.1.1 above.

Plug the Canon camera USB cable to the computer's USB port and turn on the computer (the Canon EOS utility software should be installed first).

Switch the Canon camera power on and wait for the Canon EOS utility software to start. Once the Canon EOS utility software is running, select the “Camera Setting/Remote Shooting”, then select “Remote Live View Shooting” from the software menu.

Turn on the power (light) from the powerpack and the “Remote Live View Shooting” window lights up on the computer monitor.

Hold and restrain the mouse firmly in one hand and place the mouse eye under the light beneath the Volk lens to see on the computer monitor if the pupil has fully dilated (Fig. 3). Retract the mouse eyelids with two fingers from your other hand, orientate the field of view by visualizing the optic disc and then move the mouse eye around until you get the best fundus view (the most focused).

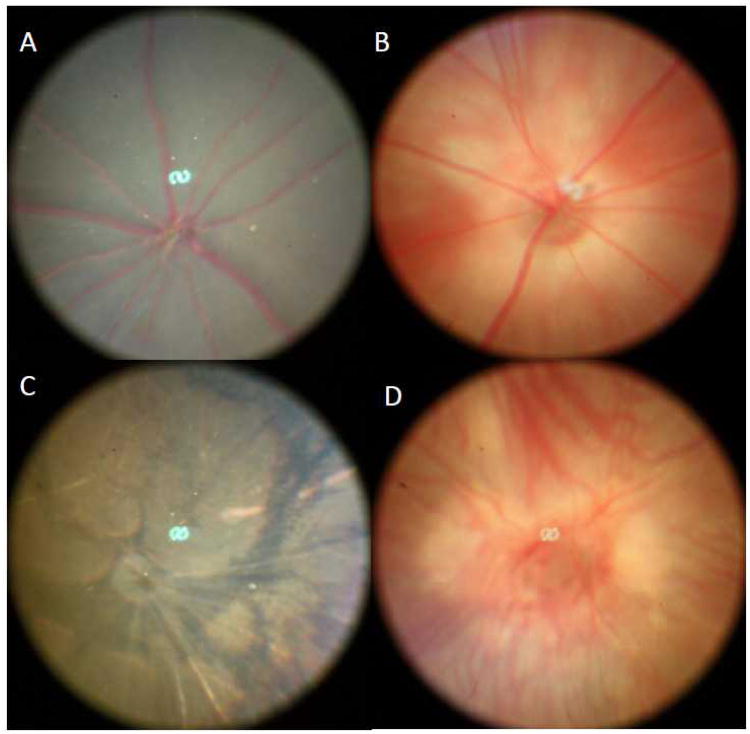

Capture the fundus images by a foot pedal (to operate the shutter) when the best fundus view occurs on the computer monitor. Figure 4 shows the normal mouse fundus in pigmented mice (C57BL/6J) as well as albino mice (BALB/cJ) and abnormal fundus in pigmented mice (C3H/HeJ) mice as well as albino mice (FVB/NJ) mice (see Note 2).

For retinal angiography the same general fundus photography procedure is used except one must push a button on the powerpack to select the fluorescein filter for angiography.

Intraperitoneally inject the mouse with 25% sodium fluorescein at a dose of 0.01 ml per 5-6 gm body weight. The retinal vessels began filling about 30 seconds after fluorescein administration. Single photographs are then taken at appropriate intervals. Although timing varies due to variable rates of intraperitoneal absorption, capillary washout usually occurs 5 minutes after dye administration. Figure 5 shows the mouse fundus as well as fluorescein angiogram.

Figure 4.

Normal mouse fundus in pigmented mice (A) and albino mice (B) as well as retinal degeneration fundus in pigmented mice (C) and albino mice (D).

Figure 5.

Normal mouse fundus prior to the fluorescein injection (A) and the same eye after the fluorescein injection (C). Mouse fundus with neovascular depigmented spots (B) prior to the fluorescein injection and the same eye after the fluorescein injection (D).

3.2. Simple Screening Electroretinograpy

The basic method of recording the electrical response, known as the global or full-field Electroretinogram (ERG), is to stimulate the eye with a bright light source such as a flash produced by LEDs or a strobe lamp. The flash of light elicits a biphasic waveform recordable at the cornea. The two components that are most often measured are the a- and b-waves. The a-wave is the first large negative component, followed by the b-wave which is corneal positive and usually larger in amplitude. Two principal measures of the ERG waveform are taken: 1) The amplitude (a) from the baseline to the negative trough of the a-wave, and the amplitude of the b-wave measured from the trough of the a-wave to the following peak of the b-wave; and 2) the time (t) from flash onset to the trough of the a-wave and the time (t) from flash onset to the peak of the b-wave. These times, reflecting peak latency, are referred to as “implicit times” in the jargon of electroretinography. Scotopic ERGs (also called dark-adapted) are used to evaluate responses starting from rod photoreceptors exposed to flush light in darkness, and photopic ERGs (also called light-adapted) are used to evaluate responses starting from cone photoreceptors exposed to flush light under constant light exposure. Because regular ERG testing is time consuming (about 30 to 60 minutes per mouse without the time used for dark adaption), we have developed a simple screening ERG test. Our simple screening ERG testing does not need dark or light adaption and one simple ERG test takes less than 10 minutes (see Note 3). Most of the simple screening ERGs are normal and only a few of them are abnormal, but once a mouse shows an abnormal ERG, it is tested again through our regular ERG test (21, 22).

Pupil dilation: Restrain and hold the mouse firmly in one hand, pick up the vial containing 1% Cyclopentolate (1% Cyclopentolate Hydrochloride Ophthalmic Solution) and squeeze directly above the right eye of the mouse allowing a drop to cover the surface of the eye (we test only one eye and usually the right eye). A group of 5 to 10 mice can be dilated in one time.

Anesthetize the mouse with an intraperitoneal injection. Weigh the mouse and record the weight. Restrain and hold the mouse firmly in one hand, pick up the second vial containing Cyclomydril (0.2% cyclopentolate hydrochloride, 1% phenylephrine hydrochloride ophthalmic solution, sterile) and squeeze directly above the right eye a drop to cover the surface of the eye; then inject the mouse with the anesthetic mixture solution (5 ml mixture containing 0.8 ml Katamine, 0.8 ml Xylazine and 3.4 ml 0.9% Sodium Chloride) at a dosage of 0.1 ml per 20 grams of body weight.

Prepare the test: Place the sufficiently sedated mouse on the heated pad. Insert a needle probe just under the skin at the base of the tail, place the gold loop electrode between the gum and cheek, position the mouse near the far end of the heating pad and place the active gold loop electrode on the cornea slightly below the middle of the eye. Pick up the third vial containing 2.5% Gonioscopic Prism Solution and squeeze directly above the cornea and electrode a drop to assure a good contact.

The simple ERG test: Set the photic Stimulator to 1 second flash, the flash intensity to 16 (the highest), then set the “Sweeps” to 10 (average 10 flashes) from the ERG software menu. Click the “Aver” from the software menu, then turn on the photic Stimulator to start the test.

Save the test data and analyze the results: Press the “Save” button to save the ERG data to the computer and print a copy for instant view. If a mouse has a b-wave amplitude at or above 100 μV and the implicit times at about 50 msec, this mouse has a normal simple ERG response (Fig. 6 A). If a mouse has b-wave amplitude at or below 50 μV and implicit times longer than 50 msec, this mouse has an abnormal simple ERG response (Fig. 6 B).

Regular ERG test: Once we discover a mouse with an abnormal simple ERG response, we test the same mouse with our regular ERG protocol to determine if the mouse has the abnormal rod response (dark-adapted ERG) or abnormal cone ERG response (light-adapted ERG) or abnormal rod and cone ERG. Then we mate this mouse to a normal mouse to produce the next generation for the heritability test.

Figure 6.

Representative ERG responses to a bright flash obtained from a mouse with normal retinal function (A) and a mouse with abnormal retinal function (B).

3.3. Heritability test

Heritability is established by outcrossing a retinal mutant mouse to a normal retinal wild-type mouse to generate F1 progeny, with subsequent intercrossing of the resultant F1 mice to generate F2 progeny. Both F1 and F2 mice are examined by fundus examination and/or simple screening ERG depending on which phenotype occurs first. If F1 mice are affected, the pedigree is designated as a dominant mutation. If F1 mice are not affected but ∼25% of F2 mice are affected, the pedigree is designated as a recessive mutation. Once heritability of the observed retinal phenotype is established, retinal mutants are bred and maintained for further characterization leading to gene identification (23, 24).

Acknowledgments

This work has been supported by the Macula Vision Research Foundation (MVRF) and the National Eye Institute Grant EY19943. I am grateful to Mark Lessard and David Davis for adapting the Canon Digital Camera to our mouse fundus camera, and Melissa Berry and Da Chang for their critical reading and editing of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Mouse fundus examination is a very powerful, non-invasive and high throughput method for evaluating mouse retinal appearances. It is also very effective in screening for mouse models of human retinal degeneration and diseases, as there are many examples of mouse models of retinal degeneration that were discovered by fundus examination (see Ref. 1, 2, 13) such as mouse retinal degeneration 3 (Rd3rd3)(see Ref. 12, 25) and mouse retinal degeneration 4 (Gnb1Rd4) (see Ref. 26, 27).

It is important for investigators evaluating eyes to be aware of Pde6brd1 and its associated morphological findings, as it is a frequent strain background disease. Since the Pde6brd1 mutation is common in mice, it is important to avoid mouse strains or stocks carrying the Pde6brd1 allele, or to exclude the Pde6brd1 allele contamination in studying new retinal disorders. Mice with the Pde6brd1 mutation can be easily typed by fundus examination (see Fig. 4).

The simple screening ERG is another powerful, non-invasive and high throughput method to evaluate mouse retinal function. If a mouse has a normal fundus through fundus examination, it is very important to run this mouse through the simple screening ERG test because mouse retinal function loss mutants can have a normal retinal appearance (see Ref. 17-20).

References

- 1.Chang B, Hawes NL, Hurd RE, Wang J, Howell D, Davisson MT, Roderick TH, Nusinowitz S, Heckenlively JR. Mouse models of ocular diseases. Vis Neurosci. 2005;22:587–593. doi: 10.1017/S0952523805225075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Won J, Shi LY, Hicks W, Wang J, Hurd R, Naggert JK, Chang B, Nishina PM. Mouse model resources for vision research. J Ophthalmol. 2011;2011:391384. doi: 10.1155/2011/391384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Samardzija M, Neuhauss SCF, Joly S, Kurz-Levin M, Grimm C. Animal Models for Retinal Degeneration. In: Pang I, Clark AF, editors. Animal Models for Retinal Diseases. The Human Press, Inc.; 2010. pp. 51–79. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Redmond TM, Yu S, Lee E, Bok D, Hamasaki D, Chen N, Goletz P, Ma JX, Crouch RK, Pfeifer K. Rpe65 is necessary for production of 11-cis-vitamin A in the retinal visual cycle. Nat Genet. 1998;20(4):344–51. doi: 10.1038/3813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Samardzija M, von Lintig J, Tanimoto N, Oberhauser V, Thiersch M, Reme CE, Seeliger M, Grimm C, Wenzel A. R91W mutation in Rpe65 leads to milder early-onset retinal dystrophy due to the generation of low levels of 11-cis-retinal. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17(2):281–92. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chang B, Hawes NL, Hurd RE, Davisson MT, Nusinowitz S, Heckenlively JR. A point mutation in the Rpe65 gene causes retinal degeneration (rd12) in mice. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2002;3670 Abstr. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pang JJ, Chang B, Hawes NL, Hurd RE, Davisson MT, Li J, Noorwez SM, Malhotra R, McDowell JH, Kaushal S, Hauswirth WW, Nusinowitz S, Thompson DA, Heckenlively JR. Retinal degeneration 12 (rd12): a new, spontaneously arising mouse model for human Leber congenital amaurosis (LCA) Mol Vis. 2005;11:152–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Keeler C. The inheritance of a retinal abnormality in white mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1924;10:329. doi: 10.1073/pnas.10.7.329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Keeler C. Retinal degeneration in the mouse is rodless retina. J Hered. 1966;57(2):47–50. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jhered.a107462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pittler SJ, Keeler CE, Sidman RL, Baehr W. PCR analysis of DNA from 70-year-old sections of rodless retina demonstrates identity with the mouse rd defect. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90(20):9616–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.20.9616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van Nie R, Ivanyi D, Demant P. A new H-2-linked mutation, rds, causing retinal degeneration in the mouse. Tissue Antigens. 1978;12(2):106–108. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0039.1978.tb01305.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chang B, Heckenlively JR, Hawes NL, Roderick TH. New mouse primary retinal degeneration (rd-3) Genomics. 1993;16(1):45–49. doi: 10.1006/geno.1993.1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chang B, Hawes NL, Hurd RE, Davisson MT, Nusinowitz S, Heckenlively JR. Retinal degeneration mutants in the mouse. Vision Res. 2002;42(4):517–25. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6989(01)00146-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chang B, Hawes N, Davisson M, Heckenlively J. Mouse models of RP. In: Tombran-Tink J, Barnstable C, editors. Retinal Degenerations: Biology, Diagnostics, and Therapeutics. The Human Press, Inc.; 2007. pp. 149–164. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hawes NL, Smith RS, Chang B, Davisson M, Heckenlively JR, John SMM. Mouse fundus photography and angiography: A catalogue of normal and mutant phenotypes. Molecular Vision. 1999;5:22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nusinowitz S, Ridder WH, III, Heckenlively JR. Electrophysiological Testing of The Mouse Visual System. In: Smith RS, editor. Systematic Evaluation of The Mouse Eye: Anatomy, Pathology, and Biomethods. CRC Press; 2002. pp. 320–344. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chang B, Dacey MS, Hawes NL, Hitchcock PF, Milam AH, Atmaca-Sonmez P, Nusinowitz S, Heckenlively JR. Cone photoreceptor function loss-3, a novel mouse model of achromatopsia due to a mutation in Gnat2. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47(11):5017–21. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-1468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chang B, Grau T, Dangel S, Hurd R, Jurklies B, Sener EC, Andreasson S, Dollfus H, Baumann B, Bolz S, Artemyev N, Kohl S, Heckenlively J, Wissinger B. A homologous genetic basis of the murine cpfl1 mutant and human achromatopsia linked to mutations in the PDE6C gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106(46):19581–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0907720106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chang B, Heckenlively JR, Bayley PR, Brecha NC, Davisson MT, Hawes NL, Hirano AA, Hurd RE, Ikeda A, Johnson BA, McCall MA, Morgans CW, Nusinowitz S, Peachey NS, Rice DS, Vessey KA, Gregg RG. The nob2 mouse, a null mutation in Cacna1f: Anatomical and functional abnormalities in the outer retina and their consequences on ganglion cell visual responses. Vis Neurosci. 2006;23(1):11–24. doi: 10.1017/S095252380623102X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maddox DM, Vessey KA, Yarbrough GL, Invergo BM, Cantrell DR, Inayat S, Balannik V, Hicks WL, Hawes NL, Byers S, Smith RS, Hurd R, Howell D, Gregg RG, Chang B, Naggert JK, Troy JB, Pinto LH, Nishina PM, McCall MA. Allelic variance between GRM6 mutants, Grm6nob3 and Grm6nob4 results in differences in retinal ganglion cell visual responses. J Physiol. 2008;586(Pt 18):4409–24. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.157289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hawes NL, Chang B, Hageman GS, Nusinowitz S, Nishina PM, Schneider BS, Smith RS, Roderick TH, Davisson MT, Heckenlively JR. Retinal degeneration 6(rd 6): a new mouse model for human retinitis punctata albescens. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2000;41(10):3149–3157. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chang B, Hawes NL, Pardue MT, German AM, Hurd RE, Davisson MT, Nusinowitz S, Rengarajan K, Boyd AP, Sidney SS, Phillips MJ, Stewart RE, Chaudhury R, Nickerson JM, Heckenlively JR, Boatright JH. Two mouse retinal degenerations caused by missense mutations in the “beta”-subunit of rod cGMP phosphodiesterase gene. Vis Res. 2007;47:624–633. doi: 10.1016/j.visres.2006.11.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Friedman JS, Chang B, Krauth DS, Lopez I, Waseem NH, Hurd RE, Feathers KL, Branham KE, Shaw M, Thomas GE, Brooks MJ, Liu C, Bakeri HA, Campos MM, Maubaret C, Webster AR, Rodriguez IR, Thompson DA, Bhattacharya SS, Koenekoop RK, Heckenlively JR, Swaroop A. Loss of lysophosphatidylcholine acyltransferase 1 leads to photoreceptor degeneration in rd11 mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010 Aug 31;107(35):15523–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1002897107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chang B, Khanna H, Hawes N, Jimeno D, He S, Lillo C, Parapuram SK, Cheng H, Scott A, Hurd RE, Sayer JA, Otto EA, Attanasio M, O'toole JF, Jin G, Shou C, Hildebrandt F, Williams DS, Heckenlively JR, Swaroop A. An in-frame deletion in a novel centrosomal/ciliary protein CEP290/NPHP6 perturbs its interaction with RPGR and results in early-onset retinal degeneration in the rd16 mouse. Hum Mol Genet. 2006;15(11):1847–1857. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Friedman JS, Chang B, Kannabiran C, Chakarova C, Singh HP, Jalali S, Hawes NL, Branham K, Othman M, Filippova E, Thompson DA, Webster AR, Andreasson S, Jacobson SG, Bhattacharya SS, Heckenlively JR, Swaroop A. Premature truncation of a novel protein, RD3, exhibiting subnuclear localization is associated with retinal degeneration. Am J Hum Genet. 2006;79(6):1059–70. doi: 10.1086/510021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Roderick TH, Chang B, Hawes NL, Heckenlively JR. A new dominant retinal degeneration (Rd4) linked with a chromosome 4 inversion in the mouse. Genomics. 1997;42(3):393–6. doi: 10.1006/geno.1997.4717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kitamura E, Danciger M, Yamashita C, Rao NP, Nusinowitz S, Chang B, Farber DB. Disruption of the Gene Encoding the {beta}1-Subunit of Transducin in the Rd4/+ Mouse. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47(4):1293–301. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-1164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]