Significance

Cytokines are proteins that modulate the activity of target cells via activation of cell-surface receptors. The trimeric cytokines of the tumor necrosis factor superfamily typically signal by inducing homotrimerization of their cognate receptors. We use structural and biophysical approaches to show that the unique heterotrimeric tumor necrosis factor superfamily member Lymphotoxin (LT)α1β2 induces dimerization rather than trimerization of the LTβ Receptor (LTβR). Cellular signaling assays were used to show that dimerization of LTβR is sufficient to activate intracellular signaling processes. Furthermore, disruption of receptor interactions at either site prevents signaling via LTβR, challenging the existing paradigm that trimeric complexes are required for signal transduction by the TNF family cytokines.

Keywords: crystallography, cytokines, mechanism, biophysics

Abstract

Homotrimeric TNF superfamily ligands signal by inducing trimers of their cognate receptors. As a biologically active heterotrimer, Lymphotoxin(LT)α1β2 is unique in the TNF superfamily. How the three unique potential receptor-binding interfaces in LTα1β2 trigger signaling via LTβ Receptor (LTβR) resulting in lymphoid organogenesis and propagation of inflammatory signals is poorly understood. Here we show that LTα1β2 possesses two binding sites for LTβR with distinct affinities and that dimerization of LTβR by LTα1β2 is necessary and sufficient for signal transduction. The crystal structure of a complex formed by LTα1β2, LTβR, and the fab fragment of an antibody that blocks LTβR activation reveals the lower affinity receptor-binding site. Mutations targeting each potential receptor-binding site in an engineered single-chain variant of LTα1β2 reveal the high-affinity site. NF-κB reporter assays further validate that disruption of receptor interactions at either site is sufficient to prevent signaling via LTβR.

The TNF receptor and ligand superfamilies (TNFRSF and TNFSF, respectively) play critical roles in mammalian biology and mediate proinflammatory immune responses. Lymphotoxin (LT)-α and LTβ are two related TNFSF members produced predominately by activated cells of the innate and adaptive immune response. LTα exists as a secreted homotrimeric molecule (LTα3) that signals via TNFR1 and TNFR2, or as a heterotrimer with LTβ on the cell surface (major form LTα1β2, minor form LTα2β1) and signals through the LTβ receptor (LTβR) (1). As a heterotrimer rather than a homotrimer, LTα1β2 is unique in the TNFSF.

The role of LT in the immune response has been well characterized as critical for the development and orchestration of robust immune responses (2). Signaling through LTβR, expressed on nonhematopoeitic cells and follicular dendritic cells, directs normal development of lymph nodes and appropriate germinal center architecture via the elaboration of various cytokines and chemokines, as revealed in LTα-, LTβ-, or LTβR-deficient mice (3, 4). During chronic immune responses, cellular effectors can infiltrate target tissue and organize anatomically into de novo lymphoid structures, instigated and maintained by LT-mediated pathways (5).

Surface LTα1β2 is detected on subsets of activated T and B cells and NK cells (6–9). Dysregulation of these immune cell types underlies the pathogenesis of autoimmune diseases. In mouse models of rheumatoid arthritis (RA), experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE), and delayed-type hypersensitivity (DTH), treatment with a depleting antibody specific to murine LTα resulted in amelioration of disease in all circumstances. In these studies, the Fc-dependent efficacy achieved with anti-LTα resulted from depletion of pathogenic LT-expressing Th1 and Th17 cells. Moreover, blockade of LTβR signaling using a decoy receptor fusion protein, LTβR-Ig, was sufficient to drive efficacy in a number of autoimmune models when delivered preventatively (10). Motivated by the concerted effects of LTα and LTβ in driving major inflammatory pathways and pathologies, we previously generated a humanized anti-LTα mAb (MLTA3698A, hereafter referred to as anti-LTα), and demonstrated increased survival in a xenogeneic human T-cell–dependent mouse model of graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) (11).

TNFRSF members are typically activated by TNFSF-induced trimerization or higher order oligomerization, resulting in initiation of intracellular signaling processes including the canonical and noncanonical NF-κB pathways (2, 3). Ligand–receptor interactions induce higher order assemblies formed between adaptor motifs in the cytoplasmic regions of the receptors such as death domains or TRAF-binding motifs and downstream signaling components such as Fas-associated protein with death domain (FADD), TNFR1-associated protein with death domain (TRADD), and TNFR-associated factor (TRAF). In particular, LTβR signals via TRAF3 and the structure of a peptide derived from the intracellular region of LTβR bound to the TRAF3 C-terminal domain revealed a 3:3 trimeric complex (12, 13).

Most TNFSF ligands are compact homotrimers formed by protomers possessing a conserved beta-strand jellyroll fold. Each protomer is formed by an inner and outer β-sheet consisting of strands A’AHCF and B’BGDE, respectively (14). In contrast, multidomain TNFRSFs have an elongated shape and are composed of pseudorepeats of ∼40 residue cysteine-rich domains (CRDs). The extracellular domain (ECD) of LTβR comprises four CRDs and is expected to have similar overall architecture to other multidomain TNFRSF members such as TNFR1. Crystal structures of several ligand–receptor complexes in this superfamily (15–23) revealed that receptors bind in a symmetrical manner at the monomer–monomer interfaces of the ligands, with CRD2 and CRD3 mediating most receptor–ligand interactions (Fig. S1A).

Unlike most TNFSF ligands, biochemical studies surprisingly indicated that the LIGHT [TNFSF member homologous to LT, inducible expression, competes with herpes simplex virus (HSV) glycoprotein D for HSV entry mediator (HVEM), a receptor expressed on T lymphocytes; TNFSF14] homotrimer and the LTα1β2 heterotrimer are only capable of binding two copies of their cognate receptor, LTβR. However, difficulty in making recombinant, soluble LTα1β2 precluded further characterization (1). Nonetheless, the inherent asymmetry of the LTα1β2 heterotrimer suggests three distinct possible receptor-binding sites in LTα1β2 as opposed to three equivalent sites in a homotrimer (Fig. S1 B and C). Herein we draw on structural, biochemical, and cellular data to show that dimeric clustering of LTβR by the LTα1β2 heterotrimer triggers signal transduction and that disrupting one receptor-binding site on LTα1β2 is sufficient to block signaling through LTβR.

Results

Anti-LTα Binds to LTα at a Different Site from TNFR1 and Blocks Signaling by Both TNFR1 and LTβR.

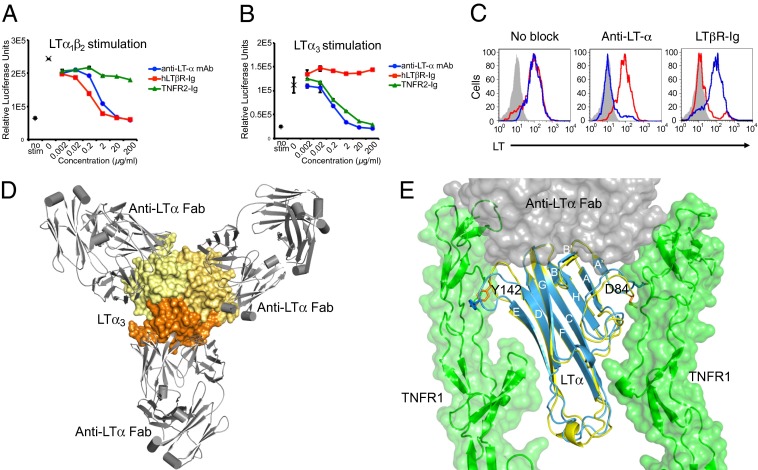

To assess the binding of anti-LTα toward LTα3 and LTα1β2, we stimulated HeLa cells stably transfected with an NF-κB luciferase reporter with LTα1β2 and LTα3 in the presence or absence of increasing concentrations of either anti-LTα, LTβR-Ig, or TNFR2-Ig (Fig. 1 A and B). As expected, anti-LTα blocked LTα3 and LTα1β2-induced NF-κB activation comparable to the blockade seen with TNFR2-Ig and LTβR-Ig, similar to previous observations in competition ELISAs (11). Surprisingly, despite the inability of anti-LTα to prevent LTβR-Ig binding to LTα1β2 on cells, as determined by FACS (Fig. 1C), anti-LTα fully blocked LTα1β2-induced NF-κB activation.

Fig. 1.

Anti-LTα binds to a single protomer in LTα3, and LTα1β2 blocks signaling through TNFR2 and LTβR. (A) Anti-LTα mAb and LTβR-Ig block NF-κB activation through LTα1β2. HeLa/NF-κB-luc cells endogenously expressing LTβR were stimulated with LTα1β2. (B) Anti-LTα mAb and human TNFR2-Ig block NF-κB activation through LTα3, but LTβR-Ig does not. HeLa/NF-κB-luc reporter cells endogenously expressing TNFR2 were stimulated with WT–LTα3. In both A and B, NF-κB activity was measured in relative luciferase units; baseline activity in unstimulated cells (no stim, + symbol) and activity in stimulated cells in absence of blockade (x symbol) are indicated. Data are shown as mean ± SD of duplicate wells from duplicate plates. Data are representative of at least two experiments. (C) Anti-LTα mAb and LTβR-Ig cobind to LTα− and LTβ-expressing 293 cells. Surface LTα and LTβ expression on 293-hLTαβ cells is shown using anti-LTα mAb (blue) or LTβR-Ig (red). Light-shaded histogram represents staining with isotype control antibody. Cobinding of both LTα-specific mAb and LTβR-Ig was determined by preincubating 293-hLTαβ cells with LTα-specific mAb or LTβR-Ig followed by staining for surface LT. (D) Crystal structure of the LTα3–(anti-LTα Fab)3 complex shows each anti-LTα Fab molecule (gray) recognizing a single protomer within the LTα3 homotrimer (shades of yellow). (E) Anti-LTα Fab (gray) binding to LTα (blue) induces a conformational change in the DE- and AA’-loops altering positions of residues Y142 and D84 relative to LTα (yellow) in complex with TNFR1 (green) (PDB ID code 1TNR).

To elucidate the molecular basis of signal disruption by anti-LTα, we determined the X-ray crystal structure of the complex of LTα3 with the Fab fragment of anti-LTα at 3.2 Å (Table S1). This complex retains the threefold symmetry of the LTα3 trimer. Each LTα protomer binds one copy of anti-LTα Fab (Fig. 1D). Strands A’, B’, and B and the DE-loop and the FG-loop on the outer surface of the monomer comprise the majority of the anti-LTα epitope (Fig. 1E). This binding mode differs from that seen in a structure of CD40L bound to the fab fragment of a blocking antibody (24) in which the antibody directly competes for the receptor-binding site. Like anti-LTα, the Fab fragment of infliximab with TNF (25) also binds to the outer surface of a single monomer of TNF. However, the infliximab–TNF interaction centers on the EF loop in the tip of the trimer, whereas anti-LTα Fab binds to the wide part of the trimer.

Overlay of the LTα3–(anti–LTα-Fab)3 and the LTα3–TNFR13 structures unexpectedly revealed minimal overlap between the TNFR1 epitope and the anti-LTα epitope (Fig. S1 D and E). However, the Fab occupies part of the same 3D space as would be occupied by receptor during a signaling event, suggesting that steric hindrance contributes to the ability of anti-LTα to compete with TNFR1 or TNFR2 for ligand. Anti-LTα binding also changes the conformation of the LTα DE and the AA’ loops, which contain the critical residues Y142 and D84, which are essential for receptor binding and cytotoxic activity of LTα (26). This conformational change is an allosteric effect, as anti-LTα does not directly contact these residues. The DE and AA’ loops are on opposite sides of LTα protomer (Fig. 1E) and form opposing surfaces of the receptor-binding cleft (15). As such, alteration of the conformation of these loops affects two separate monomer–monomer interfaces. Thus, despite binding to a single LTα protomer, one anti-LTα affects two receptor-binding sites.

LTα1β2 Binds Two Copies of LTβR with Distinct Affinities.

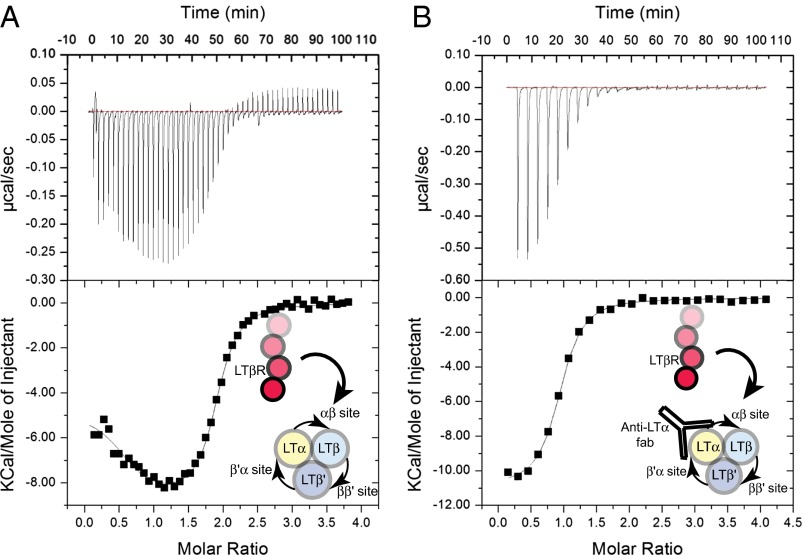

To better understand the requirements for triggering signaling via the LTβR pathway, we used isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) to determine the stoichiometry and affinity of LTα1β2 with LTβR. This analysis confirmed that the heterotrimeric ligand LTα1β2 binds to two LTβR molecules, consistent with previous results (27). Fitting of the ITC data to a binding curve suggested each copy of LTβR binds LTα1β2 with one apparent high-affinity site (12 nM) and a lower affinity site (170 nM) (Fig. 2A and Table 1). Titration of LTβR into a preformed complex of LTα1β2–anti-LTα Fab revealed a single available binding site with an affinity of 250 nM (Fig. 2B and Table 1), implying that the monomer–monomer interface between the two LTβ molecules (the β–β site) is the lower affinity site for LTβR. As a control, we also generated soluble, homotrimeric LTβ3, which is not found in vivo on the surface of cells (28, 29) but which allowed us to probe the β–β site, as it has three equivalent sites, and characterized its interactions with LTβR. Like LIGHT (27), homotrimeric LTβ3 also bound only two copies of LTβR binding sites but with equal affinity (3 μM) (Fig. S2 and Table 1).

Fig. 2.

Representative ITC curves suggest two LTβR binding sites in LTα1β2 with distinct affinities. (A) LTβR (200 μM) was titrated into LTα1β2 (10 μM). Upper, baseline-corrected power-versus-time plot for the titration. Lower, integrated heats and molar ratios of LTβR binding to LTα1β2. The data were corrected for heats of dilution and fit to a two-site binding model. (B) LTβR (150 μM) was titrated into LTα1β2–anti-LTα Fab complex (7 μM). Upper, baseline-corrected power-versus-time plot for the titration. Lower, integrated heats and molar ratios of LTβR binding to LTα1β2. The data were corrected for heats of dilution and fit to a one-site binding model. The higher affinity site is blocked as a result of anti–LTα-Fab bound to LTα1β2. Illustrations next to curves depict the reactions with LTβR being added to either LTα1β2 (A) or LTα1β2–anti-LTα Fab complex (B) to measure heats of reaction against moles of LTβR added. See SI Materials and Methods for details of experimental setup, curve fitting, and data analysis.

Table 1.

LTβR binding sites and their affinities for WT and single-chain variants of LTα1β2

| Species | LTβR binding sites | Kd, nM, ITC | Kd, nM, BI |

| WT LTα1β2 | 2 (αβ, ββ’) | 11.3 ± 7.0 | NA |

| 172 ± 34 | |||

| WT LTα1β2–anti-LTα | 1 (ββ’) | 250 ± 25 | NA |

| WT LTβ3 | 2 (ββ) | 3,300 ± 600 | NA |

| Single-chain variant A | 2 (αβ, ββ’) | 6.0 ± 4.8 | NA |

| 227 ± 82 | |||

| Single-chain variant C | 1 (ββ’) | 342 ± 56 | 380 ± 92 |

| Single-chain variant F | 1 (αβ) | NA | 163 ± 29 |

BI, Biolayer Interferometry.

Crystal Structure of LTα1β2–LTβR–Anti-LTα Complex Elucidates Asymmetric Interactions.

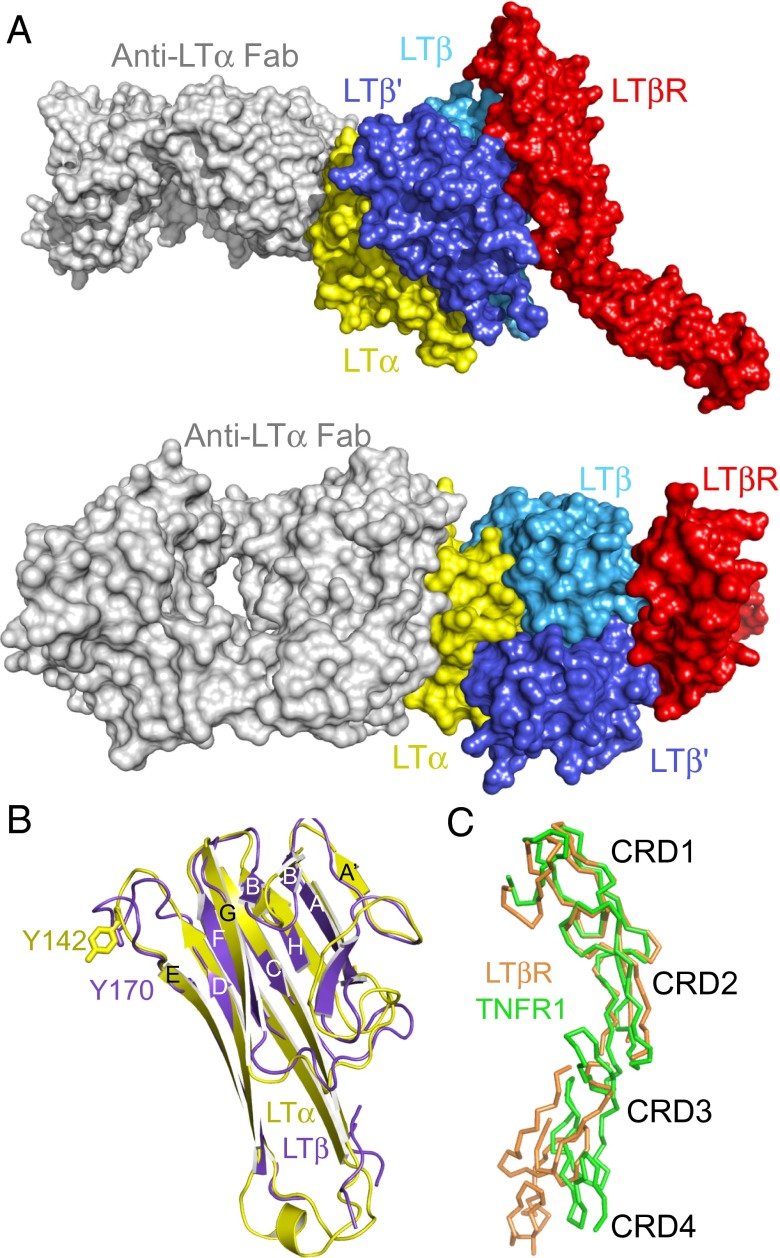

To characterize the LTα1β2–LTβR interaction, we crystallized and determined the structure of the LTα1β2–LTβR–anti-LTα Fab complex at 3.6 Å (Fig. 3A and Table S1). The asymmetric unit contains two LTα1β2–LTβR–anti-LTα Fab complex units. Only ∼50% of one of the LTβR molecules is ordered, whereas ∼85% of the other LTβR is ordered. As a part of this complex, we present the first report of the structures of LTβ and LTβR. LTα1β2 is similar in architecture to LTα3 and other homotrimeric TNF-like ligands (Fig. 3A). One anti–LTα-Fab molecule is bound to the single LTα protomer in the complex recapitulating the interaction observed in the LTα3–(anti–LTα-Fab)3 complex. On the opposite side of the heterotrimer from the anti-LTα epitope, one molecule of LTβR is bound in the groove formed by the two molecules of LTβ.

Fig. 3.

Structure of LTα1β2–LTβR bound to anti-LTα reveals low-affinity LTβR binding site. (A) Crystal structure of the LTα1β2–anti-LTα-LTβR complex. Anti-LTα (gray) is bound to LTα as expected from the structure of LTα3 bound to anti-LTα Fab as shown in Fig. 1. LTβR (red) is bound at the β–β’ interface (light and dark blue). Side view (Upper), top-down view (Lower). (B) Structural alignment (secondary structure) of LTα (yellow, PDB ID code 1TNR) and LTβ (purple, current work) revealing overall similarities. Tyrosine residues in the DE-loops of either molecule important for receptor binding are shown. (C) Structural alignment (Cα trace) of TNFR1 (green, PDB ID code 1TNR) and LTβR (orange, current work) reveals significant overlap between CRD1 and CRD2 regions.

Superposition of LTβ onto LTα (Fig. 3B) revealed that the protomers are generally similar with a root mean square deviation (rsmd) of 0.8 Å on equivalent Cα atoms. The side chain of Y142 (LTα), which makes a conserved hydrophobic interaction with TNFR1 (15, 23), overlaps well with the corresponding residue in LTβ (Y170). The four amino acid insert (165RAGG168) in this loop compared with LTα lacks well-resolved density. The DE-loop is poorly ordered in the other copy of LTβ in the complex. The architecture of LTβR is similar to TNFR1, wherein CRD1 and CRD2 of LTβR superimpose on the corresponding regions of TNFR1 [Protein Data Bank (PDB) ID code 1TNR] with an rmsd of 1.4 Å (Fig. 3C). As in other multidomain TNFRSF members, the orientation of CRD3 with respect to CRD2 is variable, and this region of LTβR assumes a different orientation than in TNFR1.

The interface between LTβR and LTβ–LTβ’ is primarily formed by CRD2 from LTβR with minimal additional contacts from CRD1 (Fig. S3A). This interface is predominantly polar with only modest hydrophobic contacts. In particular, conserved residues K108, E109, and R142 in LTβ’ form complementary electrostatic interactions with residues E85, R102, and D105, respectively, from LTβR CRD2 (Fig. S3C). Unexpectedly, neither LTβ promoter contacts LTβR CRD3. Consequently, CRD3 is disordered in one copy of the complex in the crystallographic asymmetric unit and marginally ordered in the second copy of the complex as might be expected due to the lack of stabilizing interactions with ligand. In contrast, when bound to TNFR1 (PDB ID code 1TNR), LTα makes extensive interactions with CRD2 and CRD3 (Fig. S3B).

Compared with other multidomain TNFRSF members, whose affinities for their respective ligands are typically in the low nanomolar range, the lack of interaction with CRD3 may contribute to the relatively weak affinity of the LTβ–LTβ’ site for LTβR. This dependence on CRD1 and CRD2 is similar to the interface formed between TL1A and DcR3 (18). A structure-based sequence alignment between LTβ and LTα reveals significant differences between them, with only 20% identity and 33% similarity in the residues directly involved in LTβR binding at the LTβ–LTβ’ interface (Fig. S3D). The higher affinity site in LTα1β2 may make additional interactions with CRD3, as significantly different residues are expected on the LTα side of the interface in either the α–β or the β’–α sites compared with the β–β’ site. Sequence alignment of LIGHT with LTβ (Fig. S3D) reveals that the residues in LTβ that are responsible for electrostatic interactions with LTβR (K108, E109, R142) are not conserved in LIGHT.

Identification of the Second Receptor-Binding Site.

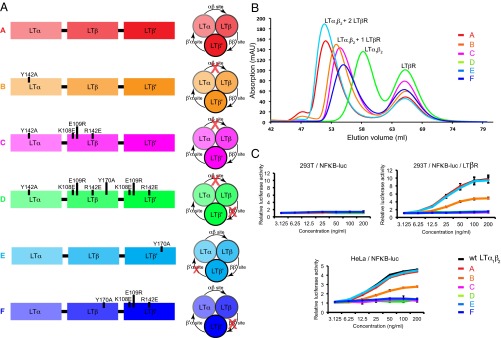

To interrogate the receptor-binding sites, we designed a single-chain LTα1β2 protein comprised of LTα followed by two copies of LTβ with short intervening linkers between each protomer, allowing for site-directed mutagenesis of specific interfaces at each possible receptor-binding site (Fig. 4A and Fig. S4 A and B). This single-chain variant allowed us to selectively alter receptor-binding sites in LTα1β2 by altering the residues involved in the electrostatic interaction in the LTβ–LTβR interface and the conserved tyrosine residue in the DE-loop of LTα or LTβ (Fig. 4A and Fig. S4C). Using this strategy, six variants were synthesized (Fig. 4A and Table S2). We assessed the ability of each variant to form a stable complex with LTβR using size exclusion chromatography. The results (Fig. 4B) show that, as expected, the variant A behaves similarly to LTα1β2 and binds two LTβR molecules. The same experiment with LTα–LTβ site deficient variants B and C suggests diminished binding to one LTβR molecule in B and complete loss of binding to one LTβR molecule in C. The variant targeting both α–β and β–β’ sites, D, does not bind LTβR in this assay. Variant E, which targets the β’–α site, behaves identically to variant A, suggesting that the β’–α site is not required for interactions with LTβR. Variant F, which targets the β–β’ site, also shows binding to one LTβR molecule.

Fig. 4.

The α–β and β–β’ binding sites are essential for signaling. (A) A representation of the various single-chain variants of LTα1β2 generated to identify the high-affinity LTβR binding site in LTα1β2. Receptor-binding sites affected in each variant are shown on the right. (B) Size exclusion chromatography on the complexes of LTβR with the single-chain LTα1β2 variants suggests that charge reversal substitutions in the α–β and β–β sites disrupt receptor binding as predicted. The data also suggest that the α–β site, not the β’ –α site, is the higher affinity binding site for LTβR. (C) Binding of LTβR to both the α–β and β–β’ sites are required for LTβR signaling. 293T/NF-κB-luc cells (Upper Left), 293T/NF-κB-luc transfected with LTβR (Upper Right), or HeLa/NF-κB-luc cells (Lower) were stimulated with increasing concentrations of WT LTα1β2 protein or single-chain variants of LTα1β2. Luciferase activity induced by stimulation is shown relative to activity in unstimulated cells. Data are shown as mean ± SD of two independent experiments.

These experiments indicated LTα1β2 binds two receptors, one at the α–β site and one at the β–β’ site. To verify our conclusion, we used ITC to measure affinities and stoichiometry for the single-chain “wild-type” variant A and the α–β site targeted variant C (Fig. S4D and Table 1). Consistent with the chromatography data, variant A binds to two LTβR molecules with affinities similar to the WT LTα1β2, whereas C, with an impaired LTα–LTβ interface, binds to only one LTβR with lower affinity. These data unequivocally identify the LTβR binding sites as the LTα–LTβ and LTβ–LTβ’ interfaces.

To further confirm the affinity measurements in light of the complexity of the ITC data corresponding to WT LTα1β2 and variant A, we used an orthogonal technique, Biolayer Interferometry (BI), to measure affinities of the α–β site and the β–β’ site individually using variants C and F (Fig. S4E and Table 1). These data confirm different affinities for the two sites (163 nM, α–β site; 380 nM, β–β’ site). Although the value determined for the lower affinity site is consistently ∼200–300 nM across several experimental approaches, the affinity of the other receptor-binding site is likely overestimated by ITC due to the atypical nonsigmoidal nature of the data. Thus, the difference in the affinity between the two sites is likely closer to ∼twofold than the ∼10 fold suggested by the ITC data.

Interactions with Two Copies of LTβR Are Required for Cellular/Functional Signaling.

To verify the functional importance of each receptor-binding site for signaling, we assessed WT and single-chain variants of LTα1β2 in two cell-based NF-κB activity assays (Fig. 4C and Fig. S4E). HeLa/NF-κB-luc cells, which express endogenous LTβR, were stimulated with increasing concentrations of WT LTα1β2 protein or the single-chain LTα1β2 variants as indicated (Fig. 4C, Left). The functional signaling data were in agreement with the binding data. Signaling by single-chain WT variant A and the β’–α-deficient variant E appears similar to signaling by the soluble three-chain heterotrimer WT–LTα1β2. This result indicated that the alterations to the β’–α site did not affect signaling. In contrast, targeting the α–β site with the Y142A substitution in LTα (variant B) decreases luciferase activity twofold. Variant C, which carries more profound changes at the α–β site, and variant F, which has the β–β’ site disrupted, are incapable of signaling through LTβR. Similarly, single-chain variant D with mutations at both the α–β and β–β’ sites is also incapable of inducing signal transduction via LTβR. To further confirm that the NF-κB signaling observed was fully dependent on LTβR, we used the 293T/NF-κB-luc cells that lack LTβR, and transfected them with LTβR (293T/NF-κB-luc/LTβR), and compared the activity of WT and single-chain LTα1β2 variants. 293T/NF-κBluc/LTβR cells responded comparably to the single-chain LTα1β2 variants as HeLa/NF-κB-luc cells, whereas 293T/NF-κB-luc cells were refractory to activation (Fig. 4C), indicating that the downstream NF-κB activation we observe was dependent on LTβR.

Collectively our biochemical and cellular data show decreased bioactivity for LTα1β2 variants with impaired LTβR binding capacity at either the α–β or β–β’ clefts, whereas mutations targeting the β’–α site had no effect on LTβR binding or signaling. Thus, the binding of each molecule of LTα1β2 to two copies of LTβR is necessary and sufficient to activate the NF-κB pathway.

Discussion

For typical TNFRSF members, signaling is driven by receptor trimerization and higher order clustering induced by binding the homotrimeric ligands such as TNFα3 or LTα3. Disruption of signaling by ligand blockade has been efficacious in preventing TNF-mediated pathology (30). The unique asymmetric architecture of LTα1β2 suggested it might induce LTβR receptor signaling differently from canonical TNFSF members and that blocking ligand-induced signaling with a single antibody could be challenging. Notably, an anti-LTα antibody was generated that blocked signaling induced by both LTα3 and LTα1β2, although it did not fully prevent LTα1β2 from binding to surface-expressed LTβR(11). We used anti-LTα as a tool to characterize the mechanism of signaling by the LTα1β2–LTβR complex, revealing that LTα1β2 possesses two LTβR binding sites: a lower affinity binding site at the LTβ–LTβ’ interface and a higher affinity binding site at the LTα–LTβ interface. Using anti-LTα and site-directed mutagenesis, we show that disruption of receptor binding at either of these sites is sufficient to prevent signal transduction via the NF-κB pathway.

Both ligands for LTβR, LIGHT and LTα1β2, are unusual in the TNFSF in that they bind only two receptor molecules rather than three, as typically observed in the superfamily. Although the structure of homotrimeric LIGHT (PDB ID code 4EN0) is not inconsistent with the biochemical evidence that LIGHT binds only two LTβR molecules (27), it does not reveal a compelling structural driver for this stoichiometry. Interestingly, the structure of LIGHT bound to DcR3 (PDB ID code 4J6G) reveals a 3:3 interaction. In contrast to homotrimeric LIGHT, in a heterotrimer such as LTα1β2, each receptor-binding site is formed by the juxtaposition of residues from LTα or LTβ promoters and is inherently distinct. Thus, each receptor-binding site in LTα1β2 has evolved varying affinities for the same receptor or, as is the case of the LTβ’–LTα interface, no receptor binding. The relative lack of conservation of the LTβR binding residues in LTα1β2 compared with LIGHT (Fig. S3D) suggests that they have evolved by convergent evolution, although there may have been an ancestral homotrimeric LTβ3. The existence of heterotrimers in distantly related TNF homologs such as the adiponectin C1q (31) and collagen X NC1 domains (32) suggests that the plasticity of having distinct sites in a pseudo-threefold symmetric molecule is advantageous in some evolutionary contexts.

In most TNFRSF pathways, receptor trimerization or even high-order oligomerization is the trigger for robust intracellular signaling. For instance, Fas and ectodysplasin A (EDA) receptor (EDAR) receptors require ligands that are either cell bound (FasL) or have multimerization motifs (EDA) to fully elicit downstream signaling (33–35). In other contexts, such as apoptosis triggered by the death receptors, a requirement for trimerization or higher order clustering may lower the chances of inadvertently triggering an irreversible and fatal pathway. The structure of the intracellular Fas–FADD complex (36) revealed unexpected additional complexity in TNFRSF signaling as the stoichiometry and symmetry of the intracellular signaling components (5-Fas–5-FADD) differ from those of the extracellular ligand–receptor interaction.

Formation of ligand-induced higher order assemblies in cells can be a very cooperative process, leading to a “digital” on-switch for some systems (13). Our results are consistent with this model and imply that the trigger for the LTβR-mediated “on-switch” is more sensitive than for other members of the TNFRSF. In this case, dimeric clustering of the receptor is sufficient to nucleate intracellular signal transduction as opposed to trimeric or higher order signaling as in other TNF family members. It is possible that dimeric clustering of other TNFRSF members may be sufficient for signaling, as suggested by the observation that bivalent antibodies can act as pathway agonists (2, 30). This hypothesis is difficult to test in the absence of single-chain variants of the ligands in which individual receptor-binding sites can be disrupted. More generally, signaling for TNFRSF members is a consequence not just of the ligand–receptor interactions but also of the many downstream intracellular components as well as the local concentration of receptors and of the propensity of the receptors for clustering in the absence of ligand. In the case of LTβR, the cooperativity of the intracellular assemblies appears to compensate for decreased valency of the extracellular trigger. In conclusion, LTβR signaling represents one extreme of the TNFRSF in which minimal extracellular ligand-induced clustering is sufficient to engage and propagate the intracellular signal. This may reflect either an evolutionary tolerance for higher false positive rates in LTβR signaling or an advantage to triggering lymphoid development, tumor immunity, or LTβR-driven inflammation at lower receptor or ligand concentrations.

Materials and Methods

Protein Expression, Purification, and Structure Determination.

LTα, LTβ, LTβR, and single-chain variants of LTα1β2 expressed in insect cells using baculovirus vector and were purified from the growth media using column chromatrography. Anti-LTα fab was obtained by LysC cleavage from the fully humanized antibody MLTΑ3698A. Protein complexes LTα3–anti-LTα Fab and LTα1β2–LTβR–anti-LTα Fab were obtained by mixing purified proteins followed by size exclusion chromatography. Crystals of both complexes were obtained by vapor diffusion, and data were collected at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory and Stanford Synchronized Radiation Laboratory. Molecular replacement using relevant models followed by positional and thermal factor refinement resulted in the final structures. Coordinates and structure factors for the LTα3–anti-LTα Fab and the LTα1β2–LTβR–anti-LTα Fab complexes have been deposited with PDB (PDB ID codes 4MXV and 4MXW, respectively).

Stoichiometry and Affinity Assays.

ITC experiments were performed using instruments from MicroCal. Binding isotherms were analyzed using nonlinear least-squares fitting of the data to one-site or two-site models. Biolayer Interferometry experiments were performed using the Octet RED384 system.

Cellular Assays.

Flow cytometry was performed using HEK 293T-LT-αβ cells. Luciferase activity was measured using the Promega Luciferase Assay System. LTβR activation of NF-κB by single-chain variants of LTα1β2 was determined using HeLa/NF-κB-luc cells and HEK 293T cells stably transfected with a standard NF-κB-luciferase reporter. See SI Materials and Methods for details.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the anti-LTα team and Racquel Corpuz for reagents and Christine Tam and colleagues for cloning the single-chain variant constructs of LTα1β2 and for advice on baculovirus expression. The Stanford Synchronized Radiation Laboratory, the Advanced Light Source, and the Berkeley Center for Structural Biology are supported by the Department of Energy, the National Institutes of Health, and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: All authors are employees of Genentech, Inc.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data deposition: The atomic coordinates and structure factors have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, www.pdb.org (PDB ID codes 4MXV and 4MXW).

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1310838110/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Browning JL, et al. Preparation and characterization of soluble recombinant heterotrimeric complexes of human lymphotoxins alpha and beta. J Biol Chem. 1996;271(15):8618–8626. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.15.8618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ware CF. Network communications: Lymphotoxins, LIGHT, and TNF. Annu Rev Immunol. 2005;23:787–819. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.23.021704.115719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gommerman JL, Browning JL. Lymphotoxin/light, lymphoid microenvironments and autoimmune disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2003;3(8):642–655. doi: 10.1038/nri1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tumanov AV, Kuprash DV, Nedospasov SA. The role of lymphotoxin in development and maintenance of secondary lymphoid tissues. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2003;14(3-4):275–288. doi: 10.1016/s1359-6101(03)00026-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grogan JL, Ouyang WJ. A role for Th17 cells in the regulation of tertiary lymphoid follicles. Eur J Immunol. 2012;42(9):2255–2262. doi: 10.1002/eji.201242656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Browning JL, et al. Characterization of lymphotoxin-alpha beta complexes on the surface of mouse lymphocytes. J Immunol. 1997;159(7):3288–3298. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chiang EY, et al. Targeted depletion of lymphotoxin-alpha-expressing TH1 and TH17 cells inhibits autoimmune disease. Nat Med. 2009;15(7):766–773. doi: 10.1038/nm.1984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gramaglia I, Mauri DN, Miner KT, Ware CF, Croft M. Lymphotoxin alphabeta is expressed on recently activated naive and Th1-like CD4 cells but is down-regulated by IL-4 during Th2 differentiation. J Immunol. 1999;162(3):1333–1338. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ware CF, Crowe PD, Grayson MH, Androlewicz MJ, Browning JL. Expression of surface lymphotoxin and tumor necrosis factor on activated T, B, and natural killer cells. J Immunol. 1992;149(12):3881–3888. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Browning JL. Inhibition of the lymphotoxin pathway as a therapy for autoimmune disease. Immunol Rev. 2008;223:202–220. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00633.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chiang EY, et al. In vivo depletion of lymphotoxin-alpha expressing lymphocytes inhibits xenogeneic graft-versus-host-disease. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(3):e33106. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0033106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li C, et al. Structurally distinct recognition motifs in lymphotoxin-beta receptor and CD40 for tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor (TRAF)-mediated signaling. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(50):50523–50529. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309381200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wu H. Higher-order assemblies in a new paradigm of signal transduction. Cell. 2013;153(2):287–292. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jones EY, Stuart DI, Walker NPC. Structure of tumour necrosis factor. Nature. 1989;338(6212):225–228. doi: 10.1038/338225a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Banner DW, et al. Crystal structure of the soluble human 55 kd TNF receptor-human TNF beta complex: Implications for TNF receptor activation. Cell. 1993;73(3):431–445. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90132-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mongkolsapaya J, et al. Structure of the TRAIL-DR5 complex reveals mechanisms conferring specificity in apoptotic initiation. Nat Struct Biol. 1999;6(11):1048–1053. doi: 10.1038/14935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nelson CA, Warren JT, Wang MWH, Teitelbaum SL, Fremont DH. RANKL employs distinct binding modes to engage RANK and the osteoprotegerin decoy receptor. Structure. 2012;20(11):1971–1982. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2012.08.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhan CY, et al. Decoy strategies: The structure of TL1A:DcR3 complex. Structure. 2011;19(2):162–171. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2010.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.An HJ, et al. Crystallographic and mutational analysis of the CD40-CD154 complex and its implications for receptor activation. J Biol Chem. 2011;286(13):11226–11235. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.208215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Compaan DM, Hymowitz SG. The crystal structure of the costimulatory OX40-OX40L complex. Structure. 2006;14(8):1321–1330. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2006.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mukai Y, et al. Solution of the structure of the TNF-TNFR2 complex. Sci Signal. 2010;3(148):ra83. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2000954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ta HM, et al. Structure-based development of a receptor activator of nuclear factor-kappaB ligand (RANKL) inhibitor peptide and molecular basis for osteopetrosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(47):20281–20286. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1011686107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hymowitz SG, et al. Triggering cell death: The crystal structure of Apo2L/TRAIL in a complex with death receptor 5. Mol Cell. 1999;4(4):563–571. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80207-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Karpusas M, et al. Structure of CD40 ligand in complex with the Fab fragment of a neutralizing humanized antibody. Structure. 2001;9(4):321–329. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(01)00590-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liang S, et al. Structural basis for treating tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα)-associated diseases with the therapeutic antibody infliximab. J Biol Chem. 2013;288(19):13799–13807. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.433961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Goh CR, Loh CS, Porter AG. Aspartic acid 50 and tyrosine 108 are essential for receptor binding and cytotoxic activity of tumour necrosis factor beta (lymphotoxin) Protein Eng. 1991;4(7):785–791. doi: 10.1093/protein/4.7.785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Eldredge J, et al. Stoichiometry of LTbetaR binding to LIGHT. Biochemistry. 2006;45(33):10117–10128. doi: 10.1021/bi060210+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Browning JL, et al. Lymphotoxin beta, a novel member of the TNF family that forms a heteromeric complex with lymphotoxin on the cell surface. Cell. 1993;72(6):847–856. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90574-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Browning JL, et al. Characterization of surface lymphotoxin forms. Use of specific monoclonal antibodies and soluble receptors. J Immunol. 1995;154(1):33–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ware CF. Protein therapeutics targeted at the TNF superfamily. Adv Pharmacol. 2013;66:51–80. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-404717-4.00002-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shapiro L, Scherer PE. The crystal structure of a complement-1q family protein suggests an evolutionary link to tumor necrosis factor. Curr Biol. 1998;8(6):335–338. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(98)70133-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bogin O, et al. Insight into Schmid metaphyseal chondrodysplasia from the crystal structure of the collagen X NC1 domain trimer. Structure. 2002;10(2):165–173. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(02)00697-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schneider P, et al. Mutations leading to X-linked hypohidrotic ectodermal dysplasia affect three major functional domains in the tumor necrosis factor family member ectodysplasin-A. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(22):18819–18827. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M101280200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schneider P, et al. Conversion of membrane-bound Fas(CD95) ligand to its soluble form is associated with downregulation of its proapoptotic activity and loss of liver toxicity. J Exp Med. 1998;187(8):1205–1213. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.8.1205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tanaka M, Itai T, Adachi M, Nagata S. Downregulation of Fas ligand by shedding. Nat Med. 1998;4(1):31–36. doi: 10.1038/nm0198-031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang L, et al. The Fas-FADD death domain complex structure reveals the basis of DISC assembly and disease mutations. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2010;17(11):1324–1329. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.