Abstract

Maternal smoking and depressive symptoms are independently linked to poor child health outcomes. However, little is known about factors that may predict maternal depressive symptoms among low-income, African American maternal smokers - an understudied population with children known to have increased morbidity and mortality risks. The objective of this study was to test the hypothesis that secondhand smoke exposure (SHSe)-related pediatric sick visits are associated with significant maternal depressive symptoms among low-income, African American maternal smokers in the context of other depression-related factors. Prior to randomization in a behavioral counseling trial to reduce child SHSe, 307 maternal smokers in Philadelphia completed the CES-D and questionnaires measuring stressful events, nicotine dependence, social support, child health and demographics. CES-D was dichotomized at the clinical cutoff to differentiate mothers with significant vs. low depressive symptoms. Results from direct entry logistic regression demonstrated that maternal smokers reporting more than one SHSe-related sick visit (OR 1.38, p<.001), greater perceived life stress (OR 1.05, p<.001) and less social support (OR 0.82, p<.001) within the last 3 months were more likely to report significant depressive symptoms than mothers with fewer clinic visits, less stress, and greater social support. These results suggest opportunities for future hypothesis-driven evaluation, and exploration of intervention strategies in pediatric primary care. Maternal depression, smoking and child illness may present as a reciprocally-determined phenomenon that points to the potential utility of treating one chronic maternal condition to facilitate change in the other chronic condition, regardless of which primary presenting problem is addressed. Future longitudinal research could attempt to confirm this hypothesis.

Keywords: Maternal depression, depressive symptoms, smoking, child health, low-income, minority

Introduction

“Maternal depression” refers to a variety of depressive symptoms that can affect women during child-rearing years (Wisner, Parry, & Piontek, 2002). More than 19 million adults in the U.S. suffer from depression, which has become a leading cause of disability and is attributed to approximately two-thirds of suicides each year (USDHHS, 2011). Up to 12% of women experience postpartum depression (although twice that many may experience significant depressive symptoms,) and depression risk increases dramatically among women with young children and more than one child (Coiro, 2001; McLennan & Offord, 2002). African Americans have nearly double the rate of depression than Caucasians (Pratt & Brody, 2008), and women who are poor, on welfare, less educated, and unemployed are more likely to experience depression than other socio-economic groups (Pratt, 2008; USDHHS, 2011). Moreover, many African American and underserved women who suffer from significant depressive symptoms either remain undiagnosed or untreated; therefore, improving assessment and treatment of maternal depression in this population remains a public health priority (USDHHS, 2011).

Nicotine dependence and significant depressive symptoms often co-occur. Additionally, the association appears to be bi-directional (Chaiton, Cohen, O’Loughlin, & Rehm, 2009; Kendler, et al., 1993; Paperwalla, Levin, Weiner, & Saravay, 2004). Recent studies observed over 40% prevalence of smoking among African Americans who reported significant depressive symptoms (Berg, et al., 2012); and over 75% prevalence of depressive symptoms among female smokers, including a disproportionately higher proportion of African American women with depressive symptoms compared to other racial groups of smokers (Jessup, Dibble, & Cooper, 2012). Consequently, the direction of a potential causal link is still debated, with some researchers postulating that smokers use nicotine to help relieve depressive symptoms (Glassman, et al., 1990), while others suggest that smoking influences physiological changes that result in depressive symptoms (Paperwalla, et al., 2004). Others argue that the expression of both nicotine dependence and significant depressive symptoms result from shared genetic and environmental risk factors (Kendler, et al., 1993). Regardless of the potential causal directionality of the smoking-depressive symptom association, greater depressive symptoms are associated with greater challenges in quitting smoking among women across the lifespan (Husky, Mazure, Paliwal, & McKee, 2008), in particular, during pregnancy and postpartum periods. For example, only about 30% of female smokers quit during pregnancy (Tong, Jones, Dietz, D’Angelo, & Bombard, 2009), and as many as 75% of smokers who quit during their pregnancy relapse to smoking during the postpartum period (Kahn, Certain, & Whitaker, 2002).

Psychosocial factors that relate to maternal depressive symptoms and nicotine dependence overlap with characteristics observed across underserved populations in general: poverty, racial minority status, low education, unemployment, neighborhood disorder, neighborhood-level economic disadvantage, and substance use (O’Hara, 2009). Interactions among these factors create additive risk for maternal depression (Cutrona, et al., 2005). Similar to other racial groups, many African Americans smoke to cope with depressive symptoms (Pederson, Ahluwalia, Harris, & McGrady, 2000); but compared to Caucasian American maternal smokers, underserved African American mothers have particular difficulty quitting smoking and are more likely to relapse to smoking (Severson, Andrews, Lichtenstein, Wall, & Zoref, 1995). Recent data from the Centers for Disease Control suggest that African American smoking rates (21.3%) have risen to comparable levels as Caucasian Americans (22%), with higher rates among underserved populations such as individuals with low education, or living in poverty or deprived neighborhoods (CDC, 2008). Additionally, urban-dwelling and low-income African American children suffer the highest rates and levels of SHSe (Carmichael & Ahluwalia, 2000), and bear greater SHSe-related morbidity and mortality burden than other populations (Ahluwalia, 2002). Thus, low-income African American women are not only more likely to be depressed (Pratt & Brody, 2008; USDHHS, 2011), but they also are more likely to smoke and have children with greater levels of SHSe and SHSe-related illness than the general population of women.

A primary concern regarding maternal nicotine dependence and depressive symptoms is that both syndromes independently and adversely affect child health (O’Hara, 2009). Maternal smoking is considered the primary source of children’s secondhand smoke exposure (SHSe), which has unequivocally been linked to Sudden Infant Death Syndrome, middle-ear infections, lower respiratory infections, asthma onset and severity, dental caries, as well as increased risk for numerous cancers, cardiovascular diseases, and behavioral disorders (Best, 2009; Haberg, et al., 2010; Herrmann, King, & Weitzman, 2008; Kum-Nji, Meloy, & Herrod, 2006; Moon, Gingras, & Erwin, 2002; Richardson, Walker, & Horne, 2009; Tanaka, Miyake, & Sasaki, 2009; Twardella, Bolte, Fromme, Wildner, & von Kries, 2010). Moreover, longitudinal research indicates that the effects of childhood SHSe are not limited to health consequences experienced during childhood. For example, childhood SHSe has been related to adult emphysema, even among children who remain nonsmokers through adolescence and adulthood (Lovasi, et al., 2010). Maternal depressive symptom effects on child health are equally weighty. For example, significant maternal depressive symptoms are linked to childhood asthma (Lim, 2008), child cognitive and language development, emotional problems, and behavioral disorders; (Cox, Puckering, Pound, & Mills, 1987; Sohr-Preston & Scaramella, 2006), as well as non-compliance with children’s medication administration (Leiferman, 2002), and poor health outcomes associated with asthma and respiratory allergies (Turney, 2011). Additionally, children of mothers expressing depressive symptoms are less likely to receive preventive medical and dental care (Turney, 2011).

As comorbid conditions, maternal smoking and depressive symptoms are likely to compound child health risks compared to either presentation alone. Moreover, reciprocal associations between maternal depressive symptoms, smoking, and child health may exist. For example, child health problems may increase and exacerbate maternal depressive symptoms (Shalowitz, et al., 2006) a context that is likely to influence maternal smoking to manage depressive symptoms and ongoing childhood health problems. Such a cycle underscores a key obstacle to smoking behavior change.

Given that pediatric providers have more frequent contact with depressed women and smokers of childbearing age compared to other health professionals (Horwitz, Bell, & Grusky, 2006), there is incredible opportunity for pediatric providers to improve maternal and child health when they identify SHS-exposed children. Pediatric providers acknowledge their responsibility to protect and improve child health by addressing maternal depression and smoking (Pascoe & Stolfi, 2004), and the American Academy of Pediatrics endorses and encourages providers to ask, advise, and refer parents to behavioral health services if parents smoke or present with psychosocial problems that compromise the care of their children. Therefore, improving our understanding of factors that may influence significant depressive symptoms among maternal smokers should improve providers’ ability to assess and advise mothers in a population whose children would benefit most from maternal smoking intervention.

Despite knowledge of factors that differentiate depressed mothers from the general population, little is known about variability in depression risk within underserved populations of smokers, such as low income, urban-dwelling African American mothers. Examining factors that predict significant depressive symptoms in this group is warranted as it would help identify children and families that bear exceptional maternal and child health risks. The purpose of this study was to examine associations among factors hypothesized to increase likelihood of significant maternal depressive symptoms in a sample of underserved, maternal African American smokers. We hypothesized that increased pediatric primary care clinic sick visits, life events stress, and nicotine dependence would predict depression when controlling for other factors known to relate to maternal depression in the general population (e.g., social support, employment status).

Methods

Participants

This study examined 307 African American maternal smokers’ responses to interview assessments administered pre-randomization as part of a larger randomized behavioral counseling trial (Philadelphia FRESH – Family Rules for Establishing Smoke-free Homes) aimed at reducing young children’s SHSe. Participants were recruited from low-income urban neighborhoods in North and West Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, either directly from Women Infant and Care (WIC) and pediatric primary care clinic waiting rooms, or through advertisements in newspapers and on mass transit vehicles serving these underserved communities. We targeted these communities due to estimated smoking prevalence rates among adults (28.9% to 31.2% of adults smoke) - rates that exceed the national average (PDPH, 2009).

Participants who were interested in enrolling in an intervention designed to educate them about ways to reduce their child’s SHSe were screened for eligibility into the larger trial prior to baseline interviews and were eligible if they were at least 18 years old, smoked at least five cigarettes per day, and exposed their child (<4 years old) to at least two cigarettes. Exclusion criteria included current diagnosis or treatment of mood, psychotic, or substance abuse disorder and current pregnancy. 387 African American maternal smokers were eligible for the trial. Consent to participate in the trial was obtained prior to baseline interview data collection following HIPAA regulations and procedures approved by the Institutional Review Board. In addition to the 307 smokers completing baseline assessments, 80 were eligible but did not complete the baseline. (Participants were not retained in the study if repeated attempts to schedule and complete the baseline interview were unsuccessful for four weeks after screening.) After completing all baseline assessments, participants were randomized into the trial.

Measures

All measures in this study were collected via structured telephone screening and in-person assessment interviews prior to randomization to treatment in the parent trial. Screening questions focused on eligibility criteria and socio-demographic characteristics. In-person interviews obtained detailed information about maternal smoking history and current patterns, child SHSe, child health, and the measures described below. These interviews were conducted either in participant homes or in research offices of the Health Behavior Research Clinic by trained graduate students and professional staff. In addition to standardized scales used to test primary trial aims, content valid interview items were constructed by a panel of smoking intervention and public health experts below the 7th grade Flesch-Kinkaid reading level, then tested for content validity via interview to a pilot sample of postpartum smokers. Items with common smoking assessment terminology included oral operational definitions with opportunities for interviewer clarification if queried or suspecting item misinterpretation. Ongoing quality assurance procedures focusing on data collection and entry protocols followed by licensed social worker and Ph.D. student interview staff included (a) audio-taped quality assurance assessment by the principal investigator to ensure data collection integrity, (b) ongoing assessment of participant comprehension of items, (c) double data entry of participant responses to ensure accurate response coding. For this study’s analyses, measures were used as continuous variables unless indicated in the sections below and in tables.

Outcome variable (Depressive symptoms)

Participants reported depressive symptoms using the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D), which is a 20-item self-report instrument with adequate test-retest reliability (r=.57). It correlates with clinical measures of depression severity, with a score of 16 or greater indicating likelihood of depressive disorder (Radloff, 1977). The CES-D has been used in a variety of studies comparing ethnic differences in depressive symptom presentation and is a reliable measure among African Americans (Roberts, 1980). Participant CES-D scores were dichotomized such that 0–15 were re-coded as 0 (low depressive symptoms) and >15 were re-coded as 1 (significant depressive symptoms).

Covariates

Pediatric clinic sick visits

The number of pediatric sick visits within the 3 months prior to baseline was calculated as the total number of times the child was taken to a pediatrician for SHSe-related illnesses (e.g., cold, ear infections, bronchitis, asthma, etc.). We excluded well child visits and sick visits related to injury or elective outpatient procedures. Sick visits were dichotomized such that 0 or 1 visit was coded as 0, and more than 1 visit was coded as 1.

Nicotine Dependence

Due to the associations between smoking and depressive symptoms in the general population of women, nicotine dependence level was measured using the Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence (FTND). This is a 6-item questionnaire and has adequate internal consistency (alpha = .64) and high test-retest reliability (r =.88). Continuous FTND scores were used in the analyses.

Life events stress

Participants identified stressful life events experienced within the last 3 months along with their perceived level of stress to each identified event on a 4-point Likert scale (0 = did not occur/or not at all stressful to 3 = extremely stressful) on a survey containing 90 items across nine categories if events related to school, work, family and intimate relationships, child and care giving responsibilities, housing and living conditions, crime and legal matters, finances, social activities, and health. This instrument was constructed by a panel of five smoking intervention and public health experts and tested for content validity via structured interview to a pilot sample of low income maternal smokers in the target population. Internal consistency for the measure was good (α = .86). Participants’ mean stress rating across all 90 items was used in the analysis.

Social support

The Interpersonal Support Evaluation List (ISEL) was used to measure social support (Cohen, Mermelstein, Kamarck, & Hoberman, 1985). Cohen and colleagues reported good overall test-retest reliability with reliability coefficients averaging around .87 and adequate concurrent and discriminant validities (r = .46 and r = −.64). The overall score, which represents general social support, was used as a continuous measure in the analysis.

Number of illness symptoms present

Total number of symptoms baby presented in the past 2 weeks was defined as a total of the maternal-reported signs of illness (e.g., runny nose, stuffy nose, rattling in the chest, fever, coughing, and/or wheezing).

Number of sick days

Total number of sick days was the number of days the child was sick with each of the symptoms mentioned above during the past 2 weeks.

Child age was included as a proxy variable to identify postpartum mothers, thus accounting for maternal depressive symptoms attributable to the postpartum period in the analysis.

Maternal education was dummy coded as 0= less than high school graduate and 1= high school graduate or beyond high school education.

Marital status was coded as being 0=single and 1=married or living with a partner.

Employment status was coded as 0=not employed and 1=employed respectively.

Analysis

Prior to analyses, data were summarized, screened for errors, checked for outliers. We examined demographic factors for interrelations among covariates in order to reduce multi-colinearity. We used direct entry logistic regression to explore hypothesized predictors of maternal depressive symptoms. All analyses were conducted using SPSS v18 software.

Results

Sample characteristics

Participants reported a mean CES-D score of 18.87 (sd = 10.40), with nearly 60% of mothers scoring above the clinical cut-off for depression. Participants had a mean age of 29.8 years (SD = 7.89), and were moderate-to-heavy smokers: reporting an average of 11.74 (SD = 6.22) cigarettes smoked per day with a mean daily smoking history of 11.55 (SD = 7.44) years. Mothers were mostly single (81.8%), unemployed (67.4%), and had a SHS-exposed child averaging 18.9 (sd = 14.86) months old. Most participants (67.8%) reported earning less than $15,000 annually and only 44% achieved a high school degree or greater education. Our sample is comparable to the larger, general population living in low income communities in North and West Philadelphia, Pennsylvania targeted for recruitment into the parent trial. For example, Philadelphia has one of the highest poverty rates (25%) among U.S. cities, with 52.7% of children raised by one parent (with the vast majority of these households being female run) (U.S Census Bureau, 2010). Data from six health centers that serve these communities suggest that, in the general population, 31.5% of families live below poverty level, 11.4% have no insurance, 28.5% of adults smoke, and 14.4% of adults have current or prior mental health problems (PDPH, 2009). Table 1 displays other relevant psychosocial and smoking variables used in analyses reported below.

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics (n = 307)

| Distributional Characteristics | ||

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Variable | Mean | SD |

| Baseline CES-D Score | 18.87 | 10.41 |

| Baseline FTND Score | 4.66 | 1.79 |

| Baseline ISEL Score | 36.75 | 6.49 |

| Total months smoked daily lifetime | 138.66 | 89.28 |

| Average number of cigarettes per day | 11.74 | 6.22 |

| Total number of sick visits, last 3 months | 1.07 | 1.76 |

Logistic Regression

Prior to conducting multivariate analyses, we tested bivariate correlations among the covariates to reduce potential multi-colinearity in the subsequent regression model. Income was dropped as a covariate due to its correlation with employment (r =.35, p <.01) and marriage (r =.20, p < .01). Total number of sick days was dropped as a covariate due to its relation to number of symptoms (r =.78, p <.01). Direct entry logistic regression analysis (1 = depression, 0 = no depression) resulted in a statistically significant model (p < .01) that accounted for an estimated 46% of the variance in depressive symptoms. The model in Table 2 suggests that maternal smokers who reported more than one pediatric clinic sick visit, greater perceived life events stress, and less social support within the last 3 months were more likely to be depressed than mothers with fewer clinic visits, less stress, and greater social support.

Table 2.

Logistic regression model predicting maternal smokers’ depression (1= depressed).

| Predictor | Odds Ratio | 95% CI | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||

| *Pediatrician sick visits last 3 months | 1.38 | 1.12 | 1.69 | <.001 |

| Life Events Stress | 1.05 | 1.02 | 1.06 | <.001 |

| General Social Support | .82 | 0.77 | .86 | <.001 |

| Total number of child symptoms | 1.17 | 0.98 | 1.39 | .07 |

| Marital Status | 1.99 | 0.92 | 4.25 | .08 |

| Employment | .59 | 0.31 | 1.10 | .10 |

| Child age | 1.02 | 0.99 | 1.03 | .15 |

| Nicotine Dependence | .98 | 0.83 | 1.15 | .84 |

| Education | .99 | 0.55 | 1.77 | .98 |

Note: Sick visits were coded as 1 = two or more visits; 0 = less than two visits.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to demonstrate factors associated with significant maternal depressive symptoms in a sample of low-income African American maternal smokers. Results supported the hypothesis, suggesting that more than one SHSe-related sick visit within the last 3 months predicts greater likelihood of significant depressive symptoms (CESD score >15). Greater stress and less social support were other hypothesized factors that demonstrated significant associations with depressive symptom likelihood. Thus, SHSe-related pediatric sick visit utilization, maternal stress and social support may be important factors to consider in understanding the presentation of maternal depressive symptoms in underserved populations of smokers. Similar maternal depression–child health associations exist in broader populations. For example, the increased burden of attending medical visits, missing work because of such visits, transportation barriers, and childcare concerns may increase stress-related maternal depressive symptoms in the general population (Siefert, Finlayson, Williams, Delva, & Ismail, 2007). Moreover, the influence of health service utilization on depressive symptoms is likely to be specific to sick visits and poor child health, not frequent well-child visits (Mandl, Tronick, Brennan, Alpert, & Homer, 1999).

This sample demonstrated a high prevalence of significant depression symptoms. This evidence is consistent with previous research among similar populations known to have increased risk for depression compared to the wider U.S. population (Husky et al, 2008; Pederson et al, 2000; Pratt et al, 2008). For example, in a previous study of 1,602 single mothers with children between three and six and one-half years old, 49% of the mothers had high levels of depressive symptoms as measured by the CES-D (Rosman and Yoshikawa, 2001). Another study among single mothers suggests that greater stress and less social support account for much of the association between single status and maternal depression (Cairney, Boyle, Offord & Racine, 2003) - factors that also show significant associations with depressive symptoms in our sample of smokers.

FTND scores were not associated with depressive symptoms in the model, as hypothesized. Given that the entire sample included smokers, perhaps the range of FTND scores was too restricted to demonstrate an association in the context of other variables that more clearly have strong associations with depressive symptoms.

Because maternal smokers expose their children to SHS, and greater exposure increases onset and severity of numerous acute illnesses requiring pediatric health services (Best, 2009) that can subsequently affect maternal depressive symptoms, we support the proposition that a bidirectional, reciprocal child health - maternal depression association may exist among maternal smokers. This relationship can be observed when child health problems increase maternal depression risk and exacerbation of maternal depression symptoms (Shalowitz, et al., 2006) and when maternal depression influences child health either directly or indirectly (via maternal smoking.)

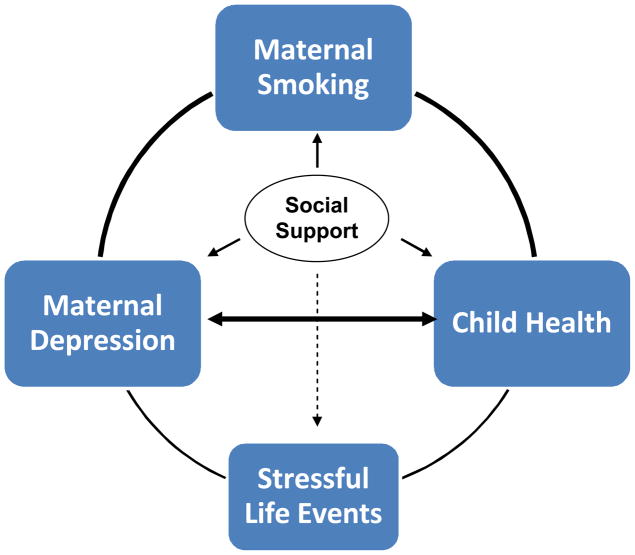

Figure 1 is intended to illustrate the potential reciprocal association within which SHSe-related child illness symptom presentation and utilization of pediatric services increase maternal depressive symptoms which, in turn, contribute to maternal smoking to manage depressive symptoms, and ongoing child health problems. Stress and social support are included in the conceptual model based on our results. These results are consistent with other research examining the effects of social support on stress and depression (Kub, et al., 2009; Logsdon, Birkimer, & Usui, 2000). Moreover, the stress process is known to impact of numerous determinants of health (Cohen, 1988) such that environmental and psychosocial stressors influence physiological, psychological, and behavioral responses (Israel, Farquhar, Schulz, James, & Parker, 2002). Future longitudinal research could test our hypothesized cyclical model.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model of the reciprocal associations among maternal smoking, depression, and child health.

Parents try to quit smoking more than other groups of smokers, but are less successful. In the context of factors measured in our study, stress may influence depressive symptoms among maternal smokers. Stress may also be a direct barrier to smoking cessation and improved child health. Conversely, social support may attenuate maternal depressive symptoms and facilitate behavior change that results in improved stress management, smoking cessation, and reduced child illness. Future research that enhances our understanding of this stress-depression-smoking association could provide important intervention information to pediatric providers.

Depressive symptoms are highly treatable once identified. However, there are many barriers to treatment within underserved and minority communities. For example, only 12% of African American women suffering from depression symptoms seek support or depression treatment (NAMI, 2009). Considering that nearly 60% of mothers in our sample were identified with significant depressive symptoms despite our exclusion of women with diagnosed mood disorder, there may be an extremely high rate of undetected and untreated depression among low-income, minority smokers.

Implications

Our primary finding that more pediatric sick visits is predictive of significant depressive symptoms has the strongest implications for clinical intervention in pediatric treatment settings. Pediatric providers may be in an ideal position to identify symptoms of maternal depression, particularly among maternal smokers. If our results indeed reflect a chronic, multifactorial problem that presents in a cyclical pattern, any one condition or consequence is likely to exacerbate another. Such a predicament represents an opportunity during sick visits whereby addressing one disorder (maternal nicotine dependence or depression) can simultaneously influence the other.

Many participants in our study had either newborns or infants. The postpartum period is already recognized as a timeframe within which pediatric providers maintain vigilance for depressive presentation. However, infancy is also an ideal time for maternal smoking intervention. Pediatric providers should be aware that depressive symptoms have been implicated in lower abstinence and increased risk of smoking relapse (Allen, Prince, & Dietz, 2009; Park, et al., 2009).

Regardless of child age, maternal smoking status could be considered a potential marker for maternal depression. Thus, the determination of positive maternal smoking status during application of standard practice guidelines could prompt depression assessment. Additional rationale for this approach is derived by evidence that pharmaceutical and behavioral interventions shown to be effective for managing depressive symptoms are also effective for smoking cessation. African American women, like women in other racial groups, respond favorably to interventions that include counseling plus antidepressants, such as bupropion (Ahluwalia, 2002; Ahluwalia, Harris, Catley, Okuyemi, & Mayo, 2002). This association may explain why women who quit smoking using antidepressants, such as bupropion, often increase their chances of cessation success (Collins, et al., 2004; Lerman et al., 2004). In this context of maternal smoking with co-morbid depression, such evidence provides further reason for pediatricians to recommend pharmacotherapeutic approaches for maternal smoking cessation to protect their patients from SHSe.

This study does present some limitations to consider when interpreting results. Our study was cross-sectional and correlational, therefore limiting interpretation of causal influence of factors on maternal depression. Another limitation is the extension of findings to populations beyond low income African American maternal smokers. Nonetheless, our results provide important information for guiding future research and interventions that could improve patient care in underserved communities that present overlapping characteristics with this sample.

Conclusion

The results of this study point to the potential utility of conceptualizing comorbid maternal depressive symptoms and nicotine dependence as a reciprocally-determined, cyclical phenomenon. Such associations suggest that a provider could address either maternal smoking or depressive symptoms and affect change in both conditions simultaneously. With the high rates of depression co-morbidity among maternal smokers, and the likely associations between depression and child health, improving the quality of care to children exposed to SHS may not only enhance the health and quality of life of pediatric patients, but may also relieve depressive symptoms and facilitate cessation among maternal smokers. We recognize that challenges in pediatric systems can undermine pediatricians’ identification and management of maternal depression and smoking (Collins, Levin, & Bryant-Stephens, 2007; Heneghan, et al., 2007; Horwitz et al., 2007; Mueller & Collins, 2008; Winickoff, et al., 2008). Therefore, educating providers about factors that predict maternal depression among smokers, and improving referrals systems to facilitate maternal behavioral health care could improve patient care and substantially impact child health outcomes. In most populations and clinics, a standard care smoking cessation approach for parents will likely remain appropriate. However, in high risk populations such as the one in this study, a more intensive, multilevel approach may be necessary (Collins & Ibrahim, 2012). These populations would benefit the most from multilevel interventions with increased intensity over standard in-clinic care because they experience greater economic deprivation, stress, and likelihood of psychiatric comorbidity with nicotine dependence (e.g., depression) – all factors that magnify the challenges inherent to smoking cessation. Future efforts in designing and implementing multilevel strategies could improve integration of services across health systems, such as pediatric primary care and specialized behavioral health services. Such integration could capitalize not only on the frequency of contact and credibility of advice from pediatrics, but also on the intensity of services and support specialized behavioral health practitioners can provide.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute grants CA93756 and CA105183 to BN Collins.

Contributor Information

Bradley N. Collins, Department of Public Health, Health Behavior Research Center, College of Health Professions and Social Work, Temple University.

Uma S. Nair, Department of Public Health, Health Behavior Research Center, College of Health Professions and Social Work, Temple University

Michelle Shwarz, Department of Public Health, Health Behavior Research Center, College of Health Professions and Social Work, Temple University.

Karen Jaffe, Department of Public Health, Health Behavior Research Center, College of Health Professions and Social Work, Temple University.

Jonathan Winickoff, Department of Pediatrics, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA.

References

- Ahluwalia JS, Dang KS, Choi WS, Harris KJ. Smoking behaviors and regular source of health care among African Americans. Preventive Medicine. 2002;34(3):393–396. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2001.1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahluwalia JS, Harris KJ, Catley D, Okuyemi KS, Mayo MS. Sustained-release bupropion for smoking cessation in African Americans: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002;288(4):468–474. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.4.468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen AM, Prince CB, Dietz PM. Postpartum depressive symptoms and smoking relapse. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2009;36(1):9–12. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg CJ, Kirch M, Hooper MW, McAlpine D, An LC, Boudreaux M, et al. Ethnic group differences in the relationship between depressive symptoms and smoking. Ethnicity and Health. 2012;17(1–2):55–69. doi: 10.1080/13557858.2012.654766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Best D. From the American Academy of Pediatrics: Technical report--Secondhand and prenatal tobacco smoke exposure. Pediatrics. 2009;124(5):e1017–1044. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-2120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cairney J, Boyle M, Offord DR, Racine Y. Stress, social support and depression in single and married mothers. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2003;38(8):442–449. doi: 10.1007/s00127-003-0661-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmichael SL, Ahluwalia IB. Correlates of postpartum smoking relapse. Results from the Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS) American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2000;19(3):193–196. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(00)00198-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Cigarette Smoking Among Adults and Trends in Smoking Cessation-United States. MMWR. 2008;58:44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaiton MO, Cohen JE, O’Loughlin J, Rehm J. A systematic review of longitudinal studies on the association between depression and smoking in adolescents. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:356. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-9-356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S. Psychosocial models of the role of social support in the etiology of physical disease. Health Psychology. 1988;7(3):269–297. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.7.3.269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Mermelstein R, Kamarck T, Hoberman H. Measuring the functional components of social support. In: Sarason I, Sarason B, editors. Social support: Theory, research, and applications. Dordrecht, Netherlands: Marinus Nijhoff; 1985. pp. 73–94. [Google Scholar]

- Coiro MJ. Depressive symptoms among women receiving welfare. Women Health. 2001;32(1–2):1–23. doi: 10.1300/J013v32n01_01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins BN, Ibrahim J. Pediatric secondhand smoke exposure: Systematic Multilevel Strategies to Improve Health. Global Heart. 2012;7(2):161–165. doi: 10.1016/j.gheart.2012.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins BN, Levin KP, Bryant-Stephens T. Pediatricians’ practices and attitudes about environmental tobacco smoke and parental smoking. Journal of Pediatrics. 2007;150(5):547–552. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2007.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins BN, Wileyto EP, Patterson F, Rukstalis M, Audrain-McGovern J, Kaufmann V, et al. Gender differences in smoking cessation in a placebo-controlled trial of bupropion with behavioral counseling. Nicotine and Tobacco Research. 2004;6(1):27–37. doi: 10.1080/14622200310001656830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox AD, Puckering C, Pound A, Mills M. The impact of maternal depression in young children. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1987;28(6):917–928. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1987.tb00679.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutrona CE, Russell DW, Brown PA, Clark LA, Hessling RM, Gardner KA. Neighborhood context, personality, and stressful life events as predictors of depression among African American women. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2005;114(1):3–15. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.114.1.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glassman AH, Helzer JE, Covey LS, Cottler LB, Stetner F, Tipp JE, et al. Smoking, smoking cessation, and major depression. Jama. 1990;264(12):1546–1549. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haberg SE, Bentdal YE, London SJ, Kvaerner KJ, Nystad W, Nafstad P. Prenatal and postnatal parental smoking and acute otitis media in early childhood. Acta Pediatrica. 2010;99(1):99–105. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2009.01506.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heneghan AM, Chaudron LH, Storfer-Isser A, Park ER, Kelleher KJ, Stein RE, et al. Factors associated with identification and management of maternal depression by pediatricians. Pediatrics. 2007;119(3):444–454. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-0765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrmann M, King K, Weitzman M. Prenatal tobacco smoke and postnatal secondhand smoke exposure and child neurodevelopment. Current Opinion in Pediatrics. 2008;20(2):184–190. doi: 10.1097/MOP.0b013e3282f56165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horwitz SM, Bell J, Grusky R. The failure of community settings for the identification and treatment of depression in women with young children. In: Fisher WH, editor. Community-Based Mental Health Services for Children and Adolescents With Mental Health Needs: Research in Community and Mental Health. Vol. 14. Oxford, United Kingdom: Elsevier Sciences; 2006. pp. 13–31. [Google Scholar]

- Horwitz SM, Kelleher KJ, Stein RE, Storfer-Isser A, Youngstrom EA, Park ER, et al. Barriers to the identification and management of psychosocial issues in children and maternal depression. Pediatrics. 2007;119(1):e208–218. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Husky MM, Mazure CM, Paliwal P, McKee SA. Gender differences in the comorbidity of smoking behavior and major depression. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2008;93(1–2):176–179. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.07.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Israel BA, Farquhar SA, Schulz AJ, James SA, Parker EA. The relationship between social support, stress, and health among women on Detroit’s East Side. Health Education and Behavior. 2002;29(3):342–360. doi: 10.1177/109019810202900306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jessup MA, Dibble SL, Cooper BA. Smoking and Behavioral Health of Women. Journal of Womens Health (Larchmt) 2012 doi: 10.1089/jwh.2011.2886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahn RS, Certain L, Whitaker RC. A reexamination of smoking before, during, and after pregnancy. American Journal of Public Health. 2002;92(11):1801–1808. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.11.1801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, Neale MC, MacLean CJ, Heath AC, Eaves LJ, Kessler RC. Smoking and major depression. A causal analysis. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1993;50(1):36–43. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1993.01820130038007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kub J, Jennings JM, Donithan M, Walker JM, Land CL, Butz A. Life events, chronic stressors, and depressive symptoms in low-income urban mothers with asthmatic children. Public Health Nursing. 2009;26(4):297–306. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1446.2009.00784.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kum-Nji P, Meloy L, Herrod HG. Environmental tobacco smoke exposure: prevalence and mechanisms of causation of infections in children. Pediatrics. 2006;117(5):1745–1754. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-1886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leiferman J. The effect of maternal depressive symptomatology on maternal behaviors associated with child health. Health Education and Behavior. 2002;29(5):596–607. doi: 10.1177/109019802237027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerman C, Niaura R, Collins BN, Wileyto P, Audrain-McGovern J, Pinto A, et al. Effect of bupropion on depression symptoms in a smoking cessation clinical trial. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2004;18(4):362–366. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.18.4.362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim J, Wood BL, Miller BD. Maternal depression and parenting in relation to child internalizing symptoms and asthma disease activity. Journal of Family Psychology. 2008;22(2):264–273. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.22.2.264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logsdon MC, Birkimer JC, Usui WM. The link of social support and postpartum depressive symptoms in African-American women with low incomes. MCN The American Journal of Maternal/Child Nursing. 2000;25(5):262–266. doi: 10.1097/00005721-200009000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovasi GS, Diez Roux AV, Hoffman EA, Kawut SM, Jacobs DR, Jr, Barr RG. Association of environmental tobacco smoke exposure in childhood with early emphysema in adulthood among nonsmokers: the MESA-lung study. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2010;171(1):54–62. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandl KD, Tronick EZ, Brennan TA, Alpert HR, Homer CJ. Infant health care use and maternal depression. Archives of Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine. 1999;153(8):808–813. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.153.8.808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLennan JD, Offord DR. Should postpartum depression be targeted to improve child mental health? Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2002;41(1):28–35. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200201000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moon RY, Gingras JL, Erwin R. Physician beliefs and practices regarding SIDS and SIDS risk reduction. Clinical Pediatrics. 2002;41(6):391–395. doi: 10.1177/000992280204100603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller DT, Collins BN. Pediatric otolaryngologists’ actions regarding secondhand smoke exposure: Pilot data suggest an opportunity to enhance tobacco intervention. Otolaryngology - Head and Neck Surgery. 2008;139(3):348–352. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2008.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NAMI. African American Women and depression: Fact sheet. 2009 Retrieved August 1, 2010, from www.nami.org.

- O’Hara MW. Postpartum depression: what we know. J Clin Psychol. 2009;65(12):1258–1269. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paperwalla KN, Levin TT, Weiner J, Saravay SM. Smoking and depression. Medical Clinics of North America. 2004;88(6):1483–1494. x–xi. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2004.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park ER, Chang Y, Quinn V, Regan S, Cohen L, Viguera A, et al. The association of depressive, anxiety, and stress symptoms and postpartum relapse to smoking: a longitudinal study. Nicotine and Tobacco Research. 2009;11(6):707–714. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntp053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pascoe JM, Stolfi A. Maternal depression and the pediatrician. Pediatrics. 2004;113(2):424. doi: 10.1542/peds.113.2.424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pederson LL, Ahluwalia JS, Harris KJ, McGrady GA. Smoking cessation among African Americans: what we know and do not know about interventions and self-quitting. Preventive Medicine. 2000;31(1):23–38. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2000.0669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PDPH. Health Center Service Areas: Examining population health in Philadelphia. Department of Public Health; 2009. [Accessed July, 2012]. http://www.phila.gov/health/pdfs/2009_Health_Center_Service_Area_Report.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Pratt LA, Brody DJ. Depression in the United States Household Population, 2005–2006. 2008 Retrieved September 1, 2010, from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db07.pdf. [PubMed]

- Radloff L. A CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychology Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson HL, Walker AM, Horne RS. Maternal smoking impairs arousal patterns in sleeping infants. Sleep. 2009;32(4):515–521. doi: 10.1093/sleep/32.4.515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts RE. Reliability of the CES-D Scale in different ethnic contexts. Psychiatry Res. 1980;2(2):125–134. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(80)90069-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosman EA, Yoshikawa H. Effects of welfare reform on children of adolescent mothers: moderation by maternal depression, father involvement, and grandmother involvement. Women Health. 2001;32(3):253–290. doi: 10.1300/J013v32n03_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Severson HH, Andrews JA, Lichtenstein E, Wall M, Zoref L. Predictors of smoking during and after pregnancy: a survey of mothers of newborns. Preventive Medicine. 1995;24(1):23–28. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1995.1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shalowitz MU, Mijanovich T, Berry CA, Clark-Kauffman E, Quinn KA, Perez EL. Context matters: a community-based study of maternal mental health, life stressors, social support, and children’s asthma. Pediatrics. 2006;117(5):e940–948. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-2446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siefert K, Finlayson TL, Williams DR, Delva J, Ismail AI. Modifiable risk and protective factors for depressive symptoms in low-income African American mothers. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2007;77(1):113–123. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.77.1.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sohr-Preston SL, Scaramella LV. Implications of timing of maternal depressive symptoms for early cognitive and language development. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2006;9(1):65–83. doi: 10.1007/s10567-006-0004-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka K, Miyake Y, Sasaki S. The effect of maternal smoking during pregnancy and postnatal household smoking on dental caries in young children. Journal of Pediatrics. 2009;155(3):410–415. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2009.03.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong VT, Jones JR, Dietz PM, D’Angelo D, Bombard JM. Trends in smoking before, during, and after pregnancy - Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS), United States, 31 sites, 2000–2005. MMWR Surveillane Summary. 2009;58(4):1–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turney K. Maternal depression and childhood health inequalities. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2011;52(3):314–332. doi: 10.1177/0022146511408096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Twardella D, Bolte G, Fromme H, Wildner M, von Kries R. Exposure to secondhand tobacco smoke and child behaviour - results from a cross-sectional study among preschool children in Bavaria. Acta Pediatrica. 2010;99(1):106–111. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2009.01522.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. Philadelphia city, Pennsylvania, DP02 Selected social characteristics in the United States [Data] [Accessed July, 2012];2010 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates. 2006–2010 Retrieved from http://factfinder2.census.gov.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy People 2020. Washington, D. C: 2011. Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. [Google Scholar]

- Winickoff JP, Park ER, Hipple BJ, Berkowitz A, Vieira C, Friebely J, et al. Clinical effort against secondhand smoke exposure: development of framework and intervention. Pediatrics. 2008;122(2):e363–375. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-0478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wisner KL, Parry BL, Piontek CM. Clinical practice. Postpartum depression. New England Journal of Medicine. 2002;347(3):194–199. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp011542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]