Abstract

Purpose

Recently, a new renal cell cancer (RCC) syndrome has been linked to germline mutation of multiple subunits (SDHB/C/D) of the Krebs cycle enzyme, succinate dehydrogenase. We report our experience with diagnosis, evaluation and treatment of this novel form of hereditary kidney cancer.

Materials and Methods

Patients with suspected hereditary kidney cancer were enrolled on an NCI-IRB approved protocol to study inherited forms of kidney cancer. Individuals from families with germline SDHB, SDHC and SDHD mutations and kidney cancer underwent comprehensive clinical and genetic evaluation.

Results

Fourteen patients from twelve SDHB mutation families were evaluated. Patients presented with RCC at an early age, 33 yrs (range 15–62 yrs), four developed metastatic kidney cancer and some families were found to have no manifestations other than kidney tumors. An additional family with six individuals found to have clear cell RCC that presented at a young average age, 47 yrs (range 40–53yrs), was identified with a germline SDHC mutation (R133X), two of which developed metastatic disease. A patient with a history of carotid body paragangliomas and a very aggressive form of kidney cancer was evaluated from a family with germline SDHD mutation.

Conclusions

SDH-RCC can be an aggressive type of kidney cancer, especially in younger individuals. Although detection and management of early tumors is most often associated with good outcome, based on our initial experience with these patients and our long term experience with HLRCC, we recommend careful surveillance of patients at risk for SDH-RCC and wide surgical excision of renal tumors.

Keywords: renal cell cancer (RCC), hereditary kidney cancer, Krebs cycle, Succinate dehydrogenase

Introduction

Kidney cancer is fundamentally a metabolic disease; each of the genes known to cause kidney cancer, VHL, MET, FLCN, fumarate hydratase, succinate dehydrogenase, TSC1, TSC2, TFE3, TFEB, MITF, and PTEN is involved in the fundamental cellular processes regulating the cell’s response to sensing oxygen, iron, nutrients and energy.1 Understanding the fundamental metabolic basis of kidney cancer should provide the foundation for the development of novel approaches to therapy for this disease.

Germline mutation of the Krebs cycle (tricarboxylic acid cycle) enzyme, fumarate hydratase, is associated with an aggressive form of type II papillary kidney cancer in patients affected with Hereditary Leiomyomatosis and Renal Cell Carcinoma (HLRCC).2–4 In fumarate hydratase-deficient kidney cancer, a prototypic example of the Warburg effect in cancer, oxidative phosphorylation is severely compromised and the cells undergo a metabolic shift to aerobic glycolysis to generate ATP and other metabolites required for rapid growth and cell division.5–8 The result is an extremely aggressive, lethal form of kidney cancer with a very high metabolic rate that has a propensity to metastasize when the primary tumor is very small (less than 1 centimeter).3

A second form of inherited kidney cancer characterized by a Krebs cycle gene mutation was initially reported by Vanharanta, et al., who described three patients with kidney cancer in families with a germline mutation of succinate dehydrogenase B (SDHB) also associated with hereditary paraganglioma (PGL), a group of diseases associated with head and neck PGL that can include a history of pheochromocytoma (PCC).9 While long recognized as having a hereditary component, the genes associated with this condition were difficult to identify as mapping studies linked suspected genes to different chromosomal regions (Figure 1A). Over the past decade the genetic basis of this syndrome has been identified and four specific syndromes are linked to gene mutations in a multi-complex Krebs cycle/electron transport chain enzyme, succinate dehydrogenase (SDH).10–13 This enzyme is made up of four subunits (SDHA, SDHB, SDHC, and SDHD) and catalyzes the oxidation of succinate to fumarate (Figure 1B). Additionally, germline mutations of SDHB, SDHC and SDHD have been identified in patients with a combination of gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) and paraganglioma (PGL) and patients presenting solely with GIST.14,15 Multiple reports identified the presence of RCC in patients with SDHB mutations either with or without a personal or family history of PGL and/or PCC.9,16–22 Furthermore, a recent investigation describing 2 individuals with Cowden or Cowden-like syndromic features including RCC, but no PTEN mutation, reported SDHD gene variants that affected the AKT and/or MAPK pathways. 23 After this work was initially submitted for publication, Malinoc et al. reported an individual patient with a germline SDHC gene mutation with personal and family history of PGL who was found to have RCC tumors with loss of the wild-type SDHC allele.24 Little is known about the clinical features and management of patients with SDH mutation-associated RCC (SDH-RCC). In this report we describe the National Cancer Institute (NCI) experience with patients with SDH-RCC, including management and screening recommendations.

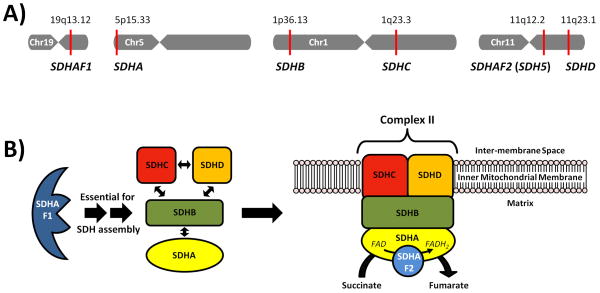

Figure 1. The Chromosomal Location of the Succinate Dehydrogenase Enzyme Genes and the Enzyme Assembly.

A) Chromosomal mapping of SDHAF1 (19q13.12), SDHA (5p15.33), SDHB (1p36.13), SDHC (1q23.3), SDHAF2 (11q12.2), SDHD (11q23.1). B) The succinate dehydrogenase enzyme subunits (SDHA/B/C/D) are assembled with the aid of the SDHAF1 protein and localized with the mitochondrial membrane, in association with the SDHAF2 protein, to form both Complex II of the Electron Transport Chain and a critical component of the Kreb’s Cycle. (adapted from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:SDHBfunction.svg)

Materials and Methods

Patients at risk for familial kidney cancer were evaluated on an NCI-IRB approved clinical protocol that included genetic counselling and evaluation. SDH genetic testing was recommended if patients had early onset kidney cancer or suspected hereditary PGL or PCC. Genetic testing was performed on young patients with RCC (those under 45 years of age), those with bilateral/multifocal kidney tumors, and in families with suspected hereditary RCC. As part of the protocol, patients underwent genetic counselling prior to germline mutation testing. DNA was extracted from whole blood and mutation analyses were performed by direct sequencing on all coding exons of the SDHB (NM_003000.2), SDHC (NM_003001.3) and SDHD (NM_003002.2) genes. Testing was performed at a Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA) certified laboratory. Members of affected kindreds with SDHB, SDHC or SDHD mutations that had clinical manifestations such as RCC or pheochromocytoma/paraganglioma were offered evaluation.

Patients and families affected with SDHB, SDHC and SDHD germline mutations and RCC were identified. All available records, imaging, and pathologic slides were reviewed. Family members who were not evaluated at the NCI were included if both the clinical and pathologic information was available. Patient information was evaluated in addition to individual and familial manifestations of SDH mutation. Radiologic characteristics from contrast enhanced CT or MRI imaging were reviewed for laterality, tumor characteristics, the presence of multifocality, the degree of contrast-enhancement by Hounsfield units (HU), associated renal cysts, and the presence of necrosis, fat, or calcifications. The method of diagnosis (incidental, SDH germline mutation screening, or local, systemic symptoms), surgical management, 2010 TNM stage, tumor size, and margin status were evaluated.

Results

Succinate Dehydrogenase B (SDHB) Kidney Cancer

Fourteen patients from 12 families with germline SDHB mutations were evaluated. The family histories of 11 SDHB mutation-associated families were reviewed (one patient was adopted). In these kindreds, five (45.5%) only had known family members affected with RCC (Figure 2A) and six (54.5%) additionally had known family members with a chromaffin (PCC/PGL) tumor (Figure 2B). Two patients had a history of PGL or PCC and one patient had a metachronous, contralateral kidney cancer recurrence 17 years after initial renal tumor resection (Table 1). Four patients presented with local symptoms; three had systemic symptoms (one with a brain metastasis, and two with back pain from osseous metastases) and the remaining were diagnosed incidentally or by family surveillance screening. The mean and median age at SDHB- associated RCC presentation was 33 and 30 years old, respectively (range 15–61 years).

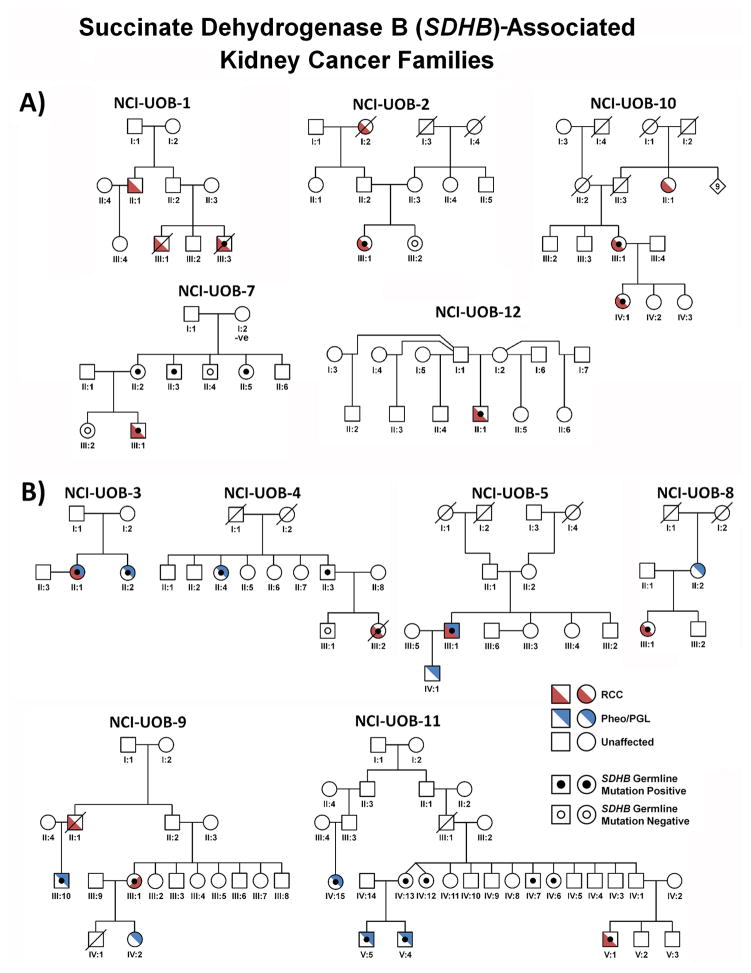

Figure 2. SDHB-Associated SDH-RCC Family Pedigrees.

Pedigrees for SDHB-associated SDH-RCC families (except the adopted patient UOB-6), who was adopted) are shown in two groups: A) families presenting with kidney cancer only and B) families with RCC and pheochromocytoma/paraganglioma. Red denotes RCC and blue denotes pheochromocytoma/paraganglioma (PCC/PGL). SHDB germline mutation positive patients are designated by a black dot and assessed SDHB germline mutation negative patients are designated by an empty black circle.

Table 1.

Clinicopathologic and mutation analysis for SDHB, SDHC and SDHD RCC patients.

| SDH Subunit | Family | Patient | Mutation | Age | Chromaffin Tumor History | Metastatic Disease (site) | Sex | Presentation | Stage (TMN) | Size | Surgery | Status at Follow-Up (months) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Personal | Family | ||||||||||||

| B | UOB-1 | III:3 | Exon 1 Deletion | 36 | No | No | Yes (OS) | M | Systemic | TxNxM1 | N/A | Biopsy | DOD (N/A) |

| B | UOB-1 | III:1 | N/S | 25 | No | No | Yes (OS) | M | Systemic | T1aN0M1 | 3.8 | RN | DOD (N/A) |

| B | UOB-2 | III:1 | Exon 1 Deletion | 27 | No | No | No | F | Incidental | T1aN0M0 | 2.7 | PN | NED (17.0) |

| B | UOB-3 | II:1 | Exon 1 Deletion | 42 | Yes | Yes | No | F | Incidental | T1aN0M0 | 2.2 | PN | NED (3.3) |

| B | UOB-4 | III:2 | c.137G>A (p.Arg46Gln) | 32 | No | Yes | Yes (OS) | F | Systemic | T3aN0M1 | 5 | RN | DOD (6.1) |

| B | UOB-5 | III:1 | c.268C>T (p.Arg90X) | 61 | Yes | Yes | No | M | Incidental | T1aN0M0 | 2 | PN | NED (50.4) |

| B | UOB-6 | - | c.286+2T>A (Splice) | 37 | NA | NA | No | M | Local | Unknown | 11 | RN | NED (30.0) |

| B | UOB-7 | III:1 | c.379A>C (p.Ile127Leu) | 28 | No | No | No | M | Local | T1bN0M0 | 5 | PN | NED (36.2) |

| B | UOB-8 | III:1 | c.541-2A>G (Splice) | 19 | No | Yes | No | F | Incidental | T1aN0M0 | 2 | PN | NED (40.6) |

| B | UOB-9 | III:1 | c.689G>A (pArg230His) | 52 | No | Yes | No | F | Incidental | T1aN0M0 | 5 | RN | NED (35.5) |

| B | UOB-10 | IV:1 | c.286G>A (p.Gly96Ser) | 17 | No | No | No | F | Local | T2aN0M0 | 9 | RN | NED (212.4) |

| 34 | Incidental | T1aN0M0 | 1.5 | PN | |||||||||

| B | UOB-10 | III:1 | c.286G>A (p.Gly96Ser) | 55 | No | No | Yes (LI,OS) | F | Incidental | T1aN0M0 | 1.8 | PN | AWD (65.8) |

| B | UOB-11 | V:1 | c.268C>T (p.Arg90X) | 15 | No | Yes | No | M | Incidental | T1aN0M0 | 2 | PN | NED (10.8) |

| B | UOB-12 | II:1 | c.137G>A (p.Arg46Gln) | 17 | No | No | No | M | Local | T2aN0M0 | 7.2 | RN | NED (6.0) |

| C | UOB-13 | II:14 | N/S | 46 | No | Yes | Yes (N/A) | M | Unknown | TxNxM1 | N/A | RN | DOD (133.5) |

| C | UOB-13 | II:11 | N/S | 52 | No | Yes | No | F | Unknown | Unknown | N/A | RN | DOC (182.7) |

| C | UOB-13 | II:9 | c.397C>T (p.Arg133X) | 53 | No | Yes | Yes (LI,LU,BR) | F | Local | T2aN0M0 | 10 | RN | AWD (54.8) |

| 68 | Incidental | T1aN0M1 | 2.5 | PN | |||||||||

| C | UOB-13 | II:13 | c.397C>T (p.Arg133X) | 49 | No | Yes | No | F | Incidental | T1aN0M0 | 3 | PN | NED (240.8) |

| C | UOB-13 | II:8 | N/S | 44 | No | Yes | No | F | Incidental | T1aN0M0 | 1.5 | PN | NED (62.0) |

| C | UOB-13 | III:3 | c.397C>T (p.Arg133X) | 40 | No | Yes | No | M | Screened | T1aN0M0 | 2 | PN | NED (12.3) |

| D | UOB-14 | III:1 | c.239G>T (p.Leu80Arg) | 45 | Yes | Yes | Yes (OS,LU,R) | M | Unknown | T3aNxM1 | 8 | RN | DOD (18.7) |

N/S – Not Screened for Mutation N/A – Not Available RN – Radical Nephrectomy PN – Partial Nephrectomy Incidental – Detected while Asymptomatic, Local – Localized Symptoms, Systemic – Metastatic site/Constitutional Symptoms, Screened – Due to Germline Mutation Site of Metastases: LI – Liver, LU – Lung, OS – Osseous, BR – Brain, R - Retroperitoneal DOD – Dead of Disease, AWD – Alive with Disease, NED – No Evidence of Disease, DOC – Died of Other Cause

Preoperative imaging was available for ten SDHB mutation patients. No patient was found with synchronous bilateral or multifocal renal masses at diagnosis. Solid tumors were observed in seven (70%) patients while three (30%) had mixed solid/cystic lesions, which were classified as Bosniak IV cysts. All tumors demonstrated a brisk enhancement pattern typical of other solid renal neoplasms.

SDHB-RCC renal tumors were managed with partial or radical nephrectomy either at the NCI or outside institution. One patient (UOB-1 III:3) with kidney cancer who presented with widely metastatic disease, including brain metastases, was not a surgical candidate and received a renal biopsy prior to hospice care. All patients treated with partial nephrectomy had a final negative margin; however, one patient undergoing a robotic partial nephrectomy was converted to an open surgical procedure after an initial positive margin was found on the intraoperative frozen section. SDHB-associated renal tumor histologies were variable; however most tumors shared common “oncocytic neoplastic” features (M. Merino et. al, In Preparation, Figure 3D). Four SDHB mutation patients were found to have metastatic disease, three (UOB-1 III:1 and III:3, UOB-4 III:2) at the time of initial presentation and one patient (UOB-10 III:1) with T1a disease that recurred in the liver three years post-operatively (Figure 3E and 3F). The pathologic tumor stage for available cases was T1/T2 (Figure 3A and 3B) in 12/13 cases (92.3%) and T3a in the remaining case (UOB-4 III:2, Figure 3C). No patients were found to have clinical or pathologic nodal involvement.

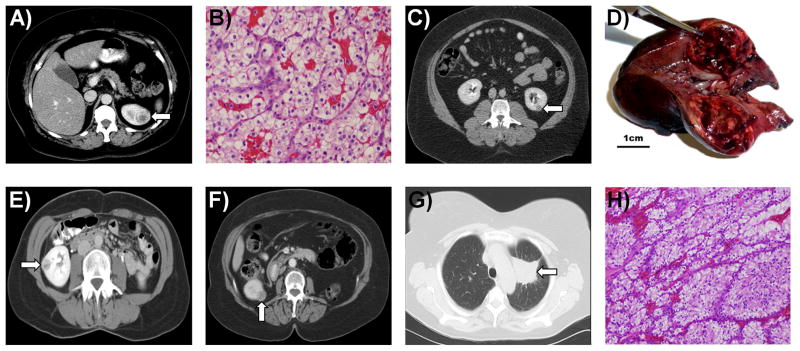

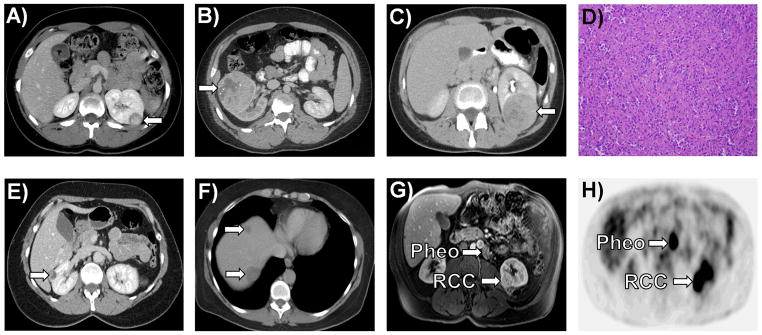

Figure 3. Imaging and Histology of SDHB-Associated Kidney Cancer.

A) A left sided 2.2 cm T1a “oncocytic renal cancer” was detected incidentally in a 19 year old female (UOB-8 III:1). B) A 17 year old male (UOB-12 II:1), who presented with back pain and gross hematuria, underwent a right radical nephrectomy and was found to have a 7.2 cm (T2a) right “oncocytic renal cancer” with sarcomatoid features. C) A 32 year old female (UOB-4 III:2) presented with a 3 month history of back pain and a bone marrow biopsy that revealed ‘metastatic cancer consistent with renal primary”. She underwent a radical nephrectomy for this T3aN0M1 kidney cancer that was diagnosed as an “oncocytic cancer” (D). She died with widespread disease 7 months after surgery. E) Patient UOB-10 III:1 presented as a 55 year old female with a 2.8 cm T1aN0M0 renal mass, which was resected at an outside hospital with clean surgical margins. F) Two and a half years later she was found to have hepatic metastases. G) Patient UOB-5 III:1 came to NCI for routine screening for his family history of SDHB mutation associated disease. On screening he was incidentally found to have a left lower pole 2.8 cm T1aN0M0 renal mass and a 1 cm periaortic paraganglioma. H) Preoperative [18]fluoro-deoxyglucose PET scan was positive for both the renal mass and the paraganglioma. A left partial nephrectomy and excision of the periaortic paraganglioma was performed.

All the SDHB mutations, except SDHB p.Ile127Leu, have been previously shown to be associated with PGL and/or PCC, and thus were considered pathogenic (LOVD v2.0 TCA Cycle Gene Mutation Database)25. The novel p.Ile127Leu alters an amino acid that has alternative variants (p.Ile127Asn, p.Ile127Ser) that have been shown to be associated with PGL and/or PCC, and was thus considered pathogenic. Alterations were observed throughout the length of the SDHB gene consisting of 1 nonsense (c.268C>T p.Arg90X), 4 missense (c.137G>A p.Arg46Gln, c.286G>A, p.Gly96Ser, c.379A>C p.Ile127Leu, c.689G>A p.Arg230His), 2 splice site altering mutations (c.286+2T>A, c.541-2A>G) and three complete deletions of exon 1. Mutations occurred along the length of the SDHB protein including all three critical regulatory sites (Figure 4A and 4B).

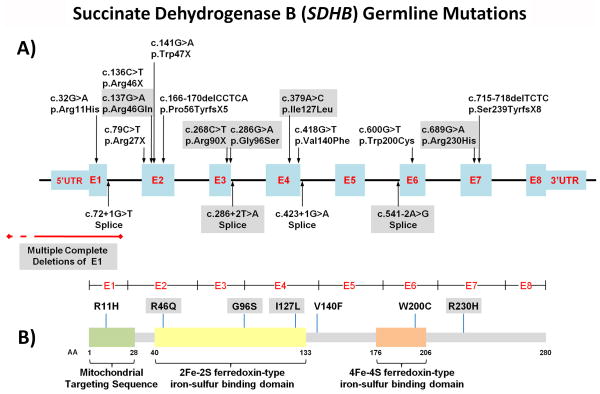

Figure 4. Mutation Map of SDHB mutations associated with SDH-RCC Families.

A) Map of SDHB gene mutation in SDHB-associated families with RCC. Exons are shown in blue and introns shown in black lines. SDHB mutations in NCI-UOB families are demonstrated in grey boxes. Previously published mutations are unshaded. Deletions in exon 1 are shown in red. B) SDHB protein mutation map demonstrates missense mutations located throughout the protein with amino acid changes in the mitochondrial targeting sequence as well as both iron-sulfur binding domains.

Succinate Dehydrogenase C (SDHC) Kidney Cancer

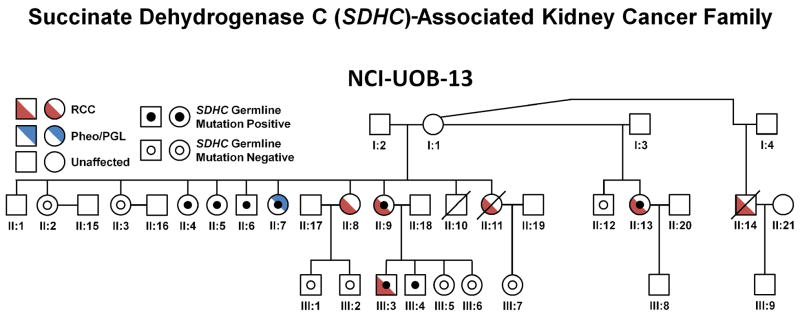

Family UOB-13 (Figure 5) has been followed at NCI for nearly 10 years. Five members of this family were found to have kidney cancer. While no germline mutations were detected in known familial RCC genes such as VHL, FLCN, FH, SDHB and SDHD, mutation analysis of SDHC revealed a c.397C>T germline mutation in the proband, her affected cousin and two of her offspring. Subsequent investigation of the family’s medical history revealed that one member of this kindred had a history of a neck paraganglioma (UOB-13 II:7). Abdominal imaging of a mutation positive family member (UOB-13 III:3) identified the presence of a small renal tumor, which was removed surgically (Figures 6C and 6D). The mean and median ages of SHDC-RCC presentation were 47 and 48 years old, respectively (range 40–53 years old).

Figure 5. SDHC-Associated SDH-RCC.

The pedigree for the SDHC-associated SDH-RCC family NCI-UOB-13 is shown with the occurrence of RCC (red) and/or pheochromocytoma/paraganglioma (Pheo/PGL) (blue). SHDC germline mutation positive patients are designated by a black dot and assessed SDHC germline mutation negative patients are designated by an empty black circle.

Figure 6. SDHC-Associated Kidney Cancer.

A) Patient UOB-13 II:13 was a 49 year old female who presented for screening with a germline SDHC mutation and with 3 sisters affected with kidney cancer. On screening she was found to have a 3.3 cm enhancing left renal lesion. She underwent a partial nephrectomy with a wide surgical margin for removal of a T1aN0M0 clear cell kidney cancer (B).

C) Patient UOB-13 III:3 was a 38 year old male who was found to have a germline SDHC mutation. On screening evaluation a 1.4 cm enhancing, exophytic left renal mass was identified. He underwent a retroperitoneal laparoscopic partial nephrectomy with wide surgical margins for a clear cell kidney cancer (D).

E) Patient UOB-13 II:8 was a 44 year old female who presented to the NCI for an evaluation of familial renal cancer. She was found to have a 2 cm right renal mass which was removed by right laparoscopic partial nephrectomy and found to be a T1aN0M0 clear cell kidney cancer. She remains free of disease 8 years after surgery.

Patient UOB-13 II:9 presented at age 53 with a 10 cm renal tumor (clear cell), for which she had had a left radical nephrectomy. She subsequently underwent a cholecystectomy for a gallbladder recurrence and was found to have a 2.5 cm right renal tumor (F), for which she underwent a partial nephrectomy for a clear cell kidney cancer (H). She was subsequently found to have pulmonary metastases (G) for which she has received systemic therapy.

Preoperative imaging for four patients from family UOB-13 with SDHC renal tumors was available for evaluation. No patient was found with multifocal renal involvement; however, one patient (UOB-13 II:9) subsequently developed metachronous, contralateral disease in the presence of widespread metastases (treated with cholecystectomy, brain stereotactic radiosurgery, and partial nephrectomy) (Figure 6F and 6H). All renal lesions were solid and demonstrated a brisk enhancement pattern. No patient was found with renal cystic disease and renal tumors had no evidence of fat or calcification.

Strikingly, all seven renal tumors from this family (UOB-13) with germline SDHC mutation were found to be classic clear cell RCC (Figure 6B and 6H). Fuhrman grading demonstrated that all were low-grade lesions (one grade 1 and six grade 2). Of the five tumors with known tumor stage, all were T1/2 (Figure 6A and 6E). Two patients developed metastatic disease, one of which presented with and died from metastatic disease (UOB-13 II:14), while the other (UOB-13 II:9) remains alive on systemic treatment.

The germline heterozygous SDHC nonsense mutation (c.397C>T p.Arg133X) identified in UOB-13 was previously associated with PGL/PCC.25–27 This mutation would be predicted to result in the loss of full-length protein production, which is also the case of the single SDHC mutation previously associated with RCC, pMet1Ile.24

Succinate Dehydrogenase D (SDHD) Kidney Cancer

Patient UOB-14 III:3 came from a family with an extensive history of carotid body tumors (CBT) (father, two aunts, an uncle and paternal grandfather) and had a brother with a PCC (Figure 7A). This patient presented with bilateral CBT at the ages of 17 (left side) and 21 (right side), both of which were removed surgically. He later was found with hypertension and panic attacks that led to the discovery and resection of a retroperitoneal, extra-adrenal pheochromocytoma (PGL) at age 28 and a recurrent extra-adrenal PGL at age 31. At age 45, an 8 cm renal mass was detected, resulting in a left radical nephrectomy at an outside institution, which was found to be T3aNxM1 clear cell renal carcinoma. He was subsequently evaluated at NCI where staging revealed retroperitoneal, pulmonary, and osseous metastases (Figure 7B and 7C) as well as recurrent bilateral CBTs and he expired nineteen months after the diagnosis of RCC. Both he and his son were found to have an SDHD mutation (c.239G>T p.Leu80Arg) that has been previously shown to associate with PGL/PCC.26

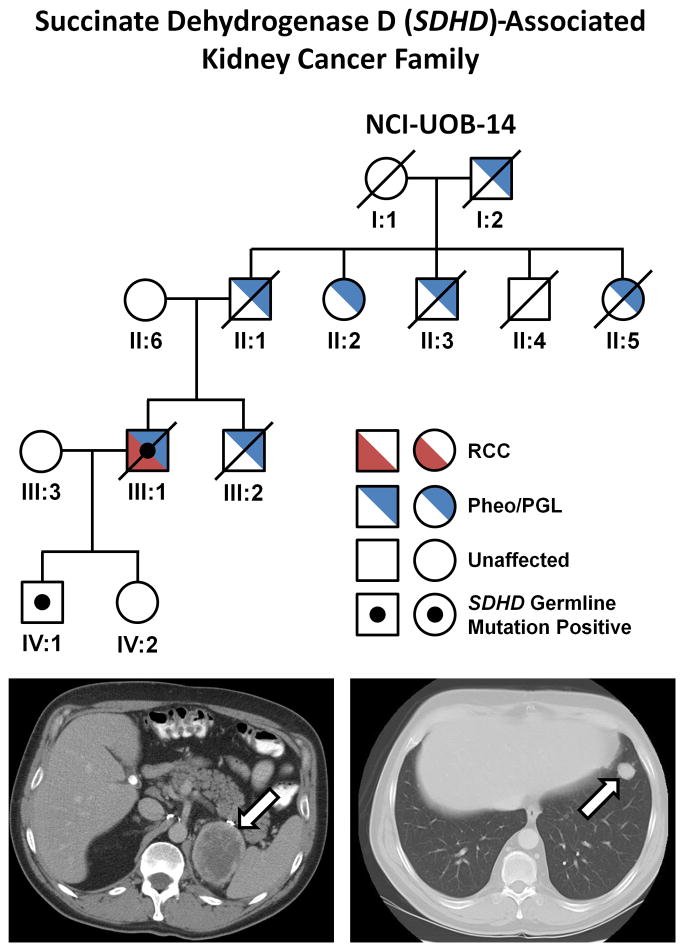

Figure 7. SDHD-Associated SDH-RCC.

A) The pedigree for the SDHD-associated SDH-RCC family (NCI-UOB-14) is shown with the occurrence of RCC (red) and/or pheochromocytoma/paraganglioma (PCC/PGL) (blue). The mutation positive patients are designated by a black dot. Patient III:1 had multiple carotid body tumors and retroperitoneal, extra-adrenal pheochromocytomas (PGL). At age 45 he was found to have an 8 cm left renal mass, which was removed surgically and found to be a T3aNxM1 clear cell renal carcinoma. He was subsequently found to have retroperitoneal (B) and pulmonary (C) recurrence and he died 18 months after the diagnosis of kidney cancer.

Discussion

We report the NCI experience with SDHB-, SDHC- and SDHD-RCC with a focus on clinical and genetic features and the management of this newly described hereditary RCC syndrome. Patients with early onset kidney cancer, those with bilateral, multifocal renal tumors or those with a family history of RCC or other cancers should be considered for SDH germline mutation testing. When considering germline SDH testing, a personal or family history of PGL, PCC, or a GIST should raise awareness of possible SDHB, SDHC or SDHD alterations, however RCC can present as the sole finding in these families.

Early age of onset of RCC has been previously observed in patients with SDHB mutations.22,28,29 Here we confirm this observation, reporting a mean and median age of onset as 33 and 30 years old respectively for SDHB-RCC. In SDHC-RCC the age of onset of kidney cancer also appears younger than the general RCC population but older than those with SDHB mutations (mean and median age 47 and 48, respectively, range = 40–53 years old). Based on our experience, patients with early onset RCC should raise suspicion for SDH kidney cancer.

Our early clinical experience with this disorder and the understanding of its metabolic basis has shaped our management in this patient population. Several of our patients died of metastatic kidney cancer and several developed metastatic disease from small primary tumors. Knowledge of HLRCC, the other Krebs cycle-associated kidney cancer, has influenced our management of SDH-RCC. HLRCC kidney cancers behave aggressively and may spread when the primary tumors are small.3 The metabolic basis of HLRCC and SDH-RCC share common features which may contribute to a similarly aggressive form of RCC. The FH protein lies one enzyme downstream from SDH and the metabolic basis of enzymatic loss of function may have metabolic similarity with the impairment of Krebs cycle function, reliance on glycolysis, and a metabolic shift to aerobic glycolysis (the Warburg effect).30

We believe SDH-RCC should be managed in a manner similar to HLRCC renal tumors.3 As SDH-RCC tumors have the potential to spread when the tumors are small, early identification and prompt surgical intervention is recommended. While active surveillance is often recommended for the management of small (less than 3 cm) VHL, HPRC and BHD renal tumors, surveillance is not recommended for SDH-RCC. In the surgical management of SDH-RCC renal tumors, the potential for the development of metachronous, bilateral RCC (UOB-9 III:1, UOB-10 IV:1) should be considered. As with other hereditary cancer syndromes, SDH-RCC patients may be at a lifelong risk to develop renal tumors and partial nephrectomy should be considered when feasible. Because of the potential for the development of aggressive tumors, we recommend wide surgical excision of SDH-RCC tumors. Similar to fumarate hydratase-deficient kidney tumors, SDH-deficient kidney cancer is characterized by impaired oxidative phosphorylation and a metabolic shift to aerobic glycolysis (Wei, et al, in preparation). If an SDH-RCC patient is suspected of having advanced disease, FDG-PET scanning is recommended.

Recommendations for SDH-RCC Evaluation, Management and Surveillance

SDHB/C/D germline mutation testing is recommended for patients with early onset kidney cancer (under age 45), for those with a family history of PCC or PGL and for those with a family history of kidney cancer. When a renal mass lesion is detected in a SDHB/C/D germline carrier, surgical resection with a wide surgical margin is recommended. Annual screening for the presence of kidney cancer and PCC/PGL is recommended. The PET scan has, in our limited experience, also been helpful in identifying foci of metastatic disease (Figure 3G and 3H).

Conclusions

Succinate dehydrogenase is a critical enzyme in the Krebs cycle and electron transport chain. Germline mutations in SDHB, SDHC and SDHD are not only associated with hereditary paraganglioma syndromes but also with hereditary kidney cancer. We have characterized the clinical manifestations and management of SDHB-, SDHC- and SDHD mutation-associated RCC. SDH-RCC can present at an early age and individuals under age 45 should be considered for this hereditary form of kidney cancer even in the absence of a family history. When SDH-RCC kidney tumors are detected at an early stage, patients can have a good outcome. However, patients with SDH-RCC can be at risk for the early development of metastatic disease if the tumor is not detected and treated early.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Cancer Institute, Center for Cancer Research. This project has been funded in part with federal funds from the Frederick National Laboratory for Cancer Research, National Institutes of Health, under contract HHSN261200800001E. The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products or organizations imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. We thank Dr. Sheldon Shuch and Ms. Maria Kwon for manuscript review and Georgia Shaw for editing and graphics support.

References

- 1.Linehan WM, Srinivasan R, Schmidt LS. The genetic basis of kidney cancer: a metabolic disease. Nature Reviews Urology. 2010;7:277. doi: 10.1038/nrurol.2010.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tomlinson IP, Alam NA, Rowan AJ, et al. Germline mutations in FH predispose to dominantly inherited uterine fibroids, skin leiomyomata and papillary renal cell cancer. Nat Genet. 2002;30:406. doi: 10.1038/ng849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grubb RL, III, Franks ME, Toro J, et al. Hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer: a syndrome associated with an aggressive form of inherited renal cancer. J Urol. 2007;177:2074. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.01.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Toro JR, Nickerson ML, Wei MH, et al. Mutations in the fumarate hydratase gene cause hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer in families in North America. Am J Hum Genet. 2003;73:95. doi: 10.1086/376435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Warburg O, Posener K, Negelein E. Metabolism of the Carcinoma Cell. Biochem Z. 1924;152:309. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buchanan JW. Some limitations of Wargurg’s theory of the role of iron in respiration. Science. 1927;66:238. doi: 10.1126/science.66.1706.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yang Y, Valera VA, Padilla-Nash HM, et al. UOK 262 cell line, fumarate hydratase deficient (FH−/FH−) hereditary leiomyomatosis renal cell carcinoma: in vitro and in vivo model of an aberrant energy metabolic pathway in human cancer. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2010;196:45. doi: 10.1016/j.cancergencyto.2009.08.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tong WH, Sourbier C, Kovtunovych G, et al. The glycolytic shift in fumarate-hydratase-deficient kidney cancer lowers AMPK levels, increases anabolic propensities and lowers cellular iron levels. Cancer Cell. 2011;20:315. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.07.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vanharanta S, Buchta M, McWhinney SR, et al. Early-onset renal cell carcinoma as a novel extraparaganglial component of SDHB-associated heritable paraganglioma. Am J Hum Genet. 2004;74:153. doi: 10.1086/381054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baysal BE, Ferrell RE, Willett-Brozick JE, et al. Mutations in SDHD, a mitochondrial complex II gene, in hereditary paraganglioma. Science. 2000;287:848. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5454.848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Niemann S, Muller U. Mutations in SDHC cause autosomal dominant paraganglioma, type 3. Nat Genet. 2000;26:268. doi: 10.1038/81551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Astuti D, Douglas F, Lennard TW, et al. Germline SDHD mutation in familial phaeochromocytoma. Lancet. 2001;357:1181. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04378-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Burnichon N, Briere JJ, Libe R, et al. SDHA is a tumor suppressor gene causing paraganglioma. Hum Mol Genet. 2010;19:3011. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pasini B, McWhinney SR, Bei T, et al. Clinical and molecular genetics of patients with the Carney-Stratakis syndrome and germline mutations of the genes coding for the succinate dehydrogenase subunits SDHB, SDHC, and SDHD. Eur J Hum Genet. 2008;16:79. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Janeway KA, Kim SY, Lodish M, et al. Defects in succinate dehydrogenase in gastrointestinal stromal tumors lacking KIT and PDGFRA mutations. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010 doi: 10.1073/pnas.1009199108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Neumann HP, Pawlu C, Peczkowska M, et al. Distinct clinical features of paraganglioma syndromes associated with SDHB and SDHD gene mutations. JAMA. 2004;292:943. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.8.943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Srirangalingam U, Walker L, Khoo B, et al. Clinical manifestations of familial paraganglioma and phaeochromocytomas in succinate dehydrogenase B (SDH-B) gene mutation carriers. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2008;69:587. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2008.03274.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ricketts C, Woodward ER, Killick P, et al. Germline SDHB mutations and familial renal cell carcinoma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100:1260. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schimke RN, Collins DL, Stolle CA. Paraganglioma, neuroblastoma, and a SDHB mutation: Resolution of a 30-year-old mystery. Am J Med Genet A. 2010;152A:1531. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.33384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Housley SL, Lindsay RS, Young B, et al. Renal carcinoma with giant mitochondria associated with germ-line mutation and somatic loss of the succinate dehydrogenase B gene. Histopath. 2010;56:405. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2010.03482.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Henderson A, Douglas F, Perros P, et al. SDHB-associated renal oncocytoma suggests a broadening of the renal phenotype in hereditary paragangliomatosis. Fam Cancer. 2009;8:257. doi: 10.1007/s10689-009-9234-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gill AJ, Pachter NS, Clarkson A, et al. Renal tumors and hereditary pheochromocytoma-paraganglioma syndrome type 4. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:885. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1012357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ni Y, Zbuk KM, Sadler T, et al. Germline Mutations and Variants in the Succinate Dehydrogenase Genes in Cowden and Cowden-like Syndromes. Am J Hum Genet. 2008;83:261. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Malinoc A, Sullivan M, Wiech T, et al. Biallelic inactivation of the SDHC gene in renal carcinoma associated with paraganglioma syndrome type 3. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2012;19:283. doi: 10.1530/ERC-11-0324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bayley JP, Devilee P, Taschner PE. The SDH mutation database: an online resource for succinate dehydrogenase sequence variants involved in pheochromocytoma, paraganglioma and mitochondrial complex II deficiency. BMC Med Genet. 2005;6:39. doi: 10.1186/1471-2350-6-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Burnichon N, Rohmer V, Amar L, et al. The succinate dehydrogenase genetic testing in a large prospective series of patients with paragangliomas. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94:2817. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-2504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zbuk KM, Patocs A, Shealy A, et al. Germline mutations in PTEN and SDHC in a woman with epithelial thyroid cancer and carotid paraganglioma. Nat Clin Pract Oncol. 2007;4:608. doi: 10.1038/ncponc0935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ricketts CJ, Forman JR, Rattenberry E, et al. Tumor risks and genotype-phenotype-proteotype analysis in 358 patients with germline mutations in SDHB and SDHD. Hum Mutat. 2010;31:41. doi: 10.1002/humu.21136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gill AJ, Pachter NS, Chou A, et al. Renal Tumors Associated With Germline SDHB Mutation Show Distinctive Morphology. Am J Surg Pathol. 2011;35:1578. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e318227e7f4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Warburg O. On the origin of cancer cells. Science. 1956;123:309. doi: 10.1126/science.123.3191.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]