Abstract

Although the unique role of hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) niche in hematopoiesis has long been recognized, unsuccessful isolation of intact niche units limited their in vitro study, manipulation, and therapeutic application. Here, we isolated cell complexes based on size fractionation from mouse bone marrow (BM), characterized the derived cells, and transplanted them to irradiated mice. These cell complexes were the origin of both BM mesenchymal stem cells and various hematopoietic lineages when kept in appropriate culture conditions. They also had the potential of recruiting circulating HSC. Intraperitoneal transplantation of these structures into irradiated mice not only showed long-lasting hematopoietic multilineage reconstitution, but also could recover the stromal cells of BM. In conclusion, this study for the first time provides evidences on the feasibility and efficacy of transplantation of HSC in association with their native specialized microenvironment. As the molecular cross-talk between HSC and niche is crucial for their proper function, the proposed method could be considered as a novel hematopoietic transplantation strategy.

Introduction

The concept of stem cell niche, which was first proposed in 1978 by Schofield, refers to a specialized anatomical site that is essential for supporting normal stem cell functions including self renewal, differentiation, quiescence, and migration [1]. Although the anatomic location of the hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) niche is not exactly recognized, [2] it has recently been suggested to be localized in the vicinity of osteoblastic or vascular environments [3–5]. Mesenchymal stem cells (MSC) and HSC are considered as the two key elements of HSC niche units [6]. The physiological role of MSC is to provide niche elements such as myofibroblasts, osteocytes, pericytes, and endothelial cells [7,8]. In addition to these supportive cells, the HSC niche is composed of quiescent self-renewing primitive HSC that anchor in the center and different hematopoietic cell subsets that localize at the periphery, in distinct locations according to the stage of differentiation [2,9].

Despite the known fundamental role of niches for normal functions of HSC, they have not been yet subjected to isolation and in vitro characterization. In vitro expansion and in vivo transplantation of stem cells has routinely been performed on a single-cell basis. Some drawback of in vitro expansion of these cells such as the tendency for self-differentiation, [10] unchecked over-proliferation, [11] and loosing homing markers [12] could be attributed to the unnatural character of the current expansion methods. In addition, it is known for several years that chemotherapy and irradiation before transplantation destroys natural bone marrow (BM) structures including the niches, leading to their inability to support normal donor hematopoiesis [13] and incidence of donor cell leukemia [14]. Nevertheless, the current BM transplantation procedures are based on delivery of HSC as single cells. Therefore, it is rational to assume that culture and transplantation of HSC, in the context of their native intact niches, would not only increase the safety of their in vitro expansion, but also enhance their functionality for replacement of destroyed BM microenvironment. Promising results achieved with co-transplantation of HSC and MSC are in agreement with this assumption [15]. In addition, since MSC have immune-regulatory properties, transplantation of donor HSC with their associated stromal cells in the niche can prevent some life-threatening side effects such as Graft Versus Host Disease [16] and graft rejection [17]. The other probable advantage of this type of niche-based therapy is that the stromal component of niches can potentially contribute to healing of multiple organ failure following irradiation [18].

Successful isolation of niche units from native BM is the first step to reach the goal of HSC-niche transplantation. Based on the proposed properties for niche, we assume that it is a solid multicellular complex composed of hematopoietic and stromal cells, which are physically entwined with each other through cell surface molecules and extra cellular matrix. As these structures are probably suspended in the liquid phase of BM, we hypothesized that HSC niches can be enriched by size fractionation. Using this approach, niche-containing cell complexes were isolated from BM. Additionally, after in vitro characterization, their potential for reconstitution of BM was examined by transplantation into lethally irradiated mice.

Materials and Methods

Animals

C57BL/6 mice were purchased from Pasteur Institute of Iran (Tehran, Iran). Syngeneic GFP transgenic mice were kindly provided by Dr. M. Okabe (Osaka University, Osaka, Japan). Eight to 10 week-old male and female mice were used for this study. Animal care and experiments were according to the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Ethical approval was obtained from the ethics committee of stem cell technology research center, Tehran, Iran.

Collection of BM and size fractionation

After sacrificing the mice by cervical dislocation, the distal ends of tibia and femur bones were cut to expose the marrow. The bones were inserted into adapted centrifuge tubes as described previously [11,19] and centrifuged for 1 min at 600 g. The cell pellet derived from two femurs plus tibias of each mice was suspended in 5 mL of heparinized phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; Gibco-BRL, Grand Island, NY), and the diluted BM was filtered through a cell strainer of about 20 μm (adapted by cutting a 40 μm nylon mesh (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) and putting two pieces on top of each other). The residue and filtrate fractions were separately collected and washed with PBS.

Cell culture

The filtrate and residue fractions from each BM sample (n=8) were separately cultured and characterized as described previously [11].

Hematopoietic colony-forming cell assay

The filter-retained particles of BM were resuspended in culture medium (DMEM with 10% FBS (both from Gibco-BRL)) and seeded at low density in 35-mm Petri dishes (n=4). After adhesion of cell complexes to the culture dish (approximately 3–6 h after plating), the liquid medium was replaced with methylcellulose-based semisolid medium (M3434; Stem Cell Technologies, Vancouver, Canada) containing Iscove's Modified Dulbecco's Medium (Gibco-BRL). Assessment for development of colony-forming units (CFUs) was carried out after 10–14 days by microscopic observation and surface marker analysis.

HSC sorting

Flow cytometry analysis was performed on BM-derived cells from GFP-transgenic mice. The samples were treated with RBC lysis buffer and then incubated with either anti CD45R (B220)-PE, anti Ly-6G (Gr1)-PE, anti CD11b-PE, anti CD3e-PE, anti Ly-6A/E (Sca-1)-PE-Cy5, anti CD117 (c-Kit)-APC-conjugated antibodies or appropriate isotype control antibodies (all from eBioscience, San Diego, CA) at 4°C for 30 min. After washing with PBS, the cells were analyzed by FACS Aria II cell sorter (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) with 488 nm blue and 633 nm red lasers. Emission lights were collected with 530/30, 574/26,695/40, and 660/20 band pass filters for GFP, PE, PE-Cy5, and APC, respectively. Compensation procedure was performed by single-stained samples to correct fluorescence overlaps. For each sample, 10,000 events were acquired and FCS files were analyzed by FlowJo software (Tree Star, Ashland, OR).

Homing assay

To study the in vivo capacity of BM cell complexes to attract circulating HSC, female wild-type C57BL/6 mice were subjected to low-dose gamma irradiation (5 Gy). After 1 day, sorted BM-HSC from Syngeneic GFP-transgenic mice were transplanted at the dose of 5×104 per mouse into the irradiated recipients through lateral tail veins (n=3). Four days after transplantation, BM was harvested from the recipients and applied to the adapted 20 μm strainers. The filter-retained cell complexes were harvested and cultured in DMEM with 10% FBS. About 24 h after seeding, they attached and formed colonies, which were inspected for the presence of transplanted GFP-expressing cells in an ex vivo setting with a fluorescence microscope (TE2000-S; Nikon-Eclipse, Tokyo, Japan).

Transplantation of BM cell complexes

Female wild-type mice were exposed to total body irradiation (a single dose of 8.2 Gy). Twenty-four hours later, BM from two femurs plus tibias of each GFP-transgenic male mice was applied to the adapted 20 μm strainers and the filter-retained cell complexes were resuspended in 1 mL PBS and intraperitoneally transplanted to one recipient mouse. In different time points (days 1, 3, 5, 7, 9, 11, 13, 15, 20, and 25) after transplantation, the femurs from recipient mice (two mice for each time point) were removed and after decalcification in EDTA, were processed for Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) staining. In addition, for examination of chimerism, nucleated cells were isolated from BM, peripheral blood, and spleen of recipient mice (n=7) after 30 days of transplantation and treated with RBC lysis buffer (DAKO, Glostrup, Denmark). To prepare single cells from spleen, the tissue was mashed by plunger on 70 μm cell strainers (BD Biosciences). The ratio of GFP-expressing donor cells in these tissues was directly quantified by flow cytometry. For long-lasting multilineage analysis, at day 180, peripheral blood mononuclear cells from recipient mice (n=7) were incubated with hematopoietic lineage-specific phycoerythrin-labeled antibodies for Gr-1, Mac-1, B220, CD3, or isotype control antibodies (all from eBioscience) and analyzed by flow cytometry.

Flow cytometry, immunohistochemistry, and multilineage differentiation

These experiments were performed as described previously [11,20].

Statistics

Data are presented as mean±standard deviation.

Results

Filter-retained cell complexes display the features of HSC niche units

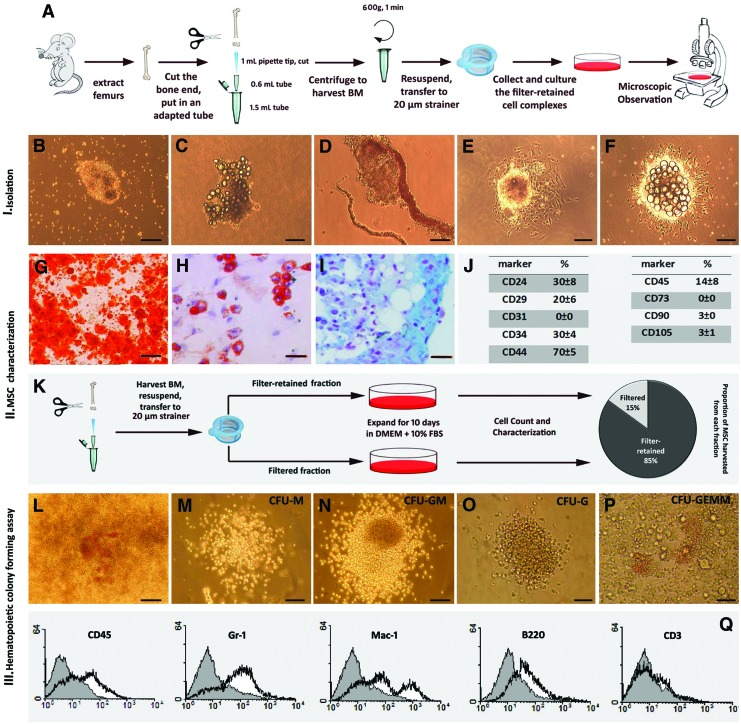

BM samples were applied to cell strainers and the residue was collected and resuspended in cell culture medium (Fig. 1A). Immediate microscopic observations showed small and large clusters of floating cell complexes (Fig. 1B) that occasionally contained fat droplets (Fig. 1C) and in some cases were attached to vascular structures (Fig. 1D). During the first few hours, they attached to the surface of culture plate and after 1–2 days, formed colonies containing fibroblast-like monolayer cells in the margins and small round outgrowing cells in the center, with fried egg morphology (Fig. 1E). Some of these colonies also contained central fat cells (Fig. 1F). Serial microscopic observation showed that on days 3–4, central round small cells and fat droplets were gradually released in the culture medium and the fibroblast-like cells expanded in a radial direction. These growing colonies were trypsinized and re-plated. On day 10, the emerging expanded stromal cells were transferred to an inductive culture media to assess their plasticity. They showed the capacity to differentiate to osteoblastic, adipogenic, and chondrogenic lineages (Fig. 1G–I). Negative controls for multilineage differentiation remained unstained (data not shown). In addition, surface marker analysis on day 10 showed that they were positive for CD24, CD29, CD44, and CD34 and negative for CD31, CD105, CD73, and CD90; CD45 (all from eBioscience) was weakly expressed (Fig. 1J). These data indicate that the expanded fibroblast-like cells display the features of murine BM-MSC [11]. To assess the existence of MSC in the filtrate and their proportion compared to the filter-retained aggregates, the filtrate was also cultured and the resulting stromal cells were characterized. The surface markers and differentiation potential of these cells were also characteristic of MSC (data not shown). Counting MSC expanded from the filter retained aggregates and the filtrate from each sample after 10 days of culture showed that these two fractions contained 85%±5% and 15%±3% of total harvested MSC, respectively (Fig. 1K). Therefore, the cell aggregates are the main source of BM-MSC. It should be noticed that the filtrate also contained a few small cell aggregates passing from the filter that could be the origin of MSC in this fraction.

FIG. 1.

Native bone marrow (BM) contains three-dimensional multicellular complexes composed of both stromal and hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells. Isolation and in vitro characterization of BM cell complexes are schematically shown. To harvest total BM, the ends of femur bones were cut, they were inserted in an adapted microtube and centrifuged. The extracted BM was then applied to 20-μm cell strainers and the retained aggregates were cultured and the deriving cells were characterized (A). Microscopic observations immediately after isolation revealed compact three-dimensional cell complexes (B) that occasionally contained fat droplets (C) and in some cases were attached to blood vessels (D). These cell complexes attached to the surface and after 1 day formed colonies with fried egg morphology consisting of fibroblast-like cells in the margins and round cells in the center (E). Fat droplets were observed in the center of some colonies (F).Ten days after isolation, the emerged fibroblast-like stromal cells were moved to inductive medium to assess their plasticity. They could be differentiated to osteoblastic, adipogenic, and chondrogenic lineages as shown by Alizarin Red (G), Oil Red O (H), and Alcian Blue (I) staining, respectively. Cytofluorometric analysis showed that the surface markers of expanded fibroblast-like cells were compatible with the pattern of murine mesenchymal stem cells (MSC) (J). The filter-retained complexes and filtrate fractions were separately cultured and after 10 days, the isolated MSC were counted and characterized. This experiment showed that the filter-retained cell complexes are the main source of MSC in BM (K). To assess whether the central round cells belong to hematopoietic lineage, a few hours after isolation and seeding of BM cell complexes, the liquid medium was replaced by semisolid methylcellulose-based medium. After 14 days, on the top of most BM cell aggregate-derived colonies a mix of different colony-forming unit (CFUs) were evident (L). These CFUs belonged to different hematopoietic lineages (M-P) such as macrophage colony-forming unit (CFU-M), granulocyte macrophage colony-forming unit (CFU-GM), granulocyte colony-forming unit (CFU-G), and granulocyte, erythroid, macrophage, and megakaryocyte colony-forming unit (CFU-GEMM). To further confirm their hematopoietic identity, these colonies were detached and analyzed for the expression of surface markers. Representative flow cytometry graphs are shown (Q). Scale bars: G and K: 200 μm, others: 100 μm. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/scd

To see whether the isolated aggregates also contain hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPC), the liquid culture medium of the aggregate-derived colonies was replaced with semisolid methylcellulose-based medium specifically prepared for hematopoietic colony assay. In this medium, central round cells expanded rapidly and after 14 days, on the top or around almost all colonies derived from cell aggregates, a mix of different CFUs was evident (Fig. 1L). The CFUs belonged to different hematopoietic lineages (Fig. 1M–P). To confirm the derivation of hematopoietic lineages, cells were harvested from methylcellulose semi-solid medium and the expression of surface markers were analyzed by flow cytometry, which indicated that they were positive for different hematopoietic lineage markers including CD45 (64%±5%), Gr1 (51%±5%), Mac-1(44%±6%), B220 (20%±4%), and CD3 (4%±2%) (Fig. 1Q).

Taken together, these results indicate that the isolated BM cell complexes are specialized structures composed of both HSPC and their surrounding stromal cells, suggesting that they are niche-like units. Further experiments were performed to assess their functions and properties.

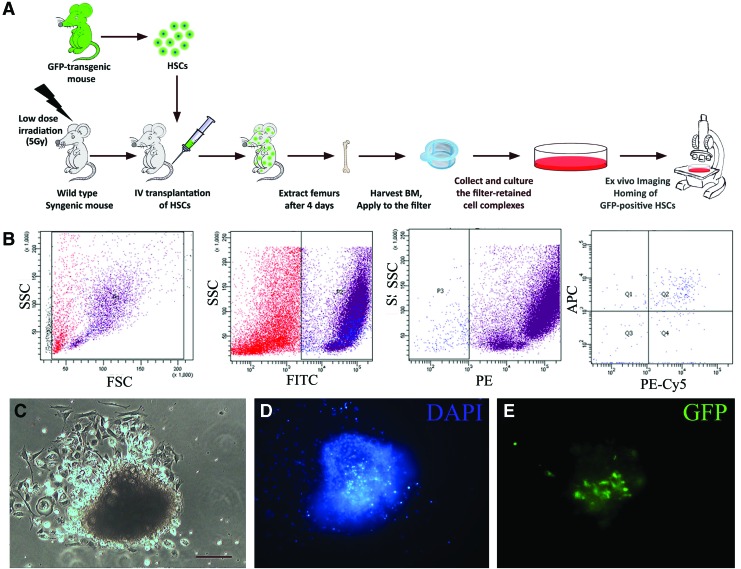

Niche-like units attract transplanted circulating HSC

The hematopoietic niche is known to actively attract circulating HSC [21]. To investigate whether the isolated cell aggregates show this feature, BM-HSC (c-Kit+/Sca-1+/Lin−) were isolated from GFP-transgenic mice and transplanted into low-dose irradiated wild-type mice. After 4 days, harvesting and inspection of BM filter-retained aggregates from the recipient mice showed that almost all aggregates contained GFP-positive transplanted cells (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Niche-like units attract circulating hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs). To investigate the potential of BM cell complexes to attract circulating HSCs, these cells were isolated from GFP-transgenic mice and transplanted to low-dose irradiated wild-type syngeneic mice through lateral tail veins. After 4 days, BM cell complexes were isolated from the recipients and investigated for the presence of transplanted cells (A). The transplanted cells were Lin-ckit+Sca-1+ and were sorted by FACS machine (B). Filter-retained cell complex-derived colonies were inspected by light microscopy (C) and fluorescent microscopy after DAPI staining (D). GFP-positive transplanted HSC could be detected in these structures (E). Scale bar: 100 μm. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/scd

Transplanted niche-like units not only reestablish the hematopoietic system but also recover BM stromal cells

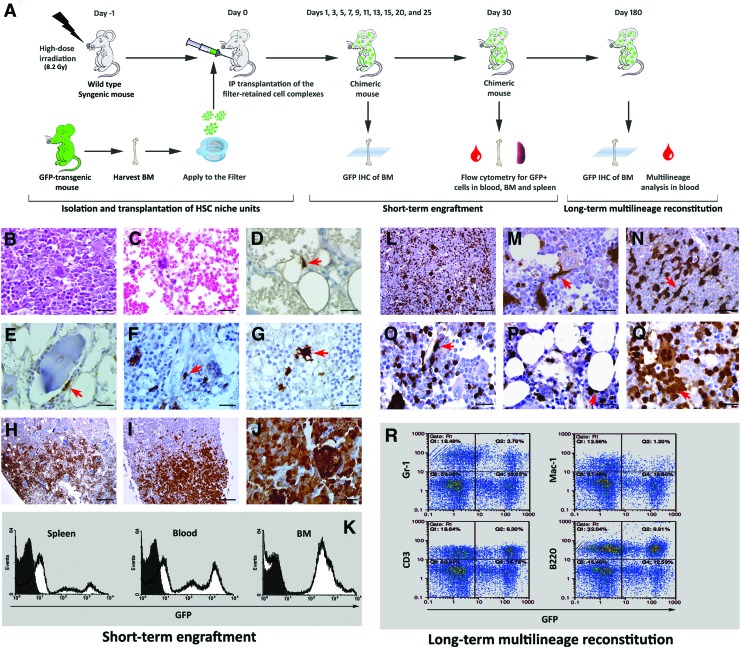

The potential of the isolated niche-like units for BM reconstitution was assessed by transplantation experiments (Fig. 3A). Wild-type mice were irradiated with 8.2 Gy before transplantation. This irradiation dose was selected based on preliminary experiments showing that it is sufficient for BM ablation. Indeed, 3 days after irradiation, the cellularity of BM was substantially reduced and only capillary networks, lakes of RBCs, and scattered megakaryocytes were evident in the marrow spaces (Fig. 3B, C). In addition, we could not harvest any filter-retained cell complex from BM of the irradiated mice and stromal cell populations could not be isolated and expanded at this time point (data not shown). After optimization of the irradiation dose for adequate BM ablation, transplantation experiments were performed and short-term and long-term engraftment were assessed.

FIG. 3.

Transplanted niche-like units reconstitute BM stromal cell and the hematopoietic system after transplantation to lethally irradiated recipients. Wild-type mice were irradiated and after 1 day transplanted with HSC niche-like units harvested from GFP-transgenic mice. BM of recipient mice was histologically studied at different time points from day 1 to 25 after transplantation. In addition, the chimerism of peripheral blood, BM and spleen was quantitatively assessed by flow cytometry at day 30. To investigate the long-lasting multilineage reconstitution, BM was histologically studied 6 months after transplantation. Also, the contribution of donor-derived cells in restoration of different hematopoietic lineages in peripheral blood was assessed by cytofluorometric analysis at this time (A). To validate the irradiation dose, BM sections were exposed to histological study 3 days after irradiation; H&E staining showed that compared to normal control (B), BM was totally ablated in the irradiated mice (C). After this preliminary experiment, transplantation was performed. Immunohistochemical analysis with HRP-conjugated anti-GFP antibody demonstrated the existence of few scattered donor-derived stromal cells as isolated spindle cells within fat spaces on day 5 (arrow) (D). On days 7 and 9, the number of GFP-positive cells increased and they were observed in different locations such as around bone trabecula (arrow) (E) and vessels (arrow) (F). In addition, some donor-derived dendritic-like cells were detected (G). Assessment of BM samples harvested on days 9–11 showed that GFP-positive hematopoietic islands were mainly localized in epiphyseal–metaphyseal junction (H). In the next days, these islands extended in both directions (I) and all the marrow space was occupied by GFP-positive cells in association with the recipient cells on day 25 (J). For examination of chimerism, the ratio of GFP-expressing donor cells in the blood, BM, and spleen of recipient mice was directly quantified 30 days after transplantation. Representative flow cytometry graphs are shown (K). Immunohistochemical study of BM samples at 6 months after transplantation demonstrated that GFP-positive cells were distributed in BM (L) and formed different cell types such as spindle-shaped cells (arrow) (M), dendritic-like cells (arrow) (N), pericytes (arrow) (O), fat cells (arrow) (P), and hematopoietic islands (arrow) and megakaryocytes (Q). Peripheral blood was stained with lineage-specific markers and assessed by flow cytometry (R). This assay showed that donor-derived cells contributed to formation of myeloid cells (Gr-1+), macrophages (Mac-1+), T-lymphocytes (CD3+), and B-cells (B220+). Scale bars: H: 500 μm I, L: 250 μm, others: 50 μm. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/scd

Immunohistochemical analysis for GFP expression revealed that one and three days after transplantation (days 1 and 3), GFP-positive cells were undetectable (data not shown). However, on day 5, a few scattered GFP-positive stromal cells emerged in BM as isolated spindle cells within fat spaces (Fig. 3D). On days 7 and 9 the number of these cells increased, and they appeared in different locations such as around bone trabecula (Fig. 3E) and vessels (Fig. 3F). Additionally, some of the GFP-positive cells displayed a dendritic-like appearance (Fig. 3G). Donor-derived GFP-positive hematopoietic islands appeared on days 9 and 11 and were predominantly localized in the epiphyseal–metaphyseal junction (Fig. 3H). These islands were enlarged and coalesced with each other (Fig. 3I) until, in association with the recipient cells, they filled the whole marrow space on day 25 and formed different cell types such as megakaryocyte-like cells (Fig. 3J).

In addition to the histological examination of BM, the appearance of GFP-positive cells in BM, spleen, and peripheral blood of the recipients was quantified by flow cytometry. One month after transplantation, 58%±9% of BM, 40%±7% of spleen, and 47%±8% of nucleated peripheral blood cells were GFP-positive and hence donor-derived (Fig. 3K).

To investigate the long-lasting reconstitution potential of transplanted niche-like units, BM was histologically examined after 6 months. Donor-derived GFP-positive cells with variable size were scattered in BM (Fig. 3L) and formed different cell types such as spindle-shaped cells (Fig. 3M), dendritic-like cells (Fig. 3N), pericytes (Fig. 3O), fat cells (Fig. 3P), and hematopoietic islands and megakaryocytes (Fig. 3Q).

To further show the reconstitution of BM stromal cells by HSC niche-like unit transplantation, the structures from GFP-transgenic mice were transplanted to irradiated wild-type syngeneic mice. After 4 months, BM was harvested from the recipients and filter-retained cell clamps were cultured. Twenty-four hours later, the clamps were inspected by fluorescent microscope. Green fluorescent stromal cells were evident in the periphery of the aggregate-derived colonies (Supplementary Fig. S1; Supplementary Data are available online at www.liebertpub.com/scd)

To further examine whether transplanted niche-like units are capable of long-lasting in vivo reconstitution of all blood lineages, peripheral blood samples were subjected to cytofuorometric analysis after staining for lineage-specific markers. This assessment showed that 17%–24% of myeloid cells (Gr-1-positive), 10%–19% of macrophages (Mac-1-positive), 25%–41% of T-lymphocytes (CD3-positive), and 31%–71% of B-cells (B220) were GFP-positive and so donor-derived (Fig. 3R).

Transplanted niche-like units generated ectopic lymph node-like structures in the abdominal cavity of some recipient mice

Irradiated female wild-type mice were intraperitoneally transplanted with BM cell aggregates from GFP-transgenic male mice. When we were exploring the abdominal cavity for adhesion bands and other potential side effects, we noted the appearance of small soft vascularized tissue within the omentum in some of the recipients at 2 weeks after transplantation (Supplementary Fig. S2A). Histological investigations revealed a lymphoid tissue mostly composed of small mononuclear lymphocytes mixed with plasma cells embedded in a reticular structure composed of spindle and oval shape cells. Scattered multinucleated cells and a few neutrophils were also seen. Around the mass, a thin capsule nourished by surrounding small and large vessels was formed (Supplementary Fig. S2B, C). This lymphoid tissue was chimeric, made of both GFP-positive and negative cells (Supplementary Fig. S2D, E). GFP-positive spindle cells were detected in the adventitia of small and large vessels but the endothelial cells were GFP-negative (Supplementary Fig. S2F). In the mice sacrificed 6 months after transplantation for long-lasting reconstitution studies, we did not grossly observe such a tissue in the abdominal cavity.

Discussion

In this study we have shown the existence of cell aggregates in murine BM that can be isolated simply by filtration. These complexes are composed of entwined HSPC and multipotent stromal stem cells and have the potential to actively attract circulating HSC. When intraperitoneally transplanted into irradiated mice, they have the ability to sustain long-lasting multilineage hematopoiesis and also BM microenvironment reconstitution. They can also give rise to lymph node-like structures on the omentum of the recipients. Taken together, these results suggest that the above mentioned BM cell complexes have the features of HSC niche units.

Although the existence of cell aggregates as native elements of BM has been previously reported by several groups using variable nomenclature, the exact identity of these aggregates remains unknown. Blazsek et al. noted low-density multicellular spheroids floating on the surface of BM samples. These structures were later shown to be actually composed of stromal and hematopoietic progenitor cells. Although their findings were only based on in vitro studies, they proposed that these particles are the fundamental units of primary hematopoiesis, and so named them hematons [22–24]. These so-called hematons can be related to the low-density fat droplet containing niche-like units described in our study. Additionally, Nolta et al. and Dao et al. described bony spicules as high density particles in BM that can be isolated by gravity sedimentation and are rich in MSC [25,26]. With a cell-strainer with the pore size of 80 μm, Jin et al. could isolate particles, which were named BM debris and were considered a novel rich source of MSC [27]. However, these later groups did not report the presence of hematopoietic cells in the bony spicules or BM debris. In this study, to preserve the integrity of BM particles and also to avoid contamination with bony trabecula pieces, we used centrifugation with adapted tubes instead of flushing method for BM isolation. However, rarely we noted the attachment of small bone pieces to the BM particles-derived colonies that could be related to the described bony spicules or may represent osteoblastic niches. By microscopic inspection of BM sections, Wang et al. have recently described clonally expanding vessel-associated compartments in the periphery of the adult BM cavity. They found that these units that have been named hemospheres are composed of hematopoietic, mesenchymal, and endothelial cells [28]. Further studies are required to compare BM particles described by us and these investigators.

One of the main findings of the present study is that, besides containing HSPC, the isolated murine BM cell complexes give rise to MSC when cultured in vitro, which is in line with our previous work on human BM cell complexes [29]. It has been recognized that the physiological role of MSC in BM is the formation of the HSC niche [8]. MSC can give rise to different types of niche stromal cells, providing a supportive microenvironment for hematopoietic cells that are in different levels of lineage commitment [7]. Notably, our data indicate that a large fraction of BM-MSC localizes in the cell aggregates, which is in contrast to the common belief that these cells exist as single suspension cells in BM samples [30]. This notion challenges the utilization of CFU-F assay, which is conventionally used for counting of primary MSC in BM sample, since based on our data each fibroblast-like colony does not represent a primary single cell but is originated from one HSPC niche-like unit that includes several primary MSC. Therefore, several studies that have suggested, using this method, that the frequency of MSC is as low as 10–50 per 1×106 BM nucleated cells [31–35] underestimate the actual rate.

We noted that some isolated cell complexes were associated with vascular structures. This is in line with the previous notions that a hallmark of mammalian niches is their proximity to the vascular system [36]. Blood vessels are important not only for oxygenation and nutrition of niche elements but also for providing systemic communications of stem cells. Specially, the interaction between the HSC niche and vessels is not surprising as endothelium and HSC arise from a common precursor, the hemangioblast [37]. We also noted that some niche-like units contained fat droplets. Further studies are required to determine the biologic relevance of these droplets. However, based on a recent study showing that BM adipocytes are negative regulators of hematopoiesis, [38] it could be proposed that fat droplet-containing cell complexes represent inactive HSC niches. These niches possibly will activate in response to injury and stress and may function as a reservoir of the hematopoietic system [39].

Isolation of niche-like units from BM after transplantation of GFP-positive HSC showed that these units can actively attract circulating HSC, which is an indispensable function of niches. The influence of stem cell-niche interactions has been well documented, but methods to study these interactions are not extensively developed. The assay used in this study allows to dynamically study in real time the behavior of HSC and its interaction with niche in an ex vivo setting. Although live-animal imaging [40] and ex vivo techniques [21] have been previously used to study HSC-niche interactions at the level of whole BM, our analysis permits these studies at the level of single niche units.

Our histological examinations showed a significant decrease in BM cellularity a few days after irradiation, which is in line with a recent study showing that the BM microenvironment is destroyed after high-dose total body irradiation [41]. It has been shown that in BM transplantation, niches must be made available for successful HSC engraftment, [42] and one of the advantages of the “niche-like unit transplantation” strategy is the contribution of transplanted niche stromal cells in the recovery and replacement of destroyed recipient BM niches following irradiation. Besides, “niche-like unit transplantation” may be clinically used for disorders in which niche dysfunction contributes in the pathogenesis, such as myelodysplastic disease [43,44].

In addition to restoration of BM stromal cells, our data imply that the transplanted niche-like units have the capacity to reestablish multilineage hematopoiesis in lethally irradiated recipients after 6 months, indicating that the transplanted niche-like units contain primitive self-renewing HSC. However, it remains unknown whether one pluripotent stem cell in the transplanted niche units is the origin of both stromal and hematopoietic lineages or if they are derived from two distinct stem cell types. Whatever the case, it could be suggested that these structures are the source of both stromal and hematopoietic components and so are the basic elements of BM. This concept has been previously considered for other tissues; the intestinal crypts stem cells [45] and hair follicle stem cells [46] associated with their niches are shown to play a role as fundamental units of these tissues. Although in vitro modeling of the HSC niche has been tried by some researchers, it has not been fully successful due to the complexity of these units [47] and therefore, isolation of HSPC in the context of their native intact niches as described here, provides the fundamental units for BM tissue engineering.

Interestingly, our histopathological findings on reconstitution of the hematopoietic system revealed that donor-derived hematopoietic islands first appeared in epiphyseal–metaphyseal junctions. This biased homing was previously noted by other investigators [48] and was attributed to the strong expression of SDF-1, a potent chemotactic factor, in this area following irradiation [21]. It is interesting to note that growth plates are near epiphyseal–metaphyseal junctions and therefore, it seems that this area is rich in different types of stem cells.

Although niche-like units were transplanted intraperitoneally, they extensively migrated to the BM. It is unlikely that the whole cell aggregates transplanted in the peritoneal cavity migrate to the BM space, so that possibly different cell types released from these complexes participate in the reconstitution of BM stromal cells. An alternative hypothesis involves migration of a multipotent stem cell from transplanted niche-like units to BM and differentiation to BM stromal cells. In this case, while some of the transplanted cells migrate to the BM early after transplantation some others that could not migrate cooperate for the formation of a lymphoid tissue. The generation of lymphoid structures on the omentum of recipients is not unexpected, as it can be a physiological response to the cytoreduction of the lymphoid system following total body irradiation. This observation indicates the flexibility of HSC niche-like units for generation of lymphoid tissues.

Finally, it should be mentioned that in our experiments, we frequently observed the formation of adhesion bands around the intestine and other visceral organs of the recipient mice. This side effect may limit the future clinical application of this strategy. A possible solution to this problem comes from the work of some investigators who have shown the feasibility of intra-BM delivery as a new route for BM transplantation [49,50]. We tried to assess intra-BM transplantation of niche-like units in mice but due to the need for wide diameter needles for injection of cell complexes and the small size of mouse bones, our attempts were unsuccessful. Therefore, the feasibility of this method remains to be investigated in large animals before moving to clinical trials.

In conclusion, here we provided evidences that BM contains cell complexes with some properties described for HSC niches. Further studies are definitely required to determine the actual identity of these structures. These complexes are filtered and discarded during the routine BM transplantation procedures. However, our data indicate that they can efficiently reconstitute hematopoietic system after irradiation. Therefore, upon development of an appropriate transplantation route, they might be delivered to the recipient in association with single HSC to enhance the transplantation outcome and overcome some limitations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr. Minoo Saeidi for preparing the schematic designs. This study was supported by grants from Tarbiat Modares University and Stem Cell Technology Research Center, Tehran, Iran.

Author Disclosure Statement

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Schofield R. The relationship between the spleen colony-forming cell and the haemopoietic stem cell. Blood Cells. 1978;4:7–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wilson A. Trumpp A. Bone-marrow haematopoietic-stem-cell niches. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6:93–106. doi: 10.1038/nri1779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang J. Niu C. Ye L. Huang H. He X. Tong WG. Ross J. Haug J. Johnson T, et al. Identification of the haematopoietic stem cell niche and control of the niche size. Nature. 2003;425:836–841. doi: 10.1038/nature02041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kiel MJ. Yilmaz OH. Iwashita T. Terhorst C. Morrison SJ. SLAM family receptors distinguish hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells and reveal endothelial niches for stem cells. Cell. 2005;121:1109–1121. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Calvi LM. Adams GB. Weibrecht KW. Weber JM. Olson DP. Knight MC. Martin RP. Schipani E. Divieti P, et al. Osteoblastic cells regulate the haematopoietic stem cell niche. Nature. 2003;425:841–846. doi: 10.1038/nature02040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mendez-Ferrer S. Michurina TV. Ferraro F. Mazloom AR. Macarthur BD. Lira SA. Scadden DT. Ma'ayan A. Enikolopov GN. Frenette PS. Mesenchymal and haematopoietic stem cells form a unique bone marrow niche. Nature. 2010;466:829–834. doi: 10.1038/nature09262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Muguruma Y. Yahata T. Miyatake H. Sato T. Uno T. Itoh J. Kato S. Ito M. Hotta T. Ando K. Reconstitution of the functional human hematopoietic microenvironment derived from human mesenchymal stem cells in the murine bone marrow compartment. Blood. 2006;107:1878–1887. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-06-2211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Uccelli A. Moretta L. Pistoia V. Mesenchymal stem cells in health and disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8:726–736. doi: 10.1038/nri2395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jones DL. Wagers AJ. No place like home: anatomy and function of the stem cell niche. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9:11–21. doi: 10.1038/nrm2319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Purton LE. Scadden DT. The hematopoietic stem cell niche. StemBook. 2008. [PubMed]

- 11.Ahmadbeigi N. Soleimani M. Gheisari Y. Vasei M. Amanpour S. Bagherizadeh I. Shariati SA. Azadmanesh K. Amini S, et al. Dormant phase and multinuclear cells: two key phenomena in early culture of murine bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cells Dev. 2011;20:1337–1347. doi: 10.1089/scd.2010.0266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Denning-Kendall P. Singha S. Bradley B. Hows J. Cytokine expansion culture of cord blood CD34+ cells induces marked and sustained changes in adhesion receptor and CXCR4 expressions. Stem Cells. 2003;21:61–70. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.21-1-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gerdes AJ. Storb R. The repopulation of irradiated bone marrow by the infusion of stored autologous marrow. Radiology. 1970;94:441–445. doi: 10.1148/94.2.441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lawler M. Locasciulli A. Longoni D. Schiro R. McCann SR. Leukaemic transformation of donor cells in a patient receiving a second allogeneic bone marrow transplant for severe aplastic anaemia. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2002;29:453–456. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1703372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lazarus HM. Koc ON. Devine SM. Curtin P. Maziarz RT. Holland HK. Shpall EJ. McCarthy P. Atkinson K, et al. Cotransplantation of HLA-identical sibling culture-expanded mesenchymal stem cells and hematopoietic stem cells in hematologic malignancy patients. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2005;11:389–398. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2005.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Le Blanc K. Frassoni F. Ball L. Locatelli F. Roelofs H. Lewis I. Lanino E. Sundberg B. Bernardo ME, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells for treatment of steroid-resistant, severe, acute graft-versus-host disease: a phase II study. Lancet. 2008;371:1579–1586. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60690-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ball LM. Bernardo ME. Roelofs H. Lankester A. Cometa A. Egeler RM. Locatelli F. Fibbe WE. Cotransplantation of ex vivo expanded mesenchymal stem cells accelerates lymphocyte recovery and may reduce the risk of graft failure in haploidentical hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation. Blood. 2007;110:2764–2767. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-04-087056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mouiseddine M. Francois S. Semont A. Sache A. Allenet B. Mathieu N. Frick J. Thierry D. Chapel A. Human mesenchymal stem cells home specifically to radiation-injured tissues in a non-obese diabetes/severe combined immunodeficiency mouse model. Br J Radiol. 2007;80(Spec No 1):S49–S55. doi: 10.1259/bjr/25927054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Peister A. Mellad JA. Larson BL. Hall BM. Gibson LF. Prockop DJ. Adult stem cells from bone marrow (MSCs) isolated from different strains of inbred mice vary in surface epitopes, rates of proliferation, and differentiation potential. Blood. 2004;103:1662–1668. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-09-3070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gheisari Y. Azadmanesh K. Ahmadbeigi N. Nassiri SM. Golestaneh AF. Naderi M. Vasei M. Arefian E. Mirab-Samiee S, et al. Genetic modification of mesenchymal stem cells to overexpress CXCR4 and CXCR7 does not improve the homing and therapeutic potentials of these cells in experimental acute kidney injury. Stem Cells Dev. 2012;21:2969–2980. doi: 10.1089/scd.2011.0588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xie Y. Yin T. Wiegraebe W. He XC. Miller D. Stark D. Perko K. Alexander R. Schwartz J, et al. Detection of functional haematopoietic stem cell niche using real-time imaging. Nature. 2009;457:97–101. doi: 10.1038/nature07639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Blazsek I. Chagraoui J. Peault B. Ontogenic emergence of the hematon, a morphogenetic stromal unit that supports multipotential hematopoietic progenitors in mouse bone marrow. Blood. 2000;96:3763–3771. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Blazsek I. Liu XH. Anjo A. Quittet P. Comisso M. Kim-Triana B. Misset JL. The hematon, a morphogenetic functional complex in mammalian bone marrow, involves erythroblastic islands and granulocytic cobblestones. Exp Hematol. 1995;23:309–319. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Blazsek I. Misset JL. Benavides M. Comisso M. Ribaud P. Mathe G. Hematon, a multicellular functional unit in normal human bone marrow: structural organization, hemopoietic activity, and its relationship to myelodysplasia and myeloid leukemias. Exp Hematol. 1990;18:259–265. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nolta JA. Hanley MB. Kohn DB. Sustained human hematopoiesis in immunodeficient mice by cotransplantation of marrow stroma expressing human interleukin-3: analysis of gene transduction of long-lived progenitors. Blood. 1994;83:3041–3051. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dao MA. Pepper KA. Nolta JA. Long-term cytokine production from engineered primary human stromal cells influences human hematopoiesis in an in vivo xenograft model. Stem Cells. 1997;15:443–454. doi: 10.1002/stem.150443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jin JD. Wang HX. Xiao FJ. Wang JS. Lou X. Hu LD. Wang LS. Guo ZK. A novel rich source of human mesenchymal stem cells from the debris of bone marrow samples. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;376:191–195. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.08.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang L. Benedito R. Bixel MG. Zeuschner D. Stehling M. Savendahl L. Haigh JJ. Snippert H. Clevers H, et al. Identification of a clonally expanding haematopoietic compartment in bone marrow. EMBO J. 2013;32:219–230. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2012.308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ahmadbeigi N. Soleimani M. Babaeijandaghi F. Mortazavi Y. Gheisari Y. Vasei M. Azadmanesh K. Rostami S. Shafiee A. Nardi NB. The aggregate nature of human mesenchymal stromal cells in native bone marrow. Cytotherapy. 2012;14:917–924. doi: 10.3109/14653249.2012.689426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Castro-Malaspina H. Gay RE. Resnick G. Kapoor N. Meyers P. Chiarieri D. McKenzie S. Broxmeyer HE. Moore MA. Characterization of human bone marrow fibroblast colony-forming cells (CFU-F) and their progeny. Blood. 1980;56:289–301. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bruder SP. Fink DJ. Caplan AI. Mesenchymal stem cells in bone development, bone repair, and skeletal regeneration therapy. J Cell Biochem. 1994;56:283–294. doi: 10.1002/jcb.240560809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Campagnoli C. Roberts IA. Kumar S. Bennett PR. Bellantuono I. Fisk NM. Identification of mesenchymal stem/progenitor cells in human first-trimester fetal blood, liver, and bone marrow. Blood. 2001;98:2396–2402. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.8.2396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hernigou P. Poignard A. Beaujean F. Rouard H. Percutaneous autologous bone-marrow grafting for nonunions. Influence of the number and concentration of progenitor cells. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87:1430–1437. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.D.02215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Prockop DJ. Azizi SA. Colter D. Digirolamo C. Kopen G. Phinney DG. Potential use of stem cells from bone marrow to repair the extracellular matrix and the central nervous system. Biochem Soc Trans. 2000;28:341–345. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wexler SA. Donaldson C. Denning-Kendall P. Rice C. Bradley B. Hows JM. Adult bone marrow is a rich source of human mesenchymal “stem” cells but umbilical cord and mobilized adult blood are not. Br J Haematol. 2003;121:368–374. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2003.04284.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Carrion B. Huang CP. Ghajar CM. Kachgal S. Kniazeva E. Jeon NL. Putnam AJ. Recreating the perivascular niche ex vivo using a microfluidic approach. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2010;107:1020–1028. doi: 10.1002/bit.22891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Choi K. Kennedy M. Kazarov A. Papadimitriou JC. Keller G. A common precursor for hematopoietic and endothelial cells. Development. 1998;125:725–732. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.4.725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Naveiras O. Nardi V. Wenzel PL. Hauschka PV. Fahey F. Daley GQ. Bone-marrow adipocytes as negative regulators of the haematopoietic microenvironment. Nature. 2009;460:259–263. doi: 10.1038/nature08099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ohlstein B. Kai T. Decotto E. Spradling A. The stem cell niche: theme and variations. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2004;16:693–699. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2004.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lo Celso C. Fleming HE. Wu JW. Zhao CX. Miake-Lye S. Fujisaki J. Cote D. Rowe DW. Lin CP. Scadden DT. Live-animal tracking of individual haematopoietic stem/progenitor cells in their niche. Nature. 2009;457:92–96. doi: 10.1038/nature07434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dominici M. Rasini V. Bussolari R. Chen X. Hofmann TJ. Spano C. Bernabei D. Veronesi E. Bertoni F, et al. Restoration and reversible expansion of the osteoblastic hematopoietic stem cell niche after marrow radioablation. Blood. 2009;114:2333–2343. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-10-183459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Czechowicz A. Kraft D. Weissman IL. Bhattacharya D. Efficient transplantation via antibody-based clearance of hematopoietic stem cell niches. Science. 2007;318:1296–1299. doi: 10.1126/science.1149726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Corre J. Mahtouk K. Attal M. Gadelorge M. Huynh A. Fleury-Cappellesso S. Danho C. Laharrague P. Klein B. Reme T. Bourin P. Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells are abnormal in multiple myeloma. Leukemia. 2007;21:1079–1088. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Raaijmakers MH. Mukherjee S. Guo S. Zhang S. Kobayashi T. Schoonmaker JA. Ebert BL. Al-Shahrour F. Hasserjian RP, et al. Bone progenitor dysfunction induces myelodysplasia and secondary leukaemia. Nature. 2010;464:852–857. doi: 10.1038/nature08851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Potten CS. Loeffler M. Stem cells: attributes, cycles, spirals, pitfalls and uncertainties. Lessons for and from the crypt. Development. 1990;110:1001–1020. doi: 10.1242/dev.110.4.1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Levy V. Lindon C. Harfe BD. Morgan BA. Distinct stem cell populations regenerate the follicle and interfollicular epidermis. Dev Cell. 2005;9:855–861. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Di Maggio N. Piccinini E. Jaworski M. Trumpp A. Wendt DJ. Martin I. Toward modeling the bone marrow niche using scaffold-based 3D culture systems. Biomaterials. 2011;32:321–329. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.09.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yoshimoto M. Shinohara T. Heike T. Shiota M. Kanatsu-Shinohara M. Nakahata T. Direct visualization of transplanted hematopoietic cell reconstitution in intact mouse organs indicates the presence of a niche. Exp Hematol. 2003;31:733–740. doi: 10.1016/s0301-472x(03)00108-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ikehara S. Intra-bone marrow-bone marrow transplantation: a new strategy for treatment of stem cell disorders. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2005;1051:626–634. doi: 10.1196/annals.1361.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kushida T. Inaba M. Hisha H. Ichioka N. Esumi T. Ogawa R. Iida H. Ikehara S. Intra-bone marrow injection of allogeneic bone marrow cells: a powerful new strategy for treatment of intractable autoimmune diseases in MRL/lpr mice. Blood. 2001;97:3292–3299. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.10.3292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.