Abstract

In this study, application of various concentrations (0.025%, 0.05% and 0.075%) of Carum copticum essential oil (EO) were examined on oxidative stability of sunflower oil and there were compared to Butylated hydroxyanisole (BHA) and butylated hydroxytoluene (BHT) during storage at 37 and 47 °C. The main compounds of EO were identified as thymol (50.07%), γ- terpinene (23.92%) and p-cymene (22.9%). Peroxide value (PV), anisidine value (AnV) and thiobarbituric acid (TBA) value measurement in sunflower oil showed that all concentrations of EO had antioxidant effect in comparison to BHA and BHT. Samples added with EO at 0.075% were the most stable during storage at both temperatures (P < 0.05). Furthermore, Totox value, antioxidant activity (AA), stabilization factor (F) and antioxidant power (AOP) determination confirmed efficacy of this EO as antioxidant in sunflower oil. EO also was able to reduce the stable free radical 2, 2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) with a 50% inhibition concentration (IC50) of 20.3 ± 0.9 μg/mL. Therefore, the results indicate that EO could be used as a natural antioxidant in food lipids.

Keywords: Carum copticum, Essential oil, Sunflower oil, Antioxidant activity

Introduction

Sunflower oil is greatly used for food applications such as cooking oil and ingredients in bakery products. This oil is very sustainable to oxidation especially when submit at high temperature. Oxidation deterioration occurring in vegetable oils is unpleasant process that causes quality and nutritional losses and because it produces toxic compounds such as alcohols, aldehydes and ketones (Schaich 2005). Addition of antioxidants is required to preserve edible oils against oxidation (Sanhueza et al. 2000). Antioxidants could affect oxidation process by scavenging free radicals and oxygen, chelating the metals, reducing hydroperoxides into stable compounds and interacting synergistically with other reducing compounds. Among the synthetic antioxidants, BHA, BHT and tert-butyl hydroquinone (TBHQ) are widely used in food industry (Hamama and Nawar 1991; Sanhueza et al. 2000). However, some studies reported synthetic antioxidants like BHA and BHT may have side effects and carcinogenic (Labrador et al. 2006; Sharif Ali et al. 2008). The substitution of synthetic antioxidants by natural antioxidants may have some benefits, due to health effects and consumer perception (Moure et al. 2001; Suhaj 2006; Sharif Ali et al. 2008; Wojdylo et al. 2007; Liu et al. 2008). Plant materials contain many compounds with antioxidant activity. Various herbs and spices have been studied as sources of possibly safe natural antioxidants for the food applications (Yanishlieva and Marenova 2001).

Carum copticum is an aromatic, grassy, annual plant which grows in the east of India, Iran and Pakistan with white and small flowers and brownish seeds (Boskabady and Shaikhi 2000). Zenyan is the Persian name for seeds of C. copticum and were used for its therapeutic effects such as antivomiting, analgesic and anti-asthma (Zargari 1990). Traditionally, the water extract of Zenyan is generally used to relieve the symptoms of flue in children. In addition, the ripening seeds of this plant essential oil was reported to have antibacterial activity against Salmonella thyphimorium, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Entero-pathogenic Escherichia coli, and Staphylococcus aureus (Goudarzi et al. 2011). Zenyan essential oil also is rich in monoterpenes like thymol and is mostly used as an antiseptic agent as well as a drug component in medicine (Lateef et al. 2006).

The aim of the present study was to evaluate the antioxidant activity of various concentrations of EO in vitro and in sunflower oil during storage.

Materials and methods

Plant material and chemicals

C. copticum seeds were collected from the suburb of Kazerun city, Fars province, Iran. The species was identified and authenticated by A.R. Khosravi, a plant taxonomist, at Shiraz University, Herbarium, Shiraz, Iran. Voucher specimen (no. 24985) has been deposited in the herbarium.

Refined, bleached, and deodorized sunflower oil with no addetives was purchased from a local Nargess Oil Company.

Chemicals such as methanol, acetic acid, chloroform, sodium iodide, sodium thiosulfate, thiobarbituric acid, 1-butanol, iso-octane and p-anisidine were obtained from Merck (Darmstadt, Germany). DPPH, BHT and BHA were purchased from Sigma Chemical Company (Sigma-Aldrich GmbH, Sternheim, Germany).

Extraction of EO

Dried matured seeds of the plant (20 g, 8% moisture) were hydrodistillated for 2.5 h, using an all-glass Clevenger-type apparatus, according to the method recommended by the British Pharmacopoeia (1988). EO was dried over anhydrous sodium sulphate and stored in sealed vials at 4 °C until used.

EO analysis

The EO was analysed by GC-MS. The analysis was carried out on a Thermoquest- Finnigan Trace GC-MS instrument equipped with a DB-5 fused silica column (60 m× 0.25 mm i.d., film thickness 0.25 μm). The oven temperature was programmed to increase from 60 to 250 °C at a rate of 4 °C/min and finally held for 10 min; transfer line temperature was 250 °C. Helium was used as the carrier gas at a flow rate of 1.1 mL/min with a split ratio equal to 1/50. The quadrupole mass spectrometer was scanned over the 35–465 amu with an ionising voltage of 70 eV and an ionisation current of 150 mA.

GC-FID analyses of the oil were conducted using a Thermoquest-Finnigan instrument equipped with a DB-5 fused silica column (60 m× 0.25 mm i.d., film thickness 0.25 μm). Nitrogen was used as the carrier gas at the continuous flow of 1.1 mL/min; the split ratio was the same as for GC-MS. The oven temperature was raised from 60 to 250 °C at a rate of 4 °C/min and held for 10 min. The injector and detector (FID) temperatures were kept at 250 and 280 °C, respectively. Semi quantitative data were obtained from FID area percentages without the use of correction factors.

Retention indices (RI) were calculated by using retention times of n-alkanes (C6–C24) that were injected after the oil at the same temperature and conditions. Compounds were identified by comparison of their RI with those reported in the literature (Adams 2007) and their mass spectrum was compared with the Wiley Library (Wiley 7.0).

DPPH assay

The radical scavenging capacity of essential oil from C. copticum for DPPH was monitored according to the method described by Burits and Bucar (2000). Fifty microlitres of different concentrations of the essential oil samples in methanol (15, 25, 35, 45 and 55 μg/mL) were added to 5 ml of a 0.004% methanol solution of DPPH. After a 30 min incubation period at room temperature under dark condition, the absorbance of the samples was read against a blank at 517 nm. Inhibition of free radical DPPH in percent (I%) was calculated in following way:

|

where A blank is the absorbance of the control reaction (containing all reagent except the test compound), and A sample is the absorbance of the test compound. EO concentration providing 50% inhibition (IC50) was calculated from the graph plotting inhibition percentage against EO concentration. BHT was used as a control and all tests were carried out in triplicates.

Preparation of sunflower oil samples

EO at 0.025%, 0.05% and 0.075%, BHA and BHT at 0.01% and 0.02% concentrations separately were added to sunflower oil in open polyethylene terephthalate (PET) packaging. Then samples were stored during 14 days at 37 and 47 °C in oven with no air circulation under dark condition. At each sampling time, samples were removed from storage, at random, and were subjected to chemical analysis.

Chemical analyses of sunflower oil samples

PV, AnV and TBA value analyses were performed according to the American Oil Chemist’s Society (1998). PV was measured by treating a solution of sunflower oil (5 ± 0.05 g) in 30 mL acetic acid-chloroform with 0.5 mL saturated potassium iodide solution and titration with 0.1 N sodium thiosulfate. Determination of AnV was done by reading the absorbance of a solution of sunflower oil (0.5–4 ± 0.001 g) in 25 mL isooctane, treated with 1 mL p-anisidine reagent at 350 nm using solvent with p-anisidine reagent as blank in the reference cuvette. Measurement of TBA value was done by heating a 5 mL aliquot of a solution of sample (50–200 mg) in 25 ml 1-butanol with 5 ml TBA reagent at 95 °C for 120 min and reading the absorbance at 530 nm using distilled water in the reference cuvette. Determinations were carried out in triplicates.

Determination of Totox index, Antioxidant activity (AA), Stabilization factor (F) and Antioxidant power (AOP)

The totox value was determined from the equation (Rossel 1989):

|

AA was calculated from the equation (Wanasandara and Shahidi 2005):

|

where t AH is time taken by sunflower oil to reach the predetermined level of oxidation (20 meq/kg oil) based on the PV test.

t CONTROL is the time for control to reach the same level of oxidation.

[AH] is the concentration of antioxidant in proper units.

The effectiveness of all tested antioxidants was express as the F value (Hras et al. 2000).

|

where IP inh is the induction period of sunflower oil sample with inhibitor and IP 0 is the induction period of control.

AOP was calculated from the formula (Silva et al. 2001):

|

where IP c is the induction period of control and IP s is the induction period of sunflower oil sample with additives.

Statistical analyses

The data were statistically analyzed by analysis of variance (ANOVA) and compared means by Duncan’s multiple range post hoc test using the SPSS statistical software package (SPSS 15.0 for Windows statistical software package).

Results and discussion

EO composition

The yield of the essential oil of representative C. copticum was 2.1% (v/w). GC-MS analysis of the EO resulted in the identifications of 18 compounds, representing the 99.54% of the oils.

The percentages of each component of EO were quantified by peak area using the FID detector. Percentages of components of the EO are summarized in Table 1. As the results show, the main components of the EO are thymol (50.07%), γ- terpinene (23.92%) and p-cymene (22.9%).

Table 1.

Essential oil composition of carum copticum identified by gas chromatography-mass spectroscopy

| Component | Retention index | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| α- Thujen | 931 | 0.32 |

| α –Pinene | 941 | 0.11 |

| Sabinene | 979 | 0.19 |

| β-Pinene | 986 | 0.42 |

| Myrcene | 990 | 0.51 |

| α—Terpinene | 1022 | 0.02 |

| p-Cymene | 1030 | 22.9 |

| 1,8- Cineole | 1038 | 0.5 |

| Ocimene | 1047 | 0.04 |

| γ- Terpinene | 1064 | 23.92 |

| cis-Sabinene hydrate | 1072 | 0.04 |

| Linalool | 1098 | 0.01 |

| trans-Sabinene hydrate | 1105 | 0.03 |

| Cyclocitral | 1171 | 0.13 |

| Terpinen-4-ol | 1185 | 0.11 |

| α –Terpineol | 1198 | 0.09 |

| Thymol | 1295 | 50.07 |

| Carvacrol | 1301 | 0.13 |

| Sum | 99.54 |

DPPH assay

The DPPH test is a nonenzymatic method frequently used for measurement of antioxidant activity of phenolic compounds (Burits and Bucar 2000). In the present study, free radical scavenging activity of EO was determined to be 20.3 ± 0.9 μg/mL whereas IC50 value of BHT was 18.1 ± 0.6 μg/mL. In the DPPH assay, EO exhibited remarkable antioxidant activity. It seems that activity of the EO associated with high content of thymol. Moreover, this component is more efficient in preventing conjugating dienes than in free radical scavenging (Sharififar et al. 2007). The DPPH test often related poorly with the capability of compounds to prevent lipid oxidation because this test do not account for factors such as the physical situation of antioxidant and environmental conditions (Decker et al. 2005).

Antioxidant effects of EO in sunflower oil

Antioxidant activity of the EO in sunflower oil was evaluated during storage.

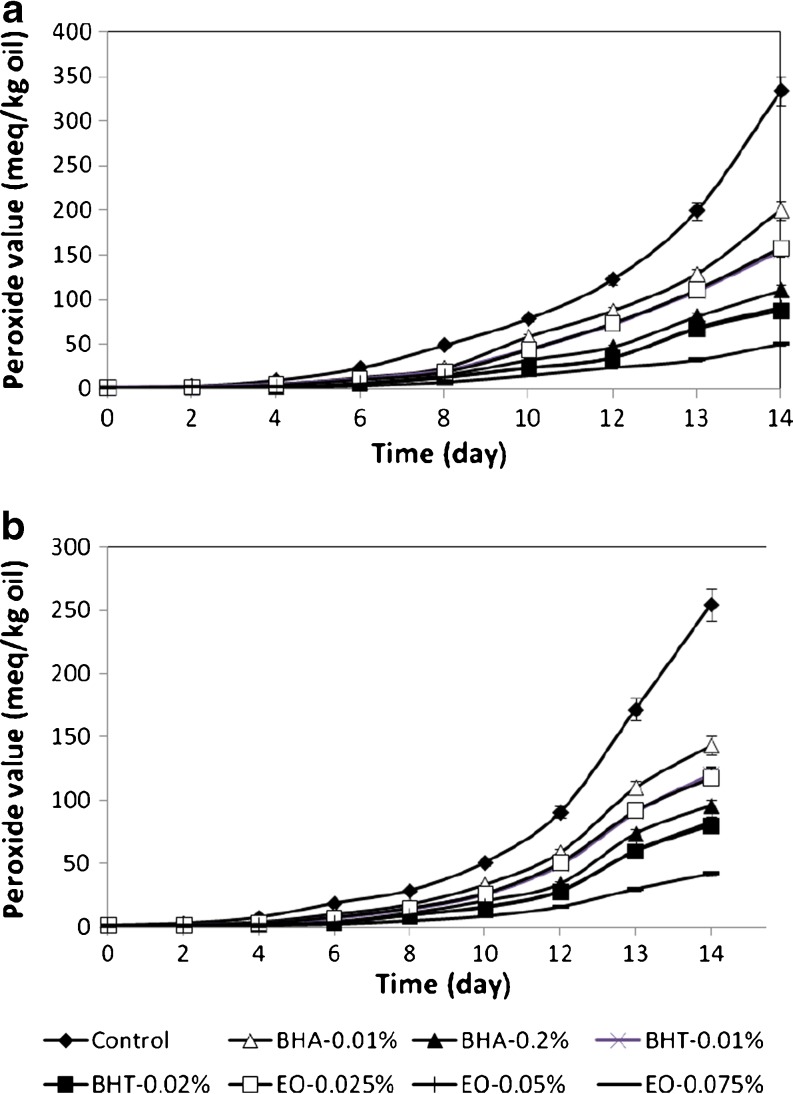

The PVs of sunflower oil with added antioxidants at 37 and 47 °C are presented in Figure 1. Result of PV indicated that all concentrations of EO significantly retarded the hydroperoxide formation of sunflower oil samples during storage.

Fig. 1.

PV of sunflower oil without antioxidant and with EO, BHA and BHT during storage at 47 (a) and 37 °C (b)

At 37 and 47 °C, significant differences in PV of sunflower oil with 0.075% EO in comparison to the other samples were observed. Whereas the means comparison of the PV of sunflower oil with 0.05% EO and BHT at 0.02% were not significantly different. Oil samples with EO at 0.05% showed lower PV than samples with 0.02% BHA during storage at two temperatures (P < 0.05).

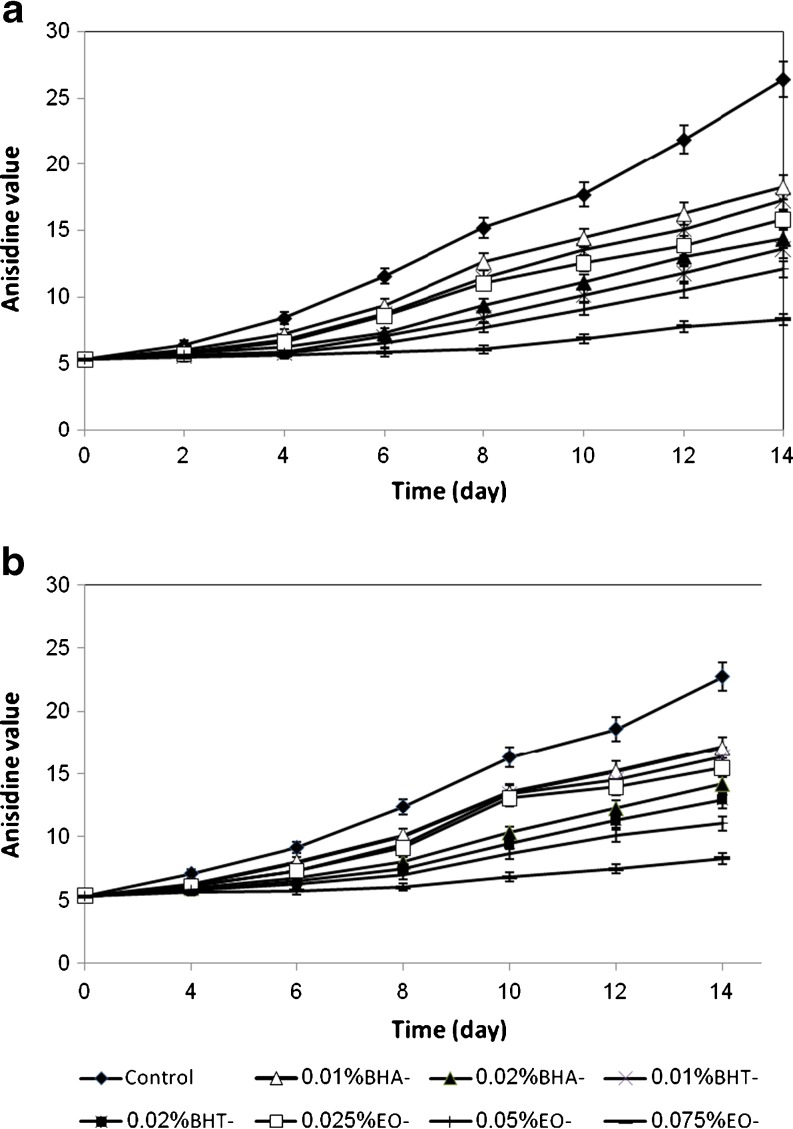

The AnV test is frequently used for the detection of secondary lipid oxidation (Rossel 1989). Result of this test (Fig. 2) showed all concentrations of EO decrease AnV during storage (P < 0.05). At two temperatures, sunflower oil was significantly less oxidatively stable as measured by secondary compounds formation when synthetic antioxidants were added rather than EO. EO at 0.075% was significantly more active than other samples. Sunflower oil samples with EO at 0.05% were significantly lower AnV than synthetic antioxidants during storage at 37 and 47 °C.

Fig. 2.

AnV of sunflower oil without antioxidant and with EO, BHA and BHT during storage at 47 (a) and 37 °C (b)

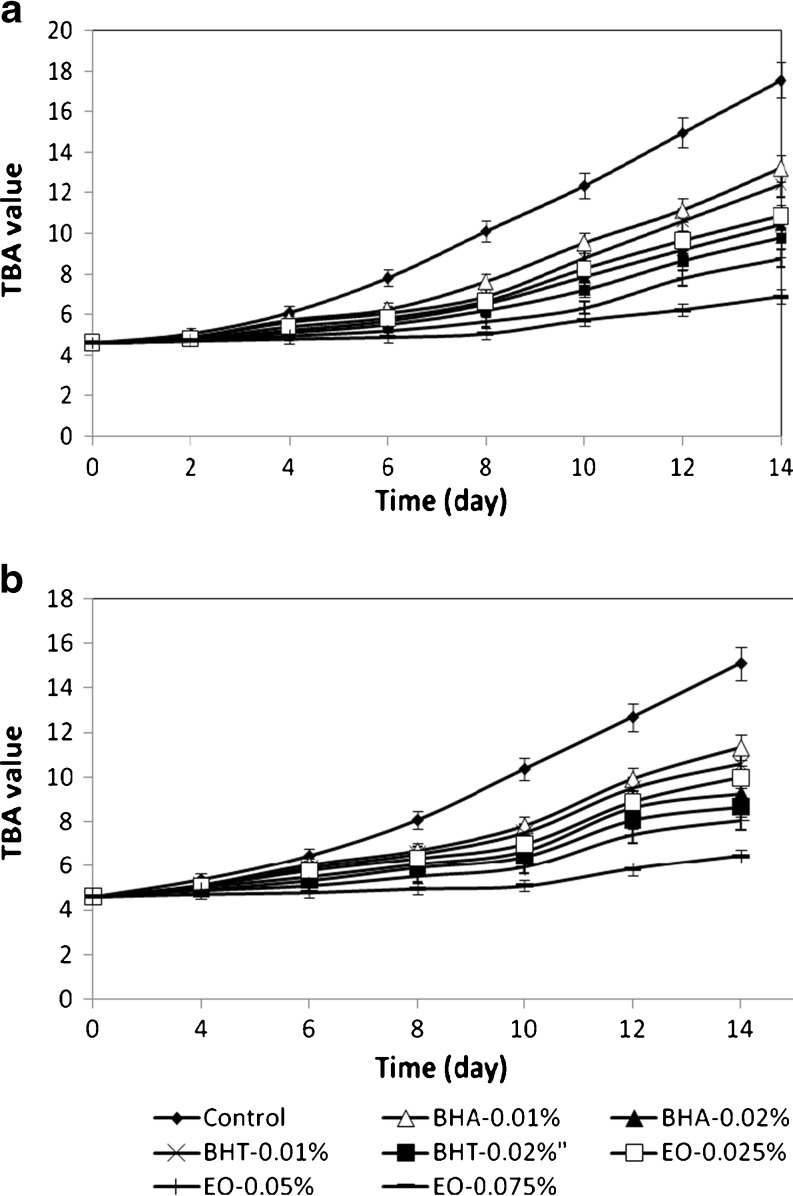

TBA test another empirical method widely used for detection of secondary oxidation products of oils and fats (AOCS 1998). Results of TBA value measurements are very similar to results of AnV measurements, as seen in Fig. 3. During storage at 37 and 47 °C, TBA values of sunflower oil samples were increased.

Fig. 3.

TBA value of sunflower oil without antioxidant and with EO, BHA and BHT during storage at 47 (a) and 37 °C (b)

All concentrations of EO showed significantly protection effect against secondary oxidation and samples with EO at 0.075% gave the lowest increase in TBA value. The oil samples added with 0.05% EO had a significantly lower level of secondary products compared to the samples with various concentrations of synthetic antioxidants.

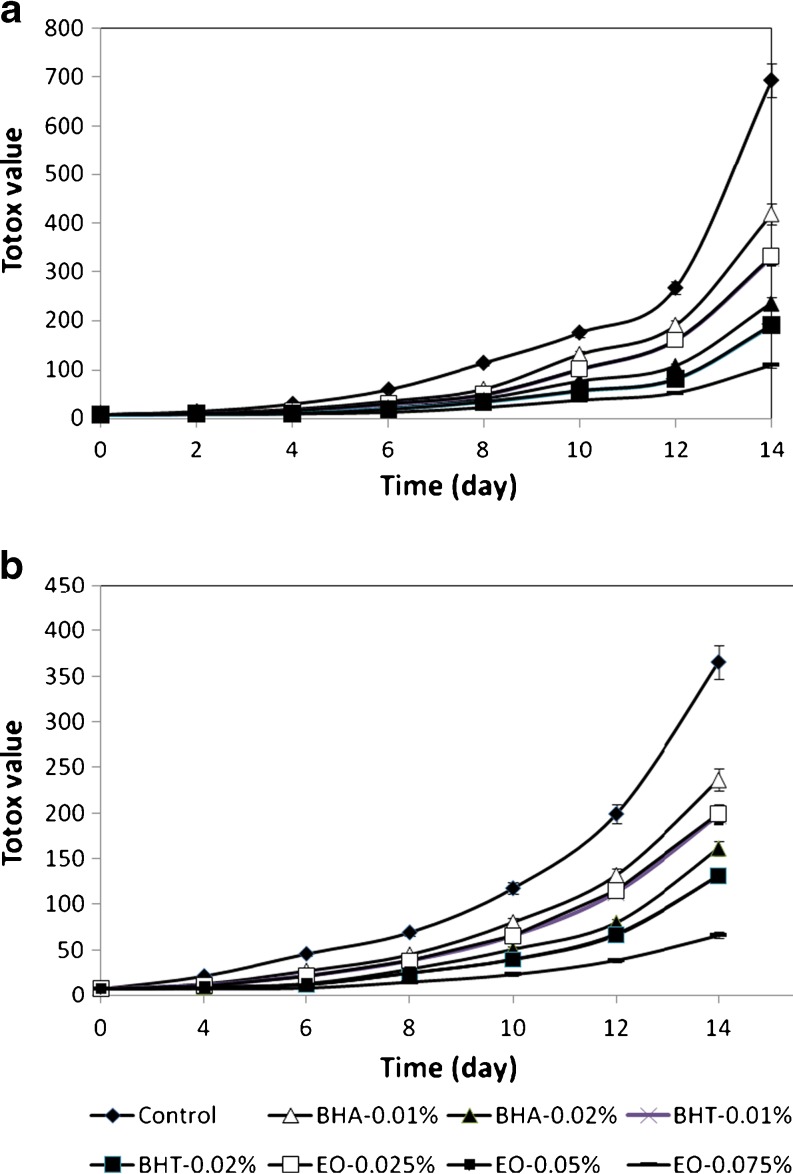

Totox value measures primary and secondary products of oxidation process. The results of total value of sunflower oil samples during storage at 37 and 47 °C given in Fig. 4. As it shows, the totox value of all samples were increased steadily during storage at two temperatures, but EO at 0.075% had a significantly better stability than other additives.

Fig. 4.

Totox value of sunflower oil without antioxidant and with EO, BHA and BHT during storage at 47 (a) and 37 °C (b)

Any significant differences weren’t observed in totox value of sunflower oil with EO at 0.05% and BHT at 0.02%, whereas the totox value of sunflower oil with BHA was significantly higher than 0.05% EO. In Table 2, the AA, F value, and AOP for all tested antioxidants are presented. AA of EO was significantly lower than BHT and BHA at two temperatures, because this EO could be retarded the oxidation of sunflower oil at the higher concentration than synthetic antioxidants.

Table 2.

Characteristics of BHA, BHT and EO in sunflower oil during storage at 37 and 47 °C*

| Parameter | Temperature | BHA-0.02% | BHT-0.02% | EO-0.05% | EO-0.075% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AA | 2850a | 3500b | 1360c | 1320c | |

| F | 37 °C | 1.57e | 1.7f | 1.68f | 1.99t |

| AOP | 36h | 41k | 41k | 50r | |

| AA | 2785a | 3515b | 1380c | 1362c | |

| F | 47 °C | 1.56e | 1.7f | 1.69f | 2.02t |

| AOP | 35.8h | 41.3k | 41k | 49r |

*All values are means of three determinations. Values with the same superscript are not significantly different (P < 0.05)

EO essential oil of Carum copticum; AA antioxidant activity; F stabilization factor; AOP antioxidant power

The evaluation of antioxidant effectiveness frequently corresponds to an extension of the IP as result of the addition of the antioxidant compound (Hras et al. 2000; Silva et al. 2001). All concentrations of EO increased IP of sunflower oil during oxidation at two temperatures. EO at the higher concentration was significantly more active than the lower concentration. This delay is often expressed as AOP or F value. F value and AOP of EO at 0.075% concentration in sunflower oil were significantly higher than other additives at two temperatures. Any significant differences weren’t observed in F value and AOP of EO at 0.05% and BHT at 0.02%, while EO at this concentration was more active than BHA at 0.02% during storage at 37 and 47 °C (P < 0.05).

Activity of EO as antioxidant in sunflower oil wasn’t significantly different at 37 and 47 °C. Same results also obtained with synthetic antioxidants. Yanishlieva and Marenova (2001) found activity of some antioxidants like fraxetin increased with rising temperature while some of them like BHT aren’t affected. Moreover, activity of antioxidant compounds could be affected by many factors such as; food, processing and storage conditions (Bandoniene et al. 2002).

Antioxidant activity of essential oils depends on their qualitative and quantitative composition of them. Result of GC-MS showed main component of EO is thymol. This component has a hydrogen donating ability and participates in chain initiation and propagation of oxidation (Huang and Frankel 1997; Yanishlieva and Marenova 2001). thymol is a primary antioxidant which either delay or prevent the initiation step by reacting with a lipid-free radical or prevent the propagation step by reacting with the peroxy or alkoxy radicals (Adegoke et al. 1998), thereby could be retarded of sunflower oxidation.

On the basis of PV, AnV, TBA value, totox value, F value, AA and AOP measurements, the order of antioxidative effectiveness in sunflower oil was: EO-0.075%>EO-0.05%≥BHT-0.02%>BHA-0.02%>EO-0.025%≥BHT-0.01%>BHA-0.01%.

Conclusions

In this study all concentrations of EO are suitable antioxidants for preserving of sunflower oil against oxidation. Synthetic antioxidants like BHA and BHT can be substituted with the EO but only if the EO is used in higher concentrations

References

- Adams RP. Identification of essential oil components by gas chromatography/mass spectrometry. 4. Carol Stream: Allured Publishing Corporation; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Adegoke GO, Vigakumar M, Gopalkrishna AO, Varadraj MC, Sambahiah K, Lokesh BR. Antioxidants and lipid oxidation in foods. J Food Sci Technol. 1998;35:283–293. [Google Scholar]

- American Oil Chemist’s Society (1998) Official methods and recommended practices of the AOCS, American Oil Chemist’s Society, 5rd edn. S, Champaign, IL, USA. Methods: Cd 8–53, Cd 18–90, Cd 19–90.

- Bandoniene D, Venskutonis PR, Gruzdiene D, Murkovic M. Antioxidant activity of sage (Salvia officinalis L.), savory (Satureja hortensis L.) and borage (Borago officinalis L.) extracts in rapeseed oil. Eur J Lipid Sci Technol. 2002;104:286–292. doi: 10.1002/1438-9312(200205)104:5<286::AID-EJLT286>3.0.CO;2-O. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Boskabady MII, Shaikhi J. Inhibitory effect of Carum copticum on histamine (H1) receptors of isolated guinea-pig tracheal chains. J Ethnopharmacol. 2000;69:217–227. doi: 10.1016/S0378-8741(99)00116-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- British pharmacopoeia 1998. London: HMSO; 1988. pp. 137–138. [Google Scholar]

- Burits M, Bucar F. Antioxidant activity of Nigella sativa essential oil. Phytother Res. 2000;14:323–328. doi: 10.1002/1099-1573(200008)14:5<323::AID-PTR621>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decker EA, Warner K, Richards MP, Shahidi F. Measuring antioxidant effectiveness in food. J Agric Food Chem. 2005;53:4303–4310. doi: 10.1021/jf058012x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goudarzi GR, Saharkhiz MJ, Sattari M, Zomorodian K. Antibacterial activity and chemical composition of Ajowan (Carum copticum Benth. & Hook) essential oil. J Agr Sci Tech. 2011;13:203–208. [Google Scholar]

- Hamama AA, Nawar WW. Thermal decomposition of some phenolic antioxidants. J Agric Food Chem. 1991;39:1063–1069. doi: 10.1021/jf00006a012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hras AR, Hadolin M, Knez Z, Bauman D. Comparison of antioxidative and synergistic effects of rosemary extract with α-tocopherol, ascorbylpalmitate and citric acid in sunflower oil. Food Chem. 2000;71:229–233. doi: 10.1016/S0308-8146(00)00161-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huang SW, Frankel EN. Antioxidant activity of tea catechins in different lipid systems. J Agric Food Chem. 1997;45:3033–3038. doi: 10.1021/jf9609744. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Labrador V, Fernandez P, Perez Martin JM, Hazen MJ. Cytotoxicity of butylated hydroxyanisole in vero cells. Cell Biol Toxicol. 2006;23:189–199. doi: 10.1007/s10565-006-0153-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lateef M, Iqbal Z, Akhtar MS, Jabbar A, Khan MN, Gilani AH. Preliminary screening of Trachyspermum ammi (L.) seed for anthelmintic activity in sheep. Trop Anim Health Prod. 2006;38:491–496. doi: 10.1007/s11250-006-4315-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H, Qiu N, Ding H, Yao R. Polyphenols contents and antioxidant capacity of 68 chinese herbals suitable for medical or food uses. Food Res Int. 2008;41:363–370. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2007.12.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moure A, Cruz JM, Franco D, Dominguez JM, Sineiro J, Dominguez H, Nunez MJ, Parajo JC. Natural antioxidant from residual sources. Food Chem. 2001;72:145–171. doi: 10.1016/S0308-8146(00)00223-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rossel JB. Measurement of rancidity. In: Allen JC, Hamilton RJ, editors. Rancidity in foods. USA: Elsevier; 1989. pp. 28–32. [Google Scholar]

- Sharififar F, Moshafi MH, Mansouri SH, Khodashenas M, Khoshnoodi M. In vitro evaluation of antioxidant and antibacterial activities of the essential oil and methanol extract of endemic Zataria multiflora Boiss. Food Control. 2007;18:800–805. doi: 10.1016/j.foodcont.2006.04.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sanhueza J, Nieto S, Valenzuela A. Thermal stability of some commercial synthetic antioxidants. J Am Oil Chem Soc. 2000;77:933–936. doi: 10.1007/s11746-000-0147-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schaich KM. Lipid oxidation: theoretical aspects. In: Shahidi F, editor. Bailey’s industrial oil and fat products, A Wiley-Interscience Publication. New York: Wiley; 2005. pp. 269–299. [Google Scholar]

- Sharif Ali S, Kasoju N, Luthra A, Singh A, Sharanabasava H, Sahu A, Bora U. Indian medicinal herbs as sources of antioxidants. Food Res Int. 2008;41:1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2007.10.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Silva FAM, Borges F, Ferreira MA. Effects of phenolic propyl esters on the oxidative stability of refined sunflower oil. J Agric Food Chem. 2001;49:3936–3941. doi: 10.1021/jf010193p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suhaj M. Spice antioxidants isolation and their antiradical activity. J Food Compos Anal. 2006;19:531–537. doi: 10.1016/j.jfca.2004.11.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wanasandara PKJPD, Shahidi F. Antioxidants: science, technology, and applications. In: Shahidi F, editor. Bailey’s industrial oil and fat products. A Wiley-Interscience Publication. New York: Wiley; 2005. pp. 445–447. [Google Scholar]

- Wojdylo A, Oszmianski J, Czemerys R. Antioxidant activity and phenolic compounds in 32 selected herbs. Food Chem. 2007;105:940–949. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2007.04.038. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yanishlieva NV, Marenova EM. Stabilisation of edible oils with natural antioxidants. Eur J Lipid Sci Technol. 2001;103:732–767. [Google Scholar]

- Zargari A. Medicinal plants. Tehran: Tehran University Publications; 1990. p. 42. [Google Scholar]