Abstract

In contrast to the gradual reduction in the number of locally transmitted malaria cases in China, the number of imported malaria cases has been increasing since 2008. Here, we report a case of a 39-year-old Chinese man who acquired Plasmodium ovale wallikeri infection while staying in Ghana, West Africa for 6 months in 2012. Microscopic examinations of Giemsa-stained thin and thick blood smears indicated Plasmodium vivax infection. However, the results of rapid diagnostic tests, which were conducted 3 times, were not in agreement with P. vivax. To further check the diagnosis, standard PCR analysis of the small-subunit rRNA gene was conducted, based on which a phylogeny tree was constructed. The results of gene sequencing indicated that this malaria is a variant of P. ovale (P. ovale wallikeri). The infection in this patient was not a new infection, but a relapse of the infection from the one that he had contracted in West Africa.

Keywords: Plasmodium ovale wallikeri, imported malaria, case report, China

INTRODUCTION

Although locally-transmitted malaria has been under control, imported malaria, including Plasmodium knowlesi and Plasmodium ovale infections, are still being monitored in China [1], the Republic of Korea [2], and Japan [3]. In 2010, the Ministry of Health in China launched an action plan for malaria elimination, with the goals of eradicating local malaria cases in regions outside of the Yunnan border area by the end of 2015 and eliminating malaria in the entire country by the end of 2020 [4]. However, the proportion of imported malaria cases caused by 4 traditional species including falciparum, vivax, malariae, and ovale rapidly increased to 66.4% in 2011, since monitoring of imported malaria cases first started in 2008 [1,5]. Effective surveillance of every malaria case is important, and malaria strategies should range from the control stage to elimination of malaria.

In 2011, the national malaria genetic diagnosis protocol was released by Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. In this protocol, the gene encoding the small subunit (SSU) rRNA was identified as the target gene for differentiation, because this gene has highly conserved and variable regions that not only allow discrimination of different Plasmodium species but can also be used for obtaining information about the phylogenetic characterization of different malaria parasites. Fifty malaria cases in Hainan Province have been confirmed, and 18 cases were excluded by this protocol since the Hainan malaria reference laboratory was established in 2011.

In this article, we present a case of Plasmodium ovale wallikeri in China imported from West Africa. The case was diagnosed by microscopic examinations, rapid diagnosis test (RDT), nested PCR, and sequencing analysis of the SSU rRNA gene. Interestingly, this was a case of relapse and was not a new infection.

CASE DESCRIPTION

On 28 February 2013, a 39-year-old Chinese patient presented to Baoxian Township Hospital in Hainan Province with a 2-day history of daily fever, mild headache, chills, and temperature up to 38℃. He had worked in Sierra Leone from July 2012 to January 2013, after which he returned to Hainan. He had cold and fever symptoms on one occasion in July 2012 in Ghana, and was diagnosed with malaria by a local hospital and treated with artemether injection daily for 3 days.

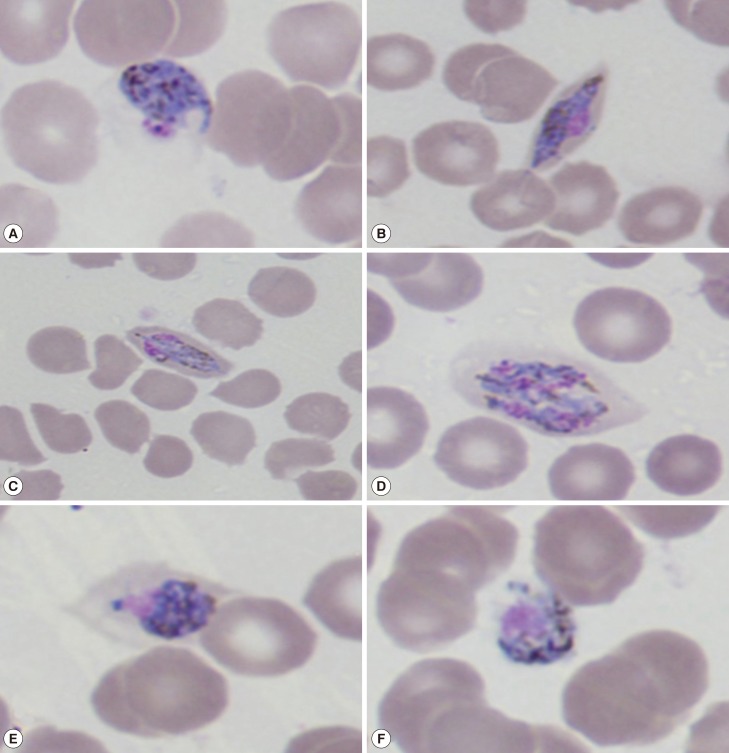

After he was admitted to Baoxian Township Hospital, thin and thick blood smears were taken and stained with Giemsa (Fig. 1). We observed all stages of the erythrocytic cycle of malaria in the blood films and Plasmodium vivax was suspected. Infected RBCs were round to oval or slightly enlarged in size, but slightly fimbriated suggestive of P. ovale. Under certain optical conditions, Schüffner's dots were seen.

Fig. 1.

Giemsa-stained thin blood smears at the time of presentation (×1,000) showing different life-cycle stages of Plasmodium ovale wallikeri. (A, B) Different types of trophozoites seen in oval RBCs. (C, D) Mature and immature P. ovale schizonts with 4-6 merozoites containing large nuclei seen clustered around a mass of dark-brown pigment. (E, F) Gender-specific round to oval P. ovale gametocytes almost filling the RBCs.

To further assess the condition, RDT (Care Start™, ACCESS BIO Inc.) (Monmouth Junction, New Jersey, USA) to detect Plasmodium falciparum histidine-rich protein 2 (HRP-2) and Plasmodium species lactate dehydrogenase (pLDH) was conducted. The results indicated a Plasmodium infection, but they did not confirm the causative agent to be P. vivax (the test was repeated 3 times). Subsequently, the patient was treated with chloroquine for 3 days and primaquine for 8 days, according to China's malaria treatment guidelines for vivax malaria.

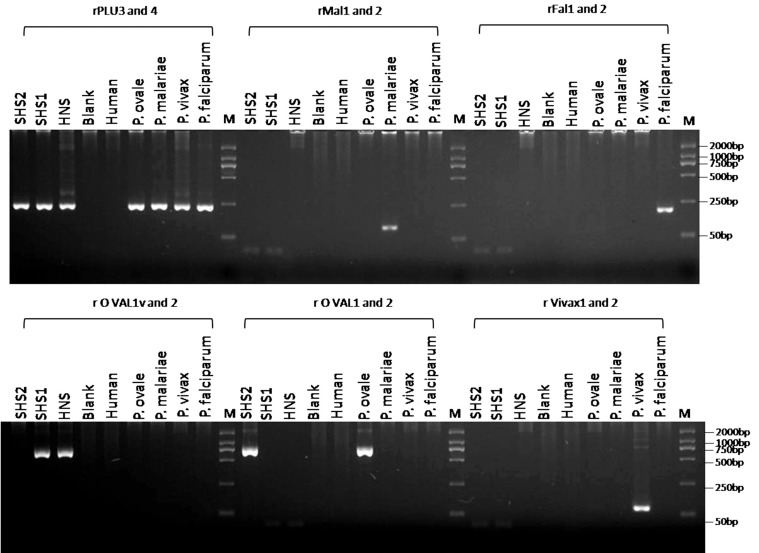

The pigment in the case of P. ovale is brown and coarser in comparison to that of P. vivax. To make a definitive diagnosis, the blood samples were transferred to the Hainan Provincial Center for Disease Control and Prevention for further PCR amplification and genetic analyses. Genomic DNA was extracted from 80 µl of the whole blood sample by using a QIAamp Blood Mini kit (Qiagen, Valencia, California, USA) according to the national malaria diagnosis protocol. The partial gene of the SSU rRNA gene was amplified by PCR with Plasmodium-specific primers (rPLU1 and rPLU5) in Nest1 PCR, and species-specific primers (rFAL 1 and 2, rMAL 1 and 2, rVIV 1 and 2, and rOVA 1 and 2) and genus-specific primers (rPLU3 and rPLU4) in Nest 2 PCR. The Nest 1 amplification conditions were as follows: step 1, 94℃ for 5 min; step 2, denaturation at 94℃ for 30 sec; step 3, annealing at 55℃ for 1 min; step 4, extension at 72℃ for 2 min; steps 2-4 were then repeated 35 times, followed by step 4 for 5 min. Two microliters of the Nest 1 amplification product served as the DNA template for each of the 20-ml Nest 2 amplifications. The concentration of the Nest 2 primers and other constituents were identical to those for the Nest 1 amplifications. The PCR products of the Nest 1 and Nest 2 amplifications were analyzed by 2.5% agarose gel electrophoresis and staining with ethidium bromide (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Detection of Plasmodium spp. and P. ovale wallikeri DNA by nested PCR assays. Molecular size markers in base pairs (bp) are shown in the end lanes (M). A: rFAL 1 and rFAL 2, P. falciparum-specific primers (205 bp); rVIV 1 and rVIV 2, P. vivax-specific primers (144 bp); rMAL 1 and rMAL 2, P. malariae-specific primer (112 bp); rOVA 1 and rOVA 2, P. ovale curtisi-specific primers (800 bp); rOVA 1v and rOVA 2v, P. ovale wallikeri-specific primers (782 bp); rPLU 3 and rPLU 4, Plasmodium-specific primers (240 bp). B: HNS: Hainan sample; SHS1 and SHS2: the first and second delivery samples from Shanghai Center for Disease Control and Prevention, respectively.

Amplification results with the species-specific primers were negative for faciparum, vivax, malariae, and ovale malaria parasites. However, positive results were obtained with the genus-specific primers rPLU3 and rPLU4. For confirmation of the results, the PCR products from the genus-specific primers rPLU1 and rPLU5 were sequenced using the 3,730×l DNA Analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, California, USA) after TA cloning; the M13 sequencing primer and 2 internal sequencing primers, KR1 (5'-TAA CCAGACAAATCATATTCACGAAC-3') and rPLU6 (5'-TTAAAATTGTTGCAGTTAAAACG-3'), were used [6]. Analysis of sequences in the NCBI database indicated that the causative species may have been a variant type of P. ovale, i.e., P. ovale wallikeri. To confirm this, a set of primers specific for P. ovale wallikeri (rOVA1v and rOVA2v) were used for amplification under the same conditions described before for Nest 2, and a 782 bp positive fragment was obtained [7,8]. The sequence of our specimen was deposited in GenBank, NCBI under the accesion no. KF048920.

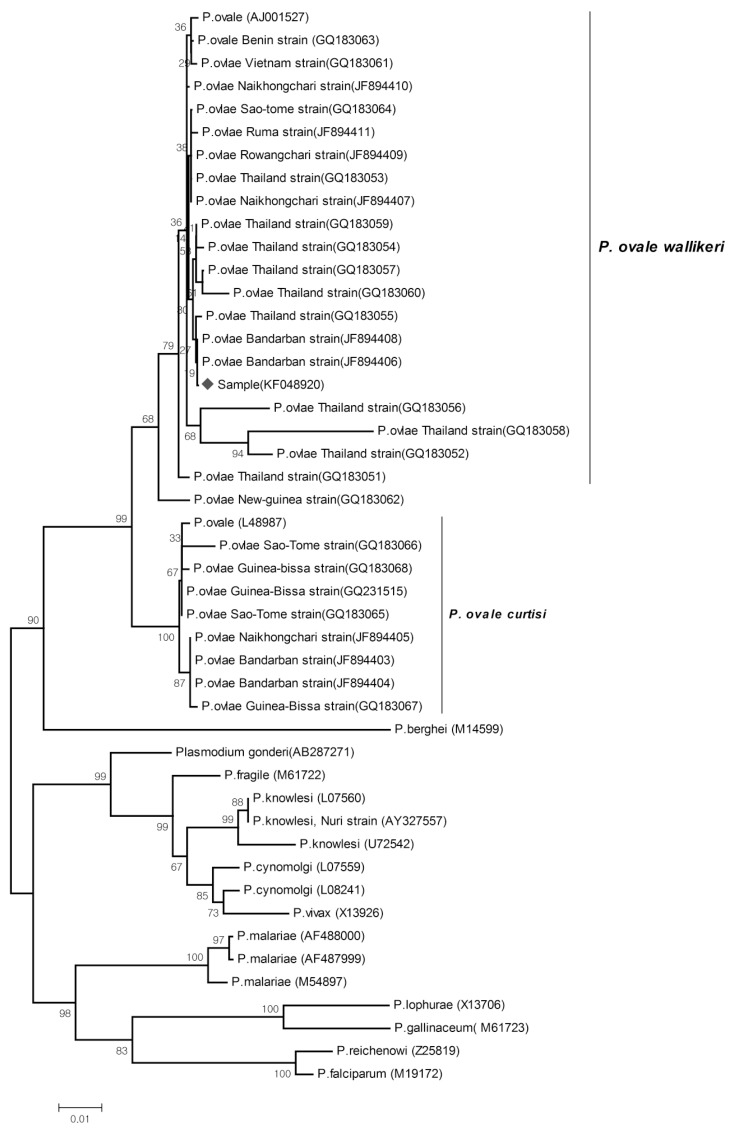

The phylogeny tree was constructed using the neighbor-joining method in MEGA 3 (http://www.megasoftware.net). Sequences reported in GenBank for a number of Plasmodium species were also used to construct the tree. Bootstrap proportions were used to assess the robustness of the tree, with 1,000 bootstrap replications (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

The phylogeny tree constructed using the neighbor-joining method, to compare our sample (KF048920) (denoted as ♦) with other Plasmodium species, based on SSU rRNA genetic analyses. Figures on the branches are bootstrap percentages based on 1,000 replicates, and only those above 80% are shown. GenBank accession numbers are in parentheses.

After the treatment, the patient felt better and his malaria symptoms disappeared in 1 day after treatment. The parasite was not detected by PCR 3 days after the treatment, and the disease did not recur after 28 days. However, the patient could not be followed up after a point because he needed to return to Sierra Leone to resume work in May 2013.

DISCUSSION

P. ovale is the last reported malaria parasite in humans (before P. knowlesi), and it is mainly found in West Africa [9]. In 2010, P. ovale was reported to be divided into 2 subspecies, P. ovale curtisi (classic type) and P. ovale wallikeri (variant type), with the estimated time of divergence between the 2 subspecies being 1 and 3 million years ago [10]. In China, faciparum and vivax malaria were frequently detected in most endemic areas, but malariae and ovale were only detected in the border of Yunnan Province with Myanmar in recent 30 years.

Microscopy-based diagnosis is a traditional tool for diagnosing malaria, especially in cases located in remote areas, as it is more convenient and time-saving. However, this method is not very efficient in accurately distinguishing between certain malarial species that have morphological similarities, for example, between P. malariae and P. knowlesi, and between P. ovale with P. vivax [3]. In our case, P. ovale wallikeri was mistakenly identified as P. vivax because our microscopist was unfamiliar with morphological stages of the former species. Therefore, there are chances of the causative species being wrongly identified in malaria cases. RDTs are believed to overcome these limitations; these tests have been commercially available, and in recent years, they have allowed quick diagnosis in endemic malaria areas with high or low incidence. In this method, the diagnosis is based on identification of some very specific proteins expressed by the malaria parasite, and it has been shown to have high sensitivity and specificity in the field. However, there are still some reports of failure and misdiagnosis [11]. The failures were believed to be caused by low levels of parasitemia, the absence of specific monoclonal antibodies, and genetic variations. Further research on this method is therefore essential.

Diagnosis of malaria by PCR has quickly emerged as a standard methodology in the molecular identification of Plasmodium spp., ever since Snounou et al. [12] introduced a species-specific nested PCR technique targeting conserved regions of the SSU rRNA gene. However, even species-specific primers, such as rOVA1 and rOVA2 for P. ovale, were found to be ineffective in the case of variant forms of this species, until specific primers for the variant forms (rOVA1v and rOVA2v) were introduced later in 2007 [7]. This article is the first to use primers of the variants of P. ovale and to confirm their usefulness by constructing the phylogeny tree for the SSU rRNA gene. From the phylogenetic tree, it seems that this strain of P. ovale belongs to the P. ovale wallikeri cluster, as it shows a close relationship with members of this cluster. These methods were also applied to 2 mailed samples from the Shanghai Center for Disease Control and Prevention, 1 of which was also identified as P. ovale wallikeri. These findings indicate that these variants of P. ovale may be found in other localities in China, especially among imported malaria cases originating from West Africa and South Asia.

When we tried to trace the origin of the infection in our patient, we found that the infection was initiated from hypnozoites in his liver, which indicates that it was a relapse and not a new infection. However, cases of relapse of P. ovale infections are rare. At the time of admission, it had been 56 days since his return from Sierra Leone; this period exceeded the incubation period (12-18 days) of P. ovale [13]. Therefore, based on the date of the illness and incubation period of this species, we inferred that this patient had a relapse and not a new infection.

From the findings of this study, we think that it is important to develop standardized protocols for detection of Plasmodium parasites and that the protocols need to be more comprehensive so as to allow detection of possibly unknown variants of malarial parasites.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study received a financial support from the Hainan Provincial Scientific Research grant (Grant no. 310174 and 813251). We would like to thank the patients who participated in this report and the staff from Ledong County's Center for Disease Control and Prevention and from Baoxian Township Hospital. We would also like to thank Dr. Zaixing Zhang from WHO Country Liaison Office for support with grammar and writing style of this manuscript. None of the authors have competing interests to declare.

Footnotes

Consent: The objectives of this report were explained to the patient, after which his oral informed consent for publication of this case report and any accompanying images was obtained.

References

- 1.Zhou SS, Wang Y, Fang W, Tang LH. Malaria situation in the People's Republic of China in 2008. Zhongguo Ji Sheng Chong Xue Yu Ji Sheng Chong Bing Za Zhi. 2009;27:455–457. (in Chinese) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kang Y, Yang J. A case of Plasmodium ovale malaria imported from West Africa. Korean J Parasitol. 2013;51:213–218. doi: 10.3347/kjp.2013.51.2.213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tanizaki R, Ujiie M, Kato Y, Iwagami M, Hashimoto A, Kutsuna S, Takeshita N, Hayakawa K, Kanagawa S, Kano S, Ohmagari N. First case of Plasmodium knowlesi infection in a Japanese traveler returning from Malaysia. Malar J. 2013;12:128. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-12-128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.China Action Plan for Malaria Elimination. ( http://www.moh.gov.cn/publicfiles/business/htmlfiles/mohjbyfkzj/s3593/201005/47529.htm)

- 5.Xia ZG, Yang MN, Zhou SS. Malaria situation in the People's Republic of China in 2011. Zhongguo Ji Sheng Chong Xue Yu Ji Sheng Chong Bing Za Zhi. 2012;30:419–422. (in Chinese) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Singh B, Sung KL, Matusop A, Radhakrishnan A, Shamsul SSG, Cox-Singh J, Thomas A, Conway DJ. A large focus of naturally acquired Plasmodium knowlesi infections in human beings. Lancet. 2004;363:1017–1024. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)15836-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Calderaro A, Piccolo G, Perandin F, Gorrini C, Peruzzi S, Zuelli C, Ricci L, Manca N, Dettori G, Chezzi C, Snounou G. Genetic polymorphisms influence Plasmodium ovale PCR detection accuracy. J Clin Microbiol. 2007;45:1624–1627. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02316-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fuehrer HP, Stadler MT, Buczolich K, Bloeschl I, Noedla H. Two techniques for simultaneous identification of Plasmodium ovale curtisi and Plasmodium ovale wallikeri by use of the small-subunit rRNA gene. J Clin Microbiol. 2012;50:4100–4102. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02180-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Collins WE, Jeffery GM. Plasmodium ovale: parasite and disease. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2005;18:570–581. doi: 10.1128/CMR.18.3.570-581.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sutherland CJ, Tanomsing N, Nolder D, Oguike M, Jennison C, Pukrittayakamee S, Dolecek C, Hien TT, do Rosário VE, Arez AP, Pinto J, Michon P, Escalante AA, Nosten F, Burke M, Lee R, Blaze M, Otto TD, Barnwell JW, Pain A, Williams J, White NJ, Day NPJ, Snounou G, Lockhart PJ, Chiodini PL, Imwong M, Polley SD. Two non-recombining sympatric forms of the human malaria parasite Plasmodium ovale occur globally. J Infect Dis. 2010;201:1544–1550. doi: 10.1086/652240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bauffe F, Desplans J, Fraisier C, Parzy D. Real-time PCR assay for discrimination of Plasmodium ovale curtisi and Plasmodium ovale wallikeri in the Ivory Coast and in the Comoros Islands. Malar J. 2012;11:307. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-11-307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Snounou G, Viriyakosol S, Zhu XP, Jarra W, Pinheiro L, do Rosario VE, Thaithong S, Brown KN. High sensitivity of detection of human malaria parasites by the use of nested polymerase chain reaction. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1993;61:315–320. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(93)90077-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heymanm DL. Control of Communicable Disease Manual. 18th ed. Washington DC, USA: American Public Health Association; 2004. p. 335. [Google Scholar]