Abstract

At early times in Mammalian Orthoreovirus (MRV) infection, cytoplasmic inclusions termed stress granules (SGs) are formed as a component of the innate immune response, however, at later times they are no longer present despite continued immune signaling. To investigate roles of MRV proteins in SG modulation we examined non-structural protein μNS localization relative to SGs in infected and transfected cells. Using a series of mutant plasmids, we mapped necessary μNS residues for SG localization to amino acids 78 and 79. We examined the capacity of a μNS(78-79) mutant to associate with known viral protein binding partners of μNS and found that it loses association with viral core protein λ2. Finally, we show that while this mutant cannot support de novo viral replication, it is able to rescue replication following siRNA knockdown of μNS. These data suggest that μNS association with SGs, λ2, or both play roles in MRV replication.

Keywords: mammalian orthoreovirus, μNS, stress granules, translation, replication, innate immunity

INTRODUCTION

Mammalian Orthoreovirus (MRV) is a member of the dsRNA family Reoviridae that contains a number of viruses important in human, animal, and plant health. In mammals, these viruses can cause respiratory or gastrointestinal illness which in some cases (eg. Rotavirus, Bluetongue virus), can lead to host death (Parashar et al., 2009; Schwartz-Cornil et al., 2008). In contrast, MRV is non-pathogenic in humans and most animals and therefore lends itself to being a safe research vehicle for determining the nuances of viral replication in a host organism. To initiate infection MRV particles bind to their primary and secondary receptors, JAM-1 and sialic acid respectively, via the cell attachment protein σ1 and enter the cell by receptor mediated endocytosis (Barton et al., 2001; Chappell et al., 1997). Once in the endosome intermediate subvirion paticles (ISVPs) are formed via cathepsin protease cleavage of capsid protein σ3, resulting in exposure of the previously shielded MRV membrane penetration protein μ1 (Ebert et al., 2002). Proteolytic cleavage and conformational reorganization of μ1 facilitates movement of transcriptionally active core particles across the endosomal membrane into the cytoplasm (Agosto et al., 2006; Chandran et al., 2002; Nibert and Fields, 1992; Zhang et al., 2006). Once in the cytoplasm viral positive sense RNAs are transcribed from within the core particle and are released to be synthesized into protein by the cellular translational machinery (Shatkin and Both, 1976; Tao et al., 2002).

Early in MRV infection viral factories (VFs) form as small punctate structures throughout the cytoplasm that grow in size and become more perinuclear as infection continues (Rhim et al., 1962). The structural matrix of VFs appears to be primarily formed by the MRV non-structural protein μNS, which, when expressed in the absence of other virus proteins, forms virus factory like (VFL) structures in cells (Broering et al., 2002; Mora et al., 1987). μNS is a 721 amino acid, primarily α-helical protein encoded by the M3 MRV gene segment that has been shown to interact with most other MRV proteins and virus core particles (Broering et al., 2004; Broering et al., 2002; McCutcheon et al., 1999; Miller et al., 2010; Miller et al., 2003). These associations are likely to be important in recruiting newly synthesized proteins to the VFs to allow for the efficient assembly of progeny virus core particles. VFs are dynamic structures that are thought to be the primary location of virus transcription, replication, and assembly and recent studies have shown that the formation of VFs is necessary for successful MRV infection (Arnold et al., 2008; Becker et al., 2003; Broering et al., 2000; Dales, 1965; Kobayashi et al., 2009).

When MRV enters a host cell the innate immune response is activated via PKR, resulting in phosphorylation of eIF2α and shutoff of host translation (Pain, 1996; Samuel et al., 1984; Smith et al., 2005; Zweerink and Joklik, 1970). While some MRV strains are able to prevent this shutoff via the dsRNA binding activity of the viral σ3 protein, other MRV strains are unable to inhibit host translational shutoff following infection (Imani and Jacobs, 1988; Schmechel et al., 1997; Smith et al., 2005; Yue and Shatkin, 1997). Concurrent with translational inhibition, important translational factors are sequestered into cytoplasmic bodies termed stress granules (SGs). SGs form following eIF2α phosphorylation and other perturbations of translation initiation that lead to the accumulation of stalled ribosomal complexes in the cell (Anderson and Kedersha, 2002; Dang et al., 2006; Kedersha and Anderson, 2002; Kim et al., 2007; Mazroui et al., 2006; Mokas et al., 2009). SGs appear as globular structures throughout the cytoplasm and consist of an accumulation of cellular proteins such as T-cell restricted antigen-1 (TIA-1), TIA-1 related (TIAR), and GTPase-activating protein binding protein-1 (G3BP), translation initiation factors, translationally silent mRNAs, and small, but not large, ribosomal subunits (Gilks et al., 2004; Tourriere et al., 2003). SGs have previously been found in MRV infected cells following virus-induced eIF2α phosphorylation (Qin et al., 2009; Smith et al., 2006). Despite sustained levels of eIF2α phosphorylation, SGs appear to be disrupted at later times in infection. This disruption of SGs correlates with the escape of viral, but not cellular, mRNAs from host translational shutoff (Qin et al., 2011). As the ability to overcome translational shutoff is critical for continued viral replication, describing the mechanism of MRV modulation of SGs is likely to be an important step in understanding the virus’s ability to circumvent the cellular stress response.

Although many aspects of SG formation and function are not fully understood, it is believed that they may serve as a component of the innate immune response to infection by many viruses (Lloyd, 2012; Onomoto et al., 2012). Viruses such as poliovirus, influenza A virus, and hepatitis C virus are also known to modulate SGs upon infection. These viruses have devised strategies to circumvent the loss of cellular translational machinery to SGs. These strategies range from preventing the formation of SGs to disrupting SGs to allow for successful replication (Garaigorta et al., 2012; Khaperskyy et al., 2012; White et al., 2007; White and Lloyd, 2011; Yi et al., 2011). Other viruses like respiratory syncytial virus and vaccinia virus appear to take advantage of SGs to enhance their replication (Katsafanas and Moss, 2007; Lindquist et al., 2010). While SG formation and disruption during MRV infection is well-established, the mechanisms involved and role played by MRV in the process have not been determined.

To further investigate SG modulation during MRV infection we examined the localization of each virus protein relative to SGs in both infected and transfected cells. Several MRV proteins, including μNS, appeared to localize to SGs. We hypothesized that μNS, via its association with SGs and other virus proteins, may serve as a nucleating factor for localization of other virus proteins to SGs. Moreover, because μNS VFLs have been shown to require an intact cellular microtubule network (which is also necessary for SG formation) for coalescence into larger VFL structures and movement to perinuclear regions of the cell (Broering et al., 2002), we also hypothesized that μNS may utilize the microtubule machinery to associate with SGs or usurp the microtubule machinery and prevent SG formation during MRV infection. Utilizing deletion and point mutations we mapped the interaction between μNS and SGs and identified a two amino acid region within the amino (N)-terminal third of μNS necessary for SG localization. We additionally examined the impact of this mutation on previously identified interactions between μNS and other viral proteins. Finally, we examined the effect of this mutation on virus replication.

RESULTS

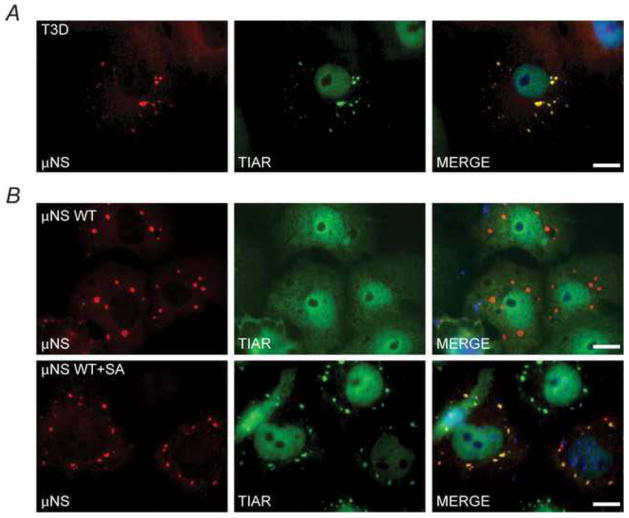

μNS colocalizes with SGs in infected and transfected cells but does not modulate SG formation

In an effort to determine the mechanism of SG modulation in MRV infection we examined the localization of MRV proteins relative to virus-induced SGs in infected cells. We have previously shown that MRV induces SGs at early times (4–6 h post infection, p.i.) in infection (Qin et al., 2009), therefore, Cos-7 cells were infected with MRV T3D and at 6 h p.i. cells were fixed and stained with antibodies against individual virus proteins and the SG-localized protein TIAR. Several viral proteins showed some localization to SGs, including the non-structural μNS protein (Fig. 1A and data not shown). Localization of μNS to SGs was also observed in cells infected with MRV strain T1L (data not shown).

Fig. 1. μNS localizes with but does not induce or disrupt SGs.

(A) Cos-7 cells were infected and at 6 h p.i. were fixed and immunostained with rabbit α-μNS polyclonal antiserum (left column) and goat α-TIAR polyclonal antibody (middle column) followed by Alexa-594 conjugated donkey α-rabbit IgG and Alexa-488 conjugated donkey α-goat IgG. Merged images containing DAPI-stained nuclei (blue) are shown (right column). (B) Cos-7 cells were transfected with pCI-μNS and at 24h p.t. were fixed and immunostained (top row) or treated with 0.5mM SA for 1h (bottom row) at 23h, fixed, and immunostained as in A. μNS WT = wild type, bar = 10 μm.

To determine if μNS had the capacity to induce SGs independently of infection Cos-7 cells were transfected with a plasmid expressing wild type μNS (pCI-μNS). At 24 h post-transfection (p.t.) cells were immunostained with antibodies against μNS and the SG localized protein TIAR (Fig 1B, top row). In these cells μNS formed the previously described VFL structures (Becker et al., 2003; Broering et al., 2002) whereas TIAR was diffusely distributed throughout the cells and SGs were not present. This data indicates that μNS is not capable of inducing SGs independently of virus infection and further, because TIAR did not localize to VFLs, that the association between μNS and SGs seen in infected cells does not likely occur through the TIAR protein. Similar results were seen in cells expressing μNS that were immunostained with antibodies against other known SG-localized proteins TIA-1 and G3BP (data not shown).

Although MRV induces SGs at early times in infection, we have previously shown that at late times in infection SGs are not present even though eIF2α is phosphorylated (Qin et al., 2011). Moreover, we found that at late times in infection MRV is able to prevent SG formation in cells treated with external stressors such as sodium arsenite (SA) which induces eIF2α phosphorylation through the Heme Regulated Inhibitor (HRI) kinase (McEwen et al., 2005). To ascertain whether μNS can disrupt SGs induced by SA, Cos-7 cells were transfected with pCI-μNS and at 23 h p.t. SA was added for 1 h to induce SGs, after which cells were fixed and immunostained with antibodies against μNS and TIAR (Fig 1B, bottom row). In these experiments SGs were clearly formed as a result of SA treatment in cells expressing μNS, suggesting that μNS is unable to independently prevent SG formation in the absence of infection. However, in these cells, μNS partially colocalized with SGs induced by SA with strong μNS staining in every SG as well as some μNS staining in VFLs that did not stain with TIAR. This pattern of localization suggests that upon SG formation a portion of μNS is recruited to SGs while a separate portion of μNS remains associated with VFL structures. Altogether these data suggest that μNS localizes to SGs in both infected and transfected cells, however, it is not solely responsible for the induction or disruption of SGs seen in MRV infected cells.

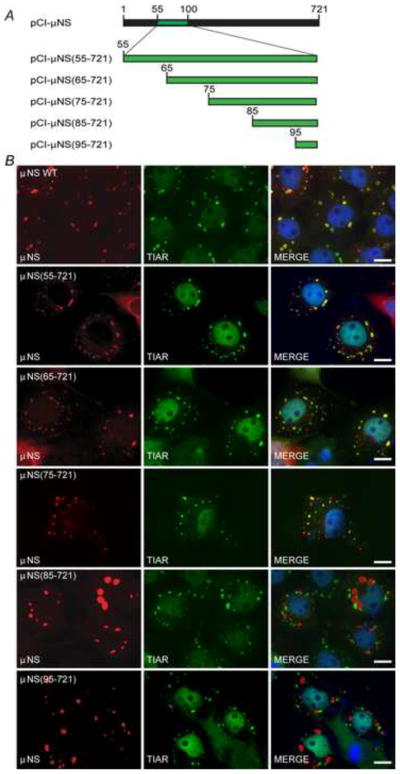

μNS amino acids 76–85 are required for association with SGs

In order to identify the region of μNS responsible for localization with SGs, a series of deletion mutant plasmids in which ten amino acid sections were progressively deleted from the μNS N-terminus were utilized (Miller et al., 2010) (Fig 2A). Cos-7 cells were transfected with the N-terminal deletion plasmids and at 23 h p.t. SGs were induced with SA, and μNS localization relative to SGs was determined by immunostaining with antibodies against μNS and TIAR (Fig 2B). In these experiments the interaction between μNS and SGs was maintained in all of the mutants up to the point where 75 amino-acids were deleted from the N-terminus [pCI-μNS(55-721), pCI-μNS(65-721), and pCI-μNS(75-721)], whereas those in which 76 or more amino-acids were deleted from the N-terminus lost localization with SGs [pCI-μNS(85-721) and pCI-μNS(95-721)]. The maintenance and loss of localization with SGs of these mutants suggests that μNS amino-acids 76–85 are necessary for μNS recruitment to SGs.

Fig. 2. μNS amino acids 76–85 are important for localization to SGs.

(A) Illustration of plasmids used in mapping the μNS residues necessary for SG localization. Not to scale. (B) Cos-7 cells were transfected with pCI-μNS (first row), pCI-μNS(55-721) (second row), pCI-μNS(65-721) (third row), pCI-μNS(75-721) (fourth row), pCI-μNS(85-721) (fifth row), and pCI-μNS(95-721) (sixth row) and at 23 h p.t. were treated with 0.5 mM SA for 1h, fixed, and immunostained with rabbit α-μNS polyclonal antiserum (left column) and goat α-TIAR polyclonal antibody (middle column) followed by Alexa-594 conjugated donkey α-rabbit IgG and Alexa-488 conjugated donkey α-goat IgG. Merged images containing DAPI-stained nuclei (blue) are shown (right column). μNS WT = wild type, bar = 10 μm.

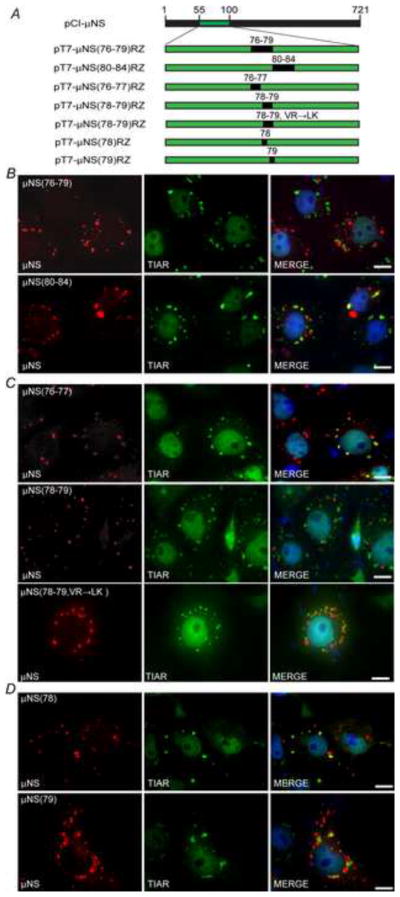

μNS amino-acids 78-79 are necessary for μNS localization to SGs

To further narrow the ten amino acid region identified as being important in μNS association with SGs, two point mutants were constructed in which either μNS amino acids 76-79 or 80-84 were mutated such that they encoded glycines/alanines in those four or five positions (Fig 3A). Plasmids expressing these mutants (pT7-μNS(76-79)RZ and pT7-μNS(80-84)RZ) were transfected in Cos-7 cells and at 23 h p.t. SGs were induced with SA and localization of μNS was examined by immunostaining using antibodies against μNS and TIAR. In these experiments μNS(76-79) showed both TIAR stained SGs and μNS stained VFLs, however, the two cytoplasmic structures did not overlap, suggesting a distinct loss of μNS localization to SGs (Fig 3B, top row). μNS(80-84) on the other hand presented a similar pattern of localization as seen in wild type μNS, with clearly overlapping μNS and TIAR signals in all SG structures and some μNS in VFLs that did not overlap with SGs (Fig 3B, bottom row). The absence of μNS localization to SGs in the μNS(76-79) mutant indicates that the amino acids responsible for μNS localization to SGs are found between residues 76 and 79.

Fig. 3. μNS amino acids 78 and 79 are necessary for localization to SGs.

(A) Illustration of plasmids used in mapping the μNS residues necessary for SG localization. Not to scale. (B–D) Cos-7 cells were transfected with (B) pT7-μNS(76-79)RZ (top) or pT7-μNS(80-84)RZ (bottom), (C) pT7-μNS(76-77)RZ (top), pT7-μNS(78-79)RZ (middle) or pT7-μNS (78-79, VR→LK)RZ (bottom), (D) pT7-μNS(78)RZ (top) or pT7-μNS(79)RZ (bottom) and at 23 h p.t. were treated with 0.5 mM SA for 1 h, fixed, and immunostained with rabbit α-μNS polyclonal antiserum (left column) and goat α-TIAR polyclonal antibody (middle column) followed by Alexa-594 conjugated donkey α-rabbit IgG and Alexa-488 conjugated donkey α-goat IgG. Merged images containing DAPI-stained nuclei (blue) are shown (right column). Bar = 10 μm.

To continue narrowing down the necessary amino acids residues for μNS localization to SGs, the previously identified four amino acid section was further split into two amino acid point mutants in which the native amino acids present in μNS at positions 76-77 or 78-79 were changed to glycine or alanine [pT7-μNS(76-77)RZ and pT7-μNS(78-79)RZ, Fig 3A]. Cos-7 cells were transfected with these plasmids and at 23 h p.t. cells were treated with SA for 1 h, at which point cells were fixed and immunostained with antibodies against μNS and TIAR. The μNS(76-77) mutant exhibited a pattern of localization with SGs that was similar to wild-type μNS, suggesting these residues were not involved in μNS localization to SGs (Fig. 3C, top row), however, though both SGs and VFLs were present in cells expressing μNS(78-79) (Fig. 3C, middle row) they did not overlap, suggesting that μNS residues 78-79 are necessary for μNS localization to SGs.

To further explore the role of μNS amino acids 78-79 in association with SGs, an additional mutant was created in which the valine and arginine residues at these positions were changed to the highly conserved amino-acid residues leucine and lysine [pT7μNS(78-79, VR→LK)RZ]. Cos-7 cells were transfected with this plasmid and at 23 h p.t. cells were treated with SA for 1 h, at which point cells were fixed and immunostained with antibodies against μNS and TIAR. While μNS(78-79, VR→LK) did not exhibit the complete loss of association with SGs seen in the original μNS(78-79) mutant, μNS association with SGs in these cells was visibly diminished relative to wildtype μNS (Fig. 3C, bottom row), further suggesting that μNS aminoacids 78-79 are necessary for maximum association between μNS and SGs.

To determine the individual contribution of amino acids 78 and 79 in μNS and SG localization, two plasmids containing single point mutations in either amino acid were constructed (pT7-μNS(78)RZ and pT7-μNS(79)RZ, Fig 3A) and μNS localization relative to SGs was examined following transfection. In these experiments, though the μNS association with SGs again appeared qualitatively weaker than that seen with wildtype μNS, both the μNS(78) and μNS(79) mutants showed some localization with SGs (Fig. 3D). These data indicate that mutation of amino acids 78 or 79 individually does not fully disrupt μNS localization to SGs, suggesting that mutation of both amino acids to non-conserved amino-acids is necessary to fully disrupt this localization. It should be noted that all of the above substitution mutations resulted in a μNS phenotype with delayed VFL formation and, at the time of IFA, the VFLs in these mutants appeared qualitatively smaller than those typically seen in cells expressing wildtype μNS. Experiments performed at later times post-transfection indicated that the mutant μNS proteins were able to form larger VFLs over time (data not shown). Differences in VFL size did not appear to impact μNS association with SGs as both SG-interacting [μNS(76-77)] and non SG-interacting μNS [μNS(78-79)] displayed the delayed VFL formation phenotype.

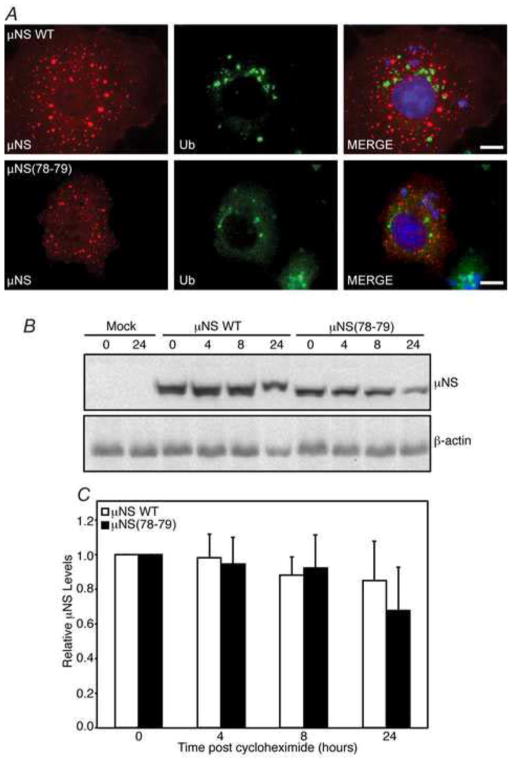

μNS(78-79) is not unstable or highly ubiquitinated

Creation of any mutation within a protein carries the possibility of inducing changes that result in misfolding, aggregation, ubiquitination, instability, and loss of protein function. To assess this possibility with μNS(78-79), we first examined ubiquitination of the protein by immunofluorescence assay. Cos-7 cells were transfected with either pCI-μNS or pT7-μNS(78-79)RZ and at 24 h p.t. were fixed and immunostained with antibodies against μNS and multi-ubiquitin. As has been previously reported, wild type μNS did not substantially colocalize with ubiquitin in these experiments, suggesting the protein is not misfolded (Broering et al., 2005) (Fig. 4A, top row). Similar to wild type μNS, there did not appear to be any colocalization between ubiquitin and μNS(78-79) (Fig 4A, bottom row), suggesting that introduction of glycine and alanine at amino acids 78 and 79 does not lead to substantial protein misfolding or ubiquitination.

Fig. 4. μNS(78-79) is not highly ubiquitinated or unstable.

Cos-7 cells were transfected with pCI-μNS or pT7-μNS(78-79)RZ. (A) At 24 h p.t. cells were fixed and immunostained with rabbit α-μNS polyclonal antiserum (left column) and mouse monoclonal α-multi-ubiquitin antibody (middle column) followed by Alexa-594 conjugated donkey α-rabbit IgG and Alexa-488 conjugated donkey α-mouse IgG. Merged images containing DAPI-stained nuclei (blue) are shown (right column). Bar = 10 μm. (B) At 24 h p.i., cells were treated with cycloheximide (100 μg/ml). Proteins were harvested at indicated times post-drug addition and immunoblotted with μNS and β-actin antibodies. (C) μNS levels were normalized to β-actin and numbers relative to time zero from 5 replicates with standard error of the averages are shown.

We additionally examined the stability of μNS(78-79) relative to wildtype μNS. Cos-7 cells were transfected with either pCI-μNS or pT7-μNS(78-79)RZ and at 24 h p.t, cells were treated with cycloheximide to inhibit further protein translation. At 0, 4, 8, and 24 h post drug-treatment, cells were harvested and protein samples were separated on SDS-PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose, and immunoblotted with antibodies against μNS or β-actin (Fig 4B). Although there was a consistent decrease in overall protein expression in the μNS(78-79)RZ samples relative to wildtype μNS, there was no statistical difference in degradation rates over multiple experiments between the mutant and wildtype proteins (Fig 4C), strongly suggesting that these mutations at μNS amino-acids 78-79 are not resulting in enhanced protein misfolding, ubiquitination, or degradation of the protein.

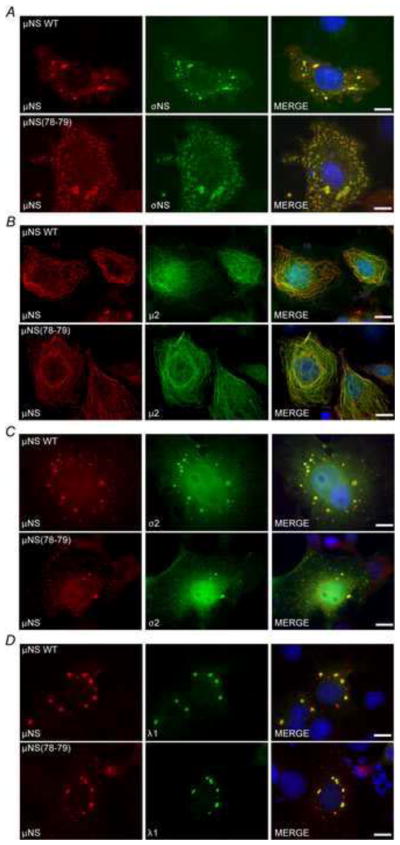

μNS(78-79) maintains association with virus proteins σNS, σ2, μ2 and λ1

A second test of functionality of a mutated protein is determining whether known roles of the protein are still active. Previous work has shown that in addition to forming the structural matrix of VFs, μNS interacts with many other MRV proteins and recruits or retains them in VFLs when both proteins are expressed in cells. In the case of the microtubule associated μ2 protein, instead of being retained in μNS-formed VFLs, μNS associates with μ2 on microtubules when both proteins are expressed in cells (Broering et al., 2004; Broering et al., 2002; Miller et al., 2010; Miller et al., 2003). The virus proteins that μNS has been shown to interact with include the non-structural σNS protein as well as the core proteins, μ2, λ1, λ2, λ3, and σ2. The interaction sites of all of these proteins have been mapped and several of them (σNS, μ2, λ1, and σ2) occur within the N-terminal third of μNS but do not directly overlap with μNS amino-acids 78-79 (Miller et al., 2010). As we were interested in examining the role of the μNS interaction with SGs during virus infection using the μNS(78-79) mutant, this overlap represented a potential problem in that the mutation of amino acids 78-79 could interrupt those interactions. To determine if this was the case, pT7-μNS(78-79)RZ or pCI-μNS were each cotransfected into Cos-7 cells with plasmids expressing σNS, σ2, μ2, or λ1 and at 24 h p.t. cells were fixed and immunostained with antibodies against μNS and each of the virus proteins to determine whether the interaction between μNS(78-79) and each protein was maintained. In each case the expressed virus protein was colocalized with both wild type μNS and μNS(78-79), suggesting that the proteins maintained interaction with the mutant μNS (Fig 5A–D). The maintenance of these associations additionally suggests that the mutant protein maintains proper folding in order to sustain these interactions.

Fig. 5. μNS(78-79) maintains interaction with σNS, μ2, σ2, and λ1.

Cos-7 cells were co-transfected with pCI-μNS (top) or pT7-μNS(78-79)RZ (bottom) and (A) pCI-σNS, (B) pCI-μ2, (C) pCI-σ2, or (D) pCI-λ1 and at 24 h p.t. were fixed and immunostained with mouse polyclonal antiserum against μNS (left column) and rabbit polyclonal antiserum against σNS, μ2, or MRV-cores (middle column) followed by Alexa-594 conjugated donkey α-mouse IgG and Alexa-488 conjugated donkey α-rabbit IgG. Merged images containing DAPI-stained nuclei (blue) are shown (right column). Bar = 10 μm.

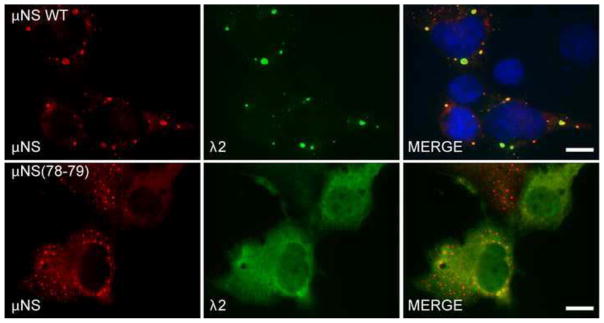

Mutation of μNS amino acids 78-79 disrupts μNS association with λ2

Like σNS, σ2, μ2, and λ1, core surface protein λ2 is also known to interact with μNS via its N terminal end, however, the interaction of λ2 protein is of particular interest because it has been shown that μNS amino acids 76–85 are necessary for this interaction, suggesting an increased possibility that the site we identified as being necessary for μNS localization to SGs may overlap with the λ2 association site (Miller et al., 2010). To determine the impact of mutating μNS amino acids 78-79 on its interaction with λ2, pCI-μNS or pT7-μNS(78-79)RZ were cotransfected with pCI-λ2 into Cos-7 cells and at 24 h p.t. cells were immunostained with antibodies against μNS and λ2. In these experiments, unlike the λ2 colocalization with wild-type μNS in VFLs (Fig 6, top row), in cells expressing μNS(78-79), λ2 did not localize to VFLs and was instead diffusely distributed throughout the transfected cells (Fig 6, bottom row). These findings suggest that in addition to being involved in μNS localization to SGs, μNS residues 78-79 are required for association with λ2.

Fig. 6. μNS(78-79) does not associate with λ2.

Cos-7 cells were co-transfected with pCI-μNS (top) or pT7-μNS(78-79)RZ (bottom) and pCI-λ2. At 24 h p.t. cells were fixed and immunostained with rabbit α-μNS polyclonal antiserum (left column) and mouse monoclonal antibody (7F4) against λ2 (middle column) followed by Alexa-594 conjugated donkey α-rabbit IgG and Alexa-488 conjugated donkey α-mouse IgG. Merged images containing DAPI-stained nuclei (blue) are shown (right column). μNS WT = wild type, bar = 10 μm.

μNS(78-79) is non-functional in rescue of recombinant virus using reverse genetics

To determine the viability of a virus containing a mutation within μNS amino-acids 78-79, a previously described four plasmid-based reverse genetics system was utilized in attempts to create recombinant virus (Boehme et al., 2011; Kobayashi et al., 2010). In an effort to increase efficiency of plasmid uptake and mimic the conditions used in wild type controls, the μNS(78-79) mutation was subcloned out of the pT7-μNS(78-79)RZ plasmid into the reverse genetics plasmid pT7-L2-M3T1L so that a total of four plasmids were used in both the wild type and mutant experiments. BHK-T7 cells were transfected with either the four wild type plasmids (pT7-L1-M2T1L, pT7-L2-M3T1L, pT7-L3-S3T1L, and pT7-M1-S1-S2-S4T1L), three wild type plasmids and pT7-L2-M3(78-79)T1L, or the three wild type plasmids without pT7-L2-M3T1L as a negative control. At 24, 48, and 72 h p.t., cell lysates were collected and standard MRV plaque assays were performed on L929 cells. In three separate experiments we were unable to rescue mutant virus containing the μNS(78-79) mutation while wild type virus was rescued to varying levels in each replicate (Table 1).

Table 1. Recombinant virus containing the μNS(78-79) mutation cannot be rescued via reverse genetics.

Titer of virus (PFU/ml) was obtained by counting plaques from three experimental replicates with three technical replicates at each of three time points following reverse genetics using either pT7-L2-M3-RZ(T1L) or pT7-L2-M3(78-79)-RZ(T1L) and the remaining three plasmids from the MRV four-plasmid reverse genetics set. TM = too many plaques to count.

| WT | (78-79) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Expt #1 | 96h | 540, 680, 680 | 0, 0, 0 |

| 72h | 140, 100, 90 | 0, 0, 0 | |

| 48h | 10, 0, 30 | 0, 0, 0 | |

| Expt #2 | 96h | 200, 270, 180 | 0, 0, 0 |

| 72h | 20, 20, 0 | 0, 0, 0 | |

| 48h | 0, 10, 0 | 0, 0, 0 | |

| Expt #3 | 96h | TM, TM, TM | 0, 0, 0 |

| 72h | 370, 260, 80 | 0, 0, 0 | |

| 48h | 210, 290, 200 | 0, 0, 0 | |

To address the possibility that a virus containing the μNS(78-79) mutation could exhibit delayed growth, six additional experiments were performed in which cell lysates were collected at 3, 5, and 7 days p.t. and the plaque assay procedure was modified to allow for longer incubation. In every additional attempt wild type virus was efficiently recovered but mutant virus was not (data not shown). This indicates that μNS amino acids 78-79 are important for successful de novo replication of MRV from reverse genetics plasmids, either as a result of loss of localization with SGs, loss of interaction with λ2, or for some other currently undefined reason.

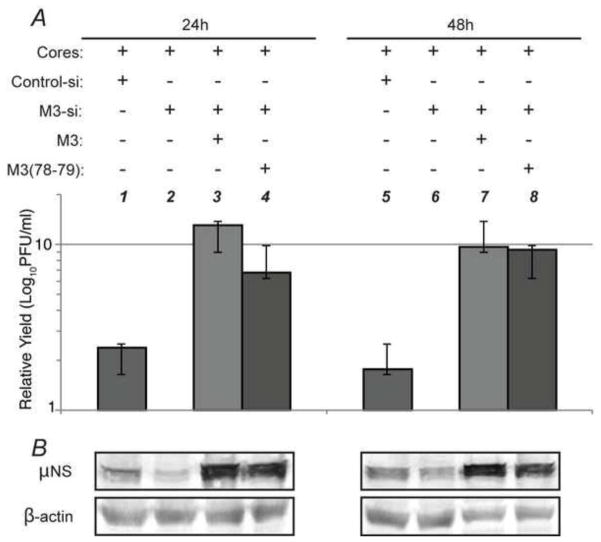

μNS(78-79) restores replication to near wildtype levels after M3 targeted siRNA knockdown

As we were unable to recover mutant virus using reverse genetics we utilized a previously described alternate approach (Arnold et al., 2008; Kobayashi et al., 2006) to assess the importance of μNS amino-acids 78-79 on MRV replication. In this approach, an siRNA targeted to specific nucleotides (194-212) in the T1L M3 gene was obtained commercially. Plasmids were then created in which silent mutations were introduced into the siRNA targeted area in either the wild type μNS (pT7M3RZ-si) or mutant μNS(78-79) (pT7M3(78-79)RZ-si) background such that when expressed, these M3 mRNAs would escape siRNA knockdown. BHK-T7 cells were then transfected with T1L core particles, control siRNA or M3siRNA, and either pT7M3RZ-si or pT7M3(78-79)RZ-si. Transfected cell lysates were collected at 24 and 48 h p.t. and viral yields were determined by standard plaque assay on L929 cells. In these experiments there was a 2-fold decrease in virus replication in the presence of the M3 siRNA relative to the control siRNA at both time points, indicating the M3 siRNA was knocking down core-produced wild type M3 leading to inhibition of virus replication. Cotransfection of the wild type μNS expressing plasmid that escapes M3 siRNA knockdown led to an 13-fold (24 h p.i.) and 10-fold (48 h p.i.) increase in virus replication relative to the samples with the M3 siRNA alone, suggesting that wild type μNS protein can rescue virus replication to levels even higher than those seen by cores in the control siRNA samples. Interestingly, cotransfection of μNS(78-79) was also able to rescue virus replication to similar levels (7-fold, 24 h p.i. and 9-fold, 48 h p.i.), although the rescue was somewhat less efficient and slower than wild type (Fig 7A). The relative levels of μNS protein expression in these experiments were confirmed with immunoblots against μNS (Fig. 7B). These results, when considered in light of our inability to rescue mutant virus with reverse genetics, suggest that while the mutant μNS(78-79) is unable to support de novo virus replication, it is able to contribute positively to viral replication in the presence of low levels of wild type μNS produced by cores that escape siRNA knockdown in these experiments.

Fig. 7. μNS(78-79) is able to rescue MRV replication following siRNA knockdown of M3.

(A) BHK-T7 cells were transfected with cores (all lanes), control siRNA (lanes 1 and 5), M3siRNA (lanes 2–4 and 6–8), and pT7M3RZ-si (lanes 3 and 7) or pT7M3(78-79)RZ-si (lanes 4 and 8). Cell lysates were collected at 24 h p.t. (lanes 1–4) and 48 h p.t. (lanes 5–8) and used for plaque assays (A) and immunoblot analysis (B). Samples were adjusted relative to the cores + M3siRNA sample (lanes 2 and 6) and the relative numbers were averaged from three experimental replicates with standard error of the averaged samples shown.

DISCUSSION

In this work we have shown that MRV protein μNS localizes with SGs in infected and transfected cells but that it is not capable of inducing or disrupting SGs in the absence of infection. Nonetheless, we sought to characterize this localization as both a potentially important step in MRV modulation of SGs during infection and to determine whether this interaction is necessary for viral replication. In the course of our studies we identified μNS amino-acids 78 and 79 as being necessary for μNS localization to SGs. When this μNS mutant was used in attempts to recover virus using reverse genetics, no viable virus was recovered, indicating that these amino acids play a necessary role in de novo MRV replication from reverse genetics plasmids. Additional rescue experiments using siRNA showed that the presence of low levels of wild type μNS in combination with mutant μNS(78-79) is able to rescue viral replication from M3 knockdown. In our investigation of the functionality of the μNS(78-79) mutant, we also found that it lost interaction with the virus core protein λ2. μNS recruitment of λ2 to VFs during infection likely is also a critical function of the protein. Therefore, while this region of μNS appears to be vital for successful de novo MRV replication, it is difficult to ascertain whether it is the loss of SG localization, λ2 association, or both that render the mutant non-viable in recovery of recombinant virus. Moreover, the inability to rescue recombinant mutant virus prevents further investigation that may determine if the μNS(78-79) mutant is defective in SG modulation or λ2 recruitment to VFs in infected cells. Although it is clear that these amino-acids are important for virus replication, without being able to separate the phenotypes of loss of μNS localization to SGs from loss of the λ2-μNS interaction it is unlikely that we will be able to use this mutant to elucidate the role that localization between μNS and SGs plays in viral replication.

Although amino acids 78-79 of μNS are necessary for localization with SGs, it remains unknown how and under what circumstances μNS interacts with SGs in infected cells. Some previous evidence suggests that μNS is capable of binding viral ss and dsRNA (Antczak and Joklik, 1992). Considering SGs are made up of numerous RNA-binding proteins, it is possible that the μNS interaction with SGs occurs indirectly through binding of the same RNA by both an SG localized protein and μNS. As the localization of μNS to SGs occurs in both infected and transfected cells expressing the μNS encoding M3 RNA, it may be possible that μNS is recruited to SGs indirectly, but specifically through a viral RNA interaction or non-specifically via non-specific RNA interactions. In addition, λ2 which functions as the guanylyl- and methyl-transferase for reovirus mRNAs (Luongo et al., 2000) may be associated with μNS through an indirect RNA intermediate, and mutation of μNS amino-acids 78-79 may destroy the ability of μNS to associate with RNA, thereby disrupting μNS interaction with both SGs and λ2. Additional experiments will be necessary to determine the RNA-binding capacity of this μNS mutant and the relationship between μNS RNA binding and SG and λ2 association.

It is also possible that μNS amino-acids 78 and 79 interact directly with an SG-localized protein. It is clear from our studies that the proteins most often associated with SG formation (TIAR, TIA-1, and G3BP) are not involved in this interaction as when μNS is expressed alone in cells, these proteins do not colocalize with VFS (Fig 1 and data not shown). Translation initiation factors and other cellular proteins that localize to SGs are additional possible recruitment proteins. It would seem sterically difficult for both λ2 and an as of yet unidentified SG protein to interact with a single μNS molecule at these residues simultaneously. However, it is possible that both interactions occur but at different times during infection or through independent interaction of different μNS molecules with either SGs or λ2. Our siRNA knockdown results may lend support to the idea that separate μNS molecules interact with different MRV proteins as the mutant μNS(78-79) was clearly unable to support de novo replication but when present in core-transfected cells expressing wild type μNS, the mutant was able to support replication at levels similar to cells transfected with wild type μNS. What is evident from our work thus far is that μNS does not require any other virus proteins for localization to SGs as it is found in SA-induced SGs in the absence of infection.

We have now shown that parental core particles as well as μNS are localized to SGs at early times in infection (Qin et al., 2009). This localization could be a strategy of the virus to increase viral replication as effective translation appears to be correlated with MRV disruption of SGs (Qin et al., 2011). If MRV cores localize to SGs, it would put them in a good location to coopt the sequestered translation factors in SGs. By appropriating the translation factors found in SGs, MRV mRNAs could presumably be translated more efficiently than if each mRNA needed to find each translational regulatory component separately. This colocalization may also have a nucleating effect for VFs, with viral translation occurring near SGs resulting in the genesis of new VFs consisting of μNS and other viral proteins. Much additional work will need to be performed to understand the relationship between SGs and MRV VFs.

Many other viruses have been shown to interact with SGs in infected cells in order to effectively replicate (Lloyd, 2012). Although the mechanisms used by other viruses to interact with the SG pathway vary greatly, it is clear that viral evasion and/or viral subversion of this pathway is an important part of the lifecycle of many viruses. While in most cases SGs are seen as a barrier to productive infection, the formation of SGs could prove beneficial in a viral infection if their presence also prevents host translation or their formation results in a convenient accumulation of cellular translational components for virus usage. In a situation in which SG formation is beneficial, it is likely that the virus will need a way to disrupt these SGs or “pull” the necessary components from SGs. In MRV it appears that μNS could function in that capacity but more research is needed to show if this is truly the case.

METHODS

Cells and Reagents

Cos-7 cells were maintained in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM) (Invitrogen Life Technologies) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (Atlanta Biologicals) and penicillin-streptomycin (100 IU/ml; Mediatech). BHK-T7 cells (Buchholz et al., 1999) were maintained in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM) (Sigma) containing 10% fetal bovine serum, penicillin-streptomycin (100 IU/ml), L-Glutamine (2 nM; Mediatech), Non-Essential Amino Acids (Invitrogen Life Technologies), and Fungazone (25 ng/ml; Invitrogen) with 1 mg/ml of G418 (Alexis Biochemical) added every other passage to maintain the T7 polymerase. L929 cells were maintained in Minimum Essential Medium with Joklik Modification (Sigma) containing 5% fetal bovine serum, 5% bovine calf serum (HyClone Laboratories), penicillin-streptomycin (100 IU/ml), and L-Glutamine (4 nM). The commercial primary antibodies used in immunofluorescence assays were as follows: goat polyclonal anti-TIAR (α-TIAR) antibody (sc-1749; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and mouse monoclonal anti-multi-ubiquitin antibody (D071-3; Medical & Biological Laboratories Co., LTD). Rabbit polyclonal antiserum against μNS, rabbit polyclonal antiserum against MRV-core, rabbit polyclonal antiserum against μ2, rabbit polyclonal antiserum against σNS, and mouse monoclonal antibody (7F4) against λ2 have been previously described (Broering et al., 2000; Broering et al., 2002; Gillian and Nibert, 1998; Virgin et al., 1991). The mouse polyclonal antiserum (174) against μNS was created at the Iowa State University Hybridoma Facility using peptides against μNS amino acids 178–197 and 282–301 synthesized using a Multiple Antigen Peptide System. The secondary antibodies used in immunofluorescence experiments were as follows: Alexa 488- or Alexa 594-conjugated donkey α-mouse, α-rabbit, or α-goat IgG antibodies (Invitrogen). Primary antibodies used in immunoblots were rabbit polyclonal antiserum against μNS and anti-β-actin antibody (Cell Signaling #4967). The secondary antibody used was goat α-rabbit AP conjugate (Bio-Rad). Sodium arsenite (SA) (Sigma-Aldrich) was used where indicated at a final concentration of 0.5 mM. Cycloheximide (Sigma-Aldrich) was used where indicated at a final concentration of 100 μg/ml.

Viruses

Viral preps were grown in six, five layer multi-flasks (BD Falcon #353144) that were each seeded with at least 7×106 L929 cells and 35 ml of media per layer. Flasks were incubated at 37°C until confluent at which point they were infected with a pfu of 5 in 50 ml of fresh media. Flasks were incubated for 1 h at room temp with the virus/media solution being mixed via the mixing port every 10–15 min. Fresh media was added back to the flask and flasks were incubated at 37°C until 80% cell death was observed. Virus was collected by centrifugation of media and cell debris at 3,000 × g for 10 min in 225 ml tubes (BD Falcon #352075). Cell pellets were resuspended in a total of 8 ml HO buffer (250 nM NaCl, 10 mM Tris, pH 7.4), combined, and frozen at −80°C. T3DC virions were purified as described previously (Mendez et al., 2000), using Vertrel reagent (DuPont) in place of Freon and stored in dialysis buffer (150 mM NaCl,10 mM Tris, pH 7.4, 10 mM MgCl2) at 4°C. The superscript C in T3DC is used to differentiate the T3D strain used in this study from a T3D strain (T3DN/T3DF) that has previously been shown to differ in M1 gene sequence, factory morphology, and μ2 ubiquitination phenotype (Miller et al., 2004). We refer to the virus as T3D throughout the manuscript. Viral titers (CIU) were determined on Cos-7 cells as previously described (Qin et al., 2011). Plaque assays were performed in 6 well dishes seeded with 1.2×106 L929 cells per well 24 h prior to infection and overlay. For reverse genetics experiments, cells were overlaid with 100 μl of cell lysate and incubated for 1 h at room temp with shaking every 10–15 min. For the initial three reverse genetics experiments (Table 1), 3 ml of equal parts 2% Bacto-Agar (BD) in H2O and 2X199 (Sigma) mixture with 10 ng/ml Trypsin (Worthington) was immediately overlaid on the L929 monolayer following incubation. For the six additional reverse genetics experiments, infected monolayers were incubated with fresh media at 37°C for at least 1 h before agar overlay. This treatment resulted in increased time to visualize plaques before complete cell death and was utilized to compensate for potential decreases in replication kinetics of mutant virus. For the siRNA plaque assays cell lysates were serially diluted and 100 μl of each dilution was incubated on the cells for 1 h at room temp with shaking every 10–15 min prior to agar overlay.

Plasmid Creation

Clones (all T1L) pCI-μNS, pCI-μNS(55-721), pCI-μNS(65-721), pCI-μNS(75-721), pCI-μNS(85-721), pCI-μNS(95-721), pCI-σNS, pCI-σ2, pCI-μ2, pCI-λ1, and pCI-λ2 were described previously although pCI-μNS, pCI-σNS, pCI-σ2, pCI-μ2, pCI-λ1, and pCI-λ2 were referred to by their gene names (Broering et al., 2004; Broering et al., 2002; Miller et al., 2010; Miller et al., 2003; Parker et al., 2002). Parent plasmid pCIM3RZ was created by amplifying the viral M3 gene from purified dsRNA (T1L) using primers containing a SacI site and minimal CMV promoter upstream from the M3 5′ end and a SmaI site after the 3′ end. The PCR product was digested and ligated into SacI/SmaI sites upstream from a self-cleaving hepatitis δ ribozyme. pT7M3RZ was created by performing PCR on pCIM3RZ using a primer with a SacI site and T7 promoter upstream from the 5′ end of M3 and a primer with a AvaI site at the 3′ end of M3. The PCR product was purified and ligated into pCIM3RZ cut with SacI and AvaI. Mutants pT7-μNS(76-79)RZ and pT7-μNS(80-84)RZ were created by overlap PCR using primers containing nucleotide mutations resulting in four or five amino-acid changes within μNS (pCI-μNS(76-79); LVVR→AGAG, pCI-μNS(80-84); PFSSG→AGAAG) and the vector pT7M3RZ as template. PCR products were digested with NruI and SpeI and ligated into EcoRV and SpeI digested pBluescriptIIKS(−). Using SpeI and BclI restriction sites the respective mutations were each ligated into pT7M3RZ. Mutants pT7μNS(76-77)RZ (LV→AG), pT7μNS(78-79)RZ (VR→AG), pT7μNS(78)RZ (V→A), and pT7μNS(79)RZ (R→G) were created by overlap PCR using primers containing the indicated mutations and pT7μNS(76-79)RZ as template. The PCR products and vector pT7μNS(76-79)RZ were then digested with SpeI and BclI and ligated. Mutant pT7μNS(78-79, VR→LK)RZ was created using a gBlock (Integrated DNA Technologies) containing the desired mutations and BbvCI and PciI restriction sites. pT7μNS(78-79)RZ and the gBlock were digested with BbvCI and PciI, and ligated. The reverse genetics mutant pT7-L2-M3(78-79)-RZ(T1L) was created by digestion of pT7-μNS(78-79)RZ and pT7-L2-M3-RZ(T1L) (Kobayashi et al., 2010) with PshAI and AgeI and ligation of the digested mutant fragment into the digested reverse genetics plasmid. The wild type (pT7M3RZ-si) and mutant (pT7M3(78-79)RZ-si) plasmids used in the siRNA knockdown experiments were modified from pT7M3RZ-T1L and pT7μNS(78-79)RZ to contain three silent mutations in the siRNA recognition sequence by using PCR primers containing the mutations and restriction sites EcoNI and AvaI to insert the PCR product into the parent plasmids. All plasmids were positively selected by restriction enzyme digest and confirmed by nucleotide sequencing. Primer sequences are available on request.

Transfections and Infections

Cos-7 cells were seeded onto 6-well cell culture plates at 1.5×105 per well containing 18 mm diameter coverslips the day before transfection/infection. To infect samples, media was removed from cells and T3DC at a CIU of 1 was diluted into phosphate buffered saline (PBS) [137 mM NaCl, 3 mM KCl, 8 mM Na2HPO4 (pH 7.5)] containing 2 mM MgCl2 and adsorbed to cells for 1 h, after which cells were overlaid with DMEM and incubated at 37°C. To transfect cells 2.5 μg (one plasmid) or 2 μg (two plasmids) of plasmid DNA and 3μl of Trans-IT LT1 per μg of DNA were combined in 250 μl of Optimem media (Invitrogen Life Technologies), incubated for 20 min at room temp, and added to cell media. Cells were then incubated at 37°C for 16–24 hours and subjected to downstream assays.

Immunofluorescence Assay

Cells were washed once with PBS and fixed at room temperature for 15 min with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS. Fixed cells were washed three times with PBS, permeabilized by incubation with 0.2% Triton X-100 in PBS for 5 min, and then washed three times with PBS. Samples were blocked by a 5-min incubation with 2% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in PBS. Primary and secondary antibodies were diluted in 2% BSA in PBS. After blocking cells were incubated for 30 min with primary antibodies, washed three times with PBS, and then incubated for an additional 30 min with secondary antibodies. Cells were washed a final three times with PBS and mounted on slides with Prolong reagent with DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole dihydrochloride) (Invitrogen). Samples were examined and images acquired with a Zeiss Axiovert 200 inverted microscope equipped with fluorescence optics. Images were prepared using Photoshop and Illustrator software (Adobe Systems).

Immunoblot Assay

Cell lysates in protein loading buffer were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and transferred to nitrocellulose by electroblotting in transfer buffer (25 mM Tris, 192 mM Glycine, 15% Methanol [pH 8.3]). Nitrocellulose membranes were blocked in 5% BSA in PBS for 20 minutes and then primary antibodies were diluted in 5% BSA in PBS, added to membranes, and incubated overnight on a rocker at 4°C. Blots were then washed 3 times for 10 min with Tris buffered saline with Tween 20 (TBS-T; 20 mM Tris, 137 mM NaCl, 0.5% Tween-20, [pH 7.6]). After washing, AP conjugated secondary antibodies were incubated with the blots in 5% BSA in PBS for 4 h at room temp. Blots were washed another 3 times with TBS-T and were exposed using a chemiluminescent substrate Lumi-Phos™ (Thermo Scientific). Images were acquired and protein levels quantified using a Chemi-doc XRS camera and Quantity One software (Bio-Rad).

MRV Reverse Genetics

The reverse genetics transfection protocol was modified from Kobayashi et al 2010. 4×105 BHK-T7 cells were seeded onto 6-well plates and transfected with 2 μg each of specified reverse genetics plasmids in 340 μl of Optimem using 3 μl of Trans-IT LT1 per μg of DNA. In some experiments (Table 1) sample lysates were collected by two freeze-thaw cycles at 48, 72, or 96 h p.t. and plaque assays were performed as previously described. In other experiments (data not shown), samples were collected at 3, 5, or 7 days p.t. to compensate for potential decreases in replication kinetics of mutant virus prior to plaque assay.

siRNA and siRNA Transfections

Control siRNA (Thermo; ON-TARGETplus Non-targeting siRNA #1) and M3-si01 (Thermo; 5′-UACCUUAUCAGCAUGUGAAdTdT-3′) (Arnold et al., 2008) siRNA were acquired commercially and resuspended to a concentration of 40 μM. 17.5 μl (final concentration of 100 nM) of each siRNA, 1×1010 T1L viral cores, and 5 μg plasmid DNA were mixed with 15 μl Trans-IT LT1 and 500 μl Optimem and incubated for 20 min at room temperature and then added to 60 mm dishes seeded with BHK-T7 cells the previous day at a concentration of 9.5×105. Dishes were incubated at 37°C for 24 or 48 h and then either harvested into 100 μl of protein loading buffer for immunoblot analysis or subjected to two freeze/thaw cycles in preparation for plaque assays.

Highlights.

Mammalian orthoreovirus (MRV) μNS protein associates with stress granules (SGs) in cells.

μNS cannot induce or disrupt SGs when expressed alone.

Mutation of μNS amino-acids 78-79 disrupts association with SGs and viral core protein λ2.

Recombinant virus containing a μNS(78-79) mutation cannot be rescued.

μNS(78-79) is able to rescue replication following siRNA knockdown of wildtype μNS.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. Terry Dermody, Vanderbilt University Medical Center for the MRV reverse genetics system. We would also like to thank Missey Tegtmeyer for technical assistance and other members of the Miller laboratory for helpful discussions on the project and manuscript. This work was funded by a Roy J. Carver Charitable Trust Young Investigator grant and NIH NIAID R15AI090635 to CLM.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Agosto MA, Ivanovic T, Nibert ML. Mammalian reovirus, a nonfusogenic nonenveloped virus, forms size-selective pores in a model membrane. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2006;103:16496–16501. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605835103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson P, Kedersha N. Visibly stressed: the role of eIF2, TIA-1, and stress granules in protein translation. Cell Stress & Chaperones. 2002;7:213–221. doi: 10.1379/1466-1268(2002)007<0213:vstroe>2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antczak JB, Joklik WK. Reovirus genome segment assortment into progeny genomes studied by the use of monoclonal-antibodies directed against reovirus proteins. Virology. 1992;187:760–776. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(92)90478-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold MM, Murray KE, Nibert ML. Formation of the factory matrix is an important, though not a sufficient function of nonstructural protein μNS during reovirus infection. Virology. 2008;375:412–423. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2008.02.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barton ES, Forrest JC, Connolly JL, Chappell JD, Liu Y, Schnell FJ, Nusrat A, Parkos CA, Dermody TS. Junction adhesion molecule is a receptor for reovirus. Cell. 2001;104:441–451. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00231-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker MM, Peters TR, Dermody TS. Reovirus σNS and μNS proteins form cytoplasmic inclusion structures in the absence of viral infection. Journal of Virology. 2003;77:5948–5963. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.10.5948-5963.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boehme KW, Ikizler M, Kobayashi T, Dermody TS. Reverse genetics for mammalian reovirus. Methods. 2011;55:109–113. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2011.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broering TJ, Arnold MM, Miller CL, Hurt JA, Joyce PL, Nibert ML. Carboxyl-proximal regions of reovirus nonstructural protein μNS necessary and sufficient for forming factory-like inclusions. Journal of Virology. 2005;79:6194–6206. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.10.6194-6206.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broering TJ, Kim J, Miller CL, Piggott CD, Dinoso JB, Nibert ML, Parker JS. Reovirus nonstructural protein μNS recruits viral core surface proteins and entering core particles to factory-like inclusions. Journal of Virology. 2004;78:1882–1892. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.4.1882-1892.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broering TJ, McCutcheon AM, Centonze VE, Nibert ML. Reovirus nonstructural protein μNS binds to core particles but does not inhibit their transcription and capping activities. Journal of Virology. 2000;74:5516–5524. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.12.5516-5524.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broering TJ, Parker JSL, Joyce PL, Kim JH, Nibert ML. Mammalian reovirus nonstructural protein μNS forms large inclusions and colocalizes with reovirus microtubule-associated protein μ2 in transfected cells. Journal of Virology. 2002;76:8285–8297. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.16.8285-8297.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchholz UJ, Finke S, Conzelmann KK. Generation of bovine respiratory syncytial virus (BRSV) from cDNA: BRSV NS2 is not essential for virus replication in tissue culture, and the human RSV leader region acts as a functional BRSV genome promoter. Journal of Virology. 1999;73:251–259. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.1.251-259.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandran K, Farsetta DL, Nibert ML. Strategy for nonenveloped virus entry: a hydrophobic conformer of the reovirus membrane penetration protein μ1 mediates membrane disruption. Journal of Virology. 2002;76:9920–9933. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.19.9920-9933.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chappell JD, Gunn VL, Wetzel JD, Baer GS, Dermody TS. Mutations in type 3 reovirus that determine binding to sialic acid are contained in the fibrous tail domain of viral attachment protein σ1. Journal of Virology. 1997;71:1834–1841. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.3.1834-1841.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dales S. Replication of animal viruses as studied by electron microscopy. American Journal of Medicine. 1965;38:699. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(65)90191-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dang YJ, Kedersha N, Low WK, Romo D, Gorospe M, Kaufman R, Anderson P, Liu JO. Eukaryotic initiation factor 2α-independent pathway of stress granule induction by the natural product pateamine A. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2006;281:32870–32878. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M606149200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebert DH, Deussing J, Peters C, Dermody TS. Cathepsin L and cathepsin B mediate reovirus disassembly in murine fibroblast cells. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2002;277:24609–24617. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M201107200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garaigorta U, Heim MH, Boyd B, Wieland S, Chisari FV. Hepatitis C Virus (HCV) Induces Formation of Stress Granules Whose Proteins Regulate HCV RNA Replication and Virus Assembly and Egress. Journal of Virology. 2012;86:11043–11056. doi: 10.1128/JVI.07101-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilks N, Kedersha N, Ayodele M, Shen L, Stoecklin G, Dember LM, Anderson P. Stress granule assembly is mediated by prion-like aggregation of TIA-1. Molecular Biology of the Cell. 2004;15:5383–5398. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-08-0715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillian AL, Nibert ML. Amino terminus of reovirus nonstructural protein σNS is important for ssRNA binding and nucleoprotein complex formation. Virology. 1998;240:1–11. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.8905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imani F, Jacobs BL. Inhibitory activity for the interferon-induced protein-kinase is associated with the reovirus serotype-1-σ3-protein. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1988;85:7887–7891. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.21.7887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katsafanas GC, Moss B. Colocalization of transcription and translation within cytoplasmic poxvirus factories coordinates viral expression and subjugates host functions. Cell Host & Microbe. 2007;2:221–228. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2007.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kedersha N, Anderson P. Stress granules: sites of mRNA triage that regulate mRNA stability and translatability. Biochemical Society Transactions. 2002;30:963–969. doi: 10.1042/bst0300963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khaperskyy DA, Hatchette TF, McCormick C. Influenza A virus inhibits cytoplasmic stress granule formation. Faseb Journal. 2012;26:1629–1639. doi: 10.1096/fj.11-196915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim WJ, Kim JH, Jang SK. Anti-inflammatory lipid mediator 15d-PGJ2 inhibits translation through inactivation of eIF4A. EMBO Journal. 2007;26:5020–5032. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi T, Chappell JD, Danthi P, Dermody TS. Gene-specific inhibition of reovirus replication by RNA interference. Journal of Virology. 2006;80:9053–9063. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00276-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi T, Ooms LS, Chappell JD, Dermody TS. Identification of Functional Domains in Reovirus Replication Proteins μNS and μ2. Journal of Virology. 2009;83:2892–2906. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01495-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi T, Ooms LS, Ikizler M, Chappell JD, Dermody TS. An improved reverse genetics system for mammalian orthoreoviruses. Virology. 2010;398:194–200. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2009.11.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindquist ME, Lifland AW, Utley TJ, Santangelo PJ, Crowe JE. Respiratory Syncytial Virus Induces Host RNA Stress Granules To Facilitate Viral Replication. Journal of Virology. 2010;84:12274–12284. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00260-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd RE. How do viruses interact with stress-associated RNA granules? PLoS Pathogens. 2012;8:e1002741. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luongo CL, Reinisch KM, Harrison SC, Nibert ML. Identification of the guanylyltransferase region and active site in reovirus mRNA capping protein λ2. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2000;275:2804–2810. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.4.2804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazroui R, Sukarieh R, Bordeleau ME, Kaufman RJ, Northcote P, Tanaka J, Gallouzi I, Pelletier J. Inhibition of ribosome recruitment induces stress granule formation independently of eukaryotic initiation factor 2α phosphorylation. Molecular Biology of the Cell. 2006;17:4212–4219. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-04-0318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCutcheon AM, Broering TJ, Nibert ML. Mammalian reovirus M3 gene sequences and conservation of coiled-coil motifs near the carboxyl terminus of the μNS protein. Virology. 1999;264:16–24. doi: 10.1006/viro.1999.9990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEwen E, Kedersha N, Song BB, Scheuner D, Gilks N, Han AP, Chen JJ, Anderson P, Kaufman RJ. Heme-regulated inhibitor kinase-mediated phosphorylation of eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2 inhibits translation, induces stress granule formation, and mediates survival upon arsenite exposure. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2005;280:16925–16933. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M412882200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendez II, Hermann LL, Hazelton PR, Coombs KM. A comparative analysis of Freon substitutes in the purification of reovirus and calicivirus. Journal of Virological Methods. 2000;90:59–67. doi: 10.1016/s0166-0934(00)00217-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller CL, Arnold MM, Broering TJ, Hastings CE, Nibert ML. Localization of mammalian orthoreovirus proteins to cytoplasmic factory-like structures via nonoverlapping regions of μNS. Journal of Virology. 2010;84:867–882. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01571-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller CL, Broering TJ, Parker JS, Arnold MM, Nibert ML. Reovirus σNS protein localizes to inclusions through an association requiring the μNS amino terminus. Journal of Virology. 2003;77:4566–4576. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.8.4566-4576.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller CL, Parker JS, Dinoso JB, Piggott CD, Perron MJ, Nibert ML. Increased ubiquitination and other covariant phenotypes attributed to a strain- and temperature-dependent defect of reovirus core protein μ2. Journal of Virology. 2004;78:10291–10302. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.19.10291-10302.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mokas S, Mills JR, Garreau C, Fournier MJ, Robert F, Arya P, Kaufman RJ, Pelletier J, Mazroui R. Uncoupling Stress Granule Assembly and Translation Initiation Inhibition. Molecular Biology of the Cell. 2009;20:2673–2683. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-10-1061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mora M, Partin K, Bhatia M, Partin J, Carter C. Association of reovirus proteins with the structural matrix of infected-cells. Virology. 1987;159:265–277. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(87)90464-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nibert ML, Fields BN. A carboxy-terminal fragment of protein μ1/μ1C is present in infectious subvirion particles of mammalian reoviruses and is proposed to have a role in penetration. Journal of Virology. 1992;66:6408–6418. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.11.6408-6418.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onomoto K, Jogi M, Yoo JS, Narita R, Morimoto S, Takemura A, Sambhara S, Kawaguchi A, Osari S, Nagata K, Matsumiya T, Namiki H, Yoneyama M, Fujita T. Critical Role of an Antiviral Stress Granule Containing RIG-I and PKR in Viral Detection and Innate Immunity. PLOS One. 2012:7. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0043031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pain VM. Initiation of protein synthesis in eukaryotic cells. European Journal of Biochemistry. 1996;236:747–771. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1996.00747.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parashar UD, Burton A, Lanata C, Boschi-Pinto C, Shibuya K, Steele D, Birmingham M, Glass RI. Global Mortality Associated with Rotavirus Disease among Children in 2004. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2009;200:S9–S15. doi: 10.1086/605025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker JSL, Broering TJ, Kim J, Higgins DE, Nibert ML. Reovirus core protein μ2 determines the filamentous morphology of viral inclusion bodies by interacting with and stabilizing microtubules. Journal of virology. 2002;76:4483–4496. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.9.4483-4496.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin Q, Carroll K, Hastings C, Miller CL. Mammalian orthoreovirus escape from host translational shutoff correlates with stress granule disruption and is independent of eIF2α phosphorylation and PKR. Journal of Virology. 2011;85:8798–8810. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01831-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin Q, Hastings C, Miller CL. Mammalian orthoreovirus particles induce and are recruited into stress granules at early times postinfection. Journal of Virology. 2009;83:11090–11101. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01239-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhim JS, Mayor HD, Jordan LE. Cytochemical, fluorescent-antibody and electron microscopic studies on growth of reovirus (ECHO 10) in tissue culture. Virology. 1962;17:342–355. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(62)90125-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samuel CE, Duncan R, Knutson GS, Hershey JWB. Mechanism of interferon action - increased phosphorylation of protein-synthesis initiation-factor eIF2α in interferon-treated, reovirus-infected mouse-L929 fibroblasts in vitro and in vivo. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1984;259:3451–3457. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmechel S, Chute M, Skinner P, Anderson R, Schiff L. Preferential translation of reovirus mRNA by a σ3-dependent mechanism. Virology. 1997;232:62–73. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.8531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz-Cornil I, Mertens P, PC, Contreras V, Hemati B, Pascale F, Bréard E, Mellor PS, MacLachlan N, James, Zientara S. Bluetongue virus: virology, pathogenesis and immunity. Vet Res. 2008;39:46. doi: 10.1051/vetres:2008023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shatkin AJ, Both GW. Reovirus messenger-RNA - transcription and translation. Cell. 1976;7:305–313. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(76)90159-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JA, Schmechel SC, Raghavan A, Abelson M, Reilly C, Katze MG, Kaufman RJ, Bohjanen PR, Schiff LA. Reovirus induces and benefits from an integrated cellular stress response. Journal of Virology. 2006;80:2019–2033. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.4.2019-2033.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JA, Schmechel SC, Williams BRG, Silverman RH, Schiff LA. Involvement of the interferon-regulated antiviral proteins PKR and RNase L in reovirus-induced shutoff of cellular translation. Journal of Virology. 2005;79:2240–2250. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.4.2240-2250.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao YZ, Farsetta DL, Nibert ML, Harrison SC. RNA synthesis in a cage - Structural studies of reovirus polymerase λ3. Cell. 2002;111:733–745. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)01110-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tourriere H, Chebli K, Zekri L, Courselaud B, Blanchard JM, Bertrand E, Tazi J. The RasGAP-associated endoribonuclease G3BP assembles stress granules. Journal of Cell Biology. 2003;160:823–831. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200212128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Virgin HW, Mann MA, Fields BN, Tyler KL. Monoclonal-antibodies to reovirus reveal structure-function-relationships between capsid proteins and genetics of susceptibility to antibody action. Journal of Virology. 1991;65:6772–6781. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.12.6772-6781.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White JP, Cardenas AM, Marissen WE, Lloyd RE. Inhibition of cytoplasmic mRNA stress granule formation by a viral proteinase. Cell Host & Microbe. 2007;2:295–305. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2007.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White JP, Lloyd RE. Poliovirus Unlinks TIA1 Aggregation and mRNA Stress Granule Formation. Journal of Virology. 2011;85:12442–12454. doi: 10.1128/JVI.05888-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yi ZG, Pan TT, Wu XF, Song WH, Wang SS, Xu Y, Rice CM, MacDonald MR, Yuan ZH. Hepatitis C Virus Co-Opts Ras-GTPase-Activating Protein-Binding Protein 1 for Its Genome Replication. Journal of Virology. 2011;85:6996–7004. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00013-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yue ZY, Shatkin AJ. Double-stranded RNA-dependent protein kinase (PKR) is regulated by reovirus structural proteins. Virology. 1997;234:364–371. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.8664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Chandran K, Nibert ML, Harrison SC. Reovirus μ1 structural rearrangements that mediate membrane penetration. Journal of Virology. 2006;80:12367–12376. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01343-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zweerink HJ, Joklik WK. Studies on intracellular synthesis of reovirus-specified proteins. Virology. 1970;41:501–518. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(70)90171-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]