Abstract

Objective

Although widely studied in adults, the link between lifetime adversities and suicidal ideation in youth is poorly understood. The purpose of this study was to explore this link in adolescents.

Methods

The analyses used a sample of 740 16-year-old youth in the LONGSCAN sample, and distinguished between childhood (before the age of 12) and adolescent (between age 12 and age 16) adversities.

Results

There was a significant link between cumulative lifetime adversities and suicidal ideation. There was no evidence that this link was moderated by gender. Childhood adversities moderated the effects of adolescent adversities on suicidal ideation; effects of adolescent adversities were strongest at low levels of childhood adversities. There was also some evidence supporting a specific cumulative model of the effects of adversities on suicidal ideation; the most predictive model included the sum of the following adversities: childhood physical abuse, childhood neglect, childhood family violence, childhood residential instability, adolescent physical abuse, adolescent sexual abuse, adolescent psychological maltreatment, and adolescent community violence.

Conclusion

The timing and nature of adversities are important in understanding youth suicidal ideation risk; in particular, adolescent maltreatment and community violence appear to be strong predictors. Preventing and appropriately responding to the abuse of adolescents has the potential to reduce the risk of suicidal ideation.

Keywords: Suicidal ideation, adverse experiences, maltreatment, witnessed violence

Youth suicidality is recognized as a significant public health problem both in the United States (USPHS, 1999) and in the world at large (Stein et al., 2010). Suicidal ideation is not only a potent early indicator of risk for attempted or completed suicide (ten Have et al., 2010), but is also associated with other negative outcomes such as sexual risk behavior, substance use, delinquency and violent behavior (Thompson et al., 2010). The negative outcomes of youth with suicidal ideation and attempts persist well into adulthood (Fergusson, Beautrais, & Horwood, 2003). Thus, to understand this public health problem, it is important to understand the factors that predict risk of suicidal ideation in youth. The purpose of the current study is to understand the role of adverse experiences, across the life span, in risk for suicidal ideation among adolescents, and to test different approaches for combining adverse experiences.

Adverse experiences include a variety of negative experiences across the lifetime, including child maltreatment, other family violence, poverty, and residential instability. Recently, reports by the World Health Organization (Bruffaerts et al., 2010; Stein et al., 2010) noted a strong relationship between childhood adversities and suicidal behavior in adults. This is consistent with earlier research that found an association between adversity and suicidal behavior, notably the ACE (Adverse Childhood Experiences) studies (Felitti et al., 1998). Other research (Nrugham et al., 2010; Stein et al., 2010) found similar results. As well, research on suicidal behavior has focused on particular adverse experiences, such as maltreatment (Bensley, Van Eenwyk, Spieker, & Schoder, 1999; Dinwiddie et al., 2000), witnessed violence (Lambert, Copeland, Linder, & Ialongo, 2008; Thompson et al., 2005), and transitions in residence or caregiver (Thompson et al., 2005). In some of this research, there is evidence for a dose-response effect across adversities, wherein the risk of suicidal ideation and suicidal behavior increases as does the number of adverse experiences (Bruffaerts et al., 2010; Stein et al., 2010).

How Adverse Experiences Combine to Influence Suicidal Ideation

The ACE studies examined a variety of different childhood experiences, and found a relatively strong dose-response effect on suicidal behavior and on other psychosocial and physical health outcomes (Felitti et al., 1998; Hillis, Anda, Dube, Felitti, Marchbanks, & Marks, 2004). Similar findings (e.g., Edwards, Holden, Felitti, & Anda, 2003) support a cumulative effect with higher numbers of different forms of adversity predicting subsequent outcomes. The mechanism by which such adverse experiences predict suicidal ideation has rarely been studied (Brodsky & Stanley, 2008), but there is some evidence that psychological distress and mental illness mediate this link (Dube et al., 2001; Thompson et al., in press).

The summing of different adverse childhood experiences, as is typically done, is criticized by Schilling, Aseltine, and Gore (2008) on several grounds. They focused their criticisms on models of effects of adverse experiences on psychosocial outcomes generally, but their criticisms are likely to apply to research on suicidal ideation as well. They argued that the cumulative adversity model, usually applied to the population as a whole, is likely to vary depending on sub-population categories such as gender, based on their finding of significant interactions between gender and adversities in predicting negative outcomes. Gender may moderate the effects of some risk factors on suicidal ideation; for example, Lambert and colleagues found that community violence had a stronger effect for boys than for girls. Thus, it is important to examine such possible interactions in predicting suicidal ideation using cumulative models of adversity.

More broadly, as Schilling noted (2008), most approaches to adversity assume an essentially general effects understanding. That is, it assumes that all forms of adversity are roughly similar in that they are traumatizing and predict future risk. This is contrasted with a differential effects model, where particular adverse experiences may be especially potent risk factors (Higgins & McCabe, 2001). From this perspective, the fact that the number of adversities predicts a variety of outcomes is likely to be driven by a smaller number of “high-impact” adversities, suggesting a way of refining the typical adversity model (Schilling et al., 2008). For example, sexual risk behavior is predicted by the number of different types of maltreatment experienced (suggesting support for a general effects model), but this effect is driven by the presence or absence of sexual abuse, which is highly correlated with number of different forms of maltreatment (Senn & Carey, 2010). Schilling and colleagues (2008) proposed an empirical approach to identify high-impact adversities, rather than use a priori definitions of forms of adversity that are most likely to predict particular outcomes (e.g., Clark, Thatcher, & Martin, 2010).

The bulk of research on outcomes of negative childhood experience has examined the unique effects of individual adversities. The goal of these studies has been one of identifying a single adversity that is most predictive, while only considering other adversities as nuisance or control variables (Seery et al., 2010). Most often this research has focused on individual adversities such as maltreatment or particular forms of maltreatment (Lansford, Miller-Johnson, Berlin, Dodge, Bates, & Pettit, 2007). Additionally, adverse experiences that are violent in nature (Nrugham et al., 2010; Stein et al., 2010), or that reflect poor family functioning (Bruffaerts et al., 2010; Pickles, Aglan, Collishaw, Messer, Rutter, & Maughan, 2010) have been examined as unique predictors of a host of negative outcomes, including suicidal ideation. It is important to point out that the decision to focus on certain adversities while controlling for others requires a priori decisions about what adversities are most salient. An empirical attempt to identify high-impact adversities from among a range of candidate adversities represents a middle ground between a general effects model, and the bulk of the research which attempts to identify the single strongest predictor. This middle ground, proposed by Schilling et al. (2008), can be referred to as a specific cumulative model.

Another Dimension: The Timing of Adverse Experiences and Suicidal Ideation

Most research on suicidal ideation and other outcomes of negative childhood experiences examine adult outcomes and treat childhood adverse experiences as a single block of experiences (e.g., Dube, Anda, Felitti, Chapman, Williamson, & Giles, 2001; Felitti et al., 1998; Schilling et al., 2008). This research typically fails to account for the possibility that the timing of negative childhood experiences is important in understanding later outcomes.

Research on child outcomes has been more likely to take timing into account, but this has rarely been applied to suicidal ideation as an outcome. For example, early work utilizing the LONGSCAN (LONGitudinal Studies of Child Abuse and Neglect) sample found child outcomes to be associated with the temporal patterns of exposure to maltreatment; maltreatment occurring over multiple developmental periods was associated with worse outcomes than maltreatment confined to a particular period (English, Graham, Litrownik, Everson, & Bangdiwala, 2005). More recent work using the same study sample to replicate the relationship between ACE variables (Felitti et al., 1998) and health outcomes in preadolescence found a distinction between childhood and adolescent adversity in predicting outcomes (Flaherty et al., 2009). A distinction between adolescent and earlier childhood adversity may be a useful first “cutting point” in examining the effects of timing. There is generally mixed evidence on this issue: some evidence suggests that more recent adverse experiences are more important (Flaherty et al., 2009; Thornberry, Ireland, & Smith, 2001), while other evidence suggests the opposite (Fisher et al., 2010; Korkeila et al., 2010). The limited available evidence specific to suicidal behavior is generally supportive of a stronger effect for more recent adverse experiences (Bruffaerts et al., 2010). Previous research from LONGSCAN focused on adolescent adverse experiences, but did not compare these to adverse experiences occurring in childhood (Thompson et al., in press). Similarly, Pickles and colleagues (2010) predicted adult suicidal ideation contrasting the effects of adverse experiences occurring in adulthood and adolescence, but failed to examine childhood adversities. There is a clear need for more research on the effects of the timing of adverse experiences on suicidal ideation.

Such a comparison between the effects of childhood and adolescent adversity is important, but it is also critical to examine the interplay between these experiences. From a variety of perspectives (stress sensitization or vulnerability-stress models: McLaughlin, Conron, Koenen, & Gilman, 2010; Kindling: Schumm, Stines, Hobfoll, & Jackson, 2005), early adversities may make an individual more vulnerable to negative outcomes in response to more recent adversities. Such a view has some empirical support (Korkeila et al., 2010). Conversely, moderate levels of early adversities may protect against the negative effects of more recent adversities, by “inoculating” against these effects (Seery et al., 2010). Both of these perspectives suggest that there is an interaction between early and more recent adverse experiences to predict negative outcomes, with the interaction effect, or moderation, either showing that early childhood adversities increase negative outcomes in response to later adolescent adversities (i.e., vulnerability-stress) or decrease negative outcomes of adolescent adversities (i.e., stress inoculation). Most commonly, the negative outcomes examined are depression and/or PTSD, rather than suicidal behavior (Korkeila et al., 2010; Schumm et al., 2005; Seery et al., 2010). Finally, it is possible that different adversities have stronger or weaker influence depending on the timing of exposure. Again, these issues have largely been neglected in understanding suicidal ideation.

Current Study

The purpose of the current study was to better understand the link between lifetime adversities and suicidal ideation in a high-risk population, applying recent refinements in understanding the effects of adverse experiences (Schilling et al., 2008) to suicidal ideation in particular. Specifically, we were interested in examining the following hypotheses:

Lifetime cumulative adversities are associated with suicidal ideation

Gender moderates the effects of lifetime cumulative adversities on suicidal ideation.

- Adolescent adversities are more potent predictors of suicidal ideation than childhood adversities; however

- Childhood adversities moderate the effects of adolescent adversities on suicidal ideation; and

- The effects of cumulative adversities are due to the effects of particular adversities, and taking these particular adversities into account improves the predictive utility of both childhood and adolescent adversities.

Methods

Sample and Design

The sample used in the current analyses was taken from the LONGSCAN studies. LONGSCAN is a consortium of studies using common instruments and interview protocols, located at five different sites across the United States. Each site recruited child-caregiver dyads into the study at age 4 or 6 based on a variety of selection criteria. One site included children that were at high risk for maltreatment (based on attendance at pediatric clinics serving high risk populations), two sites included children who had been reported for maltreatment, and two sites included both children who had been reported as maltreated and children who were identified as at risk, based on demographic risk factors. Detailed information on design and recruitment are available from Runyan et al. (1998).

Data collection consisted of face-to-face interviews conducted at child ages 4, 6, 8, 12, 14, and 16, with briefer telephone interviews during intervening ages between 4 and 16 (i.e., ages 5, 7, 9, 10, 11, 13, and 15). At each interview point, children and caregivers were interviewed separately. As well, there was periodic ongoing review of Child Protective Services (CPS) records in local jurisdictions or states where participating sites were located.

All participants with complete data on the outcome variable (suicidal ideation) assessed at age 16 were included in the current analyses. Of the baseline sample (1354 dyads), 54.7% (740) had outcome data at age 16, and were included in the analyses. There were no differences in baseline demographic (gender, race, caregiver education) data between those included in the current analyses and those not included. The description of the current sample is presented in Table 1. As can be seen, the sample was roughly evenly split on gender lines. Somewhat more than half of the sample was African American. The sample had quite high mean lifetime rates of adversity (nearly five adversities), with more childhood adversities than adolescent adversities. The most common overall adversities were non-family violence and residential instability. Residential instability was very common in childhood, as were neglect, caregiver instability, and psychological maltreatment. Non-family violence was by far the most common adversity in adolescence. Across childhood and adolescence, sexual abuse and family violence were the least frequent adversities. Neglect was also relatively uncommon in adolescence. There were few gender differences in exposure to adversities, with two exceptions. Overall, and within each time frame, girls were more likely to have experienced sexual abuse and psychological abuse. There was no gender difference in overall number of adversities.

Table 1.

Description of the Sample (N = 740)

| Variable | % (N) or M (SD) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall/Cumulative | Childhood | Adolescence | |

| Suicidal Ideation | 8.9% (66) | ||

| Demographics | |||

| Site | |||

| Eastern | 19.9% (147) | ||

| Southern | 15.0% (111) | ||

| Midwestern | 16.5% (122) | ||

| Northwestern | 24.6% (182) | ||

| Southwestern | 24.1% (178) | ||

| Race | |||

| African American | 52.6% (389) | ||

| White | 25.4% (188) | ||

| Other | 22.0% (163) | ||

| Caregiver Education (Years) | 12.30 (2.19) | ||

| Biological mother in the home | 59.5% (440) | ||

| Gender | |||

| Female | 52.6% (389) | ||

| Male | 47.4% (351) | ||

| Specific Adversities | 4.83 (1.85) | 3.93 (1.90) | 2.50 (1.58) |

| Physical Abuse | 54.1% (400) | 43.1% (319) | 25.5% (189) |

| Sexual Abuse | 32.4% (240)* | 25.5% (189)* | 10.4% (77)* |

| Psychological Maltreatment | 64.9% (480)* | 53.8% (398)* | 34.9% (258)* |

| Neglect | 60.5% (448) | 59.3% (439) | 10.1% (750 |

| Family Violence | 30.5% 9226) | 19.2% (142) | 17.0% (126) |

| Non-Family Violence | 89.3% (661) | 58.8% (435) | 80.7% (597) |

| Caregiver Instability | 67.3% (498) | 56.5% (418) | 31.2% (231) |

| Residential Instability | 83.5% (618) | 76.4% (465) | 39.9% (295) |

| Number of Adversities | 4.83 (1.85) | 3.93 (1.90) | 2.50 (1.58) |

| 0 | 0.3% (2) | 3.1% (23) | 7.4% (55) |

| 1 | 2.8% (21) | 7.3% (54) | 23.6% (175) |

| 2 | 9.7% (72) | 15.4% (114) | 23.6% (175) |

| 3 | 13.6% (101) | 16.9% (125) | 19.1% (141) |

| 4 | 15.7% (116) | 16.1% (119) | 14.6% (108) |

| 5 | 17.7% (131) | 18.1% (134) | 7.7% (57) |

| 6 | 18.6% (138) | 14.6% (108) | 2.8% (21) |

| 7 | 15.7% (116) | 6.8% (50) | 0.9% (7) |

| 8 | 5.8% (43) | 1.8% (13) | 0.1% (1) |

NOTE:

adversity was significantly more likely in girls than in boys.

Measures

Outcome Variable: Suicidal Ideation (age 16)

Suicidal ideation was assessed using a single item taken from the Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System (YRBSS), a Centers for Disease Control assessment of national rates of youth risk behavior that is conducted periodically (Brener, Kann, Kinchen, et al., 2004). This item read, “During the last 12 months, did you ever seriously consider attempting suicide?” In the LONGSCAN studies, this item was administered as part of a larger scale that included a subset of items from the YRBSS (Knight et al., 2009).

Control Variables: Demographics (Age 16)

At age 16, youth and caregivers self-reported on the demographic control variables of interest: child race, caregiver education, the presence of the biological mother in the home, and child gender. Subject identification numbers indicated from which site the youth had been recruited.

Adversities

For each adversity, the assessment and definition of childhood adversity (before age 12) is provided below, followed by the assessment and definition of adolescent adversity (between age 12 and 16). The presence of lifetime adversity was defined as experiencing an adversity during either childhood or adolescence. To obtain a cumulative adversity score (for lifetime and for both childhood and adolescence), these individual dichotomous indicators of adversity were summed.

Maltreatment (Physical Abuse, Sexual Abuse, Psychological Maltreatment and Neglect)

Childhood Maltreatment

Exposure to various forms of maltreatment in early life was measured in two ways: administrative record review and self-report of the participating youth. Every two years, administrative records of Child Protective Services were searched for allegations of maltreatment among participating youth. This review was done using the Modified Maltreatment Classification System (MMCS: English et al., 1997; a LONGSCAN-modified version of Barnett, Manly, & Cicchetti, 1993). The MMCS data collection included information on the date of the alleged maltreatment, the form which the alleged maltreatment took (physical abuse, sexual abuse, psychological maltreatment, and neglect), and other aspects of the alleged maltreatment. Physical abuse was defined as the non-accidental infliction of injury on the child or youth. Sexual abuse was defined as attempted or actual sexual contact between a responsible adult and the child or youth. Psychological maltreatment was defined as actions and statements by the caregiver that threaten psychological safety and security, self-esteem, or age-appropriate autonomy. Neglect was defined as failure to meet the child's physical needs and/or failure to provide supervision that ensures the child's safety.

This information was coded by research staff, typically masters or higher level; a subset of the information was coded by multiple rates to check for interrater reliability. Interrater reliability of this coding of administrative records is high (English et al., 1997), with kappas ranging from .73 for psychological abuse to .87 for physical abuse. In these analyses, reports of maltreatment that occurred before the age of 12 were included in the definition of childhood maltreatment for each type of maltreatment (physical abuse, sexual abuse, psychological maltreatment, or neglect).

In addition to this administrative data collection, the participants were asked, as part of the age 12 interview, to report whether they had had a variety of experiences that could be construed as physical, sexual, or psychological abuse. This self-report measure is described in more detail elsewhere, including the finding that there is a moderate correlation between the self-reports of maltreatment and the administrative record reviews (Everson et al., 2008). The instrument was designed so that stem questions focusing on the timing of the event (“Up to now, has a parent or other adult who was supposed to be supervising you or taking care of you ever done something to you like...” with yes/no responses which would describe specific abuse experiences (e.g., “bruised you, or given you a black eye?”, “put some part of their body or anything else inside your private parts or bottom?”).

As recommended in previous studies (Everson et al., 2008), information from both self-report and administrative report on maltreatment was integrated to identify exposure to each type of maltreatment. Youth were coded as having experienced a particular form of maltreatment early in life if indicated by either self-report or administrative data.

Adolescent Maltreatment

The assessment of adolescent maltreatment (occurring between age 12 and 16 was very similar to that of childhood maltreatment, as described above, with very similar reliability data. For this variable, MMCS data on reports of maltreatment were included, if they occurred between age 12 and age 16. For the self-report of adolescent maltreatment, a self-report measure was included at age 16 that was very similar to the measure described above, but used a different stem to indicate the timing of the self-reported maltreatment: “From the time you turned 12 up to now, has a parent or other adult who was supposed to be supervising you or taking care of you ever done something to you like...” In other respects, the assessment and definition of adolescent maltreatment was similar to that of childhood maltreatment.

Witnessed Violence (Family and Non-Family)

Childhood Witnessed Violence

At age 12, youth reported on whether they had witnessed any of 8 forms of violence, ranging from minor physical assault to severe forms of violence, using a LONGSCAN-developed questionnaire (Lewis et al., 2010; Knight et al., 2008). An example item is: “Have you ever seen someone being slapped, kicked, hit with something, or beaten up?” There is strong evidence for the validity of this measure; it correlates strongly with parent reports of youth exposure to violence and to a variety of indicators of youth outcomes (Lewis et al., 2010). Internal consistency is moderate, ranging from .58 to .74 (Thompson et al., 2007). In each case where such witnessed violence was endorsed, follow-up questions asked about the identity of the victim(s) and perpetrator(s), and how frequently the event had been witnessed in the past year and in the child's lifetime. For the current analyses, witnessed violence was classified as family violence if it involved a family member as either a perpetrator or a victim; if it did not include family members, it was classified as non-family violence; non-family violence is usually construed as community violence, but may include other forms of violence. The current analyses focused on the questions about whether each given form of violence had been witnessed in the child's lifetime.

Adolescent Witnessed Violence

At age 16, youth completed a very similar questionnaire, modified slightly to be age-appropriate (Knight et al., 2009), and including 7 rather than 8 items (because at age 16, items assessing witnessing a gun being pulled and a knife being pulled were combined in a single item; these were separate items at age 12). As was the case at the age 12 interview, follow-up questions asked youth the identity of the victim and perpetrator of each event, and whether the event had occurred in the past year or in the youth's lifetime. For these analyses, responses were dichotomized into family and non-family violence as noted above, and analyses focused on questions asking about violence witnessed in the past year.

Instability (Residential Instability and Caregiver Instability)

Childhood Instability

Instability was defined using data collected with the Child's Life Events measure, a project modified measure designed to assess events occurring in a specific year of the youth's life (Hunter et al., 2003), based on Sarason's Life Experiences Survey (Sarason, Johnson, & Siegel, 1978). These data were collected every year from age 4 through age 16. Caregiver instability was defined as any of the following changes in caregiver arrangements: caregivers’ marriage, separation, divorce, moving out of the home, the addition of a significant other into the home, or death of a caregiver. Residential instability was defined as instances where the child moved with the family to a new place, moved away from the family, spent time homeless or in a homeless shelter, the family was evicted, or the child stayed with friends or family because s/he had no place else to stay. Because of the nature of this measure (focusing on a variety of low base-rate events), internal consistency reliability is not appropriate. However, it correlates strongly with indicators of household dysfunction and child psychosocial outcomes (English, Thompson, Graham, & Briggs, 2005). Each form of instability was defined as present if it was endorsed at any interview between ages 4 and age 12.

Adolescent Instability

From ages 13 through 16, instability was measured in the same way as described above.

Analyses and Results

Cumulative Lifetime Adversities

Cumulative lifetime adversities predict teen suicidal ideation

To test the first hypothesis, a logistic regression was conducted, using the number of different adversities experienced to predict suicidal ideation, after controlling for the demographic and study variables (study site, child race, caregiver education, and the presence of the biological mother in the home). The result of this analysis is presented in Model 1 of Table 2. As can be seen, the number of lifetime adversities significantly predicted teen suicidal ideation. As well, and consistent throughout the analyses presented, there were significant effects of two control variables, gender and race. Girls were significantly more likely to report suicidal ideation than were boys, and African American youth were significantly less likely to report suicidal ideation than were White youth.

Table 2.

Modeling Teen Suicidal Ideation

| Model 1: Main Effects | Model 2: Gender Moderation | Model 3: Child vs. Adol. | Model 4: Child × Adol. | Model 5: Adversity/ Timing Specific | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR(CI) | OR(CI) | OR(CI) | OR(CI) | OR(CI) | |

| CONTROL | X2 = 34.39 Δ R2=. 089** | X2 = 34.39 Δ R2=. 089** | X2 = 34.39 Δ R2=. 089** | X2 = 34.39 Δ R2=. 089** | X2 = 34.39 Δ R2=. 089** |

| Site: Eastern (reference) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| Southern | 1.39 (0.53-3.64) | 1.35 (0.52 – 3.54) | 1.45 (0.55 – 3.80) | 1.58 (0.59 – 4.18) | 1.00 |

| Midwestern | 1.29 (0.49-3.36) | 1.28 (0.50 – 3.36) | 1.46 (0.56 – 3.85) | 1.48 (0.56 – 3.93) | 0.96 (0.31 – 3.01) |

| Northwestern | 1.83 (0.75-4.44) | 1.87 (0.77 – 4.55) | 2.01 (0.80 – 5.01) | 2.15 (0.86 – 5.40) | 0.71 (0.22 – 2.29) |

| Southwestern | 0.73 (0.28-1.91) | 0.73 (0.28 – 1.91) | 0.85 (0.32 – 2.30) | 0.89 (0.33 – 2.39) | 1.48 (0.53 – 4.13) |

| Race: White (reference) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.54 (0.17 – 1.70) |

| African American | 0.46 (0.25 – 0.84)* | 0.46 (0.25 – 0.84)* | 0.40 (0.21 – 0.74)* | 0.39 (0.21 – 0.73)* | 1.00 |

| Other | 0.59 (0.31 – 1.13) | 0.60 (0.31 – 1.15) | 0.58 (0.30 – 1.12) | 0.57 (0.29 – 1.10) | 0.35 (0.16 – 0.73)* |

| Caregiver Education (Years) | 1.04 (0.94 – 1.16) | 1.04 (0.94 – 1.16) | 1.04 (0.93 – 1.16) | 1.04 (0.93 – 1.16) | 0.46 (0.21 – 1.04) |

| Biological mother in the home | 1.04 (0.62 – 1.76) | 1.06 (0.62 – 1.79) | 1.01 (0.59 – 1.72) | 1.00 (0.59 – 1.71) | 1.00 (0.88 – 1.14) |

| Gender (Female) | 2.54 (1.53 – 4.21)** | 0.98 (0.16 – 5.95) | 2.52 (1.51 – 4.23)** | 2.52 (1.51 – 4.20)** | 1.26 (0.65 – 2.45) |

| PREDICTORS | X2 = 32.11 Δ R2= .079** | X2 = 32.23 Δ R2= .081** | X2 = 48.89 Δ R2= .119** | X2 = 53.14 Δ R2= .129** | X2 = 78.57 Δ R2= .187** |

| Cum. Adversities | 1.52 (1.30-1.78)** | 1.61 (1.33-1.95)** | |||

| Cum. Adversities × Gender | 0.85 (0.62-1.15) | ||||

| Child. Adversities | 1.08 (0.94 – 1.26) | 1.44 (1.05 – 1.97)* | |||

| Adol. Adversities | 1.62 (1.38 – 1.89)** | 2.49 (1.58 – 3.93)** | |||

| Child. × Adol. Adversities | 0.91 (0.84 – 1.00)* | ||||

| Low Impact – Childhood | 0.81 (0.62-1.06) | ||||

| Medium Impact – Childhood | 1.43 (1.08-1.89)* | ||||

| Low Impact – Adolescent | 0.93 (0.70-1.24) | ||||

| Medium Impact – Adolescent | 1.47 (0.81-2.69) | ||||

| High Impact – Adolescent | 2.57 (1.98-3.54)** | ||||

| Total R2 | .168** | .170** | .208** | .218** | .276** |

Note: OR = odds ratio; CI = Confidence interval; R2 = Nagelkerke pseudo-R2 estimate; Cum. Adversities = Lifetime cumulative adversities. The odds ratio estimates presented for the control variables are for those in the final model. For adversities, odds ratios represent the additional risk of suicidal ideation for each additional adversity; odds ratios greater than 1 indicate direct relationships; odds ratios lower than 1 indicate inverse relationships.

p < .05

p < .001.

Gender moderates the link between lifetime adversities and teen suicidal ideation

To test the second hypothesis, a logistic regression was conducted, using cumulative lifetime adversities and the interaction between lifetime adversities and gender to predict suicidal ideation, after controlling for the demographic and study variables (which included the main effect for gender). The result of this analysis is presented in Model 2 of Table 2. As can be seen, there was no significant interaction between gender and cumulative adversities and the main effect of cumulative adversities remained significant.

Examining the distinction between childhood and adolescent adversities

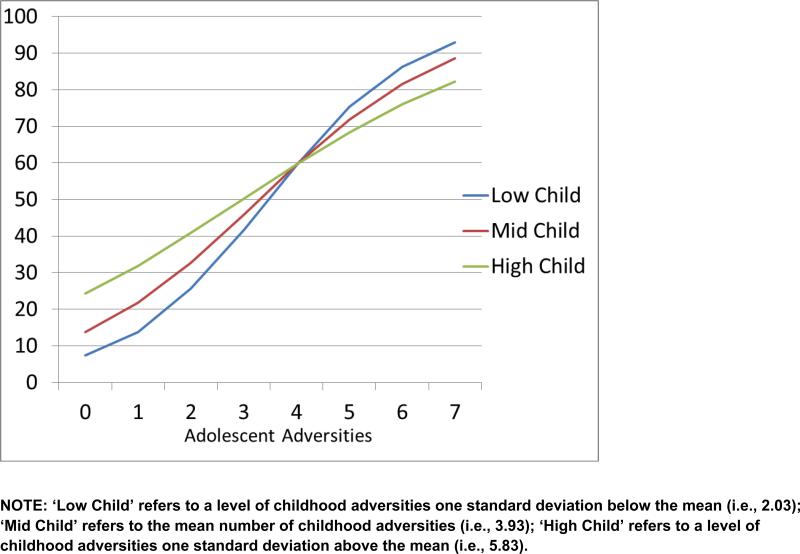

To test the third hypothesis (that adolescent adversities are more potent predictors of suicidal ideation than childhood adversities), as well as the hypothesis that childhood adversities moderate the effects of adolescent adversities), two steps were taken, both of which are presented in Table 2: 1) a logistic regression was conducted examining the effects, separately, of both childhood (i.e., before 12) and adolescent (i.e., between 12 and 16) adversities (Model 3); and 2) a logistic regression was conducted examining the effects of childhood adversities, adolescent adversities, and the interaction between the two variables (Model 4). As can be seen, when examining main effects, there is a significant effect of adolescent adversities, but not of childhood adversities. However, entering an interaction effect resulted in a significant interaction term, suggesting a moderating effect of childhood adversities. This interaction is presented graphically in Figure 1. As can be seen, the effects of adolescent adversities are strongest at low levels of childhood adversities; and this effect is reversed at high levels of childhood adversities. This is consistent with a vulnerability-stress model with low and moderate levels of adolescent adversities, but with a suppression effect at high (i.e., 5 or more) adolescent adversities.

Figure 1.

Interaction Between Childhood and Adolescent Adversities in Predicting Suicidal Ideation

Secondary analyses examined the potential role of gender as a moderator of these relationships in both Model 3 (moderating childhood adversity and adolescent adversity) and Model 4 (moderating childhood adversity, adolescent adversity and the interaction between childhood and adolescent adversity. In neither Model 3 nor Model 4 was any interaction with gender significant (maximum Wald = 1.23 for Model 3, maximum Wald = 0.56 for Model 4).

Examining the utility of adversity specific models

A second way of explicating the reduced effect of childhood adversities relative to adolescent adversities is to examine the precision of the definition of such adversities. Specifically, we followed a two-step process proposed by Schilling and colleagues (2008) to examine whether the relationships between adversities and suicidal ideation were attributable to the effects of particular adversities:

To estimate the relative impact of each adversity, we regressed suicidal ideation on each adversity separately, after taking into account the block of control variables. Because suicidal ideation was a dichotomous outcome, the effect sizes were classified into low, moderate and high, based on the recommendations of Allen and Le (2008) for estimating such effect sizes in logistic regressions.

Adversities for each combination of impact and timing of adversity (i.e., childhood and adolescence) were summed to produce scales representing: childhood low impact, childhood medium impact, adolescent low impact, adolescent medium impact, and adolescent high impact (there were no early high impact adversities detected in step 1). To examine the relative unique impact of each of these classes of adversities, these five adversity scores were entered simultaneously into a logistic regression after taking into account the block of control variables.

The results of Step 1 are summarized in Table 3. As can be seen, the impact of particular adversities varied, depending on whether they occurred during childhood or adolescence.

Table 3.

Impact size for individual adversities occurring during childhood(before age 12) and adolescence (between age 12 and age 16).

| IMPACT | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Adversity | LOW | MEDIUM | HIGH |

| Physical Abuse | C | A | |

| Sexual Abuse | C | A | |

| Psychological Maltreatment | C | A | |

| Neglect | A | C | |

| Family Violence | CA | ||

| Non-Family Violence | C | A | |

| Caregiver Instability | CA | ||

| Residential Instability | A | C | |

Note: C = childhood; A = adolescence.

The results of Step 2 are summarized in Model 5 of Table 2. As can be seen, the model including childhood and adolescent adversities separately summed by impact strongly predicted suicidal ideation. As well, moderate childhood adversities (which included physical abuse, neglect, family violence, and residential instability) and high adolescent adversities (which included physical abuse, sexual abuse, psychological maltreatment, and non-family violence) both uniquely predicted suicidal ideation. Secondary analyses found no significant moderating effect of gender on these relationships (maximum Wald = 2.06).

Discussion

Current Findings

The current analyses found a strong effect of the number of lifetime adverse experiences on risk for suicidal ideation. This finding is consistent with previous research examining other psychosocial outcomes (e.g., Hillis et al., 2004; Schilling et al., 2008) as well as suicidal behavior (Felitti et al., 1998; Stein et al., 2010). The effect of the number of adversities significantly explained suicidal ideation, after taking into account several demographic control variables. Of note, although there was a significant main effect of gender on suicidal ideation and on some adversities (girls reported higher rates of suicidal ideation and had higher rates of psychological maltreatment and sexual abuse), gender did not appear to influence the effects of adverse experiences on suicidal ideation. Thus, gender does not appear to explain the role of adverse experiences on suicidal ideation.

As robust as the main effect of number of adversities on outcomes appeared in the current analyses, there is evidence that the predictive utility of the number of adversities can be greatly improved by taking into account a specific cumulative approach, as well as the timing of exposure. In other words, identifying particular “high-impact” adversities and constructing indices of adversity using only these “high-impact” adversities strongly predicted suicidal ideation, and produced the highest estimate of variance explained of any of the models. This is consistent with a small, but growing body of research suggesting the importance of precision in defining relevant adversities for understanding psychosocial outcomes (Clark et al., 2010; Schilling et al., 2008). It also extends this nascent understanding of adversity, by highlighting the importance, not only of the nature of exposure to particular adversities, but also the timing of such exposure (Bruffaerts, 2010; English, Graham, et al., 2005; Flaherty et al., 2009).

Interestingly, just as taking into account timing improves the utility of an adversity-specific approach, taking into account specific adversities improves the utility of timing. Using cumulative adversities, the current analyses found a strong effect of adolescent adversities. As well, adolescent adversities interacted significantly with childhood adversities. The nature of the interaction (a stronger effect of childhood adversities in the presence of low levels of adolescent adversities, and a weaker effect of childhood adversities in the presence of higher levels of adolescent adversities) suggests a complex relationship between these two classes of adversities. It may be that there is a ceiling effect for exposure to adolescent adversities; whereas at lower levels of adolescent adversities, the effects of childhood adversity are more prominent. These results are broadly consistent with a stress inoculation interpretation of childhood adversities at very high levels of adversity (Seery et al., 2010). However, at moderate levels of adversity, the results are not inconsistent with a vulnerability-stress conceptualization (McLaughlin et al., 2010).

There was also evidence that a specific cumulative approach increased the predictive power of childhood adversities; these analyses produced a model for risk of suicidal ideation that included both significant prediction of adolescent adversities (specifically, physical abuse, psychological abuse, sexual abuse, and non-family violence), as well as childhood adversities (specifically physical abuse, neglect, family violence, and residential instability) that uniquely predicted current suicidal ideation. This more specific list is consistent with previous research which has identified particular factors as risky for youth outcomes generally. Child maltreatment, albeit in somewhat different forms (sexual abuse and psychological maltreatment in adolescence, neglect in early childhood, and physical abuse across the lifespan) emerged as a potent class of predictors of risk. Although usually ignored by child protective services, there is growing evidence of the noxious effects of maltreatment occurring in adolescence, including psychological abuse (Everson et al., 2008; Thompson et al., in press). These findings also echo earlier findings from the LONGSCAN studies suggesting the importance of neglect (Kotch et al., 2008) and family instability (English, Thompson, et al., 2005) that occur early in life, suggesting the importance of having adults predictably meet the needs of children early in life. .

Limitations

It is important to keep in mind several caveats and limitations when interpreting these findings. First is the issue of assessment of key variables. Suicidal ideation was defined using a single item (“During the last 12 months, did you ever seriously consider attempting suicide?”), albeit an item that has been widely validated, and forms the basis of national estimates of the prevalence of youth suicidal ideation (Brener et al., 2004). It is, however, a very conservative indicator of suicidal ideation, as it specifies “serious thoughts” rather than simply thoughts. In addition to this substantive concern, treating suicidal ideation as a dichotomous variable probably resulted in somewhat reduced power to detect effects, relative to models using a continuous outcome variable (Kleinbaum, Kupper, Muller, & Nizam, 2007).

It is also important to acknowledge that the assessment and definitions of adversities were relatively crude. Although our prospective collection of this information about adversities represents an important improvement over most of the prior studies that collected this information retrospectively and often many years later (as noted by Flaherty et al., 2009), there are still further improvements that could be made. The categories of experience assessed and defined as adversities here were not exhaustive. As well, for these analyses, variation in timing was defined as childhood versus adolescent. Future work should examine such adversities in a more precise way, with regard to timing of exposure to adversities. Additionally, this research, like most on adversities (e.g., Felitti et al., 1998; Flaherty et al., 2009) focuses on the number of different adversities, rather than the frequency of adversities. Further research with more detail on such frequencies would be a useful extension of the current findings.

As well, this research was intended to model the effects of adverse experiences on suicidal ideation, rather than to provide a comprehensive model of predictors of suicidal ideation. At its most precise, the model predicted roughly one fifth of the variance in suicidal ideation, suggesting that other factors not examined here were also important. In addition to adverse experiences, mental illness (especially depressive symptoms) is an important predictor of suicidal ideation (Fergusson et al., 2003; Thompson et al., 2005). As noted earlier, mental illness and substance use are likely to act as mediators of the link between adversities and suicidal ideation (Dube et al., 2001; Thompson et al., in press).; future research should examine these and other potential mediators such as future orientation (Thompson & Zuroff, 2010).

Finally, it is important to acknowledge that findings from the LONGSCAN sample may not extend to a general population sample. LONGSCAN is a high-risk sample (Runyan et al., 1998), and participants have a very high base rate of exposure to the adversities examined. This is both a strength and a weakness of the LONGSCAN sample; high base rate of exposure to such adversities, often rarer among general population samples, affords the power to test the effects of such adversities. However, this advantage in power means that similar findings may not obtain in general population samples. As well, the LONGSCAN sample analyzed here was the result of some attrition from the baseline sample. Finally, the LONGSCAN sample had a very high proportion of African American participants, and African American youth had lower rates of suicidal ideation than did white youth, consistent with prior research (Palmer, Rysiew, & Koob, 2003; Thompson et al., 2005).

Implications

Even with these limitations, the current findings have important implications for understanding the influence of adverse experiences on suicidal ideation in particular, and negative outcomes more generally. The power of adverse experiences to predict suicidal ideation was quite modest when approached in the way it has typically been examined. Greater precision in the assessment of the timing of adversities, and taking into account the influence of particular adversities substantially improved the ability to identify youth at risk of suicidal ideation. Future research examining the effects of adversity on a variety of outcomes would benefit from greater precision in examining the timing of adversities and also from a specific cumulative approach to understanding adversity. At the very least, future research should examine the possibility that effects of cumulative adversity are driven by particular adversities.

From a clinical and practical perspective, these findings highlight the degree to which both childhood and adolescent adversity, particularly around family dysfunction, but also community violence, increase the risk of suicidal ideation in at-risk youth. In assessing and intervening with suicidal youth, it will be important to assess the degree to which such adverse experiences play a role in initiating and maintaining the distress that leads to suicidal ideation, and may provide a key focal point for clinical intervention. In particular, psychological maltreatment and other forms of maltreatment are typically ignored in adolescence, but would be a useful area to asses and to target with interventions for suicidal youth; neglect and instability early in life are also apparently potent predictors of risk. As well, these findings highlight the importance of acknowledging the degree to which youth exposed to such experiences are at risk of experiencing suicidal ideation. Since both parents and teachers are not good at identifying children and youth experiencing suicidal ideation (Thompson et al., 2006), other approaches for targeting such individuals need to be utilized. Clearly, attempts to identify youth at risk for suicidal ideation can be improved by considering which specific adversities are experienced and when they are experienced.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants to the Consortium for Longitudinal Studies on Child Abuse and Neglect (LONGSCAN) from the Children's Bureau, Office on Child Abuse and Neglect, Administration for Children, Youth, and Families. It benefited from comments by Richard Calica and Stephen Budde.

Contributor Information

Richard Thompson, Juvenile Protective Association.

Alan J. Litrownik, San Diego State University

Patricia Isbell, University of North Carolina – Chapel Hill.

Mark D. Everson, University of North Carolina – Chapel Hill

Diana J. English, University of Washington

Howard Dubowitz, University of Maryland School of Medicine.

Laura J. Proctor, Judge Baker Children's Center, Harvard Medical School

Emalee G. Flaherty, Children's Memorial Hospital

REFERENCES

- Allen J, Le H. An additional measure of overall effect size for logistic regression models. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics. 2008;33:416–441. [Google Scholar]

- Anda R, Felitti V, Bremner JD, Walker JD, Whitfield D, Perry BD, Dube SR, Giles WH. The enduring effects of abuse and related adverse experiences in childhood: A convergence of evidence from neurobiology and epidemiology. European Archives of Psychiatry & Clinical Neuroscience. 2006;256:174–186. doi: 10.1007/s00406-005-0624-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnett D, Manly JT, Cicchetti D. Defining child maltreatment: The interface between policy and research. In: Cicchetti D, Toth SL, editors. Advances in Applied Developmental Psychology: Child Abuse, Child Development, and Social Policy. Ablex; Norwood, NJ: 1993. pp. 7–73. [Google Scholar]

- Bensley LS, Van Eenwyk J, Spieker SJ, Schoder J. Self-reported abuse history and adolescent problem behavior: I. Antisocial and suicidal behaviors. Journal of Adolescent Health. 1999;24:163–172. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(98)00111-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brener ND, Kann L, Kinchen S, et al. Methodology of the Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2004;53(RR-12) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodsky BS, Stanley B. Adverse childhood experiences and suicidal behavior. Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2008;31:223–235. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2008.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruffaerts R, Demyttenaere K, Borges G, Haro JM, Chiu WT, Hwang I, Karam EG, Nock MN. Childhood adversities as risk factors for onset and persistence of suicidal behavior. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2010;197:20–27. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.109.074716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark DB, Thatcher DL, Martin CS. Child abuse and other traumatic experiences, alcohol use disorders, and health problems in adolescence and young adulthood. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2010;35:499–510. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsp117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinwiddie S, Heath AC, Dunne MP, et al. Early sexual abuse and lifetime psychopathology: A co-twin-control study. Psychological Medicine. 2000;30:41–52. doi: 10.1017/s0033291799001373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dube SR, Anda RF, Felitti VJ, Chapman DP, Williamson DF, Giles WH. Childhood abuse, household dysfunction, and the risk of attempted suicide throughout the life span: Findings from the Adverse Childhood Experiences Study. JAMA. 2001;286:3089–3096. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.24.3089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards VJ, Holden GW, Felitti VJ, Anda RF. Relationship between multiple forms of childhood maltreatment and adult mental health in community respondents: Results from the Adverse Childhood Experiences Study. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2003;160:1453–1460. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.8.1453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- English DJ, Graham JC, Litrownik AJ, Everson M, Bangdiwala SI. Defining maltreatment chronicity: Are there differences in child outcomes? Child Abuse and Neglect. 2005a;29:575–595. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2004.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- English DJ, Thompson R, Graham JC, Briggs EC. Toward a definition of neglect in young children. Child Maltreatment. 2005;10:190–206. doi: 10.1177/1077559505275178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- English DJ, LONGSCAN Investigators Modified Maltreatment Classification System (MMCS) 1997 For more information visit the LONGSCAN website at: http://www.iprc.unc.edu/longscan/

- Everson MD, Smith J, Hussey JM, English D, Litrownik AJ, Dubowitz H, Thompson R, Runyan DK. Concordance between adolescent reports of childhood abuse and Child Protective Service determinations in an at-risk sample of young adolescents. Child Maltreatment. 2008;13:14–26. doi: 10.1177/1077559507307837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, Williamson DF, Spitz AM, Edwards V, Koss MP, Marks JS. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 1998;14:245–258. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(98)00017-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson DM, Beautrais AL, Horwood LJ. Vulnerability and resiliency to suicidal behaviours in young people. Psychological Medicine. 2003;33:61–73. doi: 10.1017/s0033291702006748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher HL, Jones PB, Fearon P, Craig TK, Dazzan P, Morgan K, Hutchinson G, Morgan C. The varying impact of type, timing, and frequency of exposure to childhood adversity on its association with adult psychotic disorder. Psychological Medicine. 2010;40:1967–1978. doi: 10.1017/S0033291710000231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flaherty EG, Thompson R, Litrownik AJ, Zolotor AJ, Dubowitz H, Runyan DK, English DJ, Everson MD. Adverse childhood exposures and reported child health at age 12. Academic Pediatrics. 2009;9:150–156. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2008.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins DJ, McCabe MP. Multiple forms of child abuse and neglect: Adult retrospective reports. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2001;6:547–578. [Google Scholar]

- Hillis SD, Anda RF, Dube SR, Felitti VJ, Marchbanks PA, Marks JS. The association between adverse childhood experiences and adolescent pregnancy, long-term psychosocial consequences, and fetal death. Pediatrics. 2004;113:320–327. doi: 10.1542/peds.113.2.320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter WM, Cox CE, Teagle S, Johnson RM, Mathew R, Knight ED, Leeb RT, Smith JB. Measures for Assessment of Functioning and Outcomes in Longitudinal Research on Child Abuse. Volume 2: Middle Childhood. 2003 Accessible at the LONGSCAN web site ( http://www.iprc.unc.edu/longscan/

- Kleinbaum DG, Kupper LL, Nizam, Muller KE, Nizam A. Applied Regression Analysis and Multivariable Methods. Duxbury Press: Pacific Grove. 2007 [Google Scholar]

- Knight ED, Smith JB, Martin LM, Lewis T, the LONGSCAN Investigators Measures for Assessment of Functioning and Outcomes in Longitudinal Research on Child Abuse Volume 3: Early Adolescence (Ages 12-14) 2008 Accessible at the LONGSCAN web site ( http://www.iprc.unc.edu/longscan/)

- Knight ED, Smith JB, Martin LM, the LONGSCAN Investigators Measures for Assessment of Functioning and Outcomes in Longitudinal Research on Child Abuse and Neglect Volume 4: Middle Adolescence (Age 16) 2009 Accessible at the LONGSCAN web site ( http://www.iprc.unc.edu/longscan/)

- Korkeila J, Vahtera J, Nabi H, Kivimaki M, Korkeila K, Sumanen M, Koskenvuo K, Koskenvuo M. Childhood adversities, adulthood life events and depression. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2010;127:130–138. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2010.04.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotch JB, Lewis T, Hussey JM, English D, Thompson R, Litrownik AJ, Runyan DK, Dubowitz H. Importance of early neglect for childhood aggression. Pediatrics. 2008;121:725–731. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-3622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert SF, Copeland, Linder N, Ialongo NS. Longitudinal associations between community violence exposure and suicidality. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2008;43:380–386. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lansford JE, Miller-Johnson S, Berlin LJ, Dodge KA, Bates JE, Pettit GS. Early physical abuse and later violent delinquency: A prospective longitudinal study. Child Maltreatment. 2007;12:233–245. doi: 10.1177/1077559507301841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis T, Kotch J, Thompson R, Litrownik AJ, English DJ, Proctor LJ, Runyan DK, Dubowitz H. Witnessed violence and youth behavior problems: A multi-informant study. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2010;80:443–450. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.2010.01047.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin KA, Conron KJ, Koenen KC, Gilman SE. Childhood adversity, adult stressful life events, and risk of past-year psychiatric disorder: A test of the stress sensitization hypothesis in a population-based sample of adults. Psychological Medicine. 2010;40:1647–1658. doi: 10.1017/S0033291709992121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nrugham L, Holen A, Sund AM. Associations between attempted suicide, violent life events, depressive symptoms, and resilience in adolescents and young adults. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2010;198:131–136. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e3181cc43a2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer C, Rysiew M, Koob JJ. Self-esteem, locus of control, and suicide risk: A comparison between clinically depressed White and African American females on an inpatient psychiatric unit. Journal of Ethnic and Cultural Diversity in Social Work. 2003;12:49–63. [Google Scholar]

- Pickles A, Aglan A, Collishaw S, Messer J, Rutter M, Maughan B. Predictors of sucidality across the life span: The Isle of Wight study. Psychological Medicine. 2010;40:1453–1466. doi: 10.1017/S0033291709991905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Runyan DK, Curtis P, Hunter WM, Black MM, Kotch JB, Bangdiwala S, et al. LONGSCAN: A consortium for longitudinal studies of maltreatment and the life course of children. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 1998;3:275–285. [Google Scholar]

- Sarason I, Johnson J, Siegel J. Assessing the impact of life changes: Development of the Life Experiences Survey. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1978;46:932–946. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.46.5.932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schilling E, Aseltine R, Gore S. The impact of cumulative childhood adversity on young adult mental health: Measures, models, and interpretations. Social Science and Medicine. 2008;66:1140–1151. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.11.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schumm JA, Stines LR, Hobfoll SE, Jackson AP. The double-barreled burden of child abuse and current stressful circumstances on adult women: The kindling effect of early traumatic experience. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2005;18:467–476. doi: 10.1002/jts.20054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seery MD, Holman EA, Silver RC. Whatever does not kill us: Cumulative lifetime adversity, vulnerability and resilience. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2010;99:1025–1041. doi: 10.1037/a0021344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senn TE, Carey MP. Child maltreatment and women's adult sexual risk behavior: Childhood sexual abuse as a unique risk factor. Child Maltreatment. 2010;15:324–335. doi: 10.1177/1077559510381112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein DJ, Chiu WT, Hwang I, Kessler RC, Sampson N, Alonso J, Borges G, Nock MK. Cross-national analysis of the associations between traumatic events and suicidal behavior: Findings from the WHO World Mental Health Surveys. PLoS One. 2010;5:e10574. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ten Have M, de Graaf R, von Dorsselaer S, Verdurmen J, van't Land H, Vollebergh W, Beekman A. Incidence and course of suicidal ideation and suicide attempts in the general population. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 2010;54:824–833. doi: 10.1177/070674370905401205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson R, Briggs E, English DJ, Dubowitz H, Lee L-C, Brody K, Everson MD, Hunter WM. Suicidal ideation among maltreated and at-risk 8-year-olds: Findings from the LONGSCAN studies. Child Maltreatment. 2005;10:26–36. doi: 10.1177/1077559504271271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson R, Litrownik AJ, Weisbart C, Kotch JB, English DJ, Everson MD. Adolescent outcomes associated with early maltreatment and exposure to violence: The role of early suicidal ideation. International Journal of Child and Adolescent Health. 2010;3:55–66. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson R, Proctor LJ, English DJ, Dubowitz H, Narasimhan S, Everson MD. Suicidal ideation in adolescence: Examining the role of recent adverse experiences. Journal of Adolescence. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2011.03.003. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson R, Proctor LJ, Weisbart C, Lewis TL, English DJ, Hussey JM, Runyan DK. Children's self-reports about violence exposure: An examination of The Things I Have Seen and Heard scale. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2007;77:454–466. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.77.3.454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson R, Zuroff DC. My future self and me: Depressive styles and future expectations. Personality and Individual Differences. 2010;48:190–195. [Google Scholar]

- Thornberry TP, Ireland TO, Smith CA. The importance of timing: the varying impact of childhood and adolescent maltreatment on multiple problem outcomes. Development and Psychopathology. 2001;13:957–979. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]