Abstract

Introduction

It has been suggested that vitamin D is effective to prevent mortality. However, there is no consistent conclusion that the effects of vitamin D supplementation on all-cause mortality are associated with duration of treatment. We conducted a meta-analysis regarding this issue in an effort to provide a more robust answer.

Methods

A comprehensive search in a number of databases, including MEDLINE, Embase and The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, was conducted for collecting randomized controlled trials (RCTs) on vitamin D supplementation preventing mortality. Two investigators independently screened the literature according to the inclusive and exclusive criteria and the relative data were extracted. Data analysis was performed by using Review Manager 5.0 software.

Results

Data from forty-two RCT s were included. Vitamin D therapy significantly decreased all-cause mortality with a duration of follow-up longer than 3 years with a RR (95% CI) of 0.94 (0.90–0.98). No benefit was seen in a shorter follow-up periods with a RR (95% CI) of 1.04 (0.97–1.12). Results remain robust after sensitivity analysis. The following subgroups of long-term follow-up had significantly fewer deaths: female only, participants with a mean age younger than 80, daily dose of 800 IU or less, participants with vitamin D insufficiency (baseline 25-hydroxyvitamin D level less than 50 nmol/L) and cholecalciferol therapy. In addition, the combination of vitamin D and calcium significantly reduced mortality and vitamin D alone also had a trend to decrease mortality in a longer time follow up.

Conclusions

The data suggest that supplementation of vitamin D is effective in preventing overall mortality in a long-term treatment, whereas it is not significantly effective in a treatment duration shorter than 3 years. Future studies are needed to identify the efficacy of vitamin D on specific mortality, such as cancer and cardiovascular disease mortality in a long-term treatment duration.

Introduction

Vitamin D plays a key role in human health, while the prevalence of vitamin D insufficiency is high, especially among the elderly [1]. It has recently been identified to be associated with skeletal diseases such as osteoporosis [2] and non-skeletal diseases including cancer [3-5], cardiovascular disease [6], and kidney disease [7,8]. Meta-analysis has suggested that low vitamin D baseline levels are associated with increased risks of mortality [9]. This issue is becoming to be paramount importance given the high prevalence of vitamin D deficiency worldwide [10].

It has been documented that vitamin D supplementation prevents fractures and falls [11,12]. In recent years, several studies on meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials with regard to supplementation of vitamin D on total mortality have been published, which found that vitamin D supplementation reduced total mortality when given together with calcium, but not with vitamin D alone [13-16], and. A Cochrane systematic review found that vitamin D significantly decreased mortality in those with vitamin D insufficiency [15]. However, long-term health effects of vitamin D supplementation still remains unclear.

To investigate whether the effects of vitamin D supplementation on all-cause mortality are associated with duration of treatment, we undertook a comprehensive systematic database search and meta-analysis to access the effects of vitamin D supplementation on all-cause mortality.

Materials and Methods

Search strategy

A literature search was conducted on a number of databases, including Medline, Embase and The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials for the period January 1960 to January 2013, to identify RCTs. Our core search terms were “randomized controlled trial”, “vitamin D”, “vitamin D2”, “vitamin D3”, “ergocalciferol”, “cholecalciferol”, “mortality”, “death”. We also searched for any additional studies in the reference lists of recent meta-analysis of vitamin D treatment for mortality. Our searches were limited to human trials, and no language or time restriction was applied.

Eligibility criteria

The preliminary search results were then examed on the basis of the following criteria.

Types of studies

Randomized controlled trials evaluating an intervention with vitamin D were identified as part of the review, while review articles, commentaries, letters, observational studies were excluded.

Interventions

The intervention group was restricted to vitamin D alone or in combination with calcium treatment; the control group was placebo, no treatment or calcium only therapy. Studies of patients receiving active vitamin D and intramuscular injection of vitamin D were excluded from the review.

Outcome

The number of deaths was reported separately for the vitamin D treatment group and the control group. For articles with a large sample size, if the number of deaths was not reported by treatment, we tried to contact the authors to obtain the missing data.

Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

Two statisticians independently extracted information from included trials using a standardized form., and then another statisticians verified them. The following information was subtracted from the study: first author, publishing year, sample size, duration, dwelling, intervention, serum 25 (OH) D levels at baseline, and main results (the number of participants who died). Quality assessment of included trials was conducted using the Cochrane Collaboration’s tool [17]. Methodological features most relevant to the control of bias were examined, including random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and personnel, blinding of outcome assessment, incomplete outcome data, selective reporting and other bias [17]. Quality assessment was performed by two independent researchers.

Data Synthesis and Analysis

Meta-analysis were undertaken using Review Manager (Version 5.0). The primary outcome was the number of participants who died during follow-up. The pre-planned analysis was vitamin D arm (with or without calcium) versus control arm (placebo, calcium, or no treatment) according to duration of treatment. Mantel-Haenszel method was used to calculate risk ratios (RRs) and their 95% confidence intervals (CI). The I2 statistic was used to assess the presence of heterogeneity, which ranges from 0% to 100% [18]. In case of lack of heterogeneity (I2 < 50%), fixed-effects model was used to assess the overall estimate, or else random-effects model was chosen. The Begg test [19] and Egger test [20] were used to evaluate the presence of publication bias regarding our primary end points (RR of mortality). A 2-tailed P value of less than .05 was considered as statistically significant.

Sensitivity analysis and subgroup analysis

A sensitivity analysis was conducted by excluding studies with high risk of bias. Subgroup analysis was conducted only on trials with the duration of treatment at least 3 years or longer. The effect of vitamin D was assessed according to gender (male or female), age group (< 80 years or ≥ 80 years), dose of oral vitamin D daily (≤800 IU or >800 IU), baseline level of 25- hydroxyvitamin D (< 50 nmol per liter or ≥ 50 nmol per liter), type of vitamin D (ergocalciferol or cholecalciferol) and calcium co-administration status (Vitamin D + calcium vs. Calcium, Vitamin D + calcium vs. Placebo, or Vitamin D vs. Placebo), and specific mortality (cancer mortality, cardiovascular mortality)

Results

Search Results

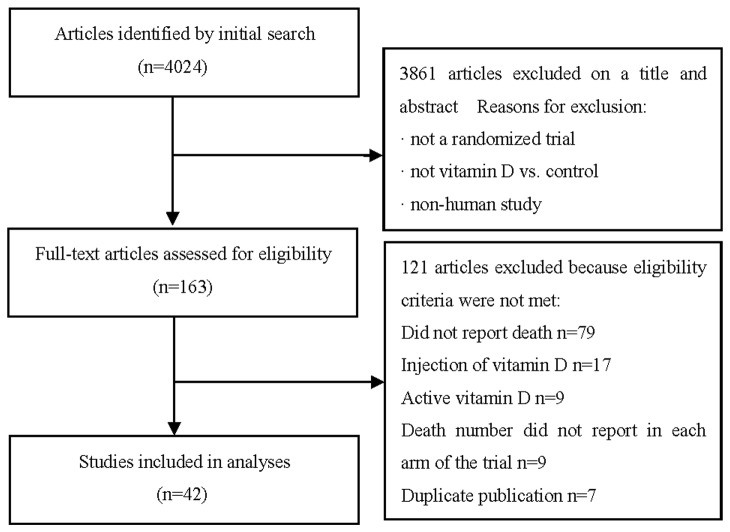

A total of 4,024 unique titles and abstracts were found from initial searches of the electronic database. With the inclusion/exclusion criteria, 3,861 of which were excluded by scrutinizing the titles and abstracts, and 121 articles were further excluded after full text review. A total of 42 RCTs that met inclusion criteria were included in the final analysis [21-62]. The details of study selection flow were explicitly described in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Study flow diagram.

Study Characteristics

The main characteristics of the included studies are shown in Table 1 (1). Publishing year: The RCTs were published from 1992 to 2012 (2). Treatment duration: 29 RCTs have treatment durations less than 3 years, and the remaining 13 RCTs have treatment durations of 3 years or longer (3). Number of patients: A total of 85,466 patients (42,561 in the vitamin D group and 42,905 in the control group) were included in these 42 RCTs (4). Age of patients: The number of participants in each trial ranged from 46 to 36,282 and mean age of participants ranged from 37 to 89 years, with most participants older than 60 years (5). Vitamin D type and dose: Vitamin D2 was used in 10 studies and vitamin D3 was used in the remaining 32 studies. Vitamin D2 or D3 was given as daily doses ranging from 300 to 3,333 IU. Calcium supplementation was used in 26 trials (6). Baseline vitamin D status: 37 trials (80%) reported the baseline vitamin D status of participants based on serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels. Participants in 15 trials had baseline 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels at or above cutoff for vitamin D adequacy (50 nmol/l or 20 ng/ml). Participants in the remaining 22 trials had baseline 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels in a range of vitamin D insufficiency (< 50 nmol/l or 20 ng/ml). The other 5 trials did not report the baseline vitamin D status of participants (7). Bias risk: 26 studies had a low risk of bias, and 16 had a high risk of bias (Table 2).

Table 1. Characteristics of the included studies.

| Study | Population characteristics | Treatment groups | Number of participants | Mean age (years) | Baseline Serum 25 (OH) D levels (mmol/l; mean) | Follow up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trials have a follow-up of 3 years or longer | ||||||

| Avenell 2012 | Community dwelling, with past low-energy racture | Vit D3 800 IU daily | 1343 | 77 | 38 | 5-8 years |

| Vit D3 800 IU daily + Ca1000 mg daily | 1306 | 77 | 38 | |||

| Ca 1000 mg daily | 1311 | 78 | 38 | |||

| Placebo | 1332 | 77 | 38 | |||

| Bolland 2011 | Community-based postmenopausal women | Vit D3 400 IU daily + Ca 1000 mg daily | 18176 | 62 | 46 | 7 years |

| Placebo | 18106 | 62 | 48 | |||

| Sanders 2010 | Ambulatory elderly women at risk for fracture | Vit D3 5000000 IU annually for 3-5 year | 1131 | 77 | 53 | 3 years |

| Placebo | 1125 | 77 | 45 | |||

| Salovaara 2010 | Women aged 65–71 years | Vit D3 800 IU daily + Ca 1000 mg daily | 1586 | 67 | 50 | 3 years |

| No treatment | 1609 | 67 | 49 | |||

| Zhu 2008 | Community-dwelling women aged 70–80 year | Vit D2 1000 IU daily + Ca 1200 mg daily | 39 | 75.4 | 70.2 | 5 years |

| Ca 1200 mg daily | 40 | 74.1 | 66.6 | |||

| Placebo | 41 | 74.8 | 67.3 | |||

| Lappe 2007 | Healthy postmenopausal white women | Vit D2 1100 IU + Ca 1400-1500 mg daily | 446 | 66.7 | 71.8 | 4 years |

| Ca 1400-1500 mg daily | 445 | 66.7 | 71.6 | |||

| Placebo | 288 | 66.7 | 72.1 | |||

| Lyons 2007 | Nursing home residents | Initially 100000 IU Vit D2 weekly, then 1000 IU Vit D2 daily + Ca 600 mg daily | 1725 | 84 | 80 | 3 years |

| Ca 600 mg daily | 1715 | 84 | 54 | |||

| Aloia 2005 | Healthy black postmenopausal women | Vit D3 800 IU daily + Ca 1200 to 1500 mg daily (after 2 years 2000 IU daily) | 104 | 59.9 | 48.25 | 3 years |

| Ca 1200 to 1500 mg daily | 104 | 61.2 | 43 | |||

| Larsen 2004 | Community-dwelling residents | Vit D3 400 IU daily + Ca 1000 mg daily | 4957 | 75 | 37 | 42 months |

| No treatment | 4648 | 75 | 33 | |||

| Trivedi 2003 | Community dwelling individuals | VitD3 100000 IU every 4 months | 1345 | 75 | 74 | 5 years |

| Placebo | 1341 | 75 | 53 | |||

| Komulainen 1999 | Nonosteoporotic, early postmenopausal | Vit D3 300 IU daily (no intake during June-August) for 4 years and 100 IU daily in the5th year + Ca 500 mg daily | 112 | 52.9 | NA | 5 yeas |

| Placebo | 115 | 52.6 | NA | |||

| D-Hughes 1997 | Healthy, ambulatory eldely older than 65 years | Vit D3 700 IU daily + Ca 500 mg daily | 187 | 71 | 71.75 | 3 years |

| Placebo | 202 | 72 | 61.25 | |||

| Lips 1996 | Elderly living in apartments or homes | VitD3 400 IU daily | 1291 | 80 | 27 | 3.5 years |

| Placebo | 1287 | 80 | 26 | |||

| Trials have a follow-up of less than 3 years | ||||||

| Alvarez 2012 | Patients with early chronic kidney disease | Vit D 50000 IU weekly for one year | 22 | 62.3 | 26.7 | 1 year |

| Placebo | 24 | 62.6 | 32.1 | |||

| Lehouck 2012 | chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | Vit D3 100000 IU every 4 months for one year | 91 | 68 | 50 | 1 year |

| Placebo | 91 | 68 | 50 | |||

| TiIDE trial 2012 | Patients with type 2 diabetes | Vit D3 1000 IU daily foe one year | 607 | 66.7 | NA | 6 months |

| Placebo | 614 | 66.6 | NA | |||

| Wasse 2012 | Patients with hemodialysis | Vit D3 200000 IU weekly for 3 weeks | 25 | 49 | 35.8 | 53 days |

| No treatment | 27 | 52 | 47.5 | |||

| Witham 2010 | Older patients with heart failure | Vit D2 100000 IU at 0 and 10 week | 53 | 78.8 | 20.5 | 20 weeks |

| Placebo | 52 | 80.6 | 23.7 | |||

| Lips 2010 | Elderly with vitamin D insufficient | Vit D3 8400 IU weekly for 3 weeks | 114 | 78.5 | 34.3 | 16 weeks |

| Placebo | 112 | 77.6 | 35.3 | |||

| Wejse 2009 | Patients with tuberculosis | Vit D3 100000 IU at 0, 5, 8 month | 187 | 37 | 77.5 | 1 year |

| Placebo | 180 | 38 | 79.1 | |||

| Chel 2008 | Nursing home residents | Vit D3 600 IU daily, or 4200 IU weekly or 180000 IU monthly for 4.5 month | 166 | 84.2 | 24.9 | 4.5 months |

| Placebo | 172 | 84.2 | 25.0 | |||

| Bjorkman 2008 | Aged chronically immobile patients | Vit D3 1200 IU daily | 73 | 83.9 | 24 | 6 months |

| Vit D3 400 IU daily | 77 | 84.2 | 21 | |||

| Placebo | 68 | 85.6 | 23 | |||

| Prince 2008 | Recruited from emergency department or nursing home | Vit D2 1000 IU daily + Ca 1000 daily | 151 | 77 | 45 | 1 year |

| Ca 1000 daily | 151 | 77 | 44 | |||

| Burleigh 2007 | Rehabilitation wards in an acute geriatric unit | Vit D3 800 IU daily + Ca 1200 daily | 101 | 82 | 22 | 1 year |

| Ca 1200 daily | 104 | 84 | 25 | |||

| Bolton-Smith 2007 | Healthy older women | Vit D3 400 IU daily + Ca1000 daily | 62 | 69.4 | 62.5 | 2 years |

| Placebo | 61 | 67.8 | 57 | |||

| Broe 2007 | Nursing home residents | Vit D2 200-800 IU daily | 99 | 89 | 48.75 | 5 months |

| Placebo | 25 | 86 | 50 | |||

| Law 2006 | Nursing home residents | Vit D2 100000 IU/3 months | 1762 | 85 | 59 | 10 months |

| Placebo | 1955 | 85 | 59 | |||

| Schleithoff 2006 | Patients with congestive heart failure | Vita D3 2000 IU daily + Ca 500 daily for 9 month | 61 | 57 | 36 | 15 months |

| Ca 500 daily | 62 | 54 | 38 | |||

| Brazier 2005 | Ambulatory women aged > 65 years with vitamin D insufficiency | Vit D3 800 IU daily + Ca 1000 daily | 95 | 74.2 | 18.25 | 1 year |

| Placebo | 97 | 75 | 17.5 | |||

| Flicker 2005 | Institutionalized with vitamin D level between 25 and 90 nmol/l | Vit D3 initially 100000 IUweekly, then 1000 IU daily + Ca 600 mg daily | 313 | 84 | 25-90 | 2 years |

| Ca 600 mg daily | 312 | 83 | 25-90 | |||

| Porthouse 2005 | Women aged 70 or over with risk factors for hip fracture | Vit D3 800 IU daily + Ca1000 daily | 1321 | 77 | NA | 25 months |

| Leaflet | 1993 | 76.7 | NA | |||

| Avenell 2004 | Participants had had an osteoporotic fracture within the last 10 years | Vit D3 800 IU daily + Ca1000 daily | 99 | 77 | NA | 1 year |

| No treatment | 35 | 75.6 | NA | |||

| Harwood 2004 | Elderly women after hip fracture | Vit D3 800 IU+ Ca 1000 mg daily | 29 | 83 | 29 | 1 year |

| No treatment | 35 | 81 | 30 | |||

| Meier 2004 | Healthy adults | VitD3 500 IU+ Ca 500 mg daily | 30 | 55.2 | 75.25 | 1.5 years |

| No treatment | 25 | 57.9 | 77 | |||

| Cooper 2003 | Women who were ≥ 1 y postmenopausal | Vit D2 100000 IU weekly + Ca 1000 daily | 93 | 56.5 | 81.6 | 2 years |

| Ca 1000 daily | 94 | 56.1 | 82.6 | |||

| Latham 2003 | Recruited from geriatric rehabilitation center | Vit D2 300,000 IU/im/once | 108 | 80 | 38 | 6 months |

| Placebo | 114 | 79 | 48 | |||

| Meyer 2002 | Nursing home residents | Vit D3 400 IU daily | 569 | 84 | 47 | 2 years |

| Placebo | 575 | 85 | 51 | |||

| Chapuy 2002 | Elderly ambulatory institutionalized women | Vit D3 800 IU daily + Ca 1200 mg daily | 393 | 85 | 22.5 | 2 years |

| Placebo | 190 | 85 | 22.7 | |||

| Krieg 1999 | Elderly women living in nursing homes | Vit D3 880 IU daily + Ca 1000 mg daily | 124 | 84 | 29.8 | 2 years |

| No treatment | 124 | 85 | 29.3 | |||

| Bæksgaard 1998 | Healthy postmenopausal women | Vit D3 560 IU daily + Ca 1000 mg daily | 80 | 62.9 | NA | 2 years |

| No treatment | 80 | 61.8 | NA | |||

| Ooms 1995 | Elderly women | VitD3 400 IU daily | 177 | 80.1 | 27 | 2 years |

| Placebo | 171 | 80.6 | 25 | |||

| Chapuy 1992 | Elderly living in apartments or nursing homes | Vit D3 800 IU daily + Ca 1200 mg daily | 1634 | 84 | 40 | 2 years |

| Placebo | 1636 | 84 | 32.5 | |||

Vit D, vitamin D; Ca, calcium

Table 2. Quality assessment of the included studies.

| Study | Random sequence Generation (selection bias) | Allocation Concealment (selection bias) | Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | Selective reporting Reporting (reporting bias) | Other bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trials have a follow-up of 3 years or longer | |||||||

| Avenell 2012 | L | L | L | L | L | L | L |

| Bolland 2011 | L | L | L | L | L | L | L |

| Sanders 2010 | L | L | L | L | L | L | L |

| Salovaara 2010 | L | L | H | H | L | L | L |

| Zhu 2008 | L | L | L | L | L | L | L |

| Lappe 2007 | L | L | L | L | H | L | L |

| Lyons 2007 | L | L | L | L | L | L | L |

| Aloia 2005 | L | L | L | L | L | L | L |

| Larsen 2004 | U | H | H | H | H | U | H |

| Trivedi 2003 | L | L | L | L | L | L | L |

| Komulainen 1999 | L | L | L | L | L | L | L |

| D-Hughes 1997 | L | L | L | L | L | L | L |

| Lips 1996 | L | L | L | L | L | L | L |

| Trials have a follow-up of less than 3 years | |||||||

| Alvarez 2012 | L | L | L | L | L | L | L |

| Lehouck 2012 | L | L | L | L | L | L | L |

| TiIDE trial 2012 | L | U | U | U | L | L | H |

| Wasse 2012 | L | L | L | L | L | L | L |

| Witham 2010 | L | L | L | L | L | L | L |

| Lips 2010 | L | L | L | L | L | L | L |

| Wejse 2009 | L | L | L | L | L | L | L |

| Chel 2008 | U | U | U | U | L | L | L |

| Bjorkman 2008 | L | L | L | L | L | L | L |

| Prince 2008 | L | L | L | L | L | L | L |

| Burleigh 2007 | L | L | L | L | L | L | L |

| Boton-Smith 2007 | L | L | L | L | L | L | L |

| Broe 2007 | L | L | L | L | L | L | L |

| Law 2006 | L | H | H | H | L | L | U |

| Schleithoff 2006 | L | L | L | L | L | L | L |

| Brazier 2005 | L | U | U | U | L | L | H |

| Flicker 2005 | L | L | L | L | L | L | L |

| Porthouse 2005 | L | L | H | H | L | U | H |

| Avenell 2004 | L | H | H | H | L | L | H |

| Harwood 2004 | L | L | H | H | L | L | H |

| Meier 2004 | U | U | H | H | L | L | U |

| Cooper 2003 | L | L | L | L | L | L | L |

| Latham 2003 | L | L | L | L | L | L | L |

| Meyer 2002 | H | H | L | L | L | L | H |

| Chapuy 2002 | U | U | U | U | L | L | H |

| Krieg 1999 | U | H | H | H | L | L | L |

| Bæksgaard 1998 | U | U | L | L | L | H | L |

| Ooms 1995 | L | L | L | L | L | L | L |

| Chapuy 1992 | U | U | U | U | L | L | L |

Primary Analysis

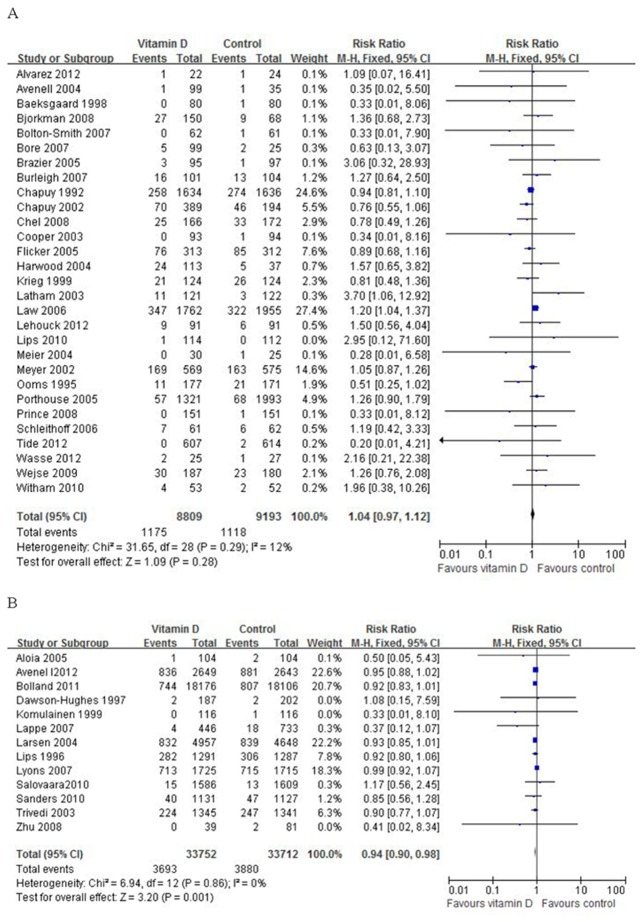

Analysis was performed independently for two categories with follow-up duration either less than 3 years, or 3 years or more. In the category of 29 trials with follow-up less than 3 years, a total of 1,175 (13.3%) participants randomized to the vitamin D group and 1,118 (12.2%) participants randomized to the placebo or no intervention group died. Analysis showed that vitamin D did not significantly decrease all-cause mortality. The risk ratio of mortality for patients treated with vitamin D compared with that of control was 1.04 (95% CI: 0.97–1.12), which was statistically insignificant (P = 0.28), with insignificant heterogeneity (I2 = 12%) (Figure 2A).

Figure 2. Primary analysis (fixed effect model): A, studies under 3 years; B, studies over 3 years.

In the second category of 13 trials with follow-up of 3 years or longer, a total of 3,693 (10.9%) participants randomized to the vitamin D group and 3,880 (11.5%) participants randomized to the placebo or no intervention group died. Data analysis showed that vitamin D significantly decreased all-cause mortality with a risk ratio of mortality 0.94 (95% CI: 0.90–0.98), which was statistically significant (P = 0.001), with insignificant heterogeneity (I2 = 0%) (Figure 2B).

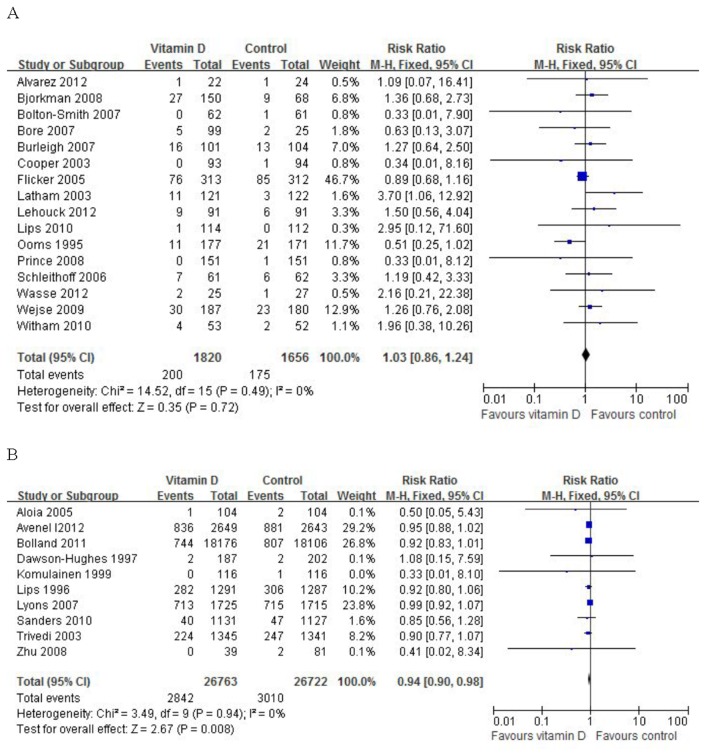

Sensitivity analysis

Sensitivity analysis was conducted by excluding the trials that had a high risk of bias, the results remain robust. For studies under 3 years (16 RCTs), the risk ratio of mortality for patients treated with vitamin D compared with control was 1.03 (95% CI: 0.86–1.24), which was not statistically significant (P = 0.72), with insignificant heterogeneity (I2 =0%) (Figure 3A). For studies over 3 years (10 RCTs), the risk ratio was 0.94 (95% CI: 0.90–0.98), which was statistically significant (P = 0.008), with insignificant heterogeneity (I2 =0%) (Figure 3B).

Figure 3. Sensitivity analysis (fixed effect model): A, studies under 3 years; B, studies over 3 years.

Subgroup analysis of long-term follow-up studies

In subgroup analysis (Table 3), significantly decreased mortality was seen in women (RR= 0.91; 95% CI: 0.83–1.00). Data on men were limited with only one related trial. Fewer death were found in patients younger than 80 years (RR= 0.93; 95% CI: 0.88–0.97), but not statistically significant in patients aged 80 years or older (RR= 0.97; 95% CI: 0.90–1.04). A dose of 800 IU or less (RR= 0.93; 95% CI: 0.89–0.98) was found to be more favorable than a dose greater than 800 IU (RR= 0.95; 95% CI: 0.89–1.03). Patients with baseline of 25-hydroxyvitamin D level less than 50 nmol/l treated with vitamin D resulted in significant reduction of mortality (RR= 0.93; 95% CI: 0.89–0.98), whereas no effect was seen in patients with baseline of 25-hydroxyvitamin D leve higher than 50 nmol/l (RR= 0.96; 95% CI: 0.89–1.03). Treatment with cholecalciferol (RR= 0.93; 95% CI: 0.89–0.97) was more favorable than with ergocalciferol (RR= 0.98; 95% CI: 0.90–1.06). Vitamin D combined with calcium was effective to reduce mortality when compared to placebo (RR= 0.94; 95% CI: 0.88–0.99), but not significantly effective when compared to calcium (risk ratio 0.97, 95% CI 0.91 to 1.03). The effect of vitamin D alone treatment was statistically insignificant compared to placebo (RR= 0.93; 95% CI: 0.86–1.00). Vitamin D treatment significantly reduced the cancer mortality (RR= 0.88; 95% CI: 0.79–0.98), but did not decrease cardiovascular mortality (RR= 0.91; 95% CI: 0.81–1.02).

Table 3. Subgroup benefits at the longer duration of Vitamin D, as compared with control group (Trial level data).

| Subgroup | No. of participants |

No. of death |

Risk ratio (95% CI) | P Value | I2, % | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vitamin D group | Control group | Vitamin D group | Control group | ||||

| Gender | |||||||

| Male only | 1019 | 1018 | 199 | 220 | 0.88 (0.73–1.07) | 0.19 | 0 |

| Female only | 22111 | 22401 | 831 | 919 | 0.91 (0.83–1.00) | 0.04 | 0 |

| Age | |||||||

| <80 yr | 30736 | 30710 | 2698 | 2859 | 0.93 (0.88–0.97) | 0.002 | 0 |

| ≥80 yr | 3016 | 3002 | 995 | 1021 | 0.97 (0.90–1.04) | 0.39 | 0 |

| Dose of oral vitamin D, IU | P=0.61 | ||||||

| ≤800 | 29066 | 28715 | 2712 | 2851 | 0.93 (0.89–0.98) | 0.003 | 0 |

| >800 | 4686 | 4997 | 981 | 1029 | 0.95 (0.89–1.03) | 0.20 | 19 |

| Baseline 25-hydroxyvitamin D* | |||||||

| <50 | 27177 | 26788 | 2695 | 2835 | 0.93 (0.89–0.98) | 0.003 | 0 |

| ≥50 | 6459 | 6808 | 998 | 1044 | 0.96 (0.89–1.03) | 0.23 | 0 |

| Type of vitamin D | |||||||

| Ergocalciferol | 2210 | 2529 | 717 | 735 | 0.98 (0.90–1.06) | 0.59 | 45 |

| Cholecalciferol | 31542 | 31183 | 2976 | 3145 | 0.93 (0.89–0.97) | 0.001 | 0 |

| Calcium coadministration status | |||||||

| Vitamin D + calcium vs. calcium | 3174 | 3170 | 1129 | 1164 | 0.97 (0.91–1.03) | 0.32 | 0 |

| Vitamin D + calcium vs. placebo | 26367 | 26054 | 2008 | 2098 | 0.94 (0.88–0.99) | 0.02 | 0 |

| Vitamin D vs. placebo | 5110 | 5087 | 967 | 1034 | 0.93 (0.86–1.00) | 0.06 | 0 |

| Specific mortality | |||||||

| Cancer mortality | 22170 | 22090 | 558 | 632 | 0.88 (0.79–0.98) | 0.03 | 0 |

| Cardiovascular mortality | 22170 | 22090 | 489 | 537 | 0.91 (0.81–1.02) | 0.11 | 0 |

Based on the reported mean baseline level, irrespective of type of vitamin D assay, in a sample of study participants

Publication bias

No evidence of publication bias was detected for the risk ratio of mortality in this study by either Begg or Egger’s test. For studies under 3 years, Begg’s test P= 0.837, Egger’s test P= 0.623; For studies over 3 years, Begg’s test P= 0.059, Egger’s test P= 0.055.

Discussion

We conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis to evaluate the best available research evidence regarding vitamin D supplementation on overall mortality. A total of 42 RCTs were included in the present study, quality assessment suggested that the overall study quality was fair and no significant publication bias was detected. Our results demonstrates that vitamin D supplementation longer than 3 years leads to a significant reduction on overall mortality. When trials with a high risk of bias excluded in the sensitive analysis, the results remain robust. The effect of vitamin D on mortality reduction was significant in several subgroups of individuals: female patients, participants with a mean age younger than 80, dose of 800 IU or less, participants with vitamin D insufficiency (baseline 25-hydroxyvitamin D level less than 50 nmol/L) and cholecalciferol therapy. In addition, compared with placebo, vitamin D in combination with calcium significantly reduced mortality.

Our findings confirmed those in an earlier Cochrane systematic review [15] on the effect of vitamin D treatment on overall mortality, which showed that participants with vitamin D insufficiency (25-hydroxyvitamin D level less than 20 ng/ml) decreased the overall mortality significantly, and indicated that cholecalciferol therapy was more favorable than ergocalciferol and that vitamin D as daily doses of 800 IU or less was more favorable than daily doses more than 800 IU. In contrast with two meta-analysis [13,16], which compared daily dose of 800 IU or greater with that less than 800 IU and suggested that daily dose of vitamin D did not differ in the effect on the outcome, our analysis indicated that the beneficial effect of vitamin D is clearly observed in the low daily dose. One explanation may be that several included trials [23,27,30] used intermittent and high dose of vitamin D, which has been suggested less likely to have a benefit, or to even have a negative effect among the elderly [23]. Consumption of intermittent and high dose of vitamin D leads to high concentrations of plasma 25-hydroxyvitamin D. Michaëlsson et al [63] concluded that both high and low concentrations of plasma 25-hydroxyvitamin D were associated with elevated risks of overall and cancer mortality.

A previous meta-analysis conducted by Autier et al [13] suggested that no relationship was found with duration of vitamin D supplement. In contrast, our results indicated that vitamin D supplementation significantly reduced the overall mortality when duration was longer than 3 years compared with that of control. However, no benefit was seen in those with durations less than 3 years. Additionally, two meta-analyses of RCTs with vitamin D treatment on falls also reported that patients benefit from vitamin D supplementation in a longer time duration [64,65].

Our results indicated that vitamin D was effective in reducing mortality among female patients. There was a lack of evidence to draw a conclusion of vitamin D’s influence on male patients with only one identified trial collected death data by subgroup of gender. We concluded that vitamin D may decrease mortality in patients younger than 80 years old, but not in patients aged 80 years or older. However, no statistically significant difference was found for risk ratio of overall mortality between the two age groups (P= 0.59). This results support an early meta-analysis of vitamin D treatment on falls, which indicated that participants with a mean age younger than 80 benefited from vitamin D supplementation [64].

Several previous meta-analyses suggested that vitamin D supplementation reduced all-cause mortality when given together with calcium, but did not support an effect of vitamin D alone treatment [14-16]. In contrast, our results suggested that vitamin D combined with calcium reduced all-cause mortality significantly when compared with placebo (RR= 0.94; 95% CI: 0.88–0.99), but the effect was insignificantly when compared with calcium therapy (RR= 0.97; 95% CI: 0.91–1.03). Vitamin D alone had a trend to decrease mortality (RR= 0.93; 95% CI: 0.86–1.00) when administrated in a long time. It may indicate that calcium therapy does not increase risk of death [66]. Whether vitamin D given together with calcium is more beneficial than calcium alone treatment needs more RCTs to be clarified.

There is not sufficient evidence to draw conclusions of the effect of vitamin D on specific mortality with only 3 trials collected mortality data in a rigorous fashion. Vitamin D may have a beneficial effect on cancer related mortality. But it needs more RCTs to better understand the effect of vitamin D on cancer. Meta-analyses of cohort studies have suggested that vitamin D intake was associated with reduced risk of colorectal cancer [67], breast cancer [68] but not prostate cancer [69]. Vitamin D had no significant effect on cardiovascular disease mortality. A growing number of literature suggest that low levels of vitamin D are associated with cardiovascular disease risk [70-74]. A limited number of interventional studies that investigated the effects of vitamin D supplementation on cardiovascular disease risk showed mixed results [75-78]. The effect of vitamin D on cardiovascular diseases remains to be identified.

The mechanism of vitamin D benefit on overall mortality is not clear. Both forms of vitamin D (D2 and D3) are converted to 25-hydroxyvitamin [25(OH)D] in the liver, and then hydroxylated to 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D in the kidney [79]. 1,25(OH)2D is the only biologically active form of vitamin D, which increases calcium absorption and bone formation to maintain bone health, regulate blood pressure and insulin production, prevent heart disease, regulate immune function to prevent diabetes and autoimmune disease, regulate cell growth to prevent cancer [80,81].

Vitamin D insufficiency (< 50 nmol/L) has now been linked to a broad spectrum of human diseases from cancer to cardiovascular to autoimmune conditions [82]. Though vitamin D can acquire through cutaneous synthesis after sunlight exposure and nutrition [83], it is often not sufficient to reach the required levels of vitamin D, especially in patients with osteoporosis and fracture risk [84]. In that case, supplementation of vitamin D is required, in order to prevent vitamin D insufficiency and associated adverse outcomes.

Similar to other meta-analyses, our review has several limitations. First, though extensive searches were made, there were no data of Hispanic or Orientals. Second, most of the participants in the present study were older women, the effects of vitamin D on mortality in younger, healthy persons and in males are still inconclusive. Third, the overall RR (95% CI) effect was modest and could be the result of chance alone. Fourth, there were only 13 trials that have durations of follow up longer than 3 years.

In conclusion, our results implicated that long-term supplementation of vitamin D may have a beneficial effect on overall mortality, especially in patients with vitamin D insufficiency and younger than 80 years. Vitamin D in a dose of 800 IU daily or less was found to be more favorable than a dose greater than 800 IU and treatment with cholecalciferol was more favorable than ergocalciferol. Future studies are needed to test the efficacy of vitamin D on specific mortality, such as cancer and cardiovascular disease mortality in a long-term treatment duration.

Supporting Information

PRISMA checklist.

(DOC)

Funding Statement

This study was funded by the grants from National Natural Science Foundation of China (81102450). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Wahl DA, Cooper C, Ebeling PR, Eggersdorfer M, Hilger J et al. (2012) A global representation of vitamin D status in healthy populations. Arch Osteoporos 7: 155–172. doi: 10.1007/s11657-012-0093-0. PubMed: 23225293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Rovner AJ, Miller RS (2008) Vitamin D deficiency and insufficiency in children with osteopenia or osteoporosis. Pediatrics 122: 907-908. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-1743. PubMed: 18829822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ma Y, Zhang P, Wang F, Yang J, Liu Z, et aal (2011) Association between vitamin D and risk of colorectal cancer: a systematic review of prospective studies. J Clin Oncol 29: 3775–3782. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.35.7566. PubMed: 21876081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Abbas S, Chang-Claude J, Linseisen J (2009) Plasma 25-hydroxyvitamin D and premenopausal breast cancer risk in a German case-control study. Int J Cancer 124: 250–255. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23904. PubMed: 18839430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kilkkinen A, Knekt P, Heliövaara M, Rissanen H, Marniemi J et al. (2008) Vitamin D status and the risk of lung cancer: a cohort study in Finland. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 17: 3274–3278. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0199. PubMed: 18990771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Artaza JN, Mehrotra R, Norris KC (2009) Vitamin D and the cardiovascular system. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 4: 1515-1522. doi: 10.2215/CJN.02260409. PubMed: 19696220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ravani P, Malberti F, Tripepi G, Pecchini P, Cutrupi S et al. (2009) Vitamin D levels and patient outcome in chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int 75: 88–95. doi: 10.1038/ki.2008.501. PubMed: 18843258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mathieu C, Gysemans C, Giulietti A, Bouillon R (2005) Vitamin D and diabetes. Diabetologia 48: 1247-1257. doi: 10.1007/s00125-005-1802-7. PubMed: 15971062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Melamed ML, Michos ED, Post W, Astor B (2008) 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels and the risk of mortality in the general population. Arch Intern Med 168: 1629–1630. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.15.1629. PubMed: 18695076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Mithal A, Wahl DA, Bonjour JP, Burckhardt P, Dawson-Hughes B et al. (2009) Global vitamin D status and determinants of hypovitaminosis D. Osteoporos Int 20: 1807–1820. doi: 10.1007/s00198-009-0954-6. PubMed: 19543765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bischoff-Ferrari HA, Dawson-Hughes B, Staehelin HB, Orav JE, Stuck AE et al. (2009) Fall prevention with supplemental and active forms of vitamin D: a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ 339: b3692. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b3692. PubMed: 19797342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bischoff-Ferrari HA, Willett WC, Orav EJ, Lips P, Meunier PJ et al. (2012) A pooled analysis of vitamin D dose requirements for fracture prevention. N Engl J Med 367: 40-49. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1109617. PubMed: 22762317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Autier P, Gandini S (2007) Vitamin D supplementation and total mortality: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Arch Intern Med 167: 1730–1737. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.16.1730. PubMed: 17846391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Chung M, Balk EM, Brendel M, Ip S, Lau J et al. (2009) Vitamin D and calcium: a systematic review of health outcomes. Evid Rep Technol Assess (Full Rep) 183: 1–420. PubMed: 20629479. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bjelakovic G, Gluud LL, Nikolova D, Whitfield K, Wetterslev J et al. (2011) Vitamin D supplementation for prevention of mortality in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 7: CD007470:CD007470 PubMed: 21735411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Rejnmark L, Avenell A, Masud T, Anderson F, Meyer HE et al. (2012) Vitamin D with calcium reduces mortality: patient level pooled analysis of 70,528 patients from eight major vitamin D trials. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 97: 2670-2681. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-3328. PubMed: 22605432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Higgins JP, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, Jüni P, Moher D et al. (2011) The Cochrane Collaboration's tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 343: d5928. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d5928. PubMed: 22008217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Higgins JPT, Green S, Cochrane Collaboration (2008) Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Chichester, England; Hoboken, NJ:Wiley-Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Begg CB, Mazumdar M (1994) Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics 50(4): 1088–1101. doi: 10.2307/2533446. PubMed: 7786990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Egger M, Davey SG, Schneider M, Minder C (1997) Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ 315: 629–634. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629. PubMed: 9310563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Avenell A, MacLennan GS, Jenkinson DJ, McPherson GC, McDonald AM et al. (2012) Long-term follow-up for mortality and cancer in a randomized placebo-controlled trial of vitamin D(3) and/or calcium (RECORD trial). J Clin Endocrinol Metab 97: 614-622. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-1309. PubMed: 22112804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bolland MJ, Grey A, Gamble GD, Reid IR (2011) Calcium and vitamin D supplements and health outcomes: a reanalysis of the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) limited-access data set. Am J Clin Nutr 94: 1144-1149. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.111.015032. PubMed: 21880848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sanders KM, Stuart AL, Williamson EJ, Simpson JA, Kotowicz MA et al. (2010) Annual high-dose oral vitamin D and falls and fractures in older women: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 303: 1815-1822. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.594. PubMed: 20460620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Salovaara K, Tuppurainen M, Kärkkäinen M, Rikkonen T, Sandini L et al. (2010) Effect of vitamin D(3) and calcium on fracture risk in 65- to 71-year-old women: a population-based 3-year randomized, controlled trial--the OSTPRE-FPS. J Bone Miner Res 25: 1487-1495. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.48. PubMed: 20200964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Zhu K, Devine A, Dick IM, Wilson SG, Prince RL (2008) Effects of calcium and vitamin D supplementation on hip bone mineral density and calcium-related analytes in elderly ambulatory Australian women: a five-year randomized controlled trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 93: 743–749. PubMed: 18089701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lappe JM, Travers-Gustafson D, Davies KM, Recker RR, Heaney RP (2007) Vitamin D and calcium supplementation reduces cancer risk: results of a randomized trial. Am J Clin Nutr 85: 1586–1591. PubMed: 17556697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lyons RA, Johansen A, Brophy S, Newcombe RG, Phillips CJ et al. (2007) Preventing fractures among older people living in institutional care: a pragmatic randomised double blind placebo controlled trial of vitamin D supplementation. Osteoporos Int 18: 811–818. doi: 10.1007/s00198-006-0309-5. PubMed: 17473911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Aloia JF, Talwar SA, Pollack S, Yeh J (2005) A randomized controlled trial of vitamin D3 supplementation in African American women. Arch Intern Med 165: 1618–1623. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.14.1618. PubMed: 16043680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Larsen ER, Mosekilde L, Foldspang A (2004) Vitamin D and calcium supplementation prevents osteoporotic fractures in elderly community dwelling residents: a pragmatic population-based 3-year intervention study. J Bone Miner Res 19: 370–378. PubMed: 15040824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Trivedi DP, Doll R, Khaw KT (2003) Effect of four monthly oral vitamin D3 (cholecalciferol) supplementation on fractures and mortality in men and women living in the community: randomised double blind controlled trial. BMJ 326: 469. doi: 10.1136/bmj.326.7387.469. PubMed: 12609940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Komulainen M, Kröger H, Tuppurainen MT, Heikkinen AM, Alhava E et al. (1999) Prevention of femoral and lumbar bone loss with hormone replacement therapy and vitamin D3 in early postmenopausal women: a population-based 5-year randomized trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 84: 546–552. doi: 10.1210/jc.84.2.546. PubMed: 10022414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Dawson-Hughes B, Harris SS, Krall EA, Dallal GE (1997) Effect of calcium and vitamin D supplementation on bone density in men and women 65 years of age or older. N Engl J Med 337: 670–676. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199709043371003. PubMed: 9278463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lips P, Graafmans WC, Ooms ME, Bezemer PD, Bouter LM (1996) Vitamin D supplementation and fracture incidence in elderly persons. A randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Ann Intern Med 124: 400–406. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-124-4-199602150-00003. PubMed: 8554248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Alvarez JA, Law J, Coakley KE, Zughaier SM, Hao L et al. (2012) High-dose cholecalciferol reduces parathyroid hormone in patients with early chronic kidney disease: a pilot, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Clin Nutr 96: 672-679. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.112.040642. PubMed: 22854402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Lehouck A, Mathieu C, Carremans C, Baeke F, Verhaegen J et al. (2012) High doses of vitamin D to reduce exacerbations in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Ann Intern Med 156: 105-114. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-156-2-201201170-00004. PubMed: 22250141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Punthakee Z, Bosch J, Dagenais G, Diaz R, Holman R et al. (2012) Design, history and results of the Thiazolidinedione Intervention with vitamin D Evaluation (TIDE) randomised controlled trial. Diabetologia 55: 36-45. doi: 10.1007/s00125-011-2357-4. PubMed: 22038523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Wasse H, Huang R, Long Q, Singapuri S, Raggi P et al. (2012) Efficacy and safety of a short course of very-high-dose cholecalciferol in hemodialysis. Am J Clin Nutr 95: 522-528. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.111.025502. PubMed: 22237061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Witham MD, Crighton LJ, Gillespie ND, Struthers AD, McMurdo ME (2010) The effects of vitamin D supplementation on physical function and quality of life in older patients with heart failure a randomized controlled trial. Circ Heart Fail 3: 195-201. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.109.907899. PubMed: 20103775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Lips P, Binkley N, Pfeifer M, Recker R, Samanta S et al. (2010) Once-weekly dose of 8400 IU vitamin D(3) compared with placebo: effects on neuromuscular function and tolerability in older adults with vitamin D insufficiency. Am J Clin Nutr 91: 985–991. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2009.28113. PubMed: 20130093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Wejse C, Gomes VF, Rabna P, Gustafson P, Aaby P et al. (2009) Vitamin D as supplementary treatment for tuberculosis: a double-blind, randomized, placebocontrolled trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 179: 843–850. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200804-567OC. PubMed: 19179490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Chel V, Wijnhoven HA, Smit JH, Ooms M, Lips P (2008) Efficacy of different doses and time intervals of oral vitamin D supplementation with or without calcium in elderly nursing home residents. Osteoporos Int 19: 663–671. doi: 10.1007/s00198-007-0465-2. PubMed: 17874029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Björkman M, Sorva A, Risteli J, Tilvis R (2008) Vitamin D supplementation has minor effects on parathyroid hormone and bone turnover markers in vitamin D-deficient bedridden older patients. Age Ageing 37: 25–31. PubMed: 17965037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Prince RL, Austin N, Devine A, Dick IM, Bruce D et al. (2008) Effects of ergocalciferol added to calcium on the risk of falls in elderly high-risk women. Arch Intern Med 168: 103–108. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2007.31. PubMed: 18195202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Burleigh E, McColl J, Potter J (2007) Does vitamin D stop inpatients falling? A randomised controlled trial. Age Ageing 36: 507–513. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afm087. PubMed: 17656420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Bolton-Smith C, McMurdo ME, Paterson CR, Mole PA, Harvey JM et al. (2007) Two-year randomized controlled trial of vitamin K1 (phylloquinone) and vitamin D3 plus calcium on the bone health of older women. J Bone Miner Res 22: 509–519. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.070116. PubMed: 17243866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Broe KE, Chen TC, Weinberg J, Bischoff-Ferrari HA, Holick MF et al. (2007) A higher dose of vitamin d reduces the risk of falls in nursing home residents: a randomized, multiple-dose study. J Am Geriatr Soc 55: 234–239. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01048.x. PubMed: 17302660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Law M, Withers H, Morris J, Anderson F (2006) Vitamin D supplementation and the prevention of fractures and falls: results of a randomised trial in elderly people in residential accommodation. Age Ageing 35: 482–486. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afj080. PubMed: 16641143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Schleithoff SS, Zittermann A, Tenderich G, Berthold HK, Stehle P et al. (2006) Vitamin D supplementation improves cytokine profiles in patients with congestive heart failure: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Clin Nutr 83: 754–759. PubMed: 16600924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Brazier M, Grados F, Kamel S, Mathieu M, Morel A et al. (2005) Clinical and laboratory safety of one year’s use of a combination calcium + vitamin D tablet in ambulatory elderly women with vitamin D insufficiency: results of a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled study. Clin Ther 27: 1885–1893. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2005.12.010. PubMed: 16507374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Flicker L, MacInnis RJ, Stein MS, Scherer SC, Mead KE et al. (2005) Should older people in residential care receive vitamin D to prevent falls? Results of a randomized trial. J Am Geriatr Soc 53: 1881–1888. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.00468.x. PubMed: 16274368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Porthouse J, Cockayne S, King C, Saxon L, Steele E et al. (2005) Randomised controlled trial of calcium and supplementation with cholecalciferol (vitamin D3) for prevention of fractures in primary care. BMJ 330: 1003. doi: 10.1136/bmj.330.7498.1003. PubMed: 15860827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Avenell A, Grant AM, McGee M, McPherson G, Campbell MK et al. (2004) The effects of an open design on trial participant recruitment, compliance and retention--a randomized controlled trial comparison with a blinded, placebo-controlled design. Clin Trials 1: 490–498. doi: 10.1191/1740774504cn053oa. PubMed: 16279289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Harwood RH, Sahota O, Gaynor K, Masud T, Hosking DJ et al. (2004) A randomised, controlled comparison of different calcium and vitamin D supplementation regimens in elderly women after hip fracture: The Nottingham Neck of Femur (NONOF) Study. Age Ageing 33: 45–51. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afh002. PubMed: 14695863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Meier C, Woitge HW, Witte K, Lemmer B, Seibel MJ (2004) Supplementation with oral vitamin D3 and calcium during winter prevents seasonal bone loss: a randomized controlled open-label prospective trial. J Bone Miner Res 19: 1221–1230. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.040511. PubMed: 15231008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Cooper L, Clifton-Bligh PB, Nery ML, Figtree G, Twigg S et al. (2003) Vitamin D supplementation and bone mineral density in early postmenopausal women. Am J Clin Nutr 77: 1324–1329. PubMed: 12716689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Latham NK, Anderson CS, Lee A, Bennett DA, Moseley A et al. (2003) A randomized, controlled trial of quadriceps resistance exercise and vitamin D in frail older people: the Frailty Interventions Trial in Elderly Subjects (FITNESS). J Am Geriatr Soc 51: 291–299. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51101.x. PubMed: 12588571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Meyer HE, Smedshaug GB, Kvaavik E, Falch JA, Tverdal A et al. (2002) Can vitamin D supplementation reduce the risk of fracture in the elderly? A randomized controlled trial. J Bone Miner Res 17: 709–715. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2002.17.4.709. PubMed: 11918228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Chapuy MC, Pamphile R, Paris E, Kempf C, Schlichting M et al. (2002) Combined calcium and vitamin D3 supplementation in elderly women: confirmation of reversal of secondary hyperparathyroidism and hip fracture risk: the Decalyos II study. Osteoporos Int 13: 257–264. doi: 10.1007/s001980200023. PubMed: 11991447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Krieg MA, Jacquet AF, Bremgartner M, Cuttelod S, Thiébaud D et al. (1999) Effect of supplementation with vitamin D3 and calcium on quantitative ultrasound of bone in elderly institutionalized women: a longitudinal study. Osteoporos Int 9: 483–488. doi: 10.1007/s001980050174. PubMed: 10624454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Baeksgaard L, Andersen KP, Hyldstrup L (1998) Calcium and vitamin D supplementation increases spinal BMD in healthy, postmenopausal women. Osteoporos Int 8: 255–260. doi: 10.1007/s001980050062. PubMed: 9797910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Ooms ME, Roos JC, Bezemer PD, van der Vijgh WJ, Bouter LM et al. (1995) Prevention of bone loss by vitamin D supplementation in elderly women: a randomized doubleblind trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 80: 1052–1058. doi: 10.1210/jc.80.4.1052. PubMed: 7714065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Chapuy MC, Arlot ME, Duboeuf F, Brun J, Crouzet B et al. (1992) Vitamin D3 and calcium to prevent hip fractures in the elderly women. N Engl J Med 327: 1637–1642. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199212033272305. PubMed: 1331788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Michaëlsson K, Baron JA, Snellman G, Gedeborg R, Byberg L et al. (2010) Plasma vitamin D and mortality in older men: a community-based prospective cohort study. Am J Clin Nutr 92: 841-848. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2010.29749. PubMed: 20720256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Kalyani RR, Stein B, Valiyil R, Manno R, Maynard JW et al. (2010) Vitamin D treatment for the prevention of falls in older adults: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Geriatr Soc 58: 1299-1310. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.02949.x. PubMed: 20579169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Bischoff-Ferrari HA, Dawson-Hughes B, Staehelin HB, Orav JE, Stuck AE et al. (2009) Fall prevention with supplemental and active forms of vitamin D: a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ 339: b3692. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b3692. PubMed: 19797342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Uusi-Rasi K, Kärkkäinen MU, Lamberg-Allardt CJ (2013) Calcium intake in health maintenance - a systematic review. Food. Nutr Res 57. doi: 10.3402/fnr.v57i0.21082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Touvier M, Chan DS, Lau R, Aune D, Vieira R et al. (2011) Meta-analyses of vitamin D intake, 25-hydroxyvitamin D status, vitamin D receptor polymorphisms, and colorectal cancer risk. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 20: 1003-1016. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-10-1141. PubMed: 21378269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Chen P, Hu P, Xie D, Qin Y, Wang F et al. (2010) Meta-analysis of vitamin D, calcium and the prevention of breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 121: 469-477. doi: 10.1007/s10549-009-0593-9. PubMed: 19851861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Gilbert R, Martin RM, Beynon R, Harris R, Savovic J et al. (2011) Associations of circulating and dietary vitamin D with prostate cancer risk: a systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis. Cancer Causes Control 22: 319-340. doi: 10.1007/s10552-010-9706-3. PubMed: 21203822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Lavie CJ, Lee JH, Milani RV (2011) Vitamin D and cardiovascular disease will it live up to its hype? J Am Coll Cardiol 58: 1547–1556. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.07.008. PubMed: 21958881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Anderson JL, May HT, Horne BD, Bair TL, Hall NL et al. (2010) Relation of vitamin D deficiency to cardiovascular risk factors, disease status, and incident events in a general healthcare population. Am J Cardiol 106: 963–968. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2010.05.027. PubMed: 20854958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Lee JH, O’Keefe JH, Bell D, Hensrud DD, Holick MF (2008) Vitamin D deficiency an important, common, and easily treatable cardiovascular risk factor? J Am Coll Cardiol 52: 1949–1956. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.08.050. PubMed: 19055985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Giovannucci E, Liu Y, Hollis BW, Rimm EB (2008) 25-hydroxyvitamin D and risk of myocardial infarction in men: a prospective study. Arch Intern Med 168: 1174–1180. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.11.1174. PubMed: 18541825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Wang TJ, Pencina MJ, Booth SL, Jacques PF, Ingelsson E et al. (2008) Vitamin D deficiency and risk of cardiovascular disease. Circulation 117: 503–511. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.706127. PubMed: 18180395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Hsia J, Heiss G, Ren H, Allison M, Dolan NC, et al. (2007) Calcium/vitamin D supplementation and cardiovascular events. Circulation 115: 846-854 (Erratum in: Circulation. 2007 May 15: 115(19): e466) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Sugden JA, Davies JI, Witham MD, Morris AD, Struthers AD (2008) Vitamin D improves endothelial function in patients with Type 2 diabetes mellitus and low vitamin D levels. Diabet Med 25: 320–325. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2007.02360.x. PubMed: 18279409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Margolis KL, Ray RM, Van Horn L, Manson JE, Allison MA et al. (2008) Effect of calcium and vitamin D supplementation on blood pressure: the Women’s Health Initiative Randomized Trial. Hypertension 52: 847–855. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.108.114991. PubMed: 18824662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Gepner AD, Ramamurthy R, Krueger DC, Korcarz CE, Binkley N et al. (2012) A prospective randomized controlled trial of the effects of vitamin D supplementation on cardiovascular disease risk. PLOS ONE 7: e36617. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036617. PubMed: 22586483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Thacher TD, Clarke BL (2011) Vitamin D insufficiency. Mayo Clin Proc 86: 50–60. doi: 10.4065/mcp.2011.0356. PubMed: 21193656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Bouillon R, Eelen G, Verlinden L, Mathieu C, Carmeliet G et al. (2006) Vitamin D and cancer. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 102: 156-162. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2006.09.014. PubMed: 17113979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Holick MF (2004) Vitamin D: importance in the prevention of cancers, type 1 diabetes, heart disease, and osteoporosis. Am J Clin Nutr 79: 362-371. PubMed: 14985208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. van den Bergh JP, Bours SP, van Geel TA, Geusens PP (2011) Optimal use of vitamin D when treating osteoporosis. Curr Osteoporos Rep 9: 36-42. doi: 10.1007/s11914-010-0041-0. PubMed: 21113692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Mithal A, Wahl DA, Bonjour JP, Burckhardt P, Dawson-Hughes B et al. (2009) Global vitamin D status and determinants of hypovitaminosis D. Osteoporos Int 20: 1807-1820. doi: 10.1007/s00198-009-0954-6. PubMed: 19543765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Cashman KD (2012) The role of vitamers and dietary-based metabolites of vitamin D in prevention of vitamin D deficiency. Food. Nutr Res 56:Epub. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

PRISMA checklist.

(DOC)