Abstract

Mutations in transforming growth factor beta (TGFβ) receptor type II (TGFBR2) cause Loeys–Dietz syndrome, characterized by craniofacial and cardiovascular abnormalities. Mice with a deletion of Tgfbr2 in cranial neural crest cells (Tgfbr2fl/fl;Wnt1-Cre mice) develop cleft palate as the result of abnormal TGFβ signaling activation. However, little is known about metabolic processes downstream of TGFβ signaling during palatogenesis. Here, we show that Tgfbr2 mutant palatal mesenchymal cells spontaneously accumulate lipid droplets, resulting from reduced lipolysis activity. Tgfbr2 mutant palatal mesenchymal cells failed to respond to the cell proliferation stimulator sonic hedgehog, derived from the palatal epithelium. Treatment with p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) inhibitor or telmisartan, a modulator of p38 MAPK activation and lipid metabolism, blocked abnormal TGFβ-mediated p38 MAPK activation, restoring lipid metabolism and cell proliferation activity both in vitro and in vivo. Our results highlight the influence of alternative TGFβ signaling on lipid metabolic activities, as well as how lipid metabolic defects can affect cell proliferation and adversely impact palatogenesis. This discovery has broader implications for the understanding of metabolic defects and potential prevention of congenital birth defects.

INTRODUCTION

Orofacial clefts, including cleft palate and cleft lip, are among the most prevalent human birth defects (1). The etiology of cleft palate is influenced by complex genetic and environmental risk factors as well as gene–environment interactions. Metabolic abnormalities, such as maternal diabetes and obesity, increase the risk of cleft palate and other craniofacial deformities (2–5).

The critical steps in palatogenesis include the growth, alignment and fusion of the palatal shelves, which are completed by embryonic day 16.5 (E16.5) in mice and by the end of the first trimester of gestation in humans (6,7). The palatal shelves are composed of diverse cell types derived from the cranial neural crest (CNC), mesoderm, and pharyngeal ectoderm (8). CNC cells contribute to the vast majority of the palatal mesenchyme and play crucial roles in palatogenesis (9). The fact that maternal and fetal metabolic abnormalities convey an increased risk of orofacial clefting suggests that CNC-derived cells are sensitive to alterations in cellular homeostasis during early embryogenesis. However, the influence of the lipid metabolic pathway on palate development and cleft palate remains unknown.

Transforming growth factor beta (TGFβ) signaling has crucial functions in regulating craniofacial development (8). For example, mutations in the TGFβ receptors (TGFBR1 or TGFBR2) cause Loeys–Dietz syndrome (previously called Marfan syndrome type II), which presents with cleft palate and other craniofacial and cardiovascular abnormalities (10–12). Similarly, loss of Tgfbr1 (a.k.a. Alk5) or Tgfbr2 in murine CNC cells leads to craniofacial malformations such as cleft palate (8). We have demonstrated that these defects result from the inappropriate activation of a noncanonical TGFβ signaling pathway through the TβRI/TβRIII receptor complex in the absence of TβRII (13).

In this study, we investigated how alternative TGFβ signaling in Tgfbr2fl/fl;Wnt1-Cre mouse embryos adversely affects cellular metabolism during palatogenesis. We found that lipid metabolic aberrations are associated with a cell proliferation defect in Tgfbr2 mutant palatal mesenchymal cells and evidence of impaired sonic hedgehog (SHH) signaling. We were able to rescue cleft palate in Tgfbr2 mutant mice via a pharmacological approach that corrected the altered p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) activation and lipid metabolic defects. Thus, the lipid metabolic pathway appears to be a functionally relevant downstream target of altered noncanonical TGFβ signaling. Furthermore, we suggest that prenatal pharmacological interventions that modulate the activity of the lipid metabolic pathway may reduce the risk of orofacial clefting caused by aberrant TGFβ signaling.

RESULTS

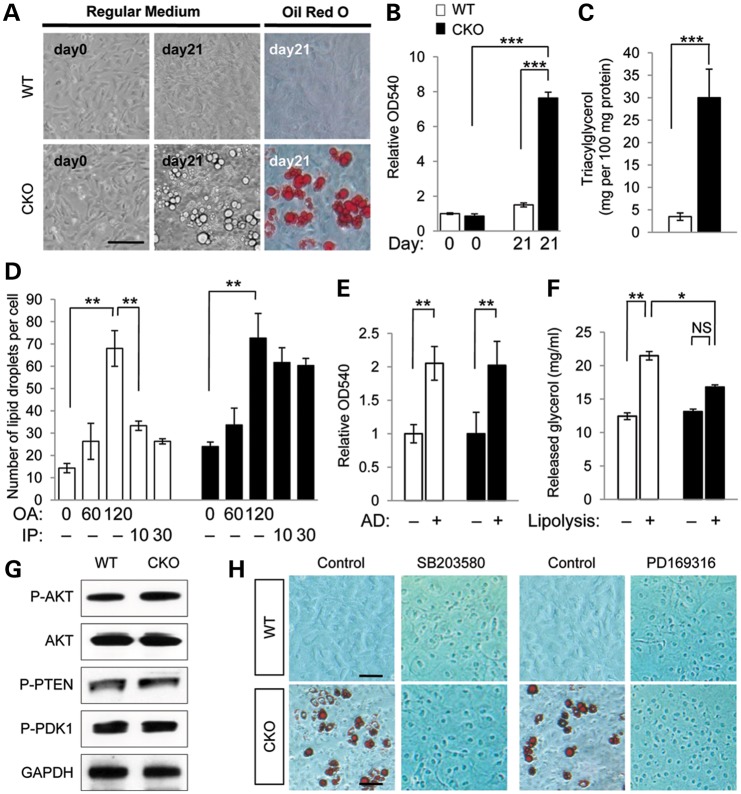

Tgfbr2 mutant CNC cells have reduced lipolytic activity and accumulate lipid droplets

Loss of Tgfbr2 results in altered TGFβ signaling activity and cleft palate in mice (13). We found that lipid droplets accumulated in the E14.5 palatal mesenchyme of Tgfbr2fl/fl;Wnt1-Cre mice (Supplementary Material, Fig. S1). The cells with lipid droplet accumulation in the E14.5 palate had a shape that was fibroblastic, but not adipocyte-like (Supplementary Material, Fig. S1B). To investigate the cellular behavior of Tgfbr2 mutant cells, we cultured primary mouse embryonic palatal mesenchymal (MEPM) cells derived from the E13.5 palates of Tgfbr2fl/fl;Wnt1-Cre and littermate control mice. We found that Tgfbr2 mutant MEPM cells spontaneously accumulated intracellular lipid droplets (Fig. 1A). We quantified lipid droplet accumulation by Oil Red O staining (Fig. 1B) and measured amounts of cellular triacylglycerol (TAG), which is the major component of lipid droplets in cells (Fig. 1C).

Figure 1.

Spontaneous accumulation of lipid droplets in Tgfbr2 mutant cells resulting from a defect in lipolysis. (A) Primary MEPM cells from Tgfbr2fl/fl (WT) and Tgfbr2fl/fl;Wnt1-Cre (CKO) mice cultured in regular medium for 0 or 21 days. Lipid droplets were stained with Oil Red O. Bar, 50 μm. (B) Quantitative analysis of lipid accumulation by Oil Red O staining in WT (white bar) and CKO (black bar) MEPM cells. Data are OD490 measurements. ***P<0.001. (C) Triacylglycerol level in WT and CKO MEPM cells cultured for 21 days. Data are expressed as mg per 100 mg protein. ***P < 0.001. (D) Pulse-chase analysis of lipid droplet formation using chemical inducers, oleic acid (OA) for lipogenesis (after 0, 60 and 120 min) and isoproterenol (IP) for lipolysis (after 10 and 30 min), in MEPM cells of WT and CKO mice. **P < 0.01. (E) Quantitative analysis of adipogenesis by Oil Red O staining in WT and CKO MEPM cells after 1 week of culture in adipogenic induction (+) or regular medium (−). Data are relative OD490 measurements. **P < 0.01. (F) Quantitative analysis of glycerol released into the medium by isoproterenol stimulation (+) or mock treatment (−) in MEPM-derived adipocytes of WT and CKO mice. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; NS, not significant. (G) Immunoblotting analysis of indicated molecules related to AKT signaling in MEPM cells from WT and CKO mice. (H) Oil Red O staining of MEPM cells from WT and CKO mice treated without (control) or with p38 MAPK inhibitor SB203580 or PD169316 for 3 weeks. Bars, 20 μm.

To explore the metabolic basis for lipid droplet accumulation in Tgfbr2 mutant MEPM cells, we performed pulse-chase analyses using oleic acid, which is an inducer of lipid droplet formation, and isoproterenol, which is a nonspecific β-adrenergic agonist that serves as a chemical inducer of lipolysis (Fig. 1D). The number of lipid droplets increased by 4-fold in MEPM cells of both control and Tgfbr2 mutant mice following oleic acid treatment. Upon switching to isoproterenol-containing growth medium, the number of lipid droplets decreased immediately in control MEPM cells but remained high in Tgfbr2 mutant MEPM cells. The non-responsiveness of the Tgfbr2 mutant MEPM cells to isoproterenol suggests decreased lipolytic activity downstream of altered TGFβ signaling.

To compare the efficiency of induction of adipocyte fate in MEPM cells of control and Tgfbr2 mutant mice, we cultured primary MEPM cells from control and Tgfbr2 mutant mouse embryos in adipocyte differentiation medium for 1 week. The resulting adipocytes derived from Tgfbr2 mutant and control MEPM cells were indistinguishable in both number and appearance, which suggests that altered TGFβ signaling does not affect CNC cell differentiation into adipocytes (Fig. 1E; Supplementary Material, Fig. S2). After isoproterenol stimulation, the released glycerol levels in Tgfbr2 mutant CNC-derived adipocytes were lower than those of controls (Fig. 1F), consistent with a defect in lipolytic activity.

Next, we tested whether lipid accumulation in the palatal mesenchyme resulted from alterations in insulin signaling, carbohydrate metabolism or glucose uptake via activation of the serine/threonine protein kinase AKT (a.k.a. protein kinase B) signaling pathway (14,15). Based on immunoblot analysis of phosphorylated AKT, regular AKT, phosphorylated phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN), and phosphorylated 3-phosphoinositide-dependent protein kinase-1 (PDK1, a.k.a. PDPK1) protein levels, we detected no evidence of altered AKT signaling activity in Tgfbr2 mutant MEPM cells compared with controls (Fig. 1G). We therefore conclude that the observed defect is unlikely to be due to changes in insulin signaling, carbohydrate metabolism, or glucose uptake via AKT signaling.

We have recently reported that p38 MAPK signaling is selectively activated in the palate of Tgfbr2fl/fl;Wnt1-Cre mice (13). To inhibit the p38 MAPK pathway, we treated Tgfbr2 mutant and control MEPM cells with the p38 MAPK inhibitors SB203580 and PD169316. After treatment, we failed to detect lipid droplet accumulation in the Tgfbr2 mutant MEPM cells, consistent with elevated p38 MAPK activity involvement in lipid droplet accumulation in these cells (Fig. 1H; Supplementary Material, Fig. S3).

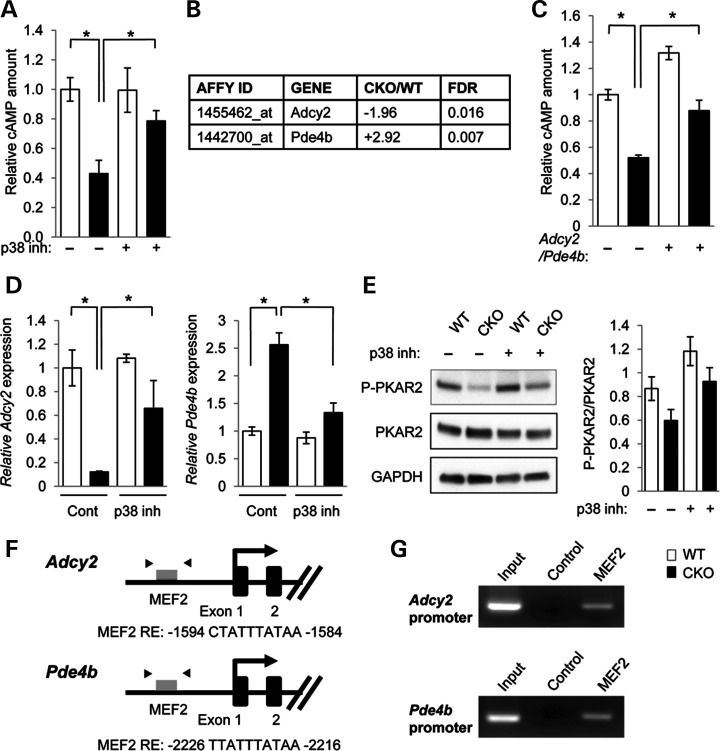

Identification of candidate downstream metabolic targets of altered TGFβ signaling

The ability to synthesize and store neutral lipids in cytoplasmic lipid droplets is a universal property of eukaryotes from yeast to humans (16). TAG, which is a neutral lipid and the main component of lipid droplets, is degraded into free fatty acids and glycerol (16). A previous study in rodents has reported that the lipid composition detected in cleft palate includes an accumulation of diglycerides and a reduction in free fatty acids, suggesting that rodents with cleft palate have a defect in lipolysis (17). In addition, previous studies demonstrate that altered adenosine 3′, 5′-cyclic monophosphate (cAMP)-PKA signaling causes cleft palate in mice (18,19). We hypothesized that altered cAMP levels could play a role in this defect because cAMP induces phosphorylation and activation of lipid droplet-associated proteins and lipases via cAMP-dependent protein kinase (PKA; EC 2.7.1.37) (20). To examine cAMP levels in MEPM cells, we measured the total amount of cAMP in control and Tgfbr2 mutant MEPM cells. We found that cAMP was reduced in Tgfbr2 mutant MEPM cells and restored after p38 MAPK inhibitor SB203580 treatment (Fig. 2A).

Figure 2.

Identification of target molecules regulating lipid metabolism in Tgfbr2 mutant cells. (A) Quantitation of cAMP levels in the MEPM cells of Tgfbr2fl/fl (WT, white bars) and Tgfbr2fl/fl;Wnt1-Cre (CKO, black bars) mice. *P < 0.05. (B) Summary of microarray analysis results from MEPM cells of WT and CKO mice. Forty-seven gene transcripts were down-regulated in Tgfbr2fl/fl;Wnt1-Cre MEPM cells compared with Tgfbr2fl/fl MEPM cells. Forty-four gene transcripts were up-regulated in CKO MEPM cells compared with WT MEPM cells. n = 4 per genotype. Altered gene expression of 5′-cyclic monophosphate (cAMP) regulators is listed. (C) Measurement of cAMP in the MEPM cells of WT and CKO mice after Adcy2 overexpression and Pde4b siRNA knock-down (+) or control treatment (−). *P < 0.05. (D) Quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT–PCR) analyses of Adcy2 and Pde4b in WT and CKO MEPM cells after treatment with p38 MAPK inhibitor SB203580 (p38 inh.) or no drug control (Cont.). *P < 0.05. (E) Immunoblotting analysis of indicated molecules related to PKA signaling in MEPM cells from WT and CKO mice treated with (+) or without (−) p38 inhibitor. Bar graphs (right) show the ratios of phosphorylated PKAR2 to PKAR2 following quantitative densitometry analysis of immunoblotting data. *P < 0.05. (F) Schematic diagram of mouse Adcy2 and Pde4b promoter regions showing putative MEF2 response elements (REs) identified by genomatix software within the Adcy2 and Pde4b genes. Arrowheads indicate the position of primers used in ChIP analysis. (G) ChIP analysis to detect MEF2 binding of the Adcy2 and Pde4b promoter in MEPM cells. PCR was performed using primers indicated in Materials and Methods.

To identify candidate molecules related to lipid metabolic aberrations and cAMP regulation following the loss of Tgfbr2, we performed microarray analysis using MEPM cells from Tgfbr2fl/fl control and Tgfbr2fl/fl;Wnt1-Cre mice (n = 4 per genotype). In this comparison, we uncovered 91 probe sets representing transcripts that were differentially expressed [≥1.5-fold, <5% false discovery rate (FDR)], 44 more abundant in Tgfbr2 mutant MEPM cells and 47 more abundant in control MEPM cells (Supplementary Material, Table S1). Note that there is no difference in gene expression of adipocyte differentiation markers between MEPM cells from Tgfbr2fl/fl control and Tgfbr2fl/fl;Wnt1-Cre mice (Supplementary Material, Table S2 and Fig. S2). We focused on the gene expression profiles for regulators that could tip the balance between cAMP synthesis by adenynyl cyclases and degradation by cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterases, thereby altering cellular cAMP levels. We discovered that gene expression of Adcy2 was significantly down-regulated (1.96-fold, FDR = 0.016) while Pde4b expression was significantly upregulated (2.92-fold, FDR = 0.007) in Tgfbr2 mutants relative to control MEPM cells (Fig. 2B). To assess the functional significance of Adcy2 and Pde4b, we measured cAMP levels after Adcy2 overexpression and Pde4b siRNA knockdown in Tgfbr2 mutant MEPM cells. We found that reversing the expression of both Adcy2 and Pde4b in Tgfbr2 mutant MEPM cells restored the amounts of cAMP and lipid droplet accumulation to control levels (Fig. 2C; Supplementary Material, Fig. S4A). Moreover, the expression levels of Adcy2 and Pde4b in Tgfbr2 mutant MEPM cells were restored to control levels after treatment with p38 MAPK inhibitor SB203580, suggesting that noncanonical TGFβ signaling through the p38 MAPK pathway regulates Adcy2 and Pde4b gene expression in Tgfbr2 mutant MEPM cells (Fig. 2D). To test the hypothesis that altered p38 MAPK activation suppresses PKA activity in Tgfbr2 mutant cells, we assessed phosphorylation of PKA regulatory subunit type II (PKAR2) in MEPM cells after treatment with p38 MAPK inhibitor SB203580. We found that PKAR2 activation was decreased in Tgfbr2 mutant MEPM cells compared with controls and restored after treatment with SB203580 (Fig. 2E).

Next, we analyzed the sequences of the mouse Adcy2 and Pde4b genes [5-kb upstream and 5-kb downstream of their transcription start sites (TSS), respectively] for conserved transcription factor binding site motifs in orthologous mouse, rat and human sequences (Fig. 2F). The Adcy2 and Pde4b genomic regions contained myocyte enhancer factor-2 (Mef2c) recognition sites, raising the possibility that noncanonical TGFβ signaling through the p38 MAPK pathway may regulate the expression of these genes (21–24). A previous study indicates that Mef2c induces or suppresses gene expression of various target molecules in different transcription factor complexes (25). We performed a chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay for Mef2c on the promoter regions of Adcy2 and Pde4b and found that Mef2c recognition sites were immunoprecipitated by anti-Mef2c antibody, indicating that Mef2c can bind to these sites on the promoter regions of Adcy2 and Pde4b (Fig. 2G). Thus, noncanonical TGFβ signaling may lead to reduced cAMP levels and lipolysis activities seen in the Tgfbr2 mutant, as well as alterations in other lipid metabolic pathways.

To confirm that the accumulation of lipid droplets in Tgfbr2 mutant MEPM cells is not the result of a cell fate change to adipocytes, we screened for the presence of adipocyte gene expression markers (e.g. Pparg, Fabp4, Ucp1 and Lep1) in MEPM cells from Tgfbr2 mutant and control mice (Supplementary Material, Table S2). We found no changes in the expression levels of these genes, consistent with the conclusion that CNC-derived palatal mesenchymal cells are accumulating lipid droplets and not transdifferentiating into adipocytes. Taken together, our findings suggest that decreased cellular cAMP levels may contribute to the altered lipid metabolic activity in Tgfbr2 mutant palatal mesenchyme.

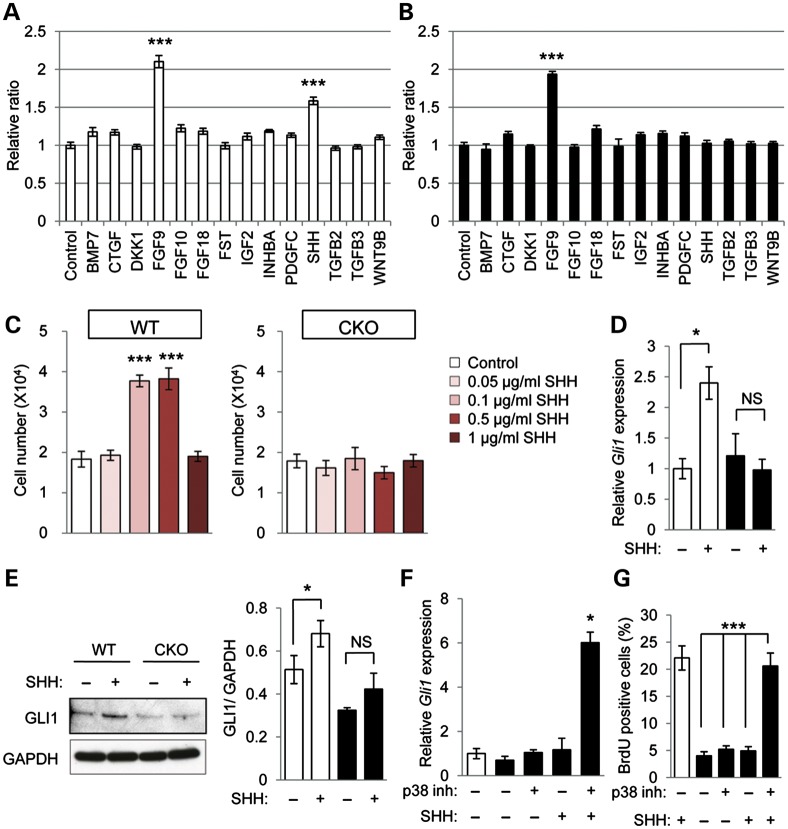

Compromised SHH signaling in Tgfbr2 mutant palatal mesenchymal cells

Our previous studies have shown that loss of Tgfbr2 results in a CNC cell proliferation defect and causes cleft palate (13,26). To address the question of how lipid metabolic aberrations may be responsible for a defect in cell proliferation in Tgfbr2fl/fl;Wnt1-Cre mice, we investigated cell proliferation in MEPM cells of Tgfbr2 mutant and control mice. Candidate growth factors (BMP7, CTGF, DKK1, FGF9, FGF10, FGF18, FST, IGF2, INHBA, PDGF-C, SHH, TGFβ2, TGFβ3 and WNT9B) were selected from previously identified cleft palate phenotypes (275 mouse lines with a cleft palate phenotype) in genetically engineered mouse models (27). We tested these candidate molecules in cell proliferation assays of wild-type and Tgfbr2 mutant MEPM cells with these growth factors and found that only SHH and FGF9 strongly induce cell proliferation activity in control MEPM cells, while the other growth factors failed to induce cell proliferation activity (Fig. 3A). SHH failed to induce cell proliferation activity in Tgfbr2 mutant MEPM cells, but FGF9 was able to induce proliferation, suggesting that SHH signaling is compromised in Tgfbr2 mutant MEPM cells (Fig. 3B). During palatogenesis, SHH is derived from epithelial cells and strongly stimulates mesenchymal cell proliferation (28). Mice with an epithelial cell-specific deletion of Shh (Shhfl/fl;K14-Cre) exhibit cleft palate resulting from a defect in mesenchymal cell proliferation (Supplementary Material, Fig. S5), consistent with previous findings in mice with a single allele of an epithelial cell-specific deletion of Shh in a Shh heterozygous null background (Shhc/n;K14-Cre) (29,30). Interestingly, SHH signaling activities are closely associated with lipid metabolism and are regulated by the amount of intracellular cholesterol in SHH-responsive cells (31,32). Therefore, we hypothesized that the lipid metabolic aberrations in mesenchymal cells result in a cell proliferation defect due to loss of responsiveness to the SHH ligand derived from palatal epithelial cells. To address this hypothesis, we investigated the effect of exogenous SHH protein on cell proliferation in Tgfbr2 mutant and control MEPM cells (Fig. 3C). Control MEPM cells responded to 0.1 or 0.5 μg/ml of SHH. In contrast, SHH addition had no effect on the cell proliferation activity of Tgfbr2 mutant MEPM cells. We also analyzed Gli1 gene and GLI1 protein expression after SHH treatment, since SHH induces Gli1 expression during palate formation (33). We found that SHH fails to induce either Gli1 gene or GLI1 protein expression in Tgfbr2 mutant MEPM cells, although both gene and protein expression of GLI1 increased in control MEPM cells after SHH treatment (Fig. 3D and E). To assess the role of altered p38 MAPK activation in the failure of Tgfbr2 mutant cells to respond to SHH, we treated mutant MEPM cells with p38 MAPK inhibitor and SHH together and found that Gli1 expression increased (Fig. 3F). These data indicate that altered p38 MAPK activation is responsible for loss of SHH signaling.

Figure 3.

SHH response is impaired in Tgfbr2 mutant cells. (A and B) Cell proliferation assays in Tgfbr2fl/fl littermate (white bars, A) and Tgfbr2fl/fl;Wnt1-Cre (black bars, B) mice after 24 h of culturing with indicated molecules. ***P < 0.001. (C) Cell proliferation assays of MEPM cells from WT and CKO mice after 24 h of culturing with various concentrations of SHH protein (0, 0.1, 0.5 and 1.0 μg/ml). ***P < 0.001. (D) Quantitative RT–PCR analyses of Gli1 with (+) or without (−) SHH treatment in WT and CKO MEPM cells. *P < 0.05. NS, not significant. (E) Immunoblotting analysis of GLI1 expression with (+) or without (−) SHH in MEPM cells of WT and CKO mice. Bar graph (right) shows the ratio of GLI1 to GAPDH following quantitative densitometry analysis of immunoblotting data. *P < 0.05. NS, not significant. (F) Quantitative RT–PCR analyses of Gli1 with (+) or without (−) p38 MAPK inhibitor and/or SHH treatment in WT and CKO MEPM cells. *P < 0.05. (G) BrdU incorporation assay after treatment of MEPM cells from WT and CKO mice with (+) or without (−) p38 MAPK inhibitor and/or SHH. Bar graph shows the percentage of BrdU-positive cells. ***P < 0.001.

Next, we tested whether treatment with p38 MAPK inhibitor and/or SHH could rescue the cell proliferation defect in Tgfbr2 mutant MEPM cells. After treatment with both p38 MAPK inhibitor and SHH, but not either alone, cell proliferation activity in Tgfbr2 mutant MEPM cells was restored to the level of controls (Fig. 3G; Supplementary Material, Fig. S6A). Thus, our data suggest that loss of Tgfbr2 in CNC cells results in lipid metabolic aberrations that are responsible for compromised SHH signaling, and therefore cause reduced mesenchymal cell proliferation.

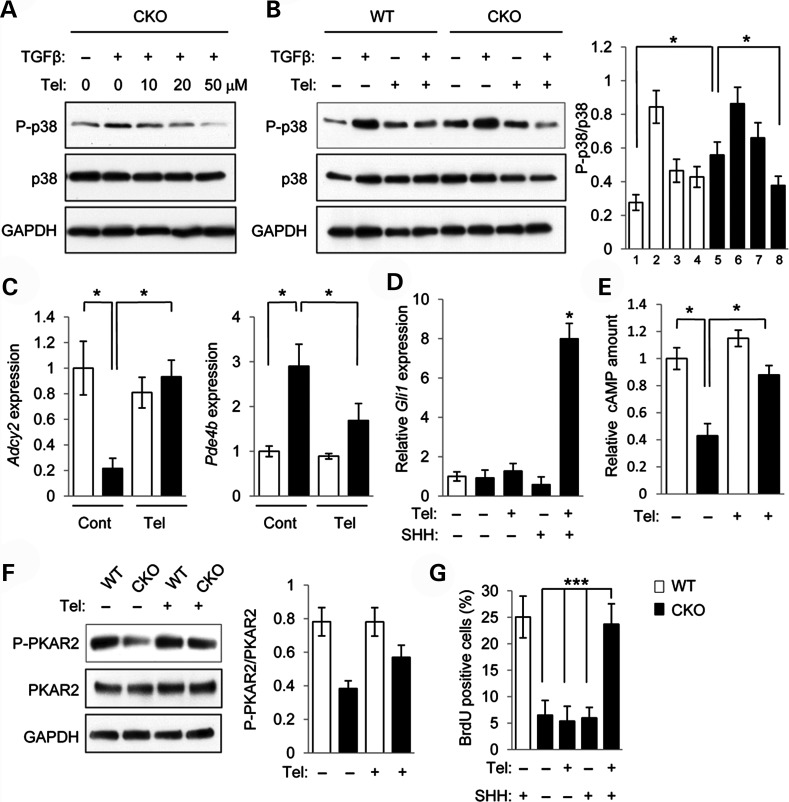

Clinically, angiotensin II receptor blocker (ARB) telmisartan acts as an antagonist of TGFβ signaling, inhibits p38 MAPK, and has been shown to influence lipid metabolic activity (34,35). Therefore, we tested whether treatment with telmisartan and SHH together can normalize cell proliferation activity in Tgfbr2 mutant MEPM cells. Telmisartan inhibited altered p38 MAPK activation in Tgfbr2 mutant MEPM cells when administered at concentrations between 20 and 50 μm (Fig. 4A). Telmisartan suppressed TGFβ-mediated p38 MAPK activation in these mutant MEPM cells (Fig. 4B). In addition, gene expression of Adcy2 and Pde4b was restored in Tgfbr2 mutant MEPM cells after treatment with telmisartan (Fig. 4C). As expected, Gli1 expression was increased after the treatment with both telmisartan and SHH (Fig. 4D). Furthermore, the cAMP level and PKAR2 activation were normalized in Tgfbr2 mutant MEPM cells after treatment with telmisartan (Fig. 4E and F). Lipid droplet accumulation in Tgfbr2 mutant MEPM cells was blocked by the treatment with telmisartan (Supplementary Material, Fig. S4B). Finally, after the treatment with both telmisartan and SHH, but not telmisartan alone or SHH alone, cell proliferation activity was restored to control levels in Tgfbr2 mutant MEPM cells (Fig. 4G; Supplementary Material, Fig. S6B). Taken together, these data suggest that telmisartan is a potential p38 MAPK inhibitor and can block alternative TGFβ signaling in Tgfbr2 mutant palatal mesenchymal cells.

Figure 4.

Telmisartan restores p38 MAPK activation and cell proliferation activity in Tgfbr2 mutant cells. (A) Immunoblotting analysis of indicated molecules after treatment with telmisartan at indicated concentrations and addition (+) or no addition (−) of TGFβ in MEPM cells from Tgfbr2fl/fl;Wnt1-Cre (CKO) mice. (B) Immunoblotting analysis of indicated molecules in MEPM cells from Tgfbr2fl/fl (WT) and Tgfbr2fl/fl;Wnt1-Cre (CKO) mice after treatment with (+) or without (−) TGFβ and/or telmisartan. Bar graph (right) shows the ratios of phosphorylated p38 to p38 following quantitative densitometry analysis of immunoblotting data. White bars, WT; black bars, CKO. (C) Quantitative RT–PCR analyses of Adcy2 and Pde4b in WT and CKO MEPM cells with (Tel.) or without (Cont.) telmisartan treatment. *P < 0.05. (D) Quantitative RT–PCR analyses of Gli1 in WT and CKO MEPM cells with (+) or without (−) telmisartan treatment. *P < 0.05. (E) Quantitation of cAMP levels in the MEPM cells of WT and CKO mice after telmisartan treatment (+) or no treatment (−). *P < 0.05. (F) Immunoblotting analysis of indicated molecules after treatment with (+) or without (−) telmisartan in MEPM cells from WT and CKO mice. Bar graph (right) shows the ratios of phosphorylated PKAR2 to PKAR2 following quantitative densitometry analysis of immunoblotting data. (G) BrdU incorporation assay after treatment with (+) or without (−) telmisartan and/or SHH in MEPM cells from WT and CKO mice. Bar graph shows the percentage of BrdU-positive cells. ***P < 0.001.

Rescue of cleft palate by prenatal telmisartan treatment

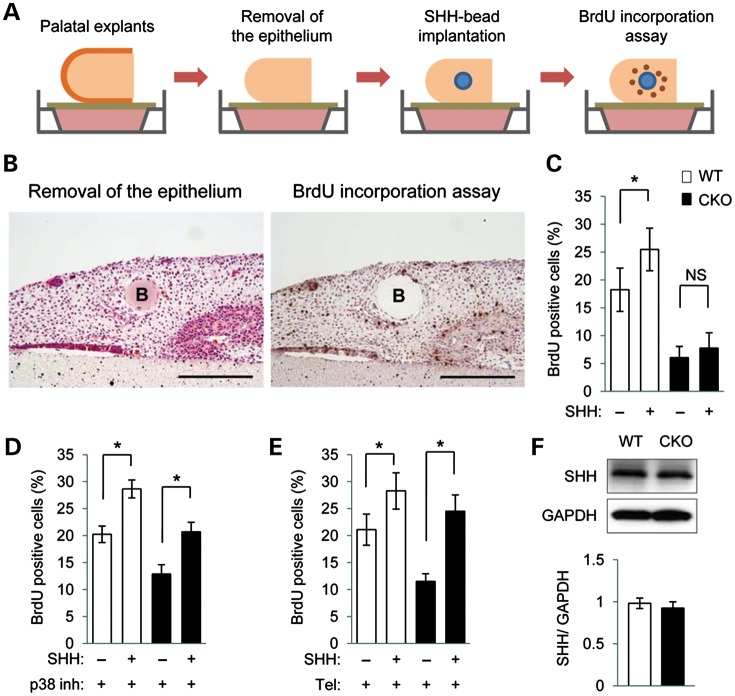

To test our model in an ex vivo organ culture system, we implanted SHH-containing beads into Tgfbr2 mutant and control palatal explants with the palatal epithelium removed and assessed cell proliferation (Fig. 5A and B). SHH-induced cell proliferation in control but not Tgfbr2 mutant palates (Fig. 5C). To test whether altered p38 MAPK activation is responsible for cell proliferation activity, we treated palatal tissues with p38 MAPK inhibitor and SHH for 24 h. After the treatment with both p38 MAPK inhibitor and SHH, reduced cell proliferation activity was restored to control levels in the Tgfbr2 mutant palates (Fig. 5D). Similarly, the cell proliferation defect in the Tgfbr2 mutant palates was rescued after treatment with both telmisartan and SHH (Fig. 5E). Protein expression levels of SHH were similar in the palates of both control and Tgfbr2 mutant mice at E14.5, indicating that SHH expression is not affected by loss of Tgfbr2 in the palatal mesenchyme (Fig. 5F).

Figure 5.

SHH response is normalized in Tgfbr2 mutant palates after treatment with p38 MAPK inhibitor or telmisartan. (A) Schematic diagram of sample preparation and assay. Palatal explants with the palatal epithelium removed were cultured with BSA or SHH-containing beads for 24 h. BrdU staining was performed to measure cell proliferation activity. (B) H&E (left) and BrdU (right) staining of Tgfbr2fl/fl;Wnt1-Cre palatal explants 24 h after epithelium removal and implantation of SHH-containing beads. B, bead. Bars, 200 μm. (C) Quantification of BrdU-positive cells in bead implantation samples. White bars, WT; black bars, CKO. NS, not significant. Five samples per group were used. *P < 0.05. (D) Quantitation of the percentage of BrdU-labeled nuclei in the palates of WT and CKO mice treated with p38 MAPK inhibitor and SHH (+) or BSA control (−) beads for 24 h. *P < 0.05. (E) Quantitation of the percentage of BrdU-labeled nuclei in the palates of WT and CKO mice treated with telmisartan and SHH (+) or BSA control (−) beads for 24 h. *P < 0.05. (F) Immunoblotting analysis of SHH in the palates of WT and CKO mice at E14.5. Bar graph (below) shows the ratio of SHH to GAPDH following quantitative densitometry analysis of immunoblotting data.

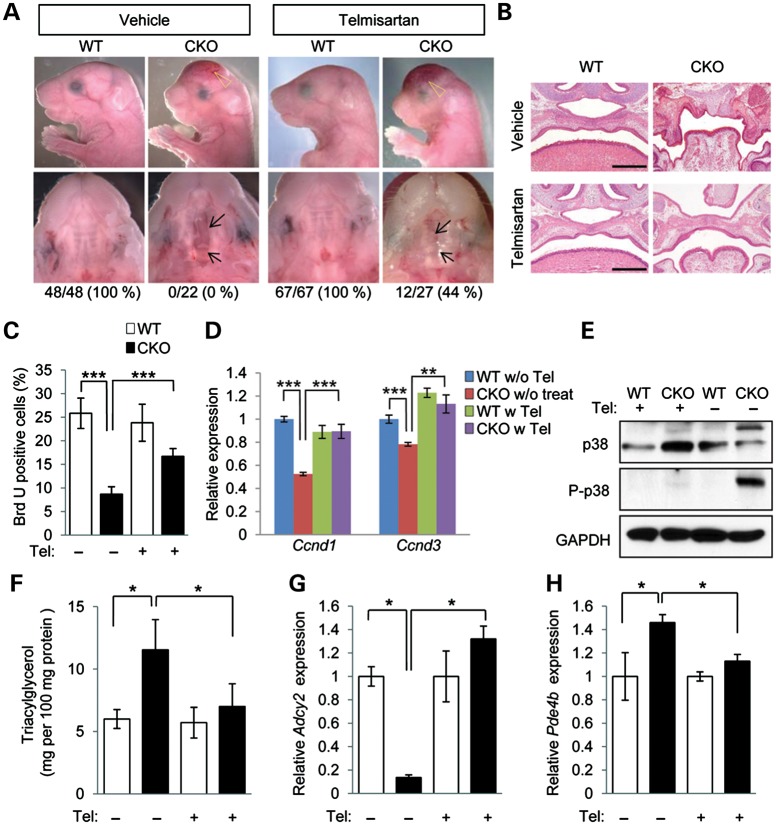

Our lines of in vitro and ex vivo evidence converge to suggest strongly that the modulation of lipid metabolism by telmisartan could rescue cleft palate in Tgfbr2 mutant mice. To test this, telmisartan was administered to pregnant mice (20 mg/kg body weight per day) from E11.5 to E15.5. Significantly, cleft palate was rescued by telmisartan treatment in 44% (12/27 animals) of the Tgfbr2fl/fl;Wnt1-Cre pups from these litters (Fig. 6A and B). We detected no obvious side effects to other organs in the mice after treatment with telmisartan (Supplementary Material, Fig. S7). The cell proliferation defect observed in Tgfbr2 mutant mice was restored after the treatment with telmisartan (Fig. 6C and D). The elevated p38 MAPK activity in the pups was reduced to control levels after telmisartan treatment (Fig. 6E). Furthermore, telmisartan treatment resulted in the normalization of TAG levels in the palate of the Tgfbr2 mutant mice (Fig. 6F). Gene expression of Adcy2 and Pde4b was also restored in E14.5 Tgfbr2 mutant mice after the treatment with telmisartan (Fig. 6G and H). Thus, we propose that loss of Tgfbr2 in CNC cells results in lipid metabolic aberrations that are responsible for compromised SHH signaling, reduced mesenchymal cell proliferation and cleft palate (Supplementary Material, Fig. S8).

Figure 6.

Prevention of cleft palate in Tgfbr2 mutant embryos by telmisartan. (A) Lateral, frontal and palatal views of Tgfbr2fl/fl littermate (WT) and Tgfbr2fl/fl;Wnt1-Cre (CKO) mice after treatment with vehicle or telmisartan. Arrows indicate the edge of the palate. Open arrowheads show defects in the frontal bone. Appearance of the palate was scored as normal or cleft (below). (B) Histological observation of WT and CKO mice after treatment with vehicle or telmisartan. Lower panels show higher magnification of upper panels. Bars, 500 μm (upper panels) and 200 μm (lower panels). (C) Quantification of BrdU-positive cells in E14.5 palate of Tgfbr2fl/fl (WT) and Tgfbr2fl/fl;Wnt1-Cre (CKO) mice with or without telmisartan treatment. White bars, WT; black bars, CKO. Three samples per group were used. ***P < 0.001. (D) Quantitative RT–PCR analyses of Ccnd1 and Ccnd3 in WT and CKO MEPM cells with (w) or without (w/o) telmisartan (Tel) treatment. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. (E) Immunoblotting analysis of p38 and phosphorylated p38 (P-p38) in WT and CKO mice after treatment with vehicle (−) or telmisartan (+). (F) Triacylglycerol level in E18.5 WT (white bars) and CKO (black bars) mice after treatment with telmisartan (+) or vehicle (−). *P < 0.05. (G and H) Quantitative RT–PCR analyses of Adcy2 (E) and Pde4b (F) in E14.5 WT and CKO palates. *P < 0.05.

DISCUSSION

Although aberrant TGFβ signaling is known to cause cleft palate in humans and genetically engineered mice, the downstream mechanisms responsible for these craniofacial malformations have not yet been fully elucidated (8). In prior work, we demonstrated that there are cell proliferation defects in palatal tissue from Tgfbr2fl/fl;Wnt1-Cre mouse embryos at E14.5 (13). Given the wealth of evidence that aberrant lipid metabolism can lead to cleft palate in humans and genetically engineered mice, we hypothesized that alterations in lipid homeostasis could contribute to cleft palate in Tgfbr2fl/fl;Wnt1-Cre mouse embryos.

As an entry point into the investigation of altered lipid homeostasis, we focused on the accumulation of TAG in lipid droplets in Tgfbr2 mutant MEPM cells. TAG is degraded into free fatty acids and glycerol (16). A previous study reported that the lipid composition detected in rats with cleft palate includes an accumulation of diglycerides and a reduction of free fatty acids, suggesting a defect in lipolysis (17). To investigate the mechanistic basis for TAG accumulation in Tgfbr2 mutant cells, we treated MEPM cells with chemical reagents that are agonists for lipolysis and found that TAG levels were normalized by p38 MAPK inhibitor and telmisartan. Our data therefore indicate that reduced lipolysis activity is responsible for the elevated cellular TAG levels and lipid droplets in Tgfbr2 mutant cells. Our observation that the palates from Tgfbr2 mutant mice show reduced cAMP levels is consistent with this notion since cAMP levels regulate lipolysis via the PKA pathway (20). Intriguingly, there are dynamic changes in cAMP levels and ADCY activity in the palate during development, and toxins that induce cleft palate have an inhibitory effects on palatal cAMP and ADCY (19).

Under low levels of cAMP, the PKA holoenzyme remains intact and is catalytically inactive. In humans and animals, the cellular processes under the regulation of cAMP/PKA play crucial roles in the development of the secondary palate (19). The phosphorylation of PKA results in a change in the activity of lipid droplet-associated proteins and lipases (20). Our results suggest that TGFβ may mediate cAMP regulation via gene expression of Adcy2 and Pde4b, and regulate lipid metabolism and cell proliferation during palate formation. Thus, noncanonical TGFβ signaling may lead to reduced cAMP levels and compromised lipolysis activities as well as alterations in other lipid metabolic pathways.

Telmisartan is one of the few potential drugs that may affect lipolysis. It was originally classified as an ARB, but was recently reported to have an additional function, namely modulating p38 MAPK activation and lipid metabolism (34,35). We found that palatal fusion is rescued in 44% of Tgfbr2 mutant mice following telmisartan treatment. Interestingly, though telmisartan rescued cleft palate in Tgfbr2 mutant mice, it did not rescue the defects in calvarial, mandibular, lingual and cardiovascular development found in these mice. One possible explanation is that SHH expression is restricted to the palatal rugae. Therefore, a reduction of lipid accumulation alone does not prevent other developmental defects, but rather only affects SHH-responding cells in the palatal mesenchyme. This reasoning is supported by the previous finding that Shh knock-out mice exhibit a phenotype that is noticeable mainly in the palate (30). Alternatively, based on phenotypes of mice with mutations in genes related to lipid metabolism, CNC cells might be more sensitive to lipid metabolic aberrations than cells in other regions of the body (31,36,37). The co-occurrence of a lipid metabolic defect and SHH signaling aberration may be associated with the observed phenotypes. The rescue of cell proliferation and Gli expression by a p38 inhibitor may be independent of the function of GLI in rescuing lipid phenotypes. The observed phenotypes may also be a combination of SHH expression and lipid metabolic aberrations.

Our findings shed new light on the functionally relevant downstream targets of aberrant TGFβ signaling that are responsible for cleft palate in Tgfbr2fl/fl;Wnt1-Cre mice. We provide evidence that altered lipid metabolic activity may affect cellular response to SHH signaling. These results may be relevant to maternal metabolic risk factors for cleft palate, including diabetes and obesity. Given the increasingly elevated prevalence of these conditions in developed nations, a better understanding of the role that the lipid metabolic pathway plays in palatogenesis could have a significant impact on diagnosing orofacial clefting. Furthermore, our findings highlight future opportunities for designing new medicines to prevent cleft palate in families with a high risk of clefting, such as those with Loeys–Dietz syndrome or lipid metabolic defects.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

All mice were genotyped and maintained as previously described (26) and were handled in accordance with protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Southern California. C57BL/6J mice served as the genetic background in this study. To generate Tgfbr2fl/fl;Wnt1-Cre mice, we mated Tgfbr2fl/+;Wnt1-Cre with Tgfbr2fl/fl mice. Female Tgfbr2fl/fl mice, which underwent timed mating with Tgfbr2fl/+;Wnt1-Cre male mice, were treated via feeding tube with oral telmisartan (20 mg/kg body weight per day) or vehicle (dimethyl sulfoxide) from E11.5 to E15.5.

Histological examination

Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) staining and BrdU staining were performed as described previously (13). Cryosections were stained with Oil Red O to detect lipid production. Prepared sections were washed three times in phosphate-buffered saline for 5 min each and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 m phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) for 1 h at 4°C. Sections were then incubated for 15 min in 60% isopropanol and stained for 15 min with a filtered solution of three parts Oil Red O (saturated in isopropanol) and two parts ddH2O. Next, slides were briefly rinsed in 60% isopropanol and washed thoroughly in ddH2O. Sections were counterstained with Mayer's hematoxylin.

Assays

Triglyceride levels were measured with an enzymatic method using N-ethyl-N-(2-hydroxy-3-sulfopropyl)-3,5-dimethoxyaniline sodium salt according to the manufacturer's instructions (Wako, Tokyo, Japan). Data are expressed as microgram per 100 mg protein. cAMP levels were measured using a competition enzyme-linked immunoassay according to the manufacturer's instructions (BioVision).

Cell culture

Primary MEPM cells were obtained from E13.5 embryos as described previously (13). Adipogenic differentiation was induced by culture in a monolayer for 1 week after initial seeding of the cells at 1.5 × 104 cells/cm2 in complete medium supplemented with 1 μmol/l dexamethasone, 1 μg/ml insulin, and 0.5 mmol/l 3-isobutyl-1-methylxantine. Lipids were stained with Oil Red O, dissolved in isopropanol, and then measured in a spectrometer. Data are expressed as results at OD540 nm. Quantitative analyses of glycerol released into the medium by isoproterenol stimulation were performed using an Adipolysis Assay Kit according to the manufacturer's instructions (Cayman, MI, USA). MEPM cells were treated with or without p38 MAPK inhibitor (SB203580 or PD169316) at 10 μm, telmisartan at 20 μm or Adcy2 overexpression/Pde4b siRNA for 3 weeks. In BrdU incorporation assays, MEPM cells were treated with or without p38 MAPK inhibitor SB203580 (10 μm) or telmisartan (20 μm) and/or SHH (0.5 μg/ml) for 3 days and then incubated with BrdU for 1 h. BrdU staining was performed according to the manufacturer's instructions (Invitrogen).

Palatal shelf organ culture

Timed pregnant mice were sacrificed at E13.5. Genotyping was carried out as described above. The palatal shelves were microdissected, then incubated with 2.5% dispase for 10 min at room temperature. Palatal epithelium was mechanically removed and the remaining palates were cultured in serum-free chemically defined medium as previously described (27). After 24 h in culture with or without p38 MAPK inhibitor SB203580 (100 μm) or telmisartan (50 μm) and/or SHH beads (25 μg/ml), palates were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 m phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) and processed. All experiments were performed on at least five samples.

Pulse-chase analysis of lipid droplet formation

Chemical inducers, oleic acid for lipogenesis and isoproterenol for lipolysis, were added into culture medium to analyze lipid droplet formation. The number of lipid droplets per cell was counted after Oil Red O staining. Oleic acid was added to the medium at 100 μm for 0, 60 and 120 min, then washed out and changed to medium with 100 μm isoproterenol up to 30 min. Twenty cells were counted at each time point.

Immunoblot analysis

Immunoblots were performed as described previously (38,39). Antibodies used for immunoblotting were as follows: rabbit monoclonal antibody against phosphorylated PKAR2 (Abcam); rabbit polyclonal antibodies against phosphorylated p38, AKT, phosphorylated AKT (Ser473), phosphorylated PTEN, phosphorylated PDK1 (Cell Signaling Technology), PKAR2 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and GLI1 (Abcam); goat polyclonal antibody against SHH (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and mouse monoclonal antibodies against p38 (Cell Signaling Technology) and GAPDH (Millipore). Quantitative densitometry analyses of immunoblotting data were performed using three samples for each experiment. Error bars represent standard deviations.

Microarray analysis

Total RNA samples (1 μg per sample) were isolated from cultured MEPM cells after two passages in regular medium, and then converted into biotin-labeled cRNA using the GeneChip® IVT Labeling Kit and standard protocols recommended by Affymetrix (Santa Clara, CA, USA). Fragmented cDNA was applied to GeneChip® Mouse Genome 430 2.0 Arrays (Affymetrix) that contain probe sets designed to detect over 39 000 transcripts. Microarray analyses were performed as previously described (13). Probes sets showing ≥1.5-fold differential expression with a <5% FDR were identified using LIMMA (Linear Models for Microarray Data)-based linear model statistical analysis (40) and FDR calculations were made using the SPLOSH (spacings LOESS histogram) method (41). All scaled gene expression scores and .cel files are available at the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) Gene Expression Omnibus repository http://www.ncbi.nih.gov/geo/ under Series Accession Number GSE46150 (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?token=fxapvmuouqeqwdq&acc=GSE46150).

Quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT–PCR)

Total RNA was isolated from mouse embryonic palates dissected at E14.5 or from primary MEPM cells using QIAshredder and RNeasy Micro extraction kits (Qiagen). cDNA was synthesized from 1 μg of total RNA using SuperScript III (Invitrogen), and quantitative PCR was performed in triplicate using SYBR Green (Bio-Rad Laboratories) in an iCycler (Bio-Rad Laboratories), as described previously (27,38). The following PCR primers were used: Pde4b, 5′-CGCCGGCACTGGATGCTGTC-3′ and 5′-TCCTGAGTGTCTGGCGTTGCT-3′; Adcy2, 5′-AACGGCAGCAGGAACGACTTCT-3′ and 5′-CGCTTGCAAGGCGGGTGAAG-3′; Gli1, 5′-CACTGAGGACTTGTCCAGCTTG-3′ and 5′-AGCTGGGCAGTTTGAGACC-3′; Ccnd1, 5′-GGCACCTGGATTGTTCTGTT-3′ and 5′-CAGCTTGCTAGGGAACTTGG-3′; Ccnd3, 5′-ATACTGGATGCTGGAGGTGTG-3′ and 5′-TGCAGAATCAAGGCCAGGAA-3′; Pparg, 5′-TTTTCAAGGGTGCCAGTTTC-3′ and 5′-AATCCTTGGCCCTCTGAGAT-3′; Gapdh, 5′-AACTTTGGCATTGTGGAAGG-3′ and 5′-ACACATTGGGGGTAGGAACA-3′.

Transcription factor binding site analysis

The UCSC genome browser was used to obtain the genomic sequences of the mouse Pde4b (RefSeq accession NM_002600.3) and Adcy2 (RefSeq accession NM_020546.2) genes, including 5 kb upstream and 5 kb downstream of the respective TSS, based on mouse genome Build 38. Transcription factor binding motifs relevant to p38 MAPK pathway elements within or proximal to these genes (i.e. 5 kb upstream and 5 kb downstream of the human TSS for each gene) were located using MatInspector software (Genomatix).

ChIP assay

MEPM cell extracts were incubated with MEF2 antibody (Abcam) overnight at 4°C followed by precipitation with magnetic beads. Washing and elution of the immune complexes, as well as precipitation of DNA, were performed according to standard procedures. The putative MEF2 target sites of the Adcy2 and Pde4b genes in the immune complexes were detected by PCR using primers amplifying the following genomic regions: Adcy2 gene, −1594 to −1584; Pde4b gene, −2226 to −2216. Adcy2, 5′-AGGGACTGGAAATGCACAAT-3′ and 5′-CTTCTCCTGCAGGCTCAAAC-3′; Pde4b, 5′-CAGCCCTGCTTTTCTCTCTG-3′ and 5′-CAGTCTGCCAATGGTCTCAA-3′. Positions of PCR fragments correspond to NCBI Mouse genome Build 38 (mm10).

Statistical analysis

Two-tailed Student's t-tests were applied for statistical analysis. For all graphs, error bars represent standard deviations. A P-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

Supplementary Material is available at HMG online.

Conflict of Interest statement. None declared.

FUNDING

This work was supported by the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, National Institutes of Health (DE020065, DE012711 to Y.C.).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are grateful to Drs Julie Mayo and Bridget Samuels for critical reading of the manuscript, Dr Harold Moses for Tgfbr2fl/fl mice, Dr Henry M. Sucov for investigation and discussion of the heart phenotype, Dr Harold Slavkin for discussion and Pablo Bringas Jr and Jingjing Zhou for technical assistance. We thank the Flow Cytometry core facilities and Center for Electron Microscopy and Microanalysis of USC, and the Microarray core of Children's Hospital Los Angeles (CHLA) for technical assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mossey P.A., Little J., Munger R.G., Dixon M.J., Shaw W.C. Cleft lip and palate. Lancet. 2009;374:1773–1785. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60695-4. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60695-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hrubec T.C., Prater M.R., Toops K.A., Holladay S.D. Reduction in diabetes-induced craniofacial defects by maternal immune stimulation. Birth Defects Res. B Dev. Reprod. Toxicol. 2006;77:1–9. doi: 10.1002/bdrb.20062. doi:10.1002/bdrb.20062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Al Ghafli M.H., Padmanabhan R., Kataya H.H., Berg B. Effects of alpha-lipoic acid supplementation on maternal diabetes-induced growth retardation and congenital anomalies in rat fetuses. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2004;261:123–135. doi: 10.1023/b:mcbi.0000028747.92084.42. doi:10.1023/B:MCBI.0000028747.92084.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moore L.L., Singer M.R., Bradlee M.L., Rothman K.J., Milunsky A. A prospective study of the risk of congenital defects associated with maternal obesity and diabetes mellitus. Epidemiology. 2000;11:689–694. doi: 10.1097/00001648-200011000-00013. doi:10.1097/00001648-200011000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ewart-Toland A., Yankowitz J., Winder A., Imagire R., Cox V.A., Aylsworth A.S., Golabi M. Oculoauriculovertebral abnormalities in children of diabetic mothers. Am. J. Med. Genet. 2000;90:303–309. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1096-8628(20000214)90:4<303::AID-AJMG8>3.0.CO;2-Q. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bush J.O., Jiang R. Palatogenesis: morphogenetic and molecular mechanisms of secondary palate development. Development. 2012;139:231–243. doi: 10.1242/dev.067082. doi:10.1242/dev.067082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meng L., Bian Z., Torensma R., Von den Hoff J.W. Biological mechanisms in palatogenesis and cleft palate. J. Dent. Res. 2009;88:22–33. doi: 10.1177/0022034508327868. doi:10.1177/0022034508327868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Iwata J., Parada C., Chai Y. The mechanism of TGF-beta signaling during palate development. Oral Dis. 2011;17:733–744. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.2011.01806.x. doi:10.1111/j.1601-0825.2011.01806.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chai Y., Jiang X., Ito Y., Bringas P., Jr, Han J., Rowitch D.H., Soriano P., McMahon A.P., Sucov H.M. Fate of the mammalian cranial neural crest during tooth and mandibular morphogenesis. Development. 2000;127:1671–1679. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.8.1671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mizuguchi T., Collod-Beroud G., Akiyama T., Abifadel M., Harada N., Morisaki T., Allard D., Varret M., Claustres M., Morisaki H., et al. Heterozygous TGFBR2 mutations in Marfan syndrome. Nat. Genet. 2004;36:855–860. doi: 10.1038/ng1392. doi:10.1038/ng1392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Loeys B.L., Chen J., Neptune E.R., Judge D.P., Podowski M., Holm T., Meyers J., Leitch C.C., Katsanis N., Sharifi N., et al. A syndrome of altered cardiovascular, craniofacial, neurocognitive and skeletal development caused by mutations in TGFBR1 or TGFBR2. Nat. Genet. 2005;37:275–281. doi: 10.1038/ng1511. doi:10.1038/ng1511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Loeys B.L., Schwarze U., Holm T., Callewaert B.L., Thomas G.H., Pannu H., De Backer J.F., Oswald G.L., Symoens S., Manouvrier S., et al. Aneurysm syndromes caused by mutations in the TGF-beta receptor. N. Engl. J. Med. 2006;355:788–798. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa055695. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa055695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Iwata J., Hacia J.G., Suzuki A., Sanchez-Lara P.A., Urata M., Chai Y. Modulation of noncanonical TGF-beta signaling prevents cleft palate in Tgfbr2 mutant mice. J. Clin. Invest. 2012;122:873–885. doi: 10.1172/JCI61498. doi:10.1172/JCI61498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Burgering B.M., Coffer P.J. Protein kinase B (c-Akt) in phosphatidylinositol-3-OH kinase signal transduction. Nature. 1995;376:599–602. doi: 10.1038/376599a0. doi:10.1038/376599a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Planchon S.M., Waite K.A., Eng C. The nuclear affairs of PTEN. J. Cell Sci. 2008;121:249–253. doi: 10.1242/jcs.022459. doi:10.1242/jcs.022459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brasaemle D.L. Thematic review series: adipocyte biology. The perilipin family of structural lipid droplet proteins: stabilization of lipid droplets and control of lipolysis. J. Lipid Res. 2007;48:2547–2559. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R700014-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stefanovich V., Gianelly A. Preliminary studies of the lipids of normal and cleft palates of the rat. J. Dent. Res. 1971;50:1360. doi: 10.1177/00220345710500055201. doi:10.1177/00220345710500055201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pratt R.M., Martin G.R. Epithelial cell death and cyclic AMP increase during palatal development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1975;72:874–877. doi: 10.1073/pnas.72.3.874. doi:10.1073/pnas.72.3.874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reddy C.S. Alterations in protein kinase A signalling and cleft palate: a review. Hum. Exp. Toxicol. 2005;24:235–242. doi: 10.1191/0960327105ht514oa. doi:10.1191/0960327105ht514oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bartz R., Zehmer J.K., Zhu M., Chen Y., Serrero G., Zhao Y., Liu P. Dynamic activity of lipid droplets: protein phosphorylation and GTP-mediated protein translocation. J. Proteome Res. 2007;6:3256–3265. doi: 10.1021/pr070158j. doi:10.1021/pr070158j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhao M., New L., Kravchenko V.V., Kato Y., Gram H., di Padova F., Olson E.N., Ulevitch R.J., Han J. Regulation of the MEF2 family of transcription factors by p38. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1999;19:21–30. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.1.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang S.H., Galanis A., Sharrocks A.D. Targeting of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinases to MEF2 transcription factors. Mol .Cell. Biol. 1999;19:4028–4038. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.6.4028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chang C.I., Xu B.E., Akella R., Cobb M.H., Goldsmith E.J. Crystal structures of MAP kinase p38 complexed to the docking sites on its nuclear substrate MEF2A and activator MKK3b. Mol. Cell. 2002;9:1241–1249. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00525-7. doi:10.1016/S1097-2765(02)00525-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.de Angelis L., Zhao J., Andreucci J.J., Olson E.N., Cossu G., McDermott J.C. Regulation of vertebrate myotome development by the p38 MAP kinase-MEF2 signaling pathway. Dev. Biol. 2005;283:171–179. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.04.009. doi:10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cante-Barrett K., Pieters R., Meijerink J.P. Myocyte enhancer factor 2C in hematopoiesis and leukemia. Oncogene. 2013 doi: 10.1038/onc.2013.56. doi:10.1038/onc.2013.56,1-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ito Y., Yeo J.Y., Chytil A., Han J., Bringas P., Jr, Nakajima A., Shuler C.F., Moses H.L., Chai Y. Conditional inactivation of Tgfbr2 in cranial neural crest causes cleft palate and calvaria defects. Development. 2003;130:5269–5280. doi: 10.1242/dev.00708. doi:10.1242/dev.00708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Iwata J., Tung L., Urata M., Hacia J.G., Pelikan R., Suzuki A., Ramenzoni L., Chaudhry O., Parada C., Sanchez-Lara P.A., et al. Fibroblast growth factor 9 (FGF9)-pituitary homeobox 2 (PITX2) pathway mediates transforming growth factor beta (TGFbeta) signaling to regulate cell proliferation in palatal mesenchyme during mouse palatogenesis. J. Biol. Chem. 2012;287:2353–2363. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.280974. doi:10.1074/jbc.M111.280974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gritli-Linde A., Hallberg K., Harfe B.D., Reyahi A., Kannius-Janson M., Nilsson J., Cobourne M.T., Sharpe P.T., McMahon A.P., Linde A. Abnormal hair development and apparent follicular transformation to mammary gland in the absence of hedgehog signaling. Dev. Cell. 2007;12:99–112. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.12.006. doi:10.1016/j.devcel.2006.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rice R., Spencer-Dene B., Connor E.C., Gritli-Linde A., McMahon A.P., Dickson C., Thesleff I., Rice D.P. Disruption of Fgf10/Fgfr2b-coordinated epithelial-mesenchymal interactions causes cleft palate. J. Clin. Invest. 2004;113:1692–1700. doi: 10.1172/JCI20384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lan Y., Jiang R. Sonic hedgehog signaling regulates reciprocal epithelial-mesenchymal interactions controlling palatal outgrowth. Development. 2009;136:1387–1396. doi: 10.1242/dev.028167. doi:10.1242/dev.028167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Engelking L.J., Evers B.M., Richardson J.A., Goldstein J.L., Brown M.S., Liang G. Severe facial clefting in Insig-deficient mouse embryos caused by sterol accumulation and reversed by lovastatin. J. Clin. Invest. 2006;116:2356–2365. doi: 10.1172/JCI28988. doi:10.1172/JCI28988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Porter F.D. Cholesterol precursors and facial clefting. J. Clin. Invest. 2006;116:2322–2325. doi: 10.1172/JCI29872. doi:10.1172/JCI29872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wetmore C. Sonic hedgehog in normal and neoplastic proliferation: insight gained from human tumors and animal models. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2003;13:34–42. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(03)00002-9. doi:10.1016/S0959-437X(03)00002-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kurtz T.W. Beyond the classic angiotensin-receptor-blocker profile. Nat. Clin. Pract. Cardiovasc. Med. 2008;5(Suppl. 1):S19–S26. doi: 10.1038/ncpcardio0805. doi:10.1038/ncpcardio0805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rizos C.V., Elisaf M.S., Liberopoulos E.N. Are the pleiotropic effects of telmisartan clinically relevant? Curr. Pharm. Des. 2009;15:2815–2832. doi: 10.2174/138161209788923859. doi:10.2174/138161209788923859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fitzky B.U., Moebius F.F., Asaoka H., Waage-Baudet H., Xu L., Xu G., Maeda N., Kluckman K., Hiller S., Yu H., et al. 7-Dehydrocholesterol-dependent proteolysis of HMG-CoA reductase suppresses sterol biosynthesis in a mouse model of Smith-Lemli-Opitz/RSH syndrome. J. Clin. Invest. 2001;108:905–915. doi: 10.1172/JCI12103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Krakowiak P.A., Wassif C.A., Kratz L., Cozma D., Kovarova M., Harris G., Grinberg A., Yang Y., Hunter A.G., Tsokos M., et al. Lathosterolosis: an inborn error of human and murine cholesterol synthesis due to lathosterol 5-desaturase deficiency. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2003;12:1631–1641. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg172. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddg172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Iwata J., Hosokawa R., Sanchez-Lara P.A., Urata M., Slavkin H., Chai Y. Transforming growth factor-beta regulates basal transcriptional regulatory machinery to control cell proliferation and differentiation in cranial neural crest-derived osteoprogenitor cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:4975–4982. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.035105. doi:10.1074/jbc.M109.035105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Iwata J., Ezaki J., Komatsu M., Yokota S., Ueno T., Tanida I., Chiba T., Tanaka K., Kominami E. Excess peroxisomes are degraded by autophagic machinery in mammals. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:4035–4041. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M512283200. doi:10.1074/jbc.M512283200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Smyth G.K. Linear models and empirical bayes methods for assessing differential expression in microarray experiments. Stat. Appl. Genet. Mol. Biol. 2004;3:Article3. doi: 10.2202/1544-6115.1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pounds S., Cheng C. Improving false discovery rate estimation. Bioinformatics. 2004;20:1737–1745. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth160. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/bth160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.