Abstract

Sphingosine 1-phosphate (S1P)/S1P receptor 1 (S1P1) signaling plays an important role in synovial cell proliferation and inflammatory gene expression by rheumatoid arthritis (RA) synoviocytes. The purpose of this study is to clarify the role of S1P/S1P1 signaling in the expression of receptor activator of NF-κB ligand (RANKL) in RA synoviocytes and CD4+ T cells. We demonstrated MH7A cells, a human RA synovial cell line, and CD4+ T cells expressed S1P1 and RANKL. Surprisingly, S1P increased RANKL expression in MH7A cells and CD4+ T cells in a dose-dependent manner. Moreover, S1P enhanced RANKL expression induced by stimulation with TNF-α in MH7A cells and CD4+ T cells. These effects of S1P in MH7A cells were inhibited by pretreatment with PTX, a specific Gi/Go inhibitor. These findings suggest that S1P/S1P1 signaling may play an important role in RANKL expression by MH7A cells and CD4+ T cells. S1P/S1P1 signaling of RA synoviocytes is closely connected with synovial hyperplasia, inflammation, and RANKL-induced osteoclastogenesis in RA. Thus, regulation of S1P/S1P1 signaling may become a novel therapeutic target for RA.

Keywords: Sphingosine 1-phosphate, RANKL, Rheumatoid arthritis

1. Introduction

Sphingosine 1-phosphate (S1P) is a biologically active sphingolipid that is generated by phosphorylation of sphingosine by sphingosine kinase (SphK). S1P mediates a wide variety of cellular responses via interactions with members of the endothelial differentiation gene (Edg) family of G protein-coupled receptors expressed at the plasma membrane [1]. S1P receptors, namely S1P1/EDG-1, S1P2/EDG-5, S1P3/EDG-3, S1P4/EDG-6, and S1P5/EDG-8, are high-affinity receptors of S1P [2]. S1P elicits diverse cellular responses via S1P receptor signaling such as cell proliferation, differentiation, and migration. Importantly, S1P has been implicated as an important mediator of pathophysiological processes, including inflammation, angiogenesis, and autoimmunity [3–5].

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a chronic, destructive, autoimmune joint disease characterized by histological hallmarks such as hyperplasia of the synovial lining cells, infiltration of mononuclear cells especially synovial T cells and macrophages, angiogenesis, and osteoclastic bone destruction. The inflammation of RA is closely related to cyclooxygenase (COX)-2 induced-prostaglandin (PG) E2 production by synoviocytes [6]. Moreover, PGE2 plays major roles in angiogenesis through expression of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) in the rheumatoid synovium [7] and in osteoclastogenesis through the expression of receptor activator of nuclear factor-κB ligand (RANKL) in RA synoviocytes and infiltrated T cells [8].

RANKL, a tumor necrosis factor (TNF) family member, plays an essential role in the commitment of osteoclast precursors to osteoclast differentiation [9]. RANKL is also important for activation and survival of differentiated osteoclasts. Cell surface molecules for osteoclast differentiation are found to be dependent on the interaction between RANK present on osteoclast precursors and RANKL expressed on other cells such as synovial cells, CD4+ T cells and osteoblasts in RA [10]. Recently, it was reported that S1P regulated osteoclast differentiation, osteoclast-osteoblast coupling [11], and controlled the migratory behavior of osteoclast precursors [12], thereby regulating bone mineral homeostasis.

We previously reported that S1P1 was more strongly expressed in RA synovium compared with osteoarthritis (OA) synovium and that absolute levels of S1P in synovial fluid were higher in RA patients than in OA patients [5]. Moreover, S1P/S1P1 signaling played an important role for synoviocyte proliferation and COX-2-induced PGE2 production by RA synoviocytes. These findings suggest that S1P/S1P1 signaling is closely connected with synovial hyperplasia, inflammation and angiogenesis in RA. However, the relationship between S1P/S1P1 signaling and the induction of RANKL expression in RA synoviocytes and CD4+ T cells remains unclear.

The goal of this study was to clarify the role of S1P/S1P1 signaling for RANKL expression in RA synoviocytes and CD4+ T cells. We demonstrated that S1P/S1P1 signaling enhanced RANKL expression of RA synoviocytes and CD4+ T cells. In addition, S1P significantly enhanced TNF-α induced RANKL expression by RA synoviocytes and CD4+ T cells. We conclude that S1P/S1P1 signaling may play an important role in RANKL induced-osteoclastogenesis of RA. Thus, the regulation of S1P/S1P1 signaling may become a novel therapeutic target in RA.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Cell line and cell culture

MH7A synovial cells isolated from intra-articular soft tissues of the knee joints of RA patients were obtained from Riken Cell Bank (Saitama, Japan). MH7A is a cell line established by transfection with the SV40 T antigen [13]. MH7A cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) containing 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Whittaker, Walkersville, MD), 100 units/ml of penicillin and 100 μg/ml of streptomycin (Invitrogen, San Diego, CA) at 37 °C in an atmosphere of 5% CO2 in air.

2.2. CD4+ T cell isolation

CD4+ T cells were isolated from peripheral blood from 5 healthy volunteers as described previously [14]. Briefly, mononuclear cells were isolated from peripheral blood by Ficoll–Paque density gradient centrifugation. Mononuclear cells (1 × 107) were labeled with biotin-conjugated anti-CD4 antibody and magnetic anti-biotin microbeads according to the manufacturer’s protocol (CD4+ T cell isolation kit II) (Miltenyi Biotec GmbH, Bergisch Gladback, Germany). CD4+ T cells were separated using the mini-MACS separator (Miltenyi Biotec GmbH). Purity of the CD4+ T cell population was >95%.

2.3. RNA preparation and analysis of S1P1 and RANKL messenger RNA (mRNA)

Total RNA from MH7A cells was prepared using Isogen (Nippon Gene, Toyama, Japan) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Reverse transcription (RT) and complementary DNA (cDNA) amplification were performed with the TaKaRa RNA polymerase chain reaction (PCR) kit (Takara Shuzo, Otsu, Japan) [15]. The primers used for the RT-PCR analysis have been reported previously [16,17]. Forward and reverse primers were as follows: Human S1P1 (429-bp product) sense 5′-TATCAGCGCGGACAAGGAGAACAG-3′, antisense 5′-ATAGGCAGGCCACCCAGGATGAG-3′; human RANKL (486-bp product) sense 5′-GCCAGTGGGAGATGTTAG-3′, antisense 5′-TTAGC TGCAAGTTTTCCC-3′; and GAPDH (246-bp product) sense 5′-GATGA CATCAAGAAGGTGGTGAA-3′, antisense 5′-GTCTTACTCCTTGGAGGC CAT-GT-3′. The conditions for thermal cycling were as follows: 30 cycles of 94 °C for 1 min, 62 °C for 1 min, and 72 °C for 1 min. PCR products were electrophoresed on a 2% agarose gel and visualized by ethidium bromide staining.

2.4. Western blot analysis of RANKL

MH7A cells or CD4+ T cells (1 × 107) were lysed in RIPA lysis buffer (Santa Cruz) and protein content was determined using Bio-Rad protein assay reagent (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) with bovine serum albumin as a standard. Each sample (20 μg) was resolved on 10% polyacrylamide gels under denaturing conditions and then transferred to 0.45 μm nitrocellulose membranes. After blocking overnight at 4 °C with 5% non-fat milk in Tris-buffered saline-0.01% Tween 20 (Santa Cruz), membranes were incubated with primary antibody against human RANKL (MAB626) (R&D Systems) for overnight at 4 °C. After washing the membranes with Tris buffered saline −0.05% Tween 20 (washing buffer), HRP-conjugated secondary antibody (1:2000 dilution in PBS) (Santa Cruz) was added, followed by incubation for 45 min. After further washing, the color was developed with luminol reagent (Santa Cruz) and HRP activity of blots was analyzed using a LAS1000 imager (Fuji film, Tokyo, Japan).

2.5. RANKL Immunostaining

RANKL immunostaining in MH7A cells was performed with the Vectastain ABC kit (Vector) using primary antibody against human RANKL (MAB626) (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) or normal mouse IgG2b (Santa Cruz) [18]. RANKL immunostaining was performed by peroxidase labeling techniques. The color of the sections was developed by the peroxidase substrate kit (Santa Cruz). Finally, the sections were counterstained with Mayer’s hematoxylin (Wako, Osaka, Japan). Positive staining of RANKL was indicated by brownish deposits. Control staining with normal mouse IgG2b was negative in all cases.

2.6. Effect of S1P alone or in combination with TNF-α on RANKL mRNA expression in MH7A cells

MH7A cells were cultured with S1P (0–0.5 μM) (Sigma) or TNF-α (100 ng/ml) (Sigma) in flat-bottomed 24-well microplates at a concentration of 1 × 106 cells/ml in RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% (v/v) FBS. After 6–24 h, RANKL mRNA in MH7A cells was determined by RT-PCR. Moreover, MH7A cells were incubated with both various concentrations (0–0.5 μM) of S1P and 100 ng/ml of TNF-α. After 6 h incubation, RANKL mRNA of MH7A cells was examined by RT-PCR. RANKL mRNA expression levels were determined by normalizing expression with respect to GAPDH mRNA expression levels.

2.7. Effect of pertussis toxin (PTX) on S1P-induced RANKL mRNA expression in MH7A cells

To examine whether the effect of S1P was sensitive or insensitive to pertussis toxin (PTX), specific Gi/Go inhibitor, MH7A cells were pre-incubated for 24 h in the presence or absence of 100 ng/ml PTX (Sigma). After rigorous washing, cells were stimulated with S1P (0–0.1 μM). After 24 h incubation, RANKL mRNA of MH7A cells was determined by RT-PCR.

2.8. Effect of S1P alone or in combination with TNF-α on RANKL mRNA expression of CD4+ T cells

CD4+ T cells were cultured with S1P (0–0.5 μM) or TNF-α (100 ng/ml) in flat-bottomed 24-well microplates at a concentration of 1 × 106 cells/ml in RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% (v/v) FBS. After 6 h, RANKL mRNA in CD4+ T cells was determined by RT-PCR. Moreover, CD4+ T cells were stimulated with both 0.5 μM S1P and 100 ng/ml TNF-α. After 6 h incubation, RANKL mRNA levels were measured by RT-PCR. RANKL mRNA expression levels were determined by normalizing expression with respect to GAPDH mRNA expression levels.

2.9. Statistical analysis

Results are expressed as the mean ± the standard error of the mean (SEM) from three independent experiments. The significance of the difference between the experimental results and control values was determined by a Student’s t-test. P- values less than 0.05 were considered significant.

3. Results

3.1. S1P1 and RANKL expression in MH7A cells and CD4+ T cells

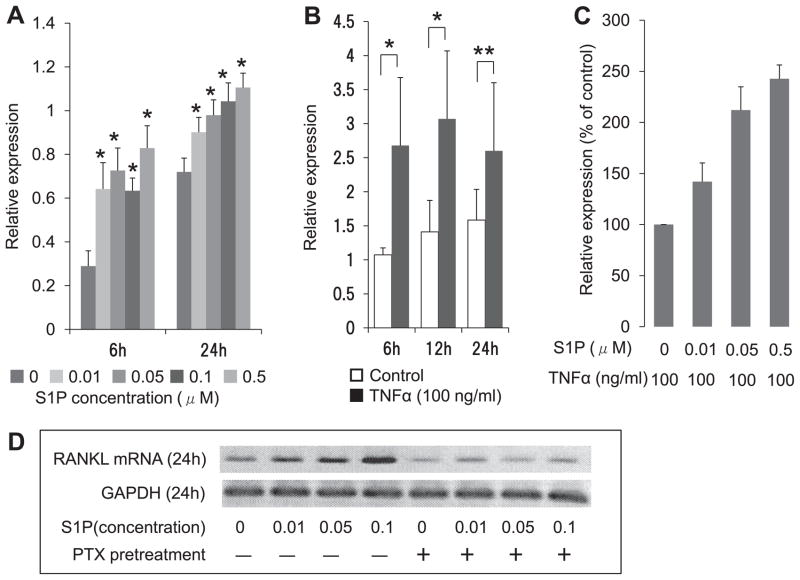

We previously showed that S1P1 is expressed in fibroblast like synoviocytes (FLS) from patients with RA, MH7A cells and human CD4+ T cells [5,14]. In the present study, expression of S1P1 and RANKL transcripts in MH7A cells and CD4+ T cells was determined using RT-PCR analysis. MH7A cells and CD4+ T cells expressed both S1P1 and RANKL mRNA (Fig. 1A). Next, to investigate whether MH7A cells and CD4+ T cells expressed RANKL protein, we performed western blot analysis of RANKL. RANKL proteins were both detected in MH7A cells and CD4+ T cells (Fig. 1B). We also detected RANKL expression of MH7A cells by immunohistochemical analysis (Fig. 1C). These results indicate that MH7A cells and CD4+ T cells express both S1P1 and RANKL.

Fig. 1.

S1P1 and RANKL expression in MH7A cells and CD4+ T cells. (A) RT-PCR analysis of S1P1 and RANKL mRNA expression. Primers for S1P1 generated the expected 429-nucleotide band after 30 cycles of PCR. Primers for RANKL generated the expected 486-nucleotide band after 30 cycles of PCR. Primers for GAPDH generated the expected 246-bp band in all subjects. Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) were used as a positive control for S1P1 expression. (B) detection of RANKL protein by western blot analysis. (C) RANKL immunohistochemical staining of MH7A cells. Positive staining is indicated by brownish deposits and background appeared purple. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

3.2. S1P increases RANKL mRNA expression in MH7A cells via a Gi/Go-dependent pathway

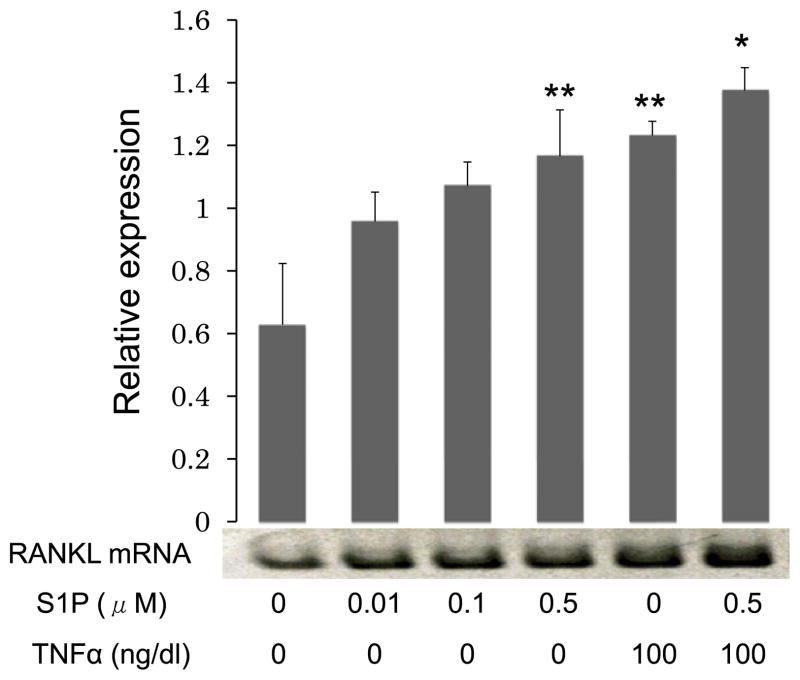

To investigate the role of S1P on RANKL mRNA expression by MH7A cells, we performed RT-PCR for RANKL mRNA in MH7A cells stimulated with S1P at various concentrations (0–0.5 μM). RANKL mRNA expression levels were determined by normalization to GAPDH mRNA expression levels. Data represent the mean ± SEM from three independent experiments. Interestingly, S1P increased RANKL mRNA expression by MH7A cells in a concentration-dependent manner. The maximal increasing effect (2.5- fold increase) was observed with a S1P concentration of 0.5 μM for 6 h of culture (Fig. 2A). Previously, it was demonstrated that TNF-α enhanced RANKL expression of RA synoviocytes [19]. Therefore, we investigated the effect of TNF-α on RANKL mRNA expression by MH7A cells. Treatment with TNF-α (100 ng/ml) for 6–24 h enhanced the expression of RANKL mRNA by MH7A cells. The maximal TNF-α-enhancing effect on RANKL mRNA was a 2.5-fold increase and was observed after 6 h of culture (Fig. 2B). Next, we investigated the effect of S1P on TNF-α-induced RANKL mRNA expression by MH7A cells. When TNF-α (100 ng/ml)-treated MH7A cells were stimulated with S1P at various concentrations (0–0.5 μM) for 6 h, RANKL mRNA levels were enhanced in a concentration-dependent manner. The maximal enhancing effect (2.5-fold increase) was observed at a S1P concentration of 0.5 μM (Fig. 2C). These results indicate that S1P is an important factor for the induction of RANKL mRNA expression by MH7A cells.

Fig. 2.

S1P increases RANKL mRNA expression in MH7A cells via a Gi/G0-dependent pathway: (A) MH7A cells were treated with S1P (0–0.5 μM) for 6–24 h and RT-PCR for RANKL mRNA expression in MH7A cells was performed. (B) MH7A cells were treated with TNF-α (100 ng/ml) for 6–24 h and RT-PCR for RANKL mRNA expression in MH7A cells was performed. (C) TNF-α (100 ng/ml)-treated MH7A cells were stimulated with S1P (0–0.5 μM) for 6 h and RT-PCR for RANKL mRNA expression in MH7A cells was performed. RANKL mRNA expression levels were determined by normalizing expression with respect to GAPDH mRNA expression levels. Data represent mean ± SEM from three independent experiments. *P < 0.01; **P < 0.05. (D) Effect of pertussis toxin (PTX) on S1P-enduced RANKL mRNA expression in MH7A cells. MH7A cells were pre-incubated with PTX (100 ng/ml) for 24 h. After rigorous washing, the cells were stimulated with S1P (0–0.1 μM). After 24 h, RT-PCR for RANKL mRNA expression in MH7A cells was performed.

It has been reported that S1P1 couples to only G proteins of the Gi/G0 family [20]. Therefore, we investigated the role of PTX-sensitive G proteins on S1P-induced RANKL expression by MH7A cells. In result, pre-treatment with PTX inhibited S1P-induced RANKL mRNA expression by MH7A cells (Fig. 2D). This result indicates that S1P induced RANKL mRNA expression in MH7A cells via a Gi/G0-dependent pathway.

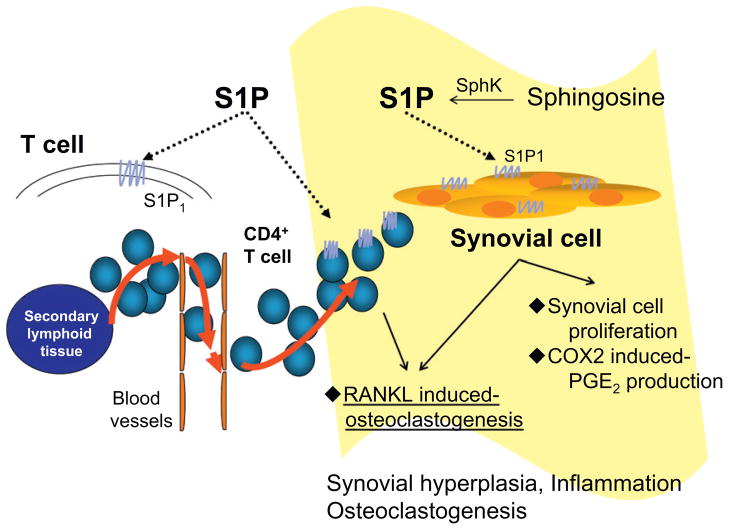

3.3. S1P increased RANKL mRNA expression in CD4+ T cells

We examined the effect of S1P on RANKL mRNA expression by CD4+ T cells using RT-PCR analysis. Treatment with S1P (0–0.5 μM) enhanced RANKL mRNA expression in a dose-dependent manner with a 2-fold maximal increase in RANKL mRNA expression compared with control cells evident at a S1P concentration of 0.5 μM. Interestingly, this stimulatory effect of S1P (0.5 μM) on RANKL mRNA expression was similar to the effect of stimulation with TNF-α (100 ng/ml). Moreover, S1P (0.5 μM) also enhanced TNF-α-induced RANKL mRNA expression of CD4+ T cells (Fig. 3). These results indicate that S1P is an important factor for the induction of RANKL mRNA expression in CD4+ T cells as well as MH7A cells.

Fig. 3.

S1P increases RANKL mRNA expression in CD4+ T cells: CD4+ T cells were treated with S1P (0–0.5 μM) or TNF-α (100 ng/ml) alone or both 0.5 μM S1P and 100 ng/ml TNF-α for 6 h and RT-PCR for the expression of RANKL mRNA in CD4+ T cells was performed. RANKL mRNA expression levels were determined by normalizing expression with respect to GAPDH mRNA expression levels. Data represent mean ± SEM from three independent experiments. *P < 0.01; **P < 0.05.

4. Discussion

Several novel findings were demonstrated in this study: (1) MH7A cells and CD4+ T cells both express S1P1 and RANKL. (2) S1P induced RANKL expression by MH7A cells and CD4+ T cells and enhanced TNF-α-induced RANKL expression by these cells. (3) PTX partially blocked S1P-induced RANKL expression by MH7A cells. These results indicate that S1P/S1P1 signaling plays an important role in modulating RANKL expression by MH7A cells and CD4+ T cells.

S1P has been implicated as an important mediator of pathophysiological processes, such as inflammation, angiogenesis, autoimmunity, and osteoclastogenesis [3,11,12]. We previously reported that S1P signaling via S1P1 played an important role in cell proliferation and inflammatory cytokine-induced COX-2 expression and PGE2 production by RA synoviocytes [5]. In RA, RA synoviocytes, CD4+ T cells, and osteoblasts promoted osteoclastogenesis through the expression of RANKL. In this study, we showed that S1P/S1P1 signaling played an important role for RANKL expression of RA synoviocytes and CD4+ T cells. Previous reports have demonstrated that S1P stimulates the induction of RANKL via COX-2 and PGE2 regulation by mouse calvarial osteoblasts [11] and that S1P induces osteoblast precursor recruitment and promotes mature cell survival [21]. Recently, Ishii et al. demonstrated that S1P promoted chemotaxis of bone marrow-resident monocytes including osteoclast precursors and that FTY720 relieved ovariectomy-induced bone loss by reducing osteoclast deposition onto bone surfaces [12]. Taken together, these reports suggest that S1P/S1P1 signaling may be involved in osteoclastic bone destruction via multiple mechanisms including the induction of RANKL expression in various cells such as RA synoviocytes, CD4+ T cells, and osteoblasts, and via migratory behavior of osteoclast precursors and osteoclasts.

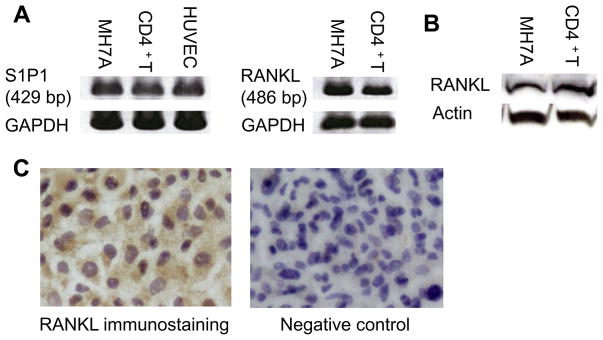

A schematic diagram of the role of S1P/S1P1 signaling in the pathogenesis of RA is shown in Fig. 4. S1P/S1P1 signaling is involved in synovial inflammation through migration of CD4+ T cells from secondary lymphoid tissues to RA synovium. FTY720 (fingolimod), a novel immunomodulatory agent, has been shown to be a useful agent for the treatment of multiple sclerosis. FTY720-induced internalization of the S1P1 receptor, which renders autoreactive immune cells unresponsive to S1P and thereby reduce autoimmune inflammation in the central nervous system [22]. Recent studies demonstrated that immunomodulatory effects of FTY720 were primarily exerted by sequestration of lymphocytes within the thymus and secondary lymphoid organs, thereby denying them the ability to recirculate to peripheral sites of inflammation [23,24]. We reported that FTY720 could inhibit arthritis via multiple mechanisms including sequestration of autoimmune CD4+ T cells in the thymus, enhancement of Th2 immune responses, and inhibition of PGE2 production by synoviocytes in SKG mice [25]. Moreover, a previous study has also demonstrated the efficacy of FTY720 in a rat collagen and adjuvant-induced arthritis model [26].

Fig. 4.

The role of S1P/S1P1 signaling in RA. S1P/S1P1 signaling is involved in synovial inflammation through migration of CD4+ T cells from secondary lymphoid organs as well as via its direct effects on synovial cells such as proliferation and COX2-induced PGE2 production. S1P/S1P1 signaling also induces RANKL expression in synovial cells and CD4+ T cells, thereby inducing osteoclast differentiation.

Elevated levels of inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α and interleukin-1β (IL-1β) characterizes RA synovial inflammation [27]. A previous report has demonstrated that these inflammatory cytokines enhanced the expression of SphK1 of various cells [28,29]. We also found that TNF-α stimulation enhanced SphK1 mRNA expression in MH7A cells in a dose and time-dependent manner (data not shown) and that synovial fluids of RA patients exhibited higher levels of S1P concentrations than those of OA patients. In addition, S1P1 was strongly expressed in RA synovial tissues compared with OA synovial tissues [5]. Taken together, these results indicate that S1P/S1P1 signaling may be involved in RA synovial cell functions. We have already demonstrated that S1P/S1P1 signaling enhanced synovial cell proliferation and COX-2-induced PGE2 production by RA synoviocytes [5]. Thus, S1P/S1P1 signaling may induce synovial hyperplasia and inflammation in RA. In fact, It was also reported that treatment with SphK1 siRNA significantly suppressed articular inflammation and joint destruction, reduced disease severity and downregulated serum levels of S1P, IL-6, TNF-α, and IFN-γ in a collagen-induced arthritis model [30]. In this study, we demonstrated that S1P/S1P1 signaling might enhance osteoclastogenesis via RANKL expression in RA synoviocytes and CD4+ T cells. Taken together, these results indicate that inhibition of S1P/S1P1 signaling is a potential therapy for RA.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated that S1P enhanced RANKL expression in RA synoviocytes and CD4+ T cells. S1P/S1P1 signaling may play an important role in the pathogenesis of RA including synovial cell proliferation, inflammation, and osteoclastogenesis via RANKL expression. Regulation of S1P/S1P1 signaling may be a novel therapeutic target in RA.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Grant-in-Aid for Young Scientists (B) (19790699) from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT) and Grant-in-Aid for Researchers, Hyogo College of Medicine.

References

- 1.Sanchez T, Hla T. Structural and functional characteristics of S1P receptors. J Cell Biochem. 2004;92:913–922. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hla T. Signaling and biological actions of sphingosine 1-phosphate. Pharmacol Res. 2003;47:401–407. doi: 10.1016/s1043-6618(03)00046-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Spiegel S, Milstien S. Sphingosine-1-phosphate: an enigmatic signalling lipid. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2003;4:397–407. doi: 10.1038/nrm1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hla T. Physiological and pathological actions of sphingosine 1-phosphate. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2004;15:513–520. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2004.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kitano M, Hla T, Sekiguchi M, Kawahito Y, Yoshimura R, Miyazawa K, Iwasaki T, Sano H, Saba JD, Tam YY. Sphingosine 1-phosphate/sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor 1 signaling in rheumatoid synovium: regulation of synovial proliferation and inflammatory gene expression. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:742–753. doi: 10.1002/art.21668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sano H, Hla T, Maier JA, Crofford LJ, Case JP, Maciag T, Wilder RL. In vitro cyclooxygenase expression in synovial tissues of patients with rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis and rats with adjuvant and streptococcal cell wall arthritis. J Clin Invest. 1992;89:97–108. doi: 10.1172/JCI115591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ben-Av P, Crofford LJ, Wilder RL, Hla T. Induction of vascular endothelial growth factor expression in synovial fibroblasts by prostaglandin E and interleukin-1: a potential mechanism for inflammatory angiogenesis. FEBS Lett. 1995;372:83–87. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)00956-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kotake S, Udagawa N, Takahashi N, Matsuzaki K, Itoh K, Ishiyama S, Saito S, Inoue K, Kamatani N, Gillespie MT, Martin TJ, Suda T. IL-17 in synovial fluids from patients with rheumatoid arthritis is a potent stimulator of osteoclastogenesis. J Clin Invest. 1999;103:1345–1352. doi: 10.1172/JCI5703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Takahashi N, Udagawa N, Suda T. A new member of tumor necrosis factor ligand family, ODF/OPGL/TRANCE/RANKL, regulates osteoclast differentiation and function. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999;256:449–455. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.0252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Udagawa N, Kotake S, Kamatani N, Takahashi N, Suda T. The molecular mechanism of osteoclastogenesis in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res. 2002;4:281–289. doi: 10.1186/ar431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ryu J, Kim HJ, Chang EJ, Huang H, Banno Y, Kim HH. Sphingosine 1-phosphate as a regulator of osteoclast differentiation and osteoclast-osteoblast coupling. EMBO J. 2006;25:5840–5851. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ishii M, Egen JG, Klauschen F, Meier-Schellersheim M, Saeki Y, Vacher J, Proia RL, Germain RN. Sphingosine-1-phosphate mobilizes osteoclast precursors and regulates bone homeostasis. Nature. 2009;26:524–528. doi: 10.1038/nature07713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miyazawa K, Mori A, Okudaira H. Establishment and characterization of a novel human rheumatoid fibroblast-like synoviocyte line, MH7A, immortalized with SV40 T antigen. J Biochem. 1998;124:1153–1162. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a022233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sekiguchi M, Iwasaki T, Kitano M, Kuno H, Hashimoto N, Kawahito Y, Azuma M, Hla T, Sano H. Role of sphingosine 1-phosphate in the pathogenesis of Sjogren’s syndrome. J Immunol. 2008;180:1921–1928. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.3.1921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Andre-Garnier E, Robillard N, Costa-Mattioli M, Besse B, Billaudel S, Imbert-Marcille BM. A one-step RT-PCR and a flow cytometry method as two specific tools for direct evaluation of human herpesvirus-6 replication. J Virol Methods. 2003;108:213–222. doi: 10.1016/s0166-0934(03)00037-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim JI, Jo EJ, Lee HY, Cha MS, Min JK, Choi CH, Lee YM, Choi YA, Baek SH, Ryu SH, Lee KS, Kwak JY, Bae YS. Sphingosine 1-phosphate in amniotic fluid modulates cyclooxygenase-2 expression in human amnion-derived WISH cells. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:31731–31736. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300625200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee CK, Lee EY, Chung SM, Mun SH, Yoo B, Moon HB. Effects of disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs and anti-inflammatory cytokines on human osteoclastogenesis through interaction with receptor activator of nuclear factor kappaB, osteoprotegerin, and receptor activator of nuclear factor kappaB ligand. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50:3831–3843. doi: 10.1002/art.20637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Catrina AI, af Klint E, Ernestam S, Catrina SB, Makrygiannakis D, Botusan IR, Klareskog L, Ulfgren AK. Anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy increases synovial osteoprotegerin expression in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:76–81. doi: 10.1002/art.21528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wei X, Zhang X, Zuscik MJ, Drissi MH, Schwarz EM, O’Keefe RJ. Fibroblasts express RANKL and support osteoclastogenesis in a COX-2-dependent manner after stimulation with titanium particles. J Bone Miner Res. 2005;20:1136–1148. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.050206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee MJ, Evans M, Hla T. The inducible G protein-coupled receptor edg-1 signals via the G(i)/mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:11272–11279. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.19.11272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pederson L, Ruan M, Westendorf JJ, Khosla S, Oursler MJ. Regulation of bone formation by osteoclasts involves Wnt/BMP signaling and the chemokine sphingosine-1-phosphate. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:20764–20769. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805133106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brinkmann V, Davis MD, Heise CE, Albert R, Cottens S, Hof R, Bruns C, Prieschi E, Baumruker T, Hiestand P, Foster CA, Zollinger M, Lynch KR. The immune modulator FTY720 targets sphingosine 1-phosphate receptors. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:21453–21457. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C200176200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Graler MH, Goetzl EJ. The immunosuppressant FTY720 down-regulates sphingosine 1-phosphate G-protein-coupled receptors. FASEB J. 2004;18:551–553. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-0910fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pham TH, Okada T, Matloubian M, Lo CG, Cyster JG. S1P1 receptor signaling overrides retention mediated by G alpha i-coupled receptors to promote T cell egress. Immunity. 2007;28:122–133. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.11.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tsunemi S, Iwasaki T, Kitano S, Imado T, Miyazawa K, Sano H. Effects of the novel immunosuppressant FTY720 in a murine rheumatoid arthritis model. Clin Immunol. 2010;136:197–204. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2010.03.428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Matsuura M, Imayoshi T, Okumoto T. Effect of FTY720, a novel immunosuppressant, on adjuvant- and collagen-induced arthritis in rats. Int J immunopharmacol. 2000;22:323–331. doi: 10.1016/s0192-0561(99)00088-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mclnnes IB, Schett G. Cytokines in the pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7:429–442. doi: 10.1038/nri2094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xia P, Gamble JR, Rye KA, Wang L, Hii CS, Cockerill P, Khew-Goodall Y, Bert AG, Barter PJ, Vadas MA. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha induces adhesion molecule expression through the sphingosine kinase pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:14196–14201. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.24.14196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Billich A, Bornancin F, Mechtcheriakova D, Natt F, Huesken D, Baumruker T. Basal and induced sphingosine kinase 1 activity in A549 carcinoma cells: function in cell survival and IL-1 beta and TNF-alpha induced production of inflammatory mediators. Cell signal. 2005;17:1203–1217. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2004.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lai WQ, Irwan AW, Goh HH, Howe HS, Yu DT, Valle-Onate R, Mclnnes IB, Melendez AJ, Leung BP. Anti-inflammatory effects of sphingosine kinase modulation in inflammatory arthritis. J Immunol. 2008;181:8010–8017. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.11.8010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]