Abstract

Objectives: Hospice care provided to nursing home (NH) residents has been shown to improve the quality of end-of-life (EOL) care. However, hospice utilization in NHs is typically low. This study examined the relationship between facility self-reported EOL practices and residents’ hospice use and length of stay. Design: The study was based on a retrospective cohort of NH residents. Medicare hospice claims, Minimum Data Set, Online Survey, Certification, and Reporting system and the Area Resource File were linked with a survey of directors of nursing (DON) regarding institutional EOL practice patterns (EOLC Survey). Setting and Participants: In total, 4,540 long-term–care residents who died in 2007 in 290 facilities which participated in the EOLC Survey were included in this study. Measurements: We measured NHs’ tendency to offer hospice to residents and to initiate aggressive treatments (hospital transfers and feeding tubes) for EOL residents based on DON’s responses to survey items. Residents’ hospice utilization was determined using Medicare hospice claims. Results: The prevalence of hospice use was 18%. The average length of stay was 93 days. After controlling for individual risk factors, facilities’ self-reported practice measures associated with residents’ likelihood of using hospice were tendency to offer hospice (p = .048) and tendency to hospitalize (p = .002). Residents in NHs reporting higher tendency to hospitalize tended to enroll in hospice closer to death. Conclusion: Residents’ hospice utilization is not only associated with individual and facility characteristics but also with NHs’ self-reported EOL care practices. Potential interventions to effect greater use of hospice may need to focus on facility-level care processes and practices.

Key Words: Hospice utilization, Hospice length of stay, Quality of end-of-life care, Nursing home end-of-life care practices, Hospice referral

Nursing homes (NHs) have become a common site where older Americans live and die. About 25% Americans die in NHs (Gruneir et al., 2007; National Center for Health Statistics, 2008; Weitzen, Teno, Fennell, & Mor, 2003). Despite of their growing importance in providing end-of-life (EOL) care, the quality of EOL care in NHs is often inadequate. Prior studies have suggested that NH residents at the EOL may not receive adequate symptom management, are frequently and often inappropriately transferred to hospitals, and are likely to receive invasive procedures (e.g., feeding tubes) that lack clinically proven benefits at the EOL (Gessert, Haller, Kane, & Degenholtz, 2006; Mukamel et al., 2012; Saliba et al., 2000; Teno et al., 2004; Teresi, Abrams, Holmes, Ramirez, & Eimicke, 2001; Travis, Loving, McClanahan, & Bernard, 2001).

Hospice has been viewed as a mechanism for improving the quality of EOL care. NH residents receiving hospice care have been shown to have lower risk of hospitalization and higher probability of receiving pain management in accordance with clinical guidelines (Gozalo & Miller, 2007; Miller, Mor, & Teno, 2003). Families reported that their loved ones’ physical symptoms and emotional needs were better addressed after hospice enrollment (Baer & Hanson, 2000). The prevalence of hospice use in NHs has increased from less than 10% in 1996 to 33% in 2006 (Miller, Lima, Gozalo, & Mor, 2010; Miller & Mor, 2001, 2004). Despite this growth, the rate of hospice use in NHs remains generally low and varies substantially across states and across facilities (Miller et al., 2010; Petrisek & Mor, 1999; Zerzan, Stearns, & Hanson, 2000). In addition, many hospice users do not enroll in hospice until very close to death, which may not allow sufficient time to effectively manage their symptoms and to meet their care needs (Miller, Mor, et al., 2003; Miller, Teno, & Mor, 2004). More than one third of NH hospice enrollees use hospice for a week or less, and about 16% of hospice stays last no more than 3 days (Huskamp, Stevenson, Grabowski, Brennan, & Keating, 2010; Miller, Weitzen, & Kinzbrunner, 2003). The prevalence of such short stays has increased significantly over time (Miller, Weitzen, et al., 2003).

Studies have identified several categories of factors associated with hospice use in NHs: individual characteristics (e.g., health and demographic factors, treatment restrictions and preferences), state policies (e.g., Medicaid case-mix reimbursement, hospice certificate of need), facility characteristics and market attributes (e.g., ownership, staffing, hospital and hospice supply) (Christakis & Iwashyna, 2000; Huskamp et al., 2010; Iwashyna, Chang, Zhang, & Christakis, 2002; Miller et al., 2010; Miller & Mor, 2004; Petrisek & Mor, 1999), and rural–urban locations(Temkin-Greener, Zheng, & Mukamel, 2012). However, to our knowledge, no study has yet examined the effect of EOL care practice style on residents’ hospice utilization. Compared with facility structural attributes, practice styles may be more mutable and, therefore, represent better opportunities for increasing hospice utilization in NHs. The objective of this study was to address this gap in the literature by answering the following questions: (a) Is NH’s self-reported tendency to offer hospice to EOL residents an independent factor associated with residents’ hospice utilization? (b) Is NH’s self-reported tendency to initiate aggressive treatments (hospital transfers and feeding tubes) independently associated with residents’ hospice utilization?

Design and Methods

Data and Population

This study used survey and administrative data. The End-of-Life Care (EOLC) survey was originally conducted in 2007 in New York State (NYS) NHs to develop EOL care process measures (Temkin-Greener et al., 2009). The EOLC Survey focused on Directors of Nursing (DON) as respondents and included questions about facilities’ EOL care practices, such as tendency to offer hospice and treatment aggressiveness. The survey methods have been described in detail elsewhere (Temkin-Greener et al., 2009). DONs from 313 NHs returned the survey (representing a response rate of 51.5%) among which 290 facilities had answered the questions on EOL care practices. These 290 facilities were included in this study. The Medicare Denominator File and the Minimum Data Set (MDS) were used to indentify residents in these facilities who died in 2007. The MDS also provided residents’ demographics, documentation for treatment restrictions, and health status. Medicare Hospice Claims data were used to measure hospice utilization. The Online Survey Certification and Reporting (OSCAR) system and the Area Resource File provided facility characteristics and market regions.

Long-term–care residents in the 290 study facilities who died in 2007 were eligible for the study. Long-term–care residents were defined as meeting either of the two following criteria: (a) had length of stay in NHs of 3 months or more; (b) had length of stay of less than 3 months, but the stay was not for rehabilitative/post-acute care and not paid by Medicare. Short-term rehabilitative/post-acute residents were not included because they typically have differently care goals and generally are not anticipated to die during a post-acute session; that is, these individuals were not regarded as potentially EOL residents. Two exclusions were made: (a) residents younger than 65 years of age and (b) those without a comprehensive MDS assessment (initial, annual, or significant change) within 3 months prior to hospice enrollment (for hospice users) or in the last 3 months of life (for hospice nonusers), as they were missing important EOL health information. In total, 4,540 decedents were identified as the study sample, representing about 40% of the decedents from the study facilities.

Variable Construction

Outcome Variables.

Hospice use—a dichotomous variable—was measured for each individual who indicated hospice use. Length of hospice use—a continuous variable—was constructed for hospice users, measuring the number of days as hospice enrollees. We defined hospice as hospice services provided in NHs; therefore, inpatient hospice care provided in hospital-based hospices was not included.

Variables of Interests.

Three main variables of interests, assessing NHs’ EOL practice style, were included. Each of these variables was based on a five-point Likert scale with a numeric score ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The tendency to offer hospice was measured by the DON’s response to the statement “We offer hospice routinely to residents who are near the end of life.” Tendency to hospitalize was measured using response to statement “Residents at the end of life need to be hospitalized to receive proper care for infections such as pneumonia.” Feeding tube initiation was measured using the statement “When residents at the end of life lose weight or stop eating, we frequently insert a feeding tube.” We checked the pairwise correlations among these variables of interest and found no evidence of multicollinearity.

Covariates.

Following literature review and consultation with clinical experts, we developed a list of individual risk adjustors and selected facility characteristics that are likely to influence hospice utilization and available in the MDS and the OSCAR (Gozalo & Miller, 2007; Petrisek & Mor, 1999) In order to control for individuals’ health, we used the last comprehensive MDS assessment before hospice enrollment date for hospice users and the last comprehensive MDS assessment prior to death (nonenrollment) for hospice nonusers. The average number of days between the selected MDS assessment and the study outcome was 34.4 (SD = 27.4) for hospice residents and 39.6 (SD = 26.3) for nonhospice residents. All risk adjustment variables used in the final models are presented and defined in Table 1.

Table 1.

Residents and Facility Characteristics: A Two-Level Comparison of the Study Sample and All Nursing Home Residents in New York State

| Independent variable | Definition/Level | Study sampleM (SD)/% | New York StateM (SD)/% | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Facility characteristic | n = 290 | n = 615 | ||

| Tendency to offer hospicea | Continuous; range: 1–5; higher score indicates higher tendency to offer hospice | 3.78 (1.34) | —b | |

| Tendency to hospitalizea | Continuous; range: 1–5; higher score indicates higher tendency to hospitalize residents | 1.54 (0.93) | —b | |

| Feeding tube initiationa | Continuous; range: 1–5; higher score indicates higher tendency to initiate feeding tubes | 1.77 (0.97) | ||

| Religious affiliationa | Dichotomous | 22.44% | —b | |

| Percent of Black residentsc | Continuous | 13.44% (0.19) | 13.05% (0.19) | .715 |

| Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) Case-Mix Index (CMI)c | Continuous; indicator of patient severity and the level of resources (nursing staff time based) used. A facility caring for average patients has a CMI of 1. | 1.04 (0.10) | 1.03 (0.10) | .150 |

| Licensed practical nurses (LPN) and certified nurse aides (CNA) hour per resident dayd | Continuous | 3.08 (0.51) | 3.05 (0.55) | .293 |

| RN to LPN and CNA ratiod | Continuous | 15.74% (0.05) | 16.27% (0.06) | <.001 |

| Percent of Medicaid residentsd | Continuous | 12.46% (0.08) | 12.95% (0.12) | .363 |

| Percent of Medicare residentsd | Continuous | 69.70% (0.14) | 69.99% (0.18) | .389 |

| Percent of private-pay residentsd | Continuous | 17.84% (0.11) | 17.06% (0.14) | .673 |

| Sized | Continuous; the number of residents in certified beds | 186.35 (129.47) | 170.92 (120.63) | .037 |

| For-profit facilityd | Dichotomous | 48.87% | 48.29% | .949 |

| Chain membershipd | Dichotomous | 11.72% | 12.68% | .647 |

| Individual characteristicc | n = 4,540 | n = 9,494 | ||

| Hospice use | Yes | 18.19% | 17.22% | .105 |

| No | 81.81% | 82.78% | ||

| Age | Continuous | 86.27 (7.94) | 85.66 (9.26) | <.001 |

| Race (ref = White) | White | 80.53% | 82.24% | <.001 |

| Black | 11.70% | 10.67% | ||

| Other | 7.78% | 7.09% | ||

| Marital status | Single/divorced/widowed | 78.92% | 78.79% | .967 |

| Married | 21.08% | 21.21% | ||

| Men | Dichotomous | 34.07% | 33.60% | .052 |

| Do not resuscitate | Dichotomous | 70.13% | 72.50% | <.001 |

| Do not hospitalize | Dichotomous | 10.42% | 10.63% | .565 |

| Diabetes | Dichotomous | 31.34% | 31.50% | .479 |

| Congestive heart failure | Dichotomous | 30.22% | 30.83% | .742 |

| Dementia | Dichotomous | 43.33% | 43.88% | .157 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | Dichotomous | 21.50% | 22.74% | .064 |

| Cancer | Dichotomous | 15.18% | 16.18% | .004 |

| Renal failure | Dichotomous | 10.79% | 11.07% | .417 |

| Depression | Dichotomous | 43.59% | 43.15% | .754 |

| End-stage diagnosis | Dichotomous | 9.05% | 11.53% | <.001 |

| Fracture in the last 180 days | Dichotomous | 6.36% | 6.12% | .683 |

| Severe pain | Dichotomous | 12.86% | 13.76% | .076 |

| Dyspnea | Dichotomous | 18.12% | 20.10% | .003 |

| Activity of daily living | Continuous; range: 0–28; higher scores indicate more disabled | 22.09 (6.10) | 22.14 (6.07) | .573 |

| Severe cognitive impairment | Dichotomous; cognitive performance score (CPS) score = 6 or 7 | 28.68% | 30.06% | .145 |

| CPS score = 1–5 | 71.32% | 69.94% |

aData source: EOL care survey.

bThe variable was based on the EOL care survey and not available for the New York State nursing homes.

cData source: MDS.

dData source: OSCAR.

Statistical Analysis

Two statistical steps were performed using STATA 10.0 (StataCorp LP, TX). First, we fit a logistic model with hospice use as the dependent variable. In the second step, we fit a generalized linear model (GLM) to estimate the length of hospice use. Because the length of hospice use was highly right skewed, the log was specified as the link function in GLM. We chose the link function instead of a regular regression with log-transformed dependent variable because the GLM directly models the outcome on its original scale so that the results may be interpreted directly without retransforming from log scale to the original scale (Buntin & Zaslavsky, 2004). Exponential of the parameter estimates was calculated to provide the magnitude of the multiplicative effect of one-unit increase in a predictor on the dependent variable. We included fixed effects of metropolitan/micropolitan statistical areas (MSA) in both models to control for the fact that residents from same market area may be subject to same hospice supply, hospital supply, and local practice patterns, which in turn influence their hospice utilization. For both models, we used Huber White sandwich (robust) estimates of variance and standard errors clustered by NHs. We calculated the standardized residuals and removed outliers (about 5% of the observations with large residuals) from both models to reduce potential bias due to influential observations. The squared terms of the variables of interest were tested to explore the possible nonlinear relationships.

Results

Descriptive Characteristics

Because the analysis was based on NHs that had responded to the EOL care survey rather than a random sample of NYS facilities, the possibility of a selection bias was considered. We compared the study facilities to all NHs in NYS with regard to facility characteristics, residents’ hospice use, demographics, treatment restrictions, and health characteristics. The results are presented in Table 1. Compared with NYS facilities, NHs in the study sample employed slightly fewer registered nurses (RN) (p < .001) and were larger (p = .037). At the resident level, the study population was slightly older (p < .001), included fewer Whites (p < .001), and had lower rates of do-not-resuscitate (DNR) orders (p < .001). The sample population was also somewhat healthier as suggested by lower prevalence of cancer, end-stage diagnosis, and dyspnea, compared with all NH residents (p = .004, p < .001, and p = .003, respectively).

Characteristics of the study residents and their facilities are summarized by hospice use status (Table 2).Overall, about 18% of the study residents used Medicare hospice services in NHs before death. The length of hospice use was on average 93 days, with a large variation (SD = 144.75, with first decile, median, and ninth decile being 3, 23.50, and 294 days, respectively). Compared with hospice nonusers, hospice users tended to reside in facilities with more staff hours per resident day, for licensed practical nurses (LPN) and certified nurse aides (CNA) combined (3.27 vs. 3.04hr), lower RN to LPN and CNA ratio (15.44% vs. 16.19%), fewer Black and Medicaid residents (8.09% vs. 13.68% and 67.66% vs. 70.14%, respectively), more private-pay residents (19.64% vs. 17.44%), and for-profit facilities (32.28% vs. 46.10%). Hospice users were different from hospice nonusers in other ways. They were more likely to be White (88.50% vs. 78.76%) and less likely to be men (30.51% vs. 34.87%), and they were more likely to have had DNR and do-not-hospitalize orders prior to hospice enrollment (80.27% vs. 67.88% and 12.95% vs. 9.85%, respectively). Hospice users and nonusers also differed with regard to diseases and health conditions. Cancer (20.46% vs. 14.00%), depression (50.97% vs. 41.95%), and fractures (7.99% vs. 6.03%) were more common among hospice users, whereas congestive heart failure (26.27% vs. 31.10%), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) (15.74% vs. 22.78%), and renal failure (8.23% vs. 11.36%) were more prevalent among hospice nonusers. More hospice users had end-stage diagnosis (14.41% vs. 7.86%). Fewer hospice users stayed in NHs for short periods of time—less than 92 days (25.77% vs. 30.03%).

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistics by Hospice Status

| Dependent variable | Hospice | Nonhospice | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n = 826 (18.19%) | n = 3,714 (81.81%) | ||

| Independent variable | M (SD)/% | M (SD)/% | p Value |

| Facility characteristic | |||

| Tendency to offer hospice | 3.86 (1.25) | 3.79 (1.34) | .211 |

| Tendency to hospitalize | 1.46 (0.83) | 1.63 (1.04) | <.001 |

| Feeding tube initiation | 1.85 (1.02) | 1.72 (0.94) | .001 |

| Religious affiliation | 22.64% | 20.60% | .192 |

| CMS case-mix index | 1.06 (0.09) | 1.06 (0.09) | .965 |

| Percent of Black residents | 8.09% (0.11) | 13.68% (0.19) | <.001 |

| Licensed practical nurses (LPN) and certified nurse aides (CNA) hour per resident day | 3.27 (0.57) | 3.04 (0.47) | <.001 |

| RN to LPN and CNA ratio | 15.44% (0.05) | 16.19% (0.05) | <.001 |

| Percent of Medicaid residents | 67.66% (0.12) | 70.14% (0.14) | <.001 |

| Percent of Medicare residents | 12.70% (0.08) | 12.41% (0.08) | .379 |

| Percent of private-pay residents | 19.64% (0.11) | 17.44% (0.10) | <.001 |

| Size | 236.06 (132.30) | 240.14 (143.36) | .455 |

| For-profit facility | 32.28% | 46.10% | <.001 |

| Chain membership | 10.65% | 10.72% | .955 |

| Individual characteristic | |||

| Age | 86.63 (7.50) | 86.19 (8.03) | .147 |

| Race | <.001 | ||

| White | 88.50% | 78.76% | |

| Black | 6.17% | 12.92% | |

| Other | 5.33% | 8.32% | |

| Married | 22.79% | 20.70% | .185 |

| Men | 30.51% | 34.87% | .017 |

| Do not resuscitate | 80.27% | 67.88% | <.001 |

| Do not hospitalize | 12.95% | 9.85% | .008 |

| Diabetes | 29.18% | 31.83% | .138 |

| Congestive heart failure | 26.27% | 31.10% | .006 |

| Dementia | 46.13% | 42.70% | .073 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 15.74% | 22.78% | <.001 |

| Cancer | 20.46% | 14.00% | <.001 |

| Renal failure | 8.23% | 11.36% | .009 |

| Depression | 50.97% | 41.95% | <.001 |

| End-stage diagnosis | 14.41% | 7.86% | <.001 |

| Fracture in the last 180 days | 7.99% | 6.03% | .037 |

| Severe pain | 14.89% | 12.41% | .054 |

| Dyspnea | 16.83% | 18.61% | .232 |

| Activities of daily living | 21.83 (5.89) | 22.15 (6.14) | .178 |

| Severe cognitive impairment | 26.27% | 29.21% | .091 |

| Nursing home length of stay | .015 | ||

| Less than 92 days | 25.77% | 30.03% | |

| Longer than 92 days | 74.23% | 69.97% | |

Factors Associated With Hospice Use

In Table 3, we present the results from the logistic regression model with hospice use as the dependent variable. The three facility self-reported EOL practice style measures were all significantly associated with hospice use. Living in facilities with reported higher tendency to offer hospice substantially increased residents’ odds of using hospice (odds ratio [OR] = 2.760, confidence interval [CI]: 1.135–6.716), and the odds increased at a diminishing rate (OR of squared term = 0.853, CI: 0.748–0.972) (p = .048, joint likelihood ratio test). Facilities’ reported tendency to hospitalize residents was also a significant predictor of residents’ hospice use (p = .002). Residents from NHs with higher tendency to hospitalize had lower odds of using hospice (OR = 0.679, CI: 0.532–0.866). We also found that residents from NHs with higher tendency to initialize feeding tubes had higher odds of using hospice (OR = 1.459, CI: 0.1.132–1.880).

Table 3.

Multivariate Regression Models Predicting Hospice Utilization

| Dependent variable | Hospice use | Length of hospice use | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 3,752 | n = 694 | |||||||

| Independent variable | Odds ratio | 95% Confidence interval | p Value | Exp(beta)a | 95% Confidence interval | p Value | ||

| Facility characteristic | ||||||||

| Tendency to offer hospice | 2.760 | 1.135 | 6.716 | .025b | 1.671 | 0.663 | 4.209 | .276c |

| Tendency to offer hospice ^2 | 0.853 | 0.748 | 0.972 | .017b | 0.915 | 0.795 | 1.053 | .214c |

| Tendency to hospitalize | 0.679 | 0.532 | 0.866 | .002 | 0.734 | 0.529 | 1.018 | .064 |

| Feeding tube initiation | 1.459 | 1.132 | 1.880 | .003 | 0.974 | 0.757 | 1.255 | .841 |

| Religious affiliation | 2.004 | 1.296 | 3.099 | .002 | 1.492 | 1.033 | 2.153 | .033 |

| Percent of Black residents (per 1% increase) | 0.985 | 0.968 | 1.002 | .074 | 0.981 | 0.952 | 1.010 | .203 |

| CMS case-mix index (per 0.1 increase) | 0.887 | 0.709 | 1.110 | .296 | 0.909 | 0.688 | 1.203 | .506 |

| Licensed practical nurses (LPN) and certified nurse aides (CNA) hour per resident day | 5.422 | 3.035 | 9.687 | <.001 | 1.551 | 1.175 | 2.047 | .002 |

| RN to LPN and CNA ratio (per 1% increase) | 0.997 | 0.944 | 1.053 | .912 | 1.022 | 0.984 | 1.061 | .268 |

| Percent of Medicaid residents (ref group) | ||||||||

| Percent of Medicare residents (per 1% increase) | 1.075 | 1.044 | 1.106 | <.001 | 0.994 | 0.961 | 1.028 | .729 |

| Percent of private-pay residents (per 1% increase) | 0.995 | 0.976 | 1.015 | .644 | 0.986 | 0.963 | 1.009 | .232 |

| Size | 1.001 | 1.000 | 1.003 | .129 | 1.000 | 0.999 | 1.002 | .782 |

| For-profit facility | 0.707 | 0.456 | 1.098 | .122 | 1.101 | 0.757 | 1.602 | .615 |

| Chain membership | 0.635 | 0.375 | 1.072 | .089 | 0.788 | 0.315 | 1.968 | .609 |

| Individual characteristic | ||||||||

| Age | 0.989 | 0.975 | 1.003 | .116 | 1.025 | 0.999 | 1.051 | .061 |

| Race (ref = White) | ||||||||

| Black | 0.535 | 0.336 | 0.852 | .008 | 0.926 | 0.261 | 3.279 | .905 |

| Other | 0.540 | 0.302 | 0.964 | .037 | 0.338 | 0.101 | 1.128 | .078 |

| Married | 1.405 | 1.067 | 1.852 | .016 | 0.755 | 0.376 | 1.517 | .430 |

| Men | 0.745 | 0.589 | 0.943 | .014 | 0.392 | 0.196 | 0.782 | .008 |

| Do not resuscitate | 1.791 | 1.336 | 2.400 | <.001 | 0.879 | 0.548 | 1.412 | .595 |

| Do not hospitalize | 0.805 | 0.549 | 1.179 | .265 | 1.032 | 0.653 | 1.630 | .894 |

| Diabetes | 0.907 | 0.712 | 1.155 | .428 | 0.810 | 0.511 | 1.283 | .369 |

| Congestive heart failure | 0.613 | 0.477 | 0.787 | <.001 | 0.855 | 0.680 | 1.076 | .182 |

| Dementia | 1.253 | 1.017 | 1.545 | .034 | 0.863 | 0.572 | 1.303 | .484 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 0.580 | 0.435 | 0.774 | <.001 | 1.569 | 0.817 | 3.014 | .176 |

| Cancer | 2.105 | 1.621 | 2.734 | <.001 | 0.577 | 0.304 | 1.095 | .092 |

| Renal failure | 0.580 | 0.398 | 0.846 | .005 | 0.331 | 0.089 | 1.230 | .099 |

| Depression | 1.466 | 1.167 | 1.841 | .001 | 0.954 | 0.762 | 1.193 | .678 |

| End-stage diagnosis | 2.841 | 1.901 | 4.246 | <.001 | 1.492 | 0.951 | 2.341 | .082 |

| Fracture in the last 180 days | 0.999 | 0.658 | 1.518 | .996 | 1.904 | 0.991 | 3.659 | .053 |

| Severe pain | 1.299 | 0.967 | 1.746 | .082 | 0.611 | 0.323 | 1.158 | .131 |

| Dyspnea | 0.853 | 0.614 | 1.187 | .347 | 0.604 | 0.328 | 1.110 | .104 |

| Activities of daily living (per score increase) | 1.011 | 0.990 | 1.032 | .309 | 1.038 | 0.989 | 1.089 | .132 |

| Severe cognitive impairment | 0.765 | 0.586 | 0.997 | .048 | 1.593 | 1.082 | 2.344 | .018 |

| Nursing home length of stay (ref = less than 92 days) | ||||||||

| Longer than 92 days | 1.089 | 0.817 | 1.450 | .560 | 1.253 | 0.643 | 2.440 | .508 |

| C-stat = 0.842 | R 2 = .361 | |||||||

aExp(beta) presents the magnitude of multiplicative effect of one unit increase in a predictor on the dependent variable.

bJoint likelihood ratio (LR) test result significant p = .048.

cJoint LR test result not significant p = .398.

Several facility characteristics were associated with residents’ hospice use. Residents in facilities that were religiously affiliated (OR = 2.004, CI: 1.296–3.099) that had higher LPN and CNA staffing (OR = 5.422, CI: 3.035–9.687) or that had greater percentage of Medicare residents (OR = 1.075, CI: 1.044–1.106) had greater odds of using hospice.

Several individual factors were also associated with residents’ risk of hospice use. Demographic characteristics associated lower odds of hospice use included being Black or other minority groups (OR = 535, CI: 0.336–0.852 and OR = 0.540, CI: 0.302–0.964, respectively) and men (OR = 0.745, CI: 0.589–0.943). Being married was associated with higher odds of hospice use (OR = 1.405, CI: 1.067–1.852). Residents with a DNR order were more likely to enroll in hospice (OR = 1.791, CI: 1.336–2.400). Several diseases were associated with higher likelihood of hospice use, for example, dementia (OR = 1.253, CI: 1.017–1.545), cancer (OR = 2.105, CI: 1.621–2.734), and depression (OR = 1.466, CI: 1.167–1.841). On the other hand, residents with congestive heart failure (OR = 0.613, CI: 0.477–0.787) and COPD (OR = 0.580, CI: 0.435–0.774) had lower odds of hospice enrollment. Among individual factors, end-stage diagnosis had the largest impact on hospice enrollment (OR = 2.841, CI: 1.901–4.246). Residents with severe cognitive impairment had lower odds of using hospice (OR = 0.765, CI: 0.586–0.997).

Factors Associated With the Length of Hospice Use

Results from the GLM modeling the length of hospice use are also presented in Table 3. Of the three facility practice measures, only reported tendency to hospitalize was associated with the length of hospice use (p = .064). Residents in NHs with one point higher score for tendency to hospitalize used about 27% fewer hospice days (Exp(beta) = 0.734, CI: 0.529–1.018). Two facility characteristics were significantly associated with the length of hospice use. Residents in facilities with religious affiliation and in facilities with higher LPN and CNA hours per resident per day tended to use hospice for a longer period of time (p = .033 and p = .002, respectively).

Discussion

Although caring for residents at the EOL with increasingly complex care needs, NHs face challenges of staffing shortages, high turnover, inadequate staff training in EOL/palliative care, and limited financial resources. Medicare hospice benefit is often thought of as an opportunity to provide quality EOL care to residents without increasing the demands on NH staff (Gozalo & Miller, 2007; Miller, Mor, et al., 2003). However, the prevalence of hospice use in NHs has been quite low, perhaps too low to markedly influence the quality of EOL care (Miller & Mor, 2001; Miller et al., 2010; Petrisek & Mor, 1999; Zerzan et al., 2000). This is the first study, we are aware of, to focus on NH self-reported EOL practice styles as independent explanatory factors for hospice utilization. It demonstrates the independent importance of EOL self-reported practices in affecting residents’ probability of hospice use and their duration of hospice enrollment.

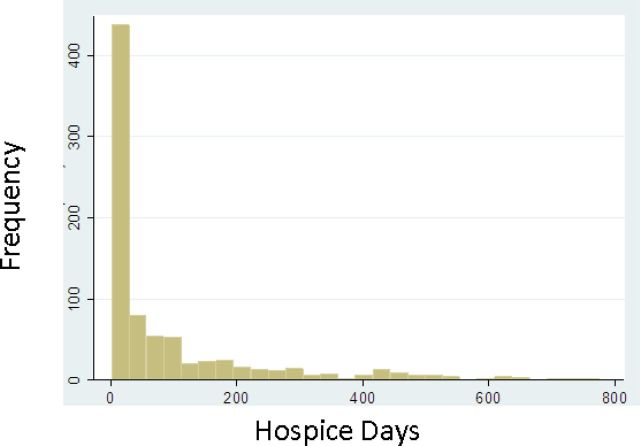

After controlling for individual risk factors and facility characteristics, we found that NH’s self-reported tendency to offer hospice significantly influences residents’ likelihood of hospice use, but not the length of hospice use. The duration of hospice enrollment varies substantially and is highly right skewed (Figure 1), which may reflect NH staff’s ability to recognize residents’ terminal status early enough to intervene with hospice referral. Although virtually all NHs experience a significant proportion of deaths among their residents each year, the staff typically do not view themselves as caring for the dying (Mezey et al., 2000). They receive very limited or no training in EOL care and may be limited in the skills to effectively recognize end-stage illness (Ersek, Kraybill, & Hansberry, 1999; Whittaker, Kernohan, Hasson, Howard, & McLaughlin, 2006). Less than 15% of residents in our sample were recognized as having life expectancy of 6 months or less in the last 3 months of life (Table 2). The uncertainty of disease trajectories for many residents further compounds hospice referral and its timeliness. The vast majority of NH residents had noncancer diagnoses and/or cognitive impairment for which clinical prognostication is often inaccurate and unstable (Christakis & Escarce, 1996; Forster & Lynn, 1988; Mitchell et al., 2004). Presently no EOL guidelines are specifically developed for NHs, and most facilities do not have formal EOL/palliative care programs or care protocols (Oliver, Porock, & Zweig, 2004; Temkin-Greener et al., 2009). As a result, residents who are indeed at the EOL may not be identified—and thus not referred to hospice—until very close to death, if at all.

Figure 1.

Distribution of the length of hospice use (M = 93.14, SD = 144.75, median = 23.50).

Our findings suggest that everything else being equal, residents living in facilities reporting higher tendency to transfer EOL residents to hospitals were less likely to use hospice and started using hospice closer to death, if at all. Facilities’ self-reported tendency to hospitalize could influence residents’ hospice utilization in two ways. First, facilities may present hospital care as superior to hospice care or even as the only option, which potentially shifts residents’ preferences away from hospice care. Second, in facilities with a higher hospitalization rate, residents may automatically choose the “norm” despite being offered the hospice option. Future studies need to disentangle these two possible mechanisms, as the two mechanisms require different interventions in order to increase hospice use.

Contrary to our expectations, we found that residents in NHs reporting higher tendency to initiate feeding tubes were also more likely to use hospice services. Although scientific evidence suggests that feeding tubes are not the standard of care for individuals with advanced dementia, once a decision is made to initiate a feeding tube, it may be more difficult for families and NH staff to stop such an intervention, even at the EOL. Furthermore, although NH’s self-reported tendency to initiate tube feedings may indicate their aggressiveness in care practices, it may also be perceived as an indicator of caring and responsiveness toward their residents when a resident may lose weight or stop eating at the EOL. Feeding tubes may be a way in which the NHs demonstrate caring and not “abandoning” residents (Gillick & Volandes, 2008). Hospice care may be an extension of this caring approach at the EOL irrespective of a prior feeding tube decision. Future studies are needed to better understand the relationship between NHs’ feeding tube use and hospice use patterns.

NHs’ EOL care practice styles may be influenced by several factors. NHs with greater access to hospice may be more likely to offer the hospice option to residents. Two studies have demonstrated the relationships between higher hospice utilization and more hospice providers in the same market and shorter distance to the closest hospice, respectively (Gozalo & Miller, 2007; Miller et al., 2010). Better data on NHs’ access to hospice and hospice capacities, which virtually do not exist now, (Medicare Payment Advisory Commission, 2008) are necessary to examine the effect of access on facilities’ practice styles. Regulations and rules regarding Medicare hospice benefit may also impact facilities’ practices. Hospice Wage Index for Fiscal Year 2010 (Federal Register/Vol. 74, No. 150/39384) included a few policy changes that can potentially reduce the length of hospice stay and thus contain Medicare cost, such as changes to the physician certification and recertification process and revisions to the hospice aggregate cap calculation. These changes may have a direct impact on hospices’ willingness to enroll residents with potentially longer stays due to unstable prognosis, for example, residents with dementia, COPD, and/or CHF. Consequently, NHs’ likelihood and timing for referring these residents to hospices may also be influenced. Moreover, NH staff’s limited knowledge about hospice/palliative care may result in misconceptions of hospice, which in turn could shift the facilities’ dependency toward aggressive measures (i.e., hospital transfers) for EOL care. Nationally, less than 20% of NHs have special programs and/or specifically trained staff on hospice/palliative EOL care (Miller & Han, 2008). Also, facilities’ practice styles may be determined by their own residents’ expressed treatment preferences at an aggregate level. Better communication between staff and residents with regard to advance care planning could result in facilities having better knowledge regarding their residents’ true preferences and may be important in changing facilities’ practice styles and hospice utilization.

In addition to the self-reported practice style variables, other facility characteristics were also associated with residents’ hospice utilization. First, residents living in religiously affiliated NHs were more likely to use hospice and to have longer use. It has been shown that religious facilities perform better in communicating with residents and families and in staff communication and care coordination (Temkin-Greener et al., 2009). Better communication with residents in regard to goals of care and preferences could result in greater hospice utilization (Casarett et al., 2005). Better communication and coordination among staff may result in earlier recognition of residents’ terminal status, thus potentially increasing the likelihood of hospice utilization. Second, residents in NHs with higher LPN and CNA staffing levels are more likely to use hospice. LPNs and CNAs are the frontline staff and assume more than 90% of direct patient care (Riggs & Rantz, 2001). Better communication between frontline staff—especially the CNAs—and coworkers has been shown to be associated with better EOL care processes, suggesting the important roles of LPNs and CNAs in providing EOL care (Zheng & Temkin-Greener, 2010). Having more LPNs and CNAs may increase the likelihood of noticing residents’ health decline and may also increase their influence if LPNs and CNAs advocate for residents, both potentially increasing the probability of using hospice.

Several study limitations should be mentioned. First, our study sample was slightly different from the general population of NYS NHs. Overall, these differences were minimal and unlikely to substantially bias the results. Second, the time gap between the last MDS assessment—the source of resident health characteristics—and the study outcome—hospice enrollment/nonenrollment—was smaller for hospice residents than for nonhospice residents (34.4 vs. 39.6 days). However, the difference was very small and unlikely to bias the relationships between facility self-reported EOL care practices and hospice use. Third, EOL care practices were assessed by a single respondent in each facility. Although facilities’ tendency to offer hospice and treatment aggressiveness are determined collaboratively by physicians, management teams, and nursing staff, the DON is in an ideal position to assess and report on the general care philosophy and EOL care practices in their facilities, as they provide oversight to nursing staff and play an integral part in the development and execution of facility policies and procedure. It has been shown that NH managers (including DONs) are able to provide a valid assessment of care in their facilities (Dubois, Bravo, & Charpentier, 2001). In addition, it is possible that DON’s reported EOL care practices are influenced by the predictive factors for actual hospice utilization, such as resident case mix and staffing. Our analyses addressed this confounding issue using comprehensive multivariate risk adjustment models in which confounders at both individual and facility level were controlled for. Fourth, our study focused on NYS facilities only. To generalize our findings, therefore, requires caution. Finally, our study focused on each resident’s last NH stay, and we did not control for the fact whether a resident had previous stays in the same NH. NH residents who had previous stays may be better known to the facility. The facility may be more familiar with their conditions and, therefore, more likely to recognize their terminal status. However, our study focused on long stay residents whose average length of NH stay is more than a year (Mukamel et al., 2012), which should give the NHs sufficient time to get familiar with their conditions. In addition, we controlled for whether the last NH stay is longer than 3 months—an indicator potentially associated with the NHs’ familiarity with the residents’ conditions.

In summary, this study suggests that NH residents’ hospice utilization is not only correlated with their individual risk factors and facility characteristics but also associated with the reported EOL care practice styles in their facilities. Potential interventions and policy initiatives designed to effect greater hospice utilization in NHs may need to focus on the practice styles at the facility level.

Funding

We gratefully acknowledge funding from the National Institute on Nursing Research, Grant R010727, and from the Foundation for Healthy Living in Albany, NY.

Acknowledgments

We express our gratitude to the nursing homes that have participated in the study.

References

- Baer W. M., Hanson L. C. (2000). Families’ perception of the added value of hospice in the nursing home. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 48(8), 879–882 PMID: 10968290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buntin M. B., Zaslavsky A. M. (2004). Too much ado about two-part models and transformation? Comparing methods of modeling Medicare expenditures. Journal of Health Economics, 23(3), 525–542. 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2003.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casarett D., Karlawish J., Morales K., Crowley R., Mirsch T., Asch D. A. (2005). Improving the use of hospice services in nursing homes: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association, 294(2), 211–217. 10.1001/jama.294.2.211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christakis N. A., Escarce J. J. (1996). Survival of Medicare patients after enrollment in hospice programs. The New England Journal of Medicine, 335(3), 172–178. 10.1056/NEJM199607183350306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christakis N. A., Iwashyna T. J. (2000). Impact of individual and market factors on the timing of initiation of hospice terminal care. Medical Care, 38(5), 528–541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubois M. F., Bravo G., Charpentier M. (2001). Which residential care facilities are delivering inadequate care? A simple case-finding questionnaire. Canadian Journal on Aging-Revue Canadienne Du Vieillissement, 20(3), 339–355. 10.1017/S0714980800012812 [Google Scholar]

- Ersek M., Kraybill B. M., Hansberry J. (1999). Investigating the educational needs of licensed nursing staff and certified nursing assistants in nursing homes regarding end-of-life care. The American Journal of Hospice & Palliative Care, 16(4), 573–582. 10.1177/ 104990919901600406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forster L. E., Lynn J. (1988). Predicting life span for applicants to inpatient hospice. Archives of internal medicine, 148(12), 2540–2543. 10.1001/archinte.1988.00380120010003 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gessert C. E., Haller I. V., Kane R. L., Degenholtz H. (2006). Rural-urban differences in medical care for nursing home residents with severe dementia at the end of life. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 54(8), 1199–1205. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00824.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillick M. R., Volandes A. E. (2008). The standard of caring: Why do we still use feeding tubes in patients with advanced dementia? Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 9(5), 364–367. 10.1016/j.jamda.2008.03.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gozalo P. L., Miller S. C. (2007). Hospice enrollment and evaluation of its causal effect on hospitalization of dying nursing home patients. Health Services Research, 42(2), 587–610. 10.1111/ j.1475-6773.2006.00623.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruneir A., Mor V., Weitzen S., Truchil R., Teno J., Roy J. (2007). Where people die: A multilevel approach to understanding influences on site of death in America. Medical Care Research and Review: MCRR, 64(4), 351–378. 10.1177/1077558707301810 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huskamp H. A., Stevenson D. G., Grabowski D. C., Brennan E., Keating N. L. (2010). Long and short hospice stays among nursing home residents at the end of life. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 13(8), 957–964. 10.1089/jpm.2009.0387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwashyna T. J., Chang V. W., Zhang J. X., Christakis N. A. (2002). The lack of effect of market structure on hospice use. Health Services Research, 37(6), 1531–1551. 10.1111/1475-6773.10562 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (2008). Report to congress: Reforming the delivery system. Chapter 8: Evaluating Medicare’s hospice benefit Washington, D.C. http://www.medpac.gov/documents/jun08_entirereport.pdf

- Mezey M. D., Dubler N. N., Bottrell M., Mitty E., Ramsey G., Post L. F., et al. (2000). Guidelines for end-of-life care in nursing homes: Principles and recommendations (report), New York: The John A. Hartford Foundation Institute for Geriatric Nursing; http://www.hartfordign.org/uploads/File/policy_papers_guidelines_end_of_life.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Miller S. C., Han B. (2008). End-of-life care in U.S. nursing homes: Nursing homes with special programs and trained staff for hospice or palliative/end-of-life care. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 11(6), 866–877. 10.1089/jpm.2007.0278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller S. C., Lima J., Gozalo P. L., Mor V. (2010). The growth of hospice care in U.S. nursing homes. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 58(8), 1481–1488. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.02968.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller S. C., Mor V. (2001). The emergence of Medicare hospice care in US nursing homes. Palliative Medicine, 15(6), 471–480. 10.1191/ 026921601682553950 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller S. C., Mor V. (2004). The opportunity for collaborative care provision: The presence of nursing home/hospice collaborations in the U.S. states. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 28(6), 537–547. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2004.10.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller S. C., Mor V., Teno J. (2003). Hospice enrollment and pain assessment and management in nursing homes. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 26(3), 791–799. 10.1016/S0885-3924(03)00284-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller S. C., Teno J. M., Mor V. (2004). Hospice and palliative care in nursing homes. Clinics in geriatric medicine, 20(4), 717–34. 10.1016/j.cger.2004.07.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller S. C., Weitzen S., Kinzbrunner B. (2003). Factors associated with the high prevalence of short hospice stays. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 6(5), 725–736. 10.1089/109662103322515239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell S. L., Kiely D. K., Hamel M. B., Park P. S., Morris J. N., Fries B. E. (2004). Estimating prognosis for nursing home residents with advanced dementia. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association, 291(22), 2734–2740. 10.1001/jama.291.22.2734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukamel D. B., Caprio T., Ahn R., Zheng N. T., Norton S., Quill T., et al. (2012). End-of-life quality-of-care measures for nursing homes: Place of death and hospice. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 15(4), 438–446. 10.1089/jpm.2011.0345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Health Statistics (2008). Mortality data, multiple cause-of-death public-use data files. Worktable 309. Deaths by place of death, age, race, and sex: United States, 1999–2005 (Report No. Worktable 309), National Center for Health Statistics; NCHS, CDC, Atlanta, GA. [Google Scholar]

- Oliver D. P., Porock D., Zweig S. (2004). End-of-life care in U.S. nursing homes: A review of the evidence. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 5(3), 147–155. 10.1097/01.JAM.0000123063.79715.8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrisek A. C., Mor V. (1999). Hospice in nursing homes: A facility-level analysis of the distribution of hospice beneficiaries. The Gerontologist, 39(3), 279–290. 10.1093/geront/39.3.279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riggs C. J., Rantz M. J. (2001). A model of staff support to improve retention in long-term care. Nursing Administration Quarterly, 25(2), 43–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saliba D., Kington R., Buchanan J., Bell R., Wang M. M., Lee M., et al. (2000). Appropriateness of the decision to transfer nursing facility residents to the hospital. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 48(2), 154–163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Temkin-Greener H., Zheng N. T., Mukamel D. B. (2012). Rural-urban differences in end-of-life nursing home care: Facility and environmental factors. The Gerontologist, 52(3), 335–344. 10.1093/geront/gnr143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Temkin-Greener H., Zheng N. T., Norton S. A., Quill T., Ladwig S., Veazie P. (2009). Measuring end-of-life care processes in nursing homes. The Gerontologist, 49(6), 803–815. 10.1093/geront/gnp092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teno J. M. Clarridge B. R. Casey V. Welch L. C. Wetle T. Shield R.Mor, V. (2004). Family perspectives on end-of-life care at the last place of care. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association,, 291(1), 88–93. 10.1001/jama.291.1.88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teresi J., Abrams R., Holmes D., Ramirez M., Eimicke J. (2001). Prevalence of depression and depression recognition in nursing homes. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 36(12), 613–620. 10.1007/s127-001-8202-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Travis S. S., Loving G., McClanahan L., Bernard M. (2001). Hospitalization patterns and palliation in the last year of life among residents in long-term care. The Gerontologist, 41(2), 153–160. 10.1093/geront/41.2.153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weitzen S., Teno J. M., Fennell M., Mor V. (2003). Factors associated with site of death: A national study of where people die. Medical Care, 41(2), 323–335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whittaker E., George Kernohan W., Hasson F., Howard V., McLaughlin D. (2006). The palliative care education needs of nursing home staff. Nurse education today, 26(6), 501–510. 10.1016/j.nedt.2006.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zerzan J., Stearns S., Hanson L. (2000). Access to palliative care and hospice in nursing homes. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association, 284(19), 2489–2494. 10.1001/jama.284.19.2489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng N. T., Temkin-Greener H. (2010). End-of-life care in nursing homes: The importance of CNA staff communication. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 11(7), 494–499. 10.1016/j.jamda.2010.01.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]