Abstract

Impacted mandibular third molars are located between the second mandibular molar and mandibular ramus. However, ectopic mandibular third molars with heterotopic positions are reported in the subcondylar or pterygomandibular space. The usual cause of malposition is a cyst or tumor, and malposition without a pathology is rare. This case report described an impacted mandibular third molar in the pterygomandibular space without any associated pathology.

Keywords: Third molar, Pterygomandibular space

I. Introduction

The surgical extraction of an impacted mandibular third molar is one of the most common procedures performed by oral and maxillofacial surgeons. Most mandibular third molars are impacted in the mandibular ramus area near the second molar, and the level of difficulty of extraction is classified according to the degree of impaction, position in the mandibular ramus, and angulation of the long axis of teeth. Usually, a third molar impacted far away from its original site is affected by a cyst or a tumor. Only a few cases of ectopic mandibular third molar in the region of pterygomandibular space without association of cystic lesion--such as odontogenic keratocyst and dentigerous cyst--have been reported1,2. We report a case of mandibular third molar located in the pterygomandibular space that seems to have been displaced by neither cyst nor tumor.

II. Case Report

A 46-year-old male patient visited the Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Seoul National University Dental Hospital, complaining of swelling and pain in the right preauricular region. He was previously told by a general dentist at a local clinic that he had a malposed tooth in the right mandible and was advised not to have the tooth extracted until symptoms appear. A panoramic radiograph showed a third molar located high in the ascending ramus of the right mandible.(Fig. 1) To identify the exact location of the tooth, computed tomography (CT) was taken, showing the third molar in the pterygomandibular space associated with a radiolucent lesion.(Fig. 2) The radiolucent lesion was evaluated as cystic lesion such as odontogenic keratocyst or dentigerous cyst or secondary inflammation accompanied by soft tissue involvement.

Fig. 1.

Panoramic view of ectopic mandibular third molar in the right ascending ramus of the mandible.

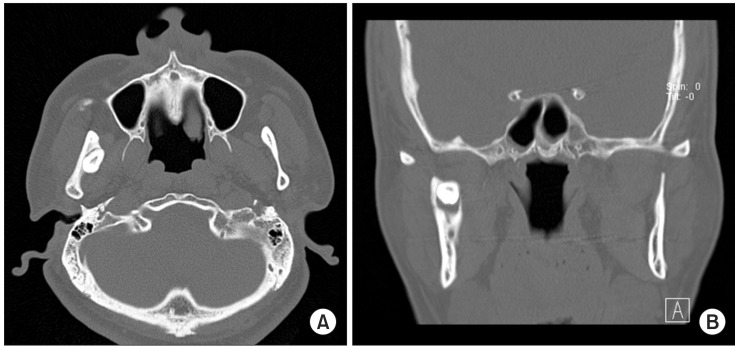

Fig. 2.

Axial image (A) and coronal image (B) of computed tomography (CT). CT scans show that the mandibular third molar is located in the pterygomandibular space. The sclerotic change of the mandible around the mandibular third molar is consistent with chronic infection.

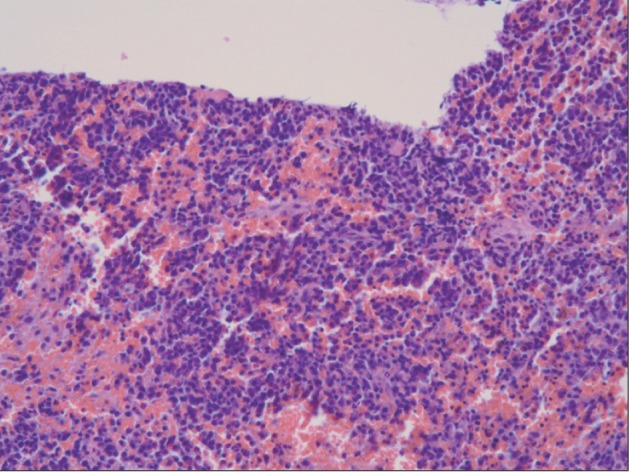

The surgery was performed under general anesthesia via the intraoral approach. An incision was made over the right external oblique ridge and extended from the second molar to the posterosuperior mandibular ascending ramus. Subperiosteal dissection was done superiorly, exposing the anterior border of the ramus from the retromolar area almost to the tip of the coronoid process. Medial subperiosteal dissection proceeded posteriorly, exposing the lingula and inferior alveolar neurovascular bundle up to the condyle neck. Osteotomy was performed with a round bur on the medial side of the mandible. The tooth was exposed and carefully removed.(Fig. 3) The tooth was easily removed from the area between the lingula and the sigmoid notch. The postoperative panoramic radiograph showed the removal of ectopic mandibular third molar.(Fig. 4) Sharp areas were smoothened, with the site curetted and cleaned with sterile saline solution. The surgical site was primarily sutured, with 4/0 vicryl applied. The postoperative wound healing was uneventful, with no nerve damage symptom. A small follicular space enveloping the crown of the tooth was also identified, suggesting inflamed granulation tissue.(Fig. 5) A connection to the periodontal space of the mandibular second molar was detected. In view of the sclerotic change of the underlying mandible (Fig. 2) and dental caries (Fig. 3B), we assume that there had been prolonged communication with the oral cavity. This ultimately led to the infectious process.

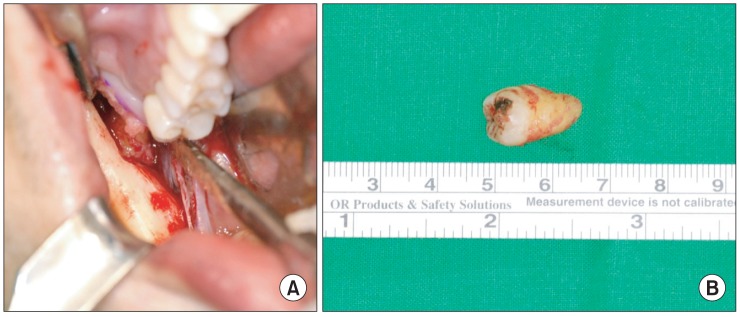

Fig. 3.

A. Intraoperative view of the ostectomy site in the medial aspect of the ascending ramus of the mandible. B. Removed ectopic mandibular third molar whose crown was blackened.

Fig. 4.

Postoperative panoramic radiograph showing the removal of the ectopic third molar in the pterygomandibular space.

Fig. 5.

Histopathologic imaging (H&E, ×200).

III. Discussion

Several studies have reported ectopic mandibular third molar in the mandibular ramus3,4, mandibular condyle5-7, and coronoid process8.

The true incidence and etiology of ectopic mandibular third molar remain unknown9. An aberrant eruption pattern has been suggested to occur when the tooth has been displaced by a lesion, usually an odontogenic cyst3,10,11. Dentigerous cyst is the most common benign lesion related to impacted mandibular third molar12. Over time, the pressure exerted by the intracystic fluid on the occlusal aspect of the third molar may cause its displacement, sometimes from its original location3,4,13.

In the present case, the mandibular third molar was not displaced by a cystic lesion but by an uncertain cause. The development of the tooth germ in an aberrant position or aberrant tooth germ eruption pattern may be the most likely etiology. Otherwise, primary and total dislocation of tooth base may be the cause8. In the process of mandibular skeletal growth, bone is typically added along the posterior ramus border and resorbed along the anterior border; mandibular condyle develops as a result of bone apposition in the posterior ramus14. In this case, the presence of dental caries implies that tooth dislocation occurred after its exposure to the oral cavity.

Keros and Susić8 reported the ectopic mandibular third molar in the coronoid process and assumed that the bone forming the mandibular base in childhood may shift to the region beneath the coronoid process in adulthood, with the ectopic mandibular third molar embedded. Following the normal growth pattern, the third molar crown moved upward, eventually reaching the coronoid process of the mandible in non-inverted state.

Nonetheless, the etiology of ectopic impaction and migration of tooth is still unclear. Peck15 reported that the intraosseous migration of impacted mandibular tooth is related to genetic determinants. According to Marks and Schroeder16, regional disturbance in the dental follicle might lead to local defective osteoclastic function, with an abnormal eruption pathway being formed. Sutton17 believed that an abnormally strong eruption force or a change affecting the crypt of the tooth germ might lead to erroneous eruption.

Surgical extraction is mostly performed by an intra-oral approach. Extra-oral approach is done in extremely displaced impacted tooth cases. When teeth are located near the mandibular condyle, the preauricular approach can be used. The approach has the advantage of good exposure of the surgical site but may result in complications such as extraoral scar, damage to temporomandibular joint, and facial nerve injury11. The intraoral approach may avoid these problems, but access to and view of the severely displaced tooth may be limited; thus making the surgery difficult. In this case, the impacted tooth was located on the lingual side of the pterygomandibular space, and the surgery was performed using the intraoral approach. During the surgery, the inferior alveolar nerve should be protected. Moreover, excessive grinding of the coronoid process or mandibular condyle should not be done to prevent fracture.

Nowadays, most third molar extractions are performed when the patients are in their twenties, so the dislocation becomes rarer. Moreover, there may be patients with ectopic tooth without clinical symptoms, not knowing that they have a dislocated tooth. Therefore, annual panoramic radiograph taking from childhood is recommended for the early detection of ectopic third molar and its pathologic changes such as cyst formation and infection. Impacted teeth diagnosed upon routine radiographic examination--and which are not associated with any pathology--usually do not require treatment, but they should be removed to prevent cyst formation, infection, and weakening of the bone predisposing to fracture7. The surgical extraction of the ectopic third molar should be carefully planned and performed to minimize complications induced by surgery.

References

- 1.Alling CC, 3rd, Catone GA. Management of impacted teeth. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1993;51(1 Suppl 1):3–6. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(93)90004-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kupferman SB, Schwartz HC. Malposed teeth in the pterygomandibular space: report of 2 cases. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2008;66:167–169. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2006.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bux P, Lisco V. Ectopic third molar associated with a dentigerous cyst in the subcondylar region: report of case. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1994;52:630–632. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(94)90105-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tümer C, Eset AE, Atabek A. Ectopic impacted mandibular third molar in the subcondylar region associated with a dentigerous cyst: a case report. Quintessence Int. 2002;33:231–233. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Medici A, Raho MT, Anghinoni M. Ectopic third molar in the condylar process: case report. Acta Biomed Ateneo Parmense. 2001;72:115–118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wassouf A, Eyrich G, Lebeda R, Grätz KW. Surgical removal of a dislocated lower third molar from the condyle region: case report. Schweiz Monatsschr Zahnmed. 2003;113:416–420. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gadre KS, Waknis P. Intra-oral removal of ectopic third molar in the mandibular condyle. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2010;39:294–296. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2009.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Keros J, Susić M. Heterotopia of the mandibular third molar: a case report. Quintessence Int. 1997;28:753–754. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bortoluzzi MC, Manfro R. Treatment for ectopic third molar in the subcondylar region planned with cone beam computed tomography: a case report. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2010;68:870–872. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2009.04.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Salmerón JI, del Amo A, Plasencia J, Pujol R, Vila CN. Ectopic third molar in condylar region. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2008;37:398–400. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2007.09.172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang CC, Kok SH, Hou LT, Yang PJ, Lee JJ, Cheng SJ, et al. Ectopic mandibular third molar in the ramus region: report of a case and literature review. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2008;105:155–161. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2007.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Suarez-Cunqueiro MM, Schoen R, Schramm A, Gellrich NC, Schmelzeisen R. Endoscopic approach to removal of an ectopic mandibular third molar. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2003;41:340–342. doi: 10.1016/s0266-4356(03)00111-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Szerlip L. Displaced third molar with dentigerous cyst--an unusual case. J Oral Surg. 1978;36:551–552. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Buschang PH, Gandini Júnior LG. Mandibular skeletal growth and modelling between 10 and 15 years of age. Eur J Orthod. 2002;24:69–79. doi: 10.1093/ejo/24.1.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Peck S. On the phenomenon of intraosseous migration of nonerupting teeth. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1998;113:515–517. doi: 10.1016/s0889-5406(98)70262-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marks SC, Jr, Schroeder HE. Tooth eruption: theories and facts. Anat Rec. 1996;245:374–393. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0185(199606)245:2<374::AID-AR18>3.0.CO;2-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sutton PR. Migration and eruption of non-erupted teeth: a suggested mechanism. Aust Dent J. 1969;14:269–270. doi: 10.1111/j.1834-7819.1969.tb06005.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]