Abstract

Objectives

This study aims to evaluate the severity and pattern of symptoms exhibited by teenage Korean temporomandibular disorder (TMD) patients.

Materials and Methods

Among patients with an association of TMDs, teenage patients (11-19 years) who answered the questionnaire on the research diagnostic criteria for TMD (RDC/TMD) were recruited.

Results

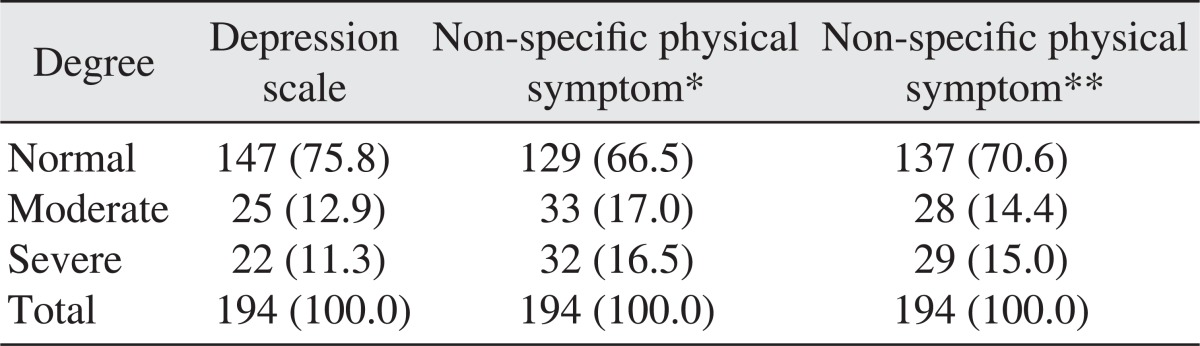

The ratio of patients who visited our clinic with a chief complaint of clicking sound (34.5%) or temporomandibular pain (36.6%) at the initial diagnosis (examination) was the highest. In the evaluation of the depression index, 75.8% of the subjects were normal, 12.9% were moderate, and 11.3% were severe. With regard to non-specific physical symptoms (including pain), 66.5% of the subjects were normal, 17.0% were moderate, and 16.5% were severe. Concerning non-specific physical symptoms (excluding pain), 70.6% of the subjects were normal, 14.4% were moderate, and 15.0% were severe. In terms of the graded chronic pain score, high disability (grade III, IV) was found in 9.3% of the subjects.

Conclusion

Among teenage TMD patients, a portion have clinical symptoms and experience severe psychological pressure; hence requiring attention and treatment, as well as understanding the psychological pressure and appropriate treatments for dysfunction.

Keywords: Teenager, Temporomandibular joint disorders

I. Introduction

As a representative musculoskeletal disease in the orofacial region, temporomandibular disorder (TMD) is one of the most frequent causes of non-odontogenic pain in the orofacial region. Nowadays, the number of TMD patients is on the rise, visiting dental clinics complaining of diverse symptoms.

Yang and Kim1 examined the incidence of Korean TMD patients and treatment modes. According to them, from 2003 to 2005, 0.15% of the population visited the hospital for TMD. There was an increase in patients every year, with teenagers showing a high incidence average with 22.5%. In Korea, numerous epidemiological studies on TMD have been reported after the 1970s1-3. Note, however, that studies on teenage patients are relatively rare. In particular, the ratio of teenage patients who are under high pressure due to their studies tends to rise; hence the need to evaluate not only the symptoms of teenage TMD patients but also their behavior and psychological factors.

The research diagnostic criteria for TMD (RDC/TMD) used in our study was prepared to examine patients with TMD by objective and standardized methods. Since it was introduced by Dworkin and LeResche4 in 1992, it has been translated into numerous languages worldwide and used widely to investigate TMD and maxillofacial pain. In clinical studies in particular, it contributes to systemic investigation and standardization, defines the investigation of an area that is difficult to measure, and proves the reliability of clinically standardized research methods. RDC/TMD consists of a dual-axis system; Axis I is mostly composed of the physical diagnosis of TMD, and Axis II, the evaluation of the behavioral, psychological and psychosocial factors associated with TMD. Specifically, RDC/TMD Axis II consists of a scale that evaluates depression; thus, it is also referred to as the RDC/TMD Axis II depression scale.

This study sought to evaluate the severity and pattern of TMD particularly the behavioral, psychological, and psychosocial factors present among Korean teenage TMD patients by analyzing their responses in the initial RDC/TMD Axis II questionnaire.

II. Materials and Methods

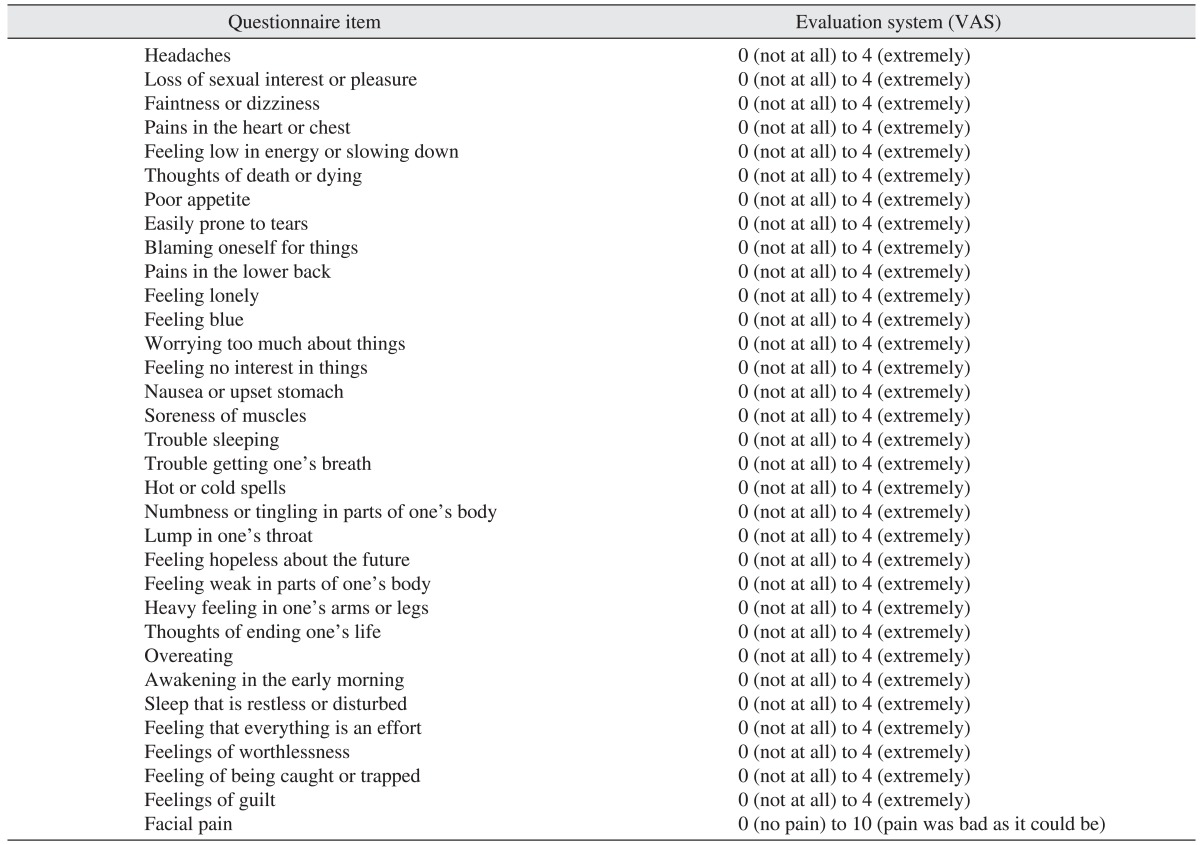

The subjects were teenagers (between 11 and 19 years of age) who first visited Seoul National University Bundang Hospital from January 2006 to December 2010 with chief complaint of TMD symptoms. Patients were asked to fill out the RDC/TMD questionnaire at the first visit. Only patients who completed the RDC/TMD questionnaire were included in this study; others who did not answer some of the questions were excluded. This study was conducted after obtaining approval from the Institutional Review Board of Seoul National University Bundang Hospital (B-1110-138-115). By analyzing the medical records of patients, radiological examinations, and RDC/TMD Axis II questionnaires prepared by patients at the initial examination, the symptoms and patterns exhibited by patients were evaluated retrospectively.(Table 1) Of the entire group of patients, the frequency of incidence of each diagnosis group, chief complaint of patients, level of impairment experienced by patients during daily activities, level of psychological pain (depression and vegetative symptoms), pain due to somatization, and graded chronic pain score (0-IV) were examined.

Table 1.

Main questionnaire items for the evaluation of depression, non-specificphysical symptoms, and graded chronic pain score

(VAS: visual analogue scale)

1. Frequency of incidence in each diagnosis group at the time of initial examination

The diagnosis groups were classified according to the classification of TMD suggested by the Japanese Society for Temporomandibular Joint (TMJ)5. They were classified as types 1-5 depending on the area of the major lesion, pathology, symptoms, and radiological results.

Type 1: The major lesion area is the masticatory muscles. It is manifested as muscle tone, myositis, and muscle spasm. Patients primarily experience muscle pain.

Type 2: The major lesion areas are the articular capsule, articular ligaments, and articular disc. It is manifested as the extension and contusion of the articular capsule, ligaments, and articular disc. Patients primarily complain of muscle pain and TMJ pain.

Type 3: The major lesion area is the synovial membrane. It is manifested as the displacement of articular disc, degeneration of articular disc, perforation, and fibrosis. Patients experience TMJ pain as well as a clicking sound. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may show the displacement of the articular disc.

Type 4: The major lesion areas are articular cartilages, articular disc, synovial membrane, mandibular condyle, and mandibular fossa. It is manifested as cartilage destruction, bone resorption, and osteolysis. Patients complain of pain as well as a clicking sound. An X-ray may show bone resorption. MRI may reveal the displacement of the articular disc.

Type 5: Patients who are not included in any of the above groups.

2. Chief complaints

Patients were asked what their chief complaint was for visiting, and their responses were classified into pain, trismus, clicking sound, TMJ discomfort, and bruxism.

3. Level of impairment experienced during daily life (limitation of functions associated with mandibular movement)

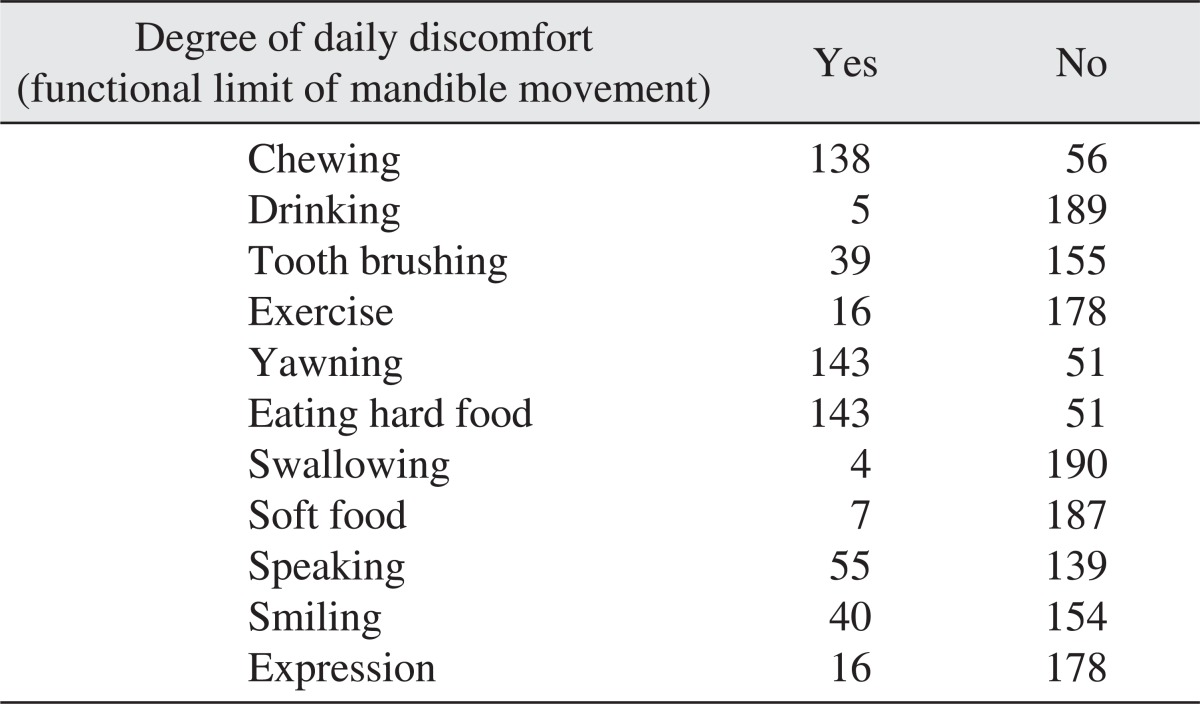

The questionnaire asked whether discomfort was experienced during chewing, drinking, brushing teeth or face washing, exercise, yawning, eating of hard food, swallowing of food, eating of soft food, speaking, smiling or laughing, and routine facial expression, answerable by either "yes" or "no."

4. Depression scale

In the questionnaire, a question that evaluates depression (0-4) was added, and the average was obtained. According to severity, it was classified into three levels: normal, moderate, and severe. In addition, the level of severity of the presented symptoms according to the questionnaire was also evaluated.

5. Physical pain due to somatization (non-specific physical symptoms)

Pain due to somatization was examined; the average value of the responses (0-4) was obtained, and they were classified into 3 levels: normal, moderate, and severe.

6. Graded chronic pain score

Graded chronic pain score: 0 (no pain during the past 6 months), I, II, III, and IV.

Characteristic pain intensity was calculated as the average of the value of visual analogue scale (VAS) described in the 7th, 8th, and 9th questions of RDC×10.

Disability points were calculated as disability days (0-3)+disability score (0-3, the average of the value of VAS described in the 11th, 12th, and 13th questions of RDC×10).

III. Results

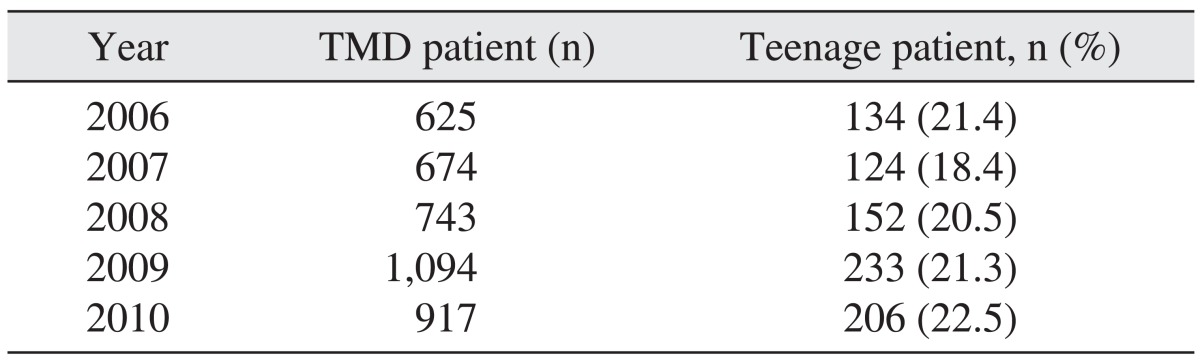

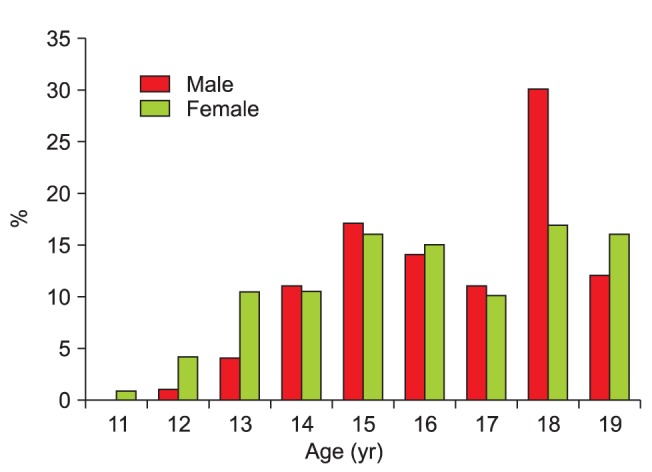

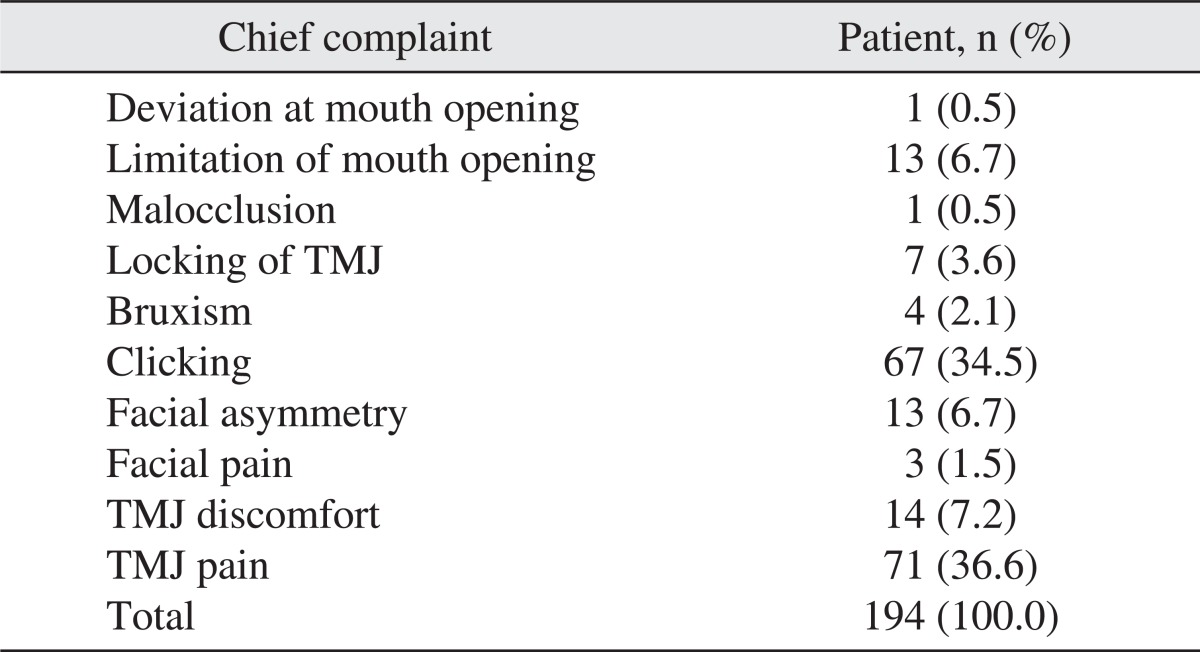

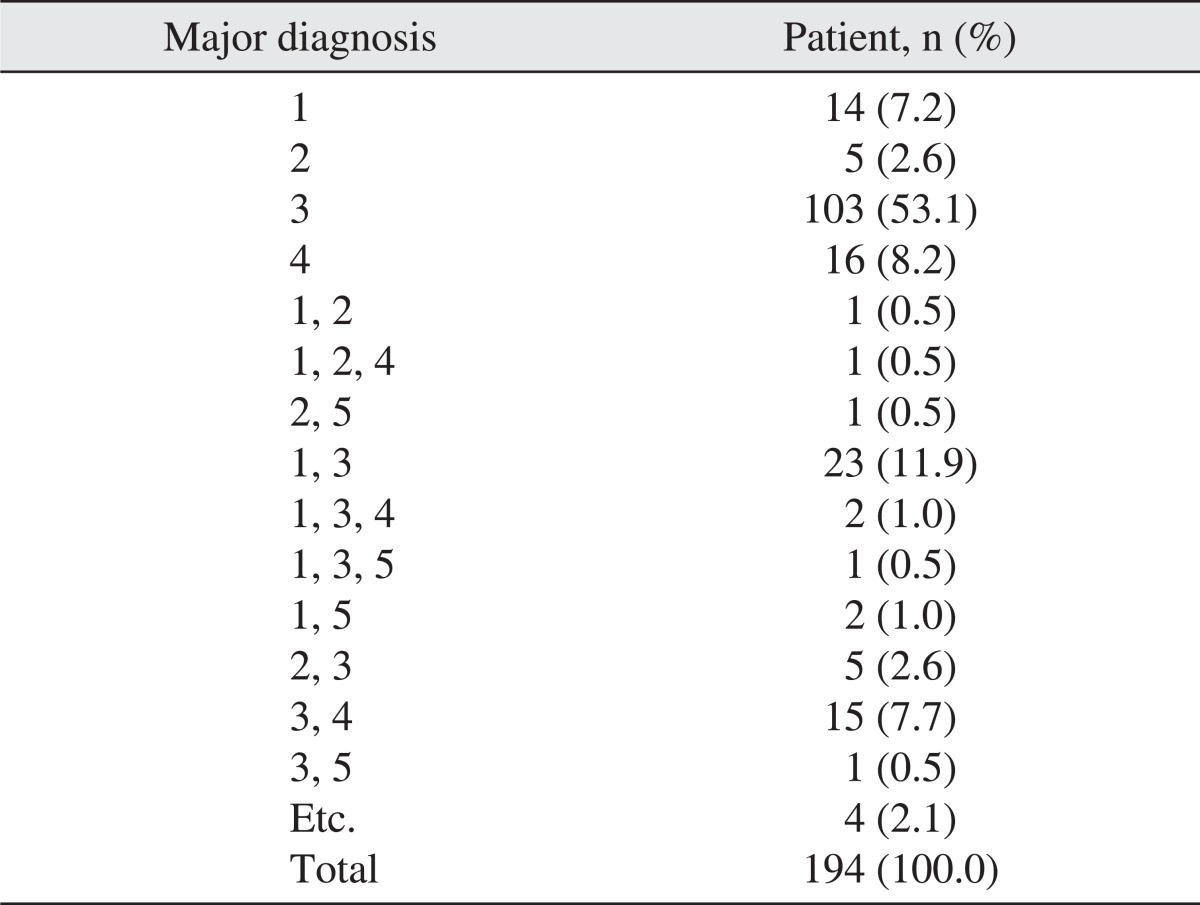

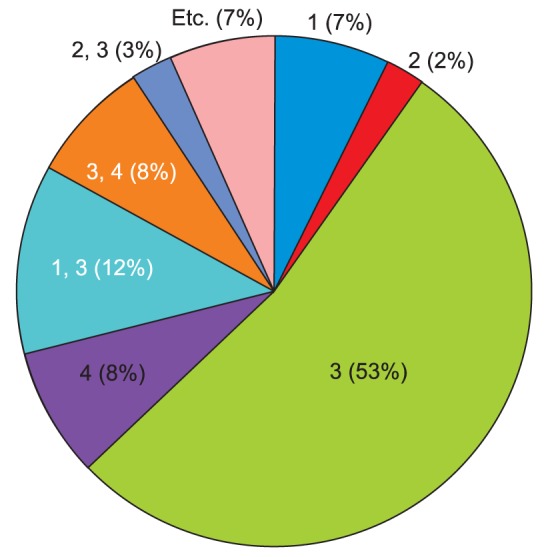

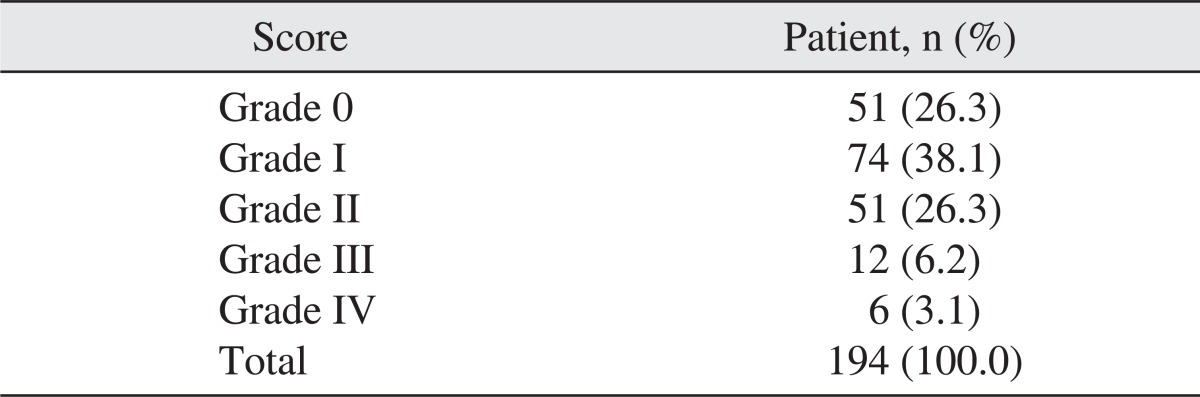

Of a total of 194 subjects who completed the RDC/TMD questionnaire, 77 were male (39.6%) and 117 were female (60.4%); their mean age was 16.2±2.05 years. Among the first-visit patients from 2006 to 2010, approximately 18-22% of TMD patients were teenagers.(Table 2) For the evaluation of teenage patients' distribution according to age, the ratio of patient from 17 years to 19 years was high (53%) in the male group. In the case of the female group, however, patient distribution was relatively constant from 13 years to 19 years.(Fig. 1) At the first visit, the number of patients who visited with chief complaint of clicking sound (34.5%) or TMJ pain (36.6%) was the highest.(Table 3) As a result of the analysis of chief complaint according to sex, the ratio of clicking sound was highest in the male group (34 patients, 44.1%). In the female group, however, the percent ratio of TMJ pain appeared highest among others (49 patients, 41.8%). At the time of classification into the diagnosis groups, the incidence of temporomandibular internal derangement (53%) was the highest.(Table 4, Fig. 2) When the level of impairment during daily life was assessed, patients were found to experience discomfort while chewing, yawning, and eating hard food.(Table 5) In evaluating the depression index, 75.8% of the total subjects were normal, and 12.9% were moderate; 11.3% belonged to the severe group.(Table 6) Additionally, the subjects noted a decrease in energy. Feelings of being tired and "over anxious" were also prominent. Regarding the non-specific physical symptoms (including pain), 66.5% of the subjects were normal, 17.0% were moderate, and 16.5% were severe.(Table 6) When it was examined in more detail, symptoms of "headache," "vertigo or dizziness," and "back pain" were prominent. Regarding non-specific physical symptoms (excluding pain), 70.6% of the subjects were normal, 14.4% were moderate, and 15.0% were severe.(Table 6) Among them, the level of discomfort was high due to "weakness in a part of the body" and "heaviness in the arm or leg." With regard to the graded chronic pain score, high disability (grade III or IV) was shown to be 9.3%.(Table 7) For the comparison of the average of depression index and non-specific physical symptoms including pain and those excluding pain between male and female, there was no statistical significant difference (independent t test, P>0.05).

Table 2.

Annual distribution of patients

(TMD: temporomandibular disorder)

Fig. 1.

Distribution of patients according to age (percent ratio for gender).

Table 3.

Distribution by chief complaint

(TMJ: temporomandibular joint)

Table 4.

Distribution of patients according to diagnosis

Diagnosis type (1-5): classification was performed according to the guidelines of the Japanese Society for Temporomandibular Joint. Total 100% is a result of raising fractions not lower than 0.5 to a unit.

Fig. 2.

Distribution of patients according to diagnosis. Diagnosis type (1-5): classification was performed according to the guidelines of the Japanese Society for Temporomandibular Joint. The diagnosis group whose number of patients was less than 3 was included in the 'Etc.' group.

Table 5.

Degree of difficulty in daily life

Table 6.

Distribution of depression scale and non-specific physical symptoms

*Pain included. **Pain excluded.

Values are presented as number (%).

Table 7.

Graded chronic pain score

IV. Discussion

The chief complaints of TMD are chronic pain, muscular pain during palpation, trismus, and clicking sound. Among them, chronic pain is most common. Chronic pain appears to be associated with psychological, behavioral, and social factors as well as physical lesions. For treatment, behavioral therapy is emphasized in most cases. There has been a trend showing that pressure, sorrow, weakness, and abnormal function manifest abundantly in TMD patients6,7. In our study, chief complaints of pain, clicking sound, and trismus were most frequent among all teenage TMD patients. In other studies, similar results have been reported8.

As a result of classifying the diagnosis groups at first visit, type 3 or cases accompanied with type 3 recorded the highest ratio (76%), similar to the results of previous studies2.

The incidence of TMD has been reported to be high among persons in their 30s-40s9. According to recent studies, the ratio of patients in their teens and 20s makes up 50% of TMD patients, and the onset age of TMD becomes lower7,10. In our study, among the first-diagnosed TMD patients, the ratio of teens was found to be 18-22% annually.

Regarding the ratio of male and female TMD patients, females have been reported to be more prevalent than males by 2-5 times7. According to Magnusson et al.11, the manifestation of temporomandibular symptoms--such as clicking sound, fatigue in the jaw, trismus, and pain during mastication--was higher among females than males. In a study that examined clicking sounds in children and teenagers, Torii12 reported that the rate of manifestation of clicking sound was significantly higher in girls than boys. In our study, 39.6% of the subjects were males and 60.4% were females.

As a result of chief complaint analysis according to sex, our study found that the ratio of clicking at first visit appeared highest in the male group. On the other hand, the ratio of TMJ pain was high in the female group.

Females have been reported to visit hospitals more frequently than males because the former have higher sensitivity to pain. Likewise, due to cultural background, females complaining of pain were deemed more acceptable than males13.

As to the reason for the higher incidence of TMD in females than males, Hatch et al.14 suggested the role of the sex hormone. The hypothesis stated that the value of the sex hormone is associated with the menstrual cycle; thus possibly wielding influences on pain perception. As such, exogenous estrogen should be prescribed. Another study that examined the association of temporomandibular arthritis with females reported that the polymorphism of the estrogen receptor is associated with pain sensitivity15. Nonetheless, whether estrogen is associated with the etiology of TMD is still controversial16. In addition, certain symptoms of TMD--for example, trismus--show a tendency to have high prevalence of a specific estrogen receptor. On the other hand, the association with TMD symptoms has been reported to be not statistically significant; thus, the association of estrogen with the etiology of TMD is deemed to require more investigation17.

The depression index is assessed to evaluate the psychological condition of patients. Non-specific physical symptoms (somatization) are assessed to evaluate pain, fatigue, and level of non-specific symptoms pertinent to the cardiopulmonary circulation system. The chronic pain index is based on the description of the level of pain experienced by patients and impairment of function during daily life due to pain described as VAS and is classified into 5 grades (0-4)18.

Kim et al.19 have reported that, in TMD patients, somatization and TMD may be manifested in close association with the strength of pain and level of impairment. Therefore, comprehensive understanding of emotional pressure experienced by patients and appropriate management of dysfunction are very important for the successful treatment of TMD patients. In our study, 33.5% of patients exhibited moderate to severe non-specific physical symptoms. Chewing was found to require strong force of the masticatory muscles; yawning or eating hard food caused patients great discomfort. In addition, the results of the depression scale show that 24.2% of patients were in the moderate or severe group. At the time of clinical examination, patients who ranked high on the depression scale were deemed to require collaborative treatments with psychologists. The sensitivity of the RDC/TMD Axis II depression scale in the Korean version has been reported to be high; thus, it could be applied to examine the presence or absence of depression symptoms in Korea20.

Several investigators have investigated factors that contribute to the development of TMD. Lee and Kim8 mentioned that bruxism, clenching, chewy food, history of trauma, and pressure were major causes. In particular, when the difference in bruxism and clenching between genders was examined, males showed relatively higher ratio in bruxism, and females, in clenching. Nevertheless, bruxism has also been reported not to be associated with age and gender13. In another study, the incidence of unilateral mastication, sleeping on one side, or tongue or lip biting was found to be higher than bruxism or clenching21. Yet another study reported that the incidence of TMD caused by traffic accidents was lower than yawning and masticatory function, and that chronic pain in the temporomandibular area after traffic accidents was due to psychological factors rather than physical impacts in many cases22. According to Yun and Kim23, major trauma in the facial area should be considered an important causative factor of TMD. Kamisaka et al.24 have also emphasized the association of history of trauma with the manifestation of TMD symptoms. Teenage Koreans, in addition to the task of ego-identity development, are considered to experience high pressure due to the task of overloaded study. Additionally, the way of perceiving problems between teenagers and adults is different. According to a 2009 report of the statistics bureau of the Department of Social Welfare, the ratio of children/teenagers who experienced pressure routinely was "very high" or "high" with 46.5%. It was higher in female students than male students; as they became older, they experienced more pressure25. Similarly, our study showed that the late teens ratio was relatively high in male patients, and that ratio over 15 years was high in female patients. Therefore, pressure may be a closely associated factor that contributes to the development of TMD among teenage patients.

V. Conclusion

The results of our study show that patients experienced great discomfort in the following categories of TMD: chewing, yawning, and eating hard food. The results of chronic pain and depression scale show that 24.2% of the patients were classified under the moderate or severe group. For the graded chronic pain score, high disability (grade III or IV) was seen in 9.3% of the subjects. Among teenage TMD patients, clinical symptoms and psychological pressure were very severe in some patients; thus, they are deemed to require aggressive attention and treatment. Understanding of psychological pressure and appropriate treatments for dysfunction are important and should be considered.

References

- 1.Yang HY, Kim ME. Prevalence and treatment pattern of Korean patients with temporomandibular disorders. Korean J Oral Med. 2009;34:63–79. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim YK, Kim SG, Im JH, Yun PY. Clinical survey of the patients with temporomandibular joint disorders, using Research Diagnostic Criteria (Axis II) for TMD: preliminary study. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2012;40:366–372. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2011.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ko MY, Kim MU. Clinical features of the patients with craniomandibular disorders. J Korean Acad Oral Med. 1993;18:29–41. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dworkin SF, LeResche L. Research diagnostic criteria for temporomandibular disorders: review, criteria, examinations and specifications, critique. J Craniomandib Disord. 1992;6:301–355. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yoshimura Y. The terminology of Japanese Society for Temporomandibular Joint. 1st ed. Tokyo: The Japanese Society for Temporomandibular Joint; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shiau YY, Chang C. An epidemiological study of temporomandibular disorders in university students of Taiwan. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1992;20:43–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1992.tb00672.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chuang SY. Incidence of temporomandibular disorders (TMDs) in senior dental students in Taiwan. J Oral Rehabil. 2002;29:1206–1211. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2842.2002.00968.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee DJ, Kim KS. Epidemiologic study on the patients visited to Dept of Oral Medicine: in the area of Choongnam. J Korean Acad Oral Med. 2006;31:101–111. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Okeson JP American Academy of Orofacial Pain. Orofacial pain: guidelines for assessment, diagnosis, and management. Chicago: Quintessence Pub; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hirsch C, Hoffmann J, Türp JC. Are temporomandibular disorder symptoms and diagnoses associated with pubertal development in adolescents? An epidemiological study. J Orofac Orthop. 2012;73:6–18. doi: 10.1007/s00056-011-0056-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Magnusson T, Egermark I, Carlsson GE. A longitudinal epidemiologic study of signs and symptoms of temporomandibular disorders from 15 to 35 years of age. J Orofac Pain. 2000;14:310–319. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Torii K. Longitudinal course of temporomandibular joint sounds in Japanese children and adolescents. Head Face Med. 2011;7:17. doi: 10.1186/1746-160X-7-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krogstad BS, Jokstad A, Dahl BL, Vassend O. The reporting of pain, somatic complaints, and anxiety in a group of patients with TMD before and 2 years after treatment: sex differences. J Orofac Pain. 1996;10:263–269. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hatch JP, Rugh JD, Sakai S, Saunders MJ. Is use of exogenous estrogen associated with temporomandibular signs and symptoms? J Am Dent Assoc. 2001;132:319–326. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2001.0174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kang SC, Lee DG, Choi JH, Kim ST, Kim YK, Ahn HJ. Association between estrogen receptor polymorphism and pain susceptibility in female temporomandibular joint osteoarthritis patients. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007;36:391–394. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2006.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.List T, Wahlund K, Wenneberg B, Dworkin SF. TMD in children and adolescents: prevalence of pain, gender differences, and perceived treatment need. J Orofac Pain. 1999;13:9–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim BS, Kim YK, Yun PY, Lee E, Bae J. The effects of estrogen receptor α polymorphism on the prevalence of symptomatic temporomandibular disorders. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2010;68:2975–2979. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2010.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Plesh O, Sinisi SE, Crawford PB, Gansky SA. Diagnoses based on the Research Diagnostic Criteria for Temporomandibular Disorders in a biracial population of young women. J Orofac Pain. 2005;19:65–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim C, Shin ES, Chung JW. Impacts of depression, somatization, and jaw disability on graded chronic pain in TMD patients. J Korean Acad Oral Med. 2005;30:353–360. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Roh HS, Lim HS, Chung SC. Reliability, validity, sensitivity and specificity of the Korean version of research diagnostic criteria for temporomandibular disorders axis II depression scale. J Korean Acad Oral Med. 2004;29:421–433. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Helkimo M. Studies on function and dysfunction of the masticatory system. II. Index for anamnestic and clinical dysfunction and occlusal state. Sven Tandlak Tidskr. 1974;67:101–121. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ferrari R, Leonard MS. Whiplash and temporomandibular disorders: a critical review. J Am Dent Assoc. 1998;129:1739–1745. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1998.0144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yun PY, Kim YK. The role of facial trauma as a possible etiologic factor in temporomandibular joint disorder. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2005;63:1576–1583. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2005.05.318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kamisaka M, Yatani H, Kuboki T, Matsuka Y, Minakuchi H. Four-year longitudinal course of TMD symptoms in an adult population and the estimation of risk factors in relation to symptoms. J Orofac Pain. 2000;14:224–232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim J, Kim SC, Yoo SK, Shin AW. Factors influencing stress levels of adolescents: with a focus on the impact of positive self-concept and self-confidence. Korean J Youth Stud. 2011;18:103–126. [Google Scholar]