To understand how fibroblasts migrate in normal wound healing and pathologies like fibrosis, we must decipher how they navigate the fibrillar matrices they are also responsible for depositing and maintaining.

Abstract

Fibroblast migration is essential to normal wound healing and pathological matrix deposition in fibrosis. This review summarizes our understanding of how fibroblasts navigate 2D and 3D extracellular matrices, how this behavior is influenced by the architecture and mechanical properties of the matrix, and how migration is integrated with the other principle functions of fibroblasts, including matrix deposition, contraction, and degradation.

Fibroblasts are cells of the mesenchyme, widely distributed throughout the organs of the human body, tasked primarily with secreting and maintaining the extracellular matrix. Despite their relatively homogeneous appearance, they can be characterized by systematic differences in gene expression patterns that correlate with their anatomical site of isolation (17, 112) and position along developmental anterior-posterior and proximal-distal axes, as well as their dermal vs. nondermal sites of origin (99). These findings suggest that fibroblasts take up their relative positions in the body during development and are confined to relatively local domains thereafter, although one cannot altogether exclude local influences that plastically alter fibroblast characteristics. The spatial differences in fibroblast gene expression function as a source of positional memory for neighboring epithelial cells, engaging in reciprocal interactions to ensure appropriate patterning during wound healing or to maintain homeostasis (100). In addition to resident fibroblasts, there is also evidence that cells with fibroblast-like characteristics can be derived from circulating cells (34) and from epithelial and endothelial sources (56, 118), particularly in disease or wound-healing contexts. However, there is strong evidence that locally derived resident mesenchymal cells are activated to proliferate and migrate during wound healing or fibrosis and that such locally derived cells play an important role in these processes (45, 48, 101, 118, 121). Thus understanding how fibroblasts navigate the extracellular matrix in their local tissue environment is a major question relevant to understanding injury responses, regenerative healing, and fibrosis.

In additional to spatial variations in gene expression, fibroblasts also exist along a differentiation continuum, and populations of cells likely include a variety of subclassifications. The best known of these is the myofibroblast, which is classically defined by the expression of the contractile protein α-smooth muscle actin (45). Definitive markers to positively identify and subclassify fibroblasts remain elusive, hence they are often defined by their absence of other definitive markers along with the presence of relatively nonspecific markers, such as vimentin and S100a4 (FSP-1) (114). More definitive insight into fibroblast heterogeneity and origin should come from lineage tracing studies (98), which are already identifying fibroblast subpopulations important in injury repair and fibrosis (18, 101).

Despite the variations in fibroblast subpopulations and the subtle differences in fibroblasts isolated from various organs and tissues, these cells exhibit many overriding similarities in appearance and function and are often studied interchangeably from across different tissues and sites of interest. Fibroblasts are easily isolated and grown in culture from many tissues, and the spontaneously immortalized 3T3 fibroblast cell line, originally derived from mouse embryo (120), is widely used in basic cell biology studies. Thus there is a long history of using cultured fibroblasts for routine investigation of cell and molecular biology, in particular their motile behaviors (e.g., Refs. 1, 2, 10, 41, 119, 123, 124). More recently, it has become apparent that the study of these cells in the artificial environment of the rigid 2D culture dish may strongly influence important behaviors of these cells and fail to capture some important aspects of how these cells behave within the tissues of the human body (27), echoing concepts first explored more than 30 years ago (9, 23, 40). This review highlights the differences in fibroblast function that emerge across extracellular matrices spanning simple (2D) to intact tissue matrices, using migration as widely studied and physiologically critical focus that illuminates the important interactions between the fibroblast and the extracellular matrix environment.

Fibroblast Migration in Two Dimensions

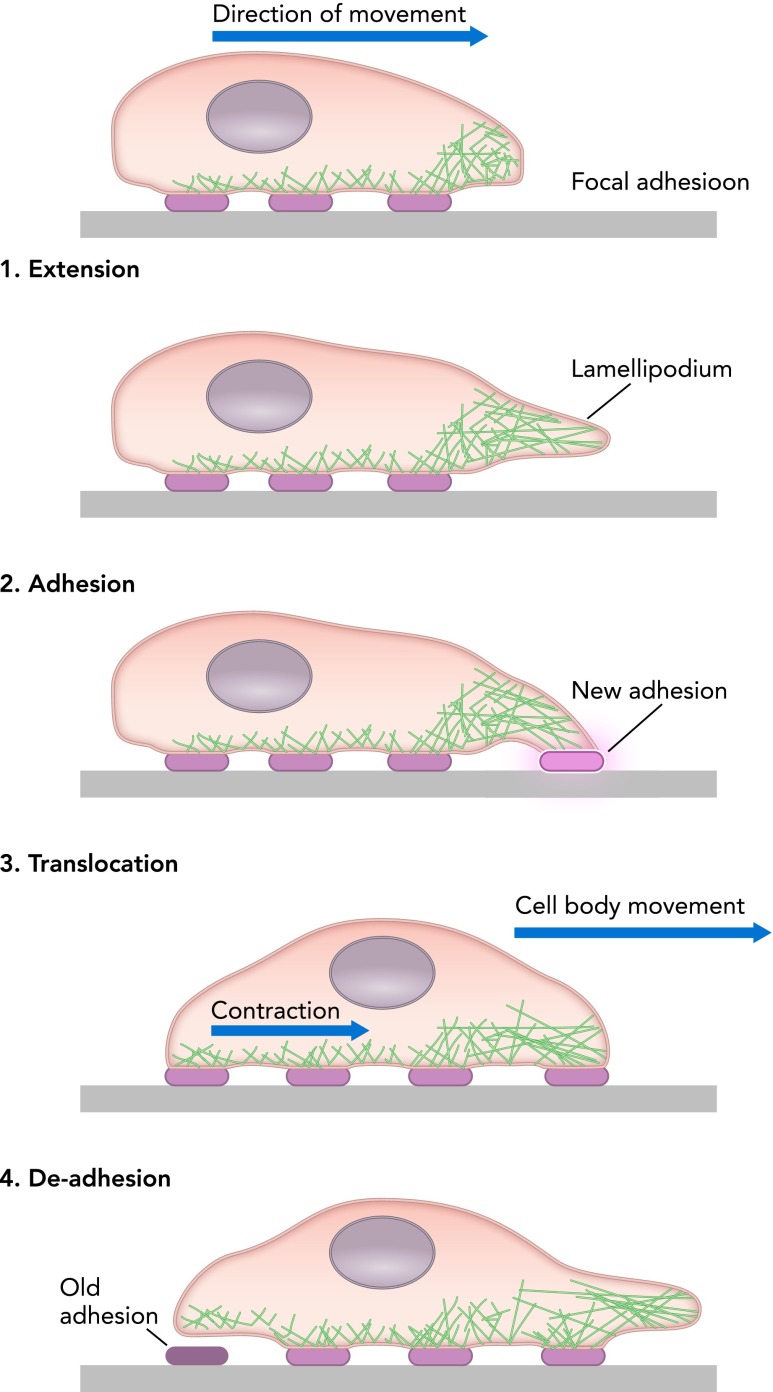

Although fibroblasts reside throughout many tissues of the human body, they still must be capable of motile function to fulfill their roles in tissue homeostasis and wound repair, traversing local tissue environments as needed to degrade, repair, or remodel the extracellular matrix. In standard cell culture approaches, fibroblasts are grown on 2D surfaces, typically glass or plastic, with surfaces modified to encourage cell and protein attachment. Such an arrangement is optimal for a number of microscopic imaging techniques, allowing cells to be visualized and followed over time as they migrate, either spontaneously or in response to chemotactic gradients or other biochemical stimuli that perturb motility. However, such settings also impose nonphysiological constraints, restricting cell spreading and movement to an artificially flat 2D surface. Nevertheless, such systems proved instrumental in developing current concepts for understanding 2D cell motility. Briefly, fibroblast movement requires protrusion of cellular processes such as lamellelapodia or filopodia, adhesion to the underlying substrate, translocation of the cellular contents, and retraction of the cell at the trailing edge (62) (FIGURE 1). All of these steps rely on cell adhesion to the underlying matrix, principally through integrins, transmembrane proteins that bind specific epitopes on extracellular matrix proteins and cluster together in multiprotein adhesion complexes (29, 132). More than 100 additional proteins in the “integrin adhesome” facilitate signaling from such adhesions and connect the extracellular matrix to the intracellular cytoskeleton (29, 132). For the this process to be integrated and result in net movement, the cell must exhibit polarity, or organization from front to back (97). Robust polarity results in persistent migration, while variations in polarity result in more random and less effective migration, despite high rates of instantaneous speed (90). Interestingly, migration rates are highly sensitive to adhesive strength (85), with an optimal adhesive environment supporting maximal migration, and too weak or too strong adhesive environments preventing formation of new adhesions or retraction of trailing adhesions, respectively. Thus it has been clear for some time that the rate of cell migration is not invariant but rather adapts to physical cues in the extracellular environment.

FIGURE 1.

Schematic representation of the steps in 2D cell migration, including extension of a lamellapodium, formation of a new adhesion, translocation of the cell body, and de-adhesion and retraction at the trailing edge

Reproduced from Ref. 61 with permission from IOP Publishing.

Substratum Mechanical Properties and 2D Migration

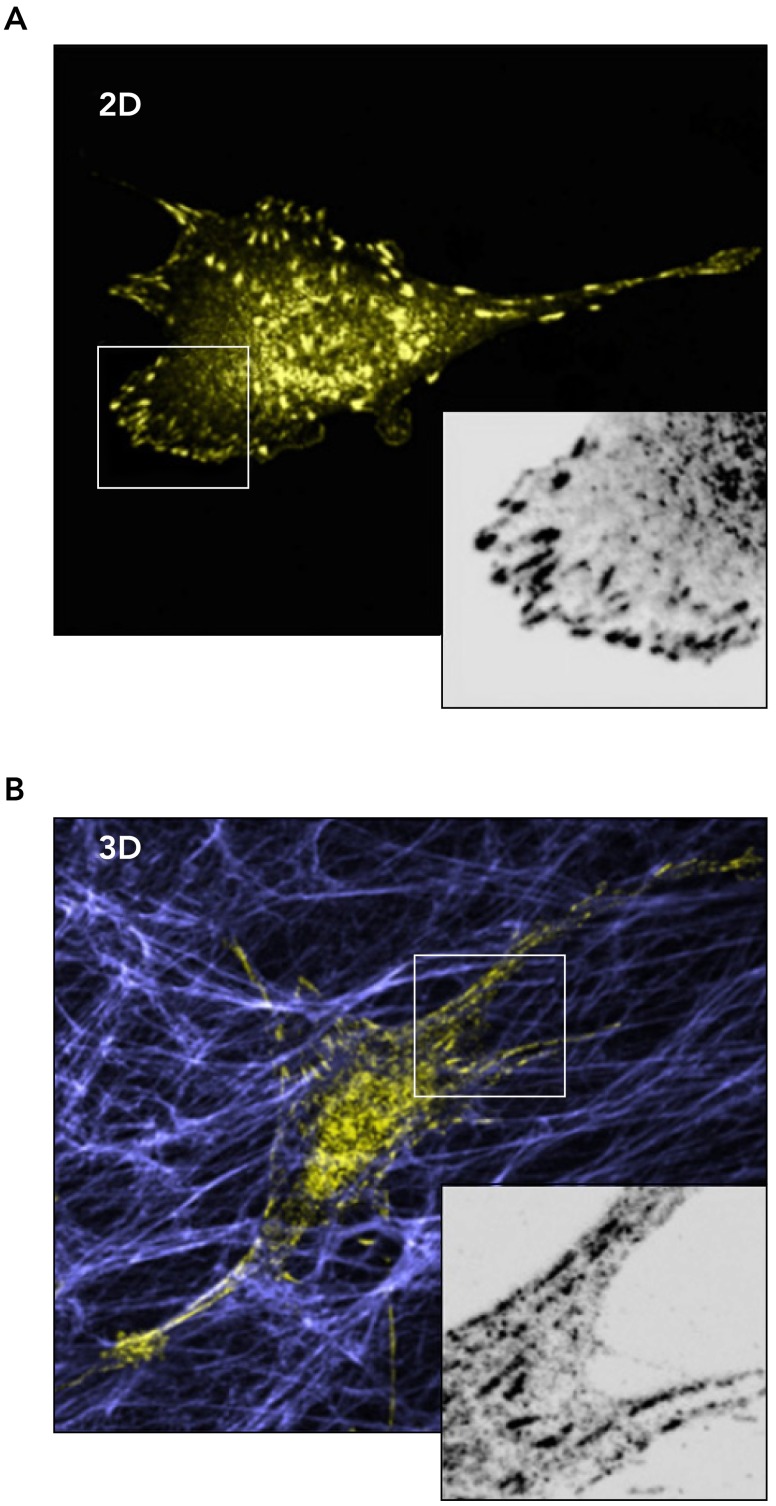

To move, the fibroblast must exert forces against the underlying matrix. Such physical transmission of force across the cell membrane was clearly demonstrated in early work using fibroblasts cultured on compliant silicone substrates, which revealed the ability of cells to mediate wrinkling of the surface of the underlying substrate (41). The scope and precision with which elastic cell culture substrates could be produced was expanded by the use of polyacrylamide hydrogels, which could be tuned over a large range of elastic modulus through variation in acrylamide and bis-acrylamide concentration (88). These methods helped to reveal the magnitude and localization of cell-generated forces present in migrating cells (10, 20, 89). But perhaps more importantly, they demonstrated that, not only do cells deform the substrate, but the adhesive structures of the cell are sensitive to the deformability of the substrate, resulting in vast differences in cell-matrix adhesion structure and dynamics, and alterations in cell morphology and cell migration as underlying substrate deformability changes (33, 66, 88) (FIGURE 2). Subsequent work showed that, not only do cells sense deformability of the underlying substrate, they also respond to spatial gradients in deformability in such a way that net cell migration is directed toward regions of decreasing deformability (increasing elastic modulus), a process termed durotaxis (67). This behavior has subsequently been shown to depend critically on the steepness of the spatial gradient in matrix stiffness (50, 66). Recent studies have demonstrated that dynamic fluctuations in cell-matrix adhesion “tugging” forces are essential for sampling the local mechanical environment (93) and that phosphorylation and polarized function of nonmuscle myosin II is required for polarization and directed migration of cells across a stiffness gradient (94).

FIGURE 2.

Changes in fibroblast morphology, adhesion, cytoskeleton, and motility as a function of underlying substrate stiffness

A: immunostaining of the focal adhesion protein vinculin in human lung fibroblasts cultured on collagen I-coated polyacrylamide gel surfaces of indicated shear modulus for 5 days showing gradual transition of focal adhesions from round (arrows) to elongated fibrillar shape (arrowheads). Bar = 10 μm. B: the cytoskeletal protein α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA; green) is progressively incorporated into F-actin stress fibers (red), which themselves become increasingly distinct and organized as the underlying matrix stiffness increases (Liu F, Tschumperlin D, unpublished observations). Bar = 50 μm. C: fibroblast migration speed and persistence vary with underlying matrix stiffness, as measured with time-lapse video microscopy. Error bars indicate SD from 12 cells for each condition from two independent experiments. D: individual fibroblast migration tracks obtained from time-lapse video microscopy as in C. Digital images were taken every 2 min for a total of 5 h per experiment. Each wind rose plot shows centroid tracks from 7 to 10 representative cells from each indicated stiffness region, with the initial position of each track superimposed at a common origin. Bars = 50 μm. Reproduced from Ref. 66 with permission from Rockerfeller University Press.

In addition to effects on migration, the mechanical properties of the substrate broadly alter the function of fibroblasts, including changes in the magnitude of traction forces generated (70), organization of α-smooth muscle actin into contractile stress fibers (33, 49) (FIGURE 2B), and the closely linked ability to activate TGF-β from a latent matrix-bound state (126), along with alterations in the overall transcriptional profile and factors secreted by the cells (65, 66). Increasing matrix stiffness also promotes fibroblast proliferation while limiting apoptosis (66), further amplifying the effect of durotaxis on the relative distribution of fibroblasts across a gradient in mechanical properties. All of these functional responses play out across a range of mechanical properties observed in normal and diseased tissues, including normal and fibrotic lung (12, 13, 66), liver (31), and intestinal (54) tissue, as well as in normal and malignant breast tissue (86), spanning shear modulus values from <100 Pa to >100 kPa. In addition to altering cell function, the changes in substrate mechanical properties also fundamentally alter cellular responses to biochemical perturbations (14, 70, 75, 76). Taken together, these observations suggest that tissue-specific differences in matrix mechanical properties may influence local fibroblast function and that pathological changes in matrix mechanical properties associated with impaired wound healing or fibrotic diseases may promote fibroblast activation, fibroproliferation, and net matrix accumulation (12, 49, 66, 133).

Some caution is warranted in interpretation of these studies, however. Although the 2D matrices of defined stiffness appear to capture important aspects of fibroblast biology relevant for their function in native tissue matrices, it is also clear that specific functions are highly dependent on additional aspects of matrix dimensionality and topography (83). For example, sandwiching fibroblast between two compliant hydrogels, removing the artificial polarity of 2D culture, and providing dorsal and ventral cell adhesions dramatically alters fibroblast morphology and cell-matrix adhesions (11). Thus ongoing efforts to study fibroblast migration and function in 3D matrix systems offer important and physiologically relevant insights.

Fibroblast Migration in 3D Matrices

To study fibroblast migration and function within 3D matrices that better replicate aspects of the physiological environment, cells have been extensively studied in reconstituted ECM hydrogels, most commonly composed of purified type I collagen (37, 87). Collagen I can be acid- or pepsin-extracted from collagen-rich tissues, such as tendon, and stored in solution. At physiological temperature and pH, collagen spontaneously undergoes fibrillogenesis (formation of linear fibers from collagen monomers) and forms a hydrogel composed of a loose meshwork of collagen fibers, with the remainder of the structure occupied by fluid (23). The microstructure of the collagen gel is sensitive to the temperature, pH, ionic strength, ion stoichiometry, and monomer concentration used during gelation (95, 96, 102). To study cell interactions with such model matrices, fibroblasts can be added to hydrogels after gelation or they can be added during gelation to embed them within the 3D fibrillar meshwork.

Fibroblast migration within such 3D fibrous matrices has been shown to differ substantially from that across 2D surfaces. For instance, migration within 3D can be faster and more uniaxial than that observed across 2D surfaces (22). Intriguingly, these 3D migration characteristics can be recapitulated by patterning 2D surfaces such that adhesion and migration are constrained to thin straight lines, effectively reducing the surface interactions between cells and substrate from 2D to 1D (22). Similarly, microtopographical cues can modify migration patterns such that cells migrating across a complex (although not flat) 2D surface effectively behave as if in a 3D matrix (32). Such observations suggest that cellular migration through loosely organized 3D fibrillar matrices may effectively proceed by 1D migration along matrix fibers.

Controversy has emerged over whether cells migrating within 3D matrices completely avoid the formation of focal adhesions essential for 2D migration (26, 60). Although contradictory evidence for and against clustering of adhesion proteins such as paxillin can be seen in cells migrating within 3D matrices, the more striking finding is that knockdown of adhesion proteins such as talin and p130Cas, or genetic deficiency in the adhesion protein vinculin, can have opposite effects on migration speed and persistence in 3D vs. 2D contexts (26, 74). Moreover, cell speed in 3D migration strongly correlates with the growth rate of pseudopodial protrusions (26), a correlation that is absent in 2D migration (97). In addition, the polarity so important for 2D migration, including polarized activation of Rac, Cdc42, and phosphatidylinositol-3,4,5-trisphosphate, is absent in fibroblasts undergoing 3D migration (91). These results demonstrate that, not only is the character of 3D migration distinct from that on 2D, but so too is the functional effect of individual proteins and signaling cascades involved in cell-matrix adhesions. Physiological 3D collagen also promotes the formation of a newly described adhesion structure, the linear invadosome (55), which supports matrix invasion and shares some features with conventional invadosomes observed in 2D experimental culture models (21). As discussed below, these structures may be critical to orienting local proteolytic activity in support of migration through dense fibrillar matrices.

Although such findings hint at important distinctions in 2D and 3D migration, other observations document conserved principles that govern migration in both contexts. For instance, 3D collagen matrices can be fabricated with spatial gradients in both mechanical properties and ligand density, and, similar to effects observed in 2D systems, fibroblasts in these 3D gradients are also redistributed over time to regions of high stiffness and ligand density (38). Thus some core physical and mechanosensitive aspects of migration appear to be conserved across 2D and 3D matrices.

Although reconstituted 3D collagen matrices have been favored for their physiological relevance, the distinction between acid- and pepsin-extracted collagen as source material is an important one that has profound implications for our understanding of how cells migrate through fibrillar 3D matrices. Critically, pepsin extraction removes the nonhelical telopeptides situated at the NH2- and COOH-terminal ends of native collagen molecules. These telopeptides exert an important influence on the process of fibrillogenesis and support collagen cross-link formation that stabilizes the fiber architecture of collagen hydrogels (24, 30, 110, 128). Thus, although little or no difference can be observed at the light microscope level in hydrogels formed from acid- and pepsin-extracted collagen, important differences in fibroblast invasion and migration can be observed. For instance, invasion of telopeptide-intact (acid-extracted) 3D collagen matrices by fibroblasts demonstrates an absolute requirement for matrix metalloprotease (MMP)-14 (46, 104–106), a cell-surface localized metalloprotease also known as membrane type (MT) 1-MMP (51), with potential compensatory roles for MT2-MMP and MT3-MMP in fibroblasts genetically deficient in MT1-MMP expression (47). In contrast, there is no need for MT1-MMP in migration through hydrogels formed from pepsin-extracted collagen (107), and in fact these matrices can be efficiently invaded by fibroblasts in the presence of a broad spectrum inhibitor of matrix metalloproteases, indicating that collagen extraction methods critically influence the need for proteolytic machinery. To understand these differences, it is useful to consider that, as the density of fibrillar matrices increases, the spaces available for migration drops below the size of invading cells. Thus the cells must either deform the architecture of the surrounding matrix fibrils to invade (78) or engage proteolytic machinery to degrade the matrix and generate paths suitable for invasion. The local need for matrix degradation has been confirmed in native cross-linked but not pepsin-extracted collagen matrices, using a molecular biosensor that fluoresces after cleavage (by MMP-2, -9, or -14) of a peptide site present in interstitial collagen (84). Such work confirms the localization of proteolytic activity at the leading edge of matrix invading cells and demonstrates the specific circumstances under which local matrix degrading activity is essential for 3D invasion and migration. Further testing of these concepts using invasion of the chicken chorioallantoic membrane (CAM), a type I collagen-rich ECM barrier commonly used to study invasive processes (6, 58), confirmed the necessary role for MT1-MMP in fibroblast invasion (106), expanding this concept to a true tissue-derived matrix. Interestingly, studies of tumor cell invasion have shown an alternative mode of amoeboid migration in fibrillar matrices, in which cells squeeze through small gaps by forming bleb-like structures that push fibers out of the way without the need for proteolytic activity (8, 92), although there is as yet no evidence for such amoeboid migration by fibroblasts navigating 3D matrices, supporting an essential role for local proteolysis in the navigation of dense, cross-linked fibrillar matrices.

Although matrices derived from acid-extracted collagen preserve the physiologically relevant dependency on local proteolytic activity, there are additional limitations that are important to consider with such systems. For instance, although these reconstituted matrices offer the experimentalist the advantage of being composed of a relatively homogenous distribution of fibrillar proteins, they fail to capture the molecular and topological complexity present in intact tissues (12). Strikingly, cells within complex matrices may navigate along preformed paths (107) or along pre-aligned bundles of ECM (108), features not typically observed in homogenous reconstituted ECMs upon polymerization. Although fibroblasts will reorganize the collagen fibrils in ECM hydrogels over time into oriented bundles, perhaps mimicking aspects of bundled fibers found in intact tissue, such cell-mediated changes also profoundly alter the local ligand density and matrix architecture (117), and likely the mechanical properties of the matrix as well (115), and do so in a spatially heterogeneous fashion that offsets the original advantage of a highly controlled starting condition present in such systems.

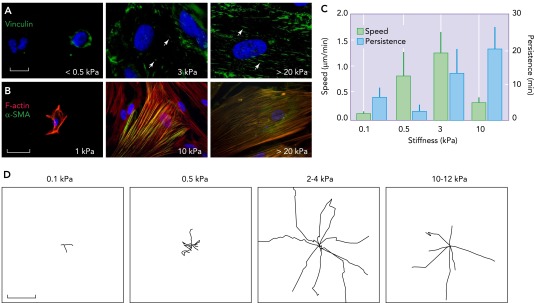

A second limitation revolves around the use of a single protein (e.g., collagen I) for matrix formation, which vastly understates the molecular complexity present in intact tissues, and may omit critical contributions from other matrix proteins, which can be present in normal tissues or increased in abundance in diseased tissues (27, 87). One intermediate step toward overcoming these limitations is to use cells themselves to generate 3D matrices for further study (4, 7, 19) (FIGURE 3). For instance, fibroblasts will produce their own pericellular matrix composed largely of glycosaminoglycan components hyaluronic acid and heparan sulfate and protein components fibronectin and collagen (43). Long-term culture of fibroblasts in the presence of ascorbic acid promotes cellular deposition and covalent cross-linking of a collagen-rich matrix (4, 35). Cell migration in such matrices is faster and more linear than in the random hydrogels of purified ECM (39). Micromechanical measurement techniques can also be used to measure the stiffness of cell-derived matrices (4, 91, 113), relating the studies of cell behavior on these matrices back to the concept of 2D mechanical stiffness responses summarized above. Intriguingly, the 3D mode of migration in such cell-derived matrices appears to vary depending on specific aspects of the mechanical environment, such as its linear or nonlinear elastic behavior (91).

FIGURE 3.

Comparing adhesion structures in 2D culture with those in 3D cell-derived matrices

3T3 mouse embryonic fibroblasts expressing GFP-paxillin migrating on a 2D fibronectin-coated rigid surface (A) or through a 3D cell-derived matrix (B). Insets: magnifications of GFP-paxillin localization and adhesion formation in squared areas. Fibroblasts in 3D adopt a more elongated morphology adapted to the fibrillar structure of the cell-derived matrix. Adhesive structures are located all around the cell body and are aligned with the fibers (B). Reproduced from Ref. 52 with permission from Elsevier.

Although cell-derived matrices offer potential for novel insights and physiological relevance, they also suffer from important limitations. Such limitations include local and batch variability in cell-derived matrices and challenges with maintenance and manipulation of such culture systems (27). In addition, these cultures are derived from a single cell type growing in isolation, omitting the influence of other cell types found in intact tissues, and the culture conditions for the formation of such cell-derived matrices typically begin with rigid plastic substrates as a starting point. Fibroblast-derived matrices synthesized under such culture conditions, including high levels of serum and omitting other paracrine signaling partners, may be most representative of matrices formed during wound healing, although improvements in defined culture methods may be able to offer superior control of the cell-derived matrix composition and architecture (4). On a positive note, the development of controlled methods for studying cell-derived matrices offers a unique opportunity to determine whether disease-derived cells produce matrices that are distinct from those produced by “normal” cells, as has been done for cancer-associated fibroblasts (5, 16).

Integrating 3D Migration with Matrix Contraction and Degradation

Although migration offers a clear example of how cell function is altered by matrix characteristics, other important fibroblast functions also diverge from their behavior on 2D surfaces when studied in 3D matrices. For instance, although fibroblasts typically proliferate rapidly in rigid 2D cultures, they are largely quiescent on collagen gels that are floating and allowed to freely contract (28, 103). Such differences in proliferation might reflect the altered density of ECM ligands in 3D hydrogels. Sparse hydrogels of reconstituted ECM are also highly deformable (63, 87), suggesting that limited proliferation may relate in part to observations from 2D studies that highly deformable matrices dramatically limit fibroblast spreading and proliferation (66, 75, 76). When 3D matrices are constrained by peripheral anchorage or attachment to a surface so that their outer boundary is maintained, rather than allowed to freely contract, cells compact the matrix over time in the free dimension. And although short-term culture leads to net matrix degradation in this setting, longer-term culture allows newly synthesized collagen to be deposited into and augment that matrix (81). Fibroblasts maintained in such “stressed” matrices take on a synthetic phenotype compared with cells in “relaxed” floating matrices (57), in a fashion similar to that seen with fibroblast phenotypes across matrices with variations in 2D matrix stiffness (66). Although challenging to quantify, the integrated effect of such cell-mediated effects on matrix mechanics can be measured in such 3D systems (63, 71, 72). Interestingly, allowing cells to remodel the matrix in a stressed state leads to a relatively organized ECM that promotes fibroblast growth factor responsiveness, whereas cell-mediated contraction of freely floating matrices results in a more disordered matrix and limits growth factor responsiveness of resident cells (80). Over time, with appropriate boundary conditions, fibroblasts locally reorient and align matrix fibrils, and fibroblast morphology and matrix adhesions will also reorient and mature, suggesting that the cells remodel the originally sparse matrix into dense aligned bundles, effectively altering their relationship with the matrix back toward that observed on stiffer 1D or 2D matrices (117).

How then do cells regulate the switch between migration through the matrix and contraction of the matrix? These processes employ largely overlapping components of the same machinery (37, 40, 73, 77, 111), although with subroutines specific to particular aspects of matrix remodeling (15). Such issues become critical in processes like wound healing, in which fibroblasts must first migrate into the provisional matrix of the wound bed but then transition to a contractile function to assist with wound closure and tissue regeneration (44, 45). One likely explanation is that alterations in cell-matrix adhesions are essential to this transition, shifting the cells from relatively weak adhesions that foster migration to strong adhesions required for generation of cytoskeletal tension and tissue remodeling. How such a transition in adhesion function is triggered is likely complex, but the physical state of the matrix may play an important role. For example, it has been postulated that the transition from migration to matrix contraction can be explained by the relative pliability of the matrix (37). By analogy, if the matrix moves under cell-mediated traction force, the cell remains stationary as on a treadmill, while the matrix is compacted. On the other hand, if the matrix fails to move under the influence of cellular tractions, these forces can translate into movement of the cell body.

Intriguingly, there is evidence that the tractions associated with migratory fibroblasts are indeed sufficient to contract floating collagen gels (37) and may be sufficient to close normal wounds, whereas conversion to the highly contractile myofibroblasts may be specific to late phase of certain wounds that do not heal easily (44) or to pathological fibrosis or scarring (3, 121) under the influence of an abnormally stiffened and cross-linked matrix (31, 33, 44, 66). In addition to such mechanical effects, it seems likely that some aspects of cell polarization remain key to 3D migration (91, 97), since a necessary step in migration is formation of new adhesions at the leading edge and release of adhesions at the trailing edge. Such polarity signals may come from the matrix itself (50, 67, 93, 94) or from the soluble environment (42). Moreover, specific soluble factors may also provide signals that shift fibroblasts between migration and contraction. For example, PDGF potently promotes migration in both 2D (42) and 3D (37, 53) contexts and cell spreading independent of matrix stiffness (36), whereas serum and serum components such as lysophosphatidic acid (LPA) and sphingosine-1-phosphate promote contraction of 3D collagen matrices (53). Although it is appealing to ascribe such definitive effects to soluble factors, it must be acknowledged that our understanding of these effects rests largely on model matrix systems, with in vivo relevance still in question. As a cautionary example, the “matrix contractile” agonist LPA has been shown to play a critical role in a mouse model of lung fibrosis (116) but appears to do so by promoting matrix invasion and migration; similarly, LPA also promotes collagen matrix invasion by HT1080 fibrosarcoma cells through MT1-MMP activation and collagen degradation leading to formation of single-cell invasion tunnels (25). Taken together, these experiments and concepts, while still fragmentary, indicate that changes in matrix density and deformability, along with changes in soluble signaling cues, likely engage a complex regulatory system to control fibroblast migration and matrix contraction. A fully integrated understanding of this critical cellular decision process remains elusive and will be essential in formulating strategies to modulate fibroblast invasion and function across a variety of applications, from tissue engineering to wound healing and therapies directed at scarring and fibrosis.

Basement Membrane Invasion

One area of fibroblast migration that has received less attention but may be of great interest in pathological scarring and fibrosis is that of fibroblast invasion across basement membranes. For example, evidence is accumulating that the pathological remodeling of the lung ECM in pulmonary fibrosis requires a highly invasive fibroblast phenotype (64), with MT1-MMP again likely to play a prominent role in local degradation and invasion of the lung ECM (104). The constrained expression and proteolytic function of MT1-MMP at the cell's leading edge helps to reconcile the invasive process with the overwhelming accumulation of abundant matrix proteins that characterize fibrosis. The process of translocation across the basement membrane, essential to the loss of fibroblast compartmentalization seen in lung fibrosis, may be specifically dependent on integrin ligation by fibronectin (125) or cellular interactions with hyaluronan (64), suggesting a prominent role for the matrix in promoting invasion, but evidence also exists that primary fibroblasts from humans with fibrotic lung disease may already possess an “invasive” phenotype (64). Such observation build on studies showing that normal growth limitations seen when cells are cultured in polymerized 3D collagen gels (109) are somewhat overcome in fibroblasts isolated from the lungs of individuals with pulmonary fibrosis (82, 129, 130). These findings suggest that fibroblasts harvested from fibrotic tissues may have a fundamentally altered relationship with the tissue matrix that promotes the underlying pathology. In contrast to these findings, it has also been shown that several phenotypic traits of fibrotic tissue-derived fibroblasts can be reversed upon growing these cells on a physiologically compliant 2D ECM (69). Such observations, although limited, demonstrate that disease-derived cells retain elements of normal responsiveness to the mechanical environment (69). Clearly, more effort is needed to understand the regulation of basement membrane invasion by fibroblasts, and the relative importance of disease-associated changes in the matrix, and resident cells as drivers of normal and pathological basement membrane invasion. As in the case for 3D collagen gels, the model systems used for study of cell-basement membrane interactions are not without limitations. Such limitations include the use of tumor cells as the typical source of basement membrane preparations and the disorganized and noncross-linked nature of the reconstituted basement membrane hydrogel matrices (107), both of which limit the physiological recapitulation of typical basement membrane structure, composition, and mechanics. And as in the case with 3D collagen gel systems, the ultimate test of physiological insights obtained with such systems will rest on confirmation in intact tissues or organisms.

Fibroblast Function within Tissue Matrices: Paving a Path to the Future?

Although much progress has been made in understanding fibroblast migration and function in 2D and 3D model systems, the ultimate goal remains to decipher how migration occurs within physiological and pathological tissue contexts. No model system can yet recapitulate the molecular and architectural diversity and complexity present in tissue matrices. For example, recent mass spectrometry proteomics studies have illustrated the tremendous number of matrix proteins and matrix-associated proteins (the matrisome) present in normal and tumor-associated tissues (79), and underscored the complex changes that occur in the composition of the extracellular matrix in pathological conditions such as fibrosis (12). To move the study of migration toward physiological settings, intravital imaging approaches, which have been pioneered for the study of tumor cell motility, may provide a unique capability for in situ imaging of fibroblast migration within living tissues (8, 59, 68, 127). Such approaches are not without their own limitations, since they rely on animal models that often fail to replicate aspects of human pathophysiology. Nevertheless, the combination of such intravital approaches with more commonly employed 3D model systems could offer a compelling toolset as the field moves forward in understanding fibroblast interactions with physiological extracellular matrices.

In addition to these approaches, a middle ground is also rapidly emerging that is already providing important insights: the use of tissue-derived matrices for study of cell function. The past several years have seen robust progress in development of methods to study tissue explants (91, 131) and decellularize tissues as a way to isolate matrix preparations for the study of cell function (12, 134). These methods, although still under-development, appear to preserve important features of native tissue architecture and composition. And although such approaches also have limitations with regard to reintroducing cells artificially to the surface of matrices that are modified by processing, along with the loss of tissue tension associated with excision (27), they offer compelling and unique advantages. Chief among these is the capacity to study human tissue matrices and to compare cell function on normal and diseased matrices, which has potential to radically enhance our understanding of fibroblast-matrix interactions in normal and diseased tissues (122). Already, such approaches have demonstrated that fibrotic matrices possess intrinsic capacity to alter fibroblast migration and myofibroblast differentiation (12, 134). When such approaches are combined with already well established 2D and 3D model systems, and nascent efforts directed toward intravital imaging, the stage is set for a quantum advance in our understanding of fibroblast invasion and migration as they occur in physiological and pathophysiological tissue contexts. The integrated observations enabled by these approaches should provide a new understanding of the molecular and cellular processes that drive fibroblast motility through intact tissue matrices, and should ultimately allow new hypotheses to be generated and tested that are directed at controlling fibroblast migration and function in wound healing, fibrosis, and other physiologically relevant contexts.

Footnotes

This manuscript was supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grant HL-092961.

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

Author contributions: D.J.T. drafted manuscript; D.J.T. edited and revised manuscript; D.J.T. approved final version of manuscript.

References

- 1.Abercrombie M. The bases of the locomotory behaviour of fibroblasts. Exp Cell Res Suppl 8: 188–198, 1961 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abercrombie M, Dunn GA, Heath JP. The shape and movement of fibroblasts in culture. Soc Gen Physiol Ser 32: 57–70, 1977 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abraham DJ, Eckes B, Rajkumar V, Krieg T. New developments in fibroblast and myofibroblast biology: implications for fibrosis and scleroderma. Curr Rheumatol Rep 9: 136–143, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ahlfors JE, Billiar KL. Biomechanical and biochemical characteristics of a human fibroblast-produced and remodeled matrix. Biomaterials 28: 2183–2191, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Amatangelo MD, Bassi DE, Klein-Szanto AJ, Cukierman E. Stroma-derived three-dimensional matrices are necessary and sufficient to promote desmoplastic differentiation of normal fibroblasts. Am J Pathol 167: 475–488, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Armstrong PB, Quigley JP, Sidebottom E. Transepithelial invasion and intramesenchymal infiltration of the chick embryo chorioallantois by tumor cell lines. Cancer Res 42: 1826–1837, 1982 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beacham DA, Amatangelo MD, Cukierman E. Preparation of extracellular matrices produced by cultured and primary fibroblasts. Curr Protoc Cell Biol 10: unit 10.9, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beerling E, Ritsma L, Vrisekoop N, Derksen PW, van Rheenen J. Intravital microscopy: new insights into metastasis of tumors. J Cell Sci 124: 299–310, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bell E, Ivarsson B, Merrill C. Production of a tissue-like structure by contraction of collagen lattices by human fibroblasts of different proliferative potential in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 76: 1274–1278, 1979 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beningo KA, Dembo M, Kaverina I, Small JV, Wang YL. Nascent focal adhesions are responsible for the generation of strong propulsive forces in migrating fibroblasts. J Cell Biol 153: 881–888, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beningo KA, Dembo M, Wang YL. Responses of fibroblasts to anchorage of dorsal extracellular matrix receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101: 18024–18029, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Booth AJ, Hadley R, Cornett AM, Dreffs AA, Matthes SA, Tsui JL, Weiss K, Horowitz JC, Fiore VF, Barker TH, Moore BB, Martinez FJ, Niklason LE, White ES. Acellular normal and fibrotic human lung matrices as a culture system for in vitro investigation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 186: 866–876, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brown AC, Fiore VF, Sulchek TA, Barker TH. Physical and chemical microenvironmental cues orthogonally control the degree and duration of fibrosis-associated epithelial-to-mesenchymal transitions. J Pathol 229: 25–35, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brown XQ, Bartolak-Suki E, Williams C, Walker ML, Weaver VM, Wong JY. Effect of substrate stiffness and PDGF on the behavior of vascular smooth muscle cells: implications for atherosclerosis. J Cell Physiol 225: 115–122, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Castella LF, Buscemi L, Godbout C, Meister JJ, Hinz B. A new lock-step mechanism of matrix remodelling based on subcellular contractile events. J Cell Sci 123: 1751–1760, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Castello-Cros R, Khan DR, Simons J, Valianou M, Cukierman E. Staged stromal extracellular 3D matrices differentially regulate breast cancer cell responses through PI3K and beta1-integrins. BMC Cancer 9: 94, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chang HY, Chi JT, Dudoit S, Bondre C, van de Rijn M, Botstein D, Brown PO. Diversity, topographic differentiation, and positional memory in human fibroblasts. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99: 12877–12882, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen L, Acciani T, Le Cras T, Lutzko C, Perl AK. Dynamic regulation of platelet-derived growth factor receptor alpha expression in alveolar fibroblasts during realveolarization. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 47: 517–527, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cukierman E, Pankov R, Stevens DR, Yamada KM. Taking cell-matrix adhesions to the third dimension. Science 294: 1708–1712, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dembo M, Wang YL. Stresses at the cell-to-substrate interface during locomotion of fibroblasts. Biophys J 76: 2307–2316, 1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Destaing O, Block MR, Planus E, Albiges-Rizo C. Invadosome regulation by adhesion signaling. Curr Opin Cell Biol 23: 597–606, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Doyle AD, Wang FW, Matsumoto K, Yamada KM. One-dimensional topography underlies three-dimensional fibrillar cell migration. J Cell Biol 184: 481–490, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Elsdale T, Bard J. Collagen substrata for studies on cell behavior. J Cell Biol 54: 626–637, 1972 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Eyre DR, Paz MA, Gallop PM. Cross-linking in collagen and elastin. Annu Rev Biochem 53: 717–748, 1984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fisher KE, Sacharidou A, Stratman AN, Mayo AM, Fisher SB, Mahan RD, Davis MJ, Davis GE. MT1-MMP- and Cdc42-dependent signaling co-regulate cell invasion and tunnel formation in 3D collagen matrices. J Cell Sci 122: 4558–4569, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fraley SI, Feng Y, Krishnamurthy R, Kim DH, Celedon A, Longmore GD, Wirtz D. A distinctive role for focal adhesion proteins in three-dimensional cell motility. Nat Cell Biol 12: 598–604, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Friedl P, Sahai E, Weiss S, Yamada KM. New dimensions in cell migration. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 13: 743–747, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fringer J, Grinnell F. Fibroblast quiescence in floating collagen matrices: decrease in serum activation of MEK and Raf but not Ras. J Biol Chem 278: 20612–20617, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Geiger B, Yamada KM. Molecular architecture and function of matrix adhesions. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 3: 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gelman RA, Poppke DC, Piez KA. Collagen fibril formation in vitro. The role of the nonhelical terminal regions. J Biol Chem 254: 11741–11745, 1979 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Georges PC, Hui JJ, Gombos Z, McCormick ME, Wang AY, Uemura M, Mick R, Janmey PA, Furth EE, Wells RG. Increased stiffness of the rat liver precedes matrix deposition: implications for fibrosis. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 293: G1147–G1154, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ghibaudo M, Trichet L, Le Digabel J, Richert A, Hersen P, Ladoux B. Substrate topography induces a crossover from 2D to 3D behavior in fibroblast migration. Biophys J 97: 357–368, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Goffin JM, Pittet P, Csucs G, Lussi JW, Meister JJ, Hinz B. Focal adhesion size controls tension-dependent recruitment of alpha-smooth muscle actin to stress fibers. J Cell Biol 172: 259–268, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gomperts BN, Strieter RM. Fibrocytes in lung disease. J Leukoc Biol 82: 449–456, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Grinnell F, Fukamizu H, Pawelek P, Nakagawa S. Collagen processing, crosslinking, and fibril bundle assembly in matrix produced by fibroblasts in long-term cultures supplemented with ascorbic acid. Exp Cell Res 181: 483–491, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Grinnell F, Ho CH. The effect of growth factor environment on fibroblast morphological response to substrate stiffness. Biomaterials 34: 965–974, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Grinnell F, Petroll WM. Cell motility and mechanics in three-dimensional collagen matrices. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 26: 335–361, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hadjipanayi E, Mudera V, Brown RA. Guiding cell migration in 3D: a collagen matrix with graded directional stiffness. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton 66: 121–128, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hakkinen KM, Harunaga JS, Doyle AD, Yamada KM. Direct comparisons of the morphology, migration, cell adhesions, and actin cytoskeleton of fibroblasts in four different three-dimensional extracellular matrices. Tissue Eng Part A 17: 713–724, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Harris AK, Stopak D, Wild P. Fibroblast traction as a mechanism for collagen morphogenesis. Nature 290: 249–251, 1981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Harris AK, Wild P, Stopak D. Silicone rubber substrata: a new wrinkle in the study of cell locomotion. Science 208: 177–179, 1980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Haugh JM, Codazzi F, Teruel M, Meyer T. Spatial sensing in fibroblasts mediated by 3′ phosphoinositides. J Cell Biol 151: 1269–1280, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hedman K, Kurkinen M, Alitalo K, Vaheri A, Johansson S, Hook M. Isolation of the pericellular matrix of human fibroblast cultures. J Cell Biol 81: 83–91, 1979 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hinz B, Mastrangelo D, Iselin CE, Chaponnier C, Gabbiani G. Mechanical tension controls granulation tissue contractile activity and myofibroblast differentiation. Am J Pathol 159: 1009–1020, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hinz B, Phan SH, Thannickal VJ, Galli A, Bochaton-Piallat ML, Gabbiani G. The myofibroblast: one function, multiple origins. Am J Pathol 170: 1807–1816, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hotary K, Allen E, Punturieri A, Yana I, Weiss SJ. Regulation of cell invasion and morphogenesis in a three-dimensional type I collagen matrix by membrane-type matrix metalloproteinases 1, 2, and 3. J Cell Biol 149: 1309–1323, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hotary KB, Yana I, Sabeh F, Li XY, Holmbeck K, Birkedal-Hansen H, Allen ED, Hiraoka N, Weiss SJ. Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) regulate fibrin-invasive activity via MT1-MMP-dependent and -independent processes. J Exp Med 195: 295–308, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hoyles RK, Derrett-Smith EC, Khan K, Shiwen X, Howat SL, Wells AU, Abraham DJ, Denton CP. An essential role for resident fibroblasts in experimental lung fibrosis is defined by lineage-specific deletion of high-affinity type II transforming growth factor beta receptor. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 183: 249–261, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Huang X, Yang N, Fiore VF, Barker TH, Sun Y, Morris SW, Ding Q, Thannickal VJ, Zhou Y. Matrix stiffness-induced myofibroblast differentiation is mediated by intrinsic mechanotransduction. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 47: 340–348, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Isenberg BC, Dimilla PA, Walker M, Kim S, Wong JY. Vascular smooth muscle cell durotaxis depends on substrate stiffness gradient strength. Biophys J 97: 1313–1322, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Itoh Y, Seiki M. MT1-MMP: a potent modifier of pericellular microenvironment. J Cell Physiol 206: 1–8, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jayo A, Parsons M. Imaging of cell adhesion events in 3D matrix environments. Eur J Cell Biol 91: 824–833, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jiang H, Rhee S, Ho CH, Grinnell F. Distinguishing fibroblast promigratory and procontractile growth factor environments in 3-D collagen matrices. FASEB J 22: 2151–2160, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Johnson LA, Rodansky ES, Sauder KL, Horowitz JC, Mih JD, Tschumperlin DJ, Higgins PD. Matrix stiffness corresponding to strictured bowel induces a fibrogenic response in human colonic fibroblasts. Inflamm Bowel Dis 19: 891–903, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Juin A, Billottet C, Moreau V, Destaing O, Albiges-Rizo C, Rosenbaum J, Genot E, Saltel F. Physiological type I collagen organization induces the formation of a novel class of linear invadosomes. Mol Biol Cell 23: 297–309, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kalluri R, Neilson EG. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition and its implications for fibrosis. J Clin Invest 112: 1776–1784, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kessler D, Dethlefsen S, Haase I, Plomann M, Hirche F, Krieg T, Eckes B. Fibroblasts in mechanically stressed collagen lattices assume a “synthetic” phenotype. J Biol Chem 276: 36575–36585, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kim J, Yu W, Kovalski K, Ossowski L. Requirement for specific proteases in cancer cell intravasation as revealed by a novel semiquantitative PCR-based assay. Cell 94: 353–362, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kimura H, Hayashi K, Yamauchi K, Yamamoto N, Tsuchiya H, Tomita K, Kishimoto H, Bouvet M, Hoffman RM. Real-time imaging of single cancer-cell dynamics of lung metastasis. J Cell Biochem 109: 58–64, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kubow KE, Horwitz AR. Reducing background fluorescence reveals adhesions in 3D matrices. Nat Cell Biol 13: 3–5; author reply: 5–7, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ladoux B, Nicolas A. Physically based principles of cell adhesion mechanosensitivity in tissues. Rep Prog Phys 75: 116601, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lauffenburger DA, Horwitz AF. Cell migration: a physically integrated molecular process. Cell 84: 359–369, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Leung LY, Tian D, Brangwynne CP, Weitz DA, Tschumperlin DJ. A new microrheometric approach reveals individual and cooperative roles for TGF-beta1 and IL-1beta in fibroblast-mediated stiffening of collagen gels. FASEB J 21: 2064–2073, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Li Y, Jiang D, Liang J, Meltzer EB, Gray A, Miura R, Wogensen L, Yamaguchi Y, Noble PW. Severe lung fibrosis requires an invasive fibroblast phenotype regulated by hyaluronan and CD44. J Exp Med 208: 1459–1471, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Li Z, Dranoff JA, Chan EP, Uemura M, Sevigny J, Wells RG. Transforming growth factor-beta and substrate stiffness regulate portal fibroblast activation in culture. Hepatology 46: 1246–1256, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Liu F, Mih JD, Shea BS, Kho AT, Sharif AS, Tager AM, Tschumperlin DJ. Feedback amplification of fibrosis through matrix stiffening and COX-2 suppression. J Cell Biol 190: 693–706, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lo CM, Wang HB, Dembo M, Wang YL. Cell movement is guided by the rigidity of the substrate. Biophys J 79: 144–152, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lohela M, Werb Z. Intravital imaging of stromal cell dynamics in tumors. Curr Opin Genet Dev 20: 72–78, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Marinkovic A, Liu F, Tschumperlin DJ. Matrices of physiologic stiffness potently inactivate idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis fibroblasts. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 48: 422–430, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Marinkovic A, Mih JD, Park JA, Liu F, Tschumperlin DJ. Improved throughput traction microscopy reveals pivotal role for matrix stiffness in fibroblast contractility and TGF-beta responsiveness. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 303: L169–L180, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Marquez JP, Genin GM, Pryse KM, Elson EL. Cellular and matrix contributions to tissue construct stiffness increase with cellular concentration. Ann Biomed Eng 34: 1475–1482, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Marquez JP, Legant W, Lam V, Cayemberg A, Elson E, Wakatsuki T. High-throughput measurements of hydrogel tissue construct mechanics. Tissue Eng Part C Methods 15: 181–190, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Meshel AS, Wei Q, Adelstein RS, Sheetz MP. Basic mechanism of three-dimensional collagen fibre transport by fibroblasts. Nat Cell Biol 7: 157–164, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Mierke CT, Kollmannsberger P, Zitterbart DP, Diez G, Koch TM, Marg S, Ziegler WH, Goldmann WH, Fabry B. Vinculin facilitates cell invasion into three-dimensional collagen matrices. J Biol Chem 285: 13121–13130, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Mih JD, Marinkovic A, Liu F, Sharif AS, Tschumperlin DJ. Matrix stiffness reverses the effect of actomyosin tension on cell proliferation. J Cell Sci 125: 5974–5983, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Mih JD, Sharif AS, Liu F, Marinkovic A, Symer MM, Tschumperlin DJ. A multiwell platform for studying stiffness-dependent cell biology. PLos One 6: e19929, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Miron-Mendoza M, Seemann J, Grinnell F. Collagen fibril flow and tissue translocation coupled to fibroblast migration in 3D collagen matrices. Mol Biol Cell 19: 2051–2058, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Miron-Mendoza M, Seemann J, Grinnell F. The differential regulation of cell motile activity through matrix stiffness and porosity in three dimensional collagen matrices. Biomaterials 31: 6425–6435, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Naba A, Clauser KR, Hoersch S, Liu H, Carr SA, Hynes RO. The matrisome: in silico definition and in vivo characterization by proteomics of normal and tumor extracellular matrices. Mol Cell Proteomics 11: M111 014647, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Nakagawa S, Pawelek P, Grinnell F. Extracellular matrix organization modulates fibroblast growth and growth factor responsiveness. Exp Cell Res 182: 572–582, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Nakagawa S, Pawelek P, Grinnell F. Long-term culture of fibroblasts in contracted collagen gels: effects on cell growth and biosynthetic activity. J Invest Dermatol 93: 792–798, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Nho RS, Hergert P, Kahm J, Jessurun J, Henke C. Pathological alteration of FoxO3a activity promotes idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis fibroblast proliferation on type i collagen matrix. Am J Pathol 179: 2420–2430, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Ochsner M, Textor M, Vogel V, Smith ML. Dimensionality controls cytoskeleton assembly and metabolism of fibroblast cells in response to rigidity and shape. PLos One 5: e9445, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Packard BZ, Artym VV, Komoriya A, Yamada KM. Direct visualization of protease activity on cells migrating in three-dimensions. Matrix Biol 28: 3–10, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Palecek SP, Loftus JC, Ginsberg MH, Lauffenburger DA, Horwitz AF. Integrin-ligand binding properties govern cell migration speed through cell-substratum adhesiveness. Nature 385: 537–540, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Paszek MJ, Zahir N, Johnson KR, Lakins JN, Rozenberg GI, Gefen A, Reinhart-King CA, Margulies SS, Dembo M, Boettiger D, Hammer DA, Weaver VM. Tensional homeostasis and the malignant phenotype. Cancer Cell 8: 241–254, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Pedersen JA, Swartz MA. Mechanobiology in the third dimension. Ann Biomed Eng 33: 1469–1490, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Pelham RJ, Jr, Wang Y. Cell locomotion and focal adhesions are regulated by substrate flexibility. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 94: 13661–13665, 1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Pelham RJ, Jr, Wang Y. High resolution detection of mechanical forces exerted by locomoting fibroblasts on the substrate. Mol Biol Cell 10: 935–945, 1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Petrie RJ, Doyle AD, Yamada KM. Random versus directionally persistent cell migration. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 10: 538–549, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Petrie RJ, Gavara N, Chadwick RS, Yamada KM. Nonpolarized signaling reveals two distinct modes of 3D cell migration. J Cell Biol 197: 439–455, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Pinner S, Sahai E. Imaging amoeboid cancer cell motility in vivo. J Microsc 231: 441–445, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Plotnikov SV, Pasapera AM, Sabass B, Waterman CM. Force fluctuations within focal adhesions mediate ECM-rigidity sensing to guide directed cell migration. Cell 151: 1513–1527, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Raab M, Swift J, Dingal PC, Shah P, Shin JW, Discher DE. Crawling from soft to stiff matrix polarizes the cytoskeleton and phosphoregulates myosin-II heavy chain. J Cell Biol 199: 669–683, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Raub CB, Suresh V, Krasieva T, Lyubovitsky J, Mih JD, Putnam AJ, Tromberg BJ, George SC. Noninvasive assessment of collagen gel microstructure and mechanics using multiphoton microscopy. Biophys J 92: 2212–2222, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Raub CB, Unruh J, Suresh V, Krasieva T, Lindmo T, Gratton E, Tromberg BJ, George SC. Image correlation spectroscopy of multiphoton images correlates with collagen mechanical properties. Biophys J 94: 2361–2373, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Ridley AJ, Schwartz MA, Burridge K, Firtel RA, Ginsberg MH, Borisy G, Parsons JT, Horwitz AR. Cell migration: integrating signals from front to back. Science 302: 1704–1709, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Rinkevich Y, Mori T, Sahoo D, Xu PX, Bermingham JR, Jr, Weissman IL. Identification and prospective isolation of a mesothelial precursor lineage giving rise to smooth muscle cells and fibroblasts for mammalian internal organs, and their vasculature. Nature Cell Biol 14: 1251–1260, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Rinn JL, Bondre C, Gladstone HB, Brown PO, Chang HY. Anatomic demarcation by positional variation in fibroblast gene expression programs. PLos Genet 2: e119, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Rinn JL, Wang JK, Allen N, Brugmann SA, Mikels AJ, Liu H, Ridky TW, Stadler HS, Nusse R, Helms JA, Chang HY. A dermal HOX transcriptional program regulates site-specific epidermal fate. Genes Dev 22: 303–307, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Rock JR, Barkauskas CE, Cronce MJ, Xue Y, Harris JR, Liang J, Noble PW, Hogan BL. Multiple stromal populations contribute to pulmonary fibrosis without evidence for epithelial to mesenchymal transition. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108: 1475–1483, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Roeder BA, Kokini K, Sturgis JE, Robinson JP, Voytik-Harbin SL. Tensile mechanical properties of three-dimensional type I collagen extracellular matrices with varied microstructure. J Biomech Eng 124: 214–222, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Rosenfeldt H, Grinnell F. Fibroblast quiescence and the disruption of ERK signaling in mechanically unloaded collagen matrices. J Biol Chem 275: 3088–3092, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Rowe RG, Keena D, Sabeh F, Willis AL, Weiss SJ. Pulmonary fibroblasts mobilize the membrane-tethered matrix metalloprotease, MT1-MMP, to destructively remodel and invade interstitial type I collagen barriers. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 301: L683–L692, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Sabeh F, Li XY, Saunders TL, Rowe RG, Weiss SJ. Secreted versus membrane-anchored collagenases: relative roles in fibroblast-dependent collagenolysis and invasion. J Biol Chem 284: 23001–23011, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Sabeh F, Ota I, Holmbeck K, Birkedal-Hansen H, Soloway P, Balbin M, Lopez-Otin C, Shapiro S, Inada M, Krane S, Allen E, Chung D, Weiss SJ. Tumor cell traffic through the extracellular matrix is controlled by the membrane-anchored collagenase MT1-MMP. J Cell Biol 167: 769–781, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Sabeh F, Shimizu-Hirota R, Weiss SJ. Protease-dependent versus -independent cancer cell invasion programs: three-dimensional amoeboid movement revisited. J Cell Biol 185: 11–19, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Salmon H, Franciszkiewicz K, Damotte D, Dieu-Nosjean MC, Validire P, Trautmann A, Mami-Chouaib F, Donnadieu E. Matrix architecture defines the preferential localization and migration of T cells into the stroma of human lung tumors. J Clin Invest 122: 899–910, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Sarber R, Hull B, Merrill C, Soranno T, Bell E. Regulation of proliferation of fibroblasts of low and high population doubling levels grown in collagen lattices. Mech Ageing Dev 17: 107–117, 1981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Sato K, Ebihara T, Adachi E, Kawashima S, Hattori S, Irie S. Possible involvement of aminotelopeptide in self-assembly and thermal stability of collagen I as revealed by its removal with proteases. J Biol Chem 275: 25870–25875, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Sawhney RK, Howard J. Slow local movements of collagen fibers by fibroblasts drive the rapid global self-organization of collagen gels. J Cell Biol 157: 1083–1091, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Sorrell JM, Caplan AI. Fibroblasts-a diverse population at the center of it all. Int Rev Cell Mol Biol 276: 161–214, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Soucy PA, Werbin J, Heinz W, Hoh JH, Romer LH. Microelastic properties of lung cell-derived extracellular matrix. Acta Biomater 7: 96–105, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Souders CA, Bowers SL, Baudino TA. Cardiac fibroblast: the renaissance cell. Circ Res 105: 1164–1176, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Storm C, Pastore JJ, MacKintosh FC, Lubensky TC, Janmey PA. Nonlinear elasticity in biological gels. Nature 435: 191–194, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Tager AM, LaCamera P, Shea BS, Campanella GS, Selman M, Zhao Z, Polosukhin V, Wain J, Karimi-Shah BA, Kim ND, Hart WK, Pardo A, Blackwell TS, Xu Y, Chun J, Luster AD. The lysophosphatidic acid receptor LPA1 links pulmonary fibrosis to lung injury by mediating fibroblast recruitment and vascular leak. Nat Med 14: 45–54, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Tamariz E, Grinnell F. Modulation of fibroblast morphology and adhesion during collagen matrix remodeling. Mol Biol Cell 13: 3915–3929, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Tanjore H, Xu XC, Polosukhin VV, Degryse AL, Li B, Han W, Sherrill TP, Plieth D, Neilson EG, Blackwell TS, Lawson WE. Contribution of epithelial-derived fibroblasts to bleomycin-induced lung fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 180: 657–665, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Theriot JA, Mitchison TJ. Comparison of actin and cell surface dynamics in motile fibroblasts. J Cell Biol 119: 367–377, 1992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Todaro GJ, Green H. Quantitative studies of the growth of mouse embryo cells in culture and their development into established lines. J Cell Biol 17: 299–313, 1963 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Tomasek JJ, Gabbiani G, Hinz B, Chaponnier C, Brown RA. Myofibroblasts and mechano-regulation of connective tissue remodelling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 3: 349–363, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Tschumperlin DJ, Jones JC, Senior RM. The fibrotic matrix in control: does the extracellular matrix drive progression of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis? Am J Respir Crit Care Med 186: 814–816, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Vasiliev JM, Gelfand IM, Domnina LV, Ivanova OY, Komm SG, Olshevskaja LV. Effect of colcemid on the locomotory behaviour of fibroblasts. J Embryol Exp Morphol 24: 625–640, 1970 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Wang YL. Exchange of actin subunits at the leading edge of living fibroblasts: possible role of treadmilling. J Cell Biol 101: 597–602, 1985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.White ES, Thannickal VJ, Carskadon SL, Dickie EG, Livant DL, Markwart S, Toews GB, Arenberg DA. Integrin alpha4beta1 regulates migration across basement membranes by lung fibroblasts: a role for phosphatase and tensin homologue deleted on chromosome 10. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 168: 436–442, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Wipff PJ, Rifkin DB, Meister JJ, Hinz B. Myofibroblast contraction activates latent TGF-beta1 from the extracellular matrix. J Cell Biol 179: 1311–1323, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Wolf K, Mazo I, Leung H, Engelke K, von Andrian UH, Deryugina EI, Strongin AY, Brocker EB, Friedl P. Compensation mechanism in tumor cell migration: mesenchymal-amoeboid transition after blocking of pericellular proteolysis. J Cell Biol 160: 267–277, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Woodley DT, Yamauchi M, Wynn KC, Mechanic G, Briggaman RA. Collagen telopeptides (cross-linking sites) play a role in collagen gel lattice contraction. J Invest Dermatol 97: 580–585, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Xia H, Diebold D, Nho R, Perlman D, Kleidon J, Kahm J, Avdulov S, Peterson M, Nerva J, Bitterman P, Henke C. Pathological integrin signaling enhances proliferation of primary lung fibroblasts from patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. J Exp Med 205: 1659–1672, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Xia H, Nho R, Kleidon J, Kahm J, Henke CA. Polymerized collagen inhibits fibroblast proliferation via a mechanism involving the formation of a beta1 integrin-protein phosphatase 2A-tuberous sclerosis complex 2 complex that suppresses S6K1 activity. J Biol Chem 283: 20350–20360, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Yamaguchi Y, Takihara T, Chambers RA, Veraldi KL, Larregina AT, Feghali-Bostwick CA. A peptide derived from endostatin ameliorates organ fibrosis. Sci Transl Med 4: 136–171, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Zaidel-Bar R, Itzkovitz S, Ma'ayan A, Iyengar R, Geiger B. Functional atlas of the integrin adhesome. Nat Cell Biol 9: 858–867, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Zhou Y, Huang X, Hecker L, Kurundkar D, Kurundkar A, Liu H, Jin TH, Desai L, Bernard K, Thannickal VJ. Inhibition of mechanosensitive signaling in myofibroblasts ameliorates experimental pulmonary fibrosis. J Clin Invest 123: 1096–1108, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Zhu S, Gladson CL, White KE, Ding Q, Stewart J, Jr, Jin TH, Chapman HA, Jr, Olman MA. Urokinase receptor mediates lung fibroblast attachment and migration toward provisional matrix proteins through interaction with multiple integrins. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 297: L97–L108, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]