Abstract

Small RNAs (sRNAs), as a key component of molecular biology, play essential roles in plant development, hormone signaling, and stress response. However, little is known about the relationships among sRNAs, hormone signaling, and dormancy regulation in gymnosperm embryos. To investigate the roles of sRNAs in embryo dormancy maintenance and release in Larix leptolepis, we deciphered the endogenous “sRNAome” in dormant and germinated embryos. High-throughput sequencing of sRNA libraries showed that dormant embryos exhibited a length bias toward 24-nt while germinated embryos showed a bias toward 21-nt lengths. This might be associated with distinct levels of RNA-dependent RNA polymerase2 (RDR2) and/or RDR6, which is regulated by hormones. Proportions of miRNAs to nonredundant and redundant sRNAs were higher in germinated embryos than in dormant embryos, while the ratio of unknown sRNAs was higher in dormant embryos than in germinated embryos. We identified a total of 160 conserved miRNAs from 38 families, 3 novel miRNAs, and 16 plausible miRNA candidates, of which many were upregulated in germinated embryos relative to dormant embryos. These findings indicate that larches and possibly other gymnosperms have complex mechanisms of gene regulation involving miRNAs and other sRNAs operating transcriptionally and posttranscriptionally during embryo dormancy and germination. We propose that abscisic acid modulates embryo dormancy and germination at least in part through regulation of the expression level of sRNA-biogenesis genes, thus changing the sRNA components.

Introduction

Japanese larch (Larix leptolepis), a uniquely suitable Pinaceae for the experimental study of gymnosperms, is one of the most important forestry trees in northern China, Russia, Europe, and Japan [1], [2]. The germination of the seed embryo is a critical step in the production of larches. Due to their inaccessibility along with difficulties associated with gymnosperm seed embryos, we used somatic embryogenesis as an experimental system to gain information about morphological and molecular changes that take place during embryo dormancy and germination. Somatic embryogenesis is defined as a process in which a bipolar structure resembling a zygotic embryo is used as a model for studying the regulation of embryo development [3].

Seed dormancy and germination are regulated by developmental and environmental cues [4], [5]. Maturation of seed embryos leads to a concomitant gradual decrease of metabolism as water is lost from the seed tissue and the embryo passes into a metabolically inactive, or quiescent, state [6]. Previous studies showed that the balance between abscisic acid (ABA) and gibberellin (GA) is important for determining the dormancy status of seed embryos [7]. ABA is abundant in dormant seeds and generally decreases when dormancy is released [8], whereas some GAs increase during the process of germination [9]. ABA metabolism and signaling potentially act as the node for hormone cross talk [10]. Recent progress in basic research has advanced our understanding of the mechanisms of seed dormancy and germination in model plant species, but little is known regarding the mechanisms underlying the complex regulation of seed dormancy and germination by transcriptional and posttranscriptional controls, especially for gymnosperms.

Mounting evidence has revealed that small RNAs (sRNAs), exemplified by microRNAs (miRNAs), play pivotal roles in each major stage of plant development, mediating the transition from one developmental stage to the next [11], [12]. RNA silencing directed by sRNAs is a highly conserved regulatory mechanism known to be involved in diverse processes, such as development, hormone signaling, antiviral defense, genome maintenance, and stress response [13], [14]. Ever since the ground-breaking discovery of sRNAs [15], [16], the goal of many laboratories has been to decipher the endogenous “sRNAome” of living organisms with the aim to understand its biogenesis and function. sRNAs mainly include miRNAs and several forms of small interfering RNAs (siRNAs), including trans-acting siRNAs (ta-siRNAs), natural antisense siRNAs (nat-siRNAs), and repeat-associated siRNAs (ra-siRNAs). These sRNAs are usually 20- to 24-nucleotides (nt) in length and are found in nearly all eukaryotes [11], [17]. In plants, the pool of sRNAs is complex and dynamic, consisting primarily of many low-abundant siRNAs and a small number of highly expressed miRNAs [13], [14].

Arabidopsis has four Dicer-like (DCL) proteins with distinct, hierarchical, and overlapping functions in sRNA biogenesis. Most miRNAs are processed by DCL1 enzymes [18], although a few evolutionarily young miRNAs are generated by DCL4 [19]. DCL3 produces 24-nt ra-siRNAs at heterochromatic loci [20] and is conserved in both angiosperms and mosses [21], [22]. Several previous studies have indicated the absence of DCL3 in conifers by expressed sequence tag (EST) searching; thus, conifers fail to show appreciable amounts of 24-nt sRNAs [23], [24], [25]. Unexpectedly, two recent reports have documented homologs of DCL3 in two gymnosperm species, Cunninghamia lanceolata and Larix principis-rupprechtii [26], [27]. RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RDR) is known to be responsible for the synthesis of double-stranded RNA on single-stranded RNA substrates. Arabidopsis has six RDR genes, of which RDR2 is a crucial factor in the biogenesis of ra-siRNAs, representing over 90% of these siRNAs [28], [29]. RDR6 has been implicated in the biogenesis of siRNAs from plant viruses and transgenes and also acts in the biogenesis of ta-siRNAs [30].

Recent evidence has implicated hormone signaling in the regulation of sRNAs by affecting the abundance of sRNA pathway genes. OsRDR6-dependent siRNA generation is significantly upregulated by ABA, while four other RDRs, including RDR2, are not regulated by ABA in Oryza sativa [31]. miR168 controls AGO1 homeostasis during ABA treatment and abiotic stress responses in Arabidopsis thaliana [32]. GA has been shown to regulate miR159 levels during anther development [33]. Several sRNA target genes have roles in auxin signaling, such as miR160, miR393, miR167, and tasiR-ARFs [34]. Furthermore, miRNAs regulated by hormones are associated with seed germination. ABA induction of miR159 controls MYB33 and MYB101, and overexpression of miR159 or mutations in MYB33 and MYB101 lead to ABA hyposensitivity [35]. ARF10, ARF16, and ARF17 targeted by miR160 have roles in auxin signaling, which is critical for seed germination and post-germination stages [36], [37]. Auxin-ABA cross talk is present in imbibed seeds and the downregulation of ARF10 by miR160 is essential for the auxin–ABA cross talk during germination [38]. Compared to the information available for the roles of miRNA in embryo dormancy and germination in angiosperms, little is known in gymnosperms, in which the anatomy and biology of the cell and the molecular mechanisms used during embryogenesis differ significantly from those in angiosperms [39], [40].

In this study, somatic embryos were used to decipher the dynamic sRNAome during the transition from dormant embryos into germinated embryos in L. leptolepis. Our results showed that the length distribution and components of sRNAs change dramatically between these two classes of embryos, which may be attributable to distinct RDR2 and RDR6 expression regulated by hormone content. In total, 160 conserved miRNAs from 38 families, 3 novel miRNAs, and 16 plausible miRNA candidates were identified. Most miRNAs were upregulated in germinated embryos relative to dormant embryos and their targets showed the opposite expression pattern.

Results

The Morphology of the Dormant and Germinated Larch Embryos

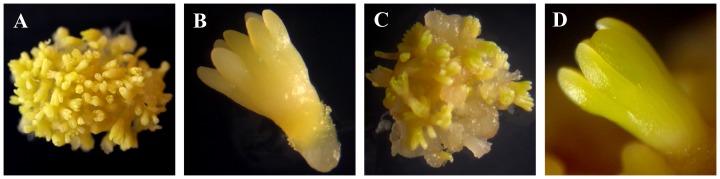

After mature somatic embryos were grown for 12 days on ABA-containing medium, the embryos entered into a dormant or quiescent phase and became faint yellow. However, the germinated embryos turned yellow–green, especially the cotyledons, after culture for 12 days on non-ABA medium (Figure 1). In addition, the germinated embryos were larger than these of dormant embryos, which might have been due to increased cell elongation and cell division in dormancy released embryos. Considerable elongation of the embryos, exemplified by the cotyledons, was due mainly to cell division in the cotyledons.

Figure 1. The morphology of dormant and germinated embryos in larch.

(A and B) The embryos entered into dormant or quiescent status when the embryos were faint yellow. (C and D) The embryo with larger size turned yellow–green, especially the cotyledons, after culture for 12 days on non-ABA medium.

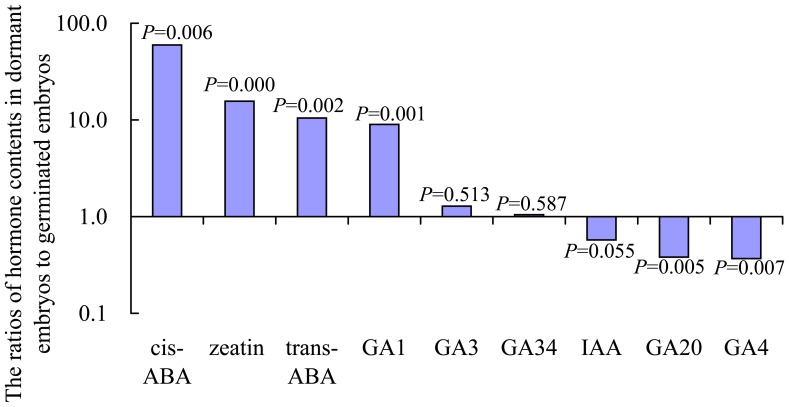

Hormone Content of the Dormant and Germinated Embryos

The hormone content differed significantly between dormant embryos and germinated embryos (Figure 2). The level of cis/trans-ABA was significantly higher in dormant embryos than in germinated embryos. Thus, the content of three hormones, IAA, GA4, and GA20, was higher in germinated embryos than in dormant embryos. Unexpectedly, GA1, GA3, GA34, and zeatin were more abundant in dormant embryos than in germinated embryos. However, the ratio of ABA to GAs was much lower in germinated embryos than in dormant embryos.

Figure 2. The hormone contents were compared between dormant embryos treated with ABA and germinated embryos with no ABA after embryo maturation.

Presented values are the mean (±SE) content of hormones of three independent samples per treatment.

High-throughput Sequencing Reveals a Dynamic Change in sRNAs from Dormant Embryo to Germination

In total, 16,514,593 and 16,415,719 raw reads were obtained from the dormant and germinated embryo sRNA libraries, and the accession number was GSM1214805 and GSM1193109, respectively. After removal of nonsense reads, we obtained clean reads with lengths of 18–30 nt, representing 16,342,531 (98.96%) and 16,123,435 (98.22%) sequences and 5,644,091 and 2,880,823 nonredundant sequences, respectively. These high-quality sRNAs were used for further analysis.

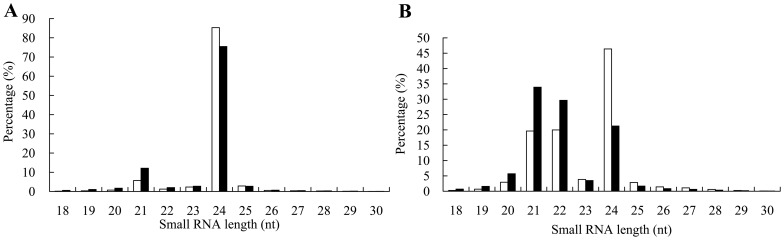

Both batches contained a similar size distribution of nonredundant sRNAs, with 24-nt representing the largest class in batch 1 (85%, white bars) and batch 2 (75%, black bars in Figure 3A). Another minor peak was at 21-nt, accounting for 5.7% in batch 1 and 12.1% in batch 2. However, the overall distribution of the redundant sRNAs was strikingly different in the two libraries (Figure 3B), with one major peak at 24-nt and another minor peak at 21-nt or 22-nt in dormant embryos (white bars). Once the embryo germinated, the proportion of 24-nt sRNAs decreased and the 21-nt population increased to a major peak (black bars). Furthermore, the 24-nt class of sRNAs exhibited the lowest redundancy in both libraries, with an average frequency of 1.57 and 1.58 per nonredundant sequence, while the 22-nt length showed the highest redundancy, with an average frequency of 46.36 and 82.15 per nonredundant sequence in dormant embryos and germinated embryos, respectively.

Figure 3. Length distribution of sRNA sequences in larch embryos.

(A) Frequencies are expressed as the percentage of the total nonredundant sequences for dormant embryos (white bars) and germinated embryos (black bars). (B) Frequencies are expressed as the percentage of the total redundant sequences for dormant embryos (white bars) and germinated embryos (black bars).

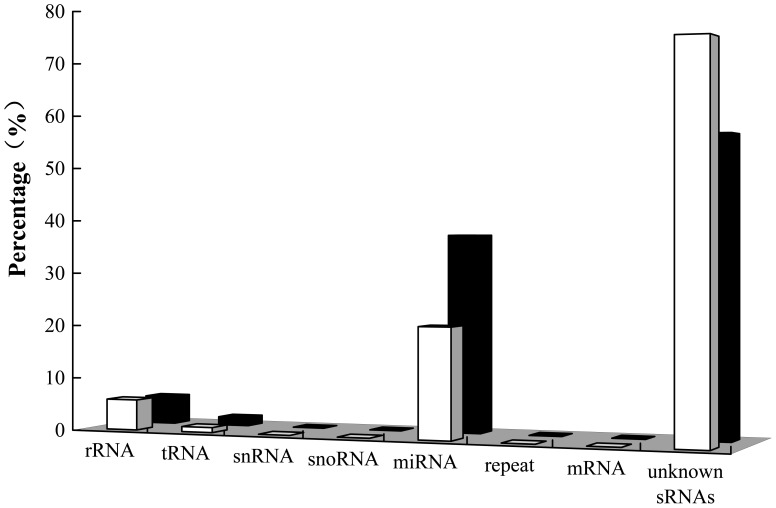

Deciphering the Components of sRNAs in Dormant and Germinated Embryos

Sequences were aligned to known RNAs in Rfam 11.0 [41], GenBank, Repeat–repbase [42], miRBase 19.0 (http://www.mirbase.org) [43], and larch miRNAs [44], including rRNAs, tRNAs, snRNAs, snoRNAs, miRNAs, ra-siRNAs, and mRNA fragments. Sequences that matched to known RNAs accounted for small fractions, 1.10% and 2.29%, respectively, of the nonredundant sequences and 27.40% and 44.05% of the redundant sequences in the dormant and germinated libraries, respectively. Thus, an overrepresented part of the nonredundant sRNAs was composed of unknown sRNAs (Figure 4). Note that the proportion of miRNAs in germinated embryos (37.25%) was higher than in dormant embryos (20.70%); nonredundant miRNAs accounted for 0.42% in germinated embryos and 0.20% in dormant embryos. Unexpectedly, a relatively small amount of raw reads, 5.72% in dormant embryos and 5.23% in germinated embryos, matched rRNAs.

Figure 4. Distribution of sRNA annotation categories in dormant embryos (white bars) and germinated embryos (black bars).

Sequences that matched to known RNAs accounted for small fractions, 27.40% and 44.05% of the redundant sequences in the dormant and germinated libraries, respectively. Thus, an overrepresented part of the nonredundant sRNAs was composed of unknown sRNAs.

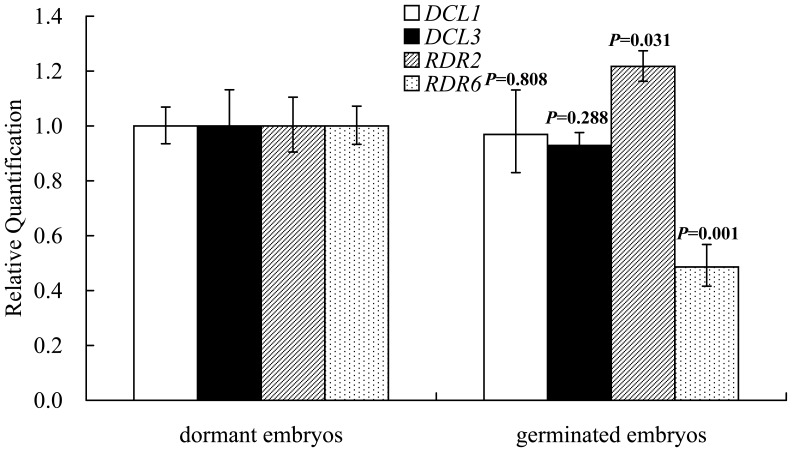

Expression Patterns of DCL1, DCL3, RDR2, and RDR6 in Dormant Embryos and Germinated Embryos

To determine the expression changes of DCL1, DCL3, RDR2, and RDR6 between dormant embryos and germinated embryos, we assayed the gene expression levels of embryos when cultured in ABA or non-ABA medium using qRT-PCR (Figure 5). Unexpectedly, DCL1 and DCL3 were not differentially expressed between dormant and germinated embryos. However, the expression level of RDR2 was significantly higher in germinated embryos relative to dormant embryos, while RDR6 showed the opposite expression pattern between these two embryo classes, which was consistent with the low level of ABA.

Figure 5. qRT-PCR analysis of the relative expression of DCL1 (white bars), DCL3 (black bars), RDR2 (striped bars), and RDR6 (dotted bars) in dormant embryos and germinated embryos.

All expression levels were normalized to that of EF-1α and then normalized by comparison to the level of dormant embryos, which was set at 1.0. The experiments were repeated three times and error bars represent the SD. The abundance difference of genes between two classes of embryos was evaluated by a t-test using SPSS software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

miRNA Identification and Profiling: Dormant Embryos and Germinated Embryos

Currently, miRNAs from 18 broadly conserved families, including 81 members, have been identified, as well as 20 families that were species-specific or restricted to certain plant families, exemplified by 37 miRNAs from 9 families that appear to be specific to gymnosperms or conifers (Table 1). We followed a homolog-based approach to search for already known miRNAs in our two sRNA libraries using miRBase (release 19.0) as a reference set. The miRNA abundance among the families was notably variable in dormant embryos and germinated embryos. For example, miR950, miR165/166, and miR156/157 were most highly expressed and were detected 2,232,537, 481,738, and 217,941 times in dormant embryos and 3,538,778, 1,064,904, and 522,272 times in germinated embryos, respectively. However, miR160, miR393, and miR827 were detected two, three, and three times in dormant embryos and six, nine, and seven times in germinated embryos, respectively.

Table 1. Identification of known miRNAs in larch.

| 18 highly conserved miRNA families | ||||

| Family Name (number of members) | Conserved species (number of members) | |||

| Number | ath | osa | others | |

| miR156/157 (8) | 41 | 11 | 12 | pta (2) |

| miR159/319/4414 (16) | 32 | 6 | 8 | pta (4) |

| miR160 (1) | 33 | 3 | 6 | pab (2) |

| miR162 (2) | 25 | 2 | 2 | ptc (3) |

| miR164 (5) | 26 | 3 | 6 | ptc (6) |

| miR165/166 (16) | 35 | 9 | 14 | pab (2) |

| miR167 (7) | 32 | 4 | 10 | ptc (8) |

| miR168 (3) | 26 | 2 | 2 | ptc (2) |

| miR169 (3) | 27 | 14 | 17 | ptc (32) |

| miR171 (2) | 36 | 3 | 9 | pta (1) |

| miR172 (4) | 30 | 5 | 4 | ptc (9) |

| miR390 (2) | 23 | 2 | 1 | pta (1) |

| miR393 (1) | 22 | 2 | 2 | ptc (4) |

| miR396 (3) | 35 | 2 | 9 | pab (3) |

| miR397 (2) | 21 | 2 | 2 | pab (1) |

| miR398 (2) | 25 | 3 | 2 | pta (1) |

| miR399 (2) | 29 | 6 | 11 | ptc (12) |

| miR408 (2) | 28 | 1 | 1 | pta (1) |

| 20 known families showed partial conservation with other plants | ||||

| Family Name (number of members) | Conserved species (number of members) | |||

| Number | pta | pab | others | |

| miR894 (8) | 1 | / | / | ppt (1) |

| miR1083 (1) | 1 | / | / | smo (1) |

| miR5059 (5) | 1 | / | / | bdi (1) |

| miR5139 (4) | 1 | / | / | rgi (1) |

| miR482 (4) | 22 | 4 | 4 | ptc (3) |

| miR528 (2) | 5 | / | / | osa (1) |

| miR529 (3) | 9 | / | / | ppt (7) |

| miR535 (5) | 9 | / | 1 | ppt (4) |

| miR536 (1) | 2 | / | / | ppt (5) |

| miR827 (1) | 12 | / | / | ath (1) |

| miR2118 (2) | 9 | / | / | osa (18) |

| miR947 (1), miR950 (12), miR951 (4), miR1311 (5) | 3 | 1 | 1 | pde (1) |

| miR946 (6), miR1312 (2), miR1313 (2),miR1314 (2), miR3701 (3) | 2 | 1 | / | pde (1) |

ath: Arabidopsis thaliana; osa: Oryza sativa; ptc: Populus trichocarpa; pta: Pinus taeda; pab: Picea abies; ppt: Physcomitrella patens; smo: Selaginella moellendorffii; rgi: Rehmannia glutinosa; bdi: Brachypodium distachyon; pde: Pinus densata.

To uncover additional larch-specific miRNA candidates within our sequence data set, sequences were aligned against the L. leptolepis ESTs. Nineteen ESTs containing 19 potential miRNA precursors were selected for further analysis. Of these, three mature miRNA sequences with their corresponding miRNA* sequences were identified as novel miRNAs, together with 16 candidate miRNAs (Table 2).

Table 2. Isolation and identification of novel miRNAs in larch embryo.

| Name | Sequence(5′-3′) | Nucleotide(length) | Read(Dormant embryo) | Read(Germinated embryo) | Containing EST |

| llemiR-1 | UGCCGUGGUUCGGAGCGAUCGA | 22 | 11005 | 15905 | JR179967 |

| llemiR-1* | AUCCUCCCAACCAAGGCAACC | 21 | 2 | 7 | JR179967 |

| llemiR-2 | UGACCAGUCCUUCUGCGAUCCA | 22 | 148 | 162 | JR164575 |

| llemiR-2* | AAUUGCAGAAGGGCUGGUUAGC | 22 | 789 | 1007 | JR164575 |

| llemiR-3 | UCAAGUGUUUCUGGACUCACC | 21 | 5 | 0 | JR164003 |

| llemiR-3* | UGAGUCCAGACACACUUCGGC | 21 | 1 | 1 | JR164003 |

| llemiR-4 | UUUGAUAGAUCCGAGGUUAAG | 21 | 70 | 64 | PEMSG842Xa |

| llemiR-5 | UGCAAAUGGUGUUUGCGUCGU | 21 | 16 | 26 | JR170741 |

| llemiR-6 | UCCAUGACUUUCCAGAGGGGU | 21 | 336 | 298 | JR184550 |

| llemiR-7 | UCAUUCCAGUUAUCGUUCUCC | 22 | 50 | 74 | JR185282 |

| llemiR-8 | UCUGCCUGGUACCUUGACGUA | 21 | 98 | 124 | JR174289 |

| llemiR-9 | UCGCAGGUGAGAUGACGCCGGC | 22 | 52 | 88 | JR160786 |

| llemiR-10 | UGAGCUCUUGGAAGUGUUGGA | 21 | 205 | 290 | PEMSJJR7Ea |

| llemiR-11 | GCCGUGACCGUGGCGAUCGUGG | 22 | 9 | 7 | JR167874 |

| llemiR-12 | UACACCUCAAGAAAUUGGAUCCCU | 24 | 4 | 1 | JR176014 |

| llemiR-13 | UGAUUCAGGCAUGGAGGAGGACUA | 24 | 10 | 1 | JR179449 |

| llemiR-14 | UCUUUCUGAGGCAUGUAUGGGCAU | 24 | 6 | 1 | JR181565 |

| llemiR-15 | UCAGUGAGCUUAGGGUACGUUGG | 23 | 0 | 4 | JR184842 |

| llemiR-16 | UCGGAAUGCUGGAGGAGGCAA | 21 | 1 | 6 | JR190670 |

| llemiR-17 | UGAGUCCAGACACACUUCGGCU | 22 | 4 | 3 | JR164003 |

| llemiR-18 | CAACGAUCAACAGGACCACUG | 21 | 24 | 16 | JR195099 |

| llemiR-19 | UGUGACGGGGAUGGGAUGCU | 20 | 0 | 11 | JR155419 |

The sequences of PEMSG842X and PEMSJJR7E containing the mature sequence of llemiR-4 and llemiR-10 were not submitted to the TSA database because their length were less than 200 nt.

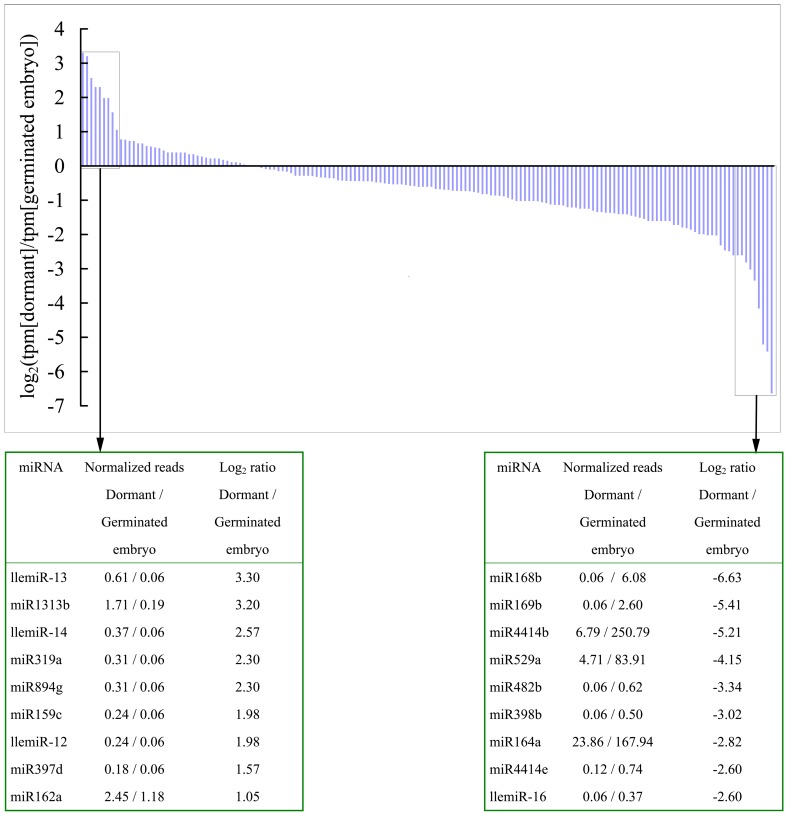

The normalized abundance of individual miRNAs and calculation of log2(tpm[dormant embryos]/tpm[germinated embryos]) can be used to compare the relative abundance of miRNAs between the two stages of larch embryos, as reported previously for Populus [45]. The miRNAs for which log2(tpm[dormant embryos]/tpm[germinated embryos]) were greater than 1 or less than –1 were considered to be up- or downregulated, respectively. In total, 163 miRNAs or miRNA candidates were included in the comparison. The results showed that llemiR-13, miR1313b, llemiR-14, miR319a, miR894g, miR159c, llemiR-12, miR397d, and miR162a were upregulated in dormant embryos, whereas 61 miRNAs, including miR168b, miR169b, miR4414b, and miR529a, were upregulated in germinated embryos (Figure 6 and Table S1). In addition, some miRNAs were expressed in a single library because no corresponding reads were found in the other library; therefore, these could not be assigned a fold-overexpression value. Four miRNAs were represented only in dormant embryos by three or more reads, while 11 miRNAs were detected only in germinated embryos (Table S1). The results of qRT-PCR validated the sequencing data, albeit with smaller fold-changes between dormant embryos and germinated embryos (Figure S1).

Figure 6. Differential expression of miRNAs in dormant and germinated larch embryos.

Expression ratios (the percentages of normalized reads in dormant embryos divided by the percentages of normalized reads in germinated embryos) are shown for all miRNAs that were detected in both the dormant embryo and germinated embryo data sets. Specific data pertaining to the nine most differentially expressed miRNAs at both ends of the spectrum are displayed in the inset, and reads were normalized to tags per million as described in the Methods.

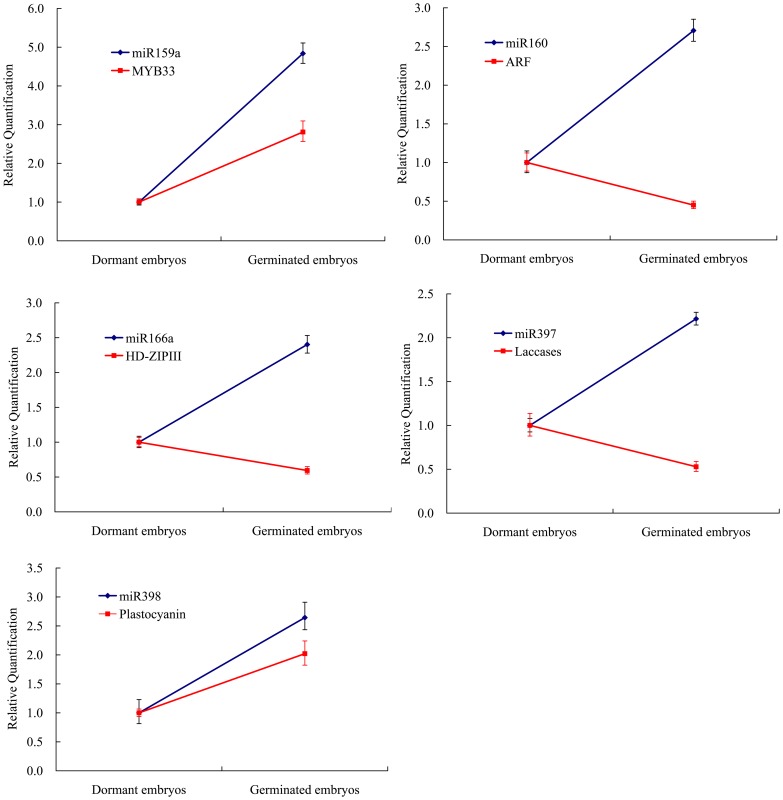

Differential Expression Patterns of miRNAs and Their Target Genes between Dormant Embryos and Germinated Embryos

Referring to the known function of conserved miRNAs, five miRNAs and their target genes were selected as candidate miRNAs related to embryo dormancy and germination. The expression levels of all detected miRNAs were higher in germinated embryos than in dormant embryos, but with distinct fold changes (Figure 7), which was consistent with the results from the high-throughput sequencing of sRNA libraries, except for miR397. Accordingly, the abundance for three target genes was lower in germinated embryos than in dormant embryos, except for MYB33 and plastocyanin, targeted by miR159 and miR398, respectively. The abundance of MYB33 and plastocyanin was higher in germinated embryos than in dormant embryos by 2.81- and 2.02-fold, respectively.

Figure 7. qRT-PCR-derived expression analysis of five miRNAs and their target genes in dormant embryos and germinated embryos.

All expression levels were normalized to that of EF-1α and then normalized by comparison to the level of dormant embryos, which was set at 1.0. The experiments were repeated three times and error bars represent the SD.

Discussion

Differential Hormone Content between Dormant Embryos and Germinated Embryos

Many reasons exist as to why viable embryos and/or seeds do not germinate, and a block in the completion of germination is usually a consequence of multiple events. We have seen a tremendous advance in understanding of hormonal regulation in embryo germination, exemplified by ABA promotion of somatic embryo maturation and entry into dormancy [46], with ABA metabolism and signaling potentially acting as the node for hormone cross talk [10]. Previous studies showed that the balance between ABA and GA is important for determining the dormancy status of seed embryos [7]. Because the actions of hormones are mutually interactive, the consequences of a change in content of a single hormone may be quite different from one state to another in the target tissue [47]. Therefore, simultaneous quantification of multiple hormones from the same plant material is a useful methodology to examine the overall picture of hormone balance [48].

In our study, the content of IAA was not significantly lower in dormant embryos than in germinated embryos, which is consistent with a previous study reporting that IAA content is relatively low in mature embryos [49]. The abundance of cis/trans-ABA was significantly higher in dormant embryos than in germinated embryos, which is consistent with ABA abundance in dormant seeds that generally decreases when seed dormancy is released [8]. Unexpectedly, all detected GAs, except for GA4, were abundant in dormant embryos and at lower levels in germinated embryos. This is opposite to the result that some GAs increase during the transition to germination [9]. However, the ratio of ABA to GAs was much lower in germinated embryos than in dormant embryos, which is consistent with the result that the balance between ABA and GA is important for determining the dormancy status of embryos [7]. Zeatin was more abundant in dormant embryos than in germinated embryos in larches. A similar observation was previously made in a study by Brzobohaty et al. (1993), who observed a high content of ribosylzeatin and low level of active zeatin in dormant seeds, while active zeatin increased rapidly via decreasing zeatin conjugates. In conclusion, a decrease in the ABA content of embryos via the withdrawal of exogenous ABA in the medium alters the content of other hormones, which was supported in a study by Nambara et al. [10], who suggested that ABA metabolism and signaling act as the node for hormone cross talk.

Diverse sRNAs Participate in Embryo Dormancy and Germination

Previous studies indicate that conifers fail to express appreciable amounts of 24-nt sRNAs [23], [24], [25]. However, two recent reports have identified DCL3 homologs and have observed diverse 24-nt sRNAs in two gymnosperm species [26], [27]. In this study, the 24-nt sRNAs were the most diverse, exemplified by more than three-quarters of nonredundant sequences being 24-nt in size and accounting for 85% of the nonredundant sRNAs in dormant embryos. A similar phenomenon is observed in the olive (Olea europaea) in which unique 24-nt sequences account for 80% of the “sRNAome” [50]. However, 60% of the nonredundant sRNAs are 24-nt long in Arabidopsis [51] with 22% in O. sativa [23]. This implies that woody perennials, including gymnosperms and angiosperms, contain a more abundant diversity of 24-nt sRNA than annual herbaceous plants, although the latter may contain a higher proportion of 24-nt redundant sRNAs. Thus, annual herbaceous plants show significantly higher DNA methylation levels than woody perennials [52].

The overall distribution of the redundant sRNAs differed strikingly in the two libraries, with one major peak at 24-nt and another minor peak at 21-nt or 22-nt in dormant embryos, while in germinating embryos, the proportion of 24-nt sRNAs decreased and the 21-nt population increased to a major peak. This was consistent with our previous study reporting that 24-nt sRNAs predominate during embryogenesis, while the distribution patterns change upon embryo germination [27]. Several studies showed that the 24-nt fraction is dominated by sRNA derived from genomic repeats, transposons, and intergenic regions. Thus, most of these sRNAs mainly act as heterochromatin siRNAs in O. sativa [23], A. thaliana [53], and Gossypium hirsutum [54]. Therefore, we speculate that tremendous alteration of epigenetic regulation exists between dormant embryos and germinated embryos.

Unexpectedly, a relatively small amount of raw reads, 5.72% in dormant embryos and 5.23% in germinated embryos, matched rRNAs, which suggested that a large proportion of rRNAs are “dormant” in embryos. A similar phenomenon is observed in cotton (G. hirsutum) ovules, in which the ratio of rRNA fragments to total reads in ovules with fiber cell initials and young fiber-bearing ovules is only 6.37% and 7.03%, respectively. However, the corresponding ratios are much higher in leaves and immature ovules, accounting for 53.83% and 29.56%, respectively [54]. This implies that rRNA degradation is highly regulated, representing a high proportion of rRNAs that are degraded in leaves and immature ovules. Alternatively, the rRNA genes in leaves and immature ovules may be subjected to silencing or nucleolar dominance via RNA-mediated pathways [55]. Moreover, the proportion of miRNAs in germinated embryos (37.25%) was higher than in dormant embryos (20.70%), which implies that miRNAs participate in embryo germination. However, nonredundant miRNA sequences accounted for 0.20% in dormant embryos and 0.42% in germinated embryos. This was consistent with the results that plant sRNAs consist primarily of many low-abundant siRNAs with a small number of highly expressed 21-nt sequences and most of the latter are miRNAs [13], [14].

The Response of sRNA Pathway Genes to Hormones

In this study, the expression level of RDR2 was significantly higher in germinated embryos relative to dormant embryos, while RDR6 had the opposite expression pattern. Furthermore, we observed that a decreasing level of ABA led to a concomitant decrease in RDR6. This was similar to OsRDR6, which is positively regulated by ABA, while OsRDR2 is not regulated by ABA [31]. Our previous study showed that RDR2 accumulated at the lowest level in mature embryos, while it increased in seedlings that originated from somatic embryos [27]. The abundance of RDR6 in germinated embryos was lower than that of dormant embryos, which seems to contradict sRNA composition. The possibility exists that the content of RDR6 was sufficient to the production of siRNAs, or that those siRNAs dependent on RDR6 may not have been the main component affecting sRNA composition, while miRNAs were the main contributor. However, the transcript abundance of DCL1 was not significantly different between dormant embryos and germinated embryos, suggesting that DCL1 was not affected by hormones, especially by ABA. Previous studies showed that other miRNA processing genes may be regulated by hormones, thus affecting the accumulation of miRNAs. This is exemplified by the HYL1 gene, whose expression responds to ABA, auxin, and cytokinin [56]. In our study, this correlation of ABA content and RDR6 accumulation was consistent with the hypothesis that RDR6 was regulated, at least in part, by ABA, thus the expression level of 21-nt ta-siRNA was altered [31].

Potential Roles of miRNAs in Maintaining and Releasing Embryo Dormancy

Early studies on miRNA biogenesis-related mutants implied that miRNAs are essential for seed germination [56], [57], [58]. A previous study showed that miR159 induced by ABA controls transcript levels of MYB33 and MYB101 during Arabidopsis seed germination [35]. In our study, the expression level of miR159a was higher in germinated embryos than in dormant embryos by 4.8-fold (Figure 7). Moreover, the abundance of MYB33 was also higher in germinated embryos relative to dormant embryos. Oppositely correlated expression to what is expected of conventional repressors is increasing being seen in relation to miRNA–mRNA target pairs [59]. The phenomenon of co-expression was also observed in miR398-plastocyanin, in which the expression levels of both miR398 and plastocyanin were higher in germinated embryos than in dormant embryos. Plastocyanin functions as a soluble carrier transferring electrons between cytochrome b(6)f and photosystem I [60]. The expression pattern of plastocyanin was consistent with the phenomenon that genes involved in photosynthesis and carbon fixation are upregulated from dormant embryos compared to germinated embryos [61]. This was in accord with the morphology of germinated embryos (Figure 1) in which the whole embryo turned yellow–green, especially the cotyledons.

The expression level of miR160 was higher in germinated embryos than in dormant embryos by 2.7-fold, while the mRNA of the target gene ARF decreased in germinated embryos relative to dormant embryos. This was consistent with the phenomenon that negative regulation of ARF10 by miR160 plays important roles in seed germination and post-germination [36]. miR166 levels were elevated in germinated embryos and its target gene (HD-ZIPIII) showed the opposite expression pattern. Several studies suggested that miR166 regulates HD-ZIPIII expression, mediating indeterminacy in apical and vascular meristems [62], [63]. Therefore, we speculate that miR166 and the target gene HD-ZIPIII participates in embryo germination. miR397 showed a similar expression pattern with miR160 and miR166 and the target gene laccases showed the opposite expression pattern. Laccases are related to lignification and thickening of the cell wall in secondary cell growth [64]. The expression pattern of miR397-laccases accorded with cotyledon prolongation along with cell propagation. Therefore, we inferred that miR397 has an important role in regulating the thickness of the cell wall during the transition from dormant embryos into germinated embryos by cleaving the laccase mRNA.

In this study, we deciphered the endogenous “sRNAome” in dormant and germinated embryos and found that the length distribution, sRNA components, and expression pattern of miRNAs differed distinctly between dormant embryos and germinated embryos. This may be associated with differential levels of RDR2 and/or RDR6, which is regulated by hormones. These findings indicate that larches have complex mechanisms of gene regulation involving miRNAs and other sRNAs during embryo dormancy and release.

Materials and Methods

Plant Materials

One embryogenic cell line of Japanese larch (Larix leptolepis), designated D878, with a high embryo maturation capacity was used in this study. Embryogenic calluses were induced from immature embryos on induction medium, followed by subculture, and cultured on ABA-containing mature medium in a dark environment at 25±2°C. After culture for 45 days in mature medium, embryogenic calli developed into mature somatic embryos. In our study, the samples were harvested at day 57. One sample, collected after embryo maturation, continued to remain for 12 days on ABA-containing medium and another was harvested after culture for 12 days on non-ABA medium. All samples were snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored in liquid nitrogen until RNA extraction.

Measurement of the Phytohormone Content

About 0.5 g of dormant embryos and germinated embryos was ground in liquid nitrogen to fine powders and vacuum lyophilized at −20°C. For each sample, 100 mg (dry weight) of the lyophilized powders was measured for GA1, GA3, GA4, GA20, GA34, indole-3-acetic acid (IAA), ABA, and zeatin content [65], [66]. The measurement of phytohormones with LC-MS was conducted in the lab of Prof. Xiangning Jiang (Beijing Forestry University, PR China). The experiments were repeated three times with similar results.

sRNA Library Construction and Bioinformatics

The extraction of total RNA, construction of the sRNA library, sequencing, and bioinformatics was conducted as described previously [44]. The abundance profile analysis through high-throughput sequencing was based on the sequence reads of each library for the dormant embryos and germinated embryos. The first step was to normalize the miRNA sequence reads in the dormant embryos and germinate embryos to tags per million (normalized expression = actual miRNA count/total count of clean reads*1,000,000). The log2 ratio formula was log2(tpm[dormant embryos]/tpm [germinated embryos]).

Quantitative RT-PCR for miRNAs and Target Genes

sRNA was isolated using a Small RNA Isolation Kit (Biotek, Beijing, China) and cDNA was synthesized using an NCode VILO miRNA cDNA Synthesis Kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Quantitative reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) was performed using a SYBR Premix EX Taq Kit (Takara, Dalian, China) on the 7500 Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Three biological replicates for each sample were carried out. All expression levels were normalized to 5.8S ribosomal RNA (5′-GTCTGTCTGGGCGTCGCATAA-3′). Forward primers were designed based on mature miRNA sequences (Table S2). Total RNA was isolated using a Total RNA Purification Kit (Norgen Biotek Corp., Thorold, ON, Canada) and cDNA was synthesized using a Revert Aid First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Fermentas, Vilnius, Lithuania). qRT-PCR was performed as described above and all expression levels were normalized to the expression of EF-1α [67]. Primers for target genes referred to previous studies [27], [44], [68] (Table S3).

Supporting Information

Validation of the miRNA levels of dormant embryos and germinated embryos by qRT-PCR. The results of qRT-PCR validated the sequencing data, albeit with smaller fold-changes between dormant embryos and germinated embryos.

(TIF)

Expression profile of miRNAs between dormant and germinated embryos.

(DOC)

miRNA primers used for qRT-PCR in larch.

(DOC)

Primers for qRT-PCR analysis of target genes.

(DOC)

Acknowledgments

We thank Prof. Xiangning Jiang for his assistance, especially for the measurement of phytohormones with LC-MS.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the National High Technology Research and Development Program of China (grant nos. 2011AA100203, 2013AA102704) and the National Basic Research Program of China (grant no. 2009CB119106). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Pâques LE (1989) A critical review of larch hybridization and its incidence on breeding strategies. Ann Sci For 46: 141–153. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Zhang S, Zhou J, Han S, Yang W, Li W, et al. (2010) Four abiotic stress-induced miRNA families differentially regulated in the embryogenic and non-embryogenic callus tissues of Larix leptolepis . Biochem Biophys Res Commun 398: 355–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. von Arnold S, Clapham D (2008) Spruce embryogenesis. Methods Mol Biol 427: 31–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bewley JD (1997) Seed Germination and Dormancy. Plant Cell 9: 1055–1066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Finch-Savage WE, Leubner-Metzger G (2006) Seed dormancy and the control of germination. New Phytologist 171: 501–523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ammirato P (1974) The effects of abscisic acid on the development of somatic embryos from cells of caraway (Carum carvi L.). Botanical Gazette: 328–337.

- 7. Holdsworth MJ, Bentsink L, Soppe WJ (2008) Molecular networks regulating Arabidopsis seed maturation, after-ripening, dormancy and germination. New Phytologist 179: 33–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kushiro T, Okamoto M, Nakabayashi K, Yamagishi K, Kitamura S, et al. (2004) The Arabidopsis cytochrome P450 CYP707A encodes ABA 8′-hydroxylases: key enzymes in ABA catabolism. Embo Journal 23: 1647–1656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Yamaguchi S, Smith MW, Brown RG, Kamiya Y, Sun T (1998) Phytochrome regulation and differential expression of gibberellin 3beta-hydroxylase genes in germinating Arabidopsis seeds. Plant Cell 10: 2115–2126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Nambara E, Okamoto M, Tatematsu K, Yano R, Seo M, et al. (2010) Abscisic acid and the control of seed dormancy and germination. Seed Science Research 20: 55. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Jones-Rhoades MW, Bartel DP, Bartel B (2006) MicroRNAs and Their Regulatory Roles in Plants. Annu Rev Plant Biol 57: 19–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Nodine MD, Bartel DP (2010) MicroRNAs prevent precocious gene expression and enable pattern formation during plant embryogenesis. Genes Dev 24: 2678–2692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Schwach F, Moxon S, Moulton V, Dalmay T (2009) Deciphering the diversity of small RNAs in plants: the long and short of it. Brief Funct Genomic Proteomic 8: 472–481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Voinnet O (2009) Origin, biogenesis, and activity of plant microRNAs. Cell 136: 669–687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lee RC, Feinbaum RL, Ambros V (1993) The C. elegans heterochronic gene lin-4 encodes small RNAs with antisense complementarity to lin-14. Cell 75: 843–854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bruce Wightman IH, Ruvkun G (1993) Posttranscriptional Regulation of the Heterochronic Gene lin-14 by lin-4 Mediates Temporal Pattern Formation in C. elegans . Cell 75: 855–862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ghildiyal M, Zamore PD (2009) Small silencing RNAs: an expanding universe. Nature Reviews Genetics 10: 94–108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Chen XM (2005) microRNA biogenesis and function in plants. Febs Letters 579: 5923–5931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Rajagopalan R, Vaucheret H, Trejo J, Bartel DP (2006) A diverse and evolutionarily fluid set of microRNAs in Arabidopsis thaliana . Genes Dev 20: 3407–3425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Xie Z, Johansen LK, Gustafson AM, Kasschau KD, Lellis AD, et al. (2004) Genetic and functional diversification of small RNA pathways in plants. PLoS Biol 2: E104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Li F, Pignatta D, Bendix C, Brunkard JO, Cohn MM, et al. (2012) MicroRNA regulation of plant innate immune receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 109: 1790–1795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Cho SH, Addo-Quaye C, Coruh C, Arif MA, Ma Z, et al. (2008) Physcomitrella patens DCL3 is required for 22–24 nt siRNA accumulation, suppression of retrotransposon-derived transcripts, and normal development. PLoS genetics 4: e1000314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Morin RD, Aksay G, Dolgosheina E, Ebhardt HA, Magrini V, et al. (2008) Comparative analysis of the small RNA transcriptomes of Pinus contorta and Oryza sativa . Genome Res 18: 571–584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Dolgosheina EV, Morin RD, Aksay G, Sahinalp SC, Magrini V, et al. (2008 ) Conifers have a unique small RNA silencing signature. RNA 14: 1508–1515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Yakovlev IA, Fossdal CG, Johnsen O (2010) MicroRNAs, the epigenetic memory and climatic adaptation in Norway spruce. New Phytologist 187: 1154–1169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wan LC, Wang F, Guo X, Lu S, Qiu Z, et al. (2012) Identification and characterization of small non-coding RNAs from Chinese fir by high throughput sequencing. BMC Plant Biol 12: 146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Zhang J, Wu T, Li L, Han S, Li X, et al. (2013) Dynamic expression of small RNA populations in larch (Larix leptolepis). Planta 237: 89–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wu G, Poethig RS (2006) Temporal regulation of shoot development in Arabidopsis thaliana by miR156 and its target SPL3 . Development 133: 3539–3547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kasschau KD, Fahlgren N, Chapman EJ, Sullivan CM, Cumbie JS, et al. (2007) Genome-wide profiling and analysis of Arabidopsis siRNAs. PLoS biology 5: e57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wassenegger M, Krczal G (2006) Nomenclature and functions of RNA-directed RNA polymerases. Trends in Plant Science 11: 142–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Yang JH, Seo HH, Han SJ, Yoon EK, Yang MS, et al. (2008) Phytohormone abscisic acid control RNA-dependent RNA polymerase 6 gene expression and post-transcriptional gene silencing in rice cells. Nucleic Acids Res 36: 1220–1226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Li W, Cui X, Meng Z, Huang X, Xie Q, et al. (2012) Transcriptional Regulation of Arabidopsis MIR168a and ARGONAUTE1 Homeostasis in Abscisic Acid and Abiotic Stress Responses. Plant Physiology 158: 1279–1292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Achard P, Herr A, Baulcombe DC, Harberd NP (2004) Modulation of floral development by a gibberellin-regulated microRNA. Development 131: 3357–3365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Sunkar R, Zhu JK (2004) Novel and stress-regulated microRNAs and other small RNAs from Arabidopsis . Plant Cell 16: 2001–2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Reyes JL, Chua NH (2007) ABA induction of miR159 controls transcript levels of two MYB factors during Arabidopsis seed germination. Plant Journal 49: 592–606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Liu PP, Montgomery TA, Fahlgren N, Kasschau KD, Nonogaki H, et al. (2007) Repression of AUXIN RESPONSE FACTOR10 by microRNA160 is critical for seed germination and post-germination stages. Plant Journal 52: 133–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Mallory AC, Bartel DP, Bartel B (2005) MicroRNA-directed regulation of Arabidopsis AUXIN RESPONSE FACTOR17 is essential for proper development and modulates expression of early auxin response genes. Plant Cell 17: 1360–1375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Martínez-Andújar C, Martin R, Bassel G, Arun Kumar M, Pluskota W, et al. (2009) Post-Transcriptional Gene Regulation during Seed Germination and Stand Establishment. V International Symposium on Seed, Transplant and Stand Establishment of Horticultural Crops 898: 53–59. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Cairney J, Pullman GS (2007) The cellular and molecular biology of conifer embryogenesis. New Phytologist 176: 511–536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Filonova LH, Bozhkov PV, von Arnold S (2000) Developmental pathway of somatic embryogenesis in Picea abies as revealed by time-lapse tracking. Journal of Experimental Botany 51: 249–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Burge SW, Daub J, Eberhardt R, Tate J, Barquist L, et al. (2013) Rfam 11.0: 10 years of RNA families. Nucleic Acids Res 41: D226–232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kapitonov VV, Jurka J (2008) A universal classification of eukaryotic transposable elements implemented in Repbase. Nature Reviews Genetics 9: 411–412; author reply 414. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 43. Kozomara A, Griffiths-Jones S (2011) miRBase: integrating microRNA annotation and deep-sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Research 39: D152–D157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Zhang J, Zhang S, Han S, Wu T, Li X, et al. (2012) Genome-wide identification of microRNAs in larch and stage-specific modulation of 11 conserved microRNAs and their targets during somatic embryogenesis. Planta 236: 647–657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Li B, Qin Y, Duan H, Yin W, Xia X (2011) Genome-wide characterization of new and drought stress responsive microRNAs in Populus euphratica . Journal of Experimental Botany 62: 3765–3779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Rai MK, Shekhawat N, Gupta AK, Phulwaria M, Ram K, et al. (2011) The role of abscisic acid in plant tissue culture: a review of recent progress. Plant Cell, Tissue and Organ Culture (PCTOC) 106: 179–190. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Penfield S, Hall A (2009) A role for multiple circadian clock genes in the response to signals that break seed dormancy in Arabidopsis . The Plant Cell Online 21: 1722–1732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Chiwocha SD, Cutler AJ, Abrams SR, Ambrose SJ, Yang J, et al. (2005) The etr1–2 mutation in Arabidopsis thaliana affects the abscisic acid, auxin, cytokinin and gibberellin metabolic pathways during maintenance of seed dormancy, moist-chilling and germination. Plant Journal 42: 35–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Hakman I, Hallberg H, Palovaara J (2009) The polar auxin transport inhibitor NPA impairs embryo morphology and increases the expression of an auxin efflux facilitator protein PIN during Picea abies somatic embryo development. Tree Physiol 29: 483–496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Donaire L, Pedrola L, Rosa Rde L, Llave C (2011) High-throughput sequencing of RNA silencing-associated small RNAs in olive (Olea europaea L.). PLoS One 6: e27916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Lu C, Tej SS, Luo S, Haudenschild CD, Meyers BC, et al. (2005) Elucidation of the small RNA component of the transcriptome. Science 309: 1567–1569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Li A, Hu BQ, Xue ZY, Chen L, Wang WX, et al. (2011) DNA Methylation in Genomes of Several Annual Herbaceous and Woody Perennial Plants of Varying Ploidy as Detected by MSAP Plant Mol Biol Rep. 29: 784–793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Fahlgren N, Howell MD, Kasschau KD, Chapman EJ, Sullivan CM, et al. (2007) High-throughput sequencing of Arabidopsis microRNAs: evidence for frequent birth and death of MIRNA genes. PLoS One 2: e219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Pang M, Woodward AW, Agarwal V, Guan X, Ha M, et al. (2009) Genome-wide analysis reveals rapid and dynamic changes in miRNA and siRNA sequence and expression during ovule and fiber development in allotetraploid cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.). Genome Biol 10: R122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Gutmann M, Von Aderkas P, Label P, Lelu MA (1996) Effects of abscisic acid on somatic embryo maturation of hybrid larch. Journal of Experimental Botany 47: 1905–1917. [Google Scholar]

- 56. Lu C, Fedoroff N (2000) A mutation in the Arabidopsis HYL1 gene encoding a dsRNA binding protein affects responses to abscisic acid, auxin, and cytokinin. Plant Cell 12: 2351–2366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Laubinger S, Sachsenberg T, Zeller G, Busch W, Lohmann JU, et al. (2008) Dual roles of the nuclear cap-binding complex and SERRATE in pre-mRNA splicing and microRNA processing in Arabidopsis thaliana . Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105: 8795–8800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Tahir M, Law DA, Stasolla C (2006) Molecular characterization of PgAGO, a novel conifer gene of the Argonaute family expressed in apical cells and required for somatic embryo development in spruce. Tree Physiol 26: 1257–1270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Gunaratne PH (2009) Embryonic stem cell microRNAs: defining factors in induced pluripotent (iPS) and cancer (CSC) stem cells? Curr Stem Cell Res Ther 4: 168–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Cruz-Gallardo I, Diaz-Moreno I, Diaz-Quintana A, De la Rosa MA (2011) The cytochrome f-plastocyanin complex as a model to study transient interactions between redox proteins. Febs Letters 586: 646–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Finkelstein R, Reeves W, Ariizumi T, Steber C (2008) Molecular aspects of seed dormancy. Annu Rev Plant Biol 59: 387–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. McHale NA, Koning RE (2004) MicroRNA-directed cleavage of Nicoltiana sylvestris PHAVOLUTA mRNA regulates the vascular cambium and structure of apical Meristems. Plant Cell 16: 1730–1740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Williams L, Grigg SP, Xie M, Christensen S, Fletcher JC (2005) Regulation of Arabidopsis shoot apical meristem and lateral organ formation by microRNA miR166g and its AtHD-ZIP target genes. Development 132: 3657–3668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Constabel CP, Yip L, Patton JJ, Christopher ME (2000) Polyphenol oxidase from hybrid poplar. Cloning and expression in response to wounding and herbivory. Plant Physiol 124: 285–295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Liu S, Chen W, Qu L, Gai Y, Jiang X (2013) Simultaneous determination of 24 or more acidic and alkaline phytohormones in femtomole quantities of plant tissues by high-performance liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization-ion trap mass spectrometry. Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry 405: 1257–1266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Chen W, Gai Y, Liu S, Wang R, Jiang X (2010) Quantitative analysis of cytokinins in plants by high performance liquid chromatography: electronspray ionization ion trap mass spectrometry. J Integr Plant Biol 52: 925–932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Schwarzerova K, Vondrakova Z, Fischer L, Borikova P, Bellinvia E, et al. (2010) The role of actin isoforms in somatic embryogenesis in Norway spruce. BMC Plant Biol 10: 89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Li W-F, Zhang S-G, Han S-Y, Wu T, Zhang J-H, et al. (2012) Regulation of LaMYB33 by miR159 during maintenance of embryogenic potential and somatic embryo maturation in Larix kaempferi (Lamb.) Carr. Plant Cell, Tissue and Organ Culture (PCTOC): 1–6. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Validation of the miRNA levels of dormant embryos and germinated embryos by qRT-PCR. The results of qRT-PCR validated the sequencing data, albeit with smaller fold-changes between dormant embryos and germinated embryos.

(TIF)

Expression profile of miRNAs between dormant and germinated embryos.

(DOC)

miRNA primers used for qRT-PCR in larch.

(DOC)

Primers for qRT-PCR analysis of target genes.

(DOC)