Abstract

Associating with substance using peers is generally considered as one of the most important predictors of adolescent substance use. However, peer association does not affect all adolescents in the same way. To better understand when and under what conditions peer association is most linked with adolescent substance use (SU), this review focuses on the factors that may operate as moderators of this association. The review highlighted several potential moderators reflecting adolescents’ individual characteristics (e.g., pubertal status, genes and personality), peer and parental factors (e.g., nature of relationships and parental monitoring), and contextual factors (e.g., peer, school and neighborhood context). As peer association is a broad concept, important methodological aspects were also addressed in order to illustrate how they can potentially bias interpretation. Taking these into account, we suggest that, while the effects of some moderators are clear (e.g., parental monitoring and sensation seeking), others are less straightforward (e.g., neighborhood) and need to be further examined. This review also provides recommendations for addressing different methodological concerns in the study of moderators, including: the use of longitudinal and experimental studies and the use of mediated moderation. These will be key for developing theory and effective prevention.

Keywords: Peers, substance use, alcohol use, adolescence, moderation effect

1. INTRODUCTION

Youth substance use is a problem commonly encountered in societies all around the world. By grade nine, 29.8 % of adolescents in the United-States had drank alcohol in the past 30 days, 14.0% had binge drank and 30.8 % had tried marijuana at least once in their lives (Eaton et al., 2012). These rates increase during later adolescence, and the prevalence of adolescent alcohol dependency can reach 5.6% between the ages of 15 to 19 years old (Tjepkema, 2004). Although prevalence of use is lower in early adolescence, the younger teenagers are when they first try alcohol or drugs, the greater their risk for future substance use disorders and/or future psychological disorders (Chassin, Pitts, & Prost, 2002; DeWit, Adlaf, Offord, & Ogborne, 2000; Grant & Dawson, 1997; McGue, Iacono, Legrand, Malone, & Elkins, 2001). Nevertheless, substance use initiation and growth occur in the context of numerous factors, including parental influence (Bahr, Hoffmann, & Yang, 2005), personality and temperament (Wills, Windle, & Cleary, 1998) and early puberty (Ge et al., 2006; Grant & Dawson, 1998).

The strongest proximal predictors of adolescent substance use are widely acknowledged as being peer substance use and peer deviance (Akers, Krohn, Lanzakaduce, & Radosevich, 1979; Bauman & Ennett, 1996; Fallu et al., 2010). For example, affiliation with substance-using-friends strongly correlated (r=.43–.60) with adolescents’ own concurrent and future substance use (Allen, Donohue, Griffin, Ryan, & Turner, 2003; Barnow et al., 2004; Branstetter, Low, & Furman, 2011; Jackson, 1997; Reifman, Barnes, Dintcheff, Farrell, & Uhteg, 1998; Simons-Morton, 2004; Wills & Cleary, 1999). This makes peer association an ideal object of study in order to better understand influences on adolescent substance use. “Peer association” in this review, entails the ways by which substance using or delinquent peers are thought to influence, directly and indirectly, an adolescent’s – technically referred as a “target”- own substance use. This influence consists of, but is not limited to, peer pressure, perceived peer norms on substance use and/or actual peer norms on substance use. Such a definition is quite similar to the one given for peer socialization (Hoffman, Sussman, Unger, & Valente., 2006.), but since peer socialization infers a directionality more suited for experimental studies, the term ”peer association” has been chosen instead.

The relationship between peer and target adolescents is inherently reciprocal, with target adolescents also influencing their peers behavior. This reciprocity needs to be discussed in order to clarify how this review has been structured and what type of associations will be examined. Indeed, one of the most common debates in the study of peer association regards the opposition of the peer socializing (influence) theory to the peer selection theory. On the one hand, the socializing theory states that peers’ deviant behaviors and substance use are important in explaining an individual’s future actions. This theory is particularly important in explaining the role of peers on targets’ substance use and is referred to in many longitudinal studies (Reifman, et al., 1998; Sieving, Perry, & Williams, 2000; Wills & Cleary, 1999). On the other hand, the peer-selection theory states that an individual’s own deviance and substance use will influence which friends they select. This theory is also supported by a number of studies (e.g., Iannotti, Bush, & Weinfurt, 1996; Knecht, Burk, Weesie, & Steglich, 2010; Poelen, Engels, Van Der Vorst, Scholte, & Vermulst, 2007). These theories can be reconciled thanks to studies that have examined both models simultaneously through the use of a cross-lagged (or transactional) or other longitudinal designs, showing that they both have their place in the substance use literature (Burk, van der Borst, Kerr & Stattin, 2012; Dishion & Owen, 2002; Duarte, Escario, & Molina, 2011; Fergusson, Swain-Campbell, & Horwood, 2002; Kiuru, Burk, Laursen, Salmela-Aro, & Nurmi, 2010; Mercken, Steglich, Knibbe & de Vries, 2012; Poelen, et al., 2007; Simons-Morton, 2007; Wills & Cleary, 1999). However, Jaccard and colleagues (2005) appropriately point out that cross-sectional designs confound the effects of peer socialization and peer selection. Therefore, longitudinal studies are required to circumvent the directionality issue inherent in cross-sectional studies. Moreover while some longitudinal observational studies can suggest causal links, experimental studies (e.g., using ethical proxies for adolescent substance use) are required to properly address them.

This review does not aim to clarify the debate between the relative contribution of peer socialization and selection, largely because the proportion of studies which examine moderation of the link between “peer socialization” and substance use in adolescence severely outweighs that of studies of “peer selection”, and the number of studies which compare both models is even further limited. This opposition however highlights the importance of putting greater emphasis on the results from longitudinal and experimental studies and it explains why the articles in this review are subdivided by study design. Thus, this review focuses on studies that investigated moderators of “peer association” rather than moderators of “peer socialization” or “peer selection”.

As stated previously, there is general consensus regarding the importance of peer deviance and peer substance use on the substance use behavior of targets. There is however, less agreement as to when and under what conditions peers are most influential. The variables representing these conditions are called moderators. A moderator refers to “a qualitative (e.g., gender, race, class) or quantitative (e.g., level of reward) variable that affects the direction and/or strength of the relation between an independent or predictor variable and a dependent or criterion variable” (Baron & Kenny, 1986). Studying moderators of peer association on target substance use behaviors such as substance use experimentation, quantity, and frequency is important. For instance, it can help to identify the conditions under which the effect of peer association varies, to clarify discrepancies across previous studies and to produce findings that could feed directly into prevention and early intervention approaches by pinpointing, for example, exacerbating factors that could be mitigated and protective factors that could be promoted. Accordingly, the main goal of this review is to examine how certain factors may exacerbate or dampen the link between peer substance use and adolescents’ substance use and help address the orientation future studies should take.

Moderators in this review are expected to function in one of three ways, in accordance with three theoretical models that account for the interplay between individual characteristics and the environment: the diathesis–stress model (Goldstein, Abela, Buchanan, & Seligman, 2000), the resilience model (Fergus & Zimmerman, 2005; Kaplan, 1999), also known as the social development model (Catalano, Kosterman, Hawkins, Newcomb, & Abbott, 1996), and the differential susceptibility model (Belsky, Bakermans-Kranenburg, & van IJzendoorn, 2007). Firstly, the diathesis-stress model states that an individual’s vulnerability to psychopathology and substance use (e.g., high impulsivity) will be exacerbated by a negative or stressful environment (e.g., deviant or substance-using peers). Secondly, the resilience and/or the social development models posit that individual factors may reduce sensitivity to adverse environmental factors, such as peer deviance. Thirdly, the differential susceptibility model states that, although an individual’s vulnerability may be exacerbated by a negative environment or by stress, so called “vulnerable” individuals may benefit most from supportive environments. In this way, significant moderators could theoretically increase or decrease the effect of peers on substance use behaviors and the concept of “vulnerability” may be inappropriate for those whose “sensitivity” provides a benefit under certain conditions. Furthermore, it is important to note that the diathesis-stress and resiliency models can be complementary. That is, observing an interaction between an individual factor and an environmental stressor could support both the diathesis-stress and resiliency models, depending on how the valence of the individual factor is conceptualized, as in their simplest form, both of these models could be seen to be examining different ends of a same continuum. In addition, these models were developed to account for observed interactions between individual vulnerability factors and environmental factors. However, we also report environment by environment interactions, with either increasing or decreasing effects. Although the theoretical models summarized above do not specifically address environment by environment interactions, such interactions may be interpreted with these theoretical models. These three models were also chosen because most studies, in the literature on moderators of the effect of peer association on substance use, are not based on any a priori theoretical model. Rather, they are usually data driven and based on expected outcomes provided by previous studies (i.e., higher or lower target substance use). A summary of what model is best supported by the literature will be provided for each proposed factor in the summary and implication sections.

2. METHOD AND REVIEW STRUCTURE

In the current review, substance use refers to alcohol and other drug use (i.e., marijuana, cocaine, crack, tranquilizers, sedatives, psychedelics, amphetamines, LSD, speed). Tobacco use is outside the scope of this review and a number of reviews of potential moderators of the effect of peer association on adolescent tobacco use have been published (e.g., Hoffman, Sussman, Unger, & Valente, 2006; Kobus, 2003; Simons-Morton & Farhat, 2010).

Studies included in this review were identified through a literature search using Web of KnowledgeSM, Psych Info® and PubMed. Keywords included in the search were “adolescent substance use”, “moderators of peer influence”, “moderators of peer selection”, “moderators of substance use”, “moderators of alcohol use” and “moderators of peer association”. To be included in the review, the selected study needed to have been published between 1991 and 2013 in a peer reviewed journal and be written in English. Studies were then sorted by title and abstract information, discarding irrelevant studies (i.e., not referring to substance use, adolescents or peers). This step resulted in over 350 studies being kept. The method and analysis sections were then examined: assuring that participants in those studies were within the right age range (i.e., the outcome variable being measured between 12 years and 18 years of age), that the outcome variable included substance use and that authors actually examined moderation with peer association or influence being the predictor variable. Relevant studies on moderators of peer association or influence which were cited in those articles were also included in this review, bringing the total of articles retained for this review to 58.

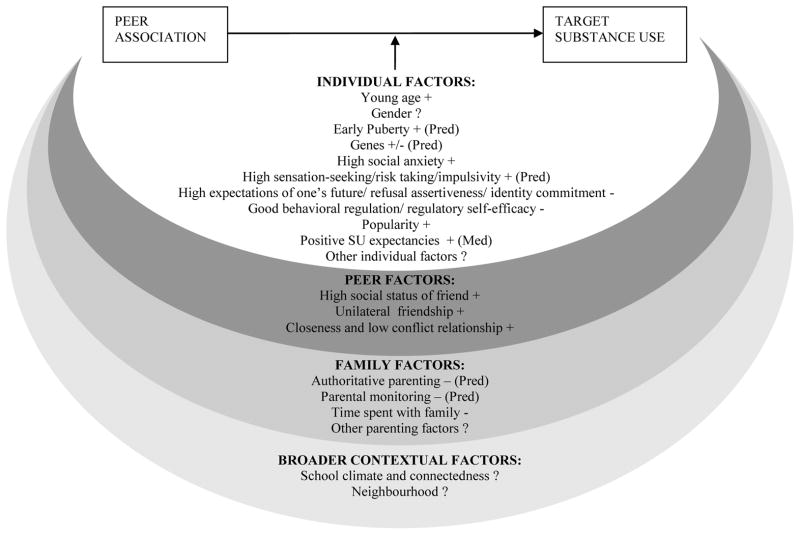

Structurally, this review of moderators has been divided by level of influence in accordance to their degree of proximity to the adolescents as follows: 1) individual factors, 2) peer and parental factors and 3) broader contextual factors (see Table 1). This structure is similar to the one proposed in Bronfenbrenner’s (1977) ecological model, which conceptualizes interpersonal interactions as part of broader socio/environmental contexts, and takes into account the reciprocal influences between them. Other models such as the triadic influence theory (Flay., 1999; Flay, Petraitis, & Hu, 1995) and the integrative model (Fishbein, 2000; Fishbein, 2009) also highlight the interplay between different levels of influence to predict behavior, and are particularly useful in explaining the sequence of mediated links between environmental or distal factors and behaviors. Since the focus of the review is on moderated effects, rather than mediation, and the main purpose of the model was to provide a simple and clear structure to the review, the Bronfenbrenner model was chosen over the other two models. Moreover, as mentioned previously each section has been further subdivided according to the methodological design of these studies as follows: 1) cross-sectional studies; 2) longitudinal studies, and 3) experimental studies. This distinction enabled us to organize the review more critically as a function of the strength of evidence. Finally, because most studies assessed peer association and behavior through target-reported data as a default (e.g., adolescents reporting on their friends’ substance use), we have only specified when peer association or behavior was assessed through another means such as peer-reports or third-party informants (please see Table 1 for how peer association and behavior was assessed in each of the studies reviewed). This methodological issue has been further discussed in the methodological and theoretical framework section.

Table 1.

Studies† examining moderators of the effect of peer association on adolescent substance use by level of moderating factor and study design.

| Moderator Level | Study Design | Authors, Year | Sample | Measures

|

Results | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peer association | Moderator | Outcomes | |||||

| Individual | Experimental | Cohen & Prinstein, 2006 | 43 Caucasian boys (age 16–17 years) from USA. | High vs low status Peers, experimental conditions |

Social Anxiety Scale for Adolescents (SAS-A) |

Public and private self-reported conformity with regard to aggressive and health risk behavior, including substance use; hypothetical scenario instrument | Low status peers exerted influence on public conformity to health risk behaviors only for adolescents high in social anxiety. While high status peers exerted influence on all participants regardless of social anxiety. |

| Chein et al., 2011 | 40 girls and boys, 3 groups: adolescent (mean age 15.7), young adult (mean age 20.6) and adult (mean age 25.6) | Presence of peers during experiment vs. alone | Target’s age | Risk taking assessed with a stop driving task. Activation in reward-related brain regions. |

Adolescents, but not adults, took more risks when observed by peers. Adolescents demonstrated greater activation in reward-related brain regions when observed by peers. |

||

| Longitudinal | Henry et al., 2005 | 1065 boys and girls (mean age 12.35 at baseline) from the USA | Self-report proportion of friends that drink |

Perceived Harm: beliefs about the effect of alcohol use on future aspirations. Risk-taking: willingness to engage in risky activities. |

Self-reported drinking frequency, intoxication, number of drinks, extent of typical drinking, self identification as a user, intention to use alcohol in the future. | The link between friends’ and targets’ alcohol use was lower with increases in perceived harm, but greater with increases in risk-taking. | |

| Allen et al., 2005 | 185 girls and boys (mean age 13.36) from the USA | Self-reported peer valuing of behavioral misconduct: Peer Pressure Inventory | Popularity: adolescents named 10 individuals they most and least would like to spend time with on weekend | Self-reported alcohol and substance use frequency (last 30 days) | Stronger link between perceived peer valuing of behavioral misconduct and targets’ alcohol and substance use frequency with high popularity. | ||

| Rabaglietti et al., 2012 | 457 girls and boys, aged 14 to 20 years old (M = 16.1) from Italy | Peer reported alcohol Intoxication Frequency |

Regulatory Self-efficacy (RSE) Gender |

Alcohol Intoxication Frequency | Lower levels of alcohol intoxication in adolescents with alcohol using friends who had higher RSE, compared to those with average or low RSE. No significant interaction with gender. |

||

| Fallu et al., 2010 | 1037 Caucasian boys (from ages 6 to 15 years) from Canada | Self-reported Peer conventionality: Friends’ school liking and Friends having trouble with the police (reversed). | Childhood disruptiveness: Teacher-rated Social Behavior Questionnaire. | Self-reported heavy Substance use: Frequency of tobacco and drug use by frequency of alcohol intoxication episodes in the past 12 months, at 14–15 years. | Stronger link between low peer conventionality and targets’ heavy substance use with childhood disruptiveness. | ||

| Larsen et al., 2010 | 1,232 girls and boys (11- to 15-year-old) from the Netherlands. | Friend’s reported alcohol use. | Gender Self-esteem and self control: assessed via the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale | Self-reported number of alcoholic beverages consumed in the last week | No significant interaction. | ||

| Marshal & Chassin, 2000 | 300 girls and boys (mean age 12.7) from the USA | Self-reported peer group affiliation assed by peer substance use and peer tolerance of adolescents’ substance use | Gender Consistency of Parental Discipline: Parent-reported, adapted from the Children’s Reports of Parental Behavior Inventory | Self-reported alcohol use frequency | In a three-way interaction only: link between peer influence on future substance use decreased for girls but increased for boys as a function of good parental discipline. | ||

| Guo et al., 2002 | 808 boys and girls (mean age 10.8) from USA | Self-reported peer antisocial activities | Gender | Self-reported illicit drug use and alcohol use (yes/no): crack, cocaine, amphetamines, tranquilizers, sedatives, psychedelics, alcohol, tobacco | No significant interaction. | ||

| Crosnoe et al., 2002 | 3,046 adolescent girls and boys (grades 9 to 12) from USA | Friend-reported Deviancy and substance use, alcohol use and marijuana | Gender | Self-reported delinquency including: substance use cigarette use, alcohol use and marijuana | Stronger link between friend’s alcohol use and target’s Delinquency in boys | ||

| Duncan et al., 1994 | 517 girls and boys (mean age 13.11) from the USA | Self-reported peer encouragement of alcohol use. | Age | Self-reported alcohol use frequency and present alcohol use | Stronger link between deviant peer affiliation and targets’ alcohol abuse/dependence in early as opposed to later adolescence. | ||

| Fergusson et al., 2002 | 1,265 girls and boys (followed from 14 to 21 years) from New Zealand | Self-reported deviant peer affiliation: friends’ substance use, truancy and/or law braking | Age | Self-reported alcohol abuse/dependence assed with the Alcohol Problem Index (RAPI: White & Labouvie, 1989) | Stronger link between deviant peer affiliation and targets’ alcohol problems in mid as opposed to later adolescence/early adulthood. | ||

| Li et al., 2002 | 188 girls and boys (mean age 14) from the USA | Self-reported exposure to Deviant Peers (including alcohol and substance use) | Alcohol trajectory: initial low levels of alcohol use frequency from 14 to 18 years | Self-reported alcohol use: composite measure of 3 items | Stronger link between peer influence and target’s alcohol use across adolescence in those who showed low levels of alcohol use at age 14. | ||

| Ge et al., 2006 | 896 girls and boys (mean age 11.10) from the USA | Self-reported number of friends who use substances | Pubertal timing using the Pubertal Development Scale (self-report) | Self-reported intention and willingness to use substances. | Stronger link between friends’ substance use and intention and willingness to use substances in early puberty. | ||

| Costello et al., 2007 | 1420 girls and boys (aged 9–13) from the USA | Association with self-reported deviant peers | Early maturation: tanner stage IV by age 12 | Alcohol use onset and disorder over the past 3 months assessed by diagnostic interview of parents and adolescents | Stronger link between deviant peers and targets’ alcohol use with early maturation. | ||

| Mrug et al., 2009 | 500 girls and boys (followed from 11 to 13 years) from the USA | Teacher-rated peer deviancy | Childhood antisocial behavior: Parent-reported targets’ oppositional behavior and conduct problems at 11 years | Self-reported externalizing behaviors: 27 different delinquent acts in the past 12 months including substance use at 13 years | Stronger link between peer deviance and targets’ externalizing behaviors with a history of childhood antisocial behavior. Gender, n.s. | ||

| Allen et al., 2012. | 157 adolescents (M= 13.35) from Southeastern US. | Self-reported friends alcohol and marijuana use frequency (past 30 days). |

Gender Observed autonomy difficulties with mothers (recantation from original point of view). Autonomy difficulties (in general) Self-reported social skills in handling deviancy Susceptibility to peer influence (composite measure of all other measures). |

Alcohol and marijuana use frequency (past 30 days). | Weaker link between peer substance use and target substance use for those with better skills in handling deviance. Stronger link between peer substance use and target substance use for those who more easily recanted on their position (Autonomy difficulties). Stronger link between peer substance use and target substance use for those who had higher scores on the composite susceptibility risk measure. |

||

| Westling et al., 2008 | 528 boys and girls from the US (mean= 10.5) | Deviant peer association (target, parent and teacher reported) | Gender | Alcohol use initiation (yes/no) | No significant interactions with peer association were found. | ||

| Longitudinal and Cross-sectional | Stattin et al., 2011 | 634 (cross-sectional) and 434 girls for Sweden (longitudinal; mean age= 14.42) | Peer involvement |

Pubertal timing (age of first menarche) Youth center participation (Attending youth center in town) |

Delinquency (including cannabis use.) | Longitudinal: no significant interactions were found. Cross-sectional: Higher delinquency in girls that spent more time with peers and were early matures. Higher delinquency in girls that spent more time with peers and frequented more regularly the youth center, especially those that were early matures. |

|

| Cross-sectional | Denault et al., 2012 | 185 8th and 9th graders (M= 14.34) from Quebec Canada | Deviancy in the activity peer group (including alcohol and drug use). |

Gender Age |

Substance use frequency in the past month (alcohol, drugs and cigarettes) | No significant interactions. | |

| Epstein & Botvin, 2002 | 2400 early adolescent boys and girls (mean age 12.4) from the USA | Self-report proportion of friends that drink |

Risk-taking (RT): 7 items from the Eysenck IVE scale. Refusal assertiveness (RA): 3 items from the Gambrill-Richey Assertion Inventory |

Self-reported drinking quantity, drinking frequency and drunkenness | Stronger link between friends’ alcohol use and drinking quantity and frequency with high RT and poor RA. Stronger link between peer alcohol use and target drunkenness with poor RA. |

||

| Fergusson et al., 2007 | 265 early adolescent boys and girls (mean age 13.4) from Canada | Friend’s reported delinquent and SU behaviors | Puberty: Pubertal Development Scale (self-report) | Self-reported delinquent and SU behavior | Stronger link between peer delinquency and target delinquency with earlier pubertal development. | ||

| Wills et al., 2011 | 1 307 boys and girls from the US | Friends substance use (alcohol, marijuana and cigarette) | Good behavioral self-control Poor behavioral regulation Good emotional self-control Poor emotional regulation Academic involvement Negative life events | Substance use level (alcohol, marijuana and cigarettes) | Lower substance use in those with lower behavioral regulation. No other significant interactions were found. |

||

| MacNeil et al., 1999 | 779 adolescents (mean age 12.81) from the US | Self-report proportion of friends use alcohol, or drugs | Future expectations: Scale created by Brooks, Stuewig, and LeCroy (1998). | Self-reported lifetime Substance Use scale from the Youth Plus Survey | Weaker link between friend’s substance use and targets Lifetime substance use with higher future expectations. | ||

| Knyazev et al, 2004 | 4501 students (14 to 25 years old) from Russia | Self-reported friends’ drug use |

Behavioral activation system (BAS): self-reported impulsivity and sensation seeking using the Gray–Wilson Personality Questionnaire Extraversion: self reported using a shorted Russian version of the Eysenck’s personality factors. |

Self-reported composite score of having used drugs, wanting to use drugs, type of drug use and frequency of drug use | Stronger link between friends’ drug use and targets’ (composite) drug use at both high BAS and Extraversion. | ||

| Clark et al., 2012. | 567 9 to 21 year old African Americans from the USA (M=15.27) | Peer problem behavior (including substance use). |

Drug and Alcohol Refusal Efficacy, Gender |

Past 30-day alcohol use and past 30-day marijuana use. | Stronger link between deviant peers and marijuana for males. | ||

| Bergh et al., 2011. | About 9900 adolescents (aged 15–16) from Sweden. | Peer activity level (how often the targets spend time with their friends; does not asses if friend use substances) |

Gender Academic orientation Year of investigation. |

Alcohol use frequency past year. | No significant interactions were found. | ||

| Dumas et al., 2012 | 1070 adolescents aged from 14 to 17 years old (M= 15.45) from Canada | Peer group pressure, 2 items (to do things the target didn’t want or to drink, smoke and try drugs) Peer group control, 5 items (assessing to what extent some members of the group try to control the other members.) |

Identity commitment (16 items). Items included information on: future occupation, religion, politics, relationships, family, friends, dating partners, sex roles, and personal values. | Substance use (frequency of alcohol use, binge drinking and marijuana use over the past three months). | Weaker link between peer group pressure and substance use in those with high identity commitment. Higher substance use in adolescents with both controlling groups and high identity commitment. | ||

| Trucco et al., 2011 | 387 girls and boys (mean age 11.60) from the USA | Self-report Perceived peer approval of alcohol and tobacco use. | Agentic and Communal Goals: Self-report using revised version of the Interpersonal Goals Inventory for Children | Self-reported intention to use alcohol and cigarettes: 4 items from the Monitoring the Future Project | Agentic goals, n.s. A trend for a stronger link between perceived peer approval of alcohol use and target’s intention to use alcohol with high communal goals. | ||

| Guo et al., 2009 | 600 pairs of same sex siblings (mean age 16.1) from the US | Friends’ reported drinking | Genetic Heritability calculated through twin modeling | Self-reported drinking frequency | The genetic contribution to target alcohol use is stronger at higher levels of friends’ drinking. | ||

| Harden el al., 2008 | 1,636 sibling pairs (mean age 16.1) from the US | Best friend’s-reported drinking and smoking | Genetic Heritability | Self-reported drinking and smoking frequency | Stronger link between and target substance use in adolescents with high genetic liability to substance use. | ||

| (the study is longitudinal but was analyzed Cross-sectionally) | Dick et al., 2007 | 2918 same sex twins (17 years) from Finland | Self-report proportion of friends that drink | Genetic Heritability | Self-reported alcohol use frequency at 17 years | Stronger genetic heritability for alcohol use in adolescents with many alcohol using friends. | |

| Miranda et al., 2013 | 104, boys and girls 12 to 19 years old (M = 15.60, SD = 1.77). | Self-reported deviancies (i.e., friends substance use, and perceived friends reaction to targets’ substance use) | Genotype OPRM1 (A and G allele carriers) | Alcohol use disorder (AUD) | Higher links between G allele carriers an AUD in adolescents with delinquent peers. | ||

| Cross-sectional | Kendler et al., 2011. | 1796 adult male twins from the US. | Peer group deviance | Genetic risk for AUDs (history of alcohol abuse and dependence by the target’s parents and co-twin) | Alcohol use frequency by month. | At 12 to 14 years old there was higher alcohol use for those with both the genetic risk-factor and deviant peers. | |

| Anderson et al., 2011 | 1571 girls and boys (13 years) from the USA | Self-report proportion of friends that drink |

Gender Social Anxiety Assessed with the Social Anxiety Scale for Adolescents– Revised (SAS-A) |

Self-reported alcohol use quantity (30 day period) | Stronger link between perceived peer alcohol use and target’s alcohol use quantity in girls. Stronger link between peer and target alcohol use, in adolescents that had a strong need for affiliation and were high in social anxiety. Stronger link between peer alcohol use and target binge drinking in boys who were socially anxious. |

||

| Bobakova et al., 2012. | 1052 boys and girls (M= 14.68) from Eastern Slovakia. | Friends alcohol use (at least once a week) |

Gender Ethnicity |

Having been drunk in the past month (yes/non) | No significant interactions were found. | ||

| Mennis et al., 2012 | 254 adolescent primary care patients at a Philadelphia Department of Public Health (ages 13 to 20) | Social network quality (Perceived friends substance use, if friends have tried to influence their substance use and positive activities with these friends). |

Gender Age |

Alcohol and Drug Involvement | Higher substance use in adolescents which both have low social network quality and are older. | ||

| Burk et al., 2012. | 950 4th, 7th and 10th graders from Sweden | Self-reported past year frequency of alcohol intoxication. |

Gender Grade |

Past year frequency of alcohol intoxication. | No significant interactions were found. | ||

| Gaughan, 2006 | 2980 best friend dyads (boy-boy, girl-girl and girl-boy; mean age 16.55) from the USA | Peer reported drunkenness frequency assed by one item | Friend’s Gender | Self-reported drunkenness frequency assed by one item | Positive link between male alcohol using peers and female targets’ drunkenness, but no link between female alcohol using peers and male targets’ drunkenness. | ||

| Ferguson et al., 2011 | 8,256 girls and boys (mean age 14) from the USA | Self-reported peer delinquency, assed by 11 items including 4 items on substance use | Age | Self-reported alcohol use (7 items) and illegal substance use (14 items) | Stronger link between peer delinquency and target substance use when targets were between the ages of 13 and 16 years old as opposed to older. | ||

| Kelly., 2012 | 7064 adolescents in grade 6 (M= 11 years old) and grade 8 (M= 13 years old) from Australia. | Number of friends which have tried alcohol without their parent’s knowledge in the past 12 months (0 to four). | Age (grade 6 or 8) | Past 30 days alcohol use frequency | In 8th grade: weaker link between having one peer who tried alcohol and targets alcohol use. No significant interaction between grade level and having two, three or four friends who have tried alcohol. |

||

| Miranda et al., 2012 | 429 boys and girls (M = 15.74 and SD = 0.82) from Québec, Canada | Peer reported Substance Use (Alcohol, Cannabis and cigarette) | Fantasizing while listening to music | Substance Use (Alcohol, Cannabis and cigarette) | Lower Substance Use in highly musically involved adolescents with substance using peers who fantasized while listening to music. No significant interaction effect in adolescents who were moderately musically involved. |

||

| Peer | Experimental | Teunissen et al., 2012 | 74 male adolescents from the Netherlands | pro-alcohol and anti-alcohol norms in a simulated chat-room | Classroom Peers’ popularity | Willingness to Drink | Higher willingness to drink when pro-alcohol norms were given by more popular peers. Lower willingness to drink when anti-alcohol norms were given by more popular peers. |

| Longitudinal | Bot et al., 2005 | 1276 girls and boys (12–14 years) from the Netherlands | Best friend’s reported number of alcoholic beverages consumed in the past week |

Unilateral friendships: Non-reciprocated friendship Popularity: 5 most and least popular adolescents as nominated by the class. |

Self-reported number of alcoholic beverages consumed in the past week | Stronger link between peer alcohol use and target alcohol use in unilateral friendships. Stronger link between peer alcohol use and target alcohol use when peer is of higher status. |

|

| Urberg et al., 1997 | 1,028 girls and boys (in 6th, 8th, and 10th grades) from the USA, followed for one school year | Friend’s reported alcohol use. |

Friendships stability: Target’ nominated best friend at wave 1 and wave 2. Quality/closeness of friendship: friendship qualities scale. |

Target’s self-reported alcohol use and drinking to intoxication. | Friendship stability, n.s. Stronger link between peer and target alcohol use as a function of increased quality/closeness of friends. | ||

| Poelen et al, 2007 | 416 girls and boys (13 to 16 years) from the Netherlands | Self-reported friends frequency and quantity of alcohol used. |

Quality of friendship: Quality of Friendship Scale Friend’s popularity: 5 items from Differential Peer Popularity Scale. A subscale of the sibling inventory of differential experience |

Self-reported number of alcoholic beverages consumed in the past week | Quality of friendship and Friend popularity, n.s. | ||

| Fallu et al, 2010 | 1037 boys (6 to 15 years) from Canada | Self-reported peer conventionality: Friends’ school liking and Friends having trouble with the police (reversed) | Attachment to friends: Communication, affective assimilation and support between friends | Self-reported frequency of tobacco and drug use by frequency of alcohol intoxication episodes in the past 12 months, at 14–15 years. | Stronger link between peer conventionality and future target substance use as a function of attachment to friends. | ||

| Allen et al., 2012. | 157 adolescents (M= 13.35) from Southeastern US. | Self-reported friends alcohol and marijuana use frequency (past 30 days). | Close friend social acceptance (using a limited nomination sociometric procedure) | Alcohol and marijuana use frequency (past 30 days). | Stronger association between peer substance use and target substance use for those with socially accepted peers. | ||

| Cross-sectional | Denault et al., 2012 | 185 8th and 9th graders (M= 14.34) from Quebec Canada | Deviancy in the activity peer group (including alcohol and drug use). | Type of activity (sport vs non sport), | Substance use frequency in the past month (alcohol, drugs and cigarettes) | Higher substance use in those adolescents with deviant peers and participating in sport activities | |

| Burk et al., 2012. | 950 4th, 7th and 10th graders from Sweden | Self-reported past year frequency of alcohol intoxication. | Reciprocity of the relationship | Past year frequency of alcohol intoxication. | No significant interactions were found. | ||

| Parents/Family | Longitudinal | Kiesner et al., 2010 | 151 girls and boys (mean age 14) from Canada | Self-reported substance co-use with friends | Parental monitoring: Parent Monitoring measure (Kerr & Stattin, 2000) | Self-reported substance use frequency | Weaker link between substance co-use between friends’ and targets’ substance use frequency as a function of good parental monitoring. |

| Mason et al., 1994 | 148 girls and boys (mean age 14) from the USA | Self-reported peer’s problem behavior from Problem behavior scale | Parental monitoring: Mother-rated subscale of the inventory of parent and peer attachment. | Self-reported problem behavior from problem behavior scale, including gang activity, drug use, stealing. | Weaker link between peer’s and target’s problem behavior as a function of good parental monitoring. | ||

| Nash et al., 2005 | 2573 girls and boys (mean age 15.5) from the USA | Self-reported Peer influence: 3 items on peer acceptance of alcohol use and 1 item on number of friends who drink alcohol. | Parental monitoring: Adolescent version of the Assessment of Child Monitoring Scale. | Target self-reported drinking behavior: Alcohol use frequency, quantity and frequency of alcohol use problems | Weaker link between peer influence and adolescent drinking behavior as a function of good parental monitoring. | ||

| Mounts et al., 1995 | 1000 girls and boys (9th to 12th grade) from the USA | Friend’s reported drug use | Perceived Authoritative parenting: Acceptance-Involvement and Strictness-Supervision. | Self-reported drug use frequency | Weaker link between peer and target drug use as a function of authoritative parenting. | ||

| Sullivan et al., 2004 | 1,282 girls and boys (6th grade) from the USA | Self-reported Witnessing violence: 6 item scale from the Children’s Report of Exposure to Violence | Parental monitoring: monitoring scale from the Alabama Parenting Questionnaire | Self-reported substance use initiation: Cigarettes, beer, wine and liquor | Weaker link between witnessing peer violence and target substance use initiation as a function of parental monitoring. | ||

| Mrug et al., 2009 | 500 girls and boys (followed from 11 to 13 years) from the USA | Teacher-rated peer deviancy: the Social Behavior Questionnaire (Tremblay et al., 1991) | Negative parenting: 13 items reverse coded on (nurturance, harsh discipline, and inconsistent discipline) | Self-reported externalizing behaviors: 27 different delinquent acts in the past 12 months including substance use | Stronger link between peer deviancy and target’s externalizing behaviors as a function of negative parenting. | ||

| Allen et al., 2012. | 157 adolescents (M= 13.35) from Southeastern US. | Self-reported friends alcohol and marijuana use frequency (past 30 days). | Maternal support (supportive behavior interaction task) | Alcohol and marijuana use frequency (past 30 days). | Weaker link between peer substance use and target substance use for those with maternal support. | ||

| Lee., 2012 | 3,125 high school students from south Korea, (10 graders assessed for 3 years) | Peer substance use (number of friends who use alcohol and tobacco) |

Parent– adolescent relationship quality (6 items) Parental monitoring (4 items) |

Substance use frequency (alcohol and tobacco) | Weaker link between peer substance use and targets substance use in teens with a better parent-adolescent relationship. No significant moderating effect for parental monitoring. | ||

| Trucco et al., 2011. | 371 girls and boys (11 to 13 years old) from the US. | Perceived peer approval and use of alcohol. | Parental control and Parental warmth | Alcohol use initiation (yes/no) | No significant interactions were found. | ||

| Cross-sectional | Denault et al., 2012 | 185 8th and 9th graders (M= 14.34) from Quebec Canada | Deviancy in the activity peer group (including alcohol and drug use). | Degree of adult supervision during activity. | Substance use frequency in the past month (alcohol, drugs and cigarettes) | No significant interactions. | |

| Wood et al., 2004 | 578 girls and boys (mean age 18) from the USA | Self-reported peer influence: Alcohol offers (4 items), social modeling (3 items) and perceived norms (10 items) |

Parental monitoring: modified version of the Strictness–Supervision scale (Steinberg et al., 1992). Parental permissiveness toward alcohol: targets perception of what parents consider an appropriate amount of drinking. Parental attitudes and values: perceived parental disapproval for heavy drinking, and permissiveness for alcohol use |

Self-reported binge drinking: 5 or more drinks in one sitting. | Weaker link between peer influence and binge drinking as a function of parental monitoring, low parental permissiveness and parental attitudes and values. | ||

| Clark et al., 2012. | 567 9 to 21 year old African Americans from the USA (M=15.27) | Peer problem behavior (including substance use). | Parental Attitudes Toward Substance use Parental monitoring, | Past 30-day alcohol use and past 30-day marijuana use. | Weaker link between deviant peers and alcohol and marijuana use in those with higher parental monitoring. No other significant interactions were found. | ||

| Bergh et al., 2011. | About 9900 adolescents (aged 15–16) from Sweden. | Peer activity level (how often the targets spend time with their friends; does not asses if friend use substances) | Parental monitoring (1 item assessing how often the target tells parents where he or she is). | Alcohol use frequency past year. | Stronger link between peer activity frequency and alcohol use frequency in those with lower parental supervision. | ||

| Bobakova et al., 2012. | 1052 boys and girls (M= 14.68) from Eastern Slovakia. | Friends alcohol use (at least once a week) | Parental monitoring | Having been drunk in the past month (yes/non) | Higher odds of drunkenness in girls with both alcohol using peers and low parental monitoring. | ||

| Warr, 1993 | 1,726 girls and boys (13 to 19 years old) from the USA | Self-reported number of friends that commit delinquent acts: cheating at School, marijuana, burglary, alcohol use, petty larceny and grand larceny |

Time spent with family: during afternoons, evenings, and weekends Attachment to parents: 3 items created by researchers |

Target’s self-reported delinquency: cheating at School, marijuana, burglary, alcohol use, petty larceny and grand larceny | Weaker link between friends’ and targets’ delinquency as a function of time spent with family. Attachment to parents, n.s. | ||

| Broader Context | Longitudinal | Mrug et al., 2009 | 500 girls and boys (followed from 11 to 13 years old) from the USA | Teacher-rated peer deviancy: the Social Behavior Questionnaire (Tremblay et al., 1991) | School connectedness: three items from the Attitudes Toward School Scale (Institute of Behavioral Science, 1987) and five items from the School Connectedness Scale (Sieving et al., 2001) | Self-reported externalizing behaviors: 27 different delinquent acts in the past 12 months including substance use | School connectedness, n.s. Ethnicity, n.s. |

| Crosnoe et al., 2002 | 3,046 girls and boys (grades 9 to 12) from USA | Friend reported deviance including substance use alcohol marijuana | Ethnicity School connectedness: bonding to teachers, Academic achievement and orientation to School | Self-reported delinquency including substance use: cigarette, alcohol marijuana. | Weaker link between peer and target delinquency as a function of bonding to teachers, academic achievement and orientation to school. | ||

| Zimmerman et al, 2011 | 1 639 boys and girls from the US (9 to 17 years old). | Friends substance use (alcohol, marijuana tobacco) | Neighborhood opportunities for crime | Substance use (alcohol, marijuana, tobacco and illicit drugs) | Within neighborhoods with low opportunities for crime, the effect of peers was initially small, but as peer substance use increased, the effect of peers increased multiplicatively. Within neighborhoods with more opportunities for crime, the effect of peers was initially strong, but decreased as peer substance use increased, suggesting a ceiling or saturation effect. | ||

| Cross-sectional | Dickens et al., 2012 | 2 582 American Indian and/or Alaskan Native Students from the USA (11 to 19 years old) | Peer alcohol use (tree items assessing number of friends who get drunk, get drunk once in a while and almost every week-end). | School bonding (4 items assessing if the target likes school, is liked by teachers, likes his teachers and finds school fun). | Alcohol use (composite measure of lifetime alcohol use, alcohol use frequency, drunkenness and alcohol use consequences) | For those under 16 years old: Weaker link between peer alcohol use and target’s alcohol use in those with higher school bonding. No significant interaction with school bonding for those who are over 16 years old. |

|

| Snedker et al., 2009 | 2,006 girls and boys (13 to 21 years old) from USA. | Self-reported peer deviancy, including substance use. | Disadvantaged Neighborhood: percentages of residents below the federal poverty level, female-headed households, residents receiving public assistance, and unemployment) | Self-reported substance use frequency: alcohol and marijuana | Weaker link between peer deviancy and target substance use frequency in disadvantaged neighborhoods. | ||

Studies are repeated if they included moderators at different levels of analyses (e.g., if individual and contextual moderating factors are included in the study, it will appear under both sections)

3. RESULTS

3.1. Findings overview

Out of the 58 studies retained, three were experimental, 28 were longitudinal and 27 were cross-sectional. Most studies reviewed (i.e., 44) examined at least one personal factor as possible moderator of peer association. Nine studies examined peer factors as possible moderators, 15 examined parental or family characteristics, and five studies tested broader contextual factors as possible moderators. Out of the 58 studies, four included boys only and one included girls only. For information on available study designs, number of articles and mean age of participants for each subcategory, see Table 2.

Table 2.

Descriptive characteristics of subcategories.

| Subcategory | Number of articles reviewed | Mean age of participants (years) | Study design not available |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 10 | 13.92 | All Available |

| Gender | 16 | 15 | Experimental |

| Pubertal status | 3 | 12.2 | Experimental |

| Genetic vulnerability | 5 | 16.2 | Longitudinal and Experimental |

| Personality | 16 | 13.91 | All Available |

| SU expectancies and motives | 1 | 14.04 | Cross-sectional Experimental |

| Peer Relationship characteristics | 10 | 12.77 | All Available |

| Parental factor | 17 | 14.29 | Experimental |

| School Context | 3 | 14.8 | Experimental |

| Neighborhood context | 2 | 17 | Experimental |

3.2. Individual Factors

3.2.1. Age

Alcohol and drug use initiation, as well as frequency of use, have been shown to increase substantially with the onset of adolescence, and to continue increasing with age throughout adolescence (Dubé, et al., 2009; Eaton, et al., 2012; Valente, et al., 2007). Peer association has also been shown to vary with age, with some studies highlighting age as a moderator of the link between peer substance use or delinquency and target substance use.

3.2.1.1. Cross-sectional evidence

Cross-sectional studies on the moderating effect of age on peer association were inconsistent. For example, in one study examining the link between peer and target substance use in adolescents aged 11 to 18 years, Ferguson and colleagues (2011) found that the correlation between peer delinquency and targets’ substance use was strongest when the targets started using substances between the ages of 13 and 16 years (middle adolescence). Kelly and colleagues (2012) found lower alcohol use in adolescents who had both one peer who tried alcohol and were in 8th grade as opposed to adolescents who had one peer who had tried alcohol and were in 6th grade. On the other hand, Mennis & Mason (2012) found higher substance use in a group of 13 to 20 years olds who had both lower social network quality (perceived friends substance use, if friends had tried to influence their substance use, and positive activities with these friends), and were older. Finally, some cross-sectional studies found no significant interactions with age (Burk, Van Der Vorst, Kerr, & Stattin, 2012; Denault & Poulin, 2012).

3.2.1.2. Longitudinal evidence

In a longitudinal study following five cohorts (11 to 15 years old) over a 4-year period, Duncan and colleagues (1994) found that the link between peer substance use and targets’ level of alcohol use was greatest when targets were aged between 12 and 13 years compared to when they were aged between 14 and 15 years. However, some studies have shown that peer association was particularly important during target’s middle adolescence (2012; Fergusson et al., 2002). Moreover, Fergusson and colleagues (2002) found that peer association seemed to decline with age in a longitudinal sample of targets followed from 14 to 21 years. In that study the strength of peer association was greatest between 14 and 15 years old and weakest between 20 and 21 years old. In short, early- and mid-adolescence seem to be the developmental period when targets are most vulnerable to peer association.

3.2.1.3. Experimental evidence

A number of experimental studies have demonstrated that the influence of peers on target risk-taking behaviors varies by age (Chein, Albert, O’Brien, Uckert, & Steinberg, 2011; Mrug, Hoza, & Bukowski, 2004). In the absence of experimental evidence directly examining adolescent substance use, some studies investigated adolescent risky behaviors using risky-driving paradigms because both behaviors involve reward seeking and have been linked with increased activation in reward-centers of the brain (e.g., ventral striatum; Chase, Eickhoff, Laird, & Hogarth, 2011; Leyton et al., 2002; Chein, Albert, O’Brien, Uckert, & Steinberg, 2011). For example, Chein and colleagues (2011) found that, compared to young adults, adolescents took more risks when observed by peers, and demonstrated greater activation in reward-related brain regions (i.e., ventral striatum and orbitofrontal cortex) while making risky decisions when observed by peers. The possible use of such ethical proxies for the study of adolescent substance use will be discussed further in the recommendation section.

3.2.1.4. Summary and implications

Longitudinal and cross-sectional studies seem to be consistent in indicating that early and middle adolescence are periods when targets are most vulnerable to peer association, and that this vulnerability is attenuated in late adolescence. Although age cannot be strictly considered as a predisposing vulnerability, results support both the diathesis stress model (with the association between peer and target deviance/substance use being the greatest in early adolescence) and the resilience model (with the association between peer and target deviance/substance use being the weakest in later adolescence), illustrating the complementary nature of these models. Steinberg and Monahan (2007) speculated that the decreasing strength of peer association could be explained, at least in part, by the development of resistance to peer influence, which is concurrent with the development of a sense of identity, completed typically by late adolescence.

Furthermore, targets’ age did not seem to act as a moderator independent of other important factors which should be further studied. For example, Li, Barrera, Hops and Fisher (2002) found that in adolescents with initial low levels of alcohol use at 14 years, the presence of deviant peers was concurrently and prospectively linked with increasing alcohol use across adolescence, whereas in adolescents with a high initial level of alcohol use at 14 years the presence of deviant peers was not linked with alcohol use across adolescence. This could indicate that adolescents have periods in which they can be more easily influenced by their peers but that the sensitivity of these developmental windows could depend on other factors (e.g., substance use history or social context). Along the same lines, the hypothesis proposed by Steinberg and Monahan (2007) that the moderating effect of age could be explained by lower resistance to peer association in early adolescence could be tested using a mediated moderation analysis (see first recommendation in section 5).

3.2.2. Gender

Most studies examining moderators of peer association either control for gender, or examine its effect on substance use behaviors directly. However, the results from adolescent studies seem to be some of the most inconsistent in the field, even when examining main effects. For instance, although the direct effect of gender has been demonstrated many times in adults, with males showing greater substance use and a greater prevalence of substance use disorders (e.g., Hall, Teesson, Lynskey, & Degenhardt, 1999), many studies of adolescents failed to find significant effects when looking at the direct role of gender on adolescent substance use (Costello, Sung, Worthman, & Angold, 2007; Cumsille, et al., 2000; Donovan, Jessor, & Costa, 1999; Schulte, Ramo, & Brown, 2009; Urberg, Degirmencioglu, & Pilgrim, 1997). Nonetheless, other variables could come into play and interact with gender during adolescence.

3.2.2.1. Cross-sectional evidence

Most cross-sectional studies examining gender as a possible moderator of concurrent peer association on substance use do not find significant effects (Bergh, Hagquist, & Starrin, 2011; Bobakova, et al., 2012; Burk, Van Der Vorst, Kerr, & Stattin, 2012; Denault & Poulin, 2012; Mennis, & Manson, 2012). Only two studies suggested that peer association may be greater in male as opposed to female adolescents who associate with delinquent and substance-using peers, as reported by teachers (Mrug & Windle, 2009) or the targets (Clark, Belgrave & Abell, 2012), and one study suggested that peer association may be greater in female adolescents associating with peers that use alcohol (Anderson, et al., 2011). In this last study though, a significant three-way interaction between gender, anxiety and peer association was found: highly anxious boys who had alcohol using friends reported the highest binge drinking rates in the last month. Finally, the only study that assessed cross-gender (male-female) peer association through peer-reported drunkenness frequency, suggested that there was a stronger link between male friends and female target’s substance use, than that of female friends and male targets’ substance use (Gaughan, 2006). It might therefore be useful to also consider peer gender, which may further help reconcile these apparently inconsistent results of cross-sectional studies.

3.2.2.2. Longitudinal evidence

Here also, many studies find no moderating effect of gender on peer association using either target-reported peer antisocial behavior (Guo, Hill, Hawkins, Catalano, & Abbott, 2002), peer-reported substance use (Larsen, Overbeek, Vermulst, Granic, & Engels, 2010) or target reported substance use ( Rabaglietti, Burk, & Giletta, 2012; Westling, Andrews, Hampson, & Peterson, 2008). However, some longitudinal studies suggest that peer-association is greater in male adolescent targets who associate with delinquent and substance-using peers (based on peer-report data) than their female counterparts (Crosnoe, Erickson, & Dornbusch, 2002). Further, and in contrast with the previous studies that examined two-way interactions, Marshal and Chassin (2000) observed in a three-way interaction between gender, parental discipline (i.e., consistency of parental discipline towards their child’s misbehavior), and substance-using-peers, that parental discipline was linked with lower influence of peer association on future substance use for girls but higher influence for boys. The authors suggest that these findings could be the result of boys interpreting parental discipline as a form of control that goes against their desire for independence, and that this interpretation increases their susceptibility to the effects of peer association. However, this proposition has to be further tested empirically.

3.2.2.3. Experimental evidence

No experimental studies were found.

3.2.2.4. Summary and implications

Cross-sectional and longitudinal studies on the moderating role of gender on the link between peer deviance and target substance use also reflect the inconsistencies noted in studies of the direct effects of gender on substance use. Thus, there is mixed evidence that gender is an important moderator of the effect of peers on adolescent substance use, with only one longitudinal study showing a significant interaction between peer substance use and gender in the prediction of alcohol and tobacco use frequency. Perhaps, as suggested by Brechwald and Prinstein (2011), the effect of gender could be better studied in the context of three-way interactions that would include gender along with other moderators, as was the case in the studies by Anderson and colleagues (2011) and Marshal and Chassin (2000).

3.2.3. Pubertal status

Longitudinal research seems to indicate that early puberty and physical maturation are risk factors for both girls’ (Lanza & Collins, 2002) and boys’ (Castellanos-Ryan, Parent, Vitaro, Tremblay, & Séguin, in press; Dick, Rose, Pulkkinen, & Kaprio, 2001) future substance use over and above chronological age. Specifically, girls with early pubertal maturation (e.g. menarche before the age of 12.5 years) have been shown to be at higher risk for future substance use (Ge, et al., 2006). Similarly, Costello, Sung, Worthman & Angold (2007) found that, for boys aged 12 years and older, and for girls in general, physical maturity and early puberty were linked with higher alcohol use. In another study, girls that had their first menarche at an early age (11 years or younger) were more likely to use alcohol and cigarettes earlier than those who started their menstruations after 11 years of age (Dick, Rose, Viken, & Kaprio, 2000). In contrast, in the same study, girls who started their menstruations late (after they turned 14) seemed to be “protected” from early alcohol use. Despite its apparent importance with regards to substance use behaviors, little research has been done on puberty as a moderator of peer association.

3.2.3.1. Cross-sectional evidence

A study by Fergusson and colleagues (2007) showed that delinquency, including substance use, at age 13 years was greatest in target boys and girls who matured early and affiliated with deviant friends. This same study also showed that the link between deviant peers and targets’ delinquency was weakest in those reporting late puberty. Finally, Stattin, Kerr, & Skoog, (2011) found higher delinquency scores (i.e., including cannabis use) in a group of girls that spent more time with peers and were early maturers.

3.2.3.2. Longitudinal evidence

Longitudinal studies seem to suggest that adolescents experiencing early puberty are more likely to affiliate with deviant or substance-using-friends. Moreover, in one study, the link between peer substance use at age 11 years and targets’ intention and willingness to use substances two years later was stronger for those reporting early puberty at age 11 years (i.e., more advanced pubertal stage relative to same age-peers; Ge, et al., 2006). Another longitudinal study has also shown an interaction between pubertal development and affiliation with deviant friends (Costello, et al., 2007). Using a sample of young adolescent girls and boys, they found that the link between deviant peer affiliation in early adolescence and targets’ own alcohol use by the age of 16 years was greater for those having reached Tanner stage IV by age 12.

3.2.3.3. Experimental evidence

No experimental studies were found.

3.2.3.4. Summary and implications

Longitudinal studies reviewed in this section provide support for the diathesis-stress model by showing that the effect of peer association on adolescent substance use was greater in girls and boys who mature early, independently from chronological age, with the age effect still reaching significance in the Ge, et al., (2006) study. Support for the resilience model was also provided by Fergusson et al’s (2007) cross-sectional study, which assessed puberty on a continuum, and suggests not only that the effect of peer association is greater in early puberty, but also that the effect of peer association on adolescent delinquency, including substance use is weaker in late puberty. On a critical note, although results on pubertal status as a moderator of peer association on adolescent substance use and/or other problem behaviors seem consistent across the few studies that have examined puberty as a moderator, caution is warranted in the interpretation of these results, as other studies have shown that early pubertal development was linked with peer selection and that a mediation model may be more appropriate. For example, Costello and colleagues (2007) reported that, in addition to a greater prevalence of alcohol use, early physical maturity was linked with a higher number of deviant peers and conduct disorder for both genders. A more specific link was found in another study of adolescent boys, with high testosterone levels and advanced levels of physical maturity between ages 12 and 14 years predicting affiliation with deviant peers at age 16, which in turn predicted drug use at age 19 (Reynolds et al., 2007). Thus, these findings suggest that early puberty can increase the likelihood of affiliating with deviant peers and also may exacerbate the association between peer substance use and target substance use.

3.2.4. Genetic vulnerability

Genetic factors have also been linked to adolescent alcohol and drug use. There is compelling evidence of the heritability or familial transmission of substance use disorders (Bierut et al., 1998; Goldman, Oroszi, & Ducci, 2005; Merikangas et al., 1998; Meyers, Dick, Rose, Kendler, & Kaprio, 2010) and that this transmission is thought to occur via both genetic and environmental (or psychosocial) pathways. Twin studies have documented moderate genetic links on adult and adolescent substance use and misuse (Goldman, et al., 2005; Hettema, Corey, & Kendler, 1999; Hopfer, Crowley, & Hewitt, 2003; Kendler, Karkowski, Neale, & Prescott, 2000), with the strongest genetic links being found for alcohol use (50 – 70%; Cloninger, Bohman, & Sigvardson, 1981; Ducci & Goldman, 2008; Heath et al., 1997; Kaprio et al., 1987; McGue, Elkins, & Iacono, 2000; McGue, Slutske, & Iacono, 1999; Stacey, Clarke, & Schumann, 2009). In terms of candidate genes conveying vulnerability to substance use problems, it seems likely that over 100 genetic variants are implicated. Most prominent are those involved in alcohol metabolism (Osby, Liljenberg, Kockum, Gunnar, & Terenius, 2010; Reich et al., 1998), and in the regulation of dopamine and serotonin (Agrawal & Lynskey, 2009; Agrawal et al., 2011; Heinz, Mann, Weinberger, & Goldman, 2001; Heinz, Schafer, Higley, Krystal, & Goldman, 2003; Henderson et al., 2000; Hopfer et al., 2005; Koob & LeMoal, 1997; Snell, Glanz, Tabakoff, & Marker, 2002).

3.2.4.1. Cross-sectional evidence

In contrast to the relatively high number of studies on the univariate links between genes and substance use, there are very few studies that have examined the interaction between genes and peer association in predicting substance use. These few studies, all cross-sectional in nature, used a quantitative genetic (i.e., twin) design with peer-ratings (with the exception of Dick et al, 2007) and concluded that genetic liability was greatest in target adolescents whose peers use alcohol (Guo, Elder, Cai, & Hamilton, 2009; Harden, Hill, Turkheimer, & Emery, 2008; Kendler, Gardner, & Dick, 2011; Miranda et al., 2013). For example, in a sample of adolescent Finnish twins aged 14–17 year, Dick and colleagues (2007) found that the genetic link with alcohol use was higher (around 60%) in adolescents with many alcohol-using friends compared to those with only a few alcohol-using friends (around 20%). In most of these studies, peer association is generally considered the moderator of the gene-substance use link. However, an exception is a study by Harden, Hill, Turkheimer and Emery (2008) suggesting that adolescents with higher genetic liability to substance use may be more vulnerable to the adverse influences of their best friends’ alcohol and tobacco use, even after controlling for the tendency of these adolescents to affiliate with friends who use substances. That is, this same study showed that genetic factors, linked with an adolescent’s own substance use, were also linked with friends’ heavier substance use (referred to as a gene-environment correlation). The authors took this link into account, yet still found that these adolescents seemed more vulnerable to the adverse association with these friends, which suggests a gene-environment interaction (Harden, Hill, Turkheimer, & Emery, 2008). Interestingly, they also found that adolescents with low genetic links with substance use reported very low levels of substance use, regardless of their best friends’ substance use. These results clearly indicate that peer association on substance use can vary according to genetic vulnerability, which suggests it is an important moderator of this association.

3.2.4.2. Longitudinal evidence

No longitudinal studies were found.

3.2.4.3. Experimental evidence

No experimental studies were found.

3.2.4.4. Summary and implications

All studies reviewed were cross-sectional and most investigated whether peer substance use could moderate heritability to substance use. Together, these studies suggest that the genetic contribution to adolescent substance use was strongest at higher levels of friends’ substance use. These findings support the diathesis-stress model. However, the one study which explicitly examined the moderating effect of genetic liability on the link between peer association and adolescent substance use seemed to provide support for both the diathesis-stress and resiliency models, as it showed that the link between peer and target substance use was strongest and weakest for those at high and low genetic risk, respectively (Harden et al., 2008). This well-designed study, which controlled for the effects of peer selection (or gene-environment correlations), also illustrated nicely how the diathesis-stress and resilience models are complementary and potentially examine opposite ends of the same continuum.

3.2.5. Personality and individual characteristics of the target adolescent

Much research has found direct links between temperament or personality traits and substance use (Castellanos-Ryan, Parent, Vitaro, Tremblay, & Séguin, in press; Cooper, Agocha, & Sheldon, 2000; Sher, Bartholow, & Wood, 2000). For example, Wills and colleagues (1998) emphasized the role temperament plays in substance use by demonstrating that high “negative emotionality” (i.e., the tendency to become easily and intensely upset) and low “task orientation” (i.e., the tendency to concentrate on tasks and work on them until completion) were concurrently linked with higher levels of substance use in adolescence. In terms of personality traits, a number of disinhibited traits have been shown to predict early onset substance use. Whereas impulsivity has been consistently linked with a number of substance use outcomes (Conrod, Pihl, Stewart, & Dongier, 2000), extraversion has been linked mainly with early alcohol use (Hill, Shen, Lowers, & Locke, 2000). In addition, risk-taking and sensation seeking, in particular, have both long been linked with alcohol and substance use in adolescence and young adulthood (Castellanos-Ryan & Conrod, 2011; Comeau, Stewart, & Loba, 2001; Conrod, et al., 2000; Gerra et al., 2004; Hittner & Swickert, 2006). Studies have also found that these and other personal characteristics operate as moderators of the link between peer and target adolescents substance use.

3.2.5.1. Cross-sectional evidence

In one study, Anderson and colleagues (2011) found that the association between peer and target alcohol use was greatest when the target had a strong need for affiliation (i.e., shown in a three-way interaction, indicating that alcohol use was highest in target adolescents that had alcohol-using peers and a strong need for affiliation, but only when they were also socially anxious; Anderson, Tomlinson, Robinson, & Brown, 2011). In another study, Epstein and Botvin (2002) found the link between friends alcohol use and target’s drinking quantity and frequency to be moderated by target’s risk taking. Furthermore, both extraversion and a combination of impulsivity and sensation seeking were found to moderate the degree of peer association on drug use (Knyazev, Slobodskaya, Kharchenko, & Wilson, 2004). The link between peer association and adolescent substance use was found to be moderated by several other individual characteristics such as expectations about one’s future (e.g., academic, professional and general optimism about the future; MacNeil, Kaufman, Dressler, & LeCroy, 1999), refusal assertiveness (e.g., the ability to refuse assertively someone’s proposition; Epstein & Botvin, 2002), drug and alcohol refusal efficacy (Clark, Belgrave & Abell, 2012) and behavioral regulation (Wills, Pokhrel, Morehouse, & Fenster, 2011). Furthermore, identity commitment (including information on: future occupation, religion, politics, relationships, family, friends, dating partners, sex roles, and personal values; Dumas, Ellis & Wolfe, 2012), and adolescents’ propensity to fantasize while listening to music (e.g., imagining that they were playing the music, or used the music to dream about being in a different place; Miranda, Gaudreau, Morizot, & Fallu, 2012) were two other factors which moderated the link between peer association and adolescent substance use.

3.2.5.2. Longitudinal evidence

Some longitudinal designs have also been used to examine under what conditions peer association varies. For example, Henry, Slater & Oetting (2005) found in a longitudinal sample of middle school US students, that having an increasing trajectory for risk-taking behaviors (i.e., willingness to engage in risky activities without concern about the consequences) appeared to be linked with a higher target’s sensitivity to peers’ alcohol use than having a stable or decreasing trajectory. In another study Rabaglietti, Burk and Giletta (2012) found lower levels of alcohol intoxication in targets with alcohol using friends with higher regulatory self-efficacy as opposed to targets with alcohol using friends with low regulatory self-efficacy. Further, Allen and colleagues (2012) found that many personal characteristics (i.e., low autonomy, low skills in handling deviancy and high susceptibility to peer influence) were all linked with higher alcohol and marijuana use in adolescents with alcohol and marijuana using peers. The popularity or social status of targets also seemed to play a role in how susceptible they may be to peers. For example, in their study Allen, Porter, McFarland, Marsh and McElhaney (2005) found stronger peer-association in popular as opposed to less popular targets. However, little research has been done on the concordance between targets’ and peers’ self-reported characteristics and targets’ future substance use. One study that has examined this association found that substance use in mid-adolescence was at its highest when both targets’ disruptiveness (i.e., aggressive, hyperactive and oppositional behavior) and friends’ non-conformity (i.e., disliking school and having trouble with the police) were high, compared to when only one or the other was high (Fallu, et al., 2010).

3.2.5.3. Experimental evidence

Only one experimental study was conducted on temperament or personality factors as moderators of peer association and substance use and other problem behaviors. Cohen and Prinstein (2006) asked targets to answer questions about aggressiveness and health risk behaviors via an online chat-room in the presence of three same grade peers, which were actually being impersonated by a computer program. Targets were told that the aim of the study was to examine how the group interacts in an online chat room. They could therefore see the answers of other participants. Participants were randomized to conditions where they thought they were interacting with actual same grade peers of either low or high social status (i.e., assessed via a classroom-wide peer nomination procedure). They were told that each of the four participants would have to answer the questions one at a time in a specific order and that this order would be determined randomly. However, the procedure was designed as to ensure that the target would be the last to answer all questions, allowing researchers to examine how the simulated pre-recorded answers would influence the targets answers. Findings showed that higher social anxiety moderated peer influence on health-risk behaviors, including substance use, with higher social anxiety being linked with higher conformity to peer norms independently of their social status. This effect differed in less socially anxious individuals, who showed a greater tendency to conform only to individuals of higher status (Cohen & Prinstein, 2006). The authors suggested that socially anxious individuals may be bending more rapidly to peer norms or pressure because of their need to lower or avoid an anxiety inducing situation. At the end of the study, targets were debriefed and experimenters made sure all participants understood the actual procedure and the aim of the study.

3.2.5.4. Summary and implications

In sum, many different personality and individual factors have been examined throughout the literature, with findings suggesting that most of these actually exacerbate the effect of peer association on adolescent substance use (e.g., risk-taking, sensation seeking, social anxiety), consistent with the stress-diathesis model. Both risk-taking and social anxiety have been shown to be significant moderators of peer association on adolescent substance use across different methodological designs, including longitudinal and experimental designs, making them particularly robust findings. Support for resilience models was also found, with some individual characteristics, such as high expectations about one’s future and refusal assertiveness, dampening the effect of peer association. However, one critical problem in this literature is that the individual factors reviewed as moderators are not completely independent from each other and one factor could potentially explain (i.e., mediate) the role of another factor (e.g., poor refusal assertiveness could explain the potential exacerbating effect of high popularity). This does not discount these factors as important moderators, but highlights the need to simultaneously include other individual factors as potential explanatory variables of moderated effects (i.e., mediated moderation) in future studies. In addition, but with the exception of the studies by Cohen and Prinstein (2006) and Fallu et al. (2010), most studies have not examined peers and targets’ characteristics simultaneously and interactively. Developing such designs may be important to clarify the complex links between peer and target personality characteristics.

Other personality and individual characteristics which should be further studied include self-esteem and resistance to peer influence. Although yet to be tested empirically, low self-esteem could be hypothesized as an important moderator of the link between peer association and adolescent substance use, as it has been shown to exacerbate an adolescent’s general susceptibility to peer pressure (Zimmerman, Copeland, Shope, & Dielman, 1997) and to exacerbate the effect of peer association on other externalizing problems like aggression (Bukowski, Velasquez, & Brendgen, 2008). Assessing adolescents’ propensity to resist peer pressure may be particularly important when examining the effects of peers on substance use in adolescence, as research suggests that “resistance to peer influence” is at its lowest in early adolescence (Steinberg & Monahan, 2007). Although not often assessed in studies investigating substance use behavior, resistance to peer influence is likely to be an important moderator of the link between peer association and target substance use, and could help to determine which individuals will be more susceptible to peer substance use (Steinberg & Monahan, 2007).

3.2.6. Substance use expectancies and motives

Substance use expectancies have been found to moderate adolescents’ propensity to be influenced by their peers. The hypotheses from studies of alcohol and substance use expectancies appear to be straightforward: if adolescents expect substances to affect them positively (e.g., to make parties more fun or to help people to relax), they will be more likely to use them. Conversely, if the opposite is expected (e.g., that people may lose control and be harmed after drinking alcohol) then adolescents will be less likely to use alcohol or substances (Barnow, et al., 2004; Fisher, Miles, Austin, Camargo, & Colditz, 2007; Musher-Eizenman, Holub, & Arnett, 2003; Shen, Locke-Wellman, & Hill, 2001; Willner, 2001).

3.2.6.1. Cross-sectional evidence