Summary

Reference frames are important for understanding how sensory cues from different modalities are coordinated to guide behavior, and the parietal cortex is critical to these functions. We compare reference frames of vestibular self-motion signals in the ventral intraparietal area (VIP), parietoinsular vestibular cortex (PIVC), and dorsal medial superior temporal area (MSTd). Vestibular heading tuning in VIP is invariant to changes in both eye and head positions, indicating a body (or world)-centered reference frame. Vestibular signals in PIVC have reference frames that are intermediate between head- and body-centered. In contrast, MSTd neurons show reference frames between head- and eye-centered, but not body-centered. Eye and head position gain fields were strongest in MSTd and weakest in PIVC. Our findings reveal distinct spatial reference frames for representing vestibular signals, and pose new challenges for understanding the respective roles of these areas in potentially diverse vestibular functions.

Introduction

The vestibular system plays critical roles in multiple brain functions, including balance, posture and locomotion (Macpherson et al., 2007; St George and Fitzpatrick, 2011), spatial updating and memory (Israel et al., 1997; Klier and Angelaki, 2008; Li and Angelaki, 2005), self-motion perception (Gu et al., 2007), spatial navigation (Muir et al., 2009; Yoder and Taube, 2009) and movement planning (Bockisch and Haslwanter, 2007; Demougeot et al., 2011). More generally, vestibular information plays important roles in transforming sensory signals from our head and body into body-centered or world-centered representations of space that are important for interacting with the environment.

The parietal cortex is known to be involved in many of these functions, and vestibular responses have been found in multiple parietal areas, including the ventral intraparietal area (VIP, Bremmer et al., 2002; Chen et al., 2011a, b), the parietoinsular vestibular cortex (PIVC, Chen et al., 2010; Grusser et al., 1990a), and the dorsal medial superior temporal area (MSTd, Duffy, 1998; Gu et al., 2007; Gu et al., 2006; Page and Duffy, 2003; Takahashi et al., 2007). Vestibular signals in these areas are integrated with other sensory and movement-related signals to form multimodal representations of space (Andersen et al., 1997). However, a challenge for constructing these multimodal representations is that different sensory and motor signals are originally encoded in distinct spatial reference frames (Cohen and Andersen, 2002). For example, vestibular afferents signal motion of the head in space (a head-centered reference frame), whereas visual motion signals are represented relative to the retina (an eye-centered frame, Fetsch et al., 2007; Lee et al., 2011). Facial tactile signals are head-centered (Avillac et al., 2005), whereas arm-related premotor neurons use a more complicated relative position code (Chang and Snyder, 2010). It has been commonly thought that multisensory neurons should represent different cues in a common reference frame (Cohen and Andersen, 2002), but this hypothesis has been challenged by experimental findings (Avillac et al., 2005; Fetsch et al., 2007; Mullette-Gillman et al., 2005).

Although the spatial references frames used by different regions of parietal cortex are not fully known, the literature suggests some possible differences between areas. Parietal cortex has been implicated in mediating the ‘body schema’, a spatial representation of the body in its environment (Berlucchi and Aglioti, 1997; Berlucchi and Aglioti, 2010; Schicke and Roder, 2006). It has been proposed that area VIP serves as a multisensory relay for remapping modality-specific spatial coordinates into external coordinates (Azanon et al., 2010; Klemen and Chambers, 2012; McCollum et al., 2012). Indeed, TMS over human VIP interferes with the realignment of tactile and visual maps (Bolognini and Maravita, 2007), as well as tactile and auditory maps (Renzi et al., 2013) across hand postures. Although these studies may suggest a world-centered representation in human VIP, they were not designed to distinguish head-, body-and world-centered coordinates. Thus, the findings might also be explained by head- or body-centered representations.

Spatial hemi-neglect, a common type of parietal cortex dysfunction, involves diminished awareness of regions of contralesional space. Interestingly, reference frame experiments with neglect patients support the existence of multiple spatial representations in parietal cortex that use different reference frames (Arguin and Bub, 1993; Driver et al., 1994; Karnath et al., 1993; Vallar, 1998). These properties were predicted from simulated lesions in a basis-function model of parietal cortex (Pouget and Sejnowski, 1997). Remarkably, vestibular and optokinetic stimulation protocols that produce nystagmus with a slow phase towards the left side temporarily ameliorate aspects of the hemi-neglect syndrome, which may implicate an egocentric representation of space based on vestibular signals (Moon et al., 2006). Thus, some researchers have suggested that hemi-neglect may be largely a disorder of the vestibular system (Karnath and Dieterich, 2006).

By these considerations, it is critical to better understand the spatial reference frames of vestibular signals in parietal neurons. Are vestibular responses in parietal cortex represented in the same, head-centered format as in the vestibular periphery? Or are different reference frames found in different areas, perhaps to facilitate integration with other inputs? Based on human studies (Azanon et al., 2010; Bolognini and Maravita, 2007; Renzi et al., 2013), we hypothesized that VIP might represent space in body- or world-centered coordinates. This would be in stark contrast to MSTd, where vestibular tuning is mainly head-centered with a small shift toward an eye-centered representation (Fetsch et al., 2007). Based on spatiotemporal response properties, we previously proposed that VIP receives vestibular information through projections from PIVC (Chen et al., 2011a). Thus, we further hypothesize that PIVC may reflect a partial transformation from head-centered to body-centered coordinates. A key feature of our approach is to dissociate body-, eye- and head-centered reference frames by varying eye position relative to the head and head position relative to the body. Very few studies have previously attempted to separate head-and body-centered reference frames in parietal cortex (Brotchie et al., 1995; Snyder et al., 1998), and none in the context of self-motion.

We find that the spatial reference frames of vestibular signals differ markedly across areas: VIP tuning curves remain invariant in a body-centered reference frame, whereas PIVC tuning curves show an intermediate head/body-centered representation. Both of these areas differ strikingly from area MSTd, where vestibular heading tuning curves show a broad distribution spanning head- and eye-centered (but not body-centered) representations. These findings have broad implications for the functional roles of vestibular signals in parietal cortex and clearly distinguish VIP and MSTd in terms of their spatial representations of self-motion.

Results

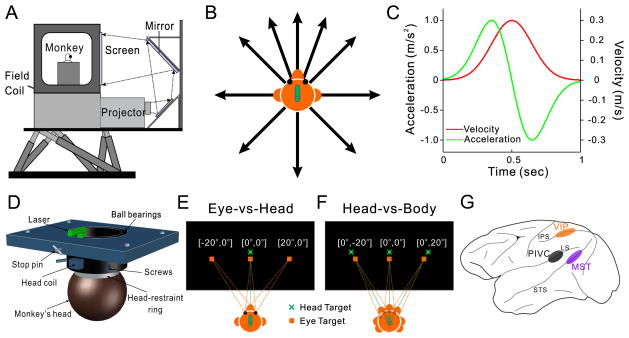

Using a motion platform (Fig. 1A) to deliver smooth translational movements (Fig. 1C) in the horizontal plane (Fig. 1B), we examined the spatial reference frames of vestibular heading tuning in areas PIVC, VIP and MSTd (Fig. 1G). In one set of stimulus conditions, the head remained fixed relative to the body and eye position varied relative to the head (Eye-vs-Head condition, Fig. 1E). In the other set of conditions, eye and head positions varied together, such that eye position relative to the head remained constant while head position relative to the body changed (Head-vs-Body condition, Fig. 1F). Our goal was to examine whether vestibular heading tuning curves of individual neurons were best represented in eye-centered, head-centered, or body-centered coordinates. Basic vestibular response properties of these neurons are described elsewhere (Chen et al., 2010, 2011a, b, c; Gu et al., 2007; Gu et al., 2006; Takahashi et al., 2007).

Figure 1. Experimental apparatus and design.

A. In the virtual reality apparatus, the monkey, field coil, projector, mirrors, and screen were mounted on a motion platform that could translate in any direction. B. Illustration of the 10 heading directions that were tested in the horizontal plane. C. The Gaussian velocity profile of each movement trajectory (red) and its corresponding acceleration profile (green). D. Schematic illustration of the head restraint that allows yaw-axis rotation of the head. The head-restraint ring (white) is part of the cranial implant, and attaches to the collar (black) via set screws. The collar is attached to a plate at the top of the chair (blue), with ball bearings that allow it to rotate. A stop pin can be engaged to prevent rotation of the collar and fix head orientation. A head coil is attached to the collar to track head position, and a laser mounted on top of the collar provides visual feedback regarding head position. E. Eye-vs-Head condition. The head target (green) was located straight ahead while the eye target (orange) was presented at one of three locations: left (−20°), straight ahead (0°), or right (20°). F. Head-vs-Body condition. Both the eye and head targets varied position together, left (−20°), straight ahead (0°), or right (20°), such that the eyes were always centered in the orbits. See Supplementary Figure S2 for confirmation that the trunk did not rotate with the head. G. Schematic illustration of the locations of the three cortical areas studied (PIVC, VIP and MST). See also Supplementary Figure S1.

Quantification of Reference Frames by Displacement Index (DI)

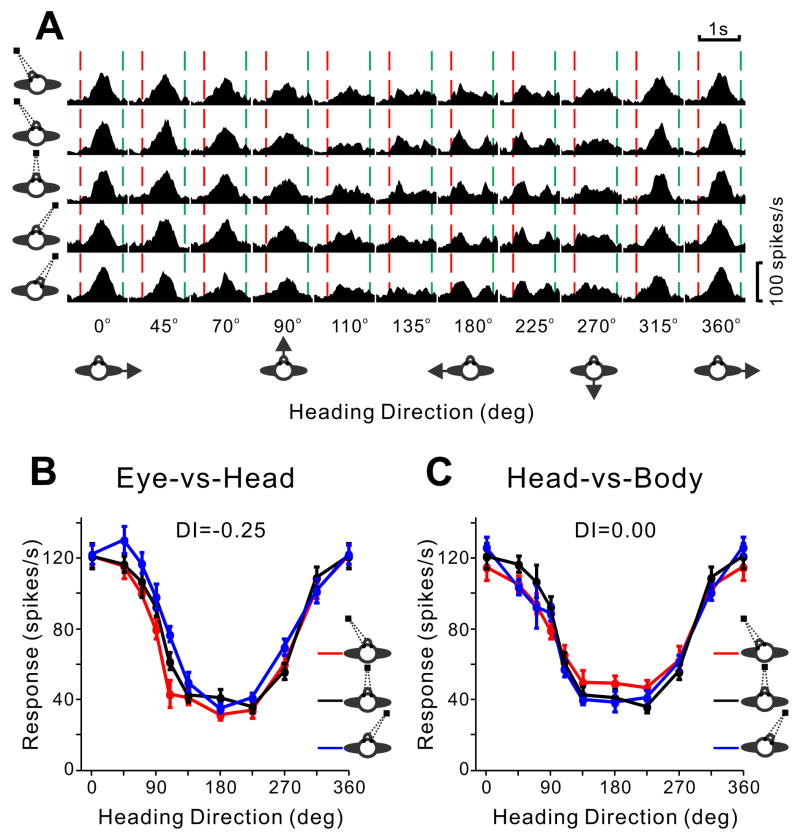

To quantify neural responses, peristimulus time histograms (PSTHs) were constructed for each direction of motion and each combination of eye and head positions (Fig. 2A). Heading tuning curves were then constructed from mean firing rates computed in a 400ms time window centered on the “peak time” for each cell (see Experimental Procedures and Chen et al., 2010), as illustrated for an example VIP neuron in Fig. 2B, C. For the Eye-vs-Head condition (Fig. 2B), if the three tuning curves were systematically displaced from one another by an amount equal to the change in eye position (−20°, 0°, 20°), this would indicate an eye-centered reference frame. If the three tuning curves overlapped, this would indicate a head- or body-centered frame. For the Head-vs-Body condition (Fig. 2C), if the three tuning curves were systematically displaced by amounts equal to the change in head position (−20°, 0°, 20°), this would indicate an eye- or head-centered frame. If the three tuning curves overlapped, this would indicate a body-centered frame. Qualitatively, the three curves for the example VIP neuron overlap nicely in both conditions (Fig. 2B,C), suggesting a body-centered reference frame.

Figure 2. Data from an example VIP neuron.

A. PSTHs of the neuron’s responses are shown for all combinations of 10 headings (from left to right) and five combinations of [eye, head] positions: [0°, −20°], [−20°, 0°], [0°, 0°], [20°, 0°], [0°, 20°] (top to bottom). Red and green dashed lines represent stimulus onset and offset. B. Tuning curves from the Eye-vs-Head condition, showing mean firing rate (± SEM) as a function of heading for the three combinations of [eye, head] position ([−20°, 0°], [0°, 0°], [20°, 0°]), as indicated by the red, black and blue curves, respectively. C. Tuning curves from the Head-vs-body condition for three combinations of [eye, head] position ([0°, −20°], [0°, 0°], [0°, 20°]).

A displacement index (DI) was computed to quantify the shift of each pair of tuning curves relative to the change in eye or head position (Avillac et al., 2005; Fetsch et al., 2007). This method finds the shift that maximizes the cross-covariance between the two curves (see Methods), and takes into account the entire tuning function rather than just one parameter such as the peak. DI is robust to changes in the gain or width of the tuning curves and can tolerate a wide variety of tuning shapes. For the example VIP cell in Fig. 2, the mean DIs for both the Eye-vs-Head and Head-vs-Body conditions were close to zero (0.25 and 0.00, respectively), consistent with a body-centered representation of heading.

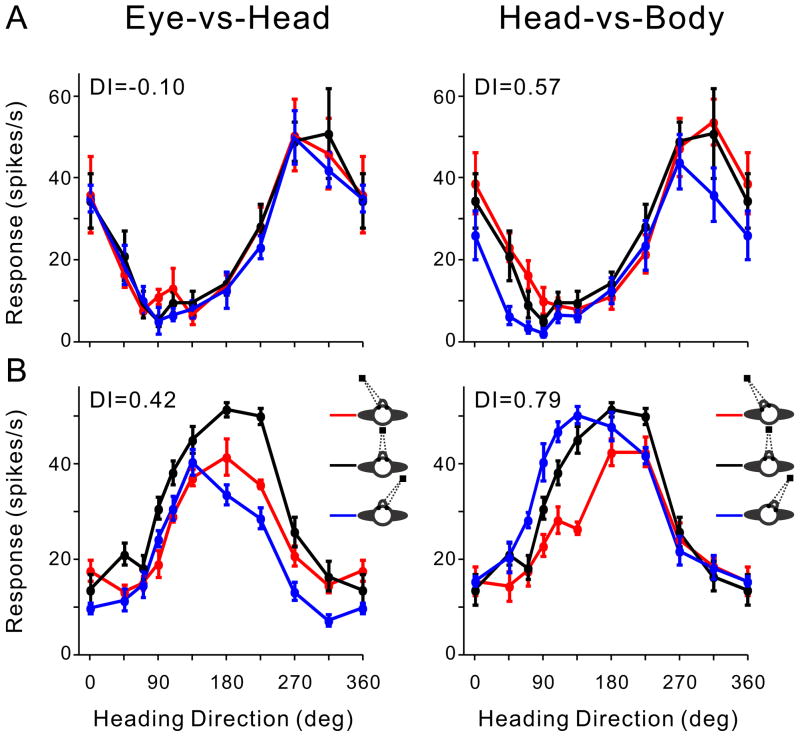

Tuning curves of typical example neurons from PIVC and MSTd are shown in Fig. 3A, B. For the example PIVC cell (Fig. 3A), DI values were 0.10 for the Eye-vs-Head condition and 0.57 for the Head-vs-Body condition, respectively, indicating a representation that is intermediate between a head-centered and a body-centered reference frame. In contrast, for the example MSTd cell (Fig. 3B), DI values (Eye-vs-Head DI = 0.42 and Head-vs-Body DI = 0.79) indicate a representation that is intermediate between eye-centered and head-centered.

Figure 3. Data from two additional example neurons.

A. A PIVC neuron showing a reference frame intermediate between head- and body-centered. B. An MSTd neuron showing a reference frame intermediate between eye- and head-centered. Format as in Figure 2.

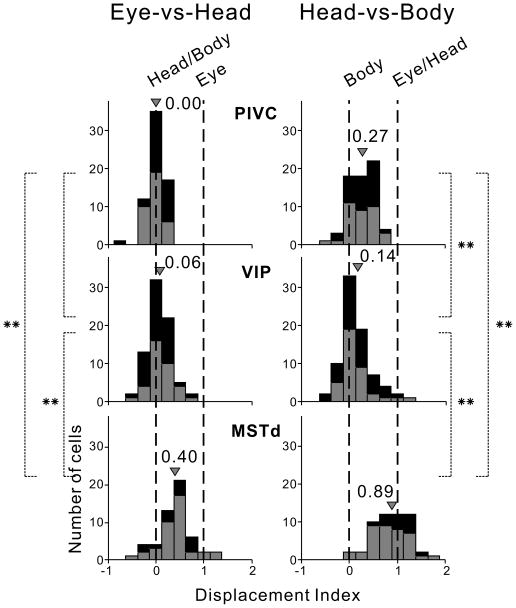

Distributions of DI values for the three cortical areas are summarized in Fig. 4. For PIVC (top row), DI values clustered around 0 in the Eye-vs-Head condition, with a mean DI of 0.00±0.05 SE which was not significantly different from 0 (p=0.13, sign test). In contrast, DI values for PIVC clustered between 0 and 1 in the Head-vs-Body condition, with a mean of 0.27±0.06, a value that was significantly greater than 0 (p<0.0001, sign test) and significantly less than 1 (p<0.0001). Thus, PIVC neurons generally coded vestibular heading in a reference frame that was intermediate between body- and head-centered.

Figure 4. Summary of Displacement Index (DI) results.

Black and gray bars illustrate data from the two animals. In the Eye-vs-Head condition (left column), DI values of 0 and 1 indicate head/body-centered and eye-centered representations, respectively. In the Head-vs-Body condition (right column), DI values of 0 and 1 indicate body-centered and eye/head-centered reference frames, respectively. Arrowheads indicate mean DI values for each distribution, and ** indicates significance at p<0.001. For the Eye-vs-Head condition, data are shown for 65 PIVC cells, 76 VIP neurons, and 53 MSTd cells. For the Head-vs-Body, data are shown for 66 PIVC, 78 VIP, and 54 MSTd neurons.

For VIP (Fig. 4, middle row), the mean DI values were 0.06±0.05 for the Eye-vs-Head condition (not significantly different from 0, p=0.08, sign test) and 0.14±0.07 for the Head-vs-Body condition (marginally different from 0, p=0.02, but significantly different from 1, p<0.001). Thus, the vestibular representation of heading in VIP was nearly body-centered. Finally, for MSTd (bottom row), the average DI value for the Eye-vs-Head condition was 0.40±0.09, which was significantly different from both 0 and 1 (p<0.001). In contrast, the average DI for the Head-vs-Body condition was 0.89±0.11, and was not significantly different from 1 (p=0.50). MSTd neurons, therefore, generally represent vestibular information in a reference frame that is intermediate between eye- and head-centered.

Average DIs for the Eye-vs-Head condition did not differ significantly between PIVC and VIP (p=0.24, Wilcoxon rank sum test), whereas average DIs differed significantly between these areas in the Head-vs-Body condition (p= 0.001). This indicates that VIP is more body-centered than PIVC. Average DI values for MSTd differed significantly from both PIVC and VIP, and this was true for both the Eye-vs-Head and Head-vs-Body conditions (p≪0.001). The variance of the DI distributions was also significantly greater for MSTd than VIP and PIVC (Levene’s test, p<0.001), indicating a greater spread of reference frames across neurons in MSTd.

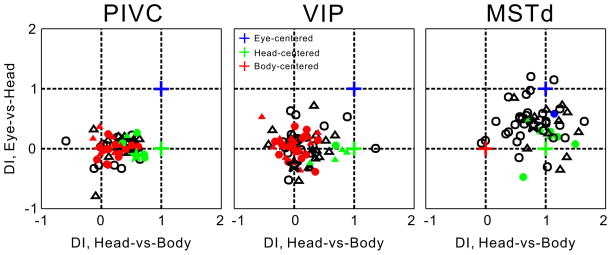

To better visualize the distribution of reference frames in each area, DI values from the Eye-vs-Head condition were plotted against DIs from the Head-vs-Body condition (Fig. 5). In this representation, body-, head- and eye-centered reference frames are indicated by coordinates (0, 0), (1, 0) and (1, 1), respectively (red, green and blue crosses). A bootstrap method (see Experimental Procedures) was used to classify neurons as eye-, head- or body-centered (colored symbols in Fig. 5). PIVC neurons tend to cluster between body- and head-centered representations, with 33.3% of cells classified as body-centered (red), 9.1% classified as head-centered (green), and none classified as eye-centered. VIP neurons cluster around a body-centered representation, with 39.7% of cells classified as body-centered, 6.4% classified as head-centered, and none classified as eye-centered. Finally, MSTd neurons are broadly distributed between eye- and head-centered representations, with 13% of cells classified as head-centered, one cell (2%) classified as eye-centered (blue datum), and no neurons classified as body-centered. Together these DI analyses reveal that tuning shifts in areas VIP, PIVC, and MSTd are consistent with different spatial reference frames for vestibular heading tuning.

Figure 5. Reference frame classification by DI analysis.

DI valuea for the Head-vs-Body condition are plotted against those for the Eye-vs-Head condition. Eye-centered (blue cross), head-centered (green cross), and body-centered (red cross) reference frames are indicated by the coordinates (1, 1), (1, 0) and (0, 0), respectively. Circles and triangles denote data from monkey E and monkey Q, respectively. Colors indicate cells classified as eye-centered (blue), head-centered (green), or body-centered (red), whereas open symbols denote unclassified neurons. Data are shown for 65 PIVC, 76 VIP, and 53 MSTd neurons. Stars represent the three example neurons from Figures 2 and 3.

Individual curve fits

The DI analysis provides a model-independent characterization of tuning shifts. However, it does not characterize changes in response amplitude as a function of eye/head position, known as ‘gain fields’ (Bremmer et al., 1997; Cohen and Andersen, 2002). To better characterize the effects of eye and head position on heading tuning, we fit a von Mises function (Eq. 2) separately to each tuning curve that passed our criteria for significant tuning.

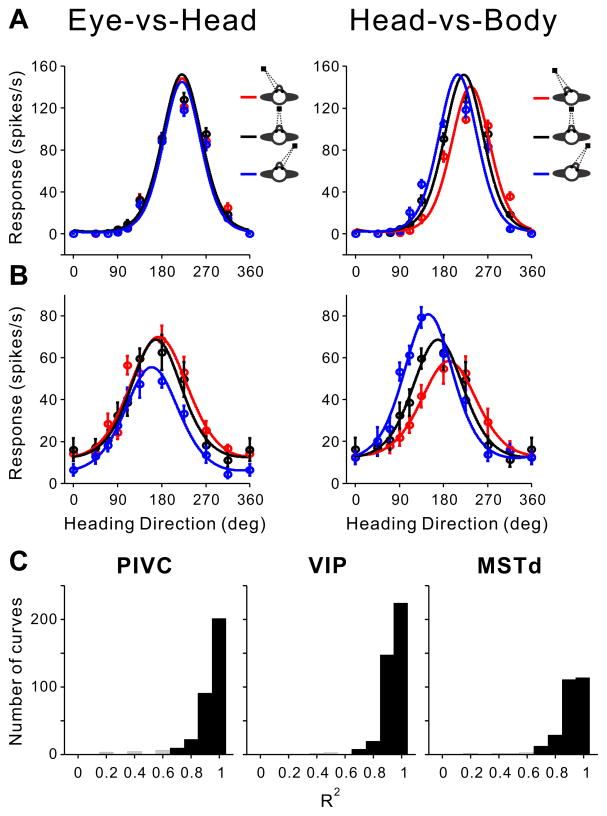

Tuning curves in all 3 areas were satisfactorily fit by von Mises functions, as illustrated by the example cells in Fig. 6A,B. The goodness of fit, as quantified by R2 values, is illustrated for each area in Fig. 6C. Median values of R2 are 0.96, 0.95, and 0.94 for PIVC, VIP, and MSTd, respectively. To eliminate bad fits from our analysis, we excluded a small minority of fits (2.4% in PIVC, 0.8% in VIP and 1.1% in MSTd) with R2 < 0.6 (Fig. 6C, open bars). The von Mises function has 4 free parameters: preferred direction (θp), tuning width (σ), peak amplitude (A) and baseline response (rb). We did not observe significant changes in tuning width (σ) or baseline response (rb) across the population: none of the four comparisons (σR20 − σ0), (σL20 − σ0), (rbR20 − σ0) and (rbL20 − σ0) revealed significant differences (t-tests, PIVC: p=0.06, 0.80, 0.17 and 0.75; VIP: p=0.29, 0.89, 0.05 and 0.99; MSTd: p=0.33, 0.12, 0.81 and 0.08). Thus, we focused on testing how parameters θp and A were modulated by changes in eye and head position.

Figure 6. Von Mises fits to heading tuning curves.

A, B. Data are shown for example neurons from PIVC (A) and MSTd (B). For each cell, heading tuning curves with error bars (mean firing rate ± SEM) are shown for the Eye-vs-Head (left) and Head-vs-Body (right) conditions. Smooth curves show the best-fitting von Mises functions. C. Distributions of R2 values, which measure goodness of fit, for PIVC, VIP, and MSTd. Filled and gray bars represent tuning curves with significant (p<0.05) and insignificant fits (p>0.05), respectively. Data are shown only for tuning curves with significant heading tuning (PIVC: 317 curves from 66 neurons; VIP: 378 curves from 78 neurons; MSTd: 249 curves from 54 neurons).

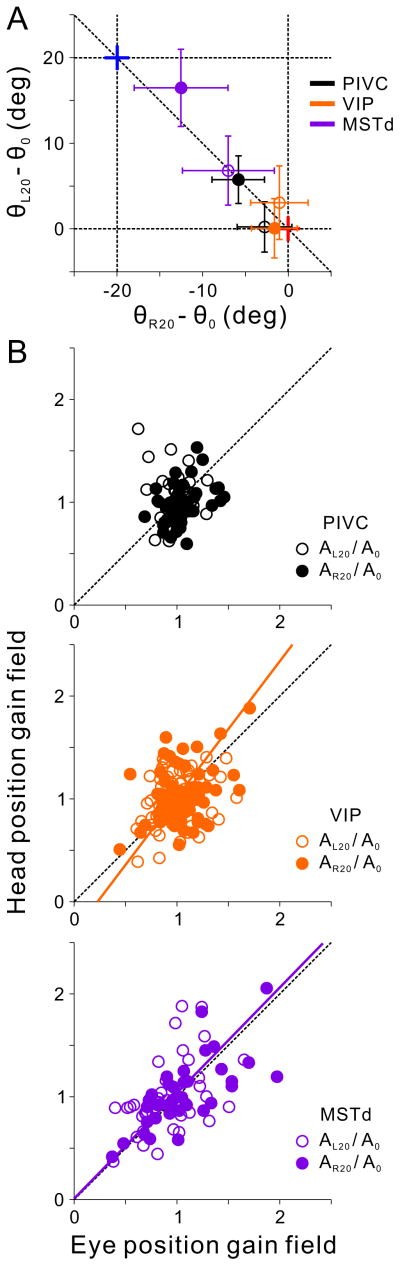

Fig. 7A shows the average difference in preferred direction between left (−20°) and forward (0°) eye/head positions (θL20 − θ0) against the corresponding difference in preferred direction between right (20°) and forward (0°) eye/head positions (θR20 − θ0). For PIVC, preferred direction shifted significantly with different head positions (Fig. 7A, filled black symbol; 95% CI does not include [0,0]), but did not shift significantly with different eye positions (open black symbol; 95% CI includes zero on both axes). For VIP, direction preferences did not shift significantly with either eye or head positions (Fig. 7A, orange filled and open symbols; CIs include [0,0]). Finally, for MSTd, direction preferences were shifted significantly along both axes with changes in both eye and head position (Fig. 7A, purple symbols). Thus, consistent with the DI analysis, VIP neurons were most consistent with a body-centered reference frame, PIVC neurons were intermediate between head-centered and body-centered, and MSTd neurons were intermediate between eye- and head-centered.

Figure 7. Population summary of tuning shifts and gain fields.

A. The shift in heading preference between left (−20°) and center (0°) eye/head positions (θL20 − θ0) is plotted against the shift in preference between right (20°) and center (0°) eye/head positions (θR20 − θ0). Data (means±95% CI) are shown separately for PIVC (black), VIP (orange) and MSTd (purple). Open and filled symbols represent data from the Eye-vs-Head and Head-vs-Body conditions, respectively. For the Eye-vs-Head condition, red and blue crosses represent head/body-centered and eye-centered reference frames, respectively. For the Head-vs-Body condition, the red and blue crosses denote body-centered and eye/head-centered reference frames, respectively. See also Supplementary Figure S3. B. Head position gain fields are plotted against eye position gain fields. Open and filled symbols show gain ratios ( ) and ( ), respectively. Data are shown for PIVC (top, black), VIP (middle, orange), and MSTd (bottom, purple). The orange and purple solid lines show type II regression fits. Data from the two animals have been combined (Eye-vs-Head condition, PIVC: n=58, VIP: n=74, MSTd: n=43; Head-vs-Body condition, PIVC: n=57, VIP: n=72, MSTd: n=47).

An important feature of many extrastriate and posterior parietal cortex neurons is a modulation of the amplitude of neuronal responses as a function of eye position, known as a “gain field” (Cohen and Andersen, 2002). Multiple studies have documented gain fields for eye position in parietal cortex (Cohen and Andersen, 2002) and a few studies have also shown gain fields for hand position (Chang et al., 2009) or head position (Brotchie et al., 1995). Are heading tuning curves in PIVC, VIP and MSTd scaled by eye or head position?

Using the von Mises function fits, we computed the ratio of response amplitudes for left and center eye/head positions (AL20/A0), as well as the ratio of amplitudes for right and center positions (AR20/A0). Fig. 7B plots these gain-field ratios for the Head-vs-Body condition against the respective ratios for the Eye-vs-Head condition. The mean values of eye position gain fields (PIVC: 1.01±0.014; VIP: 1.022±0.019; MSTd: 0.983±0.038 SEM) did not differ significantly across areas (Kruskal-Wallis non-parametric ANOVA, p = 0.26, data pooled across AL20/A0 and AR20/A0). Similarly, mean values of head position gain fields (PIVC: 0.995±0.019; VIP: 1.033±0.025; MSTd: 1.018±0.039 SEM) were not significantly different across areas (Kruskal-Wallis, p = 0.52). There were, however, significant differences between areas in the variance of the gain field distributions. The variance of the distribution of eye position gain-field ratios was significantly greater for MSTd than for both VIP (Levene’s test, p<0.001, data pooled across AL20/A0 and AR20/A0) and PIVC (p<0.001) and was greater for VIP as compared to PIVC (p<0.01). A similar trend was seen for the variance of head position gain fields, although only the difference between MSTd and PIVC was significant (p < 0.001). Thus, MSTd tended to have the strongest gain fields (greatest departures from a ratio of 1), with PIVC having the weakest gain fields and VIP having intermediate strength effects. There was no correlation between tuning curve shifts and gain ratios on a cell-by-cell basis in any area or stimulus condition (p>0.14).

Both the Eye-vs-Head and/or Head-vs-Body conditions manipulate gaze (i.e., eye-in-world) direction, by changing eye-in-head or head-in-world, respectively. Thus, if neuronal tuning curves are scaled by a gaze position signal, the gain fields for the Eye-vs-Head and Head-vs-Body conditions should be similar, and thus correlated across the population. Indeed, the slope of the relationship between head and eye position gain fields in MSTd is not significantly different from unity (type II regression; R=0.59, p<0.001, slope=1.02, 95% CI=[0.83, 1.22]; Fig. 7B, purple symbols), suggesting that MSTd vestibular tuning curves are scaled by gaze direction. In contrast, there was no significant correlation between head and eye position gain ratios in PIVC (R=0.11, p=0.25; Fig. 7B, black symbols), which may simply reflect the narrow range of gain ratios observed in PIVC. Finally, the correlation between eye and head gain ratios in VIP was significant but weaker than in MSTd (R=0.38, p<0.001, slope=1.32, 95% CI=[1.11, 1.53]; Fig. 7B, orange symbols).

Overall, these analyses indicate that gain fields, possibly driven by a gaze signal, increase in strength from PIVC to VIP to MSTd. Our main findings regarding reference frames were also confirmed by an additional analysis in which all of the data from each neuron were fit with eye-, head-, and body-centered models (Supplementary Methods and Results, Supplementary Fig. S3).

Discussion

We systematically tested the spatial reference frames of vestibular heading tuning in three cortical areas: PIVC, VIP and MSTd. Results from both empirical and model-based analyses show that vestibular signals are represented differently in these three areas: (1) Vestibular heading tuning in VIP is mainly body (or world)-centered; (2) PIVC neurons are mostly body (or world)-centered but significantly less so than in VIP; (3) MSTd neurons, in clear contrast to both VIP and PIVC, are frequently close to head-centered but significantly shifted towards an eye-centered reference frame. Because the otolith organs are fixed relative to the head, vestibular translation signals in the periphery are presumably head centered. Thus, our data show clearly that vestibular heading information is transformed in multiple ways in parietal cortex, presumably to be integrated appropriately with a diverse array of other sensory or motor signals according to largely unknown functional demands.

Gain fields

Scaling of neuronal tuning curves by a static postural signal (e.g., eye, head, or hand position) has been proposed to support neuronal computations in different reference frames (Cohen and Andersen, 2002). We find that MSTd neurons show well-correlated gain fields for eye and head position, suggesting modulation by a gaze signal (Fig. 7B). A weak correlation between eye and head gain fields was also observed in VIP, but was absent in PIVC. A similar correlation between eye and head position gain fields has been reported previously for eye-centered LIP neurons (Brotchie et al., 1995). Motivated by a feed-forward neural network model, Brotchie et al. (1995) concluded that LIP represents visual space in body-centered coordinates, not at the level of single cells, but at the level of the population activity. This conjecture could also be applicable to vestibular heading coding in MSTd. However, it is not clear why a body-centered representation might be represented in population activity in MST, rather than being made explicit in the activity of single neurons, as in VIP.

Body-centered representation of vestibular signals in VIP and PIVC

The importance of converting vestibular signals from a head-centered to a body-centered reference frame has been highlighted previously. For example, behavioral evidence shows that the brain continuously reinterprets vestibular signals to account for ongoing voluntary changes in head position relative to the body (Osler and Reynolds, 2012; St George and Fitzpatrick, 2011). In addition, subjects derive trunk motion perception from a combination of vestibular and neck proprioceptive cues (Mergner et al., 1991). Accordingly, systematic alterations in vestibulo-spinal reflex properties have been reported following altered static orientations of the head-on-body (Kennedy and Inglis, 2002; Nashner and Wolfson, 1974). Information regarding body orientation and movement is also important for perception of self-motion and localization of objects in extra-personal space (Mergner et al., 1992).

Relatively little is known about body-centered neural representations that may mediate such behaviors, however. VIP is a multimodal area with neurons responding to visual motion, as well as vestibular, auditory and somatosensory stimuli (Avillac et al., 2005; Bremmer et al., 2002; Chen et al., 2011a, c; Colby et al., 1993; Schlack et al., 2005). Tactile receptive fields are represented in a head-centered reference frame, whereas auditory and visual receptive fields are organized in a continuum between eye- and head-centered coordinates (Avillac et al., 2005; Duhamel et al., 1997; Schlack et al., 2005). Because head position relative to the body was not varied in previous studies, it is unclear whether body-centered representations may also be present in VIP for visual, auditory or somatosensory stimuli. Only vestibular and somatosensory responsiveness has been described for PIVC neurons, which do not respond selectively to optic flow or eye movements (Chen et al., 2010; Grusser et al., 1990a, b).

In our study, many neurons in VIP and PIVC had body-centered vestibular tuning. How does the brain compute heading in a body-centered reference frame from vestibular inputs that are encoded in a head-centered reference frame? Similar to the transformation from eye to head coordinates, which requires eye position information arising from efference copy or proprioception (Wang et al., 2007), the transformation of otolith signals from head- to body-centered is likely to depend on efference copy of head movement commands or neck proprioceptive signals. Such signals are likely to exist in both VIP (Klam and Graf, 2006) and PIVC (Grusser et al., 1990a, b).

Exactly how and where the body-centered reference frame transformation seen in VIP and PIVC takes place is unknown. To our knowledge, thalamic areas projecting to VIP (e.g., medial inferior pulvinar) do not respond to vestibular stimulation (Meng and Angelaki, 2010). In contrast, PIVC receives direct vestibular signals from vestibular and cerebellar nuclei via the thalamus (Akbarian et al., 1992; Asanuma et al., 1983; Marlinski and McCrea, 2008, 2009; Meng and Angelaki, 2010; Meng et al., 2007). As seen in the periphery, vestibular translation signals in the rostral vestibular nuclei maintain a head-centered representation (Shaikh et al., 2004), although reference frames intermediate between head- and body-centered, without gain fields, have been reported in the cerebellar nuclei (Kleine et al., 2004; Shaikh et al., 2004). Because PIVC projects to VIP (Lewis and Van Essen, 2000), vestibular signals in VIP could be derived from PIVC. Indeed, vestibular responses in PIVC show smaller response delays and stronger acceleration components than in MSTd or VIP (Chen et al., 2011a). The present results, showing a more complete body-centered representation in VIP, as compared to PIVC, support the notion that vestibular signals are transformed along a pathway from PIVC to VIP.

It is possible that body-centered VIP/PIVC cells receive inputs selectively from body-centered cerebellar nuclei neurons (Shaikh et al., 2004). Alternatively, head-centered vestibular signals from the brainstem and cerebellum (Shaikh et al., 2004) may be transformed into a body-centered representation during their transmission through the thalamus or within the cortical layers. While many aspects of vestibular responses in the thalamus appear to be similar to those recorded in the vestibular and cerebellar nuclei (Meng and Angelaki, 2010; Meng et al., 2007), the spatial reference frames in which thalamic vestibular signals are represented remain unclear. Whether the thalamus simply relays vestibular signals to PIVC or plays an active role in transforming these signals requires further study.

Finally, because body orientation relative to the world was not manipulated in these experiments, it is not clear whether the observed invariance of heading tuning to changes in eye and head position in VIP and PIVC reflects a body-centered representation or potentially a world-centered representation. Further studies, in which body orientation is varied relative to heading direction, will be needed to test for a world-centered reference frame. Preliminary results from such an experiment suggest that VIP responses are body-centered, not world-centered (unpublished observations).

Relationship between VIP and MSTd

The largest differences in reference frames were observed between PIVC/VIP and MSTd. MSTd neurons, which respond to both optic flow and vestibular cues, are thought to be involved in heading perception (Britten and van Wezel, 1998; Fetsch et al., 2012; Gu et al., 2008; Gu et al., 2007, 2012; Gu et al., 2006). Unlike VIP and PIVC, however, there is at present no evidence that MSTd neurons respond to somatosensory stimuli. Anatomical studies have shown that MSTd is bi-directionally connected with both VIP and the frontal eye fields (FEF) (Boussaoud et al., 1990; Lewis and Van Essen, 2000). Whereas there is clear evidence for direct vestibular projections to the FEF (Ebata et al., 2004), there is a lack of anatomical evidence for vestibular projections to MSTd through the thalamus. Quantitative analyses of the spatiotemporal response properties of PIVC, MSTd and VIP neurons to 3D heading stimuli revealed a gradual shift in response dynamics from PIVC to VIP to MSTd, as well as a gradual shift in response latency across areas, with MSTd neurons showing the largest latencies as compared to PIVC/VIP (Chen et al., 2011a). Together, the existing anatomical and neurophysiological evidence has suggested a hierarchy in cortical vestibular processing, with PIVC being most proximal to the vestibular periphery, VIP intermediate, and MSTd most distal.

How do the present results fit with this potential hierarchical scheme? Our results are consistent with the notion that vestibular signals reach VIP through PIVC. However, if MSTd received its vestibular signals through projections from VIP, the body-centered signals that are commonplace in VIP would have to be converted back to a head-centered representation in MSTd. Although this possibility cannot be excluded, it appears unlikely and would not be computationally efficient. Alternatively, vestibular signals could reach MSTd through projections from the FEF. The latter receives short-latency vestibular projections (Ebata et al., 2004) and is strongly and bi-directionally connected with both MST and VIP (Lewis and Van Essen, 2000). Indeed, neurons in the pursuit area of FEF respond to both vestibular and optic flow stimulation (Fukushima et al., 2004; Gu et al., 2010). Thus, it is possible that vestibular signals in MSTd arise from FEF, independent of the representation of vestibular heading signals in VIP, which may have its origin in PIVC. Exploration of the reference frames of vestibular responses in FEF may therefore help to elucidate these pathways.

Because the otolith organs are fixed relative to the head, otolith afferent responses are presumably organized in a head-centered reference frame. Thus, the fact that MSTd tuning curves shift partially with eye position (Fig. 5, see also Fetsch et al., 2007) might be surprising if one expects that visual signals should be transformed from an eye-centered to a head (or body)-centered reference frame in order to interact with vestibular signals, not the other way around. We consider a possible computational rationale for these findings in the next section.

Froehler and Duffy (2002) reported that responses of MSTd neurons depend on the temporal sequence of heading stimuli, indicating that MSTd neurons carry information about path as well as instantaneous heading. They also found that some MSTd neurons carry position signals that confer place selectivity on the responses. While these findings clearly indicate that MSTd represents more than just heading, it is not clear how they are related to the spatial reference frames of heading selectivity, as studied here. For example, MSTd neurons might carry path and place signals but still represent heading in an eye-centered or head-centered reference frame. The potential link between path/place selectivity and reference frames clearly deserves further study.

Reference frames and multisensory integration

A natural expectation is that multisensory integration should require different sensory signals to be represented in a common reference frame (Cohen and Andersen, 2002), as this would enable neurons to represent a particular spatial variable (e.g., heading direction) regardless of the sensory modalities of the inputs and eye/head position. In the superior colliculus, for example, visual and tactile or auditory receptive fields are largely overlapping (Groh and Sparks, 1996; Jay and Sparks, 1987), and spatial alignment of response fields might be required for multimodal response enhancement (Meredith and Stein, 1996). Without a common reference frame, the alignment of spatial tuning across sensory modalities will be altered by changes in eye and/or head position.

Many neurons in VIP and MSTd show heading tuning for both vestibular and visual stimuli (Bremmer et al., 2002; Gu et al., 2008; Gu et al., 2007; Gu et al., 2006; Page and Duffy, 2003). However, optic flow signals in MSTd are represented in an eye-centered reference frame (Fetsch et al., 2007; Lee et al., 2011). This may be surprising because one might expect heading perception to rely on head- or body-centered neural representations. Instead, vestibular signals in MSTd are shifted toward the native reference frame for visual cues (eye-centered). Despite this lack of a common spatial reference frame in MSTd, previous studies show that MSTd neurons are well suited to account for perceptual integration of visual and vestibular heading cues (Fetsch et al., 2012; Gu et al., 2008). Incongruency among reference frames has been observed in other previous studies of parietal cortex: convergence of tactile and visual receptive fields (Avillac et al., 2005), as well as visual and auditory receptive fields (Mullette-Gillman et al., 2005; Schlack et al., 2005), has been found to exhibit a diversity of reference frames in VIP.

What are the implications of the lack of a common reference frame and the prevalence of intermediate frames in parietal cortex? Some consider intermediate reference frames to represent an intermediate stage in the process of transforming signals between eye- and head-centered coordinates (Cohen and Andersen, 2002). Alternatively, theoretical and computational studies have proposed that broadly distributed and/or intermediate reference frames may arise naturally when a multimodal brain area makes recurrent connections with unimodal areas that encode space in their native reference frames (Pouget et al., 2002), and that multisensory convergence with different reference frames may be optimal in the presence of noise (Deneve et al., 2001). This theory predicts a correlation between the relative strength of multisensory signals in a particular brain area and the spatial reference frames in which they are coded (Avillac et al., 2005; Fetsch et al., 2007). Accordingly, the degree to which tuning curves shift with eye or head position in multisensory areas may simply reflect the dominant sensory modalities in that area.

Our findings are broadly consistent with this notion. In MSTd, where visual responses are generally stronger than vestibular responses (Gu et al., 2008; Gu et al., 2006), visual motion signals largely maintain their native eye-centered reference frame, whereas vestibular signals are partially shifted away from their native head-centered representation toward an eye-centered reference frame (Figs. 4, 7, and S3, see also Fetsch et al., 2007). The fact that vestibular tuning in VIP is typically stronger than visual tuning (Chen et al., 2011c) may allow the vestibular signals not to be drawn toward an eye-centered reference frame. Instead, the previously reported partial shift of VIP visual receptive fields toward a head-centered reference frame (Duhamel et al., 1997) could reflect the dominance of head-centered extra-retinal signals in this area (Avillac et al., 2005). Furthermore, the head-centered visual receptive fields reported previously in VIP (Avillac et al., 2005; Duhamel et al., 1997) might, in fact, be found to be body-centered if head position were allowed to vary relative to the body. In this case, visual and vestibular representations would be congruently represented in a common body-centered reference frame in VIP. Whether this and other predictions of the computational framework are able to withstand rigorous experimental testing remains to be determined by future studies.

Experimental Procedures

Subjects and preparation

Two male rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulata), weighing 7–10 kg, were chronically implanted, under sterile conditions, with a circular delrin cap for head stabilization as described previously (Gu et al., 2006), as well as two scleral search coils for measuring eye position. All procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and were in accordance with National Institutes of Health guidelines.

Task and vestibular stimulus

Each animal was seated comfortably in a monkey chair and their head was fixed to the chair via a light-weight plastic ring that was anchored to the skull using titanium inverted T-bolts and dental acrylic. This head-restraint ring was attached, at 3 points, to a collar that was embedded within a plate on top of the chair (Fig. 1D). The collar could rotate on ball bearings within the plate on top of the chair. When the stop pin was in place, the head was fixed in primary position. When the stop pin was removed, the head was free to rotate in the horizontal plane (yaw rotation about the center of the head). A head coil, which was attached to the outside of the collar, was used to track head position. A laser mounted on top of the collar, which rotated together with the monkey’s head, projected a green spot of light onto the display screen and was used to provide feedback about current head position. The monkey chair, magnetic field coil (CNC Engineering, Seattle, WA), tangent screen and projector (Christie Digital Mirage 2000; Christie, Cyrus, CA) were all secured to a six degree-of-freedom motion platform (MOOG 6DOF2000E; Moog, East Aurora, NY) (Fig. 1A) that allowed physical translation along any axis in three dimensions (Fetsch et al., 2007; Gu et al., 2006). Fixation targets were rear-projected onto the screen, which was positioned 30cm in front of the monkey and subtended 90°×90° of visual angle.

At the start of each trial, a head target (green cross, Fig. 1E and F) was presented on the screen and the head-fixed laser was turned on. The monkey was required to align the laser spot with the head target by rotating its head. After the head fixation target was acquired and maintained within a 2°×2° window for 300ms, an eye target (orange square) appeared. The monkey was required to fixate this target, within a 2°×2° window, and maintain both head and eye fixation for another 300ms. Subsequently, the monkey had to maintain both eye and head fixations throughout the 1s vestibular stimulus presentation and for an additional 0.5s after stimulus offset. A juice reward was given after each successful trial. Although no visual motion stimuli were presented on the display, there was some background illumination from the projector. However, the sides and top of the coil frame were covered with black material such that the monkey’s field of view was restricted to the tangent screen. Thus, no allocentric cues were available to specify position in the room; this was important as a previous study showed that such cues could affect responses to heading in area MSTd (Froehler and Duffy, 2002).

By manipulating the relative positions of eye and head targets, we designed the task to separate eye-, head- and body-centered spatial reference frames. To distinguish eye- and head-centered reference frames, eye position was varied relatively to the head (Eye-vs-Head condition, Fig. 1E). The head target was presented directly in front of the animal (0°), while the eye target was presented at one of three locations: left (−20°), straight ahead (0°), or right (20°). Thus, this condition included three combinations of [eye relative to head, head relative to body]: [−20°, 0°], [0°, 0°] and [20°, 0°]. Similarly, head- and body-centered spatial reference frames were distinguished by varying head position relative to the body, while keeping eye-in-head position constant (Head-vs-Body condition, Fig. 1F). Both the eye and head targets were presented together at three locations: left (−20°), straight ahead (0°), and right (20°). This resulted in three combinations of eye and head positions: [0°, −20°], [0°, 0°] and [0°, 20°]. Since the [0°, 0°] combination appears in both Eye-vs-Head and Head-vs-Body conditions, there were a total of five distinct combinations of eye and head target positions: [0°, −20°], [−20°, 0°], [0°, 0°], [20°, 0°], [0°, 20°]. These were randomly interleaved in a single block of trials. Video observations and control measurements confirmed that there was little change in trunk orientation associated with changes in head orientation (Supplementary Methods and Supplementary Figure S2).

Translation of the animal by the motion platform followed a Gaussian velocity profile: duration = 1s; displacement = 13cm; peak acceleration ≅ 0.1G (≅0.98 m/s2; peak velocity ≅0.30 m/s) (Fig. 1C). Translation directions were limited to the horizontal plane and ten motion directions were tested (0°, 45°, 70°, 90°, 110°, 135°, 180°, 225°, 270°, 315°), where 90° is straight forward, 0° is rightward, and 180° is leftward (Fig. 1B). The directions 20° to the left and right of straight ahead were included to align with the directions of the eccentric eye and head targets.

Neural recordings

A plastic Delrin grid (3.5 × 5.5 × 0.5 cm), containing staggered rows of holes (0.8 mm spacing), was stereotaxically attached inside the head cap using dental acrylic. The grid was positioned in the horizontal plane and extended from the midline to the areas overlying the PIVC, VIP and MSTd bilaterally. Before recording, the three areas were initially localized via structural MRI scans (Gu et al., 2006). To better localize the subset of grid holes for each target area, detailed mapping was performed via electrode penetrations. The target areas were identifying by patterns of white and gray matter transitions, as well as neuronal response properties (Chen et al., 2010, 2011b, c; Gu et al., 2006), as detailed below.

To map PIVC, we identified the medial tip of the lateral sulcus (LS) and moved laterally until responses to sinusoidal vestibular stimuli could no longer be found on the upper bank of the LS. At the anterior end of PIVC, the upper bank of the LS was the first (and only) gray matter responding to vestibular stimuli. The posterior end of PIVC is the border with the visual posterior sylvian area (VPS). PIVC neurons do not respond to optic flow stimuli, but VPS neurons have strong optic flow responses (Chen et al., 2010, 2011b).

To map VIP, we identified the medial tip of the intraparietal sulcus (IPS) and moved laterally until directionally selective visual responses could no longer be found. At the anterior end of VIP, visually responsive neurons gave way to purely somatosensory neurons in the fundus. At the posterior end, there was a transition to visual neurons that were not selective for motion (Chen et al., 2011c). VIP neurons generally responded strongly to large random-dot patches (>10°×10°), but weakly to small patches. For most neurons, receptive fields were centered in the contralateral visual field, but some extended into the ipsilateral field and included the fovea.

MSTd was identified as a visually responsive region, lateral and slightly posterior to VIP, close to the medial tip of the superior temporal sulcus (STS) and extending laterally ~2–4mm (Gu et al., 2006). MSTd neurons had large receptive fields often centered in the contralateral visual field and often containing the fovea and portions of the ipsilateral visual field. To avoid confusion with the lateral subdivision of MST (MSTl), we targeted our penetrations to the medial and posterior portions of MSTd. At these locations, penetrations typically encountered portions of area MT with fairly eccentric receptive fields, after passing through MSTd and the lumen of the STS (Gu et al., 2006).

Recordings were made using tungsten microelectrodes (FHC, Bowdoinham, ME) that were inserted into the brain via transdural guide tubes. Each neuron was first tested, in complete darkness (projector off), with sinusoidal vestibular stimuli involving translation (0.5Hz, ±10cm) along the lateral and forward/backward directions. Only cells with clear response modulations to sinusoidal vestibular stimuli were further tested with the heading tuning protocols described above. Data were collected in PIVC, VIP and MSTd from four hemispheres of two monkeys, E and Q (Fig. 1G; see also Supplemental Figure S1 for recording locations on a flattened MRI map). For the VIP recordings in monkey E, optic flow stimuli (Chen et al., 2011c) were interleaved with the vestibular heading stimuli. Results were similar between the two animals (Fig. 4), thus data were pooled across animals for all population analyses.

Data analysis

All analyses were done in Matlab (Mathworks, Natick, MA). Neurons included in the analyses were required to have at least three repetitions for each distinct stimulus condition (PIVC: n=100, 60 from E, 40 from Q; VIP: n=194, 96 from E, 98 from Q; MSTd: n=107, 70 from E, 37 from Q), and most neurons (88%) were tested with five or more repetitions. Each repetition consisted of 50 trials (10 headings × 5 eye/head position combinations).

Peristimulus time histograms (PSTHs) were constructed for each heading and each combination of eye and head positions (e.g., Fig. 2A). Spikes were grouped into 50ms time bins and the data were smoothed by a 100ms boxcar filter. Tuning curves for each condition (Eye-vs-Head and Head-vs-Body) were constructed by plotting firing rate as a function of heading. Firing rates were computed in a 400ms window centered on the “peak time” of each neuron (Chen et al., 2010). To compute peak time, firing rates were computed in many different 400ms time windows spanning the range of the data in 25 ms steps. For each 400ms window, a one-way ANOVA (response by heading) was performed for each combination of eye and head positions. The peak time was defined as the center of the 400ms window for which the neuronal response reached its maximum across all stimulus conditions. Heading tuning was considered significant if the ANOVA was significant for five contiguous time points centered on the peak time (p<0.05, one-way ANOVA). Neurons with significant tuning curves for at least two of the three eye and head position combinations in either the Eye-vs-Head or Head-vs-Body condition were analyzed further.

We adopted two main approaches to characterizing how tuning curves shift with eye and head position (Fetsch et al., 2007), as described below. In addition, a third approach is described in Supplementary Methods and Supplementary Figure S3.

(1) Displacement Index (DI)

The amount of shift between a pair of tuning curves was quantified by computing a cross-covariance metric called the displacement index (DI) (Avillac et al., 2005; Fetsch et al., 2007):

| (1) |

Here, k (in degrees) is the shift between a pair of tuning curves (denoted Ri and Rj), and the superscript above k refers to the maximum covariance between the tuning curves as a function of k. The denominator represents the difference between the two eye or head positions (Pi and Pj) at which the tuning functions were measured. If the shift between a pair of tuning curves is equal to the change in eye or head position, the DI will equal 1. If no shift occurs, the DI will equal 0. If all three tuning curves in each condition have significant modulation, then three DIs are computed (one for each distinct pair of the 3 tuning curves) and we report the average DI in these cases. If only two of the three tuning curves are significant, then only the DI computed from these two tuning curves is reported. The number of neurons that met these criteria were: for the Eye-vs-Head condition, PIVC: n=65 (35 from E, 30 from Q), VIP: n=76 (36 from E, 40 from Q), MSTd: n=53 (39 from E, 14 from Q). For the Head-vs-Body condition, PIVC: n=66 (35 from E, 31 from Q), VIP: n=78 (38 from E, 40 from Q), MSTd: n=54 (39 from E, 15 from Q).

To classify the spatial reference frames of each neuron based on DI measurements, a confidence interval (CI) was computed for each DI value using a bootstrap method. Bootstrapped tuning curves were generated by re-sampling (with replacement) the data for each motion direction and then a DI was computed from the bootstrapped data. This was repeated 1000 times to produce a distribution of DIs from which a 95% CI was derived (percentile method). A DI was considered significantly different from a particular value (either 0 or 1) if its 95% CI did not include that value. Thus, each neuron was classified as eye-centered if the CIs in both Eye-vs-Head and Head-vs-Body conditions did not include 0 but included 1, head-centered if the CI in Eye-vs-Head condition included 0 but did not include 1 and the CI in Head-vs-Body condition did not include 0 but included 1, and body-centered if the CIs in both Eye-vs-Head and Head-vs-Body conditions included 0 but did not include 1. If a neuron did not satisfy any of these conditions, it was labeled as unclassified.

(2) Independent fits of von Mises functions

In this analysis, each tuning curve was fit independently with a von Mises function (Fetsch et al., 2007):

| (2) |

where A is the amplitude, θp is the preferred heading, σ is the tuning width, and rb is the baseline response level. Variations in the values of A across eye or head positions were used to quantify gain field effects, whereas variations in θp were used to quantify tuning curve shifts. Specifically, we computed the difference in θp between left (−20°) and center (0°) eye/head positions (θL20 − θ0), as well as the difference between right (20°) and center positions (θR20 − θ0). This was done for both the Eye-vs-Head and Head-vs-Body conditions. For response amplitude (A), we computed amplitude ratios between left and center positions (AL20/A0) or between right and center positions (AR20/A0).

Note that Eye-vs-Head and Head-vs-Body conditions both manipulate gaze direction (eye-in-world) by changing eye-in-head or head-in-world, respectively. Thus, if neuronal tuning curves are scaled by a gaze position signal, a significant positive correlation is expected between response amplitude ratios for the Eye-vs-Head and Head-vs-Body conditions. To assess this possibility, amplitude ratios (AL20/A0, AR20/A0) computed from the Head-vs-Body condition are compared to those from the Eye-vs-Head condition (Fig. 7B). To be included in this analysis all three tuning curves needed to pass the significance criterion described above and needed to be well fit by Eq. (2), as indicated by R2 > 0.6. For the Eye-vs-Head condition, the samples that passed these criteria were: PIVC, n=58 (31 from E, 27 from Q); VIP, n=74 (34 from E, 40 from Q); MSTd, n=43 (35 from E, 8 from Q). For the Head-vs-Body condition, the corresponding numbers were: PIVC, n=57 (31 from E, 26 from Q); VIP, n=72 (34 from E, 38 from Q); MSTd, n=47 (37 from E, 10 from Q).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. E. Klier for helping with the writing, as well as Amanda Turner and Jing Lin for excellent technical assistance. The study was supported by National Institutes of Health grants R01- EY017866 (to DEA) and R01-EY016178 (to GCD).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Akbarian S, Grusser OJ, Guldin WO. Thalamic connections of the vestibular cortical fields in the squirrel monkey (Saimiri sciureus) J Comp Neurol. 1992;326:423–441. doi: 10.1002/cne.903260308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen RA, Snyder LH, Bradley DC, Xing J. Multimodal representation of space in the posterior parietal cortex and its use in planning movements. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1997;20:303–330. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.20.1.303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arguin M, Bub DN. Evidence for an independent stimulus-centered spatial reference frame from a case of visual hemineglect. Cortex. 1993;29:349–357. doi: 10.1016/s0010-9452(13)80188-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asanuma C, Thach WT, Jones EG. Distribution of cerebellar terminations and their relation to other afferent terminations in the ventral lateral thalamic region of the monkey. Brain Res. 1983;286:237–265. doi: 10.1016/0165-0173(83)90015-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avillac M, Deneve S, Olivier E, Pouget A, Duhamel JR. Reference frames for representing visual and tactile locations in parietal cortex. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:941–949. doi: 10.1038/nn1480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azanon E, Longo MR, Soto-Faraco S, Haggard P. The posterior parietal cortex remaps touch into external space. Curr Biol. 2010;20:1304–1309. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.05.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berlucchi G, Aglioti S. The body in the brain: neural bases of corporeal awareness. Trends Neurosci. 1997;20:560–564. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(97)01136-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berlucchi G, Aglioti SM. The body in the brain revisited. Exp Brain Res. 2010;200:25–35. doi: 10.1007/s00221-009-1970-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bockisch CJ, Haslwanter T. Vestibular contribution to the planning of reach trajectories. Exp Brain Res. 2007;182:387–397. doi: 10.1007/s00221-007-0997-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolognini N, Maravita A. Proprioceptive alignment of visual and somatosensory maps in the posterior parietal cortex. Curr Biol. 2007;17:1890–1895. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.09.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boussaoud D, Ungerleider LG, Desimone R. Pathways for motion analysis: cortical connections of the medial superior temporal and fundus of the superior temporal visual areas in the macaque. J Comp Neurol. 1990;296:462–495. doi: 10.1002/cne.902960311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bremmer F, Ilg UJ, Thiele A, Distler C, Hoffmann KP. Eye position effects in monkey cortex. I. Visual and pursuit-related activity in extrastriate areas MT and MST. J Neurophysiol. 1997;77:944–961. doi: 10.1152/jn.1997.77.2.944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bremmer F, Klam F, Duhamel JR, Ben Hamed S, Graf W. Visual-vestibular interactive responses in the macaque ventral intraparietal area (VIP) Eur J Neurosci. 2002;16:1569–1586. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2002.02206.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britten KH, van Wezel RJ. Electrical microstimulation of cortical area MST biases heading perception in monkeys. Nat Neurosci. 1998;1:59–63. doi: 10.1038/259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brotchie PR, Andersen RA, Snyder LH, Goodman SJ. Head position signals used by parietal neurons to encode locations of visual stimuli. Nature. 1995;375:232–235. doi: 10.1038/375232a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang SW, Papadimitriou C, Snyder LH. Using a compound gain field to compute a reach plan. Neuron. 2009;64:744–755. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang SW, Snyder LH. Idiosyncratic and systematic aspects of spatial representations in the macaque parietal cortex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:7951–7956. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0913209107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen A, DeAngelis GC, Angelaki DE. Macaque parieto-insular vestibular cortex: responses to self-motion and optic flow. J Neurosci. 2010;30:3022–3042. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4029-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen A, DeAngelis GC, Angelaki DE. A comparison of vestibular spatiotemporal tuning in macaque parietoinsular vestibular cortex, ventral intraparietal area, and medial superior temporal area. J Neurosci. 2011a;31:3082–3094. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4476-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen A, DeAngelis GC, Angelaki DE. Convergence of vestibular and visual self-motion signals in an area of the posterior sylvian fissure. J Neurosci. 2011b;31:11617–11627. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1266-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen A, DeAngelis GC, Angelaki DE. Representation of vestibular and visual cues to self-motion in ventral intraparietal cortex. J Neurosci. 2011c;31:12036–12052. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0395-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen YE, Andersen RA. A common reference frame for movement plans in the posterior parietal cortex. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2002;3:553–562. doi: 10.1038/nrn873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colby CL, Duhamel JR, Goldberg ME. Ventral intraparietal area of the macaque: anatomic location and visual response properties. J Neurophysiol. 1993;69:902–914. doi: 10.1152/jn.1993.69.3.902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demougeot L, Toupet M, Van Nechel C, Papaxanthis C. Action representation in patients with bilateral vestibular impairments. PLoS One. 2011;6:e26764. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0026764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deneve S, Latham PE, Pouget A. Efficient computation and cue integration with noisy population codes. Nat Neurosci. 2001;4:826–831. doi: 10.1038/90541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Driver J, Baylis GC, Goodrich SJ, Rafal RD. Axis-based neglect of visual shapes. Neuropsychologia. 1994;32:1353–1365. doi: 10.1016/0028-3932(94)00068-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duffy CJ. MST neurons respond to optic flow and translational movement. J Neurophysiol. 1998;80:1816–1827. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.80.4.1816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duhamel JR, Bremmer F, Ben Hamed S, Graf W. Spatial invariance of visual receptive fields in parietal cortex neurons. Nature. 1997;389:845–848. doi: 10.1038/39865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebata S, Sugiuchi Y, Izawa Y, Shinomiya K, Shinoda Y. Vestibular projection to the periarcuate cortex in the monkey. Neurosci Res. 2004;49:55–68. doi: 10.1016/j.neures.2004.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fetsch CR, Pouget A, DeAngelis GC, Angelaki DE. Neural correlates of reliability-based cue weighting during multisensory integration. Nat Neurosci. 2012;15:146–154. doi: 10.1038/nn.2983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fetsch CR, Wang S, Gu Y, Deangelis GC, Angelaki DE. Spatial reference frames of visual, vestibular, and multimodal heading signals in the dorsal subdivision of the medial superior temporal area. J Neurosci. 2007;27:700–712. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3553-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Froehler MT, Duffy CJ. Cortical neurons encoding path and place: where you go is where you are. Science. 2002;295:2462–2465. doi: 10.1126/science.1067426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukushima J, Akao T, Takeichi N, Kurkin S, Kaneko CR, Fukushima K. Pursuit-related neurons in the supplementary eye fields: discharge during pursuit and passive whole body rotation. J Neurophysiol. 2004;91:2809–2825. doi: 10.1152/jn.01128.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groh JM, Sparks DL. Saccades to somatosensory targets. III. eye-position-dependent somatosensory activity in primate superior colliculus. J Neurophysiol. 1996;75:439–453. doi: 10.1152/jn.1996.75.1.439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grusser OJ, Pause M, Schreiter U. Localization and responses of neurones in the parieto-insular vestibular cortex of awake monkeys (Macaca fascicularis) J Physiol. 1990a;430:537–557. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1990.sp018306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grusser OJ, Pause M, Schreiter U. Vestibular neurones in the parieto-insular cortex of monkeys (Macaca fascicularis): visual and neck receptor responses. J Physiol. 1990b;430:559–583. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1990.sp018307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu Y, Angelaki DE, Deangelis GC. Neural correlates of multisensory cue integration in macaque MSTd. Nat Neurosci. 2008;11:1201–1210. doi: 10.1038/nn.2191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu Y, DeAngelis GC, Angelaki DE. A functional link between area MSTd and heading perception based on vestibular signals. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10:1038–1047. doi: 10.1038/nn1935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu Y, DeAngelis GC, Angelaki DE. Contributions of visual and vestibular signals to 3D heading selectivity in area FEFp. SFN. 2010:74.4. [Google Scholar]

- Gu Y, Deangelis GC, Angelaki DE. Causal links between dorsal medial superior temporal area neurons and multisensory heading perception. J Neurosci. 2012;32:2299–2313. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5154-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu Y, Watkins PV, Angelaki DE, DeAngelis GC. Visual and nonvisual contributions to three-dimensional heading selectivity in the medial superior temporal area. J Neurosci. 2006;26:73–85. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2356-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Israel I, Grasso R, Georges-Francois P, Tsuzuku T, Berthoz A. Spatial memory and path integration studied by self-driven passive linear displacement. I. Basic properties. J Neurophysiol. 1997;77:3180–3192. doi: 10.1152/jn.1997.77.6.3180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jay MF, Sparks DL. Sensorimotor integration in the primate superior colliculus. II. Coordinates of auditory signals. J Neurophysiol. 1987;57:35–55. doi: 10.1152/jn.1987.57.1.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karnath HO, Christ K, Hartje W. Decrease of contralateral neglect by neck muscle vibration and spatial orientation of trunk midline. Brain. 1993;116 (Pt 2):383–396. doi: 10.1093/brain/116.2.383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karnath HO, Dieterich M. Spatial neglect--a vestibular disorder? Brain. 2006;129:293–305. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy PM, Inglis JT. Interaction effects of galvanic vestibular stimulation and head position on the soleus H reflex in humans. Clin Neurophysiol. 2002;113:1709–1714. doi: 10.1016/s1388-2457(02)00238-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klam F, Graf W. Discrimination between active and passive head movements by macaque ventral and medial intraparietal cortex neurons. J Physiol. 2006;574:367–386. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.103697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleine JF, Guan Y, Kipiani E, Glonti L, Hoshi M, Buttner U. Trunk position influences vestibular responses of fastigial nucleus neurons in the alert monkey. J Neurophysiol. 2004;91:2090–2100. doi: 10.1152/jn.00849.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klemen J, Chambers CD. Current perspectives and methods in studying neural mechanisms of multisensory interactions. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2012;36:111–133. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2011.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klier EM, Angelaki DE. Spatial updating and the maintenance of visual constancy. Neuroscience. 2008;156:801–818. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.07.079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee B, Pesaran B, Andersen RA. Area MSTd neurons encode visual stimuli in eye coordinates during fixation and pursuit. J Neurophysiol. 2011;105:60–68. doi: 10.1152/jn.00495.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis JW, Van Essen DC. Corticocortical connections of visual, sensorimotor, and multimodal processing areas in the parietal lobe of the macaque monkey. J Comp Neurol. 2000;428:112–137. doi: 10.1002/1096-9861(20001204)428:1<112::aid-cne8>3.0.co;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li N, Angelaki DE. Updating visual space during motion in depth. Neuron. 2005;48:149–158. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macpherson JM, Everaert DG, Stapley PJ, Ting LH. Bilateral vestibular loss in cats leads to active destabilization of balance during pitch and roll rotations of the support surface. J Neurophysiol. 2007;97:4357–4367. doi: 10.1152/jn.01338.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marlinski V, McCrea RA. Activity of ventroposterior thalamus neurons during rotation and translation in the horizontal plane in the alert squirrel monkey. J Neurophysiol. 2008;99:2533–2545. doi: 10.1152/jn.00761.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marlinski V, McCrea RA. Self-motion signals in vestibular nuclei neurons projecting to the thalamus in the alert squirrel monkey. J Neurophysiol. 2009;101:1730–1741. doi: 10.1152/jn.90904.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCollum G, Klam F, Graf W. Face-infringement space: the frame of reference of the ventral intraparietal area. Biol Cybern. 2012;106:219–239. doi: 10.1007/s00422-012-0491-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng H, Angelaki DE. Responses of ventral posterior thalamus neurons to three-dimensional vestibular and optic flow stimulation. J Neurophysiol. 2010;103:817–826. doi: 10.1152/jn.00729.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng H, May PJ, Dickman JD, Angelaki DE. Vestibular signals in primate thalamus: properties and origins. J Neurosci. 2007;27:13590–13602. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3931-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meredith MA, Stein BE. Spatial determinants of multisensory integration in cat superior colliculus neurons. J Neurophysiol. 1996;75:1843–1857. doi: 10.1152/jn.1996.75.5.1843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mergner T, Rottler G, Kimmig H, Becker W. Role of vestibular and neck inputs for the perception of object motion in space. Exp Brain Res. 1992;89:655–668. doi: 10.1007/BF00229890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mergner T, Siebold C, Schweigart G, Becker W. Human perception of horizontal trunk and head rotation in space during vestibular and neck stimulation. Exp Brain Res. 1991;85:389–404. doi: 10.1007/BF00229416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moon S, Lee B, Na D. Therapeutic effects of caloric stimulation and optokinetic stimulation on hemispatial neglect. J Clin Neurol. 2006;2:12–28. doi: 10.3988/jcn.2006.2.1.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muir GM, Brown JE, Carey JP, Hirvonen TP, Della Santina CC, Minor LB, Taube JS. Disruption of the head direction cell signal after occlusion of the semicircular canals in the freely moving chinchilla. J Neurosci. 2009;29:14521–14533. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3450-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullette-Gillman OA, Cohen YE, Groh JM. Eye-centered, head-centered, and complex coding of visual and auditory targets in the intraparietal sulcus. J Neurophysiol. 2005;94:2331–2352. doi: 10.1152/jn.00021.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nashner LM, Wolfson P. Influence of head position and proprioceptive cues on short latency postural reflexes evoked by galvanic stimulation of the human labyrinth. Brain Res. 1974;67:255–268. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(74)90276-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osler CJ, Reynolds RF. Dynamic transformation of vestibular signals for orientation. Exp Brain Res. 2012;223:189–197. doi: 10.1007/s00221-012-3250-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page WK, Duffy CJ. Heading representation in MST: sensory interactions and population encoding. J Neurophysiol. 2003;89:1994–2013. doi: 10.1152/jn.00493.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pouget A, Deneve S, Duhamel JR. A computational perspective on the neural basis of multisensory spatial representations. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2002;3:741–747. doi: 10.1038/nrn914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pouget A, Sejnowski TJ. A new view of hemineglect based on the response properties of parietal neurones. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1997;352:1449–1459. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1997.0131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renzi C, Bruns P, Heise KF, Zimerman M, Feldheim JF, Hummel FC, Roder B. Spatial Remapping in the Audio-tactile Ventriloquism Effect: A TMS Investigation on the Role of the Ventral Intraparietal Area. J Cogn Neurosci. 2013 doi: 10.1162/jocn_a_00362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schicke T, Roder B. Spatial remapping of touch: confusion of perceived stimulus order across hand and foot. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:11808–11813. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601486103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlack A, Sterbing-D’Angelo SJ, Hartung K, Hoffmann KP, Bremmer F. Multisensory space representations in the macaque ventral intraparietal area. J Neurosci. 2005;25:4616–4625. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0455-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaikh AG, Meng H, Angelaki DE. Multiple reference frames for motion in the primate cerebellum. J Neurosci. 2004;24:4491–4497. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0109-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder LH, Grieve KL, Brotchie P, Andersen RA. Separate body- and world-referenced representations of visual space in parietal cortex. Nature. 1998;394:887–891. doi: 10.1038/29777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- St George RJ, Fitzpatrick RC. The sense of self-motion, orientation and balance explored by vestibular stimulation. J Physiol. 2011;589:807–813. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2010.197665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi K, Gu Y, May PJ, Newlands SD, DeAngelis GC, Angelaki DE. Multimodal coding of three-dimensional rotation and translation in area MSTd: comparison of visual and vestibular selectivity. J Neurosci. 2007;27:9742–9756. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0817-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vallar G. Spatial hemineglect in humans. Trends Cogn Sci. 1998;2:87–97. doi: 10.1016/s1364-6613(98)01145-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Zhang M, Cohen IS, Goldberg ME. The proprioceptive representation of eye position in monkey primary somatosensory cortex. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10:640–646. doi: 10.1038/nn1878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoder RM, Taube JS. Head direction cell activity in mice: robust directional signal depends on intact otolith organs. J Neurosci. 2009;29:1061–1076. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1679-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.