Abstract

Multiple myeloma cells are highly sensitive to the oncolytic effects of vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV), which specifically targets and kills cancer cells. Myeloma cells are also exquisitely sensitive to the cytotoxic effects of the clinically-approved proteasome inhibitor bortezomib. Therefore, we sought to determine if the combination of VSV and bortezomib would enhance tumor cell killing. However, as shown here, combining these two agents in vitro results in antagonism. We show that bortezomib inhibits VSV replication and spread. We found that bortezomib inhibits VSV-induced NF-κB activation and, using the NF-κB-specific inhibitor BMS-345541, that VSV requires NF-κB activity in order to efficiently spread in myeloma cells. In contrast to other cancer cell lines, viral titer is not recovered by BMS-345541 when myeloma cells are pre-treated with interferon (IFN)-β. Thus, inhibiting NF-κB activity, either with bortezomib or BMS-345541, results in reduced VSV titers in myeloma cells in vitro. However, when VSV and bortezomib are combined in vivo, in two syngeneic, immunocompetent myeloma models, the combination reduces tumor burden to a greater degree than VSV as a single agent. Intra-tumoral VSV viral load is unchanged when mice are concomitantly treated with bortezomib as compared to VSV treatment alone. To our knowledge, this is the first report analyzing the combination of VSV and bortezomib in vivo. Although antagonism between VSV and bortezomib is seen in vitro, analyzing these cells in the context of their host environment shows that bortezomib enhances VSV response, suggesting that this combination will also enhance response in myeloma patients.

Keywords: Multiple myeloma, oncolytic viruses, vesicular stomatitis virus, bortezomib

Introduction

Multiple myeloma, the second most common hematologic malignancy, causes greater than 10,000 deaths per year in the United States [1, 2]. Myeloma patients have large numbers of clonal, antibody-secreting plasma cells in their bone marrow and typically suffer from end organ damage characterized by hypercalcemia, renal insufficiency, anemia and bone lesions, and increased infections [2–4]. NF-κB is constitutively activated in myeloma, with a number of NF-κB-activating gene mutations reported in myeloma cell lines and primary specimens [5, 6]. Additionally, NF-κB is overexpressed in drug resistant myeloma cell lines and elevated in patients at time of relapse [7–9].

The NF-κB family of transcription factors regulates genes involved in cell survival and proliferation, tumorigenesis, apoptosis, angiogenesis, chemoresistance, and innate and adaptive immune responses [10, 11]. NF-κB can also induce an anti-viral state via transcriptional activation of type I interferons (IFNs) [12]. There are five different NF-κB subunits, RelA (p65), RelB, c-Rel, p50 (NF-κB1), and p52 (NF-κB2), which form dimers that are sequestered in the cytoplasm by inhibitor of NF-κB (IκB) proteins such as IκBα [13]. NF-κB can be activated by various stimuli, including growth factors, cytokines and chemokines, and microbial pathogens [13, 14]. Once activated, the IκB kinase (IKK) complex phosphorylates IκB, which serves as a signal for degradation of this protein by the proteasome [14]. Following proteasomal degradation of IκBα, the NF-κB dimers translocate to the nucleus and activate gene transcription.

The anti-myeloma effects of the proteasome inhibitor bortezomib (PS-341; Velcade) have been attributed in part to inhibition of NF-κB activity [15, 16]. Pre-clinically, myeloma cells have proven to be highly sensitive to the cytotoxic effects of bortezomib, both in vitro and in vivo [15–19]. Bortezomib received accelerated approval for the treatment of relapsed myeloma in 2003 and now, because of its marked clinical activity, is commonly used as frontline therapy in combination with other anti-myeloma agents [19, 20]. Unfortunately, however, although bortezomib-based treatment regimens have prolonged progression-free survival, this disease remains incurable with a current median overall survival rate of approximately six years [20, 21]. Thus, alternative therapeutic options are essential for the successful treatment of this disease.

Virotherapy is a novel therapeutic currently being explored in the clinic for the treatment of certain cancers, including multiple myeloma. Oncolytic viruses selectively target tumor cells by exploiting differences between tumor and normal cells, and a number of these viruses have entered clinical trials in recent years for use as anti-cancer agents [22, 23]. Pre-clinically, the oncolytic vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV) has shown great potential for the treatment of a variety of tumors, including multiple myeloma [24, 25]. VSV is a bullet-shaped, negative-sense, single-stranded RNA virus of the Rhabdoviridae family that does not integrate its genome into the host cell [24]. The genome of VSV encodes for five proteins, namely the nucleocapsid (N), phosphoprotein (P), peripheral matrix protein (M), surface glycoprotein (G), and large protein or polymerase (L) [26]. This virus, which is typically a pathogen of livestock and relatively nonpathogenic to humans, can replicate to high titers in a wide variety of cell types, including tumor cells [27–29].

VSV is attenuated in normal, interferon (IFN)-responsive cells. IFN production following viral infection, which is induced by activation of transcription factors such as NF-κB, IFN-regulatory factor (IRF)-3, and IRF-7, ultimately leads to inhibition of viral replication [30]. However, IFN signaling is defective in many tumor cells, and so VSV can replicate and maintain its oncolytic activity in these cells [31, 32]. To this end, the IFN-β gene has been inserted into the VSV genome as a means to enhance the safety and tumor-specificity of this virus, and VSV expressing IFN-β has been shown to enhance the therapeutic efficacy of VSV treatment [33–36]. Myeloma cells, which are highly unresponsive to the anti-viral effects of IFN, even in comparison to other cancer cells, are exquisitely sensitive to VSV-induced oncolysis [37].

In this report, we studied the effects of combination VSV and bortezomib on myeloma in vitro and in vivo. In glioma cell lines, specific inhibition of NF-κB has been shown to attenuate the anti-viral effects of IFN, resulting in increased VSV titers [38]. Since bortezomib inhibits NF-κB, and since myeloma cells are highly sensitive to both the oncolytic effects of VSV infection and to bortezomib, we hypothesized that this combination would be synergistic. Interestingly, however, we found the opposite in vitro. We show that bortezomib and VSV are antagonistic in myeloma cell lines and that bortezomib inhibits VSV replication and spread in these cells. Similarly, antagonism between bortezomib and VSV has been reported in vitro in other cell types as well [39, 40]. In vivo, however, using two syngeneic, immunocompetent mouse myeloma models, we found that bortezomib does not affect intra-tumoral VSV titers and that this drug actually enhances tumor reduction when compared to single-agent VSV treatment. To our knowledge, this is the first report studying the combination of VSV and bortezomib in vivo. Therefore, despite the antagonistic results seen in vitro, based on our in vivo data, when myeloma cells are in the context of their syngeneic host environment, we postulate that combination VSV and bortezomib therapy will be beneficial in the clinic for the treatment of myeloma.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture, viruses and reagents

All cell lines routinely tested negative for mycoplasma contamination. Unless otherwise indicated, cell lines were cultured in media supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 mg/ml streptomycin. The U266 human myeloma cell line was obtained from American Type Cell Culture (ATCC) and grown in RPMI. MPC-11 murine myeloma cells (ATCC), B16 murine melanoma cells (R Vile, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN), and U-87 MG human glioblastoma cells (U87; ATCC) were maintained in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM). The 5TGM1 murine myeloma cell line, obtained from Dr. Babatunde Oyajobi (UT Health Sciences Center, San Antonio, TX, USA), was cultured in Iscove's Modified Dulbecco Medium. Baby hamster kidney cells (BHK-21; ATCC) were grown in DMEM supplemented with 5% FBS, 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 mg/ml streptomycin.

The clinical-grade vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV) strains used in these studies were manufactured in the Mayo Clinic Viral Vector Production Facility. VSV coding for green fluorescent protein (VSV-GFP; Indiana strain) was originally obtained from GN Barber (University of Miami School of Medicine, Miami, FL). VSV coding for murine IFNβ and the thyroidal sodium iodide symporter (NIS), VSV-mIFN-NIS, was generated in our laboratory as previously described [37]. NIS was inserted into the VSV genome to allow for non-invasive in vivo imaging and to facilitate131I radiotherapy, but NIS function was not utilized in the present studies.

Bortezomib (PS-431; Velcade®) was purchased from Millennium Pharmaceuticals (Cambridge, MA); BMS-345541 from Calbiochem (San Diego, CA); and murine and human IFNβ from PBL Interferon Source (Piscataway, NJ).

Cytotoxicity assays and median dose effect analyses

3-(4,5-Dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) analysis was used to measure cytotoxicity in U266 and 5TGM1 cells (2×104 cells/well) following treatment with various doses of bortezomib or BMS-345541, infection with VSV-GFP, or the simultaneous combination of bortezomib and VSV-GFP or BMS-345541 and VSV-GFP. Cells were infected with VSV-GFP +/− drug for 1 hour in Opti-MEM I Reduced-Serum media (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) at 37°C, followed by replacement with complete (serum-containing) growth medium with or without bortezomib or BMS-345541. Cell viability was analyzed 24 hours post-treatment/infection. Median dose effect analyses were performed as described previously to determine if drug/virus combinations were additive, synergistic or antagonistic [41]. Combination index (CI) values were determined using CompuSyn 3.0.1 software (ComboSyn, Inc., Paramus, NJ), based on the Chou-Talalay median dose effect equation [42].

Flow cytometric analysis

GFP expression following 24 hours infection of myeloma cells with VSV-GFP +/− bortezomib (simultaneous treatment) was analyzed by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS). 1×106 cells were infected with VSV-GFP at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.01, 1 or 3, in the presence or absence of 5 nM or 10 nM bortezomib for 1 hour at 37°C, washed once in PBS, then re-suspended in complete growth media, containing bortezomib where indicated. Samples were harvested 24 hours later. Cells were then fixed on ice for 30 minutes in 4% paraformaldehyde diluted in PBS and washed twice with PBS containing 2% FBS before analysis using a FACScan Plus flow cytometer and CellQuest software (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ).

Growth curve analyses and TCID50 determination

For multi-step and single-step growth curves, myeloma cells were infected at an MOI of 0.01 and 3, respectively. Cells were infected with VSV-GFP in the presence or absence of bortezomib (5 or 10 nM) or BMS-345541 (10 μM) for 1 hour at 37°C. Following infection, cells were cultured in fresh complete growth media, containing bortezomib or BMS-345541 where appropriate. Supernatants were harvested at 8, 18, 24 and 48 hours post-infection/drug treatment and stored at −80°C. Supernatants were then thawed, serially diluted and plated on BHK-21 cells to determine viral titer, indicated as the 50% tissue culture infective dose (TCID50), which was calculated using the Spearman-Karber equation.

For studies using IFNβ, 5TGM1 and B16 cells were pre-treated with murine IFNβ, and U87 with human IFNβ, +/−BMS-345541 for 15 hours prior to infection with VSV-GFP and treatment with BMS-345541. Samples were simultaneously infected with VSV-GFP and treated with BMS-345541 for 1 hour at 37°C, and supernatants were harvested 24 hours post-infection. Supernatants were serially diluted and plated on BHK-21 cells to determine viral titer (TCID50/ml).

Western blot analysis

Whole-cell lysates were prepared by re-suspending the cell pellet in RIPA lysis buffer (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA) containing a Protease Inhibitor Cocktail Solution (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Nuclear extracts were prepared per manufacturer's protocol using the NE-PER Nuclear and Cytoplasmic Extraction Kit (Thermo Scientific). Proteins were separated in a 12% sodium dodecylsulfate-polyacrylamide gel and transferred to a PVDF membrane using a Trans-Blot Turbo transfer system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Membranes were incubated with antibodies against IκBα and p65 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX), as well as the loading controls β-actin (Sigma-Aldrich) and Histone H3 (Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA), and the cytoplasmic protein Cyclophilin A (Cell Signaling). Signals were visualized using Pierce SuperSignal West Dura Chemiluminescent Substrate (Thermo Scientific).

In vivo studies

All animal studies were approved by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Two syngeneic myeloma mouse models were utilized to study the effects of the combination of VSV and bortezomib in vivo. 5×106 MPC-11 or 5TGM1 cells were subcutaneously implanted into the right flank of female BALB/c mice (purchased at 4–6 weeks old; Jackson Laboratories, Bar Harbor, Maine) or C57BL/KaLwRij mice (4–6 weeks old; Harlan CPB, Horst, The Netherlands), respectively. When tumors reached an average size of approximately 0.5 cm in diameter, mice were treated with PBS or VSV-mIFN-NIS (intravenous via the tail vein at indicated TCID50/mouse), bortezomib (1.0 mg/kg, intraperitoneal), or the combination of VSV-mIFN-NIS plus bortezomib. Bortezomib was administered 3X/week for 3 weeks, with the first dose given the same day as the VSV-mIFN-NIS treatment, in the C57BL/KaLwRij mouse model. Tumor size was measured daily using a hand-held caliper. For quantitative (q)-PCR analysis of VSV viral titers within the tumor, BALB/c mice were sacrificed and tumors harvested on days 1 and 2 post-treatment.

RNA extraction and q-PCR analysis

MPC-11 tumors were harvested from BALB/c mice and stored in RNAlater Stabilization Solution (Ambion, Inc., Austin, TX). Tissues were lysed and RNA extracted using a TissueLyser II and RNeasy Plus Mini Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) according to manufacturer's instructions. Q-PCR was performed using forward (5'-TGATAGTACCGGAGGATTGACGAC-3') and reverse (5'-CCTTGCAGTGACATGACTGCTCTT-3') primers and probe (5'-FAMTCGACCACATCTCTGCCTTGTGGCGGTGCA-BHQ1-3') specific to the VSV-N gene, with the TaqMan One-Step RT-PCR Master Mix Reagents Kit (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA). Plates were run on a LightCycler 480 system and analyzed using LightCycler 480 Software (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN). Viral titers (TCID50/ml) were quantitated using a standard curve of known amount of VSV-N RNA.

Statistical analysis

GraphPad Prism Software v. 5.0a (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA) or Microsoft Excel was used for data analysis and graphic representations. Combination index values were determined using CompuSyn software. Two-tailed Student's t-tests were used to compare mean values where indicated, and p-values of <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

VSV and bortezomib are antagonistic in vitro

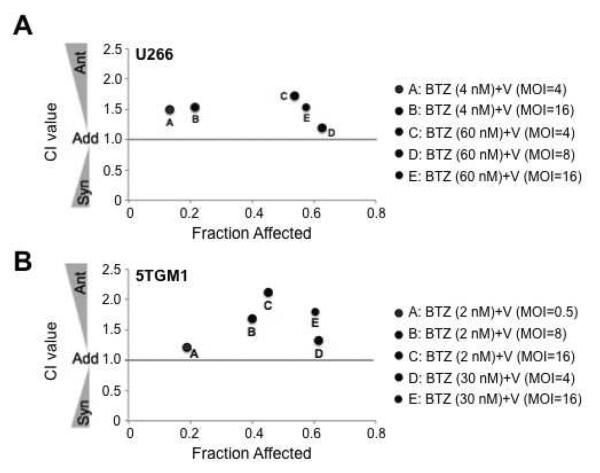

Multiple myeloma cells are highly sensitive to the cytotoxic effects of bortezomib in vitro, in vivo and in patients [18, 19, 43, 44]. Similarly, pre-clinical data shows that these cells are also exquisitely sensitive to the oncolytic effects of VSV infection [25, 33, 37]. Therefore, we combined these two anti-myeloma agents to determine if myeloma cell killing is enhanced when cells are infected with VSV in the presence of bortezomib. The human U266 and murine 5TGM1 myeloma cell lines were infected with varying multiplicities of infection (MOIs) of VSV-GFP, treated with various doses of bortezomib, or simultaneously infected with VSV-GFP and treated with bortezomib. To determine if the virus/bortezomib combination is synergistic, antagonistic or additive, the Chou-Talalay median dose-effect equation was used [41, 42]. Based on this equation and using CompuSyn software, Combination Index (CI) values were generated by comparing the fraction of cells affected (ie –fraction of dead cells) by each agent alone to the fraction of cells affected following simultaneous VSV infection and bortezomib treatment. CI values ranging from 0.9–1.1 indicate near additivity. Values less than 0.9 indicate varying degrees of synergism, ranging from slight synergism to very strong synergism; values greater than 1.1 indicate varying degrees of antagonism, from slight to very strong antagonism as CI values increase [42]. Interestingly, the CI values produced when myeloma cells were simultaneously infected with VSV-GFP and treated with bortezomib were greater than 1.1 in both U266 (Figure 1A) and 5TGM1 (Figure 1B) myeloma cells. Similar results were seen when cells were infected with VSV-mIFN-NIS and treated with bortezomib (data not shown). These results indicate that the combination of VSV and bortezomib is antagonistic in vitro in these myeloma cell lines.

Figure 1. VSV and bortezomib are antagonistic in multiple myeloma cell lines.

The Chou-Talalay median dose effect equation was utilized to determine if the combination of VSV (V) and bortezomib (BTZ) was additive, synergistic or antagonistic in (A) U266 human myeloma and (B) 5TGM1 murine myeloma cells. Cells were infected at various multiplicities of infection (MOIs) in combination with various doses of BTZ. Combination index (CI) values ranging from 0.9–1.1 indicate additivity (Add); CI values less than 1 indicate varying degrees of synergism (Syn); and CI values greater than 1 indicate varying degrees of antagonism (Ant).

Bortezomib inhibits VSV replication and spread

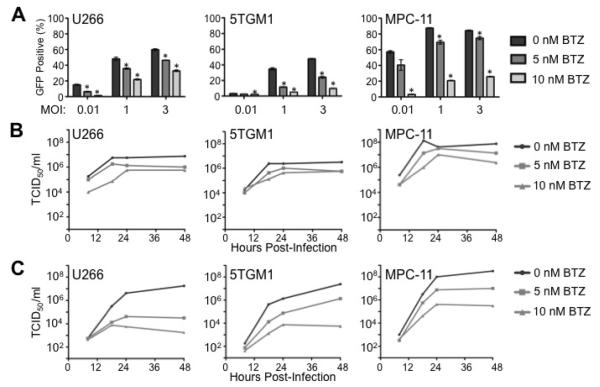

Based on the antagonism seen when myeloma cells are simultaneously treated with bortezomib and infected with VSV, we next wanted to determine if bortezomib affects the growth kinetics of VSV in vitro. Three different myeloma cell lines (human U266 and murine 5TGM1 and MPC-11) were infected for one hour with VSV-GFP in Opti-MEM reduced serum medium in the absence or presence of 5 or 10 nM bortezomib. Importantly, similar to our previously published results with other myeloma cell lines [41], the doses of bortezomib chosen induce only low levels of cytotoxicity in these myeloma cells (in 5TGM1 cells, 5 nM and 10 nM bortezomib induced approximately 5–10% cell death and 20–25% cell death at 24 hours, respectively). Following VSV infection, media was replaced with serum-containing growth medium and samples were harvested 24 hours post-infection. VSV-GFP expression was analyzed by flow cytometry. As seen in Figure 2A, GFP expression increases with increasing MOI of VSV-GFP (MOI=0.01, 1 or 3). However, simultaneous treatment with 5 and 10 nM bortezomib significantly reduces GFP expression in a dose-dependent manner in U266, 5TGM1 and MPC-11 myeloma cells infected with VSV-GFP.

Figure 2. Bortezomib inhibits VSV replication in vitro.

(A) VSV-GFP expression in human U266 and murine 5TGM1 and MPC-11 myeloma cell lines was analyzed via flow cytometry at 24 hours post-VSV infection/simultaneous bortezomib (BTZ) treatment. Cells were infected at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.01, 1 and 3. Error bars represent standard deviations. *p<0.05 (student's t-test, compared to VSV-infected cells at the same MOI without bortezomib). (B) Single-step (MOI=3) and (C) multi-step (MOI=0.01) growth curve analysis following simultaneous infection with VSV-GFP and treatment with bortezomib.

Next, we analyzed the viral growth kinetics of VSV-GFP in the presence of bortezomib (Figure 2B and 2C). To analyze viral replication in the presence and absence of bortezomib, U266, 5TGM1 and MPC-11 cells were infected with VSV-GFP at an MOI of 3. The results of the one-step growth curve show that 10 nM bortezomib reduces viral titers by approximately 10-fold in all three cell lines compared to cells infected with VSV-GFP without bortezomib (Figure 2B). The reduction in viral titer seen when cells are infected at this high MOI indicates that bortezomib inhibits viral replication. Similarly, when multi-step growth curve analysis is performed to study viral spread (MOI=0.01), VSV-GFP viral titers are also largely reduced by concomitant bortezomib treatment. As shown in Figure 2C, VSV-GFP viral titer is reduced in all three myeloma cell lines studied by 1–2 logs when cells are treated simultaneously with 5 nM bortezomib. Up to a 4-log reduction in viral titer is seen with concomitant VSV-GFP infection and treatment with 10 nM bortezomib. Together, our flow cytometry and growth curve results indicate that bortezomib inhibits both the replication and spread of VSV in myeloma cells in vitro.

NF-κB activity is required for robust VSV infection

IκBα, an upstream component of the NF-κB pathway, must be degraded by the proteasome before the NF-κB subunits can translocate to the nucleus and activate transcription of target genes [10]. Bortezomib is a proteasome inhibitor that has been shown to be cytotoxic in myeloma cells, and the cytotoxicity is in part due to inhibition of NF-κB [15, 45]. The role of NF-κB in VSV infection of myeloma cells, however, is still unknown. Other viruses have been shown to both activate or repress NF-κB activity, depending on the specific virus being studied [13].

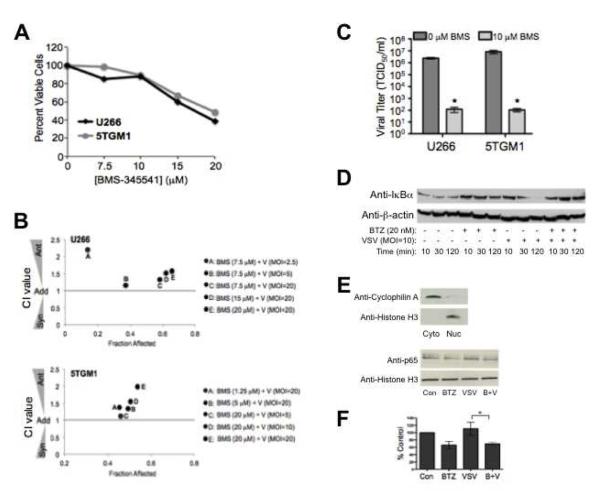

To delineate the role of NF-κB in the antagonism between VSV infection and bortezomib, we used an NF-κB-specific inhibitor in combination with VSV. BMS-345541 (BMS) blocks NF-κB activation by binding to the allosteric site of IKK, thus inhibiting the phosphorylation and subsequent proteasomal degradation of downstream IκBα [46]. First, U266 and 5TGM1 myeloma cells were treated with indicated doses of BMS-345541 alone. The cytotoxicity results, as determined by MTT analysis 24 hours post-treatment with indicated doses of BMS-345541, show that BMS-345541 by itself kills myeloma cells (Figure 3A). These results highlight the necessity of NF-κB activity for the survival of myeloma cells. Next, we simultaneously infected these myeloma cell lines with VSV-GFP and treated with BMS-345541. As shown in Figure 3B, the combination of VSV-GFP infection and specific inhibition of NF-κB by BMS-345541 results in antagonism, similar to the antagonism seen when VSV is combined with bortezomib (Figure 1). Additionally, an approximately 40-fold reduction in VSV viral titers is observed when BMS-345541 is added at the time of viral infection (MOI=0.01; Figure 3C).

Figure 3. Inhibition of NF-κB attenuates VSV replication in vitro.

(A) Cytotoxicity results determined by MTT analysis of U266 and 5TGM1 cells 24 hours post-BMS-345541 (BMS) treatment. (B) Combination index analysis of U266 and 5TGM1 cells following simultaneous treatment with VSV-GFP and BMS-34551. (C) Analysis of viral titer following simultaneous treatment with VSV-GFP (MOI=0.01) and BMS-345541. Samples were harvested 24 hours post-treatment. *p<0.05. (D) Western blot analysis of IκBα protein expression in U266 cells simultaneously treated with bortezomib and infected with VSV-GFP. Samples were harvested at indicated times and whole-cell lysates were analyzed. (E) Western blot analysis of p65 nuclear protein expression in U266 nuclear extracts harvested 5 hours post-infection/bortezomib treatment. Cytoplasmic (cyto) and nuclear (nuc) extracts were also probed for the cytoplasmic protein Cyclophilin A and the nuclear Histone H3 protein to determine the purity of the nuclear extracts. (F) Quantification of p65 Western blot data from three independent experiments using ImageJ software. The percent p65 relative to the control samples is shown. *p<0.05.

We next analyzed NF-κB activity in U266 cells infected with VSV-GFP in the presence or absence of bortezomib. As expected, proteasomal inhibition by bortezomib results in an accumulation of IκBα when compared to control-treated cells, because this protein can no longer be degraded by the proteasome (Figure 3D). In contrast, however, VSV-GFP infection results in IκBα degradation, demonstrating that VSV activates NF-κB in myeloma cells (Figure 3D). Importantly, as also shown in Figure 3D, bortezomib inhibits VSV-induced IκBα degradation. We also analyzed p65 (RelA) protein expression in the nucleus. As shown in Figure 3E, bortezomib reduces the level of nuclear p65 protein in U266 myeloma cells. Consistent with enhanced IκBα degradation following VSV-GFP expression (Figure 3D), bortezomib also attenuates nuclear p65 expression even in the presence of VSV-GFP (Figure 3E), and the difference in nuclear p65 protein levels between VSV alone and the combination of VSV plus bortezomib is statistically significant (Figure 3F). No difference in nuclear protein expression of the other NF-κB subunits (p50, p52, Rel B and c-rel) was seen when comparing VSV-GFP infected cells to cells treated with bortezomib and simultaneously infected with VSV-GFP at this time point (data not shown). Taken together, the results in Figure 3 demonstrate that NF-κB activity is crucial for robust VSV infection, and suggest that inhibition of NF-κB by bortezomib may play a role in the antagonism seen between VSV and bortezomib in myeloma cells.

BMS-345541 does not affect VSV viral titers in myeloma cells pre-treated with IFNβ

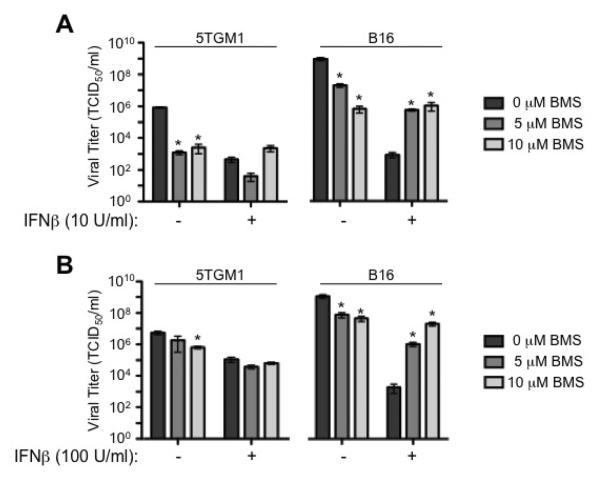

Contrary to our results showing antagonism between VSV infection and BMS-345541 treatment (Figure 3), others have reported synergy between these two agents [38]. Specifically, this group treated U87 glioma cells with IFN prior to VSV infection and found that, while IFN reduced viral titers by inducing an anti-viral state, treatment with BMS-345541 resulted in recovery of viral titer [38]. This viral titer recovery is likely through inhibition of NF-κB and consequent attenuation of the IFN-induced anti-viral state [38]. Because of the differing results seen in myeloma cells, we next analyzed the effect of BMS-345541 treatment on VSV viral titers in cells pre-treated with IFNβ. Notably, myeloma cells are known to be less responsive to the anti-viral effects of IFNβ than other cancer cells, including B16 melanoma cells [37]. Thus, we compared 5TGM1 murine myeloma cells to B16 murine melanoma cells pre-treated with murine IFNβ in the presence of absence of 5 or 10 μM BMS-345541 for 15 hours, then infected with VSV-GFP (and added BMS-345541 where appropriate). Samples were harvested 24 hours later and viral titers (TCID50/ml) were determined by plating serially diluted supernatants on BHK-21 cells. Cells were pre-treated with 10 U/ml or 100 U/ml IFNβ and infected with VSV-GFP at an MOI of 0.01 (Figure 4A) or 3 (Figure 4B), respectively. Similar to the results seen with myeloma cells (Figure 3C), BMS-345541 treatment alone reduced VSV titers in B16 cells (Figure 4). Also, as expected, pre-treatment of B16 cells with IFNβ reduced VSV-GFP titer (Figure 4), and this reduction in viral titer was greater than the reduction seen when cells are treated with BMS-345541 alone. However, viral titers were significantly increased when cells were treated with BMS-345541 at the time of IFNβ treatment, as compared to IFN pre-treatment and VSV infection without BMS-345541 (Figure 4). Corroborating the previously published data in U87 cells pre-treated with IFNα [38], similar results were also seen in U87 cells pre-treated with human IFNβ (data not shown). In contrast, 5TGM1 cells exhibit a modest response to IFNβ pre-treatment when compared to B16 cells, and the addition of BMS-345541 had no effect on VSV titer when cells were also treated with IFNβ (Figure 4). These results demonstrate that inhibition of NF-κB in certain cancers can enhance VSV titers via inhibition of the anti-viral state; myeloma cells, however, are less affected by the anti-viral effects of IFNβ and do not show an increase in viral titer in response to NF-κB inhibition.

Figure 4. VSV viral titer recovery by BMS-345541 in B16 melanoma but not 5TGM1 myeloma cells.

5TGM1 and B16 cells were pre-treated with indicated dose of interferon (IFN)-β for 15 hours +/− simultaneous treatment with BMS-345541, before VSV-GFP infection at (A) MOI=0.01 or (B) MOI=3. BMS-345541 was also added at time of infection. Samples were harvested 24 hours post-infection and viral titer determined on BHK cells. *p<0.05 when compared to cells without BMS-345541.

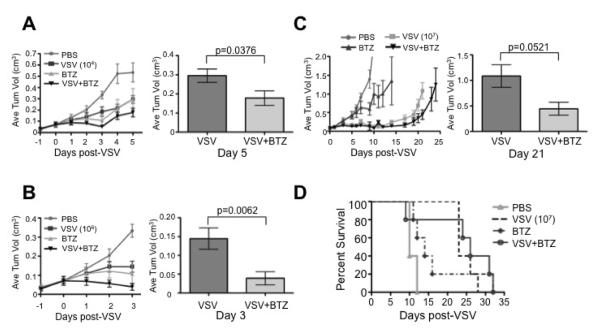

Bortezomib enhances VSV-induced tumor reduction in vivo

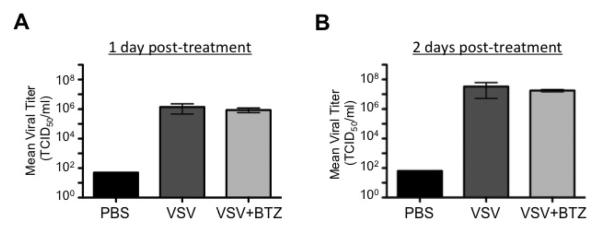

Having determined that VSV and bortezomib are antagonistic in vitro, we next wanted to evaluate if similar results would be seen in vivo, when myeloma cells are exposed to these agents in the presence of a fully-functioning immune system and their host environment. We first analyzed intra-tumoral VSV in the presence and absence of bortezomib, in a syngeneic, immunocompetent mouse myeloma model. MPC-11 cells were subcutaneously implanted into the right flank of BALB/c mice. Mice were then treated with a single IV dose of PBS or VSV-mIFN-NIS (1×106 TCID50) in the presence or absence of an intraperitoneal (IP) dose of bortezomib (1.0 mg/kg). Tumors were harvested 1 and 2 days post-treatment, VSV-N gene expression was analyzed by qPCR, and viral titers were determined based on a standard curve of known amounts of VSV-N RNA. Surprisingly, there was no difference in intra-tumoral VSV viral titers in mice treated with VSV-mIFN-NIS plus bortezomib compared to mice treated with VSV-mIFN-NIS alone (Figure 5A and 5B). These results, which differ from our in vitro data, indicate that bortezomib does not inhibit VSV replication in vivo.

Figure 5. Bortezomib does not inhibit intra-tumoral VSV replication in vivo.

MPC-11 tumors were harvested from BALB/c mice at (A) 1 and (B) 2 days post-virus/bortezomib treatment. Viral titers determined by q-PCR analysis of VSV-N gene and quantitated based on a standard curve are shown. Tumor samples from each mouse were run in triplicate (n=1 PBS mouse; n=3 mice in VSV and VSV+BTZ groups), and the mean viral titers were calculated from these mice. Error bars indicate standard error of the mean. There is no significant difference in mean viral titers between VSV and VSV+BTZ treated mice.

We next wanted to determine if bortezomib influenced VSV-induced tumor reduction in vivo. Again, the syngeneic BALB/c myeloma mouse model was used. 5×106 MPC-11 cells were implanted subcutaneously into the right flanks of BALB/c mice (6–9 mice/group), and mice were treated with a single intravenous dose of VSV-mIFN-NIS at 1×104 (Figure 6A) or 1×106 (Figure 7B) TCID50, with or without a single IP dose of bortezomib (1.0 mg/kg) when tumors reached a diameter of approximately 0.5 cm. The combination of VSV-mIFN-NIS (1×104 TCID50) plus bortezomib resulted in a significant decrease in tumor volume at day 5 post-treatment when compared to VSV-mIFN-NIS treatment alone (Figure 6A). Similar results were seen at 3 days post-treatment when mice were treated with a higher dose of VSV-mIFN-NIS (1×106 TCID50; Figure 6B). These results show that bortezomib significantly enhances VSV-induced tumor reduction in vivo. Unfortunately, we could not extend these results beyond the days shown because the BALB/c strain of mice is highly sensitive to the tumor-reducing effects of VSV-mIFN-NIS. These mice suffered from presumed rapid tumor lysis syndrome (blood chemistries revealed high levels of potassium and low calcium levels, and there was a distinctive softening of the tumors) and died within a week of virus administration, depending on the dose administered (data not shown). Notably, the death was not due to virus-induced toxicity, as mice without tumors were unaffected by virus treatment (data not shown).

Figure 6. Bortezomib enhances VSV-induced tumor oncolysis in vivo.

(A) MPC-11 cells were subcutaneously implanted into syngeneic BALB/c mice (n=6–9 mice/group). Mice were treated with 1×104 TCID50 VSV-mIFN-NIS (IV), bortezomib (1.0 mg/kg; IP), or the combination and tumors were measured daily. Average tumor volumes are shown. (B) Same as Figure 7A, except mice were treated with 1×106 TCID50 VSV-mIFN-NIS. (C) 5TGM1 murine myeloma cells were subcutaneously implanted into syngeneic C57BL/KaLwRij mice (n=5 mice/group). Mice were treated with VSV-mIFN-NIS (1×107 TCID50; IV), bortezomib (1.0 mg/kg; IP; 3X/week for 3 weeks) or the combination and tumors were measured daily. Average tumor volumes and (D) survival curves are shown.

Finally, we analyzed tumor reduction and survival in an in vivo syngeneic myeloma model that was less sensitive to the rapid reduction in tumor volume caused by VSV-mIFN-NIS treatment. 5×106 5TGM1 cells were subcutaneously implanted into the right flanks of C57BL/KaLwRij mice (5 mice/group). When tumors measured approximately 0.5 cm in diameter, mice were treated with a single IV dose of VSV-mIFN-NIS (1×107 TCID50), bortezomib (IP; 1.0 mg/kg; 3X/week for 3 weeks), or the combination of VSV-mIFN-NIS plus bortezomib. Average tumor volume (Figure 6C) and survival curves (Figure 6D) are shown. Although the average tumor volumes of mice treated with combination of VSV-mIFN-NIS plus bortezomib compared to VSV-mIFN-NIS treatment alone were not significantly different at 21 days post-VSV treatment (p=0.0521), there is a trend toward reduced tumor volume and enhanced survival with combination treatment.

In total, our in vivo data shows that bortezomib does not inhibit intra-tumoral VSV replication. Furthermore, the combination of VSV-mIFN-NIS plus bortezomib reduces myeloma tumor burden to a greater degree than VSV-mIFN-NIS alone.

Discussion

Bortezomib, a proteasome inhibitor approved for the treatment of multiple myeloma, has contributed to the enhanced survival of myeloma patients [19]. This disease remains incurable, however, with an overall median survival rate of approximately six years [21]. To this end, our lab and others have focused extensively on the utility of oncolytic viruses for the treatment of myeloma [23, 47]. Of the viruses studied, myeloma cells have proven to be exquisitely sensitive to the cancer-killing effects of vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV) [24, 25, 33, 37].

Since myeloma cells are highly sensitive to both bortezomib treatment and VSV-induced oncolysis, in this study we combined bortezomib and VSV. We hypothesized, that the combination of the two agents would result in enhanced cancer cell killing. Surprisingly, however, our in vitro data revealed that VSV and bortezomib are antagonistic in myeloma cell lines (Figure 1). Further, we show that bortezomib inhibits VSV replication and spread in vitro (Figure 2). Similarly, others have shown antagonism in vitro in other cell types as well. Specifically, Neznanov et al found that bortezomib inhibits VSV protein synthesis via stimulation of stress-related processes in HeLa cells [40], and Dudek et al reported that bortezomib activates NF-κB, resulting in an antiviral state that ultimately inhibits VSV propagation in A549 adenocarcinoma cells [39]. However, unlike the results reported by Dudek, we show that bortezomib does not activate but inhibits NF-κB in myeloma cells (Figure 3).

The cytotoxic effects of bortezomib in myeloma have been attributed in part to inhibition of NF-κB [15, 16]. The importance of NF-κB activity in myeloma cells following VSV infection, however, is unknown. In this report, we show that VSV infection induces IκBα degradation and enhances nuclear expression of the NF-κB subunit p65 (Figure 3), suggesting that NF-κB activation may be important for VSV infection of myeloma cells. Importantly, bortezomib inhibited VSV-induced IκBα degradation and attenuated nuclear p65 expression, further suggesting that NF-κB status may play a role in the antagonism seen between these two agents.

To delineate the role of NF-κB in the inhibition of VSV replication, we combined VSV with the NF-κB-specific inhibitor BMS-345541. This agent binds to the allosteric site of IKK, thus inhibiting the phosphorylation and subsequent proteasomal degradation of downstream IκBα [46]. We found that BMS-345541 and VSV are also antagonistic in myeloma, and that this agent inhibits VSV replication in these cells (Figure 3), indicating that NF-κB activity is necessary for robust VSV infection of myeloma cells in vitro. Jiang et al previously reported that VSV infection does not induce IκB phosphorylation in macrophages [48]. However, it is not surprising that myeloma cells, which are known to be addicted to NF-κB [11], and which require NF-κB activity for survival (Figure 3A), respond differently to VSV infection. Interestingly, different viruses modulate NF-κB activity in various ways. Some viruses, such as reoviruses and dengue virus, require NF-κB activation to induce apoptosis and promote rapid spread of the virus; conversely, viruses can also inhibit NF-κB to attenuate the host immune response [13]. Since VSV replicates and spreads so rapidly in myeloma cells, it is possible that VSV induction of NF-κB in these cells promotes NF-κB-induced apoptosis and allows for rapid spread of the virus and destruction of tumor cells. Thus, when NF-κB is inhibited by sub-lethal doses of bortezomib or BMS-345541, apoptosis is not induced as rapidly and the virus can't spread as quickly and efficiently. Alternatively, activation of NF-κB following VSV infection may serve as a survival signal, providing a healthy host environment within which VSV can rapidly replicate. If this is the case, then damaging the myeloma cells with bortezomib likely leads to an unhealthy host environment that is not conducive to viral replication. This second postulation is supported by Neznanov's report showing that bortezomib induces a stress-response that inhibits VSV replication in HeLa cells [40].

Since NF-κB is constitutively activated and thus dysregulated in myeloma cells, it is likely that the typical anti-viral response induced by NF-κB-activated IFN signaling is also aberrant in myeloma cells. In fact, we have shown that myeloma cells are far less responsive to the anti-viral effects of IFN pre-treatment than even other cancer cells [37]. To this end, we pre-treated B16 melanoma cells and 5TGM1 myeloma cells with IFN-β in the presence or absence of BMS-345541 to study the effects of NF-κB inhibition on the anti-viral response. Similar to previously published results in U87 glioma cells pre-treated with IFN-α [38], BMS-345541 significantly enhanced VSV viral titers in IFN-β pre-treated cells (Figure 4), likely through inhibition of the anti-viral state induced by NF-κB. In contrast, however, 5TGM1 myeloma cells were far less affected by the anti-viral effects of IFN-β pre-treatment than the B16 melanoma cells (Figure 4B). Furthermore, inhibition of NF-κB by BMS-345541 at the time of IFN-β treatment did not enhance or alter VSV viral titers in 5TGM1 myeloma cells (Figure 4), suggesting that NF-κB plays a role in the aberrant IFN signaling of myeloma cells.

We next wanted to determine the anti-myeloma effects of the combination of VSV and bortezomib in the context of the host environment. As such, we used two syngeneic, immunocompetent mouse myeloma models. MPC-11 myeloma cells were subcutaneously implanted into BALB/c mice. Surprisingly, the combination of VSV plus bortezomib resulted in a significantly reduced tumor size compared to the tumor size measured in mice treated with single-agent VSV (Figure 6A and 6B). Importantly, and in contrast to the in vitro data, bortezomib did not reduce intra-tumoral VSV titers (Figure 5). Unfortunately, however, these mice suffered from rapid tumor lysis syndrome, making it impossible to collect long-term survival data in these mice. Therefore, we also analyzed tumor response in the syngeneic C57BL/KaLwRij mice. In this model we observed a moderate decrease in tumor size with combination treatment compared to VSV treatment alone (Figure 6C). This decrease in size was not significant at 21 days post-VSV treatment (p=0.0521), however, likely due to the small the small sample size (n=5 VSV-treated mice compared to n=4 surviving VSV+BTZ-treated mice at day 21). Similarly, a trend toward improved survival is seen in combination-treated mice compared to VSV-treated mice (Figure 6D), and a larger sample size is necessary to verify if survival is indeed enhanced with the combination of VSV plus bortezomib. Also, varying the timing and dose of VSV and bortezomib to determine the optimal regimen will be important in vivo.

Although our in vitro data showed antagonism between VSV and bortezomib in myeloma cell lines, enhanced tumor reduction is seen in vivo with these two agents, compared to VSV therapy alone. Others have also reported that the oncolytic activity of a virus in vitro may not predict its anti-tumor effect in vivo. For example, oncolytic myxoma virus is able to target acute myeloid leukemia cells in vivo even though these cells are not permissive to myxoma infection in vitro [49]. The differing results seen in the present study are likely explained by the fact that myeloma cells respond differently when they are in isolation versus in the context of their immunocompetent host environment. For example, we previously reported enhanced survival in myeloma-bearing mice treated with VSV expressing murine IFNβ (VSV-mIFN) as compared to mice treated with VSV engineered to express human IFNβ (VSV-hIFN) [33]. Importantly, human IFNβ does not induce IFN signaling in murine cells and vice versa, so hIFNβ is not functional in mice. Therefore, the enhanced survival seen with the addition of mIFNβ is presumably due to an IFNβ–induced anti-tumor immune response in vivo. Along these lines, we have also reported that eradication of myeloma cells in vivo is mediated in part by an antitumor T-cell response [37]. Similarly, bortezomib has been shown to induce immune-mediated anti-tumor effects in an ovarian tumor mouse model, where a CD8+ T cell-mediated inhibition of tumor growth was observed following bortezomib treatment [50]. Thus, the enhanced tumor reduction seen with combination bortezomib plus VSV treatment in mice is likely due to the presence of immune cells that are not available when cells are grown in isolation in vitro.

In summary, we show that VSV and bortezomib are antagonistic in myeloma cells in vitro, and that bortezomib inhibits VSV replication and spread. In vivo, however, we report that bortezomib does not affect intra-tumoral VSV replication and that bortezomib enhances VSV-induced tumor regression. To our knowledge, these are the first studies analyzing the combination of VSV and bortezomib in vivo. Currently, studies are underway to determine the optimal timing and dose of these two agents in combination with one another to further enhance tumor regression and improve survival. The in vivo data provide a rationale for combining VSV and bortezomib in the clinic to treat myeloma patients.

Acknowledgments

Support and Financial Disclosure Declaration

This work was supported by NIH grant CA100634 (S.J.R.) and Clinical Pharmacology Training Grant T32 GM08685 (D.N.Y.).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

No financial interest/relationships with financial interest relating to the topic of this article have been declared.

References

- [1].Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, et al. Cancer statistics, 2008. CA Cancer J Clin. 2008;58:71–96. doi: 10.3322/CA.2007.0010. doi: 10.3322/CA.2007.0010. Epub 2008 Feb 3320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Kyle RA, Rajkumar SV. Multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1860–1873. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra041875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Laubach JP, Mitsiades CS, Mahindra A, et al. Novel therapies in the treatment of multiple myeloma. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2009;7:947–960. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2009.0062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Zhou Y, Barlogie B, Shaughnessy JD., Jr. The molecular characterization and clinical management of multiple myeloma in the post-genome era. Leukemia. 2009;23:1941–1956. doi: 10.1038/leu.2009.160. doi: 1910.1038/leu.2009.1160. Epub 2009 Aug 1946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Annunziata CM, Davis RE, Demchenko Y, et al. Frequent engagement of the classical and alternative NF-kappaB pathways by diverse genetic abnormalities in multiple myeloma. Cancer Cell. 2007;12:115–130. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Keats JJ, Fonseca R, Chesi M, et al. Promiscuous mutations activate the noncanonical NF-kappaB pathway in multiple myeloma. Cancer Cell. 2007;12:131–144. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Cusack JC, Liu R, Baldwin AS. NF- kappa B and chemoresistance: potentiation of cancer drugs via inhibition of NF- kappa B. Drug Resist Updat. 1999;2:271–273. doi: 10.1054/drup.1999.0094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Feinman R, Koury J, Thames M, Barlogie B, Epstein J, Siegel DS. Role of NF-kappaB in the rescue of multiple myeloma cells from glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis by bcl-2. Blood. 1999;93:3044–3052. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Yang HH, Ma MH, Vescio RA, Berenson JR. Overcoming drug resistance in multiple myeloma: the emergence of therapeutic approaches to induce apoptosis. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:4239–4247. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Baud V, Karin M. Is NF-kappaB a good target for cancer therapy? Hopes and pitfalls. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2009;8:33–40. doi: 10.1038/nrd2781. doi: 10.1038/nrd2781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Chaturvedi MM, Sung B, Yadav VR, Kannappan R, Aggarwal BB. NF-kappaB addiction and its role in cancer: 'one size does not fit all'. Oncogene. 2011;30:1615–1630. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.566. doi: 1610.1038/onc.2010.1566. Epub 2010 Dec 1620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Katze MG, Fornek JL, Palermo RE, Walters KA, Korth MJ. Innate immune modulation by RNA viruses: emerging insights from functional genomics. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8:644–654. doi: 10.1038/nri2377. doi: 610.1038/nri2377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Rahman MM, McFadden G. Modulation of NF-kappaB signalling by microbial pathogens. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2011;9:291–306. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2539. doi: 210.1038/nrmicro2539. Epub 2011 Mar 1038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Li ZW, Chen H, Campbell RA, Bonavida B, Berenson JR. NF-kappaB in the pathogenesis and treatment of multiple myeloma. Curr Opin Hematol. 2008;15:391–399. doi: 10.1097/MOH.0b013e328302c7f4. doi: 310.1097/MOH.1090b1013e328302c328307f328304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Ma MH, Yang HH, Parker K, et al. The proteasome inhibitor PS-341 markedly enhances sensitivity of multiple myeloma tumor cells to chemotherapeutic agents. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:1136–1144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Mitsiades N, Mitsiades CS, Poulaki V, et al. Molecular sequelae of proteasome inhibition in human multiple myeloma cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:14374–14379. doi: 10.1073/pnas.202445099. Epub 12002 Oct 14321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Edwards CM, Lwin ST, Fowler JA, et al. Myeloma cells exhibit an increase in proteasome activity and an enhanced response to proteasome inhibition in the bone marrow microenvironment in vivo. Am J Hematol. 2009;84:268–272. doi: 10.1002/ajh.21374. doi: 210.1002/ajh.21374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Hideshima T, Mitsiades C, Akiyama M, et al. Molecular mechanisms mediating antimyeloma activity of proteasome inhibitor PS-341. Blood. 2003;101:1530–1534. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-08-2543. Epub 2002 Sep 1526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Moreau P, Richardson PG, Cavo M, et al. Proteasome inhibitors in multiple myeloma: 10 years later. Blood. 2012;120:947–959. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-04-403733. doi: 910.1182/blood-2012-1104-403733. Epub 402012 May 403729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Kapoor P, Ramakrishnan V, Rajkumar SV. Bortezomib combination therapy in multiple myeloma. Semin Hematol. 2012;49:228–242. doi: 10.1053/j.seminhematol.2012.04.010. doi: 210.1053/j.seminhematol.2012.1004.1010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Mahindra A, Laubach J, Raje N, Munshi N, Richardson PG, Anderson K. Latest advances and current challenges in the treatment of multiple myeloma. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2012;9:135–143. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2012.15. doi: 110.1038/nrclinonc.2012.1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Parato KA, Senger D, Forsyth PA, Bell JC. Recent progress in the battle between oncolytic viruses and tumours. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5:965–976. doi: 10.1038/nrc1750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Russell SJ, Peng KW, Bell JC. Oncolytic virotherapy. Nat Biotechnol. 2012;30:658–670. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2287. doi: 610.1038/nbt.2287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Barber GN. Vesicular stomatitis virus as an oncolytic vector. Viral Immunol. 2004;17:516–527. doi: 10.1089/vim.2004.17.516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Lichty BD, Stojdl DF, Taylor RA, et al. Vesicular stomatitis virus: a potential therapeutic virus for the treatment of hematologic malignancy. Hum Gene Ther. 2004;15:821–831. doi: 10.1089/hum.2004.15.821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Assenberg R, Delmas O, Morin B, et al. Genomics and structure/function studies of Rhabdoviridae proteins involved in replication and transcription. Antiviral Res. 2010;87:149–161. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2010.02.322. doi: 110.1016/j.antiviral.2010.1002.1322. Epub 2010 Feb 1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Barber GN. VSV-tumor selective replication and protein translation. Oncogene. 2005;24:7710–7719. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Johnson JE, Nasar F, Coleman JW, et al. Neurovirulence properties of recombinant vesicular stomatitis virus vectors in non-human primates. Virology. 2007;360:36–49. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2006.10.026. Epub 2006 Nov 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Rodriguez LL. Emergence and re-emergence of vesicular stomatitis in the United States. Virus Res. 2002;85:211–219. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1702(02)00026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Stark GR, Kerr IM, Williams BR, Silverman RH, Schreiber RD. How cells respond to interferons. Annu Rev Biochem. 1998;67:227–264. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.67.1.227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Stojdl DF, Lichty B, Knowles S, et al. Exploiting tumor-specific defects in the interferon pathway with a previously unknown oncolytic virus. Nat Med. 2000;6:821–825. doi: 10.1038/77558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Stojdl DF, Lichty BD, tenOever BR, et al. VSV strains with defects in their ability to shutdown innate immunity are potent systemic anti-cancer agents. Cancer Cell. 2003;4:263–275. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00241-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Naik S, Nace R, Barber GN, Russell SJ. Potent systemic therapy of multiple myeloma utilizing oncolytic vesicular stomatitis virus coding for interferon-beta. Cancer Gene Ther. 2012;19:443–450. doi: 10.1038/cgt.2012.14. doi: 410.1038/cgt.2012.1014. Epub 2012 Apr 1020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Obuchi M, Fernandez M, Barber GN. Development of recombinant vesicular stomatitis viruses that exploit defects in host defense to augment specific oncolytic activity. J Virol. 2003;77:8843–8856. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.16.8843-8856.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Saloura V, Wang LC, Fridlender ZG, et al. Evaluation of an attenuated vesicular stomatitis virus vector expressing interferon-beta for use in malignant pleural mesothelioma: heterogeneity in interferon responsiveness defines potential efficacy. Hum Gene Ther. 2010;21:51–64. doi: 10.1089/hum.2009.088. doi: 10.1089/hum.2009.1088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Willmon CL, Saloura V, Fridlender ZG, et al. Expression of IFN-beta enhances both efficacy and safety of oncolytic vesicular stomatitis virus for therapy of mesothelioma. Cancer Res. 2009;69:7713–7720. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-1013. doi: 7710.1158/0008-5472.CAN-7709-1013. Epub 2009 Sep 7722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Naik S, Nace R, Federspiel MJ, Barber GN, Peng KW, Russell SJ. Curative one-shot systemic virotherapy in murine myeloma. Leukemia. 2012;26:1870–1878. doi: 10.1038/leu.2012.70. doi: 1810.1038/leu.2012.1870. Epub 2012 Mar 1819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Du Z, Whitt MA, Baumann J, et al. Inhibition of type I interferon-mediated antiviral action in human glioma cells by the IKK inhibitors BMS-345541 and TPCA-1. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2012;32:368–377. doi: 10.1089/jir.2012.0002. doi: 310.1089/jir.2012.0002. Epub 2012 Apr 1017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Dudek SE, Luig C, Pauli EK, Schubert U, Ludwig S. The clinically approved proteasome inhibitor PS-341 efficiently blocks influenza A virus and vesicular stomatitis virus propagation by establishing an antiviral state. J Virol. 2010;84:9439–9451. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00533-10. doi: 9410.1128/JVI.00533-00510. Epub 02010 Jun 00530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Neznanov N, Dragunsky EM, Chumakov KM, et al. Different effect of proteasome inhibition on vesicular stomatitis virus and poliovirus replication. PLoS One. 2008;3:e1887. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001887. doi: 1810.1371/journal.pone.0001887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Goel A, Dispenzieri A, Greipp PR, Witzig TE, Mesa RA, Russell SJ. PS-341-mediated selective targeting of multiple myeloma cells by synergistic increase in ionizing radiation-induced apoptosis. Exp Hematol. 2005;33:784–795. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2005.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Chou TC, Talalay P. Quantitative analysis of dose-effect relationships: the combined effects of multiple drugs or enzyme inhibitors. Adv Enzyme Regul. 1984;22:27–55. doi: 10.1016/0065-2571(84)90007-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Adams J. Proteasome inhibition in cancer: development of PS-341. Semin Oncol. 2001;28:613–619. doi: 10.1016/s0093-7754(01)90034-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].LeBlanc R, Catley LP, Hideshima T, et al. Proteasome inhibitor PS-341 inhibits human myeloma cell growth in vivo and prolongs survival in a murine model. Cancer Res. 2002;62:4996–5000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Mitsiades N, Mitsiades CS, Poulaki V, et al. Biologic sequelae of nuclear factor-kappaB blockade in multiple myeloma: therapeutic applications. Blood. 2002;99:4079–4086. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.11.4079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Burke JR, Pattoli MA, Gregor KR, et al. BMS-345541 is a highly selective inhibitor of I kappa B kinase that binds at an allosteric site of the enzyme and blocks NF-kappa B-dependent transcription in mice. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:1450–1456. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209677200. Epub 2002 Oct 1425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Russell SJ, Peng KW. Viruses as anticancer drugs. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2007;28:326–333. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2007.05.005. Epub 2007 Jun 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Jiang Z, Georgel P, Du X, et al. CD14 is required for MyD88-independent LPS signaling. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:565–570. doi: 10.1038/ni1207. Epub 2005 May 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Madlambayan GJ, Bartee E, Kim M, et al. Acute myeloid leukemia targeting by myxoma virus in vivo depends on cell binding but not permissiveness to infection in vitro. Leuk Res. 2012;36:619–624. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2012.01.020. doi: 610.1016/j.leukres.2012.1001.1020. Epub 2012 Feb 1017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Chang CL, Hsu YT, Wu CC, et al. Immune mechanism of the antitumor effects generated by bortezomib. J Immunol. 2012;189:3209–3220. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1103826. doi: 3210.4049/jimmunol.1103826. Epub 1102012 Aug 1103815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]