Abstract

Elevated rates of borderline personality disorder (BPD) have been found among individuals with substance use disorders (SUDs), especially cocaine-dependent patients. Evidence suggests that cocaine-dependent patients with BPD are at greater risk for negative clinical outcomes than cocaine-dependent patients without BPD and BPD-SUD patients dependent on other substances. Despite evidence that cocaine-dependent patients with BPD may be at particularly high risk for negative SUD outcomes, the mechanisms underlying this risk remain unclear. The present study sought to address this gap in the literature by examining cocaine-related attentional biases among cocaine-dependent patients with (n = 22) and without (n = 36) BPD. On separate days, participants listened to both a neutral and a personally-relevant emotionally evocative (i.e., trauma-related) script and then completed a dot-probe task with cocaine-related stimuli. Findings revealed a greater bias for attending to cocaine-related stimuli among male cocaine-dependent patients with (vs. without) BPD following the emotionally evocative script. Study findings suggest the possibility that cocaine use may have gender-specific functions among SUD patients with BPD, with men with BPD being more likely to use cocaine to decrease contextually induced emotional distress. The implications of our findings for informing future research on cocaine use among patients with BPD are discussed.

Keywords: Attentional bias, borderline personality disorder, substance use disorder, cocaine

1. Introduction

Borderline personality disorder (BPD) is a serious mental health condition characterized by a pervasive pattern of emotion dysregulation, interpersonal difficulties, and impulsive and self-destructive behaviors [1]. BPD is associated with severe functional impairment, high rates of co-occurring psychiatric disorders, and substantial economic, societal, and personal costs [2, 3]. BPD affects 1–6% of the general population [4]; however, individuals with BPD are major consumers of healthcare resources [5] and represent approximately 15% of clinical populations [2]. Rates of BPD have been found to be particularly high among individuals with substance use disorders (SUDs). Indeed, reported rates of co-occurring BPD among substance users generally range from 10% to 50%, with an average rate of 19% [6]. This particular co-occurrence also has great clinical relevance, as the presence of BPD among SUD patients is associated with a wide range of negative SUD outcomes, including more severe substance use and greater likelihood of overdose [7], quicker relapse to substance use following SUD treatment [8], and greater risk for SUD treatment dropout [7, 9, 10].

BPD is particularly common among cocaine-dependent patients. Rates of BPD exceed 30% among cocaine-dependent patients in residential SUD treatment [11], and are higher among cocaine-dependent patients than other SUD patients [12–15]. Moreover, there is some evidence to suggest that cocaine-dependent patients with BPD are at greater risk for negative clinical outcomes than cocaine-dependent patients without BPD and BPD-SUD patients dependent on other substances [13, 15].

Despite evidence that cocaine-dependent patients with BPD may be at particularly high risk for negative SUD outcomes, the mechanisms underlying this risk remain unclear. One potential mechanism that warrants consideration is cocaine-related attentional biases. The extant literature suggests heightened biases for processing substance-related information among individuals with (vs. without) SUDs. Numerous studies have found evidence of alcohol- and drug-related attentional biases among substance dependent individuals in general [for a review, see 16], as well as cocaine-dependent patients in particular [17, 18]. Such drug-related attentional biases are theorized to maintain and exacerbate SUDs, with prolonged attentional engagement with substance-related stimuli thought to increase substance saliency and result in increased cravings for, and subsequent use of, substances [19].

Indeed, research suggests that attentional bias to drug-related cues is associated with heightened cravings for and greater use of substances [19, 20]. Attentional bias for cocaine-related cues in particular has been found to be associated with cocaine use, risk of relapse, and poor treatment outcomes among cocaine-dependent patients [21–24]. Moreover, although no studies have examined cocaine-related attentional biases in cocaine-dependent patients with BPD, there is evidence to suggest that these biases may be greater among cocaine-dependent patients with BPD, particularly in the context of emotional distress. Specifically, negative reinforcement models of substance dependence assert the central role of negative reinforcement in the development of addiction, with substance use theorized to be reinforced by the decrease in emotional distress that follows this behavior [25, 26]. Consistent with theories that emphasize the emotion-regulating function of substance use in BPD [27, 28], research suggests that SUD patients with BPD may be particularly prone to use substances to regulate or escape emotional distress [6]. Indeed, many of the maladaptive behaviors common among individuals with BPD, including substance abuse, are theorized to stem from emotion dysregulation, functioning to alleviate or avoid emotional distress perceived as intolerable [29].

Consistent with a model wherein substance use in BPD serves to regulate emotions, preliminary research suggests that SUD patients with co-occurring BPD report greater substance cravings and use in response to negative emotional states than those without BPD [30]. Together with findings of heightened emotion dysregulation and emotional vulnerability in SUD patients with (vs. without) BPD [12, 31], these findings suggest that SUD patients with BPD may be particularly motivated to use cocaine to alleviate emotional distress. As cocaine is used repeatedly to avoid or escape emotional distress, cocaine-related cues may gain motivational significance due to their ability to predict reward (i.e., emotional relief), increasing the likelihood that attention will be biased toward such cues [32], particularly in the context of emotional distress [33–35].

To date, no published research has examined substance-related attentional biases in BPD. Thus, the present study sought to examine attentional biases for cocaine-related stimuli among cocaine-dependent patients with and without BPD following exposure to a personally-relevant emotionally-evocative cue (relative to a neutral cue). In particular, given evidence of heightened rates (i.e., > 90%) of traumatic exposure among both individuals with SUDs [36, 37], including cocaine-dependent patients in particular, [38, 39] and those with BPD [40], we utilized a personalized trauma script for the emotionally-evocative cue. Notably, past research provides support for the validity of this approach in evoking emotional distress among individuals with BPD [41], and those with a history of traumatic exposure [42, 43], including SUD patients [44, 45]. We hypothesized that cocaine-dependent patients with (vs. without) BPD would evidence a greater attentional bias for cocaine-related stimuli specifically in the context of emotional distress (i.e., following the emotionally-evocative cue).

Additionally, we sought to explore the moderating role of gender in this relation. Although recent findings indicate comparable rates of BPD among women and men [46, 47], evidence has been provided for gender differences in BPD-SUD comorbidity [48]. Specifically, men with BPD are more likely to be diagnosed with a co-occurring SUD than women with BPD [48, 49]. This difference may be understood in the context of a gender role theory of emotion regulation [50], which suggests that men are more likely to use externalizing behaviors (e.g., substance use) to regulate negative emotions, whereas women are more likely to use internalizing behaviors. Indeed, Zanarini et al. [51] described gender differences in co-occurring Axis I pathology in those with BPD as differences “in the type of disorder of impulse” (p. 1738), with men with BPD being significantly more likely to be diagnosed with SUDs and women with BPD being significantly more likely to be diagnosed with an eating disorder [51]. Thus, given that men with BPD may be more likely to rely on substance use as a way of managing emotional distress, we hypothesized that male patients with BPD would exhibit a greater attentional bias for cocaine-related stimuli than female patients with BPD (and SUD patients without BPD), particularly following exposure to an emotionally distressing cue.

2. Method

2.1. Participants

Participants were 60 cocaine-dependent patients consecutively admitted to a community-based residential SUD treatment facility in Washington, DC. To be eligible for the present study, participants had to (a) meet criteria for a diagnosis of cocaine dependence as defined by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition [1], (b) have experienced a Criterion A traumatic event [1], and (c) have no current psychosis or cognitive impairment (scores ≥ 24 on the Mini-Mental Status Examination [52]). Two cases that were identified as having undue influence on the primary analytic model (i.e., multivariate outliers defined as > 1 DFFITSi [53]) were removed from the sample. The final sample (N = 58; 26 women) had an average age of 44.5 years (SD = 6.6). The majority of participants self-identified as Black/African-American (97%) and 18 participants (31%) reported the use of psychotropic medications.

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Interview Measures

The BPD module of the Diagnostic Interview for DSM-IV Personality Disorders (DIPD-IV [54]) was administered to all participants by trained interviewers. The DIPD-IV has demonstrated adequate psychometric properties, including excellent retest and interrater reliability [55]. Each DSM-IV criterion for BPD is assessed through the use of one or more questions which are rated on a 3-point scale (0 = not present, 1 = subthreshold, and 2 = present). Consistent with the DSM-IV, participants who had a score of two on at least five of nine of the BPD criterion were assigned to the BPD group.

2.2.2. Self-report Measures

The Life Events Checklist (LEC [56]) is a self-report measure that provides participants with a list of 17 potentially traumatic events (e.g., motor vehicle accident, sexual assault, combat exposure). Participants were asked to identify their degree of exposure to each event, as well as the event that causes them the most distress currently. Each participant’s most distressing event was then used to develop a personalized trauma script (see below).

The PTSD Checklist – Civilian Version (PCL-C [57]) is a 17-item questionnaire designed to assess DSM-IV PTSD criteria in a civilian population. Participants were instructed to indicate the extent to which they experienced each symptom in the past month in relation to the traumatic event they identified as most distressing on the LEC. Response options are rated on a 5-point scale (1 = not at all to 5 = extremely). The PCL-C has demonstrated adequate psychometric properties, including high internal consistency and retest reliability [58], and convergent validity with other common PTSD symptom measures [59]. The PCL-C total score was used as a covariate in study analyses. In the present sample, internal consistency of the PCL-C total score was adequate (α = .95).

The 21-item version of the Depression, Anxiety, Stress Scales (DASS-21 [60]) is a brief measure of the unique symptoms of depression (e.g., I felt that life was meaningless), anxiety (e.g., I felt I was close to panic), and stress (e.g., I found it hard to wind down). Each subscale consists of 7 items. The DASS-21 has demonstrated adequate psychometric properties, including reliability and convergent and discriminant validity [61, 62]. The DASS-21 Anxiety and Depression subscales were used as covariates in primary analyses. The internal consistency of the DASS-21 Anxiety and Depression subscales was adequate (α = .87 and .90, respectively).

The Drug Use Questionnaire is a 13-item measure modeled after the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT [63]), and was designed to assess substance use frequency in the past year. Participants rate the frequency of use of 13 different substances (e.g., cocaine, alcohol, cannabis, stimulants) on a 6-point scale (0 = never to 5 = four or more times a week). A total score was calculated and used to account for past year substance use severity in primary analyses.

The Negative Affect (NA) subscale of the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS [64]) was used to assess NA at baseline and following the neutral and trauma cues. Specifically, participants were asked to rate the extent to which they were currently (“right now, at this very moment”) experiencing 10 forms of NA on a scale from 1 (very slightly or not at all) to 5 (extremely). This scale was administered to participants during each experimental session both before and after the trauma and neutral scripts (see below). The PANAS-NA subscale has exhibited adequate psychometric properties in prior studies [64], and the internal consistencies of all PANAS-NA scales used in the present study were adequate (α’s ranging from .82 to .93).

2.2.3. Trauma and Neutral Scripts

Consistent with procedures outlined by Lang and colleagues [65, 66], a personalized trauma script was generated based on responses to questions about each participant’s LEC-identified most distressing event. This one-min script was audio recorded in second-person present tense, and was designed to be sensory-driven and emotionally evocative. In addition, consistent with Keane et al. [42], a nonidiographic one-min neutral script was developed in which a common morning routine (e.g., waking up, getting out of bed) was described.

2.2.4. Dot-probe Task

The dot-probe task, a stimulus-response task designed to measure attentional biases, was presented on a laptop computer using E-Prime 2.0 software (Psychology Software Tools, Pittsburgh, PA). The dot-probe task has been used to measure attentional biases related to a wide variety of psychopathology, including BPD [67, 68], substance use [69], and trauma-related symptoms [70]. In the present study, following the presentation of a fixation cross in the center of a computer screen for 500 ms, two stimuli were presented side by side. The stimuli remained on the screen for 500 ms, after which a dot appeared on the screen replacing one of the two pictures. The participant was instructed to press a button on the computer keyboard that corresponded to the relative position of the dot on the screen, thus providing a snapshot of attention allocation at that point in time. Following each button press, participants received visual feedback for 1500 ms in the form of response accuracy and reaction time information.

Stimuli consisted of 20 cocaine-related pictures (e.g., crack pipes, crack rocks), and 40 pictures of furniture. Participants completed five practice trials and 240 experimental trials. Of the 240 experimental trials, 80 consisted of neutral-neutral image pairings and 160 consisted of cocaine-neutral image pairings. The order of stimulus presentation was randomized across participants.

2.3. Procedure

The procedures for this study received institutional review board approval. In order to limit the impact of cocaine withdrawal on study findings, eligible participants had to wait a minimum of 72 hours from the time of facility admission before being eligible for recruitment into the present study. Following informed consent, participants completed an initial assessment session, during which the LEC was administered and participants described their target traumatic event in detail. Participants also completed a series of questionnaires, including the self-report measures previously described. Next, participants completed two experimental sessions which took place on separate days. All three sessions were completed in the first two weeks of treatment.

At each experimental session, participants rated their level of NA prior to and following script presentation. The order of script presentation (i.e., trauma, neutral) was counterbalanced across participants. After completing the PANAS-NA a second time, participants completed the dot-probe task. Participants received $10 reimbursement for each session. To ensure that participants did not leave the study in a state of heightened distress, study personnel had participants rate their level of distress at the start and end of each study session. If participants reported an increase in distress by greater than 2 points on an 11-point Likert scale (0 = no distress, 10 = extremely severe distress), they were taken through a series of emotion regulation skills (e.g., deep breathing, distraction) until their distress reduced to baseline levels. No participants left any of the study sessions with distress levels higher than those they reported at the beginning of the session.

2.4. Data Preparation

To reduce the effect of anticipatory responding and outliers in stimulus-response data, error responses (< 1%), RTs < 200ms, > 2000ms, and > 3 standard deviations above the mean response time for each trial were discarded [71]. An attentional bias score was calculated for each of the dot-probe tasks (post-trauma and post-neutral script) by subtracting mean latencies on trials where the probe occurred in the position of a cocaine image from mean latencies on trials where the probe occurred in the position of a neutral image in neutral-cocaine pairings [72]. Negative attentional bias scores indicated attention to neutral simuli and positive attentional bias scores indicated attention to cocaine stimuli. Attentional bias scores (i.e., post-neutral and post-trauma script) were not associated (r = −.03, p = .84).

2.5. Data Analytic Strategy

To ensure both that the trauma script elicited NA and that the change in levels of NA in response to the trauma and neutral scripts did not differ across groups, two 2 (BPD status) × 2 (gender) × 2 (pre- vs. post-script NA) repeated measures analyses of variance (ANOVA) were conducted for the trauma and neutral scripts. Likewise, to determine the effectiveness of counterbalancing the script presentation, we examined the order of script presentation as a predictor of post-neutral and post-trauma script attentional bias scores.

Prior to conducting primary analyses, we conducted correlation analyses to examine whether any demographic variables were significantly associated with our dependent variables (thus requiring inclusion in primary analyses as a covariate [73]). Race/ethnicity was not examined as a potential covariate due to limited variability (i.e., 97% of the sample identified as Black/African-American). Given evidence that patients with (vs. without) BPD exhibit higher rates of both Axis I disorders [74] and psychotropic medication use [75], we also included psychotropic medication use, substance use frequency, and depression, anxiety, and posttraumatic stress symptom severity as covariates in our primary analyses. Inclusion of these variables in our statistical models increases confidence that any significant findings may be attributed to the effects of BPD per se, rather than simply greater levels of psychopathology among SUD patients with (vs. without) BPD.

To test study hypotheses, a 2 (BPD status) × 2 (gender) × 2 (neutral vs. trauma script attentional bias) repeated measures ANCOVA (controlling for substance use frequency, age, psychotropic medication status, and anxiety, depression, and posttraumatic stress symptom severity) was conducted. In response to a significant three-way interaction, pairwise comparisons were conducted across two one-way (BPD men [n = 7] vs. BPD women [n = 15] vs. non-BPD men [n = 25] vs. non-BPD women [n = 11]) ANCOVAs (using the same covariates as above) with the post-trauma script and post-neutral script attentional bias scores serving as the dependent variables. Finally, to explore the nature of any between-group differences (and identify the particular group(s) evidencing an attentional bias [76], one-sample t-tests were conducted for each of the four groups to determine which group(s) had either post-trauma or post-neutral script attentional bias scores that were significantly different from zero.

3. Results

3.1. Preliminary Analyses

Participants reported experiencing an average of 5.48 (SD = 2.85) potentially traumatic events. Frequency counts for personalized trauma script content categories across BPD status and gender are provided in Table 1. There were no significant differences in target trauma type (i.e., interpersonal vs. non-interpersonal) between groups (χ2(3) = 4.46, p = .22).

Table 1.

Personalized Trauma Script Content by group status (BPD x Gender).

| Women | Men | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-BPD | BPD | Non-BPD | BPD | |

| Accident | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Assault (physical or weapon) | 5 | 5 | 9 | 2 |

| Sexual Assault | 3 | 4 | 1 | 0 |

| Death/Injury to Other | 1 | 3 | 9 | 5 |

| Othera | 1 | 2 | 5 | 0 |

Note. BPD = borderline personality disorder.

Other category includes fire, being held captive, fearing violence, and illness.

Providing support for the experimental manipulation, the trauma script resulted in significant increases in NA across all participants (F[1,57] = 37.14, p < .001; pre-script NA M = 14.74, SD = 6.25; post-script NA M = 21.55, SD = 10.67). Importantly, there were no between-group differences in changes in NA from pre- to post-trauma script (F[1,57] = .18, p = .68). Further, the neutral script resulted in a significant decrease in NA across all participants (F[1,57] = 16.09, p < .001; pre-script NA M = 15.30, SD = 5.87; post-script NA M = 13.58, SD = 5.55), and no between-group differences in changes in NA from pre- to post-neutral script were observed (F[1,57] = .98, p = .33). Moreover, providing support for the effectiveness of the counterbalancing, there were no differences in post-neutral (t[56] = .58, p = .56) and post-trauma script (t[56] = −1.32, p = .19) attentional bias scores based on the order of script presentation.

With regard to the identification of demographic covariates, age was positively associated with post-neutral script attentional bias, r = .24, p = .01. No other associations were significant. Table 2 presents descriptive statistics for all covariates included in the primary analyses.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics presented by group status (BPD x Gender).

| Women | Men | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-BPD | BPD | Non-BPD | BPD | |

| Age | 46.55(5.17) | 43.87(5.53) | 44.72(7.55) | 41.43(7.23) |

| Substance use severity | 12.37(4.18) | 15.13(7.43) | 16.68(9.37) | 15.29(6.85) |

| Medication | 0.27(0.47) | 0.60(0.51) | 0.20(0.41) | 0.14(0.38) |

| Anxiety | 16.36(9.91) | 14.93(12.67) | 7.20(8.35) | 14.00(11.66) |

| Depression | 13.27(9.52 | 14.40(11.50) | 10.08(9.12) | 20.00(11.94) |

| Posttraumatic stress | 43.36(16.07) | 46.35(17.73) | 33.08(13.20) | 37.29(15.54) |

Note. Means are followed by standard deviations in parentheses. BPD = borderline personality disorder; Medication = current psychotropic medication use (0 = no, 1 = yes).

3.2. Primary Analyses

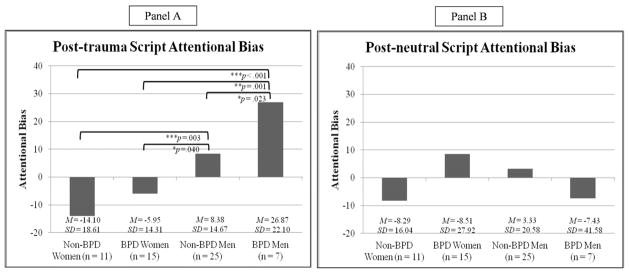

Of note, all assumptions for ANCOVA were met [73]. Results revealed that BPD status did not predict attentional bias for cocaine-related stimuli following the trauma script, relative to neutral script, (i.e., interaction between BPD and script type; F[1,48] = 1.39, p = .25, ηp2 = .03). However, as predicted, the three-way interaction between BPD status, gender, and script type (trauma vs. neutral) was significant (F[1,48] = 5.5, p = .02, ηp2 = .10). Follow-up pairwise comparisons revealed significant between-group differences in post-trauma script attentional bias scores, but not post-neutral script attentional bias scores (see Table 3). As shown in Figure 1, BPD men had significantly higher post-trauma script attentional bias scores than all other groups, ps < .05. In addition, non-BPD men had significantly higher post-trauma script attentional bias scores than both non-BPD and BPD women, ps < .05. Non-BPD and BPD women did not differ significantly in their post-trauma script attentional bias scores, p = .33. Notably, post-trauma script attentional bias scores differed significantly from zero only among men with BPD (t[6] = 3.18, p = .02); no evidence for post-trauma script attentional bias was found for any other group (all ts < 1.89, ps > .07). Likewise, none of the groups had post-neutral script attentional bias scores that were significantly different from zero.

Table 3.

ANCOVAs examining between-group (BPD men vs. BPD women vs. non-BPD men vs. non-BPD women) differences in post-trauma script and post-neutral script attentional bias scores.

| Trauma Script Attentional Bias | Neutral Script Attentional Bias | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| F(3,54) | p | ηp2 | F(3,54) | p | ηp2 | |

| Age | 0.84 | 0.365 | 0.02 | 6.05 | 0.018 | 0.11 |

| Substance | 0.02 | 0.884 | 0.00 | 0.18 | 0.678 | 0.00 |

| Medication | 0.20 | 0.655 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.964 | 0.00 |

| Anxiety | 2.45 | 0.124 | 0.05 | 1.96 | 0.168 | 0.04 |

| Depression | 1.67 | 0.203 | 0.03 | 1.29 | 0.261 | 0.03 |

| Posttraumatic stress | 1.88 | 0.177 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.830 | 0.00 |

| BPD/Gender Group | 8.56 | 0.000 | 0.35 | 1.22 | 0.312 | 0.07 |

Note. BPD = borderline personality disorder; Substance = substance use severity; Medication = current psychotropic medication use (0 = no, 1 = yes).

Figure 1.

Post-hoc pairwise comparisons of group status (BPD men, BPD women, non-BPD men, non-BPD women) predicting post-trauma (Panel A) and post-neutral script attentional bias scores.

*p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

4. Discussion

This is the first study to examine cocaine-related attentional biases among cocaine-dependent patients with BPD. Findings provided partial support for study hypotheses. Although cocaine-dependent patients with (vs. without) BPD did not evidence a greater attentional bias for cocaine-related stimuli following the emotionally-evocative cue as predicted, findings did provide support for the hypothesized moderating role of gender in this relation. Specifically, male cocaine-dependent patients with BPD showed a greater attentional bias for cocaine-related stimuli than female patients with BPD (and SUD patients without BPD) following exposure to the trauma script. Notably, not only did male patients with BPD exhibit a greater cocaine-related attentional bias following the trauma script, both female patients with BPD and female patients without BPD evidenced no cocaine-related attentional bias following either the neutral or trauma script. These findings suggest that cocaine use may have gender-specific functions among cocaine-dependent patients with BPD, with cocaine-dependent men with BPD being more likely to use cocaine to decrease contextually-induced emotional distress.

These findings are consistent with the gender role theory of emotion regulation [50], which suggests that men are more likely to use externalizing behaviors (e.g., substance use) to regulate negative emotions, whereas women are more likely to use internalizing behaviors. As described by Nolen-Hoeksema [50], gender divergence in the function of substance use may be the result of cultural indoctrination through which males are taught that the use of substances to relieve distress is more culturally appropriate than strategies that are deemed to be female in nature (e.g., emotional expression). Consistent with this proposition, evidence from the alcohol literature has shown that drinking and drunkenness are viewed as more socially acceptable for males than females [77] and adolescent females are more likely than males to be punished for alcohol use [for a review see 78]. Thus, over time, males may be more likely to associate substance-related cues with relief from emotional distress, resulting in an attentional bias toward such cues when distressed. As suggested by the findings of this study, this association may become particularly pronounced in cocaine-dependent men with (vs. without) BPD, due to the heightened emotional intensity, emotion dysregulation, and deficits in impulse control associated with this disorder [1].

The above rationale is consistent with findings from the present study; however, study findings do not suggest an explanation (e.g., negative reinforcement) for cocaine use in female patients with BPD. Although our findings may be interpreted as suggesting that cocaine-dependent women with BPD do not use cocaine specifically to regulate emotional distress, study methodology precludes conclusions regarding the function of substance use in these women. For example, it may be that cocaine-dependent women with BPD are more likely to use cocaine to increase positive affect than to reduce negative affect. Alternatively, cocaine-dependent women with BPD may be more likely to use cocaine in response to interpersonally-oriented (but not trauma-related) distress. In future research, the inclusion of a positive mood or interpersonally-oriented negative emotion induction would allow for an examination of cocaine-related attentional biases in the context of positive emotions or non-trauma related negative emotions among women with BPD.

In addition, it is important to note that our dot-probe task stimulus presentation duration (i.e., 500 ms) likely provided ample time for shifts in attention to occur [70, 79]. Therefore, whereas the results of this study suggest that male cocaine-dependent patients with BPD exhibited prolonged attentional engagment with cocaine-related cues following trauma script exposure, they do not speak to the initial orienting of attention to cocaine-related cues in this sample. It may be that cocaine-dependent individuals in general, or cocaine-dependent women with BPD more specifically, have faster orienting of attention to cocaine-related cues following trauma cue exposure. Thus, cocaine-dependent males with BPD may not have faster orienting of attention towards cocaine-related stimuli, but, instead, may exhibit difficulty disengaging from cocaine stimuli. The use of shorter dot-probe task presentation durations in future research may help to differentiate between the attentional processes responsible for this phenomenon (i.e., facilitated engagement, difficulty disengaging).

Of note, our findings revealed comparable levels of emotional reactivity to the trauma script across BPD and non-BPD participants. Although participants with BPD might be expected to evidence heightened reactivity to such an emotionally-evocative cue, the absence of between-group differences in reactivity to this cue is not without support in the literature. Specifically, this finding is consistent with mounting evidence that the emotional reactivity in BPD, rather than being a generalized vulnerability, is context-dependent and emotion-specific [80–82]. Moreover, given that all participants in this study had experienced a Criterion A traumatic event, the trauma script was expected to elicit NA among all participants, and was chosen as the experimental manipulation for this reason. Nonetheless, the absence of between-group differences in emotional reactivity to the trauma script combined with the finding that men with BPD exhibited a greater attentional bias to cocaine-related cues following trauma script presentation lends support to the idea that BPD is associated with difficulties down-regulating intense emotions that may increase the risk for engaging in maladaptive behaviors [83].

Additional limitations should be noted. First, the sample consisted of treatment-seeking cocaine-dependent patients, the majority of whom were African-Americans from an inner city residential SUD treatment facility. Thus, results of this study may not be generalizable to cocaine users in the general population or to individuals from other racial/ethnic backgrounds. In addition, our exclusive use of cocaine-related stimuli precludes generalization of our findings to substance use more generally. Inclusion of other types of drug- and alcohol-related stimuli in future research would be helpful in determining if the attentional processes observed in the present study are consistent across substances and types of substance-dependent groups. Further, based on existing empirical and theoretical literature [6], we are assuming that greater attentional bias to cocaine-related cues among cocaine-dependent men with BPD is driven by negative reinforcement motives. However, without actually assessing motives for cocaine use following trauma cue exposure or other potential mechanisms that may explain this association (e.g., impulsivity), we cannot conclude that negative reinforcement motives are driving our results. Future research incorporating the explicit assessment of cocaine use motives into the study design would help determine the extent to which negative-reinforcement motives underlie the attentional bias for cocaine-related cues in the context of intense negative emotions observed among cocaine-dependent patients with BPD.

Further, we did not assess for negative clinical outcomes in this study. Consequently, it is not clear if attentional bias to cocaine-related cues following trauma cue exposure is one mechanism that explains the worse clinical outcomes observed among cocaine-dependent patients with (vs. without) BPD. Prospective studies are needed to determine whether cocaine-related attentional biases among cocaine-dependent men with BPD may predict later treatment dropout, relapse, or other negative substance use outcomes. In addition, it is important to note that the interactive effect of gender and BPD status on cocaine-related attentional bias following trauma script exposure was not better accounted for by symptoms of depression, anxiety, posttraumatic stress, or substance use severity. Although this finding increases confidence in our results and provides some support for the robust nature of the observed relations, future studies should incorporate diagnostic interviews to assess for the full range of Axis I and II disorders to better account for the effect of these diagnoses in future research. Given increasing support for dimensional models of personality pathology, both in general [84] and with regard to BPD in particular [85, 86], replication of these findings using a dimensional measure of BPD pathology will also be important. Given our relatively small sample size, replication with a larger sample size is also recommended. Finally, given that this study was conducted as part of another study, we utilized personalized trauma scripts as our emotion induction procedure. This is not necessarily a limitation of the present study, as individuals with BPD tend to experience a relatively high level of traumatic life events (e.g., over 90% of individuals with BPD report experiencing at least one traumatic event in their lifetime [40]) and results were found despite accounting for the severity of PTSD symptoms (a disorder that commonly co-occurs with BPD [51]). Nonetheless, stronger relations or differences as a function of BPD status in female patients may have been found using an emotion induction procedure more specific to BPD. Specifically, future studies may benefit from the use of interpersonally-oriented emotion induction procedures [87], as studies have found that individuals with BPD are uniquely reactive to interpersonal stressors, evidencing greater autonomic and subjective emotional reactivity to interpersonal stressors (but not general negative emotional stimuli) than controls [82, 88]. Despite limitations, the present study represents a first step in examining substance-related attentional biases in individuals with co-occurring BPD-SUD, and findings underscore the importance of considering gender in identifying treatment targets for substance dependence among patients with BPD.

Acknowledgments

This paper is the result of work supported with resources and the use of facilities at the University of Mississippi Medical Center/G. V. (Sonny) Montgomery VA Medical Center, Jackson, MS. The views expressed here represent those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the University of Mississippi Medical Center or Department of Veterans Affairs.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. text revision. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Skodol AE, Gunderson JG, Pfohl B, Widiger TA, Livesley JW, Siever LJ. The borderline diagnosis I: Psychopathology, comorbidity, and personality structure. Society of Biological Psychiatry. 2002;51:936–950. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01324-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Van Asselt AD, Dirksen CD, Arntz A, Severens JL. The cost of borderline personality disorder: Societal cost of illness in BPD-patients. European Journal of Psychiatry. 2007;22:354–361. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2007.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lieb K, Zanarini MC, Schmahl C, Linehan MM, Bohus M. Borderline personality disorder. The Lancet. 2004;364:453–461. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16770-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zanarini MC, Frankenburg D, Reich DB, Fitzmaurice G. The 10-year course of psychosocial functioning among patients with borderline personality disorder and axis II comparison subjects. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2010;122:103–109. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2010.01543.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Trull TJ, Sher KJ, Minks-Brown C, Durbin J, Burr R. Borderline personality disorder and substance use disorders: A review and integration. Clinical Psychology Review. 2000;20:235–253. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(99)00028-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Darke S, Ross J, Williamson A, Teesson M. Borderline personality disorder and persistently elevated levels of risk in 36-month outcomes for the treatment of heroin dependence. Addiction. 2005;102:1140–1146. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.01876.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nace EP, Saxon JJ, Shore N. Borderline personality disorder and alcoholism treatment: A one-year follow-up study. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1986;47:196–200. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1986.47.196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Martínez-Raga J, Marshall E, Keaney F, Ball D, Strang J. Unplanned versus planned discharges from in-patient alcohol detoxification: Retrospective analysis of 470 first-episode admissions. Alcohol and Alcoholism. 2001;37:277–281. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/37.3.277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tull MT, Gratz KL. The impact of borderline personality disorder on residential substance abuse treatment dropout among men. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2012;121:97–102. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen KW, Banducci AN, Guller L, Macatee RJ, Lavelle A, Daughters SB, et al. An examination of psychiatric comorbidities as a function of gender and substance type within an inpatient substance use treatment program. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2011;118:92–99. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bornovalova MA, Gratz KL, Daughters SB, Nick B, Delany-Brumsey A, Lynch TR, et al. A multimodal assessment of the relationship between emotion dysregulation and borderline personality disorder among inner-city substance users in residential treatment. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2008;42:717–726. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2007.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Flynn PM, Luckey JW, Brown BS, Hoffman JA. Relationship between drug preference and indicators of psychiatric impairment. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 1995;21:153–166. doi: 10.3109/00952999509002685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee H, Bagge CL, Schumacher JA, Coffey SF. Does comorbid substance use disorder exacerbate borderline personality features? A comparison of borderline personality disorder individuals with vs. without current substance dependence. Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment. 2010;1:239–249. doi: 10.1037/a0017647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tull MT, Gratz KL, Weiss NH. Exploring associations between borderline personality disorder, crack/cocaine dependence, gender, and risky sexual behavior among substance-dependent inpatients. Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment. 2011;2:209–219. doi: 10.1037/a0021878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Field M, Cox WM. Attentional bias in addictive behaviors: A review of its development, causes, and consequences. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2008;97:1–20. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hester R, Dixon V, Garavan H. A consistent attentional bias for drug-related material in active cocaine users across word and picture versions of the emotional Stroop task. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2006;81:251–257. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu S, Lane SD, Schmitz JM, Waters AJ, Cunningham KA, Moeller FG. Relationship between attentional bias to cocaine-related stimuli and impulsivity in cocaine-dependent subjects. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2011;37:117–122. doi: 10.3109/00952990.2010.543204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Field M, Eastwood B. Experimental manipulation of attentional bias increases the motivation to drink alcohol. Psychopharmacology. 2005;183:350–357. doi: 10.1007/s00213-005-0202-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fadardi JS, Ziaee S, Shamloo ZS. Substance use and the paradox of good and bad attentional bias. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2009;17:456–463. doi: 10.1037/a0017294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carpenter KM, Martinez D, Vadhan NP, Barnes-Holmes D, Nunes EV. Measures of attentional bias and relational responding are associated with behavioral treatment outcome for cocaine dependence. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2012;38:146–154. doi: 10.3109/00952990.2011.643986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carpenter KM, Schreiber E, Church S, McDowell D. Drug Stroop performance: Relationships with primary substance of use and treatment outcome in a drug-dependent outpatient sample. Addictive Behaviors. 2006;31:174–181. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gardini S, Caffarra P, Venneri A. Decreased drug-cue-induced attentional bias in individuals with treated and untreated drug dependence. Acta Neuropsychiatrica. 2009;21:179–185. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-5215.2009.00389.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hester R, Garavan H. Neural mechanisms underlying drug-related cue distraction in active cocaine users. Pharmacology, Biochemistry, and Behavior. 2009;93:270–277. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2008.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Khantzian EJ. The self-medication hypothesis of substance use disorders: A reconsideration and recent applications. Harvard Review of Psychiatry. 1997;4:231–244. doi: 10.3109/10673229709030550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McCarthy DE, Curtin JJ, Piper ME, Baker TB. Negative reinforcement: Possible clinical implications of an integrative model. In: Kassel J, editor. Substance abuse and emotion. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2010. pp. 15–42. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Linehan MM, Dimeff LA, Reynolds SK, Comtois K, Welch S, Heagerty P, et al. Dialectical behavior therapy versus comprehensive validation therapy plus 12-step for the treatment of opioid dependent women meeting criteria for borderline personality disorder. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2002;67:13–26. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(02)00011-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Verheul R, van den Bosch LC, Ball SA. Substance abuse. In: Oldham JM, Skodol AE, Bender DS, editors. The American Psychiatric Publishing textbook of personality disorders. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc; 2005. pp. 463–75. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Linehan M. Cognitive–behavioral treatment of borderline personality disorder. New York: Guilford Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kruedelbach N, McCormick RA, Schulz SC, Grueneich R. Impulsivity, coping styles, and triggers for craving in substance abusers with borderline personality disorder. Journal of Personality Disorders. 1993;7:214–222. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gratz KL, Tull MT, Baruch DE, Bornovalova MA, Lejuez CW. Factors associated with co-occurring borderline personality disorder among inner-city substance users: The roles of childhood maltreatment, negative affect intensity/reactivity, and emotion dysregulation. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 2008;49:603–615. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2008.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Robinson TE, Berridge KC. The neural basis of drug craving: An incentive sensitization theory of addiction. Brain Research Reviews. 1993;18:247–291. doi: 10.1016/0165-0173(93)90013-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Baker TB, Piper ME, McCarthy DE, Majeskie MR, Fiore MC. Addiction motivation reformulated: An affective processing model of negative reinforcement. Psychological Review. 2004;111:33–51. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.111.1.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bradley BP, Garner M, Hudson L, Mogg K. Influence of negative affect on selective attention to smoking-related cues and urge to smoke in cigarette smokers. Behavioural Pharmacology. 2007;18:255–263. doi: 10.1097/FBP.0b013e328173969b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Field M, Powell H. Stress increases attentional bias for alcohol cues in social drinkers who drink to cope. Alcohol & Alcoholism. 2007;42:560–566. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agm064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brown PJ, Stout RL, Mueller T. Substance use disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder comorbidity: Addiction and psychiatric treatment rates. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 1999;13:115–122. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ford JD, Hawke J, Alessi S, Ledgerwood D, Petry N. Psychological trauma and PTSD symptoms as predictors of substance dependence treatment outcomes. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2007;45:2417–2431. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2007.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Afful SE, Strickland JR, Cottler L, Bierut LJ. Exposure to trauma: A comparison of cocaine-dependent cases and a community-matched sample. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2010;112:46–53. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Banducci AN, Dahne J, Magidson JF, Chen K, Daughters SB, Lejuez CW. Clinical characteristics as a function of referral status among substance users in residential treatment. Addictive Behaviors. 2013;38:1924–1930. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.12.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yen S, Shea MT, Battle CL, Johnson DM, Zlotnick C, Dolan-Sewell R, et al. Traumatic exposure and posttraumatic stress disorder in borderline, schizotypal, avoidant, and obsessive-compulsive personality disorders: Findings from the collaborative longitudinal personality disorders study. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2002;190:510–518. doi: 10.1097/00005053-200208000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schmahl CG, Elzinga BM, Ebner UW, Simms T, Sanislow C, Vermetten E, et al. Psychophysiological reactivity to traumatic and abandonment scripts in borderline personality and posttraumatic stress disorders: A preliminary report. Psychiatry Research. 2004;126:33–42. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2004.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Keane TM, Kolb LC, Kaloupek DG, Orr SP, Blanchard EB, Thomas RG, et al. Utility of psychophysiology measurement in the diagnosis of posttraumatic stress disorder: Results from a department of Veteran’s Affairs cooperative study. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1998;66:914–923. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.6.914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Orr SP, Roth WT. Psychophysiological assessment: Clinical applications for PTSD. Journal of affective Disorders. 2000;61:225–240. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(00)00340-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Coffey SC, Saladin ME, Drobes DJ, Brady KT, Dansky BS, Kilpatrick DG. Trauma and substance cue reactivity in individuals with comorbid posttraumatic stress disorder and cocaine or alcohol dependence. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2002;65:115–217. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(01)00157-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Saladin ME, Drobes DJ, Coffey SF, Dansky BS, Brady KT, Kilpatrick DG. PTSD symptom severity as a predictor of cue-elicited drug craving in victims of violent crime. Addictive Behaviors. 2003;28:1611–1629. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2003.08.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Grant BF, Chou SP, Goldstein RB, Huang B, Stinson FS, Saha TD, et al. Prevalence, correlates, disability, and comorbidity of DSM-IV borderline personality disorder: Results from the Wave 2 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Psychiatry: Interpersonal and Biological Processes. 2008;69:533–545. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v69n0404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lenzenweger MF, Lane MC, Loranger AW, Kessler RC. DSM-IV personality disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Biological Psychiatry. 2007;62:553–564. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.09.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Johnson DM, Shea MT, Yen S, Battle CL, Zlotnick C, Sanislow CA, et al. Gender differences in borderline personality disorder: Findings from the Collaborative Longitudinal Personality Disorders Study. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 2003;44:284–292. doi: 10.1016/S0010-440X(03)00090-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tadic A, Wagner S, Hoch J, Baskaya O, von Cube R, Skaletz C, Dahmen N. Gender differences in Axis I and Axis II comorbidity in patients with borderline personality disorder. Psychopathology. 2009;42:257–263. doi: 10.1159/000224149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nolen-Hoeksema S. Emotion regulation and psychopathology: The role of gender. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2012;8:161–187. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032511-143109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Dubo ED, Sickel AE, Trikha A, Levin A, et al. Axis I comorbidity of borderline personality disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1998;155:1733–1739. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.12.1733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. Mini-mental state: A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cohen J, Cohen P, West SG, Aiken LA. Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences. 3. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Sickel AE, Yong L. The Diagnostic Interview for DSM-IV Personality Disorders (DIPD-IV) Belmont: McLean Hospital; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zanarini MC, Skodel AE, Bender D, Dolan R, Sanislow C, Schaefer E, et al. The Collaborative Longitudinal Personality Disorders Study: Reliability of Axis I and II Diagnoses. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2000;14:291–299. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2000.14.4.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Blake DD, Weathers FW, Nagy LM, Kaloupek DG, Gusman FD, Charney DS, et al. The development of a clinician-administered PTSD scale. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 1995;8:75–90. doi: 10.1007/BF02105408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Weathers FW, Huska JA, Keane TM. PCL-C for DSM-IV. Boston: National Center for PTSD -Behavioral Science Division; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ruggiero KJ, Del Ben K, Scotti JR, Rabalais AE. Psychometric properties of PTSD Checklist-Civilian Version. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2003;16:495–502. doi: 10.1023/A:1025714729117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Weathers FW, Keane TM, Davidson JRT. Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale: A review of the first ten years of research. Depression and Anxiety. 2001;156:132–156. doi: 10.1002/da.1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lovibond SH, Lovibond PF. Manual for the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales. 2. Sydney: Psychology Foundation; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Henry JD, Crawford JR. The short-form version of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS-21): Construct validity and normative data in a large non-clinical sample. British Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2005;44:227–239. doi: 10.1348/014466505X29657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lovibond PF, Lovibond SH. The structure of negative emotional states: Comparison of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) with the Beck Depression and Anxiety Inventories. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1995;33:335–343. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(94)00075-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Saunders JB, Aasland OG, Babor TF, de la Fuente JR, Grant M. Development of the Alcohol Use Disorders Screening Test (AUDIT). WHO collaborative project on early detection of persons with harmful alcohol consumption-II. Addiction. 1993;88:791–804. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb02093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Watson D, Clark LA, Tellegen A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1988;54:1063–1070. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.54.6.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Levin DN, Cook EW, Lang PJ. Fear imagery and fear behavior: Psychophysiological analysis of clients receiving treatment for anxiety disorders. Psychophysiology. 1982;19:571–572. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lang PJ, Cuthbert BN. Affective information processing and the assessment of anxiety. Journal of Behavioral Assessment. 1984;6:369–395. doi: 10.1007/BF01321326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.von Ceumern-Lindenstjena IA, Brunner R, Parzer P, Mundt C, Fielder P, Resch F. Attentional bias in later stages of emotional information processing in female adolescents with borderline personality disorder. Psychopathology. 2010;43:25–32. doi: 10.1159/000255960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Jovev M, Green M, Chanen A, Cotton S, Coltheart M, Jackson H. Attentional processes and responding to affective faces in youth with borderline personality features. Psychiatry Research. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2012.03.027. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Robbins SJ, Ehrman RN. The role of attentional bias in substance abuse. Behavioral and Cognitive Neuroscience Review. 2004;3:243–260. doi: 10.1177/1534582305275423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bardeen JR, Orcutt HK. Attentional control as a moderator of the relationship between posttraumatic stress symptoms and attentional threat bias. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2011;25:1008–1018. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2011.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Salemink E, van den Hout MA, Kindt M. Selective attention and threat: Quick orienting and two versions of the dot-probe task. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2007;45:607–615. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2006.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Frewen PA, Dozois DJA, Joanisse MF, Neufeld RWJ. Selective attention to threat versus reward: Meta-analysis and neural-network modeling of the dot-probe task. Clinical Psychology Review. 2008;28:307–337. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2007.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Tabachnick GG, Fidell LS. Experimental Designs Using ANOVA. Belmont, CA: Duxbury; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 74.McGlashan TH, Grilo CM, Skodol AE, Gunderson JG, Shea MT, et al. The Collaborative Longitudinal Personality Disorders Study: Baseline Axis I/II and II/II diagnostic co-occurrence. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2000;102:256–264. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2000.102004256.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Khera GS, Bleichmar J. Treatment histories fo borderline inpatients. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 2001;42:144–150. doi: 10.1053/comp.2001.19749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Gotlib IH, Krasnoperova E, Yue DN, Joormann J. Attentional biases for negative interpersonal stimuli in clinical depression. 2004;113:127–135. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.113.1.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Lemle R, Mishkind ME. Alcohol and masculinity. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 1989;6:213–222. doi: 10.1016/0740-5472(89)90045-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Schulte MT, Ramo D, Brown SA. Gender differences in factors influencing alcohol use and drinking progression among adolescents. Clinical Psychology Review. 2009;29:535–547. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Mogg K, Bradley BP. A cognitive-motivational analysis of anxiety. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1989;36:809–848. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(98)00063-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Gratz KL, Rosenthal MZ, Tull MT, Lejuez CW, Gunderson JG. An experimental investigation of emotional reactivity and delayed emotional recovery in borderline personality disorder: The role of shame. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 2010;51:275–285. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2009.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Jacob GA, Hellstern K, Ower N, Pillman M, Scheel CN, Rusch N. Emotional reactions to standardized stimuli in women with borderline personality disorder: Stronger negative affect, but no differences in reactivity. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2009;197:808–815. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e3181bea44d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Limberg A, Barnow S, Freyberger HJ, Hamm AO. Emotional vulnerability in borderline personality disorder is cue specific and modulated by traumatization. Biological psychiatry. 2011;69:574–582. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Selby EA, Joiner TE., Jr Cascades of emotion: The emergence of borderline personality disorder from emotional and behavioral dysregulation. Review of General Psychology. 2009;13:219. doi: 10.1037/a0015687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Krueger RF, Eaton N. Personality traits and the classification of mental disorders: Toward a more complete integration in DSM 5 and an empirical model of psychopathology. Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment. 2010;1:97–118. doi: 10.1037/a0018990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Arntz A, Bernstein D, Gielen D, van Nieuwenhuyzen M, Penders K, Ruscio J. Taxometric evidence for the dimensional structure of cluster-C, paranoid, and borderline personality disorders. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2009;23:606–628. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2009.23.6.606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Conway C, Hammen C, Brennan P. A comparison of latent class, latent trait, and factor mixture models of DSM-IV borderline personality disorder criteria in a community setting: implications for DSM-5. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2012;26:693–803. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2012.26.5.793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Suvak MK, Sege CT, Sloan DM, Shea MT, Yen S, Litz BT. Emotional processing in borderline personality disorder. Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment. 2012;3:273–282. doi: 10.1037/a0027331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Chapman AL, Walters KN, Dixon-Gordon KL. Emotional reactivity to social rejection and negative evaluation among persons with borderline personality features. Journal of Personality Disorders. doi: 10.1521/pedi_2012_26_068. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]