Abstract

To the extent that craving serves to compel excessive drinking, it would be of significant import to predict the intensity of an individual’s craving over the course of a drinking episode. Previous research indicates that regular alcohol use (measured by the AUDIT) and the number of drinks individuals have already consumed that evening independently predict craving to drink (Schoenmakers & Wiers, 2010). The current study aims to replicate those findings by testing whether these same variables predict craving to drink in a sample of 1,320 bar patrons in a naturalistic setting. In addition, we extend those findings by testing whether regular alcohol use and self-reported number of drinks consumed interact to predict craving, and whether gender independently predicts craving or interacts with other variables to predict craving. Results indicate that for men, AUDIT score alone predicted craving, whereas for women, AUDIT score and number of drinks consumed interacted to predict craving, with craving highest among women with either high AUDIT scores or relatively high consumption levels. Our findings have implications for targeted intervention and prevention efforts, as women who have a history of harmful alcohol use and consume several drinks in an evening might be at the greatest risk for continued alcohol consumption.

Keywords: alcohol, gender, AUDIT, field, craving

1. Introduction

Craving for alcohol has received much attention in the literature (e.g., Agrawal et al., 2013; Kavanagh et al., 2009; Robinson & Berridge, 2001), and is regarded as an important construct of the complex prediction of drinking-related behaviors (Connolly et al., 2013; Richardson et al., 2008). At the event level, understanding how strongly individuals crave alcohol during a drinking episode might provide important clinical information about their degree of risk for excessive drinking and possible concomitant drinking-related negative consequences.

Individuals with a longer or more intense history of alcohol use may develop an increased tolerance to alcohol (Shapiro & Nathan, 1986), and thus may drink more within an episode in order to obtain the desired physiological and behavioral effects. History of alcohol use, then, might lead to increased craving for alcohol once drinking has been initiated.

Once alcohol consumption has begun, there are associated changes in subjective (King et al., 2011a, 2011b) and cognitive (de Wit & Chutuape, 1993; Field et al., 2010; Fillmore et al., 2005, 2008, 2009; Lyvers & Maltzman, 1991; Marinkovic et al., 2012) processes that may contribute to continued alcohol-seeking. Alternatively, having access to alcohol might decrease craving for alcohol because craving may be activated primarily when access to alcohol is blocked (Tiffany, 1990). Determining whether alcohol consumption increases or decreases craving among drinkers is important, as changes in craving may have an effect on subsequent consumption.

To our knowledge, there has been only one study that took into account both regular/consistent use of alcohol and the amount of alcohol that bar patrons had already consumed that night, and authors found that both variables independently predicted craving (Schoenmakers & Wiers, 2010). However, this study did not address potential interactive effects of these variables, despite the potential for drinking history to differentiate between those who are and are not motivated to continue to drink. The current study aims to replicate and extend these findings to predict craving for alcohol among a sample of drinkers in a naturalistic setting. We expected that (1) those with a more harmful or hazardous recent drinking history, and (2) those who had consumed a greater number of drinks would report greater craving for alcohol. We also predicted that (3) those who had a more intense recent drinking history and a greater number of drinks would evidence the greatest level of craving. In addition, because research indicates that men and women have different drinking histories and patterns (Roberts, 2012; Wilsnack et al., 2009), we examined the role of gender in predicting craving for alcohol.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Participants and Study Design

The protocol was approved by the university IRB and data collection took place over two years. Local law enforcement was apprised of this field investigation, but was not directly involved at any point. The study design and methods are described in detail elsewhere (Celio et al., 2011; Day et al., 2013). Briefly, the study team, in groups of three to four research assistants, recruited individuals between the hours of 11 pm and 2:30 am on Thursday and Friday nights in a college city downtown bar district. Individuals displaying overt symptoms of severe impairment (e.g., grossly incoherent speech, inability to stand) were not invited to participate.

After providing verbal consent (we obtained a waiver of written consent to protect participant anonymity), participants completed a semi-structured interview and a paper-and-pencil survey. Procedures took approximately eight minutes to complete. A total of 1,904 individuals participated in the survey; 155 cases (8.1%) were removed due to invalid responding. Cases were also excluded if they were missing data for age1, gender, AUDIT score, drinks consumed, or craving (n=429). This resulted in a final sample of 1,320 participants. Participation was anonymous and voluntary; no other incentives were provided.

2.2. Measures

Demographics (age, gender, student status) were assessed via the paper-and-pencil survey.

Number of drinks consumed

We calculated the sum of how many standard drinks (12 oz. of beer; 1.5 oz. of hard liquor, or 5 oz. of wine) participants had consumed (1) prior to and (2) during their time in the bar district.

Recent alcohol use

The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT; Babor et al., 2001) was included as a self-report measure of past year drinking history and associated problems/risk. Scores range from 0–40, with higher scores indicating greater risk. The AUDIT has been shown to provide reliable reports under naturalistic conditions (Celio et al., 2011).

Craving

Participants rated their craving for alcohol on a scale of 0 (low craving)-10 (higher craving).

2.3. Statistical Analyses

Variables were examined to ensure they met the assumptions for parametric analyses, then bivariate correlations among the variables of interest were completed. Multiple regression analysis was used to test whether gender, AUDIT total score, number of drinks consumed, and the subsequent two- and three-way interactions predicted craving to drink, controlling for age. All independent variables and interaction terms were entered into the model simultaneously; therefore, order of entry is not a factor when interpreting results.

3. Results

3.1. Sample Demographics and Descriptive Statistics

This sample was predominately male (57.5%) and Caucasian (76.9%) with a mean age of 20.97 years (SD=2.3, range: 15–35). Participants were characterized by a moderate to high level of alcohol-related risk, with a mean AUDIT score of 12.75 (SD = 6.84; range: 0 – 40). Participants reported having consumed an average of 6.32 drinks already that evening (SD=4.56, range: 0–32), and reported a mean craving rating of 5.52 (SD=3.37, range: 0–10). Men (n=759) were significantly older than women (n=561) in the sample (21.2 versus 20.7 years, p<.01), scored higher on the AUDIT (13.91 versus 11.18, p<.01), and reported consuming more drinks (7.5 versus 4.5, p<.01). Men and women did not differ in self-reported craving (p=.90). Craving was negatively associated with age (r=-.08) and positively associated with AUDIT score (r=.40) and number of drinks consumed (r=.19), all p’s <.01. Craving was not associated with gender.

3.2. Predicting craving to drink

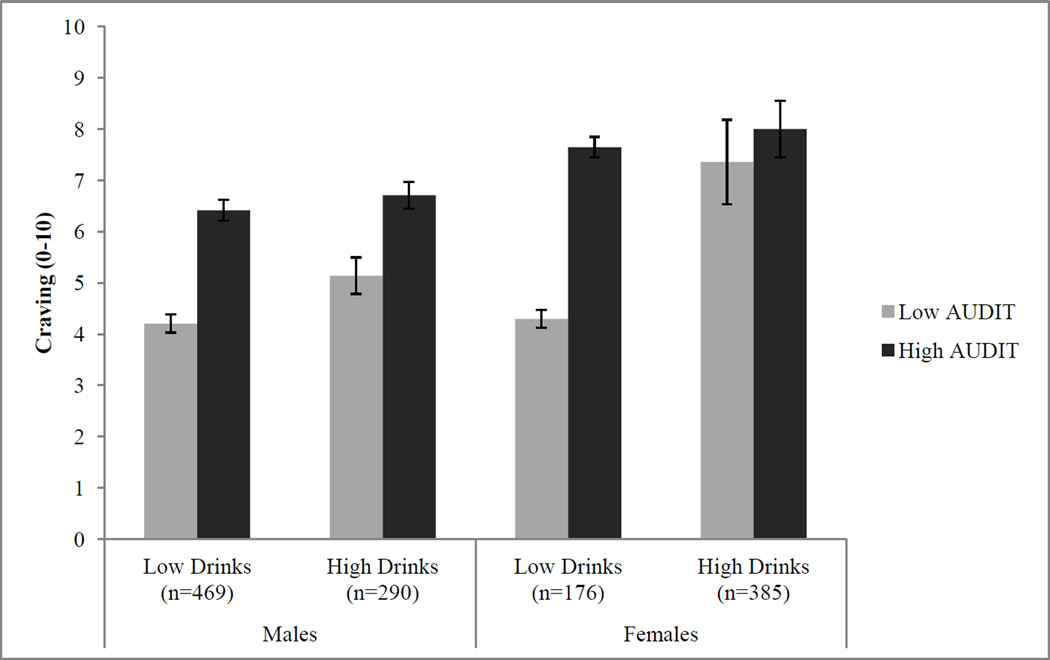

The results of the regression indicated that the complete model explained 20% of the variance (F(8,1319) = 41.42, p <.001) (See Table 1). There were main effects of both gender (β = .16, p <.001, females had greater craving) and AUDIT score (β = .36, p <.001, higher AUDIT scores were associated with greater craving). There was no main effect of total drinks on craving (β = .05, p = .12). Gender and number of drinks interacted to predict craving (β = .10, p = .002), such that among those who reported consuming more drinks there was higher reported craving among women. The three-way interaction of gender, AUDIT, and number of drinks was significant (β = -.12, p <.001). Simple slopes of the 3-way interaction revealed that for women, both AUDIT (β = .36, p <.001) and self-reported number of drinks consumed predicted craving (β = .26, p <.001), whereas for men, only AUDIT score mattered (β = .36, p <.001) (see Figure 1).

Table 1.

Multiple linear regression analyses of craving

| B | SE | β | t | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | −.04 | .04 | −.03 | −1.00 | .32 |

| Gender | 1.10 | .19 | .16 | 5.67 | <.001 |

| AUDIT | .18 | .02 | .36 | 10.04 | <.001 |

| Total Drinks | .04 | .02 | .05 | 1.55 | .12 |

| Gender × AUDIT | .001 | .03 | .001 | .02 | .99 |

| Gender × Total Drinks | .16 | .05 | .10 | 3.13 | .002 |

| AUDIT × Total Drinks | −.004 | .003 | −.04 | −1.25 | .21 |

| Gender × AUDIT × Total Drinks | −.024 | .006 | −.12 | −3.78 | <.001 |

Note. R2 = .20; gender is a dichotomous categorical variable with 0 indicating Male and 1 indicating Female; all continuous variables were centered.

Figure 1.

Craving predicted by AUDIT score, number of drinks, and gender

Note. AUDIT score is identified by median split (low: <=12, high: >=13); drinks consumed are identified by median split (low: <=5, high: >6)

4. Discussion

Consistent with our primary hypothesis, we found that those with higher AUDIT scores had higher craving at the time of testing. We cannot be certain of the direction of causality between AUDIT score and craving, as there may be personality variables that drive both past year drinking history and craving on the night of data collection. For instance, impulsivity is associated with hazardous drinking, as measured by the AUDIT (Curcio & George, 2011; Hamilton, Sinha & Potenza, 2012; MacKillop et al., 2007), and with craving (Joos et al., 2013), particularly for those with poor response inhibition, one facet of impulsivity (Papachristou et al., 2012). Positive urgency (see Cyders & Smith, 2008) may also be closely linked to alcohol consumption and craving, although there is a dearth of research connecting these constructs.

While one previous study found that number of drinks consumed predicted craving (Schoenmakers & Wiers, 2010), and we expected the same, there is evidence that alcohol consumption can both inhibit (e.g., Tiffany, 1990) and enhance (de Wit & Chutuape, 1993) alcohol-seeking. In this sample, number of drinks did not have an independent influence on craving. However, we did not measure family history of alcoholism, which is associated with decreased response to acute alcohol intoxication (e.g., Schuckit, 1994; Shuckit et al., 1996). Not being as sensitive to the effects of alcohol may lead to enhanced craving, while enhanced sensitivity may lead to decreases in craving after only one or two drinks. Understanding how subjective effects of alcohol might influence craving in a field setting may help to clarify the mechanisms by which alcohol use progresses over the course of a night, or how alcohol use progresses to alcohol dependence.

There was an interaction between gender and number of drinks consumed, such that among those who reported consuming relatively more drinks, there was higher reported craving among women than men. Although men were more likely to endorse experiencing an inability to stop drinking once drinking was initiated (AUDIT item #4, p<.01), only women’s reports of craving were influenced by number of drinks. That women experience high levels of craving for alcohol even after having already consumed a greater number of drinks may reflect a difference in the physiological response and/or expectancies related to alcohol consumption. Indeed, men have been found to have dampened autonomic arousal to acute alcohol intoxication compared to women (Udo et al., 2009), but not due to expectancies (Vaschillo et al., 2008). Women are also more likely to reach higher blood alcohol levels sooner (Baraona et al., 2001; Frezza et al., 1990), which may influence decision-making on a drinking night. These effects should continue to be examined among underage drinkers, who may be most susceptible to alcohol’s impairing cognitive effects.

There was also a three-way interaction of gender, AUDIT score and number of drinks consumed. For men, craving was driven only by AUDIT score – men with more risky recent alcohol use reported greater craving. In contrast, a high AUDIT score or a greater number of drinks was associated with greater craving among women, which may point to a link between certain genetic components and increased craving for alcohol (Ait-Daoud et al., 2012; MacKillop et al., 2007).

Due to the cross-sectional nature of data collection, we cannot determine the direction of causality between the variables. We conceptualized AUDIT score as an individual difference that existed prior to the initiation of the drinking episode for that evening; number of drinks consumed as co-occurring or a consequence of AUDIT score, and craving as a dynamic process that waxes and wanes over the course of a night. Although number of drinks might have influenced self-report on the AUDIT,Celio et al. (2011) provides evidence that the AUDIT completed while sober is highly correlated with scores reported in the field. Craving at the beginning of the night also might have predicted the number of drinks consumed. Future research could utilize ecological momentary assessment to capture dynamic changes in craving over the course of a drinking episode. We did not estimate timing of female participants’ menstrual cycle, which may have had an influence on reports of craving (Carpenter et al., 2006; Franklin et al., 2004). Last, our sample also included one 15-year old participant, but when this participant was removed, results and interpretation did not change. There are several neurobiological changes that occur during adolescence (Spear, 2000), and research focused solely on underage or adolescent drinkers would likely provide different results and inferences than the ones presented here.

5. Conclusions

In a field study, we found that gender and history of recent alcohol use independently predict craving to drink, and women who have consumed more drinks experience the greatest craving. If women experience continued craving throughout the night, they may be putting themselves at risk for myriad negative consequences. Women may benefit from targeted prevention efforts, with the goal of modifying drinking patterns to avoid negative outcomes.

Highlights.

Data are collected in a naturalistic/field setting with 1,320 bar patrons

We examine gender, AUDIT score and drinks consumed as predictors of alcohol craving

Women with high AUDIT scores or higher alcohol consumption report greatest craving

In men, high AUDIT scores alone predicted greater craving

Findings have implications for targeted intervention and prevention efforts

Acknowledgements

We thank our many undergraduate and graduate research assistants for their tireless dedication to the project.

Role of Funding Source

Funding for this study was provided by the Binghamton University Professional Employees Council (PEC) Individual Development Award and The Center for Development and Behavioral Neuroscience (CDBN). The Binghamton University PEC and the CDBN had no further role in the study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the paper for publication. Preparation of the manuscript was supported, in part, by T32 AA007459 from the National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Individuals above the age of 35 were also excluded due to small cell sizes. Age range in the full sample ranged from 15–77 years (range 36–77, n=19).

Contributors

All authors contributed to design of the study. Author Day undertook the statistical analysis and wrote the first draft of the manuscript, with editing by all authors. All authors contributed to and have approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

References

- Agrawal A, Wetherill L, Bucholz KK, Kramer J, Kuperman S, Lynskey MT, Bierut LJ. Genetic influences on craving for alcohol. Addictive Behaviors. 2013;38(2):1501–1508. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.03.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ait-Daoud N, Seneviratne C, Smith JB, Roache JD, Dawes MA, Liu L, Johnson BA. Preliminary evidence for cue-induced alcohol craving modulated by serotonin transporter gene polymorphism rs1042173. Frontiers in Psychiatry. 2012;3 doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2012.00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babor TF, Higgins-Biddle JC, Saunders JB, Monteiro MG. The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test: Guidelines for Use in Primary Care World Health Organization (WHO Publication No. 01.6a) Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Baraona E, Abittan CS, Dohmen K, Moretti M, Pozzato G, Chayes ZW, Lieber CS. Gender differences in pharmacokinetics of alcohol. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2001;25:502–507. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter MJ, Upadhyaya HP, LaRowe SD, Saladin ME, Brady KT. Menstrual cycle phase effects on nicotine withdrawal and cigarette craving: a review. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2006;8(5):627–638. doi: 10.1080/14622200600910793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Celio MA, Vetter-O’Hagen CS, Lisman SA, Johansen GE, Spear LP. Integrating field methodology and web-based data collection to assess the reliability of the alcohol use disorders identification test (AUDIT) Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2011;119:142–144. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.05.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connolly JM, Kavanagh DJ, Baker AL, Kay-Lambkin FJ, Lewin TJ, Davis PJ, Quek LH. Craving as a predictor of treatment outcomes in heavy drinkers with comorbid depressed mood. Addictive Behaviors. 2013;38:1585–1592. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curcio AL, George AM. Selected impulsivity facets with alcohol use/problems: The mediating role of drinking motives. Addictive Behaviors. 2011;36:959–964. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cyders MA, Smith GT. Emotion-based dispositions to rash action: Positive and negative urgency. Psychological Bulletin. 2008;134:807–828. doi: 10.1037/a0013341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day AM, Celio MA, Lisman SA, Johansen GE, Spear LP. Acute and Chronic Effects of Alcohol on Trail Making Test Performance Among Underage Drinkers in a Field Setting. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2013;74 doi: 10.15288/jsad.2013.74.635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Wit H, Chutuape MA. Increased ethanol choice in social drinkers following ethanol preload. Behavioral Pharmacology. 1993;4:29–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eng MY, Schuckit MA, Smith TL. The level of response to alcohol in daughters of alcoholics and controls. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2005;79:83–93. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field M, Wiers RW, Christiansen P, Fillmore MT, Verster JC. Acute alcohol effects on inhibitory control and implicit cognition: Implications for loss of control over drinking. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2010;34(8):1346–1352. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01218.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fillmore MT, Blackburn JS, Harrison ELR. Acute disinhibiting effects of alcohol as a factor in risky driving behavior. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2008;95:97–106. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.12.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fillmore MT, Marczinski CA, Bowman AM. Acute tolerance to alcohol effects on inhibitory and activational mechanisms of behavioral control. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2005;66:663–672. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2005.66.663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fillmore MT, Ostling EW, Martin CA, Kelly TH. Acute effects of alcohol on inhibitory control and information processing in high and low sensation-seekers. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2009;100:91–99. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin TR, Napier K, Ehrman R, Gariti P, O'Brien CP, Childress AR. Retrospective study: influence of menstrual cycle on cue-induced cigarette craving. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2004;6:171–175. doi: 10.1080/14622200310001656984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frezza M, di Padova C, Pozzato G, Terpin M, Baraona E, Lieber CS. High blood alcohol levels in women: the role of decreased gastric alcohol dehydrogenase activity and first-pass metabolism. New England Journal of Medicine. 1990;322:95–99. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199001113220205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guillot CR, Fanning JR, Bullock JS, McCloskey MS, Berman ME. Effects of alcohol on tests of executive functioning in men and women: a dose response examination. Experimental and clinical psychopharmacology. 2010;18:409–417. doi: 10.1037/a0021053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gwaltney CJ, Bartolomei R, Colby SM, Kahler CW. Ecological momentary assessment of adolescent smoking cessation: A feasibility study. Nicotine and Tobacco Research. 2008;10:1185–1190. doi: 10.1080/14622200802163118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton KR, Sinha R, Potenza MN. Hazardous drinking and dimensions of impulsivity, behavioral approach, and inhibition in adult men and women. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2012;36:958–966. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2011.01708.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammarberg A, Jayaram-Lindström N, Beck O, Franck J, Reid MS. The effects of acamprosate on alcohol-cue reactivity and alcohol priming in dependent patients: A randomized controlled trial. Psychopharmacology. 2009;205:53–62. doi: 10.1007/s00213-009-1515-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt LJ, Litt MD, Cooney NL. Prospective analysis of early lapse to drinking and smoking among individuals in concurrent alcohol and tobacco treatment. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2012;26:561–572. doi: 10.1037/a0026039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joos L, Goudriaan AE, Schmaal L, de Witte NAJ, Van dB, Sabbe BGC, Dom G. The relationship between impulsivity and craving in alcohol dependent patients. Psychopharmacology. 2013;226(2):273–283. doi: 10.1007/s00213-012-2905-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kavanagh DJ, Andrade J, May J. Imaginary relish and exquisite torture: The elaborated intrusion theory of desire. Psychological Review. 2005;112:446–467. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.112.2.446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kavanagh DJ, May J, Andrade J. Tests of the elaborated intrusion theory of craving and desire: Features of alcohol craving during treatment for an alcohol disorder. British Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2009;48(3):241–254. doi: 10.1348/014466508X387071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keyes KM, Krueger RF, Grant BF, Hasin DS. Alcohol craving and the dimensionality of alcohol disorders. Psychological Medicine. 2011;41:629–640. doi: 10.1017/S003329171000053X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King AC, de Wit H, McNamara PJ, Cao D. Rewarding, stimulant and sedative alcohol responses and relationship to future binge drinking. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2011;68:389–399. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King AC, Roche DJO, Rueger SY. Subjective responses to alcohol: A paradigm shift may be brewing. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2011;35:1726–1728. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2011.01629.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyvers MF, Maltzman I. Selective effects of alcohol on wisconsin card sorting test performance. British Journal of Addiction. 1991;86:399–407. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1991.tb03417.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKillop J, Mattson RE, MacKillop EJA, Castelda BA, Donovick PJ. Multidimensional assessment of impulsivity in undergraduate hazardous drinkers and controls. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2007;68:785–788. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2007.68.785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKillop J, Menges DP, McGeary JE, Lisman SA. Effects of craving and DRD4 VNTR genotype on the relative value of alcohol: an initial human laboratory study. Behavioral and Brain Functions. 2007;3(11) doi: 10.1186/1744-9081-3-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marinkovic K, Rickenbacher E, Azma S, Artsy E. Acute alcohol intoxication impairs top-down regulation of stroop incongruity as revealed by blood oxygen level dependent functional magnetic resonance imaging. Human Brain Mapping. 2012;33(2):319–333. doi: 10.1002/hbm.21213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papachristou H, Nederkoorn C, Havermans R, van dH, Jansen A. Can’t stop the craving: The effect of impulsivity on cue-elicited craving for alcohol in heavy and light social drinkers. Psychopharmacology. 2012;219(2):511–518. doi: 10.1007/s00213-011-2240-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson K, Baillie A, Reid S, et al. Do acamprosate or naltrexone have an effect on daily drinking by reducing craving for alcohol? Addiction. 2008;103:953–959. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02215.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts SCM. Whether men or women are responsible for the size of gender gap in alcohol consumption depends on alcohol measure: A study across the united states. Contemporary Drug Problems: An Interdisciplinary Quarterly. 2012;39:195–212. doi: 10.1177/009145091203900202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson T, Berridge K. Incentive- sensitization and addiction. Addiction. 2001;96:103–114. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2001.9611038.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoenmakers TM, Wiers RW. Craving and attentional bias respond differently to alcohol priming: A field study in the pub. European Addiction Research. 2010;16:9–16. doi: 10.1159/000253859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuckit MA. Low level of response to alcohol as a predictor of future alcoholism. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1994;151:184–189. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.2.184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuckit MA, Tsuang JW, Anthenelli RM, Tipp JE, Nurnberger JI. Alcohol challenges in young men from alcoholic pedigrees and control families: A report from the COGA project. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1996;57:368–377. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1996.57.368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro AP, Nathan PE. Human tolerance to alcohol: The role of pavlovian conditioning processes. Psychopharmacology. 1986;88:90–95. doi: 10.1007/BF00310519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spear LP. Neurobehavioral changes in adolescence. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2000;9:111–114. [Google Scholar]

- Thombs DL, O’Mara R, Dodd VJ, Hou W, Merves ML, Weiler RM, Pokorny SB, Goldberger BA, Reingle J, Werch CC. A field study of bar-sponsored drink specials and their association with patron intoxication. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2009;70:206–215. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2009.70.206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiffany ST. A cognitive model of drug urges and drug-use behavior: role of automatic and nonautomatic processes. Psychological Review. 1990;97:147–168. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.97.2.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Udo T, Bates ME, Mun EY, Vaschillo EG, Vaschillo B, Lehrer P, Ray S. Gender differences in acute alcohol effects on self-regulation of arousal in response to emotional and alcohol-related picture cues. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2009;23:196–204. doi: 10.1037/a0015015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaschillo EG, Bates ME, Vaschillo B, Lehrer P, Udo T, Mun EY, et al. Heart rate variability response to alcohol, placebo, and emotional picture cue challenges: Effects of 0.1-Hz stimulation. Psychophysiology. 2008;45:847–858. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2008.00673.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilsnack RW, Wilsnack SC, Kristjanson AF, Vogeltanz-Holm N, Gmel G. Gender and alcohol consumption: Patterns from the multinational GENACIS project. Addiction. 2009;104:1487–1500. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02696.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]