Abstract

Nutrient stress that produces quiescence and catabolism in normal cells is lethal to cancer cells because oncogenic mutations constitutively drive anabolism. One driver of biosynthesis in cancer cells is the mTORC1 signaling complex. Activating mTORC1 by deleting its negative regulator TSC2 leads to hypersensitivity to glucose deprivation. We have previously shown that ceramide kills cells in part by triggering nutrient transporter loss and restricting access to extracellular amino acids and glucose suggesting that TSC2-deficient cells would be hypersensitive to ceramide. However, murine embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) lacking TSC2 were highly resistant to ceramide-induced death. Consistent with the observation that ceramide limits access to both amino acids and glucose, TSC2−/− MEFs also had a survival advantage when extracellular amino acids and glucose were both reduced. As TSC2−/− MEFs were resistant to nutrient stress despite sustained mTORC1 activity, we assessed whether mTORC1 signaling might be beneficial under these conditions. In low amino acid and glucose medium and following ceramide-induced nutrient transporter loss, elevated mTORC1 activity significantly enhanced the adaptive up-regulation of new transporter proteins for amino acids and glucose. Strikingly, the introduction of oncogenic Ras abrogated the survival advantage of TSC2−/− MEFs upon ceramide treatment most likely by increasing nutrient demand. These results suggest that, in the absence of oncogene-driven biosynthetic demand, mTORC1 dependent translation facilitates the adaptive cellular response to nutrient stress.

Keywords: TSC2, mTOR, nutrient transporters, 4F2hc, GLUT1, ceramide

INTRODUCTION

The mTORC1 signaling complex containing the serine/threonine kinase mTOR is active in many cancers where it promotes protein, lipid, and nucleotide biosynthesis (1, 2). mTORC1 is also activated in tuberous sclerosis, a relatively common disease (1 in 6,000 births (3)) characterized by the growth of benign tumors (hamartomas) in multiple organs. Tuberous sclerosis is caused by heterozygous mutations in the genes encoding either TSC1 or TSC2. The TSC1 and TSC2 proteins form a complex with TBC1D7 that negatively regulates mTORC1 ((4) reviewed in (2, 5)). TSC2 is the GTPase activating protein (GAP) for Rheb, a GTPase that plays an essential role in the activation of mTORC1 by both growth factors and amino acids. Elevated mTORC1 signaling in TSC-deficient cells confers hypersensitivity to glucose withdrawal (6, 7). mTOR-driven anabolism sensitizes these cells to glucose restriction and rapamycin protects TSC2−/− MEFs from death upon glucose withdrawal. These results suggest that mTOR hyperactivation in malignant tumor cells might confer sensitivity to nutrient stress.

Ceramide has been called a “tumor suppressor lipid” based on its ability to slow cellular proliferation, induce differentiation, and trigger cell death (8). Our group recently demonstrated that ceramide kills mammalian cells in part by down-regulating both amino acid and glucose transporters transporter proteins thereby restricting cellular access to extracellular nutrients (9). This finding suggested that sphingolipid drugs might be used to starve constitutively anabolic cancer cells to death while inducing quiescence and catabolism in normal cells. In fact, a water-soluble sphingolipid, FTY720, also triggers nutrient transporter loss and selectively kills highly anabolic cells (10). At higher doses than are required for its actions on S1P receptors, FTY720 has anti-neoplastic activity in vitro and in vivo. As FTY720 analogs that lack its dose-limiting toxicity retain FTY720’s effects on nutrient transporter proteins and its anti-neoplastic activity, FTY720 analogs have the potential to be safe and effective cancer therapies that selectively starve cancer cells to death. Given ceramide’s important role in tissue homeostasis and the therapeutic potential of related sphingolipid drugs, identifying the oncogenic mutations that confer sensitivity and resistance to sphingolipid-induced nutrient transporter loss and death will provide insights into growth control, tumor initiation and progression, and the mechanisms of resistance to cancer therapies.

Because mTORC1-driven anabolism sensitizes TSC2−/− MEFs to glucose depletion (6, 7), we hypothesized that these cells would also be hypersensitive to sphingolipid-induced nutrient transporter loss. In striking contrast to this prediction, TSC2−/− MEFs maintained their hyperactive mTORC1 signaling but were protected from ceramide-induced death. This result led to the discovery that, under some conditions, activated mTORC1 can promote an adaptive cellular response to nutrient restriction.

RESULTS

Loss of TSC2 confers resistance to ceramide and nutrient deprivation

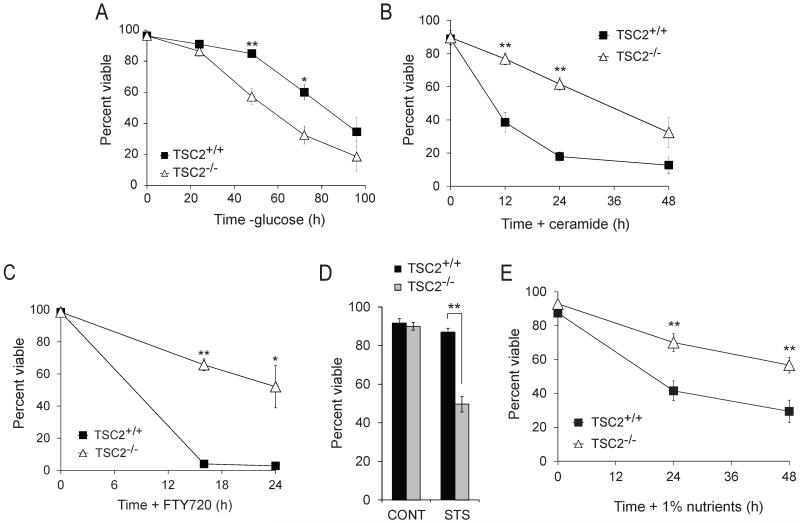

Consistent with published reports (6, 7), TSC2−/− MEFs died faster than their TSC2+/+ counterparts when deprived of glucose (Fig. 1A). As ceramide down-regulates the broadly expressed glucose transporter GLUT1 (9), we expected that TSC2−/− MEFs would also be hypersensitive to C2-ceramide, a form of this sphingolipid that is converted to the physiologic long-chain version within cells (11, 12). Surprisingly, TSC2−/− MEFs were highly resistant to ceramide-induced death relative to TSC2+/+ controls (Fig. 1B). TSC2−/− MEFs were also protected from death triggered by FTY720, a related sphingolipid that also produces starvation secondary to nutrient transporter loss (10) (Fig. 1C). TSC2−/− MEFs were, however, hypersensitive to staurosporine-induced death (Fig. 1D) consistent with published data (13) suggesting that the resistance of TSC2−/− MEFs to sphingolipids was specific. Ceramide and FTY720 down-regulate both glucose and amino acid transporters (9, 10). To mimic the partial nutrient transporter loss induced by ceramide and FTY720, cells were transferred to DMEM containing 1% the normal amount of amino acids and glucose. Combined restriction of amino acids and glucose killed cells with faster kinetics than glucose restriction alone (Fig. 1E). However, TSC2−/− MEFs were resistant to combined amino acid and glucose restriction relative to TSC2+/+ controls. Together, these findings suggest that TSC2−/− MEFs have a survival advantage under some forms of nutrient stress.

Figure 1. Loss of TSC2 confers resistance to nutrient stress and ceramide.

The viability of TSC2+/+ and TSC2−/− MEFs was measured by vital dye exclusion and flow cytometry after glucose deprivation (A), treatment with 20 μM ceramide (B), or 5 μM FTY720 (C), treatment with 100 nM staurosporine (STS) for 24 h (D), or transfer to medium containing 1% the normal amount of amino acids and glucose (E). In all experiments, means from 3-5 experiments are shown +/− SEM. *, p < 0.05 and **, p < 0.01 when results from TSC2+/+ and TSC2−/− MEFs are compared using a t-test.

TSC2−/− MEFs are resistant to nutrient deprivation despite the sustained activation of mTORC1

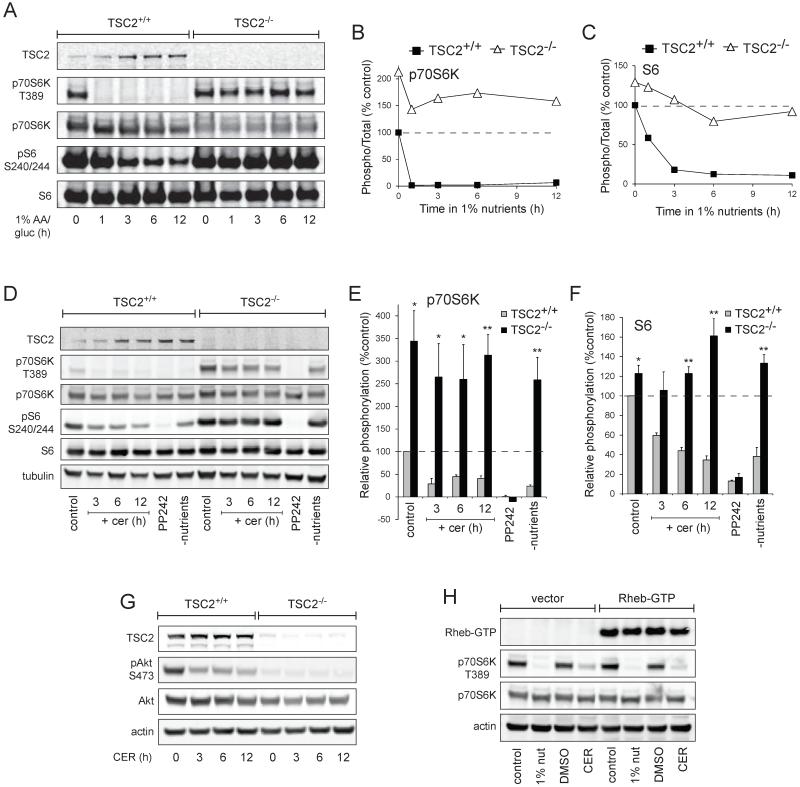

Amino acid withdrawal rapidly inactivates mTORC1 (reviewed in (14, 15)). Rag GTPases regulate mTORC1 activity by controlling its localization to the lysosome where it is activated by the Rheb GTPase (16, 17). Glucose limitation, on the other hand, reduces mTORC1 via AMPK-dependent phosphorylation of TSC2 and Raptor (7, 18). We tested whether limiting glucose and amino acids was sufficient to inhibit mTORC1 in TSC2−/− MEFs by monitoring the mTORC1-specific phosphorylation site in p70S6 kinase, Thr389, and the p70S6 kinase-dependent sites in the ribosomal S6 protein, serines 240 and 244 (19, 20). mTORC1 was rapidly inactivated in TSC2+/+ MEFs transferred to medium containing 1% the normal level of amino acids and glucose but mTORC1 remained active in TSC2−/− MEFs (Fig. 2A-C). In fact, p70S6K Thr389 phosphorylation in nutrient-restricted TSC2−/− MEFs exceeded that present in TSC2+/+ MEFs in complete medium at all time points examined (Fig. 2B). As expected, ceramide treatment reduced mTORC1 signaling in TSC2+/+ MEFs (Fig. 2D-F). mTORC1 signaling in TSC2−/− MEFs was, however, resistant to inhibition by ceramide. TSC2−/− MEFs exhibited higher Thr389 and S6 phosphorylation in the presence of ceramide than was seen in TSC2+/+ MEFs in control medium at all time points examined (Fig. 2E&F). The partial decrease in the phosphorylation of p70S6K in TSC2−/− MEFs treated with ceramide (Fig. 2E) might be due to ceramide-induced nutrient transporter loss (9) or to PP2A activation by ceramide (21). The mTOR kinase inhibitor PP242 eliminated mTORC1 activity in both genotypes confirming that these phosphorylations are mTORC1-dependent. Thus, TSC2−/− MEFs are resistant to death induced by sphingolipids or nutrient deprivation despite sustained mTORC1 activity.

Figure 2. TSC2−/− MEFs are resistant to ceramide and nutrient stress despite elevated mTORC1 activity.

A) TSC2+/+ and TSC2−/− MEFs were maintained in medium containing 1% the normal amount of amino acids and glucose for the indicated interval and mTORC1 signaling evaluated by western blot using a LI-COR Odyssey imager. B,C) The results of (A) were quantified and the signal from phosphorylated p70S6K (B) or ribosomal S6 (C) was expressed relative to the total protein and normalized to the control TSC2+/+ sample. The means from two independent experiments are graphed. D) TSC2+/+ and TSC2−/− MEFs were treated with 20 μM ceramide for the indicated intervals or maintained in 2.5 μM PP242 or nutrient-free medium for 12 h and mTORC1 signaling evaluated by western blot using a LI-COR Odyssey imager. Representative blots are shown. E,F) The results of (D) were quantified as in (B,C). Means +/− SEM are shown for 3 independent experiments. *, p < 0.05 and **, p < 0.01 when results from TSC2+/+ and TSC2−/− MEFs are compared using a t-test. G) As in (D), but Akt phosphorylation at Ser 473 was measured. H) TSC2−/− MEFs expressing HA-tagged Rheb-Q64L (Rheb-GTP) were placed in medium containing 1% the normal amount of amino acids and glucose or treated with ceramide and p70S6 kinase phosphorylation measured at 3 h.

Activation of p70S6K triggers a negative feedback loop that reduces Akt phosphorylation (22-24). As p70S6K activity declined slightly in ceramide-treated TSC2−/− MEFs (Fig. 2D-F), we determined whether loss of negative feedback might increase Akt activation. Consistent with reports that ceramide inhibits Akt (25, 26), phosphorylation of Akt Ser473 declined in ceramide-treated TSC2+/+ MEFs (Fig. 2G). Akt phosphorylation was undetectable in TSC2−/− MEFs and, in keeping with the maintenance of mTORC1 activity, this was not altered by ceramide. TSC2 serves as the GAP for Rheb, a GTPase required for mTORC1 activation by all stimuli (14). When expressed at high levels, activated mutants of Rheb maintain mTORC1 activity in the absence of amino acids (17). However, under our experimental conditions, Rheb-Q64L expression did not maintain mTORC1 activity, most likely due to insufficient over-expression (Fig. 2H).

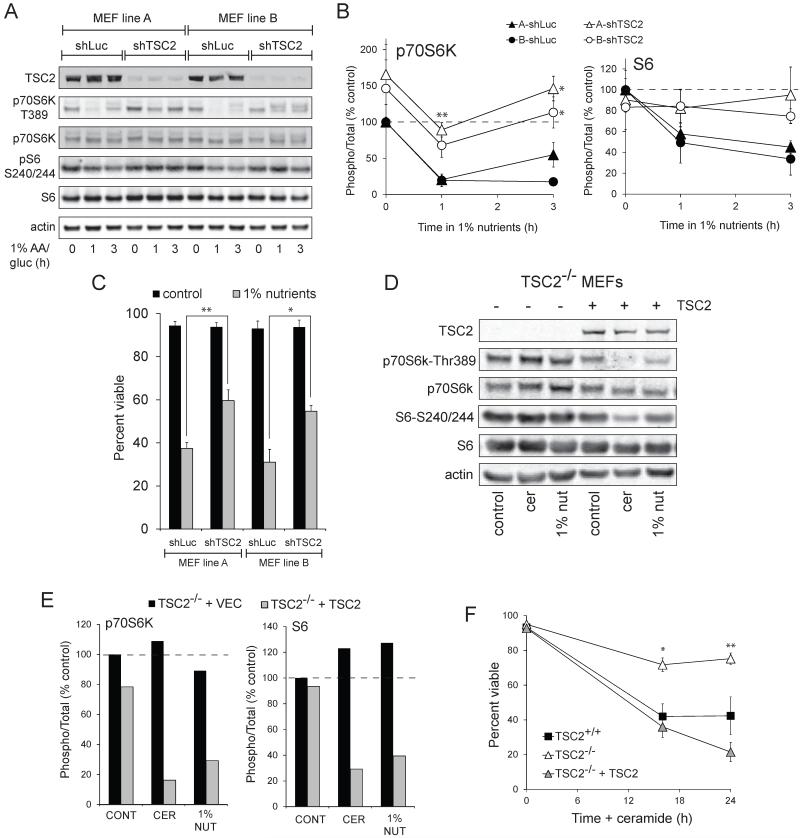

To confirm that the resistance of TSC2−/− MEFs was due to the loss of TSC2, we knocked down TSC2 using a previously validated shRNA (27). Two independent MEF lines (referred to as A and B) were transduced to rule out cell line-specific effects. Similar to the TSC2−/− MEFs (Fig. 2), MEF lines with TSC2 knockdown exhibited sustained phosphorylation of p70S6K at Thr389 and of ribosomal protein S6 at serines 240/244 following nutrient deprivation (Fig. 3A&B). MEFs expressing shRNA against TSC2 were again resistant to death following combined glucose and amino acid deprivation despite their sustained mTORC1 signaling (Fig. 3C). As a complimentary approach, we also re-expressed TSC2 in TSC2−/− MEFs. Following the introduction of TSC2, mTORC1 activity declined in nutrient deprived or ceramide treated TSC2−/− MEFs similar to TSC2+/+ control MEFs (Fig. 3D&E). The sensitivity of TSC2−/− MEFs to ceramide-induced death was similarly restored by reconstitution with TSC2 (Fig. 3F). Finally, TSC2−/− MEFs may have reduced mTORC2 activity (28). In yeast, TORC2 regulates ceramide metabolism (29). However, Rictor−/− MEFs that completely lack mTORC2 (30) were as sensitive to ceramide and nutrient restriction as Rictor+/+ controls (data not shown). Together, these studies demonstrate that the resistance of TSC2−/− MEFs to nutrient stress is due to the deletion of TSC2.

Figure 3. The loss of TSC2 is responsible for the sustained mTORC1 signaling and increased survival in ceramide-treated or nutrient deprived TSC2−/− MEFs.

A) Two wild type MEFs lines from different sources were transduced with retroviruses expressing shRNA targeting luciferase or TSC2 and nutrient-deprived for the indicated interval. mTORC1 signaling was evaluated by western blot using a LI-COR Odyssey imager. A representative blot is shown. B) The results of (A) were quantified and the signal from phosphorylated p70S6K (left) or ribosomal S6 (right) was expressed relative to the total protein and normalized to the control TSC2+/+ sample. C) The TSC2 knockdown MEF lines used in (A) were maintained in 1% nutrients for 24 h and viability measured by vital dye exclusion and flow cytometry. In (B&C), means +/− SEM are shown for 3 independent experiments. *, p < 0.05 and **, p < 0.01 when matched shLuc and shTSC2 MEF lines are compared using a t-test. D) TSC2−/− MEFs stably expressing empty vector or human TSC2 were maintained in normal DMEM, treated with 20 μM ceramide or transferred to 1% nutrient medium for 6 h. mTORC1 signaling was evaluated by western blot using a LI-COR Odyssey imager. E) The results of (D) were quantified and the signal from phosphorylated p70S6K (left) or ribosomal S6 (right) was expressed relative to the total protein and normalized to the control TSC2−/− + vector sample. The means from 2 independent experiments are shown. F) TSC2+/+, TSC2−/−, and TSC2−/− + vector MEFs reconstituted with TSC2 were treated with 20 μM ceramide and viability measured at the indicated time points. The averages of 3-4 independent experiments are shown +/− SEM. *, p < 0.05 and **, p < 0.01 when TSC2−/− + vector and TSC2−/− MEFs + TSC2 are compared using a t-test.

Elevated mTORC1 signaling facilitates the adaptive up-regulation of transporters following nutrient deprivation

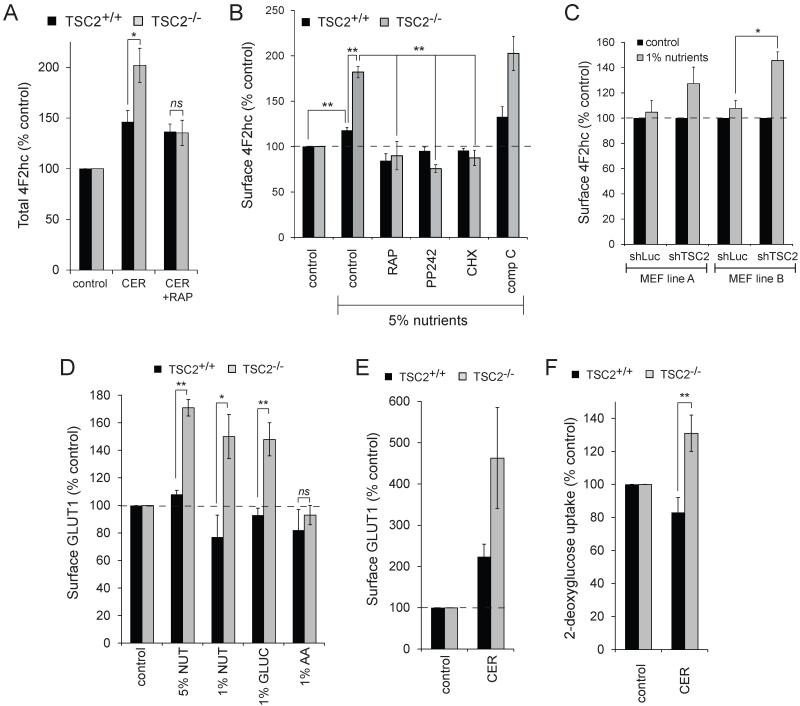

TSC2−/− MEFs maintain elevated mTORC1 signaling even in the presence of ceramide (Fig. 2D-F). As mTORC1 activation can prevent nutrient transporter down-regulation in growth factor withdrawn cells (31, 32), we tested whether sustained mTORC1 activity in TSC2−/− MEFs prevented ceramide-induced nutrient transporter loss. While loss of TSC1 or TSC2 leads to amino acid permease trafficking defects (33), the 4F2hc expression pattern was similar in TSC2+/+ and TSC2−/− MEFs (Fig. 4A). Ceramide down-regulated 4F2hc with equal efficiency in both TSC2+/+ and TSC2−/− MEFs (Fig. 4B). However, after 6 h 4F2hc surface levels rebounded selectively in TSC2−/− MEFs, eventually exceeding baseline levels. Similar results were obtained in cells treated with FTY720 (data not shown). When TSC2−/− MEFs were reconstituted with TSC2, nutrient transporters were no longer restored to the cell surface after ceramide treatment demonstrating that this response stems from the deletion of TSC2 (Fig. 4C). Thus, while transporters were down-regulated similarly by ceramide in MEFs of both genotypes, the effect is temporary in TSC2−/− MEFs.

Figure 4. Surface amino acid transporter expression rebounds selectively in TSC2−/− MEFs after ceramide treatment and depends on mTORC1 activity and translation.

A) 4F2hc staining in TSC2+/+ and TSC2−/− MEFs grown in standard culture medium. B) TSC2+/+ and TSC2−/− MEFs were treated with 20 μM ceramide and surface 4F2hc levels measured by flow cytometry. C) TSC2−/− MEFs stably expressing empty vector or TSC2 were treated with 20 μM ceramide and surface 4F2hc levels measured by flow cytometry. D) Amino acid uptake by TSC2+/+ and TSC2−/− MEFs was measured during the indicated intervals after the addition of 20 μM ceramide. E) TSC2+/+ or TSC2−/− MEFs were treated with ceramide in the presence or absence of 20 mM BCH as indicated. When compared with a t-test, TSC2+/+ with ceramide and TSC2−/− with ceramide and BCH are not significantly different (p = 0.20). F) TSC2+/+ and TSC2−/− MEFs were treated with the indicated drugs and surface 4F2hc levels measured at 12 h (CER, 20 μM ceramide; RAP, 100 nM rapamycin; CHX, 50 μg/ml cycloheximide). G) TSC2+/+ and TSC2−/− MEFs were treated with or without rapamycin and ceramide as indicated and viability measured at 24 h by flow cytometry.

The results in Fig. 4B suggest that the survival advantage of ceramide-treated TSC2−/− MEFs might stem from increased access to extracellular nutrients. To test this idea, we measured amino acid uptake in MEFs treated with ceramide and pulsed with 3H-labeled amino acids for the final 2 h before lysis. Consistent with surface amino acid transporter levels (Fig. 4B), amino acid uptake was not different in TSC2+/+ and TSC2−/− MEFs between 3 and 5 h after ceramide addition (Fig. 4D). However, amino acid uptake was higher in TSC2−/− MEFs than in TSC2+/+ controls between 10 and 12 h after ceramide addition when 4F2hc surface levels had rebounded in TSC2−/− but not TSC2+/+ MEFs (Fig. 4B&D). 2-aminobicyclo-(2,2,1)-heptane-2-carboxylic acid (BCH) is a selective, competitive inhibitor of 4F2hc-dependent amino acid import (34, 35). BCH alone was not toxic (Fig. 4E). However, BCH reduced the survival of TSC2−/− MEFs treated with ceramide. Taken together, these results suggest that the resistance of TSC2−/− MEFs to ceramide-induced death stems in part from their ability to restore access to extracellular nutrients.

To confirm that the restoration of transporters following ceramide treatment was mTORC1-dependent, we determined the effect of rapamycin on transporter expression levels. Rapamycin alone slightly decreased surface 4F2hc levels in both TSC2-wildtype and knockout MEFs (Fig. 4F). When ceramide and rapamycin were combined, the rebound in 4F2hc expression seen in ceramide-treated TSC2−/− MEFs no longer occurred. The restoration of 4F2hc surface levels in TSC2−/− MEFs following ceramide treatment thus depends on mTORC1 activity. mTORC1 promotes protein translation. Although blocking protein translation with cycloheximide had no effect on 4F2hc levels in the absence of ceramide (Fig. 4F), 4F2hc levels were further reduced in TSC2+/+ MEFs and 4F2hc levels no longer rebounded in TSC2−/− MEFs when cycloheximide and ceramide were combined. Together, these results suggest that mTORC1-dependent new protein synthesis restores surface amino acid transporter levels after sphingolipid-induced down-regulation in TSC2−/− MEFs. If restoration of surface transporters contributes to the survival of TSC2−/− MEFs, then rapamycin might be expected to reduce the survival of TSC2−/− MEFs treated with ceramide. However, rapamycin protects cells from ceramide treatment (9) and from nutrient stress (6, 7) by limiting nutrient demand. In fact, rapamycin increased the survival of ceramide-treated TSC2+/+ MEFs (Fig. 4G). At the same time, rapamycin eliminated the survival advantage of TSC2−/− MEFs. Together, these findings are consistent with a model where nutrient access and bioenergetic demand define cellular sensitivity to ceramide.

Ceramide down-regulates nutrient transporter proteins but does not increase their degradation (9). Consistent with this, total cellular levels of 4F2hc were not decreased by ceramide (Fig. 5A). In fact, while surface levels of 4F2hc decreased (Fig. 4B), the total cellular levels of 4F2hc were increased by ceramide in both TSC2+/+ and TSC2−/− MEFs (Fig. 5A). The increase in total 4F2hc was enhanced in TSC2−/− MEFs and rapamycin dependent. Total 4F2hc levels might increase in ceramide-treated cells as part of an adaptive response to nutrient stress caused by transporter down-regulation. Under nutrient stress, both yeast and mammalian cells synthesize new transporters to increase uptake capacity. We tested whether 4F2hc was adaptively up-regulated in response to nutrient stress. After 24 h of nutrient limitation, TSC2+/+ MEFs exhibited a mild but statistically significant increase in 4F2hc expression levels to 120% control (Fig. 5B). In TSC2−/− MEFs, the adaptive up-regulation of transporter proteins was greatly enhanced; 4F2hc levels rose to 180% control. A similar response was observed in TSC2 knockdown MEF lines A and B (Fig. 5C). Rapamycin, the mTOR kinase inhibitor PP242, and cycloheximide blocked the dramatic up-regulation of 4F2hc in nutrient-stressed TSC2−/− MEFs, normalizing the responses of TSC2+/+ and TSC2−/− MEFs (Fig. 5B). AMPK is activated under low glucose conditions and plays a key role in the adaptive response to nutrient stress by limiting anabolism and promoting catabolism. AMPK is hyperactivated in TSC2−/− MEFs ((36, 37) and data not shown). The AMPK inhibitor compound C (38) did not diminish 4F2hc up-regulation under nutrient stress in TSC2+/+ or TSC2−/− MEFs (Fig. 5B). In fact, compound C treatment slightly enhanced 4F2hc up-regulation, possibly by eliminating AMPK’s ability to inhibit mTORC1. Given the results in Fig. 5A-C, an enhanced adaptive response to nutrient stress is a plausible explanation for the suprabasal levels of surface 4F2hc in TSC2−/− MEFs after 12 h of ceramide treatment (Figs. 4B-C&4F).

Figure 5. Adaptive nutrient transporter up-regulation is dramatically enhanced in TSC2−/− MEFs.

A) TSC2+/+ and TSC2−/− MEFs were incubated in ceramide with or without rapamycin for 12 h, fixed and permeabilized, and total cellular 4F2hc quantified by flow cytometry. B) TSC2+/+ and TSC2−/− MEFs were incubated in medium containing 5% the normal amount of amino acids and glucose for 24 h and surface 4F2hc levels measured by flow cytometry. This degree of nutrient stress does not trigger cell death but causes cell cycle arrest. Where indicated, rapamycin (100 nM), PP242 (2.5 μM), cycloheximide (CHX, 50 μg/ml), or compound C (comp C, 10 μM) were present during the 24 h treatment. C) 4F2hc surface levels in wild type MEF lines stably expressing shRNA against luciferase or TSC2 after 12 h in 1% nutrient medium. D) TSC2+/+ and TSC2−/− MEFs were incubated in medium containing either 1% or 5% the normal amount of amino acids and glucose, 1% glucose, or 1% the normal amount of amino acids and surface levels of GLUT1 measured by flow cytometry at 12 h. E) As in (D), but cells were treated with ceramide for 12 h. F) TSC2+/+ and TSC2−/− MEFs treated with ceramide for 12 h before 2-deoxy-glucose uptake was measured. In all panels, averages of 3-13 independent experiments are shown +/− SEM. n.s., not significant (p > 0.05); *, p < 0.05; and **, p < 0.01 using a t-test to compare the indicated samples.

As TSC2−/− MEFs are resistant to sphingolipids that down-regulate both amino acid and glucose transporters (Fig. 1B-C) (9), we next evaluated glucose transporter levels in nutrient stressed TSC2−/− MEFs. As for 4F2hc (Fig. 5B), surface GLUT1 levels were up-regulated robustly in nutrient stressed TSC2−/− MEFs but not TSC2+/+ controls (Fig. 5D). Adaptive up-regulation of GLUT1 occurred selectively in response to glucose restriction; amino acid limitation did not increase GLUT1 levels. After 12 h of treatment, ceramide also triggered an enhanced adaptive up-regulation of GLUT1 in TSC2−/− MEFs (Fig. 5E). This enhanced GLUT1 expression led to elevated glucose uptake in ceramide-treated TSC2−/− MEFs relative to controls (Fig. 5F). In summary, TSC2 deletion enhanced the adaptive up-regulation of both amino acid and glucose transporters in response to nutrient stress and increased cellular access to extracellular nutrients in the presence of ceramide.

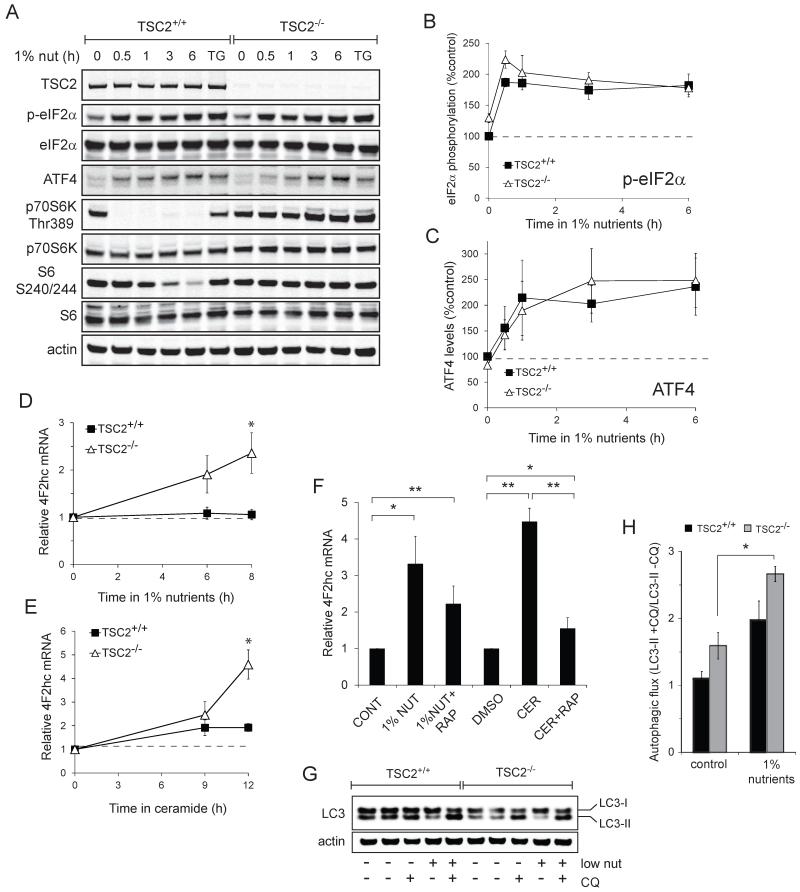

The GCN2 kinase is a key regulator of the cellular response to nutrient stress (39). Amino acid limitation leads to reduced tRNA charging. Uncharged tRNAs bind and activate the GCN2 kinase which phosphorylates eIF2α. When eIF2α is phosphorylated, the over-all rate of translation declines, but several transcripts are translated at a higher efficiency, including the mRNA for the ATF4 transcription factor. Increased ATF4 protein level leads to an adaptive response to amino acid limitation that includes the transcription of amino acid transporter genes such as 4F2hc (40-44). eIF2α phosphorylation in response to ER stress is altered in TSC2−/− MEFs (45). However, eIF2α phosphorylation and ATF4 induction was similar in TSC2+/+ and TSC2−/− MEFs limited for extracellular nutrients (Fig. 6A-C). These results suggest that increased nutrient transporter levels in nutrient stressed TSC2−/− MEFs do not stem from differences eIF2α activity. However, 4F2hc mRNA abundance was significantly increased in nutrient-limited TSC2−/− MEFs relative to controls (Fig. 6D). Ceramide treatment produced similar changes (Fig. 6E). In both conditions, the increase in 4F2hc mRNA in TSC2−/− MEFs was inhibited by rapamycin (Fig. 6F). These results suggest that the enhanced, adaptive 4F2hc up-regulation in TSC2−/− MEFs relative to TSC2+/+ MEFs is a consequence of mTORC1-driven increases in mRNA abundance and translation.

Figure 6. eIF2α activation and autophagy are similarly enhanced in in nutrient-stressed TSC2+/+ and TSC2−/− MEFs.

A) TSC2+/+ and TSC2−/− MEFs were maintained in 1% nutrient medium for the indicated interval. eIF2α and mTORC1 signaling was evaluated by western blot using a LI-COR Odyssey imager. Thapsigargin (2 μM, TG) was used as a positive control for eIF2α activation. B,C) eIF2α phosphorylation was quantified and expressed relative to total eIF2α (B); total ATF4 levels were also quantified (C). Values were normalized to the signal in untreated TSC2+/+ samples and the averages of 3 independent experiments plotted +/− SEM. D,E) mRNA was isolated from TSC2+/+ or TSC2−/− MEFs maintained in standard medium and DMEM containing 1% nutrients (D) or 15 μM ceramide (E). 4F2hc mRNA levels were measured using quantitative RT-PCR and expressed relative to actin mRNA. F) As in (D,E) except that 100 nM rapamycin (rap) was added where indicated; 1% nutrient treatment was for 8 h, ceramide treatment was for 12 h. G,H) TSC2+/+ and TSC2−/− MEFs were maintained in 1% nutrient medium for 3 h in the presence or absence of 25 μM chloroquine (CQ) and LC3-II levels measured by western blotting. A representative blot is shown (G); average ratios of LC3-II intensity +/− chloroquine are plotted +/− SEM as a measure of autophagic flux. In all panels, average results of 3 independent experiments are shown +/− SEM. *, p ≤ 0.05; **, p ≤ 0.01. In 6F, p = 0.37 when comparing 1% nutrients +/− rapamycin.

Reports indicate that TSC2−/− MEFs fail to induce autophagy normally due to the constitutive activation of mTORC1 (46, 47). Autophagy provides an important source of nutrients when access to extracellular nutrients is limiting. Given their enhanced ability to synthesize new transporters under nutrient stress, we evaluated autophagy in TSC2−/− MEFs under our experimental conditions. Autophagosome turnover (autophagic flux) can be assessed by comparing the abundance of proteins degraded by autophagy in the presence and absence of inhibitors of lysosomal degradation (48). LC3-II present on the inner autophagosomal membrane is degraded along with autophagosomes, and the ratio of LC3-II levels +/− chloroquine is one measure of autophagic flux. In normal growth medium, we found that TSC2−/− MEFs had a slightly elevated rate of autophagic flux consistent with a higher basal level of bioenergetic stress secondary to mTORC1 activation (Fig. 6G-H). When shifted to low nutrient medium, TSC2−/− and TSC2+/+ MEFs increased the rate of autophagy to a similar extent. Thus, under our experimental conditions, TSC2−/− MEFs are able to engage in productive autophagy despite constitutive activation of mTORC1.

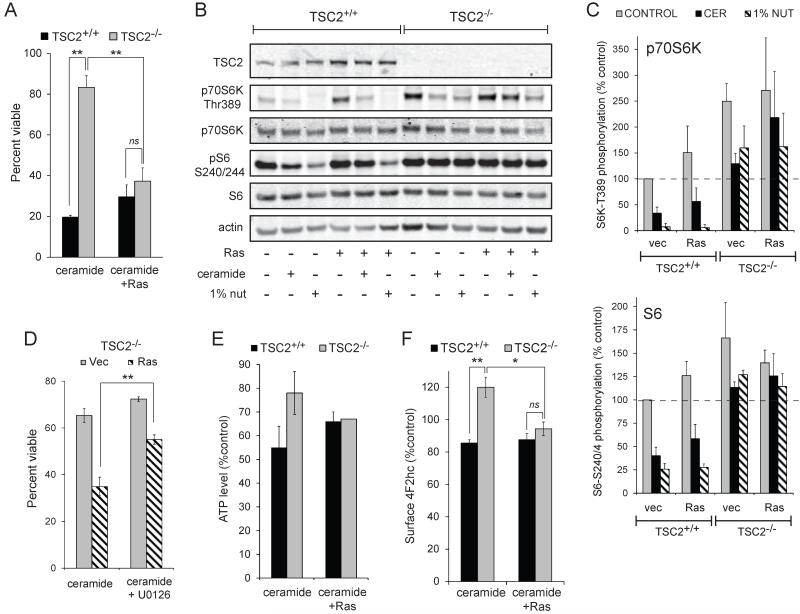

Transforming mutations eliminate the resistance of TSC2−/− MEFs to ceramide

The resistance of TSC2-deficient cells to extracellular nutrient deprivation and sphingolipid-induced death despite elevated mTORC1 activity suggests that mTORC1 may protect nutrient-limited cells under some conditions. Given that ceramide metabolism is altered in many cancers and our interest in developing sphingolipid-based chemotherapeutics that target nutrient transporter proteins, we assessed whether transformed cells could be rendered resistant to sphingolipid-induced nutrient transporter loss by deleting TSC2. Oncogenic, activated H-RasG12V was introduced via retroviral transduction. As expected, transduction with control viruses did not affect the resistance of TSC2−/− MEFs to ceramide (Fig. 7A). However, introducing activated Ras eliminated the survival advantage of TSC2−/− MEFs despite sustained mTORC1 activity (Fig. 7A-C). Blocking down-stream signaling with the MEK inhibitor U0126 partially restored the resistance of TSC2−/− MEFs confirming that H-RasG12V dependent signaling was detrimental (Fig. 7D). A potential explanation for these results was that Ras increases metabolic demand by driving anabolism. Consistent with this idea, H-RasG12V-expression normalized ATP levels in ceramide-treated TSC2−/− and TSC2+/+ MEFs (Fig. 7E). Interestingly, TSC2−/− MEFs expressing oncogenic Ras were no longer able to up-regulate 4F2hc (Fig. 7F), possibly because oncogenic Ras depleted nutrient or energy reserves required for new protein synthesis. Together, these experiments suggest that mTORC1-driven adaptive nutrient transporter up-regulation in TSC2−/− MEFs depends on both nutrient transporter up-regulation and the conservation of resources due to the silencing of parallel anabolic pathways.

Figure 7. Loss of TSC2 does not protect from nutrient stress in the presence of oncogenic Ras.

A) TSC2+/+ and TSC2−/− MEFs stably expressing H-RasG12V were treated with ceramide and viability measured at 24 h. B) TSC2+/+ or TSC2−/− MEFs expressing oncogenic Ras were treated with 20 μM ceramide or maintained in 1% nutrient medium for 6 h and mTORC1 signaling was evaluated by western blot using a LI-COR Odyssey imager. C) The results of (B) were quantified and the phosphorylation of p70S6K and S6 expressed relative to their respective total protein signals and normalized to TSC2+/+ MEFs + vector. D) TSC2−/− MEFs stably expressing H-RasG12V were treated with ceramide +/− 10 μM U0126 and viability measured at 24 h. E) TSC2+/+ or TSC2−/− MEFs expressing empty vector or oncogenic Ras were treated with 20 μM ceramide for 12 h and ATP levels were measured. F) As in (E), but surface 4F2hc levels measured by flow cytometry. In all panels, averages of at least 3 independent experiments are shown +/− SEM. n.s., not significant (p > 0.05); *, p < 0.05; and **, p < 0.01 when the indicated samples were compared using a t-test. In panel E, when TSC2+/+ and TSC2−/− vector cells were compared with a t-test, p = 0.16; for Ras-expressing cells p = 0.83.

DISCUSSION

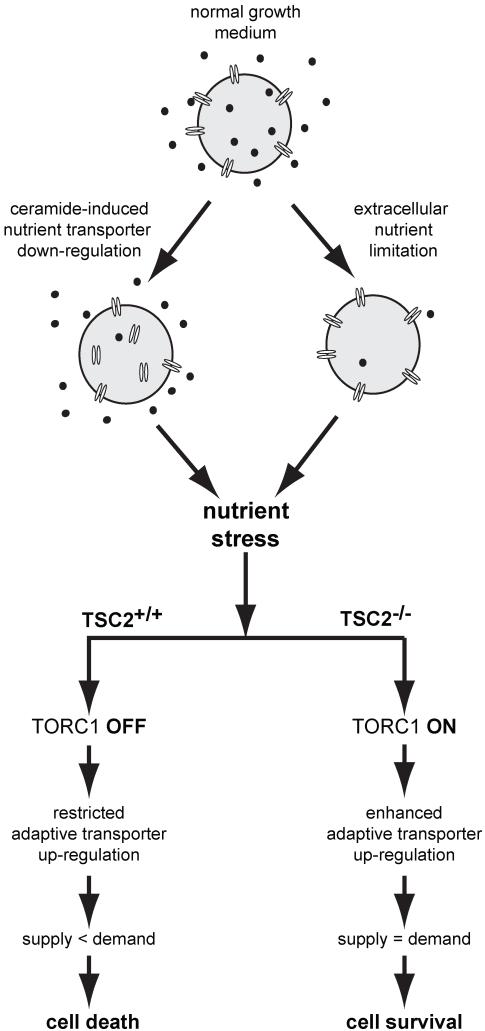

These results suggest a novel, adaptive role for mTORC1 signaling in non-transformed cells during extracellular nutrient limitation or sphingolipid-induced nutrient transporter loss (Fig. 8). Nutrient deprivation initiates an adaptive response that includes transporter up-regulation (40, 42-44). We demonstrated that the adaptive up-regulation of two transporters, 4F2hc and GLUT1, is dramatically enhanced in nutrient stressed TSC2−/− MEFs (Figs. 4 and 5). Although reagents are not currently available to quantify their surface levels by flow cytometry, it is likely that other nutrient transporters are similarly affected. This increased nutrient transporter expression provides a potential explanation for the increased survival of TSC2−/− MEFs as it would provide greater access to extracellular nutrients (Figs.4D&5F). Consistent with this model, BCH significantly reduced the survival advantage of TSC2−/− MEFs over TSC2+/+ controls despite the fact that it only inhibits a subset of amino acid transporters (Fig. 4E). Interestingly, TSC2−/− MEFs are also better able to adapt to hypoxia. Under hypoxia, TSC2−/− MEFs exhibit a more sustained accumulation of Hif-1α target gene mRNA and a higher rate of protein translation conferring resistance to death and allowing increased cell accumulation (49, 50). Thus, TSC2−/− MEFs have an advantage under two forms of metabolic stress, hypoxia and combined glucose and amino acid limitation, because they are better able to execute an adaptive response that depends on protein translation (Figs. 4F and 5B).

Figure 8. Model for the resistance of TSC2−/− MEFs to nutrient stress.

Loss of surface nutrient transporter proteins or extracellular nutrient limitation produces nutrient stress. In wildtype MEFs, mTORC1 is inactive and the limited adaptive response is insufficient to relieve the nutrient stress, eventually leading to cell death. In TSC2−/− MEFs, in contrast, an enhanced adaptive up-regulation of nutrient transporters occurs via mTORC1-driven translation and possibly transcription. In the absence of oncogene-driven anabolism, the resulting increase in nutrient uptake is sufficient to protect TSC2−/− MEFs from death. When oncogenic Ras increases nutrient demand and/or reprograms metabolism, nutrient transporter up-regulation is compromised and the survival advantage of TSC2−/− MEFs is lost.

It is frequently stated that amino acids regulate mTORC1 signaling independent of TSC2 (51-53). However, amino acid deprivation does not eliminate mTORC1 signaling in TSC2−/− MEFs unless serum is first withdrawn ((16, 54-56) reviewed in (5), (Fig. 2A-C)). In our study, nutrient deprivation was performed in the presence of normal serum to restrict the stresses placed on cells to only amino acid and glucose limitation. Like ceramide treatment, this nutrient restriction protocol did not eliminate cellular access to glucose and glutamine, but did produce sufficient nutrient stress to rapidly silence mTORC1 signaling in TSC2+/+ controls (Figs. 2A&6A). Similar to our results in TSC2-deficient MEFs (Figs. 2A-C and 3A-B), TSC2 knockdown in amino acid-restricted Drosophila S2 cells also maintains p70S6K Thr389 phosphorylation (57) suggesting an evolutionarily conserved role for TSC2 in the response to amino acid limitation. At the same time, the Rag GTPases play a central role in linking mTORC1 activity to amino acid levels by controlling the localization of mTORC1 to lysosomes (16, 17, 58). However, the loss of TSC2 (Fig. 2A-C) or the over-expression of Rheb or Rheb-GTP maintains mTORC1 activity without retaining mTORC1 on the lysosome (16, 17, 59-61). In the case of Rheb over-expression, this result has been hypothesized to reflect Rheb and mTORC1 co-localization to non-lysosomal membranes; co-localization of Rheb and mTORC1 on non-lysosomal membranes is sufficient to maintain mTORC1 activity in the absence of amino acids (17). TSC2 loss might also promote the association of Rheb and mTORC1 on a non-lysosomal membrane. As prior serum withdrawal eliminates mTORC1 activity in amino acid restricted TSC2−/− MEFs (55), serum may regulate the association of Rheb and mTORC1 at this non-lysosomal site through a TSC2-independent mechanism. Antibodies that recognize endogenous Rheb in immunofluorescence microscopy experiments will be important tools to understand how mTORC1 activity is maintained in nutrient-stressed TSC2−/− MEFs without lysosomal localization.

The resistance of TSC2-deficient cells to ceramide-induced death may provide insight into the pathogenesis of the benign hamartomas that form in tuberous sclerosis patients. Ceramide has been deemed a “tumor suppressor lipid” due its key role in maintaining tissue homeostasis (8); the ability to circumvent ceramide-enforced growth limits could help to explain the non-homeostatic growth of TSC1/2-null hamartomas. Intriguingly, hamartomas in tuberous sclerosis patients do not progress to malignant cancers (3). The feedback inhibition of Akt-dependent signaling is likely to partially explain this finding (5, 22-24). Another potential explanation for the lack of progression to malignancy is that TSC2 loss creates a cellular environment unfavorable to the acquisition of the additional mutations necessary for malignant progression. For example, the loss of TSC2 makes cells dependent on the tumor suppressor protein Rb under metabolic stress (62) and loss of p27 increases apoptosis in the renal tumors that form in TSC2+/− mice (36). Consistent with these reports, we found that the introduction of oncogenic Ras restored the sensitivity of TSC2−/− MEFs to ceramide (Fig. 7A). The idea that loss of TSC2 is poorly compatible with the accumulation of oncogenic mutations is also consistent with the observation that few human cancers lack the TSC proteins. It is probably significant that the sustained mTORC1 activity in TSC2−/− MEFs did not prevent proliferative arrest in low nutrient medium (data not shown). The bioenergetic savings associated with cell cycle arrest would ostensibly counterbalance the costs of mTORC1-driven transporter production; oncogenic mutations might eliminate the ATP reserves necessary for mTORC1-dependent adaptations in part by interfering with cell cycle arrest. In conclusion, we have defined a new, adaptive role for mTORC1 signaling in metabolically stressed cells providing novel insights into the pathogenesis of tuberous sclerosis and how oncogenes sensitize cancer cells to therapeutic strategies that target cancer bioenergetics.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

C2-ceramide and staurosporine (Enzo), FTY720 (Cayman Chemical), PP242 and compound C (Chemdea), rapamycin and thapsigargin (EMD), cycloheximide and BCH (Sigma). Anti-murine 4F2hc was from eBioscience or Biolegend; unconjugated 4F2hc antibody was from Biolegend (cat#128202). Antibodies for western blotting were from Cell Signaling Technologies except actin and ATF4 (SC-200) (Santa Cruz) and tubulin (Sigma). TSC2 antibody #4308 was used in all blots except Fig. 2A&D where #3612 was used. Secondary reagents were from LI-COR. The pMSCV-PM retroviral vector to knockdown TSC2 and a control targeting luciferase were kindly provided by Brendan Manning (Harvard) (27). TSC2 plasmid #15478 was from Addgene. pBABE-puro-H-RasV12 was a gift of WeiXing Zong (Stonybrook); pMIT-Rheb-Q64L-HA was provided by Kun Liang Guan (UCSD) via David Fruman (UC Irvine).

Cell culture

Cells were scrupulously maintained at low density (<70% confluence) and discarded after 3 weeks of passage. TSC2+/+ and TSC2−/− MEFs generated by David Kwiatkowski (Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA) were generously provided by Brendan Manning (Harvard). Rictor+/+ and Rictor−/− MEFs were generously provided by David Sabatini (MIT). DMEM lacking glucose and amino acids was made from chemical components and supplemented with 10% FCS. This medium was mixed with standard DMEM (Mediatech) + 10% FCS to produce medium containing 5% or 1% the normal amount of amino acids. Glucose-free medium was purchased (Invitrogen) and 10% dialyzed FCS (Thermo) added. In knockdown experiments, MEF line A was AMPK+/+ MEFs and MEF line B was Bax+/+Bak+/+ MEFs used in previous studies (10). TSC2+/+ MEFs expressing Rheb-Q64L were sorted to be >95% Thy1.1+. Experiments using C2-ceramide were conducted in 1% FCS to reduce ceramide binding to albumin.

Western blotting

Cells were washed twice with cold PBS and lysed on ice with lysis buffer (2% Triton X-100, 80 mM HEPES, 0.4 mM EDTA, pH 6.6) containing Complete protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche), 50 mM sodium fluoride, 100 μM sodium orthovandate, and 50 mM β-glycerophosphate. Equal amounts of protein were loaded/lane of 4-12% NuPAGE gels (Invitrogen). Proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose in NuPAGE transfer buffer (10-15% methanol) and primary antibodies diluted in the blocking buffer recommended by the manufacturer. Blots were scanned and quantified with a LI-COR Odyssey imager. After background subtraction, phospho signals were normalized to total protein signals and then expressed as a percent of untreated controls. eIF2α phosphorylation was monitored as in (63).

Flow cytometry assays

Surface stains were conducted on live cells on ice in buffers containing 0.05% azide; analysis was restricted to viable cells. Surface staining for GLUT1 was conducted using the receptor binding domain of the HTLV-2 Env protein (64).

Nutrient uptake

MEFs were seeded at low density and treated the next day with ceramide. For the last 2 h (amino acids) or 10 min (2-deoxy-glucose) of the incubation period, a mixture of 3H-labeled amino acids or 3H-2-deoxy-glucose (MP Biomedical) was added to 1-2 μCi/ml. To stop uptake, cells were washed twice with ice cold DMEM then lysed. Cell-associated 3H-nutrients were quantified by scintillation counting and normalized to protein content.

ATP assays

MEFs were plated at low density in duplicate 96-well plates 12-16 h prior to treatment with ceramide. ATP levels were measured in cell lysates using an ATP Bioluminescent Assay Kit (Sigma) and an IVIS bioluminescence imager. ATP/mg protein was normalized to an untreated control well to compare between experiments.

Quantitative RT-PCR

Total RNA was isolated using an RNEasy Plus kit (Qiagen); concentration and purity was measured with a NanoDrop 2000C. RNA integrity was verified by electrophoresis. One μg RNA was reverse transcribed using an iScript cDNA Synthesis Kit (Bio-Rad): 5 min at 25°C, 30 min at 48°C, then 5 min at 85°C. One μl of the cDNA product was used in a 20 μl reaction containing 1× SsoAdvanced SYBR Green supermix (Bio-Rad) and 500 nM gene-specific primers. Reactions were run on an Opticon Real-Time PCR Detection System (DNA Engine): 94°C for 10 min followed by 40 cycles of 10 s at 94°C, 15 s at 58°C, and 15 s at 72°C. 4F2 mRNA was normalized to β-actin mRNA. Primers sequences: β-actin FOR: GGCTGTATTCCCCTCCATCG, β-actin REV: CCAGTTGGTAACAATGCCATGT (Primer Bank, http://pga.mgh.harvard.edu/primerbank/index.html); 4F2 (SLC3A2) FOR: GCTCTGAGTTCTTGGTTGC, 4F2 REV: GTACAAGGGTGCATTCATCAG.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported in part by NIH R01-GM089919, American Cancer Society grant 120976-RSG-11-111-01-CDD, W81XWH-11-1-0535 from the Army Medical Research & Materiel Command, and SIIG-1-2007-2008 from the UCI CORCL to ALE. GGG and ANM were supported by Grant Number T32CA009054 from the National Cancer Institute.

REFERENCES

- 1.Dazert E, Hall MN. mTOR signaling in disease. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2011;23:744–55. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2011.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yecies JL, Manning BD. mTOR links oncogenic signaling to tumor cell metabolism. Journal of molecular medicine. 2011;89:221–8. doi: 10.1007/s00109-011-0726-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Curatolo P, Bombardieri R, Jozwiak S. Tuberous sclerosis. Lancet. 2008;372:657–68. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61279-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dibble CC, Elis W, Menon S, Qin W, Klekota J, Asara JM, et al. TBC1D7 is a third subunit of the TSC1-TSC2 complex upstream of mTORC1. Mol Cell. 2012;47:535–46. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huang J, Manning BD. The TSC1-TSC2 complex: a molecular switchboard controlling cell growth. Biochem J. 2008;412:179–90. doi: 10.1042/BJ20080281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Choo AY, Kim SG, Vander Heiden MG, Mahoney SJ, Vu H, Yoon SO, et al. Glucose addiction of TSC null cells is caused by failed mTORC1-dependent balancing of metabolic demand with supply. Mol Cell. 2010;38:487–99. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Inoki K, Zhu T, Guan KL. TSC2 mediates cellular energy response to control cell growth and survival. Cell. 2003;115:577–90. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00929-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ogretmen B, Hannun YA. Biologically active sphingolipids in cancer pathogenesis and treatment. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:604–16. doi: 10.1038/nrc1411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guenther GG, Peralta ER, Rosales KR, Wong SY, Siskind LJ, Edinger AL. Ceramide starves cells to death by downregulating nutrient transporter proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:17402–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802781105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Romero Rosales K, Singh G, Wu K, Chen J, Janes MR, Lilly MB, et al. Sphingolipid-based drugs selectively kill cancer cells by down-regulating nutrient transporter proteins. Biochem J. 2011;439:299–311. doi: 10.1042/BJ20110853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Le Stunff H, Giussani P, Maceyka M, Lepine S, Milstien S, Spiegel S. Recycling of sphingosine is regulated by the concerted actions of sphingosine-1-phosphate phosphohydrolase 1 and sphingosine kinase 2. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:34372–80. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M703329200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ogretmen B, Pettus BJ, Rossi MJ, Wood R, Usta J, Szulc Z, et al. Biochemical mechanisms of the generation of endogenous long chain ceramide in response to exogenous short chain ceramide in the A549 human lung adenocarcinoma cell line. Role for endogenous ceramide in mediating the action of exogenous ceramide. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:12960–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110699200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bhaskar PT, Nogueira V, Patra KC, Jeon SM, Park Y, Robey RB, et al. mTORC1 hyperactivity inhibits serum deprivation-induced apoptosis via increased hexokinase II and GLUT1 expression, sustained Mcl-1 expression, and glycogen synthase kinase 3beta inhibition. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29:5136–47. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01946-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jewell JL, Russell RC, Guan KL. Amino acid signalling upstream of mTOR. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2013 doi: 10.1038/nrm3522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yuan HX, Xiong Y, Guan KL. Nutrient sensing, metabolism, and cell growth control. Mol Cell. 2013;49:379–87. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.01.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sancak Y, Bar-Peled L, Zoncu R, Markhard AL, Nada S, Sabatini DM. Ragulator-Rag complex targets mTORC1 to the lysosomal surface and is necessary for its activation by amino acids. Cell. 2010;141:290–303. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.02.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sancak Y, Peterson TR, Shaul YD, Lindquist RA, Thoreen CC, Bar-Peled L, et al. The Rag GTPases bind raptor and mediate amino acid signaling to mTORC1. Science. 2008;320:1496–501. doi: 10.1126/science.1157535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gwinn DM, Shackelford DB, Egan DF, Mihaylova MM, Mery A, Vasquez DS, et al. AMPK phosphorylation of raptor mediates a metabolic checkpoint. Mol Cell. 2008;30:214–26. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pende M, Um SH, Mieulet V, Sticker M, Goss VL, Mestan J, et al. S6K1(−/−)/S6K2(−/−) mice exhibit perinatal lethality and rapamycin-sensitive 5′-terminal oligopyrimidine mRNA translation and reveal a mitogen-activated protein kinase-dependent S6 kinase pathway. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:3112–24. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.8.3112-3124.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Menon S, Manning BD. Common corruption of the mTOR signaling network in human tumors. Oncogene. 2009;27(Suppl 2):S43–51. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dobrowsky RT, Kamibayashi C, Mumby MC, Hannun YA. Ceramide activates heterotrimeric protein phosphatase 2A. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:15523–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Harrington LS, Findlay GM, Gray A, Tolkacheva T, Wigfield S, Rebholz H, et al. The TSC1-2 tumor suppressor controls insulin-PI3K signaling via regulation of IRS proteins. J Cell Biol. 2004;166:213–23. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200403069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tremblay F, Brule S, Hee Um S, Li Y, Masuda K, Roden M, et al. Identification of IRS-1 Ser-1101 as a target of S6K1 in nutrient- and obesity-induced insulin resistance. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:14056–61. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706517104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shah OJ, Hunter T. Turnover of the active fraction of IRS1 involves raptor-mTOR- and S6K1-dependent serine phosphorylation in cell culture models of tuberous sclerosis. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:6425–34. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01254-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhou H, Summers SA, Birnbaum MJ, Pittman RN. Inhibition of Akt kinase by cell-permeable ceramide and its implications for ceramide-induced apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:16568–75. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.26.16568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schubert KM, Scheid MP, Duronio V. Ceramide inhibits protein kinase B/Akt by promoting dephosphorylation of serine 473. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:13330–5. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.18.13330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang HH, Huang J, Duvel K, Boback B, Wu S, Squillace RM, et al. Insulin stimulates adipogenesis through the Akt-TSC2-mTORC1 pathway. PloS one. 2009;4:e6189. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huang J, Dibble CC, Matsuzaki M, Manning BD. The TSC1-TSC2 complex is required for proper activation of mTOR complex 2. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:4104–15. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00289-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Aronova S, Wedaman K, Aronov PA, Fontes K, Ramos K, Hammock BD, et al. Regulation of ceramide biosynthesis by TOR complex 2. Cell Metab. 2008;7:148–58. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.11.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guertin DA, Stevens DM, Thoreen CC, Burds AA, Kalaany NY, Moffat J, et al. Ablation in mice of the mTORC components raptor, rictor, or mLST8 reveals that mTORC2 is required for signaling to Akt-FOXO and PKCalpha, but not S6K1. Dev Cell. 2006;11:859–71. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Edinger AL, Thompson CB. An activated mTOR mutant supports growth factor-independent, nutrient-dependent cell survival. Oncogene. 2004;23:5654–63. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Edinger AL, Thompson CB. Akt maintains cell size and survival by increasing mTOR-dependent nutrient uptake. Mol Biol Cell. 2002;13:2276–88. doi: 10.1091/mbc.01-12-0584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Matsumoto S, Bandyopadhyay A, Kwiatkowski DJ, Maitra U, Matsumoto T. Role of the Tsc1-Tsc2 complex in signaling and transport across the cell membrane in the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Genetics. 2002;161:1053–63. doi: 10.1093/genetics/161.3.1053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kanai Y, Segawa H, Miyamoto K, Uchino H, Takeda E, Endou H. Expression cloning and characterization of a transporter for large neutral amino acids activated by the heavy chain of 4F2 antigen (CD98) J Biol Chem. 1998;273:23629–32. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.37.23629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Park NS, Kim SG, Kim HK, Moon SY, Kim CS, Cho SH, et al. Characterization of amino acid transport system L in HTB-41 human salivary gland epidermoid carcinoma cells. Anticancer Res. 2008;28:2649–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Short JD, Houston KD, Dere R, Cai SL, Kim J, Johnson CL, et al. AMP-activated protein kinase signaling results in cytoplasmic sequestration of p27. Cancer Res. 2008;68:6496–506. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-5756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lacher MD, Pincheira R, Zhu Z, Camoretti-Mercado B, Matli M, Warren RS, et al. Rheb activates AMPK and reduces p27Kip1 levels in Tsc2-null cells via mTORC1-independent mechanisms: implications for cell proliferation and tumorigenesis. Oncogene. 2010;29:6543–56. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhou G, Myers R, Li Y, Chen Y, Shen X, Fenyk-Melody J, et al. Role of AMP-activated protein kinase in mechanism of metformin action. J Clin Invest. 2001;108:1167–74. doi: 10.1172/JCI13505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wek RC, Jiang HY, Anthony TG. Coping with stress: eIF2 kinases and translational control. Biochem Soc Trans. 2006;34:7–11. doi: 10.1042/BST20060007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bhattacharyya SN, Habermacher R, Martine U, Closs EI, Filipowicz W. Relief of microRNA-mediated translational repression in human cells subjected to stress. Cell. 2006;125:1111–24. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.04.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fernandez J, Yaman I, Mishra R, Merrick WC, Snider MD, Lamers WH, et al. Internal ribosome entry site-mediated translation of a mammalian mRNA is regulated by amino acid availability. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:12285–91. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M009714200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bain PJ, LeBlanc-Chaffin R, Chen H, Palii SS, Leach KM, Kilberg MS. The mechanism for transcriptional activation of the human ATA2 transporter gene by amino acid deprivation is different than that for asparagine synthetase. J Nutr. 2002;132:3023–9. doi: 10.1093/jn/131.10.3023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gazzola RF, Sala R, Bussolati O, Visigalli R, Dall’Asta V, Ganapathy V, et al. The adaptive regulation of amino acid transport system A is associated to changes in ATA2 expression. FEBS Lett. 2001;490:11–4. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)02126-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gaccioli F, Huang CC, Wang C, Bevilacqua E, Franchi-Gazzola R, Gazzola GC, et al. Amino acid starvation induces the SNAT2 neutral amino acid transporter by a mechanism that involves eukaryotic initiation factor 2alpha phosphorylation and cap-independent translation. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:17929–40. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M600341200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kang YJ, Lu MK, Guan KL. The TSC1 and TSC2 tumor suppressors are required for proper ER stress response and protect cells from ER stress-induced apoptosis. Cell Death Differ. 2011;18:133–44. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2010.82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ng S, Wu YT, Chen B, Zhou J, Shen HM. Impaired autophagy due to constitutive mTOR activation sensitizes TSC2-null cells to cell death under stress. Autophagy. 2011;7:1173–86. doi: 10.4161/auto.7.10.16681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Parkhitko A, Myachina F, Morrison TA, Hindi KM, Auricchio N, Karbowniczek M, et al. Tumorigenesis in tuberous sclerosis complex is autophagy and p62/sequestosome 1 (SQSTM1)-dependent. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:12455–60. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1104361108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Klionsky DJ, Abdalla FC, Abeliovich H, Abraham RT, Acevedo-Arozena A, Adeli K, et al. Guidelines for the use and interpretation of assays for monitoring autophagy. Autophagy. 2012;8:445–544. doi: 10.4161/auto.19496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Brugarolas JB, Vazquez F, Reddy A, Sellers WR, Kaelin WG., Jr. TSC2 regulates VEGF through mTOR-dependent and -independent pathways. Cancer Cell. 2003;4:147–58. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00187-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kaper F, Dornhoefer N, Giaccia AJ. Mutations in the PI3K/PTEN/TSC2 pathway contribute to mammalian target of rapamycin activity and increased translation under hypoxic conditions. Cancer Res. 2006;66:1561–9. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Duran RV, Hall MN. Regulation of TOR by small GTPases. EMBO Rep. 2012;13:121–8. doi: 10.1038/embor.2011.257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kim J, Guan KL. Amino acid signaling in TOR activation. Annu Rev Biochem. 2011;80:1001–32. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-062209-094414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Avruch J, Long X, Ortiz-Vega S, Rapley J, Papageorgiou A, Dai N. Amino acid regulation of TOR complex 1. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2009;296:E592–602. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.90645.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Shaw RJ, Bardeesy N, Manning BD, Lopez L, Kosmatka M, DePinho RA, et al. The LKB1 tumor suppressor negatively regulates mTOR signaling. Cancer Cell. 2004;6:91–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2004.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nobukuni T, Joaquin M, Roccio M, Dann SG, Kim SY, Gulati P, et al. Amino acids mediate mTOR/raptor signaling through activation of class 3 phosphatidylinositol 3OH-kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:14238–43. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506925102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Roccio M, Bos JL, Zwartkruis FJ. Regulation of the small GTPase Rheb by amino acids. Oncogene. 2006;25:657–64. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gao X, Zhang Y, Arrazola P, Hino O, Kobayashi T, Yeung RS, et al. Tsc tumour suppressor proteins antagonize amino-acid-TOR signalling. Nat Cell Biol. 2002;4:699–704. doi: 10.1038/ncb847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kim E, Goraksha-Hicks P, Li L, Neufeld TP, Guan KL. Regulation of TORC1 by Rag GTPases in nutrient response. Nat Cell Biol. 2008;10:935–45. doi: 10.1038/ncb1753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kim SG, Hoffman GR, Poulogiannis G, Buel GR, Jang YJ, Lee KW, et al. Metabolic Stress Controls mTORC1 Lysosomal Localization and Dimerization by Regulating the TTT-RUVBL1/2 Complex. Mol Cell. 2013;49:172–85. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tee AR, Manning BD, Roux PP, Cantley LC, Blenis J. Tuberous sclerosis complex gene products, Tuberin and Hamartin, control mTOR signaling by acting as a GTPase-activating protein complex toward Rheb. Curr Biol. 2003;13:1259–68. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(03)00506-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Inoki K, Li Y, Xu T, Guan KL. Rheb GTPase is a direct target of TSC2 GAP activity and regulates mTOR signaling. Genes Dev. 2003;17:1829–34. doi: 10.1101/gad.1110003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Li B, Gordon GM, Du CH, Xu J, Du W. Specific killing of Rb mutant cancer cells by inactivating TSC2. Cancer Cell. 2010;17:469–80. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.03.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Teske BF, Baird TD, Wek RC. Methods for analyzing eIF2 kinases and translational control in the unfolded protein response. Methods Enzymol. 2011;490:333–56. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-385114-7.00019-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Manel N, Kim FJ, Kinet S, Taylor N, Sitbon M, Battini JL. The ubiquitous glucose transporter GLUT-1 is a receptor for HTLV. Cell. 2003;115:449–59. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00881-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]