Abstract

Flavones are abundant in parsley and celery and possess unique anti-inflammatory properties in vitro and in animal models. However, their bioavailability and bioactivity depend in part on the conjugation of sugars and other functional groups to the flavone core. The effects of juice extraction, acidification, thermal processing, and endogenous enzymes on flavone glycoside profile and concentration in both parsley and celery were investigated. Parsley yielded 72% juice with 64% of the total flavones extracted, whereas celery yielded 79% juice with 56% of flavones extracted. Fresh parsley juice averaged 281 mg flavones/100 g and fresh celery juice, 28.5 mg/100 g. Flavones in steamed parsley and celery were predominantly malonyl apiosylglucoside conjugates, whereas those in fresh samples were primarily apiosylglucoside conjugates; this was apparently the result of endogenous malonyl esterases. Acidification and thermal processing of celery converted flavone apiosylglucosides to flavone glucosides, which may affect the intestinal absorption and metabolism of these compounds.

Keywords: flavones, celery, parsley, juice, apigenin, mass balance

INTRODUCTION

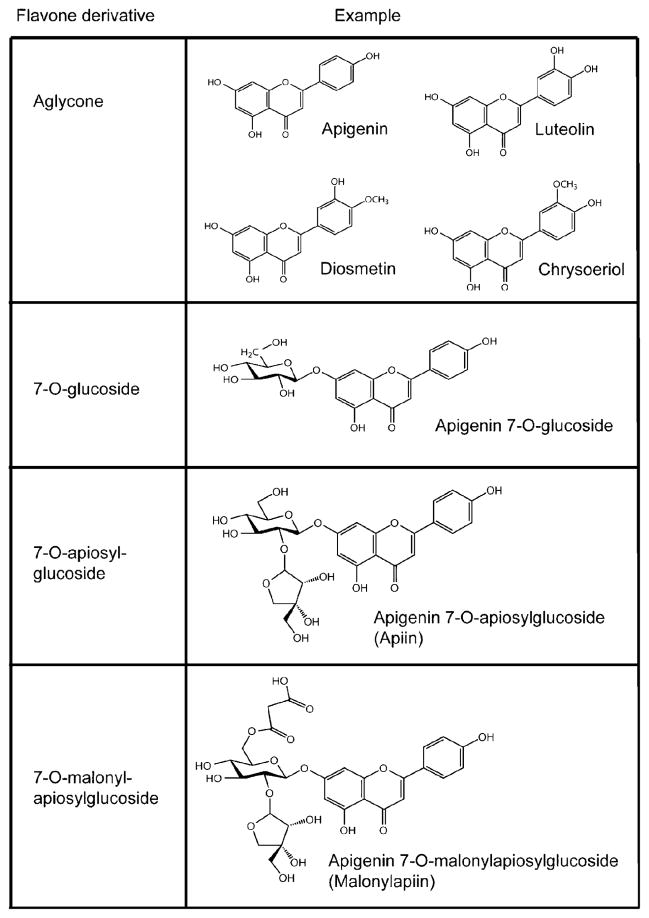

Flavones are a class of flavonoids found in a variety of fruits and vegetables and are most abundant in artichoke heads, kumquats, parsley, and celery.1–3 In their native forms they are conjugated to sugars, simple acids (acetyl and malonyl), and cinnamic acids (Figure 1) rather than existing as aglycones. In vitro studies demonstrate that the flavone apigenin inhibits human lung, colon, breast, prostate, brain, and skin cancer cells;4–8 tongue cancer;9 and leukemia.10 Apigenin and luteolin also reduce monocyte adhesion to LDL in vitro, showing potential to prevent one of the initial stages of atherosclerosis.11 In addition, animal studies with flavones demonstrate the ability to attenuate the inflammatory response.12,13

Figure 1.

Structures of common flavone derivatives.

The glycosylation of flavones in food is important because intestinal hydrolysis of flavonoid glycosides varies according to the sugars and other functional groups attached to the flavone core. Similar to other flavonoids, flavone glucosides can be hydrolyzed by β-glucosidase in the small intestine to their respective aglycones,14 which can be absorbed in the small intestine and subsequently glucuronidated and sulfated by the small intestine and liver before reaching systemic circulation.15,16 In contrast, flavonoid glycosides with disaccharide and malonyl moieties are resistant to intestinal β-glucosidase relative to their simple glucoside counterparts, potentially limiting their bioavailability.14 Therefore, determining the native glycosides is potentially useful when functional foods are developed.

Using a Caco-2 model, apigenin and luteolin aglycones were more readily absorbed into intestinal cells and 10 times more of the aglycone forms were transported across the intestinal epithelium than apigenin 6-C-glucoside or luteolin 7-O-glucoside.17 Experiments with isolated rat small intestine showed a similar pattern for isoflavones. Nearly twice as much genistein and daidzein (aglycones) was absorbed and transported to the basolateral side than their 7-O-glucoside counterparts, and the malonyl glucoside conjugates were absorbed in only trace amounts.18

A review of the literature and a screening of a variety of fruits and vegetables revealed that parsley and celery were particularly rich in flavones occurring as their apiosylglucosides.19,20 On the basis of their flavone concentrations and the biological activity of flavones previously cited, parsley and celery can potentially be used in a food-based approach to the prevention of chronic disease. In the current study, the objective is to determine how juice processing, endogenous enzymes, acidification, and thermal processing affect the stability and glycosylation of flavones in parsley and celery. Flavone glycosides were first identified and quantified in fresh and steamed parsley and celery, in pomace, and in juice after extraction. Flavones were then quantified in juices after acidification and thermal processing. These processes were optimized to produce flavone derivatives that may have enhanced bioavailability and efficacy.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chinese celery (Apium graveolens L., Apiaceae) and Italian parsley (Petroselinum crispum Mill., Apiaceae) were purchased from local grocery stores in Columbus, OH. Chrysoeriol and luteolin 7-O-glucoside were purchased from Extrasynthese (Genay, France); apigenin, luteolin, and citric acid monohydrate from Sigma (St. Louis, MO); and diosmetin and apigenin 7-O-glucoside from Chromadex (Irvine, CA). All other reagents were from Fisher Scientific (Fair Lawn, NJ).

Effects of Steaming on Flavone Conjugation in Parsley and Celery

To test for endogenous enzymes and possible effects on flavones, celery leaves or parsley were steamed prior to maceration to inactivate enzymes and compared to unheated control samples. All samples were prepared by first rinsing and spin-drying 5 g of fresh celery leaves or parsley. Steamed samples were held in a sieve over 1 L of boiling water for 10 min to inactivate endogenous enzymes. Steamed or untreated celery leaves and parsley were then ground in liquid nitrogen with a mortar and pestle and incubated at 37 or 20 °C for 3 h to allow any remaining endogenous enzymes to act on flavonoids in the samples. Experiments were done in triplicate and samples extracted as described below.

Juice Extraction and Processing

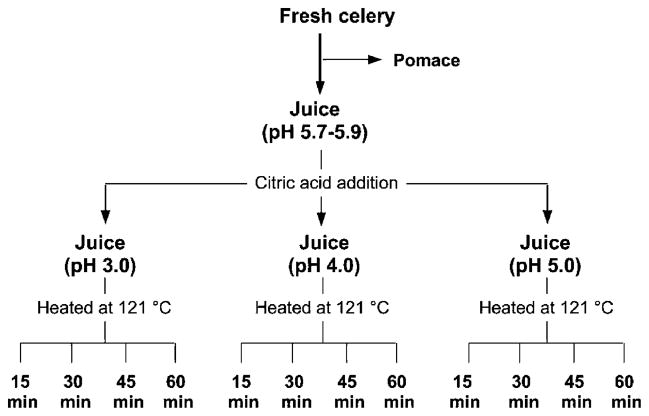

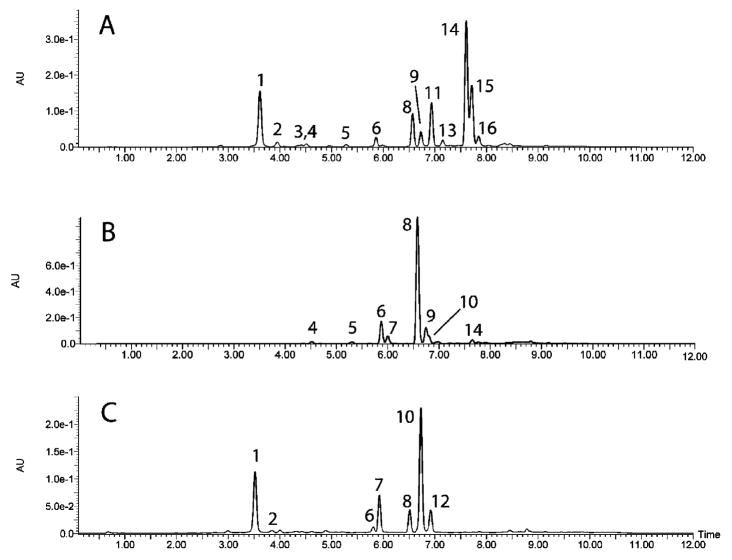

Juicing experiments were carried out in triplicate, and the steps for processing are outlined in Figure 2. Celery and parsley stalks and leaves were used for juice extraction with an Omega 8006 masticating juicer (Harrisburg, PA). To determine the effects of pH and heat on flavones during processing, juice was divided into two lots with one left at its original pH (5.6–6.2) and the other acidified to pH 4.0 with citric acid. Each lot was then processed at 100 °C for 2 or 30 min in a boiling water bath or at 121 °C for 30 min in a Splendid pressure cooker (Fagor America, Lyndhurst, NJ). To further explore the effects of heat and pH on flavone stability and profiles, celery juices were acidified to pH 3.0, 4.0, or 5.0 and heated at 121 °C for 15, 30, 45, or 60 min (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Processes for juicing, acidification, and thermal processing of parsley and celery.

Figure 3.

Flow diagram for acidification and thermal processing of celery juice.

Flavone Extraction

Steamed and untreated samples were cooled on ice after incubation, and 0.5 g of each was extracted. To assess the mass balance of flavones in parsley and celery during processing (Figure 2), duplicate samples were lyophilized and 0.1 g of each was extracted. Acidified celery juices were processed at 121 °C (Figure 3), and 1.0 g was extracted after processing and cooling. All samples were extracted three times with 2.5 mL of 70% (v/v) aqueous methanol, and the combined supernatants were analyzed by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC).

Identification by HPLC–Mass Spectrometry

Flavone glycosides were tentatively identified by electrospray mass spectrometry (ESI-MS) with a QTOF Premier (Micromass, Manchester, U.K.) using accurate mass and fragmentation patterns in positive and negative ionization modes. Source parameters included the following: capillary voltage, 2.8 kV in negative mode and 3.2 kV in positive mode; cone, 35 V; source block, 110 °C, collision energy, 8 V. Desolvation gas was delivered at 600 L/h and 450 °C, cone gas at 50 L/h, and collision-induced dissociation gas at 2.5 × 10−3 mBar (argon). Sodium formate was used to calibrate and leucine-enkephalin as a lockspray reference. MSE experiments were applied where alternating low and high collision energies were used to view precursors and fragments in a single run. MS/MS scans were then used to confirm parent–daughter relationships.

HPLC Analysis

Analysis of celery, parsley, and juice samples was conducted by HPLC. Apigenin, luteolin, chrysoeriol, diosmetin, apigenin 7-O-glucoside, and apigenin 7-O-apiosylglucoside standards were used to identify compounds by UV spectra and retention times. Other flavone glycosides were identified by ESI-MS as described above. For quantification, the HPLC system included a Waters 2695 separation module, a 2996 photodiode array detector, a Symmetry C18 column (3.5 μm, 4.6 × 75 mm), and Empower software (Waters Corp., Milford, MA). The mobile phase consisted of 0.1% formic acid in water (A) and 0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile (B), and the column was maintained at 30 °C. For fresh and steamed parsley and celery, the following gradient method was used: 0–1 min, 5–19% B; 1–6.5 min, 19% B; 6.5–7 min, 19–20% B; 7–13 min, 20% B; 13–15 min, 20–55% B; 15–18 min, 55–80% B; 18–20 min, 80–100% B; 20–22 min, 100% B; 22–25 min, 5% B. Juice samples were separated with the following gradient: 0–1 min, 5–18% B; 1–13 min, 18% B; 13–15 min, 18–100% B; 15–17 min, 100% B; 17–20 min, 5% B. Peak areas were measured at 338 nm for apigenin and at 350 nm for luteolin, diosmetin, and chrysoeriol. Because the flavone glycosides in this study share the same chromophore as their aglycone counterparts, concentrations of all flavones were determined with aglycone standard curves.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed with R 2.11 for Windows (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) using one- or two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) blocking for different batches of celery or parsley. Post hoc comparisons were done with Tukey’s HSD.

RESULTS

Identification of Flavones by HPLC-MS

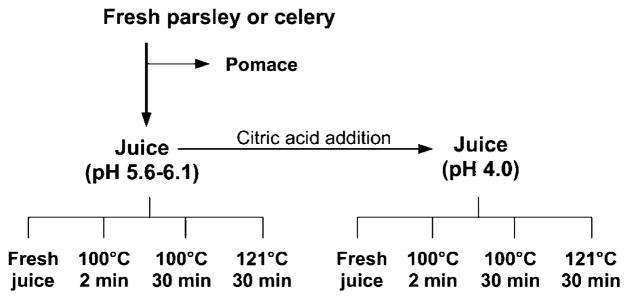

Representative HPLC chromatograms for steamed celery, fresh celery, and acidified, thermally processed celery juice are provided in Figure 4. Peaks were identified by retention time (RT), UV– visible absorbance (λmax), mass of parent ions in positive and negative modes ([M + H]+ and [M − H]−), and mass of aglycone ions after fragmentation ([A + H]+ and [A − H]−) (Table 1). Chlorogenic and coumaroylquinic acids were detected only as negative ions, and flavone malonyl glucosides were detected as acetyl glucosides in negative mode due to decarboxylation (Table 1). The compounds identified in fresh and steamed celery and parsley have been previously reported,19,20 but apigenin 7-O-glucoside in acidified, thermally processed juice samples is newly identified (Figure 4C; Table 1).

Figure 4.

HPLC chromatograms of celery extracts: (A) celery steamed for 10 min, macerated, and incubated for 3 h at 37 °C; (B) celery macerated and incubated for 3 h at 37 °C; (C) celery juice acidified to pH 3.0 and processed for 60 min at 121 °C.

Table 1.

Tentative Peak Assignments for Chromatograms of Celery Extracts Based on HPLC-MS Data

| peak | RTa (min) | λmax (nm) | [M + H]+/[M − H]−b (m/z) | [A + H]+/[A − H]−c (m/z) | identification |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3.59 | 326 | −/353 | −/191 | chlorogenic acid |

| 2 | 3.92 | 327 | −/353 | −/191 | chlorogenic acid |

| 3 | 4.41 | 312 | −/353 | −/191 | chlorogenic acid |

| 4 | 4.51 | 312 | −/337 | −/191 | coumaroylquinic acid |

| 5 | 5.27 | 306 | −/337 | −/191 | coumaroylquinic acid |

| 6 | 5.85 | 255, 349 | 581/579 | 287/285 | luteolin 7-O-apiosylglucoside |

| 7 | 6.00 | 255, 349 | 449/447 | 287/285 | luteolin 7-O-glucoside |

| 8 | 6.55 | 267, 338 | 565/563 | 271/269 | apigenin 7-O-apiosylglucoside |

| 9 | 6.70 | 253, 348 | 595/593 | 301/299 | chrysoeriol 7-O-apiosylglucoside |

| 10 | 6.80 | 267, 338 | 433/431 | 271/269 | apigenin 7-O-glucoside |

| 11 | 6.92 | 254, 348 | 667/621d | 287/285 | luteolin 7-O-malonyl apiosylglucoside |

| 12 | 6.99 | 253, 347 | 463/461 | 301/299 | chrysoeriol 7-O-glucoside |

| 13 | 7.14 | 253, 345 | 535/489d | 287/285 | luteolin 7-O-malonyl glucoside |

| 14 | 7.59 | 267, 337 | 651/605d | 271/269 | apigenin 7-O-malonyl apiosylglucoside |

| 15 | 7.70 | 253, 345 | 681/635d | 301/299 | chrysoeriol 7-O-malonyl apiosylglucoside A |

| 16 | 7.83 | 253, 348 | 681/635d | 301/299 | chrysoeriol 7-O-malonyl apiosylglucoside B |

Retention time.

[M + H]+/[M − H]− positive and negative parent ions. Chlorogenic and coumaroylquinic acids were detected only in negative mode.

[A + H]+/[A − H]− positive and negative aglycone ions.

Malonyl glycosides were detected as acetyl glycosides due to decarboxylation in negative mode.

Effects of Steaming on Flavone Conjugation in Parsley and Celery

To evaluate the effects of endogenous enzymes on flavone conjugation, celery leaves and parsley were steamed for 10 min prior to incubation and compared with fresh celery and parsley samples. When celery leaves or parsley were steamed before incubation at 37 or 20 °C for 3 h, significantly greater amounts of flavone glycosides were present as malonyl apiosylglucosides and significantly less were present as apiosylglucosides compared to fresh samples (Tables 2 and 3). Fresh celery leaves and parsley contained predominantly flavone apiosylglucosides, and there were no significant differences associated with incubation temperature. There were no significant differences in total flavone concentrations between any of the treatments (Tables 2 and 3).

Table 2.

Concentrations of Flavone Derivatives in Steamed and Fresh Parsley after Maceration and Incubation for 3 ha

| conditions | apiosylglucoside

|

malonyl apiosylglucoside

|

total flavonesb | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| apigenin | diosmetin | apigenin | diosmetin | ||

| steamed, incubated at 37 °C, 3 h | 78.5 ± 34.7 a | 18.7 ± 8.4 a | 171 ± 43.5 a | 39.2 ± 10.5 a | 340 ± 48.9 a |

| fresh, incubated at 37 °C, 3 h | 255 ± 24.8 b | 58.5 ± 4.1 b | 7.0 ± 1.4 b | 0.0 ± 0.0 b | 338 ± 29.0 a |

| fresh, incubated at 20 °C, 3 h | 264 ± 22.8 b | 60.2 ± 1.7 b | 7.7 ± 1.0 b | 0.0 ± 0.0 b | 348 ± 23.5 a |

Values within each column without a common letter differ significantly (p < 0.05). Flavone quantities are expressed as aglycone equivalents (mg/100 g fresh weight). Data are the mean ± SD, n = 3. ND, not detected.

Includes minor flavone glycosides such as acetyl glucosides.

Table 3.

Concentrations of Flavone Derivatives in Steamed and Fresh Celery Leaves after Maceration and Incubation for 3 ha

| conditions | apiosylglucoside

|

malonyl apiosylglucoside

|

total flavonesb | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| luteolin | apigenin | chrysoeriol | luteolin | apigenin | chrysoeriol | ||

| steamed, incubated at 37 °C, 3 h | 9.0 ± 1.4 a | 16.3 ± 1.6 a | 11.6 ± 1.0 a | 31.0 ± 4.9 a | 78.8 ± 9.5 a | 45.2 ± 5.7 a | 210 ± 24.6 a |

| fresh, incubated at 37 °C, 3 h | 13.3 ± 3.7 a | 130 ± 4.7 b | 75.2 ± 6.2 b | 0.0 ± 0.0 b | 3.8 ± 2.1 b | 3.4 ± 3.6 b | 226 ± 11.7 a |

| fresh, incubated at 20 °C, 3 h | 30.6 ± 2.4 b | 128 ± 2.2 b | 71.1 ± 4.8 b | 0.0 ± 0.0 b | 6.4 ± 0.2 b | 7.4 ± 0.2 b | 244 ± 6.9 a |

Values within each column without a common letter differ significantly (p < 0.05). Flavone quantities are expressed as aglycone equivalents (mg/100 g fresh weight). Data are the mean ± SD, n = 3. ND, not detected.

Includes minor flavone glycosides such as acetylglucosides.

Mass Balance of Flavones during Juice Processing

Parsley yielded 72% juice (w/w) with similar amounts of apigenin and diosmetin glycosides. Whereas the majority of apigenin, diosmetin, and total flavones were found in the juice after extraction, nearly one-third of the flavones were retained in the pomace (Table 4). Celery yielded 79% juice, and slightly more apigenin, luteolin, and chrysoeriol were found in the juice than in the pomace (Table 5). In fresh celery and juice, apigenin glycosides were the most abundant, accounting for over half of all flavones.

Table 4.

Yield, Moisture, and Flavones in Fresh Parsley, Pomace, and Juicea

| step | yield (g) | moisture (%) | total apigenin (mg) | total diosmetin (mg) | total flavones (mg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| fresh parsley | 100 | 88.1 ± 0.8 | 178 ± 14.5 | 179 ± 94.7 | 357 ± 97.0 |

| parsley juice | 71.9 ± 2.8 | 91.8 ± 0.5 | 92.7 ± 13.0 | 108 ± 62.7 | 200 ± 75.6 |

| parsley pomace | 25.2 ± 1.0 | 78.6 ± 1.5 | 56.8 ± 4.1 | 55.9 ± 30.2 | 113 ± 26.3 |

Flavone quantities are expressed as aglycone equivalents. Data are the mean ± SD, n = 3.

Table 5.

Yield, Moisture, and Flavones in Fresh Celery (Stalks and Leaves), Juice, and Pomacea

| step | yield (g) | moisture (%) | total apigenin (mg) | total luteolin (mg) | total chrysoeriol (mg) | total flavones (mg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| fresh celery | 100 | 93.1 ± 0.6 | 41.1 ± 9.3 | 16.7 ± 5.5 | 13.0 ± 4.0 | 70.8 ± 18.9 |

| celery juice | 79.1 ± 0.4 | 95.4 ± 0.1 | 13.4 ± 1.4 | 4.9 ± 0.2 | 4.3 ± 0.4 | 22.5 ± 1.8 |

| celery pomace | 18.8 ± 0.3 | 83.7 ± 0.6 | 11.1 ± 0.3 | 3.2 ± 0.3 | 3.6 ± 0.2 | 18.0 ± 0.8 |

Flavone quantities are expressed as aglycone equivalents. Data are the mean ± SD, n = 3.

Effects of pH and Heat Processing on Flavone Conjugation in Parsley and Celery Juices

To determine the effects of pH and thermal processing on parsley and celery juices, untreated juices (pH 5.6–6.2) were compared with acidified juices (pH 4.0) and were heated at 100 or 121 °C for 2–30 min. In parsley juice apigenin concentrations averaged 116–140 mg/100 g fresh weight (FW); diosmetin, 130–158 mg/100 g FW; and total flavones 247–298 mg/100 g FW. There were no significant differences associated with pH and thermal treatments in parsley juice. Celery juice acidified and heated to 121 °C for 30 min had higher apigenin concentrations than those at their native pH, and juice heated to 100 °C for 30 min had higher luteolin concentrations than nonacidified juice heated for only 2 min (data not shown). Flavone apiosylglucosides were most abundant in all juices, followed by malonyl apiosylglucosides. Parsley and celery juices acidified to pH 4.0 and heated at 121 °C for 30 min showed 10–15% conversion of apiosylglucosides to simple glucosides, whereas flavone 7-O-glucosides were not detected in juices left at their native pH and heated at 121 °C (data not shown).

Although parsley juice had higher flavone concentrations than celery juice, celery is more palatable and more economical for juicing. To further explore the effects of processing conditions on the stability of flavone glycosides, celery juice was acidified to pH 3.0, 4.0, or 5.0 and heated at 121 °C for 15–60 min. After variation between lots of celery had been taken into consideration, the pH 3.0 and 4.0 juices had slightly higher total flavone concentrations than the pH 5.0 juices (data not shown). There were no significant differences associated with heating times.

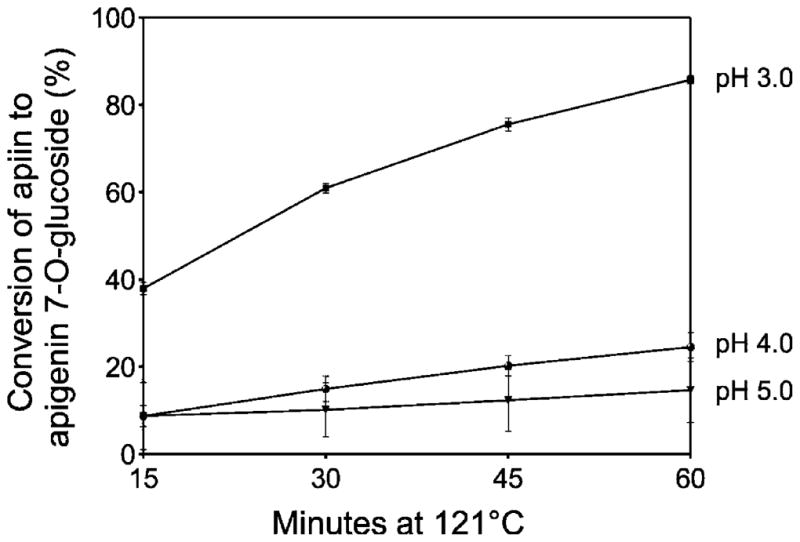

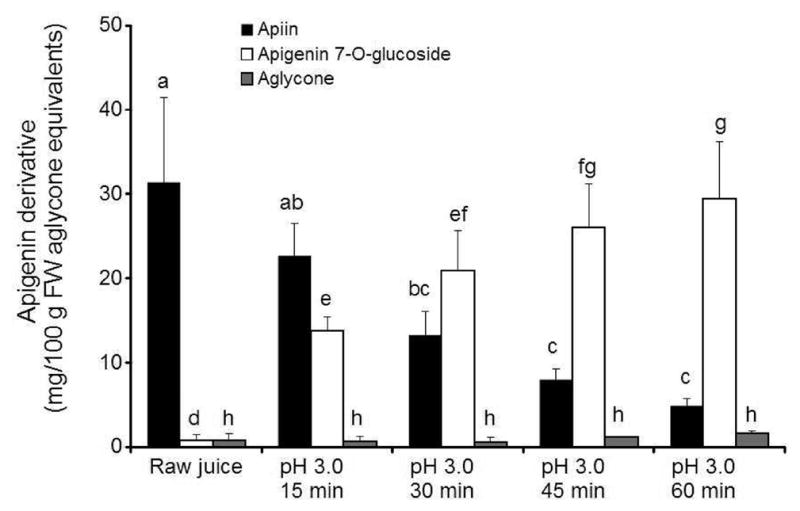

As apigenin glycosides were the most abundant flavones in celery, they were used to represent the change in profiles with acidification and thermal processing. The conversion of apiin to apigenin 7-O-glucoside in celery juice acidified to pH 5.0 or 4.0 increased slightly with time, averaging 15% in pH 5.0 juice and 24% in pH 4.0 juice after 60 min (Figure 5). The most striking conversion of flavone glycosides occurred in juice acidified to pH 3.0. The conversion to apigenin 7-O-glucoside increased rapidly over time, from 38% after 15 min at 121 °C to 83% after 60 min. There was no significant conversion of apigenin glycosides to aglycones and no loss of total apigenin derivatives after acidification and thermal processing (Figure 6).

Figure 5.

Conversion of apiin to apigenin 7-O-glucoside in celery juice. Juices were processed at pH 3.0, 4.0, or 5.0 at 121 °C for 15–60 min. Data are the mean ± SD, n = 3.

Figure 6.

Profile of apigenin derivatives in celery juice. Raw untreated juice was compared with juice processed at pH 3.0 at 121 °C for 15–60 min. Data are the mean ± SD, n = 3. Values within each treatment group without a common letter differ (p < 0.05). FW, fresh weight.

DISCUSSION

In all of the juice samples analyzed, flavone apiosylglucosides were the predominant flavonoids and malonyl apiosylglucosides were minor or undetectable. When celery leaves or parsley was steamed, significantly greater amounts of flavone glycosides were present as malonyl apiosylglucosides and significantly less were present as apiosylglucosides compared to fresh samples (Tables 2 and 3). Given the rapid loss of malonyl groups from the compounds in fresh juices and the preservation of these groups after steaming, this conversion of flavone glycosides is likely due to enzymatic activity. Malonyl esterase activity has previously been reported in parsley,20 but no reports of similar activity in celery were found after a review of the literature and the BRENDA enzyme database.21 Demalonylation of flavone glycosides can occur after oven-drying22 or after the extraction process, as has been noted with other flavonoid glycosides.23 Heating soy products can lead to demalonlyation (high moisture) or decarboxylation (low moisture) of isoflavone malonyl glucosides,24 but the parsley and celery in our experiments retained this functional group after steaming.

With a masticating juicer, parsley yielded 72% juice yield (w/w) and celery yielded 79%. The majority of individual and total flavones were found in parsley and celery juices after extraction. However, pomace had higher flavone concentrations than juice, particularly from celery (Tables 4 and 5). This is similar to the retention of flavonoids in the pomace of other fruits and vegetables after juicing, including artichoke hearts25 and apples.26

Acidifying parsley and celery juices to pH 4.0 and heating at 100 or 121 °C for up to 30 min did not significantly affect total flavone concentrations. These results were similar to those of most other studies on juices. Thermal processing at 95 °C for up to 1 min had little effect on flavonoid concentrations in orange juice,27,28 and processing at 88 °C for up to 30 min had no effect on total flavonoids in tomato juice.29 Heating grape juice at 95 °C for 15 min did not degrade anthocyanins.30 In contrast, up to 49% of isoflavones were lost from soybeans when they were boiled for 20 min during tempeh production.31

After acidifying celery juice to pH 3.0, 4.0, or 5.0 and heating at 121 °C for 15–60 min, there was no effect of processing times on total flavone concentrations in this study. Few studies have compared the effects of extensive thermal processing on flavonoids in foods. Isoflavones in soy converted from glycosides to aglycone during extrusion at 110–150 °C, but no loss of total isoflavones was observed.32 Others have tested the effects of heat and pH treatments on pure flavonoid glycosides with varied results. Quercetin and quercetin rutinoside standards boiled at 100 °C for up to 5 h at pH 5 and 8 showed different stabilities, and both were more stable in the absence of oxygen. Both compounds were more stable at pH 5, and the quercetin glycoside was more stable than the aglycone.33 Daidzein and genistein (aglycone) standards both degraded when heated at 120 °C for 20 min, but the effect varied with pH. Daidzein was more stable at pH 9, whereas genistein was more stable at pH 7.34

Although the concentration of total flavones in celery juice was generally stable after heat processing, the conversion of apiin to apigenin 7-O-glucoside increased rapidly at 121 °C over time at pH 3.0, reaching 83% after 60 min (Figure 6). Previous investigations suggested that this deconjugation to a simple flavonoid glucoside may improve absorption. In human subjects, converting hesperetin 7-O-rhamnosylglucoside to hesperetin 7-O-glucoside in orange juice increased peak hesperetin plasma concentrations 4-fold.35 The flavonoid apiosylglucosides in parsley and celery are similar to the flavonoid rhamnosylglucosides in orange juice in that they consist of a disaccharide group attached at the same position on the flavonoid core. Experiments with humans fed parsley and celery containing flavone apiosylglucosides resulted in tmax values of 7–8 h,36,37 compared to <1 h for those fed simple flavone glucoside.38 These data support the hypothesis that flavone apiosylglucosides are absorbed in the colon, whereas simple glucosides such as apigenin 7-O-glucoside are absorbed in the small intestine.

The bioavailability of flavones, particularly abundant in parsley and celery, depends on both the dose and the conjugation of these compounds to sugars and other functional groups. The current study shows that during juice processing, a substantial portion of the flavones from parsley and celery are retained in the pomace. Perhaps more importantly, total flavone concentrations changed little, but the profile of flavone glycosides in the resulting juices was modified by endogenous enzymes, pH, and thermal processing. Extended thermal processing at low pH resulted in the conversion of apigenin apiosylglucoside to apigenin glucoside, potentially modulating intestinal absorption and metabolism.

Abbreviations Used

- ESI-MS

electrospray mass spectrometry

- FW

fresh weight

- HPLC

high-performance liquid chromatography

- RT

retention time

- tmax

time of maximum plasma concentration

References

- 1.Azzini E, Bugianesi R, Romano F, Di Venere D, Miccadei S, Durazzo A, Foddai MS, Catasta G, Linsalata V, Maiani G. Absorption and metabolism of bioactive molecules after oral consumption of cooked edible heads of Cynara scolymus L. (cultivar Violetto di Provenza) in human subjects: a pilot study. Br J Nutr. 2007;97:963–969. doi: 10.1017/S0007114507617218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Justesen U, Knuthsen P, Leth T. Quantitative analysis of flavonols, flavones, and flavanones in fruits, vegetables and beverages by high-performance liquid chromatography with photo-diode array and mass spectrometric detection. J Chromatogr, A. 1998;799:101–110. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(97)01061-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sakakibara H, Honda Y, Nakagawa S, Ashida H, Kanazawa K. Simultaneous determination of all polyphenols in vegetables, fruits, and teas. J Agric Food Chem. 2003;51:571–581. doi: 10.1021/jf020926l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Manthey JA, Guthrie N. Antiproliferative activities of citrus flavonoids against six human cancer cell lines. J Agric Food Chem. 2002;50:5837–5843. doi: 10.1021/jf020121d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gupta S, Afaq F, Mukhtar H. Involvement of nuclear factor-kappa B, Bax and Bcl-2 in induction of cell cycle arrest and apoptosis by apigenin in human prostate carcinoma cells. Oncogene. 2002;21:3727–3738. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Piantelli M, Rossi C, Iezzi M, La Sorda R, Iacobelli S, Alberti S, Natali PG. Flavonoids inhibit melanoma lung metastasis by impairing tumor cells endothelium interactions. J Cell Physiol. 2006;207:23–29. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mak P, Leung YK, Tang WY, Harwood C, Ho SM. Apigenin suppresses cancer cell growth through ERβ. Neoplasia. 2006;8:896–904. doi: 10.1593/neo.06538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Engelmann C, Blot E, Panis Y, Bauer S, Trochon V, Nagy HJ, Lu H, Soria C. Apigenin – strong cytostatic and anti-angiogenic action in vitro contrasted by lack of efficacy in vivo. Phytomedicine. 2002;9:489–495. doi: 10.1078/09447110260573100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Walle T, Ta N, Kawamori T, Wen X, Tsuji PA, Walle UK. Cancer chemopreventive properties of orally bioavailable flavonoids – methylated versus unmethylated flavones. Biochem Pharmacol. 2007;73:1288–1296. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2006.12.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vargo MA, Voss OH, Poustka F, Cardounel AJ, Grotewold E, Doseff AI. Apigenin-induced-apoptosis is mediated by the activation of PKCδ and caspases in leukemia cells. Biochem Pharmacol. 2006;72:681–692. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2006.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jeong YJ, Choi YJ, Choi JS, Kwon HM, Kang SW, Bae JY, Lee SS, Kang JS, Han SJ, Kang YH. Attenuation of monocyte adhesion and oxidised LDL uptake in luteolin-treated human endothelial cells exposed to oxidised LDL. Br J Nutr. 2007;97:447–457. doi: 10.1017/S0007114507657894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nicholas C, Batra S, Vargo MA, Voss OH, Gavrilin MA, Wewers MD, Guttridge DC, Grotewold E, Doseff AI. Apigenin blocks lipopolysaccharide-induced lethality in vivo and proinflammatory cytokines expression by inactivating NF-κB through the suppression of p65 phosphorylation. J Immunol. 2007;179:7121–7127. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.10.7121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ueda H, Yamazaki C, Yamazaki M. A hydroxyl group of flavonoids affects oral anti-inflammatory activity and inhibition of systemic tumor necrosis factor-α production. Biosci, Biotechnol Biochem. 2004;68:119–125. doi: 10.1271/bbb.68.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Németh K, Plumb GW, Berrin JG, Juge N, Jacob R, Naim HY, Williamson G, Swallow DM, Kroon PA. Deglycosylation by small intestinal epithelial cell β-glucosidases is a critical step in the absorption and metabolism of dietary flavonoid glycosides in humans. Eur J Nutr. 2003;42:29–42. doi: 10.1007/s00394-003-0397-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boersma MG, van der Woude H, Bogaards J, Boeren S, Vervoort J, Cnubben NHP, van Iersel MLPS, van Bladeren PJ, Rietjens IMCM. Regioselectivity of phase II metabolism of luteolin and quercetin by UDP-glucuronosyl transferases. Chem Res Toxicol. 2002;15:662–670. doi: 10.1021/tx0101705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen J, Lin H, Hu M. Metabolism of flavonoids via enteric recycling: role of intestinal disposition. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2003;304:1228–1235. doi: 10.1124/jpet.102.046409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tian XJ, Yang XW, Yang X, Wang K. Studies of intestinal permeability of 36 flavonoids using Caco-2 cell monolayer model. Int J Pharm. 2009;367:58–64. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2008.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Andlauer W, Kolb J, Fürst P. Isoflavones from tofu are absorbed and metabolized in the isolated rat small intestine. J Nutr. 2000;130:3021–3027. doi: 10.1093/jn/130.12.3021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lin LZ, Lu S, Harnly JM. Detection and quantification of glycosylated flavonoid malonates in celery, Chinese celery, and celery seed by LC-DAD-ESI/MS. J Agric Food Chem. 2007;55:1321–1326. doi: 10.1021/jf0624796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Matern U. Acylhydrolases from parsley (Petroselinum hortense). Relative distribution and properties of four esterases hydrolyzing malonic acid hemiesters of flavonoid glucosides. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1983;224:261–271. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(83)90209-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. [accessed June 17, 2011];BRENDA Home Page. http://www.brenda-enzymes.org.

- 22.Lechtenberg M, Zumdick S, Gerhards C, Schmidt TJ, Hensel A. Evaluation of analytical markers characterising different drying methods of parsley leaves (Petroselinum crispum L) Pharmazie. 2007;62:949–954. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.DuPont MS, Mondin Z, Williamson G, Price KR. Effect of variety, processing, and storage on the flavonoid glycoside content and composition of lettuce and endive. J Agric Food Chem. 2000;48:3957–3964. doi: 10.1021/jf0002387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Murphy PA, Barua K, Hauck CC. Solvent extraction selection in the determination of isoflavones in soy foods. J Chromatogr, B: Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2002;777:129–138. doi: 10.1016/s1570-0232(02)00342-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schutz K, Kammerer D, Carle R, Schieber A. Identification and quantification of caffeoylquinic acids and flavonoids from artichoke (Cynara scolymus L.) heads, juice, and pomace by HPLC-DAD-ESI/MSn. J Agric Food Chem. 2004;52:4090–4096. doi: 10.1021/jf049625x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Van Der Sluis AA, Dekker M, Skrede G, Jongen WMF. Activity and concentration of polyphenolic antioxidants in apple juice. 1. Effect of existing production methods. J Agric Food Chem. 2002;50:7211–7219. doi: 10.1021/jf020115h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sánchez-Moreno C, Plaza L, Elez-Martínez P, De Ancos B, Martín-Belloso O, Cano MP. Impact of high pressure and pulsed electric fields on bioactive compounds and antioxidant activity of orange juice in comparison with traditional thermal processing. J Agric Food Chem. 2005;53:4403–4409. doi: 10.1021/jf048839b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gil-Izquierdo A, Gil MI, Ferreres F. Effect of processing techniques at industrial scale on orange juice antioxidant and beneficial health compounds. J Agric Food Chem. 2002;50:5107–5114. doi: 10.1021/jf020162+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dewanto V, Wu X, Adom KK, Liu RH. Thermal processing enhances the nutritional value of tomatoes by increasing total antioxidant activity. J Agric Food Chem. 2002;50:3010–3014. doi: 10.1021/jf0115589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Talcott ST, Brenes CH, Pires DM, Del Pozo-Insfran D. Phytochemical stability and color retention of copigmented and processed muscadine grape juice. J Agric Food Chem. 2003;51:957–963. doi: 10.1021/jf0209746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang HJ, Murphy PA. Mass balance study of isoflavones during soybean processing. J Agric Food Chem. 1996;44:2377–2383. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mahungu SM, Diaz-Mercado S, Li J, Schwenk M, Singletary K, Faller J. Stability of isoflavones during extrusion processing of corn/soy mixture. J Agric Food Chem. 1999;47:279–284. doi: 10.1021/jf980441q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Buchner N, Krumbein A, Rohn S, Kroh LW. Effect of thermal processing on the flavonols rutin and quercetin. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 2006;20:3229–3235. doi: 10.1002/rcm.2720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ungar Y, Osundahunsi OF, Shimoni E. Thermal stability of genistein and daidzein and its effect on their antioxidant activity. J Agric Food Chem. 2003;51:4394–4399. doi: 10.1021/jf034021z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nielsen ILF, Chee WSS, Poulsen L, Offord-Cavin E, Rasmussen SE, Frederiksen H, Enslen M, Barron D, Horcajada MN, Williamson G. Bioavailability is improved by enzymatic modification of the citrus flavonoid hesperidin in humans: a randomized, double-blind, crossover trial. J Nutr. 2006;136:404–408. doi: 10.1093/jn/136.2.404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Meyer H, Bolarinwa A, Wolfram G, Linseisen J. Bioavailability of apigenin from apiin-rich parsley in humans. Ann Nutr Metab. 2006;50:167–172. doi: 10.1159/000090736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cao J, Zhang Y, Chen W, Zhao X. The relationship between fasting plasma concentrations of selected flavonoids and their ordinary dietary intake. Br J Nutr. 2010;103:249–255. doi: 10.1017/S000711450999170X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wittemer SM, Ploch M, Windeck T, Müller SC, Drewelow B, Derendorf H, Veit M. Bioavailability and pharmacokinetics of caffeoylquinic acids and flavonoids after oral administration of artichoke leaf extracts in humans. Phytomedicine. 2005;12:28–38. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2003.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]