Abstract

Melanization due to the inactivation of the homogentisate-1,2-dioxygenase gene (hmgA) has been demonstrated to increase stress resistance, persistence, and virulence in some bacterial species but such pigmented mutants have not been observed in pathogenic members of the Vibrio Harveyi clade. In this study, we used Vibrio campbellii ATCC BAA-1116 as model organism to understand how melanization affected cellular phenotype, metabolism, and virulence. An in-frame deletion of the hmgA gene resulted in the overproduction of a pigment in cell culture supernatants and cellular membranes that was identified as pyomelanin. Unlike previous demonstrations in Vibrio cholerae, Burkholderia cepacia, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa, the pigmented V. campbellii mutant did not show increased UV resistance and was found to be ~2.7 times less virulent than the wild type strain in Penaeus monodon shrimp virulence assays. However, the extracted pyomelanin pigment did confer a higher resistance to oxidative stress when incubated with wild type cells. Microarray-based transcriptomic analyses revealed that the hmgA gene deletion and subsequent pyomelanin production negatively effected the expression of 129 genes primarily involved in energy production, amino acid, and lipid metabolism, and protein translation and turnover. This transcriptional response was mediated in part by an impairment of the quorum sensing regulon as transcripts of the quorum sensing high cell density master regulator LuxR and other operonic members of this regulon were significantly less abundant in the hmgA mutant. Taken together, the results suggest that the pyomelanization of V. campbellii sufficiently impairs the metabolic activities of this organism and renders it less fit and virulent than its isogenic wild type strain.

Keywords: Vibrio, melanin, bioluminescence, quorum sensing, tyrosine catabolism

Introduction

As a member of the L-tyrosine catabolism pathway in bacterial and eukaryotic organisms, the enzyme homogentisate 1,2-dioxygenase (HmgA) catalyzes the intermediate homogentisic acid into 4-maleylacetoacetate which is further catabolized to yield fumarate and acetoacetate. In some bacterial species, it has been demonstrated that the inactivation of the hmgA gene results in the accumulation of homogentisic acid which when auto-oxidized leads to the formation of the water-soluble brown pigment pyomelanin (Rodriguez-Rojas et al., 2009; Schmaler-Ripcke et al., 2009; Turick et al., 2009; Valeru et al., 2009; Wang et al., 2011). This phenotype has been observed in naturally pigmented environmental and clinical strains of Vibrio cholerae and has been shown to be due to mutations in the hmgA gene (Wang et al., 2011). Interestingly, pyomelanin pigmented V. cholerae demonstrate greater UV and oxidative stress resistance, virulence factor expression and infant mouse intestine colonization rates than their non-pigmented counterparts (Valeru et al., 2009). The ability of pyomelanin to confer increased resistance to oxidative stress appears to contribute to virulence by reducing the susceptibility of pigmented bacteria to host defense mechanisms. Because of these particular characteristics, it is not surprising that pyomelanin-producing Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Burkholderia cepacia are frequently isolated from cystic fibrosis patients (Zughaier et al., 1999; Rodriguez-Rojas et al., 2009). Furthermore, the production of pyomelanin has also been shown to provide greater protection from other environmental stresses such as hyperosmotic shock and elevated temperatures (Kotob et al., 1995) and act as a sole terminal electron acceptor and soluble electron shuttle to iron which may provide an additional fitness advantage to pyomelanin-producing mutants in anaerobic environments (Turick et al., 2002).

Despite these seemingly advantageous phenotypes, such pigmented mutants have not been reported from pathogenic members of the Vibrio Harveyi clade. Two of the most economically important Harveyi clade species, V. campbellii and V. harveyi, are common inhabitants of tropical marine environments and are among the most important bacterial pathogens of many commercially farmed marine invertebrate and vertebrate species (Thompson et al., 2004; Austin and Zhang, 2006). As certain pathogenic members of both species are capable of producing quorum sensing induced bioluminescence, the disease caused by them is often referred to as luminescent vibriosis (Defoirdt et al., 2008) and is a disease manifestation that is frequently implicated in outbreaks within penaeid shrimp larval culture facilities worldwide (Austin and Zhang, 2006). Given the importance of shrimp hemocyte-mediated oxidative defense mechanisms in combatting Vibrio infections (Ji et al., 2011), it is not unreasonable to posit that pyomelanization may benefit the survival and perhaps exacerbate the virulence of vibrios in this host environment. However, the production of pyomelanin comes at the cost of impairing the tyrosine catabolism pathway and the effect of the inactivation of hmgA and/or pyomelanin production on global cellular metabolism is not known. In this study, we used V. campbellii ATCC BAA-1116, a bioluminescent marine bacterium that is best known as a model organism for quorum sensing studies (Bassler, 1999), to begin to determine the generality of pyomelanin-mediated phenotypes and how the deletion of the hmgA gene and resulting pyomelanin production may affect cellular phenotypes, virulence, and transcription.

Materials and methods

Bacterial strains and growth conditions

V. campbellii (ATCC strain BAA-1116; previously known as V. harveyi BAA-1116 or BB120; Lin et al., 2010) and the hmgA mutant were grown in Luria Marine (LM) medium (20 g NaCl, 10 tryptone, 5 g yeast extract per L, pH 7.8) or Tryptic Soy Broth containing 1% NaCl. Escherichia coli DH5α and SM10λ pir used for standard DNA manipulation and conjugation were grown in Luria Broth (LB) medium.

Construction of the hmgA in-frame deletion mutant

The in-frame deletion of the V. campbellii hmgA gene (ΔhmgA) was generated by overlap PCR (Warrens et al., 1997). Briefly, ~500 bp DNA fragments upstream and downstream of the hmgA open reading frame were amplified from V. campbellii BAA-1116 genomic DNA using the primer pairs hmgA-a (5′-TAggatccTGTACGAAATCGACCATCTGAC)/hmgA-b (5′-c) and hmgA-c (5′-GAGGAGTACTAAGCGGGGGCAAGGATGAAA)/hmgA-d (5′-CActcgagACTTCACCTTCGAAGTCAATCC), respectively. The two PCR products were annealed using their overlapping region and amplified using primers hmgA-a and hmgA-d. The resulting 1 Kb PCR fragment was cloned into the pCR4-TOPO vector using the TOPO TA cloning kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). This assembled fragment was then digested from the TOPO vector with BamHI and XhoI and cloned into the plasmid pZW125, which was constructed by inserting a chloramphenicol resistance gene into the oriRR6Kg plasmid pWM91 containing the sacB gene (Metcalf et al., 1996). The resulting plasmid (pZW025) was transformed into E. coli strain Sm10λ pir and transferred into a V. campbellii spontaneous streptomycin resistant mutant (V. campbellii-str1) by conjugation. The conjugants were grown on LM agar plates containing 3 μg/mL chloramphenicol and 1 μg/mL streptomycin. The ΔhmgA was selected on LM plates supplemented with 6% sucrose and verified by PCR.

Growth curve analyses

Bacterial replication was measured using a Bioscreen C analyzer (Growth Curves USA, Piscataway, NJ, USA). Briefly, overnight cultures were diluted 1:5000 (~105 cells/mL) in pre-warmed LM and five 200 μL aliquots of the wild type (WT) and ΔhmgA strains were transferred into a 100-well honeycomb plate. The plate was incubated at 30°C for 48 h with continuous shaking and wide band OD450−580 nm measurements taken every 30 min. Three independent experiments were performed in this manner.

Measurement of pigmentation, bioluminescence and cellular susceptibility to H2O2

Matched diluted overnight WT and ΔhmgA cultures were used to inoculate 50 mL LM media in 250 mL flasks and incubated at 30°C and 200 rpm. Every 24 h, three 100 μL aliquots of culture were collected and bacterial cells were pelleted via centrifugation at 10,000× g for 5 min. Supernatant pigments were measured using a NanoDrop ND-2000c spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, Pittsburg, PA, USA) at OD400. Another three 100 μL aliquots of culture were placed in a black U96 Nunc MicroWell™ plate (Thermo Scientific) and measured for bioluminescence using a Luminoskan Ascent Microplate Luminometer (Thermo Scientific). Three independent experiments were performed in this manner.

At the 48 h time point, WT, and ΔhmgA cells were harvested, washed and resuspended in fresh LM media. They were then incubated with 2 mM H2O2 at room temperature for 15 min. The percentage survival was calculated by counting colony forming units (CFU) immediately before and after the H2O2 treatment on LM agar plates. The potentially protective effect of WT and ΔhmgA culture supernatants against H2O2 treatment was also tested using WT cells. Briefly, mid-log phase WT cells were harvested, washed and resuspended in 0.2 μm filter-sterilized supernatants from WT and ΔhmgA 48 h LM media cultures. The cell suspensions were then incubated at room temperature in the presence of 2 mM H2O2 for 15 min. The percentage survival was calculated by counting CFUs immediately before and after the H2O2 treatment on LM agar plates. The data for each of these experiments was generated from three independent assays.

Pigment preparation and electron spin resonance spectroscopy

Partial purification of the pigment from the ΔhmgA strain was modified from the method previously described by Turick et al. (2002). Briefly, a 50 mL ΔhmgA culture was grown in LM at 30°C for 96 h with shaking at 200 rpm. The cells were harvested via centrifugation at 5000× g for 10 min, and the supernatant was removed and acidified with 6 N HCl to a final solution concentration of 0.4 N and was then allowed to precipitate for 12 h at room temperature. The concentrated pigment was collected by centrifugation at 8000× g for 20 min, washed twice with dH2O and then dried using a SpeedVac Concentrator (Thermo Scientific). A pure synthetic melanin that was chemically prepared from the oxidation of tyrosine was purchased and used as a control (M8631, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). A second control, DHN-melanin, was prepared from the conidia of the fungus Aspergillus niger using the method of Youngchim et al. (2004). The pigment powder samples were characterized by electron spin resonance (ESR) at 300K in a Bruker 9.5 GHz spectrometer. Typical microwave powers of 5–20 mW with 1G modulation amplitude and 100 kHz field modulation were employed for these experiments.

Shrimp virulence assays

The LD50 of the WT and ΔhmgA strains were evaluated on the black tiger shrimp Penaeus monodon. Both strains were grown in Tryptic Soy Broth containing 1% NaCl at 30°C with shaking at 150 rpm, harvested by centrifugation at 2000× g for 10 min and washed twice with sterile Marinum® artificial seawater (ASW) (Mariscience International Co. Ltd., Bangkok, Thailand). Bacterial cell suspensions in ASW were adjusted to 2.6 × 108 CFU/mL using a turbidimeter (Oxoid Ltd., United Kingdom) and twofold dilutions were performed to obtain the required concentrations of bacteria prior to injecting the shrimp. The juvenile shrimp used in this study were 10–13 g in weight and 4–5 inches in length. Each shrimp received an intramuscular injection of 100 μL diluted V. campbellii (with batches of seven shrimp/dose) between the third and fourth abdominal segments. Control shrimp were injected with ASW. The experiments were performed in quadruplicate. The animals were maintained in a 70 L ASW glass tank at a temperature of 29 ± 1°C and salinity of 17 ppt. Shrimp mortalities were observed within 48 h of injection and were confirmed by detecting bioluminescence in the organs of the dead shrimp. The LD50 was calculated using the method of Reed and Muench (1938).

Microarray-based transcriptome analyses

Aliquots of three cultures (3.0 × 108 cells/mL) of the WT and ΔhmgA strains grown in LM at 30°C for 48 h with constant shaking at 200 rpm were harvested for total RNA extraction. RNA was isolated using the RiboPure™-Bacteria Kit (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY, USA), treated with DNase and 10 μg of total RNA from each culture was further purified using the MICROBExpress™ Bacterial mRNA Enrichment Kit (Life Technologies) according to the manufacturer's specifications. All RNA preparations were quantified and analyzed using the Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Inc., Santa Clara, CA, USA) and normalized to 1 μg. The normalized RNA was labeled, purified, fragmented and hybridized to a custom Affymetrix microarray (520694F) according to standard protocols (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA, USA). All hybridizations incubated for 16 h at 49°C in the GeneChip® Hybridization Oven 640 at 60 rpm and the microarrays were then washed and stained with the GeneChip® Fluidics Station 450 and scanned using the GeneChip® Scanner 7G (Affymetrix). Hybridization signal intensities were analyzed with the GeneChip® Operating Software (GCOS) to generate raw image files (.DAT) and simplified image files (.CEL) with intensities assigned to each of the corresponding probe positions. The data collected was used to profile the expression levels of 4831 open reading frames. The data containing the distribution of the probe amplitudes were calculated and a classical analysis of variance (ANOVA; applying the CRAN R's aov function) was performed across conditions for each probe site. The median values revealing the gene-level measurement of differential expression was determined (Rubin, 2009). The gene designations and annotations utilized are from the Naval Research Laboratory's V. campbellii ATCC BAA-1116 genome sequencing effort (GenBank accession numbers CP006605, CP006606, CP006607) and the expression profiling data can be found in the GenBank Gene Expression Omnibus repository (accession number GSE46223).

Quantitative reverse transcription PCR

Real-time reverse transcription PCR assays were conducted using the iScript™ One-Step RT-PCR Kit with SYBR Green (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA). One nanogram of mRNA from two biological replicates were tested in triplicate on an iCycler (BioRad). The PCR primers were designed using Primer3 online software (v. 0.4.0) (http://frodo.wi.mit.edu/). Relative quantities of the transcripts were determined using the 2−ΔΔCt formula where ΔCt is the difference in Ct of the selected genes and Ct of the normalizer gene, and ΔΔCt is the difference in ΔCt from ΔhmgA and ΔCt from the WT. The rpoS1 gene was used to normalize the expression levels of the selected genes as its transcription level was found to be constant in both the WT and ΔhmgA strains.

Results and discussion

Characterization of ΔhmgA pigment and phenotypes

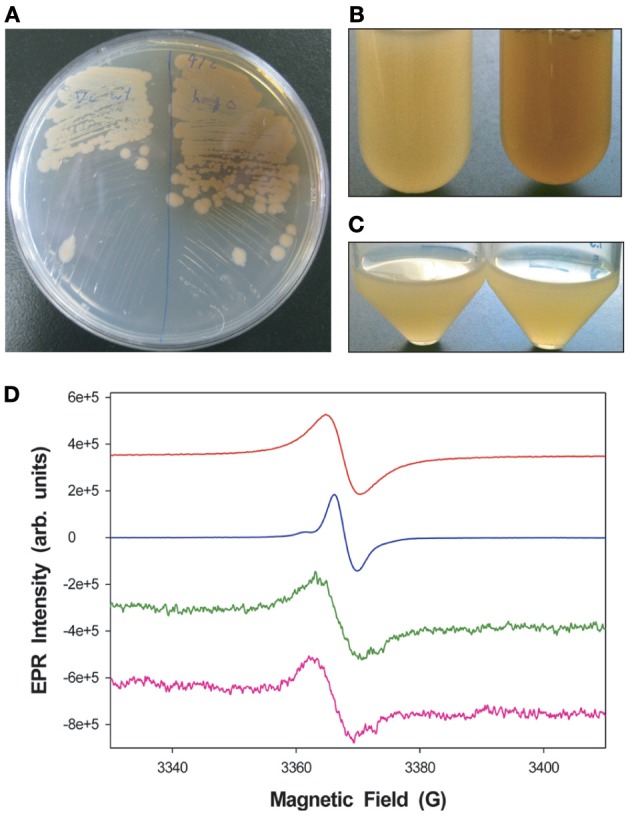

An examination of the V. campbellii ATCC BAA-1116 genome revealed that 4 genes in the catabolic pathway of tyrosine metabolism, hmgA (M892_02450), hppd (4-hydroxyphenylpyruvate dioxygenase, M892_02455), fahA (fumarylacetoacetase, M892_02445), and maiA (maleylacetoacetate isomerase, M892_02440), appeared to form an operon and shared the same genetic synteny as other sequenced Vibrio species. An in-frame deletion of the hmgA gene was generated (ΔhmgA) to investigate the role of this gene in pigment production and cellular physiology. When cultured on LM agar plates, in baffled glass Erlenmeyer flasks or polystyrene round-bottomed tubes for ≥ 48 h, the ΔhmgA strain produced a brown pigment that was expected to be the result of the auto-oxidation and polymerization of homogentisate (Figures 1A,B). The pigment was found to be present in ΔhmgA cell-free supernatants as well as washed cell pellets suggesting that the pigment was not only released into the microenvironment but could also be found associated with the bacterial cell membrane (data not shown). Interestingly, the production of this pigmentation was not observed when ΔhmgA cells were cultured in 50 mL polypropylene conical tubes (Figure 1C). Under the experimental conditions utilized, the 50 mL conical tubes provided the least aeration. In the absence of sufficient aeration, which is required for the oxidation of homogentisate, the production of the pigment was not observed. In order to identify the oxidized homogentisate polymer, the extracted brown pigment from ΔhmgA cell culture supernatants was examined using ESR. The ESR spectrum of the pigment revealed a distinct stable free radical signal that was characteristic of melanin and highly similar to synthetic eumelanin and DHN melanin of Aspergillus niger (Figure 1D) thus, confirming that the ΔhmgA pigment was pyomelanin. The results demonstrate that like V. cholerae ΔhmgA, V. campbellii ΔhmgA also produces pyomelanin but does not appear to do so in the same abundance or nearly as rapidly (Valeru et al., 2009).

Figure 1.

Pigmentation differences between V. campbellii WT and ΔhmgA. (A) Colonies grown on LM agar. WT (left), ΔhmgA (right); (B) Cell cultures grown in LM in borosilicate glass tubes (48 h). WT (left), ΔhmgA (right); (C) Cell cultures grown in LM in polypropylene conical tubes (48 h). WT (left), ΔhmgA (right); (D) EPR spectra of synthetic melanin (red), DHN-melanin (blue) and partially purified pigments from the supernatants of two independent ΔhmgA cultures (green and pink).

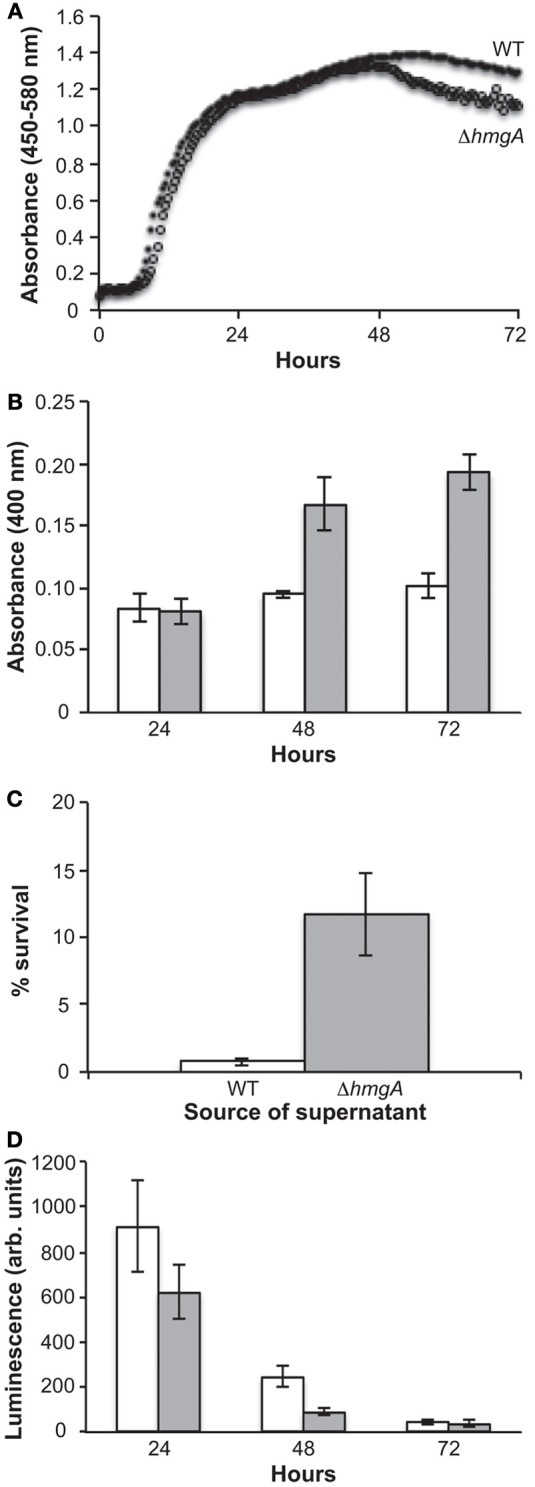

Growth curve analyses in nutrient rich LM medium revealed that the WT and ΔhmgA strains grew equally well during the lag, log, and early stationary phases of growth. However, ΔhmgA displayed a lesser ability to survive during late stationary phase (post 48 h) (Figure 2A): a time point that coincided with the measurable production of pyomelanin (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Growth, pigment production and bioluminescence in V. campbellii WT and ΔhmgA. (A) Grow curves of the WT and ΔhmgA strains in LM at 30°C. WT (closed circle), ΔhmgA (open circle); (B) Absorbance of pigment-containing supernatants. WT (white bars), ΔhmgA (gray bars); (C) Survival of WT V. campbellii cells in 2 mM H2O2 when resuspended in supernatants from WT or ΔhmgA cultures; (D) Bioluminescence measurements. WT (white bars), ΔhmgA (gray bars). Error bars represent the standard deviation from three experiments.

In other bacterial and fungal organisms, melanin has been demonstrated to have a role in protecting against certain environmental stressors as mutations in the hmgA gene and the resulting melanization have been shown to provide an increased resistance to UV irradiation and H2O2-mediated oxidative stress (Rodriguez-Rojas et al., 2009; Schmaler-Ripcke et al., 2009; Valeru et al., 2009). However, when we performed similar experiments comparing the response of V. campbellii WT and ΔhmgA washed cells to different doses of UV irradiation and concentrations of H2O2, no significant differences in viability were observed (data not shown). Interestingly, however, we did observe the protective properties of pyomelanin when cell-free pyomelanin-containing supernatants from ΔhmgA cultures were incubated with WT cells and then exposed to 2 mM H2O2 (Figure 2C). Comparatively, cell-free supernatants from WT cultures did not demonstrate this protective function. The combined H2O2 challenge results demonstrated the protective material property of V. campbellii pyomelanin and suggest that there is not sufficient membrane-associated pyomelanin in V. campbellii to afford this same level of protection in the absence of the accumulated extracellular pyomelanin.

Unlike any other pyomelanin-producing bacterium investigated to date, V. campbellii ATCC BAA-1116 is capable of generating quorum sensing-induced bioluminescence. Interestingly, previous studies have suggested that the luciferase enzyme and bacterial bioluminescence, like pyomelanin, also play a physiological role in protecting cells against UV and oxidative stress. For example, UV irradiation has been found to stimulate bioluminescence (Czyz et al., 2002) which in turn photoreactivates DNA repair processes (Kozakiewicz et al., 2005) and bioluminescent cells have been shown to be significantly more resistant to UV irradiation than their non-bioluminescent counterparts (Czyz et al., 2000; Kozakiewicz et al., 2005). In addition, various oxidants, such as H2O2, have been shown to severely impair the growth of vibrios lacking the luciferase enzyme (Szpilewska et al., 2003). This is due to the fact that in addition to the production of light, this enzyme is also capable of increasing cellular resistance to oxidative stress by detoxifying reactive oxygen species (Katsev et al., 2004). Therefore, in addition to the more common bacterial mechanisms of UV and oxidative stress protection, bioluminescent V. campbellii also contain luciferase-based protective mechanisms. This combination of luciferase and pyomelanin in the same organism introduced the possibility of additive or synergistic stress protection. However, when the bioluminescence output of ΔhmgA was examined during measurable pyomelanin production (48 h), it was found to be significantly attenuated in comparison to the WT (Figure 2D). While this result demonstrated a diminution of light production in pyomelanin-producing ΔhmgA, it was incapable of determining whether this was due to a decrease in luciferase abundance or activity, reduced intracellular O2 or necessary substrates.

Shrimp virulence model

In V. cholerae ΔhmgA and P. aeruginosa ΔhmgA, pyomelanization was shown to play a role in increasing virulence factor expression and adaptation to chronic infections in vertebrate animal models (Rodriguez-Rojas et al., 2009; Valeru et al., 2009). As V. campbellii BAA-1116 is known to pathogenize shrimp, we sought to determine whether V. campbellii pyomelanization would have a similar effect on invertebrate animal infections. V. campbellii WT and ΔhmgA were used to infect juvenile black tiger shrimp (Penaeus monodon) and the LD50 of both were evaluated. Surprisingly, the LD50 of ΔhmgA was ~2.7 times higher (less lethal) than that of the WT indicating that the production of pyomelanin in ΔhmgA was associated with decreased virulence in this model infection system (Table 1).

Table 1.

V. campbellii BAA-1116 and ΔhmgA Penaeus monodon challenge.

| Experiment no. | LD50 (CFU/mL) | |

|---|---|---|

| WT | ΔhmgA | |

| 1 | 1.4 × 108 | > 3.1 × 108 |

| 2 | 2.1 × 108 | 4.1 × 108 |

| 3 | 2.4 × 108 | 5.8 × 108 |

| 4 | 1.9 × 108 | 5.4 × 108 |

| Mean ± SD | 1.9 ± 0.4 × 108 | 5.1 ± 0.9 × 108 |

Four independent LD50 experiments were performed. Mean values of LD50 between the WT and ΔhmgA were significantly different (P < 0.05, student's t-test).

In invertebrates, one of two major immune responses against invading pathogens is the prophenoloxidase activating system (proPO) (Cerenius and Soderhall, 2004). Upon infection, non-self molecules such as lipopolysaccharide, peptidoglycan and β-glucan can activate the proPO I cascade and result in the formation of melanin around the invading microorganisms. In this circumstance, the host formed melanin is thought to physically shield the pathogens to prevent or retard their growth. Host derived quinones, which are intermediates of melanin production, may also be involved in the production of cytotoxic molecules (e.g., superoxides, hydroxyl radicals) that could help inactivate the invading pathogens. The protective efficacy of the proPO system is further highlighted by the demonstration that gene silencing of PO activating enzymes in Penaeus monodon increases the susceptibility of the host to V. harveyi infection (Amparyup et al., 2009; Charoensapsri et al., 2009). Given these facts and the demonstrated phenotypes of V. campbellii ΔhmgA, we suggest that pyomelanization may reduce this bacterium's virulence potential in two ways. First, pyomelanin production by ΔhmgA cells may effectively add another layer to the host-assembled melanin around the sites of infection so as to further limit bacterial growth. The comparatively poor survival of ΔhmgA in late stationary phase (the time of melanization) (Figure 2A) may allude to this possibility. Second, the pyomelanin produced by ΔhmgA may be recognized by the host as another foreign moiety that could further stimulate the proPO system and enhance the clearance of these bacteria.

Transcriptome analyses

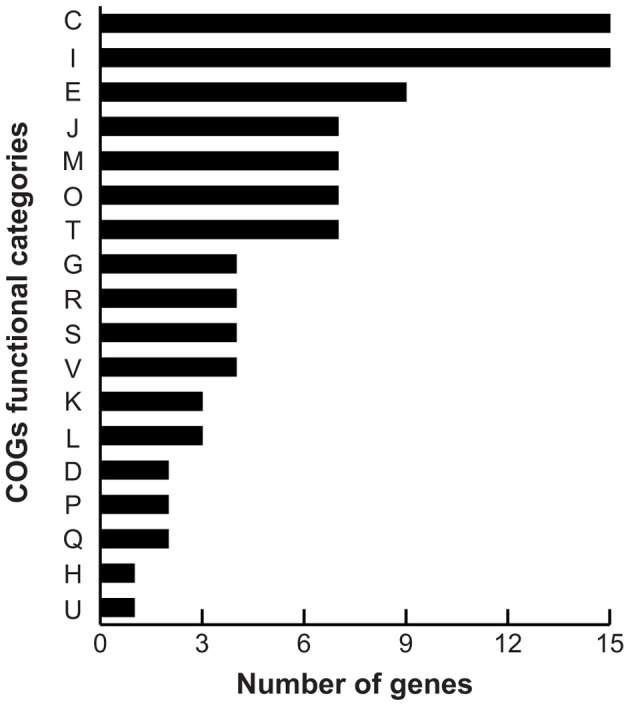

As the differences in pyomelanin production, bioluminescence and survival were observed during late stationary phase (48 h), we chose this time point to perform comparative microarray-based expression profiling analyses to understand how the deletion of the hmgA gene and subsequent production of pyomelanin gave rise to the observed phenotypes. Whole genome expression profiling revealed that 129 genes (2.7% of the interrogated genome) were significantly modulated in ΔhmgA when compared to the WT (adjusted p-value < 0.001). Overall, inactivation of the hmgA gene appeared to affect the expression of genes involved in energy production and conversion, amino acid metabolism, lipid metabolism, and quorum sensing/bioluminescence (Figure 3). Interestingly, the transcript levels of all 129 genes were found to be less abundant in ΔhmgA with approximately 70% of them demonstrating a ≥ twofold reduction in transcript abundance (Table 2). The transcriptional modulation of 10 of these genes was also verified using quantitative RT-PCR (Table 2).

Figure 3.

COG summary of differentially expressed genes. COG functional category: C, energy production and conversion; I, lipid transport and metabolism; E, amino acid transport and metabolism; J, translation, ribosomal structure and biogenesis; M, cell wall/membrane/envelope biogenesis; O, post-translational modification, protein turnover, chaperones; T, signal transduction mechanisms; G, carbohydrate transport and metabolism; R, general function prediction only; S, function unknown; V, defense mechanisms; K, transcription; L, replication, recombination and repair; D, cell cycle control, cell division, chromosome partitioning; P, inorganic ion transport and metabolism; Q, secondary metabolites biosynthesis, transport and catabolism; H, coenzyme transport and metabolism; U, intracellular trafficking, secretion, and vesicular transport.

Table 2.

Differentially expressed genes in ΔhmgA compared with WT V. campbellii.

| Gene ID | Annotation | pval | WTa | ΔhmgA | Changeb | qRT-PCRc | Functione |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M892_05385 | Pyruvate-formate lyase | 3.12E-06 | 2.45 | 1.11 | 2.21 | C | |

| M892_06250 | 2-oxoglutarate dehydrogenase | 5.20E-04 | 1.29 | 0.67 | 1.93 | C | |

| M892_06265 | Succinate dehydrogenase | 1.59E-04 | 0.82 | 0.37 | 2.22 | C | |

| M892_06275 | Citrate synthase | 1.57E-06 | 2.31 | 0.72 | 3.21 | C | |

| M892_08460 | Ubiquinol-cytochrome c reductase | 1.12E-05 | 1.45 | 0.61 | 2.38 | C | |

| M892_08470 | Ubiquinol-cytochrome c reductase, iron-sulfur subunit | 4.80E-06 | 1.36 | 0.86 | 1.58 | 2.50 | C |

| M892_10625 | ATP synthase subunit alpha | 1.24E-04 | 2.17 | 1.55 | 1.40 | C | |

| M892_13885 | Aconitate hydratase | 2.42E-06 | 2.21 | 1.12 | 1.97 | C | |

| M892_17240 | Cytochrome c-type protein NrfB | 1.17E-06 | 1.24 | 0.04 | 31.00 | C | |

| M892_17245 | Nitrite reductase, Fe-S protein NrfC | 1.73E-06 | 1.24 | 0.02 | 62.00 | 1.58 | C |

| M892_23815 | acyl-CoA dehydrogenase, short-chain specific EtfA | 6.43E-06 | 1.72 | 0.52 | 3.31 | 5.30 | C |

| M892_23820 | Electron transfer flavoprotein subunit beta EtfB | 5.49E-05 | 1.69 | 0.73 | 2.32 | C | |

| M892_23825 | Electron transfer flavoprotein-ubiquinone oxidoreductase EtfD | 5.04E-04 | 0.85 | 0.24 | 3.54 | C | |

| M892_24165 | Trimethylamine-N-oxide reductase 1 | 3.42E-06 | 2.20 | 1.19 | 1.85 | C | |

| M892_08360 | Cell division GTPase | 2.15E-05 | 1.42 | 0.9 | 1.58 | D | |

| M892_08365 | Cell division protein FtsA | 3.06E-04 | 1.13 | 0.79 | 1.43 | D | |

| M892_03740 | Aspartate aminotransferase | 2.04E-04 | 0.90 | 0.32 | 2.81 | E | |

| M892_03990 | Phosphoribosyl-AMP cyclohydrolase | 2.70E-05 | 1.57 | 0.87 | 1.80 | E | |

| M892_03995 | Imidazoleglycerol-phosphate synthase | 4.98E-04 | 1.51 | 1.04 | 1.45 | E | |

| M892_12425 | Argininosuccinate lyase | 1.13E-06 | 1.94 | 1.00 | 1.94 | E | |

| M892_13555 | Aspartokinase | 2.04E-04 | 0.92 | 0.07 | 13.14 | E | |

| M892_16070 | Lactoylglutathione lyase | 5.98E-08 | 3.09 | 2.02 | 1.53 | E | |

| M892_27505 | Sodium/proline symporter PutP | 1.13E-06 | 2.02 | 0.78 | 2.59 | E | |

| M892_27510 | Delta 1-pyrroline-5-carboxylate dehydrogenase PutC | 5.98E-08 | 3.20 | 1.87 | 1.71 | 4.18 | E |

| M892_27515 | Proline dehydrogenase PutB | 2.10E-07 | 3.04 | 1.27 | 2.39 | E | |

| M892_10225 | 2-keto-3-deoxy-6-phosphogluconate aldolase | 9.40E-04 | 1.12 | 0.42 | 2.67 | G | |

| M892_13305 | Fructose-bisphosphate aldolase | 8.05E-04 | 2.17 | 1.05 | 2.07 | 1.23 | G |

| M892_19270 | Enolase | 8.81E-04 | 0.73 | 0.06 | 12.17 | G | |

| M892_20700 | Phosphomannomutase | 2.06E-04 | 1.86 | 0.69 | 2.70 | G | |

| M892_09970 | Delta-aminolevulinic acid dehydratase | 1.28E-04 | 0.60 | 0.00 | UDd | H | |

| M892_15785 | Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase | 5.76E-05 | 2.46 | 1.37 | 1.80 | 6.60 | I |

| M892_24035 | 3-hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase IvdG | 1.22E-04 | 0.78 | 0.25 | 3.12 | I | |

| M892_24040 | 3-hydroxyisobutyrate dehydrogenase IvdF | 5.61E-06 | 1.73 | 0.70 | 2.47 | I | |

| M892_24045 | Enoyl-CoA hydratase/isomerase IvdE | 9.29E-06 | 2.06 | 0.66 | 3.12 | I | |

| M892_24050 | 3-hydroxyisobutyryl-CoA hydrolase IvdD | 2.15E-05 | 1.73 | 0.36 | 4.81 | I | |

| M892_24055 | Branched-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase IvdC | 1.59E-04 | 1.12 | 0.46 | 2.43 | I | |

| M892_24060 | Methylmalonate-semialdehyde dehydrogenase IvdB | 1.49E-06 | 2.18 | 0.55 | 3.96 | 2.49 | I |

| M892_24065 | 3-ketoacyl-CoA thiolase IvdA | 1.98E-05 | 1.94 | 0.79 | 2.46 | I | |

| M892_24075 | Isovaleryl-CoA dehydrogenase LiuA | 3.91E-06 | 2.13 | 0.87 | 2.45 | I | |

| M892_24080 | Methylcrotonyl-CoA carboxylase carboxyl transferase LiuB | 5.84E-05 | 1.46 | 0.66 | 2.21 | I | |

| M892_24525 | Polyhydroxyalkanoic acid synthase PhaC | 1.27E-05 | 1.05 | 0.10 | 10.50 | I | |

| M892_24530 | PHA granule-associated protein PhaD | 5.48E-05 | 3.07 | 0.57 | 5.39 | I | |

| M892_24535 | Acetyl-CoA acetyltransferase PhaA | 4.29E-06 | 3.25 | 0.95 | 3.42 | 6.61 | I |

| M892_24540 | Acetoacetyl-CoA reductase PhaB | 9.29E-06 | 2.97 | 0.83 | 3.58 | I | |

| M892_16425 | Acyl carrier protein | 8.93E-06 | 4.07 | 1.59 | 2.56 | I | |

| M892_02880 | Ribosomal protein L35 | 5.66E-04 | 2.01 | 1.40 | 1.44 | J | |

| M892_02885 | Bacterial protein translation initiation factor 3 | 1.83E-05 | 2.95 | 2.39 | 1.23 | J | |

| M892_07900 | Ribosome-associated protein Y | 6.25E-05 | 4.21 | 2.97 | 1.42 | J | |

| M892_12355 | Translation elongation factor | 8.45E-04 | 1.71 | 0.60 | 2.85 | J | |

| M892_12355 | Translation elongation factor | 4.38E-07 | 3.54 | 2.41 | 1.47 | J | |

| M892_12355 | Translation elongation factor | 1.01E-05 | 3.41 | 2.02 | 1.69 | J | |

| M892_14350 | Translation elongation factor | 1.34E-05 | 1.90 | 0.81 | 2.35 | J | |

| M892_08765 | Transcriptional regulator | 5.57E-07 | 3.21 | 1.93 | 1.66 | K | |

| M892_12185 | Ribonuclease R | 1.24E-05 | 1.87 | 0.86 | 2.17 | K | |

| M892_13795 | Quorum sensing regulator LuxR | 2.78E-05 | 1.98 | 0.62 | 3.19 | 3.57 | K |

| M892_02740 | Bacterial nucleoid DNA-binding protein | 1.59E-09 | 2.83 | 1.07 | 2.64 | L | |

| M892_11585 | DNA-binding protein | 2.08E-07 | 1.37 | 0.13 | 10.54 | L | |

| M892_12540 | Replicative DNA helicase | 7.48E-05 | 1.11 | 0.63 | 1.76 | L | |

| M892_06105 | Membrane-bound lytic murein transglycosylase B | 2.70E-05 | 1.36 | 0.85 | 1.60 | M | |

| M892_08355 | UDP-3-O-3-hydroxymyristoyl N-acetylglucosamine deacetylase | 5.65E-04 | 2.28 | 1.56 | 1.46 | M | |

| M892_08935 | UDP-N-acetylmuramate-L-alanyl-gamma-D-glutamyl-m eso-diaminopimelate ligase | 1.23E-04 | 1.05 | 0.48 | 2.19 | M | |

| M892_12935 | UDP-N-acetylglucosamine 1-carboxyvinyltransferase | 4.02E-04 | 1.06 | 0.60 | 1.77 | M | |

| M892_14045 | Outer membrane protein OmpU | 7.81E-05 | 1.24 | 0.41 | 3.02 | M | |

| M892_20750 | Outer membrane protein OmpA | 4.16E-05 | 3.20 | 1.66 | 1.93 | M | |

| M892_25630 | Outer membrane lipoprotein | 1.39E-10 | 4.43 | 1.51 | 2.93 | M | |

| M892_00180 | Heat shock protein HslJ | 5.20E-04 | 1.95 | 0.58 | 3.36 | O | |

| M892_00340 | Glutaredoxin | 4.76E-04 | 1.29 | 0.61 | 2.11 | O | |

| M892_07710 | Antioxidant, AhpC/Tsa family | 2.08E-07 | 2.20 | 0.28 | 7.86 | O | |

| M892_07875 | ClpB protein | 8.45E-04 | 1.25 | 0.37 | 3.38 | O | |

| M892_09255 | Peptidase | 5.78E-04 | 1.79 | 0.39 | 4.59 | O | |

| M892_11900 | Chaperonin GroEL | 1.70E-06 | 1.14 | 0.16 | 7.13 | O | |

| M892_12155 | Serine protease | 1.59E-04 | 1.45 | 0.58 | 2.50 | O | |

| M892_05540 | Cation transport ATPase | 4.53E-06 | 1.34 | 0.63 | 2.13 | P | |

| M892_15095 | Arsenate reductase | 5.66E-04 | 1.36 | 0.79 | 1.72 | P | |

| M892_12915 | Putative ABC superfamily transport protein | 5.26E-05 | 0.41 | 0.02 | 20.50 | Q | |

| M892_12920 | ABC-type transport system, auxiliary component | 1.17E-06 | 1.86 | 0.49 | 3.80 | Q | |

| M892_01320 | Immunogenic protein | 1.77E-05 | 1.63 | 0.41 | 3.98 | R | |

| M892_12140 | RNA-binding protein Hfq | 1.46E-06 | 2.94 | 1.96 | 1.50 | R | |

| M892_18180 | Ecotin precursor | 6.37E-05 | 1.51 | 0.99 | 1.53 | R | |

| M892_26640 | Hemolysin | 6.13E-08 | 1.93 | 0.54 | 3.57 | R | |

| M892_05800 | Lipoprotein-related protein | 6.13E-08 | 1.20 | 0.24 | 5.00 | S | |

| M892_08695 | Hypothetical protein | 3.42E-05 | 1.09 | 0.40 | 2.73 | S | |

| M892_13325 | Hypothetical protein | 4.02E-07 | 3.90 | 1.96 | 1.99 | S | |

| M892_24630 | Hypothetical protein | 7.09E-04 | 0.78 | 0.23 | 3.39 | S | |

| M892_05410 | Putative serine protein kinase | 5.29E-06 | 2.33 | 0.44 | 5.30 | T | |

| M892_10150 | Universal stress protein | 1.95E-04 | 2.37 | 1.25 | 1.90 | T | |

| M892_12235 | Cyclic AMP receptor protein | 1.76E-04 | 1.24 | 0.59 | 2.10 | T | |

| M892_13400 | Negative regulator of sigma E activity | 3.29E-05 | 2.29 | 1.48 | 1.55 | T | |

| M892_13405 | Periplasmic negative regulator of sigma E | 1.17E-05 | 1.51 | 0.88 | 1.72 | T | |

| M892_13560 | Carbon storage regulator | 1.18E-04 | 1.75 | 1.05 | 1.67 | T | |

| M892_20245 | Universal stress protein A | 1.03E-09 | 3.31 | 1.71 | 1.94 | T | |

| M892_05075 | Translocation protein TolB | 3.03E-05 | 1.18 | 0.65 | 1.82 | U | |

| M892_05460 | ABC transporter, ATP-binding protein | 6.12E-04 | 1.16 | 0.53 | 2.19 | V | |

| M892_07350 | Type I site-specific deoxyribonuclease specificity subunit | 7.70E-04 | 1.94 | 1.20 | 1.62 | V | |

| M892_07355 | Type I restriction-modification system, methyltransferase subunit | 1.57E-06 | 2.19 | 1.34 | 1.63 | V | |

| M892_20315 | Beta-lactamase | 1.56E-05 | 1.48 | 0.49 | 3.02 | V | |

| M892_03945 | Hypothetical protein | 5.33E-05 | 0.36 | 0.00 | UD | ||

| M892_05165 | Gonadoliberin III-related protein | 9.73E-05 | 0.78 | 0.1 | 7.80 | ||

| M892_05170 | Hypothetical protein | 2.71E-07 | 1.11 | 0.32 | 3.47 | ||

| M892_05480 | Hypothetical protein | 1.76E-04 | 0.98 | 0.30 | 3.27 | ||

| M892_07360 | Phage transcriptional regulator AlpA | 2.58E-04 | 2.02 | 0.83 | 2.43 | ||

| M892_10485 | NADH dehydrogenase subunit II-related protein | 1.66E-08 | 3.75 | 2.87 | 1.31 | ||

| M892_12930 | BolA/YrbA family protein | 2.75E-04 | 0.85 | 0.07 | 12.14 | ||

| M892_13365 | Hypothetical protein | 1.73E-04 | 3.25 | 1.17 | 2.78 | ||

| M892_15830 | Hypothetical protein | 7.46E-05 | 1.24 | 0.30 | 4.13 | ||

| M892_16465 | Hypothetical protein | 7.48E-05 | 1.52 | 0.27 | 5.63 | ||

| M892_17010 | Hypothetical protein | 2.32E-08 | 2.16 | 0.35 | 6.17 | ||

| M892_18970 | Hypothetical protein | 2.82E-05 | 1.39 | 0.25 | 5.56 | ||

| M892_19525 | Putative lipoprotein | 1.86E-08 | 4.17 | 1.09 | 3.83 | ||

| M892_19565 | Muconate cycloisomerase I | 2.36E-04 | 1.64 | 0.41 | 4.00 | ||

| M892_19745 | Hypothetical protein | 3.75E-04 | 0.39 | 0.00 | UD | ||

| M892_20825 | Fatty acid reductase LuxC | 9.07E-06 | 2.64 | 1.23 | 2.15 | ||

| M892_20830 | Myristoyl-ACP-specific thioesterase LuxD | 1.01E-05 | 2.98 | 1.28 | 2.33 | ||

| M892_20835 | Alkanal monooxygenase alpha chain LuxA | 4.02E-07 | 4.00 | 1.78 | 2.25 | ||

| M892_20840 | Alkanal monooxygenase beta chain LuxB | 3.43E-04 | 4.84 | 2.08 | 2.33 | 4.81 | |

| M892_20845 | Long-chain-fatty-acid luciferin-component ligase LuxE | 5.14E-05 | 2.83 | 0.87 | 3.25 | ||

| M892_20850 | NAD(P)H-dependent FMN reductase LuxG | 4.58E-06 | 1.78 | 0.81 | 2.20 | ||

| M892_22630 | Peptidase | 1.03E-04 | 1.74 | 1.05 | 1.66 | ||

| M892_22965 | Positive response regulator for Pho regulon | 3.60E-06 | 2.16 | 0.82 | 2.63 | ||

| M892_24070 | Transcriptional regulator LiuR | 0.0003 | 0.25 | 0.00 | UD | ||

| M892_24215 | Putative GTPase | 4.14E-05 | 1.14 | 0.50 | 2.28 | ||

| M892_24655 | Hypothetical protein | 3.22E-05 | 4.11 | 1.48 | 2.78 | ||

| M892_25115 | Transcriptional regulator LuxT | 2.58E-04 | 2.96 | 2.25 | 1.32 | ||

| M892_25430 | Azurin | 5.16E-04 | 1.88 | 1.20 | 1.57 | ||

| M892_25755 | ATP-dependent protease | 7.73E-04 | 0.75 | 0.26 | 2.88 | ||

| M892_25795 | Predicted transcriptional regulator protein | 8.83E-07 | 2.37 | 0.26 | 9.12 | ||

| M892_26535 | Putative lipoprotein | 1.86E-08 | 1.76 | 0.19 | 9.26 | ||

| M892_26800 | Hypothetical protein | 7.73E-05 | 1.29 | 0.68 | 1.90 |

Average signal intensity log2 values from three experiments.

Transcript ratio between WT and ΔhmgA.

Transcript ratio between WT and ΔhmgA from qRT-PCR data. qRT-PCR Ct values were derived from the average of duplicates from two independent biological samples.

Undivisible as no transcript was detected from ΔhmgA.

COG functional categories: C, energy production and conversion. D, cell cycle control, cell division and chromosome partitioning; E, amino acid transport ad metabolism; G, carbohydrate transport and metabolism; H, coenzyme transport and metabolism; I, lipid transport and metabolism; J, translation, ribosomal structure and biogenesis; K, transcription; L, replication, recombination and repair; M, cell wall/membrane/envelop biogenesis; O, post-translational modification, protein turnover and chaperones; P, inorganic ion transport and metabolism; Q, secondary metabolites biosynthesis, transport and catabolism; R, general function prediction only; S, function unknown; T, signal transduction mechanisms; U, intracellular trafficking, secretion and vesicular transport; V, defense mechanisms.

Energy production and electron transfer

Two of 3 genes (M892_08460, M892_08470) in an operon encoding subunits of ubiquinol-cytochrome c reductase were down-regulated in ΔhmgA. This cytochrome complex catalyzes the oxidoreduction of mobile redox components generating an electrochemical potential (Kurowski and Ludwig, 1987). Two other modulated genes, NrfB (M892_17240) and NrfC (M892_17245), encode cytochrome-type components of the electron transfer chain of respiratory nitrite ammonification in γ-proteobacteria (Simon, 2002). This electron transfer reaction usually occurs during anaerobic growth and the electron donor formate is readily formed from pyruvate by pyruvate formate lyase. Coincidently, the gene encoding pyruvate formate lyase (M892_05385) was also repressed in the mutant. In addition, a number of genes in the glycolysis pathway, such as those encoding fructose-bisphosphate aldolase (M892_13305), glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (M892_15785) and enolase (M892_19270), were down-regulated as well, and likely result in the reduced production of pyruvate. Since HmgA is not a DNA regulatory factor, these results indicated that the pyomelanin produced in ΔhmgA may decrease redox activity by serving as an electron sink which in turn would interfere with electron transfer and further weaken cellular respiration in late stationary phase.

Amino acid and lipid metabolism

The transcripts from three well characterized gene clusters involved in amino acid and lipid metabolism (etfABD, ivdABCDEFG, liuABCDE) were also significantly down-regulated in ΔhmgA. These operons encode enzymes that take part in the branched-chain amino acid (i.e., isoleucine, leucine, valine) degradation pathway that is used for energy production in many proteobacteria (Kazakov et al., 2009). Proteins encoded by etfABD catalyze electron transfer from quinones to flavoproteins not only in the leucine degradation pathway but also in the fatty acid degradation pathway. The master regulator of the branched-chain amino acid degradation pathway, LiuR, is encoded by the liuR gene which resides between the liuABCDE and ivdABCDEFG operons. The liuR gene was also significantly down-regulated in ΔhmgA (p-value = 0.0003) suggesting a regulatory mechanism for the pyomelanin-induced retardation of branched-chain amino acid degradation.

It was interesting to note that another amino acid degradation pathway was also affected by the production of pyomelanin. The proline utilization operon putBCP, encoding proline dehydrogenase, δ-1-pyroline-5-carboxylate dehydrogenase and permease, respectively, was also down-regulated in ΔhmgA. However, the expression of pruR, which is adjacent to and has been reported to regulate the putBCP operon in P. aeruginosa PAO1 (Nakada et al., 2002), did not change. Interestingly, transcription of the putBCP operon has been reported to respond to osmotic stress by producing more of the final product glutamate in V. vulnificus (Lee et al., 2003) and coincidently, pyomelanin biosynthesis was also demonstrated to be induced by osmotic stress in V. cholerae (Coyne and Al-Harthi, 1992). Thus, it is possible that ΔhmgA pyomelanin may function as a solute glutamate to counter osmotic stress during late stationary phase thus, alleviating the physiological signal for the increased expression of putBCP and resulting in the decreased transcription observed in this study.

Virulence, quorum sensing, and bioluminescence

Although the virulence mechanisms that contribute to bioluminescent vibriosis are not completely understood, several biomolecules are known to be contributing factors (Austin and Zhang, 2006). The expression of many of these virulence factors, including the type III secretion system (Henke and Bassler, 2004a), extracellular toxin (Manefield et al., 2000), metalloprotease (Mok et al., 2003), siderophore (Lilley and Bassler, 2000), chitinase (Defoirdt et al., 2010), phospholipase, caseinase, and gelatinase (Natrah et al., 2011) are known to be regulated by the quorum sensing master regulator LuxR. Our findings from the shrimp virulence model demonstrated that ΔhmgA was less virulent than the WT and led to the suggestion that this phenotype may have been due to the down-regulation of several virulence factors in ΔhmgA. However, with the exception of two [hemolysin (M892_26640) and azurin (M892_25430)], the genes encoding these factors were not differentially expressed suggesting that the decreased virulence potential of ΔhmgA was not caused by an overt down-regulation of accepted virulence factors.

The expression of bioluminescence has also been associated with virulence in shrimp (Manefield et al., 2000; Phuoc et al., 2009) and indirect evidence has suggested that bioluminescence and a toxic extracellular protein are co-regulated (Manefield et al., 2000). The molecular mechanisms of Vibrio quorum sensing and its resulting bioluminescence have been most extensively studied in V. campbellii BAA-1116 and the regulation of luxCDABEGH gene cluster responsible for bioluminescence is known to be positively regulated by the quorum sensing master regulator LuxR (Bassler et al., 1993; Henke and Bassler, 2004b; Lenz et al., 2004; Waters and Bassler, 2006; Tu and Bassler, 2007). In this study, the bioluminescence output of ΔhmgA was found to be significantly attenuated and this phenotype could be attributed to the pronounced down-regulation of luxCDABEGH in ΔhmgA (Table 2). Furthermore, the gene encoding the high cell density state quorum sensing master regulator LuxR and another quorum sensing regulator (LuxT) (Lin et al., 2000) were also significantly modulated in ΔhmgA. It is estimated that this singular effect on luxR transcript levels accounted for 40% of the transcriptional modulation seen in ΔhmgA as a comparison with the LuxR regulon (manuscript in preparation) revealed 52 modulated genes in common.

In addition to the lux bioluminescence genes, LuxR has also been shown to regulate the synthesis of storage polyhydroxybutyrates in bioluminescent vibrios (Miyamoto et al., 1998). Polyhydroxybutyrates, the most characterized member of the polyhydroxyalkanoates, are storage polyesters that are produced and accumulate in the bacterial cytosol in carbon-rich environments when other nutrients are limited (Reddy et al., 2003). When available carbon has been exhausted, these storage polymers can be catabolized for carbon and energy. In V. campbellii ΔhmgA, the expression of the polyhydroxybutyrate synthesis gene cluster (phaCDAB) was markedly reduced in comparison to the WT. Thus, a blockage of the tyrosine catabolism pathway and production of pyomelanin not only retarded amino acid degradation but also kept V. campbellii from accumulating carbon storage polymers when in a carbon-rich environment. Evidence of these nutrient management deficiencies could be seen in the late stationary phase ΔhmgA cultures (Figure 2A) where depleted carbon supplies may have contributed to diminished survival.

The transcriptional modulation of members of the LuxR quorum sensing regulon in ΔhmgA, presumably due to reduced luxR transcript levels, was unexpected as HmgA is not known to be a regulatory protein. One possible explanation for this observation may be that extracellular pyomelanin is somehow interfering with the binding of autoinducer molecules to their cognate quorum sensing histidine kinase receptors. Alternatively, membrane-embedded pyomelanin may sufficiently alter membrane structure and impair the binding of autoinducer molecules or subsequent phosphorylation cascade. In either case, the quorum sensing signaling cascade would mimic a low cell density state resulting in the phosphorylation of the response regulator LuxO and activated transcription of regulatory small RNAs (Qrr sRNAs) (Lilley and Bassler, 2000). As the base-pairing of the Qrr sRNAs to luxR transcripts results in the degradation of luxR mRNA (Lenz et al., 2004; Tu and Bassler, 2007), pyomelanization may lock the cells in a low cell density state thus, explaining the transcriptome profiling data.

Conclusions

In this study, we used the model quorum sensing bacterium V. campbellii BAA-1116 to determine how the deletion of the hmgA gene and resulting pyomelanization affected cellular phenotypes, virulence, and transcription. While the material properties of V. campbellii pyomelanin were similar to previous descriptions, there did not appear to be a generality of pyomelanin-mediated phenotypes as pyomelanization had either a neutral or deleterious effect on cell survival. Despite the fact that pyomelanin production in other pathogenic bacteria had been shown to increase their virulence and adaptation to chronicity in mammalian infection models, our results using a shrimp infection model indicated that pyomelanized V. campbellii were actually less virulent than the isogenic WT strain. These observations may be due in part to the comparatively lesser amount of pyomelanin produced and retained in V. campbellii and the effect this production had on cellular metabolism. This was supported by the first transcriptome-level analysis comparing a pyomelanin-producing mutant with its isogenic WT strain. It is also worth noting that the immune responses from different animal models (invertebrate vs. vertebrate) may also play a large role in the differences seen in virulence. V. campbellii is primarily an invertebrate animal pathogen and this is the first time that the effect of pyomelanization has been tested in an invertebrate model system (i.e., a natural host organism). The transcriptional profiles demonstrated that the deletion of the hmgA gene led to significantly lower transcript abundance levels of several important metabolic processes that disrupted cellular homeostasis and fitness in stressful environments (e.g., stationary phase). Taken together, these findings may explain why naturally pyomelanized V. campbellii or V. harveyi have not been identified from the marine environment or infected eukaryotic host organisms.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by the Office of Naval Research via U.S. Naval Research Laboratory core funds. The opinions and assertions contained herein are those of the authors and are not to be construed as those of the U.S. Navy, military service at large, or U.S. Government.

References

- Amparyup P., Charoensapsri W., Tassanakajon A. (2009). Two prophenoloxidases are important for the survival of Vibrio harveyi challenged shrimp Penaeus monodon. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 33, 247–256 10.1016/j.dci.2008.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Austin B., Zhang X. H. (2006). Vibrio harveyi: a significant pathogen of marine vertebrates and invertebrates. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 43, 119–124 10.1111/j.1472-765X.2006.01989.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassler B. L. (1999). How bacteria talk to each other: regulation of gene expression by quorum sensing. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2, 582–587 10.1016/S1369-5274(99)00025-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassler B. L., Wright M., Showalter R. E., Silverman M. R. (1993). Intercellular signalling in Vibrio harveyi: sequence and function of genes regulating expression of luminescence. Mol. Microbiol. 9, 773–786 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01737.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerenius L., Soderhall K. (2004). The prophenoloxidase-activating system in invertebrates. Immunol. Rev. 198, 116–126 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2004.00116.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charoensapsri W., Amparyup P., Hirono I., Aoki T., Tassanakajon A. (2009). Gene silencing of a prophenoloxidase activating enzyme in the shrimp, Penaeus monodon, increases susceptibility to Vibrio harveyi infection. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 33, 811–820 10.1016/j.dci.2009.01.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coyne V. E., Al-Harthi L. (1992). Induction of melanin biosynthesis in Vibrio cholerae. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 58, 2861–2865 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czyz A., Plata K., Wegrzyn G. (2002). Induction of light emission by luminescent bacteria treated with UV light and chemical mutagens. J. Appl. Genet. 43, 377–389 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czyz A., Wrobel B., Wegrzyn G. (2000). Vibrio harveyi bioluminescence plays a role in stimulation of DNA repair. Microbiology 146, 283–288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Defoirdt T., Darshanee Ruwandeepika H. A., Karunasagar I., Boon N., Bossier P. (2010). Quorum sensing negatively regulates chitinase in Vibrio harveyi. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 2, 44–49 10.1111/j.1758-2229.2009.00043.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Defoirdt T., Verstraete W., Bossier P. (2008). Luminescence, virulence and quorum sensing signal production by pathogenic Vibrio campbellii and Vibrio harveyi isolates. J. Appl. Microbiol. 104, 1480–1487 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2007.03672.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henke J. M., Bassler B. L. (2004a). Quorum sensing regulates type III secretion in Vibrio harveyi and Vibrio parahaemolyticus. J. Bacteriol. 186, 3794–3805 10.1128/JB.186.12.3794-3805.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henke J. M., Bassler B. L. (2004b). Three parallel quorum-sensing systems regulate gene expression in Vibrio harveyi. J. Bacteriol. 186, 6902–6914 10.1128/JB.186.20.6902-6914.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji P. F., Yao C. L., Wang Z. Y. (2011). Reactive oxygen system plays an important role in shrimp Litopenaeus vannamei defense against Vibrio parahaemolyticus and WSSV infection. Dis. Aquat. Organ. 96, 9–20 10.3354/dao02373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katsev A. M., Wegrzyn G., Szpilewska H. (2004). Effects of hydrogen peroxide on light emission by various strains of marine luminescent bacteria. J. Basic Microbiol. 44, 178–184 10.1002/jobm.200310330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazakov A. E., Rodionov D. A., Alm E., Arkin A. P., Dubchak I., Gelfand M. S. (2009). Comparative genomics of regulation of fatty acid and branched-chain amino acid utilization in proteobacteria. J. Bacteriol. 191, 52–64 10.1128/JB.01175-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotob S. I., Coon S. L., Quintero E. J., Weiner R. M. (1995). Homogentisic acid is the primary precursor of melanin synthesis in Vibrio cholerae, a Hyphomonas strain, and Shewanella colwelliana. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 61, 1620–1622 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozakiewicz J., Gajewska M., Lyzen R., Czyz A., Wegrzyn G. (2005). Bioluminescence-mediated stimulation of photoreactivation in bacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 250, 105–110 10.1016/j.femsle.2005.06.047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurowski B., Ludwig B. (1987). The genes of the Paracoccus denitrificans bc1 complex. Nucleotide sequence and homologies between bacterial and mitochondrial subunits. J. Biol. Chem. 262, 13805–13811 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J. H., Park N. Y., Lee M. H., Choi S. H. (2003). Characterization of the Vibrio vulnificus putAP operon, encoding proline dehydrogenase and proline permease, and its differential expression in response to osmotic stress. J. Bacteriol. 185, 3842–3852 10.1128/JB.185.13.3842-3852.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenz D. H., Mok K. C., Lilley B. N., Kulkarni R. V., Wingreen N. S., Bassler B. L. (2004). The small RNA chaperone Hfq and multiple small RNAs control quorum sensing in Vibrio harveyi and Vibrio cholerae. Cell 118, 69–82 10.1016/j.cell.2004.06.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lilley B. N., Bassler B. L. (2000). Regulation of quorum sensing in Vibrio harveyi by LuxO and sigma-54. Mol. Microbiol. 36, 940–954 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01913.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin B., Wang Z., Malanoski A. P., O'Grady E. A., Wimpee C. F., Vuddhakul V., et al. (2010). Comparative genomic analyses identify the Vibrio harveyi genome sequenced strains BAA-1116 and HY01 as Vibrio campbellii. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 2, 81–89 10.1111/j.1758-2229.2009.00100.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Y. H., Miyamoto C., Meighen E. A. (2000). Cloning and functional studies of a luxO regulator LuxT from Vibrio harveyi. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1494, 226–235 10.1016/S0167-4781(00)00236-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manefield M., Harris L., Rice S. A., De Nys R., Kjelleberg S. (2000). Inhibition of luminescence and virulence in the black tiger prawn (Penaeus monodon) pathogen Vibrio harveyi by intercellular signal antagonists. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66, 2079–2084 10.1128/AEM.66.5.2079-2084.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metcalf W. W., Jiang W., Daniels L. L., Kim S. K., Haldimann A., Wanner B. L. (1996). Conditionally replicative and conjugative plasmids carrying lacZ alpha for cloning, mutagenesis, and allele replacement in bacteria. Plasmid 35, 1–13 10.1006/plas.1996.0001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyamoto C. M., Sun W., Meighen E. A. (1998). The LuxR regulator protein controls synthesis of polyhydroxybutyrate in Vibrio harveyi. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1384, 356–364 10.1016/S0167-4838(98)00028-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mok K. C., Wingreen N. S., Bassler B. L. (2003). Vibrio harveyi quorum sensing: a coincidence detector for two autoinducers controls gene expression. EMBO J. 22, 870–881 10.1093/emboj/cdg085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakada Y., Nishijyo T., Itoh Y. (2002). Divergent structure and regulatory mechanism of proline catabolic systems: characterization of the putAP proline catabolic operon of Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 and its regulation by PruR, an AraC/XylS family protein. J. Bacteriol. 184, 5633–5640 10.1128/JB.184.20.5633-5640.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Natrah F. M., Ruwandeepika H. A., Pawar S., Karunasagar I., Sorgeloos P., Bossier P., et al. (2011). Regulation of virulence factors by quorum sensing in Vibrio harveyi. Vet. Microbiol. 154, 124–129 10.1016/j.vetmic.2011.06.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phuoc L. H., Defoirdt T., Sorgeloos P., Bossier P. (2009). Virulence of luminescent and non-luminescent isogenic vibrios toward gnotobiotic Artemia franciscana larvae and specific pathogen-free Litopenaeus vannamei shrimp. J. Appl. Microbiol. 106, 1388–1396 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2008.04107.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy C. S., Ghai R., Rashmi, Kalia V. C. (2003). Polyhydroxyalkanoates: an overview. Bioresour. Technol. 87, 137–146 10.1016/S0960-8524(02)00212-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed L. J., Muench H. (1938). A simple method of estimating fifty percent end point. Am. J. Hyg. 27, 493–497 12177528 [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Rojas A., Mena A., Martin S., Borrell N., Oliver A., Blazquez J. (2009). Inactivation of the hmgA gene of Pseudomonas aeruginosa leads to pyomelanin hyperproduction, stress resistance and increased persistence in chronic lung infection. Microbiology 155, 1050–1057 10.1099/mic.0.024745-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin R. A. (2009). A first principles approach to differential expression in microarray data analysis. BMC Bioinform. 10:292 10.1186/1471-2105-10-292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmaler-Ripcke J., Sugareva V., Gebhardt P., Winkler R., Kniemeyer O., Heinekamp T., et al. (2009). Production of pyomelanin, a second type of melanin, via the tyrosine degradation pathway in Aspergillus fumigatus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75, 493–503 10.1128/AEM.02077-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon J. (2002). Enzymology and bioenergetics of respiratory nitrite ammonification. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 26, 285–309 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2002.tb00616.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szpilewska H., Czyz A., Wegrzyn G. (2003). Experimental evidence for the physiological role of bacterial luciferase in the protection of cells against oxidative stress. Curr. Microbiol. 47, 379–382 10.1007/s00284-002-4024-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson F. L., Iida T., Swings J. (2004). Biodiversity of vibrios. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 68, 403–431 10.1128/MMBR.68.3.403-431.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tu K. C., Bassler B. L. (2007). Multiple small RNAs act additively to integrate sensory information and control quorum sensing in Vibrio harveyi. Genes Dev. 21, 221–233 10.1101/gad.1502407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turick C. E., Beliaev A. S., Zakrajsek B. A., Reardon C. L., Lowy D. A., Poppy T. E., et al. (2009). The role of 4-hydroxyphenylpyruvate dioxygenase in enhancement of solid-phase electron transfer by Shewanella oneidensis MR-1. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 68, 223–225 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2009.00670.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turick C. E., Tisa L. S., Caccavo F., Jr. (2002). Melanin production and use as a soluble electron shuttle for Fe(III) oxide reduction and as a terminal electron acceptor by Shewanella algae BrY. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68, 2436–2444 10.1128/AEM.68.5.2436-2444.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valeru S. P., Rompikuntal P. K., Ishikawa T., Vaitkevicius K., Sjoling A., Dolganov N., et al. (2009). Role of melanin pigment in expression of Vibrio cholerae virulence factors. Infect. Immun. 77, 935–942 10.1128/IAI.00929-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang R., Wang H., Zhou H., Wang Y., Yue J., Diao B., et al. (2011). Characters of homogentisate oxygenase gene mutation and high clonality of the natural pigment-producing Vibrio cholerae strains. BMC Microbiol. 11:109 10.1186/1471-2180-11-109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warrens A. N., Jones M. D., Lechler R. I. (1997). Splicing by overlap extension by PCR using asymmetric amplification: an improved technique for the generation of hybrid proteins of immunological interest. Gene 186, 29–35 10.1016/S0378-1119(96)00674-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waters C. M., Bassler B. L. (2006). The Vibrio harveyi quorum-sensing system uses shared regulatory components to discriminate between multiple autoinducers. Genes Dev 20, 2754–2767 10.1101/gad.1466506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Youngchim S., Morris-Jones R., Hay R. J., Hamilton A. J. (2004). Production of melanin by Aspergillus fumigatus. J. Med. Microbiol. 53, 175–181 10.1099/jmm.0.05421-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zughaier S. M., Ryley H. C., Jackson S. K. (1999). A melanin pigment purified from an epidemic strain of Burkholderia cepacia attenuates monocyte respiratory burst activity by scavenging superoxide anion. Infect. Immun. 67, 908–913 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]