Abstract

Objective:

The objective of this study was to evaluate the efficacy and safety of giving general anesthesia without the use of any opioids either systemic or intraperitoneal in bariatric surgery.

Methods:

Prospective randomized controlled trial. Obese patients (body mass index >50 Kg/m2) undergoing laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomies were recruited and provided an informed signed consent. Patients were randomized using a computer generated randomization table to receive either opioid or non-opioid based anesthesia. The patient and the investigator scoring patient outcome after surgery were blinded to the anesthetic protocol. Primary outcomes were hemodynamics in the form of “heart rate, systolic, diastolic, and mean arterial blood pressure” on induction and ½ hourly thereafter. Pain monitoring through visual analog scale (VAS) 30 min after recovery, hourly for 2 h and every 4 h for 24 h was also recorded. Pain monitoring through VAS and post-operative nausea and vomiting 30 min after recovery were also recorded and finally patient satisfaction and acute pain nurse satisfaction.

Results:

There was no difference in background characteristics in both groups. There were no statistically significant differences in different outcomes as heart rate, mean blood pressure, O2 saturation in different timings between groups at any of the determined eight time points but pain score and nurse satisfaction showed a trend to better performance with non-opioid treatment.

Conclusion:

Nonopioid based general anesthesia for Bariatric surgery is as effective as opioid one. There is no need to use opioids for such surgery especially that there was a trend to less pain in non-opioid anesthesia.

Keywords: Bariatric anesthesia, ketamine anesthesia, narcotic anesthesia, non-narcotic anesthesia, pediatric anesthesia

INTRODUCTION

Obesity is a significant health problem with clearly established health implications, including an increased risk for coronary artery disease, hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes mellitus, gallbladder disease, degenerative joint disease, obstructive sleep apnea, and psychosocial impairment.[1] The body mass index (BMI), calculated as the weight in kilograms divided by the height in meters squared, has been used in clinical and epidemiological studies as a predictor of health risk.[2] A BMI of 25 Kg/m2 is considered normal, >30 Kg/m2 obese, >35 Kg/m2 morbidly obese and >55 Kg/m2 super morbidly obese. Morbidly obese patients with BMI of ≥40 or 35 with co-morbidities are undergoing many surgical procedures for weight loss.[3]

Obese patients are notoriously known for pulmonary problems that may get worse with general anesthesia. Opioids given intraoperatively as well as post-operatively could play a significant part in post-operative pulmonary morbidity. On one side, post-operative pain ranges from mild to moderate and for a short period of less than 24 h in laparoscopic surgery.[4] On the other side, opioids may not be highly effective in alleviating such pain without causing much sedation, and impending rapid recovery and early mobilization. Therefore, the objective of the present prospective, randomized, double-blind study was to evaluate the efficacy and safety of giving general anesthesia without the use of any opioids either systemic or intraperitoneal in bariatric surgery.

METHODS

After approval of Ethics and Research Committee of the Anesthesiology Department in Cairo University and obtaining written informed signed consent from each patient, this study has enrolled 28 obese patients (BMI >50 Kg/m2) undergoing laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy performed at Kasr El-Aini Hospital. Exclusion criteria were: Age <18 year, a positive pregnancy test, patients with a history of drug abuse or who were dependent on opioid drugs, patients with chronic pain, or patients with severe cardiac, pulmonary, liver or neurological disease.

Randomization

Patients were randomized using a computer generated randomization table to receive either opioid or non-opioid based anesthesia. The patient and the investigator scoring patient outcome after surgery were blinded to the anesthetic protocol.

Interventions

Pre-operatively, all patients will receive Ranitidine 50 mg as H2 receptor antagonist, Metoclopramide 10 mg Intra- venous (IV) and dexamethasone 8 mg IV as Post Operative Nausea and Vomitting (PONV) prophylaxis, and Midazolam 10 mg Oral for sedation. After proper assessment of the airway and anticipation of difficult airway, preoxygenation with 100% O2 on 8 L/min for 3 min via face mask is started, patients in the non-opioid group, co-induction of Propofol 2 mg/Kg and analgesic dose of Ketamine 0.5 mg/Kg, Rocuronium 0.5 mg/Kg followed by intubation.

Patients in the opioid group, co-induction of Propofol 2 mg/Kg and analgesic dose of Fentanyl 2-5 mcg/Kg, Rocuronium 0.5 mg/Kg followed by intubation.

For both groups ventilation with tidal volumes of 10-12 mL/Kg to avoid barotraumas and respiratory rates of up to 12-14 breaths/min to maintain normocapnia and Positive End Expiratory Pressure (PEEP) of 5-10 cm H2O. Then anesthesia was maintained for non-opioid group by sevoflurane, 2-4%, Ketamine infusion of 0.5 mg/Kg/h of ideal body weight.

For opioid group anesthesia was maintained by sevoflurane, 2-4%, Fentanyl infusion of 0.025-0.25 mcg/Kg/min of ideal body weight.

Ideal body weight was calculated in men as: Ideal body weight (in Kg) =50±2.3 Kg/2.5 cm over 160 cm, women: Ideal body weight (in Kg) =45.5±2.3 Kg/2.5 cm over 160 cm.

At the end, all patients will be extubated then sent to the recovery room with an order for analgesics as follow:

For non-opioid group

Paracetamol 1 g/6 h IV for 24 h, Dicofenac 75 mg/12 h IM for 48 h, Tramadol 50-100 mg/12 h IV prn for 24 h, Tramadol patient-controlled analgesia (PCA), concentration 10 mg/ml, Dose 1 ml, lock-out period 6 min and no basal infusion.

For opioid group

Paracetamol 1 g/6 h IV for 24 h, Fentanyl PCA, Concentration 10 mcg/ml, Dose 1 ml, lock-out interval 6 min.

For both groups, rescue medication, standing order of Morphine 2-4 mg/2 h prn IV in case of failure of this technique.

Outcome measures

Our primary outcomes were hemodynamics in the form of “heart rate (HR), Systolic, Diastolic, and Mean arterial blood pressure” on induction and ½ hourly thereafter. Pain monitoring through visual analog scale 30 min after recovery, hourly for 2 h and every 4 h for 24 h was also recorded.

Post-operative nausea and vomiting 30 min after recovery were also recorded and finally patient satisfaction and acute pain nurse satisfaction after 24 h were recorded.

Statistical analysis was performed using the Student's t-test. P<0.05 was considered statistically significant. The results are expressed as mean±standard deviation. All statistical calculations were carried out using the computer program Statistical Package for the Social Science (SPSS); SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) version 15 for Microsoft Windows.

RESULTS

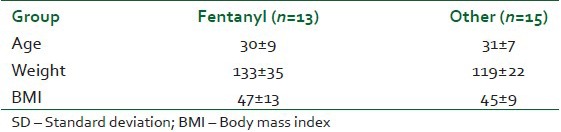

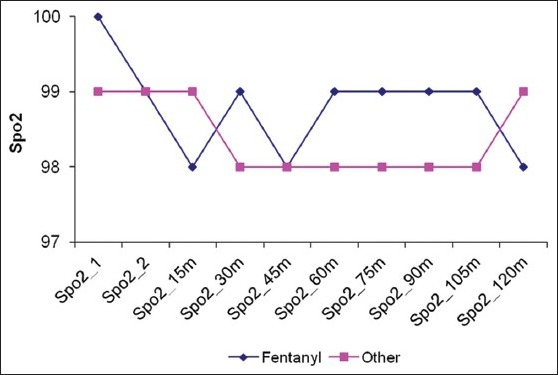

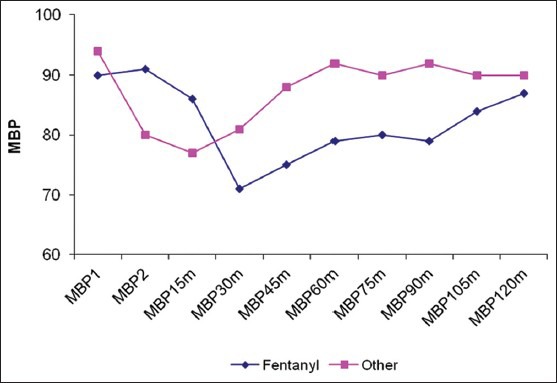

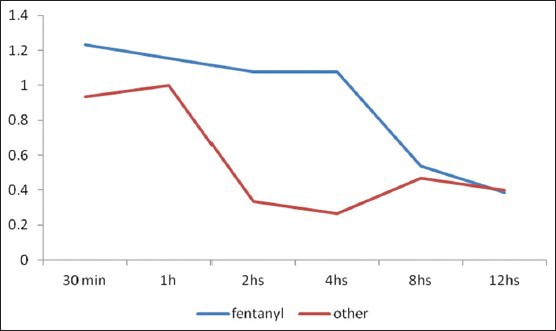

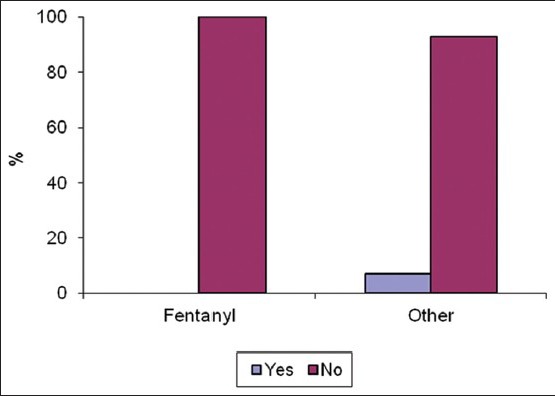

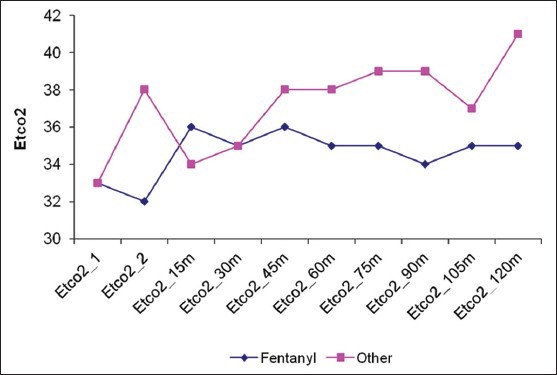

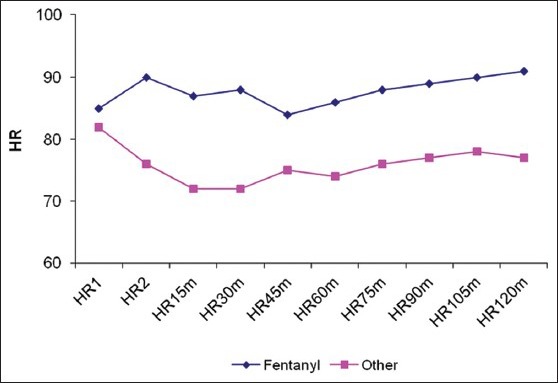

Twenty eight patients met our inclusion criteria were randomized into two groups: Opioid group: Having narcotic analgesics (n=15), non-opioid group: Having non-narcotic analgesics (n=13). No patient was dropped from the study after randomization. The two groups were found to be similar in terms of age, BMI, duration of surgery [Table 1]. There were no statistically significant differences in different outcomes as heart rate, mean blood pressure, O2 saturation and end-tidal Co2 in different timings between groups at any of the determined time points [Figures 1–4]. However, pain score [Figure 5] and nurse satisfactions [Table 2] showed a trend to better performance with non-opioid treatment. Hallucinations were reported in 7.14% of patients in non-opioid group versus non in opioid group [Table 2, Figure 6].

Table 1.

Patient characteristics data are presented as mean and SD

Figure 1.

Oxygen saturation (Spo2) in both groups

Figure 4.

Mean Arterial Blood Pressure (MBP) in both groups

Figure 5.

Pain Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) in both groups

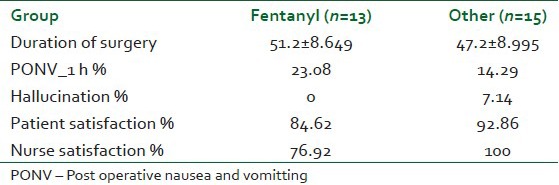

Table 2.

Comparison between both groups regarding different outcomes

Figure 6.

Hallucination in both groups

Figure 2.

End-Tidal Carbon dioxide (Etco2) in both groups

Figure 3.

Heart Rate in both groups

DISCUSSION

The role of well-planned pain management has been crucial in decreasing morbidity after major surgery especially in obese patients.[5] Opioid narcotics have ventilatory depressing effects, suggesting that alternative analgesics or sedatives may improve the management of morbidly obese patients.[6] Combining an adjunct drug in i.v. PCA as a convenient regimen for pain management is gaining worldwide popularity in current clinical practice. Various adjunct drugs, including, antiemetic,[7] non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs,[8] three pure opioid-antagonist,[9] opioid agonist–antagonist, and Ketamine have been used in such a multimodal effort.[10]

The present study was carried out to explore the value of non-opioid general anesthesia in morbidly obese patients. To evaluate the efficacy and safety of giving general anesthesia without the use of any opioids either systemic or intraperitoneal in bariatric surgery, we compared a narcotic free technique with a fentanyl infusion that has previously been shown to be effective in this population[11] and were concerned that a higher dose carried an excessive risk of post-operative respiratory depression in morbidly obese patients. To eliminate the possibility of bias, the study was randomized controlled and the method of randomization was true one using the computer generated table. Moreover, the investigators were blinded to the interventions. This ensures high quality of the work carried out. As morbidly obese patients with BMI >50 is not common, the number of participants was limited to 30 patients. Because of the nature of the procedure, there was no drop out cases in this study.

In the present study, there was no significant difference between the two groups regarding their background characteristics. This demonstrates proper randomization and adequate adherence to the protocol. There was also no difference between different outcomes except for the patient satisfaction and nurse satisfaction, where is there was a trend for better satisfaction in the non-opioid group, but did not reach statistical significance.

Our results matches with other investigators who found concern over opioid-related side-effects limited morphine administration in the Post Anesthesia Care Unit (PACU) and were likely to have caused under-treatment of post-operative pain. Sedated patients in pain in the PACU were likely to have had poor pain control for at least the first 24 post-operative hours, and less likely to be satisfied with the overall pain care provided during the first 24 post-operative hours.[12] Other investigators found results similar to ours, but reached statistical significance where they observed that dexmedetomidine treatment during open gastric bypass surgery decreased blood pressure, heart rate, and desflurane anesthetic requirement during surgery and decreased pain level and morphine use in the PACU compared with fentanyl. The decrease in morphine use in dexmedetomidine-treated patients may be important for attenuating the risk of narcotic-induced post-operative respiratory depression and hypoxemia in patients after open gastric bypass surgery.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, non-opioid based general anesthesia for bariatric surgery is as effective as opioid one. There is no need to use opioids for such surgery, especially that there was a trend to less pain in non-opioid anesthesia.[13]

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Fernandez AZ, Jr, Demaria EJ, Tichansky DS, Kellum JM, Wolfe LG, Meador J, et al. Multivariate analysis of risk factors for death following gastric bypass for treatment of morbid obesity. Ann Surg. 2004;239:698–702. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000124295.41578.ab. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ukleja A, Stone RL. Medical and gastroenterologic management of the post-bariatric surgery patient. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2004;38:312–21. doi: 10.1097/00004836-200404000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nguyen NT, Lee SL, Goldman C, Fleming N, Arango A, McFall R, et al. Comparison of pulmonary function and postoperative pain after laparoscopic versus open gastric bypass: A randomized trial. J Am Coll Surg. 2001;192:469–76. doi: 10.1016/s1072-7515(01)00822-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Feld JM, Hoffman WE, Stechert MM, Hoffman IW, Ananda RC. Fentanyl or dexmedetomidine combined with desflurane for bariatric surgery. J Clin Anesth. 2006;18:24–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2005.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Feld JM, Laurito CE, Beckerman M, Vincent J, Hoffman WE. Non-opioid analgesia improves pain relief and decreases sedation after gastric bypass surgery. Can J Anaesth. 2003;50:336–41. doi: 10.1007/BF03021029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Holmes J, Maye JP. Postoperative respiratory depression and unresponsiveness following epidural opiate administration: A case report. AANA J. 2004;72:126–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lin TF, Yeh YC, Yen YH, Wang YP, Lin CJ, Sun WZ. Antiemetic and analgesic-sparing effects of diphenhydramine added to morphine intravenous patient-controlled analgesia. Br J Anaesth. 2005;94:835–9. doi: 10.1093/bja/aei137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen JY, Wu GJ, Mok MS, Chou YH, Sun WZ, Chen PL, et al. Effect of adding ketorolac to intravenous morphine patient-controlled analgesia on bowel function in colorectal surgery patients – A prospective, randomized, double-blind study. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2005;49:546–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2005.00674.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cepeda MS, Alvarez H, Morales O, Carr DB. Addition of ultralow dose naloxone to postoperative morphine PCA: Unchanged analgesia and opioid requirement but decreased incidence of opioid side effects. Pain. 2004;107:41–6. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2003.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yeh YC, Lin TF, Lin FS, Wang YP, Lin CJ, Sun WZ. Combination of opioid agonist and agonist-antagonist: Patient-controlled analgesia requirement and adverse events among different-ratio morphine and nalbuphine admixtures for postoperative pain. Br J Anaesth. 2008;101:542–8. doi: 10.1093/bja/aen213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gaszynski TM, Strzelczyk JM, Gaszynski WP. Post-anesthesia recovery after infusion of propofol with remifentanil or alfentanil or fentanyl in morbidly obese patients. Obes Surg. 2004;14:498–503. doi: 10.1381/096089204323013488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Michelet P, Guervilly C, Hélaine A, Avaro JP, Blayac D, Gaillat F, et al. Adding ketamine to morphine for patient-controlled analgesia after thoracic surgery: Influence on morphine consumption, respiratory function, and nocturnal desaturation. Br J Anaesth. 2007;99:396–403. doi: 10.1093/bja/aem168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lentschener C, Tostivint P, White PF, Gentili ME, Ozier Y. Opioid-induced sedation in the postanesthesia care unit does not insure adequate pain relief: A case-control study. Anesth Analg. 2007;105:1143–7. doi: 10.1213/01.ane.0000281441.93304.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]