Abstract

Context:

Majority of health professionals have unfavorable attitudes towards patients presenting with self-harm, which further compromises their willingness and outcome of care.

Aims:

To assess the nursing students’ attitudes toward suicide attempters.

Settings and Design:

Cross-sectional study was conducted in two nursing colleges of north India.

Material and Methods:

Three hundred and eight nursing students were recruited through total enumeration method from May to June 2012. ‘Suicide opinion questionnaire’ was administered to assess their attitudes towards suicide attempters.

Statistical Analysis Used:

Descriptive statistics was employed with Statistical Package for Social Sciences version 14.0 for Windows.

Results:

Majority were single females, from urban locality, with the mean age of 20 years. Only minority had previous exposure to suicide prevention programs and management of such cases. Majority of students agreed for mental illness, disturbed family life, and depression as major push to attempt suicide. They held favorable attitude for half of the attitudinal statement, but they were uncertain for rest half of the statements.

Conclusions:

They generally had favorable attitude towards suicide attempters. Their uncertain response highlights the need for enhancing educational exposure of nursing students and new staff at the earliest opportunity, to carve their favorable attitude towards patients presenting with self-harm.

Keywords: Attitudes, nurses, nursing students, self-harm, suicide

Introduction

Current suicide rate in India is 11.2 per 100,000 population[1] and nearly three-fourth of suicide is reported in persons <44 years, which further contribute to significant social and economic burden.[2] Suicide is the most preventable cause of death among the top 20 leading causes of mortality for all ages.[3]

Suicide attempters not only present with multiple medical and administrative problems, but also pose considerable strain on busy medical and nursing staff.[4] Research evidence has indicated that unfavorable attitudes among doctors and nurses exist towards suicide attempters, which further influence their suicide risk assessment, management skills, including the quality and impact of care.[5,6]

Suicide is a multifaceted problem and hence management of patients with self-harm should also be multidimensional.[7] In this regard, nurses have the highest level of contact with patients and their attitudes, and knowledge about self-harm, may further influence their willingness and ability to deliver effective care.[8] Thus, studying the nurses’ attitude towards suicide attempters has paramount importance in understanding and addressing the existing gaps in healthcare delivery system. The data is limited in this area[5,9] and we could not find any such study in nursing population from India. Hence, this study was aimed to assess the nursing students’ attitude toward suicide attempters.

Materials and Methods

Study design: Cross-sectional

Nursing students pursuing either General Nursing and Midwifery or Bachelor of Science (BSc) course were recruited from two nursing colleges of north India in May 2012. Total enumeration method was employed, in which all the students were recruited to maintain high level of accuracy and to provide a complete statistical coverage. Study was approved by the college authorities. Study proforma, containing sociodemographic profile sheet and suicide opinion questionnaire (SOQ), were distributed in classroom setting. Students were explained about the study aim and subsequently written informed consent was taken from all the subjects. They were also asked to read the questionnaire first and ask in case of problem in understanding any question. After answering their queries, they were asked to fill the questionnaire, for which they took nearly 30 min.

Following instruments were administered

Sociodemographic profile sheet

It included students’ demographic profile along with their additional information about attending any suicide awareness/prevention workshop as well as experience of managing/observing patients with self-harm.

SOQ

It is a 52-item, self-rated, and 5-point Likert scale which measures suicide attitude on the basis of five factors: Acceptability, perceived factual knowledge, social disintegration, personal defects, and emotional perturbation.[10,11] It has been used in several studies.[12,13,14,15,16] Factor analysis revealed that the 15 factors accounted for 77% of the total variance.[17] Its psychometric reliability and validity have been established.[10,11,17,18,19]

Statistical analysis

Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 14.0 for Windows (Chicago, Illinois, USA) was used. For sociodemographic profile, frequencies with percentages were calculated for categorical variables and mean and standard deviation were calculated for continuous variables.

Attitudinal statements were scored on a 5-point Likert scale: 1. ‘Strongly agree’, 2. ‘agree’, 3. ‘don’t know’, 4. ‘disagree’, and 5. ‘strongly disagree’. Means and standard deviations (SDs) were also calculated to categorize attitudes into ‘favorable’, ‘unfavorable’, and ‘uncertain’ and t-test was administered for comparing mean attitude scores among two groups. Scores between 1 and 2.4 were considered ‘positive dispositions’ or ‘favorable attitude’, between 2.5 and 3.4 ‘unsure’ or ‘uncertain attitude’, and 3.5 and above ‘negative dispositions’ or ‘unfavorable attitude’.[14] The descriptors were reversed for negatively-worded items.[14]

Results

Sociodemographic profile

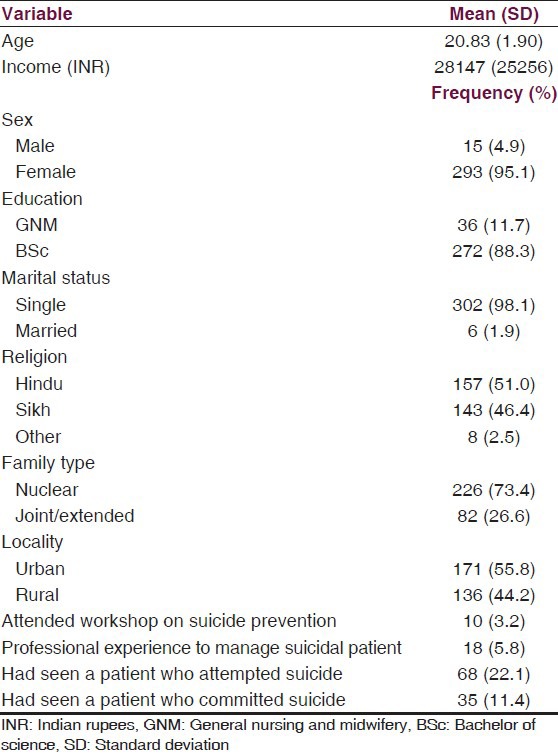

As shown in Table 1, total sample consist of 308 nursing students from two institutes. Majority were single females, from nuclear family, who were pursuing BSc Nursing with the mean age of 20.38 years (range 18-29 years). Students from both the institutes were comparable for sociodemographic profile. Only minority of students had previous exposure to attend any workshops or education forum on management of patients with self-harm and suicide prevention. Again minority of students had actually managed or observed patients with self-harm.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic profile

Attitude towards suicide attempters

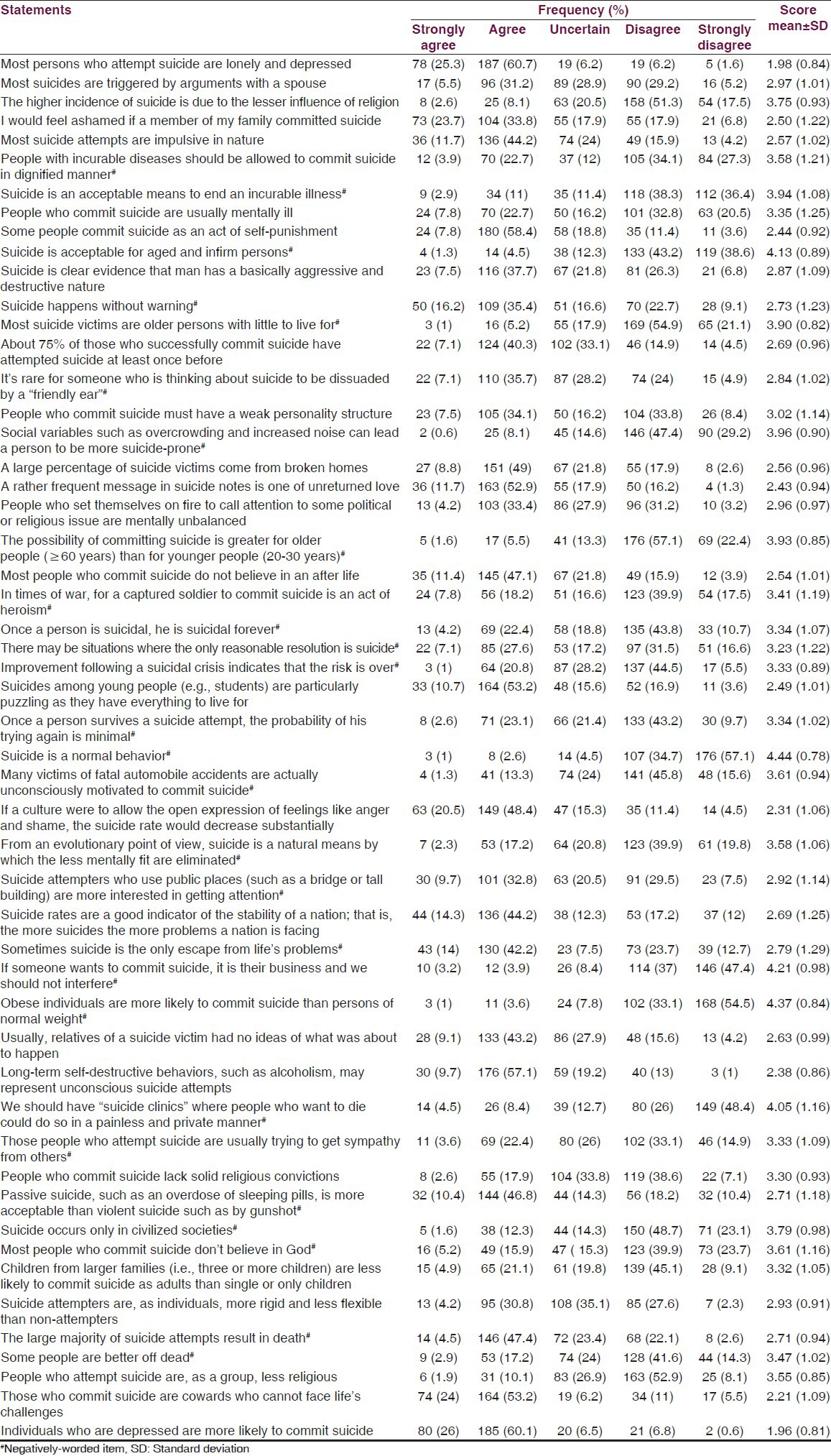

As detailed in Table 2; majority of the students considered mental illness, disturbed interpersonal relationships, unreturned love, and depression as major push for suicide. Nearly half of the students believed that suicidal attempters were impulsive, self-punitive, and nonbelievers in after life. One-third of students considered those people as rigid, weak in personality, mentally ill, and interested to get public attention.

Table 2.

Attitude towards suicide attempters

Attitude scores were derived for individual items and based on those scores attitudes were categorized into three categories: ‘Positive disposition’ or ‘favorable attitude’, ‘unsure’ or ‘uncertain attitude’, and ‘negative disposition’ or ‘unfavorable attitude’. The descriptors were reversed for negatively-worded items. For half of the items, the students showed favorable attitudes towards suicide attempters. They showed positive disposition by agreeing with nine items: Majority of suicide attempters were lonely and depressed; I would have been ashamed if a member of my family committed suicide; some of the suicide attempts were act of self-punishment; unreturned love was a main content in suicide notes; suicide among students was puzzling as they had everything to live for; suicide rates were going to reduce substantially on allowing them for emotional expression; alcoholism and other self-destructive behaviors were different forms of unconscious suicide attempts; suicide attempters were cowards; and depressed individuals were more commonly attempting suicide [Table 2].

Positive disposition towards suicide attempters were also shown by disagreement with 16 negatively-worded items: People with incurable diseases should be allowed for suicide in dignified manner; suicide was an acceptable measure to end an incurable illness as well as for aged and infirm persons; most of suicide victims were older with little to live for; overcrowding and increased noise could enhance suicide risk; possibility of suicide attempts was greater in older than younger population; suicide by captured soldier was considered as an heroic act; suicide was a normal behavior; many fatal automobile accidents were unconscious suicide attempts; suicide was a natural measure to eliminate mentally unfit; if anyone wanted to attempt suicide, one should not be interfered; obese individual were more likely to attempt suicide; suicide clinics should be established where interested individuals could die in a painless and private manner; suicide was occurring only in civilized societies; most of suicide attempters were atheist; and some people were better off dead. Students showed negative disposition or unfavorable attitudes for following two somewhat similar items: Higher suicide rates were because of lesser religious influence and suicide attempters were less religious people [Table 2].

Students had uncertain responses for the remaining 25 attitudinal statements as presented with mean attitude score from 2.5 to 3.4 [Table 2]. Thus, overall their attitude towards suicide attempters remained favorable for half of the attitudinal statements and uncertain for rest half of the items.

Relationship between respondents’ characteristics and attitude

Institute

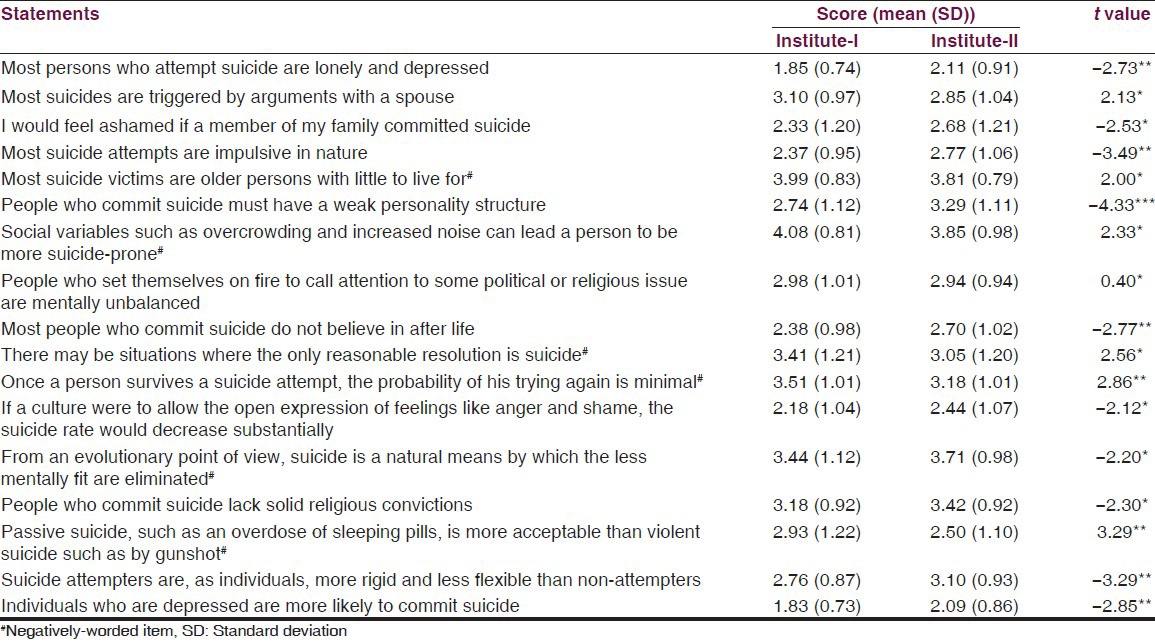

As shown in Table 3, attitudes scores among students from both the institutes were significantly different for 17 attitudinal statements [Table 3]. By and large, students from institute – I were having more positive and less uncertain attitude compared to their peers in another institute. The same group was apparently more knowledgeable about suicide and suicide attempters.

Table 3.

Attitudes towards suicide attempters: Comparison of two institutes

Gender

Compared to females, males had more favorable attitude for following four items: I would have been ashamed if a member of my family committed suicide (1.47 ± 0.74 vs. 2.56 ± 1.22, t = −3.42**); most suicide attempts were impulsive in nature (1.93 ± 0.59 vs. 2.60 ± 1.03, t = −2.47*); suicide rates were going to reduce substantially on allowing them for emotional expression (1.67 ± 0.81 vs. 2.34 ± 1.06, t = −2.43*); and sometimes suicide was the only escape from life's problems (4.27 ± 0.88 vs. 2.71 ± 1.27, t = 4.67***).

Religion

Compared to students of Hindu religion, Sikh students had more favorable attitude for following eight attitudinal items: Most suicide attempters were lonely and depressed (1.83 ± 0.72 vs. 2.13 ± 0.91, t = −3.16**); I would have been ashamed if a member of my family committed suicide (2.35 ± 1.25 vs. 2.65 ± 1.81, t = −2.15*); most suicide attempts were impulsive in nature (2.42 ± 0.98 vs. 2.71 ± 1.04, t = −2.55*); overcrowding and increased noise could enhance suicide risk (4.11 ± 0.81 vs. 3.83 ± 0.96, t = 2.71**); suicide survivors were having minimal probability for subsequent suicide attempts (3.48 ± 1.01 vs. 3.22 ± 1.02, t = 2.25*); most of suicide attempters were nonbelievers in after life (2.39 ± 1.0 vs. 2.68 ± 1.0, t = −2.53*); suicide clinics should be established where interested individuals could die in a painless and private manner (4.21 ± 1.08 vs. 3.90 ± 1.22, t = 2.38*); and depressed individuals were more likely to attempt suicide (1.82 ± 0.69 vs. 2.10 ± 0.89, t = −3.0**).

Family

Compared to students from nuclear families, students from joint/extended families were more strongly disagreed in considering suicide as an acceptable measure to end incurable illness (4.15 ± 0.97 vs. 3.87 ± 1.12, t = 2.0*).

Locality

Compared to students from urban locality, students from rural locality had more favorable attitude for two attitudinal items: People with incurable diseases should have been allowed to commit suicide in dignified manner (3.80 ± 1.13 vs. 3.44 ± 1.24, t = 2.32*); and suicide was acceptable for aged and infirm persons (4.25 ± 0.86 vs. 3.99 ± 0.93, t = 2.19*).

Discussion

Suicide is a complex human behavior as well as multifaceted health problem.[7] Patients with self-harm pose a significant challenge to healthcare delivery system. They also face negative attitude of hospital staff in most medical and surgical settings. The more negative attitude expressed towards repeated attempters of self-harm, which is really alarming as this population has significantly higher risk of subsequent self-harm.[20,21] This highlights the importance of increasing the knowledge and understanding of health professionals’ about patients with self-harm.

Nursing students reflect a group of future gatekeepers, insofar as they might have first contact with subjects with self-harm in their professional life. Nursing professionals’ attitude toward this population is immensely important because their willingness to help such patients affect the content and outcome of care.[22,23]

Similar to earlier reports;[9,15] weak interpersonal skills and relations, mental illness, and disturbed family life were commonly thought triggers for suicide in our study. Majority of students considered association of lack of emotional expression, difficulty in facing life's challenges and depression with suicide. Nearly half of students believed that persons with suicidal attempts were impulsive, self-punitive, and nonbelievers in after life.

Generally, our respondents held favorable attitude towards patients presenting with self-harm, which is consistent with the findings of McLaughlin[24] and Anderson[25], but contrasts with those of McAllister, et al.,[26] who found negative attitudes predominantly. But they were uncertain for nearly half of the attitudinal statements. This may be due to several factors, such as lack of education and experience of managing patients with self-harm, younger age, and ambivalence towards this clinical population.[26]

More than half of the students did not consider permanency of suicidal ideation, which revealed a sense of hope for suicide attempters. Similar to earlier studies,[14,27] majority of our students were disagreed with primary motive of self-harm act was gaining sympathy.

In our study, male students had more favorable attitude than female students for some attitudinal items, while other studies[12,28,29] reported more positive attitudes in female staff. Similar to a study,[30] majority of our students considered suicide as an impulsive behavior.

It is unclear whether age of staff and experience to manage individuals with self-harm influence attitudes. As greater experience was found to be associated with improvements in attitude in psychiatric setting,[29,31,32] but not in general hospital setting.[28,33] Greater education was more consistently associated with positive attitudes.[34,35] Our mean attitude scores were similar to other study.[9] but we could not find any of such association as our subject was nearly of same age, with limited clinical experience and minority has attended any workshop/lecture on suicide prevention.

Majority of our respondents were disagreeing with the statements that people who attempt suicide were atheist or lacking solid religious convictions. Our findings are similar to earlier reports,[12,13] but one study[30] found strong agreement for these statements. Similar to earlier findings,[13] most of our students were disagreed about acceptability of suicide as normal behavior, even not for aged and infirm persons.

There was a paucity of studies of cultural variations of health professionals’ attitude towards suicide and suicide attempters. One study[36] found much similarity between the attitudes held by doctors from the UK and Israel. Another study[37] reported very restrictive attitude of medical students in Madras (India), rejecting the right to commit suicide; while on the other hand, in Vienna (Austria) a more permissive attitude was found.

In an Indian study, majority of the suicide survivors perceived that their suicidal attempt could have been prevented.[3] A recent review of patient experiences of self-harm services[38] emphasized their negative experiences with inappropriate staff behavior, lack of staff knowledge, and perceived lack of involvement in management decision. Another Indian study found significant positive attitude among mental health professionals compared to nonmental health professionals and concluded that the simple training and education of nonmental health professional could change their attitudes.[39]

The results of our study must be seen within its limitations. Our findings cannot be generalized as the samples were recruited from only two educational institutes. Attitude towards suicide prevention scale is not adapted for Indian population. Solely using quantitative method had inherent limitation of restricting responses to the given options. As only minority of students have attended specific lectures on suicide and had experience of managing suicide attempters, thus we could not establish any association between these variables and their attitudes. Similarly, we could not collect information about respondents’ personal or family history of any suicidal idea or acts.

However, with these limitations the study leads to the following conclusions. Weak interpersonal skills/relations, mental illness, and disturbed family life were commonly thought triggers for suicide. Only minority had previous exposure to workshops regarding management of suicidal patients and suicide prevention programs. They held favorable attitude for half of the attitudinal statement, but they were uncertain for rest half of the statements.

Future studies should assess various health professionals’ attitude towards patients with self-harm with large sample size in different clinical and community settings. Researchers should also incorporate qualitative methods, such as detailed interviews and examine relationships between professionals’ attitude towards suicide and their demographic, clinical, and other parameters such as social support, coping skills, spiritual values, religious beliefs, psychosocial stressors, personal or family history of suicidal behaviors, etc.

These findings have implications for changing nurses’ attitudes towards patients with self-harm. It may be considered by enhancing educational exposure of nursing students or new staff at the earliest opportunity through regular training programs/workshops, improving their awareness, knowledge, and communications and clinical skills for managing suicidal patients with the help of easily understandable and implementable suicide risk assessment methods. Such formal training should be made available to all medical and paramedical students, and clinical staff at their first entry. Regular clinical supervision and ongoing support of budding health professional will definitely ameliorate their worries and difficulties in working with suicide attempters.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.National crime records bureau. Accidental deaths and suicides in India: ADSI. 2011. [Last accessed on 2012 Nov 10]. Available from: http://ncrb.nic.in/CD-ADSI2011/suicides-11.pdf .

- 2.Vijayakumar L. Indian research on suicide. Indian J Psychiatry. 2010;52:291–6. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.69255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ram D, Darshan MS, Rao T, Honagodu AR. Suicide prevention is possible: A perception after suicide attempt. Indian J Psychiatry. 2012;54:172–6. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.99535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sethi S, Uppal S. Attitudes of clinicians in emergency room towards suicide. Int J Psych Clin Prac. 2006;10:182–5. doi: 10.1080/13651500600633543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ouzouni C, Nakakis K. Attitudes towards attempted suicide: The development of a measurement tool. Health Science J. 2009;3:222–31. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Saunders KE, Hawton K, Fortune S, Farrell S. Attitudes and knowledge of clinical staff regarding people who self-harm: A systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2012;139:205–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vijayakumar L. Suicide and its prevention: The urgent need in India. Indian J Psychiatry. 2007;49:81–4. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.33252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Anderson M, Standen P, Noon J. Nurses’ and doctors’ perceptions of young people who engage in suicidal behaviour: A contemporary grounded theory analysis. Int J Nurs Stud. 2003;40:587–97. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7489(03)00054-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McCann T, Clark E, McConnachie S, Harvey I. Accident and emergency nurses’ attitudes towards patients who self-harm. Accid Emerg Nurs. 2006;14:4–10. doi: 10.1016/j.aaen.2005.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rogers JR, DeShon RP. A reliability investigation of the eight clinical scales of the suicide opinion questionnaire. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 1992;22:428–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rogers JR, DeShon RP. Cross-validation of the five-factor interpretive model of the suicide opinion questionnaire. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 1995;25:305–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Anderson M, Standen P, Nazir S, Noon J. Nurses’ and doctors’ attitudes towards suicidal behaviour in young people. Int J Nurs Stud. 2000;37:1–11. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7489(99)00057-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Anderson M, Standen P. Attitudes towards suicide among nurses and doctors working with children and young people who self-harm. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2007;14:470–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2850.2007.01106.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McCann TV, Clark E, McConnachie S, Harvey I. Deliberate self-harm: Emergency department nurses’ attitudes, triage and care intentions. J Clin Nurs. 2007;16:1704–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2006.01555.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim SN, Lee KS, Lee SY, Yu JH, Hong AR. Awareness and attitude toward suicide in community mental health professionals and hospital workers. J Prev Med Public Health. 2009;42:183–9. doi: 10.3961/jpmph.2009.42.3.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chan SW, Chien WT, Tso S. Evaluating nurses’ knowledge, attitude and competency after an education programme on suicide prevention. Nurse Educ Today. 2009;29:763–9. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2009.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Domino G, Moore D, Westlake L, Gibson L. Attitudes toward suicide: A factor analytic approach. J Clin Psychol. 1982;38:257–62. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(198204)38:2<257::aid-jclp2270380205>3.0.co;2-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Domino G. Test-retest reliability of the Suicide Opinion Questionnaire. Psychol Rep. 1996;78:1009–10. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1996.78.3.1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kodaka M, Postuvan V, Inagaki M, Yamada M. A systematic review of scales that measure attitudes toward suicide. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2011;57:338–61. doi: 10.1177/0020764009357399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Owens D, Horrocks J, House A. Fatal and non-fatal repetition of self-harm: Systematic review. Br J Psychiatry. 2002;181:193–9. doi: 10.1192/bjp.181.3.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zahl D, Hawton K. Repetition of deliberate self-harm and subsequent suicide risk: Long-term follow-up study of 11583 patients. Br J Psychiatry. 2004;185:70–5. doi: 10.1192/bjp.185.1.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hawton K, Marsack P, Fagg J. The attitudes of psychiatrists to deliberate self- poisoning: Comparisonwith physician and nurses. Br J Med Psychol. 1981;54:341–8. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8341.1981.tb02572.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rayner GC, Allen SL, Johnson M. Countertransference and self-injury: A cognitive behavioural cycle. J Adv Nurs. 2005;50:12–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2005.03344.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McLaughlin C. Casualty nurses’ attitudes to attempted suicide. J Adv Nurs. 1994;20:1111–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1994.20061111.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Anderson M. Nurses’ attitudes towards suicidal behaviour: A comparative study of community mental health nurses and nurses working in an accident and emergency department. J Adv Nurs. 1997;25:1283–91. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1997.19970251283.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McAllister M, Creedy D, Moyle W, Farrugia C. Nurses’ attitudes towards clients who self-harm. J Adv Nurs. 2002;40:578–86. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2002.02412.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Slaven J, Kisely S. Staff perceptions of care for deliberate self-harm patients in rural western Australia: A qualitative study. Aust J Rural Health. 2002;10:233–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1584.2002.00487.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ghodse AH. The attitudes of casualty staff and ambulance personnel towards patients who take drug overdoses. Soc Sci Med. 1978;12:341–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Samuelsson M, Asberg M, Gustavsson JP. Attitudes of psychiatric nursing personnel towards patients who have attempted suicide. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1997;95:222–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1997.tb09623.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Domino G, Perrone L. Attitudes toward suicide: Italian and United States physicians. Omega. 1993;27:195–206. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gurrister L, Kane R. How therapists perceive and treat suicidal patients. Community Ment Health J. 1978;14:3–13. doi: 10.1007/BF00781306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Huband N, Tantam D. Attitudes to self-injury within a group of mental health staff. Br J Med Psychol. 2000;73:495–504. doi: 10.1348/000711200160688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Friedman T, Newton C, Coggan C, Hooley S, Patel R, Pickard M, et al. Predictors of A and E staff attitudes to self-harm patients who use self-laceration: Influence of previous training and experience. J Psychosom Res. 2006;60:273–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2005.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Commons Treloar A, Lewis A. Professional attitudes towards deliberate self-harm in patients with borderline personality disorder. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2008;42:578–84. doi: 10.1080/00048670802119796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sun FK, Long A, Boore J. The attitudes if casualty nurses in Taiwan to patients who have attempted suicide. J Clin Nurs. 2007;16:255–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2005.01479.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ramon S, Breyter C. Attitdudes towards self-poisoning among British and Israeli doctors and nurses in a psychiatric hospital. Isr Ann Psychiatr Relat Discip. 1978;16:206–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Etzersdorfer E, Vijayakumar L, Schony W, Grausgruber A, Sonneck G. Attitudes towards suicide among medical students: Comparison between Madras (India) and Vienna (Austria) Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1998;33:104–10. doi: 10.1007/s001270050029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Taylor T, Hawton K, Fortune S, Kapur N. Attitudes towards clinical services among people who self-harm: Systematic review. Br J Psychiatry. 2009;194:104–10. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.107.046425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Srivastava M, Tiwari R. A comparative study of attitude of menal health versus nonmental health professionals toward suicide. Indian J Psychol Med. 2012;34:66–9. doi: 10.4103/0253-7176.96163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]