Abstract

Orbital roof fractures after a blunt injury are an uncommon complication of trauma. Traumatic encephaloceles in the orbital cavity are even rarer, with only 15 cases published till date. Raised intraorbital pressure leading to irreversible damage to the optic nerve can be prevented by early diagnosis and management. Orbital computed tomography (CT) with thin axial and coronal sections is helpful in trauma patients with a concurrent orbital trauma. Decompression of the orbital roof is the key step in surgical treatment and should be performed in every case. Repairing the orbital roof has to be performed to avoid transmission of variation in the intracranial pressure to the orbit. We present a case of traumatic orbital encephalocele who underwent surgical treatment via a frontobasal approach with evacuation of the contused herniated brain and reconstruction of the orbital roof using temporalis fascia which is readily available in contrast to costly materials like titanium mesh, screws, bone powder, fibrin glue, and so on, which are not easily available in every hospital. Rapid resolution of proptosis and visual symptoms along with excellent cosmetic outcome was seen at follow-ups after three and nine months. We emphasize the early diagnosis of this rare condition and also emergency treatment to prevent permanent visual loss as well as to achieve good cosmetic results.

Keywords: Head injury, post-traumatic orbital encephalocele, proptosis

Introduction

Orbital roof fractures secondary to blunt trauma are rarely encountered,[1,2] but the exact incidence of orbital trauma remains unknown. Most of the cases are associated with concomitant head trauma. Traumatic encephaloceles in the orbital cavity are even rarer, with only 15 cases reported till date. The commonest cause is a frontal impact or a lateral blow to the orbital rim. The two common reasons for delayed diagnosis of orbital injuries are that ecchymosis and swollen eyelids commonly follow head trauma and the patient is generally obtunded following head injury. A complete neuro-ophthalmological and a thorough palpation of the orbital rims in all patients with ecchymosis and proptosis are mandatory. Plain X-rays of the skull, orbits, and optic foramina along with computed tomography (CT) scanning in both coronal and axial sections gives adequate information as to the cause of proptosis and helps in selecting the operative technique if required.

Case Report

A 25-year-old man was admitted following a motor vehicle accident. Neurological examination revealed that he was unconscious with a glasgow coma scale (GCS) score of 10 [E2V3M5]. He had bilateral periorbital hematoma more on the right side. Visual acuity and extraocular muscle motility of both eyes could not be evaluated completely due to periorbital hematoma, soft tissue swelling, and reduced level of consciousness of the patient. His pupils were bilaterally equal and reactive. Cranial CT axial sections of the head revealed hematoma in the left frontal lobe causing a midline shift along with a depressed fracture of the left frontozygomatic region and a bilateral transverse fracture of the orbital roof [Figure 1]. He underwent surgical evacuation of left frontal contusions, elevation, and removal of depressed segments of the left frontozygomatic bone. A dural tear was also found at the depressed fracture site and duraplasty was done using a pericranial patch. Postoperatively on day 2, he developed rapid progressive proptosis and severe congestion of conjunctiva [Figure 2] contralateral to the operated site. Fundoscopy was attempted but could not be performed because of periorbital edema. A repeat CT scan of the head was performed in which right frontal contusion had developed with edema [Figure 3]. Orbital CT coronal and axial scan was also performed which revealed the formation of an encephalocele toward the right orbit [Figure 4]. The right globe was displaced laterally, inferiorly, and anteriorly. The optic canal and the optic nerve were intact. The patient underwent right frontal craniotomy wherein the right orbital roof was decompressed, and dural tear and the protruding brain tissue into right orbit were identified (Housepian's approach).[3,4] After excision of the protruding part of the brain microsurgically, the dura was reapproximated with a locked running stitch, and a water-tight closure was achieved. The orbital roof region was covered using temporalis fascia graft. The postoperative period was encouraging, and the right eye proptosis and congestion regressed rapidly [Figure 5a–c]. The patient recovered well and was discharged from the hospital on the 16th post-traumatic day when he was conscious with a GCS score of 15 and had intact vision although with mild limitation of movement in the right eye. At a follow-up after three months, cosmetic and neurological recovery was excellent [Figure 5d]. At the last follow-up after nine months, the patient was in good health with no neurological deficits. The final visual outcome was excellent, and the patient recovered full vision and had complete range of extraocular motions in both eyes.

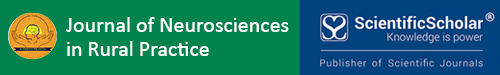

Figure 1.

First preoperative computed tomography scan head showing left frontal lobe contusion (a), bilateral tranverse fracture of the orbital roof (b, arrows), and left frontozygomatic depressed fracture (c)

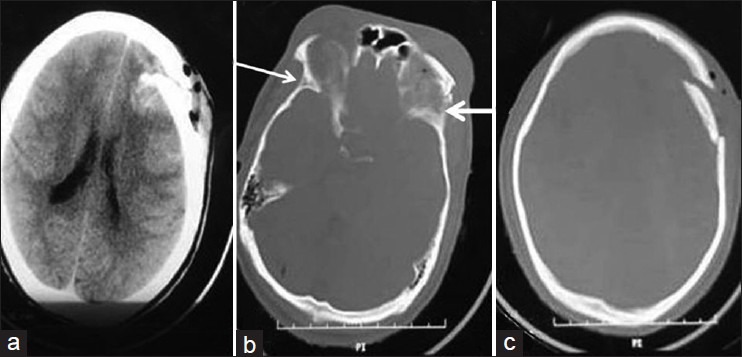

Figure 2.

Rapid progressive proptosis and severe congestion of conjunctiva of right eye

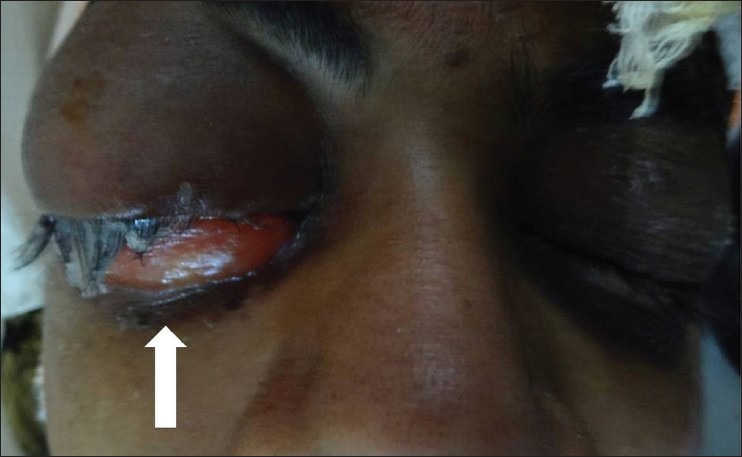

Figure 3.

Computed tomography of the head shows right frontal contusion with edema and postoperative changes in left frontozygomatic region

Figure 4.

Computed tomography of the orbit shows formation of the encephalocele toward the right orbit [white arrow] and displacement of the right eye globe laterally, inferiorly, and anteriorly [black arrow]

Figure 5.

Sequential photographs of patient's eye shows rapid recovery (a) preoperative condition, (b) postoperative day 10, (c) postoperative day 15 and (d) 3 month follow up excellent result

Discussion

Nature has provided orbits as protection for the eyes. The orbital walls along with the eyeball and septum form a closed cavity. Following trauma, there is edema of the retro-ocular tissues resulting in congestion of the veins which in turn further increases the edema. Edema and venous congestion push the eyeball forward, stretching the extraocular muscles and the nerves. This further compresses the draining veins. Beyond a certain limit, the increase in intraorbital pressure gradually occludes the retinal veins, and later the retinal artery, resulting in visual failure. This sequence of events is accelerated if there is a depressed fracture of the orbital wall, roof, and rim, which has further compromised the orbital space. Isolated traumatic orbital fractures can be classified as blow-in or blow-out fractures. The former involves fractures in which the bone fragments are displaced into the orbit, causing an increase in the intraorbital pressure and/or impingement syndromes, which may lead to irreversible neurological injury especially in chronic cases.[5,6] The latter involves the disruption of an orbital wall (usually medial or inferior wall is damaged), and the resultant decompression of the periorbital structures by bony fragments leading to entrapment syndromes.[5,7] Both blow-in and blow-out fractures can be termed as pure if the orbital rim is spared or impure if the orbital rim is fractured. Orbital roof fractures secondary to blunt trauma are rarely encountered.[1,2] Traumatic encephaloceles related to orbital roof fractures are even rarer, with the first case reported in 1951.[1,8] The main symptoms and signs are diplopia, exophthalmos, orbital edema, subconjunctival hemorrhage, restricted movements of the eye, and loss of vision. Patients can present acutely, or the symptoms and signs may gradually appear as the fracture in the orbital wall grows over time. Growing fractures of the orbital roof have been reported several times.[8] In a patient with persistent ocular symptoms and a history of orbital trauma, a growing fracture of the orbital wall must be suspected.[8] Our patient was the victim of an acute traumatic encephalocele related to orbital roof fracture, which is unusual and has been rarely reported. For such cases, early diagnosis and treatment are very important as the raised intraorbital pressure may damage the optic nerve irreversibly. Visual failure, if present, would be either due to direct injury to the eyeball, or vascular injury to the optic nerve. The accepted indications of emergency orbital surgery following orbital trauma are as follows:

Progressive loss of vision: (immediate loss of vision is considered to be due to vascular insufficiency and is not supposed to be benefitted by surgical decompression).

Progressive proptosis: Either due to an expanding intraorbital retro-ocular hematoma or due to progressive swelling of the retro-ocular tissues.

Radiologically demonstrated bony spicule pressing on the optic nerve in the canal.

All the above indications focus on visual failure. However, visual failure is not the only problem in orbital trauma. Acute proptosis also causes stretching of the nerves supplying the extraocular muscles and results in their paresis or palsy. Therefore, relief of the raised intraorbital pressure should also be undertaken on a priority basis. A paralyzed eye with intact vision can be troublesome if not useless. Restriction of extraocular movement due to entrapment of the inferior oblique, inferior rectus, and medial rectus muscles is also possible. Such cases can be dealt with on an elective basis, the treatment of which has been discussed in great detail by Mustarde[9] Reconstruction of orbital roof fracture or defect using titanium mesh, screws, and mixture of bone powder mixed with fibrin glue has been reported, claiming good cosmetic results,[10] but they are not easily or urgently available to poor patients, like in our case. Simple substitutes such as temporalis fascia graft as was used in our case can achieve equally good results.

Conclusions

Whenever orbital roof fractures associated with frontal contusions are identified in an acute brain-injured patient, an orbital encephalocele should be suspected. In our opinion, CT of the orbit is the investigation of choice in such patients. If the encephalocele is confirmed, a surgical approach via the subfrontal route is indicated with resection of herniated contused brain tissue, dural closure, and reconstruction of the orbital roof using temporalis fascia graft. Excellent results with regard to orbital symptoms (mainly exophthalmos) and cosmesis can be expected even without titanium mesh reconstruction if unavailable.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Antonelli V, Cremonini AM, Campobassi A, Pascarella R, Zofrea G, Servadei F. Traumatic encephalocele related to orbital roof fractures: Report of six cases and literature review. Surg Neurol. 2002;57:117–25. doi: 10.1016/s0090-3019(01)00667-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bloem JJ, Meulen JC, Ramselaar JM. Orbital roof fractures. Mod Probl Ophthalmol. 1975;14:510–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Housepian EM. Microsurgical anatomy of the orbital apex and principles of transcranial orbital exploration. Clin Neurosurg. 1978;25:556–73. doi: 10.1093/neurosurgery/25.cn_suppl_1.556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maroon JC, Kennerdel JS. Lateral microsurgical approach to intraorbital tumors. J Neurosurg. 1976;44:556–61. doi: 10.3171/jns.1976.44.5.0556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rothman M. Orbital trauma. Semin Ultrasound CT MR. 1997;18:437–47. doi: 10.1016/s0887-2171(97)90005-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Takizawa H, Sugiura K, Baba M, Tachisawa T, Kadoyama S, Kabayama T, et al. Structural mechanics of the blowout fracture: Numerical computer simulation of orbital deformation by the finite element method. Neurosurgery. 1988;22:1053–5. doi: 10.1227/00006123-198806010-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.King AB. Traumatic encephaloceles of the orbit. AMA Arch Ophthalmol. 1951;46:49–56. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1951.01700020054007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jamjoom ZA. Growing fracture of the orbital roof. Surg Neurol. 1997;48:184–8. doi: 10.1016/s0090-3019(96)00377-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mustarde JC. 2nd ed. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 1980. The orbital walls-Repair and reconstruction of the orbital region-A practical guide; pp. 245–85. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Racaru T, Nguyen-Khac MT, Scholtes F, Dubuisson A, Kaschten B, Martin D. Clinical case of the month. Traumatic bilateral orbital encephalocele. Rev Med Liege. 2010;65:59–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]