Abstract

Hepatic stellate cells (HSCs) are the primary source of matrix components in liver disease such as fibrosis. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) signaling in HSCs has been shown to induce fibrogenesis. In this study, we evaluated the anti-fibrotic activity of a novel imidazopyridine analogue (HS-173) in human HSCs as well as mouse liver fibrosis. HS-173 strongly suppressed the growth and proliferation of HSCs and induced the arrest at the G2/M phase and apoptosis in HSCs. Furthermore, it reduced the expression of extracellular matrix components such as collagen type I, which was confirmed by an in vivo study. We also observed that HS-173 blocked the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway in vitro and in vivo. Taken together, HS-173 suppressed fibrotic responses such as cell proliferation and collagen synthesis by blocking PI3K/Akt signaling. Therefore, we suggest that this compound may be an effective therapeutic agent for ameliorating liver fibrosis through the inhibition of PI3K signaling.

Liver fibrosis is a common consequence of chronic liver injury that is induced by a variety of etiological factors which lead to liver cirrhosis1. This progressive pathological process is characterized by the accumulation of extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins. Liver fibrosis is usually initiated by hepatocyte damage, resulting in the recruitment of inflammatory cells along with activation of Kűpffer cells and activation of hepatic stellate cells (HSCs). In particular, HSCs are recognized as the primary cellular source of matrix components in patients with chronic liver disease, and play a critical role in the development and maintenance of liver fibrosis2,3,4. Activated HSCs with a myofibroblastic phenotype have a high proliferative index, and these cells release profibrogenic cytokines5, and consequently produce ECM-related molecules such as alpha-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA), collagen, and tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases (TIMPs) in cases of liver fibrosis6. Until now, the fibrotic process was considered to be irreversible, but emerging clinical and experimental evidence has revealed that cirrhosis is a potentially reversible condition. The apoptosis of activated HSCs is a key to this reversal7. Although activated HSCs are major cellular targets for preventing the progression of liver fibrosis, there are few therapeutic strategies for treating this disease.

In the liver, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) represents an important signaling molecule that controls many cellular functions including proliferation, survival, adhesion, and migration8. PI3K is composed of an 85-kDa regulatory subunit as well as a 110-kDa catalytic subunit that first activates Akt and subsequently increases the expression of downstream proteins including mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) and P70 S6 kinase (P70S6K)9,10. Activation of the PI3K/Akt pathway has been recently reported to facilitate collagen synthesis in fibroblasts associated with various fibrotic diseases11,12. Additionally, PI3K is activated by the platelet derived growth factor (PDGF) receptor following HSC activation and growth factor stimulation13,14. Activation of Akt is also associated with HSC proliferation and α1 (I) collagen transcription and translation14,15,16. In this regard, PI3K signaling has emerged as important contributor to the fibrotic response.

Inhibition of PI3K signaling in HSCs suppresses extracellular matrix (ECM) deposition, type I collagen synthesis, and reduce the expression of profibrogenic factors14. Furthermore, blocking PI3K activity with LY294002 has been found to inhibit HSC proliferation and collagen gene expression through the interruption of key downstream signaling pathways including ones involving Akt and P70S6K17. Therefore, the interruption of PI3K signaling could inhibit the key components of HSC activation and proliferation, and may represent a target therapy for treating hepatic fibrosis. Based on the involvement of PI3K signaling in liver fibrosis, we previously synthesized ethyl 6-(5-(phenylsulfonamido)pyridin-3-yl)imidazo[1,2-a]pyridine-3-carboxylate (HS-173), a new imidazo [1,2-a]pyridine derivative, as a PI3Kα inhibitor18,19. In the current investigation, we evaluated the anti-fibrotic effect of HS-173 along with the mechanisms underlying these processes in liver fibrosis. Our results demonstrated that HS-173 ameliorates liver fibrosis in vitro and in vivo by promoting HSC apoptosis and inhibiting the expression of fibrotic mediators by blocking the PI3K/Akt pathway in vitro and in vivo.

Results

HS-173 inhibits the proliferation and activation of HSCs

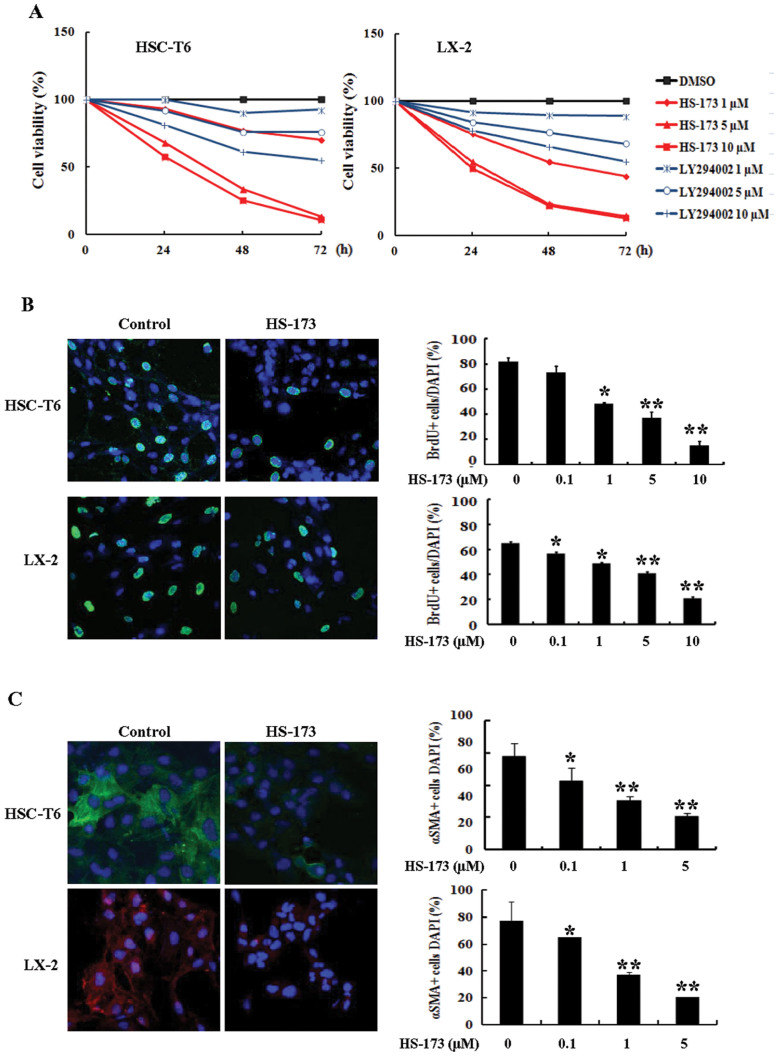

To evaluate the effect of HS-173 on the growth of HSCs, two cell lines (HSC-T6 and LX-2) were exposed to various concentrations of HS-173 and LY294002 (a conventional PI3K inhibitor) for 24, 48, and 72 h. HS-173 treatment reduced cell viability in two hepatic stellate cell lines in a dose and time dependent manner (Figure 1A). When we compared growth rates of the HSCs after treatment with HS173 and LY294002 at three concentrations (1–10 μM), HS-173 treatment caused a greater reduction in the HSC growth rate (80–90% of cell growth inhibition at a concentration of 10 μM) than LY294002 indicating that HS-173 is more effective than LY294002 for attenuating the growth of HSCs. To confirm the effect of HS-173 on HSC proliferation, the level of BrdU incorporation was measured. As shown in Figure 1B, the proliferation of HSCs was significantly inhibited by HS-173 treatment.

Figure 1. Effects of HS-173 on the proliferation of hepatic stellate cells (HSCs).

(A) Cytotoxic effects of HS-173 and LY294002 on HSC-T6 and LX-2 cells were measured using an MTT assay. HSCs were seeded in 48- or 96-well culture plates. After incubating for 1 day, the cells were treated with various concentrations of HS-173 (1–10 μM) or 0.1% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) as a negative control. After incubating for 24, 48, and 72 h, the cells were subjected to the MTT assay. Data are presented as the mean ± S.D. from triplicate wells. Effect of HS-173 on HSC proliferation was measured by (B) BrdU and (C) α-SMA staining, which were photographed at 400 × magnification. The representative image of BrdU-positive cells and α-SMA positive cells were shown with 1 μM HS-173 treatments in HSC-T6 and LX-2 cells. Five independent areas in each slide were imaged and counted in triplicate and expressed as a mean percentage BrdU-positive cells or α-SMA-positive cells/total cells (DAPI). *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01 versus the control.

The activation of HSCs is a central pathophysiological mechanism underlying liver fibrosis, and α-SMA is an established marker of HSCs activation. We therefore determined whether HS-173 inhibited the expression of α-SMA in HSCs. Our findings showed that the expression of α-SMA was much lower in the HSCs by HS-173 treatment (Figure 1C).

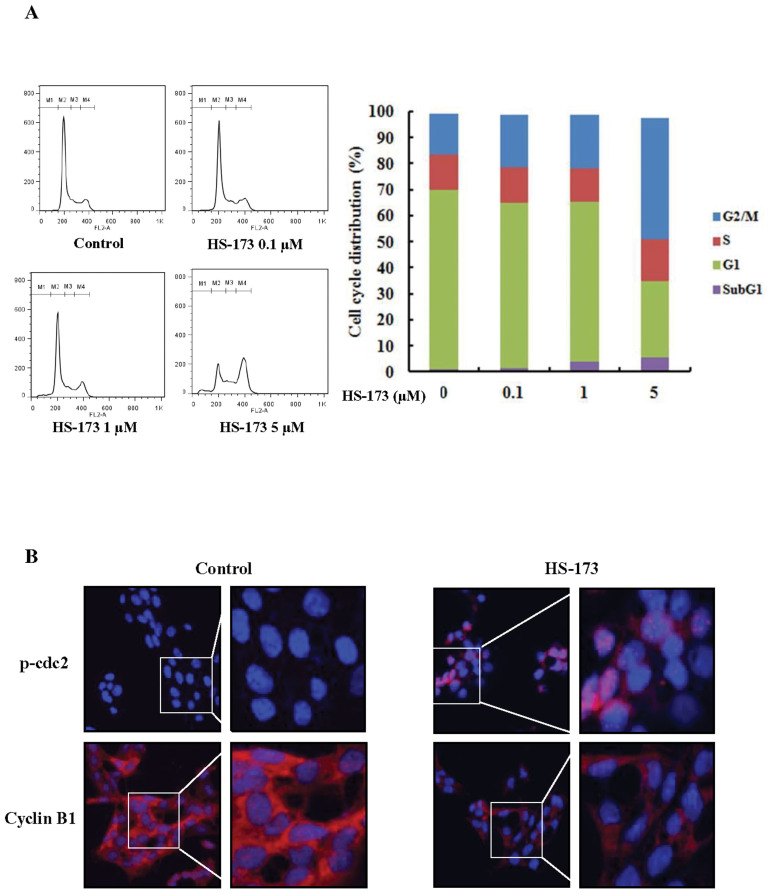

HS-173 induces cell cycle arrest in the G2/M phase

We performed flow cytometry to evaluate the effect of HS-173 on HSCs cycle progression. HSC-T6 cells were incubated with HS-173 for 8 h. Control and treated cells were collected, stained with PI, and then analyzed by FACS. The resulting data demonstrated that treatment with HS-173 induced the accumulation of cells in the G2/M phase (46.3% with 5 μM) accompanied by a decreased number of cells in the G0/G1 phase (Figure 2A). We also measured the expression levels of p-cdc2 and cyclin B1, which typically cause arrest in the G2/M phase of the cell cycle. HSCs were exposed to HS-173 for 8 h and then prepared for evaluation by immunofluorescence. As shown in Figure 2B, treatment with 5 μM of HS-173 decreased the expression of cyclin B1 while increasing that of p-cdc2 in HSCs, compared to the control.

Figure 2. Effect of HS-173 on the HSC cell cycle.

(A) After incubating for 1 day, HSC-T6 cells were treated with various concentrations of HS-173 (0, 0.1, 1, and 5 μM) for 8 h, stained with propidium iodide (PI) and analyzed with a FACSCalibur flow cytometer. M1, sub-G1; M2, G0/G1; M3, S; and M4, G2/M. Quantitation of the PI staining data is presented as the cell cycle distribution percentages. (B) The expression of p-cdc2 and cyclin B1 was evaluated by immunofluorescence in HSC-T6 cells treated with 5 μM of HS-173 for 8 h. 400 × and 800 × magnification.

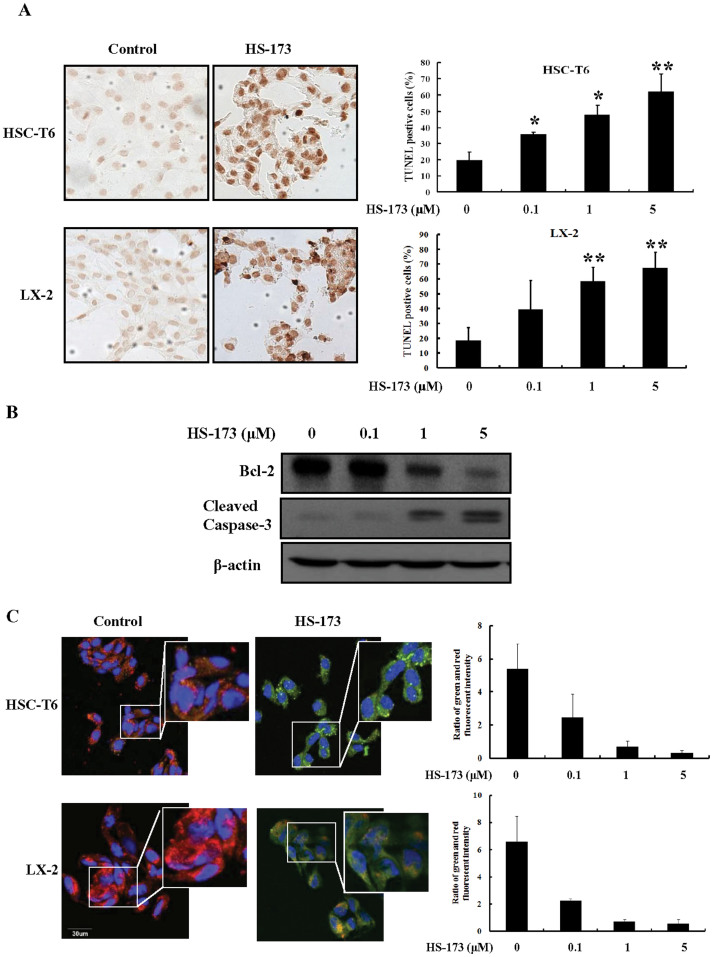

HS-173 induces HSC apoptosis

Induction of apoptosis by HS-173 was evaluated by characterizing nuclear morphology with TUNEL, JC-1 staining, and Western blotting. As shown in Figure 3A, HS-173 increased TUNEL staining in a dose dependent manner in both cell lines. The cells treated with 5 μM of HS-173 presented characteristic morphological features of apoptotic cells such as nuclear condensation and the formation of perinuclear apoptotic bodies. Additionally, HS-173 treatment increased the expression of cleaved caspase-3 and decreased that of Bcl-2 in the HSC-T6 cells (Figure 3B).

Figure 3. Effect of HS-173 on HSC apoptosis.

(A) The induction of apoptosis by HS-173 (0–5 μM) was monitored by TUNEL staining (200 × magnification). The representative image of TUNEL positive cells were shown with 5 μM HS-173 treatments in both HSC-T6 and LX-2 cells (B) The expression of cleaved caspase-3, Bcl-2, and β-action was measured by Western blotting in HSC-T6 cells treated with HS-173 at the indicated doses for 24 h. (C) Ratio of red and green fluorescence intensity from JC-1 staining after the treatment with various HS-173. The representative image was shown with 1 μM HS-173 treatment. Data are presented as the mean ± S.D. of three independent experiments. *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01 versus the control.

To assess the effect of HS-173 on mitochondria potential, we performed JC-1 staining. As shown in Figure 3C, control cells showed heterogeneous staining in the cytoplasm with both red and green fluorescence coexisting in the same cell. Consistent with mitochondrial localization, the red fluorescence was mostly found in granular structures distributed throughout the cytoplasm. Treatment of the HSCs with HS-173 (0.1–5 μM) decreased the red fluorescence and increased clusters of mitochondria. HS-173 induced marked changes in mitochondrial membrane potential ψm as evident from the disappearance of the red fluorescence or increased green fluorescence in most cells. These results indicated that HS-173 promoted apoptosis with the loss of mitochondrial membrane potential ψm and the severity of cell damage in HSCs.

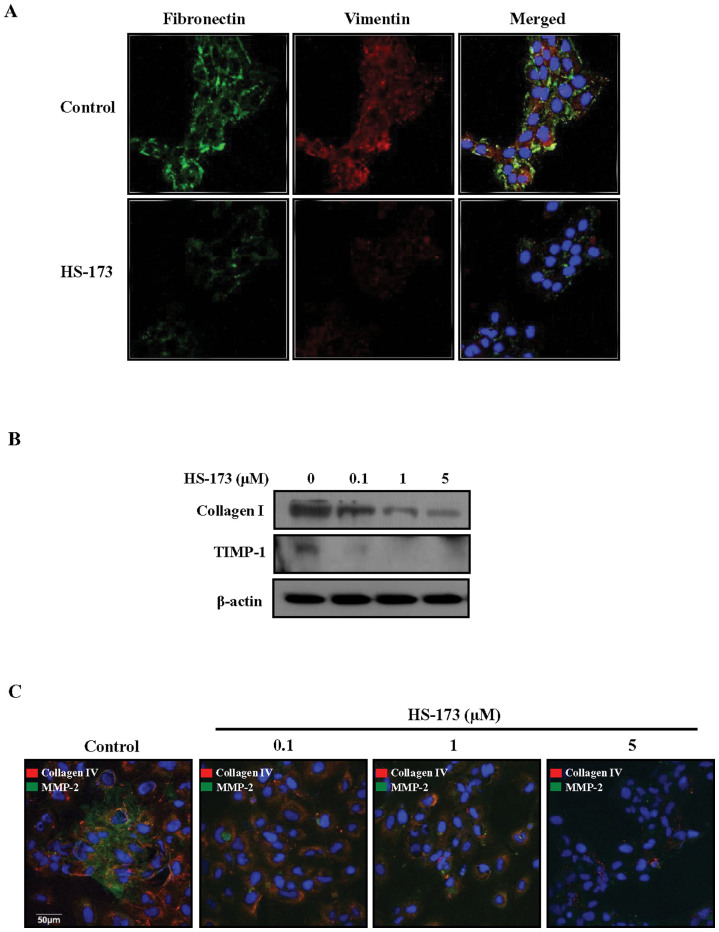

HS-173 inhibits the expression of profibrotic mediators and ECM degradation modulators in HSCs

To assess the impact of HS-173 on HSC activation, the expression of fibronectin and vimentin was measured. As shown in Figure 4A, treatment with 1 μM HS-173 decreased the expression of fibronetin and vimentin compared to the control (Figure 4A). Since activated HSCs are responsible for increased collagen synthesis and deposition in the liver, we also monitored the expression of collagen. Similar to fibronetin and vimentin, HS-173 suppressed collagen I expression in the HSCs. In addition, the increased expression of TIMP-1, which is partially responsible for decreased ECM degradation, was strongly reduced by HS-173 treatment (0.1–5 μM) in the HSCs (Figure 4B). These anti-fibrotic effects of HS-173 were confirmed by observing decreased collagen IV and MMP-2 expression (Figure 4C).

Figure 4. Effect of HS-173 on the expression of fibrogenic proteins in HSCs.

(A) After treatment with 1 μM HS-173 for 4 h, the expression of fibronectin and vimentin was detected by immunofluorescence. DAPI was used to visualize the nucleus. Photographs were taken at 400 × magnification. (B) After treatment with various concentrations of HS-173 (0.1–5 μM) for 24 h, effect of HS-173 on the levels of collagen I and TIMP-1 was determined by Western blotting. (C) Immunofluorescent signals corresponding to the expression of collagen IV and MMP-2 in HSCs treated with HS-173 (0.1–5 μM) for 4 h. An image representative of three independent experiments is shown.

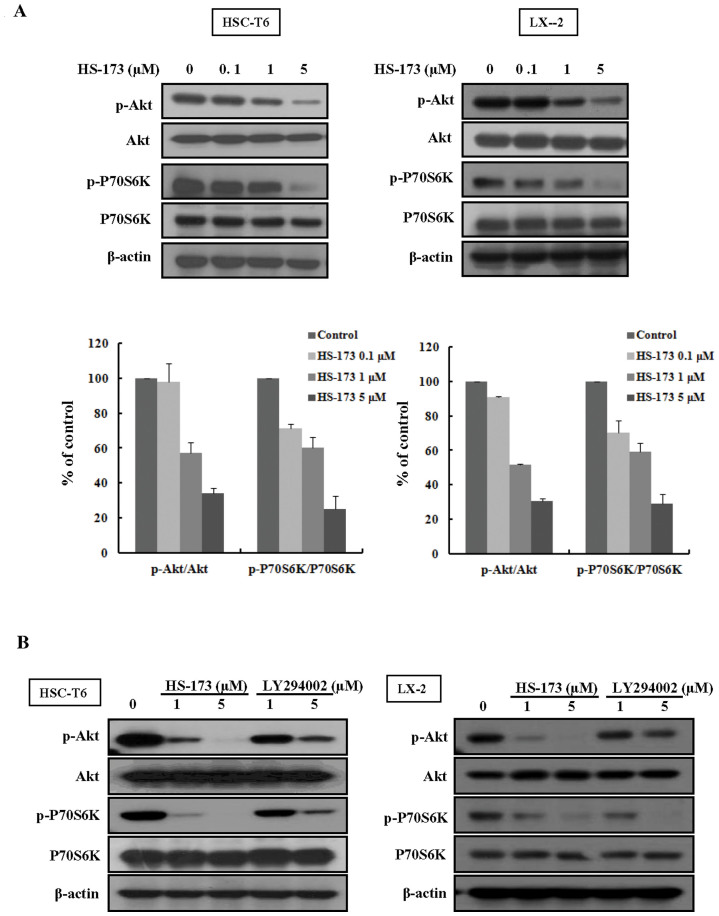

HS-173 blocks PI3K/Akt signaling by decreasing the expression phosphorylation of Akt and P70S6K in HSCs

It has been shown that HSCs growth is closely related to activation of the PI3K/Akt pathway16,22. Deregulation of PI3K/Akt signaling has also been increasingly implicated in the development of liver fibrosis. We therefore investigated the effect of HS-173 on the PI3K/Akt pathway in HSCs. As shown in Figure 5A, we observed that HS-173 effectively suppressed the phosphorylation level of Akt and its downstream factor P70S6K was effectively suppressed in cells treated with various concentrations (0.1–5 μM) of HS-173 for 24 h. More interestingly, HS-173 clearly suppressed the phosphorylation level of Akt and P70S6K to a greater degree than LY294002 (Figure 5B).

Figure 5. Effect of HS-173 on PI3K/AKT signaling in HSC cells.

(A) Cells were treated with various concentrations (0.1–5 μM) of HS-173 for 24 h. Western blotting for p-Akt and p-P70S6K was performed with cell lysates obtained after HS-173 treatment. (B) Following treatment with HS-173 or LY294002 (1 and 5 μM) for 6 h, p-Akt and p-P70S6K levels were measured by Western blotting. Data are expressed as the mean ± S.D. from three independent experiments.

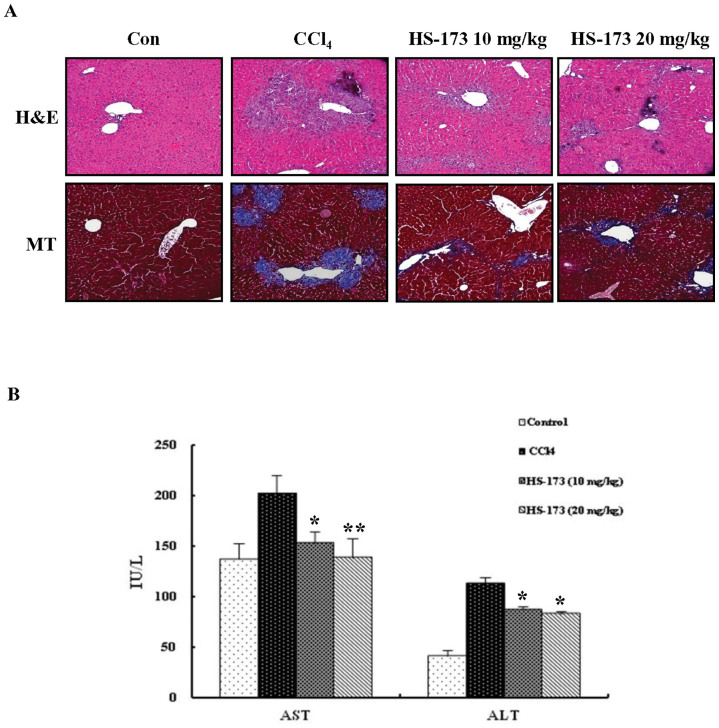

HS-173 improves CCl4-induced liver fibrosis in mice animal model

Liver fibrosis induced by CCl4 treatment in mice was evaluated by H&E and MT staining. The results from these two procedures showed similar staining pattern. Livers from the control group showed normal architecture whereas samples from the CCl4-treated group exhibited extensive and severe hemorrhagic necrosis, disruption of tissue architecture, and inflammatory cell infiltration. Treatment with both concentrations of HS-173 (10 mg/kg and 20 mg/kg) reduced fibrosis as demonstrated by MT staining for collagen (Figure 6A). In particular, the 20 mg/kg-treated group showed a remarkable reduction of the fibrotic area. CCl4 injection to mice increased the levels of AST and ALT (indicative of liver damage) in the mice. The subsequent administration of HS-173 significantly lowered the levels of these two factors (Figure 6B).

Figure 6. Effect of HS-173 on CCl4-induced liver fibrosis in mice.

(A) Liver fibrosis was assessed by H&E and MT staining. 200 × original magnification. (B) Effects of HS-173 on serum parameters that affect liver function in mice treated with CCl4 for 4 weeks. Data are expressed as the mean ± S.D. (n = 8). *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01 versus the CCl4-treated group.

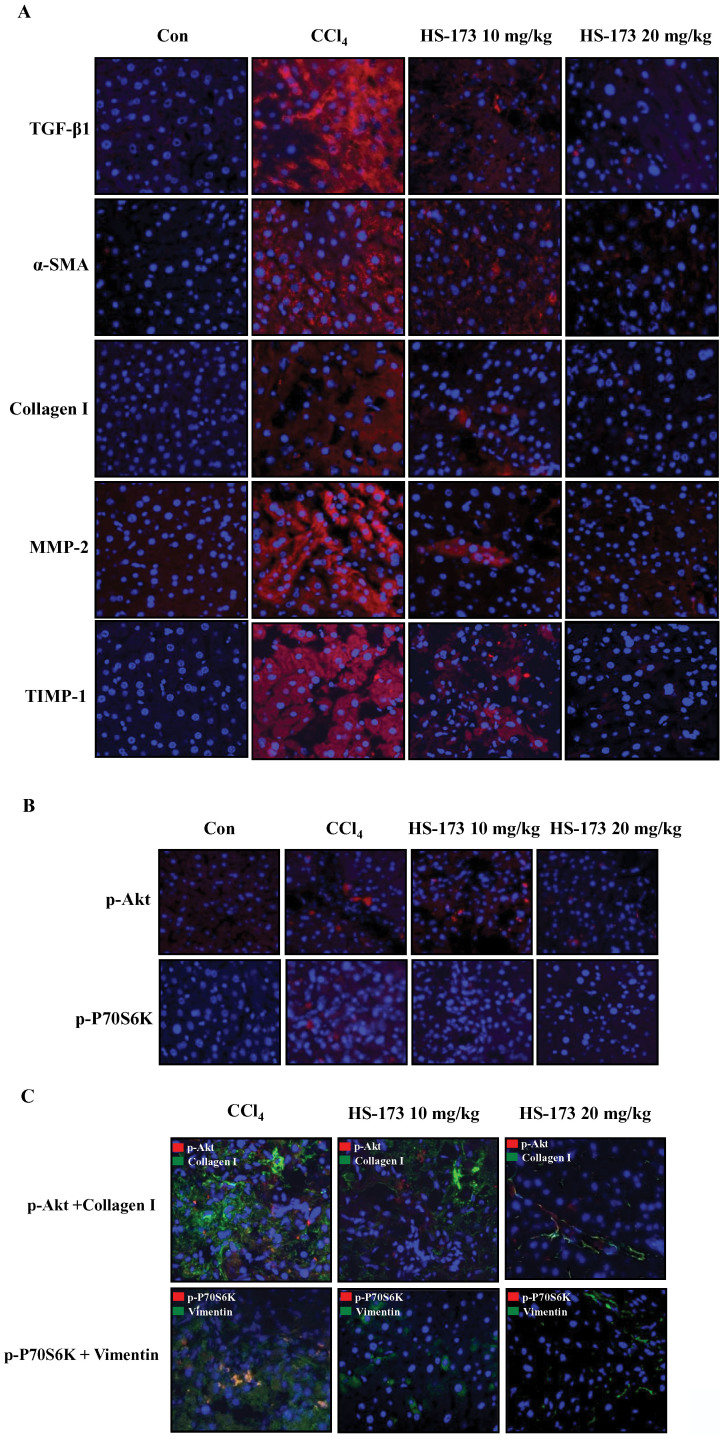

HS-173 inhibits ECM accumulation and PI3K/Akt signaling in mice with CCl4-induced liver fibrosis animal model

We next determined whether HS-173 influence the expression of profibrotic mediators such as α-SMA and collagen I in mice with CCl4-induced liver fibrosis. The expression levels of α-SMA and collagen I were increased in the CCl4-induced liver fibrosis group, and significantly decreased in the mice treated with both concentrations (10 and 20 mg/kg) of HS-173. High levels of α-SMA and collagen I expression were detected in the periportal fibrotic areas, central veins, portal tracts, and fibrous septa in the CCl4-induced liver fibrosis group. These factors were weakly expressed in the two HS-173 treated groups. MMP-2 expression can be important for mediating HSCs proliferation, potentially by regulating ECM turnover, and is a major cause of liver fibrosis. Activated HSCs also produce TIMPs. In particular, TIMP-1 expression increases soon after liver injury and persists during fibrosis development. Our results showed that HS-173 decreased the expression of both MMP-2 and TIMP-1 (Figure 7A).

Figure 7. Effect of HS-173 on ECM accumulation and PI3K/Akt signaling in mice with CCl4-induced liver fibrosis.

(A) Expression of TGF-β1, α-SMA, collagen I, MMP-2, and TIMP-1 was evaluated by immunostaining in liver tissues extracted from mice treated with CCl4 and HS-173 for 4 weeks. (B) Expression of p-Akt and p-P70S6K in liver tissues extracted from mice treated with CCl4 and HS-173. (C) Immunofluorescence staining to evaluate the effect of HS-173 on the expression of p-Akt, collagen I, p-P70S6K, and vimentin in liver tissues. 400 × original magnification.

To further assess whether HS-173 blocks the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway in vivo, we monitored the expression of p-Akt and p-P70S6K that helps regulate many different events governing HSCs proliferation and liver fibrosis development in the liver tissues. Based on the histopathological analysis using immunofluorescence staining, we determined that HS-173 clearly suppressed the expression of p-Akt and p-P70S6K along with decreasing expression of collagen I and vimentin in the mice with CCl4-induced liver fibrosis (Figure 7B and 7C). Taken together, our results demonstrated that HS-173 exerts potent effects against CCl4-induced liver fibrosis models.

Discussion

Liver fibrosis is a common consequence of chronic liver injury leading to liver cirrhosis1. Activation of HSCs is an important component of this process23. The PI3K signaling pathway has been shown to regulate procedures associated with HSCs activation such as collagen synthesis and cell proliferation. Recently, the importance of PI3K signaling in the progression of hepatic fibrogenesis during HSC activation and profibrogenic mediator production has been reported24. In this regard, PI3K signaling in HSCs is considered to be an effective therapeutic target for treating hepatic fibrosis. We previously synthesized HS-173, a novel PI3K inhibitor19. In the present study, we evaluated the anti-fibrosis effects of this compound along with the underlying mechanisms in vitro and in vivo. Our results showed that HS-173 inhibited PI3K/Akt signaling and exerted anti-fibrotic effects by decreasing the expression of collagen, α-SMA, and vimentin in both HSCs and mice with CCl4-induced liver fibrosis. HS-173 also inhibited HSC growth and proliferations. Our findings revealed that inhibition of the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway is responsible for the anti-fibrotic effects of HS-173 in the liver fibrosis.

We conducted an investigation to determine whether HS-173 inhibits cell growth/proliferation and evaluate the anti-fibrotic effect of this compound in activated HSCs, which are major targets for anti-fibrotic therapies because these are regarded as the major fibrogenic cell type in the injured liver14. In present study, we first discovered that HS-173 significantly inhibited HSCs viability and proliferation in dose- and time-dependent manner. Interestingly, HS-173 had greater efficacy than LY294002, a traditional PI3K inhibitor, in the HSCs. These data showed that the inhibition of PI3K/Akt signaling significantly impacted the growth/proliferation of HSCs and HS-173 obviously inhibited this process25,26.

This reduction in cell growth/proliferation was associated with a profound modulation of cell cycle arrest27. The PI3K pathway plays a key role in the G2/M transition and Akt functions as a G2/M initiator28. We consequently expected that HS-173 would induce cell arrest in the G2/M phase. Interestingly, our findings indicated that HS-173 induced a clear arrest of cells by the accumulation of cells in the G2/M phase, which indicated late entry into mitosis leading to delayed cell division. During the G2/M phase, cyclin B/cdc2 is inactivated by phosphorylation on two regulatory residues (Thr14/Tyr15)29. Dephosphorylation of these two residues by cdc25c during the late G2 phase activates the cyclin B/cdc2 complex, triggering the initiation of mitosis. We found that HS-173 resulted in upregulation of p-cdc2 production and downregulation of cyclin B1 expression, indicating that mitosis was arrested. Although many factors and pathways including the PI3K/Akt pathway are involved in cell cycle regulation, our results demonstrated that HS-173 inhibited cell growth/proliferation by inducing cell cycle arrest associated with the accumulation of cells in the G2/M state, which may have been partly regulated by p-cdc2 and cyclin B1.

Apoptosis has emerged as an important mechanism for reducing the number of activated HSCs during the resolution phase of liver fibrosis. We determined that HS-173 significantly induced the apoptosis of HSCs, which correlated with increased numbers of TUNEL-positive cells. HS-173 also increased the expression of cleaved caspase-3 and decreased that of Bcl-2. Overexpression of Bcl-2 in activated HSCs has been reported to enhance the resistance to apoptosis30. Accordingly, reduced Bcl-2 expression following HS-173 treatment may help inhibit the development of fibrosis.

Mitochondria represent a central checkpoint of apoptosis control by integrating various signals31. Bcl-2 is also essential for targeting the mitochondrial outer membrane32. In addition, inhibition of PI3K/Akt has been reported to follow the induction of the downstream mitochondrial apoptotic pathway through alterations in the ratio of Bcl-2/Bax and activation of caspase-333,34. Based on the facts that mitochondria play a role in apoptosis through the PI3K/Akt pathway and our finding that HS-173 decreased Bcl-2 expression and increased cleaved caspase-3 levels, we speculated that HS-173 could change the mitochondria potential in activated HSCs. To assess the effect of HS-173 on mitochondrial membrane potential, we conducted JC-1 immunofluorescence staining. As expected, HS-173 induced marked changes in mitochondrial membrane potential in the HSCs. Overall, our study showed that HS-173 induced mitochondria-mediated apoptosis in HSCs, and simultaneous targeting of the PI3K/Akt pathway can provide further promote apoptosis.

Considering the results from our investigation, the effect of HS-173 on HSCs proliferation and apoptosis was expected to influence anti-fibrotic responses in HSCs and mice with CCl4-induced liver fibrosis. In addition, several studies have reported that the fibroblasts including HSCs secrete ECM-related proteins, and in turn the ECM itself regulates cell proliferation, apoptosis, and migration35,36. We therefore determined whether HS-173 inhibited the expression of profibrotic factors such as α-SMA, vimentin, fibronectin, collagen I/IV, MMP-2, TIMP-1, and TGF-β. HS-173 reduced the expression of these mediators in both the HSCs and mice with liver fibrosis. Our data also revealed that HS-173 inhibited the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway by decreasing the expression of Akt and P70S6K in both HSCs and CCl4-treated mice. More importantly, HS-173 was able to inhibit PI3K/Akt signaling and HSCs proliferation to a greater degree than LY294002, a PI3K/Akt-specific inhibitor. These results were consistent with those of Son et al. showing that inhibition of PI3K signaling in activated HSCs and fibrosis models inhibits the expression of collagen and profibrogenic factors24. Furthermore, the PI3K/Akt pathway has been reported to represent a mechanism critical for the proliferation of fibroblasts in various organs including the lung and liver11,24. PI3K activation has recently been reported to promote DNA synthesis and migration of stellate cells37. In addition, PI3K-induced Akt activation has been shown to significantly induce the proliferation and survival of HSCs, likely involving P70S6K activation14. Given the correlation between PI3K/Akt signaling and fibrosis, our results imply that the anti-fibrotic effect of HS-173 was mediated by inhibition of the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway.

In conclusion, data from the current study demonstrated that HS-173 markedly attenuated the development of liver fibrosis by blocking PI3K/Akt signaling both in vitro and in vivo. Furthermore, this inhibition appears to be critical for the induction of HSC apoptosis and inhibition of proliferation, thereby eliminating important collagen-producing cells from the liver. Findings from our investigation suggest that HS-173 may be potentially useful for treating liver fibrosis by targeting the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway.

Methods

Preparation of HS-173

Ethyl 6-(5-(phenylsulfonamido)pyridin-3-yl)imidazo[1,2-a]pyridine -3-carboxylate (HS-173) is a new novel PI3Kα inhibitor. This imidazopyridine derivative was synthesized as described in our previous study16. For all in vitro studies, HS-173 was dissolved in dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) before use.

Cell culture

HSC-T6 and LX-2 cells were a gift from Professor S. L. Friedman (Liver Disease Research Center of San Francisco General Hospital, CA, USA). Both cell types were routinely cultured in Dulbeco's Modified Eagle's Medium (DMEM; Gibco, Carlsbad, USA) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. The FBS and all other reagents used for the cell culture studies were purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA, USA). The cultures were maintained at 37°C in a CO2 incubator with a controlled humidified atmosphere composed of 95% air and 5% CO2.

Measurement of cell proliferation

Cell viability was performed using an MTT assay. Briefly, HSC-T6 cells were plated at a density of 3–10 × 103 cells/well in 96-well plates and then incubated for 24 h. The LX-2 cells were plated at density of 2–3 × 104 cells/well in 48-well plates and then incubated for 24 h. Next, the media were removed and the cells were treated with either DMSO, at a final concentration of ≤ 0.1% (v/v) as a negative control, or various concentrations (1–10 μM) of HS-173 and LY294002. The final concentration of DMSO in the media was ≤ 0.1% (v/v). After the cells were incubated for 24, 48, or 72 h, 10% of an MTT solution (2 mg/mL) was added to each well and the cells were incubated for another 4 h at 37°C. The formazan crystals that formed were dissolved in DMSO (100 or 300 μL/well) with constant shaking for 5 min. Absorbance of the plate was then read with a microplate reader at 540 nm. Three replicate wells were evaluated for each analysis. The median inhibitory concentration (IC50) defined as the drug concentration at which cell growth was inhibited by 50% was calculated using the resulting dose-response curves.

Immunodetection of 5'-bromo-2'- deoxyuridine (BrdU) incorporation

HSC-T6 and LX-2 cells were plated on 18-mm cover glasses in DMEM and grown to approximately 70% confluence for 24 h. The cells were then pre-treated with or without HS-173 (0.1–10 μM) for 2 h, then incubated for an additional 2 h in medium containing 10 μM BrdU. The cells were washed twice with PBS and fixed in an acetic acid:ethanol (2:1) solution for 10 min at −20°C. Following fixation, the cells were washed with 1% Triton X-100 in PBS (pH 7.4). Next, the BrdU-labeled cells were incubated in 4 N HCl for 30 min on ice to disrupt the DNA structure in the BrdU labeled cells. After denaturation, borate buffer (0.1 M) was added for neutralization. Non-specific binding in the cells was blocked with 1.5% horse serum in PBS for 30 min at room temperature, and the cells were then incubated with an anti-BrdU antibody (Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA) in a humidified chamber. After washing twice with PBS, the cells were incubated with an anti-mouse fluorescein-labeled secondary antibody (diluted 1:30 in 1.5% horse serum/PBS) at room temperature in the dark for 1 h. 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) was used to stain the nucleus. The slides were washed twice with PBS and covered with DABCO (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) before confocal laser scanning microscopy was performed. Five independent areas in each slide were imaged and counted in triplicate and expressed as a mean percentage BrdU-positive cells/total cells (DAPI).

Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP mediated nick end labeling (TUNEL) assay

HSC-T6 and LX-2 cells were plated on 18-mm cover glasses in DMEM and grown to ~70% confluence for over 24 h. The cells were then treated with HS-173 (0.1–5 μM) for 4 h, fixed in ice-cold 1% paraformaldehyde, and washed with PBS. The stained cells were examined for a fluorescence of nuclear fragmentation. Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase–mediated nick end labeling (A TUNEL assay) was subsequently performed using a commercial kit (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA).

Measurement of mitochondrial permeability potential

HSC-T6 and LX-2 cells were plated on 18-mm cover glasses in DMEM and grown to ~70% confluence for 24 h. And then the cells were treated with various concentrations of HS-173 (0.1–5 μM) for 4 h. For staining the mitochondrial membrane potential (ψm), cells were incubated with the cationic dye JC-1 for 20 min (JC-1 Mitochondrial Membrane Potential Assay Kit; Cayman Chemical Company, Ann Arbor, MI, USA) that accumulates in mitochondria in a potential-dependent manner. At a low mitochondrial membrane potential (ψm), JC-1 continues to exists as a monomer and produces green fluorescence (emission at 527 nm). At a high mitochondrial membrane potentials or concentrations, JC-1 forms J aggregates (emission at 590 nm) that emit red fluorescence.

Western blotting

HSC-T6 and LX-2 cells were washed three times with ice-cold PBS before being lysed in a buffer containing 1% Triton X-100, 1% Nonidet P-40, and the following protease and phosphatase inhibitors: aprotinin (10 mg/mL), leupeptin (10 mg/mL; ICN Biomedicals, Asse-Relegem, Belgium), phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (1.72 mM), NaF (100 mM), NaVO3 (500 mM), and Na4P2O7 (500 mg/mL; Sigma–Aldrich). Equal amounts of protein were separated using 8 or 12% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes. Protein transfer was confirmed using a Ponceau S staining solution (Sigma–Aldrich). The blots were then immunostained with the appropriate primary antibodies followed by secondary antibodies conjugated to horseradish peroxidase. Primary antibodies specific for the following factors were used: Bcl-2 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA), Cleaved caspase-3, p-Akt, Akt, p-P70S6K, P70S6K (Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA, USA), collagen I, TIMP-1, and β-actin (Abcam, Cambridge, UK). All secondary antibodies were purchased from Amersham Biosciences. Bands on the blots were visualized with an enhanced chemiluminescence system (Amersham Biosciences) and intensities were quantified with Image-J software.

Immunofluorescence microscopy

HSC-T6 and LX-2 cells were plated on 18-mm cover glasses in DMEM at a density of 1–1.5 × 105 cells/well and incubated for 24 h. Next, the cells were incubated in the presence or absence of HS-173 (0.1–5 μM) for 4 h or 8 h. The cells were then washed with PBS and fixed in an acetic acid:ethanol (2:1) solution for 5 min at −20°C. Nonspecific binding was blocked with 5% goat and horse serum/PBS for 1 h at room temperature, and the cells were then incubated with primary antibodies against α-SMA, vimentin (Sigma-Aldrich), p-cdc2 (Cell Signaling Technology), cyclin B1, matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-2 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), or fibronectin (Abcam) in a humidified chamber. After washing twice in PBS, the cells were incubated with fluorescein-labeled secondary antibody (1:50 dilution; Dianova) in antibody dilution solution for 1 h at room temperature in the dark. The nuclei were stained with 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) in the dark for 30 min at room temperature. The slides were washed twice with PBS, covered with DABCO (Sigma-Aldrich), and examined with confocal laser scanning microscopy (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) at 488 and 568 nm.

Cell cycle analysis

HSC-T6 cells were plated in 100 mm dishes with medium containing 10% FBS. The next day, cells were treated with various concentrations of HS-173 (0.1–5 μM)for 8 h. The cells were then collected and fixed overnight in cold 70% ethanol at 4°C. After washing, the cells were subsequently treated with 50 μg/mL propidium iodide (PI) and 100 μg/mL RNase A for 30 min in the dark, and subjected to flow cytometric analysis in order to determine the percentage of cells in specific phases of the cell cycle (subG1, G0/G1, S, and G2/M). Flow cytometry was performed using a FACScalibur flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) equipped with a 488-nm argon laser.

Animals

Male BALB/c mice (6 week old, weighing 22–26 g) were obtained from Orient Bio. Animal Inc. (Seoul, Republic of Korea). Animal care and all experimental procedures were conducted in accordance with the approval and guidelines of the INHA Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (INHA IACUC) of the Medical School of Inha University (approval ID: 111024-1). The animals were fed standard rat chow and tap water ad libitum, and were maintained with a 12 h dark/light cycle at 21°C. Male mice were randomly divided into a 4 groups of 8 each: control, CCl4-treated, and two HS-173-treated (10 or 20 mg/kg) groups with eight animals each.

Acute liver damage was induced by intraperitoneal injection of 40% CCl4 with corn oil at a single dose of (150 μL) delivered twice a week for one month. Control animals were treated with the same volume of corn oil alone was used as control. The two HS-173 groups were treated with oral administration doses (10 or 20 mg/kg) of the compound on 6 days a week for one month during CCl4 administration. The HS-173 was dissolved in DMSO, and then mixture (DMSO:PEG400:D.W. = 1:5:4) was treated. All the mice were sacrificed by ether anesthesia after 4 weeks of treatment. The livers were excised and weighed. The liver specimens were immediately fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin for histochemical studies. Blood samples for biochemical analyses were obtained from the heart.

Evaluation of liver histopathology

Liver samples fixed in a 10% buffered formaldehyde solution were processed using a paraffin slice technique. Sections about 4 μm thick were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) for routine histological examination. The sections were first stained with hematoxylin for 3 min, washed, and then stained with 0.5% eosin for an additional 3 min. After an additional wash with water, the slides were dehydrated in 70, 95, and 100% ethanol, and cleared in xylene. The degree of liver damage was examined blindly by a special pathologist using a light microscope (Olympus).

Assessment of biochemical parameters

Serum aspartate transaminase (AST) and alanine transaminase (ALT) levels were measured at the Green Cross Reference Lab (Seoul, Republic of Korea).

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemical staining was performed using formalin-fixed and deparaffinized tissue sections as previously described20,21. Primary antibodies used were specific for TGF-β, collagen I, TIMP-1 (Sigma-Aldrich), α-SMA, vimentin (Sigma-Aldrich), MMP-2 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), p-Akt, and p-P70S6K (Cell Signaling Technology). After washing off unbound primary antibody, the sections were incubated with fluorescein-labeled secondary antibody in 1.5% horse serum/PBS at room temperature in the dark for 20 min at 37°C. DAPI was used to stain the nucleus. The slides were washed twice with PBS, covered with DABCO (Sigma-Aldrich), and examined with confocal laser scanning microscopy.

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as the mean ± S.D., and analyzed with an ANOVA and unpaired Student′s t-test. A P-value of 0.05 or less was considered statistically significant. Statistical calculations were performed using SPSS software for the Windows operating system (version 10.0; SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA).

Author Contributions

Son M.K. and Jung K.Y. wrote the main manuscript text, and Ryu Y.L., Lee H., Lee H.S. and Yan H.H. prepared Fig. 1-4, and Park H.J., Ryu J.K., Suh J.K., Hong S. and Hong S.S. planned main strategy.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a grant (A110076) from the Korea Health Technology R&D Project, Ministry of Health and Welfare, Republic of Korea awarded to Dr. Jun-Kyu Suh.

References

- Friedman S. L. Mechanisms of hepatic fibrogenesis. Gastroenterology. 134, 1655–1669 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mormone E., George J. & Nieto N. Molecular pathogenesis of hepatic fibrosis and current therapeutic approaches. Chem Biol Interact. 193, 225–231 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen-Naftaly M. & Friedman S. L. Current status of novel antifibrotic therapies in patients with chronic liver disease. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 4, 391–417 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reeves H. L. & Friedman S. L. Activation of hepatic stellate cells--a key issue in liver fibrosis. Front Biosci. 7, d808–826 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maher J. J. Interactions between hepatic stellate cells and the immune system. Semin Liver Dis. 21, 417–426 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iredale J. P. et al. Tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-1 messenger RNA expression is enhanced relative to interstitial collagenase messenger RNA in experimental liver injury and fibrosis. Hepatology. 24, 176–184 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsukamoto H. et al. Anti-adipogenic regulation underlies hepatic stellate cell transdifferentiation. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 21, S102–105 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai T. et al. Thymoquinone attenuates liver fibrosis via PI3K and TLR4 signaling pathways in activated hepatic stellate cells. Int Immunopharmacol. 15, 275–281 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantley L. C. The phosphoinositide 3-kinase pathway. Science. 296, 1655–1657 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andre E. et al. Expression and functional pharmacology of the bradykinin B1 receptor in the normal and inflamed human gallbladder. Gut. 57, 628–633 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Z. et al. Lipopolysaccharide induces lung fibroblast proliferation through Toll-like receptor 4 signaling and the phosphoinositide3-kinase-Akt pathway. PLoS One. 7, e35926 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li N. et al. Suppression of type I collagen expression by miR-29b via PI3K, Akt, and Sp1 pathway in human Tenon's fibroblasts. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 53, 1670–1678 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miao B. & Degterev A. Targeting phospshatidylinositol 3-kinase signaling with novel phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-triphosphate antagonists. Autophagy. 7, 650–651 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reif S. et al. The role of focal adhesion kinase-phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-akt signaling in hepatic stellate cell proliferation and type I collagen expression. J Biol Chem. 278, 8083–8090 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welsh P. & Repetto R. Revascularization of the profunda femoris artery in aortoiliac occlusive disease. Surgery. 78, 389–393 (1975). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulik G., Klippel A. & Weber M. J. Antiapoptotic signalling by the insulin-like growth factor I receptor, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase, and Akt. Mol Cell Biol. 17, 1595–1606 (1997). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gentilini A., Marra F., Gentilini P. & Pinzani M. Phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase and extracellular signal-regulated kinase mediate the chemotactic and mitogenic effects of insulin-like growth factor-I in human hepatic stellate cells. J Hepatol. 32, 227–234 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yun S. M. et al. Synergistic anticancer activity of HS-173, a novel PI3K inhibitor in combination with Sorafenib against pancreatic cancer cells. Cancer Lett. 331, 250–261 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H. et al. HS-173, a novel phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) inhibitor, has anti-tumor activity through promoting apoptosis and inhibiting angiogenesis. Cancer Lett. 328, 152–159 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikejima K. et al. Leptin receptor-mediated signaling regulates hepatic fibrogenesis and remodeling of extracellular matrix in the rat. Gastroenterology. 122, 1399–1410 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J. H. et al. The use of low molecular weight heparin-pluronic nanogels to impede liver fibrosis by inhibition the TGF-beta/Smad signaling pathway. Biomaterials. 32, 1438–1445 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coffer P. J., Jin J. & Woodgett J. R. Protein kinase B (c-Akt): a multifunctional mediator of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase activation. Biochem J. 335, 1–13 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman S. L. Molecular regulation of hepatic fibrosis, an integrated cellular response to tissue injury. J Biol Chem. 275, 2247–2250 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Son G. et al. Inhibition of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase signaling in hepatic stellate cells blocks the progression of hepatic fibrosis. Hepatology. 50, 1512–1523 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonnet J., Mayonove P. & Morris M. C. Differential phosphorylation of Cdc25C phosphatase in mitosis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 370, 483–488 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinhardt H. C. & Yaffe M. B. Kinases that control the cell cycle in response to DNA damage: Chk1, Chk2, and MK2. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 21, 245–255 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pietenpol J. A. & Stewart Z. A. Cell cycle checkpoint signaling: cell cycle arrest versus apoptosis. Toxicology. 181–182, 475–481 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirose Y. et al. Akt activation suppresses Chk2-mediated, methylating agent-induced G2 arrest and protects from temozolomide-induced mitotic catastrophe and cellular senescence. Cancer Res. 65, 4861–4869 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nebreda A. R. & Ferby I. Regulation of the meiotic cell cycle in oocytes. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 12, 666–675 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novo E. et al. Overexpression of Bcl-2 by activated human hepatic stellate cells: resistance to apoptosis as a mechanism of progressive hepatic fibrogenesis in humans. Gut. 55, 1174–1182 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green D. R. & Kroemer G. The pathophysiology of mitochondrial cell death. Science. 305, 626–629 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen M. et al. Targeting of Bcl-2 to the mitochondrial outer membrane by a COOH-terminal signal anchor sequence. J Biol Chem. 268, 25265–25268 (1993). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zha J. et al. Serine phosphorylation of death agonist BAD in response to survival factor results in binding to 14-3-3 not BCL-X(L). Cell. 87, 619–628 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanahan D. & Weinberg R. A. The hallmarks of cancer. Cell. 100, 57–70 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y. et al. New insights into the antifibrotic effects of sorafenib on hepatic stellate cells and liver fibrosis. J Hepatol. 53, 132–144 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conte E. et al. Inhibition of PI3K prevents the proliferation and differentiation of human lung fibroblasts into myofibroblasts: the role of class I P110 isoforms. PLoS One. 6, e24663 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marra F. et al. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase is required for platelet-derived growth factor's actions on hepatic stellate cells. Gastroenterology. 112, 1297–1306 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]