Summary

The transcription factor Mef2 regulates activity-dependent neuronal plasticity and morphology in mammals, and clock neurons are reported to experience activity-dependent circadian remodeling in Drosophila. We show here that Mef2 is required for this daily fasciculation-defasciculation cycle. Moreover, the master circadian transcription complex CLK/CYC directly regulates Mef2 transcription. ChIP-Chip analysis identified numerous Mef2 target genes implicated in neuronal plasticity, including the cell-adhesion gene Fas2. Genetic epistasis experiments support this transcriptional regulatory hierarchy, CLK/CYC->Mef2-> Fas2, indicate that it influences the circadian fasciculation cycle within pacemaker neurons and suggest that this cycle also contributes to circadian behavior. Mef2 therefore transmits clock information to machinery involved in neuronal remodeling, which contributes to locomotor activity rhythms.

Introduction

Circadian clocks are endogenous, self-sustained oscillators, which enable organisms to synchronize their molecular, cellular and behavioral processes to daily environmental changes. The core timekeeping mechanism operates within individual cells and is comprised of multiple, interlocked transcriptional/translational feedback loops. In D. melanogaster, the positive limb of the principal loop is composed of a heterodimeric complex of the two transcription factors CLOCK (CLK) and CYCLE (CYC), which rhythmically activate expression of their own repressor genes, timeless (tim) and period (per). The negative limb is composed of the period and timeless proteins, PER and TIM, respectively. They dimerize and cyclically inhibit their own transcription via inactivation of the CLK/CYC complex; see (Nitabach and Taghert, 2008) for a review. This core circadian clock also governs the rhythmic expression and/or activity of many other genes, which ultimately result in behavioral, biochemical and physiological rhythms. A very similar model, with many orthologous genes and proteins, describes the mammalian core clock.

The Drosophila clock functions within many cells and tissues. There are approximately 75 circadian neurons per hemisphere in the adult CNS, including 9-10 pairs of ventral lateral neurons (LNvs). They express clock proteins as well as the neuropeptide pigment-dispersing factor (PDF). The four pairs of small ventral lateral neurons, s-LNvs, are important for maintaining clock neuron synchrony and for behavioral rhythms in constant darkness as well as morning locomotor activity (Lin et al., 2004; Yoshii et al., 2009). These neurons have long axonal projections, which were reported to undergo daily changes in morphology (Fernandez et al., 2008). These rhythmic changes are also activity-dependent (Depetris-Chauvin et al., 2011) and may be related to activity-dependent neuronal changes extensively investigated in vertebrate as well as invertebrate model systems (Bushey and Cirelli, 2011; Greer and Greenberg, 2008; Tavosanis, 2011; West and Greenberg, 2011).

There are several other well-studied examples of clock-controlled changes in neuronal morphology. Vertebrate photoreceptor cells are a classic example (Behrens and Wagner, 1996; La Vail, 1976), and insect axons within the lamina of the optic lobe also undergo a circadian shrinking and swelling cycle (Pyza and Meinertzhagen, 1995; Weber et al., 2009). In zebrafish, the clock rather than the sleep/wake cycle has a primary role in driving changes in synapse number within hypocretin/orexin (HCRT) neurons (Appelbaum et al., 2010). A circadian connection is usually based on one or both of two criteria: 1) the oscillations persist in constant darkness, i.e., a light-dark cycle is unnecessary; 2) they are abolished in arrhythmic clock gene mutants. However, there is no known direct molecular link between the core clock and rhythmic remodeling of s-LNv axonal projections (Fernandez et al., 2008), nor have they been linked to circadian behavioral rhythms.

How then does the core molecular clock direct this rhythmic remodeling, and is there an impact on circadian behavior? To elucidate molecular mechanisms, we turned to our previous analysis of mRNAs specifically enriched in the circadian clock neurons of Drosophila melanogaster (Kula-Eversole et al., 2010; Nagoshi et al., 2010). Among the top genes enriched in large LNvs as well as in small LNvs is the Drosophila ortholog of Mef2. Mef2 proteins respond to extracellular signals and then activate genetic programs controlling the cell differentiation, survival and apoptosis of many different cell types (for review, see (Potthoff and Olson, 2007)). Importantly, mammalian Mef2 also regulates activity-dependant synaptic and dendritic remodeling via the direct regulation of genes involved in neuronal morphology and plasticity (Fiore et al., 2009; Flavell et al., 2006; Flavell et al., 2008).

We show here that remodeling of s-LNv axons is due to a circadian fasciculation-defasciculation cycle, which requires the transcription factor Mef2. Mef2 also influences the ability of s-LNvs to change axonal arbor conformation in response to neuronal firing. Drosophila Mef2 activity is linked to the core molecular clock at least in part via its transcriptional regulation: Mef2 is a direct target of the master circadian regulator complex CLK/CYC. Moreover, Mef2 is epistatic to CLK/CYC activity, suggesting that Mef2 is the major CLK/CYC target gene driving the circadian regulation of neuronal morphology. To further study the role of this protein, we performed a genome-wide analysis of Mef2 DNA binding. The ChIP-Chip analysis identified numerous genes implicated in neuronal plasticity, and we show that the Mef2 target gene Fasciclin2 (Fas2), the Drosophila ortholog of neural cell adhesion molecule NCAM, affects neuronal remodeling of s-LNvs and is epistatic to Mef2. This is because genetic manipulations of Fas2 levels partially rescue effects of Mef2 overexpression not only on s-LNv morphology but also on circadian behavior. This indicates that the neuronal morphology changes are important for locomotor activity rhythms.

Results

Mef2 is necessary for circadian and activity-dependent changes in s-LNv axonal fasciculation

The Drosophila ortholog of Mef2 is primarily known for its prominent role in myogenesis and embryonic development. However, Blau and colleagues recently showed that Mef2 is present in clock neurons, that Mef2 levels show circadian fluctuations within s-LNvs and that these fluctuations require a functional clock. Moreover, alterations of Mef2 levels led to defects in circadian behavior (Blanchard et al., 2010). However, there is no mechanism underlying the requirement of Mef2 for sustained locomotor rhythms. Taken together with our own data ((Kula-Eversole et al., 2010; Nagoshi et al., 2010) and see below) as well as the mammalian literature (Fiore et al., 2009; Flavell et al., 2006; Flavell et al., 2008), these findings led us to hypothesize that the transcriptional activity of Mef2 might bridge the core molecular clock and the circadian plasticity of s-LNv termini (Fernandez et al., 2008).

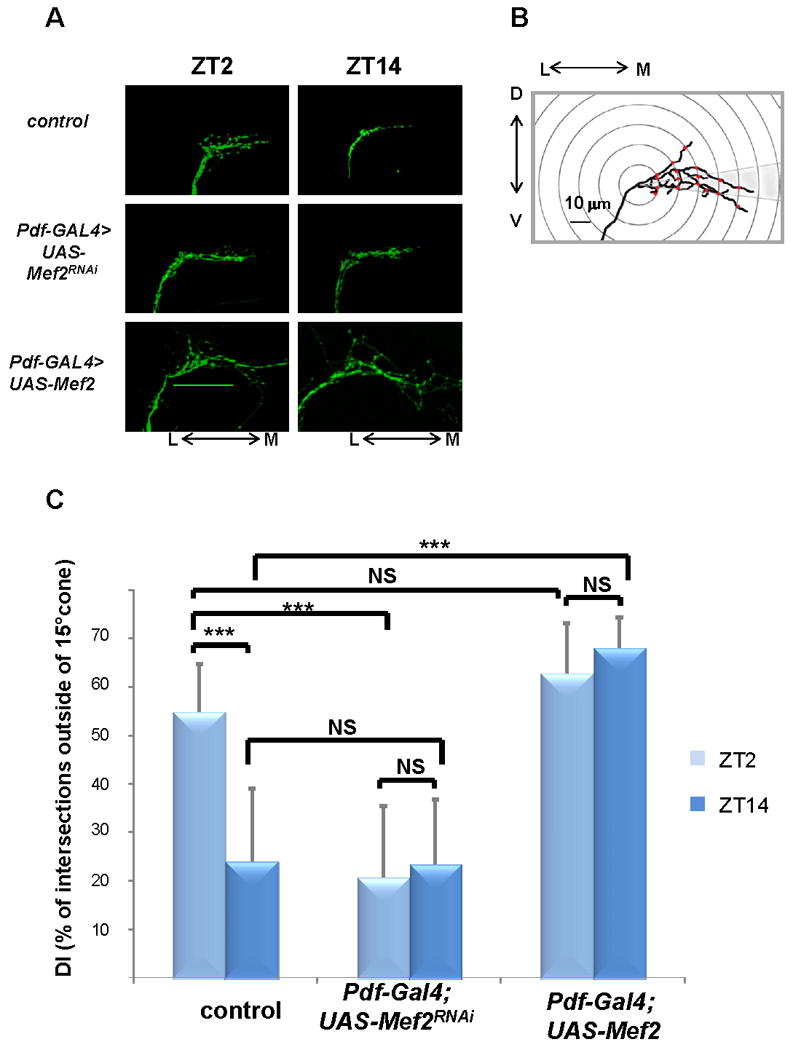

To address the role of Mef2 in the regulation of circadian plasticity of s-LNv projections, axonal morphology was visualized by confocal microscopy with a membrane-tethered version of GFP (mCD8-GFP) under the control of a Pdf specific promoter. In agreement with the results of Fernandez et al. (Fernandez et al., 2008), we observed readily apparent and highly reproducible differences in the axonal conformation of s-LNvs between ZT2 and ZT14, two hours after lights-on and two hours after lights-off, respectively (Fig. 1A, control and Fig. S1). Although diverse mechanisms could underlie these differences, there was evidence that variations in axonal fasciculation are important (Fernandez et al., 2008).

Figure 1. Genetic manipulations of Mef2 levels disrupt circadian and activity-dependent changes in axonal fasciculation of the s-LNv dorsal projections.

A) Representative confocal images of brains of control flies (yw, UAS-mCD8 GFP; Pdf –Gal4), and flies with reduced (yw, UAS-mCD8 GFP; Pdf-Gal4/+; UAS-Mef2RNAi/+) or increased (yw,UAS-mCD8 GFP; Pdf-Gal4/+; UAS-Mef2/+) levels of Mef2 in PDF cells at ZT2 and ZT14. Note open, defasciculated axonal conformation at ZT2 and fasciculated axons at ZT14 in control flies. Mef2RNAi flies exhibit fasciculated axonal morphology at both circadian time points, while Mef2 overexpression leads to severe axonal defasciculation. Scale bar 50μm. B) Schematic representing modified Sholl's analysis for quantification of fasciculation of axonal termini of s-LNv neurons (see Experimental Procedures). C) Analysis of axonal morphology (fasciculation) of s-LNv dorsal termini by modified Sholl's analysis. The plot represents percentage of intersections between concentric rings and axonal branches outside of a 15% cone (defasciculation index, DI). Statistically significant difference in DI between different genotypes and different time points is depicted by brackets. Circadian variation in DI at ZT2 and ZT14 is abolished in the flies with both decreased and increased Mef2 levels. Plots show mean values, error bars are SEM. *** represents p-value < 0.0001 (non parametric Mann-Whitney test). NS: not significant. For each time point and genotype 20 to 30 brains were analyzed. Two independent experiments were performed with similar results. See also Fig. S1.

To address this possibility, we modified standard Sholl's analysis and calculated the percentage of intersections between 10 μm concentric rings and axonal branches outside of a 15° cone (defasciculation index, DI) as a fasciculation proxy (Fig. 1B). Whereas more than 50% of intersections fell outside of the 15° cone at ZT2, the DI was 23.9% at ZT14, indicating substantially increased fasciculation of s-LNv axons at ZT14 (see Fig. 1C; the difference was statistically significant with a P value<0.0001 in a non-parametric Mann-Whitney test). Although a fasciculation-defasciculation rhythm may not be the sole relevant mechanism (see Discussion), we will use these terms to describe the rest of the experiments.

We next used this quantification method to address the effect of Mef2 activity on circadian changes of s-LNv axonal fasciculation. Because null mutants of Mef2 as well as flies that overexpress Mef2 ubiquitously do not survive to adulthood ((Bour et al., 1995) and not shown), we manipulated Mef2 levels in small and large LNvs genetically, by using a Pdf- Gal4 driver to target expression of either an UAS-Mef2 or an UAS –Mef2 RNAi construct. To visualize the circuitry of s-LNv cells with altered Mef2 levels, UAS–mCD8-GFP (Lee and Luo, 1999) was added to the strain.

Increased expression of wild type Mef2 led to dramatic changes in s-LNv axonal morphology. Their dorsal projections appeared severely defasciculated and mistargeted beyond the dorso-medial defasciculation point (Fig. 1A). Reduction of native Mef2 activity through selective expression of a RNAi element resulted in the opposite effect on fasciculation: axons acquired a closed conformation resembling the one normally observed at ZT14 in wild type flies (Fig. 1A) as well as a slight overextension of axons towards the midline. Importantly, both overexpression and RNAi knockdown of Mef2 also completely abolished the fasciculation differences between ZT2 and ZT14 (Fig. 1C). In flies overexpressing Mef2, we observed a DI above 60% at both ZT2 and ZT14, whereas knockdown of Mef2 led to increased fasciculation at the same time points (DI <30%).

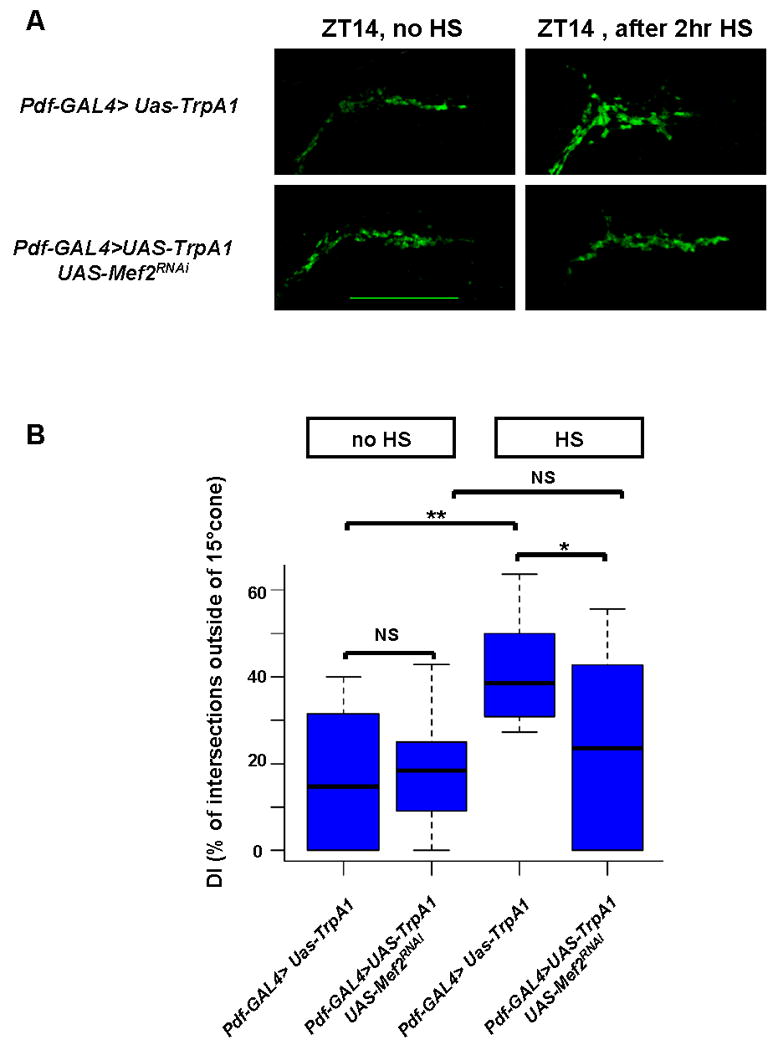

It was recently shown that s-LNv axonal arbor complexity is modified in response to electrical activity: adult–specific silencing of PDF cells resulted in decreased complexity, i.e., an overfasciculated phenotype (Depetris-Chauvin et al., 2011). In agreement with this report, activation of PDF neurons for 2 hours with the temperature-gated TrpA1 channel (Hamada et al., 2008; Parisky et al., 2008) caused an open (defasciculated) conformation of s-LNv dorsal termini at ZT14. This contrasts with the closed (fasciculated) conformation seen at this time in control flies (Fig. 2A and B; p-value <0.005, non parametric Mann-Whitney test). A similar 2 hour temperature increase had no effect on control lines (Pdf-Gal4/+, UAS-TrpA1/+ and Pdf-Gal4>UAS-mCD8GFP) fly lines (Fig. S2A, B). Similar to the role of mammalian Mef2 in activity-dependent neuronal plasticity (Fiore et al., 2009; Flavell et al., 2006; Flavell et al., 2008), activation of PDF cells with TrpA1 in a Mef2 RNAi knockdown strain induced defasciculation of the s-LNv dorsal termini (DI>30%) in only ∼40% of brains, in contrast to ∼ 90% in wild-type brains (data not shown); the DI difference is statistically significant (Fig. 2B, p-value=0.01, non parametric Mann-Whitney test). This was not due to the extra UAS as addition of a control UAS-mCherry element to a background fly line did not decrease axonal defasciculation in response to TrpA1 activation (Fig. S2C, D). The incomplete effect of the Mef2 knockdown probably reflects residual Mef2 activity and/or the very strong effect of TrpA1 on firing. An additional possibility is that Mef2-independent pathways also contribute to activity-induced axonal defasciculation.

Figure 2. Mef2 is required for activity-dependent remodeling of s-LNv axonal projections.

A) Induction of TrpA1 in PDF cells by 2 hour temperature elevation to 29°C leads to open conformation of s-LNv dorsal projections at ZT14 in a wild type background. This effect is markedly reduced in an UAS-Mef2RNAi genetic background. Confocal images of fly brains after a 2 hour TrpA1 induction are representative of ∼ 90% of yw; Pdf-Gal4, UAS-mCD8GFP /UAS-TrpA1 flies and of ∼60% of yw; Pdf-Gal4, UAS-mCD8GFP /UAS-TrpA1; UAS-Mef2RNAi/+flies. Scale bar 25 μm. B) Quantification of TrpA1- induced changes in axonal fasciculation by modified Sholl's analysis. Box plot diagram of defasciculation indexes (DI) in the same genotypes as in Figure 2A. Statistically significant difference in axonal fasciculation upon TrpA1 induction is observed in wild type (p-value <0.005, non parametric Mann-Whitney test), but not in Mef2 RNAi genetic background (p-value=0.5). Morphology of dorsal termini after TrpA1 activation significantly differs between Pdf-GAL4>UAS-TrpA1 and Pdf-GAL4>UAS-TrpA1+UAS-Mef2RNAi flies (p-value =0.01). ** represents p-value < 0.005, * represents p-value = 0.01 (non parametric Mann-Whitney test). NS: not significant. 16 to 20 brains were analyzed for each genotype and experimental condition. See also Fig. S2.

Mef2 affects neuronal morphology via transcriptional regulation of genes implicated in neuronal remodeling

To gain further insight into the molecular mechanisms that underlie Mef2 function in the circadian system, direct Mef2 target genes were identified with chromatin prepared from Drosophila adult heads. We analyzed the data with genome-wide tiling arrays (ChIP-Chip) and an antibody against isoform D of Mef2 (Sandmann et al., 2006). The same antibody had been successfully used for identification of Mef2 targets in Drosophila embryos (Junion et al., 2005; Sandmann et al., 2006). We also addressed rhythmic binding of Mef2 to its genomic targets, i.e., the ChIP-Chip analysis was done on chromatin from fly heads collected at 6 different time points spanning the 24 hr light-dark cycle.

Mef2 binds to a large number of sites in the Drosophila genome (Table S1), and many of these were previously identified as Mef2 targets genes in Drosophila embryos (Sandmann et al., 2006); the overlap between the two gene lists is statistically significant (data not shown). Modified Fourier analysis (Wijnen et al., 2005) of the 6 times points revealed rhythmic oscillations of Mef2 binding to a significant fraction of these loci. Maximal Mef2 binding was always in the latter half of the night and early morning, from approximately ZT17 to ZT2 (Fig. S3A). This temporal pattern of Mef2 chromatin cycling is in agreement with the gene expression data, which shows an increase of Mef2 transcript levels in PDF neurons during the night ((Kula-Eversole et al., 2010) and Fig 5B), as well as with the described oscillations of Mef2 protein levels in these cells, with maximal Mef2 nuclear accumulation at ZT22 (Blanchard et al., 2010). We further validated Mef2 binding as well as cycling on several promoters by qRT-PCR analysis of 3 independent experimental repeats (Fig. S3B, Table S2).

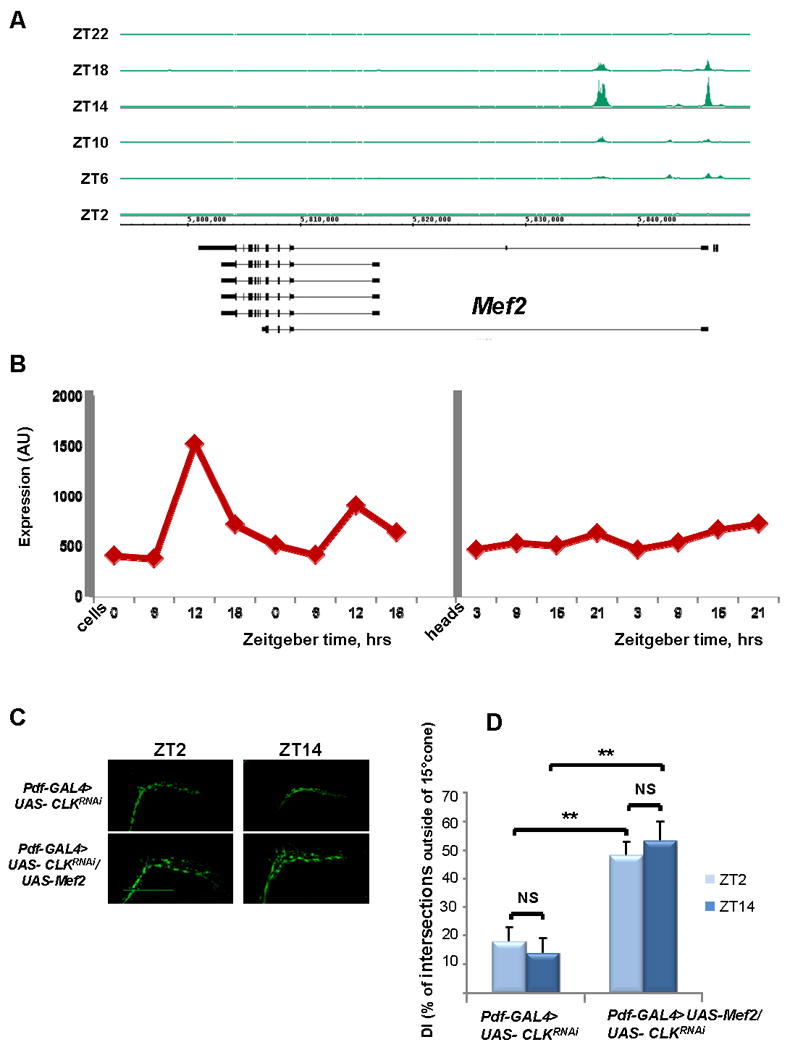

Figure 5. Mef2 is a direct target of CLK/CYC.

A) Cyclical CLK binding to Mef2 promoter region. CLK ChIP was performed at 6 time points (ZT2, ZT6, ZT10, ZT14, ZT18, and ZT22), and immunoprecipitated DNA was analyzed by tiling arrays (Affymetrix). CLK binding is visualized with Integrated Genome Browser (IGB). Mef2 is on the bottom strand and therefore transcription occurs from right to left. CLK binds to the 5′-end of Mef2 and binding is maximal at ZT14. B) Mef2 mRNAs cycles in large LNv pacemaker cells but not in heads. Mef2 RNA from either heads(McDonald and Rosbash, 2001) or LNvs(Kula-Eversole et al., 2010; Nagoshi et al., 2010) was analyzed via expression microarrays (Affymetrix). Levels of Mef2 mRNA are shown across four timepoints in clock neurons (ZT0, ZT6, ZT12, and ZT18) and in heads (ZT3, ZT9, ZT15, and ZT21). (C,D) Mef2 expression in PDF cells rescues Clk RNAi-induced increase in axonal fasciculation. Reduction of Clk levels in PDF cells by RNAi results in loss of the circadian plasticity and increased fasciculation of s-LNv dorsal projections. Concurrent overexpression of Mef2 in PDF cells leads to defasciculated axonal conformation resembling a Mef2 overexpression phenotype. (C) Representative confocal images of yw; Pdf-GAL4, UAS-mCD8 GFP/+; UAS- ClkRNAi/+ and yw; Pdf-GAL4, UAS- mCD8 GFP/+; UAS- ClkRNAi/UAS-Mef2 fly brains at ZT2 and ZT14. Scale bar 50 μm. (D) Quantification of axonal fasciculation of dorsal projections of s-LNvs in the same genotypes as in Figure 5C. Modified Sholl's analysis reveals increased fasciculation and lack of circadian variation in the defasciculation index (DI) in yw; Pdf-GAL4, UAS- mCD8 GFP/+; UAS- ClkRNAi/+ axons (p-value =0.22). Co-expression of UAS-Mef2 transgene results in statistically significant increased DI as compared to ClkRNAi (P value < 0.005 at both ZT2 and ZT14), but doesn't rescue the circadian plasticity of s-LNv axons (p-value = 0.16). Plots show mean values, error bars are SEM. ** represents p-value < 0.005, non parametric Mann-Whitney test. NS: not significant. At least 10 brains were analyzed for each genotype and time point. The experiment was performed twice with very similar results.

Gene ontology analysis of the top Mef2 target genes from fly heads revealed enrichment for genes with a variety of functions within the CNS, including axonogenesis, axon guidance, behavior, synaptogenesis and memory (Table 1). We focused on potential molecular pathways that could underlie the effects of Mef2 on neuronal morphology. Among these Mef2 target genes, Fasciclin 2 (Fas2), the Drosophila ortholog of the neural cell adhesion molecule NCAM, peaked our interest. Although no effect of Fas2 on circadian behavior has been described in the literature, our previous gene expression data revealed rhythmic oscillations of the Fas2 transcript in PDF cells, suggesting that Fas2 activity is under circadian control ((Kula-Eversole et al., 2010) and Fig. S4C). Notably, Fas2 mRNA levels are highest at the end of the day, roughly antiphasic to the peak of Mef2 binding to the Fas2 promoter (Fig. S4A, B). As overexpression of Mef2 in Pdf cells results in a marked decrease of Fas2 mRNA levels (Fig. 3A), the data suggest that Mef2 binding negatively regulates Fas2 expression.

Table 1. Gene ontology analysis of Mef2 top target genes reveals an enrichment of genes that function in the nervous system.

The 450 top Mef2 peaks were visually mapped, rendering a list of 342 peaks that we were able to assign to a single gene (see also Table S1, Fig.S3 for validation of Mef2 binding by q-PCR and Table S2 for primer sets used in this study). Gene ontology analysis of the resulting gene list was performed by GoToolbox software.

| GO category | # genes | p-value | Genes |

|---|---|---|---|

| nervous system development | 47 | 9.45E-11 | dnc, fray, Dad, Mbs, fru, brk, raw, emc, ph-p, Fmr1, sdk, sr, puc, chic, Sin3A, sty, sgg, Mi-2, caps, bun, glec, Lis-1, jeb, pum, retn, beta-Spec, Sdc, Fas2, InR, 14-3-3zeta, foi, kay, sif, spen, exba, spin, Ptp61F, dl, CdGAPr, Sema-1a, h, lola, cpo, klg, EcR, mys, jar |

| regulation of transcription | 45 | 1.00E-09 | Eip75B, Smr, Mnt, CG9775, NfI, vri, Dad, tai, brk, Pdp1, ph-d, CtBP, emc, ph-p, sr, Eip74EF, cnc, Sin3A, Hr38, NK7.1, Kr-h1, CrebB-17A, cbt, tara, sgg, NFAT, CHES-1-like, Mi-2, bun, Mef2, cwo, crp, pum, retn, Atf-2, CG13624, kay, spen, Alh, dl, h, lola, bin3, lin-52, EcR |

| behavior | 35 | 1.81E-09 | dnc, nmo, shep, vri, stnA, wun, Rtnl1, fru, Pino, emc, Fmr1, CG14509, scrib, CrebB-17A, CG17836, sgg, pum, retn, Fas2, bnl, unc-104, 14-3-3zeta, Bx, for, exba, spin, Sema-1a, Rdl, lola, cpo, klg, bin3, EcR, shakB, Gpdh |

| axonogenesis | 20 | 1.54E-07 | dnc, fray, Dad, Fmr1, caps, jeb, retn, beta-Spec, Sdc, Fas2, InR, sif, spen, exba, Ptp61F, CdGAPr, Sema-1a, lola, EcR, mys |

| axon guidance | 15 | 6.30E-07 | Dad, Fmr1, caps, jeb, retn, beta-Spec, Sdc, InR, spen, exba, Ptp61F, CdGAPr, Sema-1a, lola, mys |

| circadian rhythm | 10 | 9.59E-07 | dnc, vri, Pdp1, Fmr1, CrebB-17A, sgg, cwo, Bx, W, Rdl |

| memory | 7 | 1.32E-05 | dnc, CrebB-17A, pum, Fas2, for, exba, klg |

| regulation of synapse structure and activity | 7 | 2.70E-05 | Fmr1, scrib, pum, beta-Spec, Fas2, sif, spin |

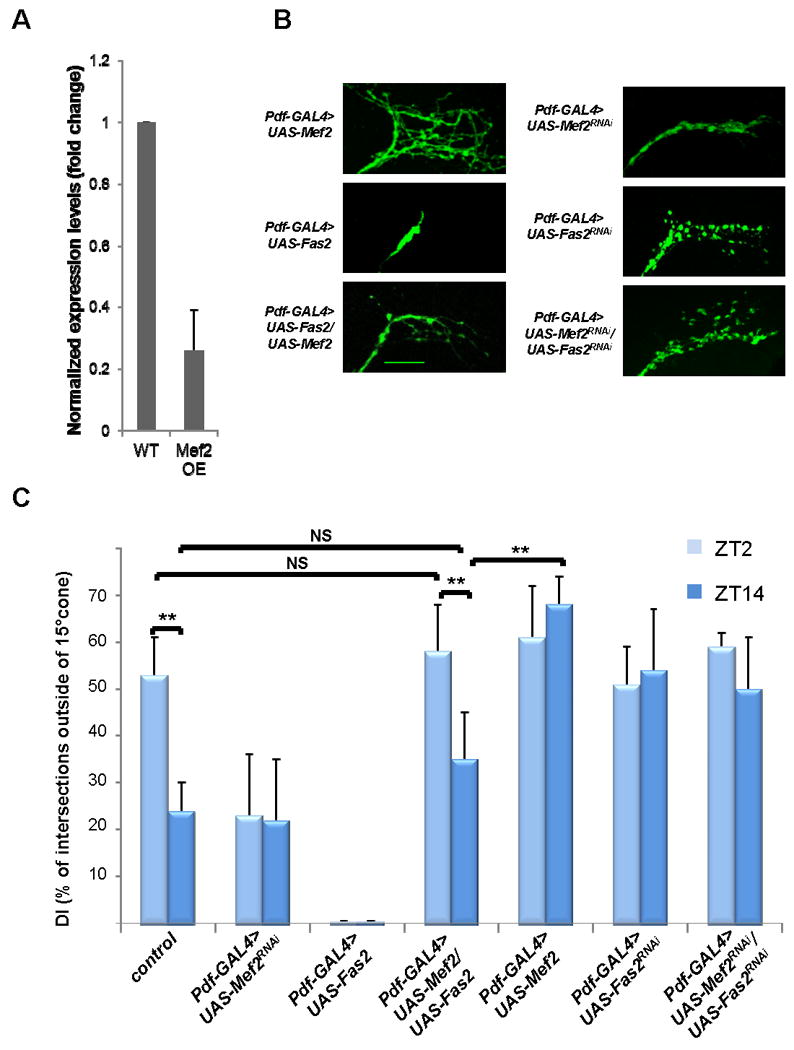

Figure 3. Mef2 transcriptional target Fas2 affects neuronal morphology and is genetically epistatic to Mef2.

A) Fas2 is negatively regulated by Mef2 in Pdf cells. Mef2 overexpression in Pdf cells results in a marked decrease in Fas2 mRNA levels within those cells. RNA was extracted from PDF cells purified from yw; Pdf-Gal4, UAS-mCD8 GFP (wild type control WT) and yw; Pdf-Gal4, UAS-mCD8 GFP /+; UAS-Mef2/+ flies (Mef2 overexpression OE) at ZT12. The mRNA values for Fas2 were normalized to those of RPL32 (see also Fig. S4 and Table S2 for primer sequences). Plots show mean values, error bars are SEM. B) Overexpression of Fas2 in PDF cells leads to collapse and overfasciculation of s-LNv axonal arbor in wild type background, and rescues defasciculated phenotype in Mef2 overexpression background. Pdf-Gal4, UAS-mCD8 GFP>UAS-Fas2RNAi flies exhibit open conformation of s-LNv axons. The same phenotype is observed when UAS-Fas2RNAi is expressed in Pdf-GAL4>UAS-Mef2RNAi background, suggesting that Fas2 is genetically downstream and possibly is negatively regulated by Mef2. Images are taken at ZT2. Scale bar 25 μm. C) Analysis of axonal morphology (fasciculation) of s-LNv dorsal termini by modified Sholl's analysis at ZT2 and ZT14 in LD in the same genotypes as in Fig. 3B. Pdf-GAL4>UAS-Fas2 flies display severely overfasciculated conformation at both ZT2 and ZT14. Dorsal s-LNv projections undergo normal circadian remodeling in Pdf-GAL4>UAS-Fas2/UAS-Mef2 flies. Pdf-GAL4>UAS- Fas2RNAi and Pdf-GAL4>UAS- Fas2RNAi/UAS- Mef2RNAi show similar defasciculated phenotype and no significant differences in DI between ZT2 and ZT14. Plots show mean values, error bars are SEM. ** represents Pvalue <0.01, non-parametric Mann-Whitney test. NS: not significant. See also Fig. S5.

Because, Fas2 has been reported to affect neuronal morphology and increase intraaxonal adhesion in Drosophila embryos (Miller et al., 2008; Yu et al., 2000), we examined the effect of altering Fas2 levels within PDF neurons. Consistent with its role in promoting intraaxonal adhesion, Fas2 overexpression in PDF cells caused a dramatic increase in fasciculation of s-LNv axons both at ZT2 and ZT14 (Fig. 3B, Fig. 3C and data not shown). There was an opposite, defasciculated phenotype when Fas2 levels in PDF cells were reduced by RNAi (Fig. 3B and 3C and data not shown), also without apparent temporal regulation.

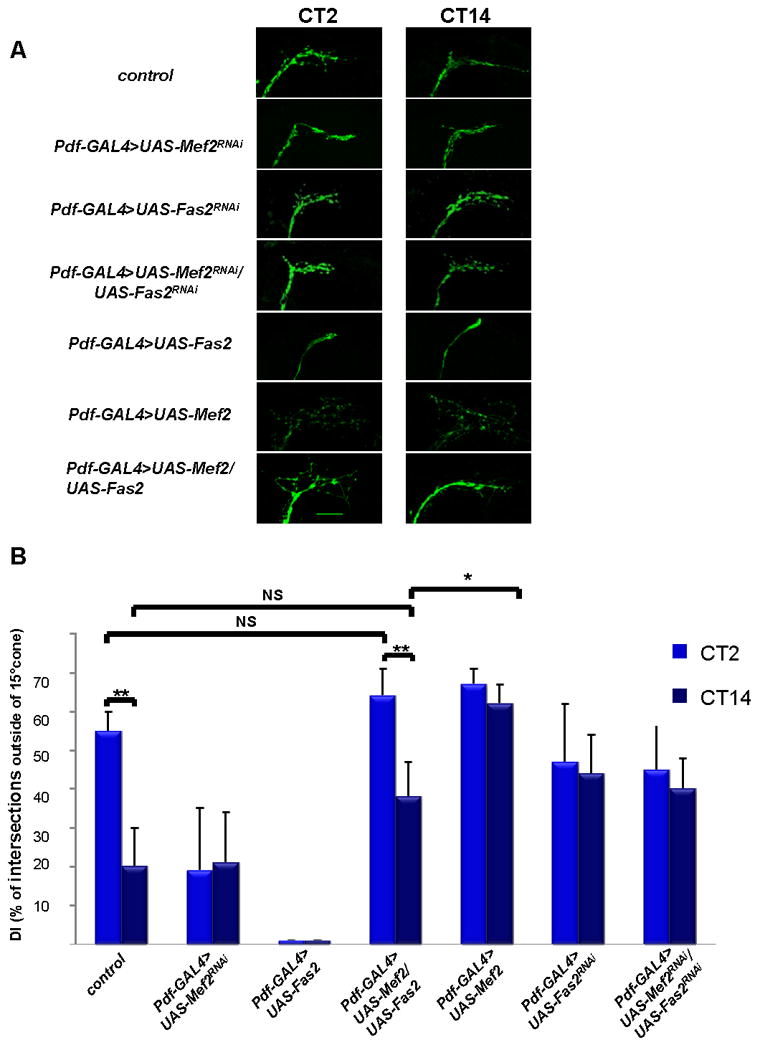

We next established that Fas2 is genetically epistatic to Mef2: reduction of Fas2 levels by RNAi in a Mef2 RNAi background mirrored the defasciculated Fas2 RNAi phenotype, whereas co-expression of UAS-Fas2 and UAS-Mef2 in PDF cells rescued Mef2–induced axonal defasciculation (Fig. 3B and C). Surprisingly, overexpression of Fas2 in a Pdf-GAL4>UAS-Mef2 background was even sufficient to restore circadian changes in fasciculation of s-LNv projections (Fig. 3C). The effect was due to Fas2 overexpression and not the additional UAS element, because it was not phenocopied by addition of a control UAS-mCherry element to the Mef2 overexpression background (Fig. S5). This suggests that Fas2 is a major Mef2 target for the s-LNv fasciculation cycle. In agreement with the notion that the morphology and remodeling of s-LNvs are regulated by the circadian clock (Fernandez et al., 2008), these LD phenotypes were indistinguishable in DD (Fig. 4A and B).

Figure 4. PDF-cell specific increases in Fas2 levels rescue abnormal axonal morphology and circadian plasticity in Mef2 overexpression background in DD.

A) Representative confocal images of yw; Pdf-GAL4, UAS-mCD8 GFP (control), yw; Pdf-GAL4, UAS-mCD8 GFP/+; UAS-Mef2RNAi/+, yw; Pdf-GAL4, UAS-mCD8 GFP >UAS- Fas2RNAi, yw; Pdf-GAL4, UAS-mCD8 GFP >UAS- Fas2RNAi/UAS- Mef2RNAi, yw; Pdf-GAL4, UAS-mCD8 GFP/+; UAS-Fas2 /+, yw; Pdf-GAL4, UAS-mCD8 GFP/+; UAS-Mef2/+, and yw; Pdf-GAL4, UAS-mCD8 GFP/+;UAS-Mef2/UAS-Fas2 fly brains at CT2 and CT14 on the day 2 in DD. Scale bar 25 μm. B) Quantitative analysis of axonal morphology in the same genotypes as in Fig. 4A on day 2 in DD. Overexpression of Fas2 in Pdf-Gal4>UAS-Mef2 background increases axonal fasciculation at CT14 and restores circadian variations in DI. No significant difference between Pdf-Gal4>UAS-Mef2/UAS-Fas2 and control flies observed at both CT2 and CT14. 10 - 12 brains were analyzed for each genotype and time point, experiment was performed twice with very similar results. Plots show mean values, error bars are SEM. ** represents p-value < 0.01, * represents p-value =0.05, non parametric Mann-Whitney test. NS: not significant. See also Fig. S5.

To examine the effects of PDF cell remodeling and/or morphology on behavior, we assayed the free-running locomotor activity rhythms of strains with altered Mef2 and Fas2 levels. Surprisingly, the constant fasciculated phenotypes (i.e., the Mef2 knockdown by RNAi and Fas2 overexpression) were without effect. The constant defasciculated phenotype in contrast, i.e., Pdf-Gal4>UAS-Mef2 flies, was associated with substantial arrhythmicity as previously reported (Blanchard et al., 2010) (Table 2). Flies with decreased Fas2 levels in LNvs also manifest constant defasciculation of s-LNv axons (albeit a weaker morphological phenotype than Mef2 overexpression (Fig. 3B, 3C, and data not shown)), and these flies had a substantially weaker behavioral phenotype than Pdf-Gal4>UAS-Mef2 flies, namely, only about 80% rhythmic flies on days 1-4 of DD and 69% rhythmic flies on days 5-8 compared to ∼98% for control strains (P value <0.01 Fisher test, Table 2). Similar morphological and behavioral phenotypes (P value >0.5 Fisher test, Table 2) were observed with Pdf-GAL4>UAS- Fas2RNAi/UAS- Mef2RNAi flies.

Table 2. Increasing of Fas2 levels in a Mef2 overexpression background improves circadian rhythmicity.

Analysis of adult locomotor activity on DD1-4 and DD 5-9 in flies with altered Mef2 and Fas2 levels in PDF cells, showing number of flies analyzed (n), percentages of flies exhibiting arrhythmic (AR%), weakly rhythmic (WR%), or rhythmic (R%) behavior, averaged period length for rhythmic flies and SEM. Locomotor behavior is unaffected in Pdf-GAL4>UAS-Mef2RNAi and Pdf-GAL4>UAS-Fas2 flies. Fas2 knockdown by RNAi in wild type and Mef2RNAi background results in decrease in the percentage of rhythmic flies on DD5-9 (p<0.01, Fisher test). Overexpression of Fas2 in Pdf-GAL4>UAS-Mef2 background significantly increases percentage of rhythmic flies on DD1-4 (p<0.01, Fisher test). There is no significant change in rhythmicity due to the addition of an extra UAS element, as PDF-GAL4>UAS-Mef2/UAS-mCD8GFP is indistinguishable from Pdf-Gal4>UAS-Mef2 (P value >0.5 Fisher test), see also Fig. S5.

| n | AR % |

WR % |

R % |

Period (hrs) |

SEM (hrs) |

n | AR % |

WR % |

R % |

Period (hrs) |

SEM (hrs) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pdf-GAL4/+ | 26 | 0 | 1 | 99 | 24.3 | 0.09 | 30 | 0 | 3 | 97 | 23.9 | 0.1 |

| UAS-Mef2/+ | 34 | 0 | 3 | 97 | 24.3 | 0.16 | 34 | 0 | 3 | 97 | 24.1 | 0.17 |

| UAS-Mef2RNAi/+ | 22 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 24.2 | 0.08 | 32 | 3 | 0 | 97 | 24.5 | 0.13 |

| UAS-Fas2/+ | 36 | 0 | 5 | 95 | 23.7 | 0.15 | 36 | 0 | 5 | 95 | 23.9 | 0.19 |

| UAS-Fas2RNAi/+ | 22 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 24.2 | 0.1 | 22 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 24 | 0.2 |

| UAS-mCD8GFP | 27 | 0 | 3 | 97 | 23.6 | 0.2 | 27 | 0 | 2 | 98 | 23.7 | 0.18 |

| Pdf-GAL4>UAS-Mef2RNAi | 32 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 23.8 | 0.06 | 32 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 24 | 0.09 |

| Pdf-GAL4>UAS-Fas2RNAi | 38 | 8 | 10 | 82 | 23.9 | 0.12 | 38 | 13 | 18 | 69 | 24 | 0.18 |

| Pdf-GAL4>UAS-Fas2RNAi/UAS- Mef2RNAi | 41 | 4 | 7 | 89 | 23.9 | 0.1 | 41 | 12 | 7 | 81 | 23.5 | 0.2 |

| Pdf-GAL4>UAS-mCD8GFP | 27 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 23.95 | 0.13 | 27 | 0 | 3 | 97 | 24 | 0.1 |

| Pdf-Gal4>UAS-Fas2 | 28 | 0 | 2 | 98 | 24.05 | 0.09 | 30 | 0 | 3 | 97 | 24.05 | 0.09 |

| Pdf-Gal4>UAS-Mef2 | 62 | 40.1 | 24.5 | 35.4 | 23.7 | 0.4 | 30 | 40 | 30 | 30 | 23.5 | 0.41 |

| Pdf-Gal4>UAS-Mef2/UAS-mCD8GFP | 42 | 36 | 28 | 36 | 23.4 | 0.5 | 42 | 32 | 36 | 32 | 23.19 | 0.5 |

| Pdf-Gal4>UAS-Mef2/UAS-Fas2 | 44 | 18.2 | 20.5 | 61.3 | 24.1 | 0.41 | 42 | 28.5 | 24 | 47.5 | 23.75 | 0.47 |

Importantly, overexpression of Fas2 in the Pdf-Gal4>UAS-Mef2 background not only rescued the constant defasciculation of the background strain but also significantly increased the percentage of rhythmic flies (P value <0.01 Fisher test, Table 2). There was no significant change in rhythmicity due to the addition of an extra UAS element, i.e., PDF-GAL4>UAS-Mef2/UAS-mCD8GFP is indistinguishable from Pdf-Gal4>UAS-Mef2 (P value >0.5 Fisher test Table 2). These data strongly indicate that PDF neuron defasciculation contributes to the Mef2 overexpression phenotype.

Mef2 is directly regulated by CLK/CYC

How is Mef2 itself regulated? CLK and CYC ChIP-Chip experiments in our laboratory identified Mef2 as a direct target of CLK and CYC (Abruzzi et al., 2011), and the Mef2 promoter manifests canonical cycling of CLK/CYC binding with peak levels at ZT14 (Fig. 5A). Indeed, previous expression analysis (Kula-Eversole et al., 2010) demonstrated that Mef2 transcript levels cycle in l-LNvs with a peak phase consistent with this rhythmic CLK binding (Fig. 5B). As Mef2 transcript levels do not oscillate in whole Drosophila heads (see Fig. 5B and (McDonald and Rosbash, 2001)), we speculate that Mef2 is regulated by rhythmic CLK binding only in certain cell-types (see Discussion). This notion is in agreement with the previously observed decrease of Mef2 staining levels within PDF neurons in the clk and cyc mutants, Clkar and cyc01 respectively (Blanchard et al., 2010). To verify that the link between CLK and neuronal plasticity goes through Mef2, we assayed the epistatic relationship between Clk and Mef2. As the loss-of-function Clk mutant ClkJrk leads to loss of s-LNv neurons ((Park et al., 2000) and data not shown), we used RNAi to decrease Clk activity levels in PDF cells.

The knockdown causes arrhythmic locomotor behavior (F.G. and M.R., data not shown) and disrupts rhythmic remodeling of s-LNv projections as expected. In addition to the loss of circadian plasticity, the Clk knockdown causes an over-fasciculated phenotype, also characteristic of the Mef2 RNAi knockdown (Fig. 5C). Constitutive expression of UAS–Mef2 in the Clk RNAi background gave rise to the opposite phenotype, strong defasciculation; this is characteristic of the morning (ZT2) when Mef2 levels are high. As there is no detectable morphological cycling in either the Clk knockdown or the Mef2 rescue (Fig. 5D), Clk is upstream of Mef2 and cycling CLK/CYC activity is important for the circadian regulation of neuronal morphology.

Discussion

Although the reported circadian fasciculation-defasciculation cycle of adult Drosophila s-LNv neurons (Fernandez et al., 2008) had no known molecular connection to the core clock, we report here that the cycle requires the transcription factor Mef2. Mef2 is a direct target of the CLK/CYC complex, which is likely related to the observed mRNA and protein oscillations of Mef2 within PDF cells. Because the fasciculation phenotype of a Clk knockdown is rescued by Mef2 overexpression, it may function as the principal target of the CLK/CYC complex affecting neuronal morphology. Mef2 itself targets numerous genes affecting neuronal development and morphology including Fas2. This gene is genetically epistatic to Mef2, as increasing Fas2 levels rescues Mef2 overexpression effects on behavior as well as neuronal morphology. The results indicate that the transcription factor Mef2 links the CLK/CYC complex to Fas2, to circadian alterations in neuronal morphology and even to locomotor activity rhythms.

The mammalian Mef2 family is known to translate extra- and intracellular signals into transcriptional activity in multiple cells types and tissues of different species (Potthoff and Olson, 2007). This role is achieved via diverse mechanisms, which include transcriptional, translational, and post-translational mechanisms as well as collaboration with specific co-regulators (Black et al., 1998; Molkentin and Olson, 1996; Nojima et al., 2008; Sandmann et al., 2007). Neuronal processes are regulated by Mef2, and it also regulates stimulus-dependent changes in synapse number (Flavell et al., 2006). In addition, mammalian Mef2 often plays opposing roles in the regulation of neuronal plasticity. For example, it promotes synapse development during early neuronal differentiation (Li et al., 2008) and then restricts synaptic number at later stages of development (Barbosa et al., 2008). It has similar dual effects on dendritogenesis, affecting it positively via the miR379–410 cluster (Fiore et al., 2009) and negatively in response to cocaine (Pulipparacharuvil et al., 2008). This is likely due to the regulation of different gene sets at different times of development. Despite this complexity, it is possible that Mef2 plays a simple “linear” role in the described cycling of Drosophila PDF neuron fasciculation: the core clock cyclically regulates Mef2 expression, and Mef2 then cyclically regulates, either positively or negatively (such as in the case of Fas2), the transcription of genes functioning in neuronal remodeling (Fig. 6).

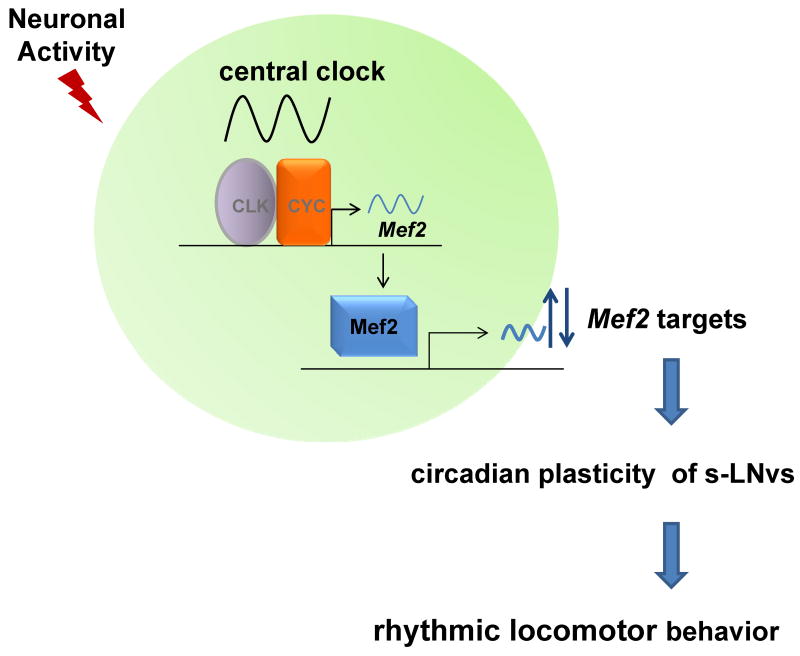

Figure 6. Mef2 integrates the core circadian oscillator with neuronal activity to regulate neuronal morphology in s-LNv neurons.

Rhythmic binding of CLK/CYC to Mef2 promoter results in the oscillations of the Mef2 transcript, as well as cycling of Mef2 protein levels in PDF cells. Mef2 then directly regulates a large group of genes that function in neuronal remodeling, such as Fas2, thus linking the core molecular clock to morphological changes in s-LNv projections. Neuronal activity may possibly influence s-LNv remodeling by modulating the core molecular clock, Mef2 transcriptional activity, or directly affecting post-transcriptional regulation or function of Mef2 target gene products. Rhythmic changes in s-LNv neuronal morphology can serve as a mechanism by which core circadian neurons transmits clock information to downstream systems, which ultimately results in rhythmic locomotor activity.

Relevant to this model are recent experiments in Drosophila by Blau and coworkers, demonstrating cycling Mef2 levels within s-LNv neurons (Blanchard et al., 2010). This is also the case for Mef2 mRNA itself, which is highly enriched in PDF neurons and cycles within these cells although not in head RNA (Fig. 5B and (Kula-Eversole et al., 2010; McDonald and Rosbash, 2001)). Taken together with the data showing that Mef2 is a direct target of the CLK/CYC complex (Fig. 5A), the mRNA enrichment and restricted cycling suggest that CLK binding to the Mef2 promoter is spatially limited and includes PDF neurons.

Mef2 is also important for the activity-dependent plasticity of s-LNv neuron morphology (Fig. 2A). It is notable that the effect of firing on s-LNv morphology fits with the reported increase of s-LNv electrical activity around lights-on (Cao and Nitabach, 2008); this is when the open conformation of the s-LNv dorsal projections is normally observed. Although neuronal firing may affect core circadian oscillator function to influence these circadian morphological changes, we prefer the interpretation that it acts primarily downstream, to influence Mef2 transcriptional activity and possibly Mef2 levels as shown in mammalian and amphibian experiments (Chen et al., 2012; Cole et al., 2012). Alternatively, firing may modulate Mef2 activity via posttranslational modification (Flavell et al., 2006; Shalizi et al., 2006).

To identify Mef2 target genes, we performed ChIP-Chip analysis on fly head chromatin. Mef2 binding undergoes circadian cycling, and among its top targets are genes relevant to neuronal function, axonal fasciculation and cell adhesion. These include the gene encoding the NCAM homolog Fas2 as well as genes implicated in various aspects of axonal cytoskeleton dynamics, which influence both actin (e.g., Ptp61F, fray, sif, Sema-1A and the Profilin homolog chickadee) and microtubules (Fmr1 and tau). Like Mef2, Fas2 and some other genes involved in cytoskeletal dynamics have cycling mRNAs in purified Drosophila PDF neuron RNA but not in whole head RNA (Kula-Eversole et al., 2010; Nagoshi et al., 2010).

The contribution of axonal fasciculation to circadian changes in s-LNv morphology was originally proposed (Fernandez et al., 2008) based in part on the circadian regulation of cell adhesion molecules in adult Drosophila (Ceriani et al., 2002; McDonald and Rosbash, 2001). However, it is possible the circadian morphological changes of PDF axons reflect additional mechanisms, including changes in axonal sprouting and retraction as well as fasciculation. The extreme truncated phenotype of Fas2 overexpression makes some contribution from sprouting-retraction likely. In any case, Fas2 overexpression clearly rescues the Mef2 overexpression phenotype (Fig. 3). We interpret the failure of Fas2 overexpression to allow circadian morphological changes in an otherwise wild-type background to be due to excess Fas2. Mef2 overexpression should reduce endogenous Fas2 levels, which may bring overall Fas2 into a biologically acceptable range.

Fas2 overexpression also improved the circadian behavior of the Mef2-overexpressing flies (Table 2). In contrast, it did not alter their period length variability (Table 2), indicating that the improved rhythmicity is a selective feature of increasing Fas2 expression. Although this cell adhesion molecule could function indirectly, the most parsimonious interpretation is that it promotes fasciculation, which then improves rhythmicity. The considerably weaker behavioral phenotype of Fas2 knockdown than Mef2 overexpression may indicate that misexpression of other Mef2 target genes within PDF neurons synergizes with the constant defasciculation to negatively impact behavioral rhythmicity. Another possibility is that the weaker phenotype of the Fas2 knockdown is due to its weaker morphological effect (Fig. 3, Fig 4). In any case, even the knockdown of Mef2 has no behavioral phenotype despite the lack of circadian plasticity and constant fasciculation. (Although a very mild behavioral phenotype was reported for Mef2 knockdown, it included overexpression of Dicer-2 (Blanchard et al., 2010),. The circadian plasticity may therefore function principally to downregulate defasciculation at certain times of day.

It is interesting in this context that synapse number and synapse size within these same PDF processes have been recently connected to sleep-wake regulation (Bushey et al., 2011). Intriguingly, the synapse assays have not been connected to the circadian cycle, nor has the PDF axonal remodeling assay been connected to the synapse assays or to sleep. Further exploration of PDF neuron morphological changes and the role of Mef2 might be a useful platform to dissect the interface between the contributions of circadian and homeostatic processes to sleep-wake regulation.

Experimental Procedures

Fly Strains

Drosophila melanogaster were reared on standard cornmeal/agar medium supplemented with yeast and kept in 12:12 light-dark (LD) cycles at 25°C. The yw; pdf-GAL4, yw, UAS-mCD8-GFP; Pdf-GAL4 and yw; Pdf-Gal4, UAS- mCD8-GFP were previously described (Nagoshi et al., 2010; Rodriguez Moncalvo and Campos, 2005). UAS-Mef2RNAi (transformant ID 15550) was previously described (Bryantsev et al., 2012; Chen et al., 2012) and obtained from the Vienna Drosophila RNAi Center. The UAS-Mef2 line expressing high levels of Mef2 isoform C was previously described (Blanchard et al., 2010; Bour et al., 1995). The UAS- Fas2RNAi line (stock # 28990) and UAS-ClkRNAi line (stock # 36661) were obtained from the Bloomington Stock Center. The UAS-TrpA1 line was previously described (Hamada et al., 2008; Parisky et al., 2008). UAS – Fas2 was obtained from Vivian Budnik. UAS-mCherry was obtained from Griffith lab.

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP) and Tiling Arrays

Chromatin was prepared from adult fly heads of yw flies entrained for 3 days in12:12 light:dark cycles and then harvested every 4 hours for a total of 6 timepoints. ChIP with anti-Mef2 antibody (Sandmann et al., 2007) was performed as described (Abruzzi et al., 2011; Menet et al., 2010) with the exception that 3ul of anti-Mef2 antibody was used per 125 μl chromatin. Briefly, nuclei were isolated from 1ml of fly heads for each time point, 25 μl of sonicated chromatin was removed for the input sample, and the remaining 125μl of chromatin was incubated with 3μl of anti-Mef2 antibody and purified with Protein G-Sepharose beads (Zymed). To control for non-specific binding, rabbit IgG (Sigma) was incubated with chromatin instead of Mef2 antibody. DNA was isolated with using a PCR purification kit (Qiagen). q-PCR for a known Mef2 binding locus, the Mef2 gene regulatory region (see Table S2) was used to validate the ChIP (Fig. S3B). ChIP samples were amplified to generate the probes for GeneChip Drosophila Tiling Array 2.0 (Affymetrix) according to manufacturer's instructions. q–PCR was used to verify that the enrichment in the IP sample was maintained through the amplification process. One tiling array was done for each timepoint with the exception of ZT18 which was done in duplicate. The arrays were hybridized, washed, and scanned according to the Affymetrix recommendations. Peaks identified via ChIP-Chip were then verified by performing q-PCR on three independent ChIP samples (see Table S2 for primers).

Model-based analysis of tiling arrays (MAT) algorithm(Johnson et al., 2006), Fourier analysis and automatic gene assignment was performed as in (Menet et al., 2010) and (Abruzzi et al., 2011). Peaks with F24 ≥ 0.5 and p-value less than 0.05 were considered to be cycling. To visualize Mef2 binding, the Integrated Genome Browser (IGB; Affymetrix) was used. In addition, the 450 top Mef2 peaks were visually mapped as previously described ((Abruzzi et al., 2011)), rendering a list of 342 peaks that we were able to assign to a single gene (Table S1). Gene ontology analysis of the resulting gene list was performed by GoToolbox software (Table 1).

q- PCR to validate Mef2 peaks

For q–PCR analysis of Mef2 binding, amplified chromatin (both input and IP) from 3 independent ChIP experiments was diluted to 2ng/μl and used as a template for q-PCR. To determine the fold binding above background, the IP signal was first normalized relative to the input sample (IP/Input). Then the IP/Input value of a region of interest was compared to the IP/Input of a region known not to bind Mef2 ((Sandmann et al., 2006) and Table S2).

Analysis of axonal morphology by modified Sholl's method

The following fly genotypes were used: yw, UAS- mCD8 GFP; Pdf –Gal4/+ (control); yw, UAS-mCD8 GFP; Pdf-Gal4/+; UAS-Mef2RNAi /+, and yw, UAS-mCD8 GFP; Pdf-Gal4/+; UAS-Mef2/+. For the analysis of the effect of Clk RNAi knockdown and the genetic rescue by Mef2, yw; Pdf-Gal4, UAS-mCD8 GFP /+; UAS-ClkRNAi /+ and yw; Pdf-Gal4, UAS-mCD8 GFP /+; UAS-ClkRNAi /UAS-Mef2 flies were assayed, and a yw; Pdf-Gal4, UAS- mCD8 GFP line was used as a control (data not shown). yw; Pdf-Gal4, UAS-mCD8 GFP /+; UAS-Fas2/+, yw; Pdf-Gal4, UAS-mCD8 GFP /+; UAS-Fas2/UAS-Mef2, yw; Pdf-Gal4, UAS-mCD8 GFP /+; UAS-Fas2RNAi /+, and yw; Pdf-Gal4, UAS-mCD8 GFP /+; UAS-Mef2RNAi /UAS-Fas2RNAi /+ flies were used to study epistatic relationship between Mef2 and its putative targets Fas2. Brains of 3-7 day old adult flies, entrained for 3 days at 12h:12h light/dark cycle at 25° C, were dissected, fixed in 4% PFA on ice for 30 minutes, briefly washed in PBS and mounted in Vectashield Mounting Medium (Vector Laboratories, CA) before imaging. Analysis of axonal morphology in constant darkness was performed on the second day after switching to DD (DD2). For the analysis of activity-dependent changes in axonal morphology, yw; Pdf-Gal4, UAS-mCD8GFP /UAS-TrpA1 and yw; Pdf-Gal4, UAS-mCD8GFP /UAS-TrpA1; UAS-Mef2RNAi /+ flies were entrained for 3 days using a 12h:12h light/dark cycle at 21° C and collected for dissection at ZT14 immediately after a 2 hour temperature elevation to 29° C. Imaging was performed with a Leica TCS SP2 confocal microscope using a 20x objective and a 4x digital zoom. Axons were traced using the Simple Neurite Tracer plugin for Fiji software (Longair et al., 2011). Quantitative analysis was performed with Image J 1.40 from NHI, Bethesda, MD, USA (http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/). Axons of all s-LNv neurons in each brain hemisphere were analyzed as a group (Fernandez et al., 2008). For the Sholl's analysis, 15 concentric circles spaced 10μm apart were centered on the point where dorsal ramification opens. Total number of intersections between axon branches and the concentric circles was computed using Sholl Analysis Plugin for ImageJ (Ghosh Lab, UCSD). We have also modified this plugin to additionally detect a 15 degree cone containing most of the intersections and to compute the fraction of the intersections outside of that “main projection direction” cone. Nearly identical results were seen when brains were stained with anti-GFP antibody using a standard immunohistochemistry protocol.

Immunohistochemistry

Immunostaining was performed as previously described (Tang et al., 2010). Briefly, fly heads were removed, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 45 min at 4°C and brains were dissected in PBS. Brains were blocked in 10% normal goat serum (Jackson Immunoresearch, PA) and subsequently incubated with primary antibodies at 4°C for 48 hours. Primary antibodies and their dilutions used were as follows: rabbit anti-GFP at 1:500 (Invitrogen), mouse anti-mCherry at 1:100 (Clontech), and mouse anti-PDF at 1:10 (from Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, University of Iowa). For detection of primary antisera, Alexa goat anti-rabbit 488, Alexa goat anti-mouse 488 and Alexa goat anti-mouse 633 (Invitrogen) were used at a dilution of 1:200. Brains were mounted in Vectashield Mounting Medium (Vector Laboratories, CA).

Locomotor behavior

Locomotor rhythms of individual male flies were monitored for 4 d in LD conditions (12 h light: 12 h dark intervals) followed by 4–9 d in DD conditions (constant darkness) using Trikinetics Drosophila Activity Monitors. Analyses of period length and rhythmic strength (assessed by by rhythmicity index (RI) (Levine et al., 2002)) were performed with Matlab-based software (Donelson et al., 2012). Flies with a rhythmicity index (RI) value >0.15 were considered rhythmic, with RI=0.1-0.15 weakly rhythmic, and with RI<0.1 arrhythmic. Experiments were performed at least 3 times with very similar results.

Gene expression analysis of the manually sorted PDF cells from Drosophila brains

Cell sorting, RNA isolation and preparation were performed as previously described (Kula-Eversole et al., 2010; Nagoshi et al., 2010). Briefly yw;Pdf-GAL4> UAS-mcd8 GFP and yw; Pdf-GAL4>UAS-mcd8GFP/UAS-Mef2 flies were entrained in 12 h light:12 h dark (LD) for at least 3 d and collected at ZT12, brains were dissected in ice-cold modified dissecting saline 50 μM D(–)-2-amino-5-phosphonovaleric acid (AP5), 20 μM 6,7-dinitroquinoxaline-2,3-dione (DNQX), 0.1 μM tetrodotoxin (TTX), and immediately transferred them into modified SMactive medium containing 5 mM Bis-Tris, 50 μM AP5, 20 μM DNQX, 0.1 μM TTX). About 100 adult brains were dissected for each of 2 independent experiments. Brains were digested with L-cysteine-activated papain (50 units ml–1 in dissecting saline; Worthington) 20 min at 25 °C, dissociated by trituration with a flame-rounded pipette tips, and the resulting cell suspension was diluted with ice-cold medium and transferred to Sylgard covered Petri dishes. GFP-positive cells were manually sorted under a fluorescence-dissecting microscope, yielding about 100 fluorescent cells per experiment. RNA was extracted with PicoPure RNA isolation Kit (Arcturus), amplified by two-cycle linear amplification as previously described (Kula-Eversole et al., 2010; Nagoshi et al., 2010), and analyzed by qRT-PCR. mRNA values for Fas2 were normalized to that of RPL32 (see table S2 for primer sequences).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Eileen Furlong for the generous gift of anti-Mef2 antibody. We also thank Leslie Griffith, Ravi Allada, Patrick Emery, Sebastian Kadaner, Maria Paz Fernandez and Emi Nagoshi for their helpful comments on the manuscript, and Kristyna Palm Danish for administrative assistance.

Footnotes

Data Availability: Affymetrix microarray data for the ChIP-Chip experiments will be available at Gene Expression Omnibus (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/), accession number GSE46576.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Abruzzi KC, Rodriguez J, Menet JS, Desrochers J, Zadina A, Luo W, Tkachev S, Rosbash M. Drosophila CLOCK target gene characterization: implications for circadian tissue-specific gene expression. Genes Dev. 2011;25:2374–2386. doi: 10.1101/gad.178079.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Appelbaum L, Wang G, Yokogawa T, Skariah GM, Smith SJ, Mourrain P, Mignot E. Circadian and homeostatic regulation of structural synaptic plasticity in hypocretin neurons. Neuron. 2010;68:87–98. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbosa AC, Kim MS, Ertunc M, Adachi M, Nelson ED, McAnally J, Richardson JA, Kavalali ET, Monteggia LM, Bassel-Duby R, et al. MEF2C, a transcription factor that facilitates learning and memory by negative regulation of synapse numbers and function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:9391–9396. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802679105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behrens UD, Wagner HJ. Adaptation-dependent changes of bipolar cell terminals in fish retina: effects on overall morphology and spinule formation in Ma and Mb cells. Vision Res. 1996;36:3901–3911. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6989(96)00139-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black BL, Molkentin JD, Olson EN. Multiple roles for the MyoD basic region in transmission of transcriptional activation signals and interaction with MEF2. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:69–77. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.1.69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanchard FJ, Collins B, Cyran SA, Hancock DH, Taylor MV, Blau J. The transcription factor Mef2 is required for normal circadian behavior in Drosophila. J Neurosci. 2010;30:5855–5865. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2688-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bour BA, O'Brien MA, Lockwood WL, Goldstein ES, Bodmer R, Taghert PH, Abmayr SM, Nguyen HT. Drosophila MEF2, a transcription factor that is essential for myogenesis. Genes Dev. 1995;9:730–741. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.6.730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryantsev AL, Baker PW, Lovato TL, Jaramillo MS, Cripps RM. Differential requirements for Myocyte Enhancer Factor-2 during adult myogenesis in Drosophila. Dev Biol. 2012;361:191–207. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2011.09.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bushey D, Cirelli C. From genetics to structure to function: exploring sleep in Drosophila. International review of neurobiology. 2011;99:213–244. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-387003-2.00009-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bushey D, Tononi G, Cirelli C. Sleep and synaptic homeostasis: structural evidence in Drosophila. Science. 2011;332:1576–1581. doi: 10.1126/science.1202839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao G, Nitabach MN. Circadian control of membrane excitability in Drosophila melanogaster lateral ventral clock neurons. J Neurosci. 2008;28:6493–6501. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1503-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ceriani MF, Hogenesch JB, Yanovsky M, Panda S, Straume M, Kay SA. Genome-wide expression analysis in Drosophila reveals genes controlling circadian behavior. J Neurosci. 2002;22:9305–9319. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-21-09305.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen SX, Cherry A, Tari PK, Podgorski K, Kwong YK, Haas K. The transcription factor MEF2 directs developmental visually driven functional and structural metaplasticity. Cell. 2012;151:41–55. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole CJ, Mercaldo V, Restivo L, Yiu AP, Sekeres MJ, Han JH, Vetere G, Pekar T, Ross PJ, Neve RL, et al. MEF2 negatively regulates learning-induced structural plasticity and memory formation. Nat Neurosci. 2012;15:1255–1264. doi: 10.1038/nn.3189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Depetris-Chauvin A, Berni J, Aranovich EJ, Muraro NI, Beckwith EJ, Ceriani MF. Adult-Specific Electrical Silencing of Pacemaker Neurons Uncouples Molecular Clock from Circadian Outputs. Curr Biol. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2011.09.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donelson N, Kim EZ, Slawson JB, Vecsey CG, Huber R, Griffith LC. High-resolution positional tracking for long-term analysis of Drosophila sleep and locomotion using the “tracker” program. PLoS One. 2012;7:e37250. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0037250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez MP, Berni J, Ceriani MF. Circadian remodeling of neuronal circuits involved in rhythmic behavior. PLoS Biol. 2008;6:e69. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiore R, Khudayberdiev S, Christensen M, Siegel G, Flavell SW, Kim TK, Greenberg ME, Schratt G. Mef2-mediated transcription of the miR379-410 cluster regulates activity-dependent dendritogenesis by fine-tuning Pumilio2 protein levels. EMBO J. 2009;28:697–710. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flavell SW, Cowan CW, Kim TK, Greer PL, Lin Y, Paradis S, Griffith EC, Hu LS, Chen C, Greenberg ME. Activity-dependent regulation of MEF2 transcription factors suppresses excitatory synapse number. Science. 2006;311:1008–1012. doi: 10.1126/science.1122511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flavell SW, Kim TK, Gray JM, Harmin DA, Hemberg M, Hong EJ, Markenscoff-Papadimitriou E, Bear DM, Greenberg ME. Genome-wide analysis of MEF2 transcriptional program reveals synaptic target genes and neuronal activity-dependent polyadenylation site selection. Neuron. 2008;60:1022–1038. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.11.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greer PL, Greenberg ME. From synapse to nucleus: calcium-dependent gene transcription in the control of synapse development and function. Neuron. 2008;59:846–860. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamada FN, Rosenzweig M, Kang K, Pulver SR, Ghezzi A, Jegla TJ, Garrity PA. An internal thermal sensor controlling temperature preference in Drosophila. Nature. 2008;454:217–220. doi: 10.1038/nature07001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson WE, Li W, Meyer CA, Gottardo R, Carroll JS, Brown M, Liu XS. Model-based analysis of tiling-arrays for ChIP-chip. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:12457–12462. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601180103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Junion G, Jagla T, Duplant S, Tapin R, Da Ponte JP, Jagla K. Mapping Dmef2-binding regulatory modules by using a ChIP-enriched in silico targets approach. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:18479–18484. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507030102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kula-Eversole E, Nagoshi E, Shang Y, Rodriguez J, Allada R, Rosbash M. Surprising gene expression patterns within and between PDF-containing circadian neurons in Drosophila. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:13497–13502. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1002081107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La Vail MM. Survival of some photoreceptor cells in albino rats following long-term exposure to continuous light. Invest Ophthalmol. 1976;15:64–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee T, Luo L. Mosaic analysis with a repressible cell marker for studies of gene function in neuronal morphogenesis. Neuron. 1999;22:451–461. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80701-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine JD, Funes P, Dowse HB, Hall JC. Signal analysis of behavioral and molecular cycles. BMC Neurosci. 2002;3:1. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-3-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Radford JC, Ragusa MJ, Shea KL, McKercher SR, Zaremba JD, Soussou W, Nie Z, Kang YJ, Nakanishi N, et al. Transcription factor MEF2C influences neural stem/progenitor cell differentiation and maturation in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:9397–9402. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802876105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Y, Stormo GD, Taghert PH. The neuropeptide pigment-dispersing factor coordinates pacemaker interactions in the Drosophila circadian system. J Neurosci. 2004;24:7951–7957. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2370-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longair MH, Baker DA, Armstrong JD. Simple Neurite Tracer: open source software for reconstruction, visualization and analysis of neuronal processes. Bioinformatics. 2011;27:2453–2454. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald MJ, Rosbash M. Microarray analysis and organization of circadian gene expression in Drosophila. Cell. 2001;107:567–578. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00545-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menet JS, Abruzzi KC, Desrochers J, Rodriguez J, Rosbash M. Dynamic PER repression mechanisms in the Drosophila circadian clock: from on-DNA to off-DNA. Genes Dev. 2010;24:358–367. doi: 10.1101/gad.1883910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller CM, Page-McCaw A, Broihier HT. Matrix metalloproteinases promote motor axon fasciculation in the Drosophila embryo. Development. 2008;135:95–109. doi: 10.1242/dev.011072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molkentin JD, Olson EN. Combinatorial control of muscle development by basic helix-loop-helix and MADS-box transcription factors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:9366–9373. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.18.9366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagoshi E, Sugino K, Kula E, Okazaki E, Tachibana T, Nelson S, Rosbash M. Dissecting differential gene expression within the circadian neuronal circuit of Drosophila. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13:60–68. doi: 10.1038/nn.2451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nitabach MN, Taghert PH. Organization of the Drosophila circadian control circuit. Curr Biol. 2008;18:R84–93. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.11.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nojima M, Huang Y, Tyagi M, Kao HY, Fujinaga K. The positive transcription elongation factor b is an essential cofactor for the activation of transcription by myocyte enhancer factor 2. J Mol Biol. 2008;382:275–287. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.07.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parisky KM, Agosto J, Pulver SR, Shang Y, Kuklin E, Hodge JJ, Kang K, Liu X, Garrity PA, Rosbash M, et al. PDF cells are a GABA-responsive wake-promoting component of the Drosophila sleep circuit. Neuron. 2008;60:672–682. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.10.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park JH, Helfrich-Forster C, Lee G, Liu L, Rosbash M, Hall JC. Differential regulation of circadian pacemaker output by separate clock genes in Drosophila. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:3608–3613. doi: 10.1073/pnas.070036197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potthoff MJ, Olson EN. MEF2: a central regulator of diverse developmental programs. Development. 2007;134:4131–4140. doi: 10.1242/dev.008367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pulipparacharuvil S, Renthal W, Hale CF, Taniguchi M, Xiao G, Kumar A, Russo SJ, Sikder D, Dewey CM, Davis MM, et al. Cocaine regulates MEF2 to control synaptic and behavioral plasticity. Neuron. 2008;59:621–633. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.06.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pyza E, Meinertzhagen IA. Monopolar cell axons in the first optic neuropil of the housefly, Musca domestica L., undergo daily fluctuations in diameter that have a circadian basis. J Neurosci. 1995;15:407–418. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-01-00407.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez Moncalvo VG, Campos AR. Genetic dissection of trophic interactions in the larval optic neuropil of Drosophila melanogaster. Dev Biol. 2005;286:549–558. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandmann T, Girardot C, Brehme M, Tongprasit W, Stolc V, Furlong EE. A core transcriptional network for early mesoderm development in Drosophila melanogaster. Genes Dev. 2007;21:436–449. doi: 10.1101/gad.1509007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandmann T, Jensen LJ, Jakobsen JS, Karzynski MM, Eichenlaub MP, Bork P, Furlong EE. A temporal map of transcription factor activity: mef2 directly regulates target genes at all stages of muscle development. Dev Cell. 2006;10:797–807. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shalizi A, Gaudilliere B, Yuan Z, Stegmuller J, Shirogane T, Ge Q, Tan Y, Schulman B, Harper JW, Bonni A. A calcium-regulated MEF2 sumoylation switch controls postsynaptic differentiation. Science. 2006;311:1012–1017. doi: 10.1126/science.1122513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang CH, Hinteregger E, Shang Y, Rosbash M. Light-mediated TIM degradation within Drosophila pacemaker neurons (s-LNvs) is neither necessary nor sufficient for delay zone phase shifts. Neuron. 2010;66:378–385. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.04.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tavosanis G. Dendritic structural plasticity. Dev Neurobiol. 2011 doi: 10.1002/dneu.20951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber P, Kula-Eversole E, Pyza E. Circadian control of dendrite morphology in the visual system of Drosophila melanogaster. PLoS One. 2009;4:e4290. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West AE, Greenberg ME. Neuronal activity-regulated gene transcription in synapse development and cognitive function. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2011;3 doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a005744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wijnen H, Naef F, Young MW. Molecular and statistical tools for circadian transcript profiling. Methods Enzymol. 2005;393:341–365. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(05)93015-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshii T, Wulbeck C, Sehadova H, Veleri S, Bichler D, Stanewsky R, Helfrich-Forster C. The neuropeptide pigment-dispersing factor adjusts period and phase of Drosophila's clock. J Neurosci. 2009;29:2597–2610. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5439-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu HH, Huang AS, Kolodkin AL. Semaphorin-1a acts in concert with the cell adhesion molecules fasciclin II and connectin to regulate axon fasciculation in Drosophila. Genetics. 2000;156:723–731. doi: 10.1093/genetics/156.2.723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.