Abstract

Bacterial type III protein secretion systems deliver effector proteins into eukaryotic cells in order to modulate cellular processes. Central to the function of these protein delivery machines is their ability to recognize and secrete substrates in a defined order. Here, we describe a mechanism by which a type III secretion system from the bacterial enteropathogen Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium can sort its substrates prior to secretion. This mechanism involves a cytoplasmic sorting platform that is sequentially loaded with the appropriate secreted proteins. The sequential loading of this platform, facilitated by customized chaperones, ensures the hierarchy in type III protein secretion. Given the presence of these machines in many important pathogens, these findings can serve as the bases for the development of novel antimicrobial strategies.

Bacterial pathogens have evolved the capacity to deliver effector proteins into target host eukaryotic cells (1). Various protein delivery machines have been described, including the so-called type III, type IV, and type VI secretion systems (2–5). Type III protein secretion systems (T3SS) are among the most complex protein secretion systems known (2, 5). The needle complex is a central component of these systems serving as a conduit for the secreted proteins as they pass through the bacterial envelope (6). Other essential elements of T3SSs are several cytoplasmic proteins of unknown function, and the so-called export apparatus. A group of proteins known as “translocases” facilitates the delivery of the effector proteins through the eukaryotic host cell membrane (7, 8). Protein secretion must be precisely coordinated to ensure first, the deployment of components of the needle complex, followed by the deployment of the protein translocases and the delivery of effector proteins (9–16). Interfering with the hierarchy of secretion results in loss of T3SS function (17).

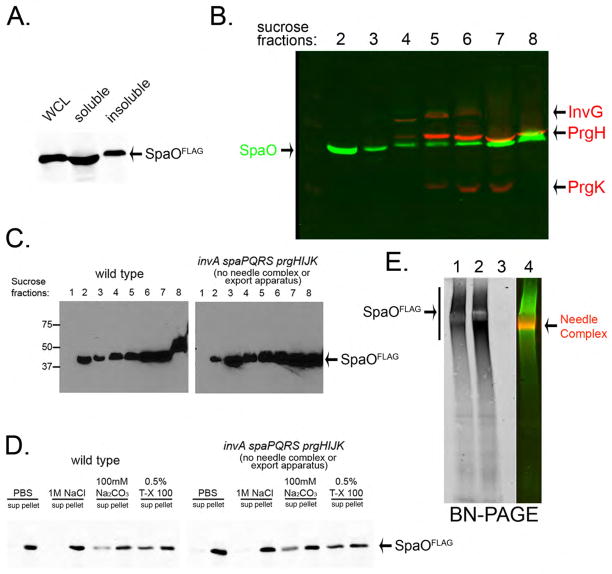

Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium (S. Typhimurium) encodes a T3SS, which mediates its interactions with the intestinal epithelium (18). We sought to investigate the function of cytoplasmic components of this T3SS, which are essential for its function. One of these proteins is SpaO (19), a conserved component of T3SSs that shares limited amino acid sequence similarity to components of a flagellar substructure known as the C ring (20, 21). We carried out a bacterial subcellular fractionation to localize SpaO (22) and found a substantial proportion (~20%) in high-speed centrifugation pellets of total cell lysates (Fig. 1A), with a significant amount of SpaO present in the same sucrose gradient fractions as the needle complex (Fig. 1B). However, a substantial proportion of SpaO was also detected in fractions that did not contain the needle complex (Fig. 1B). Furthermore, the subcellular localization of SpaO did not significantly change in a mutant strain lacking the needle complex and membrane protein components of the export apparatus (Fig. 1C), and significant amounts of SpaO remained pelletable even after treatment with a detergent concentration that should solubilize membranes (Fig. 1D). Thus SpaO appears to form a large molecular weight complex even in the absence of all the bacterial envelope components of the T3SSs. To further characterize the SpaO complex we used blue native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (BN-PAGE) (23). SpaO formed a large heterogeneous complex whose size did not change significantly in the absence of the needle complex or the membrane protein components of the export apparatus (Fig. 1E).

Fig. 1. SpaO forms a large molecular weight complex.

(A, B) Subcellular fractionation of SpaO (A) A whole cell lysate (WCL) of a S. Typhimurium strain expressing FLAG-epitope-tagged SpaO was separated into soluble and pelletable fractions by high-speed centrifugation and the presence of SpaO in the different fractions was probed by immuno blotting with an anti FLAG antibody. (B) The pellet fraction was subsequently separated by sucrose gradient centrifugation and the different gradient fractions were probed for the presence of SpaO (green) and needle complex components (red) by immuno blotting and imaging with the Odyssey system (Li-Cor Bioscience). (C) Comparison of the distribution of SpaO in wild type and the ΔinvA ΔspaPQRS ΔprgHIJK isogenic mutant derivative, which lacks the needle complex and membrane protein components of the export apparatus. The distribution of SpaO in the different fractions of a sucrose gradient was probed as indicated above. (D) Localization of SpaO after different treatments. Pellet fractions of SpaO obtained from the indicated strains were subjected to different treatments (as indicated) and its localization of high-speed centrifugation was determined by immuno blot analysis of the pellet and soluble fractions. (E) Analysis of the SpaO complex by BN-PAGE. Pellet fractions from a wild-type S. Typhimurium encoding a FLAG-epitope-tagged SpaO (1), a ΔinvA ΔspaPQRS ΔprgHIJK mutant derivative (2), or the untagged wild-type strain (3) were separated by BN-PAGE and analyzed by immuno blot for the presence of SpaO or the needle complex. The simultaneous detection of the SpaO (green) and needle complexes (red) from the sample shown on lane 1 is shown in lane 4. Only the SpaO channel is shown in lanes 1, 2, and 3.

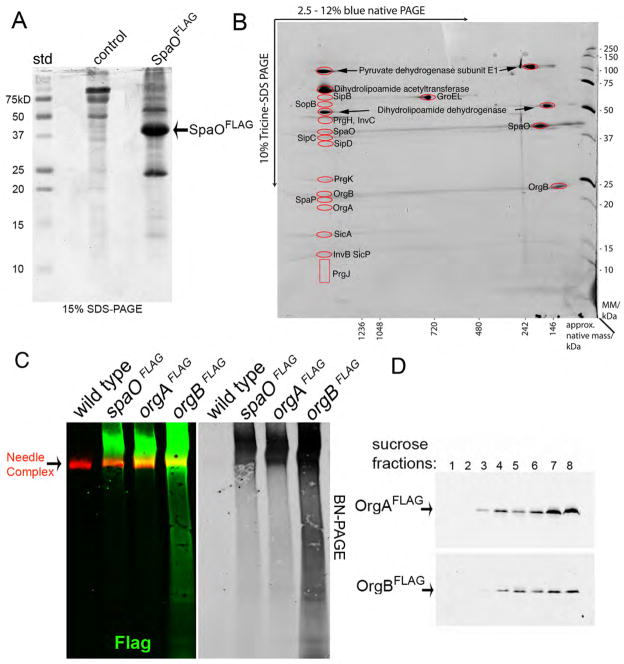

To identify components of the SpaO complex we immunoprecipitated SpaO from whole cell lysates or sucrose gradient fractions, which should only contain SpaO associated with the large molecular weight complex. Immunoprecipitated proteins were identified by liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) after one dimensional sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) (Fig. 2A, and Fig. S1) or two dimensional BN-PAGE (Fig. 2B and Fig. S2). We detected several T3SS-related proteins including components of the needle complex and export apparatus, the cytoplasmic proteins OrgA, OrgB and InvC, as well as the protein translocases SipB, SipC and SipD. OrgA and OrgB were also found to be part of a large molecular weight complex of a similar size to that of the SpaO complex (Fig. 2C and 2D). A preparation from cells lacking OrgA and OrgB showed a reduced amount of SpaO in the high molecular weight complex suggesting that these proteins may be required for the efficient assembly and/or stability of the SpaO complex (Fig. S3). Absence of the ATPase InvC, on the other hand, had no effect on the levels of SpaO in the high molecular weight complex (Fig. S3). Thus, the cytoplasmic proteins SpaO, OrgA, and OrgB form part of a large molecular weight multiprotein complex that can include components of the needle complex and export apparatus.

Figure 2. Characterization of the SpaO complex.

(A) and (B) Cell lysates of wild-type S. Typhimurium or an isogenic strain expressing FLAG-epitope tagged SpaO were immunoprecipitated with an anti FLAG antibody, separated by SDS-PAGE (A) and interacting proteins were identified by LC-MS/MS (see Fig. S1). Alternatively, the pelletable fraction of a cell lysates from a S. Typhimurium expressing FLAG-epitope tagged SpaO was separated on a sucrose density gradient, SpaO-containing fractions were pooled and SpaO-interacting proteins were immunoprecipitated with an anti-FLAG antibody, separated by 2D-BN-PAGE (B), and the identity of the proteins in the indicated spots (red circles) was established by LC-MS/MS (see Fig. S2). (C) Whole cell lysate of a S. Typhimurium strain expressing functional FLAG-epitope tagged SpaO, OrgA, or OrgB were separated into soluble and pelletable fractions by high-speed centrifugation. Pellet fractions were subsequently applied to a sucrose gradient, relevant fractions pulled, separated by BN-PAGE, and analyzed by immuno blot for the presence of SpaO, OrgA, or OrgB (green) or the needle complex (red). The simultaneous detection of the needle complex and SpaO, OrgA, or OrgB is shown in the color panel while only the detection of SpaO, OrgA, or OrgB is shown on the right (black and white) panel. (D) Subcellular fractionation of OrgA and OrgB. A whole cell lysate of a S. Typhimurium strain expressing FLAG-epitope-tagged OrgA or OrgB were separated into soluble and pelletable fractions by high-speed centrifugation. The pellet fractions were subsequently separated by sucrose gradient centrifugation and the different gradient fractions were probed for the presence of OrgA or OrgB by immuno blotting.

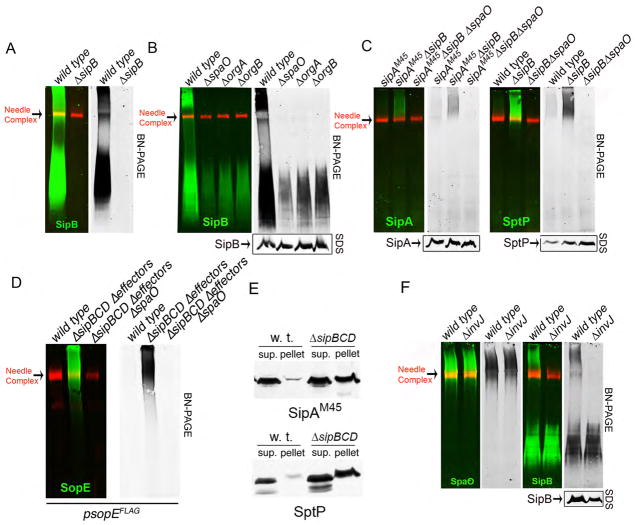

The bacterial translocases SipB, SipC and SipD were also readily detected in SpaO immunoprecipitates (Fig. 2A, 2B, Fig. S1 and Fig. S2), and SipB was present in a complex of similar size to that of the SpaO/OrgA/OrgB complex (Fig. 3A). The SipB high molecular weight complex was absent from strains lacking SpaO, OrgA, or OrgB (Fig. 3B). The S. Typhimurium T3SS is activated upon contact with mammalian cells (16, 24), which results in the stimulation of secretion and the delivery of proteins into target cells. The T3SS of bacteria grown under conditions that stimulate its expression is largely “idle” although it is fully assembled, “poised” and ready for secretion upon contact with target cells (25). The presence of the protein translocases (which must be secreted before the effectors) in the SpaO/OrgA/OrgB complex coupled to the observation that most effector proteins were largely absent, suggested that this complex might serve as a sorting platform to “queue” the secreted proteins for sequential orderly delivery. If this were the case, absence of the protein translocases would resemble an “activated” system that has deployed the translocases and effector proteins should be loaded onto the “sorting platform”. We tested this hypothesis by examining the presence of effector proteins in the SpaO/OrgA/OrgB complex in the absence of protein translocases. BN-PAGE of samples isolated from a translocase-defective S. Typhimurium mutant showed much higher levels of the effector protein SipA and SptP in the high molecular weight complex when compared to wild type (Fig. 3C). In fact, expression of the effector protein SopE in a background strain lacking all the translocases and effectors resulted in higher level of SopE in the high molecular weight complex when compared to wild type (Fig. 3D). Detection of these effector proteins in a high molecular weight complex was dependent on SpaO (Fig. 3C and Fig. 3D). Furthermore, the proportion of effector proteins present in high-speed centrifugation pellet fractions increased significantly in the ΔsipBCD mutant strain (Fig. 3E), which is consistent with their increased loading onto the SpaO/OrgA/OrgB platform in the absence of the translocases. Thus, in the absence of the translocases, effector proteins were able to associate with the SpaO/OrgA/OrgB platform.

Figure 3. The SpaO/OrgA/OrgB platform can be alternatively loaded with different substrates of the type III secretion system.

(A and B) Whole cell lysates of wild-type S. Typhimurium or the ΔsipB, ΔspaO, ΔorgA or ΔorgB mutants were separated into soluble and pelletable fractions by high-speed centrifugation. Pellets were further fractionated by sucrose gradient centrifugation, relevant fraction pooled, separated by BN-PAGE, and analyzed by immuno blot for the presence of SipB (green) or the needle complex (red). Left panels show the simultaneous detection of SipB and the needle complex and right (black and white) panels show only the detection of SipB. The lower panel shows SDS-PAGE immuno-blot analysis of SipB in equal amounts of whole cell lysates of the indicated strains. (C) (D) and (E) Samples from the indicated strains were separated into soluble (sup) and pelletable (pellet) fractions by high-speed centrifugation and separated by SDS-PAGE (E). Alternatively, the pellet fraction was further separated on a sucrose gradient, and the relevant fractions pooled and separated by BN-PAGE (C) and (D). Left panels in (C) and (D) show the simultaneous detection of SipA, SptP, (C), or SopE (D) (green) and the needle complexes (red) and right (black and white) panels show only the channel corresponding to the detection of the respective effector proteins. Lower panels show SDS-PAGE immuno-blot analysis of the indicated proteins in equal amounts of whole cell lysates of the indicated strains (C) and (D). (F) Samples from wild-type S. Typhimurium or a Δ invJ mutant expressing a FLAG-tagged SpaO were prepared as indicated above and separated by BN-PAGE. The left panels show the simultaneous detection of SpaO or SipB (green) and the needle complexes (red) and the right (black and white) panels shows only the channel corresponding to the detection of SpaO or SipB. The lower panel shows SDS-PAGE immuno-blot analysis of SipB in equal amounts of whole cell lysates of the indicated strains.

SpaO, OrgA, and OrgB are also required for the secretion of the proteins that make up the needle and the rod substructure of the needle complex (26), as well as the regulatory protein InvJ (10). In the absence of InvJ, the secretion apparatus is locked in a mode that constitutively secretes the needle and inner rod proteins (but not the translocases) (11). We reasoned that in the absence of InvJ, the SpaO/OrgA/OrgB platform should not be loaded with the protein translocases because, in the absence of substrate switching, the translocases would not be “poised” for secretion. Indeed, high molecular weight complexes obtained from a S. Typhimurium Δ invJ mutant lacked the protein translocase SipB (Fig. 3F) although the formation of the SpaO high molecular weight complex was unaffected (Fig. 3F). Thus the SpaO/OrgA/OrgB complex serves as a sorting platform that establishes the appropriate hierarchy in the secretion process.

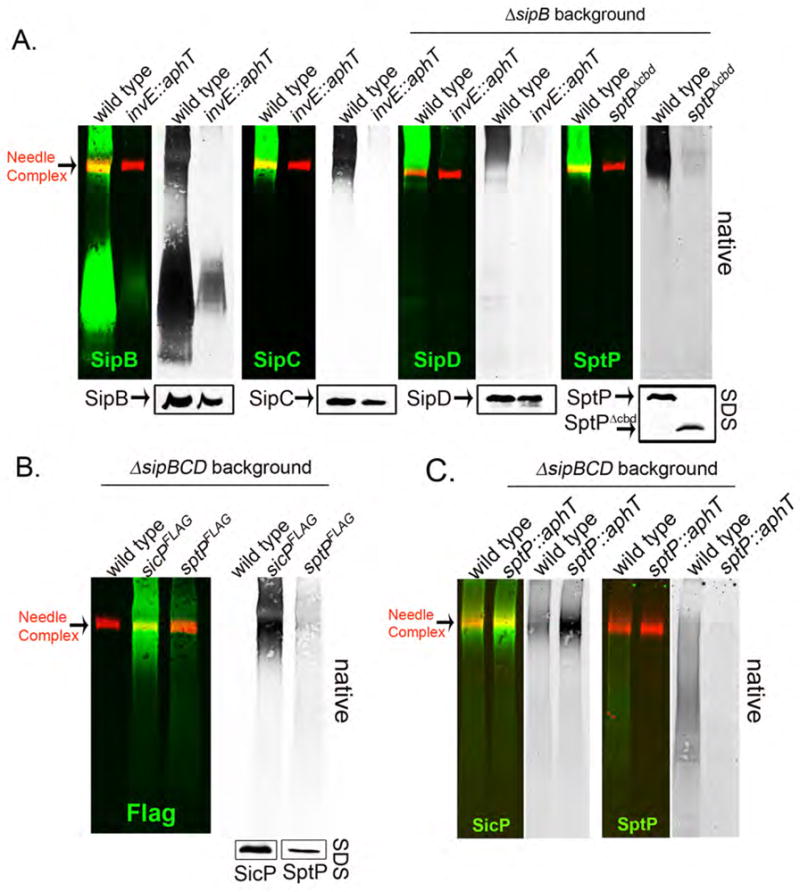

We next investigated the mechanisms by which the SpaO/OrgA/OrgB sorting platform is loaded with the appropriate substrates. Most proteins destined to travel the type III secretion pathway are associated to customized cytoplasmic chaperones, which are necessary for their secretion and in some cases their stability within the bacterial cytoplasm (27, 28). We tested the potential role of the T3SS-associated chaperones in the recruitment of effectors or translocases to the SpaO/OrgA/OrgB platform. The protein translocases are chaperoned by two proteins, SicA and InvE (17, 29). In the absence of InvE, the translocases SipB, SipC, or SipD were absent from the SpaO/OrgA/OrgB platform although their total levels in whole cell lysates were unchanged (Fig. 4A). Similarly, removal of the chaperone-binding site of SptP prevented its recruitment to the SpaO/OrgA/OrgB platform (Fig. 4A), despite the fact that the level of this effector protein mutant in whole cell lysates was also unchanged in comparison to wild type SptP (Fig. 4A). Thus the chaperones are required for the targeting of the type III secreted proteins to the SpaO/OrgA/OrgB sorting platform. Immediately prior to secretion, T3SS chaperones are removed from their cognate secreted proteins and remain in the bacterial cytoplasm. We looked for SicP, the chaperone of SptP, in the SpaO/OrgA/OrgB platform of a ΔsipBCD mutant strain (which can be loaded with SptP, see above). SicP was readily detected in this platform (Fig. 4B) indicating that chaperone removal may not occur upon loading of the SpaO/OrgA/OrgB sorting complex but at a later stage in the secretion process. Furthermore, we detected SicP in the SpaO/OrgA/OrgB complex of a ΔsptP S. Typhimurium mutant strain, which lacks this chaperone’s cognate secreted protein SptP (Fig. 4C), indicating that recognition of the chaperone/effector complex by the sorting platform may occur through interactions with the chaperone itself.

Fig. 4. The type III secretion chaperones are required for the loading of translocases and effector protein onto the SpaO/OrgA/OrgB platform.

(A) Samples from the wild-type S. Typhimurium, a mutant lacking the translocase-chaperone InvE, or a strain expressing a mutant of SptP lacking its chaperone-binding domain (SptPΔ35–161;indicated as SptPΔcbd) were prepared as indicated above and the presence of the translocases SipB, SipC and SipD and the effector protein SptP in the SpaO/OrgA/OrgB complex was examined by BN-PAGE and immuno blot analysis. A S. Typhimurium lacking SipB was used as a background strain for these experiments to enhance the detection of SipD or SptP. In all cases the left panel show the simultaneous detection of the indicated effector or translocase (green) and the needle complexes (red) and right (black and white) panels show only the channel corresponding to the detection of the respective effector or translocase proteins. Lower panels show SDS-PAGE immuno-blot analysis of the indicated proteins in equal amounts of whole cell lysates of the indicated strains. (B) Samples from wild-type S. Typhimurium, a strain expressing FLAG epitope tagged SicP, the chaperone for SptP, or a strain expressing FLAG-tagged SptP, were prepared as indicated above and separated by BN-PAGE. The left panel shows the simultaneous detection of SicPFLAG or SptPFLAG (green) and the needle complexes (red) and right (black and white) panel shows only the channel corresponding to the detection of SicPFLAG or SptPFLAG. The lower panels show SDS-PAGE immuno-blot analysis of the indicated proteins in equal amounts of whole cell lysates of the indicated strains. (C) Samples from the indicated strains were prepared as described above and separated by BN-PAGE. The left panel shows the simultaneous detection of SicPFLAG or SptP (green) and the needle complexes (red) and right (black and white) panels show only the channel corresponding to the detection of SicPFLAGor SptP.

A unique distinctive feature of T3SSs is their ability to engage substrates in a pre-established order (9–16). We have described here a sorting platform (Fig. S4) that ensures the secretion of the translocases prior to the effectors. This same platform may also contribute to substrate selection during the assembly of the needle complex although additional mechanisms are required to ensure substrate switching after termination of needle complex assembly (12, 30, 31). Because T3SS associated chaperones are essential for the loading of the sorting platform, the hierarchy of secretion may reflect different affinities of the different secreted protein-chaperone complexes for the sorting platform. The mechanism described here is likely to apply to all T3SSs because the components of the sorting platform and their interactions are conserved in other systems (Fig. S5-S7) (21, 32–35).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank members of the Galán laboratory for critical reading of this manuscript. M. L.-T. was supported by NIH Grant U54 AI0157158, and S. W. by a long-term fellowship of the International Human Frontiers Science Program. This work was supported by NIH Grant AI30492 to J. E. G.

References and Notes

- 1.Galan JE, Cossart P. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2005;8:1. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2004.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Galan JE, Wolf-Watz H. Nature. 2006;444:567. doi: 10.1038/nature05272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alvarez-Martinez C, Christie P. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2009;73:775. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00023-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pukatzki S, McAuley S, Miyata S. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2009;12:11. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2008.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cornelis G. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2006;4:811. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kubori T, et al. Science. 1998;280:602. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5363.602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hakansson S, et al. EMBO J. 1996;15:5812. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boland A, et al. EMBO J. 1996;15:5191. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Williams AW, et al. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:2960. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.10.2960-2970.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Collazo C, Galán JE. Infect Immun. 1996;64:3524. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.9.3524-3531.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kubori T, Sukhan A, Aizawa SI, Galán JE. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:10225. doi: 10.1073/pnas.170128997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Edqvist P, et al. J Bacteriol. 2003;185:2259. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.7.2259-2266.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Riordan KE, Sorg JA, Berube BJ, Schneewind O. J Bacteriol. 2008;190:6204. doi: 10.1128/JB.00467-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tamano K, Katayama E, Toyotome T, Sasakawa C. J Bacteriol. 2002;184:1244. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.5.1244-1252.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sorg J, Blaylock B, Schneewind O. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:16490. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605974103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lara-Tejero M, Galan JE. Infect Immun. 2009;77:2635. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00077-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kubori T, Galan JE. J Bacteriol. 2002;184:4699. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.17.4699-4708.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Galán JE. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2001;17:53. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.17.1.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Groisman EA, Ochman H. EMBO J. 1993;12:3779. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb06056.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Minamino T, Imada K, Namba K. Mol Biosyst. 2008;4:1105. doi: 10.1039/b808065h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morita-Ishihara T, et al. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:599. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M509644200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.See Supplementary Online Materials for experimental details.

- 23.Schägger H, von Jagow G. Anal Biochem. 1991;199:223. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(91)90094-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zierler MK, Galán JE. Infect Immun. 1995;63:4024. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.10.4024-4028.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Collazo C, Galán JE. Mol Microbiol. 1997;24:747. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.3781740.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sukhan A, Kubori T, Wilson J, Galán JE. J Bacteriol. 2001;183:1159. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.4.1159-1167.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Feldman M, Cornelis G. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2003;219:151. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1097(03)00042-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stebbins CE, Galán JE. Nature. 2001 Nov 1;414:77. doi: 10.1038/35102073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kaniga K, Tucker SC, Trollinger D, Galán JE. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:3965. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.14.3965-3971.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Journet L, Agrain C, Broz P, Cornelis GR. Science. 2003;302:1757. doi: 10.1126/science.1091422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marlovits TC, et al. Nature. 2006;441:637. doi: 10.1038/nature04822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.González-Pedrajo B, Minamino T, Kihara M, Namba K. Mol Microbiol. 2006;60:984. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05149.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jouihri N, et al. Mol Microbiol. 2003;49:783. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03590.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Johnson S, Blocker A. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2008;286:274. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2008.01284.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Spaeth K, Chen Y, Valdivia R. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000579. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.