Abstract

Introduction: Quality reporting was initially implemented to offer a better means of assessing hospitals and to provide patients with information to help them when choosing their hospital. Quality reports are published every 2 years and include parameters describing the hospitalʼs structure and general infrastructure together with specific data on individual specialised departments or clinics. Method: This study investigated the 2010 quality reports of German university hospitals published online, focussing on the following data: number of inpatients treated by the hospital, focus of care provided by the unit/department, range of medical services and care provided by the unit/department, non-medical services provided by the unit/department, number of cases treated in the unit/department, ICD diagnoses, OPS procedures, number of outpatient procedures, day surgeries as defined by Section 115b SGB V, presence of an accident insurance consultant and number of staff employed. Results: University gynaecology clinics (UGCs) treat 10 % (range: 6–17 %) of all inpatients of their respective university hospital. There were no important differences in infrastructure between clinics. All UGCs offered full medical care and were specialist clinics for gynaecology (surgery, breast centres, genital cancer, urogynaecology, endoscopy), obstetrics (prenatal diagnostics, high-risk obstetrics); many were also specialist clinics for endocrinology and reproductive medicine. On average, each clinic employs 32 physicians (range: 16–78). Half of them (30–77 %) are specialists. Around 171 (117–289) inpatients are treated on average per physician. The most common ICD coded treatments were deliveries and treatment of infants. Gynaecological diagnoses are underrepresented. Summary: UGCs treat 10 % of all inpatients treated in university hospitals, making them important ports of entry for their respective university hospital. Around half of the physicians are specialists. Quality reports offer little information on the differences in competencies or medical specialties. The statutory quality reports are not useful for patients and referring physicians when choosing a clinic.

Key words: gynaecology, obstetrics, reproductive medicine

Abstract

Zusammenfassung

Einleitung: Die Qualitätsberichte wurden konzipiert, um die Kompetenz der Kliniken besser darstellen zu können, sodass Patienten sich für die Auswahl der Klinik daran orientieren können. Sie werden alle 2 Jahre veröffentlicht und enthalten Parameter zu den Strukturen der Kliniken, der Infrastruktur insgesamt und spezifische Daten zu den einzelnen Fachabteilungen (Disziplinen). Methode: In dieser Arbeit wurden die im Internet veröffentlichten Qualitätsberichte des Jahres 2010 der Universitätskliniken untersucht und die folgenden Daten ausgewertet: Anzahl der stationären Patientinnen im Gesamtklinikum, Versorgungsschwerpunkte der Organisationseinheit/Fachabteilung, medizinisch-pflegerische Leistungsangebote der Organisationseinheit/Fachabteilung, nicht medizinische Serviceangebote der Organisationseinheit/Fachabteilung, Fallzahlen der Organisationseinheit/Fachabteilung, Diagnosen nach ICD, Prozeduren nach OPS, ambulante Behandlungsmöglichkeiten, ambulante Operationen nach § 115b SGB V, Zulassung zum Durchgangs-Arztverfahren der Berufsgenossenschaft und personelle Ausstattung. Ergebnisse: Die Universitäts-Frauenkliniken liefern 10 % (von 6 bis 17 %) der stationären Fälle der jeweiligen Universitätsklinika. Bei der Beschreibung der Infrastruktur gibt es keine relevanten Unterschiede. Alle UFKs decken das gesamte Spektrum des Faches ab und sind Schwerpunkte im Bereich der Gynäkologie (operativ, Brustzentrum, Genitalkarzinome, Urogynäkologie, Endoskopie), Geburtshilfe (Pränataldiagnostik, Risikogeburtshilfe) und die meisten auch im Bereich der Endokrinologie und Reproduktionsmedizin. Im Mittel werden ca. 32 Ärztinnen und Ärzte beschäftigt (16–78). Die Hälfte davon (30–77 %) sind Fachärztinnen und Fachärzte. Pro Arztstelle werden durchschnittlich 171 (117–289) Patientinnen stationär behandelt. Die meisten ICD-Schlüssel sind Entbindungen und Kinder. Gynäkologische Diagnosen sind unterrepräsentiert. Zusammenfassung: Die UFKs sind mit ca. 10 % der stationären Fälle der Universitätskliniken eine wichtige Eintrittspforte für das jeweilige Uniklinikum. Beinahe die Hälfte der Ärztinnen und Ärzte sind Fachärztinnen und Fachärzte. Kompetenzunterschiede und Schwerpunkte sind aus den Qualitätsberichten nur schwer bis gar nicht abzuleiten. Die gesetzlichen Qualitätsberichte sind für Patientinnen bei der Klinikwahl und für einweisende Ärztinnen und Ärzte bei der Beratung kaum nützlich.

Schlüsselwörter: Frauenheilkunde, Geburtshilfe, assistierte Reproduktion

Introduction

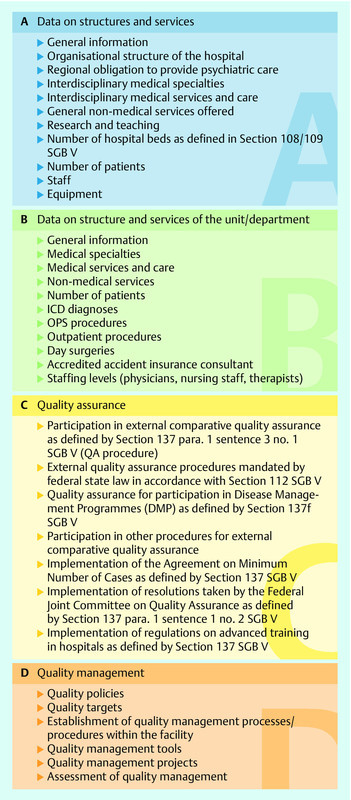

Quality reports are statutory reports as defined by Section 137 Book V of the SGB (Germany Social Welfare Code) which every hospital must publish every two years. Hospitals provide data based on certain pre-defined, standardised criteria. The structure of the quality reports is shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Structure of quality reports.

These publications are intended to offer patients standardised information on every hospital. Quality reports are structured according to specified requirements, making it easier to compare the structures of different hospitals/clinics. Part B of the quality report aims to provide information on individual specialist clinics/departments. Data include the number of inpatients treated, the infrastructure of the specialist clinic, the number of diagnoses and procedures performed listed in order of frequency (10 most common), and the levels of staffing.

Currently, quality reports are published every 2 years and their contents are updated. This platform aims to provide information about the respective hospital or clinic as well as more transparency. One important aspect of quality reports is that all hospitals are represented within the same framework, irrespective of whether they are primary or tertiary care facilities. Hospitals offering the same levels of care (primary, secondary, tertiary) can be compared to one another 1, 2, 3.

The disadvantage of the quality reports is that they focus on quantitative aspects. The reports do not reflect criteria on the quality of medical care.

Material and Method

This study investigated the 2010 quality reports for university hospitals published online.

The following data were assessed:

Number of inpatients treated in the university hospital (Part A)

Focus and level of care provided by the unit/department (Part B)

Medical services and care provided by the specialist department (Part B)

Non-medical services provided by the unit/department (Part B)

Number of cases treated in the unit/department (Part B)

ICD diagnoses (Part B)

OPS procedures performed (Part B)

Number of outpatient procedures (Part B)

Day surgery as defined in Section115b SGB V (Part B)

Accident insurance consultant present (Part B)

Staffing levels given as numbers of full-time employees (Part B)

In some cases where hospitals consisted of 2 or 3 clinics (at several speciality locations) the case numbers were simply added up.

University gynaecology clinics not affiliated to university hospitals were not included in this study. Such hospitals have a non-university infrastructure for patient care which makes it more difficult to compare them with university facilities.

The following questions were investigated:

How many inpatients were treated in the respective university hospitals?

Which quantitative differences exist between university gynaecology clinics with regard to inpatient care?

How important is gynaecology for the inpatient care of university hospitals?

What are the quantitative differences in staffing levels between university gynaecology clinics?

What information can be deduced from quality reports?

Results

1. How many inpatients are treated in the respective university hospitals?

Part A of the quality report listed the numbers of inpatients treated in the respective hospital and clinic. The number of patients are shown in Table 1. The average number of patients was 52 827 (range: 35 324 to 128 017). Six university hospitals (UHs) treated more than 60 000 patients annually (2 of which were spread over 2 and 3 locations, respectively), 10 UHs treated 50 000 to 60 000 patients, 14 UHs treated between 40 000 and 50 000, and 2 treated fewer than 40 000 patients per year.

Table 1 University hospitals (UH) and university gynaecological clinics (UGC) according to the number of inpatients (UGC and UH), day care patients and outpatients (UH). Sorted according to the ratio of UGC patients to UH patients given in percent.

| Clinic | No. of inpatients per UH | No. of day care patients per UH | No. of outpatients per UH | No. of inpatients per UGC | UGC/UH (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 43 759 | 0 | 11 039 | 2 729 | 6.24 |

| 28 | 47 323 | 6 656 | 240 060 | 2 979 | 6.30 |

| 7 | 53 774 | 337 | 0 | 3 517 | 6.54 |

| 10 | 45 020 | 2 168 | 155 997 | 2 960 | 6.57 |

| 11 | 48 213 | 2 243 | 181 816 | 3 434 | 7.12 |

| 12 | 35 324 | 1 002 | 112 000 | 2 774 | 7.85 |

| 26 | 57 032 | 19 643 | 208 947 | 4 732 | 8.30 |

| 16 | 61 116 | 9 800 | 413 135 | 5 092 | 8.33 |

| 9 | 62 751 | 4 587 | 257 491 | 5 370 | 8.56 |

| 17 | 51 621 | 1 306 | 206 224 | 4 482 | 8.68 |

| 24 | 47 095 | 4 434 | 94 305 | 4 098 | 8.70 |

| 13 | 38 486 | 1 850 | 90 449 | 3 653 | 9.49 |

| 4 | 53 926 | 5 997 | 309 487 | 5 163 | 9.57 |

| 25 | 61 420 | 5 836 | 238 381 | 5 929 | 9.65 |

| 19 | 46 779 | 456 | 168 260 | 4 516 | 9.65 |

| 30 | 51 406 | 7 022 | 211 741 | 5 040 | 9.80 |

| 3 | 46 447 | 458 | 325 248 | 4 593 | 9.89 |

| 18 | 52 895 | 4 260 | 362 321 | 5 301 | 10.02 |

| 23 | 48 657 | 484 | 125 827 | 4 889 | 10.05 |

| 32 | 53 489 | 5 418 | 152 916 | 5 449 | 10.19 |

| 20 | 49 451 | 2 548 | 173 509 | 5 051 | 10.21 |

| 8 | 46 439 | 1 891 | 219 480 | 4 766 | 10.26 |

| 15 | 54 875 | 1 790 | 370 373 | 5 822 | 10.61 |

| 27 | 43 085 | 971 | 144 075 | 4 839 | 11.23 |

| 2 | 128 017 | 0 | 592 566 | 15 148 | 11.83 |

| 14 | 53 606 | 1 882 | 182 358 | 6 346 | 11.84 |

| 5 | 43 213 | 1 107 | 192 603 | 5 362 | 12.41 |

| 21 | 48 721 | 2 981 | 278 562 | 6 113 | 12.55 |

| 6 | 58 248 | 9 885 | 387 794 | 7 387 | 12.68 |

| 22 | 76 797 | 8 615 | 378 930 | 11 950 | 15.56 |

| 31 | 45 883 | 3 464 | 216 311 | 7 508 | 16.36 |

| 29 | 60 320 | 2 581 | 327 581 | 10 486 | 17.38 |

2. Which quantitative differences exist between university gynaecology clinics with regard to inpatient care?

Part B of the quality reports showed the number of inpatients in the respective gynaecology clinic. The average number of inpatients treated in university gynaecology clinics was 5311 (range: 2729 to 15 148). When the number of inpatients was divided according to the number of hospital sites, the average number of patients treated per UGC site was 5073. Four university gynaecology clinics treated fewer than 3000 women and 5 treated more than 7000 inpatients per year. The other 23 UGCs treated between 3000 and 7000 women annually (3 UGCs treated between 3000 and 4000; 8 UGCs between 4000 and 5000; 10 UGCs between 5000 and 6000 and 2 between 6000 and 7000 women per year).

3. How important is gynaecology for the inpatient care of university hospitals?

The university gynaecology clinics treated an average of 10 % of all inpatients of their respective university hospital (between 6 and 17 %). Three UGCs treated more than 13 % and 6 UGCs treated less than 8 %.

4. What are the quantitative differences in staffing levels between university gynaecology clinics?

Table 2 shows the number of staff for the respective university gynaecology clinics. On average, UGCs employed around 32 physicians (between 16 and 78). The number of specialist physicians was around 16 per university gynaecology clinic (min. 8 to max. 36.5). This means that around 50 % of physicians employed were specialists (30 to 77 %). An average of 171 (117 to 289) inpatients were treated per physician.

Table 2 Physicians employed by UGCs.

| Clinic | No. of inpatients per UGC | No. of physicians | No. of specialists | Specialists/physicians | No. of inpatients per physician |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | 2 960 | 16.0 | 8.0 | 50.00 | 185.00 |

| 1 | 2 729 | 17.3 | 9.3 | 53.76 | 157.75 |

| 24 | 4 098 | 18.7 | 9.7 | 51.87 | 219.14 |

| 17 | 4 482 | 19.8 | 7.6 | 38.38 | 226.36 |

| 11 | 3 434 | 20.5 | 9.7 | 47.32 | 167.51 |

| 12 | 2 774 | 21.8 | 16.8 | 77.06 | 127.25 |

| 13 | 3 653 | 22.9 | 7.7 | 33.62 | 159.52 |

| 4 | 5 163 | 24.6 | 11.6 | 47.15 | 209.88 |

| 15 | 5 822 | 25.0 | 13.0 | 52.00 | 232.88 |

| 28 | 2 979 | 25.5 | 17.0 | 66.67 | 116.82 |

| 26 | 4 732 | 25.9 | 10.8 | 41.70 | 182.70 |

| 31 | 7 508 | 26.0 | 14.0 | 53.85 | 288.77 |

| 8 | 4 766 | 26.5 | 14.0 | 52.83 | 179.85 |

| 21 | 6 113 | 27.0 | 17.0 | 62.96 | 226.41 |

| 7 | 3 517 | 27.0 | 18.0 | 66.67 | 130.26 |

| 9 | 5 370 | 30.4 | 16.9 | 55.59 | 176.64 |

| 25 | 5 929 | 30.5 | 18.5 | 60.66 | 194.39 |

| 32 | 5 449 | 31.8 | 13.0 | 40.94 | 171.62 |

| 3 | 4 593 | 31.8 | 9.7 | 30.50 | 144.43 |

| 20 | 5 051 | 32.0 | 20.0 | 62.50 | 157.84 |

| 5 | 5 362 | 32.6 | 14.9 | 45.71 | 164.48 |

| 18 | 5 301 | 32.8 | 14.0 | 42.68 | 161.62 |

| 27 | 4 839 | 34.3 | 13.3 | 38.78 | 141.08 |

| 23 | 4 889 | 36.7 | 17.2 | 46.87 | 133.22 |

| 14 | 6 346 | 36.7 | 17.9 | 48.77 | 172.92 |

| 19 | 4 516 | 37.7 | 21.0 | 55.70 | 119.79 |

| 16 | 5 092 | 37.8 | 15.3 | 40.48 | 134.71 |

| 6 | 7 387 | 41.5 | 13.5 | 32.53 | 178.00 |

| 30 | 5 040 | 41.8 | 21.7 | 51.91 | 120.57 |

| 29 | 10 486 | 50.8 | 31.5 | 62.01 | 206.42 |

| 22 | 11 950 | 73.5 | 36.9 | 50.20 | 162.59 |

| 2 | 15 148 | 78.0 | 36.7 | 47.05 | 194.21 |

5. What information can be deduced from quality reports?

No relevant differences between UGCs were found with regard to the focus of care of the unit/department, the medical services and care offered by the unit/department, or the non-medical services provided by the unit/department.

The most common diagnoses and procedures are listed in Tables 3 and 4.

Table 3 The 10 most common diagnoses in each UGC.

| Kl. | D1 | N1 | D2 | N2 | D3 | N3 | D4 | N4 | D5 | N5 | D6 | N6 | D7 | N7 | D8 | N8 | D9 | N9 | D10 | N10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C50 Malignant neoplasm of breastC53 Malignant neoplasm of cervix uteri | ||||||||||||||||||||

| C54 Malignant neoplasm of corpus uteri | ||||||||||||||||||||

| C56 Malignant neoplasm of ovary | ||||||||||||||||||||

| D05 Carcinoma in situ of breast | ||||||||||||||||||||

| D25 Leiomyoma of uterus | ||||||||||||||||||||

| D27 Benign neoplasm of ovary | ||||||||||||||||||||

| N39 Other diseases of urinary system | ||||||||||||||||||||

| N80 Endometriosis | ||||||||||||||||||||

| N81 Female genital prolapse | ||||||||||||||||||||

| N83 Non-inflammatory disorders of ovary, fallopian tube and broad ligament | ||||||||||||||||||||

| O24 Diabetes mellitus in pregnancyO26 Maternal care for other conditions predominantly related to pregnancy | ||||||||||||||||||||

| O32 Maternal care for known or suspected malpresentation of foetus | ||||||||||||||||||||

| O34 Maternal care for known or suspected abnormality of pelvic organs | ||||||||||||||||||||

| O42 Premature rupture of membranes | ||||||||||||||||||||

| O48 Prolonged pregnancy | ||||||||||||||||||||

| O60 Preterm delivery | ||||||||||||||||||||

| O63 Long labour | ||||||||||||||||||||

| O64 Obstructed labour due to malposition and malpresentation of foetus | ||||||||||||||||||||

| O68 Labour and delivery complicated by foetal distress | ||||||||||||||||||||

| O70 Perineal laceration during delivery | ||||||||||||||||||||

| O71 Other obstetric trauma | ||||||||||||||||||||

| O75 Other complications of labour and delivery, not elsewhere classified | ||||||||||||||||||||

| O80 Single spontaneous delivery | ||||||||||||||||||||

| O81 Single delivery by forceps and vacuum extractor | ||||||||||||||||||||

| O82 Single delivery by caesarean section | ||||||||||||||||||||

| O99 Other maternal diseases classifiable elsewhere but complicating pregnancy, childbirth and the puerperium | ||||||||||||||||||||

| P05 Slow foetal growth and foetal malnutrition | ||||||||||||||||||||

| P07 Disorders related to short gestation and low birth weight, not elsewhere classified | ||||||||||||||||||||

| P08 Disorders related to long gestation and high birth weight | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Q65 Congenital deformities of hip | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Q66 Congenital deformities of feet | ||||||||||||||||||||

| P21 Birth asphyxia | ||||||||||||||||||||

| P22 Respiratory distress of newborn | ||||||||||||||||||||

| P24 Neonatal aspiration syndromes | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Z03 Medical observation and evaluation for suspected diseases and conditions | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Z13 Special screening examination for other diseases and disorders | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Z38 Mature liveborn infant | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 12 | C50 | 331 | D25 | 144 | O99 | 125 | O24 | 116 | O70 | 115 | O60 | 115 | C56 | 79 | C54 | 71 | D27 | 69 | O42 | 62 |

| 18 | O42 | 435 | O68 | 428 | O24 | 344 | O69 | 254 | O36 | 252 | O48 | 252 | O64 | 199 | O34 | 199 | O26 | 183 | O99 | 157 |

| 4 | O68 | 399 | Z38 | 393 | O42 | 391 | C50 | 347 | O60 | 302 | O34 | 214 | Q66 | 198 | O48 | 153 | O64 | 146 | P08 | 136 |

| 1 | Z38 | 492 | O60 | 175 | O34 | 171 | O36 | 117 | O42 | 99 | C50 | 94 | D25 | 82 | O48 | 68 | O99 | 65 | N83 | 47 |

| 2 | Z38 | 742 | O42 | 267 | O34 | 145 | O48 | 125 | O99 | 85 | O68 | 78 | O70 | 72 | O75 | 72 | O28 | 66 | O36 | 62 |

| 3 | Z38 | 927 | C50 | 245 | O70 | 219 | O36 | 188 | O34 | 178 | O42 | 171 | O35 | 162 | O60 | 147 | C56 | 125 | Q65 | 123 |

| 5 | Z38 | 1 319 | O70 | 330 | O34 | 255 | C50 | 229 | O68 | 170 | O42 | 160 | O63 | 160 | O80 | 151 | O64 | 131 | D25 | 128 |

| 6 | Z38 | 1 177 | C50 | 840 | O70 | 279 | D25 | 275 | O68 | 270 | O42 | 254 | N80 | 241 | C56 | 229 | D24 | 179 | O34 | 131 |

| 7 | Z38 | 617 | C50 | 305 | O70 | 165 | D25 | 140 | C56 | 119 | O68 | 108 | O34 | 104 | O60 | 101 | O65 | 89 | O26 | 86 |

| 8 | Z38 | 922 | C50 | 339 | O68 | 248 | O70 | 223 | O60 | 217 | O42 | 196 | O71 | 141 | P07 | 124 | P08 | 109 | O34 | 102 |

| 9 | Z38 | 548 | C50 | 314 | O34 | 283 | O68 | 207 | O70 | 196 | O24 | 191 | O99 | 154 | O60 | 137 | D25 | 106 | O42 | 87 |

| 10 | Z38 | 667 | O34 | 232 | O42 | 166 | D25 | 144 | O36 | 95 | O68 | 92 | O75 | 84 | O70 | 78 | C50 | 71 | O99 | 71 |

| 11 | Z38 | 459 | C50 | 400 | O34 | 194 | C53 | 143 | O42 | 141 | C56 | 128 | O99 | 121 | C54 | 77 | O36 | 71 | O71 | 70 |

| 13 | Z38 | 622 | C50 | 267 | O42 | 250 | O36 | 146 | P08 | 126 | D25 | 110 | O26 | 104 | O68 | 93 | O48 | 92 | O34 | 91 |

| 14 | Z38 | 1 263 | O70 | 406 | P08 | 318 | C50 | 303 | O68 | 284 | O32 | 252 | O42 | 233 | O63 | 218 | O34 | 198 | O80 | 146 |

| 15 | Z38 | 879 | D25 | 326 | C50 | 277 | O42 | 270 | O34 | 230 | O69 | 189 | O70 | 188 | O36 | 134 | O26 | 125 | O99 | 107 |

| 16 | Z38 | 689 | C50 | 660 | O70 | 310 | O34 | 266 | O60 | 191 | O68 | 171 | P07 | 127 | N81 | 112 | D25 | 111 | C56 | 83 |

| 17 | Z38 | 897 | C50 | 269 | O70 | 215 | O80 | 179 | D25 | 159 | O60 | 122 | O65 | 111 | O36 | 106 | N83 | 97 | O42 | 81 |

| 19 | Z38 | 671 | C50 | 636 | O70 | 291 | O71 | 255 | D25 | 223 | O34 | 140 | O42 | 100 | D05 | 96 | O62 | 94 | N83 | 79 |

| 20 | Z38 | 746 | C50 | 557 | O34 | 241 | O60 | 234 | O36 | 199 | O70 | 171 | P07 | 145 | D25 | 134 | O99 | 94 | P22 | 90 |

| 21 | Z38 | 1 559 | O70 | 392 | O71 | 252 | O60 | 242 | O68 | 224 | C53 | 161 | O64 | 146 | O34 | 144 | C50 | 141 | O42 | 122 |

| 22 | Z38 | 491 | O70 | 359 | C50 | 257 | O34 | 242 | O71 | 155 | D25 | 144 | O42 | 136 | C56 | 114 | O32 | 110 | P07 | 103 |

| 23 | Z38 | 582 | C50 | 373 | O70 | 221 | P08 | 194 | O34 | 174 | N80 | 160 | D25 | 153 | O60 | 141 | O71 | 128 | O68 | 124 |

| 24 | Z38 | 622 | C50 | 267 | O42 | 250 | O36 | 146 | P08 | 126 | D25 | 110 | O26 | 104 | O68 | 93 | O48 | 92 | O34 | 91 |

| 25 | Z38 | 1 057 | O42 | 335 | C50 | 311 | O68 | 174 | C53 | 156 | D25 | 149 | N39 | 145 | O34 | 134 | O60 | 134 | N81 | 126 |

| 26 | Z38 | 384 | C50 | 286 | O68 | 280 | O60 | 173 | O34 | 159 | O99 | 151 | P08 | 144 | P21 | 139 | O42 | 129 | D25 | 124 |

| 27 | Z38 | 857 | C50 | 468 | O70 | 232 | O68 | 178 | O34 | 174 | O80 | 157 | D25 | 145 | O60 | 115 | O63 | 108 | C56 | 97 |

| 28 | Z38 | 534 | C50 | 252 | O42 | 159 | N80 | 110 | O34 | 108 | O70 | 93 | O99 | 73 | D05 | 66 | O36 | 66 | D25 | 64 |

| 29 | Z38 | 1 755 | C50 | 677 | D25 | 631 | N81 | 369 | O42 | 324 | O70 | 263 | N83 | 258 | O34 | 230 | O60 | 229 | N39 | 228 |

| 30 | Z38 | 970 | O70 | 445 | O71 | 310 | C50 | 303 | Z03 | 226 | O34 | 141 | O42 | 133 | O68 | 115 | O64 | 98 | O99 | 95 |

| 31 | Z38 | 1 417 | C50 | 449 | O70 | 366 | O68 | 339 | O42 | 305 | O34 | 253 | P05 | 189 | N81 | 171 | O24 | 159 | P07 | 148 |

| 32 | Z38 | 1 090 | C50 | 464 | O70 | 359 | O71 | 278 | O82 | 239 | C56 | 229 | O42 | 128 | D25 | 118 | O34 | 95 | O02 | 92 |

Table 4 The 10 most common 10 OPS codes used in each UGC.

| 1 - 208 Recording of evoked potentials | ||||||||||

| 1 - 242 Audiometry, paediatric audiometry | ||||||||||

| 1 - 661 Diagnostic urethrocystoscopy | ||||||||||

| 1 - 671 Diagnostic colposcopy | ||||||||||

| 1 - 672 Diagnostic hysteroscopy | ||||||||||

| 1 - 853 Diagnostic (percutaneous) puncture and aspiration of the abdominal cavity | ||||||||||

| 5 - 892 Other incisions of the skin and hypodermis | ||||||||||

| 3 - 05 d Endosonography of female genitalia | ||||||||||

| 3 - 760 Probe measurement in SLNE (sentinel lymph node extirpation) | ||||||||||

| 5 - 401 Excision of individual lymph nodes and lymphatic vessels | ||||||||||

| 5 - 469 Other intestinal surgery | ||||||||||

| 5 - 543 Excision and destruction of peritoneal tissue | ||||||||||

| 5 - 549 Other abdominal surgery | ||||||||||

| 5 - 569 Other ureteral surgery | ||||||||||

| 5 - 657 Adhesiolysis of ovary and fallopian tube without microsurgery | ||||||||||

| 5 - 683 Exstirpation of the uterus (hysterectomy) | ||||||||||

| 5 - 704 Vaginal colporrhaphy and pelvic floor plasty | ||||||||||

| 5 - 730 Artificial rupture of membranes (amniotomy) | ||||||||||

| 5 - 738 Episiotomy and suturing | ||||||||||

| 5 - 740 Classic caesarean section | ||||||||||

| 5 - 741 Caesarean section, supracervical and corporal | ||||||||||

| 5 - 749 Other caesarean section | ||||||||||

| 5 - 756 Removal of retained placenta (postpartum) | ||||||||||

| 5 - 758 Reconstruction of female genitalia after rupture, postpartum (perineal tear) | ||||||||||

| 5 - 870 Partial (breast-conserving) excision of the breast and destruction of breast tissue without axillary lymphadenectomy | ||||||||||

| 5 - 983 Re-operation: this additional code must be used if the operated area is re-opened to treat a complication, to perform an operation for recurrence | ||||||||||

| 5 - 932 Type of material used for tissue replacement and tissue reinforcement | ||||||||||

| 6 - 001 Administration of drugs, list 1 | ||||||||||

| 6 - 002 Administration of drugs, list 2 | ||||||||||

| 8 - 132 Bladder manipulations | ||||||||||

| 8 - 542 Uncomplicated chemotherapy: 1 day | ||||||||||

| 8 - 543 Moderately complex and intensive chemotherapy administered over more than 1 day | ||||||||||

| 8 - 547 Other immunotherapy | ||||||||||

| 8 - 711 Mechanical ventilation and assisted ventilation of neonates and infants | ||||||||||

| 8 - 910 Epidural injection and infusion for pain therapy | ||||||||||

| 8 - 930 Monitoring of breathing and cardiovascular parameters without measurement of pulmonary artery pressure or central venous pressure | ||||||||||

| 8 - 980 Intensive medical care for complex treatment (basic procedures) | ||||||||||

| 9 - 260 Monitoring and delivery for a normal birth | ||||||||||

| 9 - 261 Monitoring and delivery for a high-risk birth | ||||||||||

| 9 - 262 Postpartum care of the neonate | ||||||||||

| 9 - 401 Psychosocial interventions | ||||||||||

| Clinic | OPS1 | N1 | OPS2 | N2 | OPS3 | N3 | OPS4 | N4 | OPS5 | N5 |

| 3 | 1 - 208 | 825 | 5 - 749 | 803 | 5 - 758 | 505 | 9 - 261 | 208 | 5 - 870 | 158 |

| 14 | 8 - 542 | 3 041 | 9 - 262 | 1 892 | 5 - 758 | 1 104 | 9 - 261 | 861 | 5 - 749 | 787 |

| 16 | 8 - 542 | 3 901 | 8 - 547 | 2 727 | 6 - 001 | 1 456 | 6 - 002 | 1 178 | 9 - 262 | 1 064 |

| 12 | 9 - 260 | 327 | 5 - 758 | 272 | 5 - 749 | 253 | 5 - 870 | 191 | 5 - 738 | 180 |

| 4 | 9 - 260 | 1 057 | 9 - 262 | 1 056 | 1 - 208 | 997 | 5 - 758 | 766 | 5 - 749 | 563 |

| 32 | 9 - 261 | 454 | 8 - 542 | 384 | 5 - 740 | 424 | 5 - 758 | 323 | 5 - 401 | 285 |

| 18 | 9 - 261 | 1 180 | 9 - 262 | 1 173 | 8 - 542 | 970 | 5 - 758 | 859 | 8 - 547 | 437 |

| 26 | 9 - 261 | 1 328 | 9 - 262 | 1 107 | 8 - 543 | 965 | 1 - 208 | 896 | 5 - 758 | 721 |

| 13 | 9 - 262 | 884 | 1 - 208 | 854 | 5 - 749 | 434 | 1 - 671 | 423 | 5 - 704 | 414 |

| 27 | 9 - 262 | 1 099 | 5 - 401 | 526 | 5 - 740 | 448 | 5 - 870 | 396 | 5 - 758 | 374 |

| 2 | 9 - 262 | 3 301 | 9 - 261 | 2 726 | 1 - 208 | 2 425 | 9 - 260 | 1 887 | 8 - 910 | 1 761 |

| 1 | 9 - 262 | 876 | 5 - 749 | 239 | 9 - 260 | 183 | 5 - 740 | 162 | 9 - 261 | 156 |

| 5 | 9 - 262 | 1 679 | 5 - 740 | 628 | 9 - 260 | 511 | 5 - 758 | 465 | 5 - 740 | 424 |

| 6 | 9 - 262 | 1 688 | 1 - 208 | 1 562 | 5 - 758 | 846 | 8 - 542 | 846 | 9 - 261 | 697 |

| 7 | 9 - 262 | 657 | 1 - 242 | 623 | 5 - 749 | 476 | 9 - 260 | 317 | 5 - 870 | 284 |

| 8 | 9 - 262 | 1 473 | 5 - 758 | 976 | 5 - 749 | 631 | 9 - 261 | 527 | 5 - 870 | 235 |

| 9 | 9 - 262 | 1 344 | 8 - 930 | 1 237 | 1 - 208 | 943 | 5 - 741 | 711 | 3 - 05 d | 596 |

| 10 | 9 - 262 | 1 445 | 5 - 740 | 458 | 9 - 261 | 437 | 5 - 730 | 381 | 5 - 758 | 283 |

| 11 | 9 - 262 | 552 | 5 - 741 | 336 | 9 - 261 | 332 | 9 - 401 | 295 | 5 - 401 | 250 |

| 24 | 9 - 262 | 1 157 | 9 - 260 | 515 | 5 - 738 | 357 | 9 - 261 | 308 | 5 - 730 | 276 |

| 15 | 9 - 262 | 1 718 | 9 - 261 | 599 | 5 - 749 | 561 | 5 - 758 | 468 | 9 - 260 | 414 |

| 19 | 9 - 262 | 1 303 | 5 - 758 | 662 | 9 - 260 | 634 | 1 - 208 | 572 | 5 - 740 | 458 |

| 20 | 9 - 262 | 1 450 | 5 - 749 | 815 | 8 - 711 | 511 | 9 - 260 | 446 | 5 - 870 | 423 |

| 21 | 9 - 262 | 1 565 | 5 - 758 | 908 | 9 - 261 | 822 | 5 - 730 | 705 | 9 - 260 | 615 |

| 22 | 9 - 262 | 3 398 | 1 - 208 | 2 950 | 9 - 261 | 2 623 | 5 - 758 | 2 406 | 8 - 910 | 2 198 |

| 23 | 9 - 262 | 999 | 5 - 758 | 508 | 9 - 401 | 473 | 5 - 740 | 428 | 1 - 208 | 364 |

| 31 | 9 - 262 | 2 541 | 1 - 208 | 1 797 | 5 - 758 | 1 593 | 9 - 261 | 1 404 | 5 - 730 | 823 |

| 25 | 9 - 262 | 1 375 | 9 - 261 | 830 | 8 - 910 | 769 | 5 - 740 | 534 | 5 - 738 | 414 |

| 17 | 9 - 262 | 1 011 | 1 - 208 | 943 | 5 - 749 | 417 | 5 - 758 | 345 | 5 - 738 | 255 |

| 28 | 9 - 262 | 682 | 5 - 749 | 411 | 5 - 401 | 291 | 5 - 758 | 259 | 9 - 401 | 244 |

| 30 | 9 - 262 | 1 296 | 5 - 758 | 981 | 8 - 910 | 866 | 8 - 930 | 777 | 5 - 749 | 631 |

| 29 | 9 - 262 | 2 677 | 5 - 983 | 1 295 | 9 - 260 | 1 197 | 5 - 758 | 1 118 | 5 - 740 | 1 020 |

| Clinic | OPS6 | N6 | OPS7 | N7 | OPS8 | N8 | OPS9 | N9 | OPS10 | N10 |

| 13 | 9 - 261 | 403 | 5 - 758 | 299 | 5 - 932 | 254 | 5 - 401 | 240 | 5 - 870 | 229 |

| 32 | 5 - 870 | 230 | 5 - 756 | 220 | 5 - 683 | 205 | 5 - 690 | 177 | 5 - 653 | 162 |

| 3 | 5 - 754 | 146 | 1 - 672 | 142 | 9 - 262 | 130 | 9 - 260 | 98 | 5 - 543 | 97 |

| 29 | 8 - 910 | 792 | 5 - 704 | 786 | 5 - 657 | 772 | 1 - 853 | 771 | 5 - 681 | 709 |

| 14 | 5 - 892 | 745 | 8 - 547 | 442 | 9 - 260 | 438 | 8 - 547 | 442 | 5 - 870 | 296 |

| 16 | 8 - 543 | 877 | 5 - 749 | 845 | 8 - 930 | 678 | 5 - 758 | 495 | 8 - 800 | 417 |

| 18 | 5 - 401 | 285 | 5 - 704 | 268 | 5 - 749 | 268 | 5 - 549 | 267 | 6 - 001 | 226 |

| 12 | 5 - 683 | 177 | 9 - 261 | 160 | 8 - 522 | 150 | 3 - 990 | 141 | 9 - 401 | 140 |

| 27 | 5 - 683 | 248 | 9 - 401 | 231 | 5 - 657 | 229 | 9 - 261 | 196 | 9 - 260 | 176 |

| 4 | 5 - 738 | 470 | 8 - 910 | 382 | 9 - 261 | 381 | 8 - 542 | 340 | 5 - 730 | 238 |

| 2 | 5 - 749 | 1 602 | 5 - 758 | 1 000 | 5 - 730 | 634 | 1 - 472 | 614 | 5 - 738 | 536 |

| 26 | 5 - 749 | 506 | 6 - 001 | 490 | 8 - 910 | 209 | 8 - 547 | 208 | 5 - 740 | 195 |

| 1 | 5 - 758 | 124 | 5 - 738 | 117 | 5 - 683 | 97 | 5 - 690 | 88 | 5 - 651 | 67 |

| 5 | 9 - 261 | 402 | 5 - 738 | 241 | 5 - 690 | 158 | 5 - 728 | 139 | 5 - 870 | 135 |

| 6 | 5 - 749 | 695 | 8 - 910 | 658 | 5 - 730 | 641 | 5 - 401 | 572 | 5 - 657 | 568 |

| 7 | 5 - 758 | 267 | 5 - 730 | 256 | 5 - 657 | 255 | 8 - 910 | 220 | 9 - 261 | 217 |

| 8 | 5 - 720 | 201 | 5 - 401 | 181 | 5 - 756 | 136 | 1 - 672 | 128 | 5 - 690 | 107 |

| 9 | 5 - 758 | 494 | 5 - 881 | 448 | 9 - 261 | 391 | 9 - 260 | 328 | 5 - 870 | 327 |

| 10 | 1 - 208 | 256 | 5 - 983 | 236 | 5 - 738 | 210 | 9 - 280 | 198 | 5 - 683 | 184 |

| 11 | 5 - 870 | 238 | 5 - 758 | 194 | 5 - 738 | 186 | 8 - 543 | 185 | 5 - 886 | 162 |

| 24 | 5 - 758 | 271 | 5 - 749 | 243 | 8 - 910 | 219 | 5 - 683 | 184 | 8 - 542 | 173 |

| 15 | 5 - 738 | 381 | 5 - 681 | 327 | 5 - 469 | 221 | 5 - 683 | 202 | 5 - 651 | 187 |

| 19 | 5 - 870 | 384 | 3 - 760 | 318 | 5 - 401 | 295 | 5 - 657 | 272 | 5 - 681 | 230 |

| 20 | 5 - 886 | 410 | 5 - 758 | 324 | 5 - 401 | 317 | 9 - 261 | 230 | 5 - 681 | 158 |

| 21 | 5 - 749 | 587 | 8 - 020 | 502 | 8 - 910 | 428 | 5 - 738 | 389 | 3 - 990 | 308 |

| 22 | 5 - 749 | 1 162 | 8 - 132 | 1 033 | 8 - 930 | 672 | 9 - 260 | 439 | 5 - 690 | 398 |

| 23 | 5 - 738 | 260 | 5 - 401 | 241 | 9 - 260 | 231 | 3 - 760 | 217 | 5 - 683 | 215 |

| 31 | 5 - 749 | 625 | 5 - 740 | 582 | 5 - 401 | 378 | 8 - 930 | 376 | 8 - 980 | 370 |

| 25 | 5 - 704 | 386 | 9 - 260 | 286 | 5 - 683 | 237 | 1 - 471 | 221 | 5 - 749 | 200 |

| 17 | 5 - 740 | 253 | 5 - 651 | 241 | 5 - 469 | 236 | 5 - 870 | 214 | 5 - 401 | 186 |

| 28 | 9 - 260 | 238 | 9 - 261 | 234 | 5 - 870 | 176 | 5 - 702 | 170 | 1 - 900 | 144 |

| 30 | 8 - 810 | 283 | 5 - 401 | 270 | 5 - 870 | 246 | 5 - 657 | 202 | 5 - 886 | 172 |

The most common diagnosis was Z38 (30 clinics, range: 384–1559) with one clinic listing O68 as the most common (n = 399). In 3 clinics Z38 was not found among the 10 most common diagnoses. In these clinics C50 (2 clinics, 331 and 460, respectively) and O42 (1 clinic, n = 435) were the most frequently diagnosis.

The second most common diagnoses were: C50 (14 clinics, range: 267–840), D25 (6 clinics, range: 144–631), O70 (5 clinics, range: 330–445), O42 (2 clinics, range: 267–335), O68 in two clinics (n = 428), O60 (n = 175), O34 (n = 232), N39 (n = 109) and Z38 (n = 393).

The third most common diagnoses were obstetrical (O68, O42, O24, O34, O70, O71, O99; 24 clinics, range: 125–344), N81 (3 clinics, range: 105–369), C50 (3 clinics, range: 257–311), D25 twice (n = 52 und n = 82), C56 twice (n = 97 und n = 132).

The fourth most common diagnoses were mostly obstetrical (n = 14, range 116–295), gynaecological (9 clinics, range: 70–275) and gynaecological oncology diagnoses (6 clinics, range: 43–347).

The fifth most common diagnoses were obstetrical (n = 23, range 85–302), gynaecological (6 clinics, range: 33–228) and gynaecological oncology diagnoses (2 clinics, range: 119–156).

Thereafter, the most common diagnoses were obstetrical diagnoses (the sixth most common in 19 clinics, the seventh most common in 22 clinics, the eighth most common in 18 clinics, the ninth most common in 20 clinics and the tenth most common in 20 clinics).

When assessing individual clinics according to the most common diagnoses (10 most common) of the 86 968 diagnoses made, 77.7 % (43.4–100 %) were obstetrical diagnoses. With the exception of 4 clinics, the diagnosis Z38 is the most common. In one clinic it was the second most common, while in 3 clinics it did not make the top 10. 15 % of cases were gynaecological-oncology diagnoses and 7.3 % of diagnoses were purely gynaecological.

The average number of gynaecological diagnoses among the top 10 was 2.5 (0–5). The remaining 7.5 were obstetrical diagnoses.

The 2010 quality reports listed 31 UHs with a level 1 perinatal centre. Only one UH did not have a level 1 perinatal centre. 17 quality reports described their facility as a CCC (comprehensive cancer centre).

Discussion

Quality reports are published every 2 years. The collected data are standardised and are intended to help patients select the optimal clinic for their needs. The high level of standardisation has the advantage that it permits data from different clinics to be compared. But the quality reports are quite extensive and difficult for patients to interpret. The contents of quality reports offer few benefits. Quality reports focus in the first instance on data relating to the infrastructure of the entire hospital complex (Part A of the quality report) and of the specialist clinics (Part B of the quality report), together with quantitative information such as ICD codes (diagnoses), therapies and staffing levels. However the level of specialist expertise available in the respective clinic is difficult to represent in these reports. The quality of care cannot be easily objectified. There are numerous quality criteria for every disorder, which only describe certain aspects. These quality criteria are so extensive that they cannot be integrated into a quality report. But not all diseases have quality criteria, and even when quality criteria are defined, opinions often diverge as to the significance of various criteria 4.

Quality reports are not well known. Several retrospective studies have shown that fewer than half of all surveyed physicians knew of the existence of these legally mandated quality reports. Younger physicians were more likely to know about them but did not use the quality reports more frequently than their older colleagues. Overall, only about one in ten physicians stated that they actively made use of quality reports in their original format during consultations with patients. Some preferred to use the electronic versions of the quality report data, particularly in the format provided by some of the numerous internet portals which offer comparisons between hospitals. Overall, the legally mandated quality reports played only a minor role in the run-up to patients being admitted to hospital 6.

The situation is rather different for rehab clinics and psychosomatic clinics. The quality reports of rehab clinics are consulted by (potential) users who view them as an important source of information. The reports do not focus on the target group “Patients” and do not predominantly look at the most important areas of interest 7. The introduction of quality reports for psychosomatic clinics provided an initial approach, allowing these clinics to be compared based on their infrastructure and the quality of their processes 8.

This study compared the quality reports of university gynaecology clinics. The question was, which data could a potential user deduce from a comparison of quality reports.

When comparing university hospitals, it was noticeable that the number of inpatients per year treated at different clinics varied widely (from 35 324 to 128 017). This figure is surely of little relevance for patients. A university hospital with lower number of patients can possess outstanding specialist knowledge in a particular field and a university hospital with high numbers of patients may not offer the required expert knowledge. The probability of specific specialist knowledge being available may be higher in a large university hospital compared to a small one, but the potential user has to read Part B of the quality report to find out. To usefully compare the number of inpatients per year, it is necessary to look at and compare numerous quality reports. Very few users are likely to make the effort 9.

The same applies to comparisons of university gynaecology clinics. The number of inpatients ranges from 2729 to 15 148 inpatients/year. One significant factor for this wide range could be the amalgamation of several different sites to form a single university hospital (e.g. Berlin, Munich). But once this point was factored in (recalculated into number of inpatients/site), there are still big differences in the number of patients treated per university gynaecology clinic (range: 2729 to 10 486 inpatients/year). Thus, there was a correlation between patient numbers of UGCs and those of the UHs. This correlation is unsurprising and can best be explained by the local conditions (site, radius, competitors). 60 % of UGCs treated between 4000 and 6000 patients, and 77 % treated between 3000 and 7000 inpatients per year. The local healthcare infrastructure for the area where the respective university hospital was sited played a decisive role. For some university hospitals, local circumstances dictated that they were also needed to provide primary and secondary care, while in other regions the UHs existed alongside numerous competitors.

In terms of percentages, the UGCs with their 10 % of inpatients are an important part of their UH. 77 % of UGCs treat between 7 and 12 % of patients; 17 % of UGCs even treat more than 12 % of their university hospitalʼs annual inpatients. UGCs therefore represent an important port of entry for other specialist clinics. These include, in the first instance, the neonatology departments, which receive most of their cases directly from the UGC. Oncology patients from a UGC are very important for every UH because of the interdisciplinary cooperation required to treat these patients. These patients receive treatment from other departments such as Radiodiagnostics, Nuclear Medicine, Radiotherapy, Internal Medicine, Abdominal Surgery, Urology, Neurology, Neurosurgery, Orthopaedics, etc. Thus, every UGC is a key department for its respective UH and represents an important economic factor.

There were also important differences in staffing levels between UGCs. With numbers of resident physicians ranging from 16 to 78, the differences are significant. The numbers of patients treated per full-time physician also differed greatly. These differences were due to differences in teaching and research facilities, the calculation of inpatient numbers (all children or only some of them or none credited to the inpatient numbers of the UGC), outpatient care, accreditation with statutory health insurance companies, etc. But this data does not make it possible to describe one clinic as “more effective” than another.

In addition, research and teaching are part of the services provided by a UGC but they are not taken into consideration in the quality reports. Cross financing of staff using the budget for research and teaching is often necessary to guarantee patient care. In many cases, when staffing levels are calculated, the calculation does not include outpatient services (outpatient consultations, etc.). Outpatient services are only profitable if they can be used to recruit inpatients or patients for day surgery procedures. Controls or follow-up visits are not taken into account.

The number of medical specialists could be another possible indicator when assessing a UGC. However, here again comparisons are tricky as medical specialists may work in different capacities (e.g. senior physician). The quality report does not show the level of qualifications obtained, the experience, medical speciality, etc. of individual physicians.

This means that the quality reports offer no accurate chance of comparing clinics on the basis of staffing ratios. Patients are not provided with this background information and they may even draw the wrong conclusions.

The range of services provided by UGCs varies greatly. It is virtually impossible to deduce which areas a hospital has specialised in based on the data obtained from quality reports. The data are based on ICD codes (diagnosis). These codes do not reflect quality of treatment or medical expertise.

The most common diagnoses (ICD codes) are obstetrical and include deliveries, care of neonates and suturing after vaginal delivery. This provides an approximate figure which allows the number of deliveries to be estimated. The rate of transfers of neonates to the neonatology department is inconsistent. For 3 clinics, Z38 was not among the top 10 diagnoses. In these cases, all newborns were probably assigned to the paediatric clinic and not to the gynaecological clinic. The number of gynaecological diagnoses and surgical procedures was therefore often lower than for obstetrics. The level of gynaecological expertise is difficult to deduce based on the services provided. From the point of view of an external observer, it is very difficult to infer the level of expertise present in a specific clinic based on the list of ICD and OPS codes. There are no figures on complications, morbidities or even survival rates.

All of the UGCs are virtually identical with regard to equipment, facilities and medical specialties. All UGCs have breast centres, gynaecological oncology centres, pelvic floor centres, perinatal centres, centres for minimally invasive surgery, prenatal diagnostics and urodynamics. It is not possible to obtain information useful for patients based on the list of the UGCʼs medical specialties given in the quality report. Moreover all UGCs have virtually the same facilities and equipment.

All UHs are now level I perinatal centres. At the time of publication, only one UH was not a level I perinatal centre but it became one shortly thereafter. 17 UHs described themselves as a CCC. However not all CCCs are supported by German Cancer Aid. The term CCC is not protected, making it impossible for readers to differentiate between centres.

UGCs have not been previously compared. In a study on obstetrics by Bauer et al. 5 published in 2011, home births were compared with delivery in hospital. The intact perineum rate was higher for home births, but there were no differences with regard to Apgar 10 scores. But pre-selection of cases in this study cannot be excluded. Hospital births will obviously include higher rates of high risk births. The choice of a home birth is generally done after considering the risk factors. We found no other comparisons using the quality reports.

Overall, it is very difficult for patients and for the physicians who arrange their admission to hospital to obtain crucial information from quality reports.

Quality reports contain too much information. Around one third of all published data are superfluous 10. Disadvantages of quality reports include a lack of indicators providing information on patientsʼ experiences and the clinicʼs reputation. A survey of potential user groups would provide better descriptions 10. Patients prefer quality comparison graphs which provide a lot of information and rank hospitals 10. The text sections in the reports aimed at patients are currently not easy to read and are not formulated so that they can be easily understood 12.

Legally mandated quality reports are currently not used by physicians as a useful source of information when advising patients. For this, quality reports would have to become more widely known and physicians would have to place more confidence in this form of reporting. Some of the objective data on structures and services required by physicians is already included in the quality reports. But it would be important to consider how “soft” factors could additionally be included in these reporting tools 11. The readability and comprehensibility of texts for patients could still be improved. It has been suggested that patients and physicians working outside hospitals could offer concrete approaches and proposals on changes to be implemented when drawing up quality reports in future 7, 12.

In 2007 Streuf et al. 13 investigated the most important criteria behind patient selection of a particular hospital. It turned out that the advice most relied on and accorded the greatest importance was the information given to a patient by his or her family doctor. Newspapers, journals and the internet came second. However, in the ranking of importance, the internet ranked below the advice given by the family physician and information obtained from friends and relatives. The most important selection criteria were a hospitalʼs good reputation, a good cooperation between the hospital and physicians working outside the hospital, and the number of cases treated. Of these criteria, only the number of cases treated can be obtained from quality reports. Five years ago, quality reports played almost no role in hospital selection by patients. It should be noted that quality reports have changed very little in recent years and it must be assumed that the criteria referred to above are still applicable today.

In summary, quality reports use a very broad brush to describe the infrastructure and services of the UHs. The specific characteristics of a UGC within a hospital offering comprehensive inpatient and outpatient care and special consultation services which are time-consuming, demanding and require high staffing levels are not reflected in the quality report. The quality of treatment is not shown. For external readers it is extremely difficult to find any differences between UGCs. UGCs are an important part of UHs.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest None.

Supporting Information

German supporting informations for this article

References

- 1.Lux M P, Reichelt C, Karnon J. et al. Kosten-Nutzwert-Analyse endokriner Therapien in der adjuvanten Situation der postmenopausalen Patientin mit einem hormonrezeptorpositiven Mammakarzinom auf Basis der Überlebensdaten und Berücksichtigung zukünftiger generischer Preise aus der Sicht des deutschen Gesundheitswesens. Geburtsh Frauenheilk. 2011:71-P210. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Simoes E, Brucker S, Beckmann M W. et al. Screening for cervical cancer – minimise risks – maximise benefits. Need for adaptation in Germany in light of the European guidelines and their objectives. Geburtsh Frauenheilk. 2013;73:623–639. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Diedrich K, Strowitzki T, Kentenich H. The state of reproductive medicine in Germany. Geburtsh Frauenheilk. 2012;72:225–234. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1298358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schmidt M, Fasching P A, Beckmann M W. et al. Biomarkers in breast cancer – an update. Geburtsh Frauenheilk. 2012;72:819–832. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1315340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bauer S H, Wiemer A, Misselwitz B. et al. Ergebnisse des Pilotprojekts zum Vergleich klinischer Geburten (Hessen) mit außerklinischen Geburten (Bund) Z Geburtshilfe Neonatol. 2011:215-FV01_01. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1293211. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hermeling P, Geraedts M. Kennen und nutzen Ärzte den strukturierten Qualitätsbericht? Gesundheitswesen. 2012 doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1321744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Seidel G, Haase I, Walle E. et al. Verständlichkeit und Nutzen von Qualitätsberichten Rehabilitation aus Sicht der Nutzer. Gesundheitswesen. 2009:71-A254. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1239304. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jagdfeld F H. Struktur-, Prozess- und Ergebnisqualität psychosomatischer Kliniken im strukturierten Qualitätsbericht nach § 137 SGB V. Psychother Psych Med. 2008:58-S78. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1061584. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lux M P, Hildebrandt T, Bani M. et al. Health economic evaluation of different decision aids for the individualised treatment of patients with breast cancer. Geburtsh Frauenheilk. 2013;73:599–610. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schwartze D, Geraedts M. Eignung von Qualitätsindikatoren und grafischen Qualitätsvergleichen zur informierten Krankenhauswahl durch Patienten. Gesundheitswesen. 2006:68-A114. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-948670. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hermeling P de Cruppé W Geraedts M Qualitätsberichte zur Unterstützung der ärztlichen Patientenberatung Gesundheitswesen 201173-A90. 10.1055/s-0031-128348021249625 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Friedemann J, Schubert H-J, Schwappach D. Zur Verständlichkeit der Qualitätsberichte deutscher Krankenhäuser: Systematische Auswertung und Handlungsbedarf. Gesundheitswesen. 2009;71:3–9. doi: 10.1055/s-0028-1086010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Streuf R, Maciejek S, Kleinfeld A. et al. Informationsbedarf und Informationsquelle bei der Wahl eines Krankenhauses. Gesund Ökon Qual Manag. 2007;12:113–120. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

German supporting informations for this article