Abstract

Zip1 is a yeast synaptonemal complex (SC) central region component and is required for normal meiotic recombination and crossover interference. Physical analysis of meiotic recombination in a zip1 mutant reveals the following: Crossovers appear later than normal and at a reduced level. Noncrossover recombinants, in contrast, seem to appear in two phases: (i) a normal number appear with normal timing and (ii) then additional products appear late, at the same time as crossovers. Also, Holliday junctions are present at unusually late times, presumably as precursors to late-appearing products. Red1 is an axial structure component required for formation of cytologically discernible axial elements and SC and maximal levels of recombination. In a red1 mutant, crossovers and noncrossovers occur at coordinately reduced levels but with normal timing. If Zip1 affected recombination exclusively via SC polymerization, a zip1 mutation should confer no recombination defect in a red1 strain background. But a red1 zip1 double mutant exhibits the sum of the two single mutant phenotypes, including the specific deficit of crossovers seen in a zip1 strain. We infer that Zip1 plays at least one role in recombination that does not involve SC polymerization along the chromosomes. Perhaps some Zip1 molecules act first in or around the sites of recombinational interactions to influence the recombination process and thence nucleate SC formation. We propose that a Zip1-dependent, pre-SC transition early in the recombination reaction is an essential component of meiotic crossover control. A molecular basis for crossover/noncrossover differentiation is also suggested.

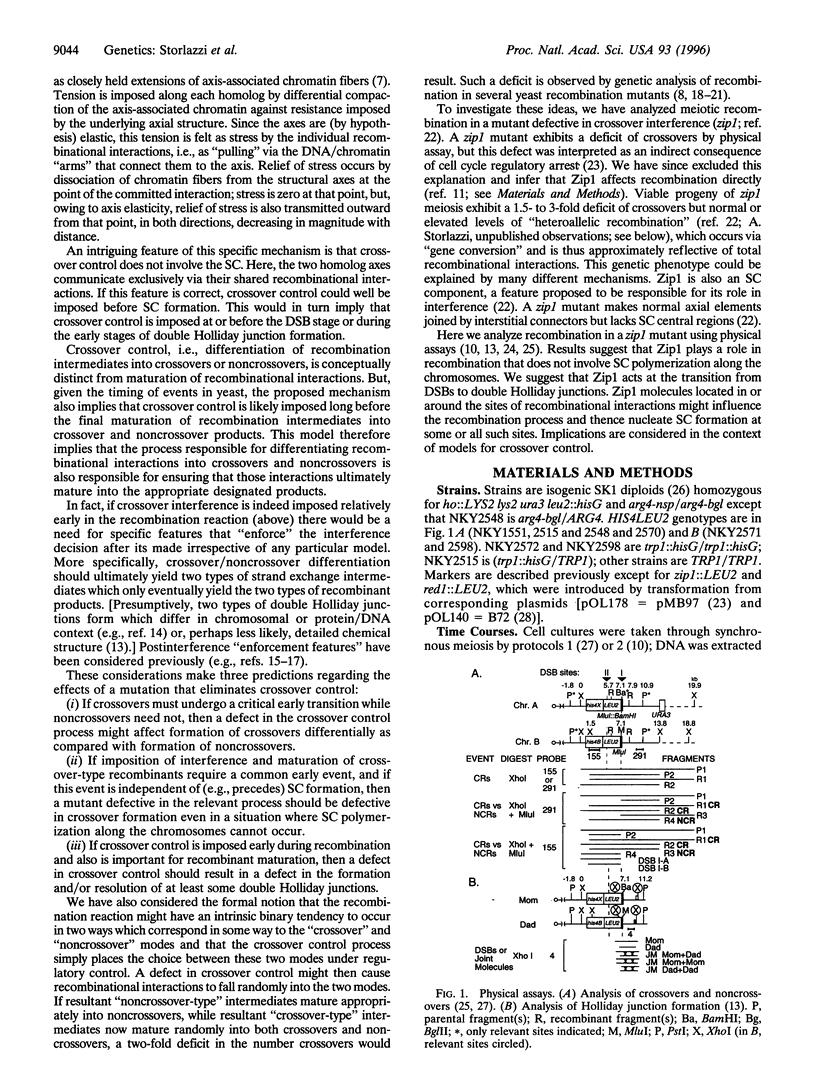

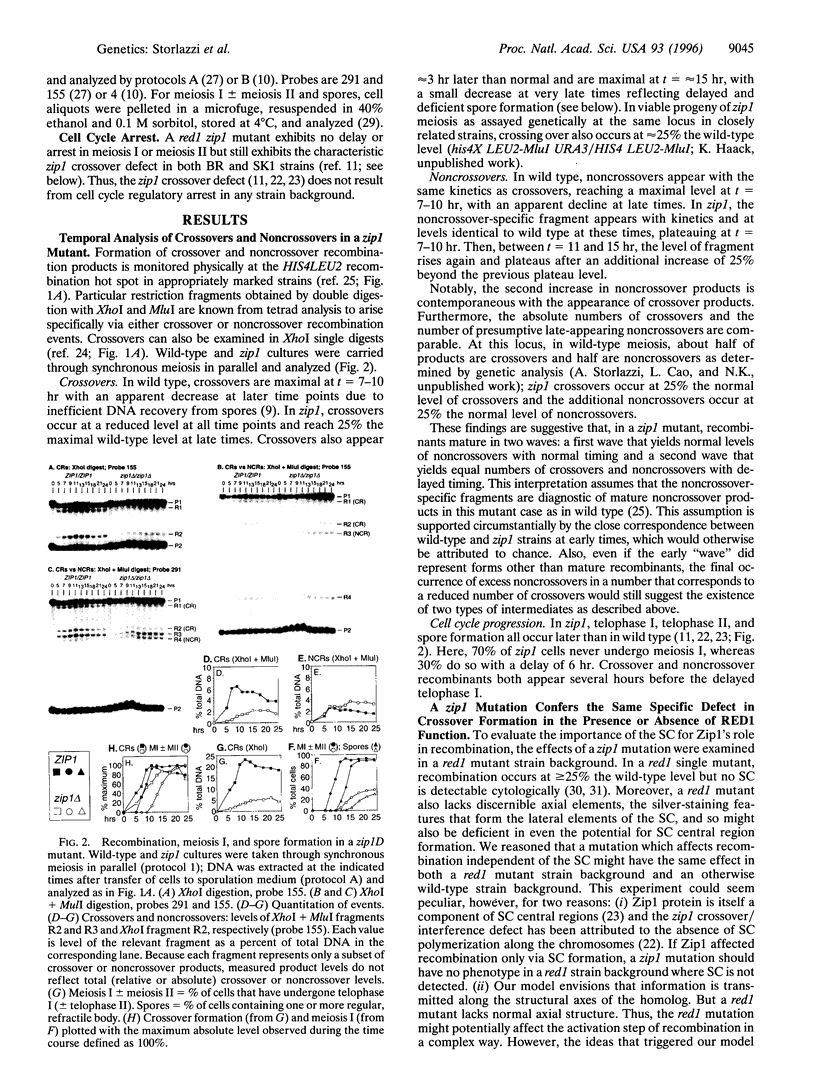

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Alani E., Cao L., Kleckner N. A method for gene disruption that allows repeated use of URA3 selection in the construction of multiply disrupted yeast strains. Genetics. 1987 Aug;116(4):541–545. doi: 10.1534/genetics.112.541.test. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alani E., Padmore R., Kleckner N. Analysis of wild-type and rad50 mutants of yeast suggests an intimate relationship between meiotic chromosome synapsis and recombination. Cell. 1990 May 4;61(3):419–436. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90524-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett R. J., West S. C. Structural analysis of the RuvC-Holliday junction complex reveals an unfolded junction. J Mol Biol. 1995 Sep 15;252(2):213–226. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1995.0489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao L., Alani E., Kleckner N. A pathway for generation and processing of double-strand breaks during meiotic recombination in S. cerevisiae. Cell. 1990 Jun 15;61(6):1089–1101. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90072-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter A. T. Mismatch repair, gene conversion, and crossing-over in two recombination-defective mutants of Drosophila melanogaster. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1982 Oct;79(19):5961–5965. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.19.5961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter A. T. Recombination nodules and synaptonemal complex in recombination-defective females of Drosophila melanogaster. Chromosoma. 1979;75(3):259–292. doi: 10.1007/BF00293472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egel R. Synaptonemal complex and crossing-over: structural support or interference? Heredity (Edinb) 1978 Oct;41(2):233–237. doi: 10.1038/hdy.1978.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engebrecht J., Hirsch J., Roeder G. S. Meiotic gene conversion and crossing over: their relationship to each other and to chromosome synapsis and segregation. Cell. 1990 Sep 7;62(5):927–937. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90267-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holliday R. Recombination and meiosis. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1977 Mar 21;277(955):359–370. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1977.0024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollingsworth N. M., Ponte L., Halsey C. MSH5, a novel MutS homolog, facilitates meiotic reciprocal recombination between homologs in Saccharomyces cerevisiae but not mismatch repair. Genes Dev. 1995 Jul 15;9(14):1728–1739. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.14.1728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones G. H. The control of chiasma distribution. Symp Soc Exp Biol. 1984;38:293–320. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King J. S., Mortimer R. K. A polymerization model of chiasma interference and corresponding computer simulation. Genetics. 1990 Dec;126(4):1127–1138. doi: 10.1093/genetics/126.4.1127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleckner N. Meiosis: how could it work? Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996 Aug 6;93(16):8167–8174. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.16.8167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lande R., Stahl F. W. Chiasma interference and the distribution of exchanges in Drosophila melanogaster. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 1993;58:543–552. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1993.058.01.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nag D. K., Scherthan H., Rockmill B., Bhargava J., Roeder G. S. Heteroduplex DNA formation and homolog pairing in yeast meiotic mutants. Genetics. 1995 Sep;141(1):75–86. doi: 10.1093/genetics/141.1.75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padmore R., Cao L., Kleckner N. Temporal comparison of recombination and synaptonemal complex formation during meiosis in S. cerevisiae. Cell. 1991 Sep 20;66(6):1239–1256. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palladino F., Klein H. L. Analysis of mitotic and meiotic defects in Saccharomyces cerevisiae SRS2 DNA helicase mutants. Genetics. 1992 Sep;132(1):23–37. doi: 10.1093/genetics/132.1.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rockmill B., Roeder G. S. Meiosis in asynaptic yeast. Genetics. 1990 Nov;126(3):563–574. doi: 10.1093/genetics/126.3.563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rockmill B., Roeder G. S. RED1: a yeast gene required for the segregation of chromosomes during the reductional division of meiosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988 Aug;85(16):6057–6061. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.16.6057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rockmill B., Sym M., Scherthan H., Roeder G. S. Roles for two RecA homologs in promoting meiotic chromosome synapsis. Genes Dev. 1995 Nov 1;9(21):2684–2695. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.21.2684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roeder G. S. Sex and the single cell: meiosis in yeast. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995 Nov 7;92(23):10450–10456. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.23.10450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross-Macdonald P., Roeder G. S. Mutation of a meiosis-specific MutS homolog decreases crossing over but not mismatch correction. Cell. 1994 Dec 16;79(6):1069–1080. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90037-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

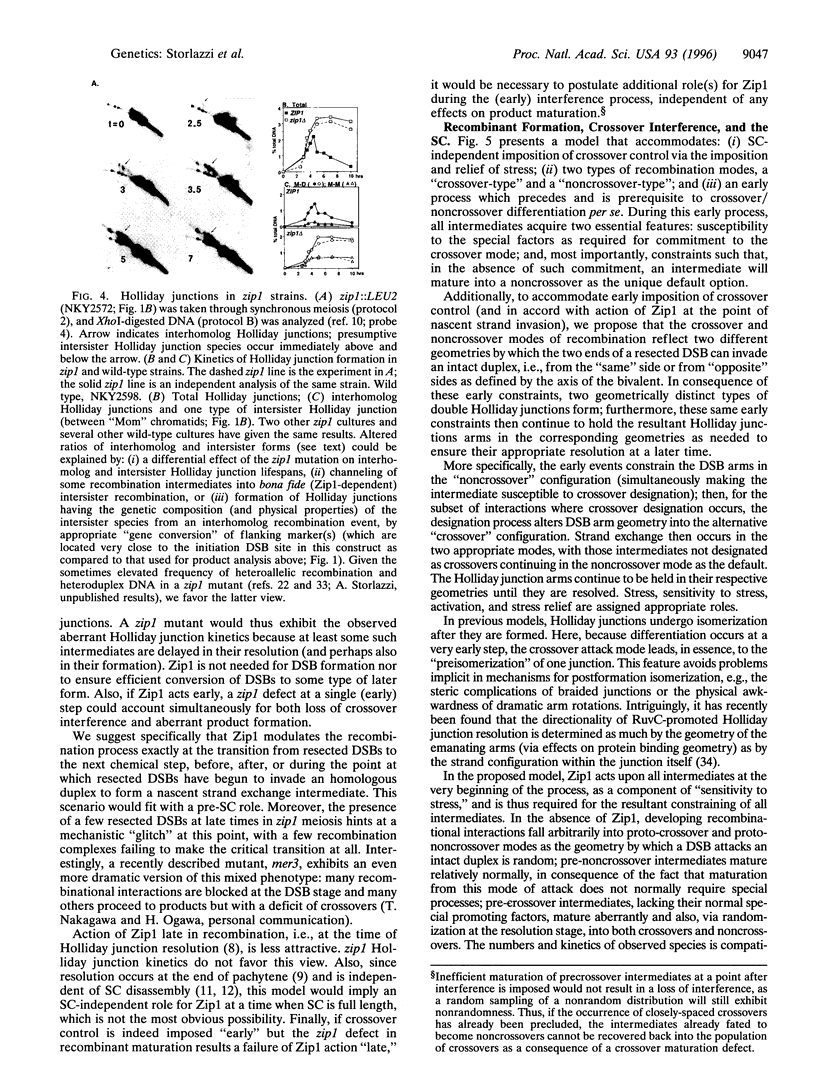

- Schwacha A., Kleckner N. Identification of double Holliday junctions as intermediates in meiotic recombination. Cell. 1995 Dec 1;83(5):783–791. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90191-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwacha A., Kleckner N. Identification of joint molecules that form frequently between homologs but rarely between sister chromatids during yeast meiosis. Cell. 1994 Jan 14;76(1):51–63. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90172-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

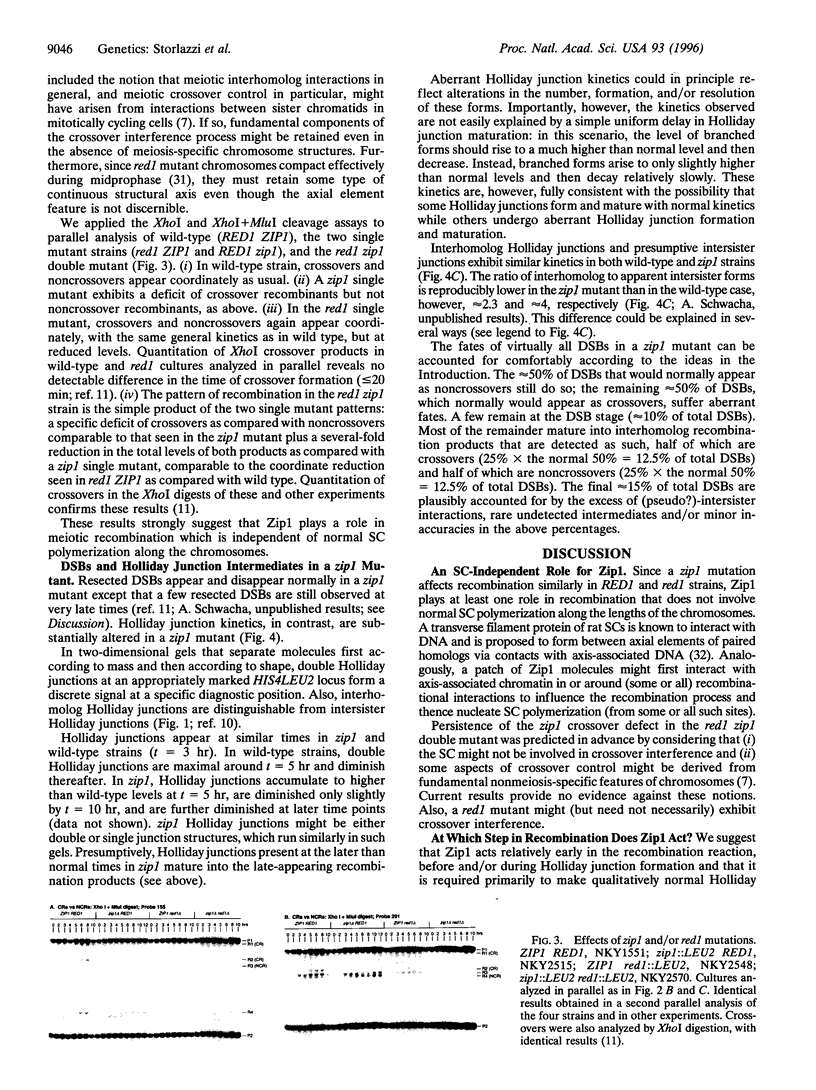

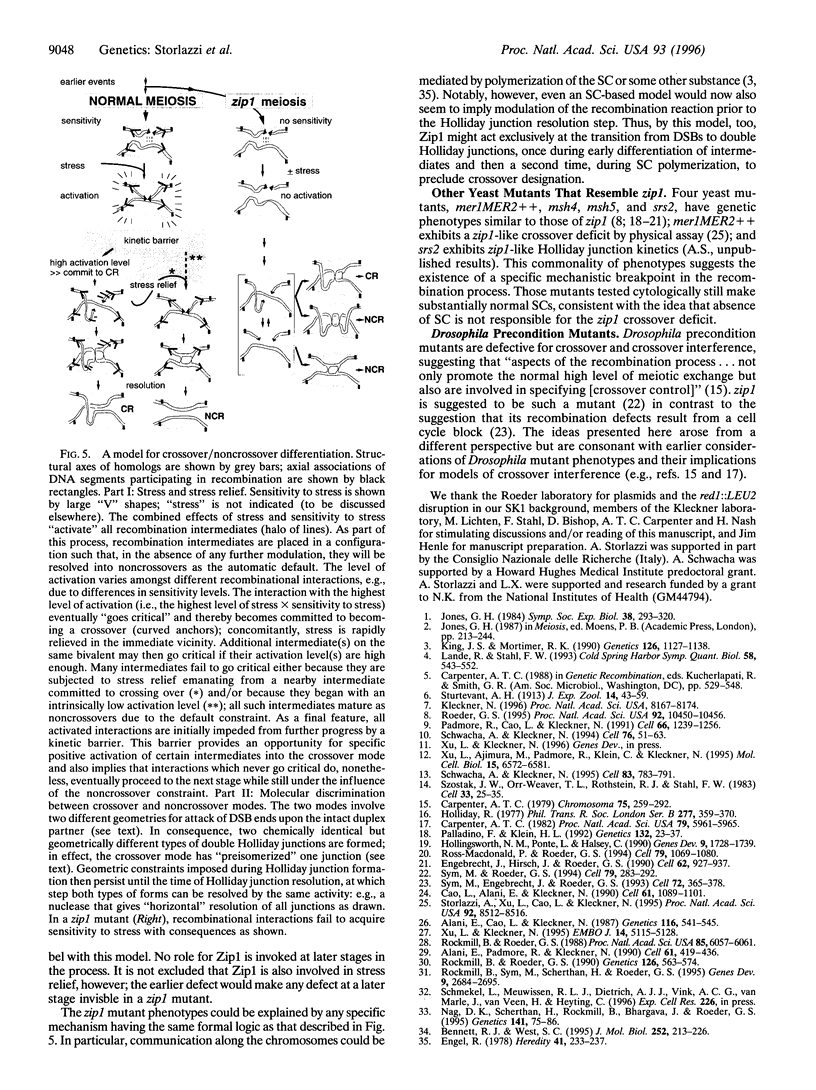

- Storlazzi A., Xu L., Cao L., Kleckner N. Crossover and noncrossover recombination during meiosis: timing and pathway relationships. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995 Aug 29;92(18):8512–8516. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.18.8512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sym M., Engebrecht J. A., Roeder G. S. ZIP1 is a synaptonemal complex protein required for meiotic chromosome synapsis. Cell. 1993 Feb 12;72(3):365–378. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90114-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sym M., Roeder G. S. Crossover interference is abolished in the absence of a synaptonemal complex protein. Cell. 1994 Oct 21;79(2):283–292. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90197-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szostak J. W., Orr-Weaver T. L., Rothstein R. J., Stahl F. W. The double-strand-break repair model for recombination. Cell. 1983 May;33(1):25–35. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(83)90331-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu L., Ajimura M., Padmore R., Klein C., Kleckner N. NDT80, a meiosis-specific gene required for exit from pachytene in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1995 Dec;15(12):6572–6581. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.12.6572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu L., Kleckner N. Sequence non-specific double-strand breaks and interhomolog interactions prior to double-strand break formation at a meiotic recombination hot spot in yeast. EMBO J. 1995 Oct 16;14(20):5115–5128. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb00194.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]