Abstract

The aim of this study was to determine the effect of azithromycin on LPS-induced pregnancy loss. Thirty-six pregnant female Wistar rats were divided into 4 equal groups as follows: control group, where 0.3 mL of normal saline solution was administered intravenously on day 10 of pregnancy; azithromycin group, where azithromycin was administered orally at 350 mg kg−1 day on days 9, 10, and 11 of pregnancy; lipopolysaccharide group, where LPS was administered intravenously via the tail vein at 160 μg kg−1 on day 10 of pregnancy; and the azithromycin + LPS group, where azithromycin was administered orally at 350 mg kg−1 day on days 9, 10, and 11 of pregnancy and LPS was administered intravenously at 160 μg kg−1 on day 10 of pregnancy. Blood samples were obtained from the tail vein on day 10 of the experiment. Pregnancy rates were determined. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) and interleukin (IL-10) levels were measured by ELISA. Azithromycin prevented (P < 0.05) LPS-induced pregnancy loss. Higher TNF-α and IL-10 levels were measured (P < 0.05) in the LPS and azithromycin + LPS groups, respectively. In conclusion, azithromycin may be useful in infection- or endotoxemia-dependent pregnancy loss.

1. Introduction

The maternal immune system is capable of recognizing and refusing a response against foetal antigens [1]. One of the most common unfavorable outcomes during the first trimester of pregnancy is spontaneous abortion; the rate of spontaneous abortion is 15%–20% in women [2]. However, the mechanisms underlying pregnancy loss caused by maternal infections are not clear [3].

Lipopolysaccharide (LPS), an endotoxin derived from gram negative bacteria, has been used to constitute inflammatory response in experimental studies with pregnancy. It is well known as a trigger of abortion and preterm birth via proinflammatory cytokines and nitric oxide [4–9]. The predominant production of T-helper (Th2) cytokines is a characteristic of normal pregnancy, while a predominant production of Th1 cytokines is a characteristic of abortion and recurrent abortion [10]. A change from a Th2-biased to a Th1-biased cytokine profile in maternal serum results in complications for pregnant women, such as spontaneous abortions and preeclampsia [11].

Besides the direct antimicrobial effect, macrolides also show anti-inflammatory properties [12]. Azithromycin has similar efficacy compared with erythromycin or amoxicillin; azithromycin also has fewer adverse effects in the treatment of pregnant women with Chlamydia trachomatis infections [13]. Because of this feature, using azithromycin to treat pregnant women with uncomplicated C. trachomatis infections is increasing amongst obstetricians [14]. Azithromycin is clinically effective in the treatment of common respiratory, skin/skin-structure infections, nongonococcal urethritis, and cervicitis due to C. trachomatis. Azithromycin is categorized as a class B drug during pregnancy [15].

The balance between tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) and interleukin (IL-10) is determined for pregnancy success. Whenever the level of TNF-α increases, abortion occurs, while IL-10 supports the pregnancy [10, 11]. Due to the inexistence of an adequate preventive treatment of early pregnancy loss, it has been hypothesized that azithromycin may prevent LPS-induced pregnancy loss because of an inhibitory effect on TNF-α and potentiating effect on IL-10.

The aim of this study was to determine the effect of azithromycin on LPS-induced pregnancy loss in rats.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animal

The study protocol was approved by the Ethical Committee of Necmettin Erbakan University, Experimental Medicine, Research and Application Center, Konya, Turkey. Thirty-six female and 9 male Wistar rats (272 ± 44.9 g and 306 ± 16.1 g, respectively, 5-6 months old) were used in this study. Rats were fed a standard pelleted diet and tap water was provided ad libitum as drinking water. Animals were bred in standard cages on a 12 hr light/dark cycle at room temperature in a humidity-controlled environment.

2.2. Experimental Procedure

LPS (Escherichia coli, serotype O111:B4, Sigma-Aldrich Chemie, Deisenhofen, Germany) and azithromycin (Zitromax, 200 mg/5 mL, oral suspension, Pfizer, Istanbul, Turkey) were diluted with pyrogen-free saline to appropriate concentrations.

Female rats were caged with males for 1 day and the presence of a vaginal plug was designated as day 0 of pregnancy. Tenth to 12th day in a rat's pregnancy corresponds roughly to the first trimester of human pregnancy [16]. Pregnant rats were randomly divided into 4 groups as follows: control group, where 0.3 mL of normal saline solution was administered intravenously on day 10 of pregnancy (n = 9); azithromycin group, where azithromycin was administered orally at 350 mg kg−1 day on days 9, 10, and 11 of pregnancy (n = 9); where LPS group, LPS was administered intravenously via the tail vein at 160 μg kg−1 on day 10 of pregnancy (n = 9); and the azithromycin + LPS group, where azithromycin was administered orally at 350 mg kg−1 day on days 9, 10, and 11 of pregnancy and LPS was administered intravenously at 160 μg kg−1 on day 10 of pregnancy (n = 9). Blood samples were obtained from the tail vein on day 10 of the experiment (3 hr after LPS administration) and all animals were followed during pregnancy. In addition, animals that did and did not give birth were determined. At the end of the study, all animals were euthanized under thiopental sodium anaesthesia (70 mg/kg, intraperitoneally; Pental Sodium 1 g inj., I. E. Ulagay Ilac Sanayi, Istanbul, Turkey).

2.3. Measurements

Samples were centrifuged and serum samples were stored at −70°C until analysis. TNF-α (eBioscience Rat TNF-α kit, sensitivity 11 pg/mL, San Diego, CA, USA) and IL-10 (eBioscience Rat IL-10kit, sensitivity 1.5 pg/mL, San Diego, CA, USA) levels were determined at 450 nm by commercial ELISA kits with ELISA reader (MWGt Lambda Scan 200, USA).

2.4. Statistical Analysis

The pregnancy rates of the groups were evaluated using a chi-square test, and the concentrations of TNF-α and IL-10 were compared with ANOVA and the Tukey test. Data are expressed as the mean ± SE. Number of offspring in each group was evaluated by ANOVA and Duncan test. Significance was accepted at the P < 0.05 level.

3. Results

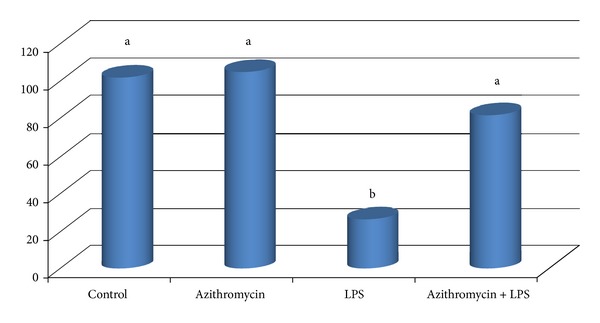

All animals were followed during pregnancy. The average weight of the rats was 272 ± 44.9 g before pregnancy and 375 ± 47.9 g at the end of pregnancy. Azithromycin inhibited (P < 0.05) LPS-induced pregnancy loss, and there were no adverse effects on the pregnancy rate (Table 1). The TNF-α level was higher (P < 0.05) in the LPS group, and the IL-10 levels were lower (P < 0.05) in the azithromycin and control groups (Table 2). In addition, the concentration of IL-10 in the azithromycin + LPS group was significantly higher (P < 0.05) than the other groups (Table 2). Offspring rate was statistically significant (P < 0.05) in LPS group when compared to all other groups (Figure 1).

Table 1.

Pregnancy rates of groups.

| Drug | Pregnant/pregnancy loss | Labour animals |

|---|---|---|

| Control | 9/0a | 9 |

| Azithromycin | 9/0a | 9 |

| LPS | 9/7b | 2 |

| Azithromycin + LPS | 9/2a | 7 |

LPS: lipopolysaccharide (160 µg kg−1 intravenously, Escherichia coli 0111:B4). a,bDifferent letters in the same column are statistically significant (P < 0.05).

Table 2.

TNFα and IL-10 levels of groups.

| TNFα (pg/mL) | IL-10 (pg/mL) | |

|---|---|---|

| Control | ND | 90.2 ± 4.31a |

| Azithromycin | 58.2 ± 9.56a | 113 ± 15.4a |

| LPS | 128 ± 10.7b | 496 ± 149b |

| Azithromycin + LPS | 96.6 ± 10.2c | 1130 ± 87.4c |

TNFα: tumor necrosis factor α; IL-10: interleukin-10; LPS: lipopolysaccharide (160 µg kg−1 intravenously, Escherichia coli 0111:B4). ND: not determined. a,b,cDifferent letters in the same column are statistically significant (P < 0.05).

Figure 1.

The number of offspring in groups. To induce the pregnancy loss with LPS, 160 μg kg−1 LPS (Escherichia coli 0111:B4) was administered intravenously via the tail vein on day 10 of pregnancy in LPS group. Azithromycin was administered orally at 350 mg kg−1 day on days 9, 10, and 11 of pregnancy in azithromycin and azithromycin + LPS groups. Blood samples were obtained from the tail vein on day 10 of the experiment and all animals were followed during pregnancy. Animals that did and did not give birth were determined. a,bDifferent letters are statistically significant (P < 0.05).

4. Comment

The aim of this study was to determine the effect of azithromycin on septic abortion. Many endogenous agents, such as prostaglandins or cytokines, play a pivotal role during pregnancy [10, 17]. Recurrent spontaneous abortion is classically defined as three or more pregnancy losses and usually occurs before 20 weeks of gestation. Recently, recurrent spontaneous abortion has been redefined as the spontaneous loss of two or more clinical pregnancies [18, 19]. Adverse pregnancy outcomes, such as spontaneous abortion, preterm labour, preeclampsia, and intrauterine growth restriction, can result from a deregulation of cytokines networks [20].

In the current study, azithromycin alone did not present a negative effect on the pregnancy rate (Table 1). It has been reported that the prophylactic use of azithromycin can decrease procedure-related pregnancy loss and may be safe in pregnant women [21, 22].

In the current study, higher pregnancy rates were determined in the control and azithromycin groups than in the LPS group (Table 1). In addition, a higher TNF-α level was measured in the LPS group (Table 2). The maternal immune response is determined for pregnancy success. Animal models have been used to elucidate this question. The mechanism underlying early pregnancy loss is associated with several inflammatory molecules; thus, modulation of the inflammatory modules is useful. Excessive inflammation may lead to unfavourable outcomes, such as spontaneous abortion and fetal resorption. Areas of implantation are extremely sensitive to LPS and Th1 cytokines (TNF-α and lL-2) during early pregnancy in mice. These molecules have the ability to induce embryonic resorption [3, 23, 24]. Low doses of LPS, without affecting mother survival, cause high rates of embryonic resorption during early pregnancy [3, 25]. Deregulation of cytokines networks results in adverse pregnancy outcomes [20]. Th2 cytokines, including IL-10, have a protective role, while Th1 cytokines, including TNF-α, are abortive factors in pregnancy [26]. Increased TNF-α levels caused by LPS resulted in insufficient placental perfusion, improvement of thrombotic events, and placental and fetal hypoxia [27]. In the current study, the LPS treatment increased TNF-α level, which determined a decrease in pregnancy rate. It has been reported that the LPS-increased TNF-α level is closely linked to recurrent pregnancy loss [28]. In another study, the concentration of LPS-binding protein in amniotic fluid was increased in patients who had a spontaneous fetal loss [29].

In the current study, azithromycin increased the pregnancy rate 3.5-fold when compared to the LPS group (Table 1). In addition, a higher IL-10 concentration occurred (P < 0.05) in the azithromycin + LPS group than those of the other groups, and the TNF-α level was lower (P < 0.05) in the azithromycin + LPS group than the LPS group (Table 2). Erythromycin and azithromycin are used in the treatment of endocervical chlamydial infections and mycoplasma pneumonia in obstetric patients [30]. Azithromycin may be more effective against endometrial infections because it provides important tissue levels for a long period [31]. Transplacental passage of azithromycin is limited, and azithromycin and other macrolide antibiotics are generally accepted to be safe in pregnancy [32, 33]. Increased pregnancy rates in the azithromycin + LPS group (Table 1) may reflect the depressive effect of macrolides on proinflammatory cytokines production and the potentiating effect on the IL-10 level. The suppressive effects of macrolides, including azithromycin, on the TNF-α level and the potentiating effects of these drugs on the IL-10 level have been reported [31, 34, 35]. Moreover, IL-10 injections prevent LPS-induced abortions and decrease LPS-induced fetal death [6, 27].

In conclusion, infection- or endotoxemia-mediated pregnancy loss may be prevented by using azithromycin during the pregnancy period.

Conflict of Interests

The author declares that there is no conflict of interests.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Dr. Enver YAZAR and Dr. Ibrahim AYDIN for the scientific assistance.

References

- 1.Thellin O, Coumans B, Zorzi W, Igout A, Heinen E. Tolerance to the foeto-placental “graft”: ten ways to support a child for nine months. Current Opinion in Immunology. 2000;12(6):731–737. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(00)00170-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Friebe A, Arck P. Causes for spontaneous abortion: what the bugs “gut” to do with it? International Journal of Biochemistry & Cell Biology. 2008;40(11):2348–2352. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2008.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aisemberg J, Vercelli C, Wolfson M, et al. Inflammatory agents involved in septic miscarriage. NeuroImmunoModulation. 2010;17(3):150–152. doi: 10.1159/000258710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Murphy SP, Sharma S. IL-10 and pregnancy. In: Mor G, editor. Immunology of Pregnancy. 2006. pp. 26–36. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Xu D-X, Chen Y-H, Wang H, Zhao L, Wang J-P, Wei W. Tumor necrosis factor alpha partially contributes to lipopolysaccharide-induced intra-uterine fetal growth restriction and skeletal development retardation in mice. Toxicology Letters. 2006;163(1):20–29. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2005.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Robertson SA, Care AS, Skinner RJ. Interleukin 10 regulates inflammatory cytokine synthesis to protect against lipopolysaccharide-induced abortion and fetal growth restriction in mice. Biology of Reproduction. 2007;76(5):738–748. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.106.056143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Holmgren C, Esplin MS, Hamblin S, Molenda M, Simonsen S, Silver R. Evaluation of the use of anti-TNF-α in an LPS-induced murine model. Journal of Reproductive Immunology. 2008;78(2):134–139. doi: 10.1016/j.jri.2007.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cella M, Farina MG, Dominguez Rubio AP, Di Girolamo G, Ribeiro ML, Franchi AM. Dual effect of nitric oxide on uterine prostaglandin synthesis in a murine model of preterm labour. British Journal of Pharmacology. 2010;161(4):844–855. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.00911.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tuzun F, Kumral A, Dilek M, et al. Maternal omega-3 fatty acid supplementation protects against lipopolysaccharide-induced white matter injury in the neonatal rat brain. The Journal of Maternal-Fetal and Neonatal Medicine. 2012;25(6):849–854. doi: 10.3109/14767058.2011.587917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Christiansen OB, Nielsen HS, Kolte AM. Inflammation and miscarriage. Seminars in Fetal and Neonatal Medicine. 2006;11(5):302–308. doi: 10.1016/j.siny.2006.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Trowsdale J, Betz AG. Mother’s little helpers: mechanisms of maternal-fetal tolerance. Nature Immunology. 2006;7(3):241–246. doi: 10.1038/ni1317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Er A, Yazar E. Effects of tylosin, tilmicosin and tulathromycin on inflammatory mediators in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid of lipopolysaccharide-induced lung injury. Acta Veterinaria Hungarica. 2012;60:465–476. doi: 10.1556/AVet.2012.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pitsouni E, Iavazzo C, Athanasiou S, Falagas ME. Single-dose azithromycin versus erythromycin or amoxicillin for Chlamydia trachomatis infection during pregnancy: a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents. 2007;30(3):213–221. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2007.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Adimora AA. Treatment of uncomplicated genital Chlamydia trachomatis infections in adults. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2002;35(2):S183–S186. doi: 10.1086/342105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Amsden GW. Erythromycin, clarithromycin, and azithromycin: are the differences real? Clinical Therapeutics. 1996;18(1):56–72. doi: 10.1016/s0149-2918(96)80179-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rothberg H. Effects of cytotoxic agents on the fetus. JAMA. 1960;173(14):p. 1616. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fetalvero KM, Zhang P, Shyu M, et al. Prostacyclin primes pregnant human myometrium for an enhanced contractile response in parturition. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2008;118(12):3966–3979. doi: 10.1172/JCI33800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jauniaux E, Farquharson RG, Christiansen OB, Exalto N. Evidence-based guidelines for the investigation and medical treatment of recurrent miscarriage. Human Reproduction. 2006;21(9):2216–2222. doi: 10.1093/humrep/del150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zegers-Hochschild F, Adamson GD, De Mouzon J, et al. The International Committee for Monitoring Assisted Reproductive Technology (ICMART) and the World Health Organization (WHO) Revised Glossary on ART Terminology, 2009. Human Reproduction. 2009;24(11):2683–2687. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dep343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Challis JR, Lockwood CJ, Myatt L, Norman JE, Strauss JF, III, Petraglia F. Inflammation and pregnancy. Reproductive Sciences. 2009;16(2):206–215. doi: 10.1177/1933719108329095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wilton LV, Pearce GL, Martin RM, Mackay FJ, Mann RD. The outcomes of pregnancy in women exposed to newly marketed drugs in general practice in England. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1998;105(8):882–889. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1998.tb10234.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Giorlandino C, Cignini P, Cini M, et al. Antibiotic prophylaxis before second-trimester genetic amniocentesis (APGA): a single-centre open randomised controlled trial. Prenatal Diagnosis. 2009;29(6):606–612. doi: 10.1002/pd.2256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Laird SM, Tuckerman EM, Cork BA, Linjawi S, Blakemore AIF, Li TC. A review of immune cells and molecules in women with recurrent miscarriage. Human Reproduction Update. 2003;9(2):163–174. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmg013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mitchell BF, Taggart MJ. Are animal models relevant to key aspects of human parturition? American Journal of Physiology. 2009;297(3):R525–R545. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00153.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li L, Yang J, Ren L, Su N, Fang Y, Lin Y. Invariant NKT cells increase lipopolysacchride-induced pregnancy loss by a mechanism involving Th1 and Th17 responses. Journal of Maternal-Fetal and Neonatal Medicine. 2013;26:1212–1218. doi: 10.3109/14767058.2013.773307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chaouat G, Zourbas S, Ostojic S, et al. A brief review of recent data on some cytokine expressions at the materno-foetal interface which might challenge the classical Th1/Th2 dichotomy. Journal of Reproductive Immunology. 2002;53(1-2):241–256. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0378(01)00119-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Renaud SJ, Cotechini T, Quirt JS, Macdonald-Goodfellow SK, Othman M, Graham CH. Spontaneous pregnancy loss mediated by abnormal maternal inflammation in rats is linked to deficient uteroplacental perfusion. Journal of Immunology. 2011;186(3):1799–1808. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1002679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gendron RL, Nestel FP, Lapp WS, Baines MG. Lipopolysaccharide-induced fetal resorption in mice is associated with the intrauterine production of tumour necrosis factor-alpha. Journal of Reproduction and Fertility. 1990;90(2):395–402. doi: 10.1530/jrf.0.0900395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Espinoza J, Romero R, Chaiworapongsa T, et al. Lipopolysaccharide-binding protein in microbial invasion of the amniotic cavity and human parturition. Journal of Maternal-Fetal and Neonatal Medicine. 2002;12(5):313–321. doi: 10.1080/jmf.12.5.313.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Duff P. Antibiotic selection in obstetric patients. Infectious Disease Clinics of North America. 1997;11(1):1–12. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5520(05)70338-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gray RH, Wabwire-Mangen F, Kigozi G, et al. Randomized trial of presumptive sexually transmitted disease therapy during pregnancy in Rakai, Uganda. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2001;185(5):1209–1217. doi: 10.1067/mob.2001.118158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Heikkinen T, Laine K, Neuvonen PJ, Ekblad U. The transplacental transfer of the macrolide antibiotics erythromycin, roxithromycin and azithromycin. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2000;107(6):770–775. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2000.tb13339.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sarkar M, Woodland C, Koren G, Einarson ARN. Pregnancy outcome following gestational exposure to azithromycin. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. 2006;6, article 18 doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-6-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lin S-J, Yan D-C, Lee W-I, Kuo M-L, Hsiao H-S, Lee P-Y. Effect of azithromycin on natural killer cell function. International Immunopharmacology. 2012;13(1):8–14. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2012.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vrančić M, Banjanac M, Nujić K, et al. Azithromycin distinctively modulates classical activation of human monocytes in vitro. British Journal of Pharmacology. 2012;165(5):1348–1360. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01576.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]