SUMMARY

This article provides a description of a Community/University Collaborative Board, a formalized partnership between representatives from an inner-city community and university-based researchers. This Collaborative Board oversees a number of research projects focused on designing, delivering and testing family-based HIV prevention and mental health focused programs to elementary and junior high school age youth and their families. The Collaborative Board consists of urban parents, school staff members, representatives from community-based agencies and university-based researchers. One research project, the CHAMP (Collaborative HIV prevention and Adolescent Mental health Project) Family Program Study, an urban, family-based HIV prevention project will be used to illustrate how the Collaborative Board oversees a community-based research study. The process of establishing a Collaborative Board, recruiting members and developing subcommittees is described within this article. Examples of specific issues addressed by the Collaborative Board within its subcommittees, Implementation, Finance, Welcome, Research, Grant writing, Curriculum, and Leadership, are detailed in this article along with lessons learned.

Keywords: Community collaborative board, family-based HIV prevention and mental health, community board recruitment and development, elementary and junior high school age youth and their families

Collaboration with key community constituents has been described as necessary to: (1) enhance relevance of research questions; (2) develop research procedures that are acceptable to potential participants; (3) address obstacles to conducting community-based research activities; (4) maximize usefulness of research findings; and (5) expand community-level resources to sustain youth-focused intervention and prevention programs beyond research or demonstration funding (Israel, Schulz, Parker & Becker, 1998; Institute of Medicine, 1998; Schensul, 1999; Trickett, Hoagwood & Jensen, 1999; Wandersman, 2003). The urgency to increase collaborative participatory research efforts has been logically associated with pressing public health epidemics (National Institute of Mental Health, 1998). The AIDS epidemic, now entering its third decade, is an example of a serious public health issue which has mobilized prevention scientists, health and mental health care providers and community members to come together and collaborate in an effort to decrease rates of infection.

Over the last three decades, the focus of HIV prevention collaborations has shifted. This shift has followed the demographic changes of the epidemic as it began to penetrate ethnic minority communities and particularly impact young people. This article, therefore, focuses on adolescent HIV preventative research efforts as teenagers, particularly urban youth of color, are among the fastest growing populations at risk for HIV infection (Center for Disease Control, 2001; 2000; 1998).

Adolescents now account for more than 25% of all sexually transmitted diseases reported annually. Young females and minority youth are disproportionately affected by STDs and HIV infections (Centers for Disease Control, 2000; 1998; DiLorenzo & Hein, 1993; Jemmott & Jemmott, 1992). Over the last ten years, the incidence of HIV infection has raised dramatically in low income, ethnic minority neighborhoods. African American and Latino youth are over represented among those living in urban, poor neighborhoods, which increase their likelihood of exposure to HIV and other sexual transmitted disease. The likelihood of exposure for sexually active youth relates to higher overall rates of neighborhood HIV prevalence, along with poorer access to preventive health care, early detection and treatment services (Centers for Disease Control, 2001; Institute of Medicine, 1997; Miller, Clark, & Moore, 1997; Minnis & Padian, 2001; Rotheram-Borus, Mahler & Rosario, 1995; Wilson, 1987).

Prevention scientists have developed and tested a number of sexual risk reduction and STD and HIV prevention programs targeting urban minority youth (Forehand, Miller, Armistead, Kotchick, & Long, 2003; Kirby, Short, Collins, Rugg, Kolbe, Howard, Miller, Sonenstein, & Zahan, 1994; Jemmott, Jemmott & Fong, 1997). The Centers for Disease Control has published a compendium of such evidence-based programs in an attempt to more widely disseminate needed prevention services to urban youth (Centers for Disease Control, 2001). However, efforts to transport empirically supported prevention programs have encountered numerous obstacles, including insufficient school-based resources, poor community participation and tensions or suspicions between community residents and outside researchers (Dalton, 1989; Galbraith, Stanton, Feigelman, Ricardo, Black & Kalijee, 1996; Thomas & Quinn, 1991).

As a result, it is becoming clear that community-based HIV prevention programs targeting urban youth of color are likely to fail if they attempt to provide interventions in a non-collaborative manner (Aponte, 1988; Boyd-Franklin, 1993; Fullilove & Fullilove, 1993; Secrest, Lassiter, Armistead, Wychoff, Johnson, Williams, & Kotchick, 2004; Fullilove, Green, & Fulliove, 2000; Schensul, 1999) or neglect to design and implement programs that do not take into account the stressors, scarce contextual resources or target groups’ core values (Boyd-Franklin, 1993; McLoyd, 1990; Sanstad, Stall, Goldstein, Everett, & Brousseau, 1999). Therefore, the establishment of strong community partnerships to support health prevention efforts is critical. Meaningful community participation enhances the chances that: (1) effective adolescent sexual risk prevention programs will be well received within urban communities; (2) programs can be sustained after federal funding and research has ended; and (3) greater efficacy might be achieved if target communities are involved in all phases of development and delivery of the program.

Below we provide a description a Community/University Collaborative Board, a formalized partnership between representatives from inner-city communities and university-based researchers currently in operation in Chicago and New York. These Collaborative Boards oversee a number of research projects focused on designing, delivering and testing family-based prevention and intervention services for elementary and junior high school age urban youth and their families. Each Collaborative Board consists of urban parents, school staff members, representatives from community-based agencies and university-based researchers. One research project overseen by the Board, the CHAMP (Collaborative HIV prevention and Adolescent Mental health Project) Family Program Study will be used as an example of how key stakeholders in the community are involved in every step of the research process, thereby, building further capacity for future prevention research oriented collaborations and community-level leadership (for a description see Paikoff, McKay & Bell, 1994; McKay, Paikoff, Bell, Madison & Baptiste, 2000).

In addition, we describe the role of the Collaborative Board in seeking additional funding for youth and family-focused programs and research studies, implementing the family-based program, overseeing research activities and disseminating findings. The process of establishing a Collaborative Board, recruiting Board members and developing task-oriented subcommittees is also described below. Examples of specific issues addressed by the Collaborative Board subcommittees (which are: Implementation, Finance, Welcome, Research, Grant writing, Curriculum and Leadership) are detailed in this article along with lessons learned.

ROLE OF COMMUNITY COLLABORATION IN HIV/AIDS PREVENTION RESEARCH

Prevention programs designed to increase health protective behavior in adolescents must be culturally sensitive (Weeks, Schensul, Williams, Singer, 1995) and also address developmental processes, specific reinforcers of risk behavior, relevant contextual factors, and a population’s unique risk-profile (Brown & DiClemente, 1992). Given the nature of the behavioral changes that need to be made to avoid HIV infection, HIV prevention programs are often controversial. Minority communities, and in particular the African American community, have histories of mistrust regarding involvement with outsiders representing the government in research or programs aimed at improving health. Experience with projects such as the Tuskegee Syphilis Study, which deliberately misled African Americans in order to continue to study naturalistically a health problem for which a cure was available, have fueled misgiving regarding health promotion and prevention projects within communities of color (Madison, Bell et al.,; Stevenson et al., 1995; Thomas & Quinn, 1991; Dalton, 1989).

Given this history of mistrust, the importance of working with community members in the design, delivery and testing of youth-focused prevention research efforts has been stressed, especially those directed at reducing HIV risk behaviors. (Hatch, Moss, Saran, Presley-Cantrell, & Mallory, 1993; Eccles, 1996; Farhall, Webster et al., 1998; Stevenson & White, 1994). In order to guide prevention research efforts, a theoretical paradigm has been proposed. This model identifies four models of community collaboration ranging from community members involved as: (1) advice or consent givers; (2) gate keepers and endorsers of the research; (3) deliverers of research or programs (e.g., front line staff); and (4) active participants in the direction and focus of the research (Hatch et al., 1993). This fourth level has been considered ideal for research and program delivery in under-served, low-income minority communities. Over time, through constitution of the Collaborative Board, the degree of collaboration around the design, delivery and testing of the CHAMP Family Program has increased to this fourth level, reflected in the significant role key community members play in the direction, leadership and testing and dissemination of findings discussed below (Madison, Bell et al., in press; Madison, McKay et al., 2000; McKay, Baptiste et al., 2000; McKay, Chase et al., 2004).

THE CHAMP FAMILY PROGRAM

The CHAMP Family Program, funded by the National Institute of Mental Health since 1995, was designed to impact three interrelated outcomes for pre and early adolescent youth: (1) decrease time spent in situations of sexual possibility; (2) delay initiation of sexual activity; and (3) reduce sexual risk taking behavior. The program was designed specifically to address the prevention needs of urban youth of color living in communities with high rates of HIV infection (see McKay, Baptiste et al., 2000; Madison, McKay et al., 2000; McKay, Chase et al., 2004 for a detailed descriptions of this program).

More specifically, the CHAMP Family program targets 4th and 5th grade youth (9 to 11 years of age) and their families. The program is developmentally timed to involve youth prior to the onset of sexual activity, but close to the beginning of early adolescence when initiation of sexual activity occurs for many youth. CHAMP also has adopted a family-based approach to support families, enhance family protective processes and bolster parenting skills as urban families attempt to rear children in urban environments where risks and psychosocial stressors are often elevated. The CHAMP Family Program study was also designed to address some of the serious difficulties that prior HIV prevention research efforts had encountered within urban communities, particularly low rates of participation, community misgivings about the appropriateness of HIV prevention programs for children and mistrust of program and project staff. Thus, a strong community collaborative research method was employed by investigators of the CHAMP Family Program study that draws upon key elements of participatory research paradigms (Israel et al., 1998).

COMMUNITY PARTICIPATORY RESEARCH

A range of descriptions and definitions of participatory or community collaborative research have been offered (Altman, 1995; Arnstein, 1969; Chavis, Stucky, & Wandersman, 1983; Singer, 1993; Israel et al., 1998). There is agreement on some central themes and core foundational principles of participatory research efforts. On the most basic level, participatory research has been described as “providing direct benefit to participants either through direct intervention or by using the results to inform action for change” (Israel, Schulz, Parker, & Becker, 1998, p. 175). Further, what distinguishes community collaborative research from other investigative approaches is the emphasis on the intensive and ongoing participation and influence of community members in building knowledge (Israel et al., 1998). Research questions that result from collaboration between researchers and community members tend to reflect the pressing concerns of community members, acknowledge the importance of indigenous knowledge and resources, rather than over relying on expertise brought by the university partner (Institute of Medicine, 1998; Minkler & Wallerstein, 2003; Secrest et al., 2004; Schensul, 1999; Stringer, 1996).

In sum, community collaborative research activities are defined by: (1) a recognition that community development must be a focus of research activities; (2) a commitment to build upon the strengths and resources of individual communities; (3) ongoing attention to involvement of all members of the collaborative partnership across phases of a research project; (4) an integration of knowledge and action for mutual benefit of all partners; (5) the promotion of a process that actively addresses social inequalities; (6) opportunities for feedback; (7) a commitment to addressing health problems from both a strength and an ecological perspectives and; (8) dissemination of findings and knowledge gained to all partners” (Israel et al., 1998; pp. 178-179). The CHAMP Family Program Study was guided by these principles of community participatory research and translated them into action via steps detailed next. A summary of these principles in action is provided (on page 158). Each phase of the research process from the design of the intervention, to the development of research procedures including data collection and recruitment/retention strategies, was viewed as an opportunity to identify mechanisms for maximum participation by community members.

OPPORTUNITIES FOR COLLABORATION ACROSS THE RESEARCH PROCESS

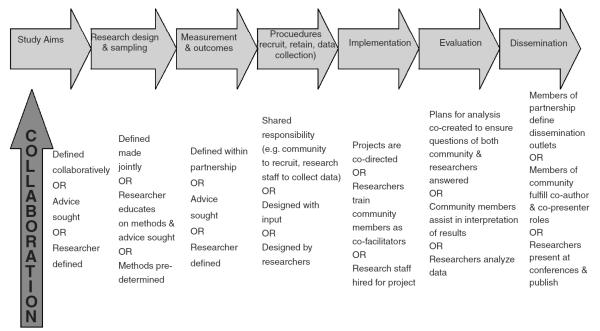

Although one of the core tenants of community participatory research is the involvement of key community stakeholders in every aspect of the research process, there have been few systematic attempts to identify the choices available to community/research partnerships throughout a given research project that would make this recommendation a reality. McKay and colleagues (Madison, McKay et al., 2000; McKay, in press) have identified a range of concrete opportunities to collaborate and conceptualized possible levels of intensity during each research phase based upon prior work of Hatch et al. (1993). This model of collaboration across the research process is represented in Figure 1 and incorporates key aspects of a paradigm conceptualize by Hatch et al., 1993.

FIGURE 1.

Collaborating Across the Research Process

Low-intensity collaborations. Hatch and colleagues propose that initial collaborative efforts often begin with a relatively less intense form of collaboration whereby researchers consult with persons, either for advice or consent, representing agencies or institutions within a specific community. At the next stage of collaboration, researchers identify key informants from the community (e.g., representatives from churches, business, etc.) and seek acceptance of the research project. Although this group of key informants is considered to be representative of community stakeholders, the research agenda and therefore, the decision-making power remains with the researcher. As collaboration proceeds, influential community leaders might be sought out by investigators to provide advice and guidance at a particular point in a research study. Often they are asked to sit on ongoing advisory boards. Further, their assistance is actively sought so that community members can be hired by the project as paid staff and fill positions, such as interviewers or recruiters.

Moderate to high intensity collaboration characterizes the current CHAMP Community Collaborative Board structure. Hatch and colleagues (1993) indicate that although additional input is sought as collaborative efforts intensify, key decisions regarding who has ultimate control about research questions and decisions regarding research methods, procedures and interpretation of study results are critical. At the highest level of collaboration, the research partners, from both the university and community, work together to develop the focus of the research and an action agenda. Then, all partners are responsible for pursuing these shared goals. At the most intense level of collaboration, there is true partnership between community and university. The decision-making process is therefore a shared enterprise that recognizes the specific talents of both university and community members.

As indicated in Figure 1, researchers and community members can collaborate during all phases of the research process. For example, collaborative partnerships meant to increase recruitment and retention in youth-focused prevention research projects might develop strategies such as incorporating consumers as paid staff or community members as interviewers or recruiters. These community representatives can fulfill liaison roles between youth and families in need and prevention programs (Elliott et al., 1998; Koroloff et al., 1994; McCormick et al., 2000). In some cases, consumers are the first contact that a youth or adult caregiver has with a specific prevention project. This is the case within the CHAMP Family Program where community parent facilitators are trained to reach out to their neighbors and invite them to learn more about the program. As part of the training of CHAMP parent facilitators, they and their children have actually participated in the program. Thus, in addition to being able to provide information about the program to potential participants, CHAMP parent facilitators are also able to use personal, first hand experience to answer any questions that participants may have or address any concerns raised (see McCormick, McKay et al., for a detailed description of CHAMP parent facilitator recruitment efforts).

As one moves to the right in Figure 1, community/university partnerships can also focus on facilitating the implementation of prevention approaches. For example, preventative interventions can be delivered by “naturally existing community resources,” such as teachers (Atkins, McKay et al., 1998) and/or parents (McKay et al., 2000). In the case of the CHAMP Family Program, each of the intervention sessions is co-facilitated by a mental health intern/parent facilitator team. All CHAMP facilitators, those with a mental health background and community parents, receive weekly joint training in the content of the CHAMP Family Program, in skills related to facilitation of child, parent and multiple family groups, in issues related to prevention research efforts and in protection of human subjects, including confidentiality and addressing mandated safety issues.

PROCESS OF ESTABLISHING A COMMUNITY/UNIVERSITY COLLABORATIVE BOARD

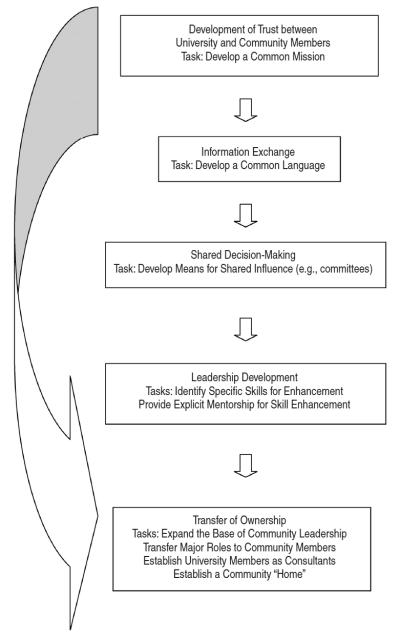

In 1995, the National Institute of Mental Health supported the development of the first Collaborative Board to guide the development, de-livery and testing of a family-based HIV prevention program in an innercity community with high rates of HIV infection. Thus, the first Collaborative Board was initially organized to consist of 15 to 25 members representing key stakeholders, parent community, partner schools, community-based youth-serving agencies and university-based researchers. This first Collaborative Board was initially organized to meet once per month, however, as the project evolved over time, some of the Boards in other sites began to meet two times per month. Each Collaborative Board member is compensated for their time either via stipends for each meeting attended or by employment as a staff member as part of the CHAMP Family Program study. Through the workings of the first Collaborative Board, the following conceptual model of Board development was defined and fine tuned (for additional details see Madison et al., 1995; Madison, McKay et al., 2000). Figure 2 summarizes the steps taken to formalize the partnership among members of the community, urban parents, school and community-based agency staff and university-based researchers.

FIGURE 2.

A Model of the Development of Collaborative Partnerships: Stages and Tasks

First, the development of relationships between university-based researchers and community partners is based upon the building of trust. A major task in the initial stage of collaboration is the establishment of a mission statement that addresses all parties’ visions for the collaborative work and serves as a guide for future work. The mission statement of the first Collaborative Board organized in Chicago is provided in Table 1 (Madison, McKay et al., 2000; McKay, Baptiste et al., 2000).

TABLE 1.

CHAMP Family Program Mission Statement

| (1) We are committed to preventing families and children from getting HIV/AIDS. |

| (2) We will not exploit communities in the process. We are doing research with and for communities, not to communities. |

| (3) We want to increase communities’ understanding of how research can be used against them so that they can protect themselves. |

| (4) We want to increase communities’ understanding of the strengths within their communities. |

| (5) If a community likes the program, the research staff will help the community find ways to continue the program on its own. |

The second stage of collaboration concerns the exchange of information. A major task in this phase of the partnership is the development of a common language that facilitates communication between university and community partners. For community members, immersion in the project helps further their understanding of the research, while for university members, immersion in the community aids in their understanding of the context of the work. The third stage of partnership involves shared decision making. In this stage, the task is to share influence, such that multiple stakeholders are involved in determining the direction of the work.

Organizationally, the use of committees facilitates the sharing of decision-making and power. The following committees exist within the current Community Collaborative Board: Implementation, Finance, Welcome, Research, Grant writing, Curriculum and Leadership. More specifically, the Implementation Committee consists of representatives from the community, youth serving agencies, members of the university-based research team and the Principal Investigator of the CHAMP Family Program Study. The Implementation Committee functions similar to that of a personnel committee or an overarching policy and procedures committee for the project. For example, this is the committee that interviews all candidates for employment as staff for the project. Committee members have developed a standard set of interview questions, application procedures and criteria for selection to ensure that suitable candidates are hired as project directors, research assistants and program facilitators. On the rare occasion that an employee is not performing tasks appropriately, it is also this Implementation Committee that meets with the employee and makes a decision as to whether to develop a remedial plan or terminate employment. The key to the success of the Implementation Committee in collaborative research projects is that community representatives are an important part of this decision making, thus increasing the perception of sensitivity and fairness by all.

The Welcome Committee was organized somewhat later in the process of establishing the Collaborative Board. Its primary responsibilities focus on orienting new members joining the Board. The Welcome Committee has developed a set of standard procedures and materials to assist new Board members in learning about: (1) the project; (2) HIV prevention; (3) organization of the Board; (4) mission of the Board; and (5) Board by-laws and CHAMP Family Program study policy and procedure manual. In addition, a member of the Welcome Committee serves as a mentor to a new Board member for the first six months of the new persons’ involvement. The mentor provides opportunities to answer ongoing questions and support the integration of the new member into the social fabric of the Collaborative Board.

The Research Committee was organized to review: (1) research procedure used throughout the project, including recruitment or data collection procedures, and selection of measures; (2) progress of datacollection and entry; (3) preliminary analyses; and (4) proposed presentations and publications of findings. The Research Committee also reviews all manuscripts, including this one, and approves each paper for presentation at a full Board meeting.

In preparation for involvement in the Research Committee, each member took an introductory research methods seminar that was that was facilitated by one of the University-based staff members over an 8-week period. This research seminar focused on: (1) formulating research questions; (2) generating testable hypotheses; (3) reading and reviewing the literature; (4) strengths/challenges of research designs; (5) available sampling strategies; and (6) conceptual description of data analytic approaches.

The Grant Writing Committee was established to seek research and services funding in order to plan for sustainability of innovations focused on youth and families within the community. During the initial phase of formation, members reviewed all aspects of funding process, from development of proposal narratives, to preparation of budgets, to the process of submission. Over time, committee members accepted increasing levels of responsibility, including reviewing literature, writing text, preparing draft budgets, obtaining letters of support and making contact with potential funders. This process lead to the successful funding of additional tests of family-based interventions, including those focused on substance abuse prevention, reduction of community violence exposure and child mental health.

Next, the Curriculum committee, again consisting of representatives from the parent community, agency and school representatives and university-based research staff, is responsible for developing the content of the family-based interventions and preparing intervention protocols to be used in training program facilitators and guiding program delivery. The development of curriculum is conducted in the following steps: (1) existing literature and programs are reviewed by the Curriculum committee; (2) an outline of key intervention targets are identified; (3) each session of the program is then written; (4) a first pilot test with families recruited from the community involved as both program participants and also consultants to the Curriculum committee is conducted; (5) revisions to the program are made based upon feedback obtained from the first pilot test; (6) a second pilot test of the program is conducted with new participants recruited from the community; and finally (7) members of the Curriculum committee and their preadolescent children participate in the final pilot test of the program to experience, first hand, the process and impact of the program and provide the opportunity to give the program a “community stamp of approval.”

Another example of a Collaborative Board subcommittee is the Finance Committee. This subset of Collaborative Board members are responsible for three primary tasks: (1) overseeing and managing grant funding throughout the course of the project; (2) planning future expenditures and targets for fund raising; and (3) preparing and planning of budgets for new proposals. The Finance Committee is comprised of the Principal Investigator, the financial officer from one of the community-based organizations, the community coordinator and five community parent representatives. Early in the formation of the Finance Committee, the community-based finance officer organized a series of seminars for the committee members that focused on bolstering necessary skills. These seminars focused on: (1) reading financial statements; (2) understanding direct and indirect costs, fringe benefits, personnel and other than personnel expenses; (3) creating spread sheets to track expenditures; and (4) budget planning and completion of budget forms.

Finally, the Leadership Committee is responsible for the training and skill development of the Collaborative Board members. The main tasks of the Leadership Committee include: (1) identifying the skills needed to deliver the intervention and explicitly enhancing those skills through mentoring and training; and (2) supporting the personal development of Board members via identifying needed job training or educational opportunities. In addition, the Leadership Committee developed their own workshops or hired resources from the community to provide seminars. An example of one of the workshops organized is based on the book titled, Who Moved My Cheese?, by Spencer Johnson, M.D., which focused on helping Board members incorporate change at work and in life.

It is through these subcommittees that authentic decision making power and direction of the research project are shared among researchers and community members. Further, experiences within these subcommittees are meant to provide the opportunity for skill advancement and learning in order to prepare urban community representatives for future prevention oriented research projects and for ensuring the sustainability of programs like the CHAMP Family Program once research funding has ended. These set of opportunities is meant to prepare Collaborative Board members for the ultimate model of collaboration identified by Hatch and colleagues (1993).

Finally, the penultimate stage of university-community collaborative partnerships concerns leadership development (which is being enhanced by larger Board meetings and the committee work described in the preceding paragraph). The outcome of this stage of collaboration is the planning for sustaining of the program within a community-based organization once research or demonstration funding has ended. This planning for community transfer began several years prior to the ending of federal funding (see Madison et al., in press for a description of issues related to transfer of the CHAMP Family Program to community leadership). In sum, the organizational structure of the Board via regular full Board meetings and subcommittee work are key to putting participatory research principles into action (see summary in Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Participatory Research Principles to Action in CHAMP

| (1) Community development is a focus | Leadership Committee of Board; regular content training (e.g., information about HIV/AIDS, prevention research) and consistent opportunities for personal/professional development (e.g., communication and conflict resolution skill building). |

| (2) Builds on strengths of community | The entire project is guided by the premise that youth are at contextual risk for HIV exposure (e.g., living in a high HIV infection rate community) rather than youth or families being presumed to evidence specific individual risk factors, thus a strength-presumed, primary prevention approach has been adapted. |

| (3) Involvement of all members in each phase of the project |

Board members are involved in defining project goals and research procedures; overseeing implementation; and dissemination of findings. |

| (4) Providing direct benefits to participants | Training, opportunities for skill and personal development for Board members. |

| (5) Promotion of a process that actively addresses social inequalities |

Care has been taken to achieve salary equity in key project staff roles (e.g., project is co-directed by a university-trained staff member and talented community member, co-facilitators, parents and mental health interns, are paid exactly the same). |

| (6) Opportunities for feedback | The full CHAMP Collaborative Board meets one or two times per month, subcommittees meet frequently across each week, all members participate in a full day-day retreat at least once a year. |

| (7) Commitment to addressing heath problems from an ecological perspective |

The CHAMP Family Program Study targets individual child and adult caregiver skills, family-level processes and community resources to meet the prevention needs of inner- city youth. |

| (8) Disseminating findings and knowledge gained to all partners. |

CHAMP academic and community partners are responsible for co-presenting findings at research meetings, provider and community- oriented forums, community partners serve as co-authors on peer reviewed, newsletters and book chapter publications. |

RECRUITING COLLABORATIVE BOARD MEMBERS

Recruitment of Collaborative Board members takes place in distinct phases with the goal of achieving representation of different segments of the target community, particularly underrepresented portions of the community. More specifically, in each city that a Collaborative Board was formed, urban parents who were involved in school related activities or who were employed at the school were likely to be tapped as initial members. For example, representatives of elementary or junior high schools’ Parent Association were approached to become members of the Board. In addition, key youth-service agencies in the community were identified. Meetings with the executive director of these community-based organizations generally yielded the identification of a representative to attend Collaborative Board meetings. Once a core group of Board members had been identified, then a question posed at a Collaborative Board meeting was, “who is in this community that is not represented here?” For example, within the New York Collaborative Board, initially identified members were 60% African American and 40% Latino. Yet, the community targeted for the CHAMP Family Program was estimated to include at Latino population that made up 67% of the neighborhood. Thus, recruitment of additional Latino representatives was prioritized.

In addition, within the New York community, an influx of immigrants from Africa were arriving. Efforts to reach out and find representatives for these newly arriving groups of families was also made a priority for the Collaborative Board. Thus, in each of the sites, recruitment of a full complement of Board members took place over time, as long as 12 months, and increasingly was guided by identifying all segments of the community, not just those represented by parents who were easily accessible.

LESSONS LEARNED AND IMPLICATIONS FOR FUTURE COLLABORATIVE EFFORT

The formation and ongoing attention to a collaborative partnership between researchers and community members requires significant time, attention and care by all partners. If the partnership is to be genuine in that consensus is strived for, decisions are shared and input is sought at every phase of research activities, then continual opportunities for communication, forums for discussions and mechanisms to solve differences must be available.

In order to accomplish a true partnership among university-based researchers and community constituents, both researchers and community members must consider change in their attitudes and behavior. For example, community stakeholders must have some willingness to overcome negative attitudes about research, as well as to bring an interest in learning more about research activities. To accomplish this, community members must be afforded opportunities to learn about the advantages and limitations of specific research designs and methods. Concepts such as random assignment and standardization must become familiar, along with the advantages and limitations of validated instruments.

Collaboration requires community constituents to take risks and share honest information with researchers regarding community needs, perceptions of research, ideas regarding cultural values and contextual norms. It must be understood that this is a risk given the serious concern that vulnerable communities often hold that researchers will use this information to reinforce negative stereotypes about the community and its’ members (Stevenson & White, 1996). Finally, community partners must be willing to ask questions and seek clarification to ensure understanding. This is necessary in order to work productively and resolve conflicts and to ensure joint decision-making (McKay, in press). Not only must community partners accommodate to collaborative research projects, so too, must university-based researchers. University partners need to begin with a willingness to share information with community partners. Necessary information includes sharing knowledge regarding a research study’s specific aims, primary hypotheses, advantages and limitations of research procedures and budgets. Further, in addition to the sharing of information, researchers need to have a level of openness to sharing control over decision making process. It is only when joint decision-making and consensus becomes the norm that trust can be established. In order to build a critical level of trust, researchers must proceed more slowly to ensure community participation and understanding. This often requires the researcher to build in a longer period of start-up in order to ensure that community participation has been accomplished prior to the beginning of research activities. Finally, researchers need to accept substantial responsibility to provide ongoing training and support as constituents advance in their research skill development (Madison et al., 2000; Madison, Bell et al., in press)

CONCLUSIONS AND IMPLICATIONS

Increasingly, there have been calls to maximize community/prevention scientist collaboration in order to design relevant risk reduction programs for youth living within high risk urban contexts (Trickett, 1998). Concerns regarding the consequences of early and high risk sexual behavior for urban minority youth have been constant over the past several decades. HIV infection rates continue to rise in young people, with youth of color disproportionately affected. Programs designed specifically for these youth are critically needed (Center for Disease Control, 2001; 2000). Though collaboration with communities has been emphasized as a necessary component of building successful interventions, there are still too few models regarding how to develop and sustain such critically needed partnerships focused on HIV prevention programming and research activities. The Collaborative Board mechanism, described here, offers some encouragement that such structures can succeed in urban communities and be replicated across sites.

Acknowledgments

Funding from the National Institute of Mental Health (R01 MH 63662) and the W. T. Grant Foundation is gratefully acknowledged. Dr. Pinto is a post-doctoral fellow at the HIV Center for Clinical and Behavioral Studies (New York State Psychiatric Institute and Columbia University) supported by a training grant from the NIMH (T32 MH19139 Behavioral Sciences Research in HIV Infection). The HIV Center is supported by a center grant from NIMH (P30 MH43520). William Bannon is currently a pre-doctoral fellow at the Columbia University School of Social Work supported by a training grant from the National Institutes of Mental Health (5T32MH014623-24).

Footnotes

Without the contributions of CHAMP Collaborative Board members and participants, this work would not have been possible.

REFERENCES

- Altman DG. Sustaining interventions in community systems: On the relationship between researchers and communities. Health Psychology. 1995;14(6):526–536. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.14.6.526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aponte HJ, Zarskl J, Bixenstene C, Cibik P. Home/community based services: A two-trier approach. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1991;61(3):403–408. 224. doi: 10.1037/h0079270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnstein S. The ladder of citizen participation. Journal of American Institute Planners. 1969;35(4):216–224. [Google Scholar]

- Atkins M, McKay M, Arvanitis P, Madison S, Costigan C, Haney P, Zevenbergen A, Hess, Bennett D, Webster D. Ecological model for school-based mental health services for urban low-income aggressive children. Journal of Behavioral Health Services and Research. 1998;25(1):64–75. doi: 10.1007/BF02287501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu P. The forms of capital. In: Richardson JG, editor. Handbook of theory and research for the sociology of education. Greenwood Press; New York: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Boyd-Franklin N. Black Families. In: Walsh F, editor. Normal Family Process. Guilford Press; New York: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Brown LK, DiClemente RJ, Park T. Predictors of condom use in sexually active adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health. 1992;13(8):651–657. doi: 10.1016/1054-139x(92)90058-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention HIV/AIDS Surveillance Report. 1998;9:1–43. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention HIV/AIDS Surveillance Report. 2000;12(2) [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Compendium of HIV Prevention Interventions with Evidence of Effectiveness. Author; Atlanta, GA: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Chavis DM, Stucky PE, Wandersman A. Returning basic research to the community: The relationship between scientist and citizen. American Psychologist. 1983;38(4):424–434. [Google Scholar]

- Dalton HL. AIDS in blackface. Daedalus. 1989;118(3):205–227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiLorenzo T, Hein K. Adolescents: The leading edge of the next wave of the HIV epidemic. In: Wallender JL, Siegel LJ, editors. Adolescent Health Problems: Behavioral Perspectives. Advances in Pediatric Psychology. Guilford Press; New York: 1993. pp. 117–140. [Google Scholar]

- Eccles JS. The power and difficulty of university-community collaboration. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 1996;6(1):81–86. [Google Scholar]

- Elliott D, Koroloff N, Koren P, Friesen B. Improving access to children’s mental health services: The Family Associate approach. In: Epstein M, Kutash K, editors. Outcomes for children and youth with emotional and behavioral disorders and their families: Programs and evaluation best practices. PRO-ED; Austin, TX: 1998. pp. 581–609. [Google Scholar]

- Farhall J, Webster B, Hocking B, Leggatt M, Riess C, Young J. Training to enhance partnerships between mental health professionals and family caregivers: A comparative study. Psychiatric Services. 1998;49(11):1488–1490. doi: 10.1176/ps.49.11.1488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forehand R, Miller KS, Armistead L, Kotchick BA, Long N. The Parents Matter! Program: An introduction. Journal of Child & Family Studies. 2003;13:1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Fullilove MT, Fullilove RE., III . Understanding sexual behaviors and drug use among African Americans: A case study of issues for survey research. In: Ostrow DG, Kessler RC, editors. Methodological Issues in AIDS Behavioral Research. Plenum Press; New York: 1993. pp. 117–132. [Google Scholar]

- Fullilove RE, Green L, Fullilove MT. The Family to Family program: A structural intervention with implications for the prevention of HIV/AIDS and other community epidemics. AIDS. 2000;14(Suppl 1):S63–S67. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200006001-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galbraith J, Stanton B, Feigelman S, Ricardo I, Black M, Kalijee L. Challenges and rewards of involving community in research: An overview of the “Focus on Kids” HIV-risk reduction program. Health Education Quarterly. 1996;23(3):383–94. doi: 10.1177/109019819602300308. To be published in. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatch J, Moss N, Saran A, Presley-Cantrell L, Mallory C. Community research: Partnership in black communities. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 1993;9(6, Suppl):27–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine . The Hidden Epidemic: Confronting Sexually Transmitted Diseases. National Academy Press; Washington, DC: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine . Bridging the Gap Between Practice and Research: Forging Partnerships with Community-Based Drug and Alcohol Treatment. National Academy Press; Washington, DC: 1998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Israel BA, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, Becker AB. Review of community-based research: assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. Annual Review of Public Health. 1998;19:173–202. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.19.1.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jemmott JB, Jemmott LS, Fong GT. Abstinence and safer sex HIV risk-reduction interventions for African American adolescents: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 1998;279(19):1529–36. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.19.1529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jemmott LS, Jemmott JB. Increasing condom-use intentions among sexually active Black adolescent women. Nursing Research. 1992;41(5):273–279. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen PS, Hoagwood K, Trickett EJ. Ivory towers or earthen trenches? Community collaborations to foster real-world research. Applied Developmental Science. 1999;3:206–212. [Google Scholar]

- Kirby D, Short L, Collins J, Rugg D, Kolbe L, Howard M, Miller B, Sonenstein F, Zabin LS. School-based programs to reduce sexual risk behaviors: a review of effectiveness. Public Health Reports. 1994;109(3):339–60. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koroloff NM, Elliott DJ, Koren PE, Friesen BJ. Connecting low-income families to mental health services: The role of the family associate. Journal of Emotional & Behavioral Disorders. 1994;2(4):240–246. [Google Scholar]

- Madison S, Bell C, Sewell S, Nash G, McKay M, Paikoff R. True community/academic partnerships. Psychiatric Services. (in press) [Google Scholar]

- Madison S, CHAMP Collaborative Board Creating the conditions for meaningful university-community partnerships; Paper presented at the NIMH Role of Families in Preventing and Adapting to HIV/AIDS, an official satellite conference for the XI International conference on AIDS; Vancouver, Canada. Jul, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Madison S, McKay M, Paikoff RL, Bell C. Community collaboration and basic research: Necessary ingredients for the development of a family-based HIV prevention program. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2000;12:281–298. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormick A, McKay M, Marla, Wilson, McKinnwy L, Paikoff R, Bell C, Baptiste D, Coleman D, Gillming G, Madison S, Scott R. Involving families in an urban HIV preventive intervention: How community collaboration addresses barriers to participation. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2000;12(4):299–307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKay M. Collaborative child mental health services research: Theoretical perspectives and practical guidelines. In: Hoagwood K, editor. Collaborative research to improve child mental health services. in press. [Google Scholar]

- McKay M, Baptiste D, Coleman D, Madison S, Paikoff R, Scott R. Preventing HIV risk exposure in urban communities: The CHAMP Family Program. In: Pequegnat W, Szapocznik Jose, editors. Working with families in the era of HIV/AIDS. Sage Publications; California: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- McKay M, Chasse K, Paikoff R, McKinney L, Baptiste D, Coleman D, Madison S, Bell C, CHAMP Collaborative Board Family-level impact of the CHAMP Family Program: A community collaborative effort to support urban families and reduce youth HIV risk exposure. Family Process. 2004;43(1):77–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2004.04301007.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLoyd VC. The impact of economic hardship on Black families and children: Psychological distress, parenting, and socioemotional development. Child Development. 1990;61(2):311–345. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1990.tb02781.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNeal RB. Parental involvement as social capital: Differential effectiveness on science achievement, truancy, and dropping out. Social Forces. 1999;78(1):117–144. [Google Scholar]

- Miller KS, Clark LF, Moore JS. Sexual initiation with older male partners and subsequent HIV risk behavior among female adolescents. Family Planning Perspectives. 1997;29(5):212–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minkler M, Wallerstein N. Community based participatory research for health. Jossey-Bass; San Francisco, CA: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Minnis AM, Padian NS. Choice of female-controlled barrier methods among young women and their male sexual partners. Family Planning Perspectives. 2001;33(1):28–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Mental Health Priorities for Prevention Research at NIMH. National Institute of Mental Health, National Institutes of Health. 1998 Available at: http://www.nimh.nih.gov/publist/984321.htm.

- Paikoff R, McKay MM, Bell C. Collaborative HIV prevention and Adolescent Mental health Project (CHAMP) 1994. grant proposal submitted to the National Institute of Mental Health.

- Puttman RD. Bowling Alone: The collapse and revival of American community. Simon and Schuster; New York: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Rotheram-Borus MJ, Mahler KA, Rosario M. AIDS prevention with adolescents families. AIDS Education and Prevention. 1995;7(4):320–336. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanstad KH, Stall R, Goldstein E, Everett W, Brousseau R. Collaborative community research consortium: A model for HIV prevention. Health Education & Behavior. 1999;26(2):171–184. doi: 10.1177/109019819902600202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schensul JJ. Organizing community research partnerships in the struggle against AIDS. Health Education & Behavior. 1999;26(2):266–83. doi: 10.1177/109019819902600209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Secrest LA, Lassiter SL, Armistead LP, Wyckoff SC, Johnson J, Williams WB, Kotchick BA. The Parents Matter! Program: Building a successful investigator-community partnership. Journal of Child & Family Studies. 2004;13:35–45. [Google Scholar]

- Singer M. Knowledge for use: Anthropology and community-centered substance abuse. Social Science Medicine. 1993;37:1, 15–25. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(93)90312-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanton B. In Adolescent and HIV/AIDS Research: A Developmental Perspective. Rockville, MD: 1996. Longitudinal evaluation of AIDS prevention intervention. [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson HC, Davis G, Weber E, Weiman D, et al. HIV prevention beliefs among urban African American youth. Journal of Adolescent Health. 1995;16(4):316–323. doi: 10.1016/1054-139X(94)00090-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson HC, White JJ. AIDS prevention struggles in ethnocultural neighborhoods: Why research partnerships with community based organizations can’t wait. AIDS Education & Prevention. 1994;6:126–139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stringer ET. Action research: A handbook for practitioners. Sage Publications; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas SB, Quinn SC. The Tuskegee syphilis study, 1932 to 1972: Implications for HIV education and AIDS risk education programs in the black community. American Journal of Public Health. 1991;81:1498–1505. doi: 10.2105/ajph.81.11.1498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trickett EJ. Toward a framework for defining and resolving ethical issues in the protection of communities involved in primary prevention projects. Ethics & Behavior. 1998;8:321–337. doi: 10.1207/s15327019eb0804_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wandersman A. Community science: bridging the gap between science and practice with community-centered models. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2003;31:227–42. doi: 10.1023/a:1023954503247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weeks MR, Schensul JJ, Williams SS, Singer M, et al. AIDS prevention for African American and Latina women: Building culturally and gender-appropriate intervention. AIDS Education & Prevention. 1995;7:251–264. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson WJ. The truly disadvantaged: The inner city, the underclass, and public policy. University of Chicago Press; Chicago: 1987. [Google Scholar]