Abstract

Chemically induced polyploids were obtained by the colchicine treatment of shoot tips of Humulus lupulus L. ‘Sybilla’. Flow cytometry revealed that most of the treatments resulted in the production of tetraploids. The highest number of tetraploids was obtained when explants were immersed in 0.05% colchicine for 48 h. A field experiment was conducted to compare diploid and tetraploid plants and assess the effect of genome polyploidization on the morphological and chemical characteristics. Tetraploids showed significant differences in relation to diploids. They had thinner and shorter shoots. The influence of chromosome doubling was also reflected in the length, width and area of leaves. The length of female flowers in the tetraploids was significantly shorter than that observed in diploids. Tetraploids produced a diverse number of lupuline glands that were almost twice as large as those observed in diploids. The most distinct effect of genome polyploidization was a significant increase in the weight of cones and spindles. Contents of major chemical constituents of hop cones was little affected by ploidy level. Total essential oils were significantly lower than those in diploids. However there was a significant increase in the proportion of humulene, caryophyllene and farnesene, oils desired by the brewing industry.

Keywords: Humulus lupulus, polyploidization, tetraploid, morphological characterization

Introduction

Hop (Humulus lupulus L.) occurs in the temperate climate zone and belongs to the order of Urticales and family of Cannabaceae. It is a perennial, dioecious plant with highly developed aerial parts which produce infructescenses called cones. Hop cones are an important source of soft resins and essential oils which give beer its specific taste and aroma (Haunold 1971). They are also a valuable source of bioactive substances, including xanthohumol which exhibits a strong antioxidant activity and can inhibit tumor formation (Gerhauser et al. 2002).

Only female plants are cultivated on hop plantations. Male plants which grow near productive plantations need to be removed to prevent the pollination of female inflorescences and production of seeds in the cones. From the point of view of the brewing industry, the presence of seeds in the cones is undesirable as their fats and proteins adversely affect beer fermentation (Hildebrand et al. 1975). One of the ways to obtain raw hop material largely devoid of seeds is the cultivation of triploid cultivars (Haunold 1972). Triploids produce non-functional reproductive cells, and the resulting infertility causes an economically valuable seedlessness (Dhooghe et al. 2011). Triploid cultivars of hop are known in Australia, New Zealand, USA and Slovenia. The research has shown that triploids, besides producing seedless cones, are characterized by a substantial vigor, higher yielding potential and alpha acid content compared to the diploid plants (Roy et al. 2001).

In the process of production of triploid plants (2n = 3x = 30), the first step is to obtain the tetraploid plants (2n = 4x = 40), which are then crossed with the male diploid plants. Due to the fact that all of the naturally occurring plants as well as hybrids of the species H. lupulus L. obtained in the classic breeding are diploid, obtaining triploids requires prior polyploidization of genomes. Forms with a double number of chromosomes can be obtained through the application of colchicine solution on nodal parts of shoots or young seedlings of hops. The effectiveness of this method in the in vivo conditions is very low, because tetraploid forms develop from only 5% of the hop plants subjected to mutagenesis (Roborgh 1969). Significantly better results can be obtained using this technique in the in vitro conditions. The effectiveness of the induction of tetraploid forms with this method amounted up to 25.6% (Roy et al. 2001). Similar observations were made by other authors in the studies concerning the use of colchicine in breeding of polyploid mulberry (Chakraborti et al. 1998), maize (Barnabas et al. 1999) or tomatillo (Robledo-Torres et al. 2011). The before mentioned method of doubling the chromosomes number, despite its effectiveness, is the source of many changes to the morphological structure of plants as well as to the content of the desired compounds. It has been shown that in the case of Platanus acerifolia (Liu et al. 2007), Rosa (Kermani et al. 2003) and Pyrus communis (Sun et al. 2009), doubling of genetic material causes the increase in the thickness of the leaves, leaf length/width ratio, the size of flowers and a darker green color of leaves. Among the medicinal plants, the increased level of ploidy causes the increased content of triterpenoids in Centella asiatica (Kaensaksiri et al. 2011) or alkaloids in Datura stramonium (Berkov and Filipov 2002).

The present study reports on induction of tetraploids of H. lupulus L. ‘Sybilla’ through the in vitro colchicine treatment. The paper also takes a look into the potential of artificial polyploidy as a source of induced variation and compares morphological and chemical traits between the diploid controls and in vitro induced tetraploids.

Materials and Methods

Plant material

The plant material were one-year-old diploid plants of Humulus lupulus L. ‘Sybilla’. This aromatic cultivar is characterized by both a good flavor and high content of around 6–8% of alpha acids in cones. Moreover, it is one of the most promising cultivars corresponding to both the demands of the brewing industry and of the processors of hop. The nodal explants from greenhouse-grown plants in 2009 were surface sterilized in 70% ethanol for 30 s, then in a 1% solution of sodium hypochlorite for 20 min, followed by 3 rinses with sterile water. Subsequently, the explants were placed on a medium containing major and minor MS salts (Murashige and Skoog 1962), 10 mg/l myoinositol, 5 mg/l nicotinic acid, 1 mg/l thiamine, 1 mg/l pyridoxine, 1 mg/calcium pantothenate, 2 mg/l benzylaminopurine (BAP), 2% glucose, 0.7% agar. The pH of the medium was adjusted to 5.8. The sterile cultures were transferred to fresh medium and maintained for 5 weeks at 24/26°C under a 16/8 h photoperiod using a fluorescent light 45 μmol/m2s.

Colchicine treatment

The shoot tips of 5–7 mm length were collected from in vitro grown plants and immersed in liquid MS medium containing 2% glucose and filter-sterilized colchicine (Sigma) at concentration of 0.01, 0.05, 0.1%. The explants were incubated in colchicine solution and shaken at 100 rpm for 24, 48 and 72 hours in light at 24°C. Flasks with MS medium free from colchicine were used as a control. Eighteen shoot tips were used for each treatment. The experiment was repeated twice. After colchicine treatment, explants were washed three times with sterile water, dried on filter paper and transferred to MS medium containing IBA 0.5 mg/l, GA3 0.5 mg/l, BAP 0.1 mg/l, 2% glucose and 0.7% agar. After three weeks of culture, shoots were transferred to fresh MS medium free from plant-growth regulators for root induction. The plant material was incubated at 24/26°C under a 16/8 h photoperiod using a fluorescent light 45 μmol/m2s. Well rooted plants were transferred to plastic pots filled with peat and perlite mix (1 : 1) and acclimatized to greenhouse conditions.

Identification of polyploids by flow cytometry

Measurements of the DNA content of colchicine treated plants was performed according to the two-step procedure described by Sliwinska (2008). Hop diploid plants collected from the greenhouse were used as an external standard to calibrate the flow cytometer. Leaf samples of 1 cm2 were chopped with a razor blade in 1 ml of nuclei isolation buffer (Partec) containing 1% PVP-10. The obtained suspension was filtered through a filter with a mesh diameter of 35 μm and stained with 4 μg/ml DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindolel, Sigma). After 2 minutes of incubation, the tested samples were analyzed for relative fluorescence intensity. For each sample, around 5000 nuclei were analyzed using a Beckman Coulter Cell Lab Quanta TM SC flow cytometer equipped with a mercury arc lamp.

Cytological techniques

The somatic chromosomes were prepared from young leaves. Plant material was treated for 5 h with 0.44% solution of oxychinoline with maltose. Additionally, plant material was fixed in the modified Carnoy’a solution (ethanol-chloroform-acetic acid, 6 : 3 : 1) for 24 h. Subsequently, leaves were hydrolyzed in a mixture of Carnoy’a solution and HCl (10%) at 60°C for 10 min. After the hydrolysis, acetocarmine-stained preparations were prepared according to a procedure developed by Burns (1964). Chromosome number was determined in at least 30 cells in 20 randomly selected plants of each ploidy groups.

Morphological measurements

Well rooted and flow cytometry verified plants were allowed to grow for 4 months in the greenhouse and then 20 of them were transferred to the experimental field. Plants were spaced at 1 m × 3 m and all standard hop management practices were applied. After three years of growth, only 6 plants survived from the total of 20 tetraploids and were compared to diploid control plants. Assessment of morphological parameters was conducted in 2011. The following traits were taken into consideration: main stem diameter, length of lateral shoots, length, width and area of 20 fully expanded leaves that were randomly collected from mid and upper part of main and lateral shoots of each plant. Further characterization included the evaluation of the length and width of 50 female flowers taken from plants during full flowering. Hop cones were analyzed for the fresh weight of 100 cones as well as fresh weight of 100 spindles, size and number of lupuline glands on the 1 cm2.

Chemical components of cones

Cones were collected from each individual tetraploid and diploid at the technological maturity stage. About 1.0 kg of fresh cones from the height of about 5 m were manually harvested in 2011. Cones were dried in a chamber drier at the temperature of 50°C for 8–10 h and stored in cold storage before analysis. The studies included the analysis of alfa acids (% dry matter) using lead conductance method (EBC 7.4) (Fachverlag 2007). The content of total essential oils of dry matter (ml/100 g) was determined by the method of steam distillation (EBC 7.10) using a Dering apparatus. The composition of the hop oils was analyzed by gas chromatography (EBC 7.12) using Agilent 5975C gas-chromatograph. The chemical analyses were performed in three replications.

Statistical analysis

The data were analyzed by the analysis of variance (ANOVA). Duncan’s test was used to examine the differences of the survival rate and ploidy level of plants. Dunnett’s test (STATGRAPHICS XV) was used to compare parameters of morphology and chemical content.

Results

Survival rate and rooting of explants

All of the colchicine treatments caused phytotoxic effects on H. lupulus L. ‘Sybilla’ explants. Initially, explants showed slower growth as compared to that observed in the control. Finally, part of them yellowed and died. The survival rate ranged from 72.2 to 94.4% and was affected by exposure time and colchicine concentration (Table 1). With increasing colchicine concentration and exposures, the explants showed a lower survival rate. The highest lethality was observed in the treatments with the 0.1% solution for 72 h. Another noticeable effect of colchicine treatment was impeded rooting of explants. After 30 days of growth on LS medium, they produced from 5 to 8.7 roots whilst control shoots produced an average of 9 roots. The highest number of roots was obtained when shoot tips were treated with low colchicine concentration for a short time. There was no significant relationship, though, between the number of roots and colchicine treatment. The explants differed also for the length of roots. The longest roots were observed in the plants which had not been treated with colchicine. Statistically significant differences were seen only between the control and individual treatments. Well rooted shoots were transferred to the peat mix and grown in greenhouse conditions.

Table 1.

Survival rate, root formation and ploidy level of H. lupulus L. ‘Sybilla’ plants obtained after treatment of shoot tips with colchicine

| Concentration of colchicine (%) | Exposure (h) | Survival rate (%) | Number of roots/explant | Root length (cm) | Ploidy (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Diploid | Mixoploid | Tetraploid | |||||

| 0 (control) | 72 | 100.0a | 9.0c | 2.16b | 100.0g | 0.0a | 0.0a |

| 0.01 | 24 | 94.4b | 8.7ab | 1.26a | 77.7f | 11.1b | 5.6b |

| 0.01 | 48 | 94.4b | 8.3ab | 1.16a | 50.0e | 27.8cd | 16.7e |

| 0.01 | 72 | 88.9d | 7.6ab | 0.98a | 41.7d | 36.1d | 11.1c |

| 0.05 | 24 | 91.7c | 8.6ab | 1.28a | 47.2e | 25.0c | 19.4f |

| 0.05 | 48 | 91.7c | 5.7ab | 1.27a | 36.1c | 30.6cd | 25.0h |

| 0.05 | 72 | 86.1e | 5.3ab | 0.95a | 22.2b | 47.2e | 16.7e |

| 0.1 | 24 | 88.9d | 7.7ab | 0.87a | 16.7a | 52.8ef | 19.4f |

| 0.1 | 48 | 80.6f | 5.0a | 0.82a | 13.9a | 44.4e | 22.2g |

| 0.1 | 72 | 72.2g | 5.0a | 0.33a | 22.2b | 33.3cd | 16.7e |

Values within a column followed by different letters differ significantly by Duncan’s multiple range test at the 0.05 level of significance.

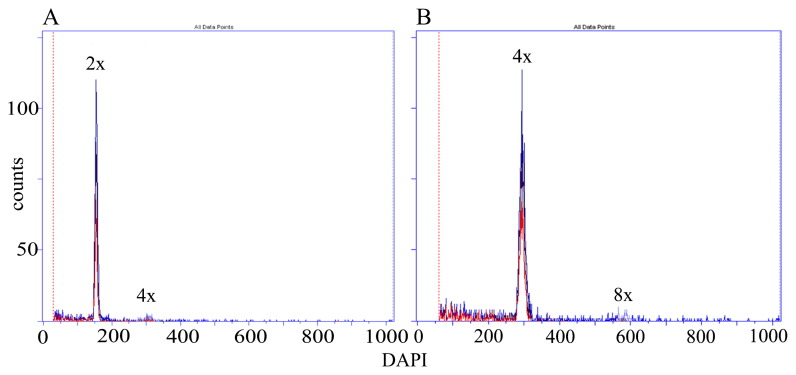

Results of polyploidization

Flow cytometry analysis of greenhouse grown plants revealed that all colchicine treatments induced polyploids. The effectiveness of polyploidization ranged from 5.6 to 52.8% and it was significantly dependent on the concentration and exposure time of the colchicine treatment (Table 1). Among viable polyploids there were mixoploids and tetraploids. Fig. 1 presents the flow cytometry histograms illustrating fluorescent intensity peaks of the diploid standard H. lupulus L. ‘Sybilla’ against those of tetraploid forms. The percentage of polyploids was determined in the population treated with colchicine. There were significant differences in the number of the induced tetraploids among treatments. The highest number of tetraploids (25.0%) was obtained when apical buds were treated with 0.05% colchicine concentration for 48 hours (Table 1). The treatment with 0.1% colchicine for 48 h was also efficient (22.2%), but generated a significantly lower number of tetraploids than did the 0.05% for 48 h. A relatively high number of tetraploids was also obtained in the treatments involving 24 h exposure to 0.05 and 0.1% colchicine, but in the case of higher colchicine concentration, mortality of shoots was higher. Generally, it was observed that the proportion of tetraploids increased with increasing concentrations of colchicine and exposure time. However, the protocols involving 0.1% colchicine for 72 h and 0.05% for 48 h did not prove to be the most effective in obtaining of tetraploids due to the fact that they generated the highest mortality of explants.

Fig. 1.

Flow cytometric histograms of the nuclear DNA content in: (A) diploid (2n = 2x = 20) and (B) tetraploid (2n = 4x = 40) plants of H. lupulus L. ‘Sybilla’

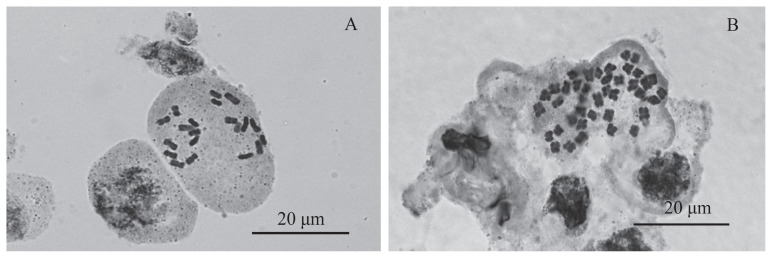

Chromosome verification

Mitotic analysis confirmed that the somatic cells of non-treated diploid H. lupulus L. contained 2n = 2x = 20 of chromosomes while the cells from the plants cytometrically verified as tetraploids actually had 2n = 4x = 40 (Fig. 2). The mixoploid plants reported in the study showed cells with tetraploid or diploid complements of chromosomes. The cytological studies confirmed that there were no aneuploid plants.

Fig. 2.

Mitotic chromosomes in somatic cell of: (A) diploid (2n = 2x = 20) and (B) tetraploid (2n = 4x = 40) plants of H. lupulus L. ‘Sybilla’, bar = 20 μm

Morphological and chemical characteristics

Polyploid plants showed a relatively poor ability to acclimatize to field conditions. From a total of 20 plants transferred to the plot only six survived. These surviving plants were referred to as plants No. 1–6 for the subsequent studies. Growth of tetraploids was rather slow and morphological characteristics differed from those of their diploid counterparts. Significant changes bound up with increased ploidy level were recorded for ten important traits. Tetraploids had significantly thinner basal stems. The average stem diameter ranged from 4.7 to 7.4 mm for plants of higher ploidy and 8.2 mm for diploids (Table 3). Moreover, tetraploids produced lateral shoots much shorter than diploids due to shorter internodal length (data not shown) and in five cases, the difference could be statistically proved. In addition, there was some diversity between tetraploid individuals for that characteristic. The shortest stems were produced by plants no. 1 and 5. The results showed that increasing the ploidy level of hop resulted in smaller leaves. Most of tetraploids tended to have shorter and narrower leaves in the middle part of the main and lateral shoots than did the diploid plants (Fig. 3). As a result, leaf area was smaller and the differences were statistically significant. However, this divergence from diploids was less evident in the case of leaves situated in the upper part of the lateral shoots. In the majority of plants, leaves originating from the top had a size similar to that in control plants. The analysis of flower morphology showed that flower length is a ploidy-related parameter. The tetraploids designated as nos. 1, 2, 3, 5 and 6 had significantly shorter flowers while flower width was comparable at both ploidy levels (Table 3 and Fig. 3). Measurements of cones were made when plants reached technological maturity. The weight of cones ranged from 48.1 to 73.3 g and was one of three parameters for which tetraploids outperformed diploids. Plants of higher ploidy had significantly higher length of lupuline glands as well as weight of spindles than the diploids. Tetraploid plants also tended to have a significantly smaller number of lupuline glands, which were significantly longer than those in their diploid counterparts.

Table 3.

Morphological characteristics of flowers and hop cones of diploid and tetraploid plants of H. lupulus L. ‘Sybilla’

| Plant tested | Stem diameter (mm) | Lateral shoot length (m) | Flower | Number of lupuline glands/cm2 | Length of lupuline μ glands ( m) | Weight of | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

||||||||

| Length (mm) | Width (mm) | 100 cones (g) | of 100 spindles (g) | ||||||

| Tetraploids | 1 | 6.0abc | 0.2a | 12.0b | 7.1a | 98.6b | 252.9c | 60.3d | 14.2c |

| 2 | 4.7a | 0.4b | 13.4d | 9.1de | 85.1ab | 273.3d | 55.6cd | 15.2c | |

| 3 | 5.5ab | 0.7c | 12.7c | 8.3c | 126.6c | 235.8b | 48.1ab | 12.1b | |

| 4 | 7.4cd | 0.5b | 13.7dc | 9.3e | 71.3a | 257.0c | 55.8cd | 11.9b | |

| 5 | 5.6abc | 0.2a | 11.5a | 7.5ab | 77.1a | 236.3b | 73.3e | 17.1d | |

| 6 | 6.1bc | 0.5b | 12.0b | 7.9b | 103.4b | 240.1b | 54.7cd | 12.8b | |

|

| |||||||||

| Diploid | 8.2d | 0.7c | 13.9d | 8.7cd | 134.6c | 171.8a | 43.1a | 7.9a | |

|

| |||||||||

| Dunnett | 2.0 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.6 | 19.5 | 9.6 | 5.7 | 1.3 | |

Values within a column, means followed by different letters differ significantly from ‘Sybilla’ based on Dunnett’s test.

Fig. 3.

Flowers, hop cones and leaves of diploid and tetraploid H. lupulus L. ‘Sybilla’: (A) female flowers of diploid (lower half of panel) and tetraploid (upper half of panel) plants, bar = 10 mm, (B) hop cones of diploid (left) and tetraploid (right) plants, bar = 10 mm and (C) fully expanded leaves of diploid (left) and tetraploid (right) plants, bar = 10 mm

Although the lupulin glands were considerably longer in tetraploids than in diploids it was not reflected in the quality of hop cones. Alpha acids content in tetraploids was lower than that of ‘Sybilla’ but it was not statistically significant (Table 4). The total content of essential oils from tetraploid cones was also below the level recorded for diploid individuals, however there was a significant increase in the proportion of humulene and limonene. Differences between tetraploids and diploids were also observed for the concentration of caryophyllene and farnesene, components desired in brewing. The tetraploid plants had a reduced content of the undesirable essential oil myrcene but the difference was not statistically significant.

Table 4.

The alpha acids content and hop oil composition in cones of diploid and tetraploid plants of H. lupulus L. ‘Sybilla’

| Characters | Diploids | Tetraploids |

|---|---|---|

| Alpha acids content (%) | 6.24 ± 0.39a | 5.96 ± 1.59a |

| Total oils (ml/100 g) | 1.99 ± 0.10a | 1.31 ± 0.11b |

| Myrcene (%) | 44.70 ± 4.01a | 42.34 ± 1.41a |

| Limonene (%) | 0.17 ± 0.01b | 0.57 ± 0.04a |

| Caryophyllene (%) | 6.01 ± 0.58a | 7.83 ± 0.12a |

| Farnesene (%) | 10.83 ± 0.41a | 8.77 ± 2.24a |

| Humulene (%) | 17.91 ± 1.27a | 23.76 ± 2.92b |

| Geraniol (%) | 0.08 ± 0.02a | 0.23 ± 0.11a |

Data represents mean ± SD values of three replicates.

Means within the same row with different letters differ significantly according to Dunnett’s test.

Discussion

Production of polyploid forms is one of the methods used in plant breeding. In the case of hop, the production of tetraploids has been the subject of interest to several research papers. Most of them were concerned with the effectiveness of polyploidization in the in vivo conditions, cytological evaluation of polyploids (Haunold 1971, 1972) or yielding of triploids of hops (Roy et al. 2001). There are also reports on the in vitro induction of polyploids of hops (Roy et al. 2001, Skof et al. 2007). These reports do not include, however, a comprehensive study on the comparison of tetraploids with their diploid counterparts and on the effect of polyploidization on the morphological and chemical properties of hop.

In the present work, in order to polyploidize the genome of hop, colchicine solution was applied to intensively growing meristematic tissue in the in vitro conditions. This method has so far been successfully applied in the process of induction of Musa tetraploids (Van Duren et al. 1996), Rosa (Kermani et al. 2003) and H. lupulus L. cultivar ‘H 138’ (Roy et al. 2001). The high percentage of tetraploid plants at the application of relatively low concentrations of colchicine compared to those used in the in vivo conditions led the authors to use the methods of polyploidization as described in this study. The results indicate that colchicine had negative effects on apical shoots of the hop cultivar ‘Sybilla’. Toxic effects of colchicine were proportional to its concentration and exposure time. Long immersion in a higher concentration of colchicine solution adversely affected the viability and rooting of the explants, while a short-time treatment in a low concentration of colchicine proved to be little effective in terms of tetraploid induction. Cytometric analyses of plants showed that the proportion of tetraploids increased with increasing concentration and time of exposure to colchicine. The largest percentage of tetraploids was recorded for the concentration of 0.05% and 48 h. The results correspond with those for ‘H138’ and confirm the tendency observed by Roy (2001) in which the induction of hop tetraploids with low concentrations of colchicine required long exposure time. The studied population of 281 polyploids had a significantly lower proportion of mixoploid plants (containing both diploid and tetraploid nuclei) as compared with Roy’s study. Low percentage of mixoploids was probably the result of the use of a different genotype of hops. It is likely, however, that the differences in the number of mixoploids were the result of applying different techniques of plant regeneration from colchicine-treated shoot tips.

The presented data show that polyploidization of hop genome significantly affected morphological and chemical properties of the hop cultivar ‘Sybilla’. Most of the studied plants had a significantly smaller diameter of the shoots and a more compact growth habit due to significantly shorter lateral shoots. Compact growth habit and production of shorter internodes were the effects of polyploidization of genomes: Ullucus tuberosus (Viehmannova et al. 2009) and Platanus acerifolia (Liu et al. 2007). Another characteristic phenomenon occurring in polyploid plants was an increase in the size of the leaves in relation to their diploid counterparts. An increased length and width of leaves were observed, among others, with tetraploids Phlox subulata (Zhang et al. 2008) or Paulownia tomentosa (Tang et al. 2010). In the present work it was found that doubling of the number of chromosomes in the hop cultivar ‘Sybilla’ resulted in a reduced length and width of leaves in comparison with diploid plants. Negative impact of polyploidization was primarily visible on the leaves situated in the central part of the main shoot and of the lateral shoots. It less affected the leaves situated on the upper part of the stem. A similar reduction in the size of the leaves and in particular in their length were observed with polyploids of Ullucus tuberosus (Viehmannova et al. 2009). A measureable effect of the limitations of the assimilation surface of the ulluco leaves was, among others, a significant decrease in the weight of the micro-tubers produced.

Polyploidization of the genome significantly modifies morphological and physiological properties of plants. A frequently observed phenomenon is an increase in the size of the flowers, as well as the delayed time of flowering. In the present work, two of the six tested tetraploids produced wider flowers and bloomed 5–7 days later (data not shown) compared to the control cultivar. The results correspond with those presented by Gu et al. (2005) which showed flowering delayed by 3–4 days and larger size of flowers of Zizyphus jujuba tetraploids. The delayed flowering with a concomitant increased diameter of the flowers were also one of the effects of doubling of the number of chromosomes in Rosa in the study of Kermani et al. 2003. The change in the level of ploidy often modifies the characteristics related to the usefulness of the plant. In the case of Ullucus tuberosus, it significantly affected the weight, decreased the number of buds per tuber and significantly increased the content of vitamin C in the tubers. There was also an increase in the content of carbohydrates at Lolium perenne and Lolium multiflorum (Dewey 1980) as well as alkaloids in the roots and leaves of Datura stramonium (Berkov and Philipov 2002). In this study, doubling of the number of chromosomes in the hop cultivar ‘Sybilla’ had an effect on morphological characteristics of cones. Both the weight of cones and of cone spindles were significantly higher in the tetraploids compared to those in diploid plants. Particularly large differences were observed in the case of spindle weight, which on average was by more than 75% higher in tetraploid plants in comparison with the diploid forms of ‘Sybilla’. Such a large increase in the weight of spindles and size of cones is not beneficial as it may disturb drying of the raw material. Also, in tetraploids a significant increase in the length of the lupuline glands was observed, which could be the result of a trade-off with the observed decrease in their number compared to the diploid plants. Polyploidization of ‘Sybilla’ involved also changes in the content of alfa acids compared with the material from the diploid plants. Tetraploid forms of hops were characterized with a significantly lower content of essential oils, but at the same time their composition was improved. There was an increase in the share of components having a positive impact on the aroma of hops, such as humulene or caryophyllene. The content of myrcene, which is undesirable in the brewing industry, was lower, although the difference was not statistically proven.

In conclusion, the methods of in vitro polyploidization used in this study and the assessment of the degree of ploidy of plants allowed six stable tetraploid variants of hop cv. ‘Sybilla’ to be obtained. The genotypes studied in the field experiment were characterized by satisfactory morphological characteristics as well as by a favourable chemical composition of hop cones. The tetraploids with the best commercial characteristics were selected and will serve as a starting material for further breeding of seedless triploids.

Table 2.

Characteristics of stem and dimensions of leaves of diploids of H. lupulus L. ‘Sybilla’ and their tetraploid counterparts

| Plant tested | Length of leaves (cm) | Width of leaves (cm) | Area of leaves (cm2) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||

| Main shoot | Lateral shoot | Main shoot | Lateral shoot | Main shoot | Lateral shoot | ||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||

| T | M | T | M | T | M | T | M | T | M | T | M | ||

| Tetraploids | 1 | 12.8bc | 13.3b | 6.4bc | 4.8a | 12.0c | 13.4c | 4.9bc | 4.0ab | 103.6c | 147.3bc | 24.0c | 16.0ab |

| 2 | 11.4a | 11.4a | 5.7ab | 5.5abc | 9.5a | 10.6a | 4.4ab | 4.2abc | 74.5a | 80.8a | 16.9ab | 16.4ab | |

| 3 | 13.8c | 11.9a | 6.3bc | 6.3d | 10.7b | 12.2b | 5.0c | 4.7cd | 96.3bc | 95.3a | 22.6bc | 21.4c | |

| 4 | 12.5b | 13.8b | 6.3bc | 5.9cd | 11.2bc | 13.2c | 4.8bc | 4.7cd | 82.5ab | 110.4ab | 22.9c | 20.8bc | |

| 5 | 11.4a | 13.2b | 5.3a | 4.8ab | 9.1a | 13.6c | 4.0a | 3.7a | 68.5a | 101.5ab | 15.6a | 13.7a | |

| 6 | 12.9bc | 11.8a | 6.8c | 5.6bcd | 12.1c | 11.1a | 5.1c | 4.4bc | 102.8c | 75.4a | 25.4c | 16.4ab | |

|

| |||||||||||||

| Diploid | 14.0c | 16.0c | 6.9c | 7.1e | 12.0c | 15.5d | 5.1c | 5.2d | 104.8c | 161.8c | 26.9c | 27.8c | |

|

| |||||||||||||

| Dunnett | 1.1 | 0,9 | 0.9 | 0.8 | 1.1 | 0.9 | 0.7 | 0.6 | 15.2 | 49.2 | 6.1 | 4.9 | |

Values within a column, means followed by different letters differ significantly from ‘Sybilla’ based on Dunnett test.

T: Top, M: Middle.

Acknowledgments

The research was financially supported by the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of Poland (project no. NN 310 437538).

Literature Cited

- Barnabas, B., Obert, B. and Kovas, G. (1999) Colchicine, an efficient genome doubling agent for maize (Zea mays L.) microspores cultured in anthero. Plant Cell Rep. 18: 858–862 [Google Scholar]

- Berkov, S. and Filipov, S. (2002) Alkaloid production in diploid and autotetraploid plants of Datura stramonium. Pharma Biol. 40: 617–621 [Google Scholar]

- Burns, J.A. (1964) A technique for making preparations of mitotic chromosomes from Nicotiana flowers. Tob. Sci. 8: 1–2 [Google Scholar]

- Chakraborti, S.P., Vijayan, K., Roy, B.N. and Qadri, S.M.H. (1998) In vitro induction of tetraploidy in mulberry (Morus alba L.). Plant Cell Rep. 17: 799–803 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dewey, D.R. (1980) Some applications and misapplications of induced polyploidy to plant breeding. In: Lewis, W.H. (ed.) Polyploidy-biological relevance. Plenum Press, New York, pp. 445–489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhooghe, E., Van Laere, K., Eeckhaut, T., Leus, L. and Van Huylenbroeck, J. (2011) Mitotic chromosome doubling of plant tissue in vitro. Plant Cell Tiss. Organ Cult. 104: 359–373 [Google Scholar]

- Fachverlag, H.C. (2007) Analitica EBC Section 7 Hops, European Brewery Convention, Nurmberg [Google Scholar]

- Gerhauser, C., Alt, A., Heiss, E., Gamal-Eldeen, A., Klimo, K., Knauft, J., Neumann, I., Scherf, H.R., Frank, N., Bartsch, H.et al. (2002) Cancer chemopreventive activity of xanthohumol, a natural product derived from hop. Mol. Cancer Ther. 1: 959–969 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu, X.F., Yang, A.F., Meng, H. and Zhang, J.R. (2005) In vitro induction of tetraploid plants from diploid Zizyphus jujube Mill. Cv. Zhanhua. Plant Cell Rep. 24: 671–676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haunold, A. (1971) Cytology, sex expression and growth of a tetraploid × diploid cross in hop (Humulus lupulus L.). Crop Sci. 11: 868–871 [Google Scholar]

- Haunold, A. (1972) Polyploid breeding with hop Humulus lupulus L. Technical Quarterly Master Brewers Assoc. of America 9: 36–40 [Google Scholar]

- Hildebrand, R.P., Kavanagh, T.E. and Clarke, B.J. (1975) Hop lipids and beer quality. Brewers Dig. 50: 58–60 [Google Scholar]

- Kaensaksiri, T., Soontornchainaksaeng, P., Soonthornchareonnon, N. and Prathanturarung, S. (2011) In vitro induction of poluploidy in Centella asiatica (L.) Urban. Plant Cell Tiss. Organ Cult. 107: 187–194 [Google Scholar]

- Kermani, M.J., Sarasan, V., Roberts, A.V., Yokoya, K., Wentworth, J. and Sieber, V.K. (2003) Oryzalin-induced chromosome doubling in Rosa and its effect on plant morphology and pollen viability. Theor. Appl. Genet. 107: 1195–1200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, G., Li, Z. and Bao, M. (2007) Colchicine-induced chromosome doubling in Platanus acerifolia and its effect on plant morphology. Euphytica 157: 145–154 [Google Scholar]

- Murashige, T. and Skoog, F. (1962) A revised medium for rapid growth and bioassays with tobacco tissue culture. Physiol. Plant 15: 473–497 [Google Scholar]

- Robledo-Torres, V., Ramírez-Godina, F., Foroughbakhch-Pournavab, R., Benavides-Mendoza, A., Hernández-Guzmán, G. and Reyes-Valdés, M. H. (2011) Development of tomatillo (Physalis ixocarpa Brot.) autotetraploids and their chromosome and phenotypic characterization. Breed. Sci. 61: 288–293 [Google Scholar]

- Roborgh, R.H.J. (1969) The production of seedless varieties of hop (Humulus lupulus) with colchicine. NZ J Agric. Res. 12: 256–259 [Google Scholar]

- Roy, A.T., Leggett, G. and Koutoulis, A. (2001) In vitro tetraploid induction and generation of tetraploids from mixoploids in hop (Humulus lupulus L.). Plant Cell Rep. 20: 489–495 [Google Scholar]

- Skof, S., Bohanec, B., Kastelec, D. and Luthar, Z. (2007) Spontaneous induction of tetraploidy in hop using adventitious shoot regeneration method. Plant Breed. 126: 416–421 [Google Scholar]

- Sliwinska, E. (2008) Estimation of DNA content in plants using flow cytometry. Advances in Cell Biol. 35: 165–176 [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Q.R., Sun, S.H., Li, L.G. and Bell, R.L. (2009) In vitro colchicine-induced polyploidy plantlet production and regeneration from leaf explants of the diploid pear (Pyrus communis L.) cultivar ‘Fertility’. J. Hortic. Sci. Biotech. 84: 548–552 [Google Scholar]

- Tang, Z.Q., Chen, D.L., Song, Z.J., He, Y.C. and Cai, D.T. (2010) In vitro induction and identification of tetraploid plants of Paulownia tomentosa. Plant Cell Tiss. Organ Cult. 102: 213–220 [Google Scholar]

- Van Duren, M., Mopurgo, R., Dolezel, J. and Afza, R. (1996) Induction and verification of autotetraploids in diploid banana (Musa acuminate) by in vitro techniques. Euphytica 88: 25–34 [Google Scholar]

- Viehmannova, I., Cusimamani, E.F., Bechyne, M., Vyvadilova, M. and Greplova, M. (2009) In vitro induction of polyploidy in yacon (Smallanthus sonchifolius). Plant Cell Tiss. Organ Cult. 97: 21–25 [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z., Dai, H., Xiao, M. and Liu, X. (2008) In vitro induction of tetraploids in Phlox subulata L. Euphytica 159: 59–65 [Google Scholar]