Abstract

Synthetic hexaploid wheat is an effective genetic resource for transferring agronomically important genes from Aegilops tauschii to common wheat. Wide variation in grain size and shape, one of the main targets for wheat breeding, has been observed among Ae. tauschii accessions. To identify the quantitative trait loci (QTLs) responsible for grain size and shape variation in the wheat D genome under a hexaploid genetic background, six parameters related to grain size and shape were measured using SmartGrain digital image software and QTL analysis was conducted using four F2 mapping populations of wheat synthetic hexaploids. In total, 18 QTLs for the six parameters were found on five of the seven D-genome chromosomes. The identified QTLs significantly contributed to the variation in grain size and shape among the synthetic wheat lines, implying that the D-genome QTLs might be at least partly functional in hexaploid wheat. Thus, synthetic wheat lines with diverse D genomes from Ae. tauschii are useful resources for the identification of agronomically important loci that function in hexaploid wheat.

Keywords: allopolyploidization, grain shape, quantitative trait locus, synthetic wheat

Grain size and shape, which are associated with milling quality (Breseghello and Sorrells 2006, Evers et al. 1990), are two of the main targets for wheat breeding. Grain size is mainly characterized by grain weight and area, whereas grain shape means a relative proportion of the main growth axes of the grain (Breseghello and Sorrells 2007, Gegas et al. 2010). Grain shape is generally estimated by length, width, vertical perimeter, sphericity and horizontal axes proportion (Breseghello and Sorrells 2007). During einkorn and tetraploid wheat domestication, wheat dramatically changed from having a relatively small grain with a long, thin shape to a uniform, larger grain with a short, wide shape (Gegas et al. 2010, Okamoto et al. 2012). At hexaploid wheat speciation, a dramatic change in grain shape occurred due to acquisition of nontenacious glumes (Okamoto et al. 2012). During subspecies differentiation of tetraploid and hexaploid wheat, grain size and shape greatly diverged by pleiotropic effects of the differentiation-causal genes (Gegas et al. 2010, Okamoto and Takumi 2013). Many studies have identified quantitative trait loci (QTLs) for grain size and shape in common wheat cultivars and the QTLs have been assigned to various chromosomes (Breseghello and Sorrells 2006, 2007, Gegas et al. 2010, Sun et al. 2009, 2010, Tsilo et al. 2010, Williams et al. 2013). In addition, significant association with one-thousand grain weight has been observed in some wheat orthologs of rice grain size-controlling genes (Jiang et al. 2011, Su et al. 2011, Zhang et al. 2012).

Synthetic hexaploid wheat constitutes an effective genetic bridge for transferring agronomically important genes from Aegilops tauschii to common wheat (Jones et al. 2013). The region presumed as the birthplace of common wheat is narrow relative to the entire range of Ae. tauschii (Dvorak et al. 1998), suggesting that this species has large genetic diversity that is not represented in common wheat (Feldman 2001). Numerous synthetic hexaploid wheat lines have been produced through crosses of the tetraploid cultivar Langdon (Ldn) with 69 Ae. tauschii accessions (Kajimura et al. 2011, Takumi et al. 2009a) followed by chromosome doubling of the interspecific hybrids. Thus, the synthetic hexaploids share identical A and B genomes derived from Ldn and contain diverse D genomes originating from the Ae. tauschii pollen parents. Our previous study has shown that the wide variation in grain shape observed among Ae. tauschii accessions is retained in the hexaploid synthetic wheat lines and that the D genome at least partly affects the grain shape of hexaploid wheat (Okamoto et al. 2012). However, the genetic basis of variation in grain shape within the D genome remains unknown. Here, we conducted QTL analyses for grain size and shape-related traits using four F2 populations of wheat synthetics to identify genetic loci responsible for grain size and shape variation in the hexaploid background.

Materials and Methods

Plant materials

Four F2 mapping populations of synthetic wheat lines, Ldn/PI476874//Ldn/KU-2090, Ldn/KU-2097//Ldn/IG126387, Ldn/PI476874//Ldn/KU-2069 and Ldn/KU-2159//Ldn/IG126387, were used in this study. In our previous studies, 82 independent wheat synthetic lines were produced through unreduced gamete formation in interspecific hybrids obtained by crossing Ldn with 69 different Aegilops tauschii accessions (Kajimura et al. 2011), from which the four mapping populations were produced (Nguyen et al. 2013). The parental lines for the four populations were each selected from wheat synthetics with two distinct genealogical lineages of Ae. tauschii. Based on population structure analysis, Ae. tauschii has been divided into two major lineages, lineage 1 (L1) and lineage 2 (L2) and a minor lineage, HGL17 (Mizuno et al. 2010, Sohail et al. 2012, Wang et al. 2013). PI476874 and IG126387 belong to L1, whereas KU-2069, KU-2090, KU-2097 and KU-2159 to L2. Seeds of the first two F2 populations were sown in November 2010, with population sizes being 99 and 96. The third population (Ldn/PI476874//Ldn/KU-2069) contained 106 F2 individuals and was grown in the 2009–10 season. The last population, Ldn/KU-2159//Ldn/IG126387, with 100 individuals, was grown in the 2011–12 season. The parental line (Ldn/PI476874) of the third population was independently derived from the same cross combination as that of the first population. For each mapping population, all F2 individuals were obtained from single F1 plants. Generation of aneuploids has been observed in the progeny of newly synthesized wheat allohexaploid lines (Mestiri et al. 2010). However, in the present study, we found no missing data in F2 genotyping of SSR markers that are distributed throughout the wheat D genome. Therefore, we could exclude chromosomal instability at least in the four mapping populations. All four F2 populations as well as four plants of each parent were grown individually in pots arranged randomly in a glasshouse of Kobe University as previously reported (Nguyen et al. 2013) and selfed seeds were collected from each F2 individual.

Measurement of grain size and shape

Grain size and shape were measured in each F2 individual and parental line using SmartGrain software ver. 1.2, recently developed for high-throughput phenotyping of rice seeds by the National Institute of Agrobiological Sciences, Japan (Tanabata et al. 2012). Six parameters for grain size and shape, i.e., grain area size (AS), perimeter length (PL), grain length (GL), grain width (GW), length-width ratio (LWR) and circularity (CS), were recorded in at least 50 seeds of most F2 plants according to the SmartGrain protocol. AS indicating the area within the perimeter of grain and CS, grain roundness, were calculated based on the AS and PL values (Tanabata et al. 2012). We also measured one-hundred grain weight (HGW) in each F2 individual. The data were statistically analyzed using JMP software ver. 5.1.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). Pearson’s correlation coefficients were estimated among the parameters measured in each mapping population.

Construction of linkage maps and QTL analysis

To amplify the PCR fragment of the simple sequence repeat (SSR) markers, total DNA was extracted from the parents and F2 individuals. For SSR genotyping, reaction mixtures using 2x Quick Taq HS DyeMix (TOYOBO, Osaka, Japan) were prepared and amplified under the following conditions: 40 cycles of 10 s at 94°C, 30 s at the annealing temperature specific to each SSR marker and 30 s at 68°C. Information on SSR markers and the annealing temperature used for each was obtained from the National BioResource Project (NBRP) KOMUGI web site (http://www.shigen.nig.ac.jp/wheat/komugi/strains/aboutNbrpMarker.jsp) and the GrainGenes web site (http://wheat.pw.usda.gov/GG2/maps.shtml). The PCR products were separated on 2% agarose or 13% nondenaturing polyacrylamide gels and visualized under UV light after staining with ethidium bromide. For polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, the high efficiency genome scanning system (Nippon Eido, Tokyo, Japan) of Hori et al. (2003) was used. A SSR marker-based linkage map for each F2 population exists (Nguyen et al. 2013). Genetic mapping was performed using MAPMAKER/EXP version 3.0b software (Lander et al. 1987). The threshold for log-likelihood (LOD) scores was set at 3.0 and genetic distances were calculated with the Kosambi function (Kosambi 1944).

QTL analyses were carried out by composite interval mapping with Windows QTL Cartographer ver. 2.5 software (Wang et al. 2011) using the forward and backward method. A log-likelihood (LOD) score threshold for each parameter was determined by computing a 1000 permutation test. The percentage of phenotypic variation explained by a QTL for a given parameter and any additive effects were also estimated using this software. Epistatic interactions between QTLs were evaluated using the Multiple Interval Mapping (MIM) method using Bayesian Information Criteria (BIC-M3).

Results and Discussion

Application of SmartGrain software, developed for evaluation of rice seed morphology (Tanabata et al. 2012), allowed convenient measurement of grain size and shape-related parameters in the F2 individuals and parental lines of hexaploid wheat. A recent study showed the usefulness of digital image analysis for identification of QTLs for wheat grain shape (Williams et al. 2013) and we also found this approach to be effective for phenotyping wheat seeds.

The mean values of the parental lines involved in the second and third populations, Ldn/KU-2097//Ldn/IG126387 and Ldn/PI476874//Ldn/KU-2069, differed more in grain size and shape-related parameters than in other populations (Table 1). The seven parameters of grain size and shape were distributed continuously and varied widely in the F2 populations and transgressive segregants were found in most parameters in each population (Supplemental Fig. 1). These results indicated the involvement of multiple loci. Significant positive correlations were observed among AS, PL, GL, GW and HGW in all four F2 populations (Table 2), indicating that these four parameters are associated with grain size. Significant negative correlations were found between GW and LWR and between LWR and CS. Thus, wider grains reduced LWR and increased CS, suggesting that these three parameters are related to grain roundness. These observations implied that grain size and roundness independently control grain shape in wheat.

Table 1.

Parental and F2 population means for seven grain size and shape-related parameters measured in each of the four F2 mapping populations

| Area size (AS) (mm2) | Perimeter length (PL) (mm) | Grain length (GL) (mm) | Grain width (GW) (mm) | Length- width ratio (LWR) | Circularity (CS) | 100-grain weight (HGW) (g) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ldn/PI476874//Ldn/KU-2090 in 2010–2011 season | |||||||

| Ldn/PI476874 | 19.89 ± 1.86* | 20.35 ± 0.72 | 8.55 ± 0.37 | 3.14 ± 0.14 | 2.73 ± 0.15 | 0.60 ± 0.03 | 5.16 ± 0.12 |

| Ldn/KU-2090 | 20.99 ± 1.45 | 21.01 ± 0.85 | 8.80 ± 0.38 | 3.15 ± 0.13 | 2.80 ± 0.16 | 0.59 ± 0.02 | 5.32 ± 0.34 |

| F2 population | 20.33 ± 1.86a | 20.43 ± 1.10a | 8.55 ± 0.52a | 3.16 ± 0.20a | 2.72 ± 0.21a | 0.61 ± 0.03a | 5.04 ± 0.83a |

| Min-max in F2 | 15.59 – 24.52 | 17.15 – 23.55 | 6.89 – 10.16 | 2.58 – 3.51 | 2.24 – 3.61 | 0.50 – 0.69 | 3.19 – 7.02 |

| Ldn/KU-2097//Ldn/IG126387 in 2010–2011 season | |||||||

| Ldn/KU-2097 | 20.11 ± 1.55 | 21.59 ± 0.93 | 9.19 ± 0.45 | 2.85 ± 0.19 | 3.24 ± 0.28 | 0.54 ± 0.03 | 5.90 ± 0.55 |

| Ldn/IG126387 | 18.99 ± 1.28 | 20.31 ± 0.60 | 8.65 ± 0.33 | 3.01 ± 0.18 | 2.89 ± 0.21 | 0.58 ± 0.03 | 4.73 ± 0.02 |

| F2 population | 19.84 ± 1.62a | 21.20 ± 0.97b | 9.01 ± 0.45b | 2.96 ± 0.17b | 3.06 ± 0.21b | 0.55 ± 0.03b | 5.52 ± 0.71b |

| Min-max in F2 | 15.14 – 23.31 | 18.52 – 23.61 | 7.81 – 10.11 | 2.46 – 3.37 | 2.66 – 3.77 | 0.47 – 0.61 | 4.13 – 7.23 |

| Ldn/PI476874//Ldn/KU-2069 in 2009–2010 season | |||||||

| Ldn/PI476874 | 21.16 ± 1.68 | 22.25 ± 1.90 | 9.48 ± 0.59 | 3.05 ± 0.25 | 3.12 ± 0.29 | 0.54 ± 0.05 | 4.28 ± 0.09 |

| Ldn/KU-2069 | 17.80 ± 2.95 | 19.93 ± 2.14 | 8.46 ± 0.95 | 2.86 ± 0.31 | 2.98 ± 0.56 | 0.56 ± 0.06 | 4.50 ± 0.43 |

| F2 population | 18.53 ± 1.83b | 19.95 ± 1.23a | 8.46 ± 0.58a | 2.93 ± 0.17b | 2.89 ± 0.19c | 0.58 ± 0.03c | 4.64 ± 0.71c |

| Min-max in F2 | 14.00 – 23.69 | 16.60 – 23.27 | 6.89 – 10.03 | 2.30 – 3.25 | 2.43 – 3.56 | 0.51 – 0.66 | 3.10 – 6.46 |

| Ldn/KU-2159//Ldn/IG126387 in 2011–2012 season | |||||||

| Ldn/KU-2159 | 18.71 ± 2.35 | 19.76 ± 0.96 | 8.40 ± 0.41 | 2.96 ± 0.38 | 2.83 ± 0.26 | 0.60 ± 0.04 | 5.11 ± 0.10 |

| Ldn/IG126387 | 19.27 ± 1.57 | 20.53 ± 1.01 | 8.82 ± 0.88 | 3.00 ± 0.24 | 2.95 ± 0.41 | 0.57 ± 0.03 | 4.51 ± 0.09 |

| F2 population | 18.41 ± 2.08b | 20.07 ± 1.26a | 8.52 ± 0.55a | 2.93 ± 0.27b | 2.93 ± 0.23c | 0.57 ± 0.04c | 4.50 ± 0.69c |

| Min-max in F2 | 11.44 – 24.71 | 15.76 – 23.83 | 6.79 – 10.08 | 2.08 – 3.51 | 2.39 – 3.93 | 0.44 – 0.65 | 2.90 – 6.19 |

Means with standard deviations.

Difference of each parameter among the four F2 populations was tested by Tukey-Kramer HSD test.

Means ± standard deviations with the same letter were not significantly different (P < 0.05) in each column.

Table 2.

Correlation coefficient (r) matrices for seven parameters measured in four F2 mapping populations

| AS | PL | GL | GW | LWR | CS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ldn/PI476874//Ldn/KU-2090 | ||||||

| PL | 0.8776*** | |||||

| GL | 0.8161*** | 0.9897*** | ||||

| GW | 0.7446*** | 0.3551*** | 0.2627** | |||

| LWR | 0.0221 | 0.4907*** | 0.5772*** | −0.6331*** | ||

| CS | −0.0280 | −0.5014*** | −0.5910*** | 0.6036*** | −0.9828*** | |

| HGW | 0.8911*** | 0.7572*** | 0.7013*** | 0.7003*** | −0.0374 | 0.0159 |

| Ldn/KU-2097//Ldn/IG126387 | ||||||

| PL | 0.8557*** | |||||

| GL | 0.8064*** | 0.9836*** | ||||

| GW | 0.7793*** | 0.3799*** | 0.3133** | |||

| LWR | −0.1059 | 0.4042*** | 0.4734*** | −0.6821*** | ||

| CS | 0.0885 | −0.4327*** | −0.4849*** | 0.6436*** | −0.9708*** | |

| HGW | 0.8403*** | 0.6605*** | 0.5846*** | 0.6900*** | −0.2002 | 0.1644 |

| Ldn/PI476874//Ldn/KU-2069 | ||||||

| PL | 0.9343*** | |||||

| GL | 0.8908*** | 0.9892*** | ||||

| GW | 0.8265*** | 0.6099*** | 0.5345* | |||

| LWR | 0.1769 | 0.4957*** | 0.5771*** | −0.3749*** | ||

| CS | −0.3024* | −0.6164*** | −0.6853*** | 0.2089* | −0.9519*** | |

| HGW | 0.8657*** | 0.7833*** | 0.7559*** | 0.7489*** | 0.0839 | −0.2103* |

| Ldn/KU-2159//Ldn/IG126387 | ||||||

| PL | 0.8428*** | |||||

| GL | 0.7656*** | 0.9768*** | ||||

| GW | 0.8274*** | 0.4204*** | 0.2982* | |||

| LWR | −0.3040* | 0.2384* | 0.3616*** | −0.7745*** | ||

| CS | 0.1500 | −0.4018*** | −0.4905*** | 0.6359*** | −0.9544*** | |

| HGW | 0.8671*** | 0.7410*** | 0.6688*** | 0.6799*** | −0.2197* | 0.1108 |

Levels of significance are indicated by asterisks, * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001.

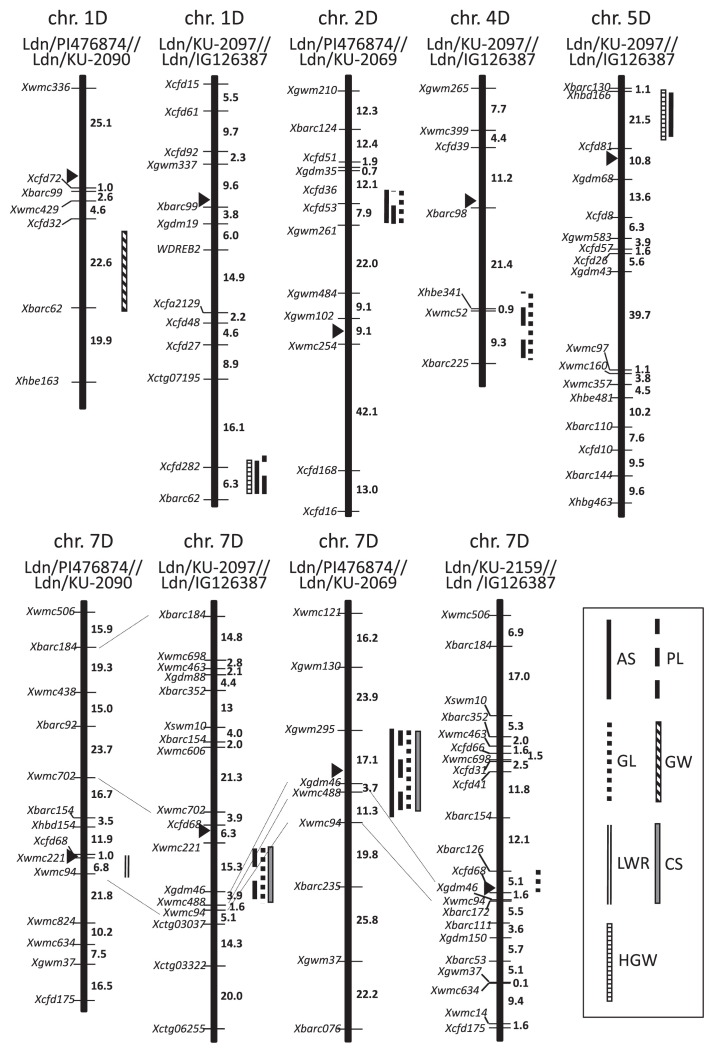

QTLs for all studied grain size and shape-related parameters were detected using the four linkage maps. In total, 18 QTLs, located on five of the D-genome chromosomes, showed significant LOD scores (P < 0.05) (Fig. 1). For AS, PL, GL, GW, LWR, CS and HGW, respectively four, five, five, one, one, two and two QTLs were detected (Table 3). In all four populations, QTLs with high LOD scores for AS, PL, GL, LWR and CS were found at a similar proximal region of chromosome 7D (Fig. 1). The 7D QTLs contributed 3.2–46% of the variation in the five parameters. On the short arm of chromosome 2D, three QTLs for AS, PL and GL were found at the same position in the Ldn/PI476874//Ldn/KU-2069 population. The 2D QTLs contributed 11–16% of the variation. Three QTLs for AS, PL and GW were detected at the same position on the long arm of chromosome 1D. The 1D QTLs explained 13–16% of the variation in the Ldn/PI476874//Ldn/KU-2090 and Ldn/KU-2097//Ldn/IG126387 populations. Two QTLs for PL and GL detected on chromosome 4D respectively explained 22 and 30% of the variation in the Ldn/KU-2097//Ldn/IG126387 population. Two QTLs for AS and HGW were found on chromosome 5D and contributed 19–21% of the AS and HGW variation in the Ldn/KU-2097//Ldn/IG126387 population. No epistatic interaction between the detected QTLs was observed in the four mapping population.

Fig. 1.

Linkage maps and positions of QTLs for grain size and shape in the four populations of wheat synthetics. QTLs with LOD scores above the threshold are indicated and genetic distances (in centimorgans) are given to the right of each chromosome. Black arrowheads indicate the putative positions of centromeres.

Table 3.

A summary of QTLs for grain size and shape-related parameters that were identified in four F2 mapping populations

| Parameter | Chromosome | Map location | LOD score | LOD threshold | Contribution (%) | Additive effect* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ldn/PI476874//Ldn/KU-2090 | ||||||

| GW | 1D | Xcfd32-Xbarc62 | 8.36 | 3.3 | 14.67 | −0.26 |

| LWR | 7D | Xwmc221-Xwmc94 | 3.23 | 3.2 | 7.07 | 0.21 |

| Ldn/KU-2097//Ldn/IG126387 | ||||||

| AS | 1D | Xcfd282-Xbarc62 | 3.58 | 3.3 | 16.35 | 0.93 |

| AS | 5D | Xhbd166-Xcfd81 | 6.15 | 3.3 | 19.41 | −0.24 |

| PL | 1D | Xcfd282-Xbarc62 | 3.28 | 3.2 | 13.26 | 0.46 |

| PL | 4D | Xhbe341-Xbarc225 | 6.25 | 3.2 | 30.41 | 0.91 |

| PL | 7D | Xwmc221-Xgdm46 | 8.11 | 3.2 | 31.01 | −0.87 |

| GL | 4D | Xhbe341-Xbarc225 | 5.10 | 3.2 | 22.00 | 0.33 |

| GL | 7D | Xwmc221-Xgdm46 | 7.11 | 3.2 | 21.48 | −0.32 |

| CS | 7D | Xwmc221-Xgdm46 | 4.24 | 3.5 | 22.57 | 0.02 |

| HGW | 1D | Xcfd282-Xbarc62 | 3.69 | 3.0 | 12.93 | 4.30 |

| HGW | 5D | Xhbd166-Xcfd81 | 6.73 | 3.0 | 20.57 | −0.20 |

| Ldn/PI476874//Ldn/KU-2069 | ||||||

| AS | 2D | Xcfd36-Xcfd53 | 4.06 | 3.1 | 15.86 | −0.96 |

| AS | 7D | Xgwm295-Xwmc488 | 7.5 | 3.1 | 34.51 | 1.30 |

| PL | 2D | Xcfd36-Xcfd53 | 3.71 | 3.2 | 12.32 | −0.61 |

| PL | 7D | Xgwm295-Xwmc488 | 8.73 | 3.2 | 42.56 | 1.03 |

| GL | 2D | Xcfd36-Xcfd53 | 3.22 | 3.2 | 10.82 | −0.26 |

| GL | 7D | Xgwm295-Xwmc488 | 8.81 | 3.2 | 46.01 | 0.51 |

| CS | 7D | Xgwm295-Xwmc488 | 4.57 | 3.3 | 21.38 | −0.015 |

| Ldn/KU-2159//Ldn/IG126387 | ||||||

| GL | 7D | Xbarc126-Xcfd68 | 3.75 | 3.2 | 3.24 | −0.15 |

Positive and negative effects mean that L2 (KU-2069, KU-2090, KU-2097, KU-2159)- and L1 (PI476874, IG126387)-derived alleles increased in values of each parameter, respectively.

To study the effects of the identified QTLs, data for each grain size and shape-related parameter were grouped based on the marker genotypes around the QTL regions of each F2 individual. There were significant (P < 0.05) differences in the parameters among genotypes at most of the identified QTLs (Supplemental Fig. 2). Among genotypes, no significant differences were observed in only four QTLs, the 7D QTL for LWR in Ldn/PI476874//Ldn/KU-2090, the 4D QTL for GL and the 7D QTL for CS in Ldn/KU-2097//Ldn/IG126387 and the 2D QTL for GL in Ldn/PI476874//Ldn/KU-2069. Development of markers linked more tightly to these QTLs could help to detect differences. For the 2D QTLs for AS and PL, F2 individuals with heterozygous and Ldn/KU-2069-homozygous alleles showed significantly lower values for these parameters than those with the Ldn/PI476874-homozygous allele. In contrast, F2 individuals with heterozygous and Ldn/KU-2069-homozygous alleles for the 7D QTLs for AS, PL and GL showed significantly higher values in the corresponding parameters. In the Ldn/KU-2097//Ldn/IG126387 population, individuals with Ldn/IG126387-homozygous alleles for the 7D QTLs showed significantly higher values of PL and GL than the Ldn/KU-2097-homozygous alleles.

In similar regions of chromosome 7D, QTLs for grain size and shape were found using the four mapping populations. One parental synthetic wheat line for the four populations was selected from L1-derived synthetic wheat lines and another from L2-derived synthetics. Many phenotypic traits showed geographical clines in the Ae. tauschii populations, and difference of the dispersal patterns of the Ae. tauschii accessions was observed between L1 and L2 (Matsuoka et al. 2009, Takumi et al. 2009b). Only the L1 accessions were distributed and spikelets tended to be small in eastern habitats (Matsuoka et al. 2009, Mizuno et al. 2010). Therefore, the 7D QTLs were expected to contribute to divergence of the two genealogical lineages. However, the allelic effects of the 7D QTLs in each mapping population did not necessarily correspond to lineage divergence (Table 3). Wheat spikelet morphology is significantly related to grain size and shape (Okamoto et al. 2012, Okamoto and Takumi 2013), and large variation in spikelet morphology is present in the Ae. tauschii gene pool (Matsuoka et al. 2009). However, the relationship between grain and spikelet morphology and lineage divergence of the Ae. tauschii accessions is still unclear. The effects of the 7D QTLs identified in the present study on spikelet shape-related traits should be studied at the diploid Ae. tauschii level. In an F2 population between a common wheat cultivar and a synthetic wheat line, QTLs for grain and spikelet shape and spikelet density were reported in a similar region of chromosome 7D (Okamoto et al. 2012). Barley spike density is partly under the control of dense spike-ar (dsp.ar), assigned to the centromeric region of chromosome 7H (Shahinnia et al. 2012). These observations suggest that the 7D and 7H centromeric regions might contribute to intraspecific variations in spike, spikelet and grain morphology in both wheat and barley. The orthologous relationship between dsp.ar and the QTLs we identified should be clarified by further study.

On 2DS, QTLs for grain length-related parameters were found in the Ldn/PI476874//Ldn/KU-2069 population. Earlier, a grain yield QTL related to photoperiodic insensitivity for flowering, as well as a QTL for heading time, was detected around the Xgwm261 region, near the Ppd-D1 locus, on 2DS in a mapping population derived from a cross between a winter wheat cultivar and a synthetic wheat line (Narasimhamoorthy et al. 2006). Our previous study using an F2 population between Norin 61 and Ldn/PI476874 also detected a QTL for grain shape with a high LOD score at the tenacious glume locus Tg-D1 region of 2DS (Okamoto et al. 2012). The precise position of the 2D QTLs for AS, PL and GL on 2DS should be determined in future study.

The QTLs on chromosomes 1D, 4D and 5D seemed to be novel loci associated with grain size and shape in wheat because to our knowledge, no wheat QTLs for such traits have been reported in these chromosomal regions. These 1D, 4D and 5D QTL regions showed chromosomal synteny to a distal part of the long arm on chromosome 5, a centromeric region of chromosome 3 and a distal part of the long arm on chromosome 12 in rice, respectively. A QTL for grain length (qGL3), which encodes a putative protein phosphatase with Kelch-like repeat domain (OsPPLK1), was found at the centromeric region of rice chromosome 3 (Qi et al. 2012, Zhang et al. 2012). Recently, QTLs for one-thousand grain weight were also identified at the distal parts of the long arms on rice chromosomes 5 and 12 (Marathi et al. 2012). However, relationship between these rice and our identified QTLs was still unclear. Thus, synthetic wheat lines are useful resources for the identification of agronomically important loci that function in hexaploid wheat. It has been considered that the A genome predominantly controls morphological traits including spike shape, grain size and shape and thickness of empty glumes in allohexaploid wheat (Peng et al. 2003, Zhang et al. 2011). However, the QTLs identified in the present study significantly contributed to the variation in grain shape among the synthetic wheat lines, implying that the D-genome QTLs for grain size and shape might be at least partly functional in hexaploid wheat and useful for wheat improvement. However, effects of the QTLs on grain size and shape of common wheat might be limited due to the predominant effects of the A genome on wheat morphology. Therefore, in studies following transfer of the identified QTLs to common wheat cultivars, their expression should be carefully analyzed.

To increase the D-genome diversity in common wheat, the natural variations within Ae. tauschii populations are important resources (Jones et al. 2013). In the present study, we successfully found novel QTLs controlling the grain size and shape variation in the D genome of allohexaploid wheat. Our previous study also demonstrated identification of novel QTLs in the D genome for flowering-related traits using the mapping populations of synthetic wheat lines (Nguyen et al. 2013). The wheat synthetics established in our previous study (Kajimura et al. 2011) are thus valuable resources not only to study expression of the D-genome variation in various traits but also to identify agriculturally important loci that function in the hexaploid genetic background.

Supplementary Materials

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan (Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (B) No. 25292008) and the Elizabeth Arnold Fuji foundation to ST.

Literature Cited

- Breseghello, F. and Sorrells, M.E. (2006) Association mapping of kernel size and milling quality in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) cultivars. Genetics 172: 1165–1177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breseghello, F. and Sorrells, M.E. (2007) QTL analysis of kernel size and shape in two hexaploid wheat mapping populations. Field Crops Res. 101: 172–179 [Google Scholar]

- Dvorak, J., Luo, M.C., Yang, Z.L. and Zhang, H.B. (1998) The structure of the Aegilops tauschii gene pool and the evolution of hexaploid wheat. Theor. Appl. Genet. 97: 657–670 [Google Scholar]

- Evers, A.D., Cox, R.I., Shaheedullah, M.Z. and Withey, R.P. (1990) Predicting milling extraction rate by image analysis of wheat grains. Asp. Appl. Biol. 25: 417–426 [Google Scholar]

- Feldman, M. (2001) Origin of cultivated wheat. In: Bonjean, A.P. and Angus, W.J. (eds.) The World Wheat Book: A History of Wheat Breeding, Lavoisier Publishing, rue Lavoisier, Paris, pp. 3–53 [Google Scholar]

- Gegas, V.C., Nazari, A., Griffiths, S., Simmonds, J., Fish, L., Orford, S., Sayers, L., Doonan, J.H. and Snape, J.W. (2010) A genetic frame work for grain size and shape variation in wheat. Plant Cell 22: 1046–1056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hori, K., Kobayashi, T., Shimizu, A., Sato, K. and Kawasaki, S. (2003) Efficient construction of high-density linkage map and its application to QTL analysis in barley. Theor. Appl. Genet. 107: 806–813 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Q., Hou, J., Hao, C., Wang, L., Ge, H., Dong, Y. and Zhang, X. (2011) The wheat (T. aestivum) sucrose synthase 2 gene (TaSus2) active in endosperm development is associated with yield traits. Func. Int. Genomics 11: 49–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones, H., Gosman, N., Horsnell, R., Rose, G.A., Everst, L.A., Bentley, A.R., Tha, S., Uauy, C., Kowalski, A., Novoselovic, D.et al. (2013) Strategy for exploiting exotic germplasm using genetic, morphological, and environmental diversity: the Aegilops tauschii Coss. example. Theor. Appl. Genet. 126: 1793–1808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kajimura, T., Murai, K. and Takumi, S. (2011) Distinct genetic regulation of flowering time and grain-filling period based on empirical study of D-genome diversity in synthetic hexaploid wheat lines. Breed. Sci. 61: 130–141 [Google Scholar]

- Kosambi, D.D. (1944) The estimation of map distance from recombination values. Ann. Eugen. 12: 172–175 [Google Scholar]

- Lander, E.S., Green, P. and Abrahamson, J. (1987) MAPMAKER: an interactive computer package for constructing primary genetic linkage maps of experimental and natural populations. Genomics 1: 174–181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marathi, B., Guleria, S., Mohapatra, T., Parsad, R., Mariappan, N., Kurungara, V.K., Atwal, S.S., Prabhu, K.V., Singh, N.K. and Singh, A.K. (2012) QTL analysis of novel genomic regions associated with yield and yield related traits in new plant type based recombinant inbred lines of rice (Oryza sativa L.). BMC Plant Biol. 12: 137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuoka, Y., Nishioka, E., Kawahara, T. and Takumi, S. (2009) Genealogical analysis of subspecies divergence and spikelet-shape diversification in central Eurasian wild wheat Aegilops tauschii Coss. Plant Syst. Evol. 279: 233–244 [Google Scholar]

- Mestiri, I., Chagué, V., Tanguy, A.M., Huneau, C., Huteau, V., Belcram, H., Coriton, O., Chalhoub, B. and Jahier, J. (2010) Newly synthesized wheat allohexaploids display progenitor-dependent meiotic stability and aneuploidy but structural genomic additivity. New Phytol. 186: 86–101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizuno, N., Yamasaki, M., Matsuoka, Y., Kawahara, T. and Takumi, S. (2010) Population structure of wild wheat D-genome progenitor Aegilops tauschii Coss.: implications for intraspecific lineage diversification and evolution of common wheat. Mol. Ecol. 19: 999–1013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narasimhamoorthy, B., Gill, B.S., Fritz, A.K., Nelson, J.C. and Brown-Guedira, G.L. (2006) Advanced backcross QTL analysis of a hard winter wheat × synthetic wheat population. Theor. Appl. Genet. 112: 787–796 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, T.A., Iehisa, J.C. M., Kajimura, T., Murai, K. and Takumi, S. (2013) Identification of quantitative trait loci for flowering-related traits in the D genome of synthetic hexaploid wheat lines. Euphytica 192: 401–412 [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto, Y., Kajimura, T., Ikeda, T.M. and Takumi, S. (2012) Evidence from principal component analysis for improvement of grain shape- and spikelet morphology-related traits after hexaploid wheat speciation. Genes Genet. Syst. 87: 299–310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto, Y. and Takumi, S. (2013) Pleiotropic effects of the elongated glume gene P1 on grain and spikelet shape-related traits in tetraploid wheat. Euphytica 194: 207–218 [Google Scholar]

- Peng, J., Ronin, Y., Fahima, T., Röder, M.S., Li, Y., Nevo, E. and Korol, A. (2003) Domestication quantitative trait loci in Triticum dicoccoides, the progenitor of wheat. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100: 2489–2494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi, P., Lin, Y.S., Song, X.J., Shen, J.B., Huang, W., Shan, J.X., Zhu, M.Z., Jiang, L., Gao, J.P. and Lin, H.X. (2012) The novel quantitative trait locus GL3.1 controls rice grain size and yield by regulating Cyclin-T1;3. Cell Res. 22: 1666–1680 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shahinnia, F., Druka, A., Franckowiak, J., Morgante, M., Waugh, R. and Stein, N. (2012) High resolution mapping of Dense spike-ar (dsp.ar) to the genetic centromere of barley chromosome 7H. Theor. Appl. Genet. 124: 373–384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sohail, Q., Shehzad, T., Kilian, A., Eltayeb, A.E., Tanaka, H. and Tsujimoto, H. (2012) Development of diversity array technology (DArT) markers for assessment of population structure and diversity in Aegilops tauschii. Breed. Sci. 62: 38–45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su, Z., Hao, C., Wang, L., Dong, Y. and Zhang, X. (2011) Identification and development of a functional marker of TaGW2 associated with grain weight in bread wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Theor. Appl. Genet. 122: 211–223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun, X.Y., Wu, K., Zhao, Y., Kong, F.M., Han, G.Z., Jiang, H.M., Huang, X.J., Li, R.J., Wang, H.G. and Li, S.S. (2009) QTL analysis of kernel shape and weight using recombinant inbred lines in wheat. Euphytica 165: 615–624 [Google Scholar]

- Sun, X., Marza, F., Ma, H., Carver, B.F. and Bai, G. (2010) Mapping quantitative trait loci for quality factors in an inter-class cross of US and Chinese wheat. Theor. Appl. Genet. 120: 1041–1051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takumi, S., Naka, Y., Morihiro, H. and Matsuoka, Y. (2009a) Expression of morphological and flowering time variation through allopolyploidization: an empirical study with 27 wheat synthetics and their parental Aegilops tauschii accessions. Plant Breed. 128: 585–590 [Google Scholar]

- Takumi, S., Nishioka, E., Morihiro, H., Kawahara, T. and Matsuoka, Y. (2009b) Natural variation of morphological traits in wild wheat progenitor Aegilops tauschii Coss. Breed. Sci. 59: 579–588 [Google Scholar]

- Tanabata, T., Shibaya, T., Hori, K., Ebana, K. and Yano, M. (2012) SmartGrain: high-throughput phenotyping software for measuring seed shape through image analysis. Plant Physiol. 160: 1871–1880 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsilo, T.J., Hareland, G.A., Simsek, S., Chao, S. and Anderson, J.M. (2010) Genome mapping of kernel characteristics in hard red spring wheat breeding lines. Theor. Appl. Genet. 121: 717–730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J., Luo, M.C., Chen, Z., You, F.M., Wei, Y., Zheng, Y. and Dvorak, J. (2013) Aegilops tauschii single nucleotide polymorphisms shed light on the origins of wheat D-genome genetic diversity and pinpoint the geographic origin of hexaploid wheat. New Phytol. 198: 925–937 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S., Basten, C.J. and Zeng, Z.B. (2011) Windows QTL cartographer 2.5. Department of Statics, North Carolina State University, Raleigh, NC: http://statgen.ncsu.edu/qtlcart/WQTLCart.htm [Google Scholar]

- Williams, K., Munkvold, J. and Sorrells, M. (2013) Comparison of digital image analysis using elliptic Fourier descriptors and major dimensions to phenotype seed shape in hexaploid wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Euphytica 190: 99–116 [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L., Zhao, Y.L., Gao, L.F., Zhao, G.Y., Zhou, R.H., Zhang, B.S. and Jia, J.Z. (2012) TaCKX6-D1, the ortholog of rice OsCKX2, is associated with grain weight in hexaploid wheat. New Phytol. 195: 574–584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X., Wang, J., Huang, J., Lan, H., Wang, C., Yin, C., Wu, Y., Tang, H., Qian, Q., Lin, J.et al. (2012) Rare allele of OsPPKL1 associated with grain length causes extra-large grain and a significant yield increase in rice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 109: 21534–21539 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z., Belcram, H., Gomicki, P., Charles, M., Just, J., Huneau, C., Magdelenat, G., Couloux, A., Samain, S., Gill, B.S.et al. (2011) Duplication and partitioning in evolution and function of homoeologous Q loci governing domestication characters in polyploid wheat. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 108: 18737–18742 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.