Abstract

In the last couple of decades, substantial progress has been made in the development of transgenic mouse models developing amyloid-β deposits and/or neurofibrillary tangles. These mouse models of Alzheimer’s disease and related disorders provide an excellent tool for investigating etiology, pathogenic mechanisms and potential treatments. An essential component of their characterization is a detailed behavioral assessment, which clarifies the functional consequences of these pathologies. We have selected and refined a series of cognitive and sensorimotor tasks that are ideal for studying these models and the efficacy of various treatments.

1. Introduction

Several transgenic mouse models have been developed that show age-related deposition of amyloid-β (Aβ) and/or tau aggregates as observed in Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and related disorders. These models are very useful for clarifying the etiology and pathogenesis of these diseases and to evaluate potential therapeutic interventions.

Numerous mouse models have been developed with familial AD mutations in the amyloid precursor protein and/or the presenilins, with most if not all developing cognitive impairments with age (1;2). Tangle mouse models appeared later after the first tau mutations were discovered, with at least some of these developing motor impairments because of tau pathology in the spinal cord and brain stem (3). This feature precludes thorough cognitive characterization, which requires extensive maze navigation but allows rapid evaluation of the progression of the pathology and therapy efficacy by using tests for motor coordination (4). Several other tangle models have now been generated and shown to develop cognitive impairments (for example see ref. (5;6)).

In our laboratory, we have primarily characterized the functional impairments of the following models, Tg2576 (7), JNPL3 (8), and htau/PS1 (6), with or without a therapeutic intervention. Towards this end, we have used two types of behavioral tests: 1) Sensorimotor tasks to: a) Verify that any treatment related effects observed in the cognitive tasks cannot be explained by differences in sensorimotor abilities, or; b) As the primary functional measure of models that develop motor impairments (such as JNPL3). These include: Traverse Beam, Locomotor Activity and Rotarod; 2) Cognitive tests, including one designed to test short term memory (Object Recognition) and two that test spatial/working memory (Closed Field Symmetrical Maze and Radial Arm Maze).

2. Materials

2.1 Traverse Beam

Wooden beam (1.1cm wide and 50.8 cm long)

Goal box is a shaded rectangular box made of plastic material and open on one end (length:16 cm; height and width: 7 cm)

Light socket and a bulb (30W)

Two support rods and clamps, such as standard laboratory equipment support rods with tripod base and corresponding clamps to hold the beam.

Soft cushion to be placed underneath the entire beam.

Mirror allows the observation of footslips on the side that is not facing the observer.

2.2. Rotarod

Rotarod 7650 accelerating model. UgoBasile, Varese, Italy. Various other models can be Used, some of which allow several animals to be tested simultaneously.

Soft cushion to be placed under the rotating rod.

2.3 Locomotor Activity

Circular open field (75 cm in diameter)

Tracking system. (such as Hamilton-Kinder Smart-frame Photobeam System or ANY-MAZE, San Diego Instruments, San Diego, CA, or Noldus Ethovision XT, Noldus, The Netherlands)

2.4. Object Recognition

Square shaped open field box (48 cm square with 18 cm high walls made from Plexiglas)

Tracking system (such as Hamilton-Kinder Smart-frame Photobeam System or ANY MAZE, San Diego Instruments, or Noldus Ethovision XT, Noldus, The Netherlands).

Objects (such as 250 ml Erlenmyer flasks, colored soda/beer bottles and cans)

2.5. Closed Field Symmetrical Maze

This apparatus is a square open field box (61 cm square, divided into 36, 9.5 cm squares colored in white as shown in Fig. 5

Walls constructed from wood painted in grey

Different lengths of barriers (length: 20 cm, 30.5 cm, 40.5 cm; thickness: 1 cm; height: 8 cm).

Saccharine solution (0.1%) colored with green food color (McCormick & Co. Inc., MD, USA)

Fruit loop cereal or similar type of a sweet cereal.

Figure 5. Closed Field Symmetrical Maze.

A-B) Measures spatial/working memory. Schematic panels 1 to 7 represent seven problems graded in difficulty to test the spatial and working memory of mice. The barriers are placed in the field in symmetrical patterns, so that mice face the same turns going in either direction within a given problem, which eliminates intertrial handling (10).

2.6. Radial Arm Maze

An eight-arm elevated radial maze, constructed from Plexiglas or similar material.

Each arm is 35 cm long, 7 cm wide with a water/food cup 1 cm in diameter positioned at the end of each arm.

Sidewalls (15 cm high that extend 12 cm into each arm)

The central area is an octagonal shaped hub (14 cm in diameter)

Eight clear guillotine doors constructed from Plexiglas.

The maze is elevated 75 cm above floor level

Saccharine solution (0.1%) colored with green food color (McCormick & Co. Inc., MD, USA)

Fruit loop cereal or similar type of a sweet cereal.

3. Methods

Before enrolling an animal in a study, all protocols must be approved by institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC).

It is necessary to habituate/train animals in the apparatus, prior to behavioral testing, and the mice should always be adapted to the room and its light intensity. In all tests, the level of light is kept relatively low with the use of a dimmer or screens. It is important as well to minimize distracting odors by cleaning each equipment and related objects with water and a 50–70 % alcohol solution after each animal’s run of the test. Subsequent drying of the surface with tissue shortens the interval between animals. Finally, close attention should be given to possible visual deficits which are relatively common in mice. Those animals should obviously not be included in tests that require intact sight. Certain strains are prone to having a mutation that causes retinal degeneration, and its presence can be detected by PCR (9).

3.1. Sensorimotor tests

One major objective of performing sensorimotor tasks is to verify that the outcome in cognitive tasks, which require maze running, cannot be explained by differences in sensorimotor abilities. These tasks are also ideal as a primary measure in mice that develop motor impairments such as the JNPL3 model.

3.1.1. Traverse Beam

This task tests balance and general motor coordination (Fig. 1). Mice are assessed by measuring their ability to traverse a narrow wooden beam to reach a goal box [modification of (12) which specifically examines hind limb function. The mice are placed on a 1.1 cm wide beam 50.8 cm long, suspended 30 cm above a padded surface by two identical columns. Attached at one end of the beam is a darkened goal box. The animals are habituated to the apparatus one day before test. Mice are placed on the beam and are then monitored for a maximum of 60 s. The number of foot slips each mouse commits before falling or reaching the goal box is recorded for each of four successive trials (see Note 1). A mirror allows the observation of foot slips on the side that is not facing the observer. The average number of foot slips for all four trials is calculated and recorded. These foot slips are errors in the test and are recorded numerically (see Note 2). To prevent injury from falling, a soft foam cushion is always kept underneath the beam.

Figure 1. Traverse Beam.

Mice are placed on a wooden beam and the number of foot slips each mouse makes before reaching the goal box is recorded in four trials (4;10;11).

3.1.2. Rotarod

The animal is placed onto the rod (diameter 3.6 cm) apparatus to measure forelimb and hindlimb motor coordination and balance (Rotarod 7650 accelerating model; Ugo Basile, Biological Research Apparatus, Varese, Italy; (13,14; Fig. 2). The animals are habituated to the apparatus by receiving training sessions of two trials, a sufficient number to reach a baseline level of performance. The mice are then tested an additional three times, increasing the speed of the rotating rod throughout the trial. During habituation and testing, the rotating rod is set at 1.0 r.p.m. The speed of the rotation is gradually increased at 30 s intervals. A soft foam cushion is placed beneath the apparatus to prevent potential injury from falling. Each animal is tested for three sessions total, with each session separated by 15 min, and measures are taken for latency to fall or invert (by clinging) from the top of the rotating barrel (see Note 2).

Figure 2. Rotarod.

Mice are placed on the rotating rod (1.5 rpm) when habituated and its rotating speed raised every 30 s by 0.5 rpm. Each mouse is tested three times with 15 minutes between trials. Measures are taken for latency to fall off the rod (4;10).

3.1.3. Locomotor Activity

A tracking system such as the Hamilton–Kinder Smart-Frame Photobeam System (San Diego Instruments) is used to make a video recording of animal’s activity over a designated period of time (see Note 3; Fig. 3). Exploratory locomotor activity is recorded in a circular open field measuring 75 cm in diameter (see Note 4). Mice are habituated in a session in which they are allowed to explore the open field for 15 min. A video camera mounted in the ceiling above the chamber automatically records movements in the open field in each dimension (i.e. x, y, and z planes). The total distance is measured in centimeters (cm) travelled. The duration of the test is 15 min. Results are reported based on distance travelled (cm), mean resting time (s), and velocity (average and maximum, cm/s) of the mouse.

Figure 3. Locomotor Activity.

Recorded in a circular open field measuring 75 cm in diameter using a video tracking system. Distance (cm), mean resting time (s) and velocity (average and maximum (cm/s) are calculated (4;6;10).

3.2. Cognitive tests

3.2.1. Object Recognition

The spontaneous object recognition test measures short-term memory and is conducted in a square-shaped open-field box (48 cm square, with 18 cm-high walls constructed from black Plexiglas), raised 50 cm from the floor.

Mice are individually habituated in a session in which they are allowed to explore in the open field two identical objects for 15 min (Fig. 4A). These objects are placed diagonally in the center of two zones. Twenty four h later this procedure is repeated with two novel identical objects (see Note 5; Fig. 4B). For any given trial, the objects in a pair are about 15–16 cm high, and composed of the same material so that they cannot readily be distinguished by olfactory cues. The amount of time spent exploring each object within a defined zone of the arena is automatically monitored by a tracking system (San Diego Instruments, San Diego, CA) (Fig. 4C). At the end of the training phase, the mouse is removed from the box for the duration of the retention delay (3 h).

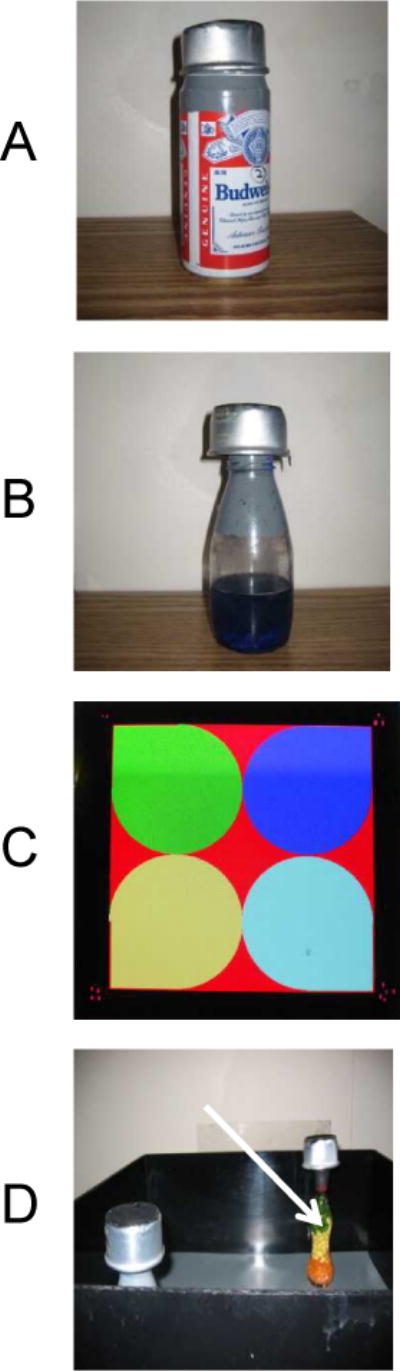

Figure 4. Object Recognition.

Measures short memory in an open field box (48 cm square). Mice are habituated to explore different objects within the box, such as those depicted in A and B. (C) The amount of time spent exploring each object within a defined zone of the arena is measured by a tracking system (4;6). (D) During retention test, one of the familial objects is replaced by a novel object (arrow).

Normal mice remember a specific object after a delay of at least 3 h and spend the majority of their time (about 70%) investigating the novel object during the retention trial. During retention tests, one of the previous familiar objects used during training is replaced by a second novel object, after which the animal is placed in the center of the box and allowed to explore freely for 6 min (see Note 6; Fig. 4D). The time spent exploring the novel and familiar objects is recorded for 6 min. The percentage short-term memory score is the time spent exploring any one of the two objects (training session) compared with the novel one (retention session).

3.2.2. Closed Field Symmetrical Maze

This apparatus is a rectangular field 61 cm square with 9 cm high walls divided into 36, 9.5 cm squares and covered by a clear Plexiglas top (Fig. 5). Endboxes, each 11 × 16 × 9 cm (width × depth × height), are situated at diagonal corners of the field The symmetrical maze (15) is a modification of the Hebb–Williams (16) and Rabinovitch–Rosvold (17) type of tests, and we have further modified this test (10). The main difference is that each end-compartment now functions as both a startbox and a goalbox, and the mice run in opposite direction on alternate trials, thereby eliminating intertrial handling. The barriers are placed in the field in symmetrical patterns, so that mice face the same turns going in either direction within a given problem. Twenty four hours prior to testing, the mice are adapted to a water restriction schedule (2 h daily access to water; see Note 7. The mice are given at least two adaptation sessions prior to the beginning of testing. In the first session, each animal is given 0.1% saccharine flavored water in the goal box for 10 min. In the second habituation session 24 h later, the mouse is placed in the start chamber and permitted to explore the field and enter the goal box, in which the saccharine solution reward (0.05 mL) is available (see Note 8). When the mice are running reliably from the start chamber to the goal box, they are given three practice sessions on simple problems (24 h apart); in which one or two barriers are placed in different positions in the field so as to obstruct direct access to the goal box (see Note 9). Formal testing consists of the presentation of three to seven problems graded in difficulty (Fig. 5). One problem is presented per day and the mice are given five trials on each problem with a wait period of 2 min between trials. Performance is scored manually by the same observer in terms of errors (i.e. entries and reentries into designated error zones) and the time needed to complete each trial.

3.2.3. Radial arm maze

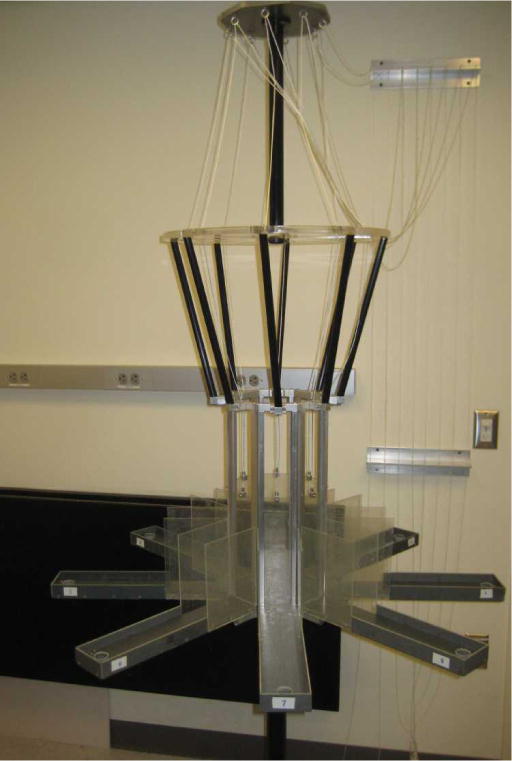

Spatial learning can also be evaluated in an eight-arm radial maze (Fig. 6). Apparatus is an eight-arm elevated radial maze constructed from Plexiglas or similar material. Each arm is 35 cm long and 7 cm wide with a water/food cup 1 cm in diameter positioned at the end of each arm. Sidewalls, 15 cm high, extend 12 cm into each arm to prevent animals from crossing between arms. The height of the remaining sidewalls is 1.5 cm. The central area is an octagonal shaped hub 14 cm in diameter. Clear Plexiglas guillotine doors, operated remotely by a pulley system control access to the arms. The maze is elevated 75 cm above floor level and situated in a room in which several distinctive objects of a constant location serve as extra maze cues. Prior to testing, mice are adapted to a water or food restriction schedule. If a water restriction is used, water is restricted for 24 h before adapting the mice, and during the adaptation/testing period (2 h daily access to water, see Note 7), If a food restriction is used, body weight should be maintained at 90–92% of ad libitum levels (see Note 10). The mice are first adapted in a Y maze for 2 days, and thereafter, in the eight-arm maze for 2 to 3 days. Mice are initially adapted to the test procedure by allowing them free exploration of the maze for 10 min. During adaptation, drops of 0.1% saccharine solution (water restriction schedule) or pieces of Fruit Loop cereal (food restriction schedule) are sprinkled over the floor of the maze and the doors of the Radial Arm Maze are raised and lowered periodically to accustom the animals to the sound associated with their operation. Adaptation is continued until animals are consuming the sugar solution or eating the cereal and freely entering all arms. This typically requires 2 sessions (one day apart). On the training trials, a few drops of the saccharine solution or one piece of cereal is placed in the well of each of the eight arms and the trial is begun by placing the mouse in the central area and raising all doors. When an arm is entered all doors are lowered. After the sugar solution is consumed or the food is eaten, the door to that arm is raised allowing the mouse to return to the central arena. After a 5 sec interval the next trial is initiated by again raising all of the doors simultaneously. This procedure is continued until the animal has entered all arms or until 15 min has elapsed (see Note 9). Daily acquisition sessions are continued for 9–10 days. An error is defined as a reentry to a previously visited arm.

Figure 6. Radial Arm Maze.

Measures spatial/working memory. Apparatus is an eight arm elevated radial maze with access to the arms controlled by guillotine doors operated by a pulley system (6;10).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants AG032611 and AG020197 and the Alzheimer’s Association.

Footnotes

If an animal falls while performing the traverse beam test, it should be placed back on the beam to continue the test.

It is often difficult for obese animals (>35 grams) to complete certain tests (traverse beam, rotarod). It is advised to emphasise alternative tests if many of the animals fall into this category or exclude these animals from the study.

Locomotor activity can be analyzed by several tracking programs. We originally used the SMART program from San Diego Instruments which has now been replaced by ANY-MAZE. More recently, we have been using Noldus Ethovision XT (Noldus, The Netherlands)

Grey colored open field gives a good flexibility in tracking mice with different fur colors. Marking the fur with a contrasting non-toxic marker may facilitate tracking.

For example, each bottle has blue water in the bottom third portion; the middle of the bottle is clear and the upper third is painted in grey (See Fig. 4B). When a black/brown mouse is being tested, the surface of the apparatus is white and a white cap/can (height approx. 3.5 cm) is placed on the top of the objects to allow tracking of the animal. Conversely, darker surface and cap are used when white mice are being tracked (Fig. 4D).

We have used as a novel object colored glassware (shown by arrow in Fig 4D) that is different in shape and color from objects used for training sessions (see Fig. 4C)

In our experience, it is better for reinforcement to restrict water rather than food. The mice do better under these conditions. This approach also eliminates confounding variables associated with trail of food morsels in the maze that can distract the mice and/or aid them in finding their way to the reinforcer.

If the mice do not drink the water, this session is repeated the following day, and again the next day if needed which is rare.

If the animal is not navigating the maze during habituation, it is encouraged with a gentle touch. If this does not help, after repeated attempts and continued habituation, the mouse is excluded from the study.

This can be achieved by depriving the mice of food for 24 h on the first day of the habituation and then maintain the animals on 2.0 to 2.5 g of chow per day for the duration of the study, making adjustments based on body weights recorded 2–3 times per week. Mice maintain good health on this schedule and do not lose additional body weight over the testing period.

References

- 1.Ashe KH, Zahs KR. Probing the biology of Alzheimer’s disease in mice. Neuron. 2010;66:631–645. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.04.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Morrissette DA, Parachikova A, Green KN, LaFerla FM. Relevance of transgenic mouse models to human Alzheimer disease. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:6033–6037. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R800030200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gotz J, Ittner LM. Animal models of Alzheimer’s disease and frontotemporal dementia. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2008;9:532–544. doi: 10.1038/nrn2420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Asuni AA, Boutajangout A, Quartermain D, Sigurdsson EM. Immunotherapy targeting pathological tau conformers in a tangle mouse model reduces brain pathology with associated functional improvements. J Neurosci. 2007;27:9115–9129. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2361-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Polydoro M, Acker CM, Duff K, Castillo PE, Davies P. Age-dependent impairment of cognitive and synaptic function in the htau mouse model of tau pathology. J Neurosci. 2009;29:10741–10749. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1065-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boutajangout A, Quartermain D, Sigurdsson EM. Immunotherapy targeting pathological tau prevents cognitive decline in a new tangle mouse model. J Neurosci. 2010;30:16559–16566. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4363-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hsiao K, Chapman P, Nilsen S, Eckman C, Harigaya Y, Younkin S, Yang F, Cole G. Correlative memory deficits, Aβ elevation, and amyloid plaques in transgenic mice. Science. 1996;274:99–102. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5284.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lewis J, McGowan E, Rockwood J, Melrose H, Nacharaju P, Van Slegtenhorst M, Gwinn-Hardy K, Paul MM, Baker M, Yu X, Duff K, Hardy J, Corral A, Lin WL, Yen SH, Dickson DW, Davies P, Hutton M. Neurofibrillary tangles, amyotrophy and progressive motor disturbance in mice expressing mutant (P301L) tau protein. Nat Genet. 2000;25:402–405. doi: 10.1038/78078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gimenez E, Montoliu L. A simple polymerase chain reaction assay for genotyping the retinal degeneration mutation (Pdeb(rd1)) in FVB/N-derived transgenic mice. Lab Anim. 2001;35:153–156. doi: 10.1258/0023677011911525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Asuni AA, Boutajangout A, Scholtzova H, Knudsen E, Li YS, Quartermain D, Frangione B, Wisniewski T, Sigurdsson EM. Vaccination of Alzheimer’s model mice with Aβ derivative in alum adjuvant reduces Aβ burden without microhemorrhages. Eur J Neurosci. 2006;24:2530–2542. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.05149.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boutajangout A, Ingadottir J, Davies P, Sigurdsson EM. Passive immunization targeting pathological phospho-tau protein in a mouse model reduces functional decline and clears tau aggregates from the brain. J Neurochem. 2011;118:658–667. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2011.07337.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Torres EM, Perry TA, Blockland A, Wilkinson LS, Wiley RG, Lappi DA, Dunnet SB. Behavioural, histochemical and biochemical consequences of selective immunolesions in discrete regions of the basal forebrain cholinergic system. Neuroscience. 1994;63:95–122. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(94)90010-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carter RJ, Lione LA, Humby T, Mangiarini L, Mahal A, Bates GP, Dunnett SB, Morton AJ. Characterization of progressive motor deficits in mice transgenic for the human Huntington’s disease mutation. J Neurosci. 1999;19:3248–3257. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-08-03248.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hyde LA, Crnic LS, Pollock A, Bickford PC. Motor learning in Ts65Dn mice, a model for Down syndrome. Dev Psychobiol. 2001;38:33–45. doi: 10.1002/1098-2302(2001)38:1<33::aid-dev3>3.0.co;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Davenport JW. Cretinism in rats: enduring behavioral deficit induced by tricyanoaminopropene. Science. 1970;167:1007–1008. doi: 10.1126/science.167.3920.1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hebb DO, Williams KA. A method of rating animal intelligence. J Gen Psychol. 1946;34:59–65. doi: 10.1080/00221309.1946.10544520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rabinovitch MS, Rosvold HE. A closed-field intelligence test for rats. Can J Psychol. 1951;5:122–128. doi: 10.1037/h0083542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]