Abstract

The traditional black-white color line in the American metropolis is being replaced by a more complex pattern of color lines involving multiple groups with different racial and ethnic origins. The consequences are positive in some respects, but they do not overcome the continuing barriers to equal opportunity. The degree of segregation has receded from the near-apartheid that was created in the black ghettos of Northern cities in the middle decades of the last century. Yet the experience of segregation continues to impact blacks of all economic classes. Today's color lines also involve Hispanics and Asians. The multiethnic metropolis is fostering a degree of neighborhood diversity that used to be quite rare. At the same time all-minority areas, now including blacks, Hispanics, and sometimes Asians, continue to be reproduced, and the disparities in community resources between white and minority neighborhoods remain deeply entrenched.

Not long after the Civil War, W.E.B. DuBois asserted that “The problem of the twentieth century is the problem of the color-line” (1903, p. 19), a perspective reinforced by Gunnar Myrdal's (1944) critique of the situation at mid-century. Since then many have looked for signs of progress, and certainly the situation is different today than it was generations ago. Social scientists mostly agree about the bare facts of residential segregation (see the review by Charles 2003). Based on a series of studies using mainly data from the 1970-1980 decade Massey and Denton (1993) concluded that African Americans faced a near-apartheid situation of persistent high segregation, barely responsive to improvements in black socioeconomic standing. Unlike Hispanic and Asian minorities, who experienced substantially lower levels of residential separation than did blacks, African Americans remained highly segregated even in metropolitan areas where they had relatively high income and education. Reductions in black-white segregation were found mainly in areas with small black populations (Massey and Gross 1991). Studying the subsequent decade (1980-1990), Farley and Frey (1994) found evidence for more widespread declines in segregation. Studies including data from 2000 and 2010 (Logan, Stults and Farley 2004; Logan and Stults 2011) show that black-white segregation continued to decline modestly at the national level, while Hispanic and Asian segregation was lower but showed no change during 1980-2010.

There are, however, differences of emphasis. As this essay will point out, segregation has many dimensions. The trends across these dimensions are often mixed, and scholars differ in which ones to highlight. For example one team of researchers has consistently emphasized that segregation of African Americans reached a peak in 1970, followed by a steady decline. Their initial report for the period through 1990 offered the caveats that the decline was more limited in large cities of the Northeast and Midwest and that “there are more completely black areas in our cities than there have ever been in the past, and large amounts of segregation linger” (Cutler, Glaeser and Vigdor 1999, p. 496). Their follow-up study for 2000 gave more emphasis to progress in its title “Promising News.” Yet it also included a critical proviso: “It is important to point out that the 2000 [national mean] index, while lower than the 1990 index, is still in the hypersegregated range” (Glaeser and Vigdor 2001, p. 5). Their recent update is more optimistically titled “The End of the Segregated Century,” and it refers in the executive summary to “the end of segregation” (Glaeser and Vigdor 2012). Yet the analysis makes clear that there has not been an end to segregation: “This shift does not mean that segregation has disappeared: […] The average African-American lives in a neighborhood where the share of population that is black exceeds the metropolitan average by roughly 30 percentage points” (2012, p. 4). In his essay in this issue, Vigdor (2013) acknowledges “the obvious persistence of intense segregation in many large cities,” but gives more emphasis to the decline in black-white segregation. His evaluation is evident in his rhetoric (the repeated observation that segregation is “really lower than any point in the past century”). It is also implicit in his discussion of the “persistence of racial inequality in the face of declining segregation.” Presumably segregation is now so low that if it had been an important mechanism in the perpetuation of racial income inequality we should have seen a significant reduction in inequality by now.

In this essay I review data from the same sources and explain why I interpret them as signs of incomplete and mixed progress in reducing racial barriers at the neighborhood level. I then comment briefly on Vigdor's hypotheses about the sources of change.

Sources and Methods

I rely on data from 1980 through 2010. The main source is the decennial census, but I use the five-year (2005-2009) pooled American Community Survey (ACS) for information on recent tract-level socioeconomic characteristics. There are significant measurement issues to deal with. For details of these issues and my approach to them see Logan and Stults (2011). I organize race/ethnic data into four main categories: Hispanic, non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, and non-Hispanic Asian/Pacific Islander. My analysis is based on metropolitan regions, defining areas consistently according to the metropolitan boundaries in the 2010 census. Because this is not a study of change at the tract level, it is not necessary to adjust for changes in tract boundaries (but see Logan, Xu, and Stults 2013 for a source of historical census data harmonized to 2010 boundaries). I use two standard measures to summarize residential patterns in metropolitan areas. The most intuitive is a class of Exposure Indices (P*) that refer to the characteristics of a tract where the average member of a given group lives. The other type of measure is the Index of Dissimilarity (D), which captures the degree to which two groups are evenly spread among census tracts in a given metropolis.

Recent Trends in Segregation in the U.S.

I begin with the levels and trends in segregation of blacks, Hispanics and Asians. I discuss the significance of the growth of the latter two groups for the emergence of more diverse neighborhoods in multiethnic metropolitan regions along with evidence that these coexist with traditional patterns of segregation and white flight in the same regions. Finally I move beyond the question of who lives where and ask about the kinds of neighborhoods where minorities live. My conclusion is that blacks and Hispanics have made little progress in living in more “equal” neighborhoods, even compared to whites or Asians with similar socioeconomic status. The mixed evidence about progress toward reducing segregation per se and this “separate and unequal” pattern lead me to give more weight to the persistence of group boundaries than to the indicators of improvement.

1. Trends in segregation

Table 1 presents values of D and exposure to non-Hispanic whites. These represent the level of segregation in the metropolitan region where the average minority group member lived, weighting areas with larger minority populations more heavily than areas with fewer minority residents.1

Table 1. Hispanic and Asian segregation, metropolitan averages for 1980-2010.

| 1980 | 1990 | 2000 | 2010 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||

| Blacks | ||||

| Dissimilarity from whites | 72.8 | 67.3 | 63.8 | 59.1 |

| Isolation | 61.0 | 54.8 | 50.6 | 45.2 |

| Exposure to whites | 31.2 | 34.3 | 34.0 | 34.8 |

| Hispanics | ||||

| Dissimilarity from whites | 50.3 | 50.0 | 50.8 | 48.5 |

| Isolation | 38.2 | 42.1 | 45.0 | 46.0 |

| Exposure to whites | 47.5 | 42.2 | 37.0 | 35.1 |

| Asians | ||||

| Dissimilarity from whites | 40.8 | 41.3 | 41.6 | 40.9 |

| Isolation | 17.4 | 18.2 | 20.7 | 22.4 |

| Exposure to whites | 61.7 | 58.2 | 52.3 | 48.9 |

Source: Logan and Stults (2011)

Black-white segregation reached a high of 79 in 1960 and 1970, and has been on the decline since then. The average D dropped 6 points in the 1980s, 3 points in the 1990s, and 5 points since 2000. By another measure, the average black exposure to whites, there has been no change in the last three decades. Black isolation has declined substantially, however, from 61.0 in 1980 to 45.2 in 2010, due largely to the growth of the Hispanic and Asian populations in tracts where blacks live. Changes have not been uniform across the country. As shown elsewhere (Logan and Stults 2011) reduction in the level of D during the 1980s and 1990s was greatest in the metropolitan areas with the smallest black populations. Black-white segregation has historically been lowest in metro areas with less than 5% black population, and it has declined the most since 1980 in these places (17 points on average). At the same time the persistence of very high black-white segregation in a few major Northeastern and Midwestern metropolitan areas is striking. These areas, home to about one in six African Americans, had extreme values of D, dropping only slightly since 1980. These areas could aptly be described as America's Ghetto Belt.

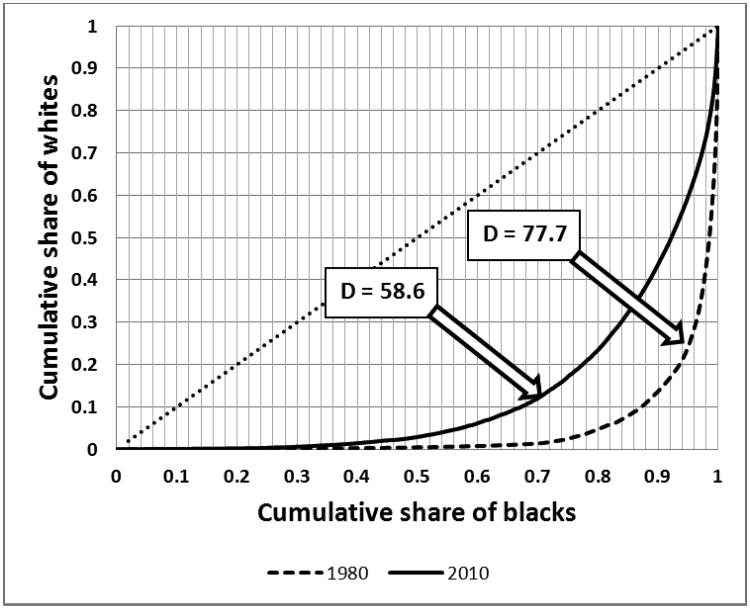

Outside the Ghetto Belt the current levels and trend are more positive. Yet the current average level of D is still very high. Figure 1 shows Lorenz curves that portray more fully the extent of residential separation in a metropolitan region where D is at about the national average of 59. This is the case of Kansas City, one of the nation's most segregated areas in 1980 (Gotham 2002). D has dropped from 77.7 in 1980 to 58.6 in 2010. If we list tracts in order from highest to lowest percent black, we can then plot the cumulative distribution of the total black population against the cumulative distribution of the total white population, from 0 to 100%. A perfectly even distribution would be represented as a straight line with a slope of 1, and in that case the value of D would be 0.

Figure 1. Lorenz curve for Kansas City metropolitan region, 1980 and 2010 showing census tract populations of blacks and whites.

In 1980 the curve was deflected very strongly toward the bottom right corner, and only a tiny share of the white population lived in the census tracts housing a large majority of the black population. Thirty years later the change is apparent but the difference in black and white locations is still stark. The 59 tracts with the highest black share house just 1% of the white population but 36.2% of the black population. These tracts are above 60% black. At the other extreme there are 48 tracts above 99% white, and these are the home of fully 11% of the region's white population. Despite the improvement, it is hard to conclude that this “average” metro is anywhere near the end of segregation.

Table 1 also shows that Hispanics are considerably less segregated from whites than are blacks (D is around 50), and Asian segregation is close to 10 points lower than that. These two groups are set apart in two other ways. First, their segregation from whites is unchanging. Second, as each group grows, it becomes more isolated (that is, group members are more likely to live in a residential enclave) and group members live in census tracts with much smaller shares of white neighbors. To some extent these patterns reflect the large share of Hispanics and Asians who are immigrants or second generation, with limited English proficiency and other measures of human capital that typically influence residential location. Yet although individuals experience spatial assimilation (see Massey 1985, Logan et al 1996) these indices demonstrate that collectively these groups are continuing to stand apart at the neighborhood level.

2. Global neighborhoods and white flight

These largely immigrant minority groups also have been shown to have an impact on black-white segregation. Farley and Frey (1994) suggested that because metropolitan areas with larger Hispanic and Asian populations were not traditional destinations for blacks, they may therefore have less intense racial barriers (see also White and Glick 1999, Iceland 2004). Logan and Zhang (2010, also Logan and Zhang 2011) have shown that these metro-level findings are linked to specific processes of neighborhood change. All-white neighborhoods are almost always first integrated by the entry of Hispanics and/or Asians, only then admitting blacks in substantial numbers.

The emergence of “global neighborhoods” in which all four of these groups are well represented represents a major shift toward shared urban space. In a sample of large multiethnic metropolitan areas, we found that less than a quarter of residents lived in these most diverse neighborhoods in 1980, a figure that jumped to over 40% by 2010. Half of Asians, 44% of whites, and about 35-36% of blacks and Hispanics lived in global neighborhoods in these regions in 2010 (Logan and Zhang 2011, pp. 4-5). Unfortunately the same analyses demonstrated that whites rarely enter all-minority neighborhoods, and they still have a tendency to leave diverse neighborhoods. Consequently in the areas we studied a large (though declining) share of minorities still live in neighborhoods with virtually no white residents. For example, 13% of blacks live in all-black neighborhoods and another 25% live in neighborhoods where blacks and Hispanics are the predominant populations (Logan and Zhang 2011, pp. 4-5).

3. Separate and unequal

A final consideration is the degree to which minorities have access to neighborhoods of similar character to those where comparable whites live. From the perspective of place stratification that now plays a central role in urban research (Logan 1978, Sampson 2012), segregation is important especially because it tends to restrict access to place-based resources. For this reason it is important to assess trends in access to such resources.

A key indicator is the share of neighbors whose incomes are below the poverty line. Table 2 reports the poverty levels of the neighborhoods in which the average group member lived in metropolitan areas in 1990, 2000 and 2005-2009.2 The values in this table are exposure scores, comparable to the P* exposure measures used in traditional segregation studies. Because the socioeconomic composition of the neighborhood is closely linked to one's own income, the table calculates exposure scores separately for households in different income categories.3

Table 2. Average neighborhood poverty by race/ethnicity and household income in metropolitan regions.

| Mean values for group | Ratio to white mean: same income category | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1990 | 2000 | 2005-2009 | 1990 | 2000 | 2005-2009 | |

|

|

||||||

| Non-Hispanic white total | 9.9 | 9.4 | 10.7 | |||

| Poor | 12.4 | 11.6 | 12.9 | |||

| Middle | 9.9 | 9.6 | 10.9 | |||

| Affluent | 7.8 | 7.7 | 8.9 | |||

| Non-Hispanic black total | 21.4 | 18.9 | 19.0 | 2.2 | 2.0 | 1.8 |

| Poor | 24.8 | 21.9 | 21.8 | 2.0 | 1.9 | 1.7 |

| Middle | 18.8 | 17.3 | 17.3 | 1.9 | 1.8 | 1.6 |

| Affluent | 15.4 | 14.3 | 13.9 | 2.0 | 1.9 | 1.6 |

| Hispanic total | 18.9 | 17.8 | 17.3 | 1.9 | 1.9 | 1.6 |

| Poor | 22.6 | 20.9 | 19.9 | 1.8 | 1.8 | 1.5 |

| Middle | 17.3 | 16.8 | 16.2 | 1.7 | 1.8 | 1.5 |

| Affluent | 13.3 | 13.5 | 13.0 | 1.7 | 1.8 | 1.5 |

| Asian total | 11.7 | 11.7 | 11.3 | 1.2 | 1.2 | 1.1 |

| Poor | 16.3 | 16.3 | 15.2 | 1.3 | 1.4 | 1.2 |

| Middle | 11.7 | 11.9 | 11.6 | 1.2 | 1.2 | 1.1 |

| Affluent | 8.3 | 8.7 | 8.7 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 1.0 |

In every year both whites' and Asians' exposure to neighborhood poverty was considerably less than that of blacks and Hispanics. This finding is expected given the latter groups' lower earnings. More important are the income-specific findings, which belie the common expectation that inequalities in neighborhood outcomes are mainly due to class differences. Focusing on the 2005-2009 values, notice that the average “affluent” black household lived in a neighborhood that was 13.9% poor; the value for affluent Hispanics was 13.0%. But “poor” white households' neighborhoods were only 12.9% poor. Within each racial/ethnic group neighborhood poverty is negatively associated with one's own household income. Yet race itself, controlling for household income, is a very strong predictor of neighborhood resources.

The last three columns of Table 2 show the ratio between the poverty share in the average minority group member's neighborhood and the poverty share in the neighborhood of the average white in the same category of household income. Values for blacks and Hispanics are mainly in the range from 1.5:1 to 2.0:1. Affluent group members have about the same level of disadvantage in relation to comparable whites as do poor group members. Over the last two decades there has been some narrowing of the gap. Still the main pattern resists change. It appears that whites of all income levels have access to relatively low-poverty neighborhoods; the most affluent blacks and Hispanics fall somewhat behind while their less advantaged co-ethnics live in areas of much higher poverty.

Causes of these Trends

Researchers have devoted considerable effort to determining the sources of variations in segregation and causes of trends. Vigdor presents several hypotheses but offers no evidence to support them. His overarching hypothesis is that the downward trend in black-white segregation was caused by shifts in government policy, and specifically passage of the Fair Housing Act in 1968 and other civil rights reforms in that period. As much as one would hope to see such an impact, this seems unlikely given that there have been such weak efforts to enforce federal legislation. He offers two other hypotheses: 1) segregation declined as a result of shifts in the regional distribution of the black population away from the Ghetto Belt, and 2) black suburbanization hollowed out the central city ghettos that sustain high levels of segregation.

In fact the evidence suggests that inter-regional shifts had very little effect. A simple way to test the hypothesis is to imagine that the level of segregation had been the same in 1980 as it was in 2010 in every metropolitan area. The result of population shifts could be calculated by weighting these constant values of D according to the number of black residents in each decade. The result is as follows: the weighted average D would have been 62.3 in 1980 (actual 72.8), 61.0 in 1990 (actual 67.3), and 60.3 in 2000 (actual 63.8), reaching the observed value of 59.1 in 2010. Regional shifts alone would result in miniscule decline in segregation. Clearly the driving force for change was the reduction in segregation in the average metropolis.

It would be more difficult to test the impact of black suburbanization. It is not sufficient to note that suburban segregation is typically lower than segregation in central cities. The other factor to consider is whether blacks tended to concentrate in a few suburban areas or to disperse. In the case of Kansas City there was in fact a very substantial population decline in the nearly all-black neighborhoods of downtown Kansas City, MO (El Nasser 2011). These areas typically remained above 90% black in 2010 but lost population as growing numbers of residents sought other opportunities in the region. Black suburbanization took two forms. Some Missouri suburbs are becoming disproportionately black and their growth results in increasing segregation. But the main trend has been for many suburbs on the Kansas side to change modestly from 0-10% to 5-15% black. This dispersion of suburban blacks was facilitated by a very heterogeneous housing market, including smaller pre-World War II single family homes, both older and new apartment complexes at various price levels, and a wide range of new single-family development. Such conditions cannot be taken for granted.

Conclusion

The findings reported here could be construed as grounds for optimism. Black-white segregation is not as intense as it once was. Growing multi-ethnic metropolitan regions are creating conditions that facilitate black entry into “global neighborhoods” without triggering the nearly automatic white flight that was typical in the past. Yet my own overall evaluation is tempered by several disappointing facts. The decline in black-white segregation is painfully slow, and at the current rate it will be another two decades before it reaches even the level of Hispanic segregation today. There remains a Ghetto Belt of major metropolitan regions where segregation is still quite intense, and the current average level of segregation still represents a sharp separation by race. Whites rarely enter predominantly minority neighborhoods but they continue to leave mixed areas, suggesting that there may be a limit to progress in the multi-ethnic metropolis. And finally even the most affluent black and Hispanic households still live in neighborhoods with fewer community resources than much less affluent whites. We are far from the point when we could assess how the end of segregation might affect other dimensions of racial inequality.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant from the Russell Sage Foundation for the US2010 Project: Discover America in a New Century and by Brown University's initiative in Spatial Structures in the Social Sciences.

Footnotes

These results were previously reported by Logan and Stults (2011). Data for 1980-2010 for cities and metropolitan regions are provided on-line: http://www.s4.brown.edu/us2010/segregation2010/Default.aspx.

These results are discussed in more detail in Logan (2011). Typically researchers use characteristics of the census tract where people live as a measure of their “neighborhood.” In this report we use a larger area: the census tract plus each adjacent tract. Because socioeconomic data are based on samples (and the 2005-2009 ACS sample is relatively small) it is helpful to take advantage of information on adjacent tracts to improve the reliability of estimates.

The income categories are “poor” (income below 175 percent of the poverty line for a family of four, “affluent” (income more than 350 percent of the poverty line,), and “middle income” (those falling in between). The choices of cutting points were constrained by the categories tabulated by the Census Bureau. “Poor” is under $22,500 in 1990, $30,000 in 2000, and $40,000 in 2005-2009. “Affluent” is over $45,000 in 1990, $60,000 in 2000, and $75,000 in 2005-2009. Exposure measures for poverty, median and per capita income, percent of residents with a college education or professional occupation, home ownership, and housing vacancy in 1990, 2000, and 2005-2009 for metropolitan regions and counties are provided on-line: http://www.s4.brown.edu/us2010/SUC/default.aspx.

References

- Charles Camille Zubrinsky. The Dynamics of Racial Residential Segregation. Annual Review of Sociology. 2003;29:167–207. [Google Scholar]

- Cutler David M, Glaeser Edward L, Vigdor Jacob L. The Rise and Decline of the American Ghetto. The Journal of Political Economy. 1999;107:455–506. [Google Scholar]

- Du Bois WEB. The Souls of Black Folk. New York: New American Library, Inc; 1903. [Google Scholar]

- El Nasser Haya. Cities Moving Beyond Segregation. USA Today. 2011 Dec 7; downloaded 12/16/12 from http://usatoday30.usatoday.com/news/nation/story/2011-12-06/segregation-kansas-city/51694850/1.

- Farley Reynolds, Frey William H. Changes in the segregation of whites from blacks during the 1980s: Small steps towards a more integrated society. American Sociological Review. 1994;59:23–45. [Google Scholar]

- Glaeser Edward, Vigdor Jacob. Racial Segregation in the 2000 Census: Promising News. Washington, DC: The Brookings Institution; 2001. Downloaded 12/16/12 from http://www.brookings.edu/es/urban/census/glaeser.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Glaeser Edward, Vigdor Jacob. The End of the Segregated Century: Racial Separation in America's Neighborhoods, 1890-2010. Manhattan Institute Civic Report #66. 2012 Downloaded 12/16/12 from http://www.manhattan-institute.org/html/cr_66.htm.

- Gotham Kevin Fox. Race, Real Estate, and Uneven Development: The Kansas City Experience, 1900-2000. Albany: SUNY Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Iceland John. Beyond Black and White: Residential Segregation in Multiethnic America. Social Science Research. 2004;33:248–271. [Google Scholar]

- Logan John R. Growth, Politics, and the Stratification of Places. American Journal of Sociology. 1978;84:404–416. [Google Scholar]

- Logan John R. Separate and Unequal: The Neighborhood Gap for Blacks, Hispanics and Asians in Metropolitan America. US2010 Project Report. 2011 downloaded 12/16/12 from http://www.s4.brown.edu/us2010/Data/Report/report0727.pdf.

- Logan John R, Alba Richard D, McNulty Tom, Fisher Brian. Making a Place in the Metropolis: Locational Attainment in Cities and Suburbs. Demography. 1996;33:443–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logan John R, Stults Brian J. The Persistence of Segregation in the Metropolis: New Findings from the 2010 Census. US2010 Project Report. 2011 downloaded 12/16/12 from http://www.s4.brown.edu/us2010/Data/Report/report2.pdf.

- Logan John R, Stults Brian J, Farley Reynolds. Segregation of Minorities in the Metropolis: Two Decades of Change. Demography. 2004;41:1–22. doi: 10.1353/dem.2004.0007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logan John R, Zhang Charles. Global Neighborhoods: New Pathways to Diversity and Separation. American Journal of Sociology. 2010;115:1069–1109. doi: 10.1086/649498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logan John R, Zhang Charles. Global Neighborhoods: New Evidence from Census 2010. US2010 Project Report. 2011 downloaded 12/16/12 from http://www.s4.brown.edu/us2010/Data/Report/globalfinal2.pdf.

- Massey Douglas S. Ethnic Residential Segregation: A Theoretical Synthesis and Empirical Review. Sociology and Social Science Research. 1985;69:315–350. [Google Scholar]

- Massey Douglas S, Denton Nancy A. American Apartheid: Segregation and the Making of the Underclass. Cambridge: Harvard University Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Massey Douglas S, Gross Andrew B. Explaining Trends in Racial Segregation, 1970-1980. Urban Affairs Quarterly. 1991;27:13–35. [Google Scholar]

- Myrdal Gunnar. An American Dilemma: The Negro Problem and Modern Democracy. New York: Harper & Bros; 1944. [Google Scholar]

- Sampson Robert J. Great American City: Chicago and the Enduring Neighborhood Effect. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- White Michael J, Glick Jennifer E. The Impact of Immigration on Residential Segregation. In: Bean Frank D, Bell-Rose Stephanie., editors. Immigration and Opportunity: Race, Ethnicity and Employment in the United States. New York: Russell Sage Foundation; 1999. pp. 345–372. [Google Scholar]