Abstract

Background

Sublobar resection for non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) remains controversial owing to concern about local recurrence and long-term survival outcomes. We sought to determine the efficacy of wedge resection as an oncological procedure.

Methods

We analyzed the outcomes of all patients with NSCLC undergoing surgical resection at the Cancer Centre of Southeastern Ontario between 1998 and 2009. The standard of care for patients with adequate cardiopulmonary reserve was lobectomy. Wedge resection was performed for patients with inadequate reserve to tolerate lobectomy. Predictors of recurrence and survival were assessed. Appropriate statistical analyses involved the χ2 test, an independent samples t test and Kaplan–Meier estimates of survival. Outcomes were stratified for tumour size and American Joint Committee on Cancer seventh edition TNM stage for non–small cell lung cancer.

Results

A total of 423 patients underwent surgical resection during our study period: wedge resection in 71 patients and lobectomy in 352. The mean age of patients was 64 years. Mean follow-up for cancer survivors was 39 months. There was no significant difference between wedge resection and lobectomy for rate of tumour recurrence, mortality or disease-free survival in patients with stage IA tumours less than 2 cm in diameter.

Conclusion

Wedge resection with lymph node sampling is an adequate oncological procedure for non–small cell lung cancer in properly selected patients, specifically, those with stage IA tumours less than 2 cm in diameter.

Abstract

Contexte

La résection sous-lobaire pour le cancer du poumon non à petites cellules (CPNPC) demeure controversée en raison du risque de récurrence locale et des perspectives de survie à long terme. Nous avons voulu déterminer l’efficacité de la résection cunéiforme en tant qu’intervention oncologique.

Méthodes

Nous avons analysé les résultats pour tous les patients atteints d’un CPNPC soumis à une résection chirurgicale au Centre oncologique du Sud-Est de l’Ontario entre 1998 et 2009. Chez les patients qui présentaient une réserve cardiopulmonaire suffisante, la norme thérapeutique était la lobectomie. Les patients dont la réserve était insuffisante pour tolérer une lobectomie ont subi une résection cunéiforme. Les prédicteurs de récurrences et de survie ont été évalués. Les analyses statistiques appropriées ont inclus le test χ2, le test t et les estimations de Kaplan–Meier de la survie. Les résultats ont été stratifiés en fonction de la taille et du stade de la tumeur selon la septième édition de la classification TNM de l’American Joint Committee on Cancer pour le CPNPC.

Résultats

En tout, 423 patients ont subi une résection chirurgicale au cours de la période couverte par notre étude : résection cunéiforme chez 71 patients et lobectomie chez 352 patients. L’âge moyen des patients était de 64 ans. Le suivi moyen pour les survivants du cancer a été de 39 mois. On n’a noté aucune différence significative entre la résection cunéiforme et la lobectomie aux plans des récurrences tumorales, de la mortalité ou de la survie sans maladie chez les patients qui présentaient des tumeurs de stade IA de moins de 2 cm de diamètre.

Conclusion

La résection cunéiforme avec exérèse des ganglions lymphatiques est une intervention oncologique appropriée pour le CPNPC chez les patients adéquatement sélectionnés, plus précisément, chez ceux qui ont des tumeurs de stade IA de moins de 2 cm de diamètre.

Surgical resection in the form of lobectomy or pneumonectomy remains the standard of care for stage I and II non–small cell lung carcinoma (NSCLC) despite advances in chemotherapy and radiation therapy.1 Owing to the primary causative relationship of smoking to NSCLC and associated cardiopulmonary comorbidities, many patients are deemed medically unfit to withstand full lobectomy. The best management for these patients remains controversial; many modalities are available, necessitating further investigation on this topic.2 These modalities include sublobar resection (wedge resection or anatomic segmental resection), observation, conventional fractionated or stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT) and radiofrequency ablation.3–7 Many surgeons still prefer sublobar resections over SBRT and ablative therapies despite successful local control rates having been reported with SBRT, particularly by Timmerman and colleagues.8 Controversy remains as to whether sublobar resections are adequate oncologic procedures for patients with severely impaired pulmonary function who could not withstand lobectomy.2,9 This relates to concern that despite preservation of pulmonary function, tumour resection margins may be compromised with inadequate nodal sampling, possibly understaging the primary tumour.10 This could lead to increased rates of local and systemic recurrence and decrease disease-free and overall survival.11

All but 1 previous study examining sublobar resections for NSCLC have been retrospective in nature, many revealing conflicting results.12–32 The prospective trial by Ginsberg and Rubinstein13 concluded that lobectomy was preferred over limited resections owing to decreased rates of local recurrence. This landmark study did not account for tumour diameter or location of the early-stage lesions. It has since been postulated that sublobar resection is an adequate oncologic surgery for peripheral lesions less than 2 cm in diameter, especially in the setting of a second primary lung cancer, adenocarcinoma in situ, or ground-glass opacities.29,33–40 All previous studies have used the sixth edition American Joint Committee in Cancer (AJCC) tumour-node-metastasis (TNM) classification and focused on comparing outcomes of segmental resection to lobectomy.41 Only 1 previous non-Canadian study has focused on comparing outcomes of wedge resection to lobectomy; however, this study also used the sixth edition AJCC TNM classification.31 The purpose of the present study was to determine whether there is a significant difference in tumour recurrence and survival in patients who undergo wedge resections versus lobectomy for NSCLC based on the seventh edition AJCC TNM classification and thus to determine whether wedge resection is an adequate oncologic procedure to offer patients.42–46

Methods

This was a retrospective analysis of all patients who underwent lung resection for NSCLC at the Cancer Centre of Southeastern Ontario for the fiscal years 1998 to 2009. All patients were pathologically staged according to the seventh edition AJCC TNM classification. Lobectomy or pneumonectomy was the standard of care performed for patients with adequate pulmonary function. Sublobar resection was reserved for patients with cardiopulmonary comorbidities precluding lobectomy. We compared the outcomes of patients who underwent either of these 2 procedures during the study period. This study received research ethics board approval from the research ethics board at Queen’s University in Kingston, Ont.

We collected data on basic demographics (age, sex), patient comorbidities (coronary artery disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [COPD], diabetes), operative details (type of surgery, anatomic location), tumour pathological characteristics (margin status, histology, differentiation, presence of lymphatic or vascular invasion), disease recurrence, mortality (including cause of death) and morbidity (prolonged air leak, cardiac arrhythmia).

Primary outcomes included incidence of local–regional and distant recurrence, disease-free survival and overall survival. Disease recurrence was defined as the incidence of recurrent carcinoma (local–regional or distant), disease-free survival was the time from surgery to diagnosis of recurrent carcinoma, and overall survival was the time from surgery to death or last known follow-up. Secondary outcomes included length of hospital stay and postoperative complications, including prolonged air leak and cardiac arrhythmia. Prolonged air leak was defined as an air leak from the chest tube lasting more than 5 days. Cardiac arrhythmia was defined as an acute change in the patients’ electrocardiogram to display atrial fibrillation, atrial flutter or multifocal atrial tachycardia (MAT).

Statistical analysis

Data were entered in Excel and imported into PASW Statistics (SPSS Inc.) for analysis. Following a descriptive analysis (means, standard deviations and medians for continuous data, frequencies for categorical data), continuous data were plotted to assess the normality of the distribution. We used χ2 tests (Pearson or Fisher exact, as appropriate) to compare the lobectomy and wedge groups on categorical data, such as sex, comorbidities and complications. We performed independent samples t tests to compare the groups on age and tumour diameter and the nonparametric Mann–Whitney U test to compare the groups on length of stay in hospital. We used Kaplan–Meier analysis to compare the groups on time to recurrence. We also performed subset analyses for cancer stage, tumour stage and smoking status.

Results

A total of 352 patients underwent lobectomy and 71 patients underwent wedge resection. Clinical outcomes were balanced between the cohorts for age, sex, smoking, neoadjuvant and adjuvant chemoradiotherapy (Table 1). The mean time to recurrence was 22 months in patients who underwent lobectomy and 21 months in those who underwent wedge resection; mean follow-up after surgery was 39 months and 37 months, respectively, and mean follow-up after recurrence was 14 months and 13 months, respectively. The mean age of patients was 64.7 (range 28–82) years. Most patients were smokers (388, 91.7%). Patient who underwent wedge resections were more likely to have COPD by spirometry than those who underwent lobectomy (46.5% v. 28.9%, p = 0.004). The groups were balanced with respect to the presence of other significant comorbidities, such as coronary artery disease, diabetes and substance abuse (Table 1).

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of patients undergoing surgical resection for non–small cell lung cancer, by surgical procedure

| Characteristic | Group; no (%)* | p value† | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lobectomy n = 352 |

Wedge resection n = 71 |

||

| Age mean, yr | 64.7 | 64.9 | 0.78 |

| Sex | 0.48 | ||

| Male | 165 (46.9) | 30 (42.3) | |

| Female | 187 (53.1) | 41 (57.7) | |

| Smoker | 323 (96.1) | 65 (98.5) | 0.48 |

| Comorbidities | |||

| Coronary artery disease | 87 (24.9) | 19 (26.8) | 0.74 |

| COPD | 101 (28.9) | 33 (46.5) | 0.004 |

| Psychiatric | 33 (9.4) | 6 (8.4) | 0.80 |

| Type II diabetes | 34 (9.7) | 6 (8.5) | 0.74 |

| Chemotherapy | |||

| Adjuvant | 57 (16.9) | 10 (14.9) | 0.70 |

| Neoadjuvant | 7 (2.1) | 1 (1.5) | > 0.99 |

| Tumour stage | 0.007 | ||

| T1a | 96 (27.3) | 27 (38.0) | |

| T1b | 86 (24.4) | 16 (22.5) | |

| T2a | 117 (33.2) | 18 (25.4) | |

| T2b | 23 (6.5) | 2 (2.8) | |

| T3 | 28 (8.0) | 4 (5.6) | |

| T4 | 2 (0.6) | 4 (5.6) | |

| Cancer stage; AJCC seventh ed. | 0.020 | ||

| IA | 146 (41.5) | 35 (49.3) | |

| IB | 68 (19.3) | 16 (22.5) | |

| IIA | 81 (23.0) | 4 (5.6) | |

| IIB | 29 (8.2) | 5 (7.0) | |

| IIIA | 26 (7.4) | 11 (15.5) | |

| IIIB | 1 (0.3) | 0 | |

| IV | 1 (0.3) | 0 | |

AJCC = American Joint Committee in Cancer; COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Unless otherwise indicated.

All tests are χ2 tests (Pearson or Fisher exact, as appropriate) with the exception of age, which was based on a t test.

With respect to pathological outcomes, distribution of tumour histology, margin status, differentiation and presence of lymphatic or vascular invasion were also balanced between cohorts (Table 2). Patients who underwent wedge resection were more likely than those who underwent lobectomy to have a smaller tumour diameter (p < 0.001) and to have a tumour less than 2 cm in size (p = 0.009). They also tended to have stage IA disease (p = 0.021).

Table 2.

Pathological characteristics of patients undergoing surgical resection for non–small cell lung cancer, by surgical procedure

| Characteristic | Group; no (%)* | p value† | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lobectomy n = 351 |

Wedge resection n = 71 |

||

| Tumour size, mean, cm | 3.3 | 2.5 | 0.002 |

| T1a; AJCC seventh ed. | 96 (27.3) | 27 (38) | 0.007 |

| Stage IA; AJCC seventh ed. | 146 (41.5) | 35 (49.3) | 0.021 |

| Histology, no (%) | 0.44 | ||

| Adenocarcinoma | 230 (65.5) | 53 (74.6) | |

| Squamous cell | 94 (26.7) | 15 (21.1) | |

| Adenosquamous | 9 (2.6) | 0 | |

| Large cell | 12 (3.4) | 3 (4.2) | |

| Other | 5 (1.4) | 0 | |

| Tumour differentiation | 0.38 | ||

| Well | 46 (13.3) | 11 (16.2) | |

| Moderate | 134 (38.7) | 19 (27.9) | |

| Poor | 154 (44.5) | 36 (52.9) | |

| Undifferentiated | 12 (3.5) | 2 (2.9) | |

| Invasion present | |||

| Lymphatic | 87 (25.3) | 21 (30.4) | 0.38 |

| Vascular | 101 (29.4) | 18 (26.5) | 0.63 |

AJCC = American Joint Committee in Cancer.

Unless otherwise indicated.

All tests are χ2 other than tumour size, which was assessed using a t test.

Table 3 shows the disease-free survival and overall survival, by tumour stage and by cancer stage, for patients in the lobectomy and wedge resection groups. Between-group differences in disease-free survival existed for both tumour stage and cancer stage (p = 0.043 and p = 0.008, respectively), but between-group differences in overall survival fell short of significance (p = 0.08 and p = 0.09, respectively).

Table 3.

Tumour and cancer stage–specific disease-free survival and overall survival rates

| Stage* | Group; no. (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Disease-free survival | Overall survival | |||||

|

|

|

|||||

| Lobectomy, n = 223 | Wedge resection, n = 43 | p value† | Lobectomy, n = 223 | Wedge resection, n = 42 | p value† | |

| Tumour stage | 0.043 | 0.081 | ||||

|

| ||||||

| T1a | 67 (30.0) | 18 (41.9) | 71 (30.5) | 22 (52.4) | ||

|

| ||||||

| T1b | 58 (26.0) | 9 (20.9) | 57 (24.5) | 9 (21.4) | ||

|

| ||||||

| T2a | 67 (30.0) | 11 (25.6) | 73 (31.3) | 8 (19.0) | ||

|

| ||||||

| T2b | 15 (6.8) | 1 (2.3) | 12 (5.1) | 1 (2.4) | ||

|

| ||||||

| T3 | 14 (6.3) | 1 (2.3) | 18 (7.7) | 1 (2.4) | ||

|

| ||||||

| T4 | 2 (0.9) | 3 (7.0) | 2 (0.9) | 1 (2.4) | ||

|

| ||||||

| Cancer stage | 0.008 | 0.088 | ||||

|

| ||||||

| IA | 110 (49.3) | 107 (45.9) | 23 (53.5) | 26 (61.9) | ||

|

| ||||||

| IB | 43 (19.2) | 45 (19.3) | 9 (20.9) | 7 (16.6) | ||

|

| ||||||

| IIA | 39 (17.5) | 46 (19.8) | 1 (2.3) | 2 (4.8) | ||

|

| ||||||

| IIB | 19 (8.5) | 22 (9.5) | 2 (4.7) | 2 (4.8) | ||

|

| ||||||

| IIIA | 10 (4.5) | 11 (4.7) | 8 (18.6) | 5 (11.9) | ||

|

| ||||||

| IIIB | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.4) | 0 | 0 | ||

|

| ||||||

| IV | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.4) | 0 | 0 | ||

AJCC = American Joint Committee on Cancer.

Tumour stage and cancer stage are based on the AJCC, seventh edition.

p values are based on the Pearson χ2 test.

In comparing surgical outcomes between the 2 cohorts there was a trend that patients who underwent lobectomy had a longer stay in hospital than those who underwent wedge resection (7.7 d v. 6.8 d, p = 0.09), although the median values (6 d) were the same. There was no significant difference in 30-day mortality (4 deaths in the lobectomy group v. 2 in the wedge resection group). There were higher rates of prolonged air leak in the lobectomy group than the wedge resection group (12.5% v. 7%, p = 0.19), but the sample was too small to reach statistical significance. Similarly there were higher rates of atrial fibrillation, flutter and MAT in the lobectomy group than the wedge resection group (6% v. 1.4%); however, this difference did not attain statistical significance.

For disease-free survival there was no significant difference between wedge resection and lobectomy (p = 0.59). There was also no difference in overall tumour recurrence (36.8% v. 35%, respectively, p = 0.78) or in overall mortality (37.3% v. 32.7%, respectively, p = 0.46).

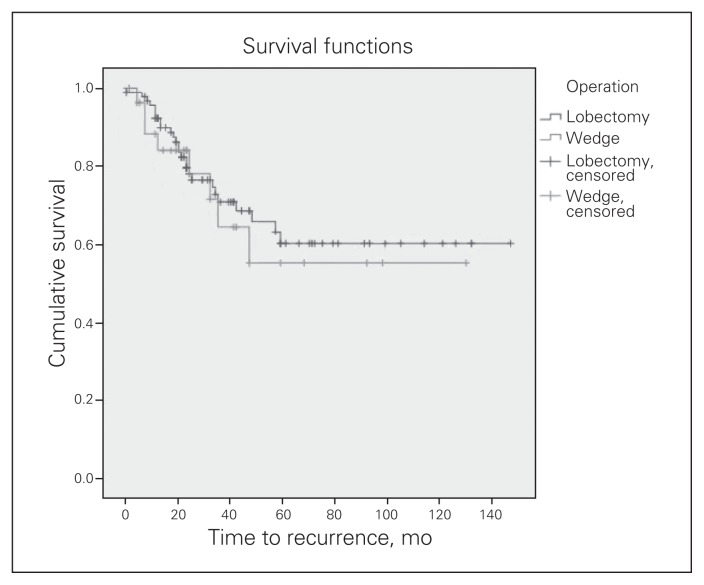

When the cohorts were stratified by tumour size, there was no significant difference in disease-free survival for patients with tumours less than 2 cm in diameter (p = 0.65; Fig. 1). There was, however, a significant difference in disease-free survival in favour of lobectomy for patients with tumours larger than 5 cm in diameter (p = 0.001). For patients with tumours less than 2 cm, the hospital stay was significantly longer for those who underwent lobectomy than those who underwent wedge resection (7.9 d v. 6.2 d, p = 0.043), which was also reflected in the median values (6 d and 5 d, respectively). We observed a trend toward higher rates of prolonged air leak in the lobectomy group compared with the wedge resection group (18.9% v. 6.1%, respectively, p = 0.10). There was no significant difference between the lobectomy and wedge resection cohorts for patients with tumours smaller than 2 cm for recurrence (27.7% v. 26.7%, respectively, p = 0.92) or overall mortality (25% v. 19.4%, respectively, p = 0.52; Table 4). When tumours were stratified based on the seventh edition AJCC TNM classification, there were no significant differences in outcomes encountered for tumour stage and overall stage IA and IB disease.

Fig. 1.

Kaplan–Meier estimates of disease-free survival in patients who underwent lobectomy compared with those who underwent wedge resection for tumours smaller than 2 cm in diameter (p = 0.65).

Table 4.

Outcomes for patients with tumours smaller than 2 cm in diameter

| Outcome | Group; no. (%)* | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lobectomy, n = 96 | Wedge resection, n = 33 | ||

| Tumour recurrence | 26 (27.7) | 8 (26.7) | 0.92† |

| Distant; brain, bone, adrenal | 11 | 2 | |

| Regional; mediastinal or hilar lymph nodes | 6 | 3 | |

| Local; within lung parenchyma | 9 | 3 | |

| Overall mortality | 24 (25) | 6 (19.4) | 0.52† |

| Complication; prolonged air leak | 18 (18.9) | 2 (6.1) | 0.10† |

| Length of hospital stay, mean d | 7.9 | 6.2 | 0.043‡ |

| Tumour diameter, mean cm | 1.6 | 1.5 | 0.13‡ |

Unless otherwise indicated.

χ2 test.

Mann–Whitney U test.

Discussion

This Canadian study carried out at a tertiary care university hospital is unique in that it predominantly compares wedge resection (as opposed to segmental resection) with lobectomy for the surgical management of NSCLC. In addition, the groups were stratified by tumour size and based on the seventh edition AJCC TNM classification. We observed similar rates of disease-free and overall survival for patients with early-stage NSCLC undergoing lobectomy and wedge resection.

Limitations

The limitations of this study arise primarily from its retrospective nature and 11-year duration. Some patient data on preoperative cardiopulmonary assessment (pulmonary function and echocardiography test results) were simply not available. However, given our institution’s adherence to widely accepted guidelines (Cancer Care Ontario, American College of Chest Physicians and National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines) for the conduct of preoperative assessment and pulmonary resection, along with the demographic and comorbidity data provided, readers are still able to extrapolate the applicability of these results to their own patients. In addition, during the 11-year course of this study, practice standards regarding lymph node assessment and adjuvant therapy protocols changed. We strongly feel that this would not have affected the results substantially, given that only those patients with the smallest tumours (≤ 2 cm) who underwent wedge resection had similar survival to those who underwent lobectomy. These patients would have been unlikely to receive chemotherapy, even with the new standard of care.

It is important to recognize that patients with compromised pulmonary reserve may be more likely to die sooner than those without compromised pulmonary reserve of causes other than lung cancer recurrence, thus potentially decreasing overall survival and artificially inflating the disease-free survival in this group. Furthermore, patients who underwent wedge resection were more likely to have documented COPD than those who underwent lobectomy. In addition, the wedge resection cohort was selected to have smaller (< 2 cm), earlier staged tumours (stage IA or IB) than the lobectomy cohort. For tumours smaller than 2 cm in size, patients who underwent lobectomy had a significantly increased length of hospital stay. This may be due to the complication of prolonged air leak, for which we observed a trend toward higher rates.

Conclusion

These data demonstrate that in properly selected patients wedge resection for NSCLC has the potential to be an adequate oncologic procedure. Specifically, the eligible patient groups include those with small tumours (< 2 cm in diameter) and seventh edition AJCC stage IA or IB disease. This is supported by similar rates of disease-free and overall survival observed in these cohorts. Furthermore, we await the results of the ongoing National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group phase III randomized trial of lobectomy versus sublobar resection for tumours smaller than 2 cm in patients with peripheral NSCLC (BRC.5 CALGB 140503) to learn whether similar survival outcomes to those in our retrospective analysis can be observed in the prospective setting.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

Contributors: A. McGuire designed the study and acquired the data, which all authors analyzed. A. McGuire and W. Hopman wrote the article, which all authors reviewed and approved for publication.

References

- 1.National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) Non-small cell lung cancer. 2010. Practice Guidelines in Oncology. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Forquer JA, Fakiris AJ, McGarry RC, et al. Treatment options for stage I non-small-cell lung carcinoma patients not suitable for lobectomy. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2009;9:1443–53. doi: 10.1586/era.09.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shennib H, Bogart J, Herndon JE, II, et al. Video-assisted wedge resection and local radiotherapy for peripheral lung cancer in high-risk patients: the cancer and leukemia group b (CALGB) 9335, a phase II, multi-institutional cooperative group study. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2005;129:813–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2004.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kaneda M, Watanabe F, Tarukawa T, et al. Limited operation for lung cancer in combination with postoperative radiation therapy. Ann Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2007;13:15–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Voynov G, Heron DE, Lin CJ, et al. Intraoperative 125I Vicryl mesh brachytherapy after sublobar resection for high-risk stage I non-small cell lung cancer. Brachytherapy. 2005;4:278–85. doi: 10.1016/j.brachy.2005.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Birdas TJ, Koehler RP, Colonias A, et al. Sublobar resection with brachytherapy versus lobectomy for stage Ib non-small cell lung cancer. Ann Thorac Surg. 2006;81:434–439. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2005.08.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fukuse T, Ogawa E, Chen F, et al. Limited surgery and radiofrequency ablation for recurrent lung cancer. Ann Thorac Surg. 2006;82:1506–8. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2005.12.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Timmerman R, Paulus R, Galvin J, et al. RTOG 0236: Stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT) to treat medically inoperable early stage lung cancer patients. Proceedings of the American Society for Therapeutic Radiology and Oncology (ASTRO) Annual Meeting; Chicago, IL. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2009;75(suppl):S3. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sienel W, Dango S, Kirschbaum A, et al. Sublobar resections in stage IA non-small cell lung cancer: segmentectomies result in significantly better cancer related survival than wedge resections. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2008;33:728–34. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2007.12.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.El-Sherif A, Fernando HC, Santos R, et al. Margin and local recurrence after sublobar resection for non-small cell lung cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14:2400–5. doi: 10.1245/s10434-007-9421-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sienel W, Stremmel C, Kirschbaum A, et al. Frequency of local recurrence following segmentectomy of stage IA non-small cell lung cancer is influenced by segment localization and width of resection margins —implications for patient selection for segmentectomy. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2007;31:522–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2006.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.El-Sherif A, Gooding WE, Santos R, et al. Outcomes of sublobar resection versus lobectomy for stage I non-small cell lung cancer: a 13 year analysis. Ann Thorac Surg. 2006;82:408–15. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2006.02.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ginsberg RJ, Rubinstein LV. Randomized trial of lobectomy versus limited resection for T1N0 non-small cell lung cancer. Ann Thorac Surg. 1995;60:615–22. doi: 10.1016/0003-4975(95)00537-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jensik RJ, Faber LP, Kittle CF. Segmental resection for bronchogenic carcinoma. Ann Thorac Surg. 1979;28:475–83. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weissberg D, Straehley CJ, Scully NM, et al. Less than lobar resections for bronchogenic carcinoma. Scand J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1993;27:121–6. doi: 10.3109/14017439309099098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pastorino U, Valente M, Bedini V, et al. Limited resection for stage I lung cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol. 1991;17:42–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lederle FA. Lobectomy versus limited resection in T1N0 lung cancer. Ann Thorac Surg. 1996;62:1249–50. doi: 10.1016/0003-4975(96)85176-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rubinstein LV, Ginsberg RJ. Lobectomy versus limited resection in T1N0 lung cancer. Ann Thorac Surg. 1995;60:615–22. doi: 10.1016/0003-4975(95)00537-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nakamura H, Kawasaki N, Taguchi M, et al. Survival following lobectomy versus limited resection for stage I lung cancer: a meta-analysis. Br J Cancer. 2005;92:1033–7. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nakamura H, Kazuyuki S, Kawasaki N, et al. History of limited resection for non-small cell lung cancer. Ann Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2005;11:356–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fields RC, Meyers BF. Sublobar resections for lung cancer. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2006;18:85–91. doi: 10.1053/j.semtcvs.2006.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pettiford BL, Schuchert MJ, Santos R, et al. Role of sublobar resection (segmentectomy and wedge resection) in the surgical management of non-small cell lung cancer. Thorac Surg Clin. 2007;17:175–90. doi: 10.1016/j.thorsurg.2007.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Warren WH, Faber LP. Segmentectomy versus lobectomy in patients with stage I pulmonary carcinoma. Five-year survival and patterns of intrathoracic recurrance. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1994;107:1087–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kodama K, Doi O, Higashiyama M, et al. Intentional limited resection for selected patients with T1N0M0 non-small cell lung cancer: a single institution study. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1997;114:347–53. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5223(97)70179-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Koike T, Yamato Y, Yoshiya K, et al. Intentional limited pulmonary resection for peripheral T1N0M0 small-sized lung cancer. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2003;125:924–8. doi: 10.1067/mtc.2003.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Campione A, Ligabue T, Luzzi L, et al. Comparison between segmentectomy and larger resection of stage IA non-small cell lung carcinoma. J Cardiovasc Surg (Torino) 2004;45:67–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Martin-Ucar AE, Makas A, Pilling JE, et al. A case-matched study of anatomical segmentectomy versus lobectomy for stage I lung cancer in high-risk patients. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2005;27:675–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2005.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mery CM, Pappas AN, Bueno R, et al. Similar ling-term survival of elderly patients with non-small cell lung cancer treated with lobectomy or wedge resection within the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database. Chest. 2005;128:237–45. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.1.237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Okada M, Nishio W, Sakamoto T, et al. Effect of tumour size on prognosis in patients with non-small cell lung cancer: the role of segmentectomy as a type of lesser resection. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2005;129:87–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2004.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Griffin JP, Eastridge CE, Tolley EA, et al. Wedge resection for non-small cell lung cancer inpatients with pulmonary insufficiency: prospective ten year survival. J Thorac Oncol. 2006;1:960–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kraev A, Rassias D, Vetto J, et al. Wedge resection versus lobectomy: 10-year survival in stage I primary lung cancer. Chest. 2007;131:136–40. doi: 10.1378/chest.06-0840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schuchert MJ, Pettiford BL, Keeley S, et al. Anatomic segmentectomy in the treatment of stage I non-small cell lung cancer. Ann Thorac Surg. 2007;84:926–33. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2007.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sakurai H, Dobashi Y, Mizutani E, et al. Bronchoalveolar carcinoma of the lung 3 centimeters or less in diameter: a prognosis assessment. Ann Thorac Surg. 2004;78:1728–33. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2004.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rusch VW, Tsuchiya R, Tsuboi M, et al. Surgery of bronchoalveolar carcinoma and “very early” adenocarcinoma: An evolving standard of care? J Thorac Oncol. 2006;1(9 Suppl):S27–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Asamura H, Suzuki K, Watanabe SI, et al. Clinicopathological study of resected subcentimeter lung cancers: a favorable prognosis for ground glass opacity lesions. Ann Thorac Surg. 2003;76:1016–22. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(03)00835-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nakata M, Sawada S, Saeki H, et al. Prospective study of thoracoscopic limited resection for ground glass opacity selected by computed tomography. Ann Thorac Surg. 2003;75:1601–6. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(02)04815-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nakamura H, Saji H, Ogata A, et al. Lung cancer patients showing pure ground glass opacity on computed tomography are good candidates for wedge resection. Lung Cancer. 2004;44:61–8. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2003.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yamada S, Kohno T. Video-assisted thoracic surgery for pure ground glass opacities 2 cm or less in diameter. Ann Thorac Surg. 2004;77:1911–5. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2003.12.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yoshida J, Nagai K, Yokose T, et al. Limited resection trial for pulmonary ground-glass opacity: fifty-case experience. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2005;129:991–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2004.07.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ohtsuka T, Watanabe K, Kaji M, et al. A clinicopathological study of resected pulmonary nodules with focal pure ground-glass opacity. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2006;30:160–3. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2006.03.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Greene FL, Page DL, Fleming ID, et al., editors. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 6th ed. New York (NY): Springer-Verlag; 2002. p. 435. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rusch VW, Asamura H, Watanabe H, et al. The IASLC lung cancer staging project: a proposal for a new international lymph node map in the forthcoming seventh edition of the TNM classification for lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2009;4:568. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181a0d82e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rami-Porta R, Ball D, Crowley J, et al. The IASLC Lung Cancer Staging Project: proposals for the revision of the T descriptors in the forthcoming (seventh) edition of the TNM classification for lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2007;2:593. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31807a2f81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Goldstraw P, Crowley J, Chansky K, et al. The IASLC Lung Cancer Staging Project: proposals for the revision of the TNM stage groupings in the forthcoming (seventh) edition of the TNM classification of malignant tumours. J Thorac Oncol. 2007;2:706. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31812f3c1a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Groome PA, Bolejack V, Crowley JJ, et al. The IASLC Lung Cancer Staging Project: validation of the proposals for revision of the T, N, and M descriptors and consequent stage groupings in the forthcoming (seventh) edition of the TNM classification of malignant tumours. J Thorac Oncol. 2007;2:694. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31812d05d5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Postmus PE, Brambilla E, Chansky K. The IASLC Lung Cancer Staging Project: proposals for revision of the M descriptors in the forthcoming (seventh) edition of the TNM classification of lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2007;2:686. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31811f4703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]