Abstract

Common infectious diseases, such as diarrhea, are still the major cause of death in children under 5-years-old, particularly in developing countries. It is known that there is a close relationship between nutrition and immune function. To evaluate the effect of a growing-up milk containing synbiotics on immune function and child growth, we conducted a cluster randomized, multicenter, double-blind, placebo controlled clinical trial in children between 18 and 36 months of age in Vietnam. Eligible children from eight and seven kindergartens were randomly assigned to receive test and isocaloric/ isoproteic control milk, respectively, for 5 months. We found that the blood immunoglobulin A (IgA) level and growth parameters were increased in the test group. Compared to the control group, there was also a trend of decreased vitamin A deficiency and fewer adverse events in the test group. These data suggest that a growing-up milk containing synbiotics may be useful in supporting immune function and promoting growth in children.

Keywords: synbiotics, growing-up milk, immune function, nutrition status, growth

Introduction

Malnutrition in children is still a major public health issue across the world, particularly in developing countries. According to the 2011 Millennium Development Goals Report, 23% of children under 5 years old are underweight.1 Malnutrition not only results in developmental retardation but also has a strong association with many diseases due to impaired immune function. The gut is the largest immunologically competent organ in the body and a balanced gut microbiota is important to maintaining immune homeostasis. The composition of endogenous microbiota and its metabolic activity can be affected by environmental factors, including nutrition.2 Probiotics, mainly lactobacilli and bifidobacteria, are defined by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) and the World Health Organization (WHO) joint expert panel as live microorganisms which when consumed in adequate amounts confer a health effect on the host. The beneficial effect of probiotics on infection outcomes have been reported in many studies.3–6 Besides rehydration during acute diarrhea, better nutrition and enhancing immune protection are the two related key factors in controlling the disease. A meta-analysis of 18 randomized, placebo controlled, doubleblind studies on the use of probiotics in acute diarrhea in children under 5 years old showed a mean reduction of duration by 0.8 days.7 Inulin and short-chain fructooligosaccharides (FOS) are among the most widely used prebiotics.8,9 They are natural food ingredients presented in edible plants and form parts of the normal human diet. Feeding 1.7 g/day of a blend of inulin and FOS to infants between 9- and 11-months-old enhanced their immune response to measles vaccine.10 The combination of probiotics and prebiotics, also known as synbiotics, is believed to be able to improve gastrointestinal health.11 Recently, González-Hernández and colleagues found that synbiotics improved immunological status in patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV).12 The synbiotic concept has been reviewed by De Vrese and Marteau.13

Like other developing countries, under-nutrition is a major challenge in Vietnam. About 17.5% of Vietnamese children under 5 years old are underweight in 2010 and the prevalence of iron deficiency anemia, zinc deficiency, and vitamin A deficiency are quite high.14 In these circumstances, interventions that provide complementary nutrients can play an important role in preventing nutrient deficiencies and growth retardation in children.15 Given the close relationship between nutritional status and immune function, we hypothesized that feeding with a growing-up milk (GUM) containing synbiotics (Lactobacillus paracasei NCC2461 and Bifidobacterium longum NCC3001; inulin and FOS) would improve immune competence (such as increase immunoglobulin A [IgA] levels) against common infectious diseases, such as gastrointestinal and upper respiratory tract infections, and promote child growth (eg, increasing both height and weight). To test this hypothesis, we conducted a cluster randomized, multicenter, double-blind, placebo controlled clinical trial in Vietnam.

Methods

Subjects and study design

A double-blind, cluster randomized, multicenter clinical trial was carried out in Gia Binh district, Bac Ninh Province, Vietnam. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee in Biomedical Research of the National Institute of Nutrition (Vietnam) and complied with the Helsinki Declaration as revised in 2000. Fifteen kindergartens from four communes with similar social economic conditions were involved in this study. The participating kindergartens were randomized into either control or test group. Children in these kindergartens were eligible for the trial if they were between 18 and 36-months-old, were not being breastfed, had no congenital or chronic diseases, and were not consuming any commercial products containing probiotics or prebiotics during the study period. The legal representatives of these children were fully informed, and the subjects were recruited into the study after obtaining the consent forms from their legal representatives.

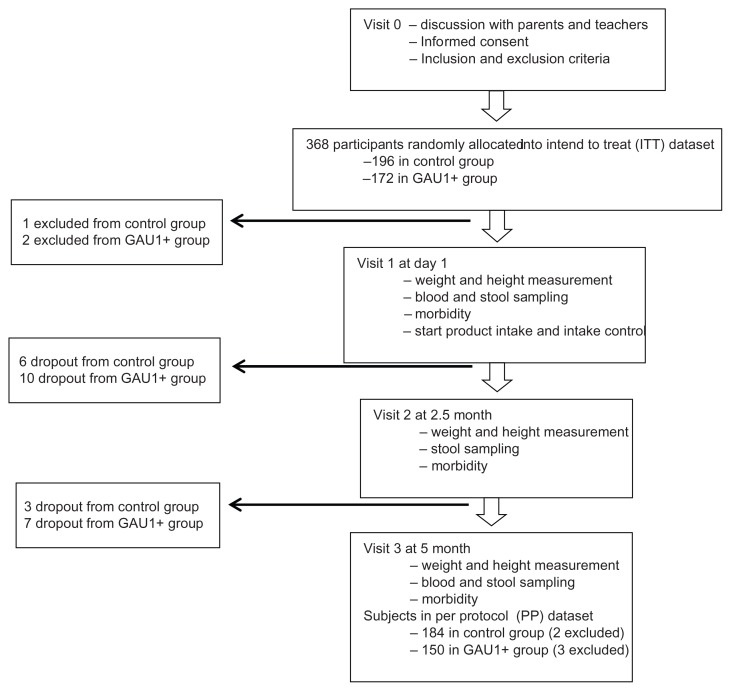

In total, 368 subjects were recruited and data from all these subjects formed the intend-to-treat (ITT) data set, with 196 and 172 in the control and test groups, respectively. Subjects who had milk allergy or who were participating or had participated in other clinical trials in the 6 months prior to the beginning of the study, were excluded. We also excluded subjects from the per protocol (PP) analysis data set if less than 50% of the total amount of assigned product was consumed. Thus, there were 184 subjects in the control group and 150 subjects in the test group in the PP data set (Fig. 1). Subjects were free to drop out at any time during the study.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the study.

The intervention period was 5 months, from mid-March to end of August 2010. Subjects in the control group were fed with a GUM consisting of adequate amount of proteins, carbohydrates, fats with vitamins, and minerals to support the children aged 18–36 months. Subjects in the test group were fed with GAU 1+ milk, an isocaloric and isoproteic GUM similar to control product (as shown in Supplementary Table 1), containing synbiotics (L. paracasei NCC2461 and B. longum NCC3001; inulin and FOS) and fortified with vitamins (A, C, and E), minerals (zinc and selenium), and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA).

Fecal IgA (f-IgA) and blood IgA (total IgA, tot-IgA) levels after 5 month feeding were measured as primary outcomes to evaluate immune function. The secondary measures were the growth (weight and height gain), nutritional status (anemia, zinc, and vitamin A deficiencies), the number and duration of episodes of gastrointestinal, and upper respiratory tract infections. Sample size was calculated based on the assumption of 40% treatment difference in f-IgA level with 80% power.

Intervention and follow up

All products were in powder and diluted with boiled water cooled down to 45ºC–50ºC. Subjects received two servings of suspended milk powder per day (one in the morning and another before leaving the kindergarten), 180 mL per serving, and 5 days per week. The target daily dose of each probiotic microorganism received in GAU 1+ milk treatment group was 108 colony-forming units and 2.2 grams of prebiotics on average. Teachers in the kindergartens filled the dietary book documenting product consumption on a daily basis to assess compliance. Adverse events, including upper and lower respiratory tract infections, gastrointestinal problems, medications or treatments initiated during the trial, were recorded in the case report form. The information was monitored weekly by the medical staff from the National Institute of Nutrition, Vietnam. Medical doctors visited each kindergarten three times during the study to measure anthropometric parameters, collect biological samples, and provide consultation in case of adverse events. The first visit was done right before feeding to evaluate the baseline status. The second and third visits were done at 2.5 and 5 months after the initiation of feeding, respectively, as shown in the flow diagram of the study (Fig. 1).

Sample collection, measurement, and analysis

Three milliliters of venous blood and 5 grams of stool sample were collected by medical staff at each visit in the morning on fasting condition. Zinc-free vacuette (Monovette; Sarstedt, Nombrecht, Germany) were used for blood collection. Plasma was obtained by centrifuging the blood at 4ºC at 4000 g for 15 minutes and stored at −70ºC until analysis. Concentrations of plasma zinc, vitamin A (retinol), IgA (tot-IgA) and hemoglobin (Hb) were measured using anatomic absorption spectrometer (AAS), high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and HemoCue methods, respectively. Stool samples were stored at −20ºC and the concentration of f-IgA was measured using ELISA (Immunodiagnostik AG, Bensheim, Germany). Body weight and height were also recorded on-site during each visit. The weight was measured using a UNISCALE balance (UNICEF); the recumbent length for children <2 years and standing height for children ≥2 years were also measured. The child’s weight and height were recorded to the nearest 0.1 kg and 0.1 cm, respectively. The nutritional status was calculated by using Epidata software with 2006 WHO growth standards. Each deficiency is defined as the following: Hb < 110 g/L for anemia; serum vitamin A <0.7 μmol/L for vitamin A deficiency; and serum zinc <65 μg/L for Zinc deficiency.

Statistical analysis

The statistical analysis was preplanned and documented. Two softwares, R 2.11.1 and SAS 9.3, were used. Primary outcomes were measures of immune parameters at 5 months after treatment (fecal and blood IgA). Values of IgA, Hb, vitamin A, and zinc were log transformed in order to achieve approximately normally distributed residuals and analyzed by a mixed model correcting for baseline. The treatment effect was modeled as a fixed effect and the kindergarten as a random effect. Since two primary outcomes were stated, the control of the experiment-wise false positive rate of 5% was obtained by applying the Bonferroni correction. For all statistical analyses the clustering factor (kindergartens) was considered by mixed models. In order to demonstrate the results comprehensively, statistical analysis data from both ITT and PP datasets were included in the tables where applicable.

Results

Baseline values

As shown in the flow diagram of the study (Fig. 1), three subjects were excluded according to the exclusion criteria (one and two from the control and GAU 1+ milk groups, respectively). Twenty-six subjects dropped out during the follow-up (nine and 17 in the control and GAU 1+ milk groups, respectively), and the overall dropout rate was thus 7.1%. Five subjects were excluded from the PP data set according to preset criteria described above (two and three in the control and GAU 1+ milk groups, respectively). The baseline samples of all subjects were collected in the first visit, the values of immunological and micronutrient parameters are presented in Tables 1 and 2, respectively. No statistically significant difference was found between the two groups indicating that the subjects were from the same population and the two groups were comparable.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of children in the study.

| CHARACTERISTIC | CONTROL (N = 196) | GAU 1+ (N = 172) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

||||

| N | % | N | % | ||

| Gender Male | 117 | 60 | 95 | 55 | |

|

| |||||

| Female | 79 | 40 | 77 | 45 | |

|

| |||||

| Number of siblings | 1 | 67 | 34 | 53 | 31 |

|

| |||||

| 2 | 98 | 50 | 90 | 52 | |

|

| |||||

| 3 | 25 | 13 | 26 | 15 | |

|

| |||||

| 4 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 2 | |

|

| |||||

| Pets | No | 66 | 34 | 82 | 48 |

|

| |||||

| Yes | 130 | 66 | 90 | 52 | |

|

| |||||

| Mean | Quartile | Mean | Quartile | ||

|

|

|

||||

| Age at enrolment (years) | 2.44 | (2.16, 2.90) | 2.58 | (2.24, 2.86) | |

|

| |||||

| Weight (Kg) | 11.7 | (10.7, 12.6) | 11.9 | (11.1, 12.6) | |

|

| |||||

| Height (cm) | 86.8 | (83.1, 89.6) | 86.7 | (84.0, 90.0) | |

|

| |||||

| BMI (Kg/cm2) | 15.7 | (14.9, 16.4) | 15.8 | (15.2, 16.4) | |

|

| |||||

| Weight for age z-score | −0.910 | (−1.41, −0.275) | −0.790 | (−1.21, −0.275) | |

|

| |||||

| Height for age z-score | −1.35 | (−1.87, −0.765) | −1.34 | (−1.90, −0.865) | |

|

| |||||

| BMI for age z-score | −0.020 | (−0.580, 0.520) | 0.115 | (−0.368, 0.600) | |

Note:P >0.05 for all parameters.

Table 2.

Summary of baseline parameters.

| DATASET PARAMETERS | CONTROL | GAU 1+ | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

||||||

| N | MEAN† | S.D. | N | MEAN | S.D. | ||

| ITT | f-IgA (mg/g) | 178 | 298 | 295 | 157 | 271 | 258 |

|

| |||||||

| tot-IgA (mg/mL) | 191 | 55.6 | 17.8 | 166 | 55.8 | 17.5 | |

|

| |||||||

| Hb (g/L) | 191 | 115 | 10.3 | 168 | 115 | 9.6 | |

|

| |||||||

| Vitamin A (μmol/L) | 191 | 0.993 | 0.431 | 166 | 1.05 | 0.616 | |

|

| |||||||

| Zn (μg/dl) | 191 | 59.6 | 10.5 | 166 | 64.0 | 13.2 | |

|

| |||||||

| PP | f-IgA (mg/g) | 169 | 294 | 294 | 138 | 266 | 261 |

|

| |||||||

| tot-IgA (mg/ml) | 182 | 55.9 | 18.0 | 150 | 56.0 | 18.1 | |

|

| |||||||

| Hb (g/L) | 182 | 115 | 10.4 | 151 | 115 | 8.9 | |

|

| |||||||

| Vitamin A (μmol/L | 182 | 0.993 | 0.436 | 150 | 1.033 | 0.554 | |

|

| |||||||

| Zn (μg/dl) | 182 | 59.7 | 10.7 | 150 | 63.7 | 12.7 | |

Note:

Geometric mean.

Abbreviations: S.D, standard deviation; ITT, intend to treat dataset; PP, per protocol dataset; f-IgA, faecal IgA; tot-IgA, blood IgA.

Effect of the intervention on immunological and micronutrient parameters

Immunological and micronutrient parameters were measured as described in the materials and methods. As shown in Table 3, trends of positive changes were observed in f-IgA, Hb, vitamin A, and zinc levels in GAU 1+ milk group. Moreover, after 5 months feeding, an increase in tot-IgA was found to be statistically significant in both the ITT and PP data sets, suggesting that GAU 1+ milk had an impact on immune function.

Table 3.

Summary of changes comparing to control group.

| PARAMETERS | DATASET | VISIT | Δ† | 95% CI | P-VALUE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| f-IgA | ITT | 2.5 months | 26.0% | (−19.8% 71.9%) | 0.27 |

| 5 months | 33.2% | (−13.4% 79.8%) | 0.16 | ||

| PP | 2.5 months | 24.2% | (22.8% 71.3%) | 0.31 | |

| 5 months | 32.0% | (−15.5% 79.5%) | 0.19 | ||

| tot-IgA | ITT | 5 months | 8.5% | (3.70% 13.3%) | <0.01 |

| PP | 5 months | 8.6% | (3.70% 13.6%) | <0.01 | |

| Hb | ITT | 5 months | 1.06% | (−0.80% 2.91%) | 0.26 |

| PP | 5 months | 0.89% | (−0.96% 2.75%) | 0.34 | |

| Vitamin A | ITT | 5 months | 4.37% | (−0.51% 9.25%) | 0.08 |

| PP | 5 months | 4.25% | (−0.71% 9.21%) | 0.09 | |

| Zn | ITT | 5 months | 1.01% | (−3.88% 5.91%) | 0.69 |

| PP | 5 months | 4.25% | (−3.73% 6.36%) | 0.61 |

Note:

Percentage of change, calculated as log-transformed values of GAU 1+ group minus that of control group, and expressed as percentage.

Abbreviations: f-IgA, fecal IgA; tot-IgA, blood IgA; ITT, intend to treat dataset; PP, per protocol dataset.

The capacity of GAU 1+ milk feeding in reducing the risk of Hb, Vitamin A, and zinc deficiencies was analyzed after 5 months of intervention. Although none of these measures reached statistical significance (Table 4), positive trends in favor to GAU 1+ milk group were observed in anemia, vitamin A, and zinc deficiencies. It is worthwhile to note that the control group was fed with a GUM that was also fortified with vitamins and minerals to support children 18–36-months-old which could have masked, at least partially, the difference between the two study groups.

Table 4.

Prevalence of micronutrient deficiency.

| DEFICIENCY | VISIT | CONTROL | GAU1+ | OR | 95% CI | P | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||||||

| N | NUMBER OF DEFICIENCY | % | N | NUMBER OF DEFICIENCY | % | |||||

| Anemia | Baseline | 191 | 55 | 28.8 | 168 | 45 | 26.8 | |||

|

| ||||||||||

| 5 month | 182 | 26 | 14.3 | 151 | 18 | 11.9 | 0.85 | (0.42, 1.73) | 0.63 | |

|

| ||||||||||

| Vitamin A | Baseline | 191 | 17 | 8.9 | 166 | 18 | 10.8 | |||

|

| ||||||||||

| 5 month | 182 | 11 | 6.0 | 151 | 2 | 1.3 | 0.21 | (0.04, 1.10) | 0.06 | |

|

| ||||||||||

| Zinc | Baseline | 191 | 137 | 71.7 | 166 | 93 | 56.0 | |||

|

| ||||||||||

| 5 month | 182 | 110 | 60.4 | 151 | 64 | 42.4 | 0.75 | (0.35, 1.62) | 0.44 | |

Effect of the intervention on growth

Another aspect of the study was to investigate the effect of GAU 1+ milk on child growth. Anthropometric parameters were monitored during the study. As illustrated in Table 5, a positive effect was observed in both body weight and height growth after 5 months of GAU 1+ milk feeding (statistically significant in both ITT and PP data sets). After 2.5 months of feeding, this beneficial effect could already be observed. Overall, the body mass indeces (BMI) of Vietnamese children were within the WHO-accepted boundaries. The BMI Z score after a 5-month intervention was slightly higher in the GAU 1+ milk group (P < 0.05 in PP dataset, P = 0.06 in ITT dataset), and was likely linked with the increase in both weight and height. These results also highlighted the positive impact of GAU 1+ milk intake on growth.

Table 5.

Summary of changes in growth comparing to control group.

| PARAMETERS | DATASET | VISIT | Δ† | 95% CI | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weight (kg) | ITT | 2.5 months | 0.05 | (−0.08 0.18) | 0.47 |

| 5 months | 0.43 | (0.30 0.56) | <0.01 | ||

| PP | 2.5 months | 0.07 | (−0.06 0.21) | 0.29 | |

| 5 months | 0.43 | (0.31 0.58) | <0.01 | ||

| Weight Z score | ITT | 2.5 months | 0.04 | (−0.05 0.12) | 0.44 |

| 5 months | 0.28 | (0.18 0.37) | <0.01 | ||

| PP | 2.5 months | 0.07 | (−0.04 0.15) | 0.25 | |

| 5 months | 0.29 | (0.20 0.38) | <0.01 | ||

| Height (cm) | ITT | 2.5 months | 0.33 | (0.03 0.64) | <0.05 |

| 5 months | 1.00 | (0.69 1.31) | <0.01 | ||

| PP | 2.5 months | 0.36 | (0.05 0.68) | <0.05 | |

| 5 months | 1.03 | (0.72 1.34) | <0.01 | ||

| Height Z score | ITT | 2.5 months | 0.09 | (0.00 0.18) | 0.06 |

| 5 months | 0.29 | (0.20 0.38) | <0.01 | ||

| PP | 2.5 months | 0.10 | (0.00 0.19) | <0.05 | |

| 5 months | 0.30 | (0.21 0.39) | <0.01 | ||

| BMI (kg/m2) | ITT | 2.5 months | −0.07 | (−0.24 0.10) | 0.40 |

| 5 months | 0.14 | (−0.04 0.31) | 0.12 | ||

| PP | 2.5 months | −0.04 | (−0.22 0.13) | 0.62 | |

| 5 months | 0.16 | (−0.02 0.33) | 0.08 | ||

| BMI Z score | ITT | 2.5 months | −0.04 | (−0.17 0.10) | 0.59 |

| 5 months | 0.13 | (−0.01 0.26) | 0.06 | ||

| PP | 2.5 months | −0.01 | (−0.15 0.12) | 0.85 | |

| 5 months | 0.15 | (0.01 0.28) | <0.05 |

Note:

Percentage of change, calculated as log-transformed values of GAU 1+ group minus that of control group, and expressed as percentage.

Abbreviations: ITT, intend to treat dataset; PP, per protocol dataset.

Effect of the intervention on incidence of infections

We have reported above that GAU 1+ milk feeding supported some immune functions and child growth. To investigate the effect of GAU 1+ milk feeding on infections, we recorded all the adverse events during the study, including upper and lower respiratory tract infections, and gastrointestinal problems. Although no statistical significance was reached (Supplementary Table 2), a trend was observed, ie, GAU1+ milk feeding reduced the incidences in all categories of adverse events, including upper respiratory tract infections and gastrointestinal problems.

Discussion

The tested product in this study, GAU 1+, is a GUM containing a synbiotic blend of probiotics (L. paracasei and B. longum) and prebiotics (FOS and inulin). There are two reasons for choosing this probiotic mix. First, it has been shown to be well tolerated and safe to use in children;16 second, it combines the complementary benefits of bifidobacteria and lactobacilli. Both in vitro and animal studies revealed that L. paracasei NCC2461 was able to modulate immune function at both mucosal and systemic levels.17–19L. paracasei has also been shown to have a positive effect on the management of infectious diarrhea and the treatment of severe watery diarrhea in children.20 Bifidobacteria contribute to healthy gut environment and support gut defense development in children.21–23 Several studies have suggested that the B. longum strain NCC3001 (also known as BB536) was able to inhibit the growth of enteropathogens and protect rodents from gastrointestinal infections.24–26 Furthermore, B. longum has been associated with the improvement of gastrointestinal discomfort induced by antibiotics in healthy subjects.27–29 Thus, it is likely that this probiotic mix contributes to the beneficial effects we observed in this study.

In fact, in order to evaluate the effect of GAU 1+ milk on immune function and growth, a pilot clinical trial was conducted prior to the current study at different locations in the same region and using the same formulas and similar design. One hundred and fifty children from four classrooms in two kindergartens received either the test (GAU1+) or the control product (each kindergarten allocated to one of the treatments). We were aware that all findings of the pilot trial might be confounded by the kindergarten characteristics, and therefore no inferential statistics were conducted and only descriptive statistical analysis was done. Compared to control group, GAU 1+ milk feeding group showed an increased blood IgA level, a decreased number of diarrhea and respiratory infection episodes, and ameliorated micro-nutritional status (Supplementary Table 3). These data encouraged us to carry out a larger scale clinical trial which is the current study reported here.

GAU1+ milk is also fortified with vitamins and minerals that are important to immune function and growth. Therefore, it is reasonable to assume that these micronutrients could contribute, at least in part, to the positive findings in this study. However, as stated above, the control milk also contained adequate amounts of vitamins and minerals to support child growth. In that respect, we highlighted the synbiotic blend in GAU 1+ milk because it was a unique feature of GAU 1+. We have no intention to imply that it was the only contributor of the effects observed in this study. As a product trial, instead of focusing on the effect of each ingredient, we assessed GAU 1+ milk as a whole.

Body weight and height are important anthropometric parameters for child growth. According to baseline data, while the BMI was relatively normal, the body weight and height of children in this clinical study were approximately 1standard deviation (SD) below WHO’s standard.30 Thus, a nutritional intervention that increases the body weight and height and maintains normal BMI is considered as beneficial to this population. Indeed, compared to the controls, both body weight and height were increased in the GAU 1+ milk group, while BMI remained normal for this age category. Considering the moderate—but still of interest—effect on micronutrients levels, these overall changes in anthropometric parameters reflected an improved nutritional status, and suggested that GAU 1+ milk may support an optimal growth. Nevertheless, an extended evaluation up to 1 year or longer would be necessary to consolidate this benefit in the long term.

Due to the complexity of the immune system, there is no single biomarker that can represent its entire function status. Nonetheless, one of the major features of immune defense is the capacity of the host to produce antibodies at the mucosal surface that plays a critical role in protecting the host against infection;31 IgA level is acknowledged as a suitable parameter in human intervention studies.32 Therefore we measured IgA concentrations in blood and fecal samples to assess a relevant aspect of immune status. A relative decline in f-IgA level was observed in both groups during the early phase of the trial. This very likely reflected a local seasonal pattern, ie, higher incidence of infections from December—January followed by a progressive reduction from February—March. f-IgA production is a hallmark of body response to gastrointestinal infection. Considering that the current clinical trial was started in March, it was not a surprise to see the level of this marker following the same path. A high variability in f-IgA measure clearly affected this outcome and likely explains the lack of statistical significance which is a weakness of this study. As a complementary measure to immune function assessment, total IgA in blood was found to be significantly increased in the GAU 1+ milk feeding group, confirming our previous findings in the pilot trial. A trend in reduction of the incidence of adverse events, such as upper respiratory tract infections and gastrointestinal problems, in favor of the GAU 1+ milk group was also observed.

Conclusion

Altogether, these results suggest that GAU 1+, a growingup milk containing synbiotics, may be useful in supporting immune function and promoting child growth.

Supplementary Materials

Table 1.

Composition of the products (daily intake).

| UNIT | CONTROL | GAU 1+ | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Energy | (Kcal) | 166.1 | 163.7 |

| Protein | (gram) | 6.7 | 6.1 |

| Lipid | (gram) | 7.3 | 7.7 |

| Carbohydrate | (gram) | 18.4 | 17.5 |

Table 2.

The incidence of infections during the study.

| CONTROL | GAU1+ | OR | 95% CI | P | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

||||||||

| N | NO. CASES | % | N | NO. CASES | % | ||||

| URTI | 196 | 93 | 47.4 | 172 | 63 | 36.6 | 0.43 | (0.07, 2.70) | 0.34 |

|

| |||||||||

| LRTI | 196 | 18 | 9.2 | 172 | 4 | 2.3 | 0.1 | (0.00, 5.00) | 0.23 |

|

| |||||||||

| GI-problem | 196 | 28 | 14.3 | 172 | 18 | 10.5 | 0.57 | (0.16, 2.04) | 0.36 |

|

| |||||||||

| Others | 196 | 24 | 12.2 | 172 | 12 | 7 | 0.38 | (0.04, 3.62) | 0.37 |

Abbreviations: URTI, upper respiratory tract infection; LRTI, lower respiratory tract infection; GI, gastrointestinal.

Table 3.

Main results from pilot trial.

| PARAMETERS | CONTROL (N = 64) | GAU 1+ (N = 68) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

||||||

| BASELINE | 5 MONTH | Δ† | BASELINE | 5 MONTH | Δ | ||

| IgA | tot- IgA (mg/ml) | 0.56 ± 0.28 | 0.60 ± 0.25 | 0.05 ± 0.17 | 0.58 ± 0.22 | 0.70 ± 0.22 | 0.12 ± 0.14 |

|

| |||||||

| Micronutrient Hb(g/L) | 110.4 ± 9.7 | 119.7 ± 7.7 | 9.3 ± 4.8 | 112.3 ± 8.1 | 123.6 ± 8.6 | 11.3 ± 5.1 | |

|

| |||||||

| Vitamin A(μmol/L) | 1.03 ± 0.34 | 1.06 ± 0.33 | 0.03 ± 0.28 | 1.06 ± 0.22 | 1.12 ± 0.24 | 0.06 ± 0.26 | |

|

| |||||||

| Zn (μg/dl) | 67.8 ± 21.6 | 82.6 ± 20.8 | 14.8 ± 17.9 | 65.9 ± 20.7 | 89.6 ± 16.6 | 23.7 ± 18.7 | |

|

| |||||||

| Deficiencies | Anemia | 45.3% | 7.8% | −37.5% | 39.7% | 4.4% | −35.3% |

|

| |||||||

| Vitamin A | 9.4% | 7.8% | −1.6% | 4.4% | 1.5% | −2.9% | |

|

| |||||||

| Zn | 50.0% | 25.0% | −25.0% | 45.6% | 5.9% | −39.7% | |

|

| |||||||

| Diarrhea | No. of episodes | 1.42 ± 0.55 | 1.16 ± 0.51 | ||||

|

| |||||||

| No. of days/episode | 3.26 ± 1.25 | 2.74 ± 1.45 | |||||

|

| |||||||

| URTI | No. of episodes | 2.80 ± 0.10 | 2.30 ± 0.90 | ||||

|

| |||||||

| No. of days/episode | 5.10 ± 2.50 | 4.60 ± 2.40 | |||||

Notes:

difference between baseline and 5 months of feeding. IgA, Hb, vitamin A, Zn levels, the number of episodes and the duration of episode were expressed as mean ± SD.

Abbreviation: tot-IgA, blood IgA.

Footnotes

COMPETING INTERESTS: Author(s) disclose no potential conflicts of interest.

Author Contributions

JB, NXN, DG, and AG designed the study. NXN, PNTL, VTKH, and AG conducted the trials. DG performed statistical analysis. DW, DG, NXN, and JB analyzed the data and wrote the article. JB and NXN had primary responsibility for final contents. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

DISCLOSURES AND ETHICS

As a requirement of publication the authors have provided signed confirmation of their compliance with ethical and legal obligations including but not limited to compliance with ICMJE authorship and competing interests guidelines, that the article is neither under consideration for publication nor published elsewhere, of their compliance with legal and ethical guidelines concerning human and animal research participants (if applicable), and that permission has been obtained for reproduction of any copyrighted material. This article was subject to blind, independent, expert peer review. The reviewers reported no competing interests.

FUNDING: This project was supported by a Nestlé research fund.

REFERENCES

- 1.The Millennium Development Goals Report 2011 [webpage on the Internet] New York: United Nation; 2012. [Accessed: July 30th, 2013]. Available from: http://www.un.org/millenniumgoals/reports.shtml. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schiffrin EJ, Blum SRC, Benyacoub J. Probiotics in infant feeding. Middle East Pediatrics. 2004;9(4):129–34. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weizman Z, Asli G, Alsheikh A. Effect of a probiotic infant formula on infections in child care centers: comparison of two probiotic agents. Pediatrics. 2005;115(1):5–9. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-1815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shornikova AV, Casas IA, Isolauri E, Mykkänen H, Vesikari T. Lactobacillus reuteri as a therapeutic agent in acute diarrhea in young children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1997;24(4):399–404. doi: 10.1097/00005176-199704000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shornikova AV, Casas IA, Mykkänen H, Salo E, Vesikari T. Bacteriotherapy with Lactobacillus reuteri in rotavirus gastroenteritis. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1997;16(12):1103–7. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199712000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shornikova AV, Isolauri E, Burkanova L, Lukovnikova S, Vesikari T. A trial in the Karelian Republic of oral rehydration and Lactobacillus GG for treatment of acute diarrhoea. Acta Paediatr. 1997;86(5):460–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1997.tb08913.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huang JS, Bousvaros A, Lee JW, Diaz A, Davidson EJ. Efficacy of probiotic use in acute diarrhea in children: a meta-analysis. Dig Dis Sci. 2002;47(11):2625–34. doi: 10.1023/a:1020501202369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Veereman G. Pediatric applications of inulin and oligofructose. J Nutr. 2007;137(11 Suppl):2585S–9. doi: 10.1093/jn/137.11.2585S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bouhnik Y, Achour L, Paineau D, Riottot M, Attar A, Bornet F. Four-week short chain fructo-oligosaccharides ingestion leads to increasing fecal bifidobacteria and cholesterol excretion in healthy elderly volunteers. Nutr J. 2007;6:42. doi: 10.1186/1475-2891-6-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Haschke F, Firmansyah A, Meng M, Steenhout P, Carrie AL. Functional food for infants and children. Monatsschrift Kinderheilkunde. 2001;149(Supple 1):S66–70. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chouraqui JP, Grathwohl D, Labaune JM, et al. Assessment of the safety, tolerance, and protective effect against diarrhea of infant formulas containing mixtures of probiotics or probiotics and prebiotics in a randomized controlled trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;87(5):1365–73. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/87.5.1365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.González-Hernández LA, Jave-Suarez LF, Fafutis-Morris M, et al. Synbiotic therapy decreases microbial translocation and inflammation and improves immunological status in HIV-infected patients: a double-blind randomized controlled pilot trial. Nutr J. 2012;11:90. doi: 10.1186/1475-2891-11-90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Vrese M, Marteau PR. Probiotics and prebiotics: effects on diarrhea. J Nutr. 2007;137(3):803S–11. doi: 10.1093/jn/137.3.803S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huong CTT, Ninh NX, Nhien NV. Efficacy of using complementary feeding food fortified with micronutrient on anemia, zinc and vitamin A status in weaning infant. Practic Medical Journal (in Vietnamese) 2004:80–4. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ninh NX, Thissen JP, Collette L, Gerard G, Khoi HH, Ketelslegers JM. Zinc supplementation increases growth and circulating insulin-like growth factor I (IGF-I) in growth-retarded Vietnamese children. Am J Clin Nutr. 1996;63(4):514–9. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/63.4.514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Simakachorn N, Bibiloni R, Yimyaem P, et al. Tolerance, safety, and effect on the faecal microbiota of an enteral formula supplemented with pre- and probiotics in critically ill children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2011;53(2):174–81. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e318216f1ec. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.von der Weid T, Bulliard C, Schiffrin EJ. Induction by a lactic acid bacterium of a population of CD4(+) T cells with low proliferative capacity that produce transforming growth factor beta and interleukin–10. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2001;8(4):695–701. doi: 10.1128/CDLI.8.4.695-701.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Prioult G, Pecquet S, Fliss I. Stimulation of interleukin-10 production by acidic beta-lactoglobulin-derived peptides hydrolyzed with Lactobacillus paracasei NCC2461 peptidases. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2004;11(2):266–71. doi: 10.1128/CDLI.11.2.266-271.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vidal K, Benyacoub J, Moser M, et al. Effect of Lactobacillus paracasei NCC2461 on antigen-specific T-cell mediated immune responses in aged mice. Rejuvenation Res. 2008;11(5):957–64. doi: 10.1089/rej.2008.0780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sarker SA, Sultana S, Fuchs GJ, et al. Lactobacillus paracasei strain ST11 has no effect on rotavirus but ameliorates the outcome of nonrotavirus diarrhea in children from Bangladesh. Pediatrics. 2005;116(2):e221–8. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-2334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chiang BL, Sheih YH, Wang LH, Liao CK, Gill HS. Enhancing immunity by dietary consumption of a probiotic lactic acid bacterium (Bifidobacterium lactis HN019): optimization and definition of cellular immune responses. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2000;54(11):849–55. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1601093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sazawal S, Dhingra U, Hiremath G, et al. Effects of Bifidobacterium lactis HN019 and prebiotic oligosaccharide added to milk on iron status, anemia, and growth among children 1 to 4 years old. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2010;51(3):341–6. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e3181d98e45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sazawal S, Dhingra U, Hiremath G, et al. Prebiotic and probiotic fortified milk in prevention of morbidities among children: community-based, randomized, double-blind, controlled trial. PLoS One. 2010;5(8):e12164. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Araya-Kojima T, Yaeshima T, Ishibashi N, Shirnamura S, Hayasawa H. Inhibitory Effects of Bifidobacterium longum BB536 on Harmful Intestinal Bacteria. Bifidobacteria Microflora. 1995;14(2):59–66. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bruno FA, Shah NP. Inhibition of pathogenic and putrefactive microorganisms by Bifidobacterium sp. Milchwissenschaft. 2002;57(11–12):617–21. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yamazaki S, Kamimura H, Momose H, Kawashima T, Ueda K. Protective effect of Bifidobacterium-monoassociation against lethal activity of Escherichia coli. Bifidobacteria Microflora. 1982;1:55–9. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Colombel JF, Cortot A, Neut C, Romond C. Yoghurt with Bifidobacterium longum reduces erythromycin-induced gastrointestinal effects. Lancet. 1987;2(8549):43. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(87)93078-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bunout D, Barrera G, Hirsch S, et al. Effects of a nutritional supplement on the immune response and cytokine production in free-living Chilean elderly. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2004;28(5):348–54. doi: 10.1177/0148607104028005348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Puccio G, Cajozzo C, Meli F, Rochat F, Grathwohl D, Steenhout P. Clinical evaluation of a new starter formula for infants containing live Bifidobacterium longum BL999 and prebiotics. Nutrition. 2007;23(1):1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2006.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.The WHO Child Growth Standards. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2013. [Date accessed: July 30th, 2013]. Available from: http://www.who.int/childgrowth/en/ [Google Scholar]

- 31.Underdown BJ, Schiff JM. Immunoglobulin A: strategic defense initiative at the mucosal surface. Annu Rev Immunol. 1986;4:389–417. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.04.040186.002133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Albers R, Antoine JM, Bourdet-Sicard R, et al. Markers to measure immunomodulation in human nutrition intervention studies. Br J Nutr. 2005;94(3):452–81. doi: 10.1079/bjn20051469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table 1.

Composition of the products (daily intake).

| UNIT | CONTROL | GAU 1+ | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Energy | (Kcal) | 166.1 | 163.7 |

| Protein | (gram) | 6.7 | 6.1 |

| Lipid | (gram) | 7.3 | 7.7 |

| Carbohydrate | (gram) | 18.4 | 17.5 |

Table 2.

The incidence of infections during the study.

| CONTROL | GAU1+ | OR | 95% CI | P | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

||||||||

| N | NO. CASES | % | N | NO. CASES | % | ||||

| URTI | 196 | 93 | 47.4 | 172 | 63 | 36.6 | 0.43 | (0.07, 2.70) | 0.34 |

|

| |||||||||

| LRTI | 196 | 18 | 9.2 | 172 | 4 | 2.3 | 0.1 | (0.00, 5.00) | 0.23 |

|

| |||||||||

| GI-problem | 196 | 28 | 14.3 | 172 | 18 | 10.5 | 0.57 | (0.16, 2.04) | 0.36 |

|

| |||||||||

| Others | 196 | 24 | 12.2 | 172 | 12 | 7 | 0.38 | (0.04, 3.62) | 0.37 |

Abbreviations: URTI, upper respiratory tract infection; LRTI, lower respiratory tract infection; GI, gastrointestinal.

Table 3.

Main results from pilot trial.

| PARAMETERS | CONTROL (N = 64) | GAU 1+ (N = 68) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

||||||

| BASELINE | 5 MONTH | Δ† | BASELINE | 5 MONTH | Δ | ||

| IgA | tot- IgA (mg/ml) | 0.56 ± 0.28 | 0.60 ± 0.25 | 0.05 ± 0.17 | 0.58 ± 0.22 | 0.70 ± 0.22 | 0.12 ± 0.14 |

|

| |||||||

| Micronutrient Hb(g/L) | 110.4 ± 9.7 | 119.7 ± 7.7 | 9.3 ± 4.8 | 112.3 ± 8.1 | 123.6 ± 8.6 | 11.3 ± 5.1 | |

|

| |||||||

| Vitamin A(μmol/L) | 1.03 ± 0.34 | 1.06 ± 0.33 | 0.03 ± 0.28 | 1.06 ± 0.22 | 1.12 ± 0.24 | 0.06 ± 0.26 | |

|

| |||||||

| Zn (μg/dl) | 67.8 ± 21.6 | 82.6 ± 20.8 | 14.8 ± 17.9 | 65.9 ± 20.7 | 89.6 ± 16.6 | 23.7 ± 18.7 | |

|

| |||||||

| Deficiencies | Anemia | 45.3% | 7.8% | −37.5% | 39.7% | 4.4% | −35.3% |

|

| |||||||

| Vitamin A | 9.4% | 7.8% | −1.6% | 4.4% | 1.5% | −2.9% | |

|

| |||||||

| Zn | 50.0% | 25.0% | −25.0% | 45.6% | 5.9% | −39.7% | |

|

| |||||||

| Diarrhea | No. of episodes | 1.42 ± 0.55 | 1.16 ± 0.51 | ||||

|

| |||||||

| No. of days/episode | 3.26 ± 1.25 | 2.74 ± 1.45 | |||||

|

| |||||||

| URTI | No. of episodes | 2.80 ± 0.10 | 2.30 ± 0.90 | ||||

|

| |||||||

| No. of days/episode | 5.10 ± 2.50 | 4.60 ± 2.40 | |||||

Notes:

difference between baseline and 5 months of feeding. IgA, Hb, vitamin A, Zn levels, the number of episodes and the duration of episode were expressed as mean ± SD.

Abbreviation: tot-IgA, blood IgA.