Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Primary hepatic lymphoma is a rare malignancy which misdiagnosis and mistreatment is very frequent. Differential diagnosis of the hepatic lesion, based on the noninvolvement of blood vessels, includes: fatty infiltration, cirrhosis, amyloid infiltration, primary hepatomas, and metastatic neoplasms.

PRESENTATION OF CASE

We describe a case of a 69-year-old man who presented with 15% weight loss and general fatigue over the previous 9 months. Physical examination revealed hepatomegaly without lymphadenopathy or splenomegaly. Magnetic resonance imaging showed a 13 cm × 9 cm × 11 cm tumor on the right liver associated with normal levels of alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) and carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA). After two negatives ultrasonography-guided needle liver biopsies, the third one showed diffuse infiltration of large sized lymphoid cells. Immunohistochemical findings demonstrated the B-lymphocyte lineage of the tumor. The patient received R-CHOP therapy (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone, and rituximab) with good response.

DISCUSSION

It is important to recognize PHL because it responds favorably to chemotherapy and may have a better prognosis than hepatocellular carcinoma or metastatic disease of the liver. When imaging findings on CT scans and MRI are nonspecific, a biopsy is needed not only for a definitive diagnosis but also for identifying the immunophenotype of the PHL. This type of lesion is highly chemosensitive and early aggressive chemotherapy may result in sustained remission.

CONCLUSION

This case emphasizes the importance of effective recognition of PHL considering its good response to chemotherapy and the possibility of sustained remission if early aggressive treatment is implemented.

Keywords: Primary lymphoma, Liver, Diagnosis, Treatment

1. Introduction

Primary hepatic lymphoma (PHL) is a tumor confined to the liver without evidence of lymphomatous involvement of spleen, lymph nodes, bone marrow or other lymphoid structures.1 PHL is a very rare malignancy, and constitutes about 0.016% of all cases of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma.2 Most patients are treated with chemotherapy, using different combinations of drugs.3 However, optimal therapy is still unclear and the outcomes are uncertain. The majority of PHL cases originate from B cells, and T-cell lymphoma is less common.3 Misdiagnosis is frequent and cases of unnecessary resection have been reported.2 The purpose of this case report is to describe a case of PHL and emphasize the importance of an accurate diagnosis before implementing a therapeutic plan.

2. Case presentation

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images. In October 2011, a 69-year-old white man presented with 15% weight loss (22 kg), mental confusion, nocturnal fever, difficulty in ambulation, limb weakness and general fatigue experienced over the previous 9 months. Physical examination revealed hepatomegaly, palpable 3 cm below the right costal margin, without lymphadenopathy or splenomegaly.

2.1. Investigation

The results of the complete blood count were normal apart from mild leukocytosis (white blood cell count: 13,340/μL). The results of liver function tests were aspartate aminotransferase (AST): 58 U/L, alanine aminotransferase (ALT): 130 U/L, gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT): 305 U/L, alkaline phosphatase (ALP): 601 U/L, total bilirubin (TB): 0.7 mg/dL and albumin: 3.4 g/dL. Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) level was found to be 2648 U/L. Results of serologic tests for hepatitis B virus, hepatitis C virus, human immunodeficiency virus, and human T-lymphotropic virus-1 were negative. FAN and VDRL were negative. Tumor markers levels are described as follows: carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA): 0.3 ng/mL, carbohydrate antigen 19–9 (CA 19.9): 7.0 U/mL, and alpha-fetoprotein (AFP): 4.58 ng/mL.

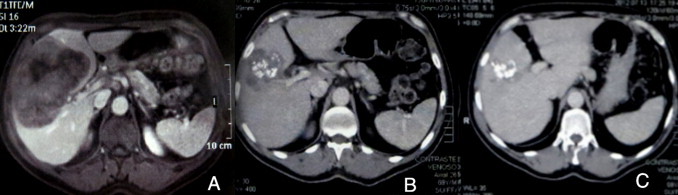

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) findings showed a hypointense area on T1-weighted images sized of 13 cm × 9 cm × 11 cm, and hyperintense on T2-weighted images (Fig. 1a). There was no mediastinal lymphadenopathy or brain involvement on CT scan.

Fig. 1.

(a) Axial T1-weighted MRI, showing a hypoattenuating lesion, with a central area of low intensity indicating necrosis. Images 6 months (b) and 12 months (c) after treatment.

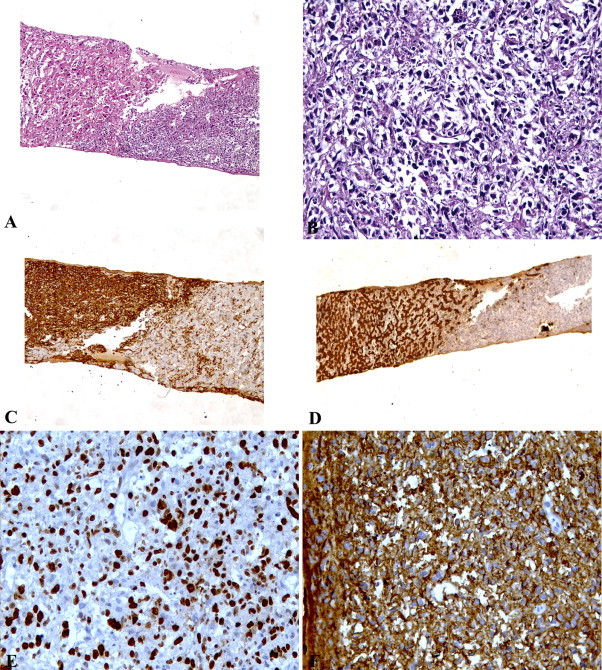

Two ultrasonography-guided needle liver biopsies were found negative and the third one showed diffuse infiltration of large sized lymphoid cells. Immunohistochemistry (Fig. 2): positive CD45-LCA, positive CD20; positive Ki67 in 80% of atypical cells; CD99 positive; vimentin positive. CD3, CD15, CD30, ACT, CK, CRO, DES, HMB45, and S100 were all negative. The diagnosis of primary large cells non-Hodgkin B-cell lymphoma was made.

Fig. 2.

Histopathology of the liver biopsy shows (a) normal hepatocytes and tumor cells (H&E, 100×) and (b) infiltration of large lymphoid cells (H&E, 400×), (c) positive CD45-LCA (100×), (d) positive cytokeratin in normal hepatocytes (100×), (e) positive Ki67 (400×) and (f) positive CD20 (400×).

Bone marrow aspiration and biopsy examination showed no evidence of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma.

2.2. Treatment

The patient received R-CHOP treatment (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone, and rituximab) in 8 cycles throughout 12 months. Two sessions of radiotherapy were also implemented.

2.3. Outcome and follow-up

In this case report, the patient showed a good response to treatment with mild side effects. After 6 months, the lesion decreased in size to 7 cm × 5 cm (Fig. 1b). After 24 months of follow-up, the patient remained asymptomatic. However, imaging studies have shown the persistence of a small calcified lesion of 3 cm × 1.5 cm (Fig. 1c). The patient has been regularly seen in an outpatient facility.

3. Discussion

This case highlights several important points. Although rare, it is important to recognize PHL because it responds favorably to chemotherapy and may have a better prognosis than hepatocellular carcinoma or metastatic disease of the liver. The differential diagnosis should include primary hepatomas and metastatic neoplasms. When imaging findings on CT scans and MRI are nonspecific, a biopsy is needed not only for a definitive diagnosis but also for identifying the immunophenotype of the PHL. This type of lesion is highly chemosensitive and early aggressive chemotherapy may result in sustained remission.4

PHL is more frequent in men and the usual age at presentation is around 50 years. Presentations vary from the incidental discovery of hepatic abnormalities in asymptomatic patients to onset of fulminant hepatic failure with rapid progression of encephalopathy to coma and death. Symptoms are usually nonspecific, and include right upper quadrant and epigastric pain, fatigue, weight loss, fever, anorexia, and nausea. Hepatomegaly is very common, and jaundice may be found on physical examination.5

PHL can be subdivided into nodular or diffuse types according to the presence of liver infiltration. Most PHL corresponds to a larger cell type and demonstrates a B-cell immunophenotype. Other histologic subtypes of PHL include high-grade tumors (lymphoblastic and Burkett lymphoma, 17%), follicular lymphoma (4%), diffuse histiocytic lymphoma (5%), lymphoma of the mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue type, anaplastic large-cell lymphoma, mantle cell lymphoma, and T- cell-rich B-cell lymphoma.5

The diagnosis of PHL still remains a challenge. The misdiagnosis is common and many times is made on histology of the surgical specimen. Because of the presence of a large area of necrosis, the fine needle tumor biopsy is frequently negative. In the present case, we achieved the final diagnosis after two previous negative biopsies. During the procedure one should be careful to guide the needle toward an area without necrosis in order to get a representative sample of the tumor. We remark that patients with PHL typically have abnormal liver function tests, with elevation of LDH and ALP. Elevated LDH, with normal AFP and CEA, remains a valuable biologic feature,5 as we have found in our patient.

On ultrasound, PHL lesions are hypoechoic comparing to normal liver. Imaging by CT shows hypoattenuating lesions and MRI enhancement after contrast. Findings on MRI are variable; however, a few authors have described hypointense T1-weighted images and hyperintense T2-weighted images.2–7

For PHL diagnosis, tumor must be confined to liver, without involvement of spleen, lymph nodes, bone marrow, or other lymphoid structures.5 Most patients are treated with chemotherapy, with some physicians employing a multimodality approach that also incorporates surgery and radiotherapy.2,5 The standard treatment for patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma is CHOP. The addition of rituximab, a chimeric monoclonal antibody, to the CHOP regimen, augments the complete response rate and prolongs event free and overall survival in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, without a clinically significant increase in toxicity.4–8

Poor prognostic features include advanced age, constitutional symptoms, bulky disease, unfavorable histologic subtype, elevated levels of LDH and a high proliferation rate, cirrhosis, and comorbid conditions.6–8

4. Conclusion

PHL should be considered as a diagnosis in cases of space occupying liver lesions with normal levels of AFP and CEA. If the clinical picture is suspicious for PHL, a liver biopsy should be obtained. PHL is treatable and overall survival has improved for these patients with new therapeutic drugs such as rituximab.

Conflict of interest

None.

Funding

None.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Author contributions

All authors contributed equally in this case report.

Footnotes

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike License, which permits non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

References

- 1.Gatselis N.K., Dalekos G.N. Hepatobiliary and pancreatic: primary hepatic lymphoma. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;26:210. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2010.06555.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yang X., Tan W., Yu W. Diagnosis and surgical treatment of primary hepatic lymphoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:6016–6019. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i47.6016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Miyashita K., Tomita N., Oshiro H. Primary hepatic peripheral T-cell lymphoma treated with corticosteroid. Intern Med. 2011;50:617–620. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.50.4686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Serrano-Navarro I., Rodríguez-López J.F., Navas-Espejo R. Primary hepatic lymphoma-favorable outcome with chemotherapy plus rituximab. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2008;100:724–728. doi: 10.4321/s1130-01082008001100011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Masood A., Kairouz S., Hudhud k.H. Primary non-Hodgkin lymphoma of liver. Curr Oncol. 2009;16:74–77. doi: 10.3747/co.v16i4.443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ma Y., Chen E., Chen X. Primary hepatic diffuse large B cell lymphoma: a case report. Hepat Mon. 2011;11:203–205. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gomyo H., Kagami Y., Kato H. Primary hepatic follicular lymphoma: a case report and discussion of chemotherapy and favorable outcomes. J Clin Exp Hematopathol. 2007;47:73–77. doi: 10.3960/jslrt.47.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Doi H., Horiike N., Hiraoka A. Primary hepatic marginal zone B cell lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue type: case report and review of the literature. Int J Hematol. 2008;88:418–423. doi: 10.1007/s12185-008-0153-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]