Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Endometrial stromal sarcomas are rare mesenchymal neoplasms of the uterus with an indolent clinical course but a high risk of recurrence.

PRESENTATION OF CASE

We report a case of a 78 year old woman who presented with rectal bleeding and recurrent urinary tract infections, caused by a very late recurrence of a formerly misdiagnosed low grade endometrial stromal sarcoma, metastasized to the colon.

DISCUSSION

Endometrial stromal sarcomas are difficult to diagnose, both due to the rarity of the tumor and because of the close resemblance of the tumor to normal stromal tissue. These tumors are known for a high tendency of recurrence, therefore long term follow up is required in patients with endometrial stromal sarcoma.

CONCLUSION

In patients with a history known for endometrial stromal sarcoma recurrence should always be considered.

Keywords: Endometrial stromal sarcoma, Mesenchymal tumor, Uterine malignancy, Recurrence

1. Introduction

Endometrial stromal sarcomas (ESS) are uncommon mesenchymal tumors of the uterus which are composed of cells closely resembling normal proliferative endometrial stromal tissue.1 Traditionally, ESS were classified into low-grade and high-grade ESS based on mitotic rate. High-grade tumors however, have little resemblance to original endometrial stroma. Therefore, high-grade tumors are presently classified as undifferentiated endometrial or uterine sarcoma. In this classification the differentiation between low-grade and undifferentiated tumors is not made on mitotic count but on the presence of nuclear pleomorphism and necrosis.1 Standard treatment for ESS is total abdominal hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy. When there is extra-uterine spread complete debulking of all tumor is recommended.2 The value of adjuvant therapy is still controversial.

In this paper we present a patient presenting with rectal bleeding, based on a very late recurrence of a formerly misdiagnosed low grade ESS metastasized to the colon. We focus on pitfalls in the diagnosis.

2. Presentation of a case

A 78 year old woman presented with rectal bleeding and recurrent lower urinary tract infections in July 2009. Her medical history showed a total abdominal hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy because of a uterus myomatosus with severe blood loss in 1983 and a laparotomy with excision of a retroperitoneal cyst in 1992. Pathological examination of the cyst showed a malignant mesenchymal tumor.

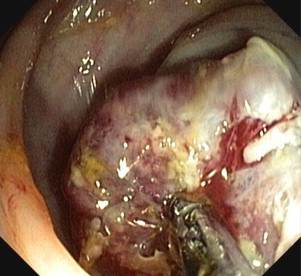

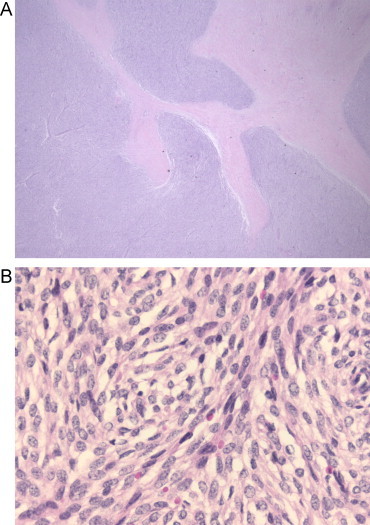

Our patient underwent a colonoscopy which revealed a malignant circumferential obstructing tumor 28 cm from the anal verge (Fig. 1). Histopathologic biopsies however, could not prove a malignant origin. Computed tomography showed a suspicious tumor of 8 cm, at the site of the sigmoid, closely related to the urinary bladder. Urine analysis revealed some atypical cells, but no signs for urinary tract infection or malignant cells. Metastatic work-up showed no signs of distant metastasis. Surgical resection was achieved. Intraoperatively, a large tumoral process invading the urinary bladder was discovered. A Hartmann's resection was performed with a partial cystectomy which was closed primarily and the patient received a urinary catheter for one week. One month postoperative she underwent intraperitoneal stomal revision, because of a retracted necrotizing colostomy. Further recovery was uneventful. Pathologic examination showed a submucosal low grade ESS of 8 cm in diameter arising from the colon with nodular invasion of the mesocolon and three lymph nodes which all contained metastases of ESS (Figs. 2 and 3). Resection margins were free from tumor.

Fig. 1.

Colonoscopy: stenosing tumor 28 cm from the anal verge.

Fig. 2.

Gross pathology of the opened sigmoid colon with the tumor in the center without ulceration or erosion.

Fig. 3.

(A) Submucosal low-grade ESS. Pathologic analysis after rectosigmoid resection 2009. HE, 12.5×. Tongues of small blue cells are permeating the muscularis propria. (B). HE, 200×. A diffuse proliferation of spindle cells with little atypia.

In the context of this finding revision of the original resections of the retroperitoneal cyst and the uterus and adnexa was performed. This revision revealed, both histomorphological as well as immunophenotypical, an equivalent aspect as the newly resected colon tumor.

Final pathologic diagnosis therefore, was a very late colonic recurrence of a low grade uterine ESS.

3. Discussion

Endometrial stromal sarcomas are rare tumors, contributing for 0.2% of all uterine malignancies and 7–15% of all uterine sarcomas.3 Initially, histological classification consisted of carcinosarcomas (40%), leiomyosarcomas (40%), ESS (15%) and undifferentiated sarcomas (5%). Currently, the carcinosarcomas have been reclassified as a differentiated or metaplastic form of endometrial carcinoma according to the International Federation of Gynaecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) classification.1

ESS are difficult to diagnose because of close resemblance to normal proliferative endometrial cells, and because of the rarity of the condition. Prior to surgical resection ESS are often misdiagnosed as leiomyoma or other uterine benign diseases and after resection also histological examination frequently misses the diagnosis.2

Incidence peaks occur in premenopausal women between 40 and 55 years of age who are asymptomatic or present with vaginal bleeding or pelvic or abdominal pain. ESS can occur in patients with endometriosis and in patients with a prolonged exposure to estrogens, e.g. patients with polycystic ovarian disease, or after estrogen use or tamoxifen therapy.1,4 It is thought that the exposure to estrogens causes a proliferative effect on the endometrial stroma.

Stage is an important predictor of overall survival in these tumors. Patients with stage I–II tumors have a 5-year overall survival of 89.3% compared to 50.3% in patients with stage III–IV tumors.4 Eventually 15–25% of all patients will die of their disease.3

3.1. Recurrence

Recurrences in low-grade ESS are common, even in early stage disease. Tumor behaviour is apprehensive for a tendency of late recurrence. In patients with stage I disease, the median time to recurrence is 65 months compared to 9 months in patients with stage III–IV ESS, therefore, long term follow-up is recommended.4

Recurrences occur in 36–56% of patients, most frequently in the pelvic cavity or the lungs.4,5 Metastatic spread to the cerebrum and bones and invasion in the great vessels have also been described.6,7 Recurrences in the abdominal cavity are rare. Recurrences arising in the small bowel and colon are intimately associated with endometriosis.8 As the rectosigmoid has the highest incidence of intestinal endometriosis, ESS arising within endometriosis are most often diagnosed in the rectosigmoid.8 Our patient developed a very late recurrence in the rectosigmoid, although she had no history of endometriosis. Pathologic revision did not reveal any signs of endometriosis, but the presence of a small endometriosis spot as an origin for the metastasis cannot be excluded.

3.2. Treatment

Standard treatment for ESS is total abdominal hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, even at premenopausal ages. The importance of comprehensive surgical staging remains debatable.3

Low grade endometrial sarcomas are usually characterized by estrogen and progesterone receptors.9 They are often sensitive to hormones and it is presumed that patients preserving their ovaries have a higher risk of recurrence and poorer overall outcome.2,10 Some studies advocate considering re-exploration for removal of ovaries6 while others state that ovarian preservation has no effect on recurrences or overall survival.5,9 In premenopausal women ovaries are frequently preserved, which does not affect the risk of recurrence in stage I patients.2,5

Lymph node metastases have been found in 7% of patients with low-grade ESS. Performing a lymph node dissection, regardless of the finding of any microscopic positive nodes, does not have an effect on overall survival in low-grade ESS. Five-year survival is 85.7% in lymph node positive patients compared to 95.2% in lymph node negative patients.9

Adjuvant therapy following surgery can include radiotherapy, chemotherapy and hormonal therapy. The value of adjuvant therapy in low-grade ESS is still controversial.2,3 Post-operative radiotherapy decreases the risk of local recurrence, especially in grade II–IV disease, without having a significant effect on overall survival.2 Radiotherapy can also be given as palliation. Little is known about adjuvant chemotherapy, so no definitive recommendations exist. Postoperative treatment with chemotherapy could might be an option in patients with hormone-unresponsive tumors and for inoperable patients.

Hormonal therapy can be an important treatment because of the hormonal sensitivity of the tumor. Adjuvant progestagens should be considered in patients with ESS. In patients with completely resected low-grade ESS it may produce prolonged complete response.5 Tamoxifen and estrogens are contraindicated because of the possible stimulative effect on disseminated endometrial stromal cells.2,5

Our patient underwent a hysterectomy in 1983 because of a uterus myomatosus accompanied with severe blood loss and excision of a retroperitoneal cyst in 1992. Retrospective pathologic revision revealed ESS in both cases. That means our patient probably had stage I ESS in 1983, which was initially not recognized as ESS, but was probably regarded as a cell rich variant of leiomyoma. After nine years she developed the first retroperitoneal recurrence. At this time the tumor was detected as a malignant mesenchymal tumor, but was not recognized as ESS. Seventeen years later she developed a second recurrence with a rare presentation. A recurrent ESS localized in the submucosa of the colon, in the absence of endometriosis, with fixation to the urinary bladder is a very rare finding.8 The accompanying lymphogenic spread is uncommon. During the first surgery, at 52 years of age, our patient underwent a hysterectomy for a uterus myomatosus with bilateral oophorectomy. She never took hormonal replacement therapy except for local estrogens for a few weeks and she was not familiar with endometriosis. Prior to her third surgery in 2009, she was diagnosed with recurrent lower urinary tract infections. Urine analysis revealed some atypical cells, presumably due to tumor invasion in the urinary bladder. Final pathologic examination of the operatively removed tumor however, could not confirm spread of tumor into the bladder wall, since no urinary bladder wall was recognized in the specimen. Patient was discussed in our multidisciplinary oncology panel and because of the controversy about adjuvant therapy in the treatment of ESS, in combination with the radical surgery and the long disease free period after the primary presentation and the first recurrence, no additional treatment was advised and follow up will take place on a regular base once a year. Three years later the patient has no evidence of disease.

4. Conclusion

In conclusion, low-grade ESS are uncommon tumors of the uterus with an indolent clinical course and favourable prognosis. Total abdominal hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy is the treatment of choice. In patients with a history known for ESS, a recurrence should always be considered, despite a very long disease-free interval. If recurrence occurs, radical surgery should be performed and adjuvant hormonal therapy may be considered.

Conflict of interest

There are no conflicts of interest to report. There was no financial support for the conduct of the study and the writing of the manuscript.

Funding

None.

Ethical approval

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal on request.

Furthermore, patient information is anonymous and not traceable to the patient.

Author contributions

Study concept: I.B., M.H. Study design: I.B., M.H., F.M., H.H. Data collection: I.B., M.H. Writing: I.B., M.H. Manuscript editing: I.B., M.H., F.M., H.H. Manuscript review: I.B., M.H., F.M., H.H.

Footnotes

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike License, which permits non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

References

- 1.Hendrickson M.R., Tavasoli F.A., Kempson R.L., McCluggage W.G., Haller U., Kubik-Huch R.A. Mesenchymal tumours and related lesions. In: World Health Organization classification of tumours, editor. Pathology and genetics of tumours of the breast and femal genital organs. IARC Press; Lyon, France: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li N., Wu L.Y., Zhang H.T., An J.S., Li X.G., Ma S.K. Treatment options in stage I endometrial stromal sarcoma: a retrospective analysis of 53 cases. Gynecol Oncol. 2008;108(February (2)):306–311. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2007.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gadducci A., Sartori E., Landoni F., Zola P., Maggino T., Urgesi A. Endometrial stromal sarcoma: analysis of treatment failures and survival. Gynecol Oncol. 1996;63(November (2)):247–253. doi: 10.1006/gyno.1996.0314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chang K.L., Crabtree G.S., Lim-Tan S.K., Kempson R.L., Hendrickson M.R. Primary uterine endometrial stromal neoplasms. A clinicopathologic study of 117 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1990;14(May (5)):415–438. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199005000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chu M.C., Mor G., Lim C., Zheng W., Parkash V., Schwartz P.E. Low-grade endometrial stromal sarcoma: hormonal aspects. Gynecol Oncol. 2003;90(July (1)):170–176. doi: 10.1016/s0090-8258(03)00258-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goff B.A., Rice L.W., Fleischhacker D., Muntz H.G., Falkenberry S.S., Nikrui N. Uterine leiomyosarcoma and endometrial stromal sarcoma: lymph node metastases and sites of recurrence. Gynecol Oncol. 1993;50(July (1)):105–109. doi: 10.1006/gyno.1993.1172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Renzulli P., Weimann R., Barras J.P., Carrel T.P., Candinas D. Low-grade endometrial stromal sarcoma with inferior vena cava tumor thrombus and intracardiac extension: radical resection may improve recurrence free survival. Surg Oncol. 2009;18(March (1)):57–64. doi: 10.1016/j.suronc.2008.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chang K.L., Crabtree G.S., Lim-Tan S.K., Kempson R.L., Hendrickson M.R. Primary extrauterine endometrial stromal neoplasms: a clinicopathologic study of 20 cases and a review of the literature. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 1993;12(October (4)):282–296. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shah J.P., Bryant C.S., Kumar S., Ali-Fehmi R., Malone J.M., Jr., Morris R.T. Lymphadenectomy and ovarian preservation in low-grade endometrial stromal sarcoma. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112(November (5)):1102–1108. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31818aa89a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sagae S., Yamashita K., Ishioka S., Nishioka Y., Terasawa K., Mori M. Preoperative diagnosis and treatment results in 106 patients with uterine sarcoma in Hokkaido, Japan. Oncology. 2004;67(1):33–39. doi: 10.1159/000080283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]