Abstract

This study compared the effects of external hex, internal octagon, and internal Morse taper implant–abutment connections on the peri-implant bone level before and after the occlusal loading of dental implants. Periapical radiographs of 103 implants (63 patients) placed between 2002 and 2010 were collected, digitized, standardized, and classified into groups based on the type of implant–abutment connection. These radiographs were then analyzed with image-processing software to measure the peri-implant crestal bone change during the healing phase (4 months after implant placement) and at loading phases 1 and 2 (3 and 6 months after occlusal loading, respectively). A generalized estimating equation method was employed for statistical analysis. The amount of peri-implant crestal bone change differed significantly among all time–phase pairs for all 3 types of implant–abutment connection, being greater in the healing phase than in loading phase 1 or 2. However, the peri-implant crestal bone change did not differ significantly among the 3 types of implant–abutment connections during the healing phase, loading phase 1, or loading phase 2. This retrospective clinical study reveals that the design of the implant–abutment connection appears to have no significant impact on short-term peri-implant crestal bone change.

Keywords: internal octagon, internal Morse taper, peri-implant crestal bone change dental implant–abutment design, radiology, alveolar bone loss

Introduction

Dental implants have been widely accepted as a predictable and reliable tool for dental reconstruction, but it is still necessary to ensure that the height of the peri-implant crestal bone is maintained (Buser et al., 2002). Albrektsson et al. (1986) proposed that a dental implant can be considered successful if peri-implant crestal bone loss is less than 1.5 mm during the first year after implant placement and less than 0.2 mm annually thereafter.

The type of implant–abutment connection (Quirynen et al., 1992; Koo et al., 2011) has been considered to be one of the major factors (Quirynen et al., 1992; Malevez et al., 1996; Oh et al., 2002; Vidyasagar and Apse, 2004; Isidor et al., 2006; Abrahamsson and Berglundh, 2009; Koo et al., 2011) affecting peri-implant crestal bone change. Astrand et al. (2004) reported that bone change was greatest during the period following implant placement and before superstructures were constructed for patients who received either internal or external hex abutments. However, the volume of crestal bone lost was small between baseline and follow-ups at 1, 3, and 5 years and did not differ significantly between internal and external hex implants. Weng et al. (2008) conducted a histologic comparison of the degree of bone loss between the internal taper and external hex connections of implant systems with either epicrestal or subcrestal placement in animals. Peri-implant bone height at 3 months after abutment connection changed least for epicrestal placement of implants with an internal taper implant–abutment connection.

The literature (Maeda et al., 2006; Pessoa et al., 2010; Nishioka et al., 2011; Chu et al., 2012; Streckbein et al., 2012) indicates that the type of implant–abutment connection may influence the stresses and strains induced in peri-implant crestal bone. Nishioka et al. (2011) conducted in vitro experiments with implant bodies embedded in resin blocks using external hex, internal hex, and internal Morse taper systems. They found that peri-implant bone strain varied significantly with the type of implant–abutment connection. Finite element analyses predict that the stress distribution in peri-implant bone differs with the type of implant–abutment connection (Maeda et al., 2006; Pessoa et al., 2010). Chu et al. (2012) further demonstrated that either increasing the thickness of the inner wall of the implant body or decreasing the width of the implant–abutment connection reduces the stress in the peri-implant bone.

Only a few studies (Engquist et al., 2002; Astrand et al., 2004) have examined whether implant systems with external hex, internal hex, internal octagon, and internal Morse taper connections cause different degrees of peri-implant crestal bone change during (1) the healing phase before implants are subjected to bite forces and (2) the loading phases after prostheses are constructed and subjected to bite forces. Therefore, the aim of the present study was to determine if peri-implant crestal bone–level alterations at different time phases may depend on the type of implant–abutment connection. This study also examined peri-implant crestal bone changes between the healing phase and the loading phases (3 and 6 months).

Materials & Methods

This retrospective study analyzed periapical radiographs obtained from patients receiving dental implant treatment at the Department of Dentistry, China Medical University Hospital, from 2002 to 2010. This study was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the Institutional Review Board of the China Medical University Hospital (approval DMR101-IRB-1-078). Because the type of the superstructure (Sadowsky, 1997; Heckmann et al., 2001) and the diameter and length of the implants (Winkler et al., 2000; Petrie and Williams, 2005) could influence the load and stress/strain distributions of implants as well as the clinical outcomes, only the periapical radiographs of single implants and 2 implants splinted with a fixed dental prosthesis in the posterior region were selected in this study. The diameters and lengths of the implants were also limited to 4 to 5 mm and 10 to 12 mm, respectively. Implants that supported overdentures, implants with cantilevered fixed partial dentures, and the implants opposing removable partial or complete dentures were excluded. Additionally, cases with implant failure and severe bone loss due to peri-implantitis were excluded to avoid large error values.

All implants were placed at healed edentulous ridges at least 2 months after tooth extraction, and a standard healing protocol was followed (which lasted 4 and 6 months for the mandible and maxilla, respectively). The implants were embedded at the crestal bone level with cover screws to facilitate healing, followed by the connection of abutments 3 to 6 months thereafter. In our normal clinical protocol, successful osseointegration of dental implants would be confirmed by a Periotest value (Siemens, Bensheim, Germany) of less than +5 (on healing abutments; Cranin et al., 1998) and the presence of healthy gingival tissue before taking impressions. After the connection of impression copings, a periapical radiograph perpendicular to the occlusal plane was taken with a cone indicator (Cone Indicator III, Hanshin Technical Laboratory, Nishinomiya, Japan). These periapical radiographs were used to check that the impression copings had been seated completely; they also served as baseline data of the peri-implant crestal bone level. The impressions were made with a transfer technique 3 weeks after healing during the second stage, and the prosthesis was delivered at least 5 weeks after the second stage. The following 3 types of implant–abutment connections were selected: external hex (Brånemark System TMMK IV TiUnite, Nobel Biocare, Gothenburg, Sweden), internal octagon (Submerged Atlas, Cowellmedi, Busan, South Korea), and internal Morse taper (Ankylos Plus Implant, Friadent, Mannhein, Germany). All prostheses were cemented to the abutments, which were then connected in the delivery appointments. Detailed information about the implants and patients are given in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characterization of the Implant–Abutment Connections

| External Hex, n = 33 (%) | Internal Octagon, n = 33 (%) | Internal Morse Taper, n = 37 (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diameter, mm | |||

| 4 | 6 (18) | 17 (52) | 11 (30) |

| 5 | 26 (79) | 15 (45) | 23 (62) |

| 6 | 1 (3) | 1 (3) | 3 (8) |

| Length, mm | |||

| 10.0 | 12 (36) | 13 (39) | 11 (30) |

| 11.5 | 14 (43) | 19 (58) | 22 (59) |

| 13.0 | 7 (21) | 1 (3) | 4 (11) |

| Jaw | |||

| Maxilla | 17 (52) | 14 (42) | 12 (32) |

| Mandible | 16 (48) | 19 (58) | 25 (68) |

| Site | |||

| Premolar | 6 (18) | 12 (36) | 7 (19) |

| Molar | 27 (82) | 21 (64) | 30 (81) |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 15 (65) | 10 (45) | 10 (56) |

| Female | 8 (35) | 12 (55) | 8 (44) |

The time intervals for measurement were designated as T0, T1, T2, and T3, where T0 represents the day of implant placement; T1, the day when the prosthesis was delivered (after approximately 4 months of implant placement) and the start of occlusal loading; T2, approximately 3 months after the start of implant loading; and T3, 6 months after the start of implant loading. Any changes in the height of the peri-implant crestal bone were observed during the healing phase (i.e., T0-T1), loading phase 1 (i.e., T1-T2), and loading phase 2 (i.e., T1-T3). Such changes in the peri-implant bone level during the healing phases would indicate bone changes during the healing time of the implant. The changes in the peri-implant bone levels during loading phases 1 and 2 demonstrate bone changes that occurred approximately 3 and 6 months after occlusal loading, respectively.

To minimize errors, all the periapical radiographs were taken with a cone indicator (Cone Indicator III) with a standardized radiographing process performed by an experienced and well-trained technician, using size 2 films (Kodak Ultra-speed, Eastman Kodak, Rochester, NY, USA) that were kept parallel, with the X-ray beam (70 kV, 10 mA; PY-70C, Poo Yee X-ray, Taipei, Taiwan) perpendicular to the implant. Films were then developed with appropriate fresh chemical solutions in an automatic processor (DENT-X 810 basic, Dent-X Corporation, Elmsford, NY, USA). Standard radiographing protocols were followed at each recall visit (i.e., T0, T1, T2, and T3).

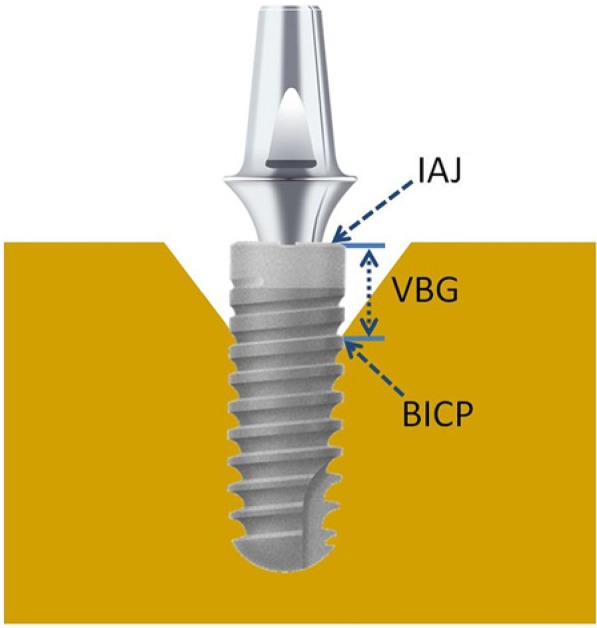

This study used a digital camera (D50, Nikon, Tokyo, Japan) with a 60-mm macro lens, f/11 aperture, and a 1/60-second shutter speed with professional copy-board positioning under a standard X-ray-viewing (5200 K) light source to reshoot and transform the X-ray films into images with 3008 × 2000 (width × height) pixels. After the images were digitized, ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA) was used to analyze and measure changes in the peri-implant bone height. The Figure shows the reference points for measurements. The bone–implant contact point was the first contact point between the bone and the implant. The vertical bone gap (VBG) was the vertical distance between the implant–abutment junction and the bone–implant contact point. Differences in the VBG measured at various times were used to quantify the changes in the peri-implant bone level (Appendix Table).

Figure.

The measurement reference points: the bone–implant contact point (BICP), the vertical bone gap (VBG), and the implant–abutment junction (IAJ).

SPSS 18 was used for statistical analyses. Linear regression models based on generalized estimating equations (GEEs; Zeger and Liang, 1986) were used to analyze the differences in the mean values of the mesial and distal peri-implant bone changes for the 3 implant–abutment connection types during the 3 time phases. This model considered the correlations of within-subject repeated measures. Robust sandwich estimators were used to compute standard errors, and an exchangeable working correlation matrix was used to model patients clustering within the 3 time phases for the GEEs. The Wald chi-square test was then used to determine whether the regression coefficient was zero; nonzero values indicated statistically significant differences in peri-implant crestal bone change between the various implant–abutment connection designs and time phases. The Bonferroni test was used for the post hoc test. A 2-tailed significance level of alpha = 0.05 was used for indicating the level of significance in all assessments involving the GEE or the Bonferroni test.

Results

In total, this study included 63 patients (35 men, 28 women; age, 47 ± 11 years) with 103 implants (Table 1). Table 2 lists the peri-implant crestal bone changes for the 3 implant–abutment connection types (external hex, internal octagon, and internal Morse taper) during the 3 time phases (healing phase, loading phase 1, and loading phase 2).

Table 2.

Peri-implant Bone Changes for the 3 Types of Implant–Abutment Connections During the 3 Time Phases

| Healing Phase | Loading Phase 1 | Loading Phase 2 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Connection | n | Mean ± SD, mm | n | Mean ± SD, mm | n | Mean ± SD, mm |

| External hex | 27 | –0.45 ± 0.19 | 22 | –0.21 ± 0.13 | 16 | –0.32 ± 0.19 |

| Internal octagon | 33 | –0.44 ± 0.15 | 29 | –0.18 ± 0.12 | 24 | –0.38 ± 0.22 |

| Internal Morse taper | 36 | –0.38 ± 0.14 | 25 | –0.19 ± 0.11 | 26 | –0.32 ± 0.14 |

This study used the GEE method to conduct an overall test to determine whether the changes in height of the peri-implant bone differed between any 2 groups comprising the 3 implant–abutment connection types and 3 time phases. The results indicated that there were no statistically significant differences among the different types of implant–abutment connections (p = .35) but that there were significant differences between the time phases (p < .001).

A Bonferroni post hoc test confirmed that the peri-implant crestal bone change did not differ significantly among the external hex, internal octagon, and internal Morse taper implant–abutment connections at each of the 3 time phases (p > .50; Table 3) but that it did differ significantly among the healing phase, loading phase 1, and loading phase 2 irrespective of the type of implant–abutment connection used (p < .001; Table 3).

Table 3.

Bonferroni post hoc Comparison of Differences in the Peri-implant Bone Changes for the 3 Types of Implant–Abutment Connections and the 3 Time Phases

| I: Connection | J: Connection | Mean Deviation (I – J) | SEM | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| External hex | Internal Morse taper | –0.03 | 0.03 | .896 |

| Internal octagon | External hex | –0.01 | 0.03 | > .999 |

| Internal octagon | Internal Morse taper | –0.04 | 0.03 | .506 |

| K: Phase | L: Phase | Mean Deviation (K – L) | ||

| Healing phase | Loading phase 1 | –0.22 | 0.02 | < .001 |

| Healing phase | Loading phase 2 | –0.07 | 0.02 | < .001 |

| Loading phase 1 | Loading phase 2 | 0.14 | 0.02 | < .001 |

Discussion

Three common commercially available implants with different types of implant–abutment connections (external hex, internal octagon, and internal Morse taper systems) were studied for their effects on the peri-implant crestal bone change during the first year after implantation. The mean changes of the peri-implant crestal bone were less than 1 mm in the first year for all implants. Crestal bone changes that occurred between the placement of implants and 6 months after loading were all well within the success criteria proposed by Albrektsson et al. (1986; i.e., bone loss < 1.5 mm in the first year).

Crestal bone change did not differ significantly among the types of implant–abutment connections, but it was slightly greater—60% for external hex and 52% for both internal octagon and internal Morse taper—during the healing phase (before occlusal loading) than during loading phases 1 and 2 (3 and 6 months after occlusal loading, respectively). These findings are similar to those of Enkling and colleagues (2011), who found that peri-implant crestal bone change was slightly greater during the healing phase than after the implants were loaded. Several factors could hypothetically induce changes in crestal bone, including surgical trauma, occlusal overload, peri-implantitis, the microgap, the biological width, and the implant crest module used (Oh et al., 2002). The factor tested in the current study was the connection of the healing abutment in the second stage. Changes in crestal bone before occlusal loading are most likely to result from surgical trauma to the bone surrounding the implant when a heading abutment is connected in the second stage of surgery. It is well recognized that crestal bone resorption during the first year should be less than 1.5 mm (Albrektsson et al., 1986), and the current study supports this.

The biological width was significantly greater for 2-piece implants than for 1-piece implants in the study of Hermann et al. (2001), and this was attributed to the existence of an microgap (interface) at or below the crest of the bone. Lazzara and Porter (2006) reported that a concept of platform switching could bring the inflammatory cells infiltration, which would reduce the peri-implant crestal bone change. Subsequent studies have supported the advantages of platform-switching designs (Pontes et al., 2008). However, our study and those of others (Veis et al., 2010; Baffone et al., 2011) found that a platform-switching design did not affect the peri-implant crestal bone level; in fact, a greater peri-implant crestal bone change was found in the healing phase. This finding was in accordance with Enkling and colleagues’ (2011) finding that time—rather than platform switching—was the primary factor affecting the peri-implant bone height in human subjects.

One of the limitations of the present study was the small sample size, which was due to the application of the strict inclusion criteria of implant-retained single or splinted crowns and to implant diameter and length falling within the ranges of 4 to 5 mm and 10 to 12 mm, respectively. Future studies should increase the number of samples and extend the follow-up period. Even though a standardized radiographing procedure was applied in the present study to minimize errors in the obtained periapical radiographs, individual custom-made holders were not used throughout the study. Additionally, the effect of the biological width between implant and abutment on the surrounding bone level was not examined. Some researchers have indicated that peri-implant bone level can be influenced by the biological width and that this dimension varies with the implant design (Hermann et al., 2001; Linkevicius and Apse, 2008). Future investigations should perform randomized controlled clinical trials with custom-made perpendicular holders and test the effects of connection type between implant and abutment on peri-implant bone level to determine if the biological width around implants exerts significant effects on bone change.

Conclusions

Within the limitations of this study, the following conclusions can be drawn: First, the level of peri-implant crestal bone does not differ significantly during either the healing phase or the loading phases among 3 different implant–abutment connection designs (external hex, internal octagon, and internal Morse taper). Second, the level of peri-implant crestal bone changes significantly with the time interval (healing phase, loading phase 1, and loading phase 2), with it being slightly greater before the application of occlusal loading.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Professors Yuh-Yuan Shiau and Che-Shoa Chang for their suggestions in this study and Chou Tse-Chih at the Clinical Informatics and Medical Statistics Research Center of Chang Gung University for his assistance with statistical analysis.

Footnotes

This research was supported by China Medical University Hospital (grant DMR-101-022) and the National Science Council of Taiwan (grant NSC 101-2314-B-039-022-MY3).

The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the authorship and/or publication of this article.

A supplemental appendix to this article is published electronically only at http://jdr.sagepub.com/supplemental.

References

- Abrahamsson I, Berglundh T. (2009). Effects of different impalnt surfaces and designs on marginal bone-level alternations: a review. Clin Oral Implants Res 20(Suppl 4):207-215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albrektsson T, Zarb G, Worthington P, Eriksson AR. (1986). The long-term efficacy of currently used dental implants: a review and proposed criteria of success. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants 1:11-25 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Astrand P, Engquist B, Dahlgren S, Gröndahl K, Engquist E, Feldmann H. (2004). Astra Tech and Brånemark system implants: a 5-year prospective study of marginal bone reactions. Clin Oral Implants Res 15:413-420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baffone GM, Botticelli D, Pantani F, Cardoso LC, Schweikert MT, Lang NP. (2011). Influence of various implant platform configurations on peri-implant tissue dimensions: an experimental study in dog. Clin Oral Implants Res 22:438-444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buser D, Ingimarsson S, Dula K, Lussi A, Hirt HP, Belser UC. (2002). Long-term stability of osseointegrated implants in augmented bone: a 5-year prospective study in partially edentulous patients. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent 22:109-117 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu CM, Huang HL, Hsu JT, Fuh LJ. (2012). Influences of internal tapered abutment designs on bone stresses around a dental implant: three-dimensional finite element method with statistical evaluation. J Periodontol 83:111-118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cranin AN, DeGrado J, Kaufman M, Baraoidan M, DiGregorio R, Batgitis G, et al. (1998). Evaluation of the Periotest as a diagnostic tool for dental implants. J Oral Implantol 24:139-146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engquist B, Astrand P, Dahlgren S, Engquist E, Feldmann H, Gröndahl K. (2002). Marginal bone reaction to oral implants: a prospective comparative study of Astra Tech and Brånemark System implants. Clin Oral Implants Res 13:30-37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enkling N, Johren P, Klimberg V, Bayer S, Mericske-Stern R, Jepsen S. (2011). Effect of platform switching on peri-implant bone levels: a randomized clinical trial. Clin Oral Implants Res 22:1185-1192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heckmann SM, Winter W, Meyer M, Weber HP, Wichmann MG. (2001). Overdenture attachment selection and the loading of implant and denture-bearing area: part 2. A methodical study using five types of attachment. Clin Oral Implants Res 12:640-647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermann JS, Buser D, Schenk RK, Schoolfield JD, Cochran DL. (2001). Biologic width around one- and two-piece titanium implants. Clin Oral Implants Res 12:559-571 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isidor F. (2006). Influence of forces on peri-implant bone. Clin Oral Implants Res 17(Suppl 2):8-18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koo KT, Lee EJ, Kim JY, Seol YJ, Han JS, Kim TI, et al. (2011). The effect of internal versus external abutment connection modes on crestal bone changes around dental implants: a radiographic analysis. J Periodontol 83:1104-1109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazzara RJ, Porter SS. (2006). Platform switching: a new concept in implant dentistry for controlling postrestorative crestal bone levels. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent 26:9-17 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linkevicius T, Apse P. (2008). Biologic width around implants: an evidence-based review. Stomatologija 10:27-35 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeda Y, Satoh T, Sogo M. (2006). In vitro differences of stress concentrations for internal and external hex implant-abutment connections: a short communication. J Oral Rehabil 33:75-78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malevez C, Hermans M, Daelemans P. (1996). Marginal bone levels at Branemark system implants used for single tooth restoration: the influence of implant design and anatomical region. Clin Oral Implants Res 7:162-169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishioka RS, de Vasconcellos LG, de Melo Nishioka GN. (2011). Comparative strain gauge analysis of external and internal hexagon, Morse taper, and influence of straight and offset implant configuration. Implant Dent 20:e24-e32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh TJ, Yoon J, Misch CE, Wang HL. (2002). The causes of early implant bone loss: myth or science? J Periodontol 73:322-333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pessoa RS, Muraru L, Júnior EM, Vaz LG, Sloten JV, Duyck J, et al. (2010). Influence of implant connection type on the biomechanical environment of immediately placed implants: CT-based nonlinear, three-dimensional finite element analysis. Clin Implant Dent Relat Res 12:219-234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrie CS, Williams JL. (2005). Comparative evaluation of implant designs: influence of diameter, length, and taper on strains in the alveolar crest. A three-dimensional finite-element analysis. Clin Oral Implants Res 16:486-494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pontes AE, Ribeiro FS, Iezzi G, Piattelli A, Cirelli JA, Marcantonio E., Jr. (2008). Biologic width changes around loaded implants inserted in different levels in relation to crestal bone: histometric evaluation in canine mandible. Clin Oral Impl Res 19:483-490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quirynen M, Naert I, van Steenberghe D. (1992). Fixture design and overload influence marginal bone loss and fixture success in the Branemark system. Clin Oral Implants Res 3:104-111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadowsky SJ. (1997). The implant-supported prosthesis for the edentulous arch: design considerations. J Prosthet Dent 78:28-33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Streckbein P, Streckbein RG, Wilbrand JF, Malik CY, Schaaf H, Howaldt HP, et al. (2012). Non-linear 3D evaluation of different oral implant-abutment connections. J Dent Res 91:1184-1189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veis A, Parissis N, Tsirlis A, Papadeli C, Marinis G, Zogakis A. (2010). Evaluation of peri-implant marginal bone loss using modified abutment connections at various crestal level placements. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent 30: 609-617 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vidyasagar L, Apse P. (2004). Dental implant design and biological effects on bone-implant interface. Baltic Dent Maxillofac J 6:51-54 [Google Scholar]

- Weng D, Nagata MJ, Bell M, Bosco AF, de Melo LG, Richter EJ. (2008). Influence of microgap location and configuration on the periimplant bone morphology in submerged implants: an experimental study in dogs. Clin Oral Implants Res 19:1141-1147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winkler S, Morris HF, Ochi S. (2000). Implant survival to 36 months as related to length and diameter. Ann Periodontol 5: 22-31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeger SL, Liang KY. (1986). Longitudinal data analysis for discrete and continuous outcomes. Biometrics 42:121-130 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]