Abstract

Importance

In a multi-payer system, new payment incentives implemented by one insurer for an accountable care organization (ACO) may affect spending and quality of care for another insurer’s enrollees served by the ACO. Such “spillover” effects reflect the extent of organizational efforts to reform care delivery and can contribute to the total impact of ACOs.

Objective

We examined whether the Blue Cross Blue Shield (BCBS) of Massachusetts’ Alternative Quality Contract (AQC), an early commercial ACO initiative associated with reduced spending and improved quality for BCBS enrollees, was also associated with changes in spending and quality for Medicare beneficiaries, who were not covered by the AQC.

Design and Exposure

Quasi-experimental comparisons from 2007–2010 of Medicare beneficiaries served by 11 provider organizations entering the AQC in 2009 or 2010 (intervention group) vs. beneficiaries served by other providers (control group). Using a difference-in-differences approach, we estimated changes in spending and quality for the intervention group in the first and second years of exposure to the AQC relative to concurrent changes for the control group. Regression and propensity-score methods were used to adjust for differences in sociodemographic and clinical characteristics.

Participants and Setting

Elderly fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries in Massachusetts (1,761,325 person-years).

Main Outcome Measures

The primary outcome was total quarterly medical spending per beneficiary. Secondary outcomes included spending by setting and type of service, 5 process measures of quality, potentially avoidable hospitalizations, and 30-day readmissions.

Results

Before entering the AQC, total quarterly spending for the intervention group was $150 (95% CI, $25–$274) higher than for the control group and rose at a similar rate. In year 2 of the intervention group’s exposure to the AQC, this difference was reduced to $51 (95% CI, −$109–$210; P=0.53), constituting a significant differential change of −$99 (95% CI, −$183–−$16; P=0.02) or a 3.4% savings. Savings in year 1 were not significant (differential change: −$34; 95% CI, −$83–$16; P=0.18). Year-2 savings derived largely from lower spending on outpatient care (differential change: −$73; 95% CI, −$95–−$50; P<0.001), particularly for beneficiaries with ≥5 conditions, and included significant differential changes in spending on procedures, imaging, and tests. Annual rates of LDL testing differentially improved for beneficiaries with diabetes in the intervention group by 3.1 percentage points (95% CI, 1.4–4.8; P<0.001) and for those with cardiovascular disease by 2.5 percentage points (95% CI, 1.1–4.0; P<0.001), but performance on other quality measures did not differentially change.

Conclusions and Relevance

The AQC was associated with lower spending for Medicare beneficiaries but not with consistently improved quality. Savings among Medicare beneficiaries and previously demonstrated savings among BCBS enrollees varied similarly across settings, services, and time, suggesting organizational responses associated with broad changes in patient care.

Keywords: delivery of health care, accountable care organizations, Medicare, health care costs, quality of health care, aged

In response to mounting pressures to deliver more cost-effective care, provider organizations have exhibited increasing willingness to assume financial risk for the quality and costs of care they provide. Over 250 provider groups have contracted with Medicare as accountable care organizations (ACOs), and many similar payment arrangements have been reached with commercial insurers by these and other groups.1–4

In a multi-payer system where fee-for-service remains the predominant basis for reimbursement,5 new incentives to lower spending and improve quality typically do not apply to all of an organization’s patients. Efforts to reduce utilization among subsets of patients covered by risk contracts could have similar effects among other patients if such efforts extend beyond targeted case management to include broader changes that influence care for all patients. Conversely, lowering utilization among some patients could induce utilization among others by generating excess capacity, particularly for services in high demand or of uncertain clinical value.6,7 In addition, physicians seeking target incomes might respond to income effects from changes in one payer’s payments by altering the volume of services reimbursed by other payers.8

The size and direction of such “spillover” effects of ACO contracts are important to characterize because they indicate the extent of organizational change elicited by ACO payment incentives, contribute to the net impact of ACOs, and could influence decisions by insurers and provider groups to enter or expand ACO contracts. Because evaluations of recent initiatives by insurers to set global budgets for provider groups have been limited to the patient populations placed under budgets,9–12 the potential spillover effects of ACO contracts remain unclear.

Beginning in 2009, the implementation of the Alternative Quality Contract (AQC) by Blue Cross Blue Shield (BCBS) of Massachusetts heralded a marked but partial shift away from fee-for-service incentives for participating provider organizations.13 Under the terms of the AQC, provider organizations bear financial risk for spending in excess of a global budget, gain from reducing spending below the budget, and receive bonuses for meeting performance targets on quality measures. The incentives in the AQC are similar to those in two-sided payment arrangements that all ACOs in Medicare programs are expected to accept by their second contract period if not sooner.14,15 The AQC was associated with lower spending and improved quality of care for BCBS commercial HMO enrollees served by participating provider groups.10,11 Savings grew in the second year of group participation and were concentrated in the outpatient care of medically complex patients, particularly imaging, procedures, and tests. We examined changes associated with the AQC in spending and quality of care for traditional fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries.

METHODS

Data Sources

We analyzed data from Medicare enrollment and claims files from 2007 to 2010 for all beneficiaries residing in Massachusetts. Claims data were linked via National Provider Identifiers (NPIs) to data on provider groups from the American Medical Association (AMA) Group Practice File (Appendix).16,17 For physicians practicing in groups of ≥3, the AMA Group Practice File identifies their practice site(s) and parent organization if part of a larger group. Of primary care physicians (PCPs) practicing in groups of 3 or more and serving Medicare beneficiaries in Massachusetts in 2009, 94% were linked to the Group Practice File (Appendix).

Study Population and Design

For each year, our study population included beneficiaries who were continuously enrolled in Parts A and B of traditional fee-for-service Medicare while alive and received at least 1 primary care service during the year (N=1,983,921 person-years). We further restricted the study population to those who were age 66 or older in 2007 (N=1,761,325 person-years) to ensure at least 1 year of eligibility for assessing the presence of chronic conditions at baseline from the Chronic Condition Warehouse (CCW).18 Thus, the study population was comprised of a cohort of elderly adults enrolled in Medicare at baseline but not necessarily included in all study years because of death or Medicare Advantage enrollment. We adjusted our main analyses for conditions present at baseline, rather than in each study year, to avoid potential bias from more intensive diagnostic coding by organizations participating in the AQC in response to risk-adjusted global budgets.9–11,19

We conducted quasi-experimental comparisons of beneficiaries served by the 7 provider organizations entering the AQC in 2009 and the 4 entering in 2010 (hereafter called AQC participants) with beneficiaries served by other non-participating providers in Massachusetts, before and after AQC payment incentives were implemented for participating organizations.13 Following the Medicare Shared Savings Program assignment rules,14 we attributed each beneficiary in each year to the provider group accounting for the most allowed charges for primary care services among all groups providing primary care to the beneficiary in that year (Appendix).

We used 2 complementary sources of provider group identifiers when applying the attribution rules: 1) AMA Group Practice File groupings of NPIs, and 2) tax identification numbers (TINs) that indicate billing entities in Medicare claims. For each of the 11 AQC participants, we assembled all groups in the AMA Group Practice File with names matching the organization or 1 of its constituent parts into a single inclusive group with a unique identifier. We similarly grouped TINs for each AQC participant to the extent we could identify TINs from publicly available information on nonprofit organizations;20 we found TINs for at least 1 major organizational component of 7 AQC participants. We then applied the assignment rules to each beneficiary twice, using each source of provider group identifiers independently. For each year, we classified beneficiaries as members of the intervention group if they were assigned to an organization participating in the AQC via either their Group Practice File group or TIN assignment. Of beneficiary assignments to AQC participants, 91.9% were determined from Group Practice File data and 21.4% from TINs (13.3% from both). We classified other beneficiaries assigned to non-participating providers as the control group. Based on these assignments, the distribution of Medicare beneficiaries across AQC participants (N=417,182 person-years) and non-participating providers (N=1,344,143 person-years) was similar to that among BCBS enrollees.10,11

Study Variables

Spending

For each beneficiary, we calculated total spending on hospital and outpatient care in each quarter from 2007 through 2010 by summing Medicare reimbursements, coinsurance amounts, and payments from other primary payers. We excluded indirect medical education (IME) and disproportionate share hospital payments. We omitted the first quarter of 2007 from analyses because it concluded a period of transition to mandatory use of NPIs by physicians in all submitted claims.21 Because savings for BCBS enrollees in the AQC were greater for spending on outpatient care and specific types of services, including imaging, procedures, and tests, we used place of service codes to distinguish outpatient from inpatient care and classified spending by Berenson-Eggers Type of Service (BETOS) categories examined in previous evaluations of the AQC.10,11,22 To adjust for the elimination of Medicare fees for inpatient and outpatient specialty consultations in 2010,23 we counted consultations as office or hospital visits and applied standardized fees to these broadened categories of evaluation and management services uniformly across study years (Appendix).

Quality of Care

For all beneficiaries in each year, we created an indicator of being hospitalized at least once for an ambulatory care-sensitive condition (ACSC), as defined by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Prevention Quality Indicators.24 We focused on ACSCs related to cardiovascular disease or diabetes, conditions targeted by quality measures in the AQC. For hospitalized beneficiaries in each year, we also created an indicator of being readmitted within 30 days of discharge at least once during the year. Results were similar when readmissions and admissions for ACSCs were analyzed as counts.

We also constructed from claims several annual process measures of quality adapted from the Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS®): screening mammography for women ages 65–69; LDL cholesterol testing for beneficiaries with a history of ischemic heart disease, myocardial infarction, or stroke; and hemoglobin A1c testing, LDL cholesterol testing, and diabetic retinal exams for beneficiaries with diabetes.

Covariates

From Medicare enrollment files, we determined age, sex, race and ethnicity, disability upon enrollment in Medicare, presence of end-stage renal disease, and Medicaid eligibility. We assessed race and ethnicity to control for differences in spending and quality of care among different racial and ethnic groups. From U.S. Census data, we assessed poverty rates and educational attainment for the elderly population in beneficiaries’ zip code tabulation areas.25 From the CCW, we determined if beneficiaries had been diagnosed with any of 21 conditions by January 1, 2007. Because the CCW includes diagnoses since 1999, it more completely captures the accumulated burden of these chronic diseases than risk scores derived from concurrent or recent claims only.

Statistical Analysis

Using a difference-in-differences approach and linear regression, we estimated average changes in quarterly spending (or annual quality) for the intervention group in the first and second year of exposure to the AQC that were not explained by concurrent changes for the control group. We accounted for the staggered entry of organizations into the AQC by allowing different pre-intervention periods for organizations entering in 2009 (pre-intervention period = 2007–2008) and organizations entering in 2010 (pre-intervention period = 2007–2009) in comparisons with the control group (see Appendix for model specification). First-year results were estimated by averaging differential changes in spending in 2009 for organizations entering the AQC in 2009 with differential changes in 2010 for organizations entering in 2010. Second-year results were estimated from differential changes in spending in 2010 for organizations entering in 2009.

All models included as covariates the sociodemographic and clinical characteristics described above and county fixed effects. To allow non-additive effects of multiple conditions on spending, we also included 6 indicators of having ≥2 to ≥7 conditions. In a sensitivity analysis, we adjusted for CCW conditions present at the start of each study year rather than at baseline; this analysis accounted for observed changes in chronic disease burden during the study period but could be biased by “upcoding” or by successful prevention of conditions such as myocardial infarction by AQC participants. To determine if the AQC disproportionately affected the care of medically complex Medicare beneficiaries, we stratified analyses by whether beneficiaries had ≥5 chronic conditions at baseline (23% of the study population).

In addition to regression adjustments, we used a propensity-score weighting technique to balance beneficiary characteristics between the intervention and control groups.26 Specifically, we fitted a logistic regression model predicting assignment to an organization participating in the AQC as a function of all covariates, including county fixed effects to balance the geographic distribution of comparison groups. From this model, we determined the predicted probability of belonging to the opposite group for each beneficiary and weighted analyses by these probabilities.27,28

We tested 2 key assumptions of our difference-in-differences approach to isolating changes in spending and quality associated with the AQC. First, we tested whether spending trends were similar for the intervention and control groups before organizations entered the AQC and adjusted for any differences in trends. Second, we tested whether the composition of the intervention group differentially changed over time relative to the control group by comparing group differences in sociodemographic and clinical characteristics in 2007–2008 vs. 2009–2010.

We also conducted a sensitivity analysis controlling for differences in organizational size between AQC participants and non-participating providers, using the number of attributed beneficiaries and number of affiliated physicians as measures of provider group size (Appendix). By including both county effects and group size in propensity-score models, we effectively limited this analysis to subgroups of beneficiaries in the intervention and control groups who shared a similar geographic distribution and were also attributed to similarly sized provider groups. We repeated this analysis excluding county effects to relax the geographical constraint.

We used Taylor series methods to adjust standard errors for clustering within provider groups and within beneficiaries over time.29 Our results were substantively similar when using generalized linear models with a log link and proportional to mean variance function for spending and logistic regression for quality indicators.30 We report two-sided P values with a significance threshold of P<0.05. All analyses were conducted with SAS, version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina). Our study protocol was approved by the Harvard Medical School Committee on Human Studies and Privacy Board of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services.

RESULTS

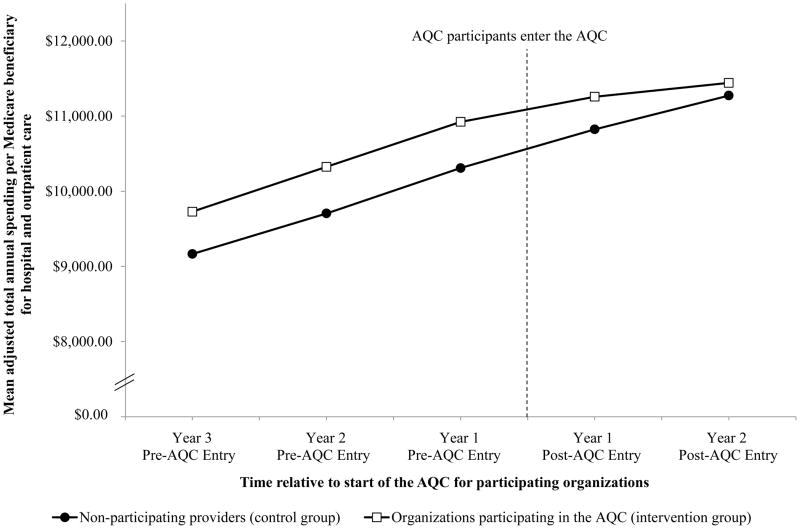

Differential changes in sociodemographic and clinical characteristics were small for the intervention group relative to the control group, and none were statistically significant (Table 1 and Appendix Table 1). As depicted in the Figure, adjusted total quarterly spending was $150 higher (95% CI, $25–$274; P=0.02) for the intervention group than for the control group and spending trends were similar before AQC incentives were implemented for participating organizations (difference in total spending trend: $2 faster per quarter for the intervention group; 95% CI, −$9–$13; P=0.69). In year 2 of the intervention group’s exposure to the AQC, the spending difference between the intervention and control groups was reduced to $51 (95% CI, −$109–$210; P=0.53), constituting a significant differential change of −$99 (95% CI, −$183–−$16; P=0.02), or a 3.4% savings relative to an expected quarterly mean of $2,895 (Table 2). Savings in year 1 were not statistically significant (differential change: −$34; 95% CI, −$83–$16; P=0.18).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of Medicare beneficiaries served by organizations participating in the AQC and non-participating providers*

| Characteristic |

Intervention group Beneficiaries assigned to organizations participating in the AQC (417,182 person-years) |

Control group Beneficiaries assigned to non-participating providers (1,344,143 person-years) |

Differential change for intervention vs. control group (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2007–08 | 2009–10 | 2007–08 | 2009–10 | ||

| Age (yr), mean | 77.2 ± 0.1 | 78.5 ± 0.1 | 77.2 ± 0.1 | 78.5 ± 0.1 | −0.0 (−0.1, 0.1) |

| Female, % | 61.2 | 61.4 | 61.2 | 61.4 | −0.1 (−0.4, 0.2) |

| Race/ethnicity, % | |||||

| White | 93.7 | 93.5 | 93.6 | 93.6 | −0.2 (−0.6, 0.3) |

| Black | 2.9 | 3.0 | 2.9 | 2.9 | 0.0 (−0.2, 0.3) |

| Hispanic | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.0 (−0.1, 0.1) |

| Other | 2.7 | 2.8 | 2.8 | 2.8 | 0.1 (−0.1, 0.4) |

| Medicaid recipient,† % | 13.2 | 13.1 | 13.4 | 13.0 | 0.3 (−0.4, 0.9) |

| Disabled,‡ % | 6.9 | 6.7 | 6.9 | 6.7 | 0.1 (−0.1, 0.2) |

| ESRD, % | 0.6 | 0.7 | 0.6 | 0.7 | 0.0 (0.0, 0.1) |

| CCW conditions present at baseline before 2007¶ | |||||

| 4+ conditions, % | 35.0 | 30.4 | 34.6 | 30.6 | −0.6 (−1.3, 0.1) |

| 5+ conditions, % | 23.0 | 19.0 | 22.7 | 19.1 | −0.4 (−1.0, 0.2) |

| Total number, mean | 2.9 ± 0.1 | 2.7 ± 0.1 | 2.9 ± 0.0 | 2.7 ± 0.0 | −0.0 (−0.1, 0.0) |

| CCW conditions present by study year | |||||

| 4+ conditions, % | 38.1 | 44.6 | 37.3 | 43.9 | −0.2 (−0.9, 0.6) |

| 5+ conditions, % | 25.6 | 31.1 | 25.1 | 30.8 | −0.2 (−0.9, 0.4) |

| Total number, mean | 3.1 ± 0.1 | 3.5 ± 0.1 | 3.1 ± 0.0 | 3.5 ± 0.0 | −0.0 (−0.1, 0.0) |

| ZCTA-level characteristics, mean | |||||

| % below FPL | 8.6 | 8.6 | 8.6 | 8.6 | −0.0 (−0.1, 0.1) |

| % with high school degree | 78.1 | 78.0 | 77.9 | 78.3 | −0.4 (−0.9, 0.0) |

| % with college degree | 23.7 | 23.6 | 23.5 | 23.8 | −0.4 (−0.9, 0.0) |

Plus-minus values are means ±SD. ESRD denotes end-stage renal disease, CCW denotes Chronic Condition Warehouse, ZCTA denotes zip code tabulation area, and FPL denotes federal poverty level.

Medicaid eligibility is based on state buy-in indicators in Medicare enrollment files.

Disability indicates disability as the original reason for Medicare eligibility.

See Appendix Table 1 for comparisons of each of the 21 conditions in the CCW: diabetes, ischemic heart disease, myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, atrial fibrillation, chronic kidney disease, stroke or TIA, COPD, depression, osteoarthritis or rheumatoid arthritis, osteoporosis, hip fracture, dementia, Alzheimer’s disease, breast cancer, colorectal cancer, prostate cancer, lung cancer, endometrial cancer, glaucoma, cataracts. Summary chronic condition counts do not include the two ophthalmologic conditions, glaucoma and cataracts.

Appendix Table 1.

Chronic conditions among Medicare beneficiaries served by organizations participating in the AQC and non-participating providers

| Conditions from Chronic Condition Warehouse |

Intervention group Beneficiaries assigned to organizations participating in the AQC (417,182 person-years) |

Control group Beneficiaries assigned to non-participating providers (1,344,143 person-years) |

Differential change for intervention vs. control group (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2007–08 | 2009–10 | 2007–08 | 2009–10 | ||

| Conditions present by baseline in 2007, % | |||||

| Diabetes | 29.3 | 27.8 | 29.2 | 27.9 | −0.2 (−0.7, 0.3) |

| Ischemic heart disease | 47.7 | 44.4 | 47.3 | 44.8 | −0.8 (−1.4, −0.2) |

| H/o myocardial infarction | 5.1 | 4.3 | 5.0 | 4.3 | −0.1 (−0.3, 0.1) |

| Congestive heart failure | 24.9 | 21.5 | 24.8 | 21.5 | −0.2 (−0.8, 0.4) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 15.8 | 13.6 | 15.6 | 13.7 | −0.3 (−0.7, 0.0) |

| Chronic kidney disease | 13.3 | 11.3 | 13.1 | 11.4 | −0.3 (−0.6, 0.1) |

| H/o stroke or TIA | 11.7 | 10.3 | 11.7 | 10.2 | 0.1 (−0.2, 0.3) |

| COPD | 19.9 | 17.4 | 19.7 | 17.5 | −0.2 (−0.6, 0.3) |

| Depression | 22.9 | 20.9 | 22.7 | 21.0 | −0.4 (−0.7, 0.0) |

| OA or RA | 35.1 | 33.7 | 34.9 | 33.9 | −0.4 (−0.9, 0.0) |

| Osteoporosis | 35.2 | 34.1 | 34.9 | 34.4 | −0.5 (−1.0, −0.1) |

| H/o hip fracture | 2.8 | 2.3 | 2.9 | 2.2 | 0.1 (0.0, 0.2) |

| Dementia | 10.0 | 7.7 | 10.1 | 7.5 | 0.3 (0.0, 0.5) |

| Alzheimer’s disease | 4.0 | 2.8 | 4.0 | 2.8 | 0.1 (−0.2, 0.3) |

| Breast cancer | 5.2 | 4.9 | 5.1 | 5.0 | −0.2 (−0.4, 0.0) |

| Colorectal cancer | 3.0 | 2.7 | 3.0 | 2.7 | 0.0 (−0.1, 0.1) |

| Prostate cancer | 6.0 | 5.7 | 6.0 | 5.7 | −0.0 (−0.2, 0.1) |

| Lung cancer | 1.4 | 1.0 | 1.4 | 1.1 | −0.1 (−0.3, 0.0) |

| Endometrial cancer | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.6 | −0.0 (−0.1, 0.0) |

| Glaucoma | 24.9 | 24.1 | 24.7 | 24.3 | −0.3 (−0.7, 0.0) |

| Cataracts | 69.7 | 67.8 | 69.3 | 68.0 | −0.6 (−1.1, −0.2) |

| Conditions present by study year, % | |||||

| Diabetes | 30.6 | 33.4 | 30.4 | 33.5 | −0.3 (−0.8, 0.2) |

| Ischemic heart disease | 49.7 | 53.1 | 48.9 | 52.6 | −0.3 (−0.9, 0.3) |

| H/o myocardial infarction | 5.5 | 6.2 | 5.4 | 6.1 | −0.0 (−0.3, 0.2) |

| Congestive heart failure | 26.7 | 29.2 | 26.3 | 28.9 | −0.1 (−0.7, 0.6) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 17.0 | 19.0 | 16.6 | 18.6 | −0.0 (−0.4, 0.3) |

| Chronic kidney disease | 15.2 | 20.3 | 14.8 | 19.8 | 0.1 (−0.5, 0.7) |

| H/o stroke or TIA | 12.6 | 14.5 | 12.5 | 14.3 | 0.1 (−0.2, 0.5) |

| COPD | 21.2 | 23.2 | 20.8 | 22.5 | 0.3 (−0.1, 0.8) |

| Depression | 24.5 | 27.8 | 24.0 | 27.6 | −0.2 (−0.7, 0.3) |

| OA or RA | 37.0 | 42.5 | 36.6 | 42.0 | 0.0 (−0.7, 0.7) |

| Osteoporosis | 36.8 | 41.3 | 36.3 | 41.1 | −0.3 (−0.9, 0.3) |

| H/o hip fracture | 3.2 | 3.9 | 3.2 | 3.9 | 0.1 (−0.1, 0.2) |

| Dementia | 11.3 | 13.6 | 11.3 | 13.6 | −0.0 (−0.4, 0.4) |

| Alzheimer’s disease | 4.7 | 5.6 | 4.7 | 5.9 | −0.3 (−0.6, 0.0) |

| Breast cancer | 5.5 | 6.0 | 5.3 | 6.0 | −0.1 (−0.3, 0.1) |

| Colorectal cancer | 3.2 | 3.5 | 3.2 | 3.4 | 0.1 (−0.1, 0.2) |

| Prostate cancer | 6.3 | 6.9 | 6.3 | 6.8 | 0.1 (−0.1, 0.3) |

| Lung cancer | 1.6 | 1.7 | 1.5 | 1.8 | −0.2 (−0.3, 0.0) |

| Endometrial cancer | 0.7 | 0.8 | 0.7 | 0.8 | −0.0 (−0.1, 0.0) |

| Glaucoma | 25.9 | 28.7 | 25.7 | 28.8 | −0.4 (−0.8, 0.0) |

| Cataracts | 72.2 | 78.6 | 71.5 | 78.1 | −0.2 (−0.9, 0.6) |

TIA = transient ischemic attack; COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; OA = osteoarthritis; RA = rheumatoid arthritis

Figure. Mean annual spending in Medicare between AQC participants and non-participating providers before and after participating organizations entered the AQC.

Adjusted annual per-beneficiary spending means are plotted for organizations participating in the AQC (intervention group) and non-participating providers (control group) before and after participating organizations entered the AQC. To display spending changes that were averaged across organizations entering in 2009 or 2010, we aligned the times of entry by these 2 groups of AQC participants and adjusted for the mean spending difference between the 2 groups prior to their entry. Thus, spending differences between organizations entering in 2009 and the control group contributed to overall average differences for 2 years before AQC entry (2007–2008) and 2 years after AQC entry (2009–2010), while spending differences between organizations entering in 2010 and the control group contributed to overall average differences for 3 years before AQC entry (2007–2009) and 1 year after AQC entry (2010).

Table 2.

Difference-in-differences estimates of effects of the AQC on quarterly spending for Medicare beneficiaries*

| Quarterly spending variable | Unadjusted quarterly mean† | Differential change for intervention vs. control group | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Contract year 1 mean (95% CI) | P value | Contract year 2 mean (95% CI) | P value | ||

| Total spending,‡ $ | 2,895 | −34 (−83, 16) | 0.18 | −99 (−183, −16) | 0.02 |

| Spending by broad category, $ | |||||

| Hospital inpatient facility | 1,309 | 7 (−19, 32) | 0.61 | −13 (−75, 50) | 0.69 |

| Outpatient care | 1,244 | −41 (−65, −17) | <.001 | −73 (−97, −50) | <.001 |

| Hospital outpatient department | 551 | −14 (−32, 4) | 0.12 | −24 (−55, 8) | 0.14 |

| Other outpatient services | 691 | −27 (−38, −15) | <.001 | −49 (−71, −26) | <.001 |

| Other | 340 | 2 (−7, 10) | 0.73 | −13 (−24, −3) | 0.02 |

| Spending by BETOS category,¶ $ | |||||

| Evaluation and management | |||||

| Office visits | 234 | −6 (−10, −2) | 0.003 | −9 (−13, −6) | <.001 |

| Hospital visits | 113 | 1 (−2, 4) | 0.63 | −3 (−7, 0) | 0.08 |

| Emergency room visits | 57 | 1 (−2, 4) | 0.53 | −3 (−6, −1) | 0.02 |

| Nursing home and home visits | 25 | 0 (−1, 1) | 0.89 | −1 (−3, 0) | 0.07 |

| Major procedures | 170 | −6 (−13, 1) | 0.07 | −4 (−10, 1) | 0.12 |

| Minor/ambulatory procedures and endoscopy | 246 | −5 (−10, 1) | 0.13 | −12 (−18, −5) | <.001 |

| Imaging | 181 | −5 (−8, −2) | 0.002 | −13 (−17, −8) | <.001 |

| Cardiac interventions and tests | 50 | −1 (−3, 0) | 0.06 | −3 (−5, 0) | 0.06 |

| Lab tests | 109 | 0 (−2, 2) | 0.99 | −4 (−7, −2) | 0.001 |

| Dialysis | 38 | −1 (−2, 1) | 0.47 | −1 (−4, 3) | 0.78 |

| Other | 170 | −0 (−4, 3) | 0.96 | −6 (−10, −1) | 0.01 |

Contract year 1 refers to 2009 for beneficiaries assigned to provider groups entering the AQC in 2009 and to 2010 for beneficiaries assigned to provider groups entering the AQC in 2010. Contract year 2 refers to 2010 for beneficiaries assigned to provider groups entering the AQC in 2009. BETOS = Berenson-Eggers Type of Service.

Counterfactual mean predicted for the intervention group in 2010 under the scenario in which there was no differential change.

Total spending is the sum of spending on hospital inpatient facility care, physician/supplier services and hospital outpatient department care. Our analysis did not include institutional claims for skilled nursing facility, home health, or hospice care.

Includes claims from carrier claims files and hospital outpatient department claims files. BETOS codes were grouped as follows: office visits (M1A-M1B); hospital visits (M2A-M2C); emergency room visits (M3); nursing home and home visits (M4A-M4B); major procedures (P0, P4A-P4E, P1A-P3D except P2D); minor and ambulatory procedure and endoscopy (P5A-P5E, P6A-P6D, P8A-P8I); imaging (I1A-I1F, I2A-I2D, I3A-I3F); cardiac interventions and tests (I4A-I4B, P2D, T2A-T2D); lab tests (T1A-T1H); and dialysis (P9A-P9B).

As summarized in Table 2, savings in year 2 were explained largely by differential changes in outpatient care (−$73; 95% CI, −$97–−$50; P<0.001) and included significant differential changes in spending on office visits (−$9; 95% CI, −$13–−$6; P<0.001), emergency room visits (−$3; 95% CI, −$6–−$1; P=0.02), minor procedures (−$12; 95% CI, −$18–−$5; P<0.001), imaging (−$13; 95% CI, −$17–−$8; P<0.001), and laboratory tests (−$4; 95% CI, −$7–−$2; P=0.001).

Estimated savings in year-2 spending on outpatient care for the intervention group were greater among beneficiaries with ≥5 conditions (−$125; 95% CI, −$169–−$80) than among those with fewer conditions (−$61; 95% CI, −$85–−$36; P=0.002 for difference between groups). Estimated savings were slightly larger when adjusted for conditions present at the start of each study year, and the differential change in total spending in year 1 became statistically significant (−$47; 95% CI, −$91–−$3; P=0.04). Estimated savings were similar or larger when adjusted for preceding spending trends in a sensitivity analysis, except the differential change in spending on office visits was smaller and no longer significant. Results were not substantially altered by adjustment for provider organizational size, with or without adjustment for county.

Relative to the control group, annual rates of LDL testing were 2.2 percentage points higher (95% CI, 0.4–4.0; P=0.02) for beneficiaries with diabetes in the intervention group prior to entering the AQC. This difference increased further to 5.2 percentage points (95% CI, 2.5–7.9; P=0<0.001) by year 2 of exposure to the AQC, constituting a significant differential improvement of 3.1 percentage points (95% CI, 1.4–4.8; P<0.001). A similar differential improvement in LDL testing rates occurred for beneficiaries in the intervention group with cardiovascular disease (2.5 percentage points; 95% CI, 1.1–4.0; P<0.001), but performance on other quality measures did not differentially change (Table 3).

Table 3.

Difference-in-differences estimates of effects of the AQC on quality of care for Medicare beneficiaries*

| Annual quality measure | Unadjusted annual mean† | Differential change for intervention vs. control group | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Contract year 1 mean (95% CI) | P value | Contract year 2 mean (95% CI) | P value | ||

| Admission rate for ACSCs related to cardiovascular disease or diabetes, % | 2.6 | 0.1 (−0.1, 0.2) | 0.24 | 0.1 (−0.1, 0.3) | 0.21 |

| 30-day readmission rate, % | 18.3 | −0.2 (−1.0, 0.4) | 0.50 | −0.0 (−1.0, 0.8) | 0.95 |

| Screening mammography, % | 65.4 | 0.0 (−1.5, 1.5) | 0.98 | 1.4 (−1.0, 3.8) | 0.26 |

| Diabetes care, % | |||||

| LDL cholesterol testing | 77.3 | 0.9 (−0.1, 1.9) | 0.07 | 3.1 (1.4, 4.8) | <.001 |

| Hemoglobin A1c testing | 72.8 | 0.2 (−0.6, 1.0) | 0.61 | 0.5 (−0.3, 1.3) | 0.23 |

| Retinal exam | 67.7 | −1.0 (−1.8, −0.3) | 0.009 | −0.1 (−2.4, 2.2) | 0.94 |

| Cardiovascular disease care, % | |||||

| LDL cholesterol testing | 71.0 | 0.6 (−0.4, 1.5) | 0.26 | 2.5 (1.1, 4.0) | <.001 |

In calculating admission and readmission rates, we counted up to one admission or readmission per beneficiary annually to estimate the fractions of beneficiaries admitted or readmitted at least once. Readmissions were assessed among beneficiaries with at least one acute care hospitalization during the year. We excluded transfers from readmission counts, as well as readmissions from skilled nursing facilities (SNFs) because organizations participating in the AQC include few nursing facilities and have fewer means to influence post-acute SNF care than they do outpatient care. Admissions for ambulatory care-sensitive conditions exclude transfers and are based on the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Prevention Quality Indicators of hospitalization for conditions related to cardiovascular disease or diabetes (PQI #1, 3, 7, 8, 13, 14, and 16): short-term and long-term complications of diabetes, uncontrolled diabetes, lower-extremity amputation, hypertension, congestive heart failure, and angina without procedure. Screening mammography was assessed among women ages 65–69 years. Diabetes services were assessed among beneficiaries with a history of diabetes prior to 2007. LDL testing for cardiovascular disease was assessed among beneficiaries with ischemic heart disease, history of myocardial infarction, or history of stroke or TIA present prior to 2007. LDL = low-density lipoprotein and ACSC = ambulatory care-sensitive condition.

Counterfactual mean predicted for the intervention group in 2010 under the scenario in which there was no differential change.

COMMENT

The AQC was associated with significant reductions in spending for Medicare beneficiaries but not with consistently better quality of care. Similar to observed savings among BCBS commercial enrollees in the AQC, savings in Medicare grew in year 2 of AQC incentives, were greater for patients with more clinical conditions, derived largely from lower spending on outpatient care, and included reductions in spending on procedures, imaging, and tests.10,11 These findings suggest that global payment incentives in the AQC elicited responses from participating organizations that extended beyond targeted case management of BCBS enrollees. AQC participants reported adopting several strategies that could have influenced patient care for which they did not bear financial risk, such as rewarding constituent physicians or groups for efficient practices, changing referral patterns, engaging in high-risk case management across multiple payers, and redesigning care processes to eliminate waste.13

A previous evaluation found a $27 reduction in total quarterly spending for BCBS enrollees in year 2 of the AQC, attributable to shifts in care to lower priced provider groups as well as to lower utilization achieved by some participating organizations.11 This reduction was 4 times larger and entirely concentrated among medically complex enrollees who more closely resembled Medicare beneficiaries but whose spending levels were still well below average spending for beneficiaries in our study. Due to these differences in patient populations and the imprecision of our results (95% CI for total per-beneficiary savings ranging from −$16 to −$183), we could not assess the magnitude of savings among Medicare beneficiaries relative to savings demonstrated among BCBS enrollees. Some interventions tailored specifically to BCBS enrollees would be expected to have minimal effects on care for Medicare beneficiaries (e.g., case management to prevent admissions), while other targeted interventions (e.g., rewarding efficiency based on care for BCBS patients) and systemic changes (e.g., electronic clinical decision support to reduce inappropriate imaging) could potentially have greater effects on care for Medicare beneficiaries because of their greater disease burden. We could not attribute savings in Medicare to specific interventions among the many implemented by AQC participants.

Shifts in care away from outpatient facilities that charge higher prices, as observed among BCBS enrollees in the AQC,10,11 could have contributed to overall savings in Medicare, too, because hospital outpatient departments are paid facility fees in excess of standard Medicare reimbursements.31 Because administratively set Medicare fees otherwise vary minimally within regions, the $49 quarterly savings in spending for outpatient care not billed by hospital departments reflects changes in utilization among beneficiaries served by AQC participants.

For Medicare beneficiaries with cardiovascular disease and diabetes, we found evidence of significant improvement in 1 process measure of quality but not in 3 others included in the AQC and not in hospitalizations that might be prevented by better cardiovascular disease and diabetes control rewarded by the AQC. These weaker and inconsistent associations of the AQC with quality of care for Medicare beneficiaries suggest quality improvement efforts by participants may have been targeted more specifically to BCBS enrollees than efforts to control spending, which were associated with savings in Medicare. For example, AQC participants may have relied more heavily on analytic support from BCBS and patient-specific outreach to identify and redress quality deficits among BCBS enrollees, while implementing broader strategies to address spending. Alternatively, a more complete assessment of quality of care for Medicare beneficiaries might reveal more consistent improvements across quality measures included in the AQC, most of which we could not assess from Medicare claims.

Our findings have several important implications for payment and delivery system reforms. In general, cost-reducing spillover effects of ACO contracts with one insurer on care for other insurers’ enrollees should signal a willingness among provider organizations generating the spillovers to enter similar contracts with additional insurers; they could be rewarded for the savings and quality improvements achieved for the other insurers’ enrollees. Broad organizational responses to early ACO initiatives, like those suggested by our findings, might support a rapid transition among ACOs to global payment arrangements with multiple payers. Conversely, cost-reducing spillovers present a free-riding problem to commercial insurers engaged in ACO contracts, since competing insurers with similar provider networks could offer lower premiums without incurring the costs of managing an ACO. To foster multi-payer participation, commercial ACO contracts could be restructured to allow participating insurers to appropriate the spillovers or to encourage organizations to enter similar contracts with other insurers.

Our study had several limitations. Several factors limited statistical power for comparing savings by the presence of prior risk-based contracts held by AQC participants with BCBS, an important predictor of savings among BCBS enrollees.10,11 The Medicare population served by AQC participants was approximately one fifth the size of the BCBS population included in previous evaluations of the AQC, the variance in medical spending for Medicare beneficiaries is much greater than for commercially insured patients, and a minority of BCBS enrollees and Medicare beneficiaries exposed to 2 years of AQC incentives by 2010 were served by organizations without prior risk contracts in place.10,11,13

Differential changes in unobserved case mix could have contributed to our findings, but differences in observed patient characteristics between AQC participants and non-participating providers remained constant over the study period. Although our results and those of previous evaluations varied similarly across settings and services, suggesting savings among Medicare beneficiaries were related to the AQC, participating organizations could have concurrently implemented unrelated interventions to improve care efficiency for all patients. Similarly, as legislative measures to control spending were debated in Massachusetts and Medicare ACO programs proposed nationally, organizations may have broadened interventions related to the AQC in anticipation of future risk contracts with additional payers.32–34

Nevertheless, our study suggests that organizations in Massachusetts willing to assume greater financial risk were capable of achieving modest reductions in spending for Medicare beneficiaries without compromising quality of care. Although effects of commercial and Medicare ACO initiatives similar to the AQC may differ in other markets, these findings suggest potential for these payment models to foster systemic change in care delivery. Evaluations of ACO programs may need to consider spillover effects on other patient populations to assess their full clinical and economic benefits.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dana G. Safran, Sc.D. (Blue Cross Blue Shield of Massachusetts) for comments on an earlier draft of this manuscript and to Pasha Hamed, M.A. (Department of Health Care Policy, Harvard Medical School) for statistical programming support. Dr. Safran was not compensated for her contributions. Mr. Hamed’s contributions were supported by the same funding sources as the authors’ contributions.

Funding sources and role of sponsors: Supported by grants from the Beeson Career Development Award Program (National Institute on Aging K08 AG038354 and the American Federation for Aging Research), Doris Duke Charitable Foundation (Clinical Scientist Development Award #2010053), National Institute on Aging (P01 AG032952), and Commonwealth Fund (#20110391). The funding sources did not play a role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; or preparation, review, and approval of the manuscript.

APPENDIX

A. Linkage to American Medical Association (AMA) Group Practice File

The linkage of NPIs to the AMA Masterfile and Group Practice File was conducted by Medical Marketing Services, Inc., based on a finder file we submitted containing all NPIs with any physician specialty that appeared in 2009 physician/supplier (carrier) claims for a national 20% random sample of Medicare beneficiaries.

For physicians in the AMA Physician Masterfile practicing in groups of 3 or more, the AMA Group Practice File identifies their practice site(s) and, if part of a larger group, the position of member practices in larger organizational structures (as satellites of parent groups, parents to smaller practices, or both). For group practices identified as members of larger parent organizations, we used the highest level of organization to which they were connected (through up to 5 levels of satellite-parent relationships) for analyses. For example, a practice site may be part of a multi-site group, which in turn might be a member of a larger physician organization. In that case, we focused only on the membership of linked NPIs to the larger physician organization. Physician rosters and practice information in the Group Practice File are verified and updated every 9–12 months by the AMA Group Practice Unit via telephone and fax communications with practice managers and from provider group websites.

Using the following procedure, we determined that the AMA Group Practice File identified provider groups for approximately 94% of primary care physicians (PCPs) in the AMA Masterfile who were treating Medicare beneficiaries in Massachusetts in 2009 and practicing in groups of 3 or more physicians. From 2009 carrier claims for the national 20% sample of beneficiaries, we identified 128,658 PCPs nationally (Health Care Financing Administration (HCFA) provider specialty codes for general practice (01), family practice (08), internal medicine (11), or geriatric medicine (38)) actively providing outpatient primary care services (Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes 99201–99215 or G0402) to at least 5 Medicare beneficiaries, following the definitions of PCPs and outpatient primary care services used by the assignment rules for the Medicare Shared Savings Program (SSP) and Pioneer ACOs (Appendix Table 2).

Appendix Table 2.

Evaluation and management (E&M) service codes used to assign Medicare beneficiaries to Shared Savings Program and Pioneer Accountable Care Organizations

| Current Procedural Terminology Codes for E&M Physician Services | Setting/Description of E&M Physician Services |

|---|---|

| 99201–99215 | Office or other outpatient services |

| 99304–99318 | Nursing facility services |

| 99324–99340 | Domiciliary, rest home, or custodial care services |

| 99341–99350 | Home services |

| G0402, G0438, G0439* | Wellness visits |

Codes G0438 and G0439 were not in use in 2009

Of these PCPs, 96% were linked via their NPIs to the AMA Physician Masterfile. We assumed PCPs without Group Practice File records who were billing primarily under tax identification numbers (TINs) associated with only 1 or 2 NPIs in carrier claims were not likely to be practicing in groups of 3 or more. After excluding this group, 68% of PCPs in the AMA Masterfile were linked to the Group Practice File. We improved this linkage rate to 90% by inferring group practice affiliations for PCPs not linked to the Group Practice File who shared TINs with PCPs who were linked to the Group Practice File. Specifically, we defined each NPI’s primary office-based TIN as the TIN associated with the most allowed charges by that NPI for outpatient visits in carrier claims. We then assigned each non-linked NPI to the parent group in the AMA Group Practice File to which other NPIs with the same primary office-based TIN were most frequently linked. We similarly inferred group practice affiliations for nurse practitioners (NPs) and physician assistants (PAs) whose NPIs were not linked to the AMA Masterfile (because it only includes physicians) but who are recognized as providers in Medicare ACO assignment algorithms (HCFA provider specialty codes 50 and 97), as described below. For PCPs in Massachusetts, the linkage rate was 94%, higher than the 90% national linkage rate.

Among medical and surgical specialists identified in carrier claims nationally, 91% were linked to the AMA Masterfile. Of those likely practicing in groups of 3 or more, we determined AMA group practice affiliations for 81% in Massachusetts. The lower linkage rate for specialists than for PCPs in Massachusetts was of little consequence for our analysis because beneficiary assignment under the SSP rules is driven primarily by receipt of primary care from PCPs, as described below. In addition, we would not expect some specialists (e.g., consulting proceduralists) to be identified by the Group Practice File or to contribute to beneficiary assignment, because of limited practice in office-based settings.

B. Assigning Beneficiaries to Provider Groups

Following the Medicare Shared Savings Program (SSP) rules,14 with slight modifications, we assigned each beneficiary who received at least 1 primary care service from a PCP to the provider group accounting for the most allowed charges among all provider groups for primary care services provided by PCPs, NPs, or PAs. We then assigned the minority of beneficiaries who received no primary care services from a PCP, NP, or PA to provider groups accounting for the plurality of allowed charges for primary care services provided by specialists.

In both the Medicare SSP and Pioneer rules, the definition of primary care services includes physician visits at nursing facilities (Appendix Table 2). We excluded these services from the definition of primary care services when assigning beneficiaries to provider groups, because we previously found that the inclusion of physician visits at nursing facilities causes the assignment of over 25% of community-dwelling beneficiaries receiving post-acute care to shift away from the provider group providing primary care to the group providing post-acute care.16

C. Adjustment for Elimination of Specialty Consultation Fees in 2010

Beginning in 2010, Medicare eliminated fees for the following evaluation and management (E&M) codes for specialty consultations: 99241–99245 (outpatient specialty consultations) and 99251–99255 (inpatient specialty consultations).23 In place of these codes, specialists can bill outpatient consultations as general office visits (99201–99205 for new patients, 99211–99215 for established patients) and inpatient consultations as general hospital visits (99221–99223 for initial hospital visit, 99231–99233 for subsequent visits during the stay). Therefore, we classified outpatient specialty consultations as office visits and inpatient consultations as hospital visits to maintain a consistent categorization across study years. We then applied a single standardized price for an office visit (equal to mean spending per visit in 2009 across all office visits and outpatient consultations) to each office visit (including outpatient specialty consultations) in all study years, and applied a single standardize price for a hospital visit (equal to mean spending per visit in 2009 across all hospital visits and inpatient consultations) to each hospital visit (including inpatient specialty consultations) in all study years. With these adjustments, the elimination of the specialty consultation fees would not induce an abrupt change in spending for E&M services.

D. Model Specification

For each dependent quarterly spending variable and annual quality indicator (Y) for beneficiary i in quarter or year t, we fit the following linear regression model:

where Time is a vector of quarter or year dummies from 2007–2010; AQC2009 indicates assignment of beneficiary i at time t to a provider organization that entered the AQC in 2009; AQC2010 indicates assignment of beneficiary i at time t to an organization that entered the AQC in 2010; AQCYear1 equals 1 in 2009 for beneficiaries assigned to organizations that entered the AQC in 2009, equals 1 in 2010 for beneficiaries assigned to organizations that entered the AQC in 2010, and equals zero otherwise; AQCYear2 equals 1 in 2010 for beneficiaries assigned to organizations that entered the AQC in 2009 and zero otherwise; Medicaid indicates receipt of Medicaid benefits based on state buy-in indicators; ESRD is an indicator of end-stage renal disease at time t; Disability is an indicator of disability as the original reason for Medicare eligibility; CCW is a vector of 21 indicators of chronic conditions listed in Appendix Table 1 and 6 indicators of multiple conditions (≥2 to ≥7); ZCTAcharacteristics include rates of poverty, having a high school degree, and having a college degree among elderly persons in beneficiary i’s zip code tabulation area; and County is a vector of county fixed effects. Observations were weighted by propensity-score weights and standard errors adjusted for clustering as described in the Methods.

Thus, β4 estimates the average effect of year 1 of exposure to the AQC on spending or quality for beneficiaries assigned to organizations entering in either 2009 or 2010, and β5 estimates the effect of year 2 of exposure to the AQC for beneficiaries assigned to organizations entering in 2009. To test for differences in spending trends between the intervention and control groups prior to the start of the AQC for the intervention group, we limited observations to 2007–2008 for organizations entering in 2009 and to 2007–2009 for organizations entering in 2010 and for the control group, and estimated an interaction term between time (specified continuously) and an indicator of assignment to an organization entering the AQC in either 2009 or 2010. To adjust for the minimal differences in trends that we found, we added this interaction term to analytic models.

An alternate specification in which we specified dummy variables for each organization participating in the AQC in place of terms β2–β3 yielded nearly equivalent results. We also conducted a sensitivity analysis to determine if any differences in the geographic distribution of beneficiaries served by organizations entering the AQC in 2009 and 2010 may have contributed to estimated savings in year 2 of exposure to the AQC, when the intervention group was limited to organizations entering in 2009. Specifically, we limited both propensity-score and difference-in-differences models to beneficiaries assigned to organizations entering the AQC in 2009 or to the control group of non-participating providers (i.e., excluding beneficiaries assigned to organizations entering the AQC in 2010), thereby ensuring similar geographic distributions for the intervention and control groups in year 2 of exposure to the AQC. Estimates of year 2 savings were not appreciably altered by this restriction. Finally we compared spending trends in 2007–2008 between the control group and organizations entering the AQC in 2009. As characterized by the summary test of trends we present for all AQC participants vs. the control group, these pre-intervention trends were also similar ($1 slower per quarter for organizations entering the AQC in 2009 relative to the control group; P=0.84).

E. Adjustment for Size of Provider Groups

For each provider group defined by an AMA Group Practice File grouping of NPIs or by a TIN, we determined the number of assigned beneficiaries and the number of affiliated NPIs. Following previously described methods,17 we used the larger of the two organizational identifiers (i.e., AMA Group Practice groupings or TINs) to describe the size of each beneficiary’s assigned provider group. We then added to propensity-score and analytic regression models both measures of the size of each beneficiary’s provider group.

Footnotes

Author contributions: see forthcoming authorship forms for details. Dr. McWilliams had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Disclosures: The authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose

References

- 1.The ACO Surprise. Oliver Wyman; 2012. [Accessed June 13, 2013]. http://www.oliverwyman.com/media/OW_ENG_HLS_PUBL_The_ACO_Surprise.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. [Accessed June 13, 2013];CMS names 88 new Medicare Shared Savings Accountable Care Organizations. 2012 http://www.cms.gov/apps/media/press/factsheet.asp?Counter=4405&intNumPerPage=10&checkDate=&checkKey=&srchType=1&numDays=3500&srchOpt=0&srchData=&keywordType=All&chkNewsType=6&intPage=&showAll=&pYear=&year=&desc=&cboOrder=date.

- 3.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. [Accessed June 13, 2013];First Accountable Care Organizations under the Medicare Shared Savings Program. 2012 http://www.cms.gov/apps/media/press/factsheet.asp?Counter=4334&intNumPerPage=10&checkDate=&checkKey=&srchType=1&numDays=3500&srchOpt=0&srchData=&keywordType=All&chkNewsType=6&intPage=&showAll=&pYear=&year=&desc=false&cboOrder=date.

- 4.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. [Accessed June 13, 2013];More doctors, hospitals partner to coordinate care for people with Medicare. 2013 http://www.cms.gov/apps/media/press/release.asp?Counter=4501&intNumPerPage=10&checkDate=&checkKey=&srchType=1&numDays=3500&srchOpt=0&srchData=&keywordType=All&chkNewsType=1%2C+2%2C+3%2C+4%2C+5&intPage=&showAll=&pYear=&year=&desc=&cboOrder=date.

- 5.Zuvekas SH, Cohen JW. Paying physicians by capitation: is the past now prologue? Health Aff (Millwood) 2010;29(9):1661–1666. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fisher ES, Wennberg DE, Stukel TA, Gottlieb DJ, Lucas FL, Pinder EL. The implications of regional variations in Medicare spending. Part 1: the content, quality, and accessibility of care. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138:273–287. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-138-4-200302180-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wennberg JE, Fisher ES, Skinner JS. Geography and the debate over Medicare reform. Health Aff (Millwood) 2002;(Suppl Web Exclusives):W96–114. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.w2.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McGuire TG, Pauly MV. Physician response to fee changes with multiple payers. J Health Econ. 1991;10(4):385–410. doi: 10.1016/0167-6296(91)90022-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Colla CH, Wennberg DE, Meara E, et al. Spending differences associated with the Medicare Physician Group Practice Demonstration. JAMA. 2012;308(10):1015–1023. doi: 10.1001/2012.jama.10812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Song Z, Safran DG, Landon BE, et al. Health care spending and quality in year 1 of the alternative quality contract. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(10):909–918. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1101416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Song Z, Safran DG, Landon BE, et al. The ‘Alternative Quality Contract,’ based on a global budget, lowered Medical spending and improved quality. Health Aff (Millwood) 2012;31(8):1885–1894. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.0327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services’ Office of Research D, and Information. Physician Group Practice Demonstration Evaluation Report. Report to Congress; 2009. [Accessed June 13, 2012]. http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Demonstration-Projects/DemoProjectsEvalRpts/downloads/PGP_RTC_Sept.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mechanic RE, Santos P, Landon BE, Chernew ME. Medical group responses to global payment: early lessons from the ‘Alternative Quality Contract’ in Massachusetts. Health Aff (Millwood) 2011;30(9):1734–1742. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Department of Health and Human Services and Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare program; Medicare Shared Savings Program: accountable care organizations. [Accessed June 13, 2013];Final rule. 2011 http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/FR-2011-11-02/pdf/2011-27461.pdf.

- 15.Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation. [Accessed June 13, 2013];Pioneer Acountable Care Organization (ACO) Model Request for Application. 2011 http://innovations.cms.gov/Files/x/Pioneer-ACO-Model-Request-For-Applications-document.pdf.

- 16.McWilliams JM, Chernew ME, Zaslavsky AM, Landon BE. Post-acute care -- who will be accountable? Health Serv Res. 2013 doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12032. Published online. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McWilliams JM, Chernew ME, Zaslavsky AM, Hamed P, Landon BE. Delivery system integration and health care spending and quality for Medicare beneficiaries. JAMA Intern Med. 2013 doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.6886. Published online. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. [Accessed June 13, 2013];Chronic Condition Data Warehouse. http://www.ccwdata.org/index.htm.

- 19.Medicare Payment Advisory Commission. [Accessed June 13, 2013];Report to the Congress: improving incentives in the Medicare program. 2009 http://www.medpac.gov/documents/jun09_entirereport.pdf.

- 20. [Accessed June 13, 2013];Tax-exempt organizations. http://www.nonprofitfacts.com/

- 21.Department of Health and Human Services. [Accessed June 13, 2013];HIPAA Administrative Simplification: Standard Unique Health Identifier for Health Care Providers. 2004 http://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/HIPAA-Administrative-Simplification/NationalProvIdentStand/downloads/NPIfinalrule.pdf.

- 22.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. [Accessed June 13, 2013];Berenson-Eggers Type of Service (BETOS) https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Coding/HCPCSReleaseCodeSets/BETOS.html.

- 23.Song Z, Ayanian JZ, Wallace J, He Y, Gibson TB, Chernew ME. Unintended consequences of eliminating Medicare payments for consultations. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(1):15–21. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.1125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. [Accessed June 13, 2013];Prevention Quality Indicators Technical Specifications. 2012 http://www.qualityindicators.ahrq.gov/Modules/PQI_TechSpec.aspx.

- 25.U.S. Census Bureau. [Accessed June 13, 2013];American Community Survey 5-year estimates. 2010 http://factfinder2.census.gov/faces/nav/jsf/pages/searchresults.xhtml?refresh=t.

- 26.Funk MJ, Westreich D, Wiesen C, Sturmer T, Brookhart MA, Davidian M. Doubly robust estimation of causal effects. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;173(7):761–767. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwq439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McWilliams JM, Meara E, Zaslavsky AM, Ayanian JZ. Use of health services by previously uninsured Medicare beneficiaries. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:143–153. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa067712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McWilliams JM, Zaslavsky AM, Meara E, Ayanian JZ. Health insurance coverage and mortality among the near-elderly. Health Aff (Millwood) 2004;23:223–233. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.23.4.223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Binder DA. On the variances of asymptotically normal estimators from complex surveys. International Statistical Review. 1983;51:279–292. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Buntin MB, Zaslavsky AM. Too much ado about two-part models and transformation? Comparing methods of modeling Medicare expenditures. J Health Econ. 2004;23(3):525–542. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2003.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Medicare Payment Advisory Commission. [Accessed June 13, 2013];Report to the Congress: Medicare Payment Policy. 2011 Chapter 3 http://www.medpac.gov/chapters/Mar11_Ch03.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ayanian JZ, Van der Wees PJ. Tackling rising health care costs in Massachusetts. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(9):790–793. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1208710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Steinbrook R. Controlling health care costs in Massachusetts with a global spending target. JAMA. 2012;308(12):1215–1216. doi: 10.1001/2012.jama.11322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fisher ES, McClellan MB, Bertko J, et al. Fostering accountable health care: moving forward in Medicare. Health Aff (Millwood) 2009;28:w219–231. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.2.w219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]