Abstract

Backgrounds

The presence of ≥5 circulating tumor cells (CTCs) in 7.5 ml blood is a poor prognostic marker in metastatic breast cancer (MBC). However, the role of human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) status in CTCs is not known.

Methods

We prospectively assessed the prognostic value of this parameter for patients with MBC who started a new line of systemic therapy. The CTC count (≥5 or <5) and the HER2 status in CTCs at the initiation of the therapy and 3–4 weeks later (first follow-up) were determined.

Results

The median follow-up time of the 52 enrolled patients was 655.0 days (18–1,275 days). HER2-positive CTCs were present in 14 of the 52 patients (26.9%) during the study period. Eight of 33 patients (24.2%) with HER2-negative primary tumors had HER2-positive CTCs during the study period. At first follow-up, patients with HER2-positive CTCs had significantly shorter progression-free (n = 6; P = 0.001) and overall (P = 0.013) survival than did patients without HER2-positive CTCs (n = 43) in log-rank analysis. In multivariate analysis, HER2-positive CTCs at first follow-up (P = 0.029) and the number of therapies patients received before this study (P = 0.006) were independent prognostic factors in terms of progression-free survival. The number of therapies (P = 0.001) and a count of ≥5 CTCs (P = 0.043) at baseline were independent prognostic factors in terms of overall survival.

Conclusions

We showed that HER2 status in CTCs may be a prognostic factor for MBC. Well-powered prospective studies are necessary to determine the potential role of HER2-targeted therapies for patients with HER2-positive CTCs and HER2-negative primary tumors.

Keywords: Circulating tumor cell, Breast neoplasm, HER2, Metastasis

Introduction

Despite the development of new agents, metastatic breast cancer (MBC) remains an incurable disease and a main cause of cancer death among women. An estimated 11,177 women in in Japan in 2006 [1] and 40,170 women in the United States in 2009 [2] died of breast cancer. Better means of assessing patient prognosis would aid in appropriate treatment planning and monitoring MBC. Serum tumor markers, such as carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) and cancer antigen 15-3 (CA15-3), are commonly used to monitor treatment effectiveness in clinical practice [3–9]. However, they are insufficient for predicting prognosis and do not provide therapeutic targets for improving prognosis. The detection of circulating tumor cells (CTCs) in peripheral blood is an independent predictor of the efficacy of systemic therapy and a prognostic marker in patients with MBC [10–15]. In 2004, Cristofanilli et al. [11] reported that in patients diagnosed with measurable MBC, progression-free (PFS) and overall (OS) survival for patients with ≥5 CTCs per 7.5 ml peripheral blood (measured before initiation of a new line of therapy and at the first follow-up visit) were significantly shorter than for those in patients with<5 CTCs. Follow-up studies clarified the predictive value of CTCs for identifying chemotherapy-resistant patients, enabling earlier adjustment of therapy [10, 12, 13].

The expression of human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) in CTCs was recently evaluated [16–20]. Interestingly, discordance in HER2 status between primary tumors and CTCs from the same patients was reported [17, 18, 20]: 5.0–38.0% of patients with HER2-negative primary breast cancers had HER2 overexpression in CTCs; however, the prognostic value of HER2 overexpression in CTCs for patients with HER2-negative primary breast cancer has not been determined. The purpose of this prospective study was to assess the prognostic value of HER2 status in CTCs in patients with MBC.

Materials and methods

Patients and sample collection

Fifty-six women with newly diagnosed MBC and started on systemic therapy or who changed to a new line of therapy because of disease progression were enrolled in this prospective study at St. Luke’s International Hospital, Tokyo, Japan. The institutional review board approved the study protocol, and all patients gave informed consent. Inclusion criteria were as follows: invasive breast carcinoma diagnosed by histopathological findings, distant metastatic disease detected radiologically and/or pathologically, and HER2 status in the primary tumor confirmed. Patients with only local recurrences, skin metastases, and bilateral breast cancers were excluded. HER2 overexpression in the primary tumor was defined as a HercepTest score of 3+ or 2+ by immunohistochemical analysis using Ventana PATHWAY anti-HER2/neu (4B5) rabbit monoclonal antibody and recognized HER2 gene amplification by fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) analysis. Primary tumor HER2 expression was determined by hospital pathologists. Blood specimens were collected at the initiation of the new line of therapy and at 3- to 4-week intervals up to 12 weeks. Patients remained in this study until their disease progressed and therapy was changed or until they died. Clinicians and patients were blinded to results of CTC counts. Before therapy initiation and after 12 weeks, computed tomography (CT) scans were performed to assess patients’ radiological response to therapy. Response was determined by oncologists and radiologists according to the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) [21].

Isolation, enumeration, and HER2 evaluation of CTCs

CTCs were counted using the CellSearch System (Veridex, LLC), an automated method cleared by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and used for clinical monitoring in patients with MBC. First, patient blood samples were drawn into CellSave Preservative Tubes (Veridex). Samples were maintained at room temperature and processed within 72 h after collection. The CellTracks Auto-Prep System, a semiautomated instrument for the preparation of samples, was used with the CellSearch Epithelial Cell Kit (Veridex) and Tumor Phenotyping Reagent HER2/neu (Veridex). CTCs were enriched immunomagnetically from 7.5 ml of blood using ferrofluids coated with antibodies targeting the epithelial cell adhesion molecule. Isolated cells were fluorescently labeled with the nucleic acid dye 4,2-diamidino-2-phenylindole dihydrochloride (DAPI), monoclonal antibodies specific for leukocytes (CD45 labeled with allophycocyanin), and epithelial cells (cytokeratins [10] 8, 18, and 19 labeled with phycoerythrin) to distinguish epithelial cells from leukocytes [11]. Epithelial cells were also examined for staining with a monoclonal antibody (HER81) specific for HER2 (HER2 labeled with fluorescein isothiocyanate). Identification and enumeration of CTCs were performed using the CellTracks Analyzer II, a semiautomated fluorescence-based microscopy system. Automatically selected images were reviewed independently by two operators for CTC identification. A third operator checked the selected images when the first two operators’ results had discrepancies. CTCs were defined as nucleated cells that lacked CD45 and expressed creatine kinase (CK). Nucleated cells that expressed both CK and HER2 and lacked CD45 were defined as HER2-positive CTCs. For technical assessment, immunostaining was performed using HER2 antibody on SKBR-3 and MCF-7 cell lines. The strong staining detected in SKBR-3 cells (known to express high levels of HER2) was obviously different from the weak staining in MCF-7 cells (known to express low levels of HER2). Thus, strong staining of CTCs was defined as HER2 positivity.

After removal from the cartridge, cells were fixed on the slide glass. FISH was performed with centromeric alpha-satellite DNA probes for chromosome 17 (CEP17) and with probes for the HER2 gene at chromosome 17q [22]. The copy numbers of HER2 gene and CEP17 sequences for each cell were determined with a magnification 1,000× using an Olympus fluorescence microscope with a triple-band-pass filter. Data were analyzed in terms of both gene amplification and copy number change (increase or decrease in copy numbers). HER2 gene amplification was defined as ≥2.0 for the ratio of HER2 copy number to CEP17 copy number [18]. A maximum of 50 cells per sample were examined for HER2 amplification by FISH. Patients were diagnosed as having HER2-positive CTCs when they had at least one CTC in which HER2 was overexpressed and/or amplified.

Statistical analysis

Progression-free survival (PFS) was measured from the start date of systemic therapy or change to a new line of therapy to the date of first progression or last follow-up. Overall survival was measured to the date of death or to the date of last follow-up. PFS and OS were estimated with the Kaplan–Meier method and compared between groups using the log-rank statistic. Cox proportional hazards models were fit to determine the association of clinicopathologic factors with the risk of progression and death after adjustment for other patient and disease characteristics. Each model contained terms for age at diagnosis, presence of lymph node metastases at diagnosis, and HER2 and hormone receptor status in primary tumor. We calculated the sample size of HER2-positive CTCs to detect 35% difference in OS at 5% type-1 error and 80% power. Because there was no previous clinical study for HER2-positive CTCs, we referred the difference of 1 year survival rate between ≥5 CTCs and <5 CTCs at first follow-up in a previous study [12] and the expression rate of HER2 in primary tumors. A two-tailed P value<0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were done using SPSS version 17 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

Patient characteristics

Of the original 56 patients enrolled, four were not included in analysis: one patient refused to undergo testing, one underwent surgery to control local bleeding, and two identified a history of contralateral breast cancer after enrolling in the study. Characteristics of the remaining 52 patients with MBC who started a new line of therapy are summarized in Table 1. Forty-one patients (78.8%) had undergone surgery, whereas 11 patients had not because of the presence of metastatic disease at the time of diagnosis (de novo stage IV).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| Patient history | Number of patients |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | |

| Median | 54.1 |

| Range | 32–74 |

| Follow-up (days) | |

| Median | 655.0 |

| Range | 18–1275 |

| Estrogen, progesterone receptor status | |

| Positive for either | 33 |

| Negative for both | 19 |

| HER2/neu status in primary tumor | |

| Positive (3+, 2+/FISH+) | 19 |

| Negative (0, 1+, 2+/FISH−) | 33 |

| Therapy given in this study | |

| 1st line | 20 |

| 2nd line | 6 |

| 3rd line or higher | 26 |

| Type of therapy initiated at the time of registration | |

| Hormone alone | 6 |

| Hormone and chemotherapy | 6 |

| Chemotherapy alone | 22 |

| Chemotherapy and HER2-targeting agent | 16 |

| Trastuzumab | 15 |

| Lapatinib | 1 |

| Trastuzumab alone | 1 |

| Sunitinib alone | 1 |

| History of operation | |

| Yes | 41 |

| No | 11 |

| Therapy response at 12 weeks | |

| Partial response | 21 |

| Stable disease | 10 |

| Progressive disease | 21 |

| Survival status at end of follow-up | |

| Alive | 36 |

| Dead | 16 |

HER2 human epidermal growth factor receptor 2, FISH fluorescence in situ hybridization

Median follow-up to determine OS was 655.0 (range 18–1,275) days. Two patients died before the first follow-up (3–4 weeks after the initiation of therapy), one died before the second follow-up (8–9 weeks after the initiation of therapy), and one died before the last follow-up (12 weeks after the initiation of therapy); all four died of multiple liver metastases. Twelve patients died after the last follow-up. One patient’s blood sample was not examined at the first follow-up. Radiographic tumor assessment showed that at 12 weeks, 21 patients had partial response, ten had stable disease, and 21 had progressive disease. The number of therapies patients received before this study was associated with PFS (P = 0.017) and OS (P = 0.006) in Cox regression analysis. Patient age, HER2 status, hormone receptor status, primary tumor size, and lymph node status were not statistically associated with PFS and OS (Tables 2, 3).

Table 2.

Predictors of progression-free survival in univariate and multivariate analysis in Cox regression analysis

| Characteristic | Univariate analysis

|

Multivariate analysis

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P (Cox) | HR | 95% CI

|

P (Cox) | HR | 95% CI

|

|||

| Lower | Upper | Lower | Upper | |||||

| Age, years ( <50 vs. ≥50) | 0.155 | 0.653 | 0.363 | 1.175 | – | – | – | – |

| Tumor size | 0.653 | 0.938 | 0.711 | 1.239 | – | – | – | – |

| Lymph node metastases (positive vs. negative) | 0.328 | 0.721 | 0.375 | 1.387 | – | – | – | – |

| HER2 status (positive vs. negative) | 0.654 | 1.072 | 0.789 | 1.457 | – | – | – | – |

| Hormone receptor status (positive vs. negative) | 0.859 | 0.947 | 0.517 | 1.734 | – | – | – | – |

| Number of CTCs at baseline (<5 vs. ≥5) | 0.049 | 1.867 | 1.003 | 3.476 | 0.195 | 1.656 | 0.773 | 3.550 |

| Number of CTCs at 1st follow up (<5 vs. ≥5) | 0.020 | 2.627 | 1.161 | 5.946 | – | – | – | – |

| HER2-positive CTCs at baseline | 0.805 | 1.107 | 0.494 | 2.482 | – | – | – | – |

| HER2-positive CTCs at 1st follow up | 0.002 | 4.071 | 1.640 | 10.108 | 0.029 | 3.026 | 1.120 | 8.172 |

| Number of therapies | 0.017 | 1.196 | 1.032 | 1.386 | 0.006 | 1.252 | 1.065 | 1.472 |

CI confidence interval, HR hazard ratio, CTCs circulating tumor cells, HER2 human epidermal growth factor receptor 2

Table 3.

Predictors of overall survival in univariate and multivariate analyses in Cox regression analysis

| Characteristic | Univariate analysis

|

Multivariate analysis

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P (Cox) | HR | 95% CI

|

P (Cox) | HR | 95% CI

|

|||

| Lower | Upper | Lower | Upper | |||||

| Age, years ( <50 vs. ≥50) | 0.643 | 0.843 | 0.409 | 1.738 | – | – | – | – |

| Tumor size | 0.406 | 1.150 | 0.827 | 1.598 | – | – | – | – |

| Lymph node metastases (positive vs. negative) | 0.922 | 0.962 | 0.446 | 2.074 | – | – | – | – |

| HER2 status (positive vs. negative) | 0.148 | 1.333 | 0.903 | 1.968 | – | – | – | – |

| Hormone receptor status (positive vs. negative) | 0.891 | 1.053 | 0.504 | 2.200 | – | – | – | – |

| Number of CTCs at baseline (<5 vs. ≥5) | 0.033 | 2.175 | 1.063 | 4.453 | 0.043 | 2.443 | 1.028 | 5.809 |

| Number of CTCs at 1st follow up (<5 vs. ≥5) | 0.010 | 3.096 | 1.313 | 7.302 | – | – | – | – |

| HER2-positive CTCs at baseline | 0.677 | 1.226 | 0.470 | 3.193 | – | – | – | – |

| HER2-positive CTCs at 1st follow up | 0.019 | 3.210 | 1.212 | 8.502 | 0.180 | 2.023 | 0.722 | 5.669 |

| Number of therapies | 0.006 | 1.253 | 1.067 | 1.471 | 0.001 | 1.349 | 1.126 | 1.616 |

CI confidence interval, HR hazard ratio, CTCs circulating tumor cells, HER2 human epidermal growth factor receptor 2

Circulating tumor cell counts

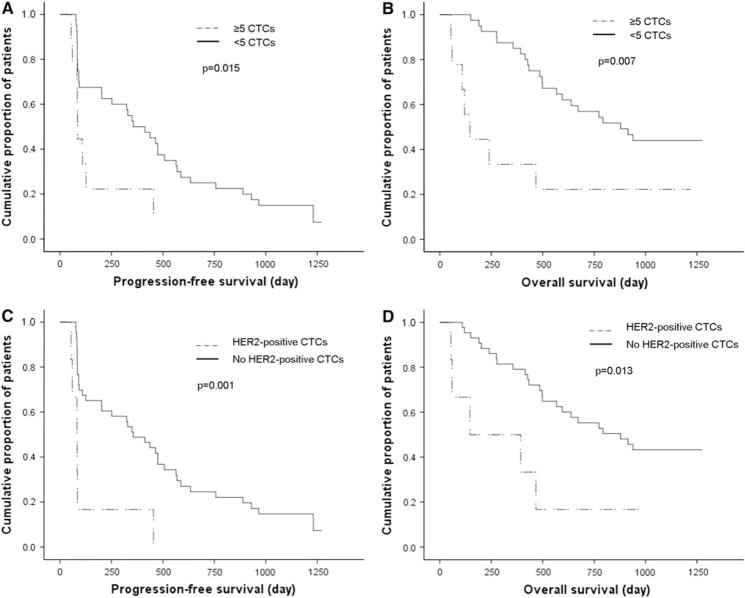

In 40 of 52 patients (76.9%), at least one CTC was detected during the study period. CTCs were detected in 31 of 52 patients (59.6%) at baseline and in 21 of 49 patients (42.9%) at first follow-up; two patients who died and one whose blood was not examined were excluded from the latter analysis. Mean CTC count of the 52 patients at baseline was six (median 304; range 0–6,067). At baseline, ≥5 CTCs was associated with a significantly shorter PFS (n = 18; median 91.0 days; P = 0.044) and OS (median 356.0 days; P = 0.029) duration compared with that for patients with a count of <5 CTCs (n = 34; median 437.0 days, and median 915.0 days, respectively) in log-rank analysis. At first follow-up, a count of ≥5 CTCs was associated with a significantly shorter PFS (n = 9; median 85.0 days; P = 0.015) and OS (median 146.0 days; P = 0.007) duration compared with that for patients with a count of<5 CTCs (n = 40; median 356.0 days, and median 878.0 days, respectively) (Fig. 1a, b).

Fig. 1.

Kaplan–Meier functions of a progression-free survival (PFS) in patients with ≥5 circulating tumor cells (CTCs) (n = 9) and patients with <5 CTCs (n = 40) at first follow-up (log-rank P = 0.015), b overall survival (OS) in patients with ≥5 CTCs (n = 9) and patients with <5 CTCs (n = 40) at first follow-up (log-rank P = 0.007), c PFS in patients with human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)-positive CTCs (n = 6) and patients without HER2-positive CTCs (n = 43) at first follow-up (log-rank P = 0.001), and d )S in patients with HER2-positive CTCs (n = 6) and patients without HER2-positive CTCs (n = 43) at first follow-up (log-rank P = 0.013)

HER2 expression in CTCs

We further assessed the prognostic value of HER2 status in CTCs. Changes in CTC counts and HER2 status in CTCs are shown in Table 4. At baseline, HER2-positive CTCs were present in eight patients (15.4%) and HER2-negative CTCs in 23 patients (44.2%). HER2-positive CTCs were diagnosed in eight patients by FISH and five by immunocytochemistry (ICC). Fourteen of 52 patients (26.9%) had HER2-positive CTCs during the study period. We observed a change of HER2 status in CTCs at the first follow-up. Among the eight patients with HER2-positive CTCs at baseline, at the first follow-up, three still had HER2-positive CTCs, four no longer had HER2-positive CTCs, and one was not assessed because she had died. In contrast, among 23 patients with HER2-negative CTCs at baseline, three had HER2-positive CTCs at the first follow-up, whereas 20 still did not have HER2-positive CTCs. One patient without CTCs at baseline had acquired HER2-negative CTCs at first follow-up. Of the six patients with HER2-positive CTCs at first follow-up, five were by FISH and three by ICC.

Table 4.

Changes in circulating tumor cell (CTC) count and in human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) status in CTCs from baseline to first follow-up

| Baseline

|

First follow-up

|

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HER2 status in CTCs | No. of patients (%) | No. of CTCs

|

HER2 status in CTCs | No. of patients (%) | No. of CTCs

|

||||||

| Total | HER2 overexpressed by ICC | Examined by FISH | HER2 amplified by FISH | Total | HER2 overexpressed by ICC | Examined by FISH | HER2 amplified by FISH | ||||

| Positive | 8 (15.4) | 6,067 | 0 | 50 | 6 | Positive | 3 (5.8) | 1,938 | 0 | 50 | 6 |

| 1,128 | 0 | 50 | 2 | 1,100 | 0 | 50 | 3 | ||||

| 220 | 118 | 50 | 50 | 10 | 3 | 7 | 3 | ||||

| 56 | 0 | 40 | 3 | Negative | 2 (3.8) | 4 | 0 | 2 | 0 | ||

| 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| 1,577 | 1119 | 50 | 50 | No CTCs | 2 (3.8) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 7 | 2 | 5 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| 15 | 3 | 10 | 1 | NA | 1 (1.9) | NA | NA | NA | NA | ||

| Negative | 23 (44.2) | 13 | 0 | 9 | 0 | Positive | 3 (5.8) | 39 | 0 | 27 | 1 |

| 12 | 0 | 14 | 0 | 12 | 1 | 7 | 0 | ||||

| 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 1 | ||||

| 97 | 0 | 50 | 0 | Negative | 12 (23.1) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 76 | 0 | 50 | 0 | 26 | 0 | 18 | 0 | ||||

| 50 | 0 | 35 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | ||||

| 43 | 0 | 30 | 0 | 44 | 0 | 30 | 0 | ||||

| 12 | 0 | 10 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | ||||

| 11 | 0 | 7 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| 10 | 0 | 8 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 3 | 0 | ||||

| 3 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | ||||

| 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 3 | 0 | ||||

| 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 19 | 0 | 13 | 0 | ||||

| 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| 6 | 0 | 4 | 0 | No CTCs | 8 (15.4) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 4 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| 3 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| No CTCs | 21 (40.4) | Negative | 1 (1.9) | 4 | 0 | 2 | 0 | ||||

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | No CTCs | 18 (34.7) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| NA | 2 (3.8) | NA | NA | NA | NA | ||||||

HER2 human epidermal growth factor receptor 2, CTCs circulating tumor cells, FISH fluorescence in situ hybridization, ICC immunocytochemistry, NA not assessed

At baseline, HER2-positive CTCs were not associated with PFS (P = 0.804) or OS duration (P = 0.676). However, at first follow-up, patients with HER2-positive CTCs had a significantly shorter PFS (n = 6; median 146.0 days; P = 0.001) and OS (median 146.0 days; P = 0.013) duration than did patients without HER2-positive CTCs (n = 43; median 878.0 and 356.0 days, respectively) (Fig. 1c, d). In multivariate analysis, HER2-positive CTCs at first follow-up (P = 0.029) and the number of therapies patients received before this study (P = 0.006) were independent factors in terms of PFS (Table 2). The number of therapies (P = 0.001) and ≥5 CTCs (P = 0.043) at baseline were independent factors in terms of OS (Table 3).

We assessed concordance of HER2 status between primary tumors and CTCs among patients with CTCs. At baseline, three of 22 patients (13.6%) with HER2-negative primary tumors had HER2-positive CTCs. In contrast, four of nine patients (44.4%) with HER2-positive primary tumors had HER2-negative CTCs (Table 5). Six of 19 patients (31.6%) with HER2-positive primary tumors had HER2-positive CTCs during the study period. Five of the six patients received trastuzumab. Eight of 33 patients (24.2%) with HER2-negative primary tumors had HER2-positive CTCs. None of these eight patients received trastuzumab. One patient with HER2-positive CTCs who received trastuzumab died. On the other hand, six of nine patients (66.7%) with HER2-positive CTCs who did not receive trastuzumab died.

Table 5.

Correlation of human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) status between primary tumors and circulating tumor cells (CTCs) at the time of study entry

| Study | HER2 testing method | Patients

|

Patients with discordant CTC HER2 status

|

Prognostic value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. with CTCs | No. with HER2-positive CTCs | % | No. with HER2-negative primary tumors and HER2-positive CTCs | % | No. with HER2-positive primary tumors and HER2-negative CTCs | % | |||

| Metastatic breast cancer | |||||||||

| Hayashi et al. | ICC and FISH | 31 | 8 | 25.8 | 3/22 | 13.6 | 4/9 | 44.4 | OS and PFS |

| Pestrin et al. [20] | FISH | 40 | 15 | 37.5 | 8/28 | 28.6 | 5/12 | 41.7 | NA |

| Tewes et al. [27] | RT-PCR | 22 | 7 | 31.8 | 5/17 | 29.4 | 3/5 | 60.0 | NA |

| Fehm et al. [17] | FISH or RT-PCR | 21 | 8 | 38.1 | 2/10 | 20.0 | 4/5 | 80.0 | NA |

| Meng et al. [18] | FISH | 33 | 11 | 33.3 | 0/18 | 0 | 4/15 | 26.7 | NA |

| Early breast cancer | |||||||||

| Apostolaki et al. [23] | RT-PCR | NA | 52 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | OS and DFS |

| Ignatiadis et al. [25] | RT-PCR | 77 | 50 | 64.9 | NA | NA | NA | NA | OS and DFS |

| Wulfing et al. [19] | ICC | 27 | 17 | 63.0 | 12/24 | 50.0 | 1/3 | 33.3 | DFS |

| Riethdorf et al. [26] | ICC and FISH | 46 | 8/37 | 21.6 | 5/26 | 19.2 | 5/11 | 45.5 | NA |

| Fehm et al. [24] | FISH or RT-PCR | 58 | 22 | 37.9 | 22/49 | 44.9 | 0/9 | 0 | NA |

ICC immunocytochemistry, FISH fluorescence in situ hybridization, RT-PCR reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction, NA not assessed OS overall survival, PFS progression-free survival, DFS disease-free survival

Discussion

We prospectively demonstrated that HER2-positive CTCs predicted a worse prognosis in MBC and thus that HER2 status in CTCs may serve as a prognostic factor. Our results also showed that HER2-positive CTCs can be present in patients with HER2-negative primary tumors. Our results confirmed Cristofanilli et al.’s landmark finding of CTC count as a prognostic factor [11–15]. Table 5 summarizes previous studies that evaluated HER2 expression status in CTCs [17–20, 23–27]. Many previous studies evaluated HER2 by reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) or FISH, and in these studies, HER2-positive CTCs were detected in 21.6–64.9% of patients with CTCs. HER2-positive CTCs were detected in 19.2–50% of patients with HER2-negative primary breast tumors [19, 23–26] and 0–29% of patients with MBC who had HER2-negative primary tumors [17, 18, 20, 27]. We evaluated HER2 status in CTCs by both ICC and FISH because the method of determining HER2 expression status in CTCs has not been standardized. Our findings concur with these previous results.

Our study is the first to examine the prognostic role of HER2-positive CTCs in patients with MBC. Three studies in which the presence and frequency of HER2-positive CTCs correlated with significantly decreased disease-free and OS durations [19, 23, 25] were conducted in patients with primary breast cancer. Previous studies of prognosis compared patients with HER2-positive CTCs to patients with HER2-negative CTCs or without CTCs at baseline only. The other unique aspect of our study is that we evaluated prognosis by comparing patients with HER2-positive and HER2-negative CTCs at baseline and also at first follow-up; thus, the change in CTC HER2 status was considered. At first follow-up a count of ≥5 CTCs and HER2-positive CTCs were significantly associated with PFS and OS in univariate analysis. Because HER2 positivity in CTCs depended on CTC counts, the prognostic role of HER2-positive CTCs would be statistically interfered by a count of ≥5 CTCs in multivariate analysis. Therefore, we included HER2-positive CTCs only to determine the independent factors. We demonstrated that HER2-positive CTCs not at baseline but at first follow-up were associated with PFS. This result indicates that HER2-positive CTCs at first follow-up predict resistance to treatment. Therefore, the presence of HER2-positive CTCs at first follow-up may suggest early change of treatment. In terms of OS, a ≥5 CTCs at baseline was an independent factor rather than HER2-positive CTCs.

The presence of HER2-positive CTCs may be a prognostic factor regardless of primary tumor HER2 status. Notably, five of eight patients with HER2-negative primary tumors and HER2-positive CTCs died during the follow-up period. Furthermore, four of those patients died within 144 days of initiation of therapy. In contrast, three of four patients with HER2-positive CTCs who received trastuzumab because of their HER2-positive primary tumors lost HER2 overexpression in CTCs; the fourth patient died of multiple liver metastases 31 days after the initiation of therapy. Meng et al. [18] retrospectively reported that two of four patients with HER2-positive CTCs and HER2-negative primary tumors who were treated with trastuzumab-containing chemotherapy responded. These significant data clearly suggest the need to develop prospective studies to determine the potential role of trastuzumab or other HER2-targeted therapies for patients with HER2-positive CTCs and HER2-negative primary tumors.

One other note is that we used different antibodies to detect HER2 expression in CTCs and primary tumors. These antibodies were selected to make sure that we could compare our results with those of previous studies because the antibody for CTCs was used in previous studies [17, 18, 24, 26]. There is a small possibility that the use of different antibodies might have caused discrepant positivity between CTCs and primary tumors.

In summary, we believe that the finding of the prognostic value of HER2-positive CTCs at first follow-up of patients with HER2-negative MBC is of critical relevance in a population with poor prognosis that is treated with palliative intent. We plan to perform additional, well-powered, clinical studies to evaluate the discordance of HER2 status among patients’ primary tumors and CTCs and to assess the potential of additional HER2-targeting therapy.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Sachiko Ohde for statistical assistance; Bibari Nakamura, Keiko Shimizu, and all the staff from the Department of Breast Surgical Oncology, St. Luke’s International Hospital, for help in collecting clinical data; Masayuki Shimada, Takeshi Watanabe, and Yuki Matsuo from SRL Inc. for tissue analysis; and Sunita Patterson, Department of Scientific Publications, MD Anderson Cancer Center, for editorial review. This research is supported in part by the National Institutes of Health through MD Anderson’s Cancer Center Support Grant, CA016672.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest Yuji Shimoda is employed by SRL Inc., and SRL Inc. provided analysis of serum HER2 level in the blood samples at St. Luke’s International Hospital (Hayashi N, Nakamura S, Yoshida A, and Yagata H). All other coauthors have no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Naoki Hayashi, Department of Breast Medical Oncology, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, 1515 Holcombe Boulevard Unit 1354, Houston, TX 77030, USA. Department of Breast Surgical Oncology, St. Luke’s International Hospital, 9-1 Akashi-cho, Chuo-ku, Tokyo 104-8560, Japan. Second Department of Pathology, The Showa University School of Medicine, 1-5-8 Hatanodai, Shinagawa-ku, Tokyo 142-8555, Japan.

Seigo Nakamura, Department of Breast Surgical Oncology, St. Luke’s International Hospital, 9-1 Akashi-cho, Chuo-ku, Tokyo 104-8560, Japan. Department of Breast Surgical Oncology, The Showa University School of Medicine, 1-5-8 Hatanodai, Shinagawa-ku, Tokyo 142-8555, Japan.

Yasuharu Tokuda, Institute of Clinical Medicine, Graduate School of Comprehensive Human Sciences, University of Tsukuba, 1-1-1 Tennodai, Tsukuba, Ibaraki 305-8577, Japan.

Yuji Shimoda, Research and Development Department, SRL Inc., 5-6-50 Shin-machi, Hino, Tokyo 191-0002, Japan.

Hiroshi Yagata, Department of Breast Surgical Oncology, St. Luke’s International Hospital, 9-1 Akashi-cho, Chuo-ku, Tokyo 104-8560, Japan.

Atsushi Yoshida, Department of Breast Surgical Oncology, St. Luke’s International Hospital, 9-1 Akashi-cho, Chuo-ku, Tokyo 104-8560, Japan.

Hidekazu Ota, Second Department of Pathology, The Showa University School of Medicine, 1-5-8 Hatanodai, Shinagawa-ku, Tokyo 142-8555, Japan.

Gabriel N. Hortobagyi, Department of Breast Medical Oncology, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, 1515 Holcombe Boulevard Unit 1354, Houston, TX 77030, USA

Massimo Cristofanilli, Department of Medical Oncology, Fox Chase Cancer Center, 333 Cottman Avenue, Philadelphia, PA 19111-2497, USA.

Naoto T. Ueno, Email: nueno@mdanderson.org, Department of Breast Medical Oncology, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, 1515 Holcombe Boulevard Unit 1354, Houston, TX 77030, USA

References

- 1.Ministry of Health Law. Vital statistics of Japan. 2008 Available from http://www.mhlw.go.jp/english/database/db-hw/vs01.html.

- 2.Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, et al. Cancer statistics, 2009. CA Cancer J Clin. 2009;59:225–249. doi: 10.3322/caac.20006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bartsch R, Wenzel C, Pluschnig U, et al. Prognostic value of monitoring tumour markers CA 15-3 and CEA during fulve-strant treatment. BMC Cancer. 2006;6:81. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-6-81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cheung KL, Graves CR, Robertson JF. Tumour marker measurements in the diagnosis and monitoring of breast cancer. Cancer Treat Rev. 2000;26:91–102. doi: 10.1053/ctrv.1999.0151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Duffy MJ. Serum tumor markers in breast cancer: are they of clinical value? Clin Chem. 2005;52:345–351. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2005.059832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Khatcheressian JL, Wolff AC, Smith TJ, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology 2006 update of the breast cancer follow-up and management guidelines in the adjuvant setting. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:5091–5097. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.8575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kurebayashi J, Nishimura R, Tanaka K, et al. Significance of serum tumor markers in monitoring advanced breast cancer patients treated with systemic therapy: a prospective study. Breast Cancer. 2004;11:389–395. doi: 10.1007/BF02968047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tampellini M, Berruti A, Bitossi R, et al. Prognostic significance of changes in CA 15-3 serum levels during chemotherapy in metastatic breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2006;98:241–248. doi: 10.1007/s10549-005-9155-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tondini C, Hayes DF, Gelman R, et al. Comparison of CA15-3 and carcinoembryonic antigen in monitoring the clinical course of patients with metastatic breast cancer. Cancer Res. 1988;48:4107–4112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cristofanilli M, Broglio KR, Guarneri V, et al. Circulating tumor cells in metastatic breast cancer: biologic staging beyond tumor burden. Clin Breast Cancer. 2007;7:471–479. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cristofanilli M, Budd GT, Ellis MJ, et al. Circulating tumor cells, disease progression, and survival in metastatic breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:781–791. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cristofanilli M, Hayes DF, Budd GT, et al. Circulating tumor cells: a novel prognostic factor for newly diagnosed metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:1420–1430. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.08.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hayes DF, Cristofanilli M, Budd GT, et al. Circulating tumor cells at each follow-up time point during therapy of metastatic breast cancer patients predict progression-free and overall survival. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:4218–4224. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-2821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nakamura S, Yagata H, Ohno S, et al. Multi-center study evaluating circulating tumor cells as a surrogate for response to treatment and overall survival in metastatic breast cancer. Breast Cancer. 2010;17:199–204. doi: 10.1007/s12282-009-0139-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yagata H, Nakamura S, Toi M, et al. Evaluation of circulating tumor cells in patients with breast cancer: multi-institutional clinical trial in Japan. Int J Clin Oncol. 2008;13:252–256. doi: 10.1007/s10147-007-0748-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Apostolaki S, Perraki M, Pallis A, et al. Circulating HER2 mRNA-positive cells in the peripheral blood of patients with stage I and II breast cancer after the administration of adjuvant chemotherapy: evaluation of their clinical relevance. Ann Oncol. 2007;18:851–858. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdl502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fehm T, Becker S, Duerr-Stoerzer S, et al. Determination of HER2 status using both serum HER2 levels and circulating tumor cells in patients with recurrent breast cancer whose primary tumor was HER2 negative or of unknown HER2 status. Breast Cancer Res. 2007;9:R74. doi: 10.1186/bcr1783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meng S, Tripathy D, Shete S, et al. HER-2 gene amplification can be acquired as breast cancer progresses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:9393–9398. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402993101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wulfing P, Borchard J, Buerger H, et al. HER2-positive circulating tumor cells indicate poor clinical outcome in stage I to III breast cancer patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:1715–1720. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-2087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pestrin M, Bessi S, Galardi F, et al. Correlation of HER2 status between primary tumors and corresponding circulating tumor cells in advanced breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2009;118:523–530. doi: 10.1007/s10549-009-0461-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Therasse P, Arbuck SG, Eisenhauer EA, et al. New guidelines to evaluate the response to treatment in solid tumors. European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer, National Cancer Institute of the United States, National Cancer Institute of Canada. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:205–216. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.3.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shimada M, Imura J, Kozaki T, et al. Detection of Her2/ neu, c-MYC and ZNF217 gene amplification during breast cancer progression using fluorescence in situ hybridization. Oncol Rep. 2005;13:633–641. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Apostolaki S, Perraki M, Kallergi G, et al. Detection of occult HER2 mRNA-positive tumor cells in the peripheral blood of patients with operable breast cancer: evaluation of their prognostic relevance. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2009;117:525–534. doi: 10.1007/s10549-008-0239-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fehm T, Hoffmann O, Aktas B, et al. Detection and characterization of circulating tumor cells in blood of primary breast cancer patients by RT-PCR and comparison to status of bone marrow disseminated cells. Breast Cancer Res. 2009;11:R59. doi: 10.1186/bcr2349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ignatiadis M, Kallergi G, Ntoulia M, et al. Prognostic value of the molecular detection of circulating tumor cells using a multimarker reverse transcription-PCR assay for cytokeratin 19, mammaglobin A, and HER2 in early breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:2593–2600. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-4758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Riethdorf S, Muller V, Zhang L, et al. Detection and HER2 expression of circulating tumor cells: prospective monitoring in breast cancer patients treated in the Neoadjuvant GeparQuattro Trial. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:2634–2645. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-2042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tewes M, Aktas B, Welt A, et al. Molecular profiling and predictive value of circulating tumor cells in patients with metastatic breast cancer: an option for monitoring response to breast cancer related therapies. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2009;115:581–590. doi: 10.1007/s10549-008-0143-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]