Abstract

Introduction

Large congenital nevi carry a slightly increased risk for the development of melanoma. Pregnancy poses an additional challenge in monitoring these patients as little is known regarding the effects of increased estrogen levels on congenital nevi.

Observation

A young woman was observed to have clinical lightening of her garment nevus and satellite nevi during two sequential pregnancies. Post-partum, the patient experienced darkening and re-pigmentation within her large garment nevus, with continued lightening of nearby satellite lesions. In addition to photographic documentation of these changes, biopsies taken during pregnant and non-pregnant periods were evaluated with immunohistochemistry for estrogen receptor beta (ERβ), the predominant estrogen receptor in nevi and melanomas. Biopsies taken during pregnancy showed a decrease in nuclear staining for ERβ when compared to biopsies taken following pregnancy. These changes in ERβ expression were not associated with histological atypia either during pregnancy or following delivery.

Conclusion

Congenital nevi may be unique in their response to altered estrogen levels. Given the slightly increased risk for the development of melanoma in giant congenital nevi and the dearth of information available regarding the effects of pregnancy on congenital nevi, this case illustrates the need for further study of these pigmented lesions.

Keywords: congenital nevi, pregnancy, estrogen receptor β, immunohistochemistry

Introduction

Congenital nevi are nevi present at birth or shortly thereafter, formed by the aberrant proliferation of melanocytes. These nevi, though typically benign, carry a slightly increased risk for the development of melanoma, particularly in the large, garment nevi greater than 20 cm in size (1–5). Patients with garment nevi may develop melanomas at a younger age (1). Additional risk factors associated with the development of a melanoma within a large congenital nevus include size covering half or more of the total body surface area, involvement of the back, as well as the presence of satellite lesions (1). Due to the large size and extent of cutaneous involvement, complete excision of large congenital nevi is often not possible. In addition, non-epidermal melanoma has developed in patients following dermabrasion and partial or complete excision of large congenital nevi (1, 4).

ERβ has been shown to potentially have a tumor suppressive effect in a variety of human tumors such as breast, prostate, colon, and ovarian cancers (Reviewed in 6). This is usually thought to be through suppression of the action of ERα. We have previously found high levels of ERβ in severely dysplastic nevi and melanoma-in-situ, with a progressive loss of ERβ with increasing depth of melanomas (7). We therefore have postulated that ERβ also has a suppressant effect in melanoma.

Pregnancy poses an additional challenge for monitoring these patients as the role of pregnancy and the development of melanoma remains controversial. While many women describe skin changes such as hyperpigmentation and melasma, along with nevus darkening and enlargement during pregnancy, the exact role of increased systemic estrogen on nevi remains unclear (8–10). Even less is known regarding the effects of pregnancy and estrogen on congenital nevi. It might be assumed that congenital nevi, acting similar to reports of benign and atypical nevi, may darken or enlarge during pregnancy (8–10). However, there are only a few documented case reports regarding the specific changes that take place in congenital nevi during pregnancy. Herein, we report a case of a young woman with a giant congenital nevus who developed clinical lightening of her garment nevus, as well as various satellite nevi, during pregnancy with darkening of nevus pigmentation following parturition. We also evaluated the patient’s nevi with immunohistochemistry for estrogen receptor β (ERβ) while pregnant and following pregnancy since ERβ is the predominant estrogen receptor found in nevi and malignant melanomas (7, 11). This revealed a decrease in expression of ERβ with pregnancy compared to that observed following parturition. The ERβ levels from the nevi of this patient have been averaged in a larger congenital nevi data set (11), however, the clinical course with photography and detailed immunohistochemistry findings has not been previously presented.

Case Report

A 23-year old Caucasian woman with a large bathing trunk nevus and multiple satellite nevi covering nearly her entire cutaneous surface has been followed in the Vanderbilt University Pigmented Lesion Clinic for 18 years, beginning at age 5. Clinically, the pigmentation levels within her congenital nevi had remained stable throughout the years including her entrance into puberty. Curiously, the pigmentation levels changed when the patient became pregnant with her first child. Clinical examination at the time revealed diffuse lightening of the patient’s large garment nevus. Similarly, a “halo” effect and lightening without inflammation was noted within several of the smaller satellite nevi, particularly on the patient’s lower extremities. The patient delivered a healthy male infant in the summer of 2004 and was not seen in the Pigmented Lesion Clinic until a year later, this time pregnant with her second child. Clinical evaluation documented decreased pigmentation of the large bathing trunk nevus as well as many of the satellite nevi. Biopsies (4-mm punch) were collected when the patient was at week 28 of gestation. These samples were collected from the patient’s right lower leg (#5 lesion in Figure B within the large garment nevus), left lateral leg (#6 lesion in Figure B), and left medial leg (#7 lesion in Figure B). Immunohistochemical staining for ERβ was performed and the intensity and percentage of the nuclear and cytoplasmic staining recorded in an identical manner to prior work by our group (7, 11). Results for all the nevus samples studied are shown in Table 1. Epidermally located nevocytes were not appreciated in these three biopsy samples; however, average ERβ nuclear staining for dermal nevocytes was 1.67 out of a total score of 5. An example of the ERβ immunohistochemistry results is shown in Figures D and E.

Table 1.

ERβ intensity by location and date

| LOCATION | STATUS | SCORE (nuclear, cytoplasmic) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| #5 in Figure B | Pregnant | 1 | 0 |

| #6 in Figure B | Pregnant | 2 | 0 |

| #7 in Figure B | Pregnant | 2 | 0 |

| #5 in Figure C | Not Pregnant | 3 | 0 |

| Not Shown | Not Pregnant | 2 | 1 |

| Not Numbered | Not Pregnant | 3 | 1 |

| #7 in Figure C | Not Pregnant | 2 | 1 |

One year following the birth of her second child, the patient presented to clinic complaining that “my moles have changed a little.” The patient was breast feeding her infant daughter at this time. Clinical exam revealed three focal areas of darkening within the patient’s large garment nevus on the right lateral thigh (#5 in Figure C), right inguinal crease (#6, not shown in Figure C), and right medial thigh (#7 in Figure C). There was also continued lightening within several satellite nevi, particularly on the lower legs. Biopsies of these three lesions were obtained along with a fourth biopsy (2 cm medial to #5 in Figure C) of a nearby stable satellite nevus for comparative purposes are shown in circles in Fig. C. None of the nevi biopsied showed cytologic atypia, whether during pregnancy or postpartum. Immunohistochemical staining for ERβ revealed increased nuclear staining when compared to the biopsies taken while pregnant, with dermal nuclear staining averaging 2.67 out of a total staining score of 5. In addition, cytoplasmic staining, which was not observed in the biopsies during pregnancy, was seen in these biopsies averaging a staining score of 0.67 out of 5 (7, 11), (Figures F and G). At recent follow up visits, while neither pregnant (20 months postpartum) nor breast feeding, the patient had continued to notice areas of darkening within her garment nevus and satellite nevi on the arms, though some of the satellite nevi on the legs remain less pigmented.

Discussion

A review of the literature yields only three case reports detailing the effects of pregnancy on congenital nevi. Two of the cases were not typical for congenital nevi. One case involved an African American patient with a congenital blue nevus which enlarged during pregnancy and was found in the postpartum period to have developed into a malignant melanoma (3). A congenital blue nevus is a rare entity, and not comparable to our case. A separate case study from Italy noted no change in a patient’s congenital garment nevus while pregnant or in the post-partum period (12), in contrast to our patient. The final case study reported the development of an agminated Spitz nevus within a congenital nevus during pregnancy (13). This nevus was also atypical for a congenital melanocytic nevus. Our fourth case has the distinct finding of clinical lightening of a giant congenital nevus and satellite nevi during two pregnancies with some re-pigmentation following parturition. This was confirmed by photographic analysis of the patient’s congenital nevi prior to, during, and following pregnancy. To our knowledge, this has not been previously reported in the literature.

Our report is also novel in that we evaluated the ERβ status within the lesions. Immunohistochemical staining for ERβ showed decreased staining in the congenital nevi during pregnancy with increased staining for ERβ following delivery, suggesting that congenital nevi may be less estrogen responsive during pregnancy. Prior work by our group found an increased expression of ERβ in benign nevi removed from pregnant women as well as atypical nevi from women regardless of pregnancy status (11). Our previously published data (11) which included the ER staining data from this patient and one other patient who was pregnant with congenital nevi showed decreased staining for ERβ in congenital nevi from pregnant women when compared to non-pregnant controls (17 pts.). Based on the small number of patients with congenital nevi in these studies, it remains unclear whether this typifies the normal effects of increased estrogen states on congenital nevi. Another limitation of this study is that biopsies were not taken from the same sites during and after pregnancy in this patient.

Along with clinical observation, the presence of estrogen receptors on melanocytes in nevi and melanoma suggests that these nevocytes are estrogen responsive (2, 7, 11). Historically, cases in the literature have reported an increase in size, thickening, or darkening of nevi during pregnancy, although recent evidence suggests that this may not be the case. We observed the unusual finding of clinical lightening along with a decreased expression of ERβ during pregnancy in a patient with a giant congenital nevus and satellite congenital nevi. This suggests that decreased expression of ERβ in congenital nevi during pregnancy may lead to decreased production of melanin. Previous studies in melanocyte cell cultures suggest that estradiol increases tyrosinase, tyrosinase-related proteins 1 and 2 (TRP-1 and TRP-2) mRNA, (14) and up-regulates expression of melanocortin 1 receptor (MC1R) mRNA (15), presumably through ERβ. Therefore, a decrease in ERβ might be expected to have the opposite effect, and could possibly decrease pigmentation through these mechanisms (even though estrogen levels would be expected to be high in pregnancy). Certainly, the apparently altered response of congenital nevi, particularly large, garment nevi, during pregnancy compared to acquired nevi bears further study. A better understanding of congenital nevi and their response to estrogen is also indicated as patients with large, garment-type nevi have an increased risk for developing melanoma, and these patients can be difficult to follow and evaluate (1, 4). We did not see any evidence of atypia in any of the congenital nevi we biopsied in this patient. This was an important observation because we previously had noted decreasing levels of ERβ with increasing depths of melanomas (7). However, in light of the lack of histologic atypia, we do not believe a similar mechanism is responsible for the decrease in ERβ seen in congenital nevi with pregnancy. While there are no conclusive data suggesting that pregnancy has a detrimental effect on the incidence or progression of melanoma, (8,9), careful attention should still be paid to the pregnant patient with pigmented lesions. Larger studies of pregnancy effects upon patients with large congenital nevi are indicated, because our review confirms very little data exist. Photographic documentation and dermoscopy may be useful in these patients for assessment and comparison purposes. Currently, the most effective method for evaluating and treating these patients remains close follow-up at regular and frequent intervals by a dermatologist trained at evaluating pigmented lesions.

Fig. 1.

Clinical Photographs: Note: Mild variation is seen in exposure secondary to different cameras used in the first photograph and the following photographs.

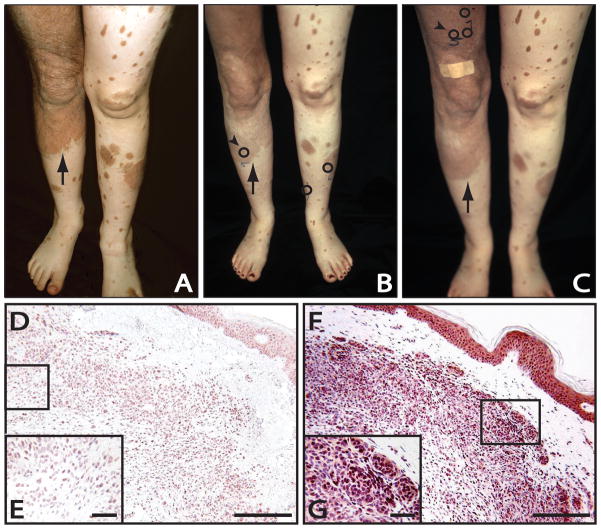

A. Photograph of the patient’s lower extremities showing both the large garment nevus on right thigh/leg (arrow) as well as smaller satellite lesions taken at age 6, years prior to pregnancy.

B. Photograph of the patient’s lower extremities, during her second pregnancy, demonstrating part of the large congenital nevus on the right thigh and leg (arrow) as well as smaller satellite nevi that had lightened during the pregnancy. Arrowhead depicts the location of the biopsy site for the immunostaining of Figures D, E. Circled areas depict the locations of all the biopsy sites taken at this time.

C. Photograph of the patient’s lower extremities, one year post-partum, demonstrating darkening and re-pigmentation of the large garment nevus on the right leg (arrow), as well as a portion of the satellite lesion on the left thigh. Arrowhead depicts the site of focal darkening within the garment nevus and the biopsy site for the immunostaining in Figures F, G. Circled areas depict the location of all biopsy sites taken at this time.

Immunohistochemistry:

D. Immunohistochemistry for ERβ of the changing large congenital nevus taken from the patient’s right lower leg while 28 weeks pregnant (arrowhead in Figure B). The patient’s congenital nevus had exhibited clinical lightening throughout the pregnancy. This representative field shows a mixture of immunopositive (red) and immunonegative (blue) nevocytes for ERβ. Scale bar = 660μ

E. Insert: Higher magnification of the same lesion showing numerous ERβ immunonegative nevocytes counterstained with hematoxylin (blue color). Scale bar = 164μ

F. Immunohistochemistry for ERB within the darkening large congenital nevus taken from the patient’s right thigh one year following parturition (refer to arrowhead in Figure C). Note intense immunoreactivity for ERβ, particularly in the more rounded, clustered nevocytes. There is also significant cytoplasmic staining. Scale bar = 660μ

G. Insert: Higher magnification with the same lesion. Virtually every nevocyte exhibits immunopositive staining for ERβ (red), with only rare exception. Scale bar = 164μ

Acknowledgments

We thank Gabriella Giro, PhD for her linguistic expertise in translating one of our reference manuscripts from Italian to English. In addition, we would like to acknowledge Ms. Nancy Cardwell and Ms. Alonda Pollins for their assistance with the immunohistochemistry and figures. Support for this project was provided by the Skin Disease Research Center (NIH 5P30 AR041943) and the Vanderbilt University School of Medicine Emphasis Program.

Abbreviations

- ERβ

estrogen receptor β

Footnotes

Author Contributions: Drs. Nading, Nanney, and Ellis had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. All authors were ]involved in data acquisition, analysis and interpretation, as well as drafting and critical revisions of this manuscript.

Financial Disclosure: Drs. Nading, Nanney, and Ellis have no relevant financial interests to report.

References

- 1.Bett BJ. Large or multiple congenital melanocytic nevi: occurrence of cutaneous melanoma in 1008 persons. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52:793–797. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2005.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ellis DL, Wheeland RG, Solomon H. Estrogen and progesterone receptors in congenital melanocytic nevi. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1985;12:235–244. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(85)80028-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hu W, Nelson JE, Mohney CA, Willen MD. Malignant melanoma arising in a pregnant African American woman with a congenital blue nevus. Dermatol Surg. 2004;30:1530–1532. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2004.30550.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Streams BN, Lio PA, Mihm MC, Sober AJ. A nonepidermal, primary malignant melanoma arising in a giant congenital melanocytic nevus 40 years after partial surgical removal. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:789–792. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2003.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Swerdlow AJ, English JS, Qiao Z. The risk of melanoma in patients with congenital nevi: a cohort study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32:595–599. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(95)90343-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhao C, Dahlman-Wright K, Gustafsson J-A. Estrogen receptor β: an overview update. Nuclear Receptor Signaling. 2008;6:1–10. doi: 10.1621/nrs.06003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schmidt AN, Nanney LB, Boyd AS, King LE, Jr, Ellis DL. Oestrogen receptor-beta expression in melanocytic lesions. Exp Dermatol. 2006;15:971–980. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0625.2006.00502.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Driscoll MS, Grant-Kels JM. Nevi and melanoma in pregnancy. Dermatol Clin. 2006;24:199–204. vi. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2006.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Driscoll MS, Grant-Kels JM. Hormones, nevi, and melanoma: an approach to the patient. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57:919–931. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2007.08.045. quiz 932–916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grin CM, Rojas AI, Grant-Kels JM. Does pregnancy alter melanocytic nevi? J Cutan Pathol. 2001;28:389–392. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0560.2001.028008389.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nading MA, Nanney LB, Boyd AS, Ellis DL. Estrogen receptor beta expression in nevi during pregnancy. Exp Dermatol. 2008;17:489–497. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0625.2007.00667.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Trompeo P, Sipione A, Ubertalli S. Congenital giant melanocytic mole and pregnancy. Report of a case and review of the literature. Minerva Ginecol. 1990;42:481–483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aloi F, Tomasini C, Pippione M. Agminated Spitz nevi occurring within a congenital speckled lentiginous nevus. Am J Dermatopathol. 1995;17:594–598. doi: 10.1097/00000372-199512000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kippenberger S, Loitsch S, Solano F, Bernd A, Kaufmann R. Quantification of tyrosinase, TRP-1, and TRP-2 transcripts in human melanocytes by reverse transcriptase-competitive multiplex PCR - regulation by steroid hormones. J Invest Dermatol. 1998;110:364–367. doi: 10.1038/jid.1998.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Scott MC, Suzuki I, Abdel-Malek ZA. Regulation of the human melanocortin 1 receptor expression in epidermal melanocytes by paracrine and endocrine factors and by ultraviolet radiation. Pigment Cell Res. 2002;15:433–439. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0749.2002.02051.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]